1. Introduction

The story of the “Patriotic War” of 1812 (Otechestvennaia voina 1812 goda, sometimes translated alternatively as “the Fatherland War”) was a pivotal moment that, in many ways, helped define modern Russian identity. During this war, an invasion that was one episode of the broader Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), Napoleon advanced his Grande Armée of nearly 600,000 men (at the time, the largest army ever raised) into Russia, fought the Russian army at Borodino, occupied Moscow, and then retreated in defeat as his army faced starvation and capture during the brutal Russian winter. At the end of this saga, Napoleon’s imperial army was reduced to only approximately 100,000 survivors. The epic of 1812 was celebrated many times by Russian writers, either as a celebration of the common Russian soldier, as in the case of Mikhail Lermontov’s ballad-poem “Borodino” of 1837, or as a rumination on the nature of History, as in the case of Tolstoy’s epic novel War and Peace of 1869. In 1839, the Russian emperor Nicholas I (r. 1825–1855) invited the German artist Peter von Hess (1792–1871), an accomplished German battle painter and academician from Dusseldorf, to travel to Russia to complete a cycle of paintings representing key moments during the 1812 invasion. The artist trained at the Academy in Munich and served both King Ludwig I of Bavaria and Otto I of Greece. This invitation was part of an official memorialization program that employed both art and architecture in order to represent the events of the 1812 invasion according to an official narrative that, initially, stressed the sacred connection between the emperor and his people.

Immediately following the defeat of Napoleon, a number of memorial projects were planned for St. Petersburg. For instance, the centerpiece of Palace Square, which is still the symbolic heart of St. Petersburg, is a 707-ton granite victory column designed by the French architect Auguste de Montferrand, which was raised in 1834. The project was commissioned by Nicholas I, Alexander I’s (r. 1801–1825) brother and successor, and the inscription at the base of this column reads “To Alexander I from a Grateful Russia” in order to convey the message that the tsar and people were united in the effort to expel the French invader. Behind the column rests the General Staff Building of the Russian Army, completed by Carlo Rossi in 1829. The two semi-circular wings that make up the General Staff Building are joined by a triumphal arch, which, in turn, is surmounted by the Chariot of Victory by Vasilii Demut-Malinovskii (1799–1846). A number of foreign painters contributed to the story of Napoleon’s defeat as well. For instance, in 1826, Nicholas I commissioned the War Gallery of the Winter Palace, a portrait gallery that eventually contained 332 paintings representing the generals of the Russian army who took part in the campaign of 1812–1814. The portraits, painted between 1819 and 1828 by the English artist George Dawe (1781–1829) and his Russian assistants, were housed in a special gallery designed by Rossi, and the exhibition was opened to the public on 25 December 1826 with a solemn ceremony. Subsequently, Hess was commissioned to complete a series of paintings representing 12 key battles of 1812, and these were hung in several galleries adjacent to Dawe’s portraits.

