2. The Palace of al-Mu’tamid in Seville in the Arabic Documentation

Before focusing on the main corpus of this section, we would like to highlight how, over the years, the different authors who have referred to this palace in their works have done so using different expressions. This is an aspect that should not be overlooked, in spite of the literary connotations that characterize the Arabic written documentation and context in which the texts were conceived (

Martos Quesada 2022), since it will allow us to take a step further in our knowledge, and it is also fundamental to consider the context in which it is framed. Hence, we take this reality as a starting point, following the chronology of the different historical and political periods that followed one another in al-Andalus for a better understanding of this whole scenario.

In this sense, it is precisely in the genre of 11th century poetry that we find the first documentary reference to the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak. The Cordovan poet Abū-l-Walīd b. Zaydūn (1003–1071), secretary and vizier of the ‘Abbādī court between the years 1049/1050 and 1069/1070, is noted for his poetic production (

Dīwān), collected by later authors such as Ibn Jāqān (d. 1134) and Ibn Bassām (d. 1147)

5. Among his literary compositions he extols the “palace of al-Mubārak” and highlights one of its sumptuous formal halls, known by the name of

al-Ṯurayya (The Pleiades), implying in his verses the close relationship between the latter and al-Mu’tamid of Seville (1069–1091):

- “As for the Ṯurayya, it resembles the Pleiades

- for its high position, its usefulness and beauty.

- If he does not receive your visit, al-Mu’tamid, desires it so much,

- that he will be at your side through imagination.

- He will drink at your side every day to enjoy a quiet joy:

- Extend your visit so that he may be happy.

- It would seem to thee that the palace of al-Mubārak is like the

- cheek of a girl in the center of which al-Ṯurayya is

- like a mole.

- Go around with a wine glass of the most perfect perfume

- and of the color of pure gold.

- It is a palace that rejoices the eyes with a construction of spacious rooms

- and if it could, it would be proud of its beauty”6.

- [Original translation into Spanish:

- En cuanto a la Ṯurayya se asemeja a las Pléyades

- por su alta posición, su utilidad y belleza.

- Si no recibe tu visita, al-Mu’tamid, lo desea tanto

- que iría a tu lado con la imaginación.

- Va a beber a tu lado todos los días para gozar de una

- alegría tranquila: Prolonga tu visita para que sea feliz.

- Te parecería que el palacio de al-Mubārak es como la

- mejilla de una muchacha en cuyo centro al-Ṯurayya es

- como un lunar.

- Haz circular allí una copa de vino del perfume más

- perfecto y del color del oro puro.

- Es un palacio que regocija a los ojos con una construcción

- de amplias dependencias y si ella pudiese, se enorgullecería

- por su belleza].

Even King ‘Abbādī himself remembered this palace, among others, during the years of his exile in Agmāt (1091–1095) by the Almoravids, as he left on record in the following verses, and which Ibn Jāqān collects in his

Qalāid al-’iqyān (Golden Necklaces):

- “Cry al-Mubārak for the memory of Ibn ‘Abbād,

-

cries for the memory of lions and gazelles.

-

He cries for his Ṯurayya because he is no longer covered by its stars

-

which resemble the sunset of the Pleiades when it rains […]”7.

-

[Original translation into Spanish:

- Llora al-Mubārak por el recuerdo de Ibn ‘Abbād,

- llora por el recuerdo de los leones y las gacelas.

- Llora su Ṯurayya porque ya no le cubren sus estrellas

- que se parecen al ocaso de las Pléyades cuando llueve […]].

Moreover, and although his name is not mentioned as in the previous poems, some scholars suggest that the palace referred to by the Sicilian poet Ibn Ḥamdīs (d. 1133) in one of his poetic compositions is none other than the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak (

Rubiera [1981] 1988, pp. 136–37;

Pérès 1983, p. 144;

Gómez García 2004, p. 269). Thus, we can corroborate it when he compares said construction with the

Iwān of Cosroes, basing this statement on the link established between the two—on this occasion, explicitly—by the poet Abū Ŷa’far b. Aḥmad (11th–12th centuries) in his

Risāla (

Epistle), collected by

Ibn Bassām (

1979, pp. 759–66). In that composition, the author personifies two great palaces of Seville—the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak and the

Qaṣr al-Mukarram—establishing a dialogue between them in which the former says “If the Iwān of Cosroes were my contemporary, I would still have, despite its existence, power and fame” (

Lledó Carrascosa 1986, p. 197).

Returning once again to Ibn Ḥamdīs’s poem, his verses equate the characteristics of its construction with the qualities of the prince by pointing out how “[…] from his chest [the builders] have taken their breadth, from his light the brightness; from his fame, the wide distribution and from his wisdom, the foundations” (

Rubiera [1981] 1988, p. 136;

Pérès 1983, p. 144). As we can see, he does not specify at any time to whom he is referring when mentioning the “prince”. In our opinion, it could be al-Mu’tamid himself since, prior to the year 1078, Ibn Ḥamdīs was in Sicily, and it would not be precisely until then when he appeared in the environment of the poetic court of al-Mu’tamid.

Therefore, at this time, he could have written this poem in praise for the current monarch and with the aim of becoming part of his cultural circle (

González Cavero 2013, II. 58–59). Even the Moroccan compiler ‘Abd al-Wāḥid al-Marrākušī (1185-m. after 1224) extols the virtues of the latter

8, providing support for our proposal. In view of this, and if it is really the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak, we can deduce through all of the above not only the importance that this palace attained in the 11th century as the nerve center of power and of the Taifa of Seville, but also the existence of an ex novo construction—albeit with certain nuances, as explained below.

That relevance of which we speak is evidenced in the

Risāla (

Epistle) of Abū Ŷa’far b. Aḥmad (

Lledó Carrascosa 1986, pp. 191–200), to which we alluded earlier. In it, the denier author—exiled from the court of al-Mu’tamid in the year 1076—clearly distinguishes between two palaces: the

Qaṣr al-Mukarram (Worshiped Palace) and the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak (Blessed Palace), going so far as to compare the latter to the Ka’ba after having become “the goal of travelers, the center of pilgrims” (ibid., p. 197). Such an expression should not be strange to us, since we know that Seville had by then become the intellectual center of greatest importance in the entire peninsula, to which a multitude of literates and sages flocked to form part of the ‘Abbādī cultural environment (

Lirola Delgado 2013, pp. 107–10).

Sharing the opinion of Lledó Carrascosa, everything seems to indicate that the

Qaṣr al-Mukarram was the older of the two, with al-Mu’tamid himself being in charge of renovating it and, at the same time, reviving the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak, thereby giving the latter the prominence that it deserved. Does this mean that said palace may have existed prior to the reign of the last sovereign of the Sevillian Taifa

9? Apart from the latter, this relationship between this palatine construction and the aforementioned monarch is something that is constant in the texts, and it is also mentioned in the documentary sources as “al-Mu’tamid’s palace” or “Ibn ‘Abbād’s palace”. Thus, we can verify it on the occasion of the assassination of al-Mu’tamid’s friend, poet, and prime minister Ibn ‘Ammār (d. 1086) at the hands of the Sevillian king himself—an event recorded by ‘Abd al-Wāḥid al-Marrākušī in his work. Despite the later date of this work relative to the events that it narrates, it is significant to note how the author clearly identifies the one mentioned in the 11th century as

Qaṣr al-Mubārak with the “Palace of al-Mu’tamid”, which allows us to endorse this link with the figure of this monarch:

“[Ibn ‘Ammār] He was placed in a high room over the door of the Palace of al-Mu’tamid, known as the blessed Palace -al-Qaṣr al-mubārak-, which subsists until this our time […] but nothing bent al-Mu’tamid and he wounded him with the axe he had in his hand, not ceasing to wound him until he lay dead. He withdrew al-Mu’tamid and had him washed and shrouded; he made the prayers for him and buried him in the blessed Al-Mubārak”

10.

Regarding this same episode, some Arab authors closer in time to the events—such as the already-cited Ibn Jāqān and Ibn Bassām, and even (somewhat later than ‘Abd al-Wāḥid al-Marrākušī) Ibn Jallikān (1211–1282)—also cite this palace with the name of

Qaṣr al-Mubārak, although they differ from the Moroccan compiler about the burial place of Ibn ‘Ammār:

“[Al-Mu’tamid] hit him with the axe, and ordered him to be finished off and taken away and he was hidden with his chains, outside the gate of the palace (al-qaṣar) al-Mubārak, known in Seville as Bāb al-Najal”

11.

Apart from the latter, this association of the ‘Abbādī monarch with the Seville Palace is not exclusive to this particular case, as

Ibn Jallikān (

1868, IV. 457) himself clearly highlights in his biographical dictionary

Kitāb wafayāt al-a’yān (

Book of illustrious men). The Iraqi author records that the Almoravid emir Yūsuf b. Tāšufīn (1062–1106) was amazed by the palaces of al-Mu’taḍid (1042–1069) and his son and successor al-Mu’tamid when he entered the Sevillian capital after the battle of

al-Zallāqa (Sagrajas) in 1086, settling in one of them. We do not know in which one he could have stayed, but it would not be surprising if he did so in the much-acclaimed

Qaṣr al-Mubārak. However, this also allows us to verify the existence of several palaces in Seville in the 11th century, some of which al-Mu’tamid would refer to during his exile in Agmāt, as we have seen.

