Sonorous Touches: Listening to Jean-Luc Nancy’s Transimmanent Rhythms

Abstract

:“What’s this this, who is the body? This, the one I show you, but every “this”? All the uncertainty of a “this”, of “thesis”? All That? Sensory certitude, as soon as it is touched, turns into chaos, a storm where all the senses run wild.”Nancy, Corpus

“is necessarily the challenge of an empiricism by which one attempts a conversion of experience into an a priori condition of possibility… of the experience itself, while still running the risk of a cultural and individual relativism, if all the “senses” and all the “arts” do not always have the same distributions everywhere or the same qualities”.

“that there is still sense in asking questions about the limits, or about some limits, of philosophy (assuming, then, that a fundamental rhythm of illimitation and limitation does not comprise the permanent pace of philosophy itself, with a variable cadence, which might today be accelerated), we will ponder this: Is listening something of which philosophy is capable? Or—we’ll insist a little, despite of everything, at the risk of exaggerating the point—hasn’t philosophy superimposed upon listening, beforehand and of necessity, or else substituted for listening, something else that might be more on the order of understanding?”

“someone who always hears… but who cannot listen, or who, more precisely, neutralizes listening within himself, so that he cannot philosophize?

Not, however, without finding himself immediately given over to the slight, keen indecision that grates, rings out, or shouts between “listening” and “understanding”: between two kinds of hearing, between two paces [allures] of the same (the same sense, but what sense precisely? that’s another question), between a tension and a balance, or else, if you prefer, between a sense (that one listens to) and a truth (that one understands), although the one cannot, on the long run, do without the other?”

“To be listening is thus to enter into tension and to be on the lookout for a relation to self: not, it should be emphasized, a relationship to ‘me’ (the supposedly given subject), or to the ‘self’ of the other (the speaker, the musician, also supposedly given, with his subjectivity), but to the relationship in self, so to speak, as it forms a ‘self’ or a ‘to itself’ in general, and is something like that ever does reach the end of its formation. Consequently, listening is passing over to the register of presence to self, it being understood the ‘self’ is precisely nothing available (substantial or subsistent) to which one can be ‘present,’ but precisely the resonance of a return [renvoi]. For this reason, listening—the opening stretched toward the register of the sonorous, then to its musical amplification and composition—can and must appear to us not as a metaphor for access to self, but as the reality of this access, a reality consequently indissociably ‘mine’ and ‘other,’ ‘singular’ and ‘plural,’ and much as it is ‘material’ and ‘spiritual’ and ‘signifying’ and ‘a-signifying’”.

“When he was six years old, Stravinsky listened to a mute peasant who produced unusual sounds with his arms, which the future musician tried to reproduce: he was looking for a different voice, one more or less vocal than the one that comes from the mouth; another sound for another sense than the one that is spoken”.

“which was dispersed, in which the elements would be come upon in different ways and which would consist of (1) a sound, (2) an image, (3) a text, (4) an object, (5) a line, which would be unified but the parts of which would be of interest in themselves if the connections between them were not seen (but better if seen). One of many considerations was that it be partly tactile, bodymade though using machines”.

“rhythm does not appear; it is the beat of appearing insofar as appearing consists simultaneously and indissociably in the movement of coming and going of forms or presence in general, and in the heterogeneity that spaces our sensitive or sensuous plurality. Moreover, this heterogeneity is itself as least double: it divides very distinct, incommunicable qualities (visual sonorous, etc.), and it shares out among these qualities other qualities (or the same ones), which one might name with ‘metaphors’… but which are in the final analysis metaphors in the proper sense, effective transports or communication across the incommunicable itself, a general play of mimesis and of methexis mixed together across all the senses and all the arts”.

