Abstract

Ajami, a technique of painted wood paneling, was popular in the Ottoman Empire from the 17th to the late 18th centuries. Ajami art became prominent in Syria after the decline of tile production, and it rose to a sophisticated level of art in both local and global markets. Today, however, Ajami art has become almost forgotten and unknown by the modern generation, due to being an exclusive art that can be seen only in palaces, museums, and historical houses. This study investigates the traditional method and techniques of making Ajami, with a focus on the work of a renowned Syrian Ajami art master artisan named Mr. Abdulraouf. The study aims to identify and document the traditional method of Ajami production and determine the materials and techniques used for making Ajami. The study found that Ajami art consists of natural elements that are utilized in four main stages; foundation, design, painting, and finishing. The artisans have a strong preference for floral and geometric designs, influenced by Islamic religious beliefs. The findings of this study could serve as an educational guide to preserve heritage and make it presentable for the present and future generations.

1. Introduction

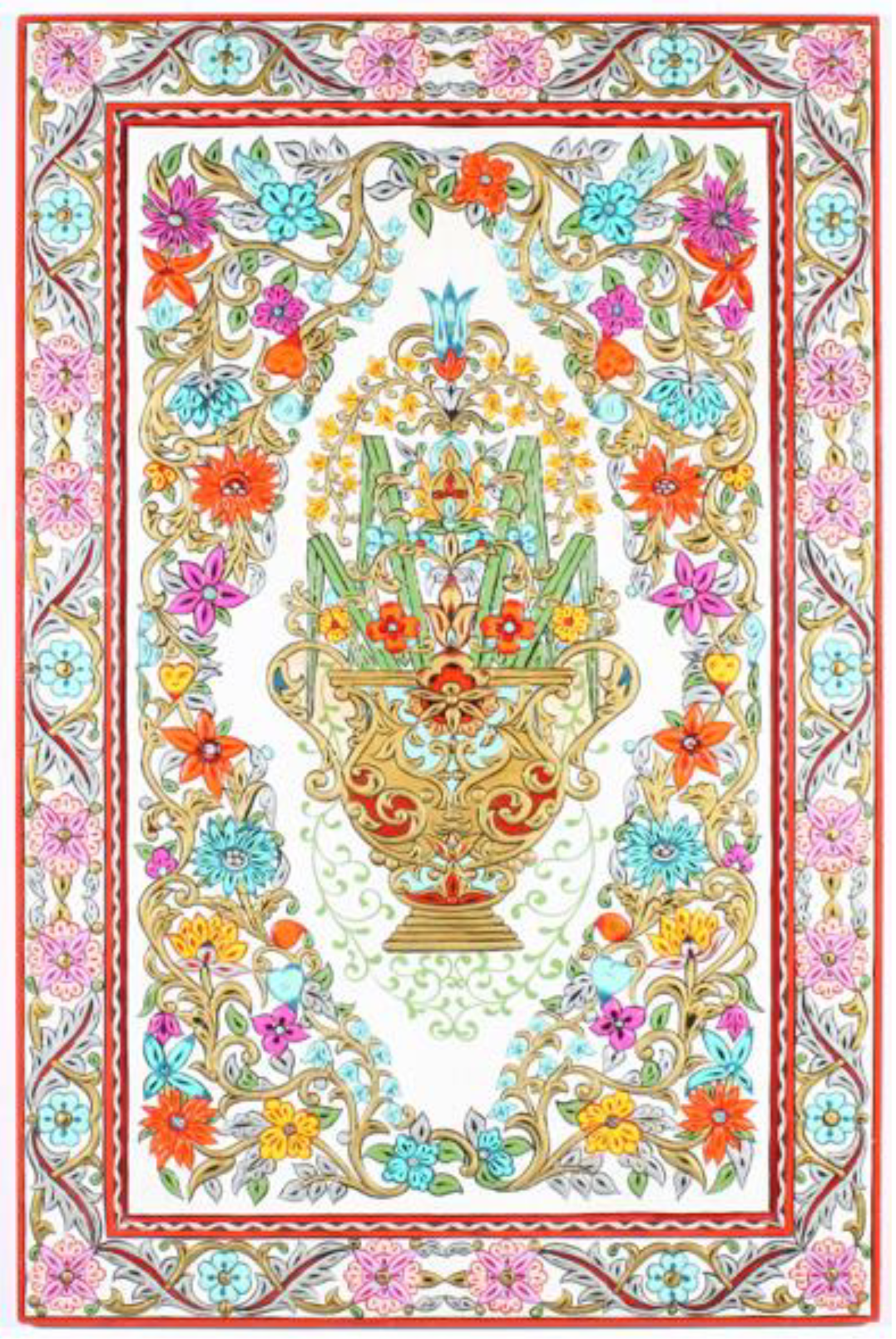

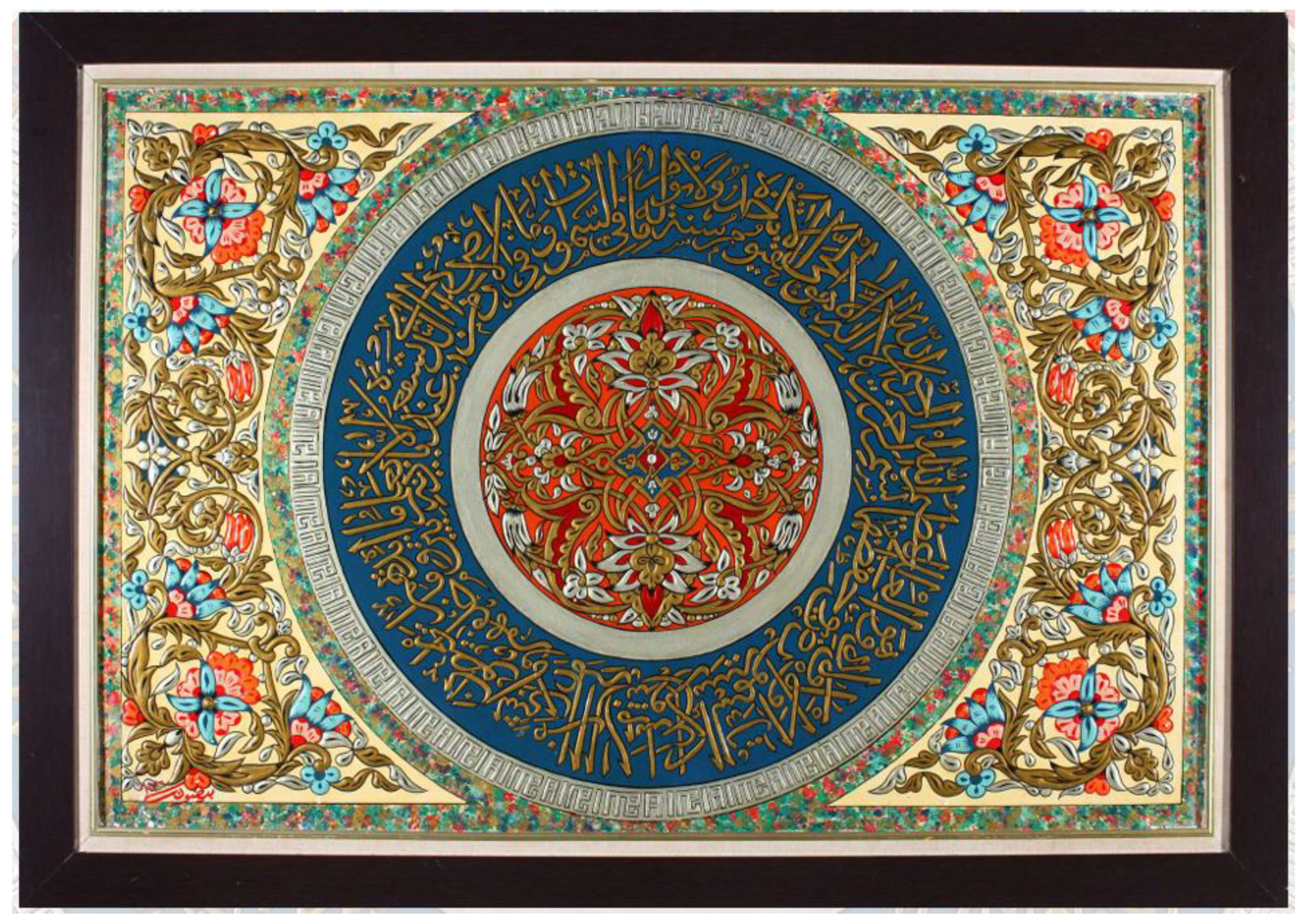

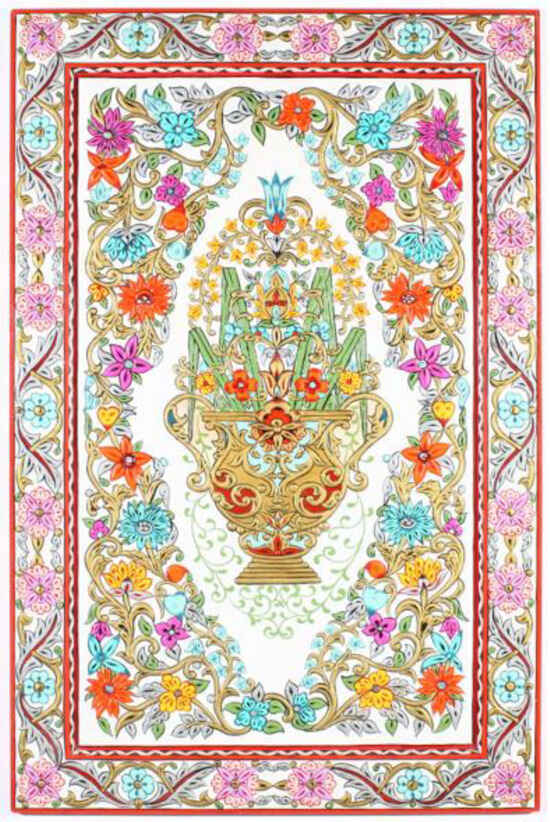

The city of Damascus, the capital of Syria, ushers visitors to a magnificent piece of human history. This city is considered by many historians to be one of the oldest inhabited cities in the world (Foss 2017). Damascus is a major cultural and religious center that has many historical buildings, including palaces, houses, and mosques that are internally decorated with one of the most attractive Islamic artworks, called Ajami art, in a combination of geometric and floral elements (Mohammed and Ibraheem 2015). Ajami art is an ancient woodwork technique that has become an intangible heritage of Syria, since it was uniquely invented by Syrians. In Syria, the richly painted and metal-leaf-covered wooden interiors are named Ajami rooms (Kenney 2018). It has been estimated that between the 17th and 19th centuries, thousands of Ajami rooms were built and existed within the walls of the ancient city. The Arabic term Ajami refers to the Persian or non-Arabic art; it is used to describe the technique and the ornaments as well as the interiors. Ajami refers to painted wooden wall panels, and the oldest surviving Ajami artworks are in the reception room of a grand house in Aleppo and inscribed with the dates 1600 and 1603. This decorative style of Ajami is also called “Pastiglia” (an Italian term meaning “paste work”) in Europe and appeared as early as the Umayyad times (Mravik et al. 2019). The Ajami decorations became very prominent throughout the Ottoman Empire, and they flourished in Syria. This kind of interior decoration reached its peak in the 17th century in town houses in the Syrian province (Baydoun and Kamarudin 2018). Some examples of Ajami artwork are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2 below.

