Queer Nightlife and Contemporary Art Networks: A Study of Artists at the Bar

Abstract

:“Look at the history of queer performance. Much of it was not considered art for a really long time, in part because it emerged in community spaces and gay bars. Spaces that were, we might say, breaking-off spaces rather than bridging spaces. You can’t understand its qualities without understanding the communities from which it emerges.”

1. Introduction: Queer Nightlife as Incubator

2. Why Queer Nightlife?

3. Escandalos Angeles (2018)

4. Nostra Fiesta (2019)

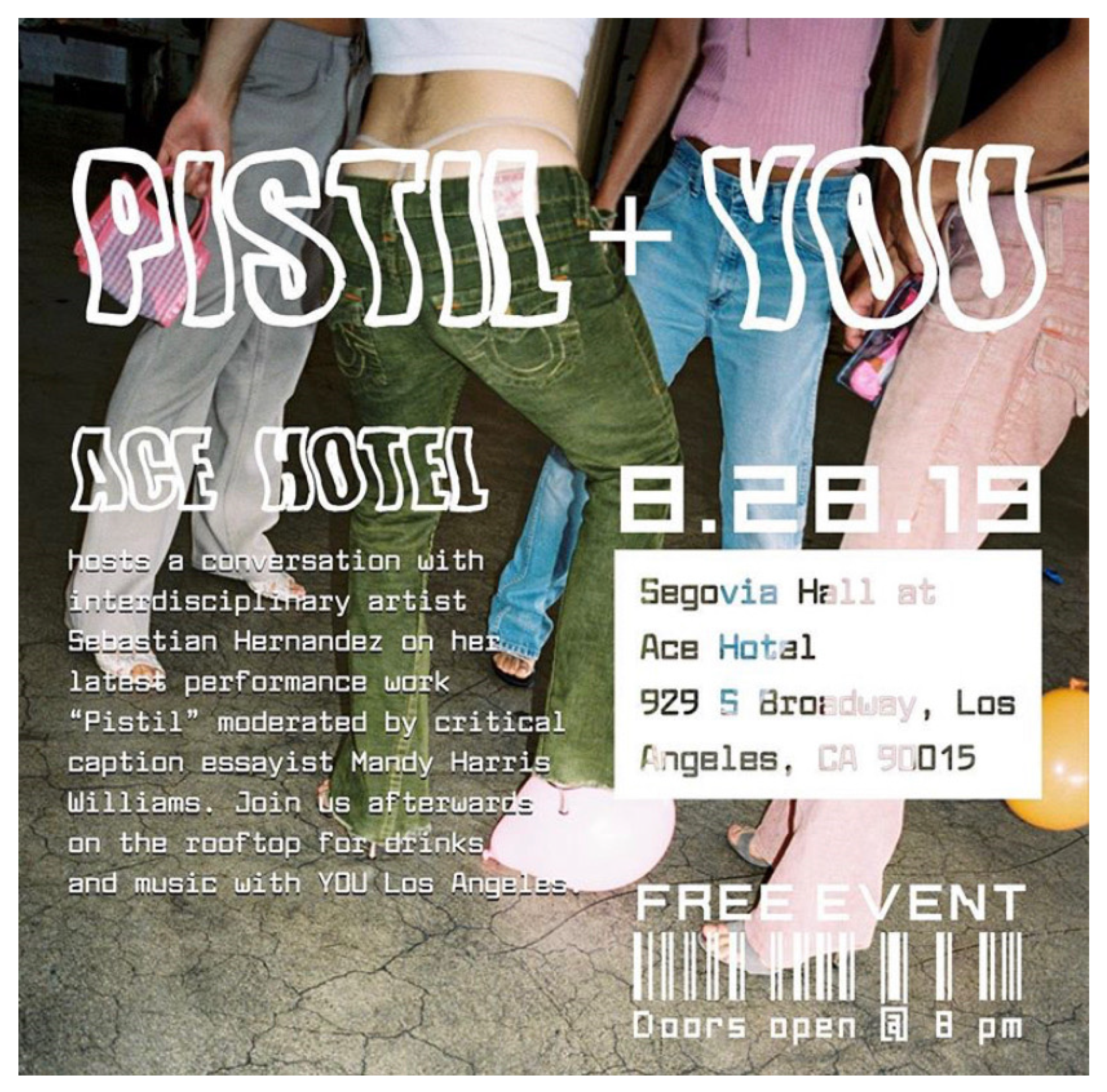

5. YOU (2019-Ongoing)

6. Conclusions

“The performance work I do was really born out of responding to being shunned or excluded from a community. And so, creating these spaces where we could view something and experience something together has been the vehicle that inspires me to want to continue to make work outside of museums”.(esparza in Christovale and Ellegood 2018, p. 104)