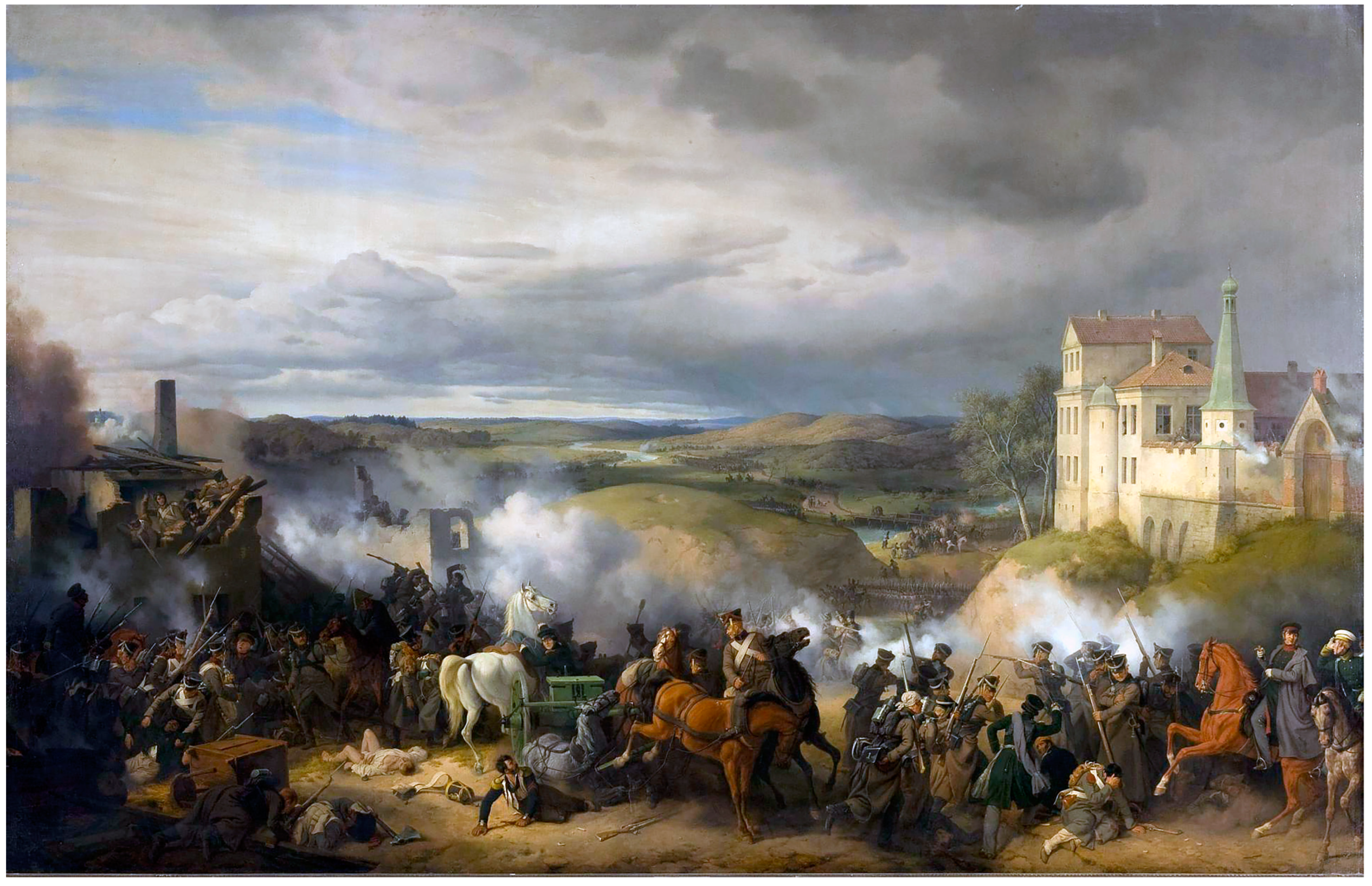

The last work in Hess’s series,

Crossing the Berezina River on 17 (29) November 1812, represents events that occurred in November 1812, at the end of Napoleon’s disastrous invasion (

Figure 1).

1 As Napoleon’s army retreated from Russia, it found itself trapped on the banks of the Berezina river, where French engineers built pontoon bridges to cross the river. Under attack by Russian guns, the French crossing turned into a bloody panic with horses and carriages rolling over dead and injured troops on the bridge. Most of the French army was able to cross; however, some 10,000 troops and a horde of disorganized stragglers remained on the east bank, where they were captured or drowned trying to cross the freezing river. Hess’s representation of the French retreat reveals that Russian national identity was defined in opposition to a foreign enemy in order to express the idea of popular unity defined by the multiethnic character of Russia’s empire.

In

Crossing of the Berezina, Hess represents Russia’s enemy at the left of his composition, where a wretched group of French soldiers make their last stand before the remains of a shattered tree trunk—like the broken column, a traditional symbol of defeat or death. While most of the figures in this group seem to have given up, one soldier faces the Russians with his bayonet ready for attack, perhaps as a reminder that the French army was once a worthy enemy. Behind the mounted figure of General Peter Wittgenstein, who led the Russians in this attack, we see Cossacks, Bashkirs, and Kalmyks—who joined the Russians and served in the irregular infantry. Their appearance, according to some sources, horrified the retreating French and led to the panic (

Sadoven 1955). Hess’s

Crossing of the Berezina celebrates the diversity of the peoples who came from the far reaches of the Russian empire in order to participate in the expulsion of a foreign, Western foe. Hess’s image of cultural pluralism presages the ways in which Russianness evolved during the course of the nineteenth century. The presence of a Western foreign invader on Russian soil resulted in unprecedented nationalistic and patriotic feelings. France, whose cultural heritage served as a model for many Russian elites, was now the foe.

In response to this crisis in national identity, educated Russians increasingly looked inward to discover sources for Russian national identity. My analysis of the paintings that made up Hess’s 1812 cycle examines a subtle shift in official representation: while earlier battle paintings and portraits commissioned by Alexander I dealt only with elite officers and the emperor, some of Hess’s paintings elevated the common Russian people as the bearers of a great sacrifice and as the true defenders of Russia. At first, Nicholas I focused on his brother’s triumphal campaigns in Europe from 1813 to 1815 with the artistic commissions, military ceremonies, and monuments that he approved (e.g., the unveiling of the Alexander Column in Palace Square in 1834). While the contribution of the common man was increasingly acknowledged in the narrative of the 1812 invasion during the reign of Nicholas I, the focus remained on imperial leadership. Overall, Nicholas I maintained the same cautious attitude that his brother Alexander I had in relation to artistic commissions dealing with 1812.

This narrative shift is the product of changing ideas concerning Russia’s involvement in several alliances from 1803 to 1815 that included Austria, England, Sweden, and Prussia. In addition, Nicholas I’s reign began with the trauma of the failed Decembrists uprising, which may provide an explanation for the conservative tone that characterized his years as ruler. Count Sergei Uvarov, Nicholas I’s minister of education, created a formula for rule—“autocracy, orthodoxy, nationality”—that served as a political and ideological response to progressive currents seeping into Russia from the West and an end to the constitutional reforms begun by Catherine II and Alexander I. As defined by Count Serge Uvarov, Nicholas’s minister of education, this doctrine employed the concept of

narodnost’ (from the Russian

narod, or “people”, “folk”) to unite the monarchy with the Russian people (

Riasanovsky 1959). Official Nationality, as this policy came to be called, relied on three pillars: the tsar, the church, and a belief that Russia possessed a unique “national character”.

