Abstract

The Dingling Mausoleum was built as the afterlife abode of Emperor Shenzong of the Ming Dynasty (r. 1573–1620) and his two wives. Among the thousands of burial goods excavated from the site are two embroidered silk jackets that belonged to Imperial Honored Consort Wang, often referred to as Empress Dowager Xiaojing. With their physical proximity to the deceased body, sophisticated craftsmanship, and unusually festive motifs of one hundred playing boys, the jackets are both fascinating and puzzling. Through closely attending to the visual and material aspects of the jackets, and considering them together with the funerary context and historical circumstances, this paper suggests that these jackets were designed not only to serve the deceased in her afterlife, but also to maintain and strengthen her connection with her offspring in the living world as a means of power assertion and political protection.

1. Introduction

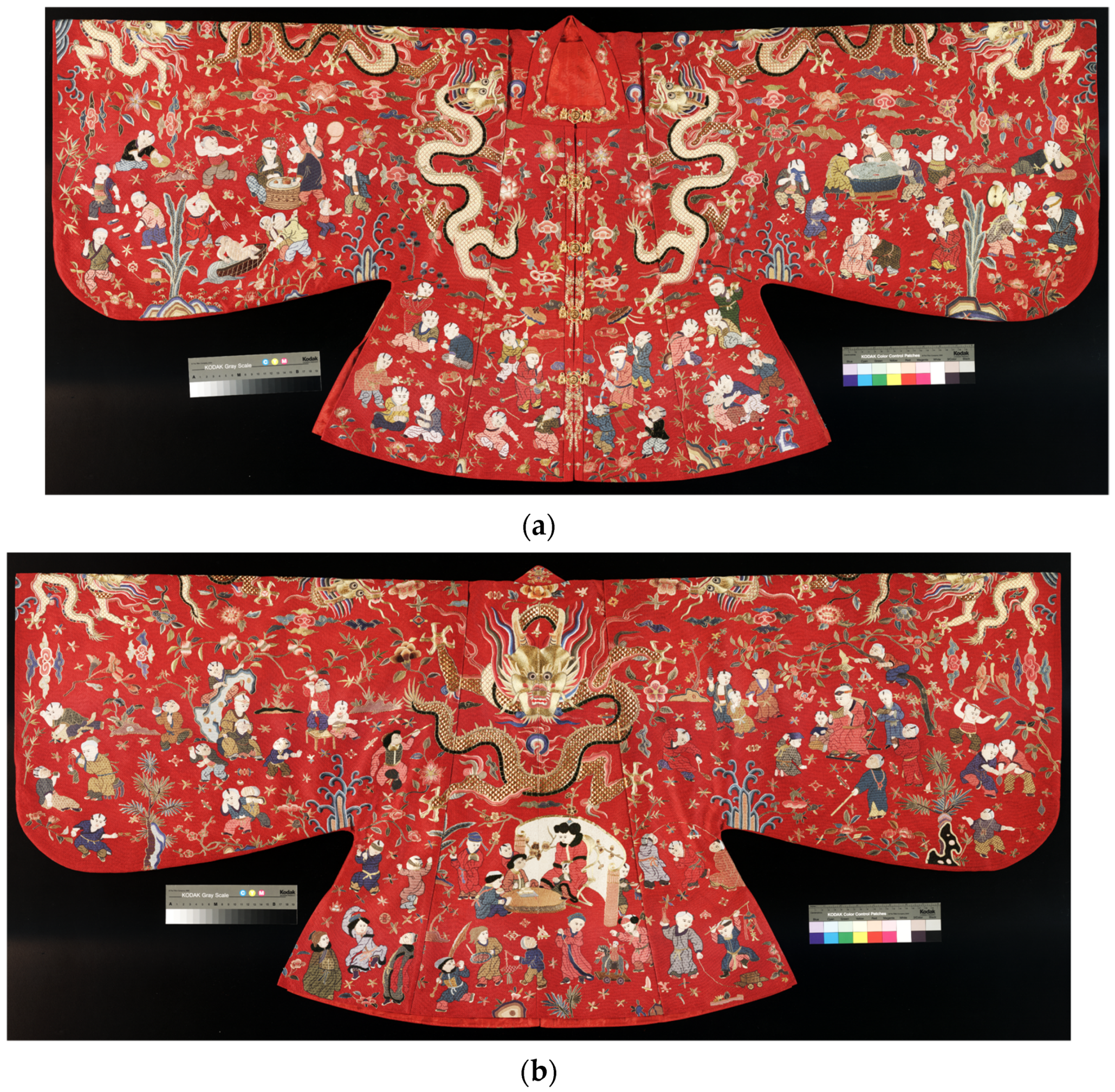

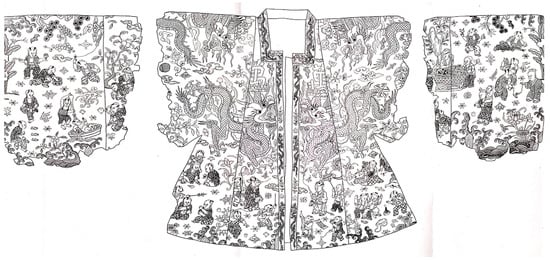

In the year 1957 outside present-day Beijing, the city’s archaeological team opened the underground palace of Dingling 定陵 (The Dingling Mausoleum). The site remains the only excavated imperial burial of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) to date (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990; Yang and Yue 1997). Upon entering the chambers, the archaeologists found the bodies of Emperor Shenzong 神宗 (r. 1573–1620, the Wanli 萬曆 Emperor), Empress Xiaoduan 孝端 (1564–1620), and a concubine with the posthumous title of Empress Dowager Xiaojing 孝靖 (d. 1611).1 Buried with them were opulent tomb furnishings to supply a comfortable afterlife. Among these burial goods were two embroidered silk jackets in Xiaojing’s coffin (Figure 1). Both of the objects bear the lively images of one hundred playing boys, giving them the names of “hundred-boys jackets” (baizi yi 百子衣) often used in scholarly and popular literature. With their physical proximity to the deceased body, extremely sophisticated craftsmanship, and unusually festive color and design for a burial context, the jackets are fascinating and perplexing.

Figure 1.

Front panel of one of the two hundred-boys jackets on the corpse of Xiaojing, Ming Dynasty, Wanli period, 1573–1620. Original. Embroidered silk. Excavated from Dingling. Capital Museum, Beijing. After (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1989, plate 三九/39–14).

As the jackets’ most unique and eye-catching feature, the exquisite embroideries of “one hundred playing boys” (baizi 百子) have received the most scholarly attention. One of the most comprehensive treatments is Terese Tse Bartholomew’s essay in Children in Chinese Art, where the author traces the visual history and development of baizi iconography from the Song Dynasty (960–1279) to the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) (Bartholomew 2002, pp. 57–83). In this paper, Xiaojing’s two jackets are used to demonstrate the popularity of the hundred-boys theme across various decorative mediums during the Wanli period. While pointing out the main function of the baizi motifs as auspicious symbols expressing the wish for numerous noble offspring, Bartholomew also sees the elaborate images on the jackets as historical documentation of games and toys in late Imperial China (Bartholomew 2002, pp. 63–68). Focusing exclusively on the images of toys on baizi jackets, Chinese toy specialist Wang Lianhai has identified and traced the origins of the toys that appear on the jackets (Wang 2004, pp. 107–17). A decade after these contributions, Yang Zhishui’s study expanded on the cultural history of the hundred-boys theme by means of including textual and religious materials from pre-Song periods and identified a few more motifs neglected in previous studies (Yang 2014, pp. 1–38). In a recent paper, Han Shuai provides a detailed review of the iconography of the motifs on the jackets, and suggests a possible political interpretation that connects baizi images to the status of Xiaojing within the imperial hierarchy (Han 2021, pp. 124–26). Featuring a variety of complicated embroidery and weaving techniques, the jackets have also been closely examined by textile specialists and conservators (Sun 1990; Wang 2018).

In sum, these previous studies have provided valuable analysis regarding the pictorial design and craft techniques on the baizi jackets and greatly informed my reading of them. While each has the advantage of zooming in to thoroughly examine the jackets from a specific angle, the end result conceptually divides the objects into various self-contained aspects and does not analyze the jackets as whole objects within their original spatial and historical context. Consequently, we are still left with many unresolved questions, dealing particularly with the occurrence together of the jackets’ remarkable properties: if the hundred-boys motifs symbolized reproduction and familial prosperity, which are commonly found on objects for festive occasions—especially weddings, why should it appear on jackets placed in a tomb? As two of the most elaborate textile pieces from the entire underground complex, why were the baizi jackets given to Xiaojing, who was only a concubine to the emperor during her lifetime, instead of the empress? Why were these two jackets located so close to Xiaojing’s body? And if the jackets indeed had political significance, how did they function within the funerary context of Dingling?

In The Art of the Yellow Springs: Understanding Chinese Tombs, Wu Hung advocates that instead of studying funerary objects fragmentarily based on their media, we should investigate them within the tomb sphere where the artifacts, images, space, and structure are all parts of an interrelated program and are driven by a shared underlying logic that is inseparable from the political, social, and cultural situation of their time (Wu 2010, pp. 12–14; Cf. Wu 2009, pp. 21–41). Following this method, this paper considers the baizi jackets as integral parts of the burial program at Dingling, and reads them within the historical context—especially the court politics—near the end of the Ming Dynasty. This will help us further uncover the meaning and function of the jackets and deepen our understanding of the fundamental logic behind the funerary program at the site. In particular, the cases of the baizi jackets will demonstrate how political ambition, desire, and emotion can not only be expressed but also enacted through textiles within the funerary context. A careful treatment of the pictorial elements, textile techniques, and the “life” of the baizi jackets also provides us a chance to glance into the private yet political lives of imperial women and their multifaceted relationships with their husband and male offspring—an aspect of history that is not easily accessible through textual records.

Starting with an examination of the tomb space where the jackets were originally situated, this paper suggests that there were two identities of Xiaojing present in Dingling. While some tomb features present Xiaojing as the secondary consort of the emperor, others—especially the hundred-boys jackets—point to her identity as the Empress Dowager. Given the importance of the afterlife in Chinese culture, often articulated through meticulously planned tomb arrangements, it is unlikely that the identity inconsistency in the imperial burial was merely a coincidence. Rather, I will argue that it likely resulted from the specific political circumstances at the Ming court during the chaotic transitional period from Emperor Shenzong, through Emperor Guangzong光宗 (r. 1620), to Emperor Xizong熹宗 (r. 1620–1627). Against this backdrop, a close examination of the visual and material features of Xiaojing’s baizi jackets will further reveal that these objects were likely added to the burial ensemble during her second burial. They were not only intended to serve the deceased in her afterlife, but also to maintain and strengthen her connection with her living offspring as their means of power assertion and political protection.

