Affect and Ethics in Mike Malloy’s Insure the Life of an Ant

Abstract

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Gregory Battcock, whose writing about Insure the Life of an Ant I address later in the essay, called O.K. Harris “one of the most prestigious and trend-setting galleries in New York”. See (Battcock 1972a, p. 45). |

| 2 | The dearth of literature on this piece is mildly surprising, especially its lack of mention in the major studies on animals in art. After a flurry of coverage at the time of its exhibition, which I address later, it essentially dropped out of critical and scholarly sight. I have discussed this piece at three conferences: as chair of a session, “Beyond Censorship: Art and Ethics”, at the College Art Association annual conference in Los Angeles in 2012; in a paper “‘What would you do?’: Mike Malloy’s Insure the Life of an Ant”, for the Visual Culture session at the Popular/American Culture Association, in Washington, DC in 2013; and in a paper “Art, Ethics, Censorship, and Animal Rights: The Role of Social Media”, for the “Networked Art Session”, part of a themed conference—“The Work of Art in the Age of Networked Society”—at the International Conference on the Arts in Society, in London, United Kingdom, in 2015. At the College Art session, art historian Jonathan Wallis mentions Insure the Life of an Ant in his paper entitled, “Blending Art and Ethics: Marco Evaristti’s Helena and the Killing Aesthetic”. I alerted Dr. Wallis to the Malloy piece in my invitation to him to present. His paper developed into an excellent published essay: See (Wallis 2012). In addition, the websites “98 Bowery: 1969–1989” and “Gallery 98”, curated by Marc Miller, who knew Malloy at the time, are good resources for information and documentation about the piece. See: (Miller 2015) and (Miller n.d.). |

| 3 | There is a fair amount of literature on animals and art, and my intention is not an in-depth examination of it here. Leading scholars include Giovanni Aloi and Steve Baker, and their writings are very much worth consulting. See, for example (Aloi 2012, 2018; Baker 2013). Other useful sources are: (Eisenman 2013; Zammit-Lucia 2014). Zammit-Lucia also participated in my 2012 CAA session (see note 2). In 2023, this journal, Arts, published a themed issue “Art and Animals and the Ethical Position”: see (Bartram 2023). There are, of course, many organizations working to protect animals, and some make mention of maltreatment in art. Also see note 6. |

| 4 | Malloy’s piece may intersect with the concept of “relational aesthetics”, a term coined well after this work was made. See (Bourriaud 1998). There have been subsequent and updated versions, including translations into English, the latest in 2023. Bourriaud defined relational aesthetics as: “A set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space”. While Insure the Life of an Ant might not fit this definition precisely, it is somewhat in the spirit of what Kyle Chayka considers as relational aesthetics: “The posing of an artist-constructed social experiences (sic) as art making”. He goes on: “relational aesthetics projects tend to break with the traditional physical and social space of the art gallery and the sequestered artist studio or atelier”. See (Chayka 2011). Claire Bishop, whose scholarship addresses this term, clarifies that not all interactive art is classifiable as relational aesthetics, and Insure the Life of an Ant might be considered too prescriptive and not open-ended enough, though, as we shall see, the piece engendered some unexpected responses. Yet Bishop is particularly interested in art situations that antagonize, analyzing the work of several artists, including Santiago Sierra. Sierra’s troubling exploitation and abuse of human subjects as art in an art setting bear some relation to Malloy’s set-up of potential harm to non-human animals. In the Malloy work, however, the viewer has more clear-cut power to spare and possibly even aid the potential non-consenting victims. Sierra’s subjects are humans who give consent, but because of their social and economic status, their ability to consent has been compromised. His works also interrogate the issue of what is the responsibility of ethical viewers to intervene in what could be defined as cruel art practice. For more on problematically provocative relational art, see (Bishop 2004, 2023). Eunsong Kim, in a powerful essay, mercilessly excoriates Bishop and other scholars who support the value of Sierra’s controversial work. See (Kim 2015). |

| 5 | I do not intend to wade into the substantial literature on neuroscience, affect, and emotions, as it applies to human and non-human animals. An important and pioneering scholar on animal emotion was Estonian-American psychobiologist, Jaak Panksepp, who coined the term “affective neuroscience”. See, for example, (Panksepp 2011); also, (Panksepp 1998). Also see note 27. |

| 6 | (Bentham 1789, ch. 17, n. 222). As to the broader issue of animal rights, much has been written, especially from legal and philosophical perspectives. My essay makes no claim to a comprehensive review of this literature. In addition to Bentham and contemporary philosopher, Peter Singer, whom I mention later (see note 50), a recent book that has received attention is: (Nussbaum 2022). Also see: (Wacks 2024). Useful anthologies include: (Sunstein and Nussbaum 2004; Linze and Clarke 2005). Also see note 3. |

| 7 | (Hall 2024). |

| 8 | The literature across disciplines is substantial. As for the visual arts, Jill Bennett has considered the subject in two books: (Bennett 2005, 2012). Two books by James Elkins are also useful: (Elkins 1998, 2001). A pioneering study in this area remains: (Freedberg 1989). |

| 9 | Telephone interview with the artist Michael Malloy by the author, Fall, 2011. |

| 10 | The bibliography on new and different ways of thinking about aesthetics is substantial. A few key works include (Bennett 2012; Elkins 2005; Rancière 2004). |

| 11 | Jonathan Wallis’ essay (see note 2) contains a first-rate discussion of the concept of the potential amorality of the art space. |

| 12 | Letter from Mike Malloy to Marc Miller and Carla [Dee Ellis], 20 January 1972. (Gallery 98 Archives). See (Miller 2015). Marc Miller, artist, art historian, museum curator, and owner of the websites “Gallery 98”, and “98 Bowery”, named after the address of the loft he then lived in, was friends with Malloy at the time. Miller provided Malloy with living space when Malloy first arrived in New York City (see note 2). |

| 13 | I am reminded of the remarks by the brilliant black comedian Dick Gregory about capital punishment in the United States. To have it affect the average citizen more viscerally, he “jokingly” suggested the following: run a wire from a prison electric chair to a random home so that an execution occurs when you turn something on in your house; you find out that you did the grisly deed when you later receive a check from the government for your service. Or save up all the executions for a given year until Christmas season (Christmas Eve preferably) and hook up all the electric chairs to the same switch that the president uses to light the national Christmas tree, bringing “joy to the world” and killing death row inmates at the same time. See (University of Chicago 1965). |

| 14 | (Miller n.d.). |

| 15 | E-mail correspondence between Michael Malloy and the author, March, 2024. In recent correspondence, Miller wondered if he might have overstated the drama surrounding the show. E-mail correspondence with Marc Miller, March, 2024. |