“[At Mustache], you [would] pay your ten or fifteen-dollar ticket to go hear music and dance all night. But then in the middle of it you have a great fucking performance artist who will just perform in the middle of the night. You don’t have to go to a museum to experience this”.

“Queer club culture and nightlife has been a formative part of my art-making for over a decade and has impacted what it looks like today … I am interested in seeing how my party will impact the next generation of art-making in Los Angeles”.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For more about esparza’s reframing of art and exhibition opportunities for other artists, collaborators, or friends, and the politics of this artistic strategy, see (Grossman 2017). |

| 2 | de la Calle culminated with a guerrilla parade-like procession through Los Callejones/Santee Alley in downtown Los Angeles that was promoted only via word of mouth. If we consider it outside its art institution origination, the performance could have easily been its own case study in this article: one that emphasizes the network’s connection to this historic shopping site for the purchase of various elements of their nightlife looks; the important ways in which esparza and other members of this network created the performance for themselves and specific members of their queer and/or cultural communities, in this case the workers and shoppers of this working-class, predominantly Latinx, stronghold in the city; and the immense interest in the performance by the art world and people on social media, where those not involved wondered how and/or why they were not included. See also (Miranda 2018). |

| 3 | But as the editors of Queer Nightlife (2021) poignantly express, “queer nightlife does not need the perceived legitimacy of scholarship to be legible or to thrive”. See (Adeyemi et al. 2021, p. 10). |

| 4 | These include (Ghaziani 2024; Hilderbrand 2023; García-Mispireta 2023; Mattson 2023; Adeyemi 2022; Allen 2022; Adeyemi et al. 2021; Lin 2021; Khubchandani 2020; Chambers-Letson 2018); and (Moore 2018). This increase in scholarship notably coincides with the 50th anniversary of Stonewall in 2019, commonly recognized as the birth of the U.S. gay liberation movement. It’s safe to say queer nightlife studies is here to stay. |

| 5 | The arts, broadly defined, have not always been at the forefront of queer nightlife analyses, with some exceptions. madison moore has notably written about the experience of queer nightlife through aesthetic terms (Moore 2016, pp. 50–51), and has referenced art or artists in related books and articles (Moore 2016, 2018). Additional scholars who come to mind include (J.M. Rodríguez 2021) who detailed performance artist Xandra Ibarra’s bar hopping tour; and (Hilderbrand 2023) who wrote about the New Jalisco Bar mural also featured in this article. |

| 6 | My curatorial practice and scholarship often aims to consider alternative ways to study art and visual culture. As I was building my expertise in live art and performance studies, the work of scholars Amelia Jones and Adrian Heathfield helped to shape my understanding and embrace of engaging with fields outside of art history to provide “new models for thinking about how visual and embodied cultural expressions come to mean”. See (Jones and Heathfield 2012, p. 12). |

| 7 | In many regards, this practice has been modeled after Italian painter and architect Giorgio Vasari, who relied heavily on individual authorship and biography to tell the story of Renaissance art in The Lives of the Artists. This now-classic text set the ideological and structural foundation for art historical scholarship that has continued today. See (Vasari [1550] 1991). |

| 8 | This is true for esparza’s exhibitions at the Vincent Price Art Museum, Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (ICA LA), and the Hammer and Whitney biennials, among others. For the biennials, esparza’s collaborations are especially significant given the large-scale format. See Martha Rosler’s contributions to (Griffin 2003). |