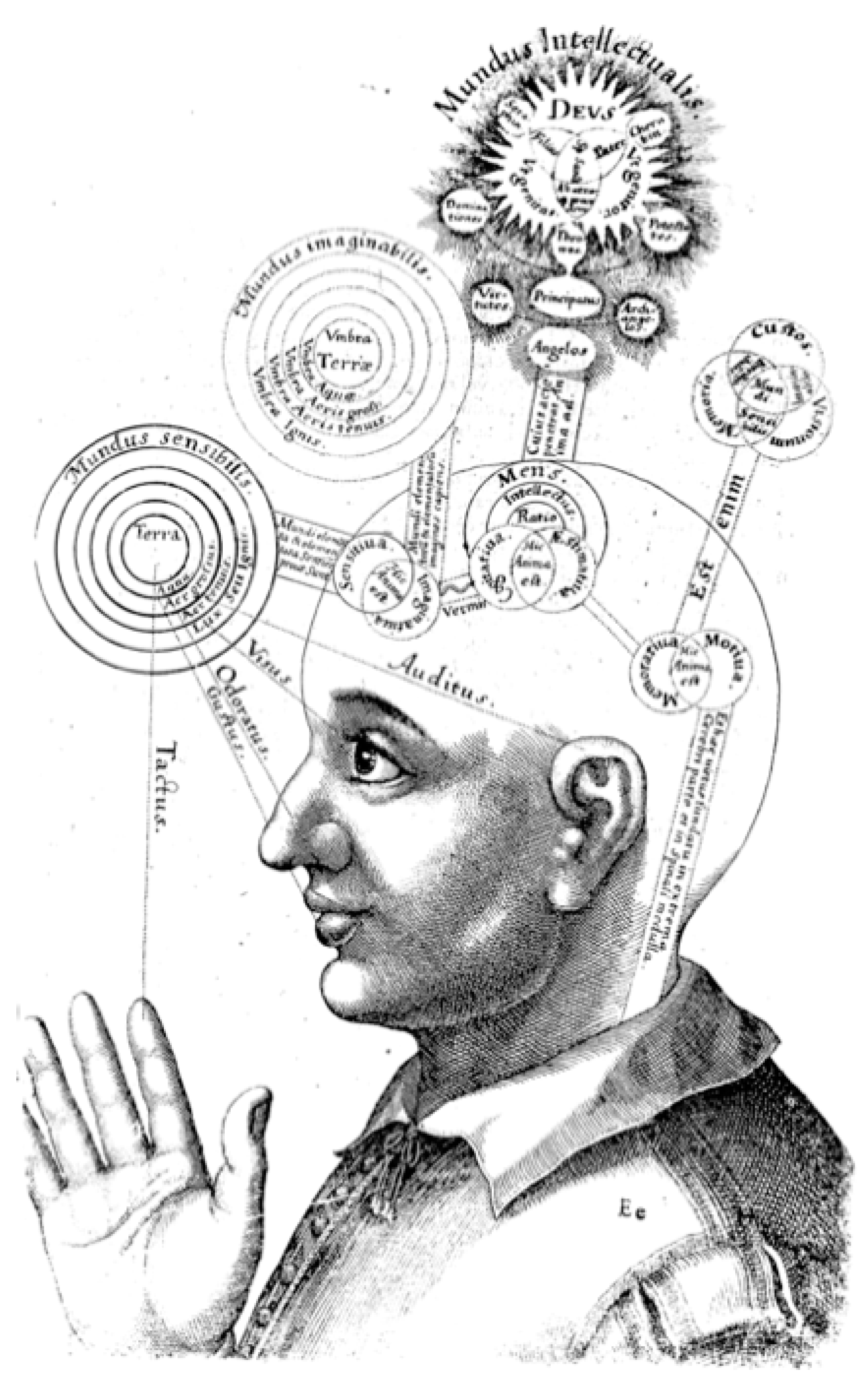

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “Here are the six categories of noises for the Futurist orchestra that we intend soon to realize mechanically: (1) roars, claps, noises of falling water, driving noises, bellows (2) whistles, snores, snorts (3) whispers, mutterings, rustlings, grumbles, grunts, gurgles (6) shrill sounds, cracks, buzzings, jingles, shuffles (5) percussive noises using metal, wood, skin, stone, baked earth etc. (6) animal and human voices: shouts, moans, screams, laughter, rattlings, sobs…” (Russolo 1986, p. 28). |

