Kubism™: Picasso, Trademarks and Bouillon Cube

Abstract

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | (Rabinow 2014, p. 173) See also (Apollinaire 1972, p. 258). |

| 2 | On the history of Maggi and its world-famous bouillon cube, see (Pivot 2002, especially 65–78). |

| 3 | Quoted in (Pivot 2002, p. 68) “Appellation necessaire” is a legal term of art addressed at length below. French courts had long established that terms such as extractum carnis or of meat were necessary and thus generic in relation to bouillon. See (Pouillet 1892, p. 75). |

| 4 | All trademark registrations were also published by the official bulletin of industrial and commercial property. See (BOPI 1909). |

| 5 | On the “Loi du 14 juillet 1909 sur les dessins et modèles,” see (Pouillet et al. 1911) The law was written for two- and three-dimensional industrial designs, not for packaging per se. In the nearly 1000 pages of the treatise, there is no discussion of packaging. Maggi was again pushing the envelope of the law. |

| 6 | See (Iskin 2014, p. 18). |

| 7 | See (Weiss 1994, pp. 62–65) See also (Chessel 1998, pp. 145–80). |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | (Hémard 1912a) Note the pseudo-Germanic spelling of “Pintur”: “Dans la Pintur Cube, exiger le cu.” The Germanic associations of KUB and Cubism would come to haunt the movement (as well as Maggi) when France entered into WWI against Germany. See (Cox 2000, pp. 268–72; Pivot 2002, pp. 76–78; Richardson 1996, pp. 352–53). |

