Reverberations of Persepolis: Persianist Readings of Late Roman Wall Decoration

Abstract

:1. Introduction

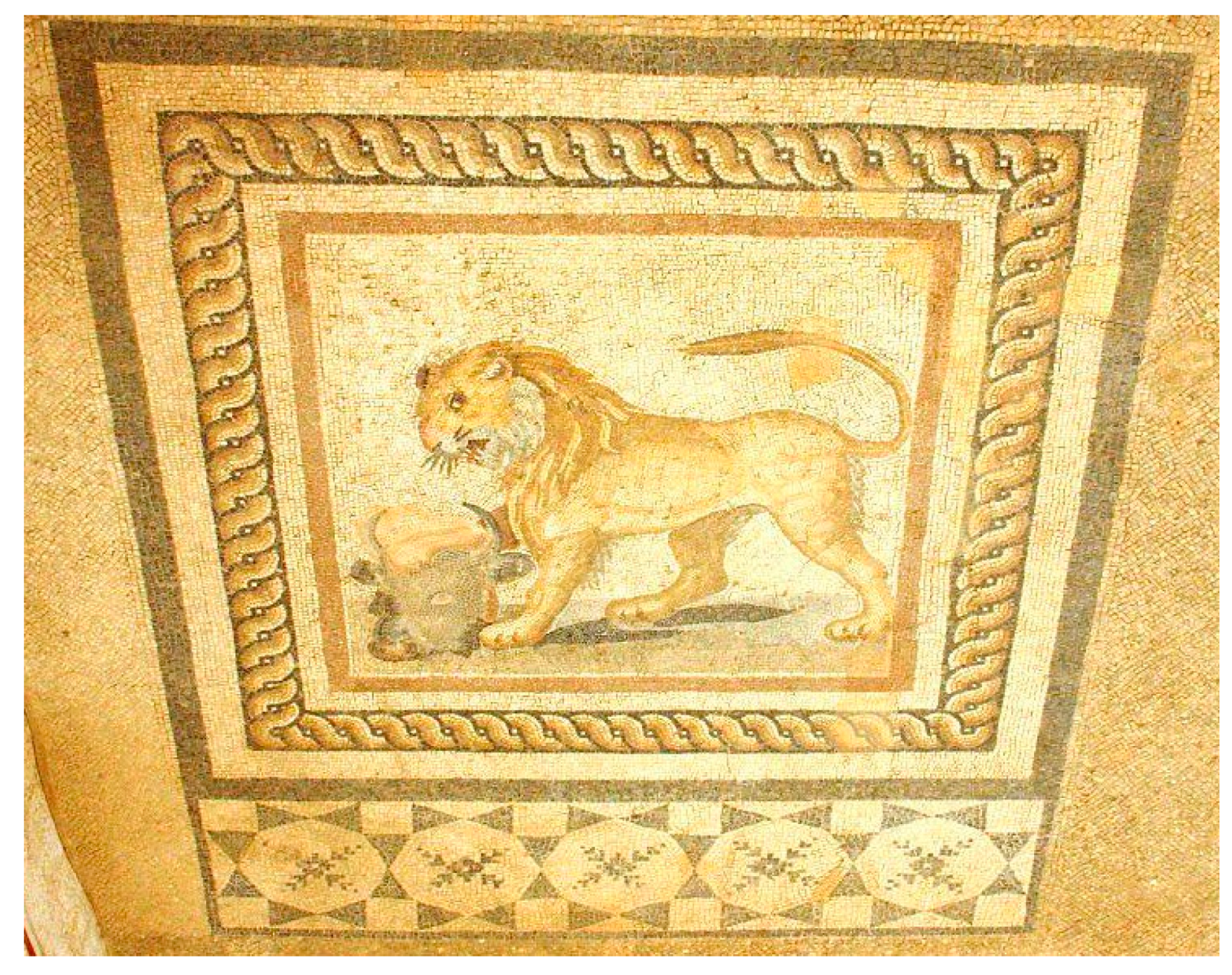

It has on its walls, and in the upper parts, some profane figures of oriental marbles, a lion that tears a deer to pieces, a leopard that kills a cow, and similar savage creatures, and so far as you can glimpse from some of the arches and windows and from many fragments in the wall, this building was all illustrated in oriental marble.1—From Benedetto Mellini’s 17th century Descrittione di Roma.

2. The Panels

3. Roman Readings

4. Turning to Persia

5. The Apadana at Persepolis

6. Looking across Monuments

7. Installing the Wall

8. Lineage and Transmission of the Animal Combat Theme

9. Between Rome and Persia

10. Persianist Re-Readings: The Middle Ground

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Arena, Maria Stella. 2008. L’opus sectile di Porta Marina. Archeologia Viva XXVII: 28–35.

- Arena, Maria Stella, and Anna Maria Carruba. 2005. L’opus Sectile di Porta Marina. Rome: Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici di Ostia.

- Barnes, Timothy D. 2009. The Persian Sack of Antioch in 253. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 169: 294–96.

- Brown, Peter. 2018. ‘Charismatic’ Goods: Commerce, Diplomacy, and Cultural Contacts Along the Silk Road in Late Antiquity. In Empires and Exchanges In Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, Ca. 250–750. Edited by Nicola Di Cosmo and Michael Maas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 96–107.

