1. Introduction

In recent decades, we have witnessed a proliferation of research on the experiences of Japanese American internment camp inmates, partly due to institutions’ archival work and the American government’s release of documentation (

Suzuki 2016). Over the years, debates have raged over how to denominate these camps. Although officialdom has used the term ’internees’, the characteristics of confinement and the life experiences reported by people held in these spaces have led many scholars to use words such as ‘prisoners’, ‘incarceration camps’, or ‘prisons (

Camp 2016). For example, it is often noted that the renowned anthropologist Ruth Benedict was able to compose her pivotal book on Japanese culture, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (

Benedict [1946] 2011), without travelling to Japan but merely through interviewing the inmates of Manzanar, California’s most populous concentration camp. The book was published in 1946. However, the material contained in such a book was so precise that it was used for years as a kind of set of directions as to how to handle all estates of Japanese society. What is certain is that a cluster of people who shared common ancestors and a life in a foreign country was imprisoned for the same period and for the same duration of time in structures that were created from scratch, in spaces that had not previously been made for any other population group.

We have established that artistic practice in Japanese American internment camps during the Pacific War was pivotal to the daily survival of the internees. This is confirmed by the increasing access to archival materials in addition to objects and images being constantly received by certain institutions, which has stimulated the new research presented here.

The practices of retrieving and cataloguing the works produced in the camps, detecting artistic trajectories, and exploring the specific characteristics of certain internment camps have characterised the most frequent tendencies in our exploratory procedure about the art created in these spaces. However, how the city fiction was built remains to be accounted for, as does the identification of the role that artistic activities played in the creation of such fiction, both by the predominant ideology and in revealing the secret history of these so-called ‘cities’ (

Mehta 2017).

Starting from the idea of ‘gender fiction’ as a tool for the construction of realities assigned to gender by audio-visual media (

De Lauretis 1989), we question whether there was a ‘city fiction’ that constructed the experience of dwellers in spaces that were veritable prisons, which would enable the prisoners to endure during the period of confinement in the camps, as well as during the period of protracted denial and failure by the State to recognise the damage inflicted by the government on imprisoned citizens. To be sure, photographic and artistic tools played a fundamental role in this city fiction (both to corroborate and endure it, despite its many contradictions).

Recognising the historical error of the imprisonment of American citizens only because of their Japanese ancestry can be considered a step forward in civil rights. This struggle for recognition has been intensified by the third generation of descendants, the Sansei (children of the Nisei, born in America, and grandchildren of the Issei, immigrants from Japan).

1 However, an essential aspect delaying such acknowledgment has to do with the lack of official visual documentation on the art schools created in the camps and the artistic and handicraft works produced in the period that began with Executive Order 9066, signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt on 19 February 1942.

How did art intervene in constructing a city fiction that created feigned realities in the internment camps? Throughout this article, we discuss the following:

How the State’s ideological apparatus produced a city fiction. Such an entity was an evolution of the State’s repressive apparatus. The latter was achieved through violence and physical force, and the former through the power of ideology and consensus. The school apparatus, for example, was a dominant ideology aiming to reproduce the status quo. It created a false consciousness representing an imaginary relationship between individuals and their actual conditions of existence (which subsequently became the deceptive relationships of production to which they were subject) (

Althusser 1971). What means of production were used to create this city fiction in the cases discussed here? The authors believe that the most powerful means by which this fiction was created concern art and artistic production (even if there were more activities and processes taking place in fields, games, clubs, sports, etc.). What interested us in our research was that a city fiction generated the experience of the urban, and art intervened in this experience, as we will see below, to provide some consolation and comfort.

How living conditions were made more bearable because of the city fiction.

How the city fiction created an impression of an urban reality, reflected in the government’s exhaustive photographic documentation.

How once the spaces had become inhabitable thanks to the activities developed by the inmates (with furniture, installations, etc.), the need to create aesthetic elements arose (this is where the role of art becomes important).

Simultaneously, the State organised an educational system with practical artistic subjects at all levels. Art schools were founded.

Subsequently, many artistic products were generated, reinforcing the city fiction as outlined in point 1 above: landscapes that intensified beauty, students’ works with references to American culture such as drawings of superheroes, paintings with patriotic symbols, etc. (

Wenger 2012).

There also existed dissonant works, which included elements that contravened or modified the city fiction of the State’s ideological machinery explained previously: paintings about explicit violence and surveillance.

Therefore, art plays a double role in these contexts: that of resilience and survival, reinforcing the ideological apparatus of the State, and on the other hand, documenting the cracks in the system, features of its repressive mechanism.

This article highlights how the metaphor of the city, when applied to the actual prisons (i.e., the internment camps), became, interestingly, a sort of sustainable stance. This idea is supported by the Japanese people’s constant reverence for nature, which underpinned the activity of the artists.

2 Such artists also used their scarce resources to ensure the continuity of a life that transformed the idea of prison into the concept of daily life in the city. Our findings may benefit society, since, in the current situation of conflicts and migrations, we believe that an examination of the artistic activity of the past, taking place under conditions of severe hostility, provides keys for the survival and elements for the recognition of otherness, the different, the misfits, and, by extension, minorities.