| 16 | E-mail correspondence between Alan Moore and the author, 2012. Alan Moore is an artist, art historian, curator, and art writer. |

| 17 | See (Miller n.d.); also, (Heinemann 1975). |

| 18 | (B.S. 1972, p. 54). |

| 19 | (Lubell 1972., p. 61). |

| 20 | (Battcock 1972a, 1972b). |

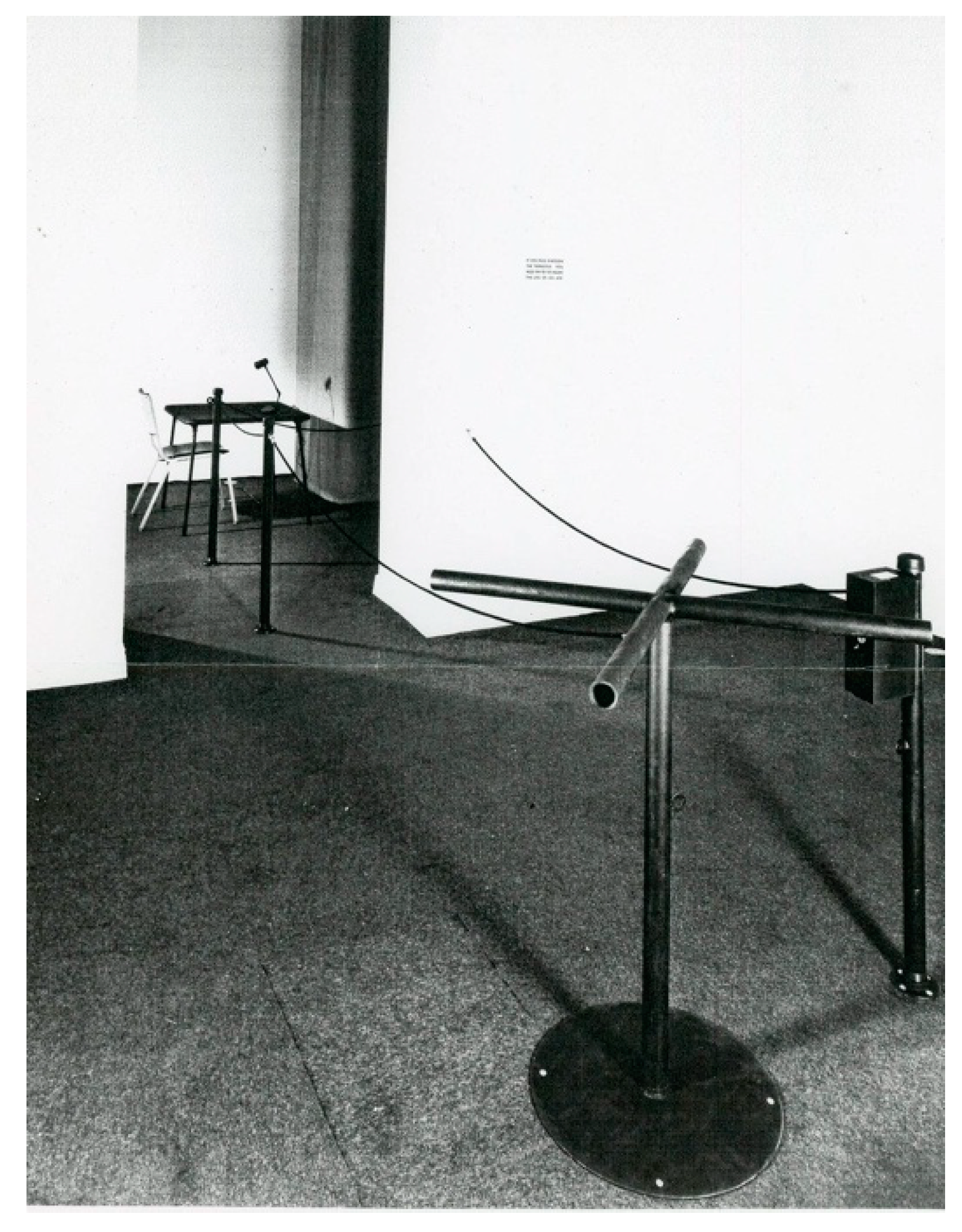