2. Dual Identities of Xiaojing

Two identities of Xiaojing co-existed in the Dingling Mausoleum. The first is her identity as the Imperial Honored Consort Lady Wang (Huang guifei Wang Shi 皇貴妃王氏) of Emperor Shenzong. This identity can be observed through the epitaph, the placement of the coffins, and the spirit seats (shen zuo 神座) in the middle chamber. However, many burial goods allude to or even highlight Xiaojing’s identity as Empress Dowager Xiaojing (Huang taihou Xiaojing 皇太后孝靖). This includes the posthumous album (shice 謚册), the posthumous seal (shibao 謚寶), the coronets, and the baizi jackets. These two identities are inherently contradictory within the context of the imperial court. For one thing, while they may indeed belong to one woman, they can only appear sequentially in different stages of her life. And for another, with these different identities come two distinct political statuses of Xiaojing. More importantly, these statuses map Xiaojing onto different positions within the power hierarchy among the three tomb occupants. These unusual double identities of Xiaojing can only be explained through the political situation around the time of her death and burials.

The furnishing in the underground palace of Dingling points to Xiaojing’s identity as a concubine to Emperor Shenzong. This is most directly articulated in the epitaph inside Xiaojing’s coffin. Here, she is referred to as “The Graceful Respectful Peaceful Pure and Virtuous Imperial Honored Consort Wang of the Great Ming (Daming wen su duan jing chun yi huang guifei Wang Shi 大明溫肅端靜純懿皇贵妃王氏)” (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, p. 230) This title marks Xiaojing’s subordinate relationship to the other two tomb occupants. More specifically, the emperor was unquestionably the patriarch of the imperial household with absolute authority. Empress Xiaoduan—the primary wife of the emperor—was the most powerful woman not only within the imperial court, but in the entire empire. In terms of Xiaojing, although she eventually turned out to be the mother of the Heir Apparent, to refer to her with the title of Imperial Honored Consort only presents her as a higher ranked concubine. As a concubine, she was nevertheless ranked below the empress in the imperial household.2

This particular relationship among the three tomb occupants can be further observed from the placement of the coffins in the inner chamber. Here, the relationship among the three tomb occupants is presented as the husband being highest in the hierarchy, and his two wives being both hierarchically subordinate. The coffin of the emperor was placed at the center and flanked by the coffins of Xiaojing and Xiaoduan on two sides (Figure 2). While the size of the emperor’s coffin is larger than the other two, the sizes and shapes of the wives’ are almost the same (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, pp. 22–23). The central position and the larger size of the emperor’s coffin indicate his domination within the household. The comparable placements and sizes of Xiaojing and Xiaoduan’s coffins suggest the women’s comparable relationships to the emperor as his spouses. However, whereas both coffins of the emperor and the empress are made of wood from the rare and prestigious material of phoebe zhennan, the coffin of Xiaojing is made of much less expensive pinewood. This suggests the subordinated position of Xiaojing to both the emperor and the empress (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, pp. 22–23).

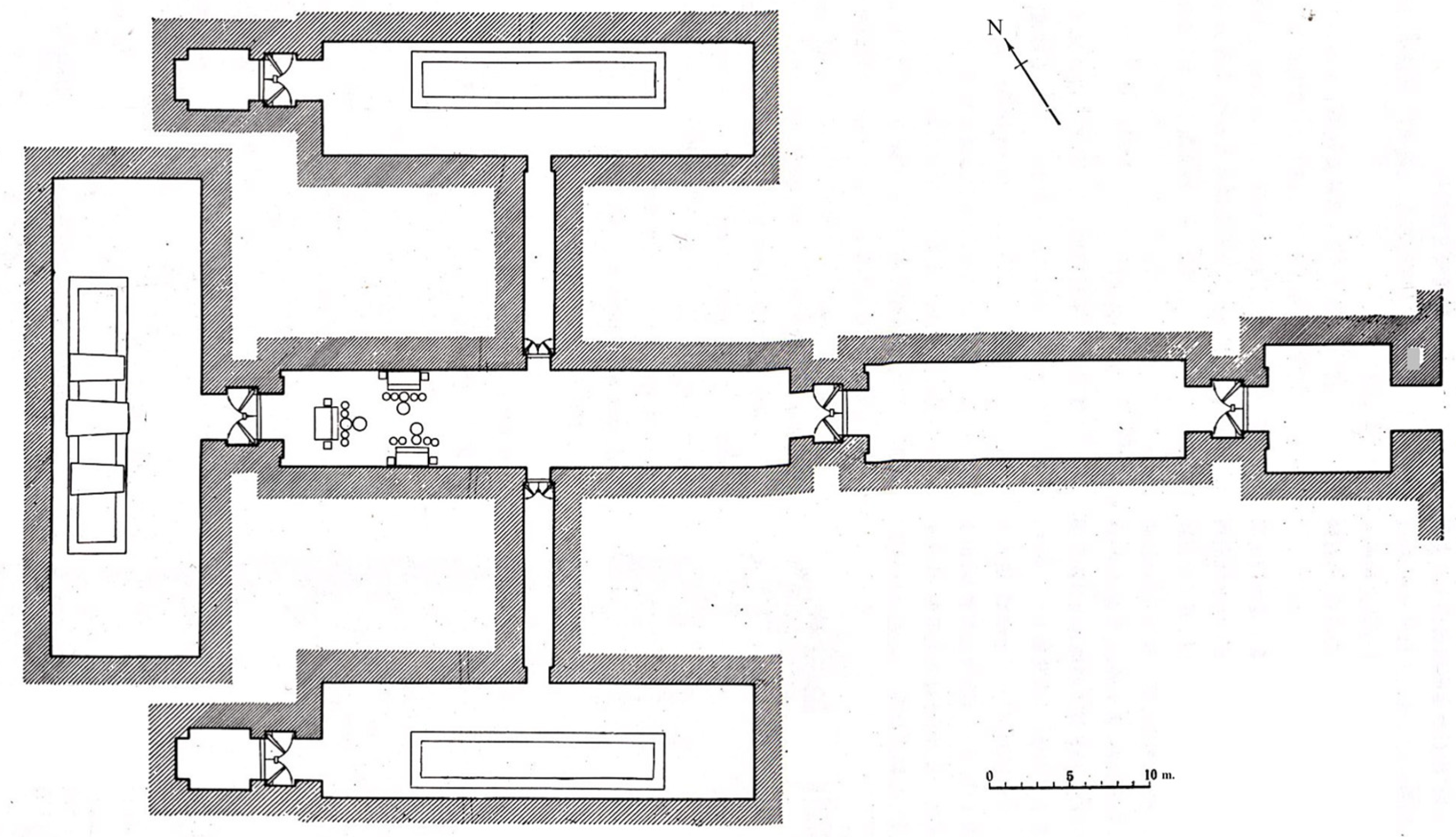

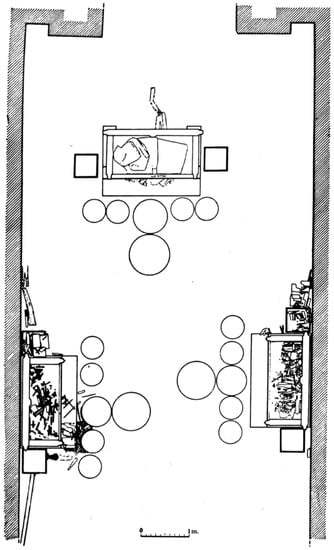

Figure 2.

The layout of the underground palace, with the coffins in the rear chamber on the far left. After (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, vol. 1, figure 12 (A)).