2 I argue that Hess’s 1812 cycle reveals the way in which, over the course of Nicholas I’s reign, the concepts of “autocracy, orthodoxy, nationality” crept into representations of the Russian experience of the Napoleonic wars.

2. The Road to Moscow

Nicholas I’s decision to bring the artist Hess to St. Petersburg was part of the same memorialization program that transformed Palace Square described above. In 1838, on the 25th anniversary of the occupation of Paris by Russia and its allies (including Sweden and Prussia), the emperor resolved to create a series of new war galleries for the Winter Palace, in imitation of the

Galerie des Batailles at Versailles, as well as the Halls of the Battles (

Schlachtensäle) in the Munich royal palace of the Wittelsbach kings of Bavaria. Nicholas visited the latter palace in 1838 when he happened to be in Munich to arrange the marriage of his daughter Maria Nikolaevna to Duke Maximilian of Leuchtenberg. In August 1838, Hess met the poet Vasilii Zhukovsky (1783–1852) and invited him to his studio in Munich. Zhukovsky was buying paintings for the imperial collection, and on Hess’s recommendation, he purchased several dozen German paintings for St. Petersburg. The circumstance of how the invitation to travel to Russia was conveyed to Hess is not known, and Zhukovsky does not mention it in his journal. However, in March 1839, the German paper

Kunstblatt explained that Hess had been invited directly by the Russian emperor to travel to Russia. In May 1839, Hess, accompanied by his son Eugene, arrived in St. Petersburg, and on 30 July he was invited to the palace at Tsarskoe Selo where he received his orders from the tsar. He remained in Russia for four months, but he continued to work on the commission in his Munich studio for the next 17 years.

3The subject of each painting in the series was the product of an official historiography that was codified in 1836 in the

Khudozhestvennaia Gazeta (Arts Gazette) in the description of a competition for a series of memorial monuments that would be built on the sites of the keys battle of the 1812 invasion. They were chosen, as is explained in the article, “according to three classes in size and external appearance, ranked according to the significance of the battle or the degree of influence on later events”.

4 Hess was told that he should represent the same 16 battles that the monuments listed in the article were to memorialize; however, over the next few years the list was shortened and the definitive roster was supplied to Hess in the Summer of 1839. Unlike earlier official Russian battle paintings, Hess’s cycle focuses solely on the events of 1812, often referred to as the Russian Campaign, and eschews the European campaigns that proceeded and followed the invasion.

Hess’s cycle opens with the Battle of Kliastitsy, which began on 30 July, little more than a month after Napoleon’s army crossed the Nemen River. The French army had already seized the cities of Vilno and Mogilev and was advancing on Kliastitsy when Lieutenant-General Count Petr Wittgenstein’s Russian Corps blocked their path, striking quickly and retreating. The next day, Wittgenstein’s corps advanced on the village of Iakubovo, on the opposite bank of the river Nishcha from Kliastitsy. Hess’s

Battle of Kliastitsy on 19 (31) July 1812 represents the engagement that occurred when the Pavlovsky Grenadier Regiment began to cross the river Nisha (

Figure 2). Marshal Nicolas Oudinot was ordered to advance his Second Army Corps over the river Dvina and push the Russians back to Pskov. Oudinot’s corps had more than 40,000 men, while Wittgenstein’s First Corps had just 23,000; however, Oudinot turned out to be an incapable military commander. On the second day of the battle, Wittgenstein’s troops began to force the French from their position on the sandy heights of the right bank of the river, and successive attacks resulted in pushing the enemy back to the other bank. Oudinot ordered that the only bridge in the village be burned, so Wittgenstein ordered the Pavlovsky grenadiers to take it (

Bozherianov 1911, n.p.). Hess shows the final moment of the battle, when the outcome was decided on the burning bridge, which is seen in the right foreground. The advancing Russians, organized in a dense column, have seized the advantage, which is expressed in the form of their orderly ranks as they approach the bridge and in the exuberance with which they storm through the scattering French soldiers. The French, by contrast, are squeezed into the left foreground of the composition, and we see them retreating in haste. The French attempt to organize an active defense on the right bank of the Nisha had failed, and the retreating French were pursued by the Grodno Hussar regiment, who are seen in the distant background crossing the river on horseback, joined by the Yamburg Dragoons.

One must speculate why Hess’s series opened with this battle since it occurred more than a month into Napoleon’s advance into Russia. One possibility may be the fact the first Russian general to die in 1812, Jacob Kulnev, who managed to capture 900 French soldiers on the first day of the battle, was mortally wounded the next day and died soon after. However, Kulnev does not appear in this picture. A better explanation is that Kliastitsy was the first Russian victory that slowed Napoleon’s advance into Russia. The Russians succeeded in retaking Kliastitsy, and then Wittgenstein’s troops forced Marshal Oudinot’s Corps to turn back and abandon a planned march on Polotsk and St. Petersburg.

