1. Introduction

Yu Youhan 余友涵 (b. 1943, Shanghai) has been commended as one of the ‘most subtle and interesting’ contemporary Chinese artists (

Collings 2015, p. 5). Having gained recognition by a wide audience, he has regularly participated in numerous exhibitions around the globe, such as

Mahjong (2005) in Bern, Switzerland,

‘85 New Wave (2007) in Beijing, China, and

Out of Shanghai (2009) in Ottendorf, Germany. Trained at Beijing’s Central Academy of Arts and Design (now the Academy of Arts and Design at Tsinghua University), Yu has produced artworks in various styles and techniques throughout his career, ranging from landscape paintings to pop paintings and geometrical abstracts. What he has still received inadequate acknowledgement for by scholars, however, are his vibrant pop works, which incorporate imagery from socialist China under Mao Zedong 毛泽东 (1893–1976), the former Chairman of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Communist Party of China.

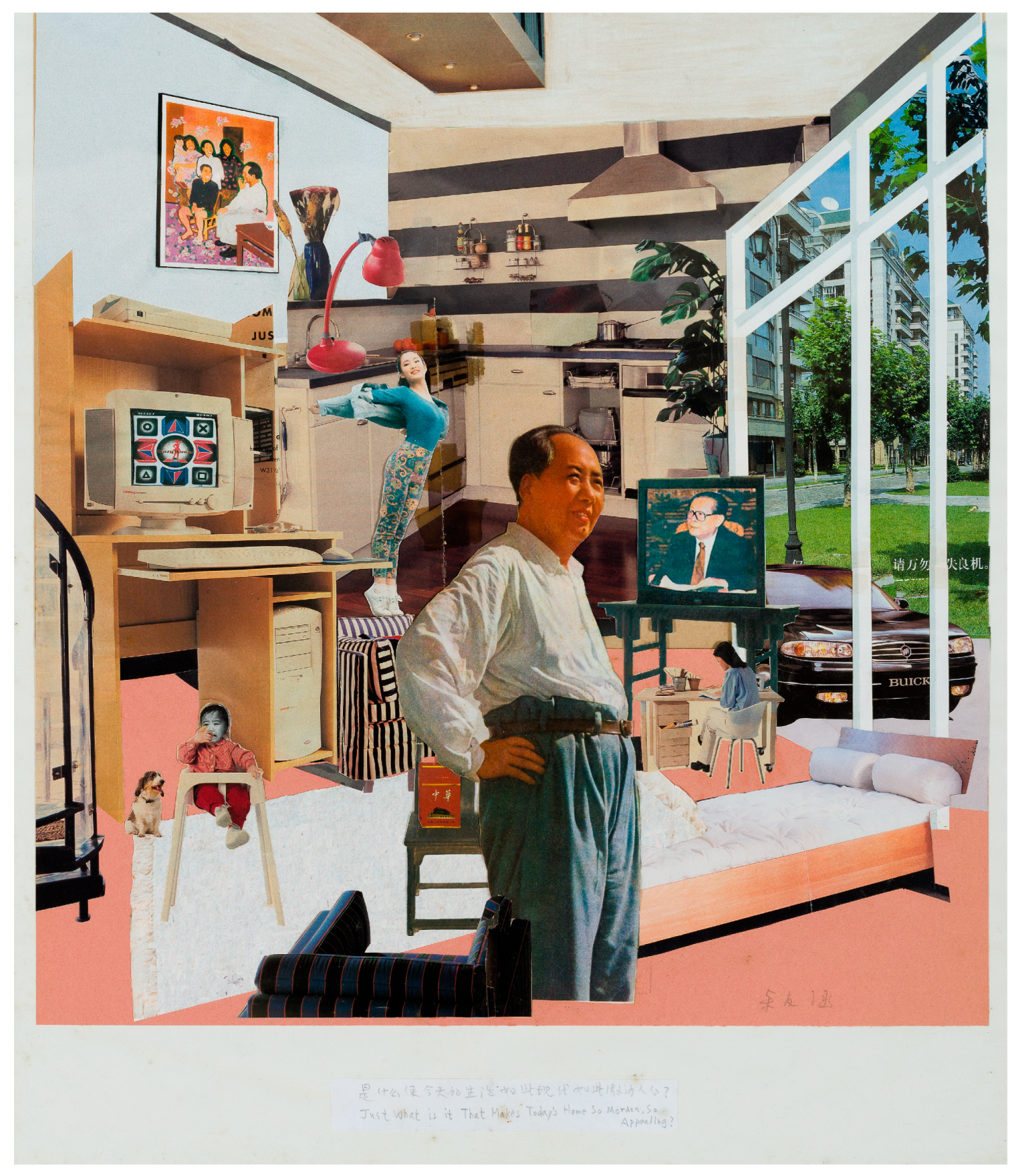

This article aims to investigate the way in which

Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Modern, So Appealing?1 (2000) can be classified or grouped with his Political Pop works. It attempts to unravel the applications of appropriation in three selected works by (1) locating the source of appropriated imagery, (2) examining their extraction and manipulation, and (3) considering the effect of their recontextualisation. Based on an extensive formal analysis of the artworks and a critical examination of published interviews, books and journal articles, this article asserts that Yu’s later pop works from the 2000s fit well into the development of the artist and epitomise his contribution to the diversity of Political Pop.

The term Political Pop (

zhengzhi bopu 政治波普), with which Yu’s paintings from the late 1980s to 1990s are commonly associated, was coined in 1992 by Chinese art critic Li Xianting. In his attempt to theorise Chinese art in the aftermath of the forcibly suppressed protests on Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989, Li argues that apathy and deconstruction constitute major trends in post-1989 art and account for the emergence of the movements of Cynical Realism and Political Pop (

Li 2010, p. 164). Artworks associated with the latter are claimed to ‘deconstruct the most influential personages and political events in China in a humorous way’ (ibid.). Similarly, art historian Paul Gladston suggests that Political Pop’s distinct characteristics are ‘deconstructivist juxtapositions of images from the Maoist period with others taken from differing sources, including imagery associated with global capitalism’ (

Gladston 2014, p. 185). What further complicates the understanding of Political Pop is its theorisation from a transnational perspective, an aspect commonly overlooked in favour of a mere local point of view. Art historian Martina Köppel-Yang offers an insightful account of the aesthetic strategies employed in Political Pop that is informed by the style’s conception as a distinctive and autonomous derivative of Euro-American Pop art (

