1. Introduction

On two frigid evenings in early January 1973, Chilean media artist Juan Downey exhibited one of his most intriguing—if one of his most opaque—installations,

Plato Now. Held at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York, it was conceived as a restaging of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave but reimagined from the artist’s own historical moment. It would be a version of Plato for

now. A version of Plato set against the backdrop of the Information Age, complete with closed-circuit video systems, neuronal sensors that could trigger audio playback, performers in the place of shackled prisoners, and, of course, shadows [

Figure 1].

It is important to mention the installation’s source material from the start for three reasons. Firstly, it identifies the philosophical coordinates of Downey’s reimagining right away. While this does not tell us what kind of theoretical intervention Downey is making, it does make clear the arena in which that intervention is operating. Remember that the Allegory of the Cave concerns the nature of how we experience the world and the different—and in Plato’s original, hierarchical—roles that the mind and sense play in that process. This is the remit of Plato Now too.

Secondly, there are many moving parts to this installation, which is also a performance of sorts, as well as a multi-screen, real-time video environment. It is easy for the shadowy space of Plato Now to appear inscrutable, and effort is required to make all its elements and their interactions legible. Indeed, some of the most meaningful features of this space are, by their nature, invisible. Outlining the philosophical stakes of the installation from the outset thus provides a coherent frame through which all its formal relations can be understood.

Thirdly, being clear about Plato Now’s inherently philosophical character gestures towards the reason why the installation fits within the broader aims of the current Arts special issue: Framing the Virtual. Its goal is to explore and unfold the relations between contemporary media art practices (like Downey’s) and the body of thought regarded as “New Materialist philosophy” or just the “New Materialisms.” While a more thorough account of these new materialisms will be provided in time, it suffices to say they find common ground in a rigorous questioning of the very same binaries that Plato’s Allegory of the Cave illustrated—between the world of the mind and the derivative world of sense. For new materialists, no matter how heterogenous this collection of ideas is, mind and thought are viewed in intimate and co-constitutive relation with the sensate world, and especially the matter that makes it. At its most basic, this article contends Downey’s Plato Now put forth something significantly similar in 1973.

I argue that Plato Now upended the binarism of its source material by assembling a relay of invisible electromagnetic energies, brain waves, video signals, and telepathic communications, such that the interior space of mind and exterior sensual reality became speculatively entangled. As far out as this series of relations might first appear, it will be borne out through a close-looking of the installation itself, its preparatory materials, and Downey’s own thinking on the radical potentials of electromagnetism as an invisible yet intimate means of connection. Within Plato Now, that is, electromagnetic energy mediates the relations between its wildly different elements. Through this specifically energetic connectivity, the significance of Plato Now begins to surface.

Energy and matter are not interchangeable.

1 Whereas the vibrancy of matter—its capacity for agency, transformation, generativity—is at the heart of new materialist thinking, in

Plato Now that same liveliness is embodied by signals, waves, and fields of electromagnetic energy. This electromagnetic orientation is a defining feature of the artist’s practice more broadly. And while Downey’s installation and new materialist philosophy both privilege heterogenous assemblages that crisscross the human and nonhuman domains, the animating forces behind their assemblages require careful distinction. In Downey’s case, it is a concrete (if speculatively imagined) form of energy.

This specificity is critical. On the one hand, it emphasizes Downey’s link to the Information Age, a moment thoroughly transformed by electromagnetic technologies, their infrastructures, and attendant discourses. These include video, early computing, global satellite telecommunications, cybernetics, and media ecology—all of which played important roles in the artist’s practice. On the other hand, and more philosophically, I believe Downey’s energetic interest has implications for our understanding of the media arts—integrated as they are with electronics, they are literally brought to life by electromagnetic energy. This is something Downey knew well. The vibrancy of matter has been a powerful force in contemporary thought and art over the last decade, but when it comes to the glowing screens or sensors of the media arts, they require energy as much as they do matter. How this can change the histories and theories we write of them is something that needs to be explored, and Downey can help in this.

This article proceeds in five sections. The first is a deep dive into the installation itself. This section provides an account of what it might have been like to experience Plato Now, an analysis of several preparatory materials made by Downey leading up to its exhibition, and a comprehensive outlining of its different components. The aim here is to clarify the invisible action of the installation and the program of relations from which that action emerged. Here, the link between Plato Now, second-order cybernetic feedback loops, and the new materialist interest in assemblages is explored.

With a whole series of invisible energetic connections articulated in the first section, the second section details what, within Downey’s practice, could have enabled those connections. Here, attention is turned towards Downey’s theory of “invisible architecture”, an idea which recognized and attempted to harness the imperceptible energies of the Information Age. This section introduces and historicizes a key concept for the article: Downey’s imagining of electromagnetic energy as medium and media. It is through this lens that the entities and connections of Plato Now are seen energetically.

With this energetic background explicated, the third section is a brief recounting of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. This familiarizes the reader with the philosophic coordinates Downey was operating in and affords them with what they need to know in order to fully grasp the philosophic vision of Plato Now.

That philosophic vision, and the way in which it emerged concretely through the specifics of the installation, is the object of the fourth section. The main claim here is that, rather than a hard distinction between mind (the exterior of Plato’s Cave) and perception (the interior of Plato’s Cave), Downey fuses the two together in topological twist, intimately readable within the media arts of the time. As that twist is unfolded, it is put into conversation with the new materialist interests in the agency of the material world and the ontological co-constitution of meaning and matter.

The conclusion reiterates the historical specificity of Downey’s imaging electromagnetism as medium and media vis-à-vis the Information Age, and extrapolates this into an insight about the energetic nature of the media arts.