| 9 | In addition to Liberate the Bar! (2019) at ONE Archives, there have been several exhibitions by alternative art spaces, galleries, and museums in my recent memory that have referenced both queer nightlife and contemporary art, including Estilazo (2022) at The Latinx Project, New York University; It’s Much Louder Than Before (2021) at Anat Ebgi; Sadie Barnette: The New Eagle Creek Saloon (2019-Ongoing) at several organizations; and Party Out of Bounds: Nightlife As Activism Since 1980 (2015) at Visual AIDS and La MaMa Galleria. |

| 10 | This approach exercises a node of performativity in interpretation, as described by scholars and theorists Amelia Jones and Andrew Stephenson, where an element of performance is embedded in the act of ascribing meaning and value for art and performance, ultimately contributing to a more dynamic and contingent interpretation. See (Jones and Stephenson 1999) and (Jones 2012). |

| 11 | This has certainly been my experience as someone raised in a Mexican and Chicano enclave in Orange County, CA, but who works, socializes, and builds community within Los Angeles’s eastside and downtown areas. To learn more about queer sociality and the urban/suburban binary for queers of color in Southern California, see (Tongson 2011). For a transnational account, with chapters on California, see (Ingram et al. 1997). |

| 12 | While many public places have served as sites for sociality and leisure, including restaurants, cafes, parks, public events, and the streets themselves, this article hones in on queer nightlife as the site where sociality and leisure meet activism, community-building, and art-making to carve new space in the city. For a fantastic placemaking account of a single restaurant (which later became a nightclub due to gentrification and change of ownership), see (Molina 2015). On the boulevard, see (Fragoza 2017). |

| 13 | I am using “Chicano” in this context to point to a generation of young people in the 1960s and 1970s who self-identified with the term and built a collective civil rights and arts movement based on the identification. To learn more about this approach and its parameters, see (García 2015). |

| 14 | This quest for social and sexual freedom highlights the ways young queers of color since the 1960s, including Latinx folks, have challenged demarcated urban space. For more on this process, see (R.T. Rodríguez 2015). For Chicano space making in LA, see (Macias 2008). For a personal account from a Chicano perspective, see (Rojas 2016). |

| 15 | Queer communities that performance artist Ron Athey circulated in the 1980s and 1990s, for example, which included friends such as Vaginal Davis and Jennifer Doyle (whose remarks opens this article), were mostly linked to punk movements in Silver Lake/Echo Park and on the edges of downtown. (Jones 2020, pers. comm.). |

| 16 | I am indebted to Paulina Lara who, through her own life and through the course of conducting research for our exhibition Liberate the Bar! Queer Nightlife, Activism, and Spacemaking, shared with me so many different nightlife stories about Nava, and introduced me to their friends, collaborators, and the late-night places where they partied. |

| 17 | In a retrospective article for Red Bull Music Academy, Marke B. writes: “Mustache launched during a moment of creative ferment in American queer nightlife when a growing population of clubgoers was reacting against the homogenized pop-house sounds and cookie-cutter corporate feel of the clubs and culture at large… [Mustache had a] mission to diversify gay nightlife”. See (Bieschke 2017). |

| 18 | This is the core argument of my unpublished master’s thesis, which serves as the basis of this article. See (Valencia 2020). It was later explored through a KCET Artbound documentary and accompanying article. See (KCET Artbound 2021) and (Hidalgo 2021). |

| 19 | My intention here is to acknowledge Nava and Mustache as critical influences in this study of this queer nightlife network, its relationships, and creative outputs, but I write with sensitivity and care, and also love, especially for Paulina Lara, my friend who I have known for many years and whose side I have been by as she has experienced and processed Nava’s loss. |

| 20 | The event title, Escandalos Angeles, is a portmanteau of the Spanish words Escandalosa (scandalous) and Los Ángeles (LA) and also references a direct connection to Legorreta who used that term to describe himself and his work. See footnote annotations #34 and #52 in (R. Hernandez 2019a, pp. 271–72). |

| 21 | My use of Chicano here specifically evokes gender and same-sex exclusion and discrimination present within East Los Angeles during this time. On this point see (Flores Sternad 2006, p. 477). For a deeper historical account Robert “Cyclona” Legorreta’s life, activism, artistic practice, and archives, see (R. Hernandez 2009). |

| 22 | San Cha is also a friend and collaborator within this network, notably beginning her career in queer nightlife drag and performance scenes in Los Angeles and the Bay Area, before settling in Los Angeles to work exclusively as a singer-songwriter and performer. See (Mendez 2018). |

