Jewish Wedding Rings with Miniature Architecture from Medieval Europe

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Ceremony

3. Legal Transaction

4. Stylistic Development

5. Type and Motif

6. Commemoration of the Destruction of the Temple

7. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This paper brings together the results of my research on Jewish wedding rings with miniature architecture in the Middle Ages, some of which have already been published (Stürzebecher in preparation; Stürzebecher 2020), based on the chapter on the Jewish wedding ring from the Erfurt Treasure in the author’s dissertation: (Stürzebecher 2010). I thank Andreas Lehnertz (Jerusalem) for reading drafts of the paper and his helpful comments, and Eyal Levinson (Jerusalem) and Vladislav Zeev Slepoy (Halle), who provided me additionally with help in accessing and understanding the relevant rabbinic legal opinions. |

| 2 | There were both economic, since only one celebration had to be financed, and social reasons for this: the simultaneity of erusin and nissuʾin minimized the uncertainty for the bride. (Baumgarten 2013, 216f). See also (Grossmann 2004, p. 49; De Vries 1984, 203ff., p. 223; Mehlitz 1992, pp. 154, 218; Gozani and Reiss 2001, p. 24). |

| 3 | Mishnah Qiddushin 1:1. (Krupp 2004, 2). Cf. also (Gozani and Reiss 2001, p. 21; Mehlitz 1992, p. 141, 152ff.) Mehlitz indicates here the pure symbolism of the appropriation of the bride, since only a meaningless sum of money was to be exchanged. |

| 4 | (Singer 1925), 10:428. See also (Chadour 1994, vol. 2, p. 323; Putík 1994, p. 82; Lewittes 1994, p. 71; Gozani and Reiss 2001, p. 29). In Christianity, too, initially only the handing over of a ring to the bride was customary, but since the 13th century, probably under the influence of the church, this was replaced by the exchange of rings. (Stevenson 1982, p. 53; Deneke 1991, col. 61); cf. also (Cherry 1981, p. 59). In Byzantium, two rings were already common since the 11th century, a gold one for the bride, a silver one for the groom. (Stevenson 1982, p. 100). In contrast, rings play no role during marriages in medieval Islamic society. (Rapoport 2005). |

| 5 | The handing over of the ring originally took place in the context of the engagement, therefore some authors speak of “engagement rings” for rings of the type examined here; e.g., (Abrahams 2009, p. 197; Lewittes 1994, 71ff). Since in the Middle Ages erusin and nissuʾin were celebrated in a ceremony, the term “wedding ring” seems more meaningful to me. |

| 6 | Quote according (Abrahams 2009, p. 222); Cf. (Spitzer 1989, pp. 466–67). There are no indications as to why the index finger was chosen for the ceremony. Possibly this was done in distinction to the Christian ritual: here the ring was traditionally placed on the fourth finger of the left hand, which was believed to have a vein leading directly to the heart. (Stevenson 1982, p. 53; Rapisarda 2006, 177ff). |

| 7 | David Sofer Collection London, formerly: Schocken Institute for Jewish Studies of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America Jerusalem, Ms. 24087, fol. 12v. (Gutmann 1970, p. 314, fig. 22; Metzger and Metzger 1983, p. 237, fig. 344). |

| 8 | This custom is also mentioned by Maharil: (Spitzer 1989, p. 466). The use of a wedding canopy (huppah) is only attested since the early 16th century. For the earliest extant depiction of a huppah, see (Wolfthal 2004, p. 115, fig. 61). |

| 9 | Rabbi Mordechai ben Hillel (13th cent., German lands), Comments on Qiddushin § 488. Also compare Shulḥan ʿArukh, Even ha-ʿezer 31,2 and (Abrahams 2009, 198f). |

| 10 | Since the Middle Ages, Ashkenaz has referred to Northern Europe and the German-speaking world, Sepharad to the Iberian Peninsula. |

| 11 | (Elfenbein 1943, p. 222), Responsum 198. |

| 12 | 1 Gulden = 3.5 g gold; see (Kluge 2004, 12f). |

| 13 | (Steiman 1963, p. 49). All over Ashkenazic areas in the Middle Ages the bride money was very high and was supposed to secure the wife and the whole family after the death of the husband, and also in the case of divorce.; see (Baumgarten 2018, 449f). Cf. also (Tallan 1989, p. 93; Tallan 1991, p. 66). |

| 14 | (Agus 1947, p. 308) (Even Haezer, no. 275). |

| 15 | (Agus 1947, 308f). (Even Haezer, no. 276). |

| 16 | Sheʾelot u-teshuvot […] Yistaʾel mi-Brunaʾ (Jerusalem 1987) 71, Resp. 94. |

| 17 | See note 7. |

| 18 | This is the only more accurate depiction of a Jewish wedding ring in the Middle Ages; all other illuminations have in common that the rings are always only schematically depicted as a simple hoop. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Wien, Cod. Hebr. 218. (Keil 2006, 37f.; Metzger and Metzger 1983, p. 237, fig. 342). |

| 19 | (Levinson 2022, 121f.; Baumgarten et al. 2022, pp. 19–20; Agus 1947, p. 44, 300f). (Even Haezer, no. 268). |