2. Concerning the Visible and Invisible

Plato Now was first exhibited on 6 and 7 January 1973, in the sculpture court of the Everson Museum of Art. On both nights it began at 8:30 p.m. and, with the sun setting hours earlier, visitors would have found little reprieve from the dark inside.

Plato Now had only two sources of light: a large spotlight at one end of the space and a row of faintly glowing CCTV monitors at the other. There were nine monitors in all, situated just before a row of nine performers (one monitor per performer) who faced away from them. The performers, cross-legged atop pillows, sat towards the wall opposite the spotlight. Among them were Downey himself, his wife Marilys Belt de Downey, soon-to-be famous video artist Bill Viola, and prominent video art curator David Ross.

2 Each of the performers were equipped with headphones and neuronal sensors that monitored their brain activity.

They were all instructed to meditate. If, throughout the course of the performance, their brains produced enough alpha waves—a frequency of brain wave linked to focus and meditative concentration—their sensors would detect this, and then trigger the playback of prerecorded excerpts of Plato’s dialogues through the headphones. The excerpts were taken from

The Republic,

Timaeus, and

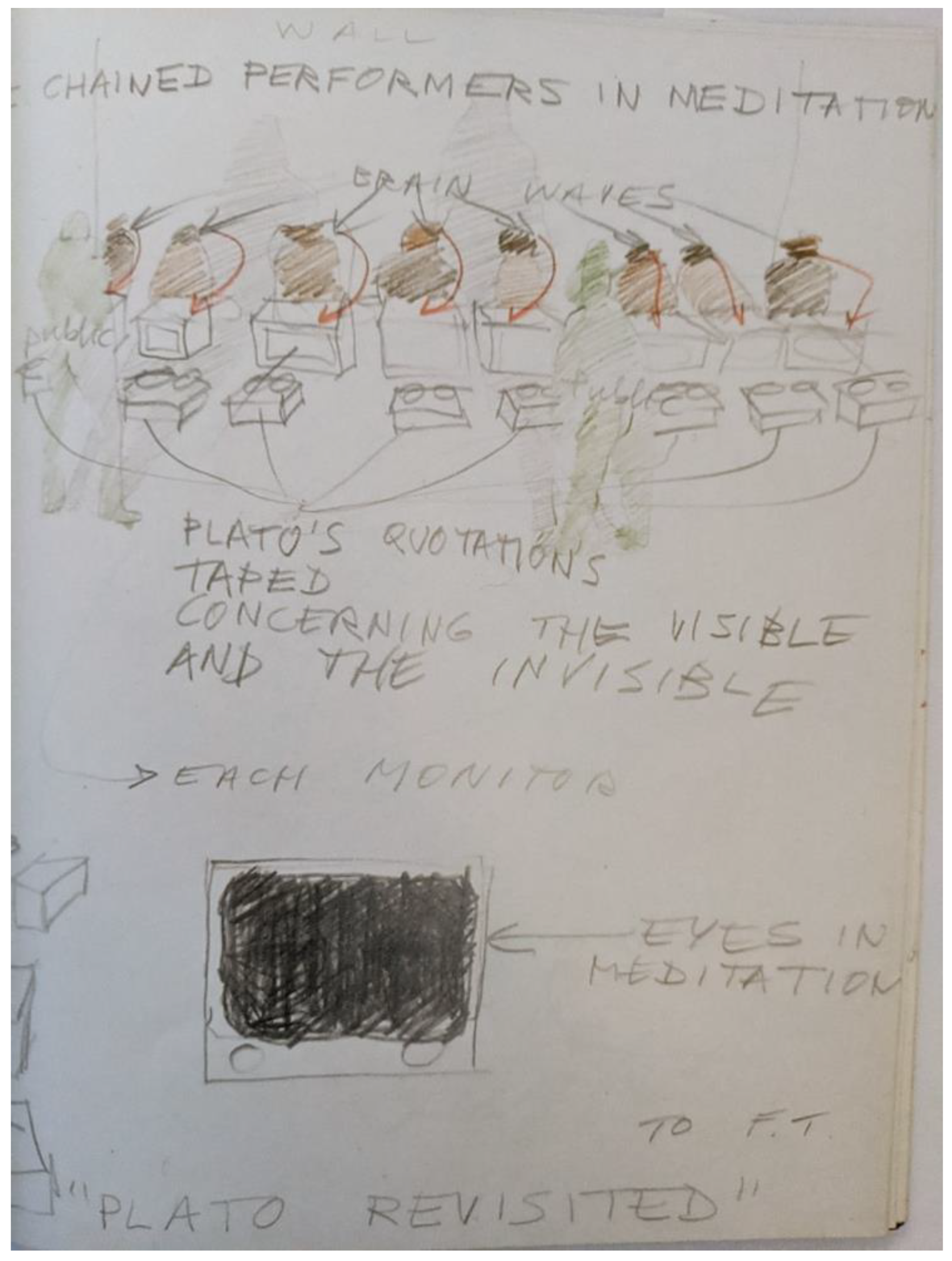

Theaetetus, and beyond outlining Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, they concerned “the visible and invisible”, as Downey described in an earlier notebook sketch of the installation [

Figure 2]. Downey would later publish the excerpts in an accompanying article also titled “Plato Now” in the “Video and Environment” issue of

Radical Software from the same year. If the sensors could not detect alpha-level brain activity in a given performer, no excerpts would play.

Located in front of each performer, situated just before the wall they faced, was a closed-circuit video camera (another nine in all and one per performer) that fed their close-ups to the monitors located behind them. Spectators could enter the installation and make their way across the room to watch the screens—a mediated but real-time glimpse of those whose backs were turned towards them. In so doing, the spectators’ figures were caught by the spotlight. Looming forms—some barely there and evaporating into the concentrated field of light, and others marking clear outlines—swayed across the wall the performers faced. Not that they could see this: by all accounts, the performers’ eyes were closed shut in meditative concentration [

Figure 3]. For them the activity of the room, indexed by an energetic play of light and dark, was invisible.

