“Made by the Son of a Black”: José Campeche as Artist and Free Person of Color in Late Eighteenth-Century Puerto Rico

Abstract

:1. Race in the Spanish Colonial World and Late Eighteenth-Century Puerto Rico

Flinter also reported, however, that skin color or ancestry did not definitively determine an individual’s race, as he wrote,To be white, is a species of title of nobility in a country where slaves and people of color form the lower ranks of society, and where every grade of color, ascending from the jet-black negro to the pure white, carries with it a certain feeling of superiority.

As Flinter’s account suggests, the relationships between race, ancestry, skin color, and social hierarchy on the island were highly complicated and often proved somewhat ambiguous.50 When considering how race affected Puerto Rican society during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, however, it should be kept in mind that it still reflected and reinforced a social hierarchy that specifically restricted the social and economic mobility of non-white individuals, and particularly those of African descent, on the island as it did throughout the Spanish American world.51 People of color, in general, were not allowed to occupy the same social spaces or positions of privilege as white individuals. For example, in his examination of Puerto Rican society in the eighteenth century, historian Ángel López Cantos discusses two men of color—Miguel Enriquez and José Concepción—who became wealthy and gained accolades through their trades. Despite their economic gains, however, they drew the ire of the San Juan elite when they attempted to exercise social privileges usually reserved for the white population. Formal complaints were launched against Concepción, who is described as a “spurious mulatto, of low trades (pulpero y regatón)”, when he requested and secured an oratorio privado, or private chapel, so that he could celebrate mass and receive the sacraments without leaving his home as his wife was chronically ill. Governor Dufresne, who wrote the complaint that was sent to the Council of the Indies, noted that the granting of this privilege upon Concepción had “caused notable scandal and grievances” for “people of noble character, to see themselves equaled with the spurious mulatto, José Concepción”.52 People of color did seem to possess a good deal of freedoms and legal protections that those in other Spanish American locales did not, including the ability to travel freely across the island, gather publicly, gain an education, acquire land, own stores, and enter most occupations.53 However, taking the example of Concepción into account, it is difficult to determine the ease or prevalence with which people of color, including the Campeche family, exercised these freedoms while negotiating the social and legal systems in which they were disadvantaged.54Although these ancient families pride themselves on their descent…they yield to the custom of the country, which considers colour in some degree a title to respect,—a kind of current nobility. Even with this prejudice, descendents of coloured ancestors, who have managed to establish proofs of nobility (called whitewashing) are not excluded from society with that inexorable severity which prevails in the French and English colonies.

2. Artists/Artisans of Color and Art Production in the Spanish Colonial World

While the nature of this letter is not positive by any means, it does communicate that this visiting Spaniard knew of Campeche and his reputation as a skilled artist. His declaration that the royal portraits were “made by the son of a black named Tomás Campeche”, reveals that Martin knew who the artist’s father was and that he was a man of color. Further, by disagreeing with the notion that he should be called an “inimitable painter”, the Spaniard further conveys that Campeche was well respected by the local community. Cabildo records from 1808 discussing the commission of a portrait of Ferdinand VII for the celebrations surrounding his coronation describe Campeche as, “the skillful professor of painting José Campeche”.108 Furthermore, when the artist’s sisters, Lucía and María, appealed to the government for financial support following his death and claimed that he was “not only the best painter and only physiognomist in this city and island, but he was remarkably superior to many others in these faculties”, the Cabildo agreed with them and certified their statements about their brother.109 Following his death in November of 1809, his death certificate specifically classified him as a “patricio” (patrician, or noble), a term which indicates the respected place he had earned in San Juan society during his lifetime through his art and additional work for the church and state.110…the poor balcony [of the town hall] is so moth-eaten and old that is seems unable to hold the royal standard and the royal portraits. These were made by the son of a black named Tomás Campeche; though I cannot but say that it is praiseworthy that a young man of his dark color, quality, and class, without ever having left Puerto Rico or having had a master, and with no more ingenuity to enable him to do what little he does, it is impossible to agree that he should be called the inimitable painter José Campeche.