| 20 | Asher b. Jechiel, She’elot u-teshuvot (Jerusalem 1994) § 35, 156. |

| 21 | (Aviṭan 1991, p. 154) (No. 210). |

| 22 | On the other hand, there is no evidence to support the assertion put forward by various authors that wedding rings were owned by Jewish communities. Cf. for example on community wedding rings without indication of sources: (Kanof 1970, p. 199; Chadour 1994, vol. 2, p. 323; Wener 2005, p. 31; or Heimann-Jelinek 2006, p. 96). Joseph Gutmann even fundamentally doubted the authenticity of a number of preserved wedding rings: (Gutmann 2002). He also considers the rings from the Colmar and Weißenfels treasures to be modern works or forgeries of the 19th century. However, the context, content, and history of both treasure finds clearly speak for their authenticity, which is further confirmed by the investigation of the Erfurt treasure. For the similarities of the treasures mentioned, see (Stürzebecher 2010, 185ff). There you find also brief descriptions, find history, and further literature on Colmar (pp. 169ff.) and Weißenfels (pp. 165ff.). Modern imitation could also be ruled out in material-analytical and technological comparisons. Cf. Pasch (2010) and Mecking (2010). |

| 23 | (Buxtorf 1643; Schudt 1715, 3f.; Kirchner 1734; Bodenschatz 1748, p. 125). Schudt mentions in this context that wedding rings usually bear the inscription mazal tov. This mention was regarded as the earliest written proof, but such an inscription was already noted in the above mentioned responsum by Maharam Minz in the 15th century and the preserved rings from Colmar, Erfurt, Weißenfels, and Munich as material evidence of this custom show that this inscription was already in use in 13th/14th century. |