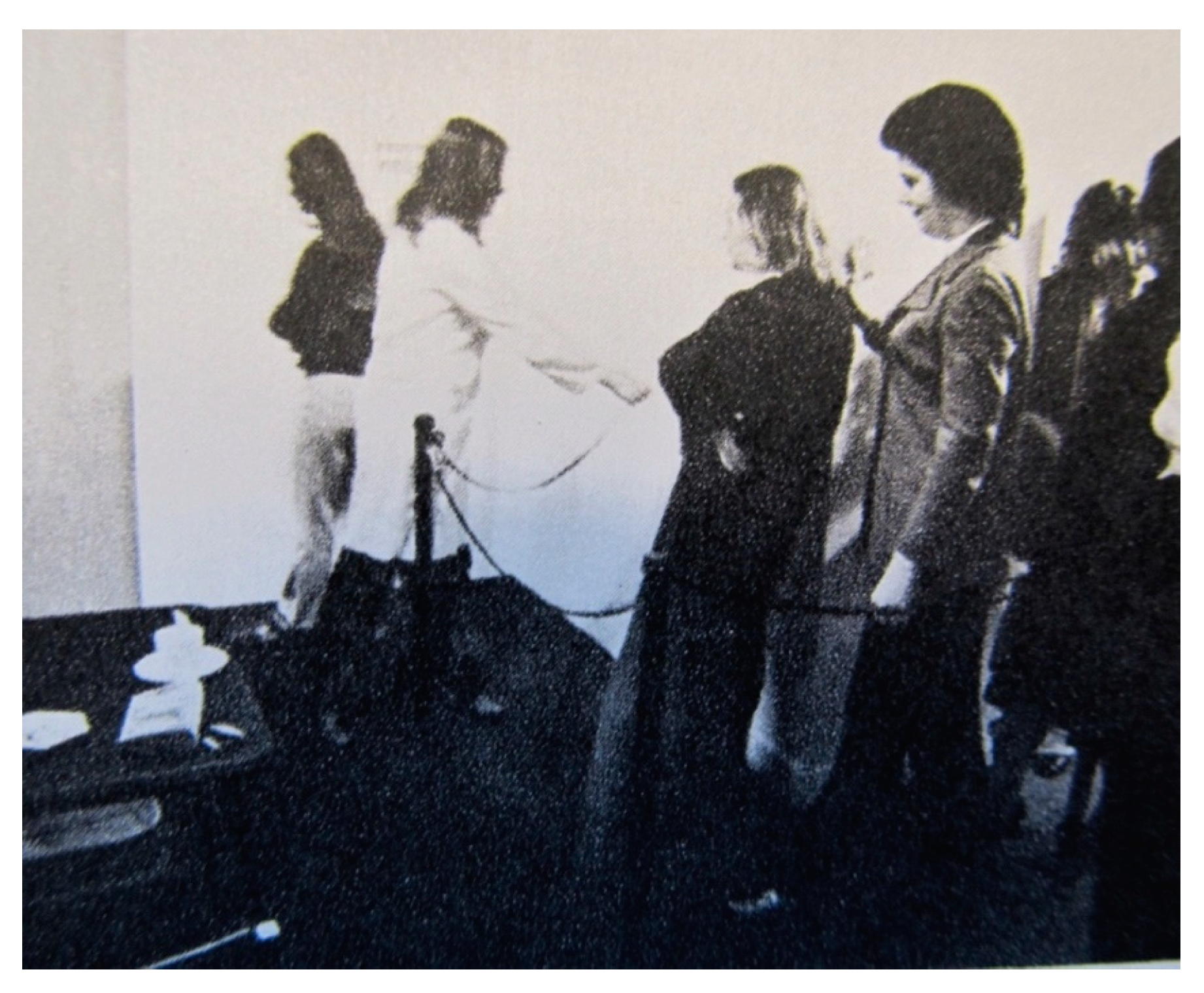

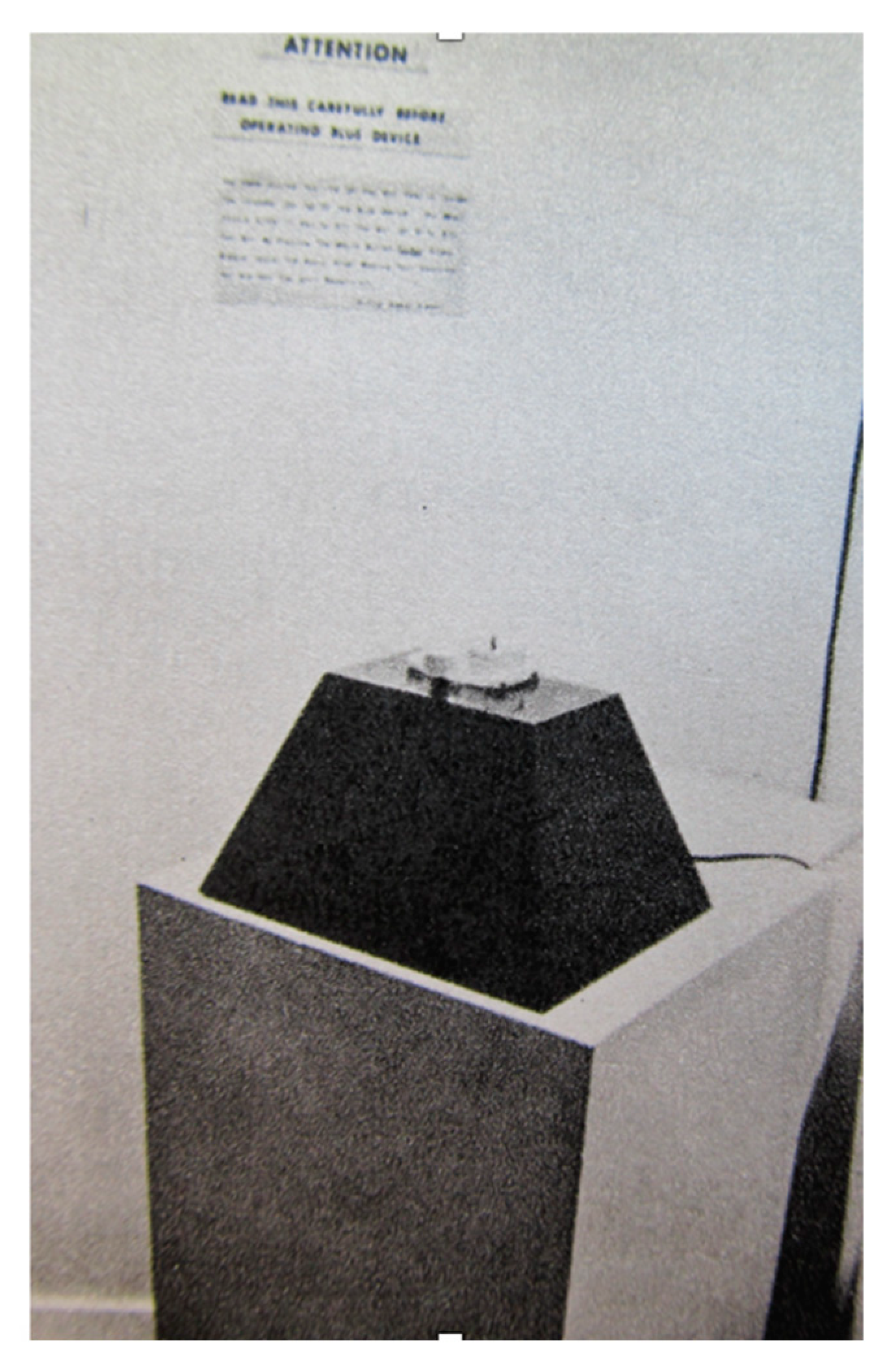

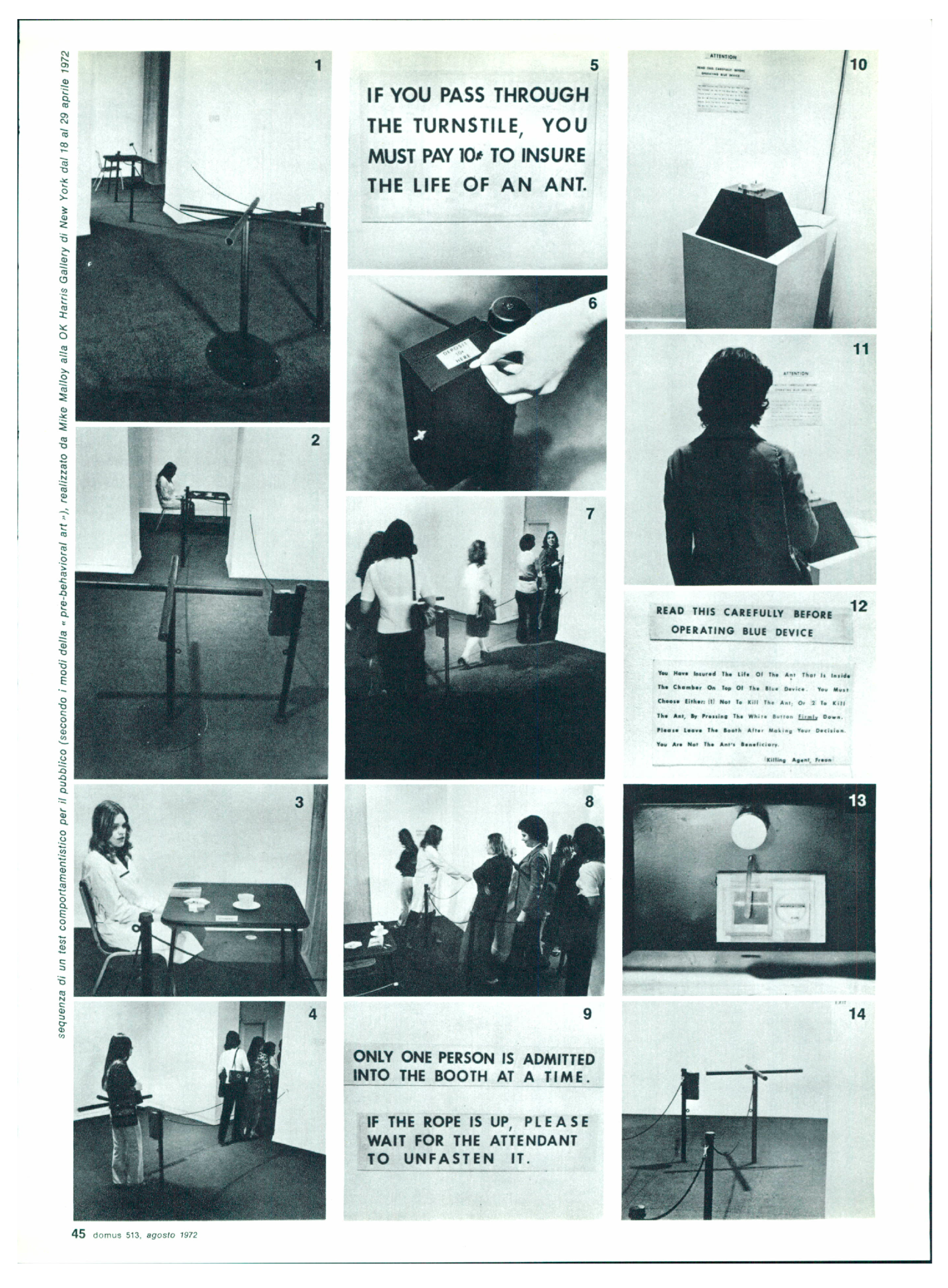

| 21 | (Battcock 1972a, p. 45). All quotations are taken from the Arts Magazine version. Curiously, when this essay later appeared in (Battcock 1977), he chose to use the earlier Domus version (pp. 43–56). |