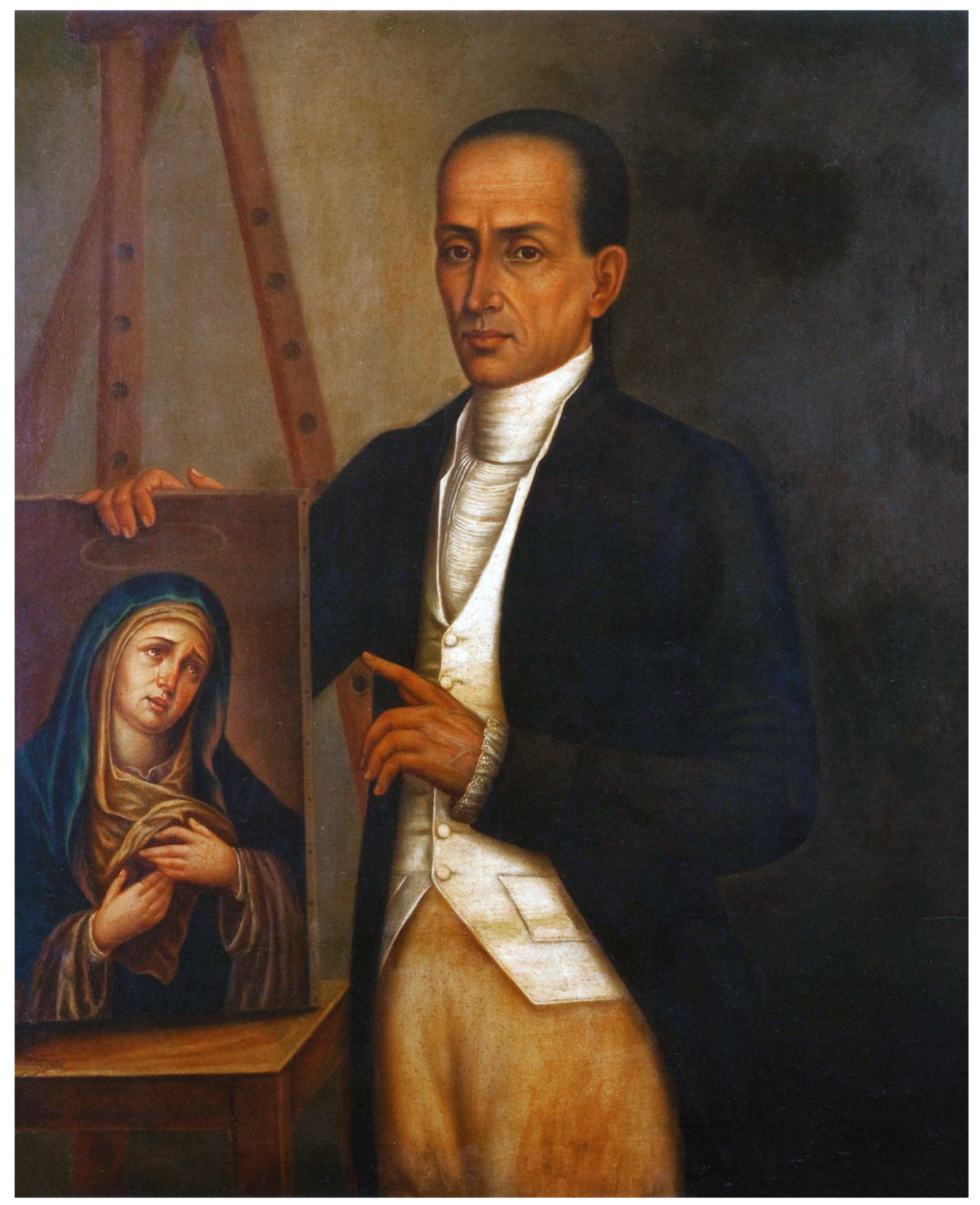

3. Campeche’s Self-Portrait

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Scholars have confirmed that Campeche created a self-portrait that is now lost but suggest that Atiles and Oller worked from it to create their own versions for a contest held by la Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País (The Economic Society of Friends of the Country) in 1855 (Dávila 1966, pp. 8–10; Taylor 1988, p. 103; Núñez Méndez 2018, pp. 204–5). |

| 2 | Francisco Oller’s copy of Campeche’s self-portrait is currently held in the Colección Ateneo Puertorriqueño in San Juan, Puerto Rico. It is reproduced in (Dávila 2010, p. 229). |

| 3 | María immigrated to Puerto Rico from La Laguna, a city on the island of Tenerife in the Canary Islands. Tomás purchased his freedom from Don Juan de Rivafrecha, a canon of San Juan Cathedral, for the sum of 1000 reales, which he still owed at the time of his marriage to María in 1734 (Taylor 1988, pp. 83–84). |

| 4 | For the purposes of this study, I use specific racial terms to refer to individuals and people groups when necessary to indicate their race and/or social status within their respective contemporary communities. While I strive for sensitivity, I also attempt to be as historically accurate in my word choice as possible, only using terms employed in historical documents from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. During this time, blanco, or white, referred to the European (sometimes referred to as peninsular) or criollo (white individuals born in the Americas) populations; gente de color, or people of color, was used as an all-encompassing term for individuals of African descent who were legally free; and negro, or black, referred to enslaved African individuals, generally. I use the terms “white”, “people of color”, and, “black”, or, “enslaved”, respectively to indicate these populations. If there is a specific word used in a historical document to refer to a specific person, for instance, pardo or mulatto, I will also use that term and include a citation. I feel it is necessary to note my specific use of language here, as an abundance of highly complex racial terminology existed in the Spanish colonial world, and I am choosing to specifically use terms pertinent to Puerto Rico that can be found in historical documents on the island during Campeche’s lifetime. See (Kinsbruner 1996; Dungy 2000). |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Tapia merely describes Campeche as “swarthy”, but not as mulatto or black, and he does not indicate Campeche’s father’s enslaved status or racial designation at all (Tapia y Rivera 1967, pp. 7–8, 25). Spanish art critic Juan Antonio Gaya Nuño suggested that Tapia’s description of Campeche within the biography included specific phenotypic details, such as the artist’s “rosy color” and “straight hair”, as an “apology” for Campeche’s blackness, implying that Tapia specifically chose to conceal or obscure Campeche’s mixed race within the narrative he constructed about the artist’s life (Dávila 1966, p. 8). |

| 8 | This is the first source I have located in my research that refers to Campeche’s race (Juncos 1914, p. 69). |

| 9 | |

| 10 | In an essay written by Arturo Dávila, for instance, the author discusses Campeche’s father’s biography and includes details about his life as an enslaved person, only to abruptly end his consideration of Campeche’s lived experience as a mixed-race individual in a slave-owning society by stating that Tomás potentially owned enslaved people himself after he was freed, which proves that Campeche, “…was thus brought up in an atmosphere in which the domestic slavery to which his father had been subjected was taken for granted, as an ancient custom dating back to the first Spanish settlements in the West Indies” (Dávila 1988). |