| 24 | See note 9. |

| 25 | (Domb 1991, vol. 1, p. 279, no.70). See also (Noy 2021, p. 89). |

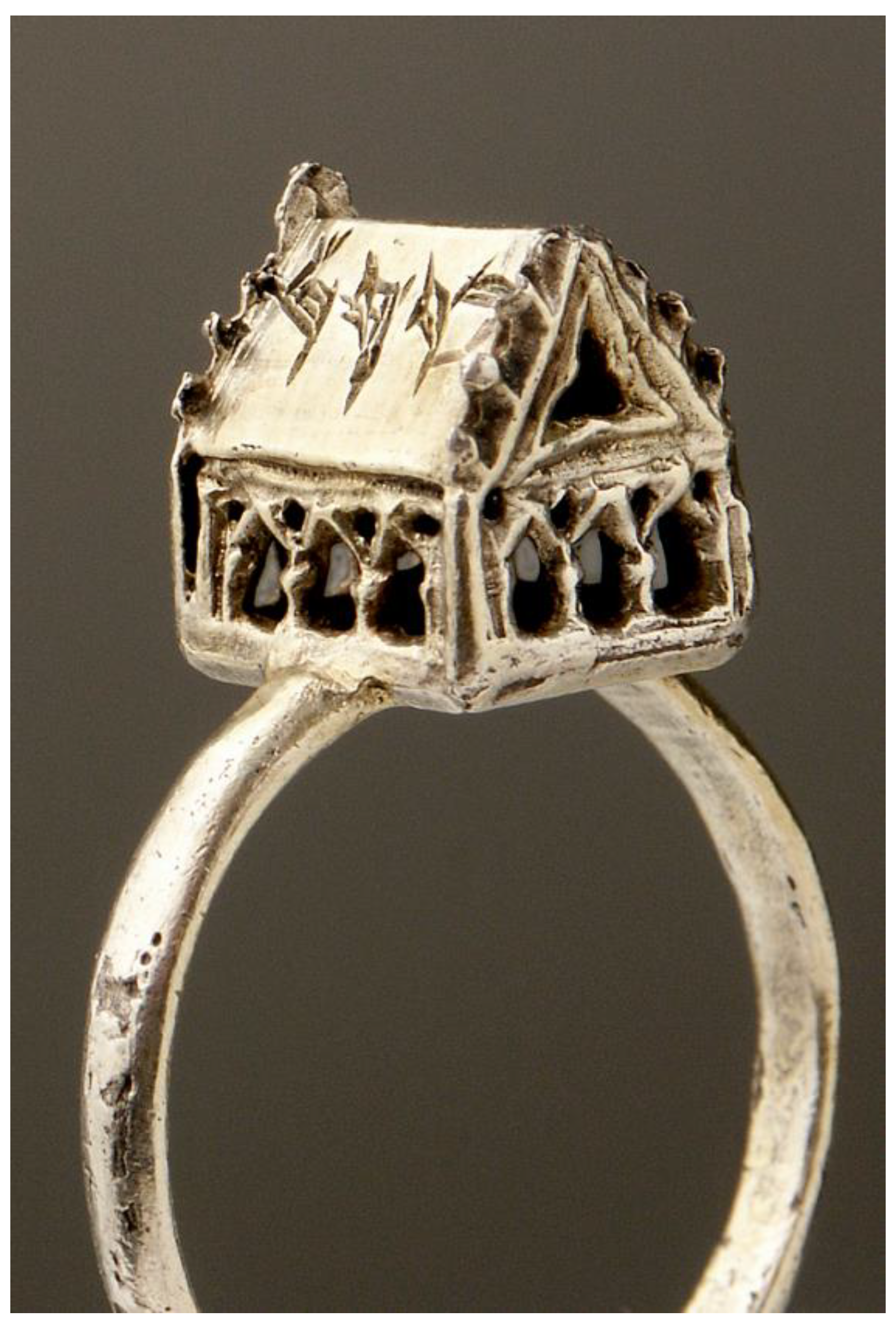

| 26 | Even though some authors deny the use of rings with miniature architecture as wedding rings. They mostly refer to the halakhic rule that undecorated rings are to be used. For example, (Sperber 2008, p. 158), writes: "Patently, these rings were not intended to effect the actual betrothal, because the halakha requires a ring without any stone, engraving, name or plating", citing Shulhan Arukh, Even ha-Ezer 31. But Even ha-Ezer 31, $2 only says: “[…] we have the custom to marry with a ring that has no stone” (Shulḥan ʿArukh, Even ha-ʿezer 31,2.) and mentions neither engraving, name or plating. Daniel Sperber even suggests that two types of rings may have played a role within the wedding ceremony: a simple, unadorned one for the actual marriage and an elaborately decorated one for the public ritual (Sperber 2008, 163ff.). But there is no indication of such a use of two types of rings in any of the known sources. |

| 27 | Cf. for example a Syrian ring of the 3rd century CE in the Kunstgewerbemuseum Cologne, which carries a temple-like, square structure with a set stone as a bezel: (Chadour and Joppien 1985, 78, no. 103). |

| 28 | Cf. to this, inter alia, (Ward 1981, 49f., no. 104; Seidmann 1984, p. 41; and Chadour 1994, vol.1, p. 147, nos. 495f). |

| 29 | Both rings (Inv.-Nr. 863-1871 and 864-1871) are mentioned by (Keen 1991), 80, as Jewish wedding rings. The dating to the 16th or 18th century proposed there seems to be arbitrary. An investigation by Marian Campbell, formerly Victoria and Albert Museum, and John Cherry, formerly British Museum, together with the author on 20 February 2009, resulted in a classification in the 6th–8th century. |

| 30 | According to the author, a golden ring from a private collection dated by Vivian Mann before 1348 is not medieval. Cf. (Mann 2016, pp. 144–46, no. 62a; Mann 2018, p. 182; Mann 2020, p. 88, fig. 36). |

| 31 | With the exception of the ring from the Wittelsbach treasury, all the wedding rings discussed come from treasure finds that were hidden during the wave of pogroms in the mid-14th century. See in detail (Stürzebecher 2010, especially p. 156f., pp. 165–71). |

| 32 | |

| 33 | This inscription can be found on the majority of Jewish wedding rings, both from the Middle Ages and subsequent centuries. Cf. to this, inter alia, (Seidmann 1984, p. 41). |

| 34 | For the rings from the treasures of Colmar, Weißenfels, and the treasure chamber of the Wittelsbacher in Munich, see (Stürzebecher 2010, 95f. and 278) (Verg. Kat. Nr. 36, 37, and 38) with detailed literature. |

| 35 | On the excavation in the Michaelisstraße in Erfurt, see (Sczech 2010). |

| 36 | The artistic reference to contemporary architecture is typical for a large complex of Gothic goldsmiths’ art. Pointed arches and tracery structure rings and belt fittings, monstrances, reliquaries, or ciboria. The individual elements were serially formed into patrices and soldered together. This working method was common in the 14th century and made it possible to produce various objects from a repertoire of individual parts. The Erfurt wedding ring also consists of 20 soldered individual parts. (Pasch 2010, p. 273). |

| 37 | The letters do not correspond to the actual form of proper Hebrew letters. This could indicate the execution by Christian goldsmiths, who seem to have engraved the inscription according to a pattern and unaware of Hebrew letters. The same is true for the inscription on the roof of the wedding ring from Weißenfels which is amateurishly executed. However, in medieval Europe there is also evidence of Jews practicing the goldsmith’s craft and certainly making wedding rings. Cf. (Lehnertz and Stürzebecher in preparation). |