Köppel-Yang 2007). More recently, Svetlana Kharchenkova and Olav Velthuis provided an evaluative biography of Cynical Realism and Political Pop that argues that the misunderstanding of these styles by foreign audiences as highly politicised was a key factor in their artistic and commercial success (

Kharchenkova and Velthuis 2015, p. 112). The authors further assert that critical voices such as Gao Minglu, Wang Hui and Pi Li, who argue against the ‘authentic, original character and [the] political engagement’ of Cynical Realist and Political Pop works (ibid., pp. 123–24), remain partly unaddressed. The four commentaries above illustrate the development from a rather vague and broad definition to a more precise understanding of Political Pop.

2 However, all definitions fail to uncover the complex sources of imagery employed in this style of art or account for the technical aspects involved in it.

Yu’s vast body of Political Pop works underlines the fact that Chinese artists critically engaged with their country’s socialist past after the late 1980s. However, his later pop work

Just What Is It (…)? (2000) demonstrates significant differences in terms of composition and technique, and overtly references Richard Hamilton’s (1922–2011) almost identically titled collage from 1956 (

Figure 1). As Yu produced pop works for more than two decades, one cannot help but wonder if the aforementioned photomontage marks the end of pop in the artist’s practice. Has Political Pop, one of the first movements of contemporary Chinese art that gained increasing attention from foreign audiences, become obsolete after all? Have Yu’s pop works become a mere copy-and-paste practice that might indicate his lack of originality? Or is the abrupt change in style perhaps an attempt to reignite the interest of the art market in which Political Pop was once in high demand?

Despite his international recognition, Yu has only been briefly addressed by art critics and art historians. Among the few scholars who have commented on his works, Li identified printed cloth and New Year’s pictures as the sources of inspiration behind Yu’s depictions of Mao and further argued that these folk art elements resonate with Mao’s theory of art and literature, thus enhancing the criticality of the artist’s work (

Li 2010, p. 164). Although he did not offer substantial evidence to support his claims, Li’s account contributes to an initial stylistic and technical classification. Similarly, Julia Frances Andrews and Kuiyi Shen identified the compositional elements in Yu’s Pop paintings, albeit briefly and without much detail. They locate the sources of pre-existing imagery in propaganda images that were manipulated and thus discharged of their original meaning in Yu’s works (