| 11 | For examples, see (Fischer 2004; Deans-Smith 2007, pp. 67–98; 2009, pp. 43–72; 2010, pp. 278–95; Rodriguez 2012; Niell 2012, pp. 293–318; 2020, pp. 81–94). |

| 12 | A criollo is an individual of Spanish descent who was born in the Americas. Historian Francisco Scarano contends that criollo identity formation in Puerto Rico began as early as the mid-eighteenth century on the island and gained strength with the emergence of creole oppositional politics in the 1810s and 1820s (Scarano 1996, pp. 1398–431). |

| 13 | |

| 14 | |

| 15 | (Schomburg 1934, p. 106). See also (Valdés 2017, pp. 1–2). |

| 16 | (Rodríguez-Silva 2012, p. 2). For more on the topic of race and nationalism in Puerto Rico, see (Scarano 1996; Torres 1998). |

| 17 | |

| 18 | Ibid. |

| 19 | (Du Bois [1903] 2007, pp. 8–9). See also (Gilroy 1993). |

| 20 | |

| 21 | (Martínez 2011, p. 12). Martinez analyzes in her book how the concept of limpieza de sangre originated in Spain, was transmitted to the New World, and changed in meaning over time from a religious concept to a racial one, underpinned by religion and ideas regarding decent and inheritance. Martinez argues that “in the Hispanic Atlantic World, Iberian notions of genealogy and purity of blood—both of which involved a complex of ideas regarding descent and inheritance…—gave way to particular understandings of racial difference”. See also (Martínez 2004, pp. 479–520). |

| 22 | (Twinam 2009, pp. 145–46). See also (Twinam 2015). |

| 23 | |

| 24 | (Martínez 2011). Moreover, sociologist and decolonial theorist Aníbal Quijano argues that the modern notion of “race” emerged at the onset of the colonial era to support the process of world classification. Specifically, he contends that the issues of “race” formed the basis of a rationale wielded by European powers to justify and reinforce imperial domination that became instrumental in the defense of colonial arrangements and in the legitimization of the system of forced labor in the Spanish Americas (Quijano and Wallerstein 1992, pp. 549–57; Quijano 2009, pp. 22–32; Moraña et al. 2008). |

| 25 | |

| 26 | |

| 27 | Ibid., pp. 63–109. See also (Martínez 2011, pp. 227–64). |

| 28 | |

| 29 | Ibid. |

| 30 | |

| 31 | Katzew defines calidad as “a combination of economic, social, and cultural, and racial factors that defined an individual” (Katzew 2004, p. 45). For more on calidad, see (Carrera 2010, p. 37; Niell 2015, p. 30). |

| 32 | |

| 33 | |

| 34 | |

| 35 | See (Guitar 2011, pp. 151–230). While historians very often state that the Taíno completely died out, that is not a valid claim—their numbers were just very few, and so historically they were not very visible. Further, they were often not included in Spanish census data, or they were grouped in with other categories (Rodríguez-Silva 2012, p. 4). See also (Feliciano-Santos 2019, pp. 1149–67). |

| 36 | |

| 37 | |

| 38 | In Kinsbruner’s estimation, it is difficult to determine which of these kinds of laws applied to free people of color in Puerto Rico (Kinsbruner 1996, pp. 22–25). |

| 39 | |

| 40 | |

| 41 | |

| 42 | There was a small population of “indios” present in Puerto Rico during the late eighteenth century, but the exact size of the population is unclear. See (Curtis and Scarano 2011, p. 207). |

| 43 | |

| 44 | Ibid. |

| 45 | Citing one padron, or census, from 1808, the colonial authorities counted the residents of a district of San Juan, street by street, listing the blancos, then pardo, then moreno individuals who owned property, then included a summary sheet at the end of the padron that listed the total blancos, pardos libres, morenos libres, pardos escalvos, and morenos esclavos in the neighborhood. A.G.P.R. Gobernadores Españoles. San Juan 1769–1800. Caja 558. Kinsbruner describes that free people of color were allowed to live wherever they wanted, as censes and property records demonstrate that they owned properties across all of the districts of San Juan. Additionally, Kinsbruner argues that “although whites and free people of color were separated by law in many ways, they were clearly willing to live side by side with each other” (Kinsbruner 1996, pp. 48–51, 53–81). |

| 46 | (Kinsbruner 1996, p. 1). In David Stark’s study of eighteenth-century Puerto Rican parish registers, he also notes that the terms pardo, mulatto, moreno, and negro are often used interchangeably to denote individuals of African descent, and he suggests that these were fluid rather than stable terms used to indicate the darkness of skin color (Stark 2007, p. 555). |

| 47 | Ibid., pp. 19–25. For primary source descriptions of these populations, see Iñigo Abbad y Lasierra, “CAPITULO XXX. Carácter y diferentes castas de los habitantes de la isla de San Juan de Puerto-Rico”, in (Abbad y Lasierra [1788] 2002, pp. 398–401), and André Pierre Ledru, “CHAPITRE XXVI. Générations mélangées, Moeurs et usages, Population, Produits des terres, Commerce, Température, Ouragans, Maladies”, in (Ledru 1810, pp. 161–87). |

| 48 | |

| 49 | Ibid. |

| 50 | Moreover, there were other social considerations at play in Puerto Rico at this time that should not be overlooked. As anthropologist Jorge Duany contends, owning property was arguably more important for someone’s social status than was their racial designation (Duany 1985, p. 21). |

| 51 | |

| 52 | |

| 53 | |

| 54 | For instance, historian Katherine Dungy argues that whether or not it was technically legal, very few people of color would have been found in the higher ranks of business in Puerto Rico (Dungy 2005, p. 102). |