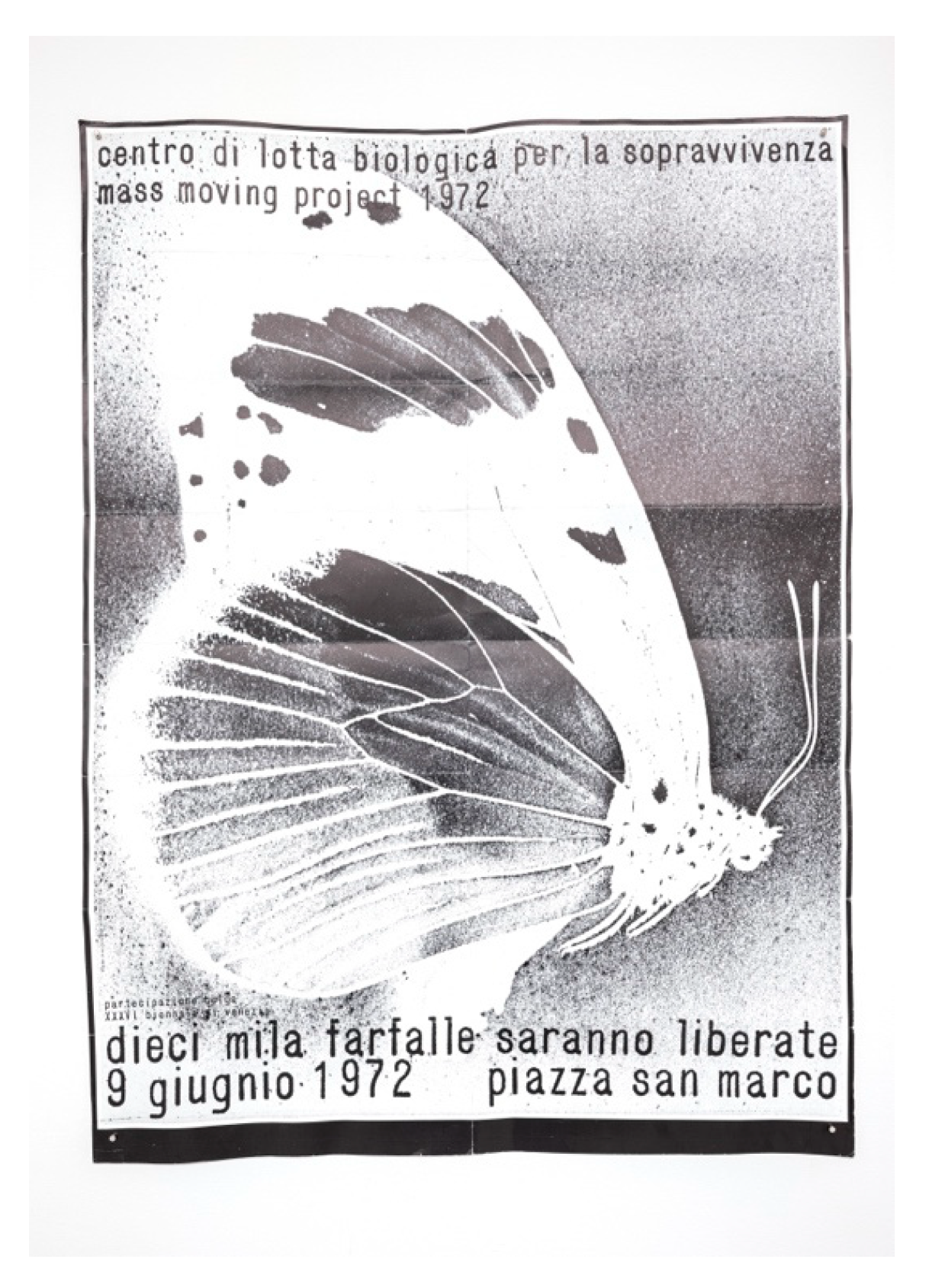

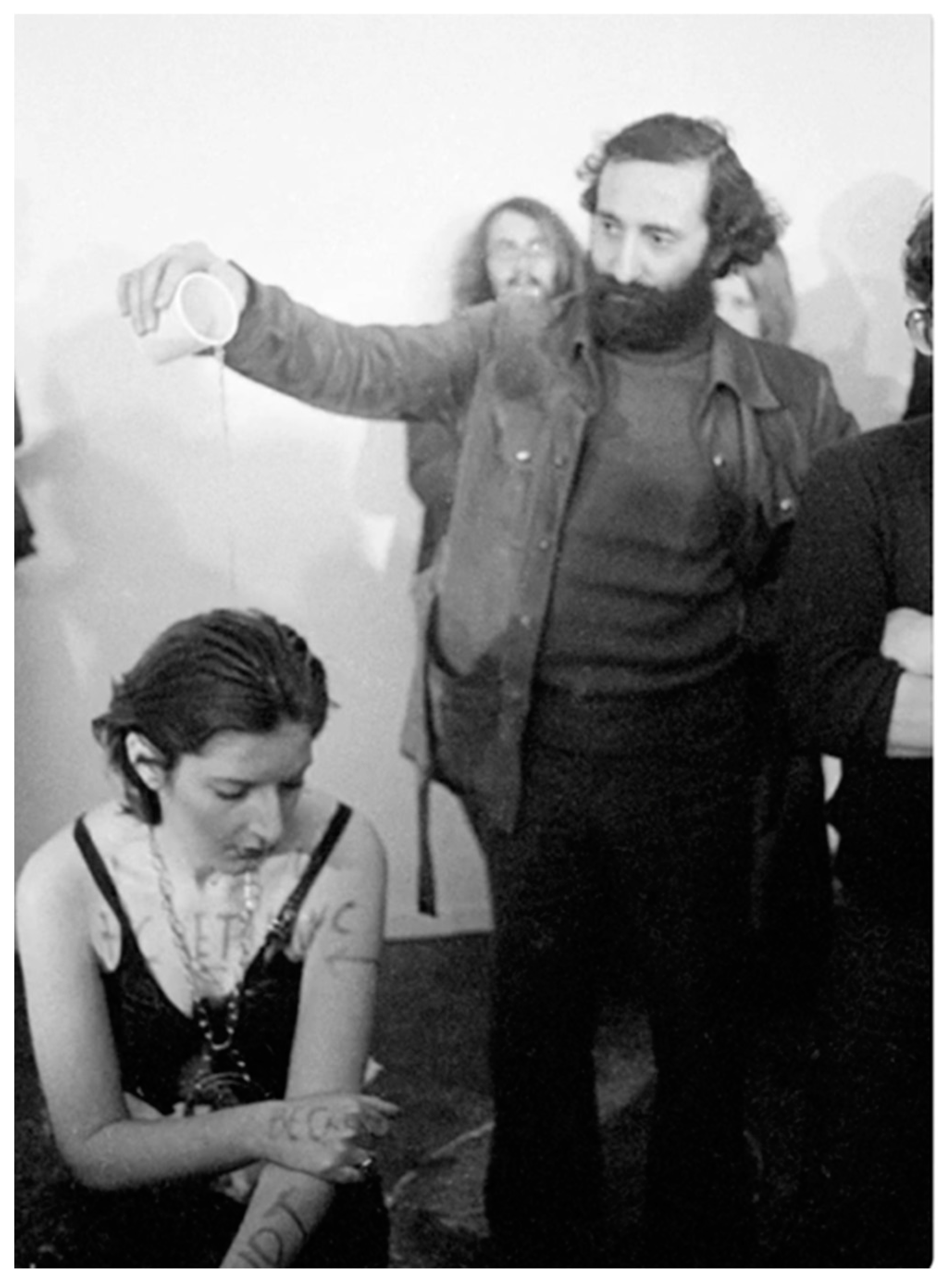

| 22 | Belgian artist Raphaël Opstaele, with the group, Mass and Individual Moving, made the The Butterfly Project as one of that country’s entries to the Biennale. Nearly 25,000 larvae were first cultivated in France and about ten thousand pupae were flown to Venice shortly before the opening of the Biennale, housed and on display in a corner of Piazza San Marco. The butterflies never quite took to the air, and the “Movers” called it “a beautiful failure”. For more on the project see the entry from the recent exhibition, “Mass (and Individual) Moving”, held in late 2023 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp: “Ten thousand butterflies will be released (Tienduizend vlinders zullen worden vrijgelaten)” M HKA Ensembles. Dieci mila farfalle saranno liberate (Tienduizend vlinders zullen worden vrijgelaten) by Mass Moving, 1972; https://ensembles.org/items/dieci-mila-farfalle-saranno-liberate; also see: (Opstaele 1972). The most controversial work in the Venice fair was Gino De Dominicis’ Second Solution of Immortality (The Universe is Motionless). This installation, which had appeared in earlier displays in a somewhat different form, became problematic because it now included a man with Down’s Syndrome seated in the corner of the room as one of its elements. This proved so vexatious that he was replaced with a young girl who did not have the syndrome. Eleonora