- Callieri, Pierfrancesco. 2017. Cultural Contacts between Rome and Persia at the Time of Ardashir I (c. AD 224–240). In Sasanian Persia: between Rome and the Steppes of Eurasia. Edited by Eberhard W. Sauer. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Calmeyer, Peter. 1980. Textual Sources for the Interpretation of Achaemenian Palace Decorations. Iran 18: 55–63.

- Carucci, Margherita. 2008. The Sette Sale Domus. A Proposal of Reading. In Import and Imitation in Archeology. Edited by Peter F. Biehl and Y. Ya. Rassamakin. Langenweißbach: Beier & Beran.

- De Blois, Lukas. 2016. Rome and Persia in the Middle of the Third Century A.D. In Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers. Edited by Daniëlle Slootjes and Michael Peachin. 33. Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, c. 200 BC-AD 476) 21. Leiden: Brill, pp. 230–66.

- De Rossi, Giovanni Battista. 1871. La Basilica Profana Di Giunio Basso Sull’Esquilino Dedicata Poi a s. Andrea Ed Appellate Catabarbara Patricia. Bullettino Di Archeologia Cristiana 2: 5–29, 41–64.

- Ellis, Simon P. 1991. Power, Architecture, and Decor: How the Late Roman Aristocrat Appeared to His Guests. In Roman Art in the Private Sphere: New Perspectives on the Architecture and Decor of the Domus, Villa, and Insula. Edited by Elaine K. Gazda. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Ensoli, Serena, and Eugenio La Rocca, eds. 2000. Aurea Roma: Dalla Città Pagana alla Città Cristiana. Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Garrison, Mark B. 2000. Achaemenid Iconography as Evidenced by Glyptic Art: Subject Matter, Social Function, Audience and Diffusion. In Images as Media: Sources for the Cultural History of the Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean (1st Millenium BCE). Edited by Christoph Uehlinger. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 175. Fribourg: University Press, pp. 115–63.

- Gionta, Daniela. 2017. Una piccola silloge epigrafica in un manoscritto della Roma instaurata. In Roma, Napoli e Altri Viaggi. Per Mauro de Nichilo. Bari: Cacucci Editore, pp. 197–206.

- Grabar, André. 1971. Le rayonnement de l’art sassanide dans le monde chrétien. In Atti del Convegno Internazionale sul Tema: La Persia nel Medioevo (Roma, 31 Marzo-5 Aprile 1970). Rome: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, pp. 679–707.

- Guidobaldi, Federico. 1989. L’intarsio marmoreo nella decorazione parietale e pavimentale di età romana. In Il Marmo Nella Civiltà Romana: La Produzione e il Commercio. Edited by Enrico Dolci. Carrara: Internazionale Marmi e Macchine, pp. 56–67.

- Guidobaldi, Federico. 1992. L’opus sectile parietal a Rome. Les Dossiers d’Archeologie 173: 72–77.

- Hansen, Sanne Lind. 1997. The Embellishment of Late-Antique Domus in Ostia and Rome. In Patron and Pavements in Late Antiquity. Edited by Signe Isager and Birte Poulsen. Denmark: Odense University Press.

- Harper, Prudence O. 1988. Sasanian Silver: Internal Developments and Foreign Influences. In Argenterie Romaine et Byzantine. Actes de La Table Ronde. Paris 11–13 Octobre 1983. Paris: De Boccard.

- Hülsen, Christian. 1899. Il fondatore della Basilica di Sant’Andrea sull’Esquilino. Nuovo Bullettino di Archeologia Cristiana 5: 171–76.

- Hülsen, Christian. 1927. Die Basilica des Iunius Bassus und die Kirche S. Andrea Cata Barbara auf dem Esquilin. In Festschrift für Julius Schlosser Zum 60. Geburtstage. Zurich: Amalthea Verlag, pp. 53–67.

- Ivanova, Mirela, and Hugh Jeffery, eds. 2020. Transmitting and Circulating the Late Antique and Byzantine Worlds. The Medieval Mediterranean. Leiden: Brill, vol. 118.

- Lugli, Giuseppe. 1932. La Basilica di Giunio Basso sull’Esquilino. Rivista di Archeologia Cristiana 9: 221–55.

- Makhlaiuk, Aleksandr V. 2015. Memory and Images of Achaemenid Persia in the Roman Empire. In Political Memory in and after the Persian Empire. Edited by Jason M. Silverman and Caroline Waerzeggers. Ancient Near East Monographs 13. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature Press, pp. 299–324.

- Mousavi, Ali. 2012. Persepolis: Discovery and Afterlife of a World Wonder. Boston: De Gruyter.

- Nabel, Jake. 2018. Alexander between Rome and Persia: Politics, Ideology, and History. In Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Alexander the Great. Edited by Kenneth Royce Moore. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, pp. 197–232. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004359932_009.

- Pensabene, Patrizio. 2007. Ostiensum Marmorum Decus et Décor. Studi Architectonici, Decorativi e Archeometrici. Studi Miscellanei 33. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.

- Pfommer, Michael. 1993. Metalwork from the Hellenized East. Catalogue of the Collections. Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Porada, Edith, and Ann C. Gunter. 1990. Animal Subjects of the Ancient Near Eastern Artist. In Investigating Artistic Environments in the Ancient Near East. Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, pp. 71–79.