| 55 | |

| 56 | Ibid., p. 110. |

| 57 | Paula Mues Orts, “Merezca ser hidalgo y libre el que pintó lo santo y respetado: La defensa novohispana del arte de la pintura”, in (Museo de la Basílica de Guadalupe 2001, p. 38), and (Deans-Smith 2009, pp. 44–45). |

| 58 | (Jovellanos 1858, p. 542). The original text reads: “Sin duda que los eminentes artistas son necesarios en una nacion para su gloria y ornamento y para el desempeño de los grandes objetos que el Gobierno […]”. |

| 59 | |

| 60 | |

| 61 | |

| 62 | Ibid. |

| 63 | |

| 64 | Ibid., pp. 69–70. |

| 65 | Ibid., p. 45. |

| 66 | Ibid. |

| 67 | |

| 68 | |

| 69 | |

| 70 | Ibid., pp. 122–23. |

| 71 | |

| 72 | Ibid. |

| 73 | (Donahue-Wallace 2008, p. 225). See also (Donahue-Wallace 2017). |

| 74 | Ibid., p. 228. |

| 75 | |

| 76 | |

| 77 | |

| 78 | |

| 79 | Ibid. |

| 80 | |

| 81 | Ibid., p. 60. |

| 82 | Ibid. For more about tensions regarding race and the growing African population on the island at this time, see (Stolcke (Martinez-Alier) 1989). |

| 83 | |

| 84 | Ibid., pp. 295, 309. |

| 85 | |

| 86 | Ibid., pp. 148–150. |

| 87 | Ibid., p. 37. |

| 88 | Ibid., p. 82. |

| 89 | In English, “…mulattos, blacks, zambos nor other castes…” (Mesa and Gisbert 1982, p. 310). |

| 90 | |

| 91 | |

| 92 | Ibid., p. 241. |

| 93 | Ibid. See also (Johnson 2011). |

| 94 | |

| 95 | |

| 96 | Ibid., pp. 83–84. See also (Dávila 1988) for more information about Tomás’ properties and buying himself out of slavery from his master. |

| 97 | (Vidal 2004, p. 104; Dávila 1959, pp. 12–17; 1999). In the history of artwork attribution to Campeche, institutions occasionally classify paintings as “Taller Campeche (Campeche Workshop)” if the work can be dated to his general era and is similar to his subject matter but does not seem to match his style or known level of skill. This indicates a general academic acceptance of the existence of the Campeche family workshop. Moreover, Dávila suggests that Campeche’s brother-in-law, Domingo de Andino, who was a mulatto silversmith and musician, arranged for Campeche to join the cathedral music staff at an early age. He also speculates as to whether or not Campeche may have received training in silversmithing from him. These possibilities further illustrate the community of artisans that surrounded the Campeche family (Dávila 1962, pp. 36–38). The possibility that Campeche trained his sister Juana is also interesting and requires more research, as there are comparable instances in the Spanish colonial world where master artists and artisans extended their training to their daughters within the context of the family workshop. See (Romero-Martín 2016; Gontar 2018, p. 102). |

| 98 | |

| 99 | (Johnson 1986, pp. 230–34). For general details about guild structure and training in Europe, see (Humfrey 1995; Hafter and Kushner 2015). |

| 100 | Taylor argues that Campeche trained in his father’s workshop to some extent, but then worked alone until he needed help with an increase in commissions. He does not really look at it as a family workshop, but rather as something built up around Campeche (Taylor 1988, pp. 85–86). |

| 101 | |

| 102 | San Juan and San Germán were the two main urban centers in Puerto Rico during the eighteenth century. |

| 103 | (Vidal 1994, pp. 35–36). Felipe also had a son named Vicente who played the organ and collaborated with Tiburcio on sculpture work. For more on santeros and the Espadas, see (Lange 1975; Díaz 1986; Román et al. 2003; Sullivan 2006, pp. 39–55). |

| 104 | Ibid., p. 48. |

| 105 | More research is required in this area. Little is known about the methods of training of artisans in the Spanish colonial world beyond the traditional guild structure, and little is known about black artists and artisans in general. Research is also needed about the commission and use of art by individuals of African descent. For one essay on the influence of African art practices on art production and use in the Americas, see (Sullivan 2006). |

| 106 | |

| 107 | Text from this letter is recorded in (Torres Ramírez 1961). In the original Spanish, “…todo se reduce a un pobre balcon hay en ella, tan apolillado y tan viejo que parece incapaz de sostener el pendon y los reales retratos. Estos fueron herchos por el hijo de un negro nombrado Tomas Campeche; que aunque no puedo menos de decir que es virtud que un mozo de su oscuro color, calidad y clase sin haber salido nunca de Puerto Rico, sin haber tenido maestro, y si solo con su ingenio haya salido y sepa hacer lo poco que hace, nadie ha aprobado el que se le diga el inimitable pintor José Campeche”. |

| 108 | (Caro 1970, p. 399). In the original Spanish, “…diputados soliciten, con todo empeño, una lámina o retrato de nuestro soberano actual para que haciéndose sacar una copia fiel por el hábil profesor de pintura José Campeche pueda colocarse bajo el correspondiente dosel en el balón de esta casa consistorial”. |

| 109 | |

| 110 | Taylor describes that the term patricio designated an elite mulatto member of society (Taylor 1988, pp. 52–53). |

| 111 | |

| 112 | |

| 113 | See, for instance, the similarities between his Nuestra Señora de la Concepción and Juan Antonio Salvador Carmona’s seventeenth-century etching La Inmaculada Concepción (Taylor 1988, pp. 90, 94–96). |