Figure 1.

Completed floral Ajami artwork.

Figure 2.

Completed Ajami artwork with Islamic calligraphy.

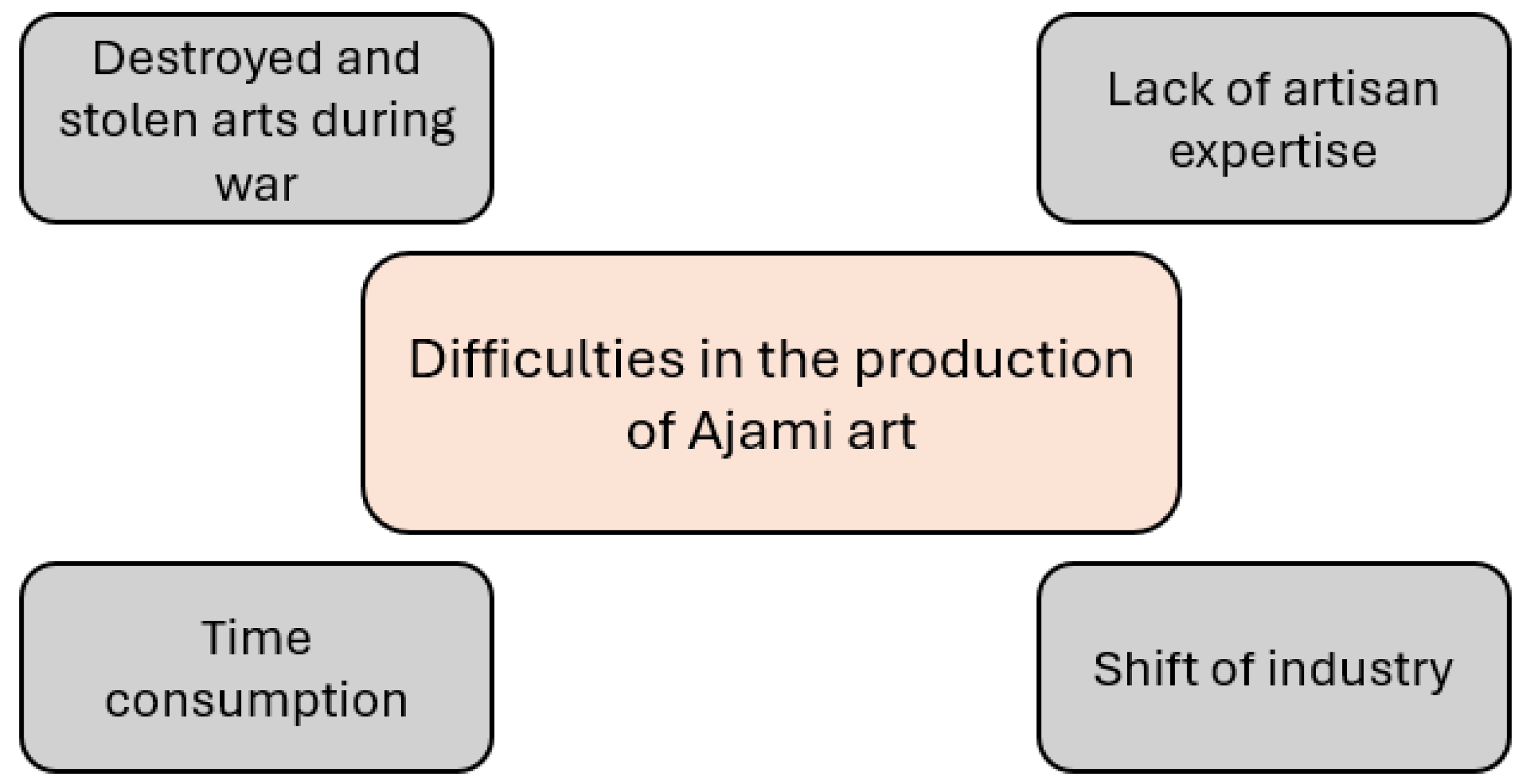

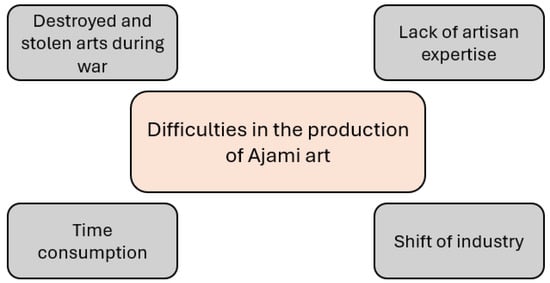

The difficulty of Ajami art production is one problem that has caused a severe decline in the popularity of the art. This is mainly because the production of Ajami art requires a high level of skillfulness and specialized workmanship. In other words, Ajami art requires expert artisans to produce this type of art on wood (Osadola et al. 2021). Furthermore, the production of Ajami is time-consuming, it involves a long process to prepare the materials required and apply them on wood. Usually, only gifted artisans are familiar with the traditional Ajami and have considerable experience in performing this job in the best way possible. Therefore, Ajami art is considered as one of the most difficult applied arts in the world. Furthermore, many industries have shifted from producing Ajami to focusing more on contemporary and modern workshops due to the insufficient knowledge and experience of existing artisans. Nowadays, modern machines such as laser machines, printers, carving machines, and many other machines can copy any design, and this provides substitutes for handmade artwork (Dash et al. 2019). Nevertheless, Ajami art requires professional people who are well trained to draw, apply 2D and 3D materials, and color the designs of decorative wood panels. The art of Ajami is facing a lack of expert artisans with such skills and recognition. In addition, since 2011, many places have been destroyed by the war in Syria, which has also affected the Damascene traditional houses and palaces. Figure 3 shows some of the difficulties faced in Ajami art production.

Figure 3.

Difficulties for Ajami art production.

Ajami art holds high value due to its historical value. Hence, an effort must be exerted to discover the traditional technique of making Ajami before it disappears. It is vital to document the old technique from the highly experienced artisans who are a remnant of the pride of the old days and who are still alive. This would ensure that the artwork can be preserved for future generations, to ensure its continuity of production (Alafandi and Rahim 2016). Many works of local and international scholars have emphasized the application of Syrian Ottoman art in Turkey and Syria. Researchers have classified this art, including Ajami art, as a part of the interior decoration in Damascene houses in Syria (Meis 2016). The studies investigate the meaning and significance of applying Ajami art and preserving this inherited art from the devastating effects of the war in Syria, as well as keeping Ajami art to preserve the civilizations and the identity of Syria during its flourishing period (Alafandi et al. 2016). However, the literature survey indicates that there is a lack of in-depth research on traditional Ajami art on wood paneling. Most of the literature generally focuses on art and decoration in Damascene houses. There is a limited amount of research that elaborates on the types of method and techniques used for Ajami art. This research aims to investigate all the steps involved in Ajami production by focusing on its traditional method and techniques. The research rediscovers the technique through a semi-structured interview with a prominent Syrian master artisan in Syria. The focus of the research is on the materials and how these materials are used to give 3D and 2D effects on the wood via painting composition. The selected artisan is one of the few remaining experts in Syria who produce Ajami as an inherited Syrian art. This study focuses on all aspects of the method and techniques of Ajami, to propose a production manual of Ajami products as an output of the study. This manual can be developed into a course which can be taught in art and heritage universities so that Ajami can survive for future generations.

2. Literature Review

There are several studies that discuss handmade Ajami art in relation to its heritage and historical values. These previous studies concentrate on the technique, heritage, and value of handmade Ajami art. The study in (Scharrahs 2013) presents research covering Damascus rooms with the use of Ajami techniques in those Syrian-Ottoman interiors. The author suggests that these rooms are the witness of the glory of artwork in the 17th century; however, it is almost forgotten. That study was conducted to make this masterpiece come alive again. Moreover, the study in (Scharrahs 2010) focused on the Syrian–Ottoman Islamic art collection and its history in terms of the original forms of the Ottoman interiors. Meanwhile, the study of A Room of “Splendor and Generosity” from Ottoman Damascus. By (Mathews 1997) covered research on a Damascus room of “splendor and generosity” from the Ottoman period, which is regarded as one of the most popular representations of Islamic art. The study analyzed all the room parts in detail. The authors in (Trevathan and Thiagarajah 2010) discovered that an Ottoman room which is in the Islamic Art Museum in Malaysia is one of the few remaining historical rooms. This room dates from the early 19th century. The researcher focused on the techniques and execution of handmade Ajami art in general. Apparently, the authors in (Mortensen 2005) identified many Syrian–Ottoman arts originating from Syria. Bait Al-Aqqad, for example, was a Syrian–Ottoman Ajami-decorated room that was transported to several places outside Syria. According to the research in (Fair et al. 2010), the Damascus room contains reconstructed decorative panels, giving a better idea of the techniques and materials used. It now resides at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the purpose of reviewing and studying Ottoman interiors. According to research by School Arts Ohio, there has been research on a “Damascus room” that was found at the Cincinnati Art Museum in Cincinnati. The room is emphasized with Ajami, utilizing raised materials and lavish decoration which dated from the beginning of the 18th century, reflecting the Syrian hardships during the Ottoman period (Great Lakes Publishing n.d.). Furthermore, a few authors have investigated the use of handmade Ajami art. For example, the authors in (Ewert 2006) found that all the elements in an Aleppo room, including the structure, decorative details, and paintings, were made of Ajami. The authors in (Gonnella and Kröger 2008) carried out a study which covered an Aleppo room and the Ottoman style in Syria. The authors also studied an oriental house from the 17th century that was related to the Aleppo room. The authors in (Schwed 2006) studied an Aleppo room in Berlin with ornamental and decorative painting from the Ottoman era and carried out a survey on Syrian interior art of the Ottoman Empire. Meanwhile, a study in (Demirarslan 2017) covered the Doris Duke Shangri-La House as a general example of Ottoman art. The analysis was on the Turkish room technique, with an illustration of the painting style, component materials, and raised gesso ornaments that are unique to Ajami art (Baydoun et al. 2017). The authors in (University of Delaware 2018) focused their study on the second stage of the Turkish room preservation project, which included the before and after treatment of the ceiling as well. This study also provides care and maintenance guidelines for the Turkish room. In addition, the authors in (Hassanein and Scheiner 2019) clarified the basic process of the treatment for the Turkish room. This study also presented the objectives of an author distinguished in Arabic literature from the early Ottoman Empire in Syria. Table 1 presents a summary of important related studies, as discussed above. The reviews of related researchers show that even though Ajami is handmade art in relation to its heritage and historical values, there is still a lack of detailed studies on the techniques of Ajami. Limited research focuses on the traditional technique of drawing and producing Ajami art as handmade art, as well as its decorative component. This is perhaps due to the secrecy of Ajami art (which is well kept by old artists) and because of the complexity of the Ajami techniques. The study on this aspect of Ajami is timely and necessary before this art is forgotten. Therefore, we aim to discover the traditional technique of Ajami in detail through a research interview with a master artisan who has decades of experience.