This event is also mentioned by al-Ḥimyarī (13th–14th centuries) and al-Maqqarī (d. 1632), referring also to al-Mu’tamid’s Palace—this time as Ibn ‘Abbād’s palace—when, around the years 1082–1083, Alfonso VI of León (1065–1109) sent his troops to Seville to besiege the aforementioned palace (

Al-Maqqarī [1843] 2002, II. 289–292)

12. In fact, al-Ḥimyarī adds that it was located in the vicinity of the Guadalquivir, which allows us to know its approximate location, as we can interpret from the following fragment:

“When Alfonso received the news of what Ibn ‘Abbād had done, he swore to his great Gods, that he would go as far as Seville to attack him, and that he would besiege him in his own palace. He put two armies on a warpath; he entrusted the command of one of them to one of the mangy men who served as his generals, and ordered him to set out […] He met him at Triana, where they would carry out their union. For his part, Alfonso, at the head of a second army, quite numerous, took a different path from the one his general was to follow. They both plundered the Muslim territory, sowing ruin and desolation, then they held their meeting at the place set on the edge of the Guadalquivir, in front of the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād”

13.

At this point, we can see how the written documentation tells us about a palace in the context of the 11th century that belonged to the last king of the Sevillian Taifa, by using different expressions such as “Qaṣr al-Mubārak”—mainly in the poetic genre—“palace of al-Mu’tamid”, and “palace of Ibn ‘Abbād”, the latter two being the most used by Arab authors from the 12th century onwards. Therefore, based on this reality and the analysis carried out, we can confirm that it is the same construction. However, all of this contrasts with the absence of any references to the aforementioned palace during the years that al-Andalus was part of the vast Almoravid Empire. It is in the Almohad era that we again find numerous documentary references to this construction, whose authors continue to allude to it in different ways and, moreover, with different functions. For this reason, we consider it essential to compare not only the different versions of the texts that we have, but also to resort to their Arabic editions.

In the first place, the Moroccan compiler Ibn ‘Iḏārī al-Marrākušī (d. after 1313) already confirms in his

Al-bayān al-mugrib fī ijtiṣār ajbār mulūk al-Andalus wa-l-Magrib (

The surprising exposition in the summary of the news of the kings of al-Andalus and the Maghreb) the existence of the palace that we are addressing at that time, referring to it by the name of “palace of Ibn ‘Abbād” as the place where the sheikhs Abū Yaḥyà b. al-Ŷabr and Abū Isḥāq Barrāz settled after their entry into Seville in the mid-12th century:

“[the Almohad armies] (were installed) inside Seville, so that they would be close to the palace (qaṣr) of Ibn ‘Abbād where the (two) Almohad sheikhs Abū Yaḥyà b. al-Ŷabr and Abū Isḥāq Barrāz, the head of the Government (majzan) with the High Command (al-amr al-’alī) resided, and thus they would be (all) the Almohads together with one another”

14.

This aspect leads us to consider a double reality: on the one hand, we can see how the old palace of al-Mu’tamid in Seville was still standing in the middle of the 12th century and, on the other hand, its evident occupational continuity as the most important political–administrative nucleus of the city linked to the court, and which the Almohad sheikhs chose from the beginning as their residence. This demonstrates not only the prominence that the 11th century palace maintained during the following century, but also the clear intention on the part of the Almohads to assume or, rather, to legitimize, their power through what was and continued to be a courtly reference.

Its memory was preserved throughout the period of Almohad domination in the Iberian Peninsula. Hence, it is the chronicler of the Almohad court Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā (d. after 1198) who provides us with the most data, being also aware of the contemporaneity of the events that he narrates and his link with the North African state apparatus. It is in his chronicle Al-mann bi-l-imāma (The divine gift of the imamate) where we not only continue to find numerous references to the palace of al-Mu’tamid as the “palace of Ibn ‘Abbād”, but also find new expressions derived from the versions that we have, and which we consider important to take into account for a later analysis.

As for its location, and as we can interpret from the aforementioned work, Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā coincides in locating the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād in the same place that seems to emerge from the events reported by al-Ḥimyarī and al-Maqqarī on the occasion of the siege undertaken by Alfonso VI. We can see this when the author of Beja narrates how, a few years earlier—specifically, in 1161–1162—the rebel Ibn Abī Ŷa’far was crucified in the sandbank, near the palace of the last king of the Taifa of Seville:

“Upon taking it [Carmona], the Levantine caid Ibn Abī Ŷa’far was caught and was taken in chains to the prison of Seville, and remained there until the obeyed order came that he be crucified. This was done in the sandbank (Rambla), under the citadel or fortress of Ibn ‘Abd in Seville, and the rebellion in Carmona was ended, as I expounded it in History”.

As we can see, the chronicler of the Almohad court specifies more in this regard, indicating that the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād was built in the vicinity of the area then occupied by the sandbank—that is, in the area between the current course of the Guadalquivir, the Puerta de Triana (Triana’s Gate), and the Torre del Oro (Golden Tower), which leads us to validate its location in the vicinity of the river. We even know that in the 11th century the river flowed closer to the primitive nucleus of the city, moving progressively towards the west and leaving space for the urban growth of Seville on this side.

The expression used by Ambrosio Huici Miranda in his translation of the

Mann bi-l-imāma to refer to the palace of al-Mu’tamid as “castle of Ibn ‘Abd” is also significant. However, in the Arabic edition by ‘Abd al-Hādī al-Tāzī of the unique manuscript of this work of

Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā (

1964, p. 185)—preserved in the Bodleian Library (University of Oxford, England), and which the aforementioned Spanish historian and Arabist uses for his Spanish version—we can read “Qaṣr Ibn ‘Abd”, or “fortress of Ibn ‘Abbād”. When writing this, did Huici Miranda want to reflect the fortified character that the latter may have had?

It is in the year 1172 that we again find news of the ancient palace of al-Mu’tamid, but this time endowed with a different function from what we have seen so far. We have evidence through Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā that, after the death of the Levantine emir Ibn Mardanīš (1147–1172), the

Šharq al-Andalus became part of the Almohad Empire, submitting his family to the unitary dogma (

tawḥid) before the caliph Abū Ya’qūb Yūsuf (1163–1184) in Seville, the Andalusian capital. According to the chronicler of Beja, once Hilāl b. Mardanīš recognized the caliph, he was received in the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād—which was noted for its magnificence and spaciousness—while his companions were hosted in houses adjacent to it:

“Hilāl b. Mardanīš bid farewell with his companions, and accommodation was procured for him and his companions. He was received in the magnificent and spacious palace of Muḥammad Ibn ‘Abbād (Mutamid), amir of Seville; his companions were hosted in the adjoining houses, and beds and tapestries and meals and gifts and drinks and everything necessary was provided for them, and they understood that they were the nearest of kin and the closest of friends, and that they were cordially welcomed by the caliphal kingdom and the Imami power”

15.

This was also the case that same year prior to the Huete campaign

16, and even on his return to Seville after the failure of the latter:

“That day the sons of Muhammad b. Mardanīš arrived with him, with their servants and the servants of their father and brothers, as he had commanded them, with the most pompous entrance, and he received them in the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād and in the houses adjoining it, and bought houses for them in Seville, from their owners, to house them.”.

As we can interpret from these facts, the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād was also used by then as a temporary residence of the Banū Mardanīš. This apparently paradoxical reality should not be surprising to us since, in spite of the continuous confrontation that prevailed during the third quarter of the 12th century between the Almohad armies and the Mardanisid troops, the family of the Levantine rebel came to occupy a high position in the court and in the North African military apparatus, as expressed by the aforementioned chronicler of Beja. As a matter of fact, that importance to which we are referring is perfectly confirmed in the conception of this palace as a place destined for the family of Ibn Mardanīš.

At this point, we consider it appropriate to dwell on how the Almohad sheikhs Abū Yaḥyà b. al-Ŷabr and Abū Isḥāq Barrāz chose the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād as the residence and seat of their government in al-Andalus in the middle of the 12th century, which must have continued to maintain, in our opinion, the same functions during the subsequent years, being used later as a place of residence for those delegations that went to Seville to take the oath of recognition (

bay’a) to the caliph. We can see this not only at the end of the 12th century with the Banū Mardanīš, but also with Ibn al-Aḥmar of Granada (1232–1273) who, on the occasion of the renewal of the peace treaty that he maintained with Alfonso X the Wise (1252–1284), was received in the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād upon his arrival in Seville:

“When Ibn al-Aḥmar arrived in Seville, he camped on its outskirts in the Red Cistern, and five hundred chosen horsemen, warlords and captains were with him. Alfonso went out to meet him and conjured him to come to him; he entered and stayed in the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād and the two main leaders sons of Ašqīlūlā, Abū Muḥammad and Abū Isḥāq, entered with him […] When Ibn al-Aḥmar entered and settled, the Christians built a high palisade in the street where he stayed, they built it at night and it remained nailed before the houses in such a way that it prevented the horses from passing”.

Considering all these facts, could we think that, just as we have anticipated, the Almoravid emir Yūsuf b. Tāšufīn could have also settled in the Qaṣr al-Mubārak after the battle of al-Zallāqa? Everything seems to indicate that the “magnificent and spacious palace of Muḥammad Ibn ‘Abbād”—as previously remarked by Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā—was endowed with different spaces with very diverse functions linked to the court, leading us to raise the following questions: On the one hand, which was the area of government or official representation where Hilāl b. Mardanīš and the rest of his companions submitted to the Almohad tawḥid? And, on the other hand, where did the Almohad caliph reside if the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād was the place where the Banū Mardanīš and, later, Ibn al- al-Aḥmar stayed?

Regarding the first of these questions, the aforementioned Almohad chronicler refers in his work to the “old castle” as the place where Hilāl b. Mardanīš was received in April 1172 by the caliph Abū Ya’qūb Yūsuf to proceed to his recognition:

“He [Hilāl b. Mardanīš] arrived with all his brothers and with the supporters of his father, the caids and the greatest ones of the military border, at the coming of Ramadan of this year (begins April 27, 1172). The Amīr al-Mu’minīn sent to his encounter, his brother the illustrious Sayyid Abū Zakariyā’ Yahyà, son of the caliph ‘Abd al-Mu’min, lord of Béjaïa, and also his other brother, Abū Ībrāhīm Isma’īl [….] He entered in his company into the ancient castle at the reception of the caliph, close to the evening prayer on the day of his arrival, and then the new moon (hilāl) of Ramadān of the year 567 appeared. He greeted the caliph Abū Ya’qūb and recognized him in the presence of all the Sayyids, the illustrious Sayyid Abū Ḥafṣ and all the brothers and sheikhs of the Almohads and the ṭālibes of the court”.