Charans argues that the overall composition of the work has been misunderstood; her important essay reconstructs its true appearance as an installation juxtaposing a variety of living and fabricated components, including a dog skeleton. See (Charans 2016). Maurizio Cattelan, Massimiliano Gioni, and Ali Subotnick, part of the Wrong Gallery of New York, re-staged the piece at the Frieze Art Fair in London in 2006, using a girl with Down’s Syndrome. Also see note 4. In 1975, De Dominicis had an exhibition entitled, “Exhibition for Animals Only”, which forbade humans from entering the gallery but had peepholes allowing for glimpses of the animals inside (goose, ox, donkey, hen, etc.). |

| 23 | (Battcock 1972a, p. 45). |

| 24 | Artforum 11:1 (September, 1972). Artforum did not review Insure the Life of an Art. It did review Malloy’s 1975 installation, Shelves. See note 17. In the “Introduction” to his anthology (Battcock 1973), he makes use of the term “post-Modernist” for apparently the first time in his writings, lumping Pop, Minimal, and Conceptual art into this category (p. 9). |

| 25 | E-mail correspondence with the artist, March, 2024. |

| 26 | (Miller n.d.). |

| 27 | There is neuroscientific and psychobiological scholarship that argues that understanding the emotional and psychological conditions of animals can encourage animal welfare advocacy. See (Coria-Avila et al. 2022). Also see: (Freund et al. 2016). Also see notes 5 and 6. |