This initial invisibility gestures towards a whole series of invisible connections that are not accessible through the account of

Plato Now just given—of what it might have been like to be there on either of those two early January evenings in 1973. To gain a closer look at the invisible underside of

Plato Now, we can look at a drawing Downey completed in 1972, also titled

Plato Now, that visualizes the activity of the installation in diagrammatic fashion [

Figure 4] It is a close depiction of what the installation looked like once exhibited, with the addition of labels detailing its key components, and a series of curving arrows linking them all together. These arrows begin to make visible the invisible connections of

Plato Now.

The setting of the drawing is an unadorned room. Downey hints at its darkness through an all-over striation of incredibly fine, penciled lines running from top to bottom, only interrupted by the figures and the spotlight’s cone of light. The spotlight itself is represented by a small yellow bullseye on the drawing’s far right side. Beside it are two androgynous, grey figures labeled as the “public”, or the installation’s spectators. From the word “public” starts a red, colored-pencil arrow that gently curves towards the opposite side of the space to meet the phrase “shadows of the public”, next to drawings of exactly that. This is our first hint at the significance of the shadows for Downey. At the end of that phrase continues the red arrow into an S curve that lands at the beginning of another line of text: “performers brains producing alpha waves”. Right beneath this line, situated in a slight diagonal, are each of the nine performers. Their headphones and neuronal sensors are hinted at by tangles of wires and a nondescript box that is labeled “prerecorded quotations from Plato’s dialogues”. The red arrow continues through the head of the first performer, beyond the tangle of wires and audio box, and into the first of nine monitors. Their screens are not drawn, but rather depicted through collage, using what appear to be small cut-outs of faces from a magazine. The arrow moves past the first monitor and lands at the first word of “images of performers faces in meditation”. From the end of that text, the arrow makes its way back across the space to the second of the figures labeled “public”.

A closed circuit is created, linking together the installation’s spectators, their shadows, the performers, their “brains”, explicitly, images of their faces, and all the technologies mediating in between. A second, much shorter circuit emphasizes the technological component by starting from the second performer, coursing into the video camera drawn in front them, through the video deck (both of which are labeled), and finally out into another monitor, where it, too, finishes its path with the public. While this particular drawing stands alone as its own artwork, Downey completed preparatory sketches for the installation of Plato Now that highlight the same entities and relations. These, too, feature an explicitly labeled public, shadows, brainwaves, images of faces in meditation, video cameras, monitors, sensors, and a series of arrows indicating the meaningful connections amongst them that unfolded in the exhibition of Plato Now.

To use a term that Downey and his media art contemporaries were intimately familiar with, these circuits of arrows can be understood as “feedback loops”. A feedback loop is a recursive process whereby a system receives input, processes it, and then uses that output to inform, alter, or augment future input. Feedback is one the pillars of the cybernetic lexicon (second only to “information”) and something about which Downey himself thought deeply.

3Given the year, 1973, we can specify the understanding of feedback these drawings may have relied on. By this time, cybernetics had entered its “second order” phase, or what has been called “the cybernetics of cybernetics.” In its earliest rendition, cybernetics concerned itself with closed systems—those viewed in a physically impossible, though analytically helpful, isolation from the surrounding world and those doing the viewing; second order cybernetics, at the risk of infinite regress, attempted to fold the observers of systems into its systems analyses.

4 A key term here was “participant-observer”, an acknowledgement of how even studying a system could still affect it. That cybernetics entered this second phase at nearly the same time portable video became widely available—a technology capable of literally allowing one to watch oneself watching—was not lost on Downey and other like-minded video artists, especially those affiliated with the video art magazine,

Radical Software (1970–1974).

5This context is critical when viewing the drawing and sketches above as feedback loop diagrams. From this angle, each of the different components of the installation have the capacity to affect one another in meaningful and continuous ways that determine the installation itself. What the second-order element activates—and those who are borne out by Downey’s consistent inclusion of them in the drawing and sketches—are the spectators. Rather than outside the “system” that was Plato Now, they were integral and mutable elements of it. Of course, they could (and most likely did) come and go as the exhibition went on. But even in this open-endedness there is something special. The shadows of spectators were integral for Downey, and as the spectators made their way through, those shadows would follow—they would loosen or sharpen, loom or retreat, depending on the spectators’ position vis-à-vis the spotlight. These shadows (allegorically significant as they are) are shifting traces of the “participant-observer” and play just as critical a role for the installation as the performers’ brainwaves or their video close-ups.

While this kind of cybernetically informed, participatory aesthetics was not exactly unique for the media arts of the time, framing the drawing and sketches—and, by extension, the installation—of Plato Now as a series of open-ended and ongoing feedback loops does three important things. Firstly, it conveys the action of the installation in language that was formative for media artists of this moment. Secondly, it throws into relief the lively relationality of that action; the feedback loops here circle and twist, evoking an ongoing play of connectivity. Thirdly, it demonstrates the heterogeneity of that action; it shows how these elements—in their continuous relating to one another—form a teeming collective of human (spectators and performers), technological (video cameras, monitors, sensors, headphones), energetic (light rays, shadows, and electronic signals) and architectural (the wall facing the performers becomes an activated surface integral to the whole operation) elements.

The diversity of

Plato Now’s elements, and the way in which feedback loops thread them together as a totality, is intimately readable within new materialist philosophy. A defining feature of the movement is its privileging of heterogenous collectives or “assemblages”, specifically those that dislocate the primacy of the human subject as the center of agency.