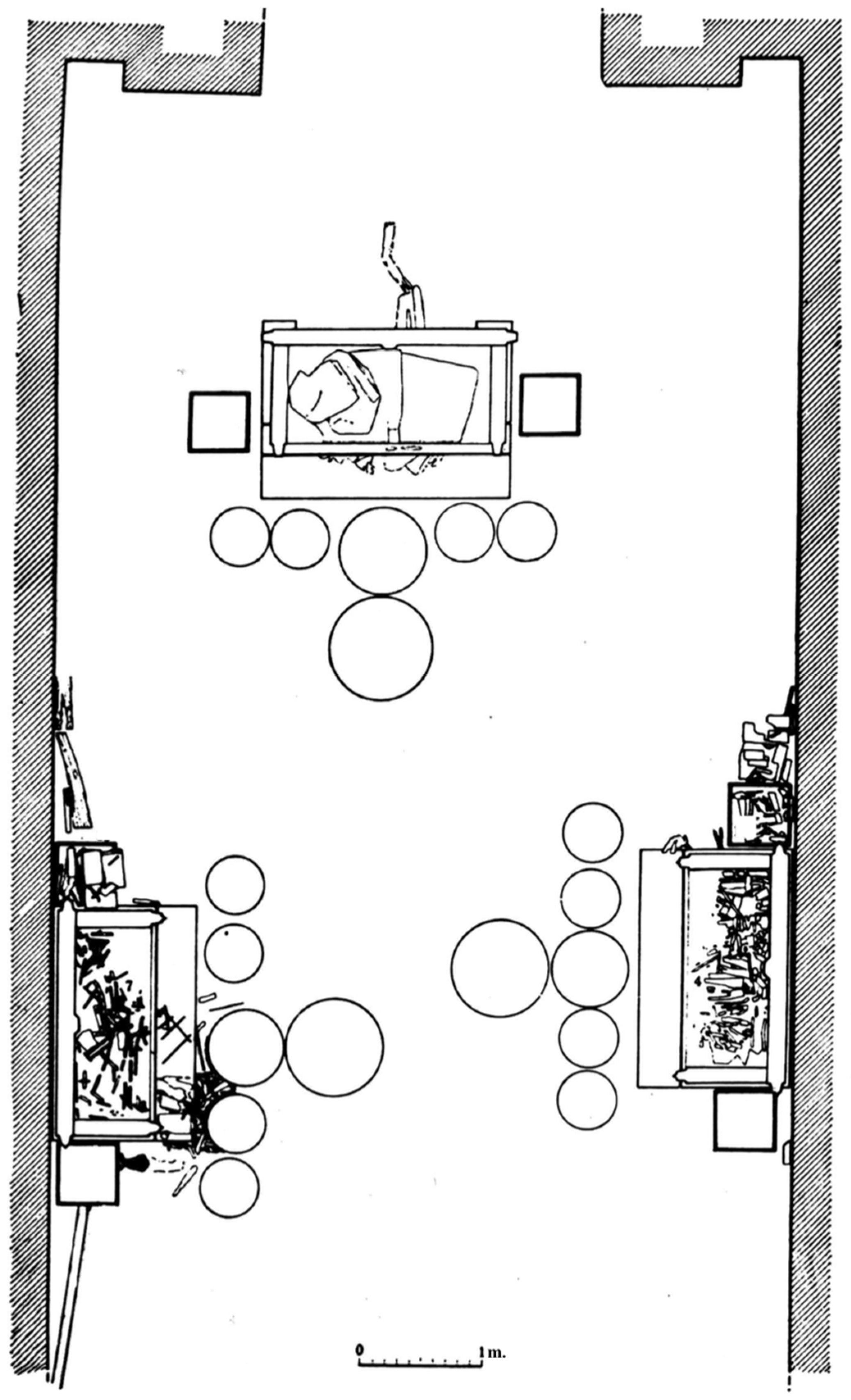

Such a power relation among the three tomb occupants can also be observed through the layout of the three spirit seats in the middle chamber (Figure 3). Setting an empty seat surrounded by sacrificial objects in tombs had been a funerary custom in China since the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). Believed to host the invisible soul of the tomb occupant, the spirit seat was a significant feature of premodern Chinese burials, and thus its placement and setup were carefully thought out (Wu 2010, p. 64). In the Dingling Mausoleum, the spirit seat of Emperor Shenzong is placed at the center among the three seatings (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, p. 19). Shenzong’s high status is signified by the seat’s large size and its position on the central axis of the tomb layout. In front of the emperor’s spirit seat is the seat of Empress Xiaoduan placed against the west wall of the chamber. It is slightly smaller than the emperor’s, thus showing Xiaoduan’s subordinate position to the emperor. The seat of Xiaojing is located on the other side facing the seat of Xiaoduan. Compared to Empress Xiaoduan’s seat, the seat of Xiaojing is farther away from the emperor’s. This difference in the physical distances between each seat to the emperor’s symbolizes the seatholders’ different political proximity to the emperor. In other words, Xiaojing was seated further away from the power center than the empress, and thus has a lower political status.

Figure 3.

Layout of the spirit seats in the middle chamber. After (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, vol. 1, figure 23).

One might expect the same hierarchy among the tomb occupants to prevail in every aspect of the burial. However, a close examination of some of the burial goods suggests that Xiaojing also possessed a higher status that surpassed that of the empress’s. The only woman who could be more privileged and powerful than the empress is the emperor-mother within the court’s political structure. Therefore, the high status of Xiaojing must be related to her identity as the Empress Dowager after her son became emperor eight years after Xiaojing’s death. The most direct pieces of evidence for this new status of Xiaojing are the wooden posthumous tablet inscribed with her official biography and the seal with her formal posthumous title. These objects had been considered two of the most important ritual objects in royal funerals since the Han Dynasty and were kept close to the coffin throughout the entire funerary rites, and later inside the tomb (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, pp. 229–30).3 In both objects, Xiaojing is referred to with the full honorific title of the “Humble Virtuous Respectful Benign Chaste and Loving Empress Dowager Xiaojing who gave birth to the sage emperor (Xiaojing wen yi jing rang zhen ci cantian yisheng huang taihou 孝靖溫懿敬讓貞慈參天胤聖皇太后)”. This title was initiated by her son Emperor Guangzong 光宗 when he assumed power in 1620. After Guangzong’s sudden death shortly after his coronation, the title was officially granted to Xiaojing by her grandson Emperor Xizong 熹宗 before the interment of her coffin into Dingling.4

The elevated status of Xiaojing as the emperor’s birth mother could also be observed through the textiles and accessories that she was buried with. In the Ming Dynasty, clothing was intimately related to one’s social status under strict codes.5 These regulations make specific requirements and restrictions on the color, pictorial motif, material, making-technique, and format of the clothing that a person was allowed to possess and wear depending on their place within the social and political hierarchy. One example that marks Xiaojing’s status is the pair of baizi jackets. Their unusual inclusion, location, and design for the tomb context, as well as their subtle emphasis on Xiaojing’s identity as the Empress Dowager, will be discussed in more detail later in this paper. For now, I will only point out that the material, technique, and design on both of the jackets are much more complex and elaborate than any other textiles found in the Dingling Mausoleum. They stand out even when compared with the already extravagant textile ensembles of the emperor and the empress. While all other textile pieces from Dingling are made of materials—often luxurious silk varieties—that are appropriate for high-level tombs or households, Xiaojing’s baizi jackets were constructed with an uncommonly complex embroidered fabric. To create this composite fabric, the silk ling 綾—a traditional Chinese twill damask with single-colored patterns was used as the base; it was then fully covered with red threads in darning stitches to create the illusion of a woven pattern (Figure 4). This resulted in a deceptively simple-looking fabric with subtly patterned textures that, in fact, was extremely labor intensive and difficult to make. Furthermore, this luxurious embroidered fabric is only used as the ground for the embroidery of dragons, children, garden settings, and auspicious symbols (Peilan Sun 1990, pp. 352–55). These lively embroideries are rendered with diverse stitching techniques with threads made from expensive materials such as gold and peacock feather.

Figure 4.

Detail of the embroidered base from a baizi jacket After (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1989, plate 61).

The complexity of Xiaojing’s political status and the multiplicity of her identities is demonstrated by the set of coronets found in the Mausoleum. Out of the four richly adorned coronets, two belonged to Empress Xiaoduan, while the others belonged to Xiaojing (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, pp. 205–6). According to Yufu zhi 輿服志, a set of official dress codes included in Ming Shi (明史 History of Ming), a coronet decorated with dragons and phoenixes was the standard formal head accessory for royal women during important ceremonies. The empress’s coronet should include exactly nine jade dragons and four golden phoenixes. The quantity, material, and composition of other motifs such as flowers and clouds on coronets for noble women of various statuses are also specified.6 None of the coronets found in Dingling corresponds to the official codes, which may suggest either a change in the regulations that the written history failed to record, or a transgression that was not uncommon during the Wanli period (Volpp 2005, pp. 145–49). Nevertheless, we might still determine the status of Xiaojing from her coronets through comparing them to those of the empress’s. One coronet of the empress has nine dragons and nine phoenixes, and the other has six dragons and three phoenixes (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, pp. 205–6). Interestingly, the designs on the two coronets of Xiaojing suggest two different hierarchical relationships between her and the empress: one of Xiaojing’s coronets is simpler than either of Xiaoduan’s, with only three dragons and two phoenixes—a coronet that is suitable for a consort ranked below the empress; but Xiaojing’s other coronet outshines both of the empress’s, with an astonishing twelve dragons and nine phoenixes (Figure 5) (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, pp. 205–6). No other woman except for the Empress Dowager would have been allowed to possess an extravagant coronet such as this one.

Figure 5.

Coronet with twelve dragons and nine phoenixes. After (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1989, plate 114).

The coexistence of contradictory identities of Xiaojing presented in Dingling was likely related to the different perceptions toward the imperial burial driven by varied personal and political interests at the court. Emperor Shenzong was not only the commissioner of Dingling, but also its designer in chief. It was obvious that Shenzong was concerned with every detail of his afterlife and final resting place. He started to prepare for the construction of his tomb by the age of twenty. In the eleventh year of Wanli (萬曆十一年, 1583), he decided to go on an inspection with his ministers to scout for the most auspicious burial location in the Tianshou Mountain 天壽山.7 After Shenzong’s numerous communications with the officials in charge of the tomb project and three on-site visits in the following year and a half, the construction finally started.8 During the four years of building, Emperor Shenzong oversaw every detail of the construction, from the construction material and layout to interior arrangements.9 With the hard work of tens of thousands of laborers, the tomb structure was finally completed in the eighteenth year of Wanli (1590).10 Before the completion date, the emperor proposed to pay a last visit to his underground palace. His request was refused by his ministers: the state had spent more than eight million taels of silver on the construction and could not afford yet another lavish imperial expedition.11

But it seems that Shenzong was most concerned about his eternal companions in the burial. The underground palace was prepared for three occupants: Shenzong himself, the barren Empress Xiaoduan, and the mother of the succeeding emperor (Hu 1989, vol. 4, pp. 26–36). Shenzong intended to save the third spot in Dingling for his favorite concubine, Honored Consort Zheng 鄭貴妃. In order to do so, he would have to elevate Consort Zheng’s status through making her son Zhu Changxun 朱常洵 (1586–1641)—Shenzong’s third oldest son—into the Heir Apparent.12 However, it was his eldest son Zhu Changluo 朱常洛 (1582–1620), born to Consort Wang (Xiaojing), that was considered to be the rightful heir by most at court. Although Emperor Shenzong found every way to postpone the investiture of Zhu Changluo and advocated for Zhu Changxun’s legitimacy, he was harshly criticized by the ministers and his own mother.13 Having given up under the enormous political pressure, in 1601, Shenzong finally named Zhu Changluo the Heir Apparent. Consequently, Xiaojing was to be buried in Dingling with the emperor and the empress. On his deathbed, Emperor Shenzong made a final attempt to name Consort Zheng the new empress, so that Zheng’s status would rise above that of Xiaojing’s and take the third spot in Dingling. His last wish was denied by the ministers.14

From this rather colorful historical narrative, we could extract two perceptions concerning the nature of the imperial burial. These two conflicting perceptions can help explain the conflicting identities of Xiaojing in Dingling. On the one hand, Dingling was seen as the eternal home for Emperor Shenzong; thus, it should be about him and his personal relations. It is therefore not surprising to us that for Shenzong, he wished to be buried with the woman he loved. The political spectacle surrounding Shenzong’s succession lasted for more than half a century. But from the textual records, it seems that it was never entirely about the emperor’s hesitation in determining an heir, but also about his desire to reunite with his favorite consort in the afterlife. Even though it was Xiaojing who ended up in the tomb for giving birth to Emperor Guangzong, when we consider her relationship to the tomb’s principal occupant, Shenzong, Xiaojing was only a less-favored concubine. On the other hand, the imperial burial was never merely a personal matter of the emperor. It was also a state affair. Following the protocols of imperial funerary practice was considered a way for an emperor to show his filial piety toward his ancestors—an essential quality in a virtuous ruler.15 Including both the empress and the mother of the successor when the empress failed to produce a male heir was a tradition already established by Emperor Yingzong (英宗, r. 1437–1449, 1457–1464).16 It would be against imperial tradition and thus harmful to the legitimacy of Emperor Shenzong and his court had he selfishly replaced Xiaojing with Consort Zheng in Dingling. According to the same logic, to bury Xiaojing alongside Emperor Shenzong to consolidate her status as the emperor mother was an important token of legitimacy for the reign of her son Zhu Changluo (Guangzong) as well as her grandson Xizong. In other words, it was Xiaojing’s connection to her offspring outside the tomb rather than to her deceased husband that earned her position in Dingling. As will be discussed in the next sections, the design and what I will call the trajectory of the baizi jackets further reveal that the world of the dead was never fully detached from the world of the living. Rather, the connection between Xiaojing and her son and grandson was sustained and emphasized through the baizi jackets at a time of crisis for the emperors in securing their throne.