Andrews and Shen 2012, p. 261). Art historian Francesca Dal Lago contributed to the scholarship on Yu by examining Mao as a constructed image, as opposed to a person, and its deployment in Chinese contemporary art practices. Similar to several of his fellow artists, it is asserted that Yu employed the constructed image of Mao as a ‘discursive space’ of negotiation during a time of rapid economic, political and social transformations (

Dal Lago 1999). Among all views considered, Gladston’s theorisation is arguably the most comprehensive to date. He conceives Yu’s Mao paintings as works that oscillate between ‘revolutionary’ and ‘deconstructivist’ pursuits (

Gladston 2015, p. 52). In other words, the artist’s strategic use of Mao as an image is argued to revisit the aspirations for progress and harmony promised during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), while the image’s manipulation simultaneously causes an extrication from its historical context.

The studies outlined above aim to illustrate the current scholarship on Yu and his Political Pop works incorporating the image of Mao. Despite the scholars’ contributions regarding composition, technique and effects, they fail to offer a comprehensive analysis of Yu’s works. This article aims to fill this gap and offers a semiotic analysis of three of Yu’s Political Pop works produced between 1990 and 2000. These works were selected based on their observed ability to represent Yu’s technical versatility and capture his artistic development throughout the decade.

Apart from the categories of composition, colour pallet, iconography, and the context of production and reception, the formal analyses in this article also highlight the strategies of appropriation employed in Yu’s works. This last aspect signifies the conscious act of utilising and manipulating pre-existing imagery that can be observed in various disciplines of the arts. Appropriation serves as a framework to explore questions about originality, signification and the stability of meaning.

3 2. Talking with Hunan Peasants (1990/1991)

The year 1989 played a pivotal role in Chinese national history. Among the many monumental events that took place at this time, the aforementioned protests for democracy on Tiananmen Square in June 1989 are considered a turning point in the country’s cultural history (

Lu 1997, p. 112). Contrary to the enthusiasm and idealism expressed by the artists of the mid-1980s, artworks produced in the early 1990s are claimed to convey emotions of ‘apathy’, ‘roguish humour’ and cynicism, among others (

Li 2010, p. 158). Furthermore, the changing political climate, coupled with restrictions on the public display of art, as well as the effects of commercialisation and globalisation, are believed to have significantly shaped the art of the early 1990s (

Wu et al. 2010, p. 154). The development of Political Pop from a local movement to a global phenomenon, for instance, is indebted to increasing flows of communication and ideas across national boundaries and an art market that craved supposedly politically subversive art that resembled Euro-American Pop Art.

This section will examine Yu’s painting

Talking with Hunan Peasants4, which was produced between 1990 and 1991 (

Figure 2). Except for its public display at the

China Avantgarde (1993) exhibition in Berlin, Germany, in 1993, and the artist’s first solo exhibition

Yi Ban 一斑 (

One Spot) in Beijing, China, in 2013, little has been recorded about the exhibition history of this work. Like many other contemporary artists, such as Wang Guangyi 王广义 (b. 1947, Harbin), Liu Wei 刘炜 (b. 1965, Beijing), Li Shan 李山 (b. 1942, Lanxi), Zhang Hongtu 张宏图 (b. 1943, Pingliang) and Liu Dahong 刘大鸿 (b. 1962, Qingdao), it is the constructed and manipulated image of Mao that forms the key aspect in their work and serves as a means of renegotiating China’s socialist past through the language of Political Pop.

5 2.1. Image Description

As the title suggests, this painting depicts Chairman Mao casually conversing with peasants in his home province of Hunan. Although the facial expression is only diagrammatic, the wide high-waisted trousers, tucked white shirt and idiosyncratic hairline clearly identify the figure on the right as Mao. On the left side, three standing women are depicted, with one holding a small child in her arms. A man is sitting in a wooden chair in front of them, holding a cigarette in his hands. Even though the bowl left behind on the table and the simple clothing suggest a rather casual family gathering in the peasants’ meagre living room, their big smiles and gazes indicate a moment of appreciation at being visited by an honoured guest.