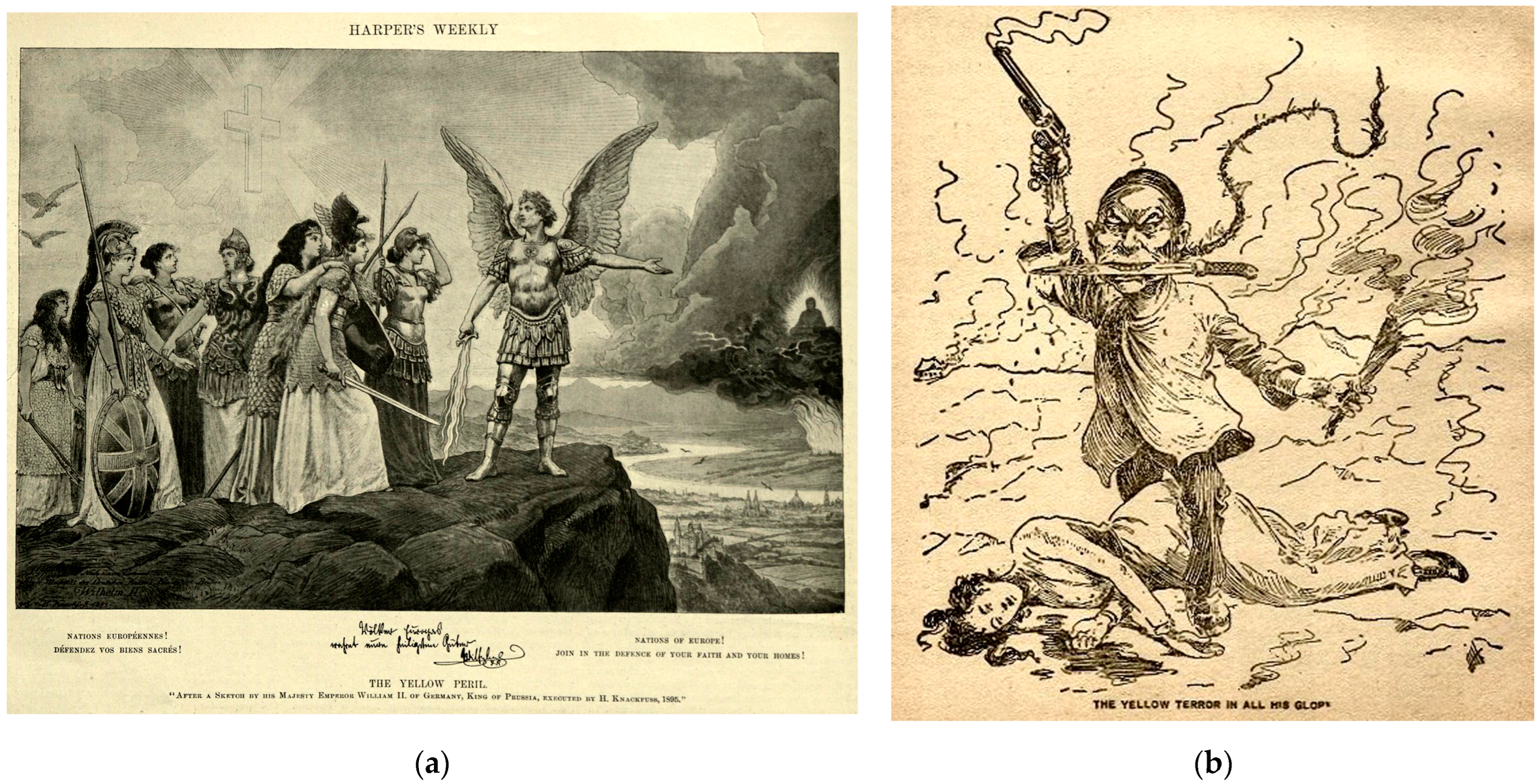

The idyllic image of the countryside portrayed in the postcards given to potential inhabitants was a misrepresentation. Within the borders of these postcards, which display the beautiful scenery of the spaces in which people would live, some texts stated the following:

“16 July. Manzanar, California. JAPS RELOCATE IN SCENIC SPOT—Evacuated from their homes in vital defence areas, alien and American Japanese have been relocated and are living in homes like these. Mt. Whitney, highest United States Peak, rising in the background, gives a touch of Mt. Fuji-dominated Japanese postcards to the pretty scene. (APNI PHOTO FROM OEM) (GWP 51007 OEM) 1942” (

Figure 1).

What could provide a more excellent feeling of home for the Japanese in America than to see a simile of Mount Fuji, as if they were in their homeland? This was an extreme example of propaganda.

Parks (

2004) points out that the U.S. government reflected upon and reacted to public opinion over time, and that a review of official documents on the Manzanar camp (released when it was politically favourable for the government) reveals contrasting idyllic images (including the ’Art Schools’) and other photographs that reveal incidents of mistreatment that resulted in injuries and deaths. These bucolic pictures came from high-profile professional photographers hired by the government (e.g., high-profile photographer Dorothea Lange and the landscape photographer Ansel Adams). Still, during wartime, only photographs that did not criticise mistreatment were used. Photojournalists who had covered the transfer of Japanese Americans from their communities to the camps were not allowed into the internment camps except for propaganda purposes. On the other hand, although internees were expressly forbidden to bring cameras and lenses into the camps, some disregarded the ban. A professional photographer, Toyo Miyatake, secretly documented Manzanar by inserting a lens and a holder inside the camp and then, with the help of a carpenter, building the rest of the camera. Miyatake took 1500 snapshots, documenting life in the camp during his more than three years in confinement (

Sadurní 2020).