| 2 | The concepts and practices of dynamism, simultaneity and interpenetration, expand beyond the scope of this essay. I note two Futurist sources: Boccioni et al. (1910), and Marinetti’s writings on hapticity, “Tactilism: Toward the Discovery of New Senses”, originally published in 1921, (Marinetti 2006, pp. 377–82). |

| 3 | Nancy expands on Jacques Derrida’s concept of “chantier” as the singular relational site of a song (chant) and a voice. In Speech and Phenomena, Derrida criticizes Hussel’s use of the voice as bringing forth apparent transcendence. Instead, he offers auto-affection as the possibility of subjectivity contingent on the differential division of presence. Here, we may find the middle voice which precedes and sets up the opposition between passivity and activity. The middle voice that “speaks of an operation which is not an operation, which cannot be thought of either as a passion or an action of a subject upon an object, as starting from an agent or from a patient, or on the basis of, or in view of, any of these terms. But philosophy has perhaps commenced by distributing the middle voice, expressing a certain intransitiveness, into the active and the passive voice, and has itself been constituted in this repression”. (Derrida 1973, p. 137). On Nancy’s musical commentary see Listening, pp. 11–12. |

| 4 | On Nancy’s reverbs of Kant’s aesthetic philosophy see The Discourse of the Syncope: Logodaedalus (Nancy 2008b). See also Louria Hayon (2022, pp. 174–208). |

| 5 | Nancy imports Heidegger’s double sense of alētheia, first, as an epistemological disclosure of truth (which is rejected), that is, unconcealment as a correspondence between an idea and a thing it represents. Second, Alētheia as ontological truth that designated disclosure itself. In “The Origin of the Work of Art” alētheia is the interplay between concealing and unconcealing. The latter rejects ontotheological projections and ontological calculations in favor of presence, that is, that the artwork is, and its unfathomable perceptual reserve, in “The Origin of the Work of Art” (Heidegger 1971, pp. 41, 66). See also, (Magnus 1970), on Nancy’s critique of Heidegger’s dualism see Ross (2007, pp. 134–63). On the relation of truth to Listening, see Janus (2011, p. 182). |

| 6 | Snow’s early work and Nancy’s later writing concerning sonorous hapticity were practiced decades after the avant-garde’s experimentation with newly organized sound. I am referring to Italian noises and Russian transrational practices which overturned the Platonic and Pythagorean approach to harmonious metaphysics morphed in music and existence. Russolo was not alone in his sonorous slapstick, avant-garde art from the early twentieth century includes many appearances clogging harmonious systems. These include experiments in zaum by Russian transrationalism and the new Futurist’s typographies Parole in Libertà, Dada noises, Fluxus scores and more. To these I briefly note the shift propelling the empirical and unpredictable stance that appeared mid-20th century with John Cage’s silence, chance operations, the prepared piano, and the acousmatic listening of musique concrète by Jérôme Peignot and Pierre Schaeffer’s. See for example, Kahn (2001); and the recently published Weibel (2019). To note several works closer to Snow’s Tap see for example, La Monte Young’s Compositions (1960), his work with Marian Zazeela Dream House (1969), Terry Riley’s In C (1964), Nam June Paik’s Physical Music (1964), Bruce Nauman’s Bouncing in a Corner (1968–9), Alvin Lucier’s I am Sitting in a Room (1969), and Hollis Frampton’s film States (1969). |

| 7 | Brian Kane demonstrates how Nancy’s use of the verb to listen plays between the French verbs ‘entendre’ and ‘écouter.’ Their difference is displayed by positing a comparison between Pierre Schaeffer and Nancy. In Schaeffer’s phenomenological listening, entendre is related to subjective intentionality. Nancy tries to avoid this manner by giving primacy to écouter, which opens up the threshold between sense and signification to reveals the structure of resonance echoing the subject. “As the French makes explicit”, Kane writes, “the struggle between sense and truth is a struggle between écouter and entendre… ‘the subject is’ ‘a resonant subject’ because both the object and the subject of listening, in his [Nancy] account, resonate. And they resonate because the object and subject of listening both share a similar ‘form, structure or movement, that of renvoi… ‘reference’… as both a sending-away (a dismissal) and a return… Both meaning and sound are comprised of a series of infinite referrals, a sending-away which returns, only to be sent away again, ever anew”. In Kane (2012, pp. 442, 445). |