So did the rest of the personalities and military who arrived with him in Seville the following day. Moreover, it is precisely in this “ancient castle” that the audience room was to be found that, consequently, would form part of the protocol area, as we can interpret from the following words:

“When the first day of the month of Ramadān (April 27) dawned, the sheikhs of the Almohads and all the people, and the ṭālibes of the capital, rose early to attend the reconnaissance of the people of Levant, already mentioned. When the caliph, Amīr al-Mu’minīn, was seated on his lofty and noble throne, the vizier Abū-’Alà Idrīs b. Ŷā’mi’ came out and commanded them to enter and present themselves before him. They entered and saluted with a general greeting. Then they paid homage to him one after another, preceded by their sheik Abū ‘Uṯmān Sa’īd b. ‘Isā, chief of the aforementioned soldiers and lord of the border, pledged themselves to obedience and entered the (Almohad) community”.

(ibid., p. 194)

Regarding the Arabic version (

Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā 1964, p. 472), it names the castle as

qaṣaba al-’atiqa (ancient fortress or

qaṣaba), which leads us to think of a fortified construction as a place chosen for this type of ceremony and, in addition, endowed with a certain antiquity when compared to other similar buildings contemporary to these events. As we know, the Sevillian capital witnessed an important urban transformation after the Almohads entered the city—mainly in its southern sector. We have evidence through the

Bayān al-mugrib of Ibn ‘Iḏārī al-Marrākušī of the construction of a first fortress around 1150 to take in the North African armies that accompanied the sheikhs Abū Yaḥyà b. al-Ŷabr and Abū Isḥāq Barrāz on the occasion of the disputes that originated with the Andalusian population:

“[…] they agreed to build a fortress for the Almohads residing in (the neighborhood of the Cemetery) al-ŷabbāna would move to it, due to the complaints of the people against the harm they caused, after which, they determined a place (for that fortress) -the same one in which it is today-, removing its inhabitants from their houses and compensating them in the medina with other houses of the Government (majzan)… (The Almohads) demolished the wall of Ibn ‘Abbād and with its stones they built that fortress […]”

17.

This fortress must have been built in the vicinity of the foundational site of the Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville), and it was extended to the west during the first years of the Almohad occupation of the city (

González Cavero 2018, pp. 126–56); however, we do not have further data about it. What there is no doubt about is the frequent differentiation in the Islamic world regarding this type of construction. We refer to the existence of a palace (

qaṣr) as the residence of the sovereign and an important area of representation inside a larger fortified space delimited by the fortress (

qaṣaba), the latter term being understood as the wall itself that encloses all of that territory. In our opinion, we must take this aspect into account to understand the reality of Ibn ‘Abbād’s palace.

However, to the above, we must add that Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā himself seems to be referring to another fortress a year later, on the occasion of the act of congratulating the caliph Abū Ya’qūb Yūsuf after the battle against the Christians of Avila:

“Amīr al-Mu’minīn sat down and his brother the illustrious Sayyid Abū Ḥafṣ sat down with him, on Saturday the 22nd (April 8) at sunrise, for the blessed congratulatory ceremony in his palace, inside the fortress of Seville. The Almohads and the sheikhs of the ṭālibes of the court and the alfaquis and the secretaries and the preachers were ordained, and those who came to the gate (of the palace) for the congratulatory ceremony were presented and authorized, as they entered by their literary and poetic categories [….] Then the Amīr al-Mu’minīn was recognized, following this, and all of those present kissed his blessed hand and the joy was completed with this, and this marks the beginning of the many conquests that followed”.

It is possibly the latter to which the chronicler of the Almohad court refers when Abū Ya’qūb Yūsuf ordered the governor of Seville Abū Dāwūd Yalūl b. Ŷaldāsan to build a strong wall “in the fortress of Seville that would pass from the beginning of its construction in front of the esplanade of Ibn Jaldūn, inside Seville, and to raise the minaret of the mosque, which would be at the junction of the wall with said mosque” (

Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā 1969, p. 200) in the year 1184

18. This represents a new fortress that we can identify with the one referred to by historiographers as the “inner fortress” (

González Cavero 2018, pp. 217–33), and which would comprise the space between the palatine complex and the mosque (

masŷīd al-ŷami’) (

Figure 2, Enclosures VI and VII). This fortress may have been completed in 1172, once Abū Ya’qūb Yūsuf managed to consolidate his position in al-Andalus after the subjugation of the Banū Mardanīš, as part of the constructive enterprise conceived by the Almohads in this sector of the city (

Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā 1964, p. 474;

Roldán Castro 2002, p. 15).

If so, could we relate the

qaṣaba al-’atiqa with the primitive enclosure of the Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville) that was included in the aforementioned “inner fortress” and that has traditionally been associated with the

Dār al-Imāra of the 10th century? For his part,

Leopoldo Torres Balbás (

1949, p. 30) had already identified the walls and towers of the fortress with the “old fortress” referred to at the end of the 12th century. Even

Antonio Almagro Gorbea (

2015a, p. 11) affirms that the oldest area would be defined by the layout of its walls built from ashlars, while the most recent ones would be built from mud or brick.

We will return to this question later but, responding to the model of this type of construction to which we referred earlier, it is significant to note how Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā specifies that the congratulatory session took place “in its palace, within the fortress of Seville”, which leads us to think that, indeed, we could be looking at a palatine complex integrated into this new defensive area. This was suggested by

Melchor Martínez Antuña (

1930, pp. 69–70)

19, based on the unique manuscript of the Bodleian Library, in which he adds “the hall on the right of the palace was the one destined by the caliph Yúsuf for tribute receptions and celebration ceremonies” (ibid., note 1, p. 70). In our opinion, this hall could be the same one mentioned by Ibn ‘Iḏārī al-Marrākušī in narrating the act of recognition of Hilāl b. Mardanīš

20 which, as we know, he draws from the chronicle of Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā. Therefore, considering all of these data, we should not rule out the possibility that the

qaṣaba al-’atiqa was the same primitive palace (

González Cavero 2018, p. 160), with Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā using this expression in a punctual way to differentiate it from those more recent Almohad constructions and, in turn, legitimize the Mu’minī dynasty in al-Andalus.

All of this allows us to return to the second question that we previously mentioned about which could have been the palace where the Almohad caliphs resided; however, we only have brief allusions that can bring us closer to its possible location. This is the case of the construction of the

sābāṭ of the mosque in Seville that allowed “the caliph to go out through it, from the palace to this mosque to attend Friday prayers” (

Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā 1969, p. 197;

1964, pp. 477–78). We know that the qibla wall was located in front of the northern wall of the primitive enclosure of the Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville), providing initial evidence that the latter fulfilled that function. In addition, and when speaking of the works of the

Buḥayra of Seville, it is likely that the chronicler of Beja is referring to this again when he states that the “Amīr al-Mu’minīn would leave his palace in Seville, on horseback, with the Almohad chiefs to inspect the work and field and to recreate himself with its pleasing view” (

Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā 1969, p. 189;

1964, p. 466), indicating that he was in the city itself.

Apart from these data on the palace, it always comes to our attention that an author such as Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā—the official chronicler of the Almohad court—does not dwell on the reforms or ex novo constructions that were carried out at that time in the present Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville)—as we can confirm from the material evidence available to us. However, this contrasts with the detailed descriptions he gives of other civil, palatine, or religious works. This is the case of the ancient Roman aqueduct that came from Alcalá de Guadaíra, the palaces of the Buḥayra, or the mosque.

We even have evidence from written documentation that Seville, as the Almohad Andalusian capital, became the temporary residence of the caliphs during the periods that they spent in the Iberian Peninsula at the moment of supervising the works that were being carried out in the city, or in order to prepare their military campaigns against the Christians (

González Cavero 2018, pp. 100–6). Nevertheless, at no time do the authors explicitly mention the place where they settled after their arrival from the official court in Marrakech. We only know that the caliph Abū Yūsuf Ya’qūb al-Manṣūr (1184–1199) ordered the court to be moved to the outskirts of the Sevillian capital, as specifically mentioned in the

Ḥiṣn al-Faraŷ (ibid., pp. 250–57).

Consequently, and in spite of this lack of data, there is no doubt that the temporary residence of the caliphs had to be at the place that the Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville) occupies today, taking into account that, during the years in which the city became the Almohad Andalusian capital, the political–religious nucleus had already moved to its southern sector. It would even be logical to think that the residence of the caliphs was located in the vicinity of the protocol area for ceremonial reasons, being able to place it in the same

qaṣaba al-’atiqa and in which the much-acclaimed

Qaṣr al-Mubārak of the 11th century may have been found. A palace that survived between the 12th and 13th centuries with a political–administrative and, in turn, residential function, leads us to question the state it was in at that time, as there was evidence of the reuse of “the stone called «Taŷūn al-’ādī’”», taken from the wall of the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād [

surqasr Ibn Abd]” (

Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā 1969, p. 201;

1964, p. 482) for the construction of the minaret of the new mosque. As we can read, the palace was surrounded by a wall of stone ashlars—a reality already recorded by the poet Abū Ŷa’far b. Aḥmad in his

Risāla (

Epistle) (

Lledó Carrascosa 1986, p. 197).