6 The work of Jane Bennett is especially instructive here. “The electrical power grid offers a good example of an assemblage”, she tells us in

Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (

Bennett 2010), since

[i]t is a material cluster of charged parts that have indeed affiliated, remaining in sufficient proximity and coordination to produce distinctive effects…And, most important for my purposes, the elements of this assemblage, while they include humans and their (social, legal, linguistic) constructions, also include some very active and powerful nonhumans: electrons, trees, wind, fire, electromagnetic field.

I appreciate Bennett’s example because of the attention it pays to energetic entities, but, more importantly, it implies an understanding of the power grid as something not entirely under the control of human actors. Those “very active and powerful nonhumans” (a couple of which also found their way into Plato Now) do not just help make the power grid possible, they generate effects within it irreducible to singular human action.

New materialist thinking like this acknowledges that human beings are always already caught up within networks, collectives, and assemblages of entities that confound distinctions between who/what is acting and being acted upon. Not only is this deemphasis of human agency a hallmark of an earlier generation of posthumanist philosophy that has been critical for the new materialisms (

van der Tuin and Dolphijn 2010), but, to circle back to the feedback loops of second-order cybernetics, posthumanism’s own critique of the human subject has important precedents in second-order cybernetic thinking (

Cary 1995;

Hayles 1999). The challenges and possibilities of hybrid feedback systems like

Plato Now have reverberated through contemporary philosophy since their inception.

As with much cybernetic rhetoric, however, what is described by feedback is a process, often at the expense of the process’ channel or substrate. Plato Now stands out not only because of the active connections that link its different elements together, but also because of the physical—and, more specifically, energetic—means by which those connections were formed and sustained. The two-dimensional constructions of Plato Now diagram what is left unseen (and unseeable) within the exhibition environment. It is not immediately clear how shadows cast upon a wall might have a meaningful effect on closed-eye performers, or how the brainwaves of those performers might be imbricated with the installation’s video equipment and reach out towards the spectators, though these interactions are what is made legible through the drawings’ and sketches’ feedback loops. I began by suggesting that Plato Now’s significance arises from the speculative relations it generates, and, while these preparatory materials visualize those relations—between brains, shadows, video cameras and their images, for example—they do not tell us what is making those relations possible. Despite all they do visualize, something remains unseen.

What allowed these connections to be obtained? What was facilitating these points of contact? What can we look to within the context of Downey’s practice to better understand how such weird links are forming and giving rise to the invisible action of the installation? These are critical questions not only because what was taking place invisibly in Plato Now is its most alluring feature. They are doubly critical because what was taking place invisibly was predicated on something Downey’s practice in 1973 was increasingly articulating: the effectual yet invisible electromagnetic energies around us.

3. Making Weird Relationality Possible, Energetically

This articulation was expressed discursively in Downey’s theory of “invisible architecture”. In 1973, the same year

Plato Now was exhibited, Downey published two essays that unpacked invisible architecture and linked it to then current debates in architecture proper, as well as more utopian visions of media ecology and cybernetics (

Figure 5).

7 In the fourth issue of the architecture magazine

On Site, he described the theory as a means for “recuperating the energy import of the universe”, “liberating art from the parameters of the Visible Spectrum” and “the way towards direct man-environment interaction” (

Downey 2019b, p. 332). In

Radical Software that same year, he framed invisible architecture as a “process of reweaving ourselves into natural energy patterns… an attitude of total communication within which ultra-developed minds will be telepathically cellular to an electromagnetic whole”. Going all in on the possibility of telepathy, Downey suggested that “invisible architecture re-explains electronic circuitry as a bio-feedback tool in evolving the collectivity of human brains to transmit and receive (non-verbally) high frequency electromagnetic energy” (

Downey 1973b, p. 2).

However far out it may appear, there is something matter-of-fact about invisible architecture. It is premised on the idea that our environment is electromagnetic at its core and that both human thought and contemporary electronics are expressed through this energetic medium. From there, it speculates that we can intimately manipulate such a medium to unlock our telepathic potentials, transform communication and transportation systems, and put ourselves into contact with the environment at an unprecedented level. I would like to emphasize the way in which invisible architecture relies on electromagnetic energy as the media of thought and electronic signals of all kinds—that is, etymologically speaking, the intervening substance or “in-between” that makes their transmission possible.

This issue of electromagnetic energy as medium and media not only lies at the core of Plato Now’s weird relationality—and its eventual connection to new materialist philosophy—but it also gestures to the historical stakes of Downey’s larger invisible architectural program. The theory is one of many contemporary attempts to make sense of an environment whose most important elements were increasingly understood to be outside the bounds of embodied human perception. That is, the “now” of Plato Now speaks to the urgency of a specific historical condition. Later sections will clarify how, and towards what end, Platonic philosophy enters into the equation for Downey, but for now it is important to attend to this contextual frame.

Julieta González’s “From Utopia to Abdication: Juan Downey’s Architecture without Architecture” (

González 2011) helps set the historical stage of invisible architecture. Here, she explains how the theory emerged as part of a vision

of the world from the perspective of the subatomic; the technological revolutions of the ‘second machine age’ were formulated on the basis of miniaturization, micro-systems, and circuits. We begin to understand Downey’s precise notion of the invisible through his heightened awareness of the fact that the future lay in the ‘micro’…

(p. 65)

What is left implicit in González’s explanation here is the presence of electromagnetic energy as the animating but invisible force behind the “subatomic”, “circuits”, and the “micro”. She emphasizes the hardware of the “second machine age”, and this was extremely important for Downey, but the energy that powered that hardware was equally so. Indeed, that energy borders on metonymy with his “notion of the invisible”.