One of the key formal features of this painting is the outlining. While most of the heads and upper bodies are outlined in bright green, other contours are outlined in black, blue and bright red. Due to the inconsistency in application (in terms of thickness and colour), these renditions may appear simply arbitrary. In terms of composition, however, the outlines unify the figures and distinguish them from the background’s colourful and repetitive motifs. The divide between figure and ground is further enhanced by a cold-warm contrast with the immediate background. This cut-out quality also highlights the aspect of limited visual depth. Even though the shading of the figures creates three-dimensionality to a limited extent, most of the painting is dominated by plane surfaces, signalling flatness.

According to art historian Christine Poggi, the process of incorporating and manipulating objects from everyday life, which is a key aspect of collages, is argued to highlight the heterogeneity of materials assembled on the painting support (

Poggi 1992, p. 254). In line with art critic and art theorist Rosalind Krauss, Poggi suggests that the collage accentuates the heterogeneity between ‘figure and ground’ (ibid., p. 256). Even though these claims might not be transferrable to a late-twentieth-century context in China, Poggi’s precise observations serve as a useful tool for describing the formal qualities of

Talking with Hunan Peasants (1990/1991). Though the painting is not a collage in the technical sense, it does demonstrate a collage-like aspect, an attempt to play with different layers of depth.

2.2. Appropriation: Photographic Origin and Manipulation

One crucial aspect of this work that has been insufficiently considered so far is the use of appropriation, as the painting does not solely represent an expression of Yu’s vivid imagination nor is it entirely copied. Evidence suggests that the overall composition is based on an official photograph, presumably taken in 1959, which captured Mao’s visit to a peasant family in his hometown of Shaoshan in Hunan province.

6 This conclusion is based on its reproduction in the November/December 1976 issue of the

China Reconstructs magazine (

China Welfare Institute 1976, p. 57). In commemoration of Mao, who had passed away in September of the same year, the magazine dedicated the double issue entirely to him, including various black-and-white photographs (

Figure 3).

The title of the artwork only indicates a slight similarity to the original photograph’s title. Although not completely different in terms of its content, the original title’s implication is tremendously reduced, while it still reflects the painting’s intended theme. In terms of perspective and proportions, the similarity between the original and the artwork is clearly visible. To achieve this level of similarity, it appears extremely probable that Yu employed mechanical tools to extract the outlines and translate them onto the canvas. The reproduction in China Reconstructs (1976) suggests that the original photograph does not exceed the painting’s rather large dimensions of 164 × 117 cm. This indicates that Yu’s manipulation of the photograph did indeed involve an enlargement in size, while the same scale was maintained. With regard to the composition, nearly every figure and object in the photograph was adopted without any alteration. Among the few exceptions is the table, the dent and scratches on which were dropped, transforming it into a flawless surface. Similarly, the indefinable brown area on the wall was straightened in the artwork.

Another aspect of the photograph’s manipulation are the flower motifs that were repeatedly added to the bottom half of the painting but incorporated in the upper half and on the clothing as well, such as the pale green and pink flowers on Mao’s white shirt. These motifs vary in shape and size, as well as colour, and are consistently outlined in either white or red. They are mostly painted on the image plane, regardless of the background, thus appearing to be rather decorative. Scholars agree on these motifs’ identification as elements derived from Chinese folk art (

Li 1993, p. xxi;

Lu 1997, p. 120). However, they fail to provide any further analysis of this rendition. Although most blossoms are highly stylised and barely recognisable, the larger ones exhibit a striking similarity to peonies, commonly considered the ‘flower of the emperor’ in Chinese culture, a symbol of ‘beauty’, ‘wealth’ and ‘good fortune’ (

Fang 2004, p. 147). Flowers have always occupied a special place in Chinese iconography, representing not only growth and power, but also fragility, transience, and the struggle of the working class. Especially in propaganda posters created during the Cultural Revolution, sunflowers came to represent the Chinese people who, like flower heads, oriented themselves towards the sun—an icon that was often coupled with an image of Chairman Mao. It is worth noting that the flowers in

Talking with Hunan Peasants (1990/1991) do not evoke the revolutionary spirit they once represented. Rather, they have become decorative patterns that render Mao one with the ordinary people.

Given the low resolution and quality of the black-and-white photograph, Yu’s colour manipulation arguably causes one of the most effective visible detachments from the photograph and confers a certain autonomy on the artwork. While the colour grading is deliberately copied, the choice of colour constitutes a considerable part of Yu’s transformation. Otherwise, almost entirely in accordance with the colour grading, Yu adopts a strong violet colour for the ground that further highlights the colour contrasts and segmentation.