3. Jackets for the Matriarch

The two baizi jackets are among the most important burial goods of Xiaojing. Their importance is first highlighted by the placement of the short baizi jacket over Xiaojing’s deceased body as the most visible layer of clothing. The repetition of a similar design on the other slightly longer jacket folded under the body inside Xiaojing’s coffin further confirms the significance of the jackets and their shared motifs. Upon excavation, the silk and embroideries were mostly intact. And although the color had largely faded, what had remained was adequate for reconstructing the original palette: on both jackets, colorful embroideries with metallic highlights were set upon bright-red grounds. On the jacket over the body, there is some minor damage to the sleeves and the front linings, and on the jacket under the body, the mid-sections of the two sleeves are missing (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, pp. 136–41). But since the general composition of the pictorial figures and the activities they engage in are almost identical on the two jackets, with only minor changes in the arrangements and designs of the dragons and auspicious ornaments, textile conservators were able to compare and infer the images and their embroidery techniques on the missing parts, and managed to make two extraordinary reconstructions of the jackets.17 The following analysis of the jackets will mainly be based on the images of these replicas. The textual descriptions in the archeological record, the photographs of the original jackets, and the line drawings will also be consulted. Since the original short jacket over Xiaojing’s body is better preserved, as a matter of accuracy and convenience, the visual analysis will mainly be focused on this jacket unless otherwise specified. With the shared design on the two jackets, many of the points made apply to both. My discussion will suggest that Xiaojing’s baizi jackets address two aspects of her posthumous status of Empress Dowager: one pertaining to its entailed political power, and the other concerning the familial connection it indicated.

Xiaojing’s high political status as an Empress Dowager is emphasized on the baizi jackets first by the visually striking dragon motifs that are embroidered with shiny golden metal threads (Figure 6a). On the jacket, two four-clawed dragons portrayed in three-quarter view are placed symmetrically on the chest, their heads facing toward the collar. Two dragons, depicted in a similar way but with five claws, are embroidered on both sides of the shoulders. On the back panel, an enlarged five-clawed dragon is placed prominently on the top center, fiercely facing the viewer (Figure 6b). Additionally, on the cuffs, two small dragons with five-clawed feet are embroidered in frontal view. The visual repetition, the iconic symmetrical compositions, and the use of the expensive gold and peacock threads speak to the importance of this motif. The dragons also appear on all sides of the jacket, making sure that the motif can be seen from every angle when being worn. As an auspicious heavenly creature linked to cosmic manifestation in Chinese religions, the dragon had been intimately related to the power of the monarchy and thus became the emblem of imperial power since ancient times (Sullivan 1999, pp. 184–85). According to Da Ming Huidian 大明會典 (Collected Statutes of the Ming Dynasty), only the emperor and the empress were allowed to wear garments decorated with five-clawed dragons.18 Admittedly, the Ming sumptuary law was not always strictly followed, but with the five-clawed dragon’s intimate relationship to the emperor, the use of this particular motif was closely monitored, and it would be treasonous to use the image unless granted permission by the emperor himself. When Xiaojing died in 1611, her son has already been declared the Heir Apparent, but he had not yet ascended to the throne, not to mention that his legitimacy to succession was still under debate. This means that at the time, Xiaojing was poised to become Empress Dowager, yet only died as the Imperial Honored Consort who was out of favor. Therefore, Xiaojing hardly had any chance to be granted or even wear such an extravagant dragon jacket during her lifetime. The baizi jackets were thus likely to have been made for Xiaojing to be worn in her afterlife as Empress Dowager.

Figure 6.

(a) Front panel of Baizi jacket on the corpse of Xiaojing. Replica. Embroidered silk. Capital Museum, Beijing. (b) Back panel of Baizi jacket on the corpse of Xiaojing. Replica. Embroidered silk. Capital Museum, Beijing. Images provided by Professor Wang Yarong (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences).

We can further speculate on the intended function of the baizi jackets through considering them within the textile ensemble of Xiaojing from Dingling. In traditional China, the afterlife was often imagined as mirroring the living world. Similar to living men, the departed were expected to “live” inside the tomb, eat and drink from the prepared utensils, wear clothes, and even enjoy dance and music performances.19 Some of the textiles from the Dingling Mausoleum were found with tags that specify their dates of production. From these tags, it is clear that some clothes were worn or intended to have been worn by the deceased during their lifetime, while others were likely to be tailored specifically for the funerary context.20 Notably, many textile pieces in Dingling bear seasonal designs that are appropriate for specific occasions that the deceased could have encountered during their lifetime, and would continue to experience in the netherworld. For example, a mandarin square found in Xiaojing’s coffin depicts a pair of tigers surrounded by the “five poisonous creatures” (wudu 五毒, which refers to scorpion, viper, centipede, lizard and toad), a common motif for the Duanwu Festival (Figure 7).21 A comparison between the designs on the baizi jacket folded underneath Xiaojing’s body (Figure 8) and an imperial court overvest collected at the Asian Art Museum at San Francisco (Figure 9) suggests that this baizi jacket might have been made for Xiaojing to wear on her birthday celebration as the Empress Dowager in her afterlife. Although one is a vest and the other is a jacket, the two garments display striking similarities in the design of the dragon motifs, the pictorial composition, the color palette, and the embroidery techniques. The dragons on both garments feature design elements characteristic of the Wanli period, with spiky eyebrows and rainbow-colored hair.22 Both of them feature five-clawed dragon, which was appropriate for high-level court use. The juxtaposition of the dragon and the Chinese characters of wanshou (萬壽, longevity for ten thousand years) are also very similar on these two pieces, where the characters appears above the dragons on both the front and back sides of the garment. Both of them were constructed with the exquisitely embroidered red twill damask. An embroidered inscription inside the lapel of the San Francisco vest records that it was made on the fifth day of the eleventh month in 1595, which was just two days before the fiftieth birthday of Empress Dowager Xiaoding 孝定太后 (d. 1614)—the mother of Emperor Shenzong. This had led specialists to conclude that the vest was most likely made for this celebratory occasion.23 We may thus infer that Xiaojing’s baizi jacket might also be prepared for a similar occasion in the underworld to be worn by Empress Dowager Xiaojing.

Figure 7.

wudu square. Embroidered silk. After (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, vol. 2, figure 126).

Figure 8.

Front panel of Wanshou Baizi jacket from Xiaojing’s coffin, Ming Dynasty, Wanli period, 1573–1620. Line drawing after embroidered silk textile. Excavated from Dingling. Palace Museum, Beijing. After (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, figure 234 (A)).

Figure 9.

Imperial court overvest, 1595. China. Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Reign of the Wanli emperor (1573–1620). Silk satin with silk, silver, and gold embroidery. Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, Museum purchase, City Arts Trust Fund, 1990.214. Photograph © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

However, compared to the San Francisco vest, the jackets of Xiaojing are even more extravagant, featuring embroidery techniques with greater complexity and richer decorations. For instance, on the baizi jackets, the gold thread is used in many creative ways. Contours of certain figures feature gold threads wrapped around a wire core. This technique makes the outlines thicker and shinier than simple gold threads, thus making the shapes pop out from the background. The sculptural texture of the dragons’ faces is produced by couching stitches, which fixes the threads on the textile’s surface with gold knots along the outlines. The bodies of the dragons are filled with gold threads in chevron stitches to create the visual impression and material texture of the dragon scales, while the gold piling technique emphasizes the prominence of the dragons on the textile surface. In addition, the shadow on one side of the dragons’ bodies created by the alternating dark green peacock feather and thin golden thread gives them a three-dimensional visual effect. And as the jacket moves with the wearer’s body, the shimming and fuzzy peacock feather suspended in midair will give the dragons a sense of movement. And let us not forget the skillfully rendered one hundred playing boys. While the one-hundred-boys motif could be found in paintings and other decorative objects, so far, Xiaojing’s jackets are the only two cases where it appears on imperial clothing to date, making them rather unique. But more importantly, the embroidery work on the boys and their garden setting is truly masterful. It is neither necessary nor possible within the length of this paper to give a full account of all the embroidery techniques used on these masterpieces. Just to give a sense of the extraordinary craftsmanship of these jackets: the clothing and the toys of the children showcase the refined technique of net embroidery, in which the artist first applies silk floss threads as the base color, and then uses silk thread of a different color to create a variety of geometric patterns on top of the embroidered base (Figure 10); meanwhile, rendered with a combination of different stitches, including but not limited to the radiating stitches, seed stitches and locking stitches, the trees, flowers and rocks motifs are dynamic and everchanging.

Figure 10.

Detail of baizi jacket, front panel, original. After (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1989, plate 49).

If the mother of Emperor Shenzong had indeed worn the San Francisco vest on her big celebration of the fiftieth birthday, it must have been seen by all three occupants of Dingling, as well as the royal princes, including future Emperor Guangzong. It seems that, to some extent, the baizi jacket with the wanshou characters follows an existing format of a birthday costume as observed on the vest; but it surpasses the vest in terms of the design, material, and craft technique. Was this variation a conscious decision when this baizi jacket was commissioned? If so, what was the reason? Were the jackets meant to make Empress Dowager Xiaojing outshine her mother-in-law in the afterlife, and thus assert an even more prominent status than the former Empress Dowager and impress other members of the court? Or did their presence make up for the lack of a live event for Xiaojing’s birthday celebration as the Empress Dowager? Did they commemorate Xiaojing and her supporter’s political victory over Shenzong and Consort Zheng? For now, there is not enough evidence to fully account for these questions. But we could still say that with such a resemblance to the San Francisco birthday vest, Xiaojing’s baizi jackets draw attention to her high position as the Empress Dowager. And through their flamboyant decorations with luxurious materials, these jackets made the prominent status of Xiaojing visible not only to her company in the other world, but also to the living men and women who were involved in or witnessed the commissioning, making, transportation and final entombment of the jackets.