| 38 | Already since late Roman times, engagement and wedding rings often bear the motif of clasped hands (dextrarum iunctio) (cf. e.g., (Bassermann-Jordan 1909, 37, fig. 43; Johns 1996, 63, fig. 3.24, 25; Scarisbrick 2021, p. 16), which was very popular in Central Europe for a long time. For example, a 12th century ring from the Lark Hill find in the British Museum (Cherry 1981, 59f., no. 114; Zarnecki 1984, p. 293, no. 320 f. with fig.) shows the plastically executed clasped hands, as does a whole series of simple 13th century rings from the Fuchsenhof treasure find. The motif here is partly worked plastically, partly only engraved (Krabath and Bühler 2004, 276 ff., 562 ff., 588 f., no. 249–262, 272). Other examples include a 13th/14th century German love ring in the Bavarian National Museum in Munich (Steingräber 1956, p. 47, fig. 63; Haimerl 1999, p. 109 with fig.), two rings from excavations in Amsterdam, pewter and copper, 16th century (Baart 1977, 213 f., no. 390 f.), a 16th century gold finger ring from Italy (Chadour and Joppien 1985, p. 155, no. 242), or two German silver rings from the second half of the 19th century (Chadour and Joppien 1985, 194f., no. 305, 306). The 14th century Jewish wedding ring from the Erfurt treasure also uses the motif of the dextrarum iunctio on its ring band and combines it with the motif of the miniature building. Unlike in Central and Western Europe, where this motif is limited to the depiction of clasped hands, Byzantine rings of the 5th to 8th centuries show figural depictions of the dextrarum iunctio with the bride and groom and Christ in the role of Concordia on their ring plate, such as an early 8th century wedding ring from Abuqir Bay, Egypt (Petrina 2012). Other Byzantine wedding rings show only the portrait of the bride and groom (see Ward 1981, p. 47, no. 100; Walker 2002; Hindman 2015, pp. 132, 209, 217, no. 32, 48). However, as in Judaism (see above), simple, unadorned rings were certainly used as wedding rings too. For example, an illustration of the life of St. Alexius in the St Albans Psalter of Christina of Markyate, 12th century, on p. 57 shows the saint presenting giving his wife “a plain golden ring with a single dark stone” (van Houts 2019, p. 80). |

| 39 | See, among others, (Dräger 2001) or (Stürzebecher 2010, pp. 165–68). |

| 40 | Cf. for a detailed discussion of this type and other forms of Jewish wedding rings: (Stürzebecher 2010, 96f). It is striking that some of the wedding rings of the 19th century are strongly reminiscent of medieval rings, which suggests that in the 19th century medieval rings of this type may still have been available as originals. Wedding rings of the preceding centuries, on the other hand, do not show any medieval forms, but were designed according to the style of the time (see above), so there was neither continuity nor conservatism in the manufacturing method. A particularly conspicuous example is a golden Jewish wedding ring from the Cologne City Museum, which seems to copy the Erfurt wedding ring in its execution, but which, according to material analysis, was not made until after 1820: (Mecking et al. 2018). |

| 41 | Among others, from the British jewellery designer Chloe Lee Carson, who reports in her blog on how she developed new interpretations of this ring type for her own wedding, based on historical ring forms, and now also sells them: http://www.chloeleecarson.co.uk/blog/2014/10/23/my-engagement-ring-story-reviving-the-jewish-house-ring (accessed on 08 August 2022). |

| 42 | In Christianity, too, initially only the handing over of a ring to the bride was common, it was replaced by the exchange of rings since the 13th century. See note 4. Since late Roman times, engagement and wedding rings often carry the motif of clasped hands (dextrarum iunctio). See note 38. |

| 43 | cf. note 38. |

| 44 | It is possible that the Colmar Ring originally had a similar device. Analyses show that the roof was glued on secondarily after it was found, probably as early as the 19th century (Pasch 2010, p. 277). Perhaps a responsum by Meir of Rothenburg already refers to such a ring in the 13th century. It deals with the question of whether it is permissible to wear a ring on Shabbat that encloses a loose stone or piece of sheet metal in a hollow space so that it emits a ringing sound when moved. Rabbi Meir says that a person is not permitted to make musical sounds on Shabbat, especially if they serve a specific purpose. However, since the ring does not make a musical sound or serve a useful purpose, it is permitted to wear it on Shabbat. (Agus 1947), 182 (Orah Hayim no. 40). |

| 45 | For example, in Cologne (Potthoff and Wiehen 2019, fig. on title; Grellert and Ristow 2021) or Erfurt (Altwasser 2009, 58 ff., with further examples for comparison). |

| 46 | (Keil 2004, p. 326; Feuchtwanger-Sarig 2022, p. 290); See also (Hollender 2013, p. 58). Usually weddings took place in the synagogue courtyard. (Lehnertz 2020, p. 39; Cohen and Horowitz 1990, 229ff). |

| 47 | For example, (Abrahams 2009, p. 198). For a detailed discussion of the motif, see (Stürzebecher 2010, p. 96). |

| 48 | The tradition of breaking a glass in the course of the wedding ceremony has also been a reminder of the destruction of the temple since the end of the 13th century at the latest. (Feuchtwanger 1985, p. 35; Goldberg 2003, p. 149). Jacob Z. Lauterbach, however, suspects an older origin of this ceremony in the protection against demons during marriage, which was only later reinterpreted as a commemoration of the destruction of Jerusalem. (Lauterbach 1970, pp. 340–69). (Goldberg 2003, 150ff.), also discusses other possible interpretations of the ritual. |

References

- Abrahams, Israel. 2009. Jewish Life in the Middle Ages. London and New York: Israel Abrahams. [Google Scholar]

- Agus, Irving A. 1947. Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg. His Life and his Work as Sources for the religious, legal, and social History of the Jews of Germany in the thirteenth Century. Philadelphia: The Dropsie College, Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Altwasser, Elmar. 2009. Die Baugeschichte der Alten Synagoge Erfurt vom 11–20. Jahrhundert. In Die mittelalterliche jüdische Kultur in Erfurt. Vol. 4, Die Alte Synagoge. Edited by Sven Ostritz. Langenweißbach: Beier & Beran, pp. 8–193. [Google Scholar]

- Aviṭan, Shmuʾel. 1991. Sefer Terumat ha-Deshen, Jerusalem.