| 12 | |

| 13 | See (Richardson 1996, p. 241). |

| 14 | See (Cousins 1989, pp. 397–98). |

| 15 | See (Robbins 1985, pp. 9–23). |

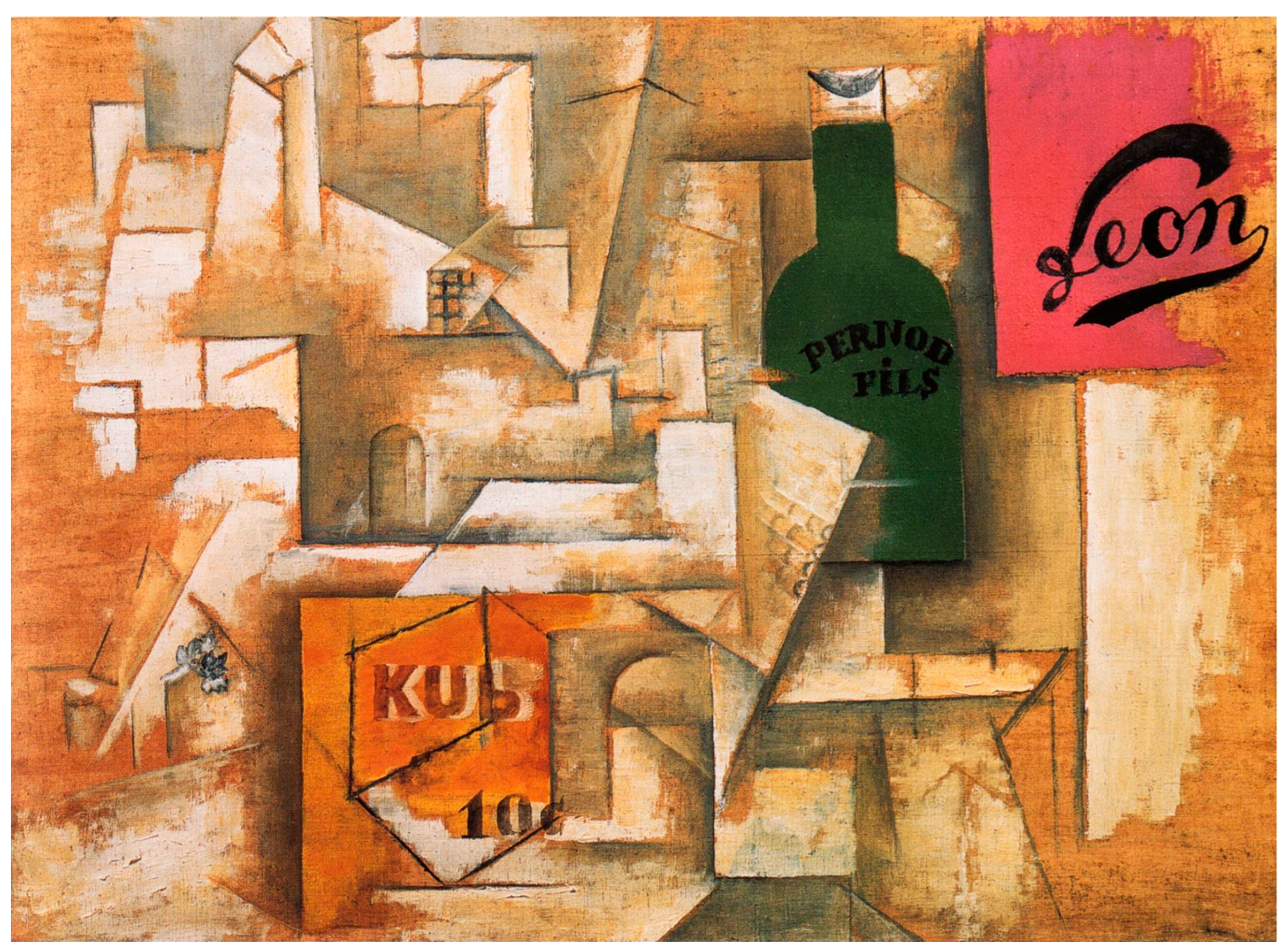

| 16 | Braque was the first to sign with Kahnweiler in 1912. Picasso waited until December of that year to sign a formal contract, ratifying their informal but potent working relationship. See (FitzGerald 1995, p. 34) On Kahnweiler’s strategic distancing of Picasso and Braque from the Salon Cubists, see (Richardson 1996, pp. 207–19) Noteworthy as well is the fact that, at the end of 1912, Kahnweiler sent Picasso’s small painting Le Bouillon Kub to the “Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition,” curated by Roger Fry for the Grafton Galleries in London, an exhibition that included works by Picasso and Braque, but no other would-be Cubists. |

| 17 | |

| 18 | The “Salon de la Section d’or” took place in October of 1912, around the publication date of Du “Cubisme”. (Gleizes and Metzinger 1912). |

| 19 | |

| 20 | See, for example, (Allart and Allart 1914, pp. 52–53; Coddington 1878, pp. 419–21, 32–33; Pouillet et al. 1912, pp. 62–67) Other jurisdictions were far less accommodating to the registration of the shape of packaging or products as trademarks. |

| 21 | Such “phenomenal transparency” would become a commonplace of Cubist criticism. See, for example, (Rowe and Slutzky 1963, p. 47). |

| 22 | For an overview, see (Browne 1898, pp. 274–79). |

| 23 | Among numerous examples, see (Barclay 1889, p. 120; Pelletier 1893, pp. 167–72; Pouillet et al. 1912, pp. 71–74). |

| 24 | I venture as much in the second chapter of my current book project: Art™: Modern Art, Authenticity, and Trademarks. For the “pre-history” of Picasso’s extensive engagement with the world’s “first” registered trademarks (those of Bass Ale), see (Elcott 2024, pp. 114–63). |

References

- Allart, Henri, and André Allart. 1914. Traité Théorique et Pratique des Marques de Fabrique et de Commerce. Paris: Rousseau. [Google Scholar]

- Apollinaire, Guillaume. 1911. La Vie anecdotique: Le Kub. Mercure de France 661. [Google Scholar]

- Apollinaire, Guillaume. 1972. Cubism. In Apollinaire on Art. Edited by LeRoy C. Breunig. Translated by Susan Suleiman. Boston: MFA Publications, pp. 256–58. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, Thomas. 1889. The Law of France Relating to Industrial Property, Parents, Trade Marks, Merchandise Marks, Trade Names, Models, Patterns, Designs, Wrappers, Prospectuses, Exhibition Rewards and Medals, Unpatented Industrial Secrets, & Colonial, Algerian and Tunisian Regulations. London: Sweet and Maxwell Limited. [Google Scholar]