| 114 | |

| 115 | |

| 116 | For the concept of “colonial literacy”, see (Rappaport and Cummins 2011). For more on the agency of free women of color in San Juan, see (Matos Rodríguez 1999; 2010, pp. 202–18). |

| 117 | See, for instance, Nicolas de Largillierre’s Portrait of a Woman, Possibly Madame Claude Lambert de Thorigny (Marie Marguerite Bontemps, 1668–1701), and an Enslaved Servant from 1696, currently held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. |

| 118 | |

| 119 | Ibid., p. 3. |

| 120 | Ibid., p. 8. |

| 121 | Ibid., pp. 5–7. |

| 122 | Ibid. Art historian Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby’s considers the contradiction at play here in her analysis of Anne-Louis Girodet’s (1767–1824) Portrait of Citizen Belley, Ex-Representative of the Colonies from 1797. In her study, she argues that in order for Girodet’s portrait to “coalesce Belly as physical matter (painting’s valorized object)”, it also had to “challenge a dominant invidious identification of him with mere matter (colonial society’s exploited object)” (Grigsby 2002, pp. 13–14). |

| 123 | |

| 124 | Diego Velázquez’s painting Las Meninas from 1656 is held in the collection of the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, Spain. |

| 125 | (Roberts 2013, p. 62). See also (Gresle 2006, p. 211). |

| 126 | At the time this portrait was painted, 1650, Pareja was still enslaved, but Velázquez released him shortly thereafter and he proceeded to work as an independent painter in Madrid (Pullins and Valdés 2023). |

| 127 | |

| 128 | Ibid., pp. 51–53. See also Clara Bargellini, “Originality and Invention in the Painting of New Spain”, in (Pierce et al. 2004, pp. 88–89), and Rogelio Ruiz Gomar, “Unique Expressions: Painting in New Spain”, in (Pierce et al. 2004, pp. 238–39). |

| 129 | |

| 130 | José de Ibarra, quoted in (Ramirez Montes 2001, pp. 103–28). |

| 131 | (Hyman 2017, p. 122). See also (Bargellini 2012, pp. 121–38). |

| 132 | Notable signatures by Campeche include, “José Campeche la pinto en Puerto Rico año 1785”, on the Dama a Caballo from 1985 currently in the Museo de Arte de Ponce, and “José Campeche lo inven[to] ano 1801” on his La Vision de San Francisco from 1801 held by the Colección de la Arquidiócesis de San Juan de Puerto Rico. |

| 133 | (José Jackes Quiroga n.d.). See also (Rodriguez 2012). |

| 134 | Ibid. |

| 135 | Ibid. |

| 136 | Ibid. |

| 137 | |

| 138 | Ibid., pp. 14–15. Escobar exercised the practice of gracias al sacar and Rodriguez argues that Escobar’s artistic practice made this personal transformation possible. Ibid., p. 39. |

| 139 | |

| 140 | |

| 141 | This is comparable to the way in which women began painting their own artist self-portraits in the sixteenth century to demand their place in the art world but did so in a way that utilized the visual language of artist portraiture that already existed and was defined by male artists. See for instance, art historian Mary Garrard’s analysis of Sofonisba Anguissola’s self-portrait and her discussion of “female mimicry” (Garrard 1994, pp. 561–62). |

References

- Abbad y Lasierra, Iñigo. 2002. Historia Geográfica, Civil y Natural de La Isla de San Juan Bautista de Puerto Rico. Edited by José Julián Acosta and Gervasio L. García. Puerto Rico: Centro de Investigaciones Históricas. First published 1788. [Google Scholar]

- Assunção, Matthias Röhrig, and Michael Zeuske. 1998. ‘Race’, Ethnicity and Social Structure in 19th Century Brazil and Cuba. Ibero-Amerikanisches Archiv 24: 375. [Google Scholar]

- Bagneris, Mia L. 2018. Colouring the Caribbean: Race and the Art of Agostino Brunias. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bargellini, Clara. 2012. El artista ‘inventor’ novohispano. In Nombrar y explicar: La terminología en el estudio del arte ibérico y lati- noamericano. Edited by Patricia Díaz Cayeros and Peter Krieger. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 121–38. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, Enrique T. 1932. Campeche Filiación Genealógica Documentada. Alma Latina 21: 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, Enrique T. 1972. El Nombre Campeche in Puerto Rico. In La Torre—Revista General de La Universidad de Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico: University of Puerto Rico, pp. 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bleichmar, Daniela. 2012. Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Mavis Christine. 1988. The Maroons of Jamaica, 1655–1796: A History of Resistance, Collaboration & Betrayal. Granby: Bergin & Garvey. [Google Scholar]

- Caro, Aída R. 1970. Actas del Cabildo de San Juan Bautista de Puerto Rico: 1803–1809. San Juan: Municipio de San Juan. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, Magali M. 2010. Imagining Identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Paintings. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Childs, Matt D. 2006. The 1812 Aponte Rebellion in Cuba and the Struggle against Atlantic Slavery. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Craven, David. 2017. Art History as Social Praxis: The Collected Writings of David Craven. Edited by Brian Winkenweder. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, Katherine J., and Francisco Scarano. 2011. Puerto Rico’s Population ‘Padrones’, 1779–1802. Latin American Research Review 46: 200–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila, Arturo V. 1959. José Campeche y Sus Hermanos En El Convento de Las Carmelitas. Revista Del Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña 2: 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dávila, Arturo V. 1962. El Platero Domingo de Andino (1737–1820) Maestro de Musica de Campeche. Revista Del Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña 3: 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dávila, Arturo V. 1966. Los Retratos de José Campeche. Revista del Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña 33: 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dávila, Arturo V. 1988. Emblems of His City: José Campeche and San Juan = Emblemas de Su Ciudad: José Campeche y San Juan. New York: El Museo del Barrio. [Google Scholar]