- Baart, Jan. 1977. Opgravingen in Amsterdam. 20 Jaar Stadskernonderzoek. Amsterdam: Fibula-van Dishoeck. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten, Elisheva. 2013. Gender and daily Life in Jewish Communities. In The Oxford Handbook of Women and Gender in Medieval Europe. Edited by Judith M. Bennet and Ruth Mazo Karras. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, pp. 213–28. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten, Elisheva. 2018. The Family. In The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 6: The Middle Ages: The Christian World. Edited by Robert Chazan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 440–62. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten, Elisheva, Tzafrir Barzilay, and Eyal Levinson. 2022. Jewish Life in Medieval Northern Europe, 1080–1350: A Sourcebook. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Bassermann-Jordan, Ernst. 1909. Der Schmuck. Leipzig: Klinkhardt & Biermann. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenschatz, Johann Christoph. 1748. Kirchliche Verfassung der heutigen Juden sonderlich derer in Deutschland, T. 3–4: Von den Lehrsätzen und der übrigen Lebensart der heutigen sonderlich Deutschen Juden, Erlangen.

- Buxtorf, Iohann. 1643. Synagoga Judaica: Das ist [der] Juden-schul. […]. Basel: König. [Google Scholar]

- Chadour, Anna Beatriz. 1994. Ringe. Die Alice und Louis Koch Sammlung. Vierzig Jahrhunderte durch vier Generationen gesehen, 2 vol. Leeds: Maney. [Google Scholar]

- Chadour, Anna Beatriz, and Rüdiger Joppien. 1985. Schmuck. In Bd. 2: Fingerringe (Kataloge des Kunstgewerbemuseums Köln 10). Köln: Kunstgewerbemuseum. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, John. 1981. Medieval Rings. In The Ring. From Antiquity to the Twentieth Century. Edited by Anne Ward, John Cherry, Charlotte Gere and Barbara Cartlidge. London: Thames and Hudson, pp. 51–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Esther, and Elliot Horowitz. 1990. In Search of the Sacred: Jews, Christians and Rituals of Marriage in the Later Middle Ages. Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies 20: 225–50. [Google Scholar]

- Deneke, Bernward. 1991. Art. Hochzeit, Lexikon des Mittelalters, Bd. V. München and Zürich: Artemis, Kol. 61. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, Simon Ph. 1984. Jüdische Riten und Symbole. Wiesbaden: Fourier. [Google Scholar]

- Domb, Jonathan Shraga. 1991. Moses son of Isaac haLevi Mintz, She’elot uTeshuvot Rabbenu Moshe Mintz (Maharam Mintz). Jerusalem: Machon Yerushalayim. [Google Scholar]

- Dräger, Ulf. 2001. Zeugnisse der Liebe aus dem frühen 14. Jahrhundert. In Schönheit, Macht und Tod. 120 Funde aus 120 Jahren. Edited by Harald Meller. Halle: Landesamt für Archäologie, Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte, pp. 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Drake Boehm, Barbara. 2020. The Colmar Treasure: A Medieval Jewish Legacy. New York: Scala Arts Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Elfenbein, Israel. 1943. Teshuvot Rashi, New York.

- Feuchtwanger, Naomi. 1985. Interrelations between the Jewish and Christian Wedding in medieval Ashkenaz. Paper presented at the ninth World Congress of Jewish Studies, Jerusalem, Israel, August 4–12; pp. 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Feuchtwanger-Sarig, Naomi. 2022. Thy Father’s Instruction. Reading the Nuremberg Miscellany as Jewish Cultural History (Studia Judaica. Forschungen zur Wissenschaft des Judentums Bd. 79 Rethinking Diaspora vol. 2). Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Hubert. 1980. Quellen und Studien zur Kunstpolitik der Wittelsbacher vom 16. bis zum 18. Jahrhundert. München: Hirmer. [Google Scholar]