Table 1.

Summary of related studies.

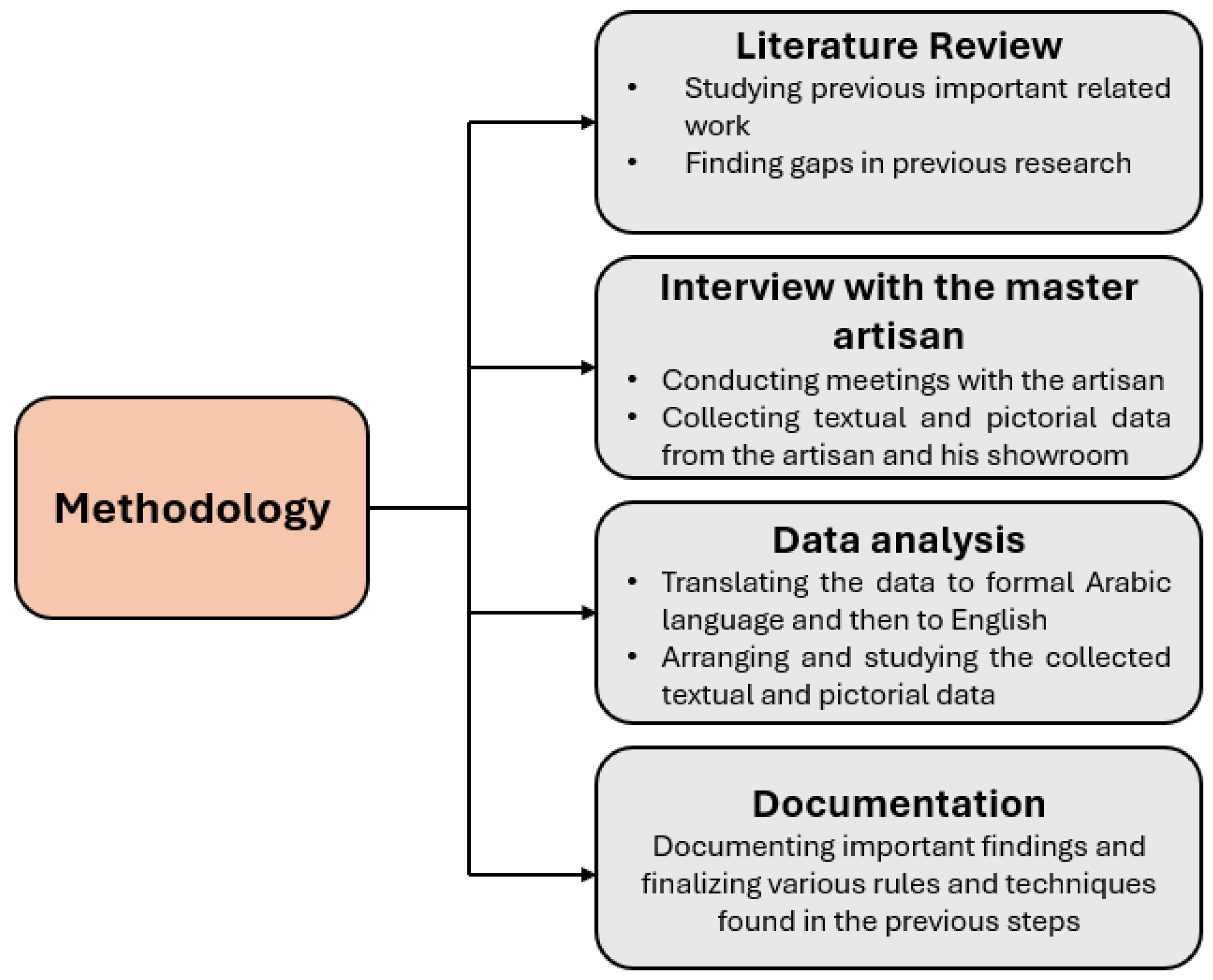

3. Materials and Methods

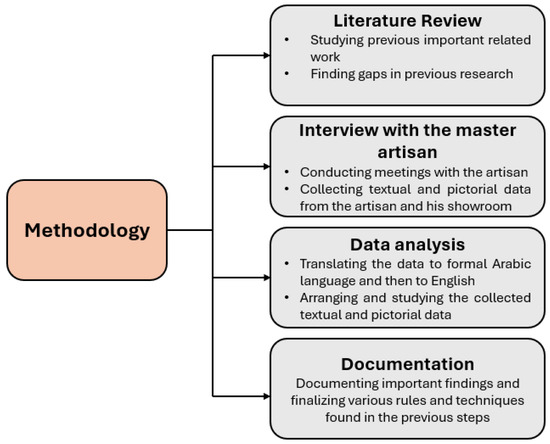

This section discusses the research method that was adopted for this study. It covers the whole outline of the research design and each step of the research flow. The section also discusses the semi-structured interview section that was employed for primary data collection. Figure 4 shows the stages of this research in detail.

Figure 4.

Stages of the research.

3.1. Literature Review

The first stage of the research involved a literature review, which is a review on multiple written articles that display a complete understanding of the existing state of knowledge and related studies with various related topics. The review focused on Syrian, Damascene, and Aleppo art, including the history of Syria and the art during the Ottoman and Umayyad periods. The secondary data and the knowledge gained from the literature review were utilized in a semi-structured interview to obtain information from the selected master artisan.

3.2. Data Collection and Interviews

The second stage of research concerns the collection of primary data for the research. These include face-to-face interviews and photographic documentation. The interview was conducted with a famous Syrian master artisan who inherited this art and has been involved in the industry since a young age. The artisan’s name is Abdulraouf bin Abdulqader Baydoun and he was born in the city of Idlib in Syria. The selected master artisan has a wide experience of over 40 years and became the main reliable resource for this research. Table 2 shows the details of the selected artisan. He is among the oldest generation of Ajami artisans who are highly recognized for their brilliant artistic talent. Nowadays, he is also one of the most skillful artisans in Syria. He is highly recognized as a distinguished Ajami artisan who has a long and valuable expertise of almost forty years. His achievements can be recognized in various significant public and private constructions which are sponsored by the Syrian government. He is also involved in many projects under the Arab Cultural Centre, such as building up the Ajami workshop in the Military Housing Establishment and ornamenting the Damascus International Airport and VIP lounges. The semi structured interview was chosen for this study because the questions were set to obtain information from the artisan. A huge amount of data and information was obtained through the discussion with the artisan, in the form of pictorial and textual data; the pictorial data were especially obtained during the interview in his workshops and a field visit. During this process of collecting textual information from the experienced professional artisan, the researcher also made a photographic documentation that is related to Ajami art production. This includes a large set of Ajami products (for example, doors, ceilings, furniture, windows, and walls) with their different ornamental designs. Other photos of Ajami raw material and samples of artistic and antique Ajami masterpieces have also been documented. All of these are illustrated as the primary data collection for this research. The Syrian artisan showed many samples of Ajami work in his workshop and gallery; these helped the researcher to comprehend the art based on the artisan’s explanation of the details and secrets of Ajami art techniques.

Table 2.

Selected master artisan information.

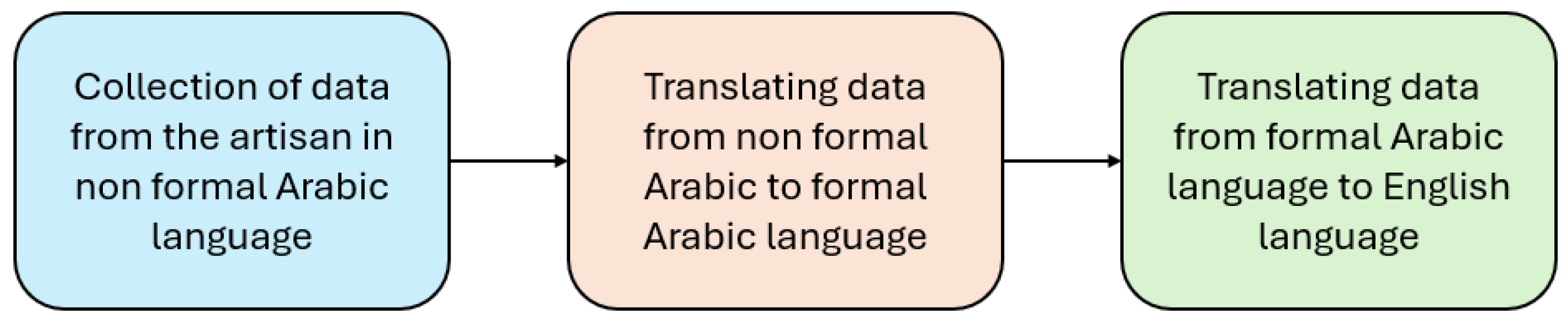

3.3. Data Analysis

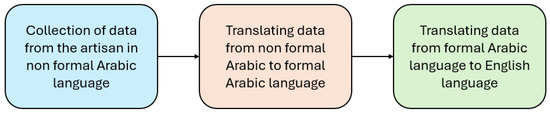

The third stage concerns the analysis of textual and pictorial data obtained from the semi-structured interview. The process of data analysis involved translation and editing transcriptions of the artisan’s captions, responses, explanations, and opinions. The master artisan is Syrian and only spoke informal Arabic language in a different slang. The artisan does not speak English in his daily life, and even formal Arabic language is hard for him. This is why the responses were first translated to formal Arabic and then to English. This was followed by analysis of the textual and pictorial data that were obtained from the field observation during visits to the artisan’s workshop and gallery. Figure 5 shows the steps involved in data analysis.

Figure 5.

Data analysis steps.

3.4. Data Documentation

The fourth stage of the research involved documentation of the overall results and findings of the study. After the stage of evaluating and interpreting, the researcher came up with the most important steps in Ajami art, based on the findings from the observation of practical works of artisans during the semi-structured interview.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results and findings based on the data collection of this study through semi-structured interviews with a master artisan and field observations. The selected artisan was requested to deliver his authentications and opinions on the traditional approach of Ajami methods and techniques. A set of questions in the interview schedule was utilized to aid him in providing his opinions. Based on the research questions, this section displays thoughtful discussions with reference to the interview questions. The production of Ajami involves several stages and steps, to produce a complete and appealing Ajami product as handmade art. Each stage has several steps that need to be followed one by one without omitting any step, as explained in the following paragraphs.

4.1. Materials and Techniques of Ajami Production

4.1.1. Preservative Materials

Bulleted wood conservation can be achieved by using two materials, shellac flakes and al-kalphona (قلفونة), which is a liquid material (from turpentine oil) that can be solidified by direct exposure to air. This resin material comes from the plants and looks like small grains. Al-kalphona is used as resin material but with the name colophony and different usage. It is used in a combination with linseed oil to create the so-called aloe that is a kind of orange glaze. Turpentine is an oily liquid with a strong smell and is used to decrease the painting thickness. Turpentine can also be used to clean the brushes of the colorful paints. The liquid varnish and lacquer are considered as a clear layer that is used as protection for the surface of the painting.