In conclusion,

Talking with Hunan Peasants (1990/1991) emphasises Mao’s closeness to the ordinary people, the peasants and his hometown. From a technical perspective, it highlights both a number of alterations of the official photograph, as well as adoptions of varying degrees. This, in turn, challenges the autonomy of the photograph due to its reproducibility and raises questions regarding the blurring notions of the ‘original’ and the ‘replica’. Art historian Alex Potts’ essay on mimesis in European Pop art and New Realist art after 1945 offers some useful terminology in this regard. Contrary to the common classification as readymade qualities, Potts proposes a distinction between the found image and the ‘as found’ quality of the image after its manipulation: while preserving the basic characteristics, and therefore the authenticity, of the image, according to Potts, the process of manipulation and transformation results in the development of unique, autonomous features (

Potts 2014). Although Potts fails to sufficiently take into account the degrees of ‘as found’ qualities, this terminology facilitates the understanding of the powerful effects of appropriation and their contribution to the creation of an independent, unique work of art.

2.3. Interpretation

As related in an interview between Yu Youhan and Yu-Chieh Li held in 2015, the experiences of growing up in a middle-class family in the 1940s, serving the People’s Liberation Army in the 1960s and facing the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution highly informed Yu’s artistic practice (

Li and Yu 2015). When Li questioned him as to whether he experienced any changes in his admiration for Mao, the most prominent subject matter of his Pop paintings, Yu cautiously replied:

We were disappointed by him. My father read in the newspaper that many cadres were taken down, including Liu Shaoqi, who was the president. (…) What he said to me actually represented public opinion: why would Mao take down all the Party leaders? (…) We were very confused by the fact that the Communists could not even explain to their people why the party was good.

(ibid.)

Therefore,

Talking with Hunan Peasants (1990/1991) not only represents a manipulated photograph or a recontextualised episode from the past, but is also a critical expression of Yu’s personal experiences during an era of rapid political and social changes.

Contrary to the solely biographic interpretation, Francesca Dal Lago emphasises the possible association with the premises of Socialist Realism and Revolutionary Realism during the Mao era. She suggests that the colour patterns function as exaggerations of folk art, asserting that the flatness of the figures and background reflects the assimilating effects of propaganda, thus parodying the premise of ‘art for the masses’ (

Dal Lago 1999, pp. 51–52). Even though these claims would benefit from more substantial evidence, Dal Lago’s observations achieve a compelling association between Yu’s artistic expression and the inherently political nature of the photograph’s origin. Her consideration of the parodic effects of the appropriated photograph is a valid point that requires further study.

Parody has been a common means in the arts, including in modern and contemporary art and various other disciplines, such as film and literature. According to

Michele Hannoosh (

1989), parody may be defined as ‘a comical retelling and transformation of another text’ (p. 113). Simply put, parody is equivalent to ‘repetition with difference’ or ‘the law and its [conscious] transgression’ (

Hutcheon 2000, p. 101). Contrary to the pejorative perception of stealing or mockery,

Hannoosh (

1989) emphasises the self-reflexivity of parody effected due to the parodist’s nature as both the ‘reader’ and ‘author’, as well as its self-criticality derived from its consciousness of possibly being similarly parodied (pp. 113–14). In this regard, it may be concluded that the photograph’s manipulation in

Talking with Hunan Peasants (1990/1991) constitutes a conscious act aimed at achieving exaggeration and ridicule through which the artist inevitably self-parodies his personal attitude towards Mao, rather than the subject matter itself.

This, in turn, also affects the interpretation of the flower motifs and contributes to the work’s polysemy: although originally intended to express power (

Li and Yu 2015), the artist’s obsessive depiction of flowers allows for multiple compelling interpretations, ranging from their association with folk art and propaganda posters through to as a means of attaining exaggeration. Considering the work’s parodic effects, the flower motifs no longer unambiguously signify the idea of peonies or power. Rather, their meaning is destabilised, as they become a signifier of the artist’s self-criticism: Yu’s personal reflection about his past.