- Goitein, Shlomo D. 1978. A Mediterranean Society. The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza. Bd. 3: The Family. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: Univ. of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Harvey E. 2003. Jewish Passages. Cycles of Jewish Life. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gozani, T., and D. Y. Reiss. 2001. Law or Custom? The historical evolution of jewish wedding ceremonies. In Romance & Ritual. Celebrating the Jewish Wedding. Edited by Grace Cohen Grossman. Los Angeles: Skirball Cultural Center, pp. 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Grellert, Marc, and Sebastian Ristow. 2021. Rekonstruktion einer Bima aus dem Mittelalter. In Jüdische Geschichte und Gegenwart in Deutschland. Aktuelle Fragen und Positionen. Edited by Laura Cohen, Thomas Otten and Christiane Twiehaus. Oppenheim: Nünnerich-Asmus Verlag, pp. 118–19. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann, Avraham. 2004. Pious and Rebellious. Jewish Women in Medieval Europe. London: University Press of New England. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann, Joseph. 1970. Wedding customs and ceremonies in art. In Beauty in holiness; studies in Jewish customs and ceremonial art. Edited by Joseph Gutmann. New York: Ktav Pub. House, pp. 313–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann, Joseph. 1987. The Jewish Life Cycle. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann, Joseph. 2002. With This Ring I Thee Wed: Unusual Wedding Rings. In For Every Thing There Is a Season. Proceedings of the Symposium on Jewish Ritual Art. Edited by Joseph Gutmann. Cleveland: Cleveland State University, pp. 133–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hackenbroch, Yvonne. 1979. Renaissance Jewellery. München: Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Haimerl, Barbara. 1999. Schmuck und Gerät in der Spätgotik. In Zwischen Himmel und Hölle. Vom Leben bis zum Sterben in einer spätmittelalterlichen Stadt in Niederbayern. Katalog. Landau: Eichendorf, pp. 102–11. [Google Scholar]

- Heimann-Jelinek, Felicitas. 2006. Glaubensfragen. Chatrooms auf dem Weg in die Neuzeit. Ausstellungskatalog des Ulmer Museums und des Museums of the Bible. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Hindman, Sandra. 2015. Take this Ring. Medieval and Renaissance Rings from the Griffin Collection. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Hollender, Elisabeth. 2013. Hochzeitspiyyutim und ashkenazische Dichtkunst. Frankfurter Judaistische Beiträge 38: 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- van Houts, Elisabeth. 2019. Married life in the Middle Ages, 900-1300. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, Catherine. 1996. The Jewellery of Roman Britain. Celtic and Classical Traditions. London: UCL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kanof, Abram. 1970. Jewish Ceremonial Art and Religious Observance. New York: Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Keen, Michael E. 1991. Jewish Ritual Art in the Victoria & Albert Museum. London: The Stationery Office/Tso. [Google Scholar]

- Keil, Martha. 2004. Public Roles of Jewish Women in 14th and 15th-Century. Ashkenaz: Business, Community and Ritual. In The Jews of Europe in the Middle Ages (Tenth to Fifteenth Centuries): Proceedings of the International Symposium held at Speyer, 20–25 October 2002 (Cultural Encounters in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages 4). Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 317–30. [Google Scholar]

- Keil, Martha. 2006. Hebräische Urkunden und jiddische Texte. In Geschichte der Juden in Österreich. Edited by Wolfgang Herwig. (Österreichische Geschichte Erg.-Bd., 4). Wien: Ueberreuter, pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner, Paul Ch. 1734. Jüdisches Ceremoniell. Beschreibung jüdischer Feste und Gebräuche. Nürnberg: Reprint-Verlag-Leipzig. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum, Engelbert, and Günter Bandmann. 1994. Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie. Rom, Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Kluge, Bernd. 2004. Münze und Geld im Mittelalter. Eine numismatische Skizze. Frankfurt am Main: Busso Peus Nachf. [Google Scholar]

- Krabath, Stefan, and Birgit Bühler. 2004. Katalog der nichtmonetären Objekte. In Der Schatzfund von Fuchsenhof. (Studien zur Kulturgeschichte von Oberösterreich 15). Edited by Bernhard Prokisch and Thomas Kühtreiber. Linz: Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum Linz, pp. 425–733. [Google Scholar]

- Krupp, Michael. 2004. Die Mischna: Textkritische Ausgabe mit deutscher Übersetzung und Kommentar. Teil 3,7: Kidduschin: Antrauung. Jerusalem: Lee Achim Sefarim. [Google Scholar]

- Lauterbach, Jacob Z. 1970. The Ceremony of Breaking a Glass at Weddings. In Beauty in Holiness. Studies in Jewish Customs and Ceremonial Art. Edited by Joseph Gutmann. New York: Ktav Pub. House, pp. 340–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lehnertz, Andreas. 2020. Christen im öffentlichen und privaten Raum der mittelalterlichen Judenviertel. In Tür an Tür im Mittelalter. Jüdisch-Christliche Nachbarschaft vor dem Ghetto. (Münchner Beiträge zur Jüdischen Geschichte und Kultur, Jg. 14/Heft 1 2020). Edited by Rachel Furst and Sophia Schmitt. München: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lehnertz, Andreas, and Maria Stürzebecher. in preparation. Tracing Jewish Goldsmiths in Medieval Ashkenaz. In Jewish Craftspeople in the Middle Ages–Objects, Sources and Materials. working title. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Leroy, Catherine. 1999. Trésor de Colmar. Exposition Musée d’Unterlinden. Colma: Musée dỦnterlinden r. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, Eyal. 2022. Gender and Sexuality in Ashkenaz in the Middle Ages. Jerusalem: Leo Baeck Institute. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Lewittes, Mendell. 1994. Jewish Marriage. Rabbinic Law, Legend, and Custom. Northvale and London: Jason Aronson, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, Laura S. 2014. The Piyyutim le-Hatan of Qallir and Amittai: Jewish Marriage Customs in Early Byzantium. In Talmuda de-Eretz Israel: Archaeology and the Rabbis in Late Antique Palestine. Edited by Steven Fine and Aaron Koller. Boston and Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 275–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Vivian B. 2016. Medieval Jewish Wedding Rings. In Jerusalem 1000–1400. Every People Under Heaven. Edited by Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 144–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Vivian B. 2018. The first English Collector of Jewish Wedding Rings and their Dealers. Images: A Journal of Jewish Art and Visual Culture 11: 177–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, Vivian B. 2020. Jewish Ceremonial Wedding Ring. In The Colmar Treasure: A Medieval Jewish Legacy. Edited by Barbara Drake Boehm. New York: Scala Arts Publishers, p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Mecking, Oliver. 2010. Die Rekonstruktion der Goldschmiedetechniken aufgrund der chemischen Analytik. In Die mittelalterliche jüdische Kultur in Erfurt. Vol. 2: Der Schatzfund. Analysen–Herstellungstechniken–Rekonstruktionen. Edited by Sven Ostritz. Langenweißbach: Beier & Beran, pp. 10–225. [Google Scholar]