4.1.2. Preparation of Colors

The colours used in Ajami art painting are divided into three types, which are the basic colour set, that includes the blue, green, and red; the secondary colours, that are a variety of mixed colours; and the transparent ones, that can be applied on another colour and include a normal basic colour or on the dried silver and golden color. There are many methods of making color, depending on its raw material and its oil or water base. Mostly, the color pigments are extracted from the natural pigments and are made by complicated methods. The selected artisan pointed out that there is a possibility that modern methods and ingredients could replace the old, natural painting materials; these could include acrylic, gouache, and cellulose paintings, in addition to the usage of chemical and earthy pigments and metal acid. This can in fact help the current generation to continue making Ajami paintings.

The artisan mentioned that the artisan produces the colors and combines them together. There are different ways of making colors. The first way is mixing the pigments with lime. The second way is to form a foamy material made from the pigments mixed with dioxides. The latter method is called Al-kanbi, which is more popular; it is named after the person who invented it. For example, titanium can be mixed with vinegar, metal dioxides, Arabic glue, and egg whites with the aim of obtaining accurate and lighter degrees of the colors. The method of producing the color comes from metal dioxides; for instance, for a red color, salty water is added to iron filings and left for many days before being exposed to sunlight until the rust starts to pile up on it. The rust is mixed with katyrah (كتيرة) and egg whites. The artist mixes the produced mixture with flax oil. As for the pigments, the oxide is mixed with extended vinegar in a water base. After that, Al-katyrah (كتيرة) and Arabic glue are mixed to produce strong painting colors, especially the basic ones (including the black color). The black color is produced in the same way by using hubab powder (هباب) which is extracted from burned and grained bones or from burning the cork wood and grains then mixing it with katyrah (كتيرة) and egg whites or flax oil to obtain the natural black color.

The golden color can be made by using a golden lamina of layers, tin, and copper paper (metallic powder). There are also five different transparent colors used for Ajami art painting, such as natural resin, varnish, cement, blue pigment, white lead, carmine, indigo, and lead sulphate. The titanium oxide is also used to extend the painting’s sustainability. This material helps make the colors lighter in monochrome. Al’hra (أهرة), which is the yellow Sina soil, is also used to mix these oil colors with some acrylic colors. The artisan also mentioned that Ajami pigments are derived from main colors like pure blue, green, and red, with the aim of showing the oneness of Allah, which reflects Islamic belief. They are extracted from nature and mixed with pure natural components without adding chemical or industrial materials. In other words, the colors used in Ajami are 100% natural products. The artisan prepares many layers of golden papers with a cup of Arabic glue. He also adds the egg white that is mixed with alshabbeh (شبة). Gold leaves should be melted with Arabic glue. After placing the gold leaf on a plate of glass or ceramic, it should be rubbed by hand. A little water is added with continuous rubbing until the gold paper is dissolved, after which the mixture is left for at least six hours until the gold separates from the water and the color is ready to use. The same method is used to prepare the silver powder that is used for painting floral ornaments. The artisan explained further the methods of applying the golden colors on wood. The surface of the paper on the wood is painted with cooked corn flour and left until dry. After this, the surface is painted with egg whites. Gold is added on the same surface. After this, the artisan treats it with a material called al-kalphona (القلفونة) dissolved in pure ethyl alcohol. Al-kalphona is a liquid material which is converted into a solid by exposing it to the air. This material is extracted from the plants and looks like small grains. Finally, he paints the golden surface after polishing the golden paper using an agat stone (العقيق). Table 3 shows the detailed discussion of types of materials used in Ajami.

Table 3.

Categories and types of materials used in Ajami.

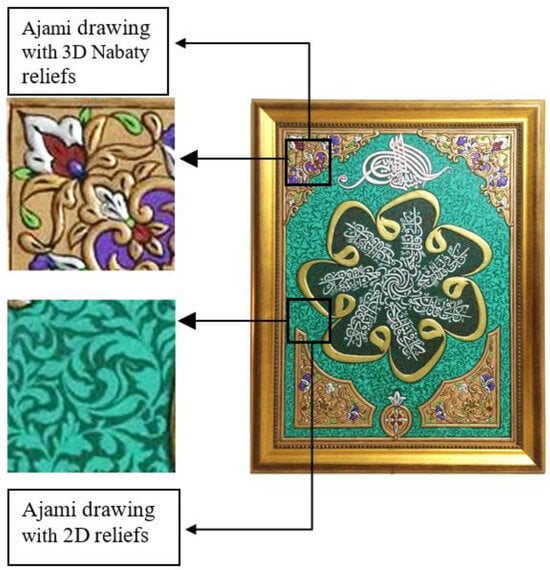

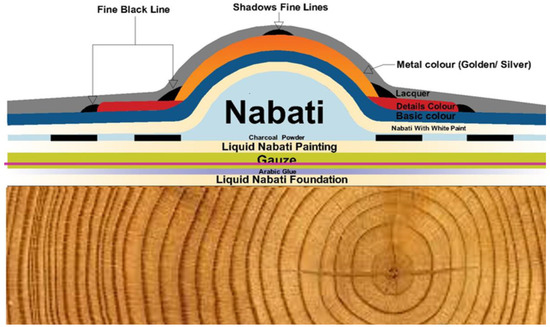

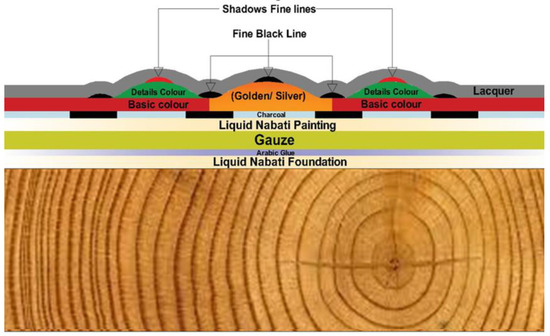

4.1.3. Techniques Used in Ajami Art

Ajami art consists of many layers, which represent the 2D and 3D forms of this handmade art, as shown in Figure 6. Firstly, a layer of liquid Nabaty is added by painting on the wood with the liquid nabaty. This is performed to polish and smoothen the prepared wooden surface. During the second stage, the drawn design is transferred from the tracing paper to the prepared wooden surface. This adds a new layer of charcoal powder on the wood to provide the design outline of the painting (Baydoun and Kamarudin 2017). The raised material Nabaty is added to fill up the charcoal outlines and is left until it dries up. A white paint mixed with Nabaty is added as the next layer; it covers the raised dried Nabaty for cleaning and support purposes. The next step involves applying the layer of basic colors to clarify the relief background; later, a new layer consisting of metallic pigments such as silver and gold is added. These metallic pigments distinguish the flowers and the leaves of the design rather than leaving it as mere ordinarily colored floral shape. The silver and gold layers sometimes are followed by a layer of missione for the gold colors; this is a kind of plaster and is used in the form of paper and not in the form of powder.

Figure 6.

2D and 3D appearance of handmade Ajami art.

The next layer is the color detail layer that enhances the aesthetic value and creates balance in the colors of the background. A finishing fine black line is drawn on the borders of the raised areas to determine the final shape of the design, supported by colorful shadowed fine lines on the painting. The colors of the shadow are chosen based on the overall colors of the painting. This line is used to create the final balance of colors. A dark orange color is added to the entire painting as a contour line to create contrast and balance to the color’s value (Baydoun et al. 2017). The final layer of lacquer is applied to protect and preserve the colors, in addition to making it shiny. Table 4 shows the 2D and 3D techniques and steps for Ajami art. Figure 7 illustrates the section of a 3D painting, while Figure 8 shows the section of a 2D painting. These figures illustrate the work of the chosen artisan, showing the two parts of the drawing showing 2D and 3D techniques.

Table 4.

Ajami layers of 2D and 3D materials and techniques.

Figure 7.

3D Ajami section.

Figure 8.

2D Ajami section.

The techniques of colouring and preservation in Ajami art can be differentiated from all the traditional handmade arts from other civilisations. Ajami art painting is a combination of natural materials. The value of an Ajami art piece increases over the years. The analysis of any piece of Ajami art can determine its age and the date it was created. Furthermore, the use of a wooden panel as a surface can support the task of figuring out the age of Ajami art paintings.

Mostly, the material used for the Ajami surface is well-dried and manufactured wooden panels that should be selected by agriculture experts to ensure longer sustainability and a higher value. This is because the wood quality varies due to the weather, temperature, humidity degree, and many other conditions of the region where the wood is planted. The materials should be collected during specific months of the year, in the seasonal regions.

The raised material used for making the high relief in Ajami painting is made by mixing many natural raw materials for a higher hardness. Nowadays, this Nabaty can be created from some chemical and local materials but with a more professionally measured quantity of water, to fit the degree of the humidity of the region where the Ajami art painting is created. In other words, there is no secret in Nabaty making itself, but the secret is hidden in the challenge of making a higher hardness for the raised material and improving its sustainability.

Ajami as an Islamic art has special rules for decoration drawing and selection. It has both the floral and geometrical ornaments, with more focus on the floral one as it is easier and more flexible in application and function. There is also another supporter to Ajami art painting, which is the calligraphy. This main element might be a verse from The Holy Quran, a poem, or any sentence that contains many secrets and hidden meanings related to the artisan or the house owners (Baydoun et al. 2023). Quranic calligraphy usually is placed in the upper part of the wall or on its cornice. That is because of its sacred value in the Islamic perspective.

Any painting in Ajami art is a piece of art that displays a combination of a sense of colours and a sense of emotions. It is the artist’s reference, where a viewer can see his identity, thoughts, and his mood as well. Like an abstract piece of art, Ajami painting is the story of the life or history of a nation in its prosperity and flourishing. It is a perfect artistic production of the several civilizations that went through Syria during the ancient time. Fundamentally, the art of the Ajami people reflects the intricate history of Syria and the meeting point of numerous civilizations that have shaped the area over thousands of years. Syria has been a crossroads of cultures, faiths, and ideologies since the time of the ancient Mesopotamian and Phoenician civilizations as well as the Greek, Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic empires. Each of these civilizations left a lasting artistic legacy in Syria and had a significant impact on the evolution of Ajami art. One important component of Ajami art was the Islamic calligraphy tradition, which emphasised the written word as a sacred form of expression. This gave Ajami art a spiritual meaning and symbolism (Renima et al. 2016).

Furthermore, the rich creative traditions of the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries, where textiles, ceramics, and architecture have long been embellished with ornate designs and motifs, might be linked to the vivid colors and intricate patterns found in Ajami art. Ajami painting, which captures the tenacity of Syria’s culture, the spirit of its people, and the beauty of its landscapes, essentially functions as a visual narrative of the country’s history. In addition to the artist’s personal expression, every brushstroke and color selection captures the collective memory of a country formed by centuries of artistic creativity and cultural interchange.