Moreover, an examination of the one hundred boys on the jackets further reveals that the design of the baizi jackets was not only about the assertion of political power, but specifically about a power that belongs to the mother of the emperor. As I have mentioned previously, a number of scholars have discussed the development of the hundred-boys motif from the Song Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty. They largely agree that during the Ming and Qing period, the baizi motif developed into a standard auspicious symbol of producing numerous sons, which was believed to be the foundation of a happy marriage and a prosperous household (Yang 2014, p. 37; Bartholomew 2006, pp. 58–60). But in the case of Xiaojing’s jackets, it seems that the traditional motif of one hundred boys at play is reappropriated through their carefully arranged layout, groupings, and activities in order to highlight the relationship between the elderly and the young.24 In particular, it is the caring for male children by older women that is subtly emphasized through these images.

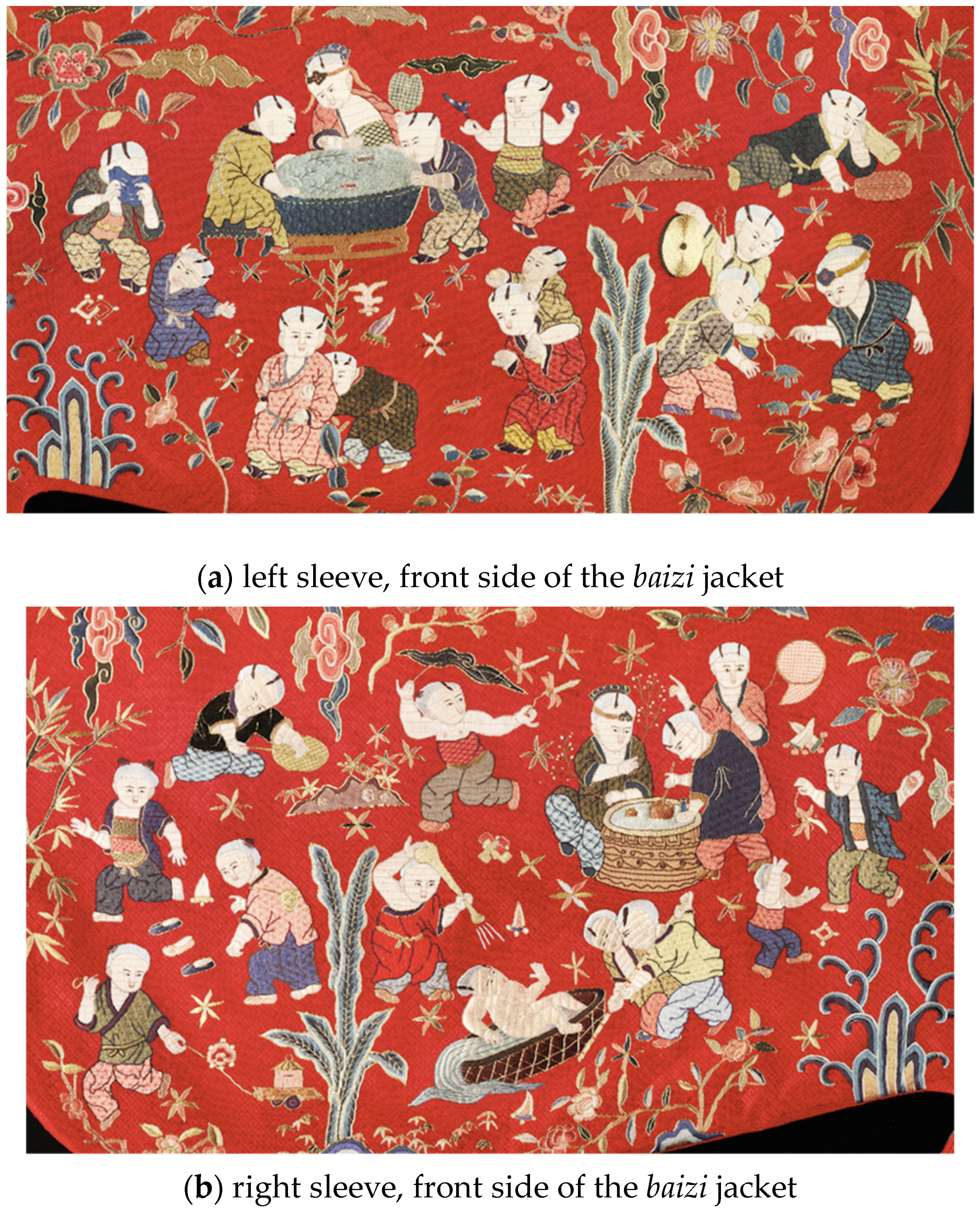

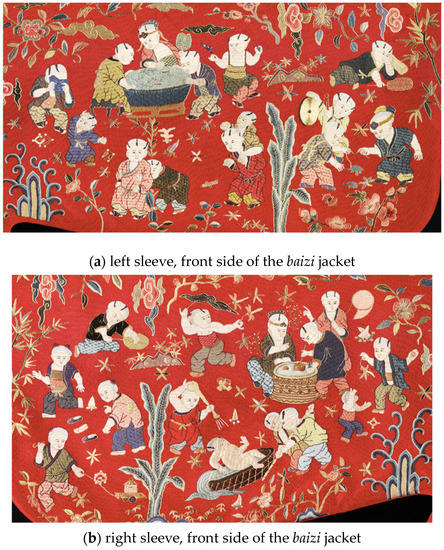

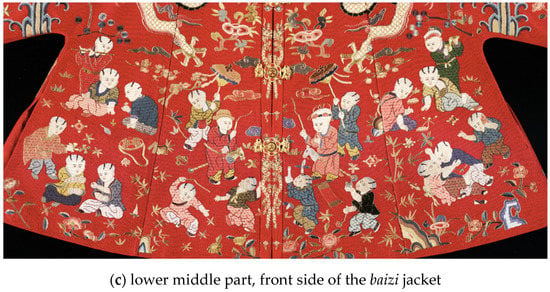

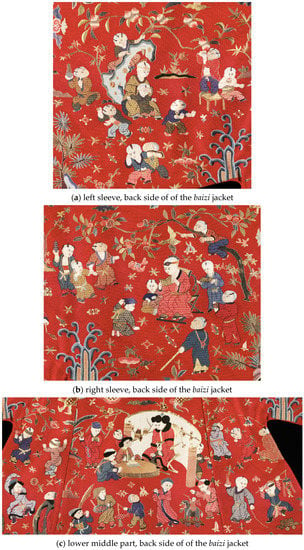

At first glance, one might find the figures on the jacket to be arranged in a rather random or even chaotic way. All the boys are rendered differently from one another, and are spread across the jacket surfaces together with a variety of plants and animals. But upon a closer look, we may find that the composition of the figures and the surrounding garden motifs is in fact symmetrical, with the vertical axis at the center of the jacket. From here on, it is convenient to turn to the shorter jacket on top of Xiaojing’s body. On the front panel, the compositions on the two sleeve echo each other. On the left sleeve, three boys stand around a fish tank to observe the fishes in the water (Figure 11a). Surrounding them are seven boys placed loosely in a semicircle engaged in a variety of children’s play with animals, objects and each other.25 To the right of this group on the other side of the banana leaves are another four children, filling the space between the main group and the edge of the sleeve. One boy with a fan in his hand is lying on the ground, leisurely watching the other three fighting turtles.26 Although the boys on the right sleeve engage in a different set of activities, the basic compositional structure mirrors to that on the left (Figure 11b). Here, the fish tank is replaced by a low round table encircled by three boys. And again, they are surrounded by seven boys in the outer circle. To their left, a boy crawls on the ground trying to catch a katydid with his fan.27 His posture is reminiscent of the resting boy on the left sleeve. In front of him is another group of three playing within their shoes and a pulling cart. Similar symmetrical compositions could also be found on the back sides of both sleeves. The scene at the lower center in the front panel is also symmetrical, with the jacket’s frontal split as the axis (Figure 11c). On each side of the split line are ten boys engaging in various activities. The eight boys in the middle—four on the left side of the split and four on the right side—form a continuous scene. Two boys, larger in scale and wearing headgear resembling the hats of government officials are at the center riding bamboo horses. They are each followed by a boy holding up an umbrella, pretending to be their servants. The four boys in front of them are dancing and playing music. These figures likely form a parodic scene of the parade celebrating the top-ranking candidates in government examinations (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, pp. 137). On the back panel, without a split, a complete scene of children sharing buns around a table in front of a screen is depicted (Figure 12c).28 This particular scene and its meaning will be further discussed later in this paper.

Figure 11.

Details of the front side of the baizi jacket on the corpse of Xiaojing. Replica. Embroidered silk. Capital Museum, Beijing. Images provided by Professor Wang Yarong (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences).

Figure 12.

Details of the back side of the baizi jacket on the corpse of Xiaojing. Replica. Embroidered silk. Capital Museum, Beijing. Images provided by Professor Wang Yarong (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences).

We can thus loosely sort the images on the baizi jacket into six modules: four in total on both sides of the two sleeves, and two on the lower centers of the jacket’s front and back. This division of pictorial space is partly governed by the shape of the jacket, where the sleeves and the lower centers are the only large blank spaces that are suitable for the depiction of elaborate scenes. But this spatial division also helps to organize the images into sections with an internal pictorial logic. Notably, within each part, a visual center is defined by the composition, the scale of the figures, the interactions between the boys, and other framing devices. This is perhaps less obvious—although not absent—in the three scenes on the front panel. But on the back panel, the focal points within the scenes are clearly defined with multiple visual techniques. On the left sleeve, a child is sitting in front of a scholarly rock, covering the eyes of a smaller boy nestled in his lap—they are playing a game of hide and seek with the eight boys surrounding them (Figure 12a). At this very moment, the two are clearly the protagonists, not only conceptually according to the nature of the game itself, but also visually as the focal point of the composition. The pair’s significance in the scene is emphasized through the larger scale of the bigger boy—which also makes him the more important figure of the pair—and enhanced through the curving rock and the extending branch of the peach tree that operate as framing devices around them. The gazes of the surrounding boys also direct the viewer’s attention to these central figures. While three boys are looking directly at the pair, two indirectly lead our eyes to the main figures. Namely, the boy on the left with a miniature pagoda in his hand is looking at the boy behind the rock, who is gazing intently at the central figures. On the right, another boy is standing on a stool to pick peaches. His gesture directs our eyes to the tree branch, which leads to the central figure on its other end. A similar situation could be observed on the other sleeve (Figure 12b). The main figure here is the larger boy in red on a chair, reading a book to the smaller boys gathering around him. He is framed by the edge of the chair and the branch of another peach tree. His centrality is also emphasized by the direct and indirect gazes of the other figures towards him. Likewise, at the bottom center of the back panel, the boy in a red winter coat and a fur hat is visually emphasized by his larger scale, the framing screen, the group activity, and the gazes of surrounding figures (Figure 12c).