- Rea, Rossella. 2001. Gli animali per la venatio: cattura, trasporto, custodia. In Sangue e Arena. Edited by Adriano La Regina. Rome: Electa, pp. 245–76.

- Russo, Eugenio. 1984. Fasi e nodi della scultura a Roma nel VI e VII secolo. Mélanges de l’Ecole Française de Rome. Moyen-Age, Temps Modernes 96: 7–48. https://doi.org/10.3406/mefr.1984.2744.

- Russo, Eugenio. 2004. La scultura di S. Polieucto e la presenza della Persia nella cultura artistica di Constantinopoli nel VI secolo. In La Persia e Bisanzio, Atti dei Convegni Lincei 201 (Roma, 14–18 Ottobre 2002). Rome: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, pp. 737–826.

- Salzman, Michele Renee, Marianne Sághy, and Rita Lizzi Testa. 2016. Pagans and Christians in Late Antique Rome: Conflict, Competition, and Coexistence in the Fourth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sapelli, Marina. 2000. La Basilica di Giunio Basso. In Aurea Roma: Dalla Città Pagana alla Città Cristiana. Edited by Serena Ensoli and Eugenio La Rocca. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, pp. 137–39.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger, and David Stronach. 1987. Apadāna. Encyclopaedia Iranica II/2:145–48. Available online: https://iranicaonline.org/articles/apadana (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Sergueenkova, Valeria, and Felipe Rojas. 2017. Persia on Their Minds: Achaemenid Memory Horizons in Roman Anatolia. In Persianism in Antiquity. Edited by Rolf Strootman and Miguel John Versluys. Oriens et Occidens. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, vol. 25, pp. 269–88.

- Slootjes, Daniëlle, and Michael Peachin, eds. 2016. Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers. Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, c. 200 BC–AD 476) 21. Leiden: Brill.

- Strootman, Rolf, and Miguel John Versluys, eds. 2017. Persianism in Antiquity. Oriens et Occidens. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, vol. 25.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef, and Philip Huyse, eds. 2006. Ērān ud Anērān. Studien zu den Beziehungen Zwischen dem Sassanidenreich und der Mittelmeerwelt. Beiträge des Internationalen Colloquiums in Eutin, 8–9 Juni 2000. Oriens et Occidens. Studien Zu Antiken Kulturkontakten Und Ihrem Nachleben. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, vol. 13.

| 1 | Mellini (Cod. Vat. Lat. 11905, f. 215), librarian to Queen Christina of Sweden, may have seen the Basilica of Junius Bassus himself, but it is likely he relied on earlier sources to complete the Descrittione. Translation mine. |

| 2 | (Canepa 2009, p. 1) opens with an excerpt from a letter to the Roman emperor Maurice from Kosrow II. The Persian king writes that the world is lit by “two eyes, namely by the most powerful kingdom of the Romans and by the most prudent scepter of the Persian state”. |

| 3 | (Martin 2017); see for a discussion of the middle ground esp. pp. 153–56. |

| 4 | (Strootman and Versluys 2017, p. 9). The term is used in several essays in the volume. See p. 10 footnote 8 for Versluys’ earlier treatment of the concept. (Root 1991, p. 13) called this idea Persianizing, to “refer to art that reveals the suffusion of ‘Greek art’ with powerful evocations of aristocratic Persian values and the iconography of royal ideology”. |

| 5 | (Hagan 2018b, pp. 96–97) for discussion of Renaissance accounts of the decoration. |

| 6 | (Hagan 2018a) gives hypothetical reconstructions based on post-antique records and extant material. |

| 7 | (Bianchi et al. 2000, p. 352) notes serpentine strips that match the tiger striping seen on Bassus’ tigers, as well as the illustrated claws. For further on decoration see (Bianchi et al. 2002) and (Volpe 2000), with bibliography on excavation campaigns. (Guidobaldi 1986, pp. 190–92) refers to a fourth site on the Esquiline Hill, beneath Santa Lucia in Selci, which should also be considered, as Renaissance visitors note imagery of animal contests there; see (Carucci 2005, p. 908). |

| 8 | (Kiilerich 2014) and (Kiilerich 2016) are also useful treatments of the Ostian hall and the medium more broadly. |

| 9 | As in (Futrell 1997). Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power. |

| 10 | As for example in (Brown 1992) and (Barnes 2011). |

| 11 | See (Olovsdotter 2005, esp. p. 51) (venationes on the diptych of Anastasius, 517) and pp. 123–27, “Motifs and Scenes related to the consular Munera”. Unlike the opus sectile and mosaic examples, these diptychs feature venationes with human participants. |

| 12 | (Becatti 1967). The appendix treats the Bassus hall. |

| 13 | (Becatti 1967, p. 210). On Kenchreai, see (Ibrahim et al. 1976). |

| 14 | Besides the Kenchreai hall and the building beneath Santa Lucia in Selci mentioned above, (Becatti 1967, p. 208) names the earlier subterranean basilica at Porta Maggiore. Becatti does not stand alone in arguing for neo-Platonic interpretations of domestic decoration. (Balty 2014, pp. 52–53) arrives at the same conclusion in her viewing of the house of Achilles and the House of Cassiopeia in Palmyra, citing the activities of Plotinus and Longinus in the region in the second half of the third century CE. |

| 15 | See e.g., (Becatti 1967, pp. 144–5). Edificio con Opus Sectile Fuori Porta Marina. |