It was expected that the violence would be most emphatic at the War Relocation Authority Isolation Centers, where the so-called subversives (the no-no boys or inmates who had answered NO to two critical questions on the loyalty questionnaire that was required of the inmates) were sent. For example, the control apparatus displayed along with the document entitled “War Relocation Authority Community Analysis Section” (

War Relocation Authority Tule Lake Project 1943) shows the level of violence in a similar way as images about suicides

3 as well as the use of force by those guarding the detainees (

Figure 2a,b).

2. Context: Race Fiction and Hatred of Asian-Ness: Contradictory Consequences for Artistic Works in Incarceration Camps

After the end of the Edo period from 1603 to 1868, a period of isolation termed Sakoku 鎖国 (literally, enchained country), the West rediscovered, awkwardly and gradually, some fragments of what today might be termed ‘forgotten Japan,’ a unitary set of traces emerging from a distinct culture, closely based on the natural world, which was deliberately subjected to secular isolation since the closing of borders to the outside world in the 16th century after the entry of the first expeditioners and missionaries coming from Europe. During the last quarter of the 19th century, after the beginning of the Meiji era, as well as the first quarter of the 20th century, Japanese fashion and customs triumphed in architecture, garden design, and other art forms in Europe and America.

4 As a result, many collectors became interested in Japanese art and design.

5Before Executive Order 9066, the skills of the Japanese in design, construction, and landscaping were widely recognised. Moreover, Japanese style joined other trends (Spanish Colonial Revival, Italianate, Saracen) that American artists and architects reproduced. However,

Dubrow (

2017) points out an important aspect: the people of Japanese ancestry (Issei) were limited (socially and by American law) to putting their knowledge into practice only in their native skills.

A few exceptional individuals, notably the architect Minoru Yamasaki and the landscape architect Bob Hideo Sasaki, broke through to the top reaches of their professions in the 20th century. However, most environmental designers of Japanese ancestry, particularly in the first half of the 20th century, found that a racially segregated society set boundaries on opportunities, more or less constraining where these designers could comfortably work and live, who they could enlist as mentors and clients, and the types of projects they were commissioned to undertake. Some capitalized on the fashion for Japanese design by using their presumed expertise in Japanese aesthetics to create a place for themselves in professional practice, even Nisei (American-born children of Japanese immigrants) who had spent little time in Japan and whose design education was grounded in the same Beaux-Arts and Modernist traditions as their Caucasian peers. Patronage from within Nikkei communities launched or sustained the careers of many architects and landscape designers of Japanese ancestry, particularly in the first half of the 20th century. All were affected by the waves of anti-Japanese sentiment that crested repeatedly during the 20th century, as well as by institutional racism that stranded Issei who settled in America as aliens ineligible for citizenship, state laws that undermined Issei property ownership and leasing, anti-Japanese campaigns, and ultimately the removal and mass incarceration of 120,000 innocent people during World War II (

Dubrow 2017, p. 162).

The Nisei, the descendants of the internees, were continually pressured to assimilate into the American mainstream by minimising signs of cultural difference and bans on the Japanese language, which most descendants could not utter fluently. The mistreatment of Asian communities in the arts can be traced back to the adverse reactions towards their migration to America, particularly on the Pacific Coast. These reactions resulted in acts of destruction such as vandalism, theft, and arson (

Spence 1998). The Hagiwara family presents a paradoxical case, as they were responsible for modifying and maintaining the Japanese garden in Golden Gate Park. This garden was originally built by George Turner Marsh, an Australian-born individual, for the California Midwinter International Exposition of 1894. After the fair ended, the garden was sold to the city of San Francisco. The development of the Japanese Tea Garden in San Francisco is attributed to the agreement between the Hagiwaras and the park’s superintendent. It has become one of the city’s most treasured landmarks (see

Figure 3). Unfortunately, the Hagiwara family’s 50 years of dedicated work in the garden ended abruptly when they were forcibly relocated to internment camps during WWII (

Dubrow 2017).

The shift in the life trajectories of artists after Executive Order 9066 occupies an immense range that includes a myriad of outcomes. What these trajectories all have in common is that they constitute decisive experiences and turning points in the life paths of artists of Nipponese descent that affected them in very different and drastic ways. The record of investigation, in this sense, is overwhelming: the cases of Bumpei Usui (interrogated, not interned); Isamu Noguchi (voluntarily interned, but then withheld without his consent); Mrs. Ninomiya, Hisako Shimizu Hibi, and her husband George Matsusaburo Hibi (founders of the art schools in the Tanforan and Topaz camps); Chiura Obata (teacher and director in Tanforan after George Matsusaburo Hibi); Henry Yuzuru Sugimoto (whose earlier work could not be recovered after his release from internment at Jerome and Rohwer, both in Arkansas, because it had been auctioned off); Jimmy Tsutomu Mirikitani (whose life trajectory was made known in the remarkable documentary The cats of Mirikitani); Charles Erabu (Suiko) Mikami (sumi-e specialist, interned at Tule Lake and Topaz); and Mine Okubo (interned at Tanforan and Topaz and, as we will discuss later, author of the book Citizen 13660, a graphic memoir of her confinement). The list is endless.

Interpretation of the consequences of artistic activities in the camps has been controversial over time. For example, Senator Sam Hayakawa’s testimony before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Interment of Civilians in 1981 describes life in the camps as “trouble-free and relatively happy” and, after the audible protest of internees and descendants, he justified his statement with the following idea: “How else can one explain the tremendous output of these amateur artists who, having free time, created small masterpieces of sculpture, ceramics, painting and flower arrangements?” (

Dusselier 2008, p. 1).