The three main figures on the back panel are larger than most of the other figures, which indicate that the boys depicted are older in age than the others. Noticeably, all of them are accompanied by figures in dramatically diminished scales. The contrast in scale and age is exaggerated through the placement of these small boys extremely close to the larger bodies of the main figures: the figure on the left sleeve has a little boy who is only half his height between his legs; the figure in the chair on the right sleeve has a tiny boy sitting on the ground right next to him; at the central bottom, a small boy almost sinks into the arms of the larger figure. In other images of children playing in a garden, we might indeed find depictions of this variation in scale or age, although it is relatively rare. One example is Xia Kui’s hanging scroll at the Cleveland Museum of Art (Figure 13). Here, a boy is carrying a smaller one on his shoulders. This playful scene adds to the liveliness of the picture, but is not the clear visual focus of the whole composition.

Figure 13.

Xia Kui (Chinese, active c. 1405–1445). Children at Play, 1508. Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk; painting: 62.5 cm × 113.7 cm (24 5/8 in. × 44 3/4 in.); overall with knobs: 214 cm × 137 cm (84 ¼ in. × 53 15/16 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Charles L. Freer 1915.110.

More interestingly, it seems that the three main figures on the back of the baizi jacket are dressed as adults. The figure in front of the screen on the bottom center is wearing a fur-trimmed robe—a wintry outfit often be worn by men or aristocratic women.29 Notably, this robe is disproportionately large for the boy—the sleeves are apparently too wide and too long for him. It is likely that he is pretending to be an adult, although the gender of the pretended grownup for this particular boy remains unclear for us. In fact, images of role-playing games are not unusual for depictions of children at play. In paintings, we often find children dressed as military generals, scholars, officials, and peddlers, mimicking the activities in the world of the grown-up.30 But the role-playing scenes on the baizi jacket is rather unusual, as the other two main boys are much likely dressed up as female adults. More specifically, the two central figures on the sleeves both wear a kind of hair accessory on their shaved heads.31 Although the small size embroidered images lack precise detail, these hair accessories surely resemble mo’e 抹額, a strip of cloth decorated with embroideries or jewels to be worn across the head. According to descriptions in Ming and Qing novels, both women and men could indeed wear mo’e; but admittedly, they were especially popular among women.32 More interestingly, each of the mo-e pieces on the jacket features an additional component at the back of the head (Figure 14). It is unclear whether this part is attached to or bound using the hairband. Such hair dressing is not found in any other images of children, who are seldom if ever depicted with hair accessories in general; rather it is reminiscent of Ming women’s hairdo with tied-up buns decorated with jewels. In other words, these strange hair accessories may serve as part of the costumes for these young boys to mimic female adults.

Figure 14.

Detail of the baizi jacket, back panel, original. After (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1989, plate 62).

Therefore, it is plausible to read the older boys’ interactions with the younger boys depicted on the baizi jacket as allegorizing the relationship between adults and children. In fact, through the activities the boys are engaging in, an ideal relationship between generations—especially among women and their male offspring—is subtly outlined. During the late Ming, women’s significant role as the primary educator and caretaker of young children is frequently emphasized in didactic literature and their illustrations.33 On the baizi jackets, although the boys are playing without any adult at presence, such a role of Ming mothers is discreetly yet skillfully delineated through the activities that the role-playing older boys are engaged in. Here, one boy is playing a games with younger boys. Those who have had the experience of playing hide-and-seek would agree that it does not really take another person to cover the eyes of the seeker. To include the extra older boy—arguably dressed up as an “adult woman”—in the game might thus point to an uncommonly close and tender relationship between elderly woman and the youth in the family. Another boy dressed a female adult is educating the little boys, with a book in “her” hands. While three other boys in the same scene follow the older boy and pretend to read books, one boy in front of them is kneeling on the ground, with one hand struggling to keep a book on top of his head. Scholars have interpreted this parodic scene as the kneeling boy being “punished” by the “adult” for his bad performance in schoolwork (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, pp. 139–40). In the third scene, the boys are gathered around a low table to share buns. While every small boy has a bun in his hand, the bigger boy is only caringly watching them. Thus, the three role-playing scenes on the baizi jackets introduce three important aspects in an exemplary relationship between generations where the elderly entertain, educate, and care for the youth. Since such imagery has not been seen in any other pictures of children at play, it could be a design that was specifically customized for Xiaojing and the funerary occasion. As a result, the harmonious relationship between the women and the younger generation could be taken to allude, subtly but definitely, to that between Xiaojing as the Empress Dowager and her male offspring, Emperors Guangzong and Xizong. Such a design where the motherly role is acted out by the playing boys is also particularly fitting as a celebration of Xiaojing, who became the Dowager posthumously and is no longer there to exercise that role in the living world. However, as will be discussed in the following sections, even though Xiaojing had passed, she was never truly absent, and continued to “protect” her children from the other world.

4. Dressed to Protect

Considering the political environment at the time, the emphasis of a strong familial connection with Xiaojing as the legitimate and prestigious Empress Dowager was highly plausible and much needed. My speculative reading of the meaning and function of the baizi jackets can be further consolidated through a reconstruction and interpretation of a possible timeframe for jackets’ trajectory—from making to final inhumation—within the particular historical context. An examination of the related textual records suggests that the jackets were most likely commissioned by either Emperor Guangzong or Emperor Xizong after Xiaojing’s death, and placed into her coffin when she was moved from her initial burial site to Dingling in 1620 after Emperor Shenzong and Empress Xiaoduan had passed away.34

As mentioned previously, there would hardly have been any opportunity for Xiaojing to wear the baizi jackets when she was alive during Shenzong’s reign. The prestigious motif of five-clawed dragon was a design reserved only for the empress and the emperor; to be able to break the regulation at court would have required permission from the emperor. One exception is the birthday vest of Empress Dowager Xiaoding that has previously been discussed. Given Emperor Shenzong’s close relationship with his mother, granting her a dragon vest for the fiftieth birthday was only reasonable (Ming Shi, juan 114, p. 1483). Xiaojing’s relationship with Emperor Shenzong, however, was very different. Seen as the obstacle for Consort Zheng’s promotion through giving birth to the oldest son, Xiaojing was ignored and disliked by her husband. It is unlikely that she could have been given clothes as extravagant as the baizi jackets decorated with dragons, nor would she have had much occasion to wear them. Evidently, in the last years of her life, she was locked away in her own quarters:

In the thirty-ninth year of Wanli (1611), [Xiaojing] became critically ill. Guangzong asked for Shenzong’s permission to visit. However, [upon arrival] the gate of Xiaojing’s palace was still locked, and Guangzong had to break the lock in order to enter. [三十九年病革, 光宗請旨得往省, 宮門猶閉, 抉鑰而入]”(Ming Shi, juan 114, p. 1484).

We should also take into consideration the possibility that the baizi jackets may have been prepared for Xiaojing’s first funeral. But it seems that the chance of this is also quite low. Xiaojing died in 1611 as Imperial Honored Consort, nine years before the death of Emperor Shenzong and the empress. At the time, since Shenzong—the main occupant of the mausoleum—was still alive, Dingling was unavailable, and Xiaojing had to be buried at a temporary site. In fact, it was not until 1612 that she was hastily buried in a graveyard near the Tianshou Mountain (Ming Shi, juan 114, p. 1483). This first burial of Xiaojing was quite modest due to the indifferent attitude of Shenzong:

Academician Ye Xianggao suggested [to the emperor]: “Now that the mother of Heir Apparent has passed away, her funerary rites should be elaborate.” It was met with no response. He made the request for the second time, and it was eventually approved. [學士葉向高言: “皇太子母妃薨, 禮宜從厚。” 不報。 復請, 乃得允。](Ming Shi, juan 114, p. 1484)

Without the support of Emperor Shenzong, the Heir Apparent—future Emperor Guangzong—worked with the Department of Rites in planning the funeral.35 But they did not have enough money to carry out the elaborate funeral they had envisioned. Taken aback by the unfortunate situation, one of the head officials lamented:

The Honored Consort gave birth to and raised a righteous [Heir Apparent], and will become the mother of the empire. How is it that her [burial] became the most frugal within the entire empire? [貴妃誕育元良, 他日國母也, 奈何以天下儉乎!].(Ming Shi, juan 217, p. 2507)

Under these circumstances, it is unlikely that the extravagant hundred-boys jackets were included in this first burial.

The baizi jackets might have been commissioned by Emperor Guangzong. But given the brevity of Guangzong’s reign, they were most likely commissioned by Emperor Xizong.36 They were then added to Xiaojing’s burial goods in 1620 when the coffin was relocated to Dingling, along with the coffins of Emperor Shenzong and Empress Xiaoduan. According to Daming Huidian, during the reburial ritual, it was not unusual to add new offerings to the ensemble; the old coffin could also be replaced, or opened to include more objects.37 Burial goods of Xiaojing that can be securely dated to the time of her second burial have be found in Dingling, suggesting that new funerary goods were indeed added for the reburial. One such example is the posthumous tablet, on which the inscription states that it was presented by Emperor Xizong in the forty-eighth year of Wanli’s reign (1620). While no dated inscription was found on the hundred-boys jackets, the way one of the jackets was placed indicates that it was added some time after the initial burial, as it was placed on top of the deceased body rather than worn. In the archeological report, it is recorded that Xiaojing’s corpse was discovered in a set of simple-patterned silk garments including two blouses and a pair of trousers. These humble clothes correspond to her lower status as Imperial Honored Consort, especially when comparing to the robe embroidered with the twelve imperial symbols (xiu shier zhang gunfu 繡十二章袞服) on Emperor Shenzong’s body, and the embroidered formal jacket with a mandarin square depicting a dragon worn by on Empress Xiaoduan.38 However, on top of these three plain garments was laid another set of clothing—a jacket and two skirts (Institute of Archaeology et al. 1990, p. 25). Although the archeological report does not specify what these clothes are, it does mention that the two skirts were in turn placed over Xiaojing’s body; the line drawings also indicate that the arms of Xiaojing are actually wrapped in the inner layer of clothing, and are not put through the sleeves of the outer jacket.39 This is corroborated by a recounting of the excavation of the Dingling Mausoleum by two archeologists who worked on the team. Upon opening Xiaojing’s inner coffin, they first saw a covering blanket brocaded with a Buddhist amulet. When they removed the blanket, they found the short baizi jacket with the matching bottoms. It was only when they lifted the baizi set atop and unwrapped two additional layers of brocade quilts that they finally revealed the body of Xiaojing (Yang and Yue 1997, pp. 272–78). Such complicated layering of textiles both on top of and worn on the corpse is not seen with the other two tomb occupants. A possible explanation is that this short baizi jacket was meant to be added to the burial goods and properly worn on Xiaojing during her second burial. Since the reburial took place eight years after the first one, the body was so badly decayed that it was impractical to replace the original burial clothes with the new hundred-boys jacket.