| 23 | It must also be stated that although Legorreta is still very much alive, he was not sought out or invited to participate in this performance program, and in some respects, the event gave the impression that he was actually deceased. Nao Bustamante, who had attended the event, had questioned, in a hysteric frenzy with fellow performance artist Marcus Kuiland-Nazario a few days prior to the event, “What if Cyclona just shows up and performs and ruins the party!? That would be so amazing!” To Bustamante’s disappointment, Legorreta did not intervene, nor did he show up at all. (Bustamante 2020, pers. comm.) I hope to pursue a future investigation of what this performance means in the absence of Legorreta. |

| 24 | esparza also develops work with this strategy in mind. “I’m always thinking about history”, esparza once stated. “As I walk through the city, I’m always imagining the many changes the landscape has undergone and attempting to imagine what the landscape looked like before all of these different migrations happened”. See Esparza’s comments in (Christovale and Ellegood 2018, p. 96). |

| 25 | Legorreta moved through different scenes with the help of sophisticated modes of self-fashioning. At times he was enmeshed in proto-punk and glitter queer scenes, and other times he infiltrated various gay and straight bars to seduce and tease cholos. This thread of seduction also links Hernandez and Ruiz’s performance with Legorreta. On Legorreta and “proto-punk” see (Flores Sternad and Lacy 2012, p. 96); On Legorreta and “glitter queer” see (Flores Sternad 2006, p. 485); On “teasing cholos” see (Flores Sternad 2006, p. 481). |

| 26 | Coincidently, Legorreta employed this very performance strategy, only in his case it was decades prior and for a dear friend: Edmundo “Mundo” Meza at the first-anniversary celebration of VIVA! Lesbian and Gay Latino Artists of Los Angeles, an artist coalition and nonprofit committed to increasing queer Latinx representation in art, performance, and activist circuits in Los Angeles. While there are differences between these artists and their evocations—Meza’s life and artistic contribution at the time risked near erasure from the historical record, compared to Legorreta, whose archives are preserved by and available for viewing at the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center and ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at USC Libraries—the performance of remembrance enacted by Legorreta, Hernandez, and Ruiz across time and space further elucidates how knowledge sharing and the honoring of artistic and ancestral lineages is a key strategy for queer of color culture and creative expression. On Legorreta’s performance, see (R. Hernandez 2019b). |

| 27 | On queering “straight” time, see (Muñoz 2007, pp. 457–58). |

| 28 | Jalisco’s clientele is notably different from those who have historically frequented Club Chico (the bar mentioned in the first case study of this article). In my experience, first-generation Latinx frequenters, many Spanish-speaking, form the core of Jalisco’s base, while Latinx Angelenos who are more assimilated, including previous cholo clients of the 2000s, have found their home at Chico. In recent years, Chico has broadened its appeal to a more general Latinx audience, and this has only extended since hosting Club sCUM on the last Friday of each month. It is also notable that esparza, Hernandez, and Ruiz, and members of their queer nightlife network, frequent both Jalisco and Chico, a detail that I attribute to their heterogeneous cultural identifications and investments in their city’s queer nightlife landscape. On these particular Latinx venues and their varied functions and clientele, see also (Hilderbrand 2023). |

| 29 | Gonzalez is a Los Angeles contemporary artist and muralist whose father is a commercial sign painter. Here, esparza, Ruiz, and Lara pulled from their networks to locate the resources they needed to complete their project. On Gonzalez’s practice, see (Khatchadouria 2019). |

| 30 | Chicana feminist Cherie Moraga writes about this homophobia and cultural resistance, asserting that true liberation in El Movimiento is one that includes the embrace of all its people, including its jotería (queers). See (Moraga 2004, p. 225). |

| 31 | Interestingly enough, Netflix’s recent comedy-drama series Gentefied (2020), created by Marvin Lemus and Linda Yvette Chávez, also details a fictional Boyle Heights mural that is protested against for its queer iconography. Learn more in (Cuby 2020). |

| 32 | In a future text, I am interested in writing about the visuality of YOU vis-à-vis the digital flyers from each iteration of the party. These are designed by Hernandez and incorporate a range of cultural, vernacular, and art historical references, further emphasizing links among nightlife, visual arts, performance, and other modes of cultural production. |