On 2 August, Generals Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly and Piotr Bagration united the two main Russian armies at Smolensk. Up until this point, the plan established by Bagration called for the First Army to retreat from the advancing

Grand Armée, while the Second Army, joined by General Matvei Platov’s Don Cossacks, would harass the French flanks. Bagration graciously conceded overall command of both armies to Barclay de Tolly, even though the former was slightly senior to the latter. Despite this gesture of goodwill and unity, two factions emerged in the debate over strategy that followed. Bagration, joined by nearly all of the other generals, wanted to take the offensive and attack the French as soon as possible. Barclay de Tolly, who initially had the support of the emperor, wished to continue the retreat and avoid fighting the French for as long as possible. In the end, Barclay de Tolly had to submit to the majority opinion, particularly since Alexander I began to increasingly call for an attack.

5While this debate was going on, the French crossed the river Dnepr and began the march on Smolensk. On 14 August, Marshals Joachim Murat and Michel Ney’s infantry encountered the Russian 27th infantry division under the command of General Dmitrii Neverovskii. Hess’s

The Battle of Krasny on 2 (14) August deals with the fate of the small provincial town near Smolensk where the battle unfolded (

Figure 3). Hess depicts the French rows, on the left, attacking the dense ranks of the Russian infantry, seen through the trees on the right. The Russian soldiers allowed the French cavalry to approach in close quarters and then shot at them point-blank from the trees. The surviving cavalrymen turn their horses as the trumpeter signals retreat. In the distance are the ranks of the Russian infantry, led by Neverovskii in a tricorn hat with black plumage and a raised sword in hand (on the right-hand side of the composition, between the rows of trees). One Russian soldier recorded in his memoirs that Neverovskii inspired his cavalry before the battle with these words: “Boys! Remember what you were taught: Follow your orders and there is no cavalry that can overcome you; just shoot accurately, don’t hurry; shoot straight at the enemy and don’t dare to shoot before my command!”

6 The two rows of birch trees at the right of the composition are again significant since they provided protection for the Russian troops as they retreated down the road, as did deep ditches on each side. The Russians were forced to retreat since Neverovskii’s detachment was outnumbered; however, this regiment did succeed in delaying the French as they approached Smolensk.

Summer rains and intense heat took their toll on the advancing cavalry of Louis-Nicolas Davout and Murat. Meanwhile, Bagration withdrew towards Minsk and the tsar abandoned the hastily built fortification that had been put up in Drissa—leaving the main road to Moscow wide open. On the advice of his senior officers, Alexander had left for the capital on 16 July since he was needed in Moscow and St. Petersburg to rally public opinion. On 15 August, Barclay de Tolly decided to send Bagration’s army eastwards while he fought a delaying action at Smolensk, hoping that its ramparts would weaken Napoleon’s army. The Russians resisted for a day and a half, during which French gunners bombed the city for over thirteen hours, setting fire to the wooden buildings of the old city. Many accounts, such as Tolstoy’s, report that the Russians felt wrath and indignation that the city was destroyed unnecessarily, and the First Army was increasingly demoralized by the return to the policy of withdrawal.

Hess’s

Battle of Smolensk on 5 (17) August 1812 is a record of the second day of this battle, during which the Russians were forced to abandon the town (

Figure 4). In the foreground on the left side, the artist had assembled a group of Russian generals, who took part in the battle: Barclay de Tolly (seated at the tree), his chief of staff Aleksei Ermolov (with map in hand and standing), and several Cossack generals including Platov and Nikolai Raevskii, whose corps heroically remained in Smolensk. Barclay de Tolly, who opposed taking the offensive against the French, is seated on the ground and can only passively watch the events as they unfold. Next to this group are the adjutant and orderly generals. The hussars have just galloped by, giving the daily report while the Cossacks remain with the horses. To the left of the tree, the unmounted artillery fire across the Dnepr at Murat’s cavalry. The commander of the artillery, who earns the medals of the order of St. George, St. Vladimir, and Malta for his participation in these events, was the 28-year-old officer Mikhail Kutuzov.

Hess’s picture serves as a measure of how the meaning of the events of 1812 began to change after the reign of Alexander I came to an end. Smolensk was a decisive battle that confirmed Barclay de Tolly’s “Scythian war plan”, or policy of retreat that lured Napoleon further into Russia. Some 10,000 French were killed or wounded while the Russians, who retreated the next day, suffered approximately 14,000 losses. The eventual abandonment and burning of this town were severe blows for the Russians, and they presaged the huge losses that both sides would experience at Borodino and the fate that Moscow faced. Finally, Smolensk became a rallying cry for all Russians. Tolstoy comments on this last point:

Smolensk was abandoned against the will of the Tsar and the whole people. But Smolensk was burnt by its own inhabitants…and those ruined inhabitants, after setting an example for the rest of Russia, full of their losses, and burning with hatred of the enemy, moved on to Moscow. Napoleon advances; we retreat; and so the very result is attained that is destined to overthrow Napoleon.

As one Soviet historian observes, Smolensk was fated to be “a new Austerlitz for the Russians”, that is, a great setback and sacrifice for the nation (

Tarle 1971).