3. Recovery and Restitution of the Primitive Palace of the Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville)

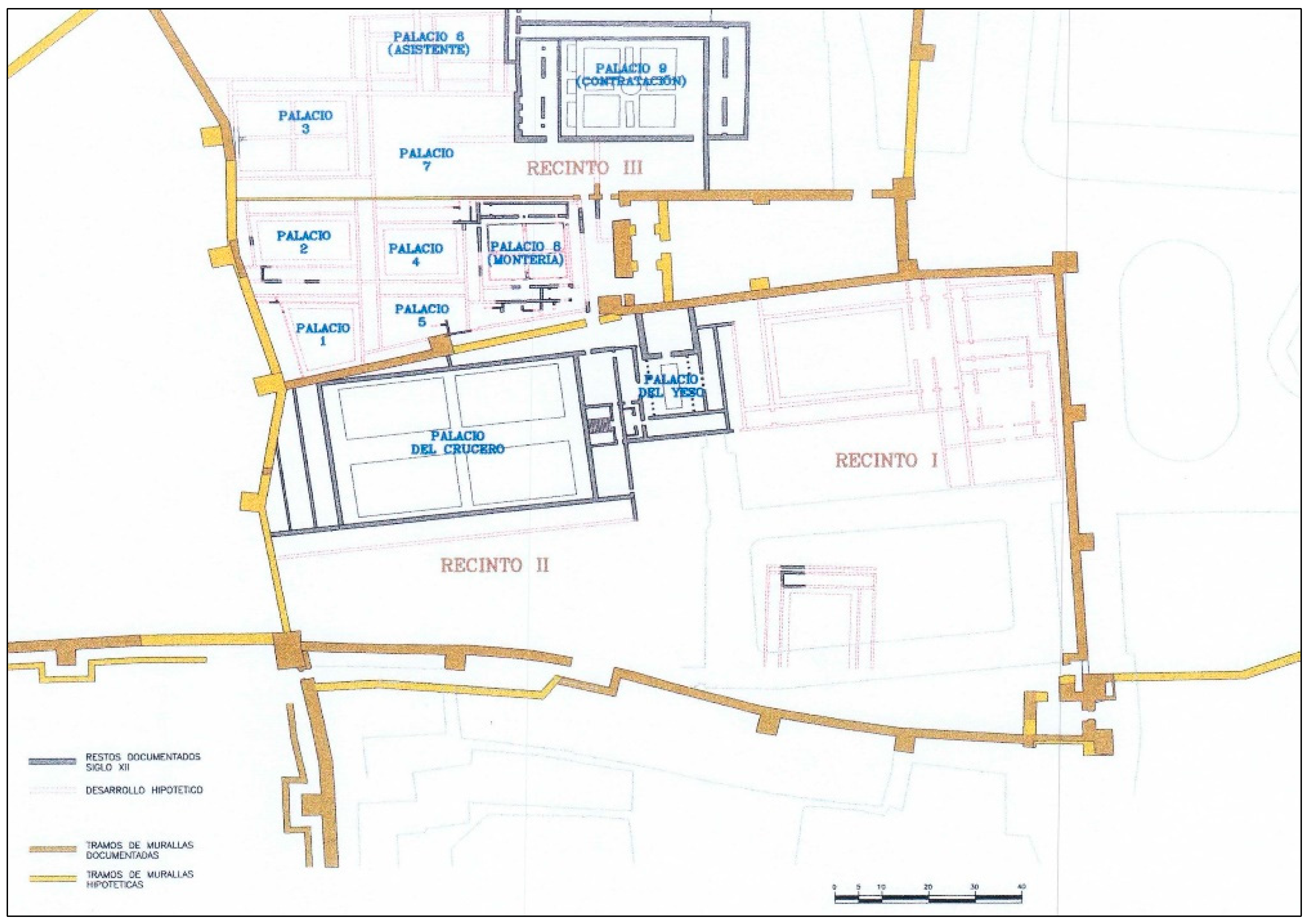

In addition to the different documentary sources that we have about this palace and the studies carried out thereon, the findings derived from the archaeological interventions that have taken place in recent years are of great importance to try to answer a question that, for some time, has been raised in the research about the Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville): where was the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād located? We have already seen how everything seems to point to its possible location in the old enclosure of the Sevillian palace and fortress (Enclosures I and II), destroyed or hidden by later constructions and reforms that, from the same 12th century, followed one after the other until the end of the 19th century.

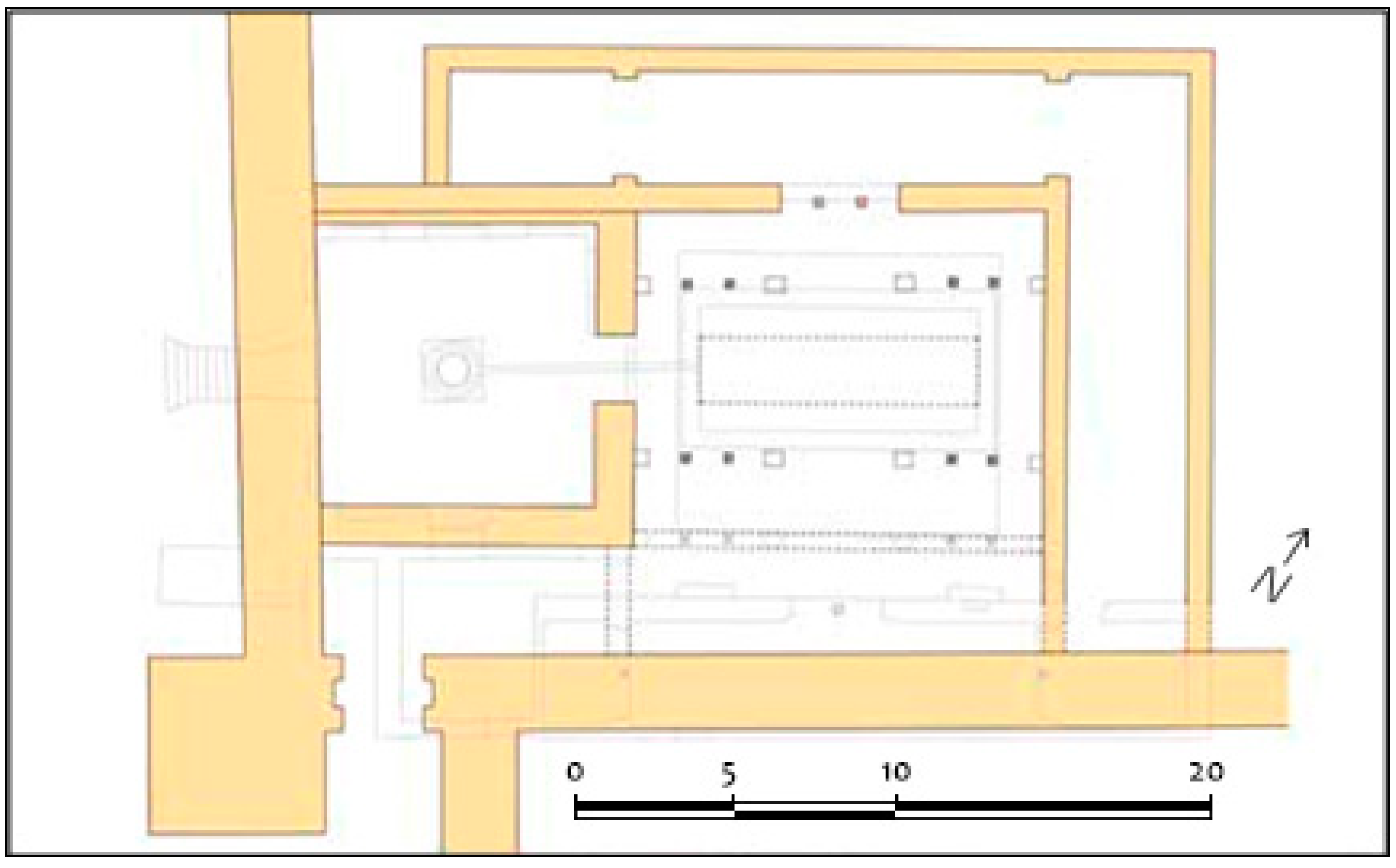

Therefore, ruling out the widespread theory that the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak was located in the place now occupied by the Palace of Pedro I and its immediate surroundings, the preventive work undertaken between 2013 and 2018 under the direction of Miguel Ángel Tabales Rodríguez for the restoration of houses no. 7 and 8 of the Patio de Banderas (Courtyard of Flags) (Enclosure I) allowed the partial recovery of the remains of a palace of some consideration and entity (

Figure 3). Over the course of time, the latter was segregated and transformed—mainly in the 19th century—into the properties located in the western sector of the aforementioned courtyard, being dated between the end of the 11th century and the beginning of the 12th century. Even this (apparently hidden) importance has been evidenced throughout the centuries by its particular use, to which must be added the proportions that it possesses and the choice of its location with respect to the rest of the fortified complex.