| 8 | Adrienne Janus elaborates on Nancy’s anti-ocular turn in debt to Heidegger, Jacques Attali, Didier Anzieu and Peter Sloterdijk see (Janus 2011, pp. 182–91). |

| 9 | On Nancy’s “musicking” see (Chapin and Clark 2013). |

| 10 | Janus asks why does Nancy fleetingly turns to noise and why does his “relative suppression of noise in his space of listening resemble a nineteenth-century concert hall? Why does he not make use of concepts associated with recent developments in music that would potentially be productive…” (Janus 2011, p. 200). |

| 11 | German musicologist Marius Schneider clearly defines the historical and anthropological symbolism of the speculative music portraying the cosmos as knowledge of harmonics: “The symbol is the ideological manifestation of the mythical rhythm of creation, and the degree of veracity attributed to the symbol is an expression of the respect which man is capable of according to this mythical rhythm”. In Schneider (1957). See also, (Schneider 1959, pp. 39–62; Godwin 1989). |

| 12 | On speculation and creation as a reflection of the power of vision and intellegibility see (Rorty 1979, p. 13; Jay 1993, pp. 28–29). |

| 13 | Preceding Philippe-Rameau Nouveau système de musique théorique (1726), the fundamental bass is found in his 1722 Treatise on Music. See Christensen (2002, p. 54). |

| 14 | In Plato’s Timaeus, Critias explains the forging of the world to Timaeus Hermocrates and Critias: “He began the division thus. First, he cut off one portion from the whole, next another, double of this. The third portion he made half as great again as the second, the thrice as great as the first, the fourth double of the second, the fifth three times the third, the sixth eight times, the seventh twenty-seven times the first. Then he proceeded to fill up the intervals of the double and the triple, still cutting off portions as before and inserting them in these intervals, so that in each interval there were two middle terms, the one exceeding and being exceeded by the same part of the extremes, the other exceeding and being exceeded by an equal number. These links gave rise to intervals of three to two, four to three, and nine to eight within the old intervals. So he filled up all the intervals of four to three with the interval of the nine to eight, leaving in each case a fraction such that the interval determined by it represented by the ratio 256 to 243. By this time, the blend from which he was cutting off these portions was last exhausted”. See Plato (1929, pp. 35b–36b, 31–32). For commentaries on the harmonious structure of the world see: Macdonald (1937, pp. 59–116); Lippman (1964, pp. 1–44); McClain (1978, pp. 57–70); Pelosi (2010, pp. 68–89). |

| 15 | On Nancy’s timbre see Janus, “Listening: Jean-Luc Nancy and the ‘Anti-Ocular’ Turn in Continental Philosophy and Critical Theory”, pp. 191–92. |

| 16 | “That there is no sense in addition to the five—sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch—may be established by the following considerations:—We in fact have sensation of everything of which touch can provide us sensation (for all the qualities of the tangible qua tangible are perceived by us through touch); and absence of a sense necessarily involves absence of a sense-organ; and all objects that we perceive by immediate contact with them are perceptible by touch”. De Anima, book 3, 425a15–20, The Complete Works of Aristotle, edited by Jonathan Barnes, vol. I (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1984), 675. On the separation of the Arts and their haptic contingency see Landes (2007, pp. 80–92). Finally and decisively, Jacques Derrida’s account of the Aristotelean Nancy’s and his haptic interruption, (Derrida 2005). |