The theme of the common man’s sacrifice is movingly expressed in Hess’s composition. In the right foreground, Hess shows us the peaceful inhabitants of Smolensk fleeing the town with their possessions and animals. That day, out of the 2250 houses, huts, and other structures that made up the town, less than 300 survived the fires. On 7 August, after the Russians abandoned Smolensk, Napoleon entered the burning city and then sent a peace offer to Alexander I, who never replied. Napoleon eventually decided to move against Moscow, calculating that the Russians would have to fight a pitched battle before the walls of their ancient capital, the result of which he never doubted.

Hess completed the painting knowing that it would be copied by other artists to be distributed as gifts to favored courtiers from the emperor. Nicholas I also commissioned lithographs of all the paintings in the series for an album, ordering the publisher to set aside 100 copies for donation to injured war veterans. The message that Destiny determined the fate of Smolensk is suggested by two details that appear in the right foreground of some of the unrevised versions of the composition, where Hess shows the peaceful inhabitants of Smolensk as they flee (

Figure 5). The message that the loss of Smolensk is part of a divine plan is expressed by the gesture of a bearded old man, likely an Orthodox priest, who points to the heavens, seemingly in response to the young peasant who looks to him for reassurance. The message is that the loss of Smolensk is part of a divine plan, and one must look to God and trust in His guidance. In addition, a peasant woman in the same group carries an icon of the Virgin with her. This is the Icon of the “Black Virgin of Smolensk” that accompanied the Russian army until the foreign invader withdrew. Nicholas I ordered that these two details be painted over in the original version—a significant measure of the power that this message had.

7The evolving tone of the narrative of the 1812 invasion is an indication of the shifting nature of Russian national identity in the middle of the nineteenth century. The emotions evoked in Hess’s painting elevated the common Russian people’s great sacrifice.

8 As Richard S. Wortman argues, beginning in 1813, Alexander I encouraged a “myth of national sacrifice and unity woven around the events of 1812” that relied on the perceived alliance between the tsar and the masses (

Wortman 1995). The seemingly popular nature of the “patriotic culture” that emerged after 1812 was initially embraced by the imperial regime, but by the time the Napoleonic Wars were concluded in 1815, official imagery of the war focused on Alexander I and his elite officers. During the reign of the next emperor, Nicholas I, the concept of

narodnost’ was introduced to collapse the distinctions between the people (

narod, in Russian), the tsar, and the nation (

Kelly and Shepherd 1998). As Alexy Miller explains, the word

narod is “extremely multisemantic” and can refer to simply a crowd and to a state’s populace, as well as to an ethnic group that has no statehood.

9 Similarly, Olga Maiorova describes the concept of Russianness as “Janus-like” in nature, in that the noun

narod could be modified with the adjectives

rossiiskii (the peoples of the multiethnic empire) and

russkii (people perceived as ethnically Russian) (

Maiorova 2010). The expanded version of Russianness represented in Hess’s painting, in which patriotism is expressed by the sacrifices that the common man, was very rarely represented in official battle paintings in the period immediately following the invasion of 1812.

Hess’s

Battle of Battle of Valutino Mountain on 7 (19) August 1812 depicts the consequences of the battle of Smolensk after the decision to begin the retreat had been taken by Barclay de Tolly on 17 August (

Figure 6). This was a strategy that was very risky for the Russians because the road to Moscow passed along one bank of the Dnepr River, within range of the French artillery. In addition, the river was very shallow at a number of spots, like the one described in Hess’s painting.

10 While the prospect of a larger battle likely tempted the emperor away from the safety of that town in pursuit of the fleeing Russians, Napoleon decided to stop in Smolensk and reform his army. At Lubino, near Valutino Mountain, the First Russian army, under the command of General Nikolai Tuchkov, met the French infantry and cavalry along the Moscow Road and fought a rearguard action to slow the French advance. His corps of 3000 men managed to hold off the French for five hours. During the violent battle, Tuchkov’s brother Pavel (also a general) and his horse were killed, and Nikolai received a blow to the head and was captured—which is alluded to by the fallen horse in the left-hand corner of Hess’s composition. The theme of the contribution of the common Russian peasant is expressed again with the image of a male figure wearing a traditional peasant shirt, who is seen in the right foreground struggling to control a horse. The urgency with which this stalwart peasant fights for control is explained by the fact that he is grappling with one of two horses that pull a cart carrying an injured soldier to safety. The battle of Valutino Mountain was chaotic and bloody: the French lost about 9000 troops while the Russian’s losses numbered over 5000. The patches of smoke across the panoramic landscape in Hess’s composition reveal the widespread fighting that went on during the retreat, and the dead and injured scattered across the foreground highlight the precariousness of the Russian position. Many historians agree that disagreements between Junot and Murat, the consequence of the French emperor’s decision to remain in Smolensk, likely spared the Russians from a truly devastating loss (

Leggiere 2016).

The loss of Smolensk and the continued policy of retreat alarmed the nobility, while most soldiers and officers were eager for direct battle with the French. Tsar Alexander I yielded to pressure from his advisers, and on 20 August he reluctantly dismissed Barclay de Tolly, whose name and manners were perceived as foreign, from high command, appointing Kutuzov as Commander-in-Chief. Alexander had a strained personal relationship with Kutuzov, but the emperor had no choice but to appoint him Commander-in-Chief. Not only was Kutuzov popular with the soldiers and officers but he was also favored by the nobilities of St. Petersburg and Moscow. Above all, Kutuzov was Russian, unlike the other candidates, and was a very experienced and skillful soldier. Alexander’s heirs, beginning with his brother Nicholas I, increasingly encouraged representations of the invasion of 1812, casting it as a struggle that united the tsar with his people, and, much later, celebrating Kutuzov as the “hero of Borodino”.