- Mecking, Oliver, Astrid Pasch, and Maria Stürzebecher. 2018. Wenn Schmuck Geschichte erzählt. Kunsthistorische, technologische und materialtechnische Analyseergebnisse zu einem jüdischen Hochzeitsring aus Köln. Restauro. Zeitschrift für Konservierung und Restaurierung 2: 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mehlitz, Walter. 1992. Der jüdische Ritus in Brautstand und Ehe (Europäische Hochschulschriften, Reihe 19, Abt. A, 39), Frankfurt a. Frankfurt am Main and Berlin: Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, Thérèse, and Mendel Metzger. 1983. Jüdisches Leben im Mittelalter. Nach illuminierten hebräischen Handschriften vom 13. bis 16. Jahrhundert. Würzburg: Edition Popp. [Google Scholar]

- von Mutius, Hans-Georg. 1991. Rechtsentscheide Mordechai Kimchis aus Südfrankreich (13./14. Jahrhundert). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, Ido. 2021. The Mazal Tov Ring and the Ketubbah. In In and Out, Between and Beyond. Jewish Daily Life in Medieval Europe. Edited by Elisheva Baumgarten and Ido Noy. Jerusalem: Hebrew University, pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Pasch, Astrid. 2010. Zur Herstellungstechnik der Schatzfundobjekte. In Die mittelalterliche jüdische Kultur in Erfurt. Vol. 2: Der Schatzfund. Analysen–Herstellungstechniken–Rekonstruktionen. Edited by Sven Ostritz. Langenweißbach: Beier & Beran, pp. 226–437. [Google Scholar]

- Petrina, Yvonne. 2012. Ein Hochzeitsring aus der Bucht von Abuqir (Ägypten). In Byzantine Small Finds in Archaeological Contexts (Veröffentlichungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts Istanbul, ByzaS 15). Edited by Beate Böhlendorf-Arslan and Alessandra Ricci. Istanbul: Ege Yayınları, pp. 463–475. [Google Scholar]

- Potthoff, Tanja, and Michael Wiehen. 2019. da man die Juden zu Colne sluch Das Kölner Pogrom von 1349. In Beiträge zur rheinisch-jüdischen Geschichte, Heft 9, ed. MiQua-Freunde e.V. und MiQua. LVR-Jüdisches Museum im Archäologischen Quartier Köln. Köln: LVR-Jüdisches Museum im Archäologischen Quartier Köln, pp. 39–75. [Google Scholar]

- Putík, Alexandr. 1994. Jüdische Traditionen und Gebräuche. Prag: Das Jüdische Museum Prag. [Google Scholar]

- Rapisarda, Stefano. 2006. A Ring on the little Finger: Andreas Capellanus medieval Chiromancy. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 69: 175–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, Yossef. 2005. Marriage, money and divorce in Medieval Islamic Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sabar, Shalom. 2000. Masel Tow. Illuminierte jüdische Eheverträge aus der Sammlung des Israel Museum. Berlin and München: JVB. [Google Scholar]

- Satz, Yitzchik, ed. 1979. Responsa of Rabbi Yaacov Molin-Maharil. Jerusalem: Makhon Yerushalaim. [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick, Diana. 2021. I like my choyse. Posy Rings from the Griffin Collection. London: Ad Ilissvm. [Google Scholar]

- Schudt, Johann Jacob. 1715. Jüdische Merckwürdigkeiten: Vorstellende Was sich Curieuses und denckwürdiges in den neuern Zeiten bey einigen Jahr-hunderten mit denen in alle IV. Theile der Welt […]. Frankfurt am Main, Leipzig.