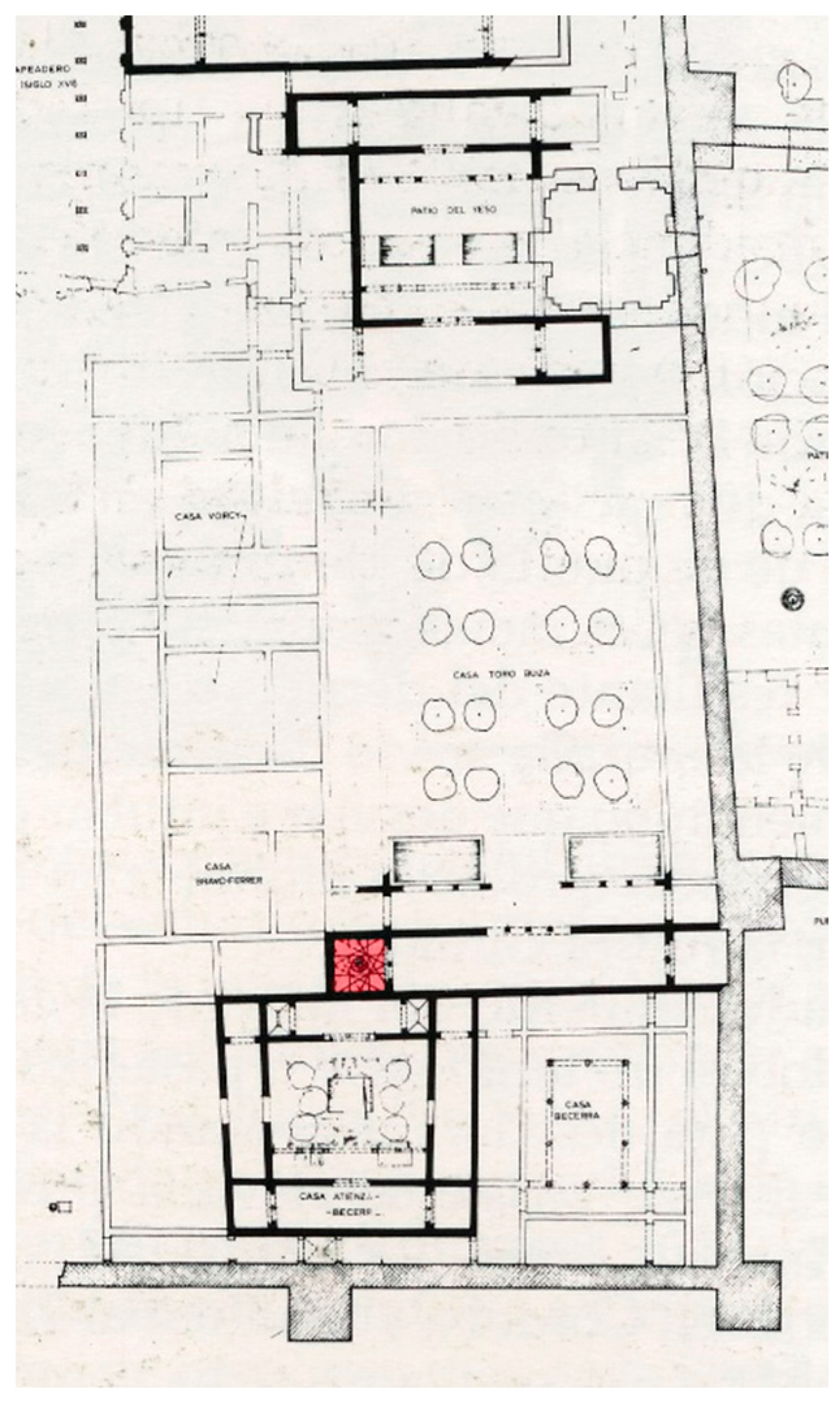

As some authors have already pointed out, the first graphic testimony about this space that has become available to us is the plan of the Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville) attributed to the Milanese architect Vermondo Resta (1608), in which we can appreciate the configuration of a transept garden that formed part—as it appears in writing—of the so-called “quarto del alcayde” (throne room) (

Figure 4). Its imprint denotes the relevance that this reserved area must have had, in modern times, to the residence of the Alcaide (Governor) of the palace (

Vargas Lorenzo 2019, p. 31;

2020a, p. 251) and the inheritor, in our opinion, of its medieval past

21. This is supported by the written documentation itself, through which we know that King Pedro I of Castile (1350–1369) was in the “palace that they say is of iron” (

López de Ayala 1779, p. 240) when he ordered the assassination of his brother, the Master of Santiago Don Fadrique, in the vicinity in 1358.

This “palace” must have been none other than the “quarto de los yessos” (gypsum room) that Vermondo Resta identifies in his floor plan and that, in the 17th century, was already differentiated and independent from the “quarto del alcayde” (throne room), possibly due to the transformations to which this sector was exposed, as we have already mentioned. However, it is significant that in the 14th century the Castilian monarch had a space of such reduced dimensions as his residence, so it would be expected that at that time the “quarto de los yessos” (gypsum room) occupied a larger area and included the “quarto del Alcayde” (throne room). Furthermore, we know from Pedro López de Ayala that Doña María de Padilla was in the “Cuarto del Caracol” (Spiral Room)—built in the southern end of the Cuarto Real (Royal Bedroom) or del Crucero (Crossing Room)—when the murder of Don Fadrique took place (ibid., pp. 239, 241), so everything leads us to believe that this palatial area was her place of residence, leaving the “quarto de los yessos” for the exclusive use of the monarch.

In fact, from the plan drawn up in 1759 by the engineer Sebastián van der Borcht (

Figure 5a,b), we can derive an idea of what the whole area might have been like, and in which we can already sense the layout of a palace with clear Islamic roots—despite the alterations that took place in it (

Manzano Martos 1999, p. 65;

Almagro Gorbea 2015a, p. 13)—that Pedro I must have occupied during his stay in Seville while his great construction enterprise was being carried out in its vicinity. In this sense, at the end of the 20th century,

Rafael Manzano Martos (

1995a, p. 117;

1995b, p. 346) distinguished the remains of this construction, recreating its plan (

Figure 6) and dating it to the Almohad period, as did other specialists (

Torres Balbás 1949, pp. 30–31;

Almagro Gorbea 2013, pp. 89–90).

However, in addition, the existence of a vault of interlaced arches in house no. 3 of the Patio de Banderas (Courtyard of Flags)—made known by José Gestoso y Pérez at the end of the 19th century, and whose construction he attributed to this same period (

Gestoso y Pérez [1889] 1984, I. 324–325;

[1884] 1914, p. 71)—supports this approach. Regardless of its chronology, it is interesting to note how the aforementioned Sevillian art historian and archaeologist had already suggested its possible link with the Palacio del Yeso (Gypsum Palace), referring to it as a vestige of the primitive palace. Therefore, it is logical to think that in this place there was a palatine area that, due to its dimensions, must have had a great importance in the context of this entire fortified complex—perhaps even thinking that it could be part of the much-acclaimed ’Abbādī palace mentioned in the Arab sources (

González Cavero 2018, pp. 199–217).

At this point, the investigations carried out in recent years in this entire area have allowed us to partially corroborate this approach, in addition to suggesting a new constructive process for the origin of the fortress. According to the results obtained from archaeological interventions and studies carried out previously (

Tabales Rodríguez 2013, pp. 99–102;

2020a, pp. 53–113;

Tabales Rodríguez and Gurriarán Daza 2021, pp. 1–15;

Tabales Rodríguez and Vargas Lorenzo 2014, pp. 16–22;

2017, pp. 198–203;

2020, pp. 21–61;

Vargas Lorenzo 2019, pp. 10–13), its walls were built over an 11th century neighborhood outside the walls, eliminating some of the pottery and houses that were part of it (

Hernández Souza 2014, pp. 67–70), and many of these constructions survived in its vicinity until the mid-12th century. It was already in the Almohad period when the southern urban reform of Seville and the expansion of the fortress to the west took place. Currently, the emerging remains that have been preserved from that first moment—and that have traditionally been linked to the

Dār al-Imāra of the 10th century—correspond to the northern and western walls of the Patio de Banderas (Courtyard of Flags), built from stone ashlars possibly taken from the old Roman wall of the city. This first fortified enclosure had a quadrangular plan, and its axial entrance to the east was flanked by two towers (

Tabales Rodríguez 2002a;

Gurriarán Daza and Márquez Bueno 2020, pp. 115–49).

It is precisely in its interior where the remains of the aforementioned palace are found—specifically on the western side of the Patio de Banderas (Courtyard of Flags)—where work carried out in recent years by Miguel Ángel Tabales and Cristina Vargas has allowed not only the recovery of some of its constructive and decorative elements

22, but also a hypothetical restitution of how it could have been (

Tabales Rodríguez and Vargas Lorenzo 2014, pp. 10–33;

2017, pp. 210–15;

Vargas Lorenzo 2019, pp. 1–40;

2020a, pp. 209–58) (

Figure 7a,b). We refer to the existence of a tradition caliphal geminate arcade with its corresponding polychromy that opens to what was the western room of the north hall—the northern headwall of which has been preserved, along with some pieces of its ceiling with sunk panels and the foundations of several brick pillars that supported the portico that preceded it. At the same time, a small void with fragments of plasterwork was found in the south wall of the north room, which has been interpreted as one of the three arches that could have opened over the access to the latter to provide the interior with better lighting and ventilation. As for the garden space, it was possible to document the start of a series of arches—currently blinded—in its northwest closing wall and part of a pool that was located in the north front, as well as the partial remains of a central fountain and of the perimeter platforms that delimited it.

Based on these testimonies, the aforementioned authors have proposed that we are talking about a palace of considerable dimensions, very similar to those of the old palace of the Casa de Contratación of Seville (House of Trade) (

Jiménez Hernández 2015, pp. 24–25)—that is, 30.48 m × 42.67 m, with its eastern side being slightly smaller. In turn, it must have had a sunken transept garden whose flowerbeds had a 2.5 m difference in level with respect to the walkways of the palace complex. This landscaped space was equipped with a central fountain at the intersection of its platforms and a pool on the north front, occupying the central axis and flanked by four brick arches—currently blinded—on the north wall of these quadrants, with a purely decorative function. Regarding the latter, and according to the studies carried out previously, no access to the palace has been found thus far from these arcades, whose arches have a thickness of 0.05 m (

Vargas Lorenzo 2019, p. 26;

2020a, p. 240).