Downey certainly was not alone in thinking electromagnetism, electronics, and invisibility together. Some of the most prominent counterculture thinkers did so as well. Take, for example, Marshall

McLuhan’s (

1967) suggestion that invisibility “is another mysterious feature about the new and potent electronic environment we now live in. The really total and saturating environments are invisible. The ones we notice are quite fragmentary and insignificant compared to the ones we don’t see” (

McLuhan 1967, p. 164). Three years later, R. Buckminster Fuller put a point on this condition in his own, inimitable way. “More than 99.9 percent of all the physical and metaphysical events” central to humans’ continued habitation of the planet, Fuller suggested, “transpire within the vast non-sensorial reaches of the electromagnetic spectrum. The main difference between all our yesterdays and today is that man is now intellectually apprehending and usefully employing a large number of those 99.9 percent invisible energetic events” (

Fuller 1970, p. 165). Invisible architecture was, no doubt, part of Fuller’s “today”.

There was a cybernetic element to invisible architecture as well. In linking brain signals with electronic signals, Downey engaged the analogical thinking that made cybernetics such a powerfully descriptive discourse during the postwar era. Remember the feedback diagrams of the previous section. What made feedback such a compelling concept was its nearly limitless ability to describe similar processes happening in potentially (and often profoundly) dissimilar things. In an analogy dripping with unintentional Cold War irony, one contemporary author analogized a man finding his way to “the shops” to a guided missile determining its flightpath: both are engaged in “error correction”, a kind of goal-oriented feedback (

Apter 1969, p. 260). Cybernetics is processual, since it is only at the level of process that such differently embodied things could be described by the same terms. Another clear example of this is cyberneticists Warren McColluch and Walter Pitts’ famous formulation of neurons as logic gates (

McColluch and Pitts 1943). Video and media art historian Ina Blom identifies the fallacy here in terms that are pertinent to the present discussion: “neuronal functioning is seen as analogous to the on/off operations of digital switching devices, a radical simplification that only works if you ignore the physical media in which these operations take place” (

Blom 2016, p. 74).

While Downey was deeply influenced by the cybernetic worldview, his electromagnetic orientation complicates some of its foundational assumptions—precisely at the level of “media” in Blom’s sense. Invisible architecture pulls the classically cybernetic move of thinking brains and electronics together, but less so because of a shared process or isomorphism, like that above, and more so because of their shared energy. For Downey, it is their nature as and transmission through the medium of electromagnetic energy that makes them the building blocks of invisible architecture.

Invisible architecture began as a historically grounded attempt to make sense of a world increasingly defined by invisible forces brought to attention by the contemporary media technical milieu. Here, it is how the elements of Plato Now were linked together. With the development of this theory, Downey constellated electromagnetic energy, thoughts, contemporary electronics, and telepathy into one speculative frame—the frame that made the weird relationality of Plato Now possible. This constellation became even more critical for Downey in the following years.

In 1977, after time spent in the Amazon living with a community of Yanomami, Downey wrote “Architecture, Video, Telepathy: A Communication’s Utopia”.

8 It is a far-ranging text (from which this article borrows its title) that touches on everything from the building methods of the Indigenous cultures of the Americas, contemporary television, to the death of Salvador Allende. For our purposes, its claims about the cosmic pervasiveness of electromagnetic energy in relation to thinking and video are especially noteworthy. “The whole universe shares its electromagnetic nature with Video and Thought,” Downey claimed; [t]he process of thinking, regardless of its artificiality (computers) or naturality (brains) is also electromagnetic signals” (

Downey 2019a, p. 341). For him, electromagnetism, was a “radiant nature… commonly shared by thoughts, artificial intelligence, video, and it accounts for the life itself of the universe we inhabit” (

Downey 2019a, p. 343). Video is repeatedly singled out here because its “physical essence… is electromagnetic. The transformation of energy into a flow of electrons and back again to visible electromagnetic waves is due to the Photoelectric Effect. Light as it strikes certain metal chips particles off into a river of electricity” from which the video image surfaces (

Downey 2019a, p. 341). These claims push even further Downey’s earlier insistence on the closeness of thought and contemporary electronics by virtue of their shared electromagnetic medium, though here that medium is elevated to “account for the life itself of the universe we inhabit”.

It is on these grounds that I contend electromagnetic energy is the literal media of the strange relations of Plato Now. When looking at all that Downey said in this context, it seems as though the one thing that could mediate between the installation’s different entities—from shadows, to brains, to video cameras—would be electromagnetism. And, if the connections between, say, brains and shadows require a telepathic connection (a possibility Downey fully accepted), then the invisible fields of electromagnetic energy would carry those connections along. Plainly put, electromagnetism mediates, and thus makes possible, the weird relationality of Plato Now.

By continually referring to electromagnetic energy here as “media”, I am insisting on taking seriously its material (if, again, profoundly speculative) role in making the installation what it was. After all, in art history, media means the physical stuff that composes an artwork. It is challenging to think energy in such tangible terms, but I believe that is specifically something Downey’s practice encourages us to do. Moreover, it is something that partially anticipates the lively renditions of matter so important to new materialist philosophers.

What cannot be forgotten here is the fact that Downey was making these invisibly energetic claims in the dramatic guise of the Platonic myth—Plato Now was a restaging of the Allegory of the Cave. It is critical that we attend to the specifics of this allegory and the philosophical idealism it puts forth, so as to better understand the energetically enhanced revision Downey offered. The next section will place Plato Now in its proper philosophical setting.

4. Plato Then

There exists, first, the unchanging form entering no combination, but visible and imperceptible by any sense the object of thought: second, that which resembles it, but is sensible and has come into existence, is in constant motion, comes into existence in and vanishes from a particular place, and is apprehended by opinion with the aid of sensation.