More contradictions are added to this problematic issue, reinforcing the idea of the city as a metaphor. From the 19th century, limitations on Asian immigrants’ access to U.S. citizenship had multiplied (

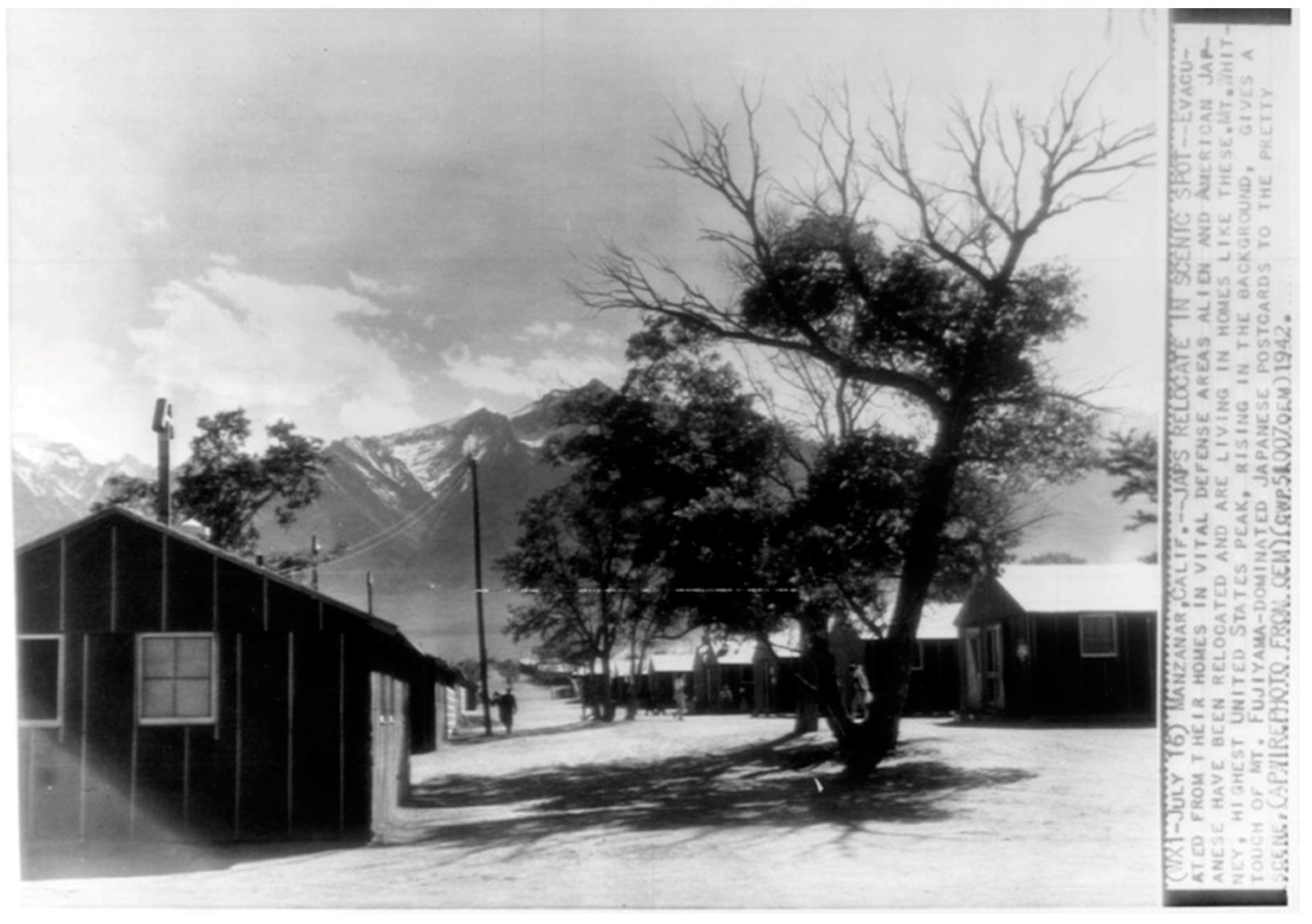

Thiesmeyer 1995). Throughout the century, anti-Asian sentiment was spreading throughout the West. Though on the one hand, Hawaii (which would not be recognised as a state until 1959) and then the West Coast of the United States (starting with the gold rush and subsequently the building of the railroads) had been welcoming numerous Asian immigrants since the 19th century, on the other hand, resentment was growing. Its seed can be identified in what some European countries called ‘the Yellow Peril’ (

Figure 3). The term did not originate in Germany but was coined by Russian sociologist Jacques Novikow (in French, Le Péril Jaune). The term coined by Novikow as Le Péril Jaune was used by Kaiser Wilhelm II (German: gelbe Gefahr) to justify colonialism in China (by Germany and other European empires). Anti-Asian sentiment in the U.S. was further intensified by the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act, limiting immigration between 1885 and 1943 (

Spence 1998). It is also interesting to note that in both images in

Figure 4, delicate European female figures, even armour-clad and protected by the holy cross in (a), seem to be the preferred object of the lustful Asian fiends.

Until 1968, the term ‘Asian-American’ was not recognised, as if Asians had not been part of that nation. However, there were discussions about Japanese, Chinese, Filipinos, and Koreans living on American soil. Numerous Asians served in the U.S. Navy in the Pacific War, but the officers were reluctant to acknowledge their citizenship, which was nevertheless demonstrated in acts of patriotism. The uncertainty and fear of civilians interned amid a world conflagration, together with the dislocation they experienced, created an unbearable psychological situation.