| 16 | e.g., (Guidobaldi 1986). L’edilizia abitativa unifamiliare nella Roma tardo-antica. |

| 17 | (Hagan 2016) and (Hagan 2018a, p. 137 ff.) conclude the building is a work of civic benefaction on the basis of its dedication inscription, CIL 1737. |

| 18 | (Jennison ([1937] 2005) is still an important reference work, though more recent scholarship has incorporated additional materials and methodologies. See e.g., (Bomgardner 1992) and (MacKinnon 2006). |

| 19 | (Pliny NH VIII, 25 (66)): tigrim Hyrcani et Indi ferunt. See (Toynbee 1973, p. 70, note 64) for further attestations. |

| 20 | (Futrell 1997, p. 51); (Kyle 1998, p. 309). See also p. 32 and (Llewellyn-Jones 2017, p. 307) for earlier instantiations of this symbolism. |

| 21 | See on this topic foundationally (Schneider 1986). For the resonances of this practice and additional examples, see (Burrell 2012). |

| 22 | (Epigr. 8.55.6): marmora picturata lucentia vena. (Eutrop. 2.272-3): pretiosaque picto/marmore purpureis caedit quod Synnada venis. See (Carey 2003, pp. 91–92), on Pliny’s discussion of foreign marbles: “Pliny’s history of marble is both a history of the Roman conquest of the world and a history of the world in Rome”. Also useful for stones’ origins are (Lazzarini 2002) and (Pensabene 1998). |

| 23 | As in Textiles and Elite Tastes between the Mediterranean, Iran and Asia at the End of Antiquity (Canepa 2014). |

| 24 | For a succinct catalogue summary of this and several other Achaemenid royal monuments, including tombs, see (Root 2001). The Apadana is discussed at (pp. 86–95) with foundational bibliography from the original excavation, including (Schmidt 1953). |

| 25 | Each instance noted in (Almagor 2021, p. 20 note. 135), with concordances to the plates in (Schmidt 1953). |

| 26 | (Root 2001, p. 202). See also (Root 2003, pp. 21–22), which suggests that further valences of cyclical time and seasonal abundance are imparted by the rosettes that outline sections of the Apadana parapet frieze. Each rosette has 12 petals, matching the 12 months of the year. |

| 27 | (Ulanowski 2015, pp. 263, 265; Watanabe 2002, p. 54). On the lion hunt in Near Eastern art, see (Almagor 2021, p. 15). |

| 28 | (Root 2001, p. 200). The Achaemenids used it too: (Markoe 1989, p. 103). |

| 29 | (Root 2001, p. 202) notes some exceptions on seals. |

| 30 | Among the extant panels, the exception to this composition is the Ostian tigress, who lifts her chest and exposes it to the viewer, front legs extended as if holding its prey at a slight distance. |

| 31 | The onager, or wild ass, is easy to mistake for a horse, but can be identified by black stripes. See (Parrish 1987, p. 114 and note 4). |

| 32 | The left-facing tiger at the Basilica of Junius Bassus (MC1226) has only a single exaggerated nodule, rather than three, and incised pupils instead of inlaid ones, making the eye look more like a skillet with an egg in it. This panel may have undergone restoration when it was removed from the wall of the basilica and turned into a tabletop at Sant’Antonio, some time during the second half of the 17th century according to the report of (Ciampini 1690, p. 56). See (Hagan 2018a, pp. 95–96), and for a discussion of conservation history see (Cima and Rubolino 2000, p. 81). It is unclear whether the tigers’ eyes were part of the modern intervention. This tigress may have had her front right paw wrapped around the neck of the bull, so that it was visible like in the other panels. Given the clear alteration of the head and neck of the bull, it is likely that this paw was edited out during the restoration. |

| 33 | Paint could have been used to enhance texture or emphasize any other detail, but only microscopic indications of pigment remain. |

| 34 | See (Hagan 2018a, p. 101 ff) for an assessment of the post-antique sources. |

| 35 | On which, see (Balty 1993); (Ghirshman 1956). |

| 36 | The plan is illustrated in (Ghirshman 1956, Plan IV). |

| 37 | This fungibility or perhaps customizability is discussed with respect to textile design in (Elsner 2020). |

| 38 | For example, see (Becatti 1967, pp. 145–49); (Parrish 1987, p. 114) with bibliography at note 8; (Kraeling 1956, p. 245): “the animals … are, of course, a familiar element of the vocabulary of Oriental art since time immemorial”. |

| 39 | (Watanabe 2002) offers one good survey. (Ulanowski 2015) also provides a rich collection. |

| 40 | See for example (Ulanowski 2015, pp. 260, 264); (Markoe 1989, p. 93 ff). Markoe argues this comes out of the Greek epic poetry tradition. |

| 41 | See (Gates 2002, Figure 1) for image. |

| 42 | (Gates 2002, p. 108). See image at Figure 1. |

| 43 | I thank the anonymous reviewers of my manuscript for exhorting me to include glyptics among the categories of evidence included, and for pointing me to both the seal and the coin mentioned below. |

| 44 | Other glyptic arts (metalwork, gems, coins) would also account for transmission, both across media and across cultures. (Rostovtzeff 1935, pp. 267–69) for example collects glyptic instances of hunting imagery reproduced in painting at Dura. I am not able to offer a complete survey of glyptic examples, but (Garrison 2014) and (Gates 2002) give astute analyses of the role of seals in art historical study, and are accessible to non-specialists. |