Skilfulness in terms of creating Ajami art can be summarized as the ability of creating an Ajami painting in a similar shape, value, and age as that of an old piece of Ajami painting. The skilful artisan of Ajami art is the one who can achieve and monitor all the steps and stages of Ajami art and has the long-term experience in Ajami art material-making.

4.2. Stages in Ajami Production

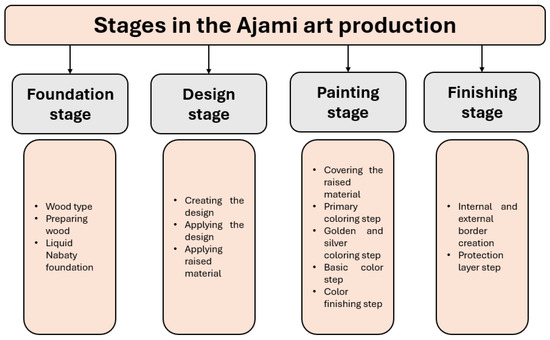

The production of Ajami involves several stages and steps, to produce a complete and finished product of Ajami as handmade art. Each stage has several steps that need to be followed one by one, without omitting any step, as explained in the following sections. Figure 9 shows the various stages in Ajami art production.

Figure 9.

Stages in Ajami art production.

4.2.1. Foundation Stage

The foundation stage consists of three main steps. This stage covers the wood preparation for Ajami art paneling with the raised material technique. This includes the woodwork step, wood preparation, and Nabaty foundation step. All these steps are the primer stage to produce an handmade Ajami art product.

- a.

- Wood Type

Choosing the wood for the artwork is difficult because the wood must be free of any cracks and damage for the art to last for up to a hundred years. Treated wood is used for this purpose. Wood that has undergone the treating process for several years is purchased. The treated wood takes a long time to dry up even after it has been cut to stop its growing process. The most preferred type of wood for Ajami artwork use is wooden panels that have been treated for a long time. Some artists use industrial wood like MDF or other types of manufactured woods because these types of wood are less exposed to the danger of getting cracks or getting damaged in the future, as this would reduce the value of the painting.

- b.

- Preparing Wood

After choosing the most suitable type of wood, one that is robust and not prone to damage easily (for example, poplar, walnut, etc.), the wood is cut into different shapes and sizes according to what it will be used for when complete (wall, ceiling, bookshelf, door, window, furniture, painting, etc.). After this, the chosen wood is smoothed over with sandpaper.

- c.

- Liquid Nabaty foundation

This step starts by preparing the liquid nabaty, which is then applied along with Arabic glue onto the wooden surface to support and ease the process of applying the charcoal powder and the raised material at a later stage. For one panel of Ajami art, it requires one cup of gypsum, five cups of water, two cups of stopping powder, one cup of glue, one-tenth of a cup of katyrah (الكثيرة), and one-tenth of a cup of glue.

First, water should be mixed with the gypsum and stirred until the gypsum has liquefied, which takes a minimum of half an hour to accomplish. The rest of the materials are then added to the mixture and blended well. If the mixture is too thick, water can be added little by little. After the Nabaty is ready, it is applied onto the wood surface. By applying this flat later of nabaty, any holes and cracks in the wood are filled up.

4.2.2. The Outline Design Stage

Designing is the most difficult part of Ajami art, as this process involves creating new patterns in floral, geometric, and sometimes even pictorial figures. Then, the design is transferred onto the wood. Nabaty is applied to create the raised or 3D effect. The steps involved in design stages are as follows:

- a.

- Creating the Design

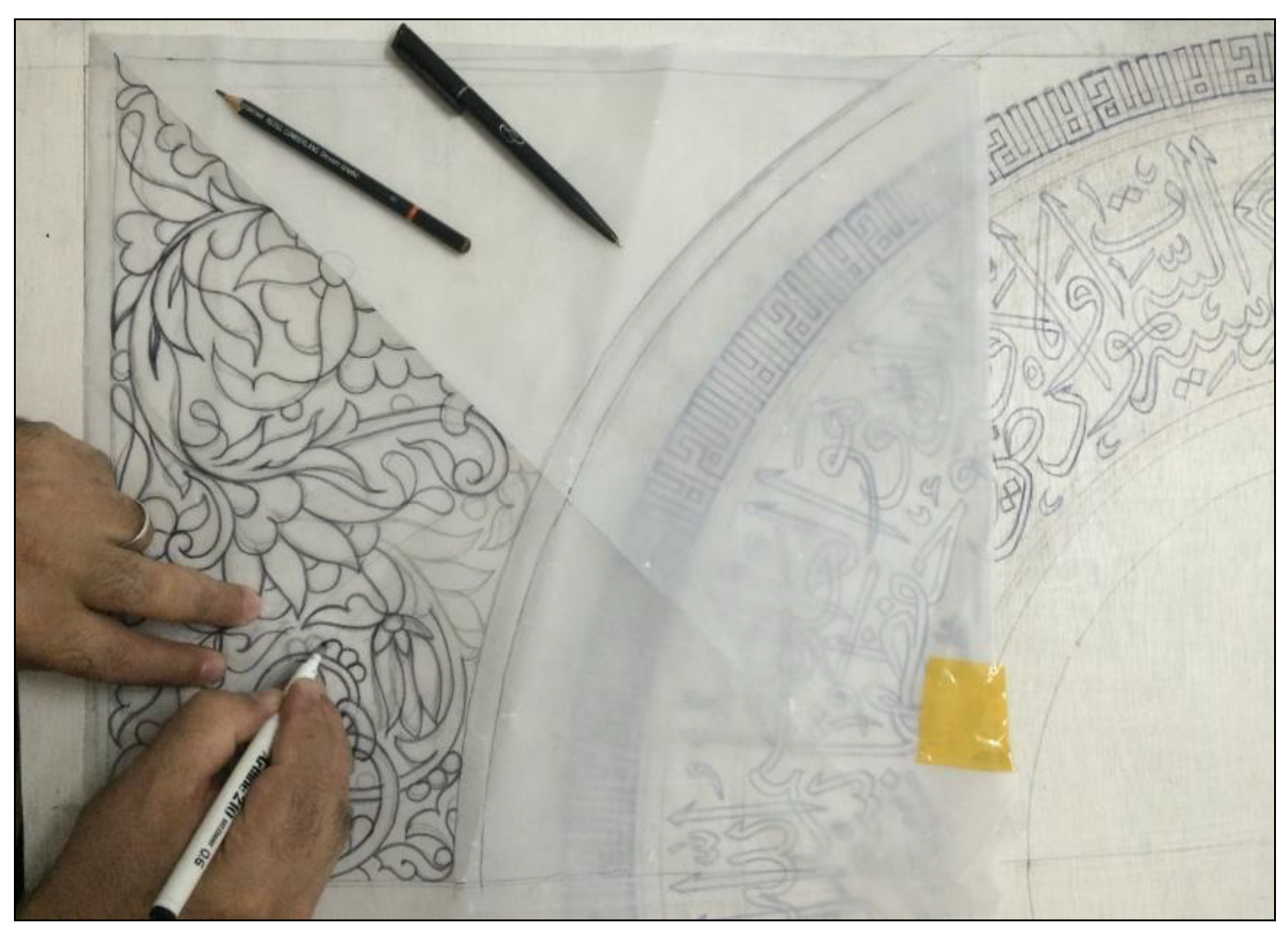

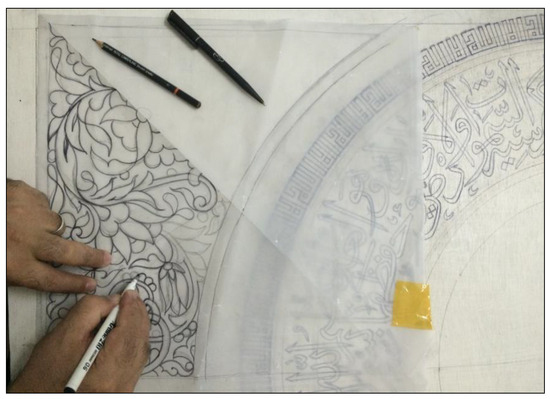

The design for Ajami painting should take into consideration the aim and what the art will eventually function as. This is related to the size and the shape of the chosen piece of wood. First, tracing paper should be cut in the same size as the wooden piece, then the outline of the geometric and floral patterns should be drawn on the tracing paper, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

The artisan drew the design on tracing paper.

It should be a symmetric design to ease the design creation process. This is achieved when the artist folds the tracing paper twice and draws the design on one side to be then repeated on the remaining three sides, to create an entire design that will fill the wood surface. Some designs can be supported by writing a verse, poetry, or anything, depending on the client’s request. However, the artisans have a strong preference for floral and geometric designs, influenced by Islamic religious beliefs. Also, it can be a framework of a view of nature, buildings, garden, or plate of fruit. All should be drawn on the piece of tracing paper with both detailed geometric and floral patterns, as illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

The pattern drawing step.