Barclay de Tolly was confirmed as commander of the First Army and Bagration as the commander of the Second. Both generals were ordered to fall back to the open country near the monastery of Kolotskoye and the village of Borodino, just over 70 miles west of Moscow. As Napoleon advanced his army deeper into Russia, his cavalry, under the command of Marshal Murat, encountered the Russians near the village of Borodino. The Russian army, under the command of Kutuzov, had been busy fortifying the town in anticipation of a French assault. On 7 September the French right wing started the attack under the command of Marshal Davout. During the afternoon, the Russian commander withdrew his troops to the second ridge due to the thousands of casualties they were sustaining under the relentless bombardment of the French Artillery. The French, due to their own losses, were in no position to pursue the Russians and continue the fighting. The Russians suffered over 45,000 casualties while the French lost at least 35,000 troops. The Battle of Borodino was the bloodiest single day of the entire Napoleonic Wars.

Hess’s

Battle of Borodino on 26 August (7 September) 1812 provides a wide panorama of the battle that includes several moments at once (

Figure 7). The battle began at six in the morning when Murat’s cavalry drove a Russian jaeger regiment out of the village of Borodino. In the counterattack the Izmailovskii and Litovskii regiments—both are pictured in the foreground of Hess’s composition—advanced upon the French. In the middle ground, the Izmailovskii battalions are seen under fire from French cavalry; further back and to the left is Murat, organizing a new mounted attack. And even further back, beyond the French artillery, the French reserve wait near Napoleon’s headquarters. Hess’s composition is rather conventional and draws upon the tradition of the military equestrian portrait. The figure of Lieutenant-General Mikhail Borozdin, in command of the Astrakhanskii cuirassier brigade, on horseback at the center of Hess’s composition corresponds to the heroic tradition of classical martial statuary and images (e.g., The Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome, 175 A.D.) advanced at the academies in Paris and St. Petersburg. The dramatic center of Hess’s picture is the wounded Bagration, who is surrounded by officers and soldiers who attempt to tend to his injuries. Significantly, the popular Russian general Kutuzov appears in just two of Hess’s pictures, and in

Borodino, he is barely visible in the far background, even though he had been appointed Commander-in-Chief the week before this battle.

11 This is a measure of the reluctance of artists working during the reign of Nicholas I to employ motifs that could provoke overtly populist sentiments.

3. Napoleon’s Retreat

The rest of Hess’s cycle deals with the denouement of the saga of 1812. After making the fatal mistake of lingering in Moscow, which allowed his cavalry to wither and for Kutuzov to reinforce his armies, Napoleon decided to abandon the city. Having failed to destroy the Russian army, the French emperor was now forced to retreat. Another matter that forced Napoleon’s hand was Kutuzov’s decision to attack Murat’s detachment as it watched the Russian camp at Tarutino. Hess’s

Battle of Tarutino on 6 (18) October 1812 depicts the encounter between the French vanguard, under the command of Murat, and the 10 Cossack regiments under the command of Orlov-Denisov (at the center of the picture) on the banks of the river Chernishnia (

Figure 8). Tarutino was the first offensive battle of the war in which the Russians were victorious; the defeated Murat lost some 3000 men as well as many cannons and other equipment. In addition, a number of French standards were captured during a series of successful Cossack attacks on enemy bivouacs. During the moment that Hess has captured, the fighting is still going on: in the background of the picture Cossacks and French cavalry are fighting, and at the center of the horizon the church of Teterinki village can be seen, where the French artillery is still bombarding the Russian infantry. Also, at the center of Hess’s composition, a soldier holds the colors of the French First Cuirassier Regiment high in the air—this was the first French standard that was captured by the Russians as a trophy during the 1812 war. Other details highlight the humiliation of the French. In the foreground, and slightly left of the central scene, a French cuirassier, who is helping a wounded officer, pleads to the Russians for aid. Slightly more to the left, several Cossacks lead their French captives, some in splendid uniforms and others, caught by surprise, still wearing their plain coats, which they slept in at night, and in caps that were usually worn out of ranks. Murat, who was seen as blessed during the course of the wars because he avoided injury, was wounded for the first time when a Cossack pike pierced his thigh.

The victory at Tarutino provided a great boost to the morale of the Russian army and forced Napoleon to leave Moscow. The common soldiers and junior officers were delighted with the result. In addition, Alexander I was informed about the victory by an aide-de-camp, who presented to the emperor the captured standard seen in Hess’s painting and transmitted the will of the soldiers that the emperor should personally take the command, which he refused. Instead, Alexander I rewarded Bennigsen with a diamond-encrusted medal of St. Andrew and 100,000 rubles, and Kutuzov was given a golden sword decorated with diamonds and laurel garland.