| 45 | A variant, this time with a stag as victim, is seen on another of Mazaeus’ coins: British Museum 18960601.103. |

| 46 | Smithsonian cat. A158351. See (Parrish 1987, p. 117) and http://n2t.net/ark:/65665/3b7b423b4-fd4c-496b-96cf-25f1beb8a1e4 (accessed on 19 March 2023). |

| 47 | (Toynbee 1973, p. 16); see p. 68 for discussion. |

| 48 | (Kraeling 1956, pp. 240–46). In the Dura dado, animals sometimes face each other, with a panel in between, but the author notes when they do the artists place the pairing in a corner so as not to compete with the Torah shrine as a focal point. For images see Plates XVIII-XXIV, XXXVII-XXXIX figs. 62–69. Color images of the restoration can be seen at https://evergreene.com/projects/dura-europos-synagogue/ (accessed on 19 March 2023). |

| 49 | Discussed at (Becatti 1967, p. 145), with reference to (Kraeling 1956, p. 245 ff). |

| 50 | (Root 1985). She offers other examples, from the Persian rhyton to architectural forms influenced by the Tent of Xerxes, at p. 116 (with bibliography). |

| 51 | (Root 1985, p. 119) gives as an example of multi-site duplication the Bisutun relief of Darius, which was recreated for the city of Babylon. |

| 52 | On the import of Sasanian design for understanding Diocletian’s palace: (Hunnell Chen 2016). An oblique comment attributed to Shapur by Lactantius suggests the Persian emperor, too, was familiar with Roman interior decoration from firsthand experience: (Cutler 2009b, pp. 15–16). |

| 53 | On diplomacy and diplomatic gifts: (Canepa 2009, pp. 28–30) and (Cutler 2009b, pp. 12–14). |

| 54 | Discussed in Ammianus Marcellinus’ Image of Sasanian Society (Drijvers 2006, p. 48). |

| 55 | See (Canepa 2009, pp. 28–29) and notes 123 (Sasanians loot Roman Antioch) and 132 (Romans loot Mesopotamia and Persian Armenia). |

| 56 | (Balty 2006, p. 29); on deportation and forced resettlement see (Dignas and Winter 2007, pp. 254–63). |

| 57 | |

| 58 | |

| 59 | This is suggested by (Schneider 2006, p. 243). Naqs-e-Rostam VI is illustrated in (Canepa 2009, p. 64 fig. 4). For a more thorough treatment of these reliefs and Sasanian understanding of the kneeling supplicant via Sasanian text, see (Canepa 2009, pp. 55–68). |

| 60 | This relief is known as Bishapur II. See (Canepa 2009, pp. 58–59, pp. 71–75, and p. 73 fig. 9). |

| 61 | (Hunnell Chen 2016, pp. 237–40). The cameo is illustrated in (Canepa 2009, p. 69 fig. 7). On the Arch of Galerius, see (Canepa 2009, pp. 85–98); p. 94, fig. 16 illustrates the equestrian scene on the arch. |

| 62 | In the case of the Bassus hall, it has been elsewhere suggested that its varied decoration—to the extent it survives—comprises a cosmopolitan multilingual stylistic idiom, or what Canepa (2009, p. 77) calls “a cross-continental aristocratic common culture”. In this passage Canepa is speaking about Shapur, but I think this rightfully applies to the aesthetic aims of the Roman elite. Bassus doubles down on this claim by using Aegyptiaca in some panels, Persianist themes in others, and Greco-Roman myth expressed in the mode of high naturalism. |

| 63 | He calls these “archetypes of artistic influence”. |

| 64 | (Gagetti 2012, p. 100). (Canepa 2009, p. 57) expresses the same idea. |

References

Primary Sources

(Ammianus 1963) Ammianus, Marcellinus. 1963. Res Gestae. Translated by John Carew Rolfe. Books 14–19. Loeb Classical Library 300. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, vol. 1.(Ciampini 1690) Ciampini, Giovanni Giustino. 1690. Vetera Monimenta. Rome: Joannis Jacobi Komarek Bohemi. Available online: http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/ciampini1690bd1 (accessed on 11 April 2023).(Cod. Vat. Lat. 11905) Mellini, Benedetto. ca. 17th century. Cod. Vat. Lat. 11905. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.Secondary Sources

- Almagor, Eran. 2021. The Horse and the Lion in Achaemenid Persia: Representations of a Duality. Arts 10: 41. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/10/3/41/htm (accessed on 19 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Balty, Janine. 1993. Les mosaïques. In Splendeur des Sassanides: L’empire Perse Entre Rome et la Chine (224–642). Edited by Bruno Overlaet and Micheline Ruyssinck. Brussels: Musées Royaux D’art e D’histoire. [Google Scholar]