| 28 | Mike Malloy, “TURNSTILE-BOOTH SITUATION #1”, undated, typewritten page, (Gallery 98 Archives). See (Miller 2015). |

| 29 | (Miller 2015, n.d.) |

| 30 | The Eugenia Butler Gallery was an important space in Los Angeles, mounting landmark and cutting-edge conceptual shows, including work by Michael Asher, John Baldessari, James Lee Byars, Douglas Huebler, Ed Kienholz, Joseph Kosuth, Dieter Roth, Allen Ruppersberg, and Lawrence Weiner. Malloy’s Cemetery Piece is included in Lucy Lippard’s groundbreaking book: (Lippard 1973, pp. 242–43). |

| 31 | E-mail correspondence with the artist, 2024. |

| 32 | See note 29. |

| 33 | My intention is not to provide an authoritative list of participatory, situational, interactive, or behaviorist art in this essay. For mention of “relational aesthetics”, see note 4. |

| 34 | See (Milgram 2005). A compelling and disquieting documentary of the experiment can be found in Milgram’s 1962 film, Obedience. |

| 35 | (Arendt 1963). This material first appeared as a series of essays in the New Yorker in 1963. These subjects are examined in many of Arendt’s prolific writings. |

| 36 | There is substantial literature on the controversial Milgram Experiment, and many have questioned its methods and ethics. After the initial experiment, it was repeated multiple times with variations that were often designed to neutralize certain factors felt to create bias. Though some iterations produced slightly different results, the takeaway remained that some subjects still seem willing to inflict apparent pain. Ethical concerns about the experiment helped to bring about changes in guidelines by the American Psychological Association for treatment of human subjects in studies. Later in the body of this essay, I discuss guidelines established by the College Art Association regarding treatment of human and non-human animals in art. |

| 37 | As one might imagine, other artists have used live ants in their art, most done later than Malloy’s. Worth mentioning is a group of works by Argentinian artist Luis Fernando Benedit, which began in 1968 and continued up through 1972, when Malloy’s piece was on display. Benedit employed groups of live ants more positively in habitats and labyrinths that he designed as works of art. Part of a series that a leading critic called “biological-physical-chemical experiences”, they involve live plants, animals, and humans, intended to counteract hierarchies among these organic worlds. |

| 38 | Myrmecologist E. O. Wilson, who helped develop the field of sociobiology, is the most famous writer about the life of ants. He won, with Bert Hölldobler, the Pulitzer Prize in 1991 for the popular and finely illustrated book: (Wilson and Hölldobler 1990). |

| 39 | I want to make clear that this refers to works of art that are harmful to actual animals. It can be argued that depictions of animals in art might portray them in ways that contribute to a climate of misunderstanding and mistreatment. While such work might promote a troubling mindset about animals, it is qualitatively different from art involving improper treatment of live or once-living non-human animals. In this regard, the most infamous abusive piece, created just five years after Malloy’s, is Tom Otterness’ killing of a dog as a filmed artwork called Shot Dog Film (1977), a far moral cry from Malloy’s invitation to voluntarily exterminate an insect. Closer in spirit to Insure the Life of an Ant is Rick Gibson’s 1986 Kill a Bug, a combination of street cart and baby stroller, which he wheeled along a popular street in the waterfront city of Plymouth, UK. The apparatus carried bugs in containers and a selection of insecticides, and he invited passers-by to “kill a bug”. Taking the moral and ethical art zone to the streets, Gibson offers an uncomfortable mélange of somewhat opposing associations: pest control, the beginning of life associated with babies, and street carts purveying products. In the spirit of Milgram, Gibson also made the coin-operated Pain Dispenser in 1984, on which is written: “Hey! Give Yourself a Painful Shock for only 5P”. Known for controversy, Gibson planned to squash a rat between two canvases as performance art; the event was stopped by local authorities and the piece confiscated. Later Gibson was pursued by an angry crowd objecting to this project, as the affect of the piece came back to haunt its producer. |

| 40 | As mentioned, Insure the Life of an Ant may relate to contemporaneous death penalty debates. Evaristti has made several works addressing this theme, too. His FIVE2TWELVE of 2007 focuses on an American death row inmate, whom the artist visited in prison, where a nearby graveyard contained those previously executed, with grave markers bearing only numbers, not names. The inmate, Gene Hathorn, wrote poetry and made drawings, and Evaristti used these along with his own work in an animated film by Sara Koppel, scored by Kenneth Thordal, entitled Death Town, made in 2008. Evaristti also received permission from the prisoner to use his body after death as fish food (an animal appearing periodically in the artist’s oeuvre), as part of an exhibition where visitors would feed fish in a large aquarium. Hathorn’s sentence was reversed, and he is now serving a double life sentence instead. This death row visit also inspired Evaristti’s The Last Fashion (2008), a clothing line informed by his learning that death-row inmates were issued fresh attire for their executions. See: (Evaristti Studios 2008). Also, (Grøn and Erritzøe 2013, pp. 116–33). I should add that much of Evaristti’s fascinating oeuvre, despite its sometimes outrageous character, interrogates difficult issues surrounding government, ecology, and, as seen, mortality. He also has put his own life in danger in his art, an idea I examine later in the essay in regard to risk-tasking artists. |

| 41 | Michael Malloy stopped producing art at some point in the mid-to-late 1970s. Malloy’s current career as owner of a high-end international insurance company may suggest an ironic continuation of concepts that preoccupied him as an artist, though he recently described it as “two very different expressions of something at different times”. He is a leader and expert in his current field, authoring two books and producing over 100 videos on the subject. E-mail correspondence, 2024. |

| 42 | See: (Evaristti Studios 2000). At the 2000 Trapholt showing, these components of the piece were laid out in a manner that might not make clear their connection to each other. In subsequent displays at Trapholt in 2012, 2013 and 2017, the work was arranged a bit differently each time (see Figure 12, for one example). In each of the these later instances, however, the elements are clearly linked together in a more linear fashion. As well, Helena & El Pescador no longer has live fish in water. Instead, plastic versions of goldfish are suspended in silicon jelly. I am grateful to the staff at the Trapholt Museum, especially curator Katrine Stenum Poulsen, for clarifying issues about the installations. |

| 43 | Interview with Marco Evaristti by the author, Summer, 2017. |

| 44 | |

| 45 | (Frank and Readers 2008, p. 31). Eric Frank moderated the intriguing enterprise in which H-Animal Net, a website for Animal Studies Scholars, invited the community to pose questions for Evaristti. As Antennae editor Giovanni Aloi wrote in the introduction to this issue, the event “triggered one of the most heated threads the site has hosted to date”. (Aloi 2008a, p. 2). Also see: (The Goldfish Thread 2008; Aloi 2008b). |