6 Such paradoxical treatment is reflected in several contradictions between the hatred against the Asian population (

Figure 4a,b) and the paternalistic and generous propaganda apparatus about where the future immigrants needed to settle, as we have seen (

Figure 1).

Living in prisons can feel like living in cities, with contradictions present. Citizenship and freedom of movement were limited for Japanese civilians due to long-standing hatred towards Asians and the unexpected attack on Pearl Harbor. However, the Japanese were allowed to express themselves within the confines of formal schooling, such as in middle school, high school, and art schools. The case of Miné Okubo is illustrative of these contradictions. Her revealing book

Citizen 13660 is a graphic novel about her experience in several internment camps. The book had various prefaces, each emphasising different aspects of the suffering she was subjected to. In the 1983 edition, she evaluates the outcome of her experience. For the Nisei, the evacuation opened the doors to the world (

Okubo 2004). She explains that the Nisei were the youngest, and a process of Americanisation developed within their school classes (not only in art). In the arts, the drawing referents were often superheroes or other motifs that had nothing to do with the visual culture of the Nisei’s elders or their native language (

Wenger 2012). In addition, there was a generational break, which meant the Nisei had more authority than their parents in the eyes of American supervisors (the opposite of the case in Japanese culture). The Sansei, children of the Nisei, barely understood what had happened due to their age (

Figure 5a,b). By the 1950s, the history of the Japanese American internment camps had been forgotten. In the mid-1970s and until 1981, the story was widely reported in the media (

Okubo 2004). After that, the political movements culminated in recognition and formal apologies for the camps’ existence (

Okubo 2004).

There are quite a few differences between the 1983 edition and the first edition of Okubo’s book, published in 1946. The War Relocation Authority, the agency in charge of running the camps, promoted the graphic novel, together with allies outside the government. It was part of an assimilation and absorption plan that was designed for the Nisei to abandon the roots of their ancestors (

Robinson 2012). Okubo participated by compiling the text and illustrations and making public statements that set the meaning of her narrative. However, despite these facts, the reading of

Citizen 13660 is twofold: the realities of everyday experiences appear, and the book carries a gentle critique of the situation in the camps. Moreover, looking at it from a modern perspective, the words spoken by Okubo in 1983 come across as naive. Despite years of struggle for civil rights, racial minorities in the USA continue to face discrimination, indignities, and even arbitrary imprisonment. This shows that varying degrees of work still need to be accomplished in the fight for equality among minorities. According to Christine Hong (in

Brown 2014), Okubo’s artwork was seen by some critics as a symbol of democracy, as it allowed an internee to express her views on incarceration. Upon examining Hong’s introduction to the 1983 edition, we can identify some of the individuals who defended the artist’s loyalty to American ideals: Glenn Wessels, Okubo’s supervisor during the early war years, and John Haley, who taught Okubo at the University of California, Berkeley (

Okubo 1983, p. 14).

Although there have been strides towards achieving equal rights for Japanese Americans and other Asian minorities in the United States, repeated events serve as a stark reminder of the persistent anti-Asian sentiment that exists. Unfortunately, derogatory terms for the Japanese and other nationalities are still used, as seen in Philip K. Dick’s dystopian novel that was turned into a successful series in 2015, The Man in the High Castle. Unfortunately, in today’s Western imagery, associations of Asianness with guilt still remain.

3. Results: The So-Created City Was Not What It Seemed

Numerous internees’ experiences recalled the uncertainty of being forced to move, with no one knowing where to. From the visual point of view, both the early

Citizen 13660 (

Okubo 1946) and the more recent

They call us enemy (

Takei et al. 2019) testify to psychological violence. Although Okubo’s work is more subtle, in these cases, the visual presentation uncovers that which was previously concealed within the camps.

Before discussing artistic activities in the camps, it is essential to consider several factors such as their location, topography, vegetation, climate, number of inmates, organisation of internal and external spaces, and permanence over time. These variables may influence the extent to which artistic activities can contribute to the city’s narrative or distance themselves from it.

Of course, a fiction of a city, like a figment of race, creates performances of gender. This operates logically on a cultural level. Nevertheless, the artistic images do not convey scent; they do not freeze or burn. The locations of camps were mostly inhospitable places (especially considering that a great deal of the internees had been living on the Californian coast, which has a milder climate than the extreme temperatures of the hinterland of the United States). The depictions of wind, sandstorms, and snow blizzards and the ways in which these atmospheric phenomena affected the inmate population constitute a large part of the visual work created in the camps. This echoes the remark of the philosopher Watsuji, in the sense that

history can never be separated from climate (

Watsuji [1927] 1988). Even when the focus is more on reproduction than originality, we can still see personal expressions of the population’s anguish towards the harsh climate.

Appendix A lists a selection of artworks in which the theme of atmospheric phenomena is detected using a bibliographic survey.

The mere relocation into a new place was already an act of dispossession or exile, and therefore of violence. Additionally, the consequences of relocation affected daily life if the area was barren and inhospitable. The dust and snowstorms, the extreme hot and cold temperatures, and the wind that constantly accompanied the internees are expressed pictorially in numerous works. The titles are illustrative: “Dust Storm in Topaz”, “Winter Snowstorm”, “Cloudburst in Poston”, etc.