| 33 | In a video feature, Hernandez says: “I live in an oppressive society in which I have had to fight for my existence. I know that if I am dancing, I am alive, and for me movement is happiness”. See (S. Hernandez 2018). |

| 34 | Since 2016, Hernandez has exhibited their work and performed at venues across Los Angeles, including Angels Gate Cultural Center; Club sCUM; Commonwealth and Council; Human Resources Los Angeles; Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Mustache Mondays; NAVEL; ONE Gallery, West Hollywood; and downtown’s Roy and Edna Disney Cal Arts Theatre (REDCAT), among many others. |

| 35 | This is one of the central points in (Chambers-Letson 2018). See also (Muñoz 2007, p. 454). |

References

- Adeyemi, Kemi. 2022. Feels Right: Black Queer Women and the Politics of Partying in Chicago. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemi, Kemi, Kareem Khubchandani, and Ramón H. Rivera-Servera. 2021. Queer Nightlife. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Jafari S. 2022. There’s a Disco Ball between Us: A Theory of Black Gay Life. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aponte-Parés, Luis. 2001. Outside/In: Crossing Queer and Latino Boundaries. In Mambo Montage: The Latinization of New York. Edited by Agustín Laó-Montes and Arlene Dávila. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 363–85. [Google Scholar]

- B., Marke. 2017. Celebrating Ten Years of Mustache Mondays, LA’s Iconoclastic Party. Redbull Music Academy Daily. October 20. Available online: https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2017/10/mustache-mondays (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Barrón Gavito, Miguel Ángel. 2010. El baile de los 41: La representación de lo afeminado en la prensa porfiriana. Historia Y Grafía 34: 47–73. [Google Scholar]

- Buckland, Fiona. 2002. Impossible Dance: Club Culture and Queer World-Making. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, Nao. 2020. University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Personal communication.

- Chambers-Letson, Joshua. 2018. After the Party: A Manifesto for Queer of Color Life. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Meiling. 2002. In Other Los Angeleses: Multicentric Performance Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christovale, Erin, and Anne Ellegood. 2018. Bridging and Breaking: Roundtable with Erin Christovale. Jennifer Doyle, Anne Ellegood, rafa esparza, Naima J. Keith, and Lauren Mackler. In Made in L.A. 2018. Edited by Erin Christovale and Anne Ellegood. Los Angeles: Hammer Museum, pp. 92–113. [Google Scholar]

- Cuby, Michael. 2020. Seen: Gentefied Tackles Gentrification with Humor and Authenticity. Them. February 21. Available online: https://www.them.us/story/gentefied-gentrification-netflix (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Dinco, Dino. 2017. Loving and Partying at Chico: ‘The Best Latino Gay Bar’ in Montebello. KCET Artbound. February 15. Available online: https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/history-behind-chico-latino-gay-bar-montebello-los-angeles (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- Donohue, Caitlin. 2019. Remembering Nacho Nava, a Force in Los Angeles’ Queer Nightlife Community. Remezcla. January 24. Available online: https://remezcla.com/music/nacho-nava-memorial-fund-scholarship (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- Flores Sternad, Jennifer. 2006. Cyclona and Early Chicano Performance Art: An Interview with Robert Legorreta. GLQ 12: 475–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores Sternad, Jennifer, and Suzanne Lacy. 2012. Voices, Variations, and Deviations: From the LACE Archive of Southern California Performance Art. In Live Art in LA: Performances in Southern California, 1970–1983. Edited by Peggy Phelan. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fragoza, Carribean. 2017. Cruising Down SoCal’s Boulevards: Streets as Spaces for Celebration and Cultural Resistance. KCET Artbound. February 24. Available online: https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/cruising-on-socals-boulevards-the-streets-as-spaces-for-celebration-and-cultural (accessed on 9 December 2019).