Having sketched an approximate timeframe of the jackets’ thingly lives between the years from Xiaojing’s death in 1611, her first burial in 1612 to the relocation of her coffin to Dingling in 1620, we can now better understand their function and meaning within the historical context during the time. By the time of Xiaojing’s death, her son—the future emperor—had already been named Heir Apparent. However, his status was not secure. The biggest threat was Zhu Changxun, the son of Consort Zheng—Emperor Shenzong’s favorite concubine. Although Zhu Changxun was only given the title of King Fu 福王, and was expected to leave the capital for his feudal land in Luoyang 洛陽, Emperor Shenzong and Consort Zheng delayed his departure with the intention of finding him an opportunity to replace the current Heir Apparent (Fan 1994, pp. 358–60). With the support of Shenzong, Consort Zheng and Zhu Changxun were also evidently behind several incidents targeting the Heir Apparent, and it appears that they even hired an assassin to attack the Heir Apparent (Fan 1994, pp. 331–50). These incidents caused great unease and debates at court. After Shenzong’s death, Emperor Guangzong continued to be threatened by his half-brother and Consort Zheng after he had taken the throne. Shenzong’s last word on his deathbed was to proclaim Zheng as his empress, in the hope that as Xiaoduan and Xiaojing had both passed, the living Consort Zheng would assume the high position of the Empress Dowager. Zheng also actively sought power through colluding with Guangzong’s favorite consort, Chosen Consort Li (Li Xuanshi 李選侍), through whom she hoped to manipulate the young emperor. Guangzong, on the other hand, was eager to secure his mother’s status—and consequently his own legitimacy—through insisting on moving her coffin to the imperial tomb of Dingling.40 Unfortunately, only one month after his coronation, Guangzong was poisoned and died. It was widely believed at the time that the mastermind behind the murder was none other than Consort Zheng.41 As a result, the rivalry between the two parties only escalated. Guangzong’s struggle against the force of Consort Zheng was carried on by Xiaojing’s grandson Zhu Youxiao 朱由校, later known as Emperor Xizong. On the second day after Guangzong’s death, the daring Consort Zheng and Li detained the fifteen-year-old Xizong in his palace. They demanded to be granted the titles of Grand Empress Dowager (tai huang taihou 太皇太后) and Empress Dowager and to be allowed to attend to state affairs (欲邀封太后及太皇太后, 同處分政事). Their unprecedentedly bold demands were met with harsh criticism and dismissed by the ministers.42 As soon as Xizong had succeeded the throne, he quickly granted his grandmother the title of Empress Dowager Xiaojing in an imperial edict. He then hosted the ritual ceremony for the relocation of Xiaojing’s coffin on the same day as the interment of Emperor Shenzong and Empress Xiaoduan at Dingling.43

To sum up, with their authority constantly changed by the faction of Consort Zheng, who tried to climb the power ladder through becoming the Empress Dowager and even the Grand Empress Dowager, it was necessary for both Guangzong and Xizong to consolidate their own status. This had to be done through securing the rightful position of the legitimate and prestigious Empress Dowager for Xiaojing, their biological mother and grandmother, respectively. As a state monument and the setting of ritual ceremonies of the highest level, the Dingling Mausoleum was the perfect stage for the new emperors to consolidate this preferred identity of Xiaojing, as well as their idealized relationship with her. With the visual emphasis on the political prominence of the wearer and the familial connection between women and their male offspring, the baizi jackets fit into the political agenda related to Dingling and made up an essential part of the funerary program at a particularly unstable historical moment.

5. Coda: Politicized Body, Agentic Object, Perpetual Connection

In this paper, I have engaged in a close reading of Xiaojing’s hundred-boys jackets through resituating them within their original funerary environment, attending to their visual and material features, and reestablishing them within the particular historical moment. As an integral and important part of the Dingling Mausoleum where the two identities of Xiaojing coexist, the baizi jackets emphasize Xiaojing’s elevated status as the Empress Dowager. In this way, they draw attention to the maternal bloodline of Guangzong and Xizong. With their unique design that was subtly adapted the familiar trope of baizi, as well as their unusual placement and historical trajectory, the two jackets of Xiaojing not only reflected but also participated in her son and grandson’s power struggles during and especially after her lifetime.

But there is more to the story than the politicization of Xiaojing—a woman who had lived a tragic life—into an asset for her living offspring in the court politics. Indeed, the baizi jackets showcased the wealth, resources, and prestige that Xiaojing was given access to by her son and grandson posthumously. They were very much made to impress and remind those who had the chance of seeing the jackets—in particular, the living officials and royal family who did have some impact on court politics, and who were important enough to take part in the reburial ceremony. But this function does not fully explain the meticulous hundred-boy embroideries crafted with fine techniques and expensive materials. Since one jacket was stored under Xiaojing’s body and the other laid flat atop her, those who attended the reburial would hardly have had a chance to take a good look at the images thereon. That is to say, while Xiaojing’s high status was made clear by the jackets’ overall dazzling visual impression, the more subtle political messages crafted through the detailed renderings of the hundred-boys motif remained mostly unattainable to the attendees of the funeral.

This dilemma might be resolved if we consider another viewer of these jackets: Empress Xiaojing herself. Historian Hui-Han Jin has argued in her dissertation that the Ming Dynasty witnessed a change in the understanding of the nature of the soul and the religious function of the tomb. More specifically, in Ming burials across social strata, an emphasis on emotional attachment to the deceased and an attempt to keep a connection with the beloved buried underground can be observed through funerary objects, tomb layouts, and ritual codes (Jin 2017). These sentiments were repeatedly articulated by the founding emperor of the Ming Dynasty (Hongwu 洪武 Emperor, r. 1368–1398), who attributed his success to the blessings of his departed peasant parents, and expressed his gratitude through building them a lavish second burial at an auspicious site. In doing so, the Hongwu Emperor also hoped to maintain a blissful connection with his parents in the other world and to extend their protection to his future descendants (Jin 2017, pp. 97–107). Similarly, for Emperors Guangzong and Xizong, the luxurious baizi jackets decorated with loving scenes between motherly figures and children might have acted as a token for the young emperors to express their feelings towards their deceased mother/grandmother, and to sustain their connections with her; hopefully, upon receiving these gifts inscribed with specific messages, Xiaojing would in turn bestow her blessings to help her offspring through challenging times and to ensure the prosperity of the imperial family and the entire empire.

The layered meanings and functions of the baizi jackets coincide in one intriguing scene that appears at the lower center on the back of both jackets, where children share buns around a low table (Figure 12c). On a basic level, as part of the hundred-boys composition, this scene carries the general meaning of baizi as a popular auspicious motif related to numerous offspring. Such a motif would be suitable for an imperial consort, as giving birth to distinguished sons was not only seen as providing safety and prestige for the mother but also considered a way to ensure the perpetuation of the family name and the continuous worship of ancestors. Second, as I have noted, the larger boy seems to be wearing an adult-size robe, which might be related to the subtle theme of the exemplary relationship between generations within a family—a theme that is fitting for gifts given to a mother from her mourning son and grandson.

In the context of the imperial court, however, the baizi motif not only signified familial prosperity and domestic harmony but also took on a political connotation. It became closely connected to the fate of the rulers and the Ming state. This aspect of the baizi theme is clearly indicated in a couplet from “A Panegyric Poem in Commentary of a Baizi Picture” (yingzhi ti baizi tu 應製題百子圖) written by the famous minister Zhang Juzheng 張居正 (1525–1582) at the command of the Wanli emperor:

(The emperor) looks at the innocent boys in front of his eyes, yet thinks about all the common people in the entire realm. [眼前看赤子, 天下念蒼生。]44

A comparison between the bun-sharing scene on the baizi jackets and the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) further reveals the political significance of the baizi imagery in the particular context of the late Ming court (Figure 15). The two images bear striking visual resemblance. But whereas no inscription was provided on the baizi jackets, the painting bears an inscribed title of “Tongbao yiqi tu 同胞一氣圖,” which directly translates into “a picture of siblings in harmony.” The title, read in tandem with the bun-sharing scene, is a play of words—the character standing for “siblings” (bao 胞) is a homophone of the term for “bun” (bao 包) with the same radical, and while “yiqi” can be translated into “harmony,” it also literally means “one stream of steam.” This has led Yang Zhishui to interpret the bun-sharing iconography as symbolizing harmony in one’s household, especially among sons (Yang 2014, p. 35). Such an auspicious message became timely during the turbulent years when princes openly turned against each other and risked the wellbeing of the court’s authority. Moreover, in both the scenes on the jackets and their Yuan predecessor, we find boys wearing a mixture of Mongol- and Han-style costumes. The scene could therefore also be interpreted as implying a peaceful brotherly relationship among various ethnic groups—an idealized image in contrast with the political reality of the late Ming, whose borders were constantly harassed by the neighboring Mongols.

Figure 15.

Anonymous, Tongbao yiqi tu, Yuan Dynasty. Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, 103.3 cm × 158.9 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei.