| 46 | See for example, (Black 2009). Also see notes 5 and 50. |

| 47 | |

| 48 | (Frank and Readers 2008, p. 32). |

| 49 | College Art Association, “Standards and Guidelines, The Use of Animal Subjects in Art: Statement of Principles and Suggested Considerations” October 23, 2011. https://www.collegeart.org/standards-and-guidelines/guidelines/use-of-animals (accessed on 25 March 2024). |

| 50 | (Singer 1975). There is hardly unanimity about the assertions of Singer, a controversial philosopher who popularized this term and whose positions on animal welfare are inconsistent. For example, Singer offers tepid justification of Evaristti’s Helena because he believes it instructively “raise(s) the question of the power we do have over animals”. See (Boxer 2000). It is generally agreed that “speciesism” was coined by animal rights advocate Richard D. Ryder in a privately published pamphlet in 1970. See (Ryder 2010). See, as well, (Ryder and Singer 2015). Ryder supports the use of terms such as “sentientism” and “painism” (which he coined) to describe a range of feelings that organisms experience to argue for their moral standing. Also see note 6. |

| 51 | The image of damaged clothing revealing body skin might also refer to photos of Japanese victims of American atomic bombs during World War II. In 1971, Ono made a conceptualist work that apparently included animals, and its exact description remains imprecise. Called Museum of Modern [F]art, she advertised her putative one-woman show at MoMA, which included a self-made catalogue. She claimed to have released flies scented with her favorite perfume from the center of the galleries (though a “collaged” photo in her “catalogue” shows her and a large bottle of flies in the sculpture garden), inviting the public to join her in observing their flight or sniffing out their trails. Those who ventured to MoMA to see this exhibition found only traces: MoMA’s posting of her ad on a ticket window announcing—“THIS IS NOT HERE”—and a man (with a camera and sandwich board) outside the museum who asked questions and offered information about this fictive event. With partner John Lennon, Yoko made a film around this time (1970-1), entitled Fly, which shows a single fly and then a group of flies traversing a nude woman’s body, accompanied by a soundtrack that would appear on her 1971 album, “Fly”. Because instructions are central to Malloy’s work, it should be mentioned that instructions figure prominently in Ono’s career. As early as 1955 she made Lighting Piece, one of her “instruction pieces”, as she called them, consisting of a small typewritten card affixed to the wall, reading: “Light a match and watch till it goes out”. |

| 52 | The art career of Edward Kienholz spans from 1954 to 1994. Works created between 1972 and 1994 are considered jointly authored by him and his wife Nancy Reddin, who continued to produce pieces after Ed’s death in 1994 until her death in 2019. There are excellent writings on Edward Kienholz, especially in exhibition catalogues. One essay that treats Still Live in greater detail is: (Willeck 2008). Also see my own essay: (Silk 1997). The L. A. Louver Gallery has represented Edward and Nancy Kienholz since 1981 and has organized numerous solo exhibitions at the gallery in Venice Beach, CA and traveling exhibitions in collaboration with art museums throughout U.S., Europe, and Japan. Lauren Graber, head archivist and research specialist at L.A. Louver, was helpful with queries about the artists. Graber presented a paper at the College Art Association meetings in Chicago in February 2024: “Meditations on Gun Violence: Edward and Nancy Kienholz’s ‘Still Live’ Tableau and Drawings”. Still Live was exhibited at the Braunstein Gallery in San Francisco in 1982. People sat in the chair but there seems not to have been efforts to ban the work. Except for a few reports on local television, there was not as much coverage as one might expect. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zyQLcsZw4K8 (accessed on 25 March 2024). |

| 53 | (Kienholz 1975): n.p. Just recently, a failed effort to execute a death-row inmate in Idaho by lethal injection has led to considering use of a firing squad. |

References

- Aloi, Giovanni. 2008a. Editorial. Antennae, The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture 5: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Aloi, Giovanni. 2008b. The Death of the Animal. Antennae, The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture 5: 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Aloi, Giovanni. 2012. Art and Animals. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Aloi, Giovanni. 2018. Speculative Taxidermy: Natural History, Animal Surfaces, and Art in the Anthropocene. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Hannah. 1963. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York: Viking Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Steve. 2013. Artist/Animal. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bartram, Ang. 2023. Art and Animals and the Ethical Position. Arts. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/arts/special_issues/Art_Animals_Ethical_Position (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Battcock, Gregory. 1972a. Toward an Art of Behavioral Control: From Pigeons to People. Arts Magazine 47: 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Battcock, Gregory. 1972b. Toward an Art of Behavioral Control: From Pigeons to People. Domus 513: 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Battcock, Greogry. 1973. Idea Art: A Critical Anthology. New York: Dutton. [Google Scholar]

- Battcock, Gregory. 1977. Why Art: Casual Notes on the Aesthetics of the Immediate Past. New York: Dutton. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News. 2003. Liquidising Goldfish Not a Crime. Available online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/3040891.stm (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Bennett, Jill. 2005. Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Jill. 2012. Practical Aesthetics: Events, Affects and Art after 9/11. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bentham, Jeremy. 1789. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. London: T. Payne and Son. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, Claire. 2004. Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics. October 110: 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, Claire. 2023. Artificial Hells. Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Harvey. 2009. Underwater Suffering: Do Fish Feel Pain? Scientific American. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/underwater-suffering-do-fish-feel-pain/ (accessed on 22 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Bourriaud, Nicolas. 1998. Esthétique Relationnelle. Dijon: Les Presses du Reel. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer, Sarah. 2000. Animals Have Taken Over Art, And Art Wonders Why; Metaphors Run Wild, but Sometimes a Cow Is Just a Cow. New York Times. 14 June. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2000/06/24/arts/animals-have-taken-over-art-art-wonders-why-metaphors-run-wild-but-sometimes-cow.html (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- B.S. 1972. Mike Malloy [O.K. Harris]. Art News 71: 54. [Google Scholar]