3. Waving Mao 2 (1995)

The artistic landscape of the mid-1990s demonstrated a continuation and further development of commercialisation and globalisation. According to Wu et al., the changing conception of what art constitutes is reflected in its terminology: once termed ‘modern’ (

xiandai 现代) in the 1980s, art was rather referred to as ‘contemporary’ (

dangdai 当代) or ‘experimental’ (

shiyan 实验) by the mid-1990s (

Wu et al. 2010, p. 184). These changes are argued to have taken place in parallel with the integration of Chinese art in the international art world, which are regarded as an expanding global phenomenon rather than a mere local one (ibid., p. 184). Artists at that time experimented with new media (installation, photography, film or performance) in search of appropriate means that would best reflect their state of mind. In this regard, Yu’s continued production of oil and acrylic paintings does not reflect mainstream trends and may thus allow a more differentiated view to be gained on that period.

As the title suggests,

Waving Mao 2 (1995) (

Figure 4) is the second version of a work that the artist had produced five years earlier.

7 The most prominent difference is arguably the vast number of three-petal white trilliums (lat.

trillium grandiflorum) that were replaced with different kinds of flowers in the 1995 version. While the earlier version from 1990 has been displayed at major international exhibitions such as

Mao Goes Pop: China Post-1989 (1993) in Sydney, Australia, and

China’s New Art, Post-89 (1993) in Hong Kong, limited information is available regarding the exhibition history of

Waving Mao 2 (1995). However, one crucial aspect that has not been addressed yet might explain why the later version has attracted so little attention: at the bottom right of the painting, the following hand-written addition is appended: ‘Made for Miss Vivienne Tam’ (

ying Tan Yanyu nüshi zhi yao er zuo 应譚燕玉女士之邀而作). The addendum indicates that the work was a commission for the New York–based fashion designer Vivienne Tam (b. 1957, Guangzhou), reflecting the progressive commodification of art in the 1990s.

3.1. Image Description

This medium-scale acrylic painting shows a statue-like depiction of Mao against flat colour panels, juxtaposed with gestural brushstrokes and stylised flower heads on a colourful background. The focal area in the centre consists of a black statue whose silhouette has been outlined in white with thick brushstrokes, decorated with a varied assortment of flower petals and blossoms. As indicated by the title, this figure may be identified as a profile view of Mao with a raised arm. This statue is surrounded by a dark blue rectangle that is framed by a broken thick red outline and orange flower heads. Juxtaposed with these rather dark, outlined shapes is the rest of the painting, in which white, yellow, orange and magenta have been applied in an unsystematic manner, resulting in a vibrant patchwork of warm colours. This playful arrangement is complemented by large flower heads in thick black or orange outline that are densely applied.

One of the most prominent formal features is the painting’s partial dissolution of visual depth. Even though depth is created through the statue’s overlap with its immediate background, the suggested three-dimensionality of the statue’s base, and the gradient colour patterns underneath the flower motifs, other features serve to reverse this effect. The refusal of a constructed perspective, the plain colouring as well as minimal colour grading contribute to the overall impression of flatness. The distinction between a rather dark centre against the bright background is further enhanced by the painting’s deviations in colours, shapes and saturation. Furthermore, as compared to the precise and opaque application of paint in the centre, the remaining work depicts haphazardly applied brushstrokes, rough colour shifts, and clearly visible horizontal and vertical brushstrokes as well as paint drips.

3.2. Appropriation: Visual Origins and Manipulation

While the close adoption of the subject matter, composition and colour grading of a 1959 photograph was observed in

Talking with Hunan Peasants (1990/1991), we find the distinct statue-like depiction of Mao across various sources. Based on a comparison between painting, photography and sculpture, it appears reasonable to assume that the distinct posture, gesture and clothing are well established features across different kinds of media and indeed mirror the iconicity of Mao: Tang Xiaohe’s 唐小禾 (b. 1941, Wuhan) painting

Strive Forward in Wind and Tides (1971), for instance, depicts Mao in a long white overcoat, raising his right arm in salutation while facing heavy wind and crashing waves at a harbour.

8 Similarly, the November/December 1976 issue of

China Reconstructs featured a black-and-white photograph titled

Chairman Mao Reviewing for the First Time the Mighty Army of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution from Tien An Men Gate, 18 August 1966.

9 As the detailed title suggests, it depicts Mao from a frog’s eye view, leaning on the railing of the Tiananmen gate while stretching out his right arm to greet the implied Red Guards on the ground, a mass movement of students mobilised during the Cultural Revolution. Likewise, these features were translated into many statues, such as the monumental

Long Live the Victory of Mao Zedong Thought statue, erected on Zhongshan Square in Shenyang, the Mao statue at the Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications or on Tianfu Square in Chengdu (

Figure 5). In contrast to

Talking with Hunan Peasants (1990/1991),

Waving Mao 2 (1995) cannot be said to be appropriating one specific image, but rather multiple images of Mao that have been constructed in different media and established their own autonomy over time.