- Balty, Janine. 2006. Mosaïques Romaines, Mosaïques Sassanides: Jeux d’influences Réciproques. In Eran ud Aneran. Studien zu den Beziehungen Zwischen dem Sasanidenreich und der Mittelmeerwelt, Beiträge des Internationalen Colloquiums in Eutin, 8–9 Juni 2000. Edited by Philip Huyse and Josef Wiesehöfer. Oriens et Occidens. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, vol. 13, pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Balty, Janine. 2014. Les Mosaïques des Maisons de Palmyre. Inventaire Des Mosaïques Antiques de Syrie 2. Beirut: Institut Français du Proche-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, Aneilya. 2011. The Fusion of Spectacles and Domestic Space in Late-Antique Roman Architecture. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 1: 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, Fabio. 2011. Painting in Stone: The Symbolism of Colored Marbles in the Visual Arts and Literature from Antiquity Until the Enlightenment. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Becatti, Giovanni. 1967. Edificio con Opus Sectile Fuori Porta Marina. Scavi di Ostia. Rome: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Belis, Alexis. 2016. Roman Mosaics in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. Available online: http://www.getty.edu/publications/romanmosaics/ (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Bianchi, Fulvia, Matthias Bruno, Andrea Coletta, and Marilda De Nuccio. 2000. Domus delle Sette Sale. L’opus sectile parietale dell’aula basilicale. Studi preliminari. In AISCOM Atti del VI Colloquio dell’Associazione Italiana per lo Studio e la Conservazione del Mosaico (Venezia 1999). Edited by Federico Guidobaldi and A. Paribeni. Ravenna: Edizioni del Girasole, pp. 351–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Fulvia, Matthias Bruno, and Marilda De Nuccio. 2002. La domus sopra le Sette Sale: La decorazione pavimentale e parietale dell’aula absidata. In I Marmi Colorati della Roma Imperiale. Venice: Marsilio, pp. 161–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bomgardner, David L. 1992. The Trade in Wild Beasts for Roman Spectacles: A Green Perspective. Anthropozoologica 16: 161–66. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Shelby. 1992. Death as Decoration: Scenes from the Arena on Roman Domestic Mosaics. In Pornography and Representation in Greece and Rome. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 180–211. [Google Scholar]

- Burrell, Barbara. 2012. Phrygian for Phrygians: Semiotics of ‘Exotic’ Local Marble. In Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone. Proceedings of the IX ASMOSIA Conference (Tarragona 2009). Edited by Anna Gutiérrez Garcia-M., Pilar Lapuente Mercadal and Isabel Rodà de Llanza. Tarragona: Institut Català d’Arqueologia Clàssica, pp. 780–86. [Google Scholar]

- Canepa, Matthew. 2009. The Two Eyes of the Earth: Art and Ritual of Kingship Between Rome and Sasanian Iran. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Canepa, Matthew. 2010a. Technologies of Memory in Early Sasanian Iran: Achaemenid Sites and Sasanian Identity. American Journal of Archaeology 114: 563–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canepa, Matthew. 2010b. Theorizing Cross-Cultural Interaction among Ancient and Early Medieval Visual Cultures. Ars Orientalis 38: 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Canepa, Matthew P. 2014. Textiles and Elite Tastes between the Mediterranean, Iran and Asia at the End of Antiquity. In Global Textile Encounters. Edited by Marie-Louise Nosch, Zhao Feng and Lotika Varadarajan. Ancient Textiles Series 20; Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, Sorcha. 2003. Pliny’s Catalogue of Culture: Art and Empire in the Natural History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carucci, Margherita. 2005. Domus on the Late Antique Esquiline: Architectural Developments and Social Changes. BAR International Series 1452: 903–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cima, Maddalena, and Maria Pia Rubolino. 2000. Giuinius Basso: La ‘basilica’ scomparsa. Il restauro delle tarsie dei Musei Capitolini. Bollettino dei Museo Comunali di Roma 14: 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, Anthony. 2009a. Image Making in Byzantium, Sasanian Persia, and the Early Muslim World: Images and Cultural Relations. Variorum Collected Studies. Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, Anthony. 2009b. Silver across the Euphrates: Forms of Exchange Between Sasanian Persia and the Late Roman Empire. In Image Making in Byzantium, Sasanian Persia, and the Early Muslim World: Images and Cultural Relations. Variorum Collected Studies. Burlington: Ashgate, pp. 9–37. [Google Scholar]

- Daryaee, Touraj. 2006. The Construction of the Past in Late Antique Persia. Historia: Zeitschrift für alte Geschichte 55: 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloria, Philip. 2006. What Is the Middle Ground, Anyway? The William and Mary Quarterly 63: 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignas, Beate, and Engelbert Winter. 2007. Rome and Persia in Late Antiquity: Neighbours and Rivals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drijvers, Jan Willem. 2006. Ammianus Marcellinus’ Image of Sasanian Society. In Eran du Aneran. Studien zu den Beziehungen Zwischen dem Sasanidenreich und der Mittelmeerwelt. Beiträge des Internationalen Colloquiums in Eutin, 8–9 Juni 2000. Edited by Josef Wiesehöfer and Philip Huyse. Oriens et Occidens. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, vol. 13, pp. 45–69. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, Jaś. 2020. Mutable, Flexible, Fluid: Papyrus Drawings for Textiles and Replication in Roman Art. The Art Bulletin 102: 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinghausen, Richard. 1972. From Byzantium to Sasanian Iran and the Islamic World. The L. A. Mayer Memorial Studies in Islamic Art and Archaeology. Leiden: E. J. Brill, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Feltham, Heleanor. 2010. Lions, Silks and Silver: The Influence of Sasanian Persia. Sino-Platonic Papers 206: 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Futrell, Alison. 1997. Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gagetti, Elisabetta. 2012. Textiles as Iconographic Media between Centres and Peripheries over Time. The Case of the Early Mediaeval Glass Cameos of the ‘Atelier of the Oriental Fabrics’ on the Cross of Desiderius in Brescia. Anodos Studies of the Ancient World 12: 89–217. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, Mark B. 2014. The Impressed Image: Glyptic Studies as Art and Social History. In Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Edited by Brian A. Brown and Marian H. Feldman. Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 481–513. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, Jennifer E. 2002. The Ethnicity Name Game: What Lies Behind ‘Graeco-Persian’? In Ars Orientalis. Medes and Persians: Reflections on Elusive Empires. Washington, DC: The Smithsonian Institution, vol. 32, pp. 105–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gaukler, Paul. 1896. La Domaine Des Laberii à Uthina. Monuments et Mémoires de la Fondation Eugène Piot 3: 177–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghirshman, Roman. 1956. Fouilles de Châpour. Bîchâpour. Musée du Louvre. Département des Antiquités Orientales 6–7. Paris: Geuthner, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Guidobaldi, Federico. 1986. L’edilizia abitativa unifamiliare nella Roma tardo-antica. Società Romana e Impero Tardoantico 2: 165–237. [Google Scholar]