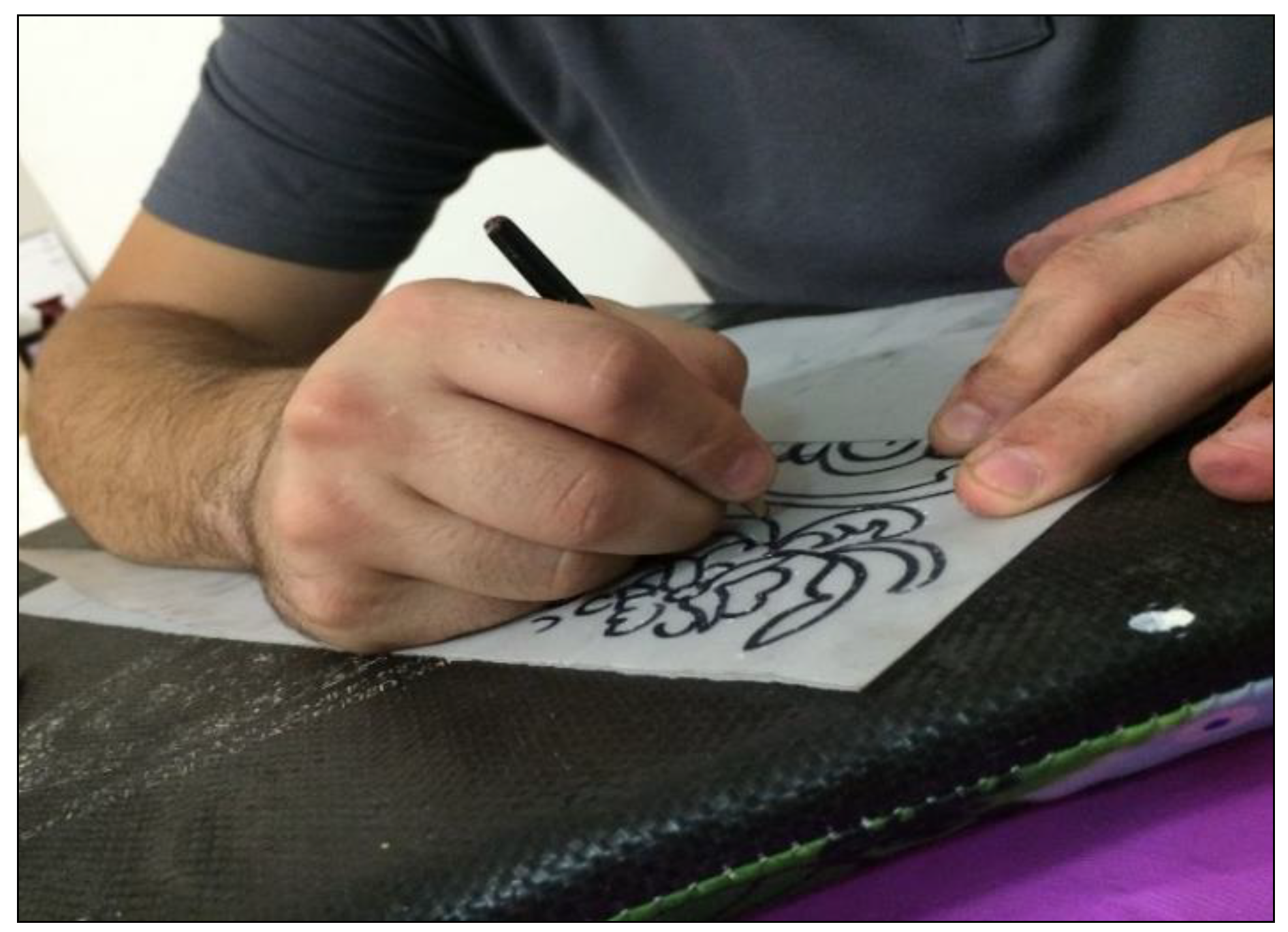

After the drawing of the design is complete, a pin attached to a stick can be used to press the design drawn on the tracing paper, using a foam board under the tracing paper. Then, the tracing paper is smoothed by sandpaper on the affected areas of the pin to open the holes in preparation for the next step, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Pin works on the halls.

- b.

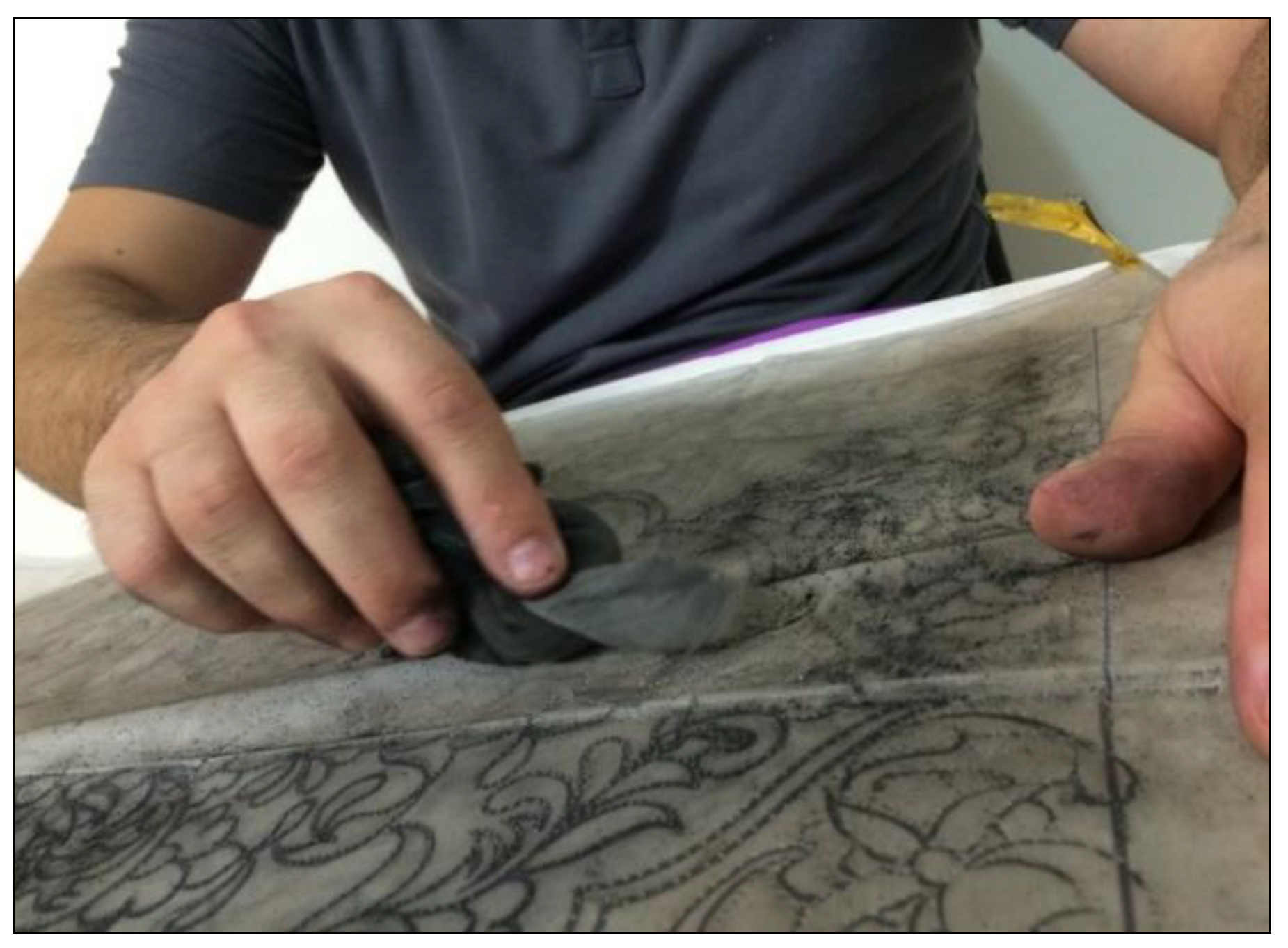

- Applying the Design

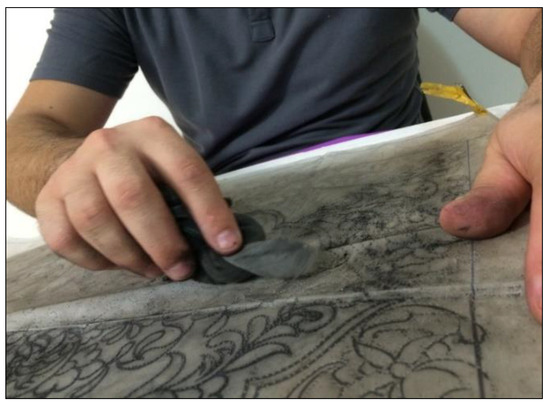

After finishing the process of pressing the design that was previously drawn on the tracing paper, a fabric bag full of charcoal powder should be rubbed on the tracing paper that has already been fixed on the wooden piece with a plaster. After rubbing the charcoal bag on the pressed tracing paper, a dotted outline appears on the wooden piece, and this can be modified by pencil to go over the unclear lines, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

The traditional printing step using charcoal powder.

- c.

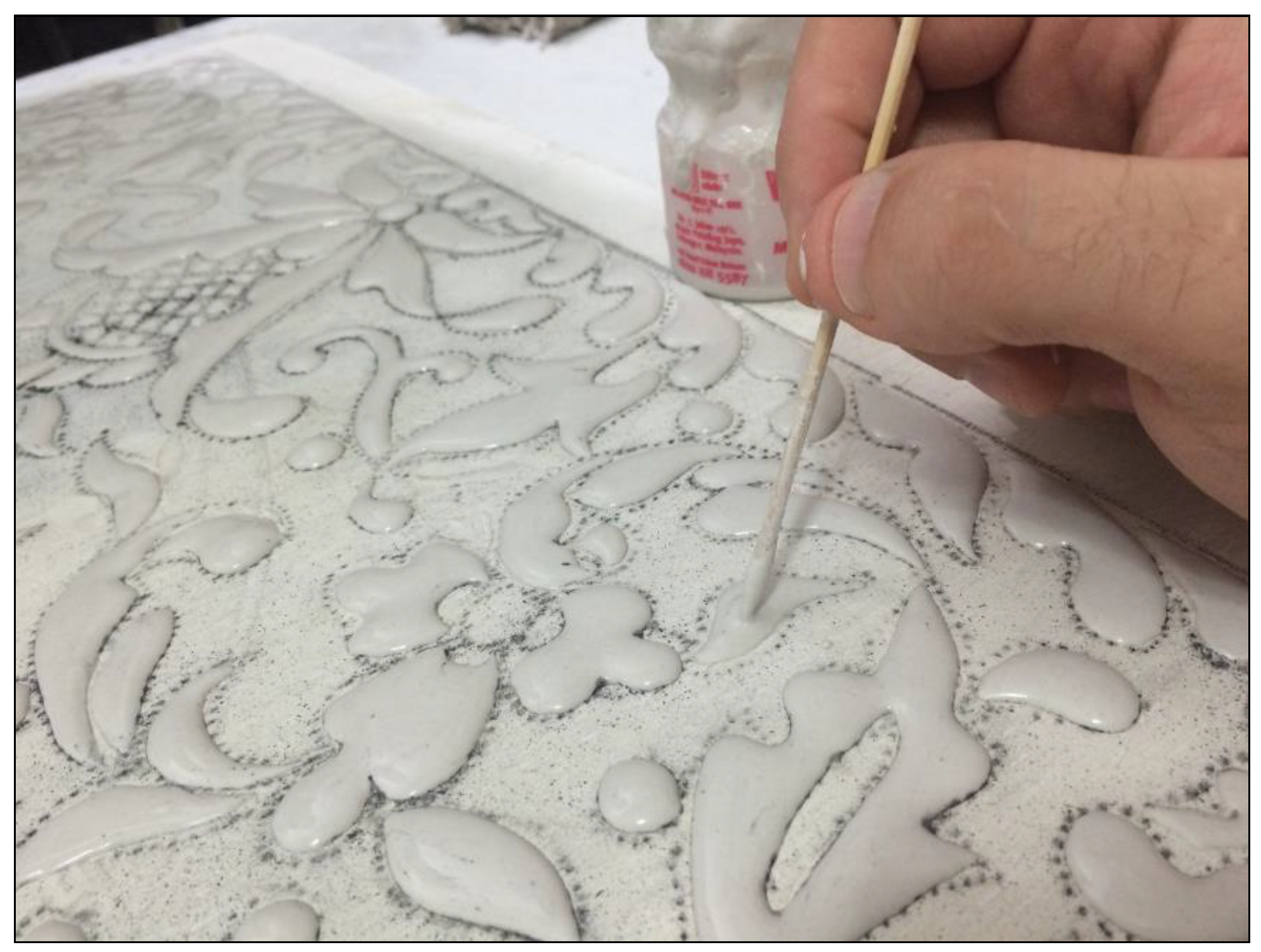

- Applying the Raised Material

To create one panel of Ajami art, it requires a cup of gypsum, three cups of water, three cups of the stopping powder, one cup of glue, one-tenth of a cup of al-katyrah (الكثيرة), and one-tenth of a cup of Arabic cooked glue. The liquid material Nabaty should be prepared and kept in a small cup with a special brush and stick. The stick is dipped into the liquid and dropped onto the charcoal-outlined design and pulled to fill in the design, as shown in Figure 14. The brush is to refine the edges of the applied raised material. After Nabaty is applied on the entire design, it should be left in a dry atmosphere. The drying process takes 1 to 2 days, until the raised material becomes as solid as stone.