| 17 | Interestingly Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring (1913; the same year of Russolo’s noise expositions) transformed classical rhythmic structure. The score experiments with tonality, metre, rhythm, stress, and dissonance. Interestingly, the piece was the third score composed for art critic and founder of the Ballets Russes Sergei Diaghilev. The first composition for The Firebird was premiered in 1910, the second was Petrushka in 1911. In 1915 Diaghilev convinced Stravinsky to visit Milan to hear Russolo’s noise machines. “The evening in the salon of Marinetti—casa rossa, Corso Venezia, Milam—there was a meeting of the Futurist musicians, all of whom were present: Luigi Russolo, Balilla Pratella, Igor Stravinsky (who came especially from Lucerne), Prokofiev, Diaghilev (director of those Russian ballets that had become a choreographic epidemic), Massine (first ballerina), an exceptional Slavic pianist whose name construe who can, made up of difficult consonants, neither known nor written nor pronounced… the major attraction was Luigi Russolo with his twenty Intonarumori. Stravinsky wanted to have an exact idea of these bizarre new instruments, and, possibly insert two or three in the already diabolic scores of his ballets… A crackler crackled with a thousand sparkles like a fiery torrent. Stravinsky gushed emitting a syllable of crazy joy, leaped up from the couch of which he seemed a spring. Then a rustler rustled like petticoats of winter silk, like leaves in April, like sea rending summer. The frenzied composer tried to find on the piano that prodigious onomatopoetic sound, in vein proved the semitones of his avid digits while the ballerina moved the legs of his craft”. Payton (1976, pp. 28–29). |

| 18 | “It stayed/Where I saw it/Then it moved a fraction/To the left and then twice that/Distance again further and fur-ther//It/Disappeared/Then just faintly/A corner of it just a fraction/Was visible if you peered/Very very closely/And just as/quietly/it was/gone”. Snow composed this poem in 1957. He was there to alter our perceptual manners, our cadence, our tangible relations to ourselves and to others. This piece, written from a distance of ocean and seas, is my adieu to a master artist who recently died. |

References

- Ammann, Peter J. 1967. The Musical Theory and Philosophy of Robert Fludd. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 30: 198–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccioni, Umberto, Carra Carlo, Russolo Luigi, Balla Giacomo, and Gino Severini. 1910. Manifesto of Futurist Painters. Poesia, April 11. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Barclay, ed. 1981–1982. The Noise of Luigi Russolo. Perspectives of New Music 20: 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chapin, Keith, and Andrew H. Clark, eds. 2013. Speaking of Music: Addressing the Sonorous. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Thomas. 2002. The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1973. Speech and Phenomena: And Other Essays on Husserl’s Theory of Signs. Translated by David B. Allison, and Newton Garver. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 2005. On Touching—Jean-Luc Nancy. Translated by Christine Irizarry. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Godwin, Joscelyn, ed. 1989. Cosmic Music: Musical Keys to the Interpretation of Reality. Rochester: Inner Traditions. [Google Scholar]

- Godwin, Joscelyn. 1982. The Revival of Speculative Music. The Musical Quarterly 68: 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Roger Mathew. 2009. Review: Jean-Luc Nancy’s ‘Listening’. Journal of the American Musicological Society 62: 748–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayon, Adi Louria. 2022. Nancy’s Pleasure in Kant’s Agitation. Maimonides Review of Philosophy and Religion 1: 174–208. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1971. The Origin of the Work of Art’ in Poetry, Language, Thought. Translated by Albert Hofstadter. New York: Harper and Row, pp. 41, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Heller-Roazen, Daniel. 2011. The Fifth Hammer: Pythagoras and the Disharmony of the World. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hickmott, Sarah. 2015. (En) Corps Sonore: Jean-Luc Nancy’s ‘Sonotropism’. French Studies 69: 484–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janus, Adrienne. 2011. Listening: Jean-Luc Nancy and the ‘Anti-Ocular’ Turn in Continental Philosophy and Critical Theory. Comparative Literature 63: 182–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, Martin. 1993. Downcast Eyes: The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-Century French Thought. Berkeley: Berkeley Univerity Press, pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, Douglas. 2001. Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, Brian. 2012. Jean-Luc Nancy and the Subject Listening. Contemporary Music Review 31: 442, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komel, Mirt. 2016. A Touchy Subject: The Tactile Metaphor of Touch. Druzboslovne Razprave 32: 119–20, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Landes, Donald A. 2007. Le Toucher and the Corpus of Tact: Exploring Touch and Technicity with Jacques Derrida and Jean-Luc Nancy. L’Esprit Créateur 47: 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippman, Edward A. 1964. Musical Thought in Ancient Greece. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, Cornford Francis. 1937. Plato’s Cosmology: The Timaeus of Plato. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, pp. 59–116. [Google Scholar]