- Guidobaldi, Federico. 2000. La decorazione in opus sectile dell’aula. In Aurea Roma: Dalla Città Pagana alla Città Cristiana. Edited by Serena Ensoli and Eugenio La Rocca. Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider, pp. 251–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, Stephanie A. 2016. Bread and Circuses and Basilicas? Reassessing the Basilica of Junius Bassus. San Francisco: University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, Stephanie A. 2018a. Collaborative Reconstruction: Visualizing the Late Roman Basilica of Junius Bassus. Paper presented at the College Art Association Conference, Los Angeles, CA, USA, February 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, Stephanie A. 2018b. Marble and Munificence: Reassessing the Basilica of Junius Bassus at Rome. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI10827364 (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Hunnell Chen, Anne. 2016. Rival Powers, Rival Images: Diocletian’s Palace at Split in Light of Sasanian Palace Design. In Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers. Edited by Daniëlle Slootjes and Michael Peachin. Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, c. 200 BC–AD 476). Leiden: Brill, vol. 21, pp. 213–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Leila, Robert Scranton, and Robert H. Brill. 1976. The Panels of Opus Sectile in Glass. Kenchreai, Eastern Port of Corinth: Results of Investigations by the University of Chicago and Indiana University for the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Leiden: E. J. Brill, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jennison, George. 2005. Animals for Show and Pleasure in Ancient Rome, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. First published 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Kiilerich, Bente. 2012. The Aesthetic Viewing of Marble in Byzantium: From Global Impression to Focal Attention. Arte Medievale Anno II: 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kiilerich, Bente. 2014. The Opus Sectile from Porta Marina at Ostia and the Aesthetics of Interior Decoration. In Production and Prosperity in the Theodosian Age. Edited by Ine Jacobs. Interdisciplinary Studies in Ancient Culture and Religion 14. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 169–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kiilerich, Bente. 2016. Subtlety and Simulation in Late Antique Opus Sectile. In Il Colore nel Medioevo: Arte Simbolo Tecnica. Tra Materiali Costitutivi e Colori Aggiunti Mosaici, Intarsi e Plastica Lapidea. Edited by Paola Antonella Andreuccetti and Deborah Bindani. Collana di Studi sul Colore 2. Lucca: Istituto Storico Lucchese, pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kraeling, Carl H. 1956. The Synagogue. Vol. VIII part 1. The Excavations at Dura-Europos. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, Donald G. 1994. Animal Spectacles in Ancient Rome. Meat and Meaning. Nikephoros 7: 181–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, Donald G. 1998. Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, Donald G., ed. 2014. Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World, 2nd ed. Oxford: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarini, Lorenzo. 2002. La determinazione della provenienza delle pietre decorative usate dai Romani. In I Marmi Colorati della Roma Imperiale. Edited by Marilda De Nuccio and Lucrezia Ungaro. Rome: Marsilio. [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd. 2017. Keeping and Displaying Royal Tribute Animals in Ancient Persia and the near East. In Interactions between Animals and Humans in Graeco-Roman Antiquity. Edited by Edmund Thomas and Thorsten Fögen. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 305–38. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, Michael. 2006. Supplying Exotic Animals for the Roman Amphitheatre Games: New Reconstructions Combining Archaeological, Ancient Textual, Historical and Ethnographic Data. Mouseion 6: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, Henry. 2000. Profane Icons: The Significance of Animal Violence in Byzantine Art. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 38: 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markoe, Glenn E. 1989. The ‘Lion Attack’ in Archaic Greek Art: Heroic Triumph. Classical Antiquity 8: 86–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S. Rebecca. 2017. The Art of Contact: Comparative Approaches to Greek and Phoenician Art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newby, Zahra. 2012. The Aesthetics of Violence: Myth and Danger in Roman Domestic Landscapes. Classical Antiquity 31: 349–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olovsdotter, Cecilia. 2005. The Consular Image: An Iconological Study of the Consular Diptychs. BAR International Series 1376; Oxford: British Archaeological Reports. [Google Scholar]