The scene can therefore be interpreted as suggesting the resolution of the Ming court’s various pressing concerns. Most importantly, these good wishes were intricately embroidered onto the hundred-boys jackets and sent to Xiaojing. Upon receiving these encoded gifts, Xiaojing, who oversaw her living offspring from the realm beyond, might generously bestow her blessings and fulfill their desires.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This paper was originally submitted in fulfillment of the Master’s of Art in Humanities Degree at the University of Chicago in 2017. I would like to express my gratitude to Wu Hung, Andrei Pop, Wei-Cheng Lin, Megan Tusler, Lucien Sun and Jiayi Chen, who have provided invaluable comments and support during various stages of my research. I owe special thanks to Wang Yarong, an archaeologist and textile conservator at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. She introduced me to the magnificent world of Chinese textile and embroidery, and patiently answered all my countless questions. She participated in the conservation of the original baizi jackets, and led the replication projects of the two jackets.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In fact, “Empress Xiaoduan” and “Empress Dowager Xiaojing” are both posthumous names given as part of the funerary rite. It is important to note that for Empress Dowager Xiaojing, she never assumed the status of Empress Dowager when she was alive. Instead, she was referred to as the Imperial Honored Consort Lady Wang. For the sake of simplicity, I will refer to her as Xiaojing in this paper. |

| 2 | To put it simply, in the imperial family, an honored consort is subordinate to both the emperor and empress, while an emperor’s mother would not only assume power over the empress but also receive great respect from the emperor. The power structure among members of the imperial family—especially palace women—is discussed in (Hsieh 1999, pp. 47–50). |

| 3 | For the funerary rites involving the posthumous album and seal in the Ming Dynasty, see Da Ming Huidian 大明會典 (Collected Statutes of the Ming Dynasty), reprint from Wanli shiwu nian sili jian kan ben 萬曆十五年司禮監刊本 version, (Taibei Shi: Taiwan huawen, 1964), vol. 3, juan 88, 1397–1409. For a discussion of these funerary practices in the Ming Dynasty, see (Rawski 1988, pp. 228–53). |

| 4 | This episode has been documented in the oficual historical record of the Guangzong and Xizong periods. See Guangzong shenlu 光宗神錄 (The Veritable Record of Emperor Guangzong), juan 6, and Xizong shi lu 熹宗實錄 (The Veritable Record of Emperor Xizong), juan 1. The entries about the sequence of events can be found in (Li and Yang 1992, pp. 660–62). |

| 5 | For the clothing codes of the royal family, see Da Ming Huidian, vol. 2, juan 60, pp. 1017–52. |

| 6 | The specific regulation for each item is listed and described in detail in Yufu zhi, which is included in the offical history of Ming. See Ming shi 明史 (History of Ming), 1962 reprint (Taibei: Guofang yanjiu yuan, 1962), vol. 1, pp. 694–96. |

| 7 | This early inscprtion of the tomb site has been documented in Shenzong shilu神宗實錄, juan 141 in Ming Shilu 明實錄 (The Veritable Record of Ming Dynasty) (Taibei: zhongyang yanjiu yuan lishu yuyan yanjiu suo, 1966), vol. 102, pp. 2632–33. |

| 8 | The back and forth interactions between the emepror and the ministers in charge about issues related to the tomb construction—including the payment of the workers, as well as the three inspctions, are recorded in detail in Shenzong shilu, juan 164, in Ming Shilu, vol. 103, pp. 2993–2994. |

| 9 | For example, Wanli Dichao 萬曆邸抄 (Gazette of the Wanli period) documents many instances where the emperor rewarded or punished the officials for certain works on the tomb of Dingling. This text is included in (Ren and Li 2004). |

| 10 | This is recorded in Shenzong shilu, juan 228, in Ming Shilu, vol. 106, p. 4229. |

| 11 | This event has documented in Guo Que 國榷 (Debates of State Affairs), an unoffical history of the Ming Dynasty witten by a scholar named Tan Qian 談遷 (1594–1657). Tan’s goal was to document the events that were unlikely to be recorded in the state-commisioned offical history during the waning years of the Ming Dynasty. See Tan Qian, Guo Que (Beijing: Guji chuban she, 1958), vol. 5, juan 75, p. 4597; The same event, however, is also mentioned in Ming Shi, vol. 1, juan 58, p. 629. |

| 12 | Shenzong has been described in multiple accounts as a sentimental husband—a quality unsuitable for a ruler—who failed to keep his promise to his beloved wife. In fact, it seems that Shenzong did not particularly care about which son was to succeed him, but rather about his relationship to Honored Consort Zheng. This could be seen from an anecdote in Wen Bing (1609–1669), Xian bo zhi shi 先撥志始 (The notes of previous disturbance) (Shanghai: Shenzhou guo guang she, 1947), 100:

Wen Bing was the son of Wen Zhenmeng 文震孟 (1574–1636), who was a high-ranking official at Xizong’s court with a network fit for overhearing this gossip. This story is also recounted in Ming shi, vol. 2, juan 114, p. 1487. |

| 13 | The disagreement over the selection of the Heir Apparent between the ministers and Emperor Shenzong is recorded in Guo Que. The critique of Shenzong by Empress Dowager Xiaoding can be found in Ming shi, vol. 2, juan 114, p. 1483:

|

| 14 | This sequence of events have been recounted, rather colorfully, in Shenzong shilu, juan 363, in Ming Shilu, vol. 112, p. 6772 and Guangzong shilu, juan 2, in Ming Shilu, vol. 123, p. 26. In particular, warning Guangzong against fulfilling his father’s last wish, one of the ministers said,

|

| 15 | It is rather revealing that this was particularly emphasized during the times of Xizong. See Xizong Shilu, juan 7, in (Li and Yang 1992, p. 978). |

| 16 | Emperor Yingzong was buried with his empress, and Consort Zhou, mother of Emperor Xianzong (憲宗, r. 1447–1487). |

| 17 | The replicas aimed to reproduce the materials, structures, pictorial designs and all the different embroidery techniques. The two reconstructions of the jackets are now housed in the Palace Museum and Capital Museum in Beijing, respectively. |

| 18 | The various motifs suitable for people of different statuses are described in great detail in Da Ming Huidian, vol. 2, juan 60, pp. 1017–52. Notably, while the regulations change over the years (also recorded in the same text), the significance of the dragon motif remains the same. |

| 19 | Wu Hung has traced the early articulation of this belief in burial arrangements of tombs in the second century. See (Wu 2010, pp. 42–47). Also see, (Hong 2015, pp. 161–93). |

| 20 | The earliest produced piece is a robe fabric from Emperor Shenzong’s coffin dated to the forth-fifth year of Jiajing 嘉靖, only three years after the birth of Shenzong. For more texts on the tags of the textiles, see (Institute of Archaeology et al 1990,pp. 239–69). |

| 21 | According to the notes written by a eunuch to document court life and politics under the reigns of Shenzong, Guangzong and Xizong, women in the imperial household wore mandarin squares with the wudu design during the Duanwu Festival. See Liu Ruoyu 劉若愚 (1584–1642), Zhuo zhong zhi 酌中志 (Stories with wine), 1935 reprint (Shanghai: Shanghai shangwu yinshu guan, 1935), p. 176. |

| 22 | “Object description,” Asian Art Museum Website, Available online: http://asianart.emuseum.com/view/objects/asitem/items$0040:7098 (accessed on 22 February 2017). |

| 23 | Ibid. |

| 24 | While the baizi motif became popular on textiles especially since the Ming dynasty, few pieces of clothing with this motif have been preserved or are on display. I have not been able to locate any other examples of baizi jackets from the Ming period. But I have encountered a few women’s jackets with baizi motifs from the Qing dynasty. One example can be found in the collection of Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology (It was on display in 2022 at the Institute. See http://biftmuseum.com/news/detail/27112, accessed on 15 June 2023). While this piece also features an overall symmetrical composition and portrays several childplay activities similar to the Dingling jackets, it does not seem to arrange the figures in such a systematic way to deliver a consistent message, as in the case of the Dingling jackets. If anything, the parade scene appears at the front center of all of the Qing examples that I have encountered and seem to be the visual emphasis. This scene is also Ided at the front center of the Dingling baizi jackets, but is not the only visual focus of the entire garments, as will be discussed in the paper. The Qing examples are also a lot less extravagant in terms of material and technique. I thank the anonymous reviewer for raising this point. |

| 25 | From right to left, one is playing with a bird, four are wrestling, and two are playing together with a mask. |

| 26 | For a discussion of the turtle fighting game, see (Lianhai Wang 2004, pp. 110–12). |

| 27 | On the other baizi jacket, another boy holding a stick and a small cage is standing behind, which confirms this activity. See (Lianhai Wang 2004, p. 108). |

| 28 | On the other baizi jacket, the screen is replaced by branches of cherry blossom and a scholar stone, which function similarly to the screen in framing the visual focus. The buns are also more clearly show on the other baizi jacket. |

| 29 | In particular, the connection between fur-trimmed robe and Ming aristocratic women has been sugguested in (Purtle 2015, p. 307). |

| 30 | Images of children dressed up as adults in play can be found, for example, in a 12th century album leaf at the Cleveland Museum of Art. For a discussion and reproduction of this painting, see (Silbergeld and Ching 2013, p. 315). |

| 31 | Similar hair accessories also appear on several other boys on the same jacket. But their appearance on the central figures highlight their importance. |

| 32 | Da Ming Huidian discusses in several places the design of the headbands of female dancers, musicians, and wives of officials—See Da Ming Huidian, vol. 2, juan 56, pp. 61, 73. For a discussion of mo’e, see (Li and Chen 2015, vol. 1, pp. 68–73). In Xia Kui’s painting, we also find a boy wearing a similar albeit more elaborate version of such headgear, with a ruyi- or cloud-shaped textile embedding a decorative beaded center. But it differs from those on the baizi jacket, as it does not have the bun-shaped attachment to the back. |

| 33 | The role of women in childcare and education has been pointed out by (Wicks and Avril 2002, pp. 16–17) and (Walter 2002). |

| 34 | Xiaojing was first buried in 1612, almost one year after her death, in a remote graveyard near Tianshou Mountain. Her coffin was relocated together with the coffins of Shenzong and Empress Xiaoduan into Dingling in 1620. On the relocation of Xiaojing’s coffin, see Xizong shilu, juan 1 in (Li and Yang 1992, p. 662). |

| 35 | This event highlights the fielial piety of Guangzong, which was likely part of the reason that it was documented in Shenzong shilu, juan 487, in (Li and Yang 1992, pp. 649–51). |

| 36 | At least we can be certain that it was Emperor Xizong who oversaw the burial of the Wanli Emperor as well as the second burial of Xiaojing. This means that even if Emperor Guangzong indeed commissioned the two baizi jackets during his short reign, Emperor Xizong was still involved when the jackets were completed and added to the burial goods. Xizong’s involvement is further confirmed by the inscriptions on Xiaojing’s posthumous tablet, which states that it was presented by Emperor Xizong. This also tells us that at least some items for Xiaojing’s reburial were definitely made after Xizong took power. I thank one of the anonymous reviewers for pointing this out. |

| 37 | All of these, of course, would have to be carefully done in specific ways according to the regulated ritual custom. See Daming Huidian, vol. 3, juan 99, pp. 1545–46. |