- Dávila, Arturo V. 1999. José Campeche y el Taller Familiar: Pinturas en la Colección del Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte, Facultad de Humanidades, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto Río Piedras. Río Piedras: University of Puerto Rico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dávila, Arturo V. 2010. Campeche: Mito y Realidad. San Juan: Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico. [Google Scholar]

- Deans-Smith, Susan. 2007. ‘This Noble and Illustrious Art’: Painters and the Politics of Guild Reform in Early Modern Mexico City, 1674–1768. In Mexican Soundings. Edited by Susan Deans-Smith and Eric Van Young. London: Institute for the Study of the Americas, pp. 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- Deans-Smith, Susan. 2009. ‘Dishonor in the Hands of Indians, Spaniards, and Blacks’: The (Racial) Politics of Painting in Early Modern Mexico. In Race and Classification: The Case of Mexican America. Edited by Susan Deans-Smith and Ilona Katzew. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 43–72. [Google Scholar]

- Deans-Smith, Susan. 2010. ‘A Natural and Voluntary Dependence’: The Royal Academy of San Carlos and the Cultural Politics of Art Education in Mexico City, 1786–1797. Bulletin of Latin American Research 29: 278–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, Irene Curbelo de. 1986. Art of the Puerto Rican Santeros. San Juan: Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, María Elena. 2009. Conjuring Identities: Race, Nativeness, Local Citizenship, and Royal Slavery on an Imperial Frontier (Revisiting El Cobre, Cuba). In Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America. Edited by Andrew B. Fisher and Matthew D. O’Hara. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 197–224. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue-Wallace, Kelly. 2008. Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521–1821. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue-Wallace, Kelly. 2017. Jerónimo Antonio Gil and the Idea of the Spanish Enlightenment. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. 2007. The Souls of Black Folk. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Duany, Jorge. 1985. Ethnicity in the Spanish Caribbean: Notes on the Consolidation of Creole Identity in Cuba and Puerto Rico, 1762–1868. In Caribbean Ethnicity Revisited. Edited by Stephen D. Glazier. New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dungy, Kathryn R. 2005. Live and Let Live: Native and Immigrant Free People of Color in Early Nineteenth Century Puerto Rico. Caribbean Studies 33: 79–111. [Google Scholar]

- Dungy, Kathryn Renee. 2000. ‘A Fusion of the Races’: Free People of Color and the Growth of Puerto Rican Society, 1795–1848. Ph.D. dissertation, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano-Santos, Sherina. 2019. Negotiation of Ethnoracial Configurations among Puerto Rican Taíno Activists. Ethnic and Racial Studies 42: 1149–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Sibylle. 2004. Modernity Disavowed: Haiti and the Cultures of Slavery in the Age of Revolution. Durham: Duke University Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Andrew B., and Matthew D. O’Hara. 2009. Introduction: Racial Identities and their Interpreters in Colonial Latin America. In Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America. Edited by Andrew B. Fisher and Matthew D. O’Hara. Durham: Duke University Press Books, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Flinter, George D. 1832. An Account of the Present State of the Island of Puerto Rico. Republished 2010. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garrard, Mary D. 1994. Here’s Looking at Me: Sofonisba Anguissola and the Problem of the Woman Artist. Renaissance Quarterly 47: 556–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geigel de Gandia, Luisa. 1972. La genealogía y el apellido de Campeche. Puerto Rico: Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña. [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy, Paul. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gontar, Cybèle. 2018. The ‘celebrated, self-taught Portrait Painter’: Josef Salazar y Mendoza of New Orleans. In Salazar: Portraits of Influence in Spanish New Orleans, 1785–1802. Edited by Cybèle Gontar. New Orleans: University of New Orleans Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gresle, Yvette. 2006. Foucault’s Las Meninas and Art-Historical Methods. Journal of Literary Studies 22: 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigsby, Darcy Grimaldo. 2002. Extremities: Painting Empire in Post-Revolutionary France. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guitar, Lynne A. 2011. Negotiations of Conquest. In The Caribbean: A History of the Region and Its Peoples. Edited by Stephan Palmié and Francisco A. Scarano. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 151–230. [Google Scholar]

- Hafter, Daryl M., and Nina Kushner. 2015. Women and Work in Eighteenth-Century France. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Stuart. 2001. Who Needs Identity? In Identity: A Reader. Edited by Paul du Gay, Jessica Evans and Peter Redman. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffnung-Garskof, Jesse. 2011. To Abolish the Law of Castes: Merit, Manhood and the Problem of Colour in the Puerto Rican Liberal Movement, 1873–1892. Social History 36: 312–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostos, Adolfo de. 1979. Historia de San Juan ciudad murada: Ensayo acerca del proceso de la civilización en la ciudad española de San Juan Bautista de Puerto Rico. 1521–1898. San Juan: Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña. [Google Scholar]