Although with certain variants and at different scales, this last arrangement can already be seen in other sectors of the Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville)—as is the case of the Cuarto Real (Royal Bedroom) or the Crucero (Crossing), where a sequence of slightly pointed arches is repeated on four sides to bridge a natural difference in level of almost 5 m, forming a walkable gallery around its entire perimeter; in the second construction stage of the patio of the old Casa de Contratación (House of Trade), with double-blind arches, pointed and tumid, in which the paintings of some doors are still preserved; and in the Patio de las Doncellas of the Palace of Pedro I, in which a succession of a semicircular arches—also blind—intertwine with one another forming, in turn, a series of pointed arches.

As we can interpret from all of these examples, the influence that the different palatine spaces received from one another and from different periods is evident, with their proximity being an essential factor. As in the Cuarto Real (Royal Bedroom) or the Crucero (Crossing), the existing topographic unevenness in the north–south axis of the palace under study (

Tabales Rodríguez and Vargas Lorenzo 2017, p. 212;

2020, p. 41;

Vargas Lorenzo 2019, p. 18;

2020a, p. 229) could have contributed to the depth of the flowerbeds being so pronounced, arranging that sequence of arches in its walls for a greater articulation of the latter and, thus, configuring practicable galleries around its perimeter. In this sense, it would be logical to think that these arcades were repeated in the fronts of the four spaces destined for the vegetation, although we do not know whether this was truly the case. If not, we should remember that in the first Almohad patio of the old Casa de Contratación in Seville, the walls of the flowerbeds have mural paintings with motifs of multifoil arches with leaves—very similar to those that we find incised in the spandrels of the geminate arches that allow access to the southern hall of the Patio del Yeso (Gypsum Courtyard)—so we could not rule out this possibility either. In any case, the aforementioned authors note that this palace must have served as inspiration for the Cuarto Real (Royal Bedroom) or the Cuarto del Crucero (Crossing Room).

Continuing with the 11th century palace garden,

Antonio Almagro Gorbea (

2015a, p. 12) takes the plan of Vermondo Resta as a reference to emphasize the presence of a central fountain at the intersection of the platforms during modern times, which we know—from the archaeological interventions carried out—replaced the one in the Islamic palace, as can be seen in the graphical documentation collected (

Vargas Lorenzo 2019, p. 26, Figure 28;

2020a, p. 241, Figure 26). This reality is further evidence of the transformation that this entire area underwent but that, in a certain way, continued to maintain its primitive configuration, which would allow us to derive an idea of the original layout of the garden.

A similar thing happened with the northern pool, although, in the opinion of the aforementioned specialist, it was moved to its northeastern end due to the possible partitioning of the arches of the northern portico in the Christian period and the subsequent construction of a new porticoed gallery (

Almagro Gorbea 2015a, pp. 12–13). In this way, this sector was made more habitable, which led to a reduction in the surface area of the courtyard on this side, altering the entire area. This is also shown in the plan of Sebastián van der Borcht. However, according to the aforementioned specialist, it is possible that the absence of the central fountain in the latter was due to some oversight since, in later floors, it still appears. This practice in the Christian period of fitting out more spaces, thereby reducing the garden, can already be seen in the Cuarto Real (Royal Room) or the Crucero (Crossing)—specifically on the south side, with the construction of the Palacio del Caracol (Spiral Palace)—and also in the old Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) of Seville, in both the north and south sectors. The main objective of these interventions after the Christian conquest was to provide these palaces with a greater number of rooms to meet the needs of the new court (

Almagro Gorbea 1999, pp. 345–47;

2007b, pp. 193–99).

However, also noteworthy is the absence of another pool on the southern front of the palace under study—as we can see in the

Qaṣr b. Sa’ad of Murcia (1147–1172)—or in the first Almohad courtyard of the old Casa de Contratación (House of Trade), and that the garden of the 17th and 18th centuries did not have one either. It is possible that, as was the case on the northern side and in the aforementioned courtyard of the old Casa de Contratación (House of Trade), the Christian reform had buried it to provide the whole complex with more practicable spaces, following the processes described above, or that the works were the reason for its complete destruction. Even Miguel Ángel Tabales and Cristina Vargas (

Tabales Rodríguez and Vargas Lorenzo 2014, p. 16) mention the loss of many of the remains of the 11th century palace as a consequence of its contemporary over-excavation. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that this construction had only one pool, as is the case in the palace of Onda, Castellón (11th century) (

Navarro Palazón and Estall I Poles 2011, pp. 74–83;

Garrido Carretero 2013, pp. 35–41)—although in this case the pool is located on the southern front—or in the palace of ‘Alī b. Yūsuf, Marrakech (12th century) (

Meunié 1952, pp. 27–32), examples used by Bernabé Cabañero Subiza in his study to date the Sevillian palace from the end of the 11th century (

Cabañero Subiza 2020, p. 346), where it was also placed by

Tabales Rodríguez and Vargas Lorenzo (

2014, p. 32). However, it is significant that, in the case of Onda, the pool is located on the south side, taking into account the importance of the northern halls in Andalusian palatial architecture.

Based on the research carried out previously, a portico opened onto the garden on its north side which, together with the main hall that it preceded, was located 1.30 m above the landscaped space, occupying a privileged place with respect to the rest of the complex and, therefore, being considered the noblest area of the palace (

Tabales Rodríguez 2020b, p. 262;

Almagro Gorbea 2015a, p. 13). This conception of political propaganda taking advantage of the natural promontory on which the latter was erected, in addition to the foundation included, can already be seen in the

Dār al-Mūlk of

Madīnat al-Zahrā’—the residence of the caliph that was built in the highest area of the palatine city, taking advantage of the topography of the terrain.

The finding of the foundational pillars that might correspond to two of the western columns of the portico has allowed the authors to restore the sequence of its arcade, equipped with a central arch of greater span and fleche, flanked by two sections—each with a triple arcade and separated by brick pillars. Rafael Manzano Martos had already drawn a series of pillars (see

Figure 6) that, as far as can be deduced from his reading, do not coincide in plan with the recent proposal of Miguel Ángel Tabales and Cristina Vargas. However, the scarcity of the preserved material evidence makes it difficult to determine its elevation, with specialists using similar models for its restitution, and bearing in mind the intervention carried out in the Almohad period in the old Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) and the Patio del Yeso.

In the same way, the remains of lateral buttresses belonging to the access of the north hall, along with those of a foundational pillar located at a distance of two meters from the western jamb, have led the aforementioned authors to suggest the possible existence of a triple arcade, unlike what we can see in Rafael Manzano’s plan, with a possible caliphal-style horseshoe on which three small arches would open, and whose compositional scheme we can appreciate in the northern face of the Patio del Yeso (

Figure 8). If this is the case, we find ourselves before a trifora that—as is the case in the southern pavilion of the Taifa palace of the fortress of Málaga, as well as in the palace of al-Ma’mūn of Toledo—recalls the models of

Madīnat al-Zahrā’, focusing during this time on the Umayyad caliphate of Córdoba, with a clear symbolic intention of legitimization by the Taifa monarchs (

Calvo Capilla 2011, pp. 69–92). Also in the Hall of Ambassadors of the Christian palace of Pedro I in the Reales Alcázares of Seville appear three trifora, using columns and capitals from

Madīnat al-Zahrā’ or from some earlier Almohad palace in this same place.

This idea indisputably underlies the vault of interlaced arches with mocárabes in its keystone that covers what was the eastern room of this hall as a

qubba (

Figure 9). Within it opens a framed geminate arcade (

Figure 10)—also of clear caliphal origin—now belonging to house no. 3 of the Patio de Banderas. As we have already mentioned, José Gestoso y Pérez linked the construction of this vault to the Almohad period, taking into account the architectural context in which it was inscribed, followed by Leopoldo Torres Balbás and other more recent researchers

23. However, given its formal similarities with the vault that covers the space preceding the façade of the

miḥrāb of the mosque of Tremecén (Algeria), the latter suggested that its construction could have been related to the years of Almoravid presence in the Iberian Peninsula (

Torres Balbás 1949, p. 31;

1955, p. 40), towards whose ascription around the late 11th and early 12th century some specialists have positioned themselves more recently by relating it to the testimonies found in the corresponding north hall of the Sevillian palace (

Tabales Rodríguez and Vargas Lorenzo 2014, p. 30;

2017, p. 214;

Almagro Gorbea 2015b, pp. 236, 250, 253–54). It has even been suggested that it could be a construction typical of the Taifa period (

Cabañero Subiza 2020, pp. 333–34), given its similarities with the disappeared vault of the hot water room of the Aljafería (

Torres Balbás 1952, pp. 188–90) and the existence of loop-shaped ornaments of Islamic origin in the keystone of the vaults of the palace of Zaragoza, the palace of Balaguer, and, according to al-’Uḏrī (1003–1085), in a room of the palace of the Fortress of Almería—although according to

Alicia Carrillo Calderero (

2009, p. 522), the Almerian geographer placed them in a ceremonial hall of one of the palaces of the governor Muḥammad b. Ṣumādiḥ al-Mu’tasim-.

In any case, the reminiscence of the 10th century is evident, and even the reuse of materials from this period, as can be seen in the shaft and base of the column that make up the geminated access to the room. In addition, the occupational continuity of the palace can be appreciated in the pictorial decoration of that arcade—based on vegetal, geometric, and epigraphic motifs, and emblems of Castile and León on the spandrels (

González Cavero 2018, pp. 213–14)—and in the original alteration of the vault of interlaced arches, with the removal of the latter and the addition of a molding in modern times (

Almagro Gorbea 2011, pp. 48–51). All of these aspects make a more precise dating difficult, and a more detailed study would be required in order for us to specify its chronology.