On the other hand, overcrowding and insalubrious conditions are shown pictorially and graphically through descriptions of the Mess Halls’ interiors, the barracks, the communal laundry, and other spaces that show that families and single inmates had already lost their privacy. The testimonies of inmates spoke of unsanitary conditions, but these were difficult to describe pictorially. Miné Okubo succeeded by surrounding the inmates with gnats in her illustrations. Henry Sugimoto’s paintings, which he called Documentaries, also demonstrate these realities. For example, “Documentary, Our Washroom, Jerome camp” (1942)

7 depicts people washing themselves and at the same time cleaning clothes or kitchen utensils, and “Documentary, Our Mess Hall” (1942)

8 includes background posters with instructions such as “No Second Serving!” and “Milk for Children and Sick people only”. These graphic descriptions are not associated with an idea of a city but rather with confinement at an internment camp or sites that contravene the fiction of a cosy and livable place (

Figure 1).

We have discussed above that the internment camps were visually and verbally offered as charming spaces because of the scenic landscapes they provided (

Figure 1). This fact produced artworks and artistic experiences. By being granted something akin to the ancestral origins of the Issei, the inmates could approach inner peace through nature, aiding them imaginatively or through meditation in the quest for Dai Nippon (The Great Ancient Japan) (

Figure 6).

The painting and the poem, by an anonymous author, follow the Japanese tradition of text-to-image interaction, and a state of transcendence is portrayed in the upper section. However, it is an uninhabited space, albeit a sublime one. The lower part of the image takes us to the reality of barbed-wire fences and watchtowers. Do those boundaries define a city? Or are they more like barriers of a prison or detention centre? The image depicts the restricting boundaries of the Manzanar internment camp. However, the accompanying text suggests that the spirit can transcend these limitations and reach the highest peaks through a mystical connection to the homeland and nature. Thus, what may be assumed to be acquiescence to the government’s proposal of inhabiting a city at first sight suddenly proposes a hidden revelation. The poem is written in Kanbun (Classical Chinese), not in Japanese. Initially, the Japanese did not possess an organised writing system, and they adopted Chinese characters. As the number of these characters ranges in the thousands, they are not directly legible, and neither can they be readily pronounced; this is the reason that a kind of syllabic scripture (technically based in ’mora’ or phonetic units not unlike Sanskrit) was developed at a later stage in Japan. However, the Chinese classical script was retained as a sign of distinction or reverence. The ascetic practice of copying important texts in Chinese characters was introduced in ancient Buddhist monasteries, as the letters themselves possessed an ’enlightening’ power. Just the mere act of inking the characters on silk was vested with mysticism and undoubtedly considered a supreme ‘art’ regardless of the actual meaning of the text or poem.

As pointed out in

Ruiz (

2015),

Cabeza Lainez (

2017), and

Velázquez (

2023), oriental calligraphy symbolises an invocation, which protects both the painter and the beholder from evil while also uttering a spell or mantra.

It is difficult to conceive that any inmates, let alone the captors, could read the frame. Even the signature is illegible. Nonetheless, the protective power of ’sacred’ calligraphy would send a message of endurance amid adversity. This is not an image of a peaceful landscape that merely adheres to the government’s proposal, but it introduces some issues that must otherwise remain secret. Simply put, this work employs different codes than the ones used in the environment in which the text is displayed for all to see. The idea of self-protection through invocation is perfectly concealed by resorting to the said codes, which must remain unspoken. Such a concept of misleading images (which stem from amenable frameworks) is reinstated in many creations.

Barbed-wire fences, watchtowers, and armed guards are often incorporated into paintings as allotopias (an element that is discordant from what is expected within a genre), often without becoming the thematic focus. For example, Sugimoto depicts a soldier in a corner in

Recreation Time (

Figure 7a), a postimpressionist country recreation scene. To some extent, these paintings follow the trend of Yōga art or Western-style painting in Japanese art, which became a key cultural response to the opening of the Meiji Era. This art was made following European conventions, techniques, and materials and borrowed from essential art movements of the time. In this case, the artist relates that he did not know how to answer for his 5-year-old daughter, who was unable to return home after a picnic (

Gesenway and Roseman 1987). The calmness in the scene hides a brutal reality.

Easter in Camp Jerome (

Figure 7b) is a still-life composition featuring fruit, flowers, a bible, and an Arkansas newspaper, but the watchtower in the background betrays an unsettling reality.

On a different note, the ‘cartoon’ style used in other works often lacks physical presence due to the auxiliary lines, and it obscures any controversial or problematic themes in the artwork (

Figure 8). This is also the case in the oeuvre of Kango Takamura, a photo retoucher at RKO Studios until the Second World War. He recalled: “As you know, we cannot use any camera. So I thought sketching’s all right. But I was afraid I was not supposed to sketch. Maybe government doesn’t like that I sketch… So I work in a very funny way purposely, made these funny pictures” (

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, pp. 119–20).

In a few cases, barbed-wire fences, the barriers that indicate that the population is incarcerated, become the main object depicted in the paintings. For example, this occurs in a watercolour painting entitled

Minidoka, barbed wire montage (

Figure 9a) and many others by Takuichi Fujii in his diary, exhibited in 2017 in the show

Witness to Wartime: The Painted Diary of Takuichi Fujii at Washington State History Museum. A large portion of the diary has been published by Barbara Johns (the University of Washington Press) in

The Hope of Another Spring: Takuichi Fujii, Artist and Wartime Witness.The perception of works of art is strongly influenced by boundaries, limits, and their transgressions, which are an essential aspect of art history (

Rodríguez Cunill 2018). The barbed-wire fences suggest much pain (

Figure 9b) along with other feelings associated with that reality, such as using humour to escape (as Takamura did) or the depiction of crumbling buildings and structures (as Fujii did). This sentiment is also expressed in expressionistic charcoal drawings by Miné Okubo with an intense trace of the Mexican muralism that was part of her artistic training; in Estelle Ishigo’s

Children flying a kite, in which the kite is trapped on the barbed wire; or in the graphic representation of traumatic events such as death by shooting beside a fence (the case of

Hatsuki Wasaka shot by MP, a drawing by Chiura Obata on 11 April 1943, in Topaz). Riots, fires, and assaults were occasionally represented—for instance, in

Poston Strike Rally, a watercolour by Gene Sogioka (

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, p. 153). However, these can be considered exceptions to the usual exercises during art classes.