- Humfrey, Peter. 1995. Painting in Renaissance Venice. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, Aaron M. 2017. Inventing Painting: Cristóbal de Villalpando, Juan Correa, and New Spain’s Transatlantic Canon. Art Bulletin 99: 102–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Lyman. 1986. Artisans. In Cities & Society in Colonial Latin America. Edited by Louisa Schell Hoberman and Susan Migden Socolow. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 227–50. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Lyman. 2011. Workshop of Revolution: Plebeian Buenos Aires and the Atlantic World, 1776–1810. Durham: Duke University Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jovellanos, Gaspar Melchor de. 1858. Obras Publicadas e Inéditas de D. Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos. Biblioteca de Autores Españoles Desde La Formación Del Lenguaje Hasta Nuestros Días. Madrid: M. Rivadeneyra, pp. 46, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Juncos, Manuel Fernández. 1914. José Campeche, Pintor Puertorriqueño. Revista de Las Antillas 2: 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Katzew, Ilona. 2004. Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Katzew, Ilona. 2015. Valiant Styles: New Spanish Painting, 1700–1785. In Painting in Latin America, 1550–1820: From Conquest to Independence. Edited by Luisa Elena Alcalá and Jonathan Brown. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 149–203. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsbruner, Jay. 1996. Not of Pure Blood: The Free People of Color and Racial Prejudice in Nineteenth-Century Puerto Rico. Durham: Duke University Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Herbert S., and Ben Vinson. 2007. African Slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lafont, Anne. 2017. How Skin Color Became a Racial Marker: Art Historical Perspectives on Race. Eighteenth-Century Studies 51: 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lange, Yvonne Marie. 1975. Santos: The Household Wooden Saints of Puerto Rico. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lavina, Javier, and Michael Zeuske, eds. 2014. The Second Slavery: Mass Slaveries and Modernity in the Americas and in the Atlantic Basin. Zürich: LIT Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Ledru, André Pierre. 1810. Voyage aux îles de Ténériffe, la Trinité, Saint-Thomas, Sainte-Croix et Porto Ricco. Paris: A. Bertrand, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- López Cantos, Ángel. 1986. Puerto Rico Negro. Puerto Rico: Editorial Cultural. [Google Scholar]

- López Cantos, Ángel. 2000. Los puertorriqueños: Mentalidad y actitudes, siglo XVIII. Puerto Rico: Universidad de Puerto Rico. [Google Scholar]

- Lucero, Bonnie A. 2019. A Cuban City, Segregated: Race and Urbanization in the Nineteenth Century. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Ortiz, Agnes, and Angela Rosenthal, eds. 2013. Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, María Elena. 2004. The Black Blood of New Spain: Limpieza de Sangre, Racial Violence, and Gendered Power in Early Colonial Mexico. The William and Mary Quarterly 61: 479–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, María Elena. 2011. Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matos Rodríguez, Félix V. 1999. Women and Urban Change in San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1820–1868. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Matos Rodríguez, Félix V. 2010. Libertas Citadinas: Free Women of Color in San Juan, Puerto Rico. In Beyond Bondage: Free Women of Color in the Americas. Edited by David Barry Gaspar and Darlene Clark Hine. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, pp. 202–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mengs, Anton Raphael. 1796. The Works of Anthony Raphael Mengs. London: Printed for R. Faulder, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mesa, José de, and Teresa Gisbert. 1982. Historia de La Pintura Cuzqueña. Lima: Fundación A.N. Wiese, Banco Wiese, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Moraña, Mabel, Enriqué Dussel, and Carlos A. Jáuregui, eds. 2008. Coloniality at Large: Latin America and the Postcolonial Debate. Durham: Duke University Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mues Orts, Paula. 2009. El Pintor Novohispano José de Ibarra: Imágenes Retóricas y Discursos Pintados. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Museo de la Basílica de Guadalupe, ed. 2001. El Divino Pintor: La Creación de María de Guadalupe en el Taller Celestial. México: Museo de la Basílica de Guadalupe. [Google Scholar]

- National Gallery of Art. n.d. Guilds (Arti). Italian Renaissance Learning Resources. Available online: http://www.italianrenaissanceresources.com/units/unit-3/essays/guilds-arti/ (accessed on 1 June 2019).

- Niell, Paul. 2012. Founding the Academy of San Alejandro and the Politics of Taste in Late Colonial Havana, Cuba. Colonial Latin American Review 21: 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niell, Paul. 2015. Urban Space as Heritage in Late Colonial Cuba: Classicism and Dissonance on the Plaza de Armas of Havana, 1754–1828. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Niell, Paul. 2020. The Coloniality of Aesthetics: Regulating Race and Buen Gusto in Cuba’s 19th century Academy. In Academies and Schools of Art in Latin America. Edited by Oscar E. Vázquez. New York: Routledge, pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez Méndez, Elsaris. 2018. “El Recuerdo de José Campeche Siempre Ha Subsistido En Nuestra Antilla”: La Construcción de Un Icono Nacional Puertorriqueño. In “Yngenio et Art”e: Elogio, Fama y Fortuna de la Memoria del Artista. Edited by María del Mar Albero Muñoz and Manuel Pérez Sánchez. Madrid: Fundación Universitaria Española, pp. 198–214. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, Donna, Rogelio Ruiz Gomar, and Clara Bargellini, eds. 2004. Painting a New World: Mexican Art and Life, 1521–1821. Denver: Denver Art Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Pullins, David, and Vanessa K. Valdés. 2023. Juan de Pareja: An Afro-Hispanic Painter in the Age of Velàzquez. New York City: Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, Aníbal, and Immanuel Wallerstein. 1992. Americanity as a Concept, or the Americas in the Modern World System. International Social Sciences Journal 44: 549–57. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, Aníbal. 2009. Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality. In Globalization and the Decolonial Option. Edited by Walter D. Mignolo and Arturo Escobar. London: Routledge, pp. 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Quilley, Geoff, and Kay Dian Kriz, eds. 2003. An Economy of Colour: Visual Culture and the North Atlantic World, 1660–1830. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez Montes, Mina. 2001. En defensa de la pintura. Ciudad de México, 1753. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 23: 103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rappaport, Joanne, and Tom Cummins. 2011. Beyond the Lettered City: Indigenous Literacies in the Andes. Durham: Duke University Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Helene E. 2013. Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography: Themes Depicted in Works of Art. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, Linda Maria. 2012. Artistic Production, Race, and History in Colonial Cuba, 1762–1840. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Silva, Ilena M. 2012. Silencing Race: Disentangling Blackness, Colonialism, and National Identities in Puerto Rico. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Román, Dulce María, Manuel A. Vásquez, and Teodoro Vidal. 2003. Santos: Contemporary Devotional Folk Art in Puerto Rico. Gainesville: Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, University of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Martín, Juanjo. 2016. Craftswomen in Times of Change: Artisan Family Strategies in Nineteenth Century Barcelona. Mélanges de l’École Française de Rome—Italie et Méditerranée Modernes et Contemporaines. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Gomar, Rogelio. 1991. El gremio y la cofradia de pintores en la Nueva Espana. In Juan Correa: Su vida y su obra. Edited by Elisa Vargas Lugo and Gustavo Curiel. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Aut6noma de Mexico, vol. 3, pp. 203–22. [Google Scholar]