However, one of the most significant contributions of the interventions carried out in the sector of houses no. 7–8 of the Patio de Banderas that could help answer this question was the recovery of the western geminate arcade of the northern hall (

Figure 11). Together with the one on its opposite side, they opened onto lateral rooms that flanked a central rectangular space whose original wooden ceiling has been partially preserved. According to the research carried out previously (

Vargas Lorenzo 2019, pp. 27–31;

2020a, pp. 244–49), the western arcade has the same decorative motifs that we have just seen, whose analysis has not yet allowed us to define an approximate date for their execution, although it was initially considered that these paintings could date back to the time of this palace’s construction—that is, between the late 11th century and the early 12th century (

Tabales Rodríguez and Vargas Lorenzo 2014, p. 30;

2017, p. 214).

Given this lack of precision that we have noted, it has been suggested that the entire pictorial ensemble could correspond to the 14th century, as a result of the reform work carried out after the damage caused by the earthquake of 1356; this would explain not only the lack of precision in its elaboration, but also the homogeneity of the pictorial strata in the words of the specialists

24. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that—except for the heraldry and the inscription on the framing—it was made during the last years of the reign of al-Mu’tamid, or even that it was replaced during the Christian period.

In this sense, it is striking that in the 14th century tempera painting was used exclusively for the decoration of these arches, rather than plasterwork

25 as in the Patio del Sol (Sun Courtyard), for example (

Blasco López and Alejandre Sánchez 2013, pp. 175–82)—a space that belonged to the primitive enclosure of the Royal Alcazars of Seville, and which it seems had a late medieval arcade constructed from this material, pending further progress in the dating of this plasterwork (

Baceiredo Rodríguez 2014, pp. 109–30)—or in the current Sala de Justicia (Hall of Justice), in whose place there may have been a similar previous construction that was renovated in the 14th century (

González Cavero 2011, pp. 279–93). We even know that in 1554 the aforementioned “quarto de los yessos” (gypsum room) had plasterwork ornamentation (

Gestoso y Pérez [1889] 1984, I. 517–518;

Marín Fidalgo 1990, I. 148 and 250), possibly built in the previous century.

While waiting for new research to provide more information about the decoration of these arcades—as well as the existence (or not) of another vault of interlaced arches in the western room of the hall, as has also been suggested—it is significant to note how the motifs of the castle and the rampant lions are further indications that allow us to confirm the occupation of this palace after the conquest of the city by Fernando III (1217–1252) in 1248. To this, we must add the importance of the north hall as a possible protocol or representation area—a reality that would support the use of this palatine complex by the new Christian monarchs, as we have had occasion to comment on the assassination of the Infante don Fadrique.

Another aspect that deserves special attention for a better understanding of the functionality of this palace is the existence of a series of modern houses on its northern and eastern sides, which were identified in the 1990s with the names of their tenants, and to which an Almohad origin was already attributed (

Manzano Martos 1999, pp. 65, 72–73). We refer to the “Casa Vorcy”, “Casa Bravo-Ferrer”, “Casa Atienza-Becerril”, and “Casa Becerra”—the latter two bordering the north wall of the hall to which we have just referred

26, as we can see in Sebastián van der Borcht’s plan. However, it is precisely the “Casa Atienza-Becerril”—currently house no. 2 of the Patio de Banderas—that preserves some interesting remains that allow us to corroborate that they could have been part of this palace as private residences, used by the monarch or caliph. This house conforms to the prototype of Andalusian domestic architecture, with a central garden surrounded by a platform and a small canal, and with two pools facing one another on the north and south flanks that precede two rectangular halls with rooms; there may also have been other similar pools on the east and west sides (ibid., pp. 72–73;

Almagro Gorbea 2015a, p. 13).

Everything seems to indicate that the accesses found in the recovery of the western sector of the north hall should correspond to the communication systems between the latter and the northern homes, although these have not yet been archaeologically documented (

Tabales Rodríguez and Vargas Lorenzo 2014, p. 11;

Vargas Lorenzo 2019, p. 17;

2020a, p. 226). This gives greater meaning to this area of representation, whose hall the ruler would access directly from his private rooms to officiate any kind of ceremonial act. In this vein,

Bernabé Cabañero Subiza (

2020, pp. 341–45) establishes a similarity between the building layouts of the mosque of Cordoba, the Aljafería of Zaragoza, and the Sevillian palace, and in the center of the main hall of the latter there may also have been some evocation of the

miḥrāb of the Cordovan mosque, whose space was reserved for the high dignitaries of the court, as we know was the case in the

Maŷlis al-Šarqī (Eastern Hall) of

Madīnat al-Zahrā’ (

Abad Castro 2009, p. 27, note 27). In the opinion of the aforementioned author, his relatives, members of the court, poets, and musicians, among others, would have been the first to enter the hall through the triple arcade and would be placed—in the same way as in the ḥudī palace—flanking the Taifa monarch, who would enter last, unlike what happened in Zaragoza. Once the ceremony was over, the protocol would be carried out in reverse, with the leader exiting first, followed by the rest of the guests and people linked to the court.

Although we do not have explicit information from the Arab sources about how the royal ceremonies may have taken place in the primitive palace of the Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville) during the 11th century, in the Aljafería of Zaragoza, both the north portico and the access to the audience hall that precedes it were built with four arches with double columns in the central axis that prevented the monarch from being seen by his attendants; thus, he remained semi-hidden during the act, in keeping with the ‘Abbasid and Fatimid tradition (

Cabañero Subiza 2012, p. 238;

2020, p. 322). In the case of the Sevillian palace, it seems that this architectural resource did not exist, since the connection between the portico and the hall was made through a triple arcade in which the central arch opened directly to the space that the ruler was to occupy in the hall.

However, we should not rule out the possibility that this architectural solution was the result of a possible intervention in Almohad times to achieve a greater visual closeness of the caliph to his subjects according to his purposes, returning to the Umayyad tradition (

Barceló 1995, pp. 153–75) with this idea of legitimization. Alternatively, it is possible that a simple curtain or veil (

sitr) hid the Taifa king, as Miquel Barceló (ibid., pp. 155–56) describes for the ‘Abbasid and Fatimid caliphates, tracing the origin of this tradition to the East. So, could this be the hall where the caliph Abū Ya’qūb Yūsuf received the recognition of the Banū Mardanīš in 1172, and even the congratulatory session for the victory against the Christians of Ávila a year later? As we can interpret from the data offered by Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā, along with those that we have previously had occasion to gather, the Almohad caliph sat for this type of act “on his lofty and noble throne”—adjectives that refer to the majesty granted to the ruler who uses it (

Fierro 2009, pp. 148–49), and to which the term

miḥrāb is associated as a distinguished space or place (

Parada López de Corselas 2013, pp. 113–14), since that “throne” could be as simple as a rug (as Maribel Fierro explains). Hence, the symbolic representation of a

miḥrāb in the courtrooms should not seem odd, nor should the sources that sometimes allude to the throne with this expression.

Continuing with the descriptions made by the chronicler of Beja on that particular issue, the rest of the representatives of the Almohad state apparatus (

sayyids,

fuqahā’,

ṭālibes, etc.) were placed next to the caliph in an orderly manner and, once arranged, they proceeded to their presentation and access was given by categories to all those guests waiting at the doors of the palace for their subsequent recognition or congratulation. Then they kissed “his blessed hand”, thereby emulating the protocol of the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba

27, and whose practice is attributed to the Prophet (

Fierro 2009, pp. 136–37). All of this shows us that, at these moments, the first to occupy the throne room were the caliph himself, his relatives, and those close to the court, while the last to enter were those present at the act in question, before participating in a ceremony in which the Almohad caliph showed himself to his subjects without any visual barrier (ibid., p. 143;

Marín 2005, II. 451–476).

Regarding the entrance of the ruler to the main hall from his private rooms, and taking into account the hypothetical plans and reconstructions designed for the Islamic palace, it is strange that it was made through the spaces located at its ends, passing previously through the portico to occupy his throne. A direct access would allow the monarch or caliph a certain independence, without the need to mix with the rest of the members of the court who would attend the ceremony, and the hall itself could have contained some access route to the northern houses. This is how we can interpret the existing entrance in the southwest corner of the southern bay of the Atienza-Becerril house that can be seen in the plan of Sebastián van der Borcht (see

Figure 5a), which could be a material testimony of the past that has survived to the present day, fossilized and transformed into the door through which we enter today to contemplate the vault of interlaced arches of the eastern hall. Today, this void gives access to the eastern half of what would have been the old north hall of the Islamic palace, and it would be appropriate to wait until a detailed study of it allows us to corroborate its chronology. However, Miguel Ángel Tabales assures us that the origin of this door is from the modern period, and that there must have been an entrance in the eastern hall itself that connected to the adjoining house to the north

28. One way or another, this idea underlies the configuration of the palatine complex.

However, it is also notable that this palace—as we mentioned when talking about the absence of another pool in the south front of the garden—did not have its corresponding southern corridors (

Tabales Rodríguez and Vargas Lorenzo 2014, p. 32). Some specialists have suggested that this circumstance is mainly due to the fact that the construction of this palace coincided with the incorporation of Seville into the Almoravid Empire in 1091 and the consequent exile of the last ‘Abbādī sovereign in Agmāt, therefore remaining unfinished (

Vargas Lorenzo 2019, p. 17;

2020a, pp. 228–29). Even based on the analysis of some of the remains, it has been possible to date the beginning of the works of the entire primitive enclosure to the year 1086 (

Cabañero Subiza 2020, pp. 305–88). However, the documentary and material testimonies to which we have access, along with the various investigations carried out on the Sevillian palace and fortress, oblige us to review the palace of al-Mu’tamid to help us come closer to understanding it.

4. The Palace of Ibn ‘Abbād in the Complex of the Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville): Study and Analysis of Its Chronology and Location

The discovery of the remains of the 11th century palace in the western sector of the Patio de Banderas (Courtyard of Flags) of the fortress of Seville has allowed us to advance our knowledge of the different palatial areas that comprised it, as well as giving us a much closer idea of what could have been the Qaṣr al-Mubārak. In addition, the detailed reading of the data offered by the texts on this matter, along with the different studies carried out by specialists from different disciplines, prompts us to approach this reality in an interdisciplinary way, as is increasingly necessary.