4. Discussing the Role of Art and Art Schools in Internment Camps—Ways towards Sustainability

Along with the sense of loss,

Dusselier (

2008) indexes the physical and mental landscapes of survival and establishes two steps. First, it was necessary to improve the degraded living conditions. The inmates created all kinds of furniture from discarded wood and cardboard pieces, tree branches, slats left by government carpenters, etc. After their furniture needs were as satisfactory as possible under such conditions, the inmates focused on aesthetic issues and decoration. This is when the activities of needlework, wood carvings, ikebana (the art of flower arranging), paintings, shell art, etc. were developed further. Undoubtedly, both aspects of activity focused on creating living environments, that is to say, on raising a city and on putting into practice the metaphor that the government itself had disseminated. When the internees created flower gardens and orchards, roads, and finally Japanese gardens, it seemed that the image projected by the American government was being put into practice. One notes that the Japanese garden, unlike the French geometric garden, is initially laid out to recreate nature.

On the other hand, the relationship with space was embedded in the peculiarities of each terrain, and the use of materials led to the creation of specific objects. In Topaz and Tule Lake, women collected objects from the soil: “tiny shells from which brooches and decorative plaques were made. Kobu evolved into a significant art form in Rohwer and Jerome, Arkansas. Discarded fruit crates were essential for furniture makers, weavers used weeds and grass to make hats, and clay provided material for sculptures and crockery. In this manner, incarcerated Japanese Americans employed physiological landscapes to refurbish the place” (

Dusselier 2008, p. 161).

Through motivational activities that fostered a sense of community, inmates could overcome challenging circumstances, which the government carefully recorded. During the uncertainty of wartime, the Issei and Nisei were a source of resistance. They even went as far as creating a city that the government photographed. However, these actions fail to recognise the pain and suffering of the victims. There seems to be a perverse mentality hidden in the propaganda apparatus that blames the imprisoned victims for continuing to live and suggests that they lived happily while in prison.

9We can detect a persevering attitude derived from these activities, since the inmates did not know how long the situation would last: their descendants might even continue to live in an internment camp. The uncertainty of the new times, which included the possibility of both liberation and extermination, forced the inmates to create living spaces for the future in any case. Ironically, one cannot help but wonder about the consequences for the internees of the arrival of a hypothetical ‘liberation’ force from Japan, which would have changed the meaning of history and the experiences of the Japanese American population (

DeFrancis 1994).

Art also allowed for the establishment of community activities (

Kamp-Whittaker and Clark 2019). Exhibitions supported and helped to reform new links between family and friend (

Figure 10a). Artistic creation conveyed emotional and mental well-being within the oppressive environment of an internment camp, and participation in art classes (

Figure 10b) and exhibitions enhanced emotional comfort on the level of relationships as well (

Dusselier 2008). Material objects were not something static that fulfilled their function once they were finished but became objects that lifted the spirit, allowed for mutual relationships, and facilitated the fabric of community and city, that is, machi-zukuri (town entwinement) in Japanese. Art helped individuals to acknowledge the painful losses of the past, recognising that such damage would never be erased or banished. Instead, these works imply an engagement with grief, because the artistic process helps us to imagine and give birth to more humane, sustainable futures.

Curiously enough, the WRA and the FBI wanted to destroy the social ties created among internees when they were released. According to

Robinson (

2012), the individuals involved were forced to commit to not engaging with other Japanese Americans after their release.

10Other aspects of resiliency embedded in this art should be emphasized.

It is worth noting that thanks to photographic documentation and the establishment of schools, we can be assured that most of the preserved work of these artists comes from their time in internment or from later artistic activity. The Hibis, like many others, had to leave behind their earlier artworks when they were sent to internment camps. However, some of George Hibi’s work has been preserved and can be found in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Although artistic practice was present, these persons have faded into history as the “silent Americans” (

Hirasuna 2013;

Nagata et al. 2019). The Nisei were reluctant to talk about their experiences, and suppressing the systemic violence inflicted upon them would not lead to any psychological or social healing. This quiet endurance, called Gaman 我慢, is the ability to resist the unbearable with patience and dignity (

Hirasuna 2013). It is a Zen Buddhist principle that we can link with resiliency. The word gave rise to the name of an exhibition at the Renwick Gallery in Washington D.C., next to the White House, which projects the idea of the re-acknowledgement of the political mistake.

The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942–1946 (

Hirasuna 2013) ran for nine months between March 2010 and January 2011. This exhibition and the one held in 1992 entitled

The View from Within: Japanese American Art from the internment camps, 1942–1945 (Wight Art Gallery, 13 October to 6 December 1992) (

Higa 1992) indicate that the work of recognition and reparation includes the extensive effort to catalogue artists, artisans, and works produced during the internment.

An intriguing concept related to resilience is the view of individuals as possessing supernatural citizenship. This is observed in cases in which individuals demonstrate, through their actions (such as artistic work or efforts to create a more livable environment), a commitment to upholding democratic principles even when the government neglects them (

Sokolowski 2009).