12The next two pictures in Hess’s cycle,

The Battle of Polotsk on 7 (19) October and

Battle of Maloiaroslavets on 12 (24) October 1812, deal with two Russian towns that shared the same fate as Smolensk and Moscow. From 16 to 18 October, Wittgenstein’s First Infantry Corps, joined by Lieutenant-General Fabian Steinheil’s Finland Corps, defeated Marshal Laurent de Saint-Cyr’s Fourth Corps. In August, Saint-Cyr had defeated the Russians at Polotsk, for which he was made marshal, but this time he was driven out of Polotsk and received a severe wound in one of the battles during the general retreat. Polotsk began to burn when Wittgenstein’s troops attacked the town, which the French had occupied since August; however, the Russians gained possession of not just the town but the bridge over the river Dvina as well. In a painting, which is now lost but can be viewed in reproductions, Hess depicts the moment when a Russian militia regiment who had volunteered to rush the ravine and, after fighting with bayonets and axes, had taken the bridge from the French. Wittgenstein appeared several times on the battlefield, at great risk to himself, and he is likely the figure who appears on a white horse slightly to the left of the bridge in Hess’s composition (

Figure 9).

13 All of the churches of this town were looted, some were destroyed, and many were turned into stables or warehouses by the French. Despite these sacrilegious acts, the Polotsk Saint Sophia Cathedral towers defiantly over the bridge in the painting, an effect that is poignantly enhanced by its illumination from the light of the fires.

An even more significant battle was fought at Maloiaroslavets, a small town in Kaluga province. Napoleon’s army abandoned Moscow on 19 October, taking the New Kaluga Road in order to avoid Kutuzov’s army. In addition, Napoleon had to avoid the Smolensk Road, where many towns had already been ravaged, because he needed a route that would supply his army with food, and a large warehouse of provisions was located at Kaluga. On 22 October, General Dmitrii Dokhturov’s Sixth Corps encountered what appeared to be a small French detachment at Fominskoe, and Kutuzov ordered an attack on the French. That evening, however, Dokhturov learned from the partisans that he was, in fact, facing the main French army. Kutuzov canceled the attack, so disaster was avoided: if Napoleon had prevailed, the Russians would have been routed and the French could have retreated with the army intact. On 23 October, Beauharnais’s Italian corps entered Maloiaroslavets and the next day, Dokhturov’s troops blocked the road to Kaluga, so a violent battle for Maloiaroslavets was inevitable.

14 Early in the morning of 24 October, Dokhturov’s corps entered the town from their position in the south, and during the rest of the day, fierce fighting took place in the streets of the town and possession of the town remained unclear. The French proved to be difficult to dislodge because they had barricaded themselves behind the thick walls of the Chernostrov Nicholas monastery, which is easily recognized in Hess’s picture because of its distinctive tower (

Figure 10). The Russians had, however, the advantage of being able to attack downhill towards the river, a reality that is captured in the high vantage point and plunging landscape that defines Hess’s composition. Fierce fighting occupies most of the foreground of the composition, with the main scene laid out like an antique frieze sculpture grouping. In the left-hand corner, the viewer sees Dokhturov (easily recognized from Dawe’s portrait) conveying orders to a junior officer. Napoleon’s decision to retreat along the Kaluga Road resulted, inevitably, in disaster.

The desperate situation that the French were doomed to face is suggested by an encounter in the foreground of Hess’s composition in which a French soldier has been thrown off his grey horse and tries to get up (

Figure 11). His pathetic gaze is met by the challenging eyes of a mounted Russian soldier. In the left-hand foreground of Hess’s composition, in what is a very witty and biting art historical reference, the body of a dead French soldier has been stripped of his uniform, and he lays in a pose that replicates in reverse the stripped body of the male figure seen prominently in the foreground of Eugène Delacroix’s

Liberty Leading the People (1830). The resemblance cannot be accidental since this area of the composition is uncluttered and accentuated by a soft light so that the viewer cannot miss it. In the far-right corner, another French soldier weeps in desperation while a Russian soldier looks at him with pity; yet, a comrade is ready to strike the enemy captive with his sword. Though the Russians had the upper hand at Maloiaroslavets, the battle resulted in more a less a draw, and that evening, the French still held the town. In addition, the town itself was left in ruins, and thousands of its inhabitants died in the fires that accompanied this fierce battle.

Despite the results of the battle, Napoleon was forced to abandon Maloiaroslavets two days later and continue the retreat, during which Kutuzov allowed nature and French indiscipline to wear down Napoleon’s army. The French moved so quickly that the main Russian army could not keep up, but Kutuzov could rely on the Cossacks and partisans to continue to harass the enemy during the hasty and disorganized retreat. The last significant clash between the two sides took place at Viazma on 3 November, where the Russians succeeded in taking the town and driving the French off the battlefield. As Dominic Lieven observes, “The battle of Viazma showed that there was still plenty of fight left in many of Napoleon’s’ troops but it also revealed his army’s growing weakness”.

15 Hess’s,

Battle of Viazma on 22 October (3 November) 1812 conveys the message that the French were indeed a worthy foe (

Figure 12). Moving from left to right, General Pavel Choglokov’s convoy is shown entering the city streets and attacking with bayonets an enemy that fiercely tries to defend its position. On the left, Choglokov is depicted on horseback as he leads his soldiers into the battle holding a raised sword.