Figure 14.

Applying raised Nabaty material.

4.2.3. Painting Stages

Covering the raised materials, applying the primary colors, applying the golden and silver colors, applying the basic colors, and coloring the detailed areas are the steps involved in the painting stage of Ajami art. This stage is considered as the penultimate stage, which involves refining and coloring of the Ajami painting, including the raised and flat surfaces of the painting.

- a.

- Covering the Raised Material

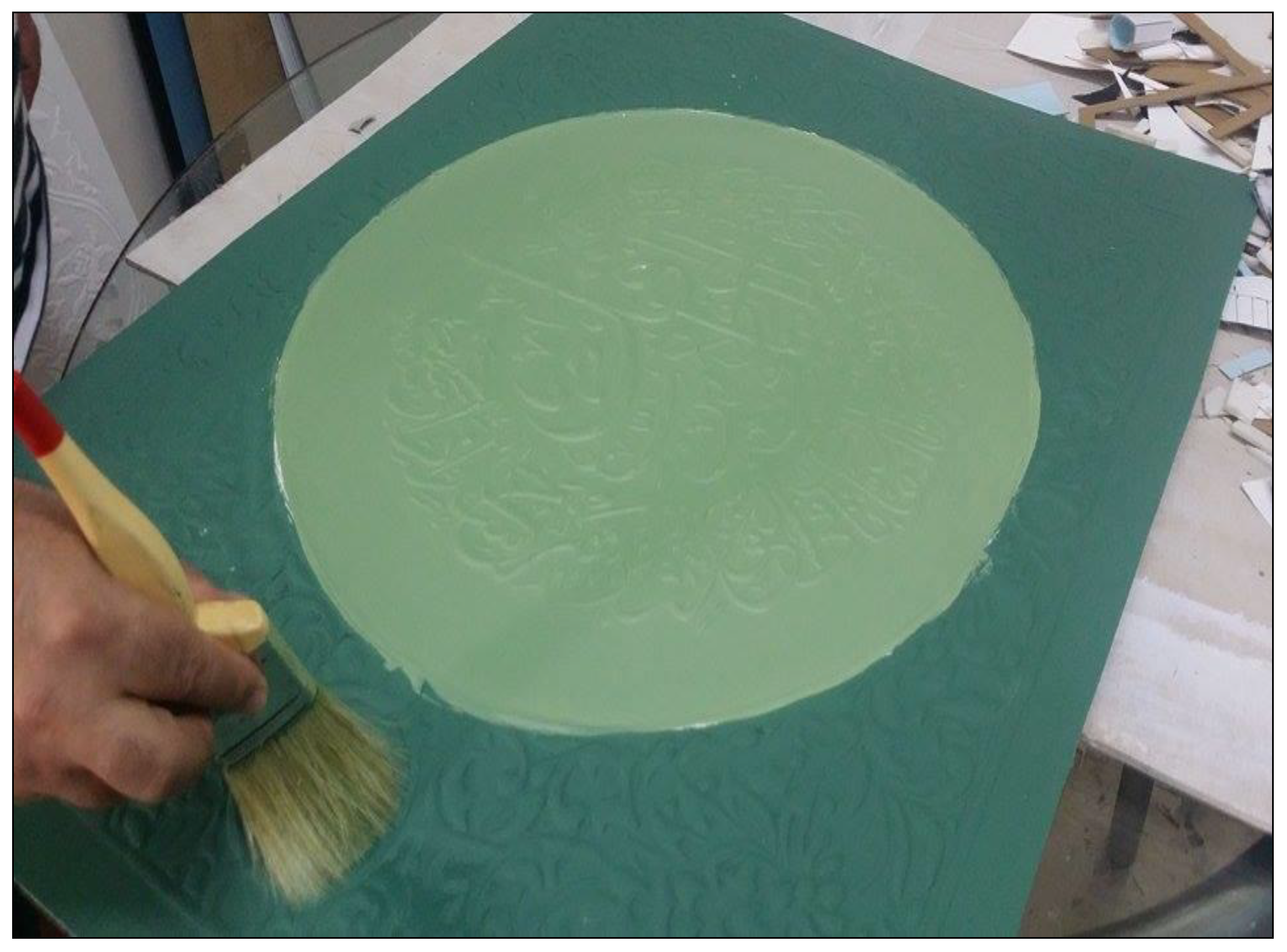

After the Nabaty is completely dried, it should be smoothed and refined carefully using different types of sandpapers. Starting from the basic smooth sandpaper grade to the very smooth one, everything should be performed step by step. The product should be wiped by a fabric piece to clean all the dust after smoothing. Then, the Nabaty liquid material should be applied on that product to cover the entire surface. Finally, it should be covered with a layer of linseed oil followed by a layer of white paint, as shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Applying the liquid white paint.

- b.

- Primary Colors Step

Three layers of the white paint are applied with a drying period between each application. After application of the first white layer, the painting should be left for three hours, after which the second layer is applied and then kept for another 24 h. Finally, it is smoothed over with sandpaper to ensure there are no cracks or holes.

- c.

- Golden and Silver Color Step

To apply the gold papers, the artists need missione glue, which is a water-based gilding glue with a white colour. It is used to affix the gold and silver leaf on the required surfaces using only hands and a two-inch dry brush. Then, the golden or silver paper is placed on the surface of the painting, giving the chosen areas golden and silver colours, as illustrated in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Applying the golden color on the painting.

- d.

- Basic Colors Step

This stage involves filling the main colors that cover large areas of the drawing. Generally, red, blue, and green are often used for these spaces. The surface is painted by starting from large areas and gradually focusing to smaller areas. Figure 17 shows the application of the basic green colour. After the surface has been painted with the main background colors, it is left to dry completely. The drying process can take from 6 hours up to a full day, depending on the climate the artwork is made in. Finally, colour is applied to the flowers, plants veins, and geometric lines within the painting.

Figure 17.

Basic colors applied on paintings.

- e.

- Color Finishing Step

After coloring all the flowers in different colors (with all the details) and applying the gold and silver leaf in their designated areas, the design is outlined with either black or white, depending on the background colors. The basic color often is black. White color is used to outline the red, yellow, and pink floral designs, while the rest of the colors are contoured by black, especially the gold and silver. As for the contour methods, a 3D effect is created by using the same colour with a darker grade. Later, a frame is added to the painting, and that is the final step. The painting is finished when all the colors have been applied perfectly.

4.2.4. Finishing Stage

To finalize any product before presenting it as finished, it needs to go through the finishing stage. The internal and external borders and protecting layers are the two main steps required to finish any Ajami product. This section includes the finishing stages of the artwork and serves to set and finalize the painting and its colors.

- a.

- Internal and External Borders

When the layout is specified, another process starts: it sets the basic lines on the painting edges. Free-hand drawings are used to add simple plant and tendril decorations, which are applied using a colour that is lighter than the background. This is performed to fill in empty spaces that are bare of design elements, as shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Drawing black lines as borders.

- b.

- Preservation Stage

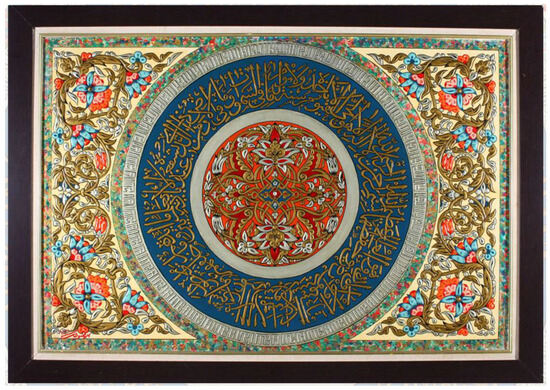

After going through all the steps mentioned previously, the artwork is finished. The last remaining step is to protect it with lacquer using a five-inch brush. The lacquer is applied slowly and carefully to avoid mixing the colors together on the paintings. The drying time for the lacquer is around 1 to 2 days, depending on the climate. After completely drying, the product will be ready to be applied on the wooden frame, to become an Ajami panel. Figure 19 shows a final complete product of Ajami art. This magnificent picture is taken from the selected artisan’s art collection.

Figure 19.

Finished Ajami artwork.