This is the text of one of the nine prerecorded audio excerpts of Plato’s Dialogues that would have played through a performer’s headphones during the duration of Plato Now if their alpha-wave detector registered that specific level of brain activity associated with meditative concentration. A notebook sketch of installation described the excerpts broadly as “concerning the visible and invisible;” they included a description of the Allegory’s titular cave, bits of relevant Socratic back-and-forth, and more specific philosophical claims like the one above. The excerpts relayed (upon being heard, something not guaranteed) to the performers the outlines of the allegory their performance, and the installation generally, was revising.

Plato introduces the Allegory of the Cave via Socrates in The Republic—a key passage that Downey includes amongst the excerpts just mentioned. In the allegory there exists a cave with a single exit to the outside. Within the cave and down a winding path are trapped prisoners, their necks chained to a wall so tightly their vision is locked forward. This wall rises upwards to conceal a walkway just behind it and, just behind that, a great fire. Unchained individuals move along this walkway holding up inanimate objects like statues, chairs, and vases while their bodies are concealed. The great fire casts the shadows of these lifeless objects against a far wall facing the prisoners, and the prisoners believe these shadows to be the true contents of reality.

Eventually, a prisoner escapes. Upon making his way into the light of day he is blinded, but eventually realizes what he saw in the cave were just illusions; real objects can only be truly known outside of the cave. He attempts to return to rescue his chained comrades, but having adjusted to sunlight he stumbles through the cave’s darkness. He appears blinded to them. The remaining prisoners conclude that to exit the cave is to bring great harm upon themselves and so they stay, never glimpsing the light.

Plato uses the Allegory of the Cave to present his Theory of Forms and the basics of Platonic Idealism. Platonic Idealism instantiates an inflexible distinction between conceptual forms and the sense data that derive from them. A hierarchy is formed with ideal forms at its apex, secured within the realm of the mind, and positioned over and above their perceptual images. “In very general terms”, as philosopher Gilles Deleuze puts it, “the motive for [Plato’s] theory of Ideas is to be sought in the direction of a will to select, to sort out. It is a matter of drawing differences, of distinguishing between the ‘thing’ itself and its images” (

Deleuze 1983, p. 45). The Allegory of the Cave illustrates this hierarchical difference-making in architectural terms. The physical separation of the darkened cave interior and its illuminated exterior maps the idealist distinction between perceptual reality and a superior cognitive domain. That the shadows in the cave are all that is seeable, and that they are cast by inanimate objects, doubly serves to insist on the duplicitous nature of sense perception. The real object, the Form, exists only within the space of the mind, outside the cave, as it were, and inaccessible to the senses.

These are the contours of Plato’s cave and the idealist philosophy growing within it like some rigid stalagmite. The key questions now are: what does Downey’s cave do differently and what theoretical implications do those differences engender? Plato is making an argument about the nature of reality and how we come to grasp it—there is little reason to doubt Downey’s interest in the same. Between the title of the installation, the content of its audio recordings, and a spatial configuration where its performers face a wall filled with shadows, the site of Plato Now’s intervention is clear. Doing justice to that intervention means reading it amongst the same ontological and epistemological registers as its site. In effect, something like a comparative reading can be made between Plato then and Plato Now to not only clarify the differences between one version of the cave and the other, but to articulate the philosophical insights Downey affords us by instantiating those differences. This is the aim of the next section.

5. Plato Now

The first difference between Plato Now and its source material is obvious but impactful. In Downey’s version, there is no exterior to the cave—there is nothing other than a darkened interior. The architectural division so integral to the logic of Plato’s allegory was eliminated. This may have been due to a limited amount of available space within the Everson Museum of Art’s sculpture court, but in none of the preparatory materials for Downey’s installation is anything like an “outside” to the cave imagined.

Does this mean Downey meant to do away with the ideal space of the mind represented by the original cave’s exterior? If so, it would follow that this version of Plato for now presented only an empirical space of sense perception, thereby negating a world of ideal forms. And while this may be, the sheer number of invisibilities within this installation would suggest that, for Downey, that which only and availably meets the senses—as the shadows meet the prisoners’ vision—cannot quite account for everything here. Perhaps Downey did not negate the exterior at all, but rather folded it within the interior.

This would be a topological twist intimately readable within the

Radical Software video art scene and postminimalist art practices more generally (

De Bryun 2006;

Ryan et al. 2011). As Paul Ryan, a close contemporary of Downey’s, put it in

Radical Software, “topology is a non-metric elastic geometry. It is concerned with transformations of shapes and properties such as nearness, inside and outside” (

Ryan 1971, p. 1). In the magazine, one could even find a tutorial on how to turn a sock or stocking into a DIY topology lesson (

Brodey 1972, p. 4). More mundanely, topology is a branch of mathematics that describes the deformation of surfaces. The mobius strip is a classic topological figure, one whose “inside” and “outside” are indeterminate (you can make your own by taking a strip of paper, twisting it once, and taping its ends together). Topology was especially compelling for early video artists, not just because they found themselves wrestling with loops of magnetic tape all day, but also because they were constantly turning the camera on themselves in ways that grounded topological insides and outsides amongst the principles of cybernetic feedback. More relevantly, Downey himself framed invisible architecture as creating the possibility for “interior space, exterior space, and separating frontier [to] become one integral,” a topological aim if ever there was one (

Downey 2019b, p. 332).

Given the closeness of Plato Now to invisible architecture, the idea that Downey sought to fold the “exterior” space of the mind within the “interior” of sensual reality tracks. Other elements of the installation suggest these two spaces were indeed fused into intimate contact.