- Sczech, Karin. 2010. Zum archäologischen Umfeld des Schatzfundes Michaelisstraße 43 und 44. In Die mittelalterliche jüdische Kultur in Erfurt. Vol. 1: Der Schatzfund. Archäologie–Kunstgeschichte–Siedlungsgeschichte. Edited by Sven Ostritz. Langenweißbach: Beier & Beran, pp. 16–59. [Google Scholar]

- Seidmann, Gertrud. 1984. Jewish Marriage Rings. Jewellery Studies 1: 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Isidor, ed. 1925. The Jewish Encyclopedia, Bd. 10. New York: Funk and Wagnalis. [Google Scholar]

- Sperber, Daniel. 2008. The Jewish Life Cycle: Custom, Lore and Iconography. Jewish Customs from the Cradle to the Grave. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, Shlomo, ed. 1989. Sefer Maharil, Minhagim schel Rabenu Jakob Molin. Jerusalem: Makhon Yerushalaim. [Google Scholar]

- Steiman, Sidney. 1963. Custom and Survival. A Study of the Life and Work of Rabbi Jacob Molin (Moelln) Known as the Maharil (c. 1360–1427) and His Influence in Establishing the Ashkenazic Minhag (Customs of German Jewry). New York: Bloch. [Google Scholar]

- Steingräber, Erich. 1956. Alter Schmuck. München: Callwey. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, Kenneth. 1982. Nuptial Blessing. A Study of Christian Marriage Rites. London: Alcuin Club. [Google Scholar]

- Stürzebecher, Maria. 2010. Der Schatzfund aus der Michaelisstraße in Erfurt. In Die mittelalterliche jüdische Kultur in Erfurt. Vol. 1. Der Schatzfund. Archäologie–Kunstgeschichte–Siedlungsgeschichte. Edited by Sven Ostrit. Langenweißbach: Beier & Beran, pp. 60–323. [Google Scholar]

- Stürzebecher, Maria. 2020. The Medieval Jewish Wedding Ring from the Erfurt Treasure: Ceremonial Object or Bride Price? In Ritual Objects in Ritual Contexts. Erfurter Schriften zur jüdischen Geschichte Band 6. Edited by Claudia Bergmann and Maria Stürzebecher. Jena–Quedlinburg: Bussert & Stadeler, pp. 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Stürzebecher, Maria. in preparation. Mazal Tov–Zur Symbolik jüdischer Hochzeitsringe mit Miniaturarchitektur im Mittelalter. In Gedenkkolloquium für Silke Tammen (1964–2018) (working title). Edited by Antje Bosselmann-Ruickbie and Markus Späth. Berlin: Reimer.

- Taburet-Delahaye, Élisabeth. 1999. Les bijoux du trésor de Comar. In Trésor de Colmar. Exposition Musée d’Unterlinden. Edited by Catherine Leroy. Colmar: Musée d’Unterlinden, pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tallan, Cheryl. 1989. The Position of the Medieval Jewish Widow as a Function of Family Structure. Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies II.B: 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tallan, Cheryl. 1991. Medieval Jewish Widows: Their Control of Resources. Jewish History 5: 3–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammen, Silke. 2015. Bild und Heil am Körper: Reliquiaranhänger. In Kanon Kunstgeschichte. Einführung in Werke, Methoden und Epochen. Mittelalter I. Edited by Kristin Marek and Martin Schulz. München: Wilhelm Fink, pp. 299–324. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann, Achim. Forthcoming. Microarchitecture in the Medieval West, 800–1550. In The Cambridge History of Religious Architecture of the World. Edited by Richard Etlin. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Walker, Alicia. 2002. Myth and Magic in Early Byzantine Marriage Jewelry: The Persistence of Pre-Christian Traditions. In The Material Culture of Sex, Procreation, and Marriage in Premodern Europe. Edited by Anne L. McClanan and Karen Rosoff Encarnación. New York: Palgrave, pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Anne. 1981. The Rings of Antiquity. In The Ring. From Antiquity to the Twentieth Century. Edited by Anne Ward, John Cherry, Charlotte Gere and Barbara Cartlidge. London: Thames and Hudso, pp. 51–86. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Daniel H. 1998. Hec est domus domini firmiter edificata: The image of the temple in crusader art. In The Real and Ideal Jerusalem in Jewish, Christian and Islamic Art. Studies in Honor of Bezalel Narkiss on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday. Edited by Bianca Kühnel. Jerusalem: Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, pp. 210–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wener, Markus. 2005. Was vom Mittelalter übrig blieb. Fragen zur Rezeption jüdischen Kunsthandwerks im Mittelalter. In Nicht in einem Bett. Juden und Christen in Mittelalter und Frühneuzeit. Edited by Sabine Hall. St. Pölten: Institut für Geschichte der Juden in Österreich, pp. 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfthal, Diane. 2004. Picturing Yiddish: Gender, Identity, and Memory in the Illustrated Yiddish Books of Renaissance Italy (Brill’s Series in Jewish Studies 36). Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Zarnecki, George, ed. 1984. English Romanesque Art: 1066–1200. Catalogue Hayward Gallery. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stürzebecher, M. Jewish Wedding Rings with Miniature Architecture from Medieval Europe. Arts 2022, 11, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11060131

Stürzebecher M. Jewish Wedding Rings with Miniature Architecture from Medieval Europe. Arts. 2022; 11(6):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11060131

Chicago/Turabian StyleStürzebecher, Maria. 2022. "Jewish Wedding Rings with Miniature Architecture from Medieval Europe" Arts 11, no. 6: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11060131