- Scarano, Francisco A. 1996. The Jíbaro Masquerade and the Subaltern Politics of Creole Identity Formation in Puerto Rico, 1745–1823. The American Historical Review 101: 1398–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomburg, Arturo. 1934. José Campeche, 1752–1809, A Puerto Rican Negro Painter. Mission Fields at Home 6: 106–8. [Google Scholar]

- Seed, Patricia. 1982. Social Dimensions of Race: Mexico City, 1753. The Hispanic American Historical Review 62: 569–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shiner, Larry. 2001. The Invention of Art: A Cultural History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, David M. 2007. Rescued from Their Invisibility: The Afro-Puerto Ricans of Seventeenth-and Eighteenth-Century San Mateo de Cangrejos, Puerto Rico. The Americas 63: 551–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolcke (Martinez-Alier), Verena. 1989. Marriage, Class and Colour in Nineteenth-Century Cuba: A Study of Racial Attitudes and Sexual Values in a Slave Society. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Edward. 2006. The Black Hand: Notes on the African Presence in the Visual Arts of Brazil and the Caribbean. In The Arts in Latin America, 1492–1820. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tapia y Rivera, Alejandro. 1967. Vida del pintor puertorriqueño José Campeche. Reprint of 1855 edition. Barcelona: Ediciones Rumbos. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, René. 1988. José Campeche and His Time, 1751–1809. Ponce: Museo de Arte de Ponce. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Krista. 2011. A Sidelong Glance: The Practice of African Diaspora Art History in the United States. Art Journal 70: 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, Beth Fowkes. 1999. Picturing Imperial Power: Colonial Subjects in Eighteenth-Century British Painting. Durham: Duke University Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- Tomich, Dale. 2003. The Wealth of Empire: Francisco Arango y Parreño, Political Economy, and the Second Slavery in Cuba. Comparative Studies in Society and History 45: 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Ramírez, Bibiano. 1961. Sucesos Acaecidos en San Juan de Puerto Rico, en la Proclamación de Carlos IV. Revista del Instituto de Cultra Puertorriqueña 12: 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, Arlene. 1998. La Gran Familia Puertorriquena, Ej Preita de Belda (The Great Puerto Rican Family is Really Really Black). In Blackness in Latin America and the Caribbean: Eastern South America and the Caribbean. Edited by Norman E. Whitten and Arlene Torres. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 285–306. [Google Scholar]

- Twinam, Ann. 2009. Purchasing Whiteness: Conversations on the Essence of Pardo-ness and Mulatto-ness at the End of Empire. In Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America. Edited by Andrew B. Fisher and Matthew D. O’Hara. Durham: Duke University Press Books, pp. 141–66. [Google Scholar]

- Twinam, Ann. 2015. Purchasing Whiteness: Pardos, Mulattos, and the Quest for Social Mobility in the Spanish Indies. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, Vanessa K. 2017. Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente Escobar, Portrait of José Jackes Quiroga. n.d. Oil on Canvas. Digital Aponte, 9 December 2017. Available online: http://aponte.hosting.nyu.edu/escobar-3/ (accessed on 1 June 2019).

- Vidal, Teodoro. 1994. Los Espada: Escultores Sangermeños. San Juan: Ediciones Alba. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, Teodoro. 2004. José Campeche: Portrait Painter of an Epoch. In Retratos: 2000 Years of Latin American Portraits. Edited by Elizabeth P. Benson and Marion Oettinger Jr. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 102–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Kathleen. 2009. The Performance of Freedom: Maroons and the Colonial Order in Eighteenth-Century Jamaica and the Atlantic Sound. The William and Mary Quarterly 66: 45–86. [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Marsden, Joanna. 1998. Renaissance Self-Portraiture: The Visual Construction of Identity and the Social Status of the Artist. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thames, E.K. “Made by the Son of a Black”: José Campeche as Artist and Free Person of Color in Late Eighteenth-Century Puerto Rico. Arts 2023, 12, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040126

Thames EK. “Made by the Son of a Black”: José Campeche as Artist and Free Person of Color in Late Eighteenth-Century Puerto Rico. Arts. 2023; 12(4):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040126

Chicago/Turabian StyleThames, Emily K. 2023. "“Made by the Son of a Black”: José Campeche as Artist and Free Person of Color in Late Eighteenth-Century Puerto Rico" Arts 12, no. 4: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040126

APA StyleThames, E. K. (2023). “Made by the Son of a Black”: José Campeche as Artist and Free Person of Color in Late Eighteenth-Century Puerto Rico. Arts, 12(4), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040126