16 In the center of Hess’s composition, the Eletsk Infantry Regiment takes part in a bayonet attack against French infantrymen. In the central scene, the viewer is reminded that the French still had some fight in them, but details in the right foreground reveal the desperateness of their situation: the transport carts and ambulance wagons of the French clog the street, so that the French cavalrymen are impeded as they hurry to hide from Russian bullets, while some artillerymen are struggling on to the carts. In addition, a group of French generals and officers on horseback can be seen trying to organize a defense. In the end, the clash between Kutuzov’s and Napoleon’s infantries resulted in a great deal more French losses.

Hess’s cycle concludes with two paintings dealing with the decline of the French army as it faced a hard, cold march through territory that was already devastated by the war and by Kutuzov’s scorched earth policy. The second encounter between the French and Russians at Krasny was not so much a discreet battle but a series of unorganized clashes that occurred between 15 and 18 November. Hess’s

The Battle of Krasny on 5 (17) November 1812 shows Napoleon’s last attempt to make a stand on the field of Krasny, near Uvarovo village (

Figure 13). Again, the desperate situation of the French is expressed in the disorder of Napoleon’s Imperial Guard who, at the end of the battle, were forced to lay down their arms and surrender. In the left foreground, General Mikhail Miloradovich instructs his aides to help a fallen French officer who pleads for his life.

This is another witty reference to a masterpiece of French battle painting, as the placement of Miloradovich recalls Napoleon’s gesture of clemency in Antoine-Jean Gros’s

Napoleon on the Battlefield of Eylau (1807–1808) (

Figure 14). On 7 and 8 February 1807, Napoleon fought a bloody, indecisive, and largely futile battle against combined Russian and Prussian forces near Eylau, a town in rural Poland. Five weeks later, the director of the Musée Napoleon announced a competition for the commission to paint the emperor on the battlefield the day after the actual fighting.

17 In Gros’s final composition, Napoleon and his entourage occupy the center of the picture, but the emperor occupies a particularly lofty position. His gesture draws on classical references to the themes of healing and clemency and combines them with Christian iconography of benediction and resurrection. In Gros’s Eylau painting, as well as in his

Napoleon Visiting the Plague-Stricken at Jaffa (1804), the French emperor is represented as both a triumphant commander and a benevolent saint. Alexander I encouraged his artists, many of them Russian, to follow the Napoleonic model when representing the saga of 1812, setting the tone for official nineteenth-century Russian battle painting. For instance, in 1815, Alexander I commissioned Vladimir Moshkov, whom many consider to be the founder of the Russian battle painting tradition, to paint

The Battle of Leipzig, which represents an episode from the four-day battle that was the culmination of the Sixth Allied Coalition’s campaign in Europe.

18In Hess’s The Battle of Krasny, another body of a French soldier who has been stripped of his uniform is seen in the opposite corner of the painting, again a nod to Deacroix’s Liberty Leading the People. On the right-hand side, the indiscipline of the desperate French soldiers is expressed, not just by the general disarray, but also by the fact that many of them have been reduced to marauding, evidenced by the variety of looted clothing (from fur coats to peasant caftans) that they are forced to wear for warmth. That day, Marshal Ney’s rearguard gave up the attempt to hold off the Russians and the French abandoned the city of Smolensk. The next day, his corps disintegrated as most of his men were either captured or killed. Ney had left Smolensk with 15,000, and the remaining 800 evaded the Russians as they made their way to the river Dnepr.

The last work in Hess’s series,

Crossing the Berezina River on 17 (29) November 1812, represents events that occurred as the French, in a panic, attempted to cross the river Berezina and were menaced by Cossacks, Bashkirs, and Kalmyks (see

Figure 1). The painting, as I argued above, celebrates the diversity of the peoples who came from the far reaches of the Russian Empire in order to participate in the expulsion of a foreign, Western foe. The definition of Russianness expanded during the reign of Nicholas I as the “ethnic nation”, to draw upon Hobsbawm’s words, began to cast a wider net with the concept of

narodnost’. The former Other, such as Cossack or Bashkir warriors, was appropriated as a symbol of Russian distinctiveness. In the first half of the nineteenth century, official battle painters working in Russia played down the role of the

narod in the expulsion of Napoleon in 1812, especially during the reign of Alexander I; under later emperors, however, the Russian concept of Nation expanded in order to include the

narod and this evolution is recorded in changing approaches to the visual narrative of 1812.

Hess employed many of the conventions of the academic battle tradition, including a high vantage point, prominent placement of elite officers and commanders in the foreground, and the classical equestrian pose; however, his inclusion of some common soldiers, the

narod, and diverse ethnic types (all in line with the doctrine of Official Nationality) presaged later currents in both official and popular Russian imagery of the Napoleonic wars, especially the campaign of 1812. The significance of this contribution is registered by the fact that when Hess’s

Crossing of the Berezina by the Russian Army was seen by the public during the 1846 Imperial Academy of Arts exhibition in St. Petersburg, it was widely praised by the critics. Even more significantly, after Hess completed his cycle, all 12 of his canvases were hung in 1860 in the central (or third) room of the new Battle Galleries of the Winter Palace, which were commissioned earlier by Nicholas I and designed by Karl Briullov.

19