When Miné Okubo graphically describes the tasks of improving space, she rejects the notion of the ’villain’ or ’cruel and malicious person’ commonly associated with anti-Asian prejudices. In this sense, a model citizenry would not resist or combat the injustices of a misguided state, as we might expect at first, but would be forged by the flexible survival strategies of Asian Americans, which can transcend binary assimilation of resistance.

“Although it may seem counterintuitive, supernatural citizenship counteracts the power imbalance between citizen and state by highlighting the necessity for forgiveness. Performances of divine citizenship—in which individuals bear witness to the wrongs of the state, deliberately practice forgiveness, and look forward to a new and different future—place the power for transformative change in the hands of those groups who have endured traumatic experiences, as have the Japanese Americans” (

Sokolowski 2009, p. 90). Citizenship is projected as a condition of social membership produced by personal acts and values. In these cases, the behaviour of many internees can be read as an act of heroic pedagogy (or Divine Citizenship, in the words of

Sokolowski 2009).

The machinery for producing race fiction was added to the production of city fiction for the internment camps. In this machinery, art schools functioned as materialising agents of the city itself. The school, that ideological apparatus of the state, would watch over the creation of imaginary ideas about who the real enemy is, to control the internees’ bodies and minds. Moreover, what better method of control than one that came from the internees themselves? Hence, most of the images produced by the internees were neither problematic nor controversial. On the contrary, acting in accordance with the city fiction that had been promulgated could lead to the inmates’ survival. Moreover, here, the artistic activities reflect, as we have seen, sundry responses and accommodations or numbness of the mind.

5. Conclusions

The creation of survival strategies through the generation and teaching of fine arts and handicrafts tells us of a search for emotional and physical resiliency within the uncertainty and hardship of the situation of Japanese internees. Even from the point of view of recycling, the artwork made with the debris of the few materials at those infamous centres where no visual or graphic material was provided speak to us of a spirit of survival, in the words of Junichiro Tanizaki’s

Praise of Shadows (

Tanizaki 2015). Apart from sumi-e painting, which occurred everywhere, other examples such as miniature landscape paintings on polished stones have appeared in particular places (in this case, in Amache), as well as pictorial decoration of small carved objects and paintings on canvas in enclaves where art schools were set up to make the passing of time more bearable. Nor can we forget a curious gem of creation related to the Japanese garden. This type of garden arose as a three-dimensional recreation of landscape paintings, and curiously, numerous orchards and gardens were maintained throughout the internment.

To control and maintain order in the camps, the government implemented policies to secure the internees’ occupation and minimal satisfaction—a policy developed by encouraging creative expression through employing art and literature. In the internment camps, the government established programs to support the production of fiction, poetry, and other creative works performed by internees.

The consequences of this policy varied. On the one hand, it allowed some people to express their creativity and provided a sense of purpose and accomplishment in a complex and oppressive situation. However, on the other hand, it also allowed for prisoners to document their experiences and perspectives, which can serve as a valuable historical record of the confinement period, not unlike the current receding pandemic—a route map to avert similar dreadful failures in the near future.

Nevertheless, the government censored the production of fiction and other creative works, which was intended to control the internment narrative and maintain a positive image of the camps. This censorship could lead to self-censorship among individuals, stifling their ability to express themselves fully.

Moreover, the encouragement of creative expression in the camps does not negate the fact that the internment violated the civil rights of individuals and enacted a traumatic experience that created long-lasting effects for the subjects and their communities.

The artistic responses by internees of Japanese American camps are a form of cultural resiliency. The research carried out by some of the authorial team has explored the notion of resilience (

Rodríguez-Cunill 2021;

López-Cabrales et al. 2023). Despite the various origins of these works of art, the conclusions are similar. By creating art, people could maintain and express their cultural heritage and identity, allowing them to still retain a sense of community and self-identity during forced relocation and discrimination. In much the same way as religion has helped to instil objects and locations with sacred values, in the camps, an atmosphere of Buddhist sanctuaries and Asian shrines was recreated, including a dark, mysterious environment in which transcendence and mysticism manifested (

Salguero-Andújar et al. 2022), working as a positive and uplifting mechanism. Such art echoes the translation of images of far cities onto the canvas (

Rodriguez-Cunill et al. 2021) or the recovery of ancient cities under our feet in literary creations (

Cunill 2021).

Furthermore, these artistic responses possess a lasting cultural value, as they record the experiences and perspectives of those who endured amid the hardship of the internment camps. These works can help future generations to understand the internment’s impact on individuals and communities. In addition, they can act as a reminder of the need to protect civil rights and prevent discrimination, as similar confinement and exclusion practices happen every other day in all places and cultures.

However, it is essential to note that the artistic responses alone do not constitute a particular case of resiliency. Resilient solutions require addressing the root causes of the problem.

The government deliberately planned the fiction of the city and the ways in which cities were imagined, constructed, and represented. Just as some aspects are a social construct shaped by cultural and historical forces, cities are also erected and given form by social, political, and economic strains. The representation of cities in fiction may reflect specific cultural ideas and values while modelling our understanding and perceptions of urban spaces and communities. The development of art in the internment camps analysed here demonstrates that the internees’ reckoning of their sad reality paradoxically enriched the city fiction presented by officials.

It is essential to recognise that the places where minority groups were encouraged to settle, which functioned as cities but were abandoned and dismantled after the Pacific War, are not just memories of the past. Acknowledging this historical heritage remains relevant and significant today.

11 Additionally, we understand the kind of art produced by such minorities to be a powerful tool to mend and heal the divisions that lie ahead.