- Parrish, David. 1987. A Mosaic of a Lion Attacking an Onager. Karthago 21: 113–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pensabene, Patrizio, ed. 1998. Marmi Antichi II: Cave e Tecnica Di Lavorazione, Provenienze e Distribuzione. Studi Miscellanei 31. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Root, Margaret Cool. 1979. The King and Kingship in Achaemenid Art: Essays on the Creation of an Iconography of Empire. Acta Iranica 19. Leiden: Brill, vol. IX. [Google Scholar]

- Root, Margaret Cool. 1985. The Parthenon Frieze and the Apadana Reliefs at Persepolis: Reassessing a Programmatic Relationship. American Journal of Archaeology 89: 103–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, Margaret Cool. 1991. From the Heart: Powerful Persianisms in the Art of the Western Empire. In Asia Minor and Egypt: Old Cultures in a New Empire. Edited by Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Amelie Kuhrt. Achaemenid History. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, vol. 6, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Root, Margaret Cool. 1994. Lifting the Veil: Artistic Transmission beyond the Boundaries of Historical Periodisation. In Continuity and Change. Edited by Amelie Kuhrt, Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Margaret Cool Root. Achaemenid History. 8. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, pp. 9–37. [Google Scholar]

- Root, Margaret Cool. 2001. Animals in the Art of Ancient Iran. In A History of the Animal World in the Ancient near East. Edited by Billie Jean Collins. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden: Brill, vol. 64, pp. 169–209. [Google Scholar]

- Root, Margaret Cool. 2003. The Lioness of Elam. Politics and Dynastic Fecundity at Persepolis. In A Persian Perspective. Essays in Memory of Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg. Edited by Amélie Kuhrt and Wouter Henkelman. Achaemenid History, XIII. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rostovtzeff, Michael. 1935. Dura and the Problem of Parthian Art. Yale Classical Studies 5: 157–304. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Erich F. 1953. Persepolis I: Structures, Reliefs, Inscriptions. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 68, Available online: https://isac.uchicago.edu/research/publications/oip/oip-68-persepolis-i-structures-reliefs-inscriptions (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Schneider, Rolf Michael. 1986. Bunte Barbaren: Orientalenstatuen aus Farbigem Marmor in der Römischen Repräsentationskunst. Worms: Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Rolf Michael. 1998. Die Faszination des Feindes Bilder der Parther und des Orients in Rom. In Das Partherreich und Seine Zeugnisse. The Arsacid Empire: Sources and Documentation. Beiträge des Internationalen Colloquiums, Eutin (27 –30 Juni 1996). Edited by Josef Wiesehöfer. Historia Einzelschriften 122. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, pp. 19, 95–127. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Rolf Michael. 2001. Coloured Marble: The Splendour and Power of Imperial Rome. Apollo 154: 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Rolf Michael. 2006. Orientalism in Late Antiquity: The Oriental in Imperial and Christian Imagery. In Ērān Ud Anērān. Studien Zu Den Beziehungen Zwischen Dem Sassanidenreich und Der Mittelmeerwelt. Beiträge Des Internationalen Colloquiums in Eutin, 8–9 June 2000. Edited by Josef Wiesehöfer and Philip Huyse. Oriens et Occidens. Studien Zu Antiken Kulturkontakten Und Ihrem Nachleben. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, vol. 13, pp. 241–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, Michael. 2017. The Eternal Persian: Persianism in Ammianus Marcellinus. In Persianism in Antiquity. Edited by Rolf Strootman and Miguel John Versluys. Oriens et Occidens. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, vol. 25, pp. 346–54. [Google Scholar]

- Strootman, Rolf, and Miguel John Versluys. 2017. From Culture to Concept: The Reception and Appropriation of Persia in Antiquity. In Persianism in Antiquity. Edited by Rolf Strootman and Miguel John Versluys. Oriens et Occidens. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, vol. 25, pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Toynbee, Jocelyn M. C. 1973. Animals in Roman Life and Art Aspects of Greek and Roman Life. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Ulanowski, Krzysztof. 2015. The Metaphor of the Lion in Mesopotamian and Greek Civilization. In Mesopotamia in the Ancient World Impact, Continuities, Parallels Proceedings of the Seventh Symposium of the Melammu Project Held in Obergurgl, Austria, November 4–8, 2013. Edited by Robert Rollinger and Erik van Dongen. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, pp. 255–84. [Google Scholar]

- Volpe, Rita. 2000. La domus delle Sette Sale. In Aurea Roma: Dalla Città Pagana alla Città Cristiana. Edited by Serena Ensoli and Eugenio La Rocca. Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider, pp. 159–60. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Chikako E. 2002. Animal Symbolism in Mesopotamia. A Contextual Approach. Wiener Offener Orientalistik 1. Vienna: Institut für Orientalistik der Universität Wien. [Google Scholar]

- White, Richard. 2011. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hagan, S.A. Reverberations of Persepolis: Persianist Readings of Late Roman Wall Decoration. Arts 2023, 12, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030102

Hagan SA. Reverberations of Persepolis: Persianist Readings of Late Roman Wall Decoration. Arts. 2023; 12(3):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030102

Chicago/Turabian StyleHagan, Stephanie A. 2023. "Reverberations of Persepolis: Persianist Readings of Late Roman Wall Decoration" Arts 12, no. 3: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030102

APA StyleHagan, S. A. (2023). Reverberations of Persepolis: Persianist Readings of Late Roman Wall Decoration. Arts, 12(3), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12030102