- García, Mario T. 2015. The Chicano Generation: Testimonios of the Movement. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- García-Mispireta, Luis Manuel. 2023. Together Somehow: Music Affect and Intimacy on the Dancefloor. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaziani, Amin. 2024. Long Live Queer Nightlife: How the Closing of Gay Bars Sparked a Revolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, Tim. 2003. Global Tendencies: Globalism and the Large-Scale Exhibition. Roundtable Discussion with James Meyer, Francesco Bonami, Catherine David, Okwui Enwezor, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Martha Rosler, and Yinka Shonibare. ARTFORUM 42: 152–63. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, Hannah E. 2017. Performative Futurity: Transmuting the Canon through the Work of Rafa Esparza. Master’s thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Helou Hernandez, Samanta. 2019. Gabriela Ruiz Is Young, Subversive and Forging Her Own Way in the Art World. KCET Artbound. January 29. Available online: https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/gabriela-ruiz-is-young-subversive-and-forging-her-own-way-in-the-art-world (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- Hernandez, Robb. 2009. The Fire of Life: The Robert Legorreta-Cyclona Collection. Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Robb. 2019a. Archiving an Epidemic: Art, AIDS, and the Queer Chicanx Avant-Garde. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Robb. 2019b. Mundos Alternos—Alien Skins. YouTube. May 9. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?t=7s&v=qbG7v75RZJM (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Hernandez, Sebastian. 2018. Be You: Finding Liberation in Art with Sebastian Hernandez. BESE. December 7. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYYFkZsrxXo (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Hernandez, Sebastian. 2019. Independent Artist. Personal communication.

- Hidalgo, Melissa. 2021. How Mustache Mondays Built an Inclusive Queer Nightlife Scene and Influenced the Arts in L.A. KCET Artbound. November 17. Available online: https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/mustache-mondays-inclusive-nightlife-and-contemporary-art (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Hilderbrand, Lucas. 2023. The Bars Are Ours: Histories and Cultures of Gay Bars in America 1960 and After. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, Gordon Brent, Anne Marie Bouthillette, and Yolanda Retter. 1997. Queers in Space: Communities, Public Places, Sites of Resistance. Seattle: Bay Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Amelia. 2012. Seeing Differently: A History and Theory of Identity and the Visual Arts. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Amelia. 2020. University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Personal communication.

- Jones, Amelia, and Adrian Heathfield. 2012. Perform, Repeat, Record: Live Art in History. Bristol: Intellect. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Amelia, and Andrew Stephenson. 1999. Performing the Body/Performing the Text. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- KCET Artbound. 2021. Mustache Mondays. November 17. Available online: https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/episodes/mustache-mondays (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Khatchadouria, Alex. 2019. Finding Art in the Everyday: Alfonso Gonzalez Jr.’s Paintings Depict a Localized Perception of His Surroundings. Amadeus. July 30. Available online: http://amadeusmag.com/blog/finding-art-everyday-alfonso-gonzalez-jr (accessed on 29 March 2020).

- Khubchandani, Kareem. 2020. Ishtyle: Accenting Gay Indian Nightlife. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Korte, Gregory, and Alan Gomez. 2018. Trump Ramps up Rhetoric on Undocumented Immigrants: ‘These Aren’t People. These Are Animals.’ . USA Today. May 16. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2018/05/16/trump-immigrants-animals-mexico-democrats-sanctuary-cities/617252002 (accessed on 1 December 2018).

- Lara, Paulina. 2019. Independent Curator. Personal communication.

- Lara, Paulina. 2020. Independent Curator. Personal communication.

- Lin, Jeremy Atherton. 2021. Gay Bar: Why We Went Out. New York: Back Bay Books. [Google Scholar]

- Macias, Anthony F. 2008. Mexican American Mojo: Popular Music, Dance, and Urban Culture in Los Angeles, 1935–1968. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mattson, Greggor. 2023. Who Needs Gay Bars? Bar-Hopping through America’s Endangered LGBTQ Places. Stanford: Redwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez, Stephanie. 2018. San Cha, The Fierce Latinx Musician Anchoring Herself in Rancheras and Identity. She Shred Media. November 7. Available online: https://sheshreds.com/san-cha (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Miranda, Carolina. 2018. Why Artist Rafa Esparza Led a Surreal Art Parade through the Heart of L.A.’s Fashion District. Los Angeles Times. June 25. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/miranda/la-et-cam-rafa-esparza-ica-la-20180625-story.html (accessed on 16 December 2019).