Having reached this point, and considering everything that has been revealed so far, we consider it appropriate to answer some questions related to the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād. As we have had the opportunity to comment on the data collected in the Arabic written documentation, the most common expression with which the palace appears cited in the context of the 11th century is that of

Qaṣr al-Mubārak, generalized from the 12th century by the name of “palace of Ibn ‘Abbād” and associated by historiography with the figure of al-Mu’tamid of Seville. Thus, we have been able to corroborate it explicitly with ‘Abd al-Wāḥid al-Marrākušī who, on the occasion of the assassination of Ibn ‘Ammār, identifies the “Qaṣr al-Mubārak” with the “Palace of al-Mu’tamid”. Even Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā refers in his chronicle to the Sevillian palace as the “palace of Muḥammad Ibn ‘Abbād”

29—the place where Hilāl b. Mardanīš stayed when he went to the Almohad Andalusian capital to recognize the caliph Abū Ya’qūb Yūsuf.

However, we have had more problems regarding its location. Taking into account the information offered by the Arabic sources, as well as the different approaches issued over the years by different authors, everything seems to indicate that it could have been located in the primitive enclosures of the current Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville), being built in a neighborhood outside the walls that research dates to the late Caliphate and Taifa periods (

Tabales Rodríguez 2013, pp. 99–101;

2020a, pp. 58–59;

Tabales Rodríguez and Gurriarán Daza 2021, pp. 2–4;

Tabales Rodríguez and Vargas Lorenzo 2017, pp. 198–203). To this, we must add how the archaeological interventions carried out by

Miguel Ángel Tabales Rodríguez (

2020a, pp. 61–64) in the foundation trenches of its walls—traditionally linked to the 10th century

Dār al-Imāra—have led him to propose a different dating, placing its construction between the mid-11th century and the beginning of the 12th century. With respect to the latter, he proposes two different but close-in-time constructive moments, attributing the works of the foundational palace (Enclosure I) to al-Mu’taḍid, and its extension to the south (Enclosure II) to his son and successor al-Mu’tamid (

Tabales Rodríguez 2013, p. 108;

2020a, pp. 57, 110;

2020c, pp. 425–26;

Tabales Rodríguez and Gurriarán Daza 2021, pp. 12–13;

Tabales Rodríguez and Vargas Lorenzo 2017, pp. 215–18), as already proposed by

Magdalena Valor Piechotta (

2008, p. 22)

30.

This is something that should not seem strange to us since—as Pilar Lirola Delgado determined from the works of Ibn Ḥayyān (

Lirola Delgado 2011, p. 76), followed by other specialists (

Valor Piechota and Lafuente Ibáñez 2018, pp. 180, 198)—we know that al-Mu’taḍid built magnificent palaces; the author went so far as to relate the construction of the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak to the aforementioned monarch, and to which al-Mu’tamid added other dependencies. Even

José Guerrero Lovillo (

1974, p. 97) already posited that this palace may have existed in the time of al-Mu’taḍid. Apart from the chronology derived from the aforementioned interventions, and although the Cordovan chronicler is not very explicit in this regard, the study of the documentary sources leads us to reflect on this approach and endorse this hypothesis, as already proposed a few years ago (

González Cavero 2013, II. 61 and 73–74)—albeit with certain nuances.

We know that Ibn Zaydūn already made reference in his verses to the existence of this palace prior to the date of his death in 1071, linking it to al-Mu’tamid, as we have been able to verify in the Arabic texts. It seems that the aforementioned vizier and poet entered al-Mu’taḍid’s service in 1049–1050, which is when he must have met a young al-Mu’tamid who, two years after Ibn Zaydūn’s arrival at the Sevillian court, was appointed governor of Huelva and Saltés by his father, whereupon he had to leave (

Lirola Delgado 2011, pp. 110–13)

31. It was not until the assassination of his brother and successor Ismā’īl b. ‘Abbād in 1058–1059 by al-Mu’taḍid himself that al-Mu’tamid had to return to Seville to be appointed heir in his place (ibid., p. 255). Therefore, we think that it is between the years 1058–1059 and 1071 that the Cordovan vizier and poet may have written the poem to which we have referred; thus, the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak should have already been built.

We have been able to corroborate this from the study carried out by Auguste Cour, who points out how Ibn Zaydūn—already serving al-Mu’tamid—reminded him through these verses of his duty to maintain and visit his palaces, among which (as mentioned in this composition) was the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak (

Cour 1920, p. 128). Moreover, let us not forget the words of the poet Ibn Ḥamdīs when describing the qualities—probably of al-Mu’tamid—extrapolated to the construction of what we think could be the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād, which lead us to suggest that it was conceived for him from the beginning.

Based on the above, and in agreement with the aforementioned specialists, the construction of the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak had to begin during the reign of al-Mu’taḍid, since the two years between al-Mu’tamid’s accession to power and the death of Ibn Zaydūn are, in our opinion, too short a timespan for the construction of a palace of such magnitude. Let us also remember that al-Mu’tamid conquered Cordoba just after acceding to the throne in 1069—an event that motivated the return of the poet to his hometown, where he spent his last days (

Del Moral Molina 2013, p. 121). To all this, we must add—as we can interpret from Ibn Zaydūn’s verses—that the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak could have been practically completed prior to 1071, as evidenced by the use to which it was already being put by al-Mu’tamid according to the poem describing the author’s visit to

al-Ṯurayya, which would support the hypothesis that the palace was built for this monarch while he was still a prince.

The constructive enterprise of this palace would have continued throughout the years of his reign, extending the primitive enclosure towards the south or adding other dependencies, as has already been pointed out. In fact, it is significant to note the personified dialogue that we can read in the

Risāla (

Epistle) of Abū Ŷa’far b. Aḥmad between the

Qaṣr al-Mukarram and the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak, when the latter states how al-Mu’tamid revived its mention and raised its value:

“(Al-Mubārak speaks) […] When my good star returned and a victorious fate favored my fortune by departing from you to me, and a star rose from you and headed towards me, the lord al-Mu’tamid who revived your old ruins and rejuvenated what was already decrepit as he revived my mention and raised my courage, behold my name was inscribed on the list of the great mansions and recorded in the list of the high palaces, who saw the valleys turn into mountains before I did?”.

Could he have restored that importance not only by reoccupying it, but also by leaving his material imprint on it? As far as its construction is concerned, we have documentary evidence that it was made of stone ashlars. This is what Abū Ŷa’far b. Aḥmad himself states later, when he has the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak say of itself “At every dawn the visitor surrounds me and after walking around, visits every pillar and every stone” (ibid.). Furthermore, we know from Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā that the minaret (

sawma’a) of the Almohad mosque of Seville began to be constructed in the year 1184, using “the stone called “taŷūn al ‘ādī”, taken from the wall of the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād” (

Ibn Ṣāḥib al-Salā 1969, p. 201). For its part, in the translation made by Fátima Roldán Castro from this same fragment, we can read how the master builder Aḥmad b. Baso began “the works and did so (with old ashlars) of stone transported from the wall of the Palace of Ibn ‘Abbād” (

Roldán Castro 2002, p. 20)—material that coincides with that which predominates in Enclosures I and II of the Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville).

We can infer that the palace of al-Mu’tamid was exempt and endowed with a wall of stone ashlars, which were possibly reused (

González Cavero 2013, II. 274). This nature can also be seen on the occasions of Alfonso VI’s siege of the city of Seville in 1082–1083, the establishment of Almohad troops in the capital in the mid-12th century, and the crucifixion of the rebel Ibn Abī Ŷa’far in 1061–1062—all events that we have had occasion to comment on before, and in which reference was made to the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād within the framework of the events that unfolded.

Consequently, and as derived from the research conducted by Miguel Ángel Tabales and Cristina Vargas—who identified the primitive enclosures of the palace as the “core area” of the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak (

Tabales Rodríguez 2013, p. 107;

Tabales Rodríguez and Vargas Lorenzo 2017, p. 216)

32—we believe that the latter was effectively conceived as a construction in and of itself. Even the aforementioned specialists propose that it could have housed in its interior some of the most important palaces that are cited in the documentary sources, all integrated into a single palatine complex. In this sense, Pilar Lirola Delgado already noted that most of these buildings were part of the same complex, even locating the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak next to the

Qaṣr al-Mukarram (

Lirola Delgado 2011, pp. 164–68), as did

Valor Piechota and Lafuente Ibáñez (

2018, p. 198).

However, if the

Qaṣr al-Mubārak is identified with Enclosures I and II of the present-day Reales Alcázares of Seville (Royal Palace and Fortress of Seville), where was the

Dār al-Imāra located? To this day, this question is still a matter of debate, since we have no more information than that offered by al-Bakrī, according to whom it was already built at the time he wrote his work in 1067–1068. Some authors propose, in the absence of future researchers shedding some more light on the matter—and without yet having material data to support it—that it could be found in the place currently occupied by the Archbishop’s Palace (

Vargas Lorenzo 2020b, pp. 24–25, 35;

Tabales Rodríguez 2020a, p. 58). However, it strikes us that a figure such as al-Bakrī—who also served as a court poet during what may have been the last years of al-Mu’tamid’s reign, according to the poems that he wrote in 1085–1086 in the context of the battle of

al-Zallāqa (

García Sanjuán 2002, p. 19;

2008, pp. 43–44)—makes no reference in his geographical work to the palace of Ibn ‘Abbād, yet he mentions the city wall of Seville, the Emiral Mosque with its minaret, and the “ancient palace called “Dār al-Imāra” (

Al-Bakrī 1982, p. 33). Some authors have even identified it with the

Qaṣr al-Mukarram and placed it in the vicinity of the