- BOPI. 1909. Marques De Fabrique Et De Commerce: Deposées Conformément a La Loi Du 23 Juin 1857: Kub. Paris: Bulletin Officiel de la Propriété Industrielle et Commerciale, pp. 908–9. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, William Henry. 1898. A Treatise on the Law of Trade-Marks and Analogous Subjects, 2nd ed. Boston: Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Chessel, Marie-Emmanuelle. 1998. La publicité: Naissance d’une profession, 1900–1940. Paris: CNRS. [Google Scholar]

- Coddington, Charles E. 1878. A Digest of the Law of Trademarks: As Presented in the Reported Adjudications of the Courts of the United States, Great Britain, Ireland, Canada, and France, from the Earliest Period to the Present Time. New York: Ward & Peloubet. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins, Judith. 1989. Documentary Chronology. In Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism. Edited by William Rubin. New York: Museum of Modern Art, pp. 335–452. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Neil. 2000. Cubism. London: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

- Elcott, Noam M. 2024. The Manufacturer’s Signature: Trademarks and Other Signs of Authenticity on Manet’s Bar at the Folies-Bergère. Grey Room 94: 114–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, Michael C. 1995. Making Modernism: Picasso and the Creation of the Market for Twentieth-Century Art. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Gleizes, Albert, and Jean Metzinger. 1912. Du “Cubisme”. Paris: Eugène Figuière Éditeurs. [Google Scholar]

- Hémard, Joseph. 1912a. Études De Vacances. La Vie Parisienne 50: 498. [Google Scholar]

- Hémard, Joseph. 1912b. Peinture Cubiste. Le Rire 19. [Google Scholar]

- Iskin, Ruth E. 2014. The Poster: Art, Advertising, Design, and Collecting, 1860s–1900s. Hanover: Dartmouth College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, Michel. 1893. Droit Industriel: Brevets D’invention, Marques de Fabrique, Modèles et Dessins, Nom Commercial, Concurrence Déloyale. Paris: Baudry. [Google Scholar]

- Pivot, Monique. 2002. Maggi et la Magie du Bouillon Kub. Paris: Éditions Hoëbeke. [Google Scholar]

- Pouillet, Eugène. 1892. Traité des Marques de Fabrique et de la Concurrence Déloyale en Tous Genres, 3rd ed. Paris: Marchal et Billard. [Google Scholar]

- Pouillet, Eugène, André Taillefer, and Charles Claro. 1912. Traité des Marques de Fabrique et de la Concurrence Deloyale en Tous Genres, 6th ed. Paris: Marchal et Billard. [Google Scholar]

- Pouillet, Eugène, André Taillefer, and Claro Claro. 1911. Traité Theorique et Pratique des Dessins et Modeles, 5th ed. Paris: Marchal et Godde. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinow, Rebecca A. 2014. Jouer: The Games Cubists Play. In Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection. Edited by Emily Braun and Rebecca A. Rabinow. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 170–79. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, John. 1996. A Life of Picasso: Volume II. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, Daniel. 1985. Jean Metziner: At the Center of Cubism. In Jean Metzinger in Retrospect. Edited by Joann Moser. Iowa City: University of Iowa Museum of Art, pp. 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, Colin, and Robert Slutzky. 1963. Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal. Perspecta 8: 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, Nancy. 2003. Couture Culture. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vauxcelles, Louis. 1909. Le Salon des Indépendants. Gil Blas, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Vauxcelles, Louis. 1912. Au Selon des Indépendants. Gil Blas, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Jeffrey. 1994. The Popular Culture of Modern Art. New Haven: Yale University. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elcott, N.M. Kubism™: Picasso, Trademarks and Bouillon Cube. Arts 2024, 13, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13010030

Elcott NM. Kubism™: Picasso, Trademarks and Bouillon Cube. Arts. 2024; 13(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleElcott, Noam M. 2024. "Kubism™: Picasso, Trademarks and Bouillon Cube" Arts 13, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13010030

APA StyleElcott, N. M. (2024). Kubism™: Picasso, Trademarks and Bouillon Cube. Arts, 13(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13010030