- Molina, Natalia. 2015. The Importance of Place and Place-Makers in the Life of a Los Angeles Community: What Gentrification Erases from Echo Park. Southern California Quarterly 97: 69–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Madison. 2016. Nightlife as Form. Theater 46: 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Madison. 2018. Fabulous: The Rise of the Beautiful Eccentric. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moraga, Cherie. 2004. Queer Aztlán: The Re-formation of Chicano Tribe. In Queer Cultures. Edited by Deborah Carlin and Jennifer DiGrazia. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall, pp. 224–38. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 1999. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 2007. Queerness as Horizon: Utopian Hermeneutics in the Face of Gay Pragmatism. In A Companion to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Studies. Edited by George E. Haggerty and Molly McGarry. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 452–63. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 2009. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Najar, Alberto. 2017. ¿Por qué en México el número 41 se asocia con la homosexualidad y sólo ahora se conocen detalles secretos de su origen? BBC Mundo. January 11. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-38563731 (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- Nordeen, Bradford. 2018. Dirty Looks: On Location (Event Series Booklet). Los Angeles: Dirty Looks Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, Maura. 2017. What Is Curatorial Activism? ARTnews. November 7. Available online: https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/what-is-curatorial-activism-9271/ (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Rodríguez, Juana María. 2021. Public Notice from the Fucked Peepo: Xandra Ibarra’s ‘The Hookup/Displacement/Barhopping Drama Tour.’. In Queer Nightlife. Edited by Kemi Adeyemi, Kareem Khubchandani and Ramón Rivera-Servera. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 211–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Richard T. 2006. Queering the Homeboy Aesthetic. Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies 31: 127–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Richard T. 2015. The Architectures of Latino Sexuality. Social Text 33: 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, James. 2016. From the Eastside to Hollywood: Chicano Queer Trailblazers in 1970s L.A. KCET LOST LA. September 2. Available online: https://www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/from-the-eastside-to-hollywood-chicano-queer-trailblazers-in-1970s-la (accessed on 9 December 2019).

- Román, David. 2011. Dance Liberation. In Gay Latino Studies: A Critical Reader. Edited by Michael Hames-Garcia and Ernesto Javier Martínez. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 286–310. [Google Scholar]

- Roque Ramírez, Horacio N. 2003. “That’s My Place!”: Negotiating Racial, Sexual, and Gender Politics in San Francisco’s Gay Latino Alliance, 1975–1983. Journal of the History of Sexuality 12: 224–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque Ramírez, Horacio N. 2007. “Mira, yo soy boricua y estoy aquí”: Rafa Negrón’s Pan Dulce and the queer sonic latinaje of San Francisco. Centro Journal XIX: 274–313. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, Gabriela. 2018. Independent Artist. Personal communication.

- The New Jalisco Bar. 2018. Travel Gay. October 19. Available online: https://www.travelgay.com/venue/the-new-jalisco-bar (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- Tongson, Karen. 2011. Relocations: Queer Suburban Imaginaries. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, Joseph Daniel. 2020. Queer Nightlife Networks and the Art of Rafa Esparza, Sebastian Hernandez, and Gabriela Ruiz. Master’s thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, Joseph Daniel. 2023. “Striving Toward Multiple Ideas of Community”: Chicanx Art, Artists, and Affectivity in Los Angeles. In Xican-a.o.x. Body. Edited by Cecilia Fajardo-Hill, Marissa Del Toro and Gilbert Vicario. Munich: Hirmer Publishers, pp. 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Vasari, Giorgio. 1991. Preface to Part Three. In The Lives of the Artists. Translated by Julia Conaway Bondanella, and Peter Bondanella. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published in 1550. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valencia, J.D. Queer Nightlife and Contemporary Art Networks: A Study of Artists at the Bar. Arts 2024, 13, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020072

Valencia JD. Queer Nightlife and Contemporary Art Networks: A Study of Artists at the Bar. Arts. 2024; 13(2):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020072

Chicago/Turabian StyleValencia, Joseph Daniel. 2024. "Queer Nightlife and Contemporary Art Networks: A Study of Artists at the Bar" Arts 13, no. 2: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020072

APA StyleValencia, J. D. (2024). Queer Nightlife and Contemporary Art Networks: A Study of Artists at the Bar. Arts, 13(2), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020072