- Magnus, Bern. 1970. Heidegger’s Metahistory of Philosophy: Amor fati, Being and Truth. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. 2006. F. T. Marinetti: Critical Writings. Edited by Günter Berghaus. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, pp. 377–82. [Google Scholar]

- McClain, Ernest G. 1978. The Pythagorean Plato: Prelude to the Song Itself. Stony Brook: N. Hays, pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. 1996. Why Are There Several Arts and Not Just One? (Conversation on the Plurality of Worlds). In The Muses. Translated by Peggy Kamuf. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. 2007a. Listening. Translated by Charlotte Mandell. New York: Fordham University Press, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. 2007b. The Creation of the World or Globalization. Translated by François Raffoul, and David Pettigrew. Albany: Suny Press, p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. 2008a. Corpus. Translated by Richard A. Rand. New York: Fordham University Press, p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. 2008b. The Discourse of the Syncope: Logodaedalus. Translated by Saul Anton. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Payton, Rodney J. 1976. The Music of Futurism: Concerts and Polemics. The Musical Quarterly 62: 28–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosi, Francesco. 2010. Plato on Music, Soul and Body. Translated by Sophie Henderson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 68–89. [Google Scholar]

- Plato. 1929. Timaeus. In Plato: Timaeus and Critias. Translated by Alfred Edward Taylor. London: Methuen & Co. LTD., pp. 31–32, 35b–36b. [Google Scholar]

- Rorty, Richard. 1979. Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Charles. 1998. The Frontiers of Meaning: Three Informal Lectures on Music. London: Kahn and Averill, pp. 13, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Alison. 2007. The Aesthetic Paths of Philosophy: Presentation in Kant, Lacoue-Labarthe, and Nancy. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 134–63. [Google Scholar]

- Russolo, Luigi. 1986. The Art of Noises: Futurist Manifesto. Translated by Barcaly Brown. New York: Pendragon Press, pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Scherzinger, Martin. 2012. “On Sonotropism”. Contemporary Music Review 31: 345–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Marius. 1957. New Oxford History of Music. London: Oxford University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Marius. 1959. Origin of the Symbol in the Spirit of Music. Diogenes 7: 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, Michael. 1994. Tap. In The Michael Snow Project: The Collected Writings of Michael Snow. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, p. 49. First published 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Vattano, Laura. 2021. “Russolo’s ‘Il risveglio di una città’: A Fragment for and Aesthetic of Noise”. In Arts of Incompletion: Fragments in Words and Music. Edited by Bernhart and Axel Englund. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Voegelin, Salomé. 2019. Sonic Materialism: Hearing the Arche-Sonic. In The Oxford Handbook of Sound and Imagination. Edited by Mark Grimshaw, Mads Walther-Hansen and Martin Knakkergaard. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 2, p. 560. [Google Scholar]

- Weibel, Peter, ed. 2019. Sound Art: Sound as a Medium of Art. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Louria Hayon, A. Sonorous Touches: Listening to Jean-Luc Nancy’s Transimmanent Rhythms. Arts 2023, 12, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050209

Louria Hayon A. Sonorous Touches: Listening to Jean-Luc Nancy’s Transimmanent Rhythms. Arts. 2023; 12(5):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050209

Chicago/Turabian StyleLouria Hayon, Adi. 2023. "Sonorous Touches: Listening to Jean-Luc Nancy’s Transimmanent Rhythms" Arts 12, no. 5: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050209

APA StyleLouria Hayon, A. (2023). Sonorous Touches: Listening to Jean-Luc Nancy’s Transimmanent Rhythms. Arts, 12(5), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050209