The first trace of this fusion is perhaps its most elegant: the role shadows play in Plato Now, an element explicitly labeled in nearly all the installation’s preparatory materials. In Plato’s original, the shadows upon the cave wall were always cast by inanimate objects. This inanimacy emphasized the unreality of what is given to sense. The prisoners were not just seeing shadows, mere traces of presence, those were the shadows of literal fabrications: chairs, vases, statues, etc. Only upon exiting the cave into the light of the mind would the escapee glimpse real, living things. Yet, in Downey’s re-imagining, the shadows are predominantly cast by living things: the performers and spectators. Keeping in mind the mechanics of the original allegory, Downey imbues the contents of perception inside the cave with a literal liveliness reserved only for what resides outside the cave. Perception and its objects, then, if we follow Downey’s lead, are afforded an agency Plato was unwilling to recognize.

Such agency is especially readable within new materialist thinking. One of its defining features is the power afforded to matter of all kinds. Rather than the passive and inert substance it had been regarded within Western philosophy—no doubt owing, in part, to the influence of Plato’s strong idealism—the new materialisms take a much different track. As Diana Coole asks, summing up well this shift in understanding, “is it not possible to imagine matter quite differently: as perhaps a lively materiality that is self-transformative and already saturated with the agentic capacities and existential significance that are typically located in a separate, ideal, and subjective realm?” (

Coole and Frost 2010, p. 92). While Downey is not nearly as explicit, his rewiring of the circuits of the allegory do indeed give sensual—and, by implication, material—entities a power to affect they were denied in the original. This is all the more so true given that the shadows were intended to activate something in the meditators, whether they could be seen or not.

In moving from the shadows to meditators, I am following the feedback loop depicted in the 1972 drawing of Plato Now, where a bright red colored-pencil line curves from “the shadows of the public” and lands upon the first of nine performers—or, more accurately, “performers brains producing alpha waves”. Their serenity in documentary photographs certainly evokes something other than the destitution of cavernous enchainment, and the instruction for them to meditate is critical. When one thinks of meditation, it is easy to think of something practiced in silence and solitude, a trained, inward retreat to the space of the mind. Downey, topologically so, flips this interiority inside out.

American neuroscientist James H. Austin has written extensively on the relations between the science of the mind and meditative practices in his

Zen and the Brain: Towards and Understanding of Meditation and Consciousness (

Austin 1999). Relevantly, a key feature of

kensho, or reaching Zen enlightenment, provides a different understanding of meditation’s purpose than mental self-containment. Quoting Zen master Katsuki Sekida, Austin writes that

kensho, in part, defines the realization that “you and the external objects of the world are now unified. It is true that they are located outside you, but you and they interpenetrate each other… there is no special resistance between you and them” (p. 542). This description of meditation’s end-goal should strike the reader as deeply contradictory to how Plato saw the interaction between mind and world. While Zen meditation is just one practice amongst many others, it is noteworthy that it seeks not to wall off the world from the concentrated mind, but rather strives to find that point where the two might recognize their “interpenetration”, or, to use a relevant term, their

entanglement.

This idea that there is no “special resistance” between the mind and world is another feature of the installation readable within new materialist philosophy. A hallmark of this thinking is its decentering of the human subject as a center of agency and meaning in the world; we have seen this articulated already through the heterogenous assemblages of Bennett, and the lively rendition of matter given by

Coole (

2010). Yet another way to enact this decentering is by framing meaning—as the seemingly exclusive purview of (the human) mind—and matter as ontologically co-constitutive.

The key thinker here is theoretical physicist-turned-philosopher, Karen Barad. Barad has developed a far-reaching framework called agential realism, which is unfolded most completely in

Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (

Barad 2007). The very first words of the book’s introduction point the way: “Matter and meaning are not separate elements. They are inextricably fused together, and no event, no matter how energetic, can tear them asunder” (

Barad 2007, p. 3). More specifically, by recourse to Niels Bohr’s “philosophy-physics” Barad argues—often by poetically playing on the dual sense of

matter—that meaning and materiality are always already productive of one another. The discursive constructions we use to understand the world—like physics or biology—only come into being through an intimate “intra-action” with matter of all kinds, and vice versa.

10 This implies that the mind cannot preexist the material domain, rather their mutual entanglement makes both ontologically possible.

While it might seem like a stretch to link Barad’s insights back to the act of meditation in

Plato Now, there is a congruence. To be clear, I am not claiming that Downey or any other performer in

Plato Now reached enlightenment during the exhibition. Nonetheless, it is possible Downey was working with an understanding of meditation like that given above.

11 In this context, Downey’s decision to make meditation the key performative act in

Plato Now is significant as a more practical means of approaching the kind of entanglement Barad champions, and yet another attempt to undermine a Platonic hierarchization of thought and sense, mind and world.

The neuronal sensors, or “alpha wave detectors”, do something similar. That they would trigger the playback of the excerpt recordings in performers’ headphones upon detecting the level of brain activity associated with mediative concentration speaks to another instance of meaningful contact between mind and world—exterior cave and interior cave, as it were. This renders the brain as an active, energetic entity with the mediated capacity to reach out and transform the material conditions of the installation (triggering audio playback or not). Realizing the brain’s affectivity through electronic signals should be read through Downey’s insistence on the possibility of telepathy, where non-verbal communicative acts are enabled through electromagnetic means. This was, after all, a key feature of invisible architecture.

Thus, what is crucial about Downey’s “becoming-signaletic” of the brain is not just its extended capacities to affect the operations of the installation, but how that relies on the brain’s explicit entanglement within the energetic medium that animated the rest of the installation’s components, namely, the audio equipment, the closed-circuit video systems, and the shadow-casting spotlight. These, too, were powered by flows of electromagnetic signals, making the totality of the Plato Now a crisscrossing of energy between interior brain states, electronic sound, video cameras, monitors, their images, and all the rays of light in between. Here, again, we have that series of invisible flows made visible in the installation’s preparatory drawings, now rendered in their electromagnetic media. Once this set of weird, energetically-enabled relations is situated within the architecture of Downey’s allegorical reimagining, Plato Now’s philosophic vision comes through.