The conscious manipulation of the image involved a thick white outlining of the statue that accentuates its shape and confers a certain cut-out quality, a procedure similar to that observed in

Talking with Hunan Peasants (1990/1991). Furthermore, the black colouring of the entire figure contributes to a high level of abstraction. Interestingly, the overall shape of the Mao statue suggests a profile-view depiction. The outlines of the base, however, suggest a bird’s eye view from the front right, thus demonstrating Yu’s play with the illusion of perspective. Another prominent aspect is the multitude of stylised flower heads painted onto the black surface, of which three main types can be distinguished. Most frequent are the five-petal plum blossom (lat.

prunus mume), a flower species common in Asia. In Chinese culture, it has various meanings, and may symbolise both longevity as well as the ‘survival of hardships, endurance, and perseverance’ (

Fang 2004, p. 152). The second type is the three-petal white trillium from the order

Liliales, a flower that was previously introduced as the primary distinctive feature between the

Waving Mao versions. The last type is the chrysanthemum, which is native to Asia and encompasses a variety of different implications. Besides its typical connotation of ‘joviality’ in Chinese culture, the chrysanthemum is also believed to represent the ideas of ‘a pleasant life, generosity, and retirement from public spaces’ (ibid., p. 43). This flower has been added to the background in places, which is otherwise dominated by peonies. In conclusion, the juxtaposition of the Mao statue with several different flowers, whose symbolism is firmly rooted in Chinese culture, creates complex levels of meaning. However, it remains questionable whether an uninformed viewer could comprehend this complex signification. It appears more reasonable to assume that it is the function of the flowers in relation to the black statue that needs to be given due attention.

3.3. Interpretation

While

Collings (

2015) claims that ‘Mao means something, mostly good things’ (p. 9) to the artist, Yu Youhan employed a more differentiated language to describe his stance and intention of creating these Pop works. He offered the following explanation in an interview with Paul Gladston in 2009:

When I painted the Mao series, though I cherished the Maoist period, I also held more reflective and critical feelings about the betrayal of socialism. (…) As for my feelings towards Mao, though I no longer admire him as I used to during the Cultural Revolution, I don’t think we should deny him totally. (…) If I can make some contribution to Chinese society through my paintings, I would like to pull down Mao’s position as a saint and make him into an ordinary person. But what I don’t want to do is to demonize him.

In line with the artist’s intentions of critical reflection and deconstructing deification, the transformation to a flat statue veiled by a multitude of flowers appears to be a central aspect in

Waving Mao 2 (1995). This subversive quality is similarly affirmed by the scholar Sheldon Hsiao-peng

Lu (

1997), who argues that Mao as a worshipped icon during the Cultural Revolution is transformed into flatness, deprived of ‘spatial or emotional depth’ (p. 120). However, his argument requires further elaboration as to the way in which this flatness was constructed.

The flatness and distance, it appears, are caused by the repetitive application of flower motifs and their semantic abundance, thus creating a veil between the subject matter and the viewer. A similar effect was observed by Chengfeng Gu (

[1996] 2010) in Wang Guangyi’s

Mao Zedong: Black Grid (1988) (p. 176).

10 As Köppel-Yang suggests, the grid superimposed on the standard portrait of Mao in Wang’s triptych facilitates its ‘objectification’ and in other works even acts as ‘the rational per se’ (

Köppel-Yang 2003, p. 158). She concludes that it is the apotheosis of a political figure, not Mao as a political figure, that

Mao Zedong: Black Grid (1988) comments on. Even though the properties of a rigid grid in Wang’s Mao series, including

Red Grid No. 2 (1989) (

Figure 6), and the chaotic flower patterns in Yu’s Mao series are not entirely comparable, they do perform similar functions. Therefore, it may be argued that the flower veil in

Waving Mao 2 (1995) serves to comment on the craze related to and the worship of an icon, which was observed so vividly in the 1990s as a part of the phenomenon termed ‘Mao fever’ (

Maore 毛热) (

Dal Lago 1999, p. 49). Mao fever can be seen as a form of collective memory and fetishisation of Mao’s legacy that swept through China across all generations and classes, characterised by the extensive production and consumption of Mao-related memorabilia, among others. The use of a distinct silhouette that has gained iconicity in various media further substantiates this conclusion and indicates that the focal point for interpretation is not constituted by the black statue but rather by the implied audience.