- Charans, Eleonora. 2016. Work (and) Behaviour: Gino De Dominicis at the 36th Venice Biennale. In Histoire(s) d’exposition(s); Exhibitions’ Stories. Edited by Bernadette Dufrêne and Jérôme Glicenstein. Paris: Hermann Glassin, 6 May. pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chayka, Kyle. 2011. WTF Is… Relational Aesthetics? Hyperallergic. Available online: https://hyperallergic.com/18426/wtf-is-relational-aesthetics/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Coria-Avila, Genaro A., James G. Pfaus, Agustín Orihuela, Adriana Domínguez-Oliva, Nancy José-Pérez, Laura Astrid Hernández, and Daniel Mota-Rojas. 2022. The Neurobiology of Behavior and Its Applicability for Animal Welfare: A Review. Animals 12: 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenman, Stephen F. 2013. The Cry of Nature: Art and the Making of Animal Rights. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins, James. 1998. On Pictures and the Words That Fail Them. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins, James. 2001. Pictures & Tears: A History of People Who Have Cried in Front of Paintings. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins, James, ed. 2005. Art History Versus Aesthetics. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Evaristti Studios. 2008. FIVE2TWELVE. Available online: https://www.evaristti.com/five2twelve-1#:~:text=In%20December%202007%20Marco%20Evaristti,he%20had%20committed%20a%20murder (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Evaristti Studios. 2000. Helena & El Pescador. Available online: https://www.evaristti.com/helena-el-pescador-1 (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Frank, Eric, and H-Animal Readers. 2008. Marco Evaristti: “Helena”. Antennae, The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture 5: 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg, David. 1989. The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, Lisa S., Sandra McCune, Layla Esposito, Nancy R. Gee, and Peggy McCardle, eds. 2016. The Social Neuroscience of Human–Animal Interaction. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1chrsqs (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Grøn, Karen, and Malou Erritzøe, eds. 2013. Marco Evaristti. Kolding: Kunstmuseet Trapholt. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Marcia. 2024. Special Issue Information. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/arts/special_issues/Affective_Art (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Heinemann, Susan. 1975. Reviews: Michael Malloy; 3 Mercer Street. Artforum 13: 76. [Google Scholar]

- Jury, Louise, Sophie Goodchild, and Lucy Jones. 1999. Artists to Boycott New York Show. The Independent 25 September: London, 6. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/artists-to-boycott-new-york-show-1122375.html (accessed on 21 December 2004).

- Kienholz, Edward. 1975. Edward Kienholz: Still Live: Aktionen der Avantgarde, Projekt für ADA2. Berlin: Neuer Berliner Kunstverein. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Eunsong. 2015. Neoliberal Aesthetics: 250 cm Line Tattooed on 6 Paid People. Lateral. 4, n.p. Available online: http://csalateral.org/issue/4/neoliberal-aesthetics-250-cm-line-tattooed-on-6/ (accessed on 30 August 2017).

- Linze, Andrew, and Paul A. B. Clarke. 2005. Animal Rights: A Historical Anthology. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lippard, Lucy. 1973. Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Lubell, Ellen. 1972. Mike Malloy [O.K. Harris]. Arts Magazine 46: 61. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, Stanley. 2005. Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View. New Edition. London: Pinter & Martin Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Marc. 2015. Mike Malloy’s “Insure the Life of an Ant,” 1972: Documents Discovered for Transgressive Art Piece. “Gallery 98”. 27 August. Available online: https://gallery.98bowery.com/news/mike-malloys-insure-the-life-of-an-ant-1972/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Miller, Marc. n.d. Conceptual Art: 1969–78: Mike Malloy. “98 Bowery: 1969–89—View from the Top Floor”. Available online: https://98bowery.com/first-years/mike-malloy (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 2022. Justice for Animals: Our Collective Responsibility. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Opstaele, Raphaël August. 1972. The Butterfly Project: Cocoon Incubator, Piazza San Marco, Venice, IT. Forgotten Heritage. Available online: https://www.forgottenheritage.eu/artworks/1294/the-butterfly-project-cocoon-incubator-piazza-san-marco-venice-it#:~:text=%C2%BBThe%20Butterfly%20Project%C2%AB%20became%20one,Piazza%20San%20Marco,%20in%20Venice (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Panksepp, Jaak. 1998. Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp, Jaak. 2011. The Basic Emotional Circuits of Mammalian Brains: Do Animals Have Affective Lives? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 35: 1791–804. [Google Scholar]

- Rancière, Jacques. 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics. Translated by Gabriel Rockhill. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder, Richard D. 2010. Speciesism Again: The Original Pamphlet, Richard Ryder. Critical Society 2: 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder, Richard D., and Peter Singer. 2015. Speciesism, Painism and Happiness: A Morality for the Twenty-First Century. Luton: Andrews UK Limited. Available online: http://site.ebrary.com/id/11171725 (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Silk, Gerald. 1997. Censorship and Controversy in the Career of Edward Kienholz. In Suspended License: Essays in the History of Censorship and the Visual Arts. Edited by Elizabeth Childs. Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 259–98. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Peter. 1975. Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for our Treatment of Animals. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein, Cass R., and Martha C. Nussbaum, eds. 2004. Animal Rights: Current Debates and New Directions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Goldfish Thread. 2008. Antennae, The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture 5: 33–42.

- University of Chicago. 1965. Panel at University of Chicago Law School Discuss Ending Capital Punishment, Part 3. Studs Terkel Radio Archive. 19 February. Available online: https://studsterkel.wfmt.com/programs/panel-university-chicago-law-school-discuss-endingcapital-punishment-part-3?t=11.83,35.35&a=ShipItOver,BeenAbleTo (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Venkataraman, Bina. 2023. Is Guilt-Free Meat Possible? Washington Post. 3 June. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/07/03/lab-grown-chicken-meat-eating-guilt/?nid=top_pb_signin&arcId=SA7HMIAMBBKJGHGSGTTESSVDM&account_location=ONSITE_HEADER_ARTICLE (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Wacks, Raymond. 2024. Animal Lives Matter: The Quest for Justice and Rights. London: Routledge. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781032702575 (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Wallis, Jonathan. 2012. Behaving Badly: Animals and the Ethics of Participatory Art. Journal of Curatorial Studies 1: 315–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willeck, Damon. 2008. The Theatrics of Kienholz Tableaux. Art Lies 60: 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Edward O., and Bert Hölldobler. 1990. The Ant. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zammit-Lucia, Joe. 2014. Practice and Ethics of the Use of Animals in Contemporary Art. In Oxford Handbooks Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silk, G. Affect and Ethics in Mike Malloy’s Insure the Life of an Ant. Arts 2024, 13, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13030101

Silk G. Affect and Ethics in Mike Malloy’s Insure the Life of an Ant. Arts. 2024; 13(3):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13030101

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilk, Gerald. 2024. "Affect and Ethics in Mike Malloy’s Insure the Life of an Ant" Arts 13, no. 3: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13030101

APA StyleSilk, G. (2024). Affect and Ethics in Mike Malloy’s Insure the Life of an Ant. Arts, 13(3), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13030101