Downey took the exterior and interior of Plato’s Cave and fused them together in a wash of electromagnetic waves. The idealist distinction of the original allegory was dissolved in a play of energetic signals looping between brains, bodies, video cameras, monitors, audio, images, and shadows. Plato Now’s allegorical blending of mental and perceptual worlds is embodied in this electromagnetic meshwork—that strange series of entanglements which make the work so compelling, if initially opaque.

What this meshwork gives us, once scaled up to the ontological and epistemological registers of the original allegory, is a deeply energetic and relational vision of what the world is and how we come to grasp it. At the core of that vision is electromagnetism’s capacity for generating strange, alluring connections—for bringing different kinds of entities, objects, and ideas into contact with one another and doing so in unexpected ways. Plato Now is a testament to this weird connection-making, outfitted in the guise of philosophic allegory. It suggests that we are always already immersed in an energetic medium, and, whether by thinking or feeling it—that is, whether from outside the cave or within it—we relate through it and to it. What follows, and is obtained in the literal make-up of the installation, is a radical expansion of the possible relations in which different entities can find themselves. The seeming strangeness of the telepathic brain, shadows, and video connections of Plato Now gestures towards the new, however invisible, realities that emerge when idealist hierarchies are discarded in favor of the energetically lively and relationally open.

6. Conclusions

Throughout this article, I have emphasized the speculative nature of what Downey offered through Plato Now. I have insisted that there is something “weird” about the connections that made up the installation and gave as much attention as the artist himself did to their telepathic possibilities. Whether or not those connections were obtained, and a series of telepathic mind melds took place, is not what I am going to discuss here. I will leave that as an open question.

Much like the theory of invisible architecture that preceded Plato Now and helped give it shape, the wild speculative turns the installation took cloaked a matter-of-fact reality. The weirdness of its relations bely a serious intuition about the nature of experience during the height of the Information Age. We do not have to accept Downey’s telepathic insistence—and it is something most art historians choose not to engage with when thinking about his practice—but its premise requires careful consideration.

At the base of both invisible architecture and Plato Now is the correct assumption that our world is suffused by a wash of electromagnetic fields, waves, and signals. While we cannot see them—and can only feel them in more extreme instances—we constantly create and communicate meaning through them.

The Information Age is called that because of the transformative effects the concept of information, and information theory and cybernetics, had on our media technical and discursive milieu (

Kline 2015). To champion information meant to privilege content over its channel. As Norbert Wiener said, “information is information, not matter or energy” (

Wiener 1948, p. 132). What this ignores—as most cybernetic thinking did—is that, for information to ever inform, it needs to be transmitted, and that transmission, however it may proceed, needs matter and energy.

12 The primary energy of the Information Age was—and all telecommunications and electronics today still require—electromagnetism.

On the one hand, it is easy to understand why information had such a powerfully dematerializing hold over the moment. So much information was, and is, transmitted as electromagnetic signals, and these simply exist outside our embodied capacity to sense them. Take physicist Richard Feynman as quoted in Douglas Kahn’s comprehensive art and media history of electromagnetism,

Earth Sound Earth Signal: Energies and Earth Magnitude in the Arts (

Kahn 2013). “In this space”, the room where Feynman was being interviewed by the BBC at the time,

There is not only my vision of you, but information from Moscow Radio that’s being broadcasted at the present moment and the seeing of somebody from Peru. All the radio waves are just the same kind of waves only longer waves. And then the radar from the airplane, which is looking at the ground trying to figure out where it is, is coming through this room at the same time. Plus the x-rays, and cosmic rays, and all these other things, the same kind of waves, exactly the same waves, but shorter, faster, or longer, slower, exactly the same thing.

(p. 10)

That “same thing” is electromagnetic energy. And the only thing more mind-bending than its ubiquity, is our inability to ever really grasp it. So, it is no wonder that the more information was carried along by electromagnetic means, the easier it became to imagine it purely as information and “not” as Weiner had it, “matter or energy”.

What makes Downey such an important artist for his time, and for us today, is his recognition of the energetic underside of the Information Age. Invisible architecture and Plato Now, for all their weird and wild takes, simply rest on the idea that we exist in an electromagnetic medium. We are constantly immersed in its field and just because it seems immaterial does not mean that it is.

This is why I have, throughout the entirety of this article, been stressing that electromagnetic energy is the media of the strange connections of Plato Now. It is a rhetorical move which emphasizes the ways in which electromagnetic energy helped enable and sustain the action of the installation, as much as its video cameras or neuronal sensors did. This is meant, on the one hand, to encourage readers to take seriously the energy’s place as an integral and constitutive component of the artwork. On the other, it is meant to signal something special about the media arts in relation to the new materialisms.

The same vibrant and shimmering power the new materialists have discovered (or, more accurately, recovered) in plain, everyday matter, their elevation of matter to something capable of profoundly moving or decentering us, its capacity to transform experience in unexpected ways—all this feels very much like what Downey felt in electromagnetic energy. What he said about video, that its “physical essence is… electromagnetic”, can be said about the media arts tout court. And while all matter (and art) has an energetic component, down to the subatomic level, the media arts are literally turned on by it and radiate it outward in ways tied inextricably to their nature as media arts. Downey recognized this and made it operative for his practice—us media art historians should too.

After all, we are still immersed in the electromagnetic medium Plato Now sought to disclose and enhance. If anything, it has only become more pervasive. Alongside all our scientific and technical means for making sense of that medium, the media arts are indispensable.