From a semiotic perspective, the manipulated icon of Mao no longer signifies Mao as a statue or Mao as a person. Rather, it becomes the signifier of a wave of ‘nostalgia’ (ibid., p. 49) observed in the 1990s. This evident change in signification indicates that the act of appropriation, which involved the deconstruction, manipulation and recontextualisation of pre-existing imagery, was successfully performed. It is this engagement with the societal climate that determines the artist’s criticality and challenges any potential claims of one-sided intentions.

5. Conclusions

This article offered new insights into the mechanics of signification in Yu Youhan’s pop works by examining the ways in which different kinds of imagery are appropriated, manipulated and recontextualised. The formal analyses identified the selected artworks as diverse yet cohesive representations of the artist’s body of work, having developed from the collage-like deconstruction of the flat image plane through highly abstract depictions to the multi-perspective montage of photographs. The origins of this pre-existing imagery range from official photographs to well-established iconography across various media (painting, photograph, sculpture), as well as iconic pop paintings, the artist’s earlier work and possibly reproductions of propaganda paintings and furniture catalogues.

In terms of manipulation, the three artworks exhibit different degrees of alteration. While the basic configuration of the original photograph was maintained in Talking with Hunan Peasants (1990/1991), alterations included its enlargement, minor changes in compositional elements, colour effects and the application of flower motifs. In Waving Mao 2 (1995), the use of pre-existing imagery is subtle, while the acts of manipulation are rather profound and encompass thick outlining, abstraction, a play with perspective, and the application of repetitive flower heads. The most insightful example of manual and photomechanical alterations is constituted by Just What Is It (…)? (2000), containing folding and cutting lines, multiple perspectives, and adoptions of Hamilton’s 1956 collage.

Even though the effects of recontextualisation vary greatly, all works are characteristic of shifts in signification. By emptying and recoding individual signifiers, the discussed works allow for new meanings. This semiotic perspective both illustrates the mechanisms of appropriation and helps explain the way in which Yu’s works gain autonomy. While Talking with Hunan Peasants (1990/1991) parodies the artist’s reflection of his own past, Waving Mao 2 (1995) offers a profound commentary on the societal climate of the 1990s. Just What Is It (…)? (2000), on the contrary, provides humorous critique both at an inherent level and a meta level. It not only questions the notion of modernity, aspects of commercialisation in present China, and political leadership, but also exposes covert feelings of marginalisation in an art world mostly dominated by Europe and North America. As Yu himself stated:

‘I like to express my thoughts through images of Mao Zedong. (…) During the Cultural Revolution, portraits of Mao were deified: they exuded a feeling of political passion and cultureless superstition. (…) My goal is to depict the figure of Mao in a new light’.

Based on these findings, this article counters the assumption that Yu’s copy-and-paste practice might indicate a lack of originality or even the decay of Political Pop, which had come to a halt in his practice by the early 2000s. The diverse acts of appropriation, which have been largely overlooked by scholars, functioned as the key elements in reaching this conclusion. The deconstruction of visual origins, and their deliberate manipulation and recontextualisation, are astute artistic strategies that reinforce the artist’s originality and criticality. Yu’s images of Mao are neither imbued with the same revolutionary spirit they exuded in propaganda art during the Cultural Revolution, nor do they express the same feeling of enthusiasm and nostalgia for Mao that was so vividly experienced during the 1990s. Yu’s iconic renderings of Mao in the style of Political Pop are different. Rather than being symptomatic of decay, it is the technical sophistication in his works that challenges an excessively simplistic conception of Political Pop that is accused of being uncritical and merely used for the generation of quick profits by a demanding art market.

As Yu’s works tend to depict historical events or refer to a particular point in time, scholars have suggested that they might be classified as a ‘contemporary [form] of history painting’ (

Gladston 2015, p. 13). However, the deliberate manipulation and recontextualisation challenge stable, official narratives usually expressed in history paintings. By emptying and recoding individual signifiers, Yu’s work blurs the line between fact and fiction and challenges stable narratives. Rather, this article underscores that the artist gave birth to a contemporary form of history painting, or rather an anti-history painting, in the style of Political Pop that refashions the cultural memory of China’s past.