5. Discussion

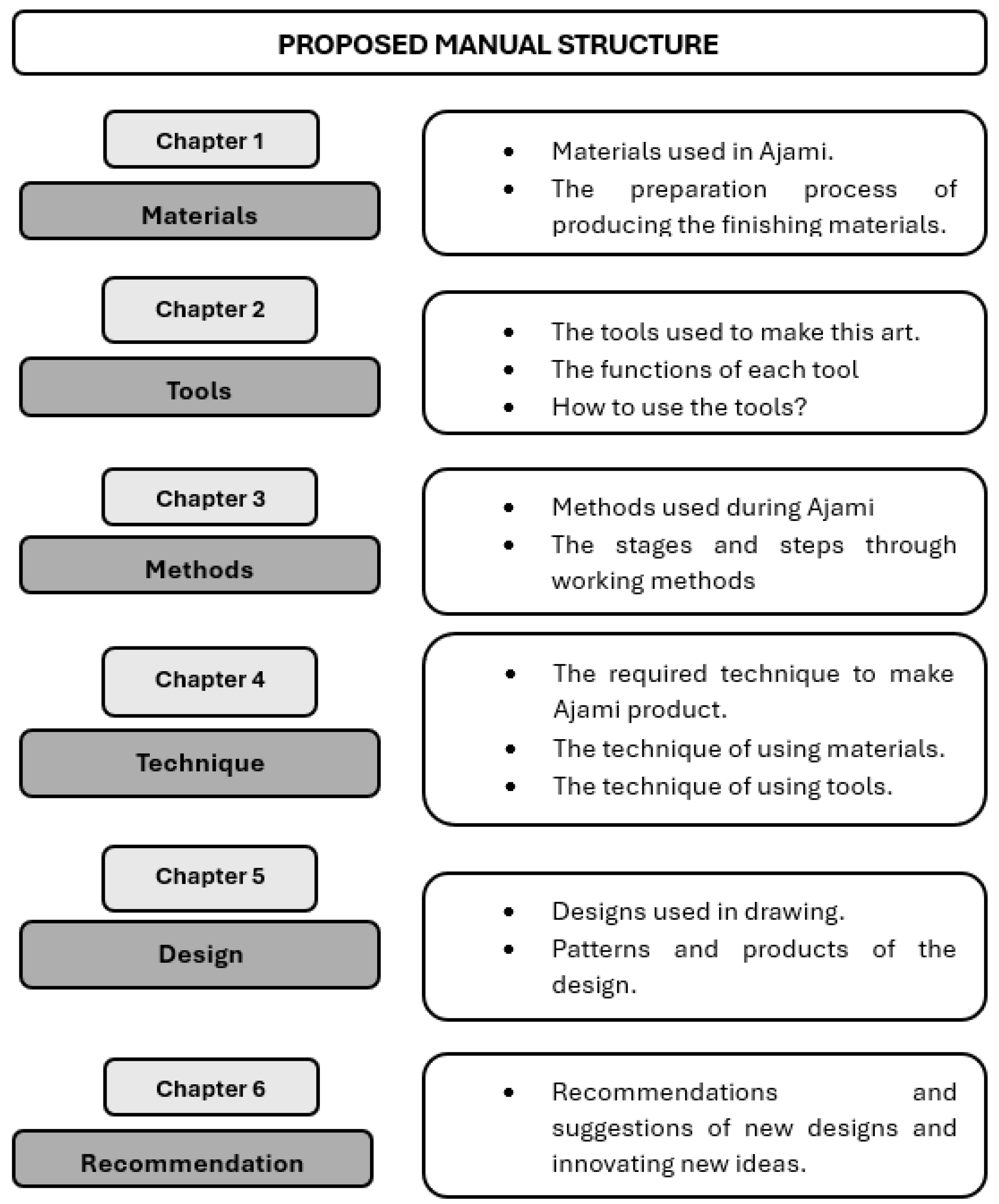

Ajami art, according to the master artisan’s experience, is art that is totally handmade and requires professional people to help the master artisan to complete the project. Ajami art needs skillful workers from a variety of majors, including psychology, architecture, and mathematics. Psychologists can decode why heritage art loses interest, then design engaging experiences like workshops to make it relevant and emotionally connect with today’s audience. Moreover, Ajami art requires patience and a high level of concentration to focus on the design creation and color arrangement. The new generation is less attached to their roots and heritage, and with the emergence of technology, they have become more focused on handheld devices and the Internet (DeSilvey and Harrison 2020; Shahab 2021). The master artisan has expressed concern that Ajami art is in danger of being forgotten with the disappearance of the master artisans who have stopped teaching it. The master artisan suggested that Ajami art needs a simple effort from the government to advertise the art and teach its history to not only students but audiences from every field, as well as associating with schools to teach this prominent art. He also suggested holding Ajami art competitions and giving rewards and certificates to the winners. This could make remarkable progress in Ajami art development inside and outside Syria. Since producing Ajami art is high cost and time-consuming, the government can provide support by offering high wages for people who work on this art. This research proposes the creation of a comprehensive manual outlining the step-by-step process of Ajami art creation. This manual would serve as a foundational resource for aspiring Ajami artists seeking to develop their skills and potentially pursue professional practice.

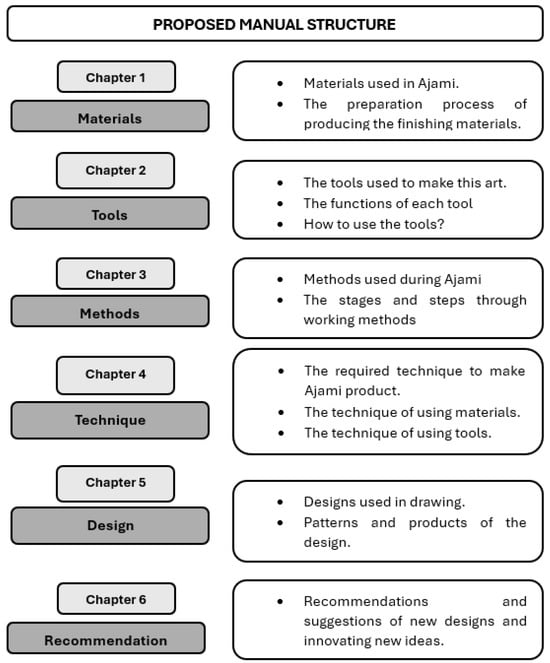

The proposed Ajami art creation manual, outlined in Figure 20, will be structured into six comprehensive chapters. The first chapter emphasizes the importance of material selection, categorized into liquids, solids, and powders, and detailing their mixing, preparation, and specific application points within the artwork. Chapter 2 focuses on essential tools, providing instructions on their proper use and maintenance. Chapter 3 delves into the step-by-step process, outlining the sequential application of materials and the tools employed at each stage. Chapter 4 explores the various techniques used in different phases, encompassing material manipulation, tool application, and overall design execution. Chapter 5 analyzes design interpretation, discussing the symbolic meaning and variations within Ajami designs, how they reflect the artist’s intent, and their typical placement within the art form. Finally, Chapter 6 explores new design possibilities, recommends optimal design choices, and proposes innovative ways to integrate Ajami art into contemporary settings.

Figure 20.

Structure of the proposed manual.

6. Conclusions

This study delves into the under-documented realm of traditional Ajami production methods, drawing insights from the meticulous work of a Syrian master artisan. By meticulously documenting the distinct phases of Ajami creation—foundation preparation, design application, painting techniques, and finishing treatments—the research aims to contribute significantly to the preservation of this intricate Islamic art form. Moving beyond mere description, the study offers a comprehensive record of the entire traditional Ajami production process, encompassing the selection of specific materials (e.g., pigments and plaster compositions) to the final finishing techniques employed. This detailed cataloging not only ensures the continued availability of these traditional materials but also promotes the authenticity of future Ajami creations. These findings constitute a pivotal step towards safeguarding the survival of Ajami artistry for generations to come. Furthermore, the research proposes the development of a step-by-step manual outlining the Ajami art creation process. This manual would serve as an invaluable resource for aspiring Ajami artists, empowering them to develop their skills and potentially pursue professional careers in the field of cultural heritage preservation. The documented methodology serves not only as a foundation for further research on Ajami art and related decorative techniques but also as a springboard for educational initiatives and cultural preservation efforts. Continued exploration of this exquisite art form, inspired by the wisdom of master artisans, holds immense potential for fostering cultural revitalization and artistic innovation within the broader field of Islamic art history.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.B.; methodology, Z.B.; validation, Z.B., T.P.N.T.S. and F.M.; formal analysis, Z.B.; investigation, Z.B.; resources, Z.B.; data curation, Z.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.B.; writing—review and editing, Z.B.; visualization, Z.B., T.P.N.T.S. and F.M.; supervision, T.P.N.T.S. and F.M.; project administration, T.P.N.T.S. and F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the sensitivity of the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alafandi, Rami, and Asiah Abdul Rahim. 2016. The Lost Treasure of the Polychrome Wooden (‘ajami) Interior of Ghazalyeh House, Aleppo, Syria. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 222: 596–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alafandi, Rami, Kuala Lumpur, and Kuala Lumpur. 2016. The Aleppine Ottoman ‘Ajami Rooms, Destruction and Reconstruction. Journal of Education and Social Sciences 4: 169–80. [Google Scholar]

- Baydoun, Ziad, and Zumahiran Kamarudin. 2017. Ajami As Painted Wooden Wall Paneling for Living Spaces of Interior Design From Two Master Artisans Perspective. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/57729003/PIBEC_2017.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Baydoun, Ziad, and Zumahiran Kamarudin. 2018. Innovation of Techniques in ‘Ajami as Painted Wooden Wall Panelling for Living Spaces of Syrian Houses. pp. 1–9. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/57729003/PIBEC_2017.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Baydoun, Ziad, Nawal Abdulrahman Alghamdi, and Zumahiran Kamarudin. 2023. The Islamic art and design elements applied in the Islamic city, a case study of putrajaya islamic city. Planning Malaysia 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydoun, Ziad, Zumahiran Kamarudin, and Musaab Sami Al-Obeidy. 2017. Techniques of painted wood paneling in the ajami’s Art and craft in Syrian houses. International Journal of Advanced Multidisciplinary Research 4: 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, Prasanta K., Rafal Kaminski, Ramona Bella, Hang Su, Saumi Mathews, Taha M. Ahooyi, Chen Chen, Pietro Mancuso, Rahsan Sariyer, Pasquale Ferrante, and et al. 2019. Sequential LASER ART and CRISPR Treatments Eliminate HIV-1 in a Subset of Infected Humanized Mice. Nature Communications 10: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirarslan, Deniz. 2017. Analysis of Interior Space of a Room in a Traditional Turkish House with Respect to Construction Material and Application Techniques: Safranbolu Region House. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science 22: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSilvey, Caitlin, and Rodney Harrison. 2020. Anticipating Loss: Rethinking Endangerment in Heritage Futures. International Journal of Heritage Studies 26: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, Christian. 2006. Das Aleppozimmer: Strukturen und Dekorelemente der Malerein im Aleppozimmer des Museums für Islamische Kunst in Berlin. Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Fair, Lauren, Beth Edelstein, and Adriana Rizzo. 2010. Painting Techniques of Ottoman Interiors: Reconstructing decorative panels from a Damascus Room at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/41492810/Painting_Techniques_of_Ottoman_Interiors_reconstructing_decorative_panels_from_a_Damascus_Room_at_the_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Foss, Clive. 2017. Syria in Transition, AD 550–750: An Archaeological Approach. In Late Antiquity on the Eve of Islam. London: Routledge, pp. 171–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonnella, Julia, and Jens Kröger. 2008. Angels, Peonies, and Fabulous Creatures: The Aleppo Room in Berlin: International Symposium of the Museum Für Islamische Kunst-Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin, April 12–14, 2002. Berlin: Museum für Islamische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Great Lakes Publishing. n.d. Secret Ohio: The Damascus Room. Available online: https://www.ohiomagazine.com/travel/article/secret-ohio-the-damascus-room (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Hassanein, Hamada, and Jens Scheiner. 2019. The Early Muslim Conquest of Syria: An English Translation of al-Azdī’s Futūḥ al-Shām. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney, Ellen. 2018. Interpolated Spaces: The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s ‘Damascus Room’ Reinstalled. International Journal of Islamic Architecture 7: 305–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, Annie-Christine Daskalakis. 1997. A Room of “Splendor and Generosity” from Ottoman Damascus. Metropolitan Museum Journal 32: 111–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meis, Mareike. 2016. When Is a Conflict a Crisis? On the Aesthetics of the Syrian Civil War in a Social Media Context. Media, War & Conflict 10: 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Drfayrose, and Mahmoud Ibraheem. 2015. The Aesthetical Analysis of Mural Decorative Elements in the Great Mosque of Damascus. Journal of Applied Art and Science 2: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, Peder. 2005. Bayt Al-’Aqqad: The History and Restoration of a House in Old Damascus. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mravik, Petronella Kovács, Éva Galambos, Zsuzsanna Márton, Ivett Kisapáti, Julia Schultz, Attila Lajos Tóth, István Sajó, and Dániel Károly. 2019. A Polychrome Wooden Interior from Damascus: A Multi-Method Approach for the Identification of Manufacturing Techniques, Materials and Art Historical Background. In Heritage Wood: Investigation and Conservation of Art on Wood. Cham: Springer, pp. 123–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osadola, Samuel Osadola, Olukemi Olofinsao, and Iyabode Ajisafe. 2021. Fact or Mythology—Yoruba and Benin Historical Correlation. International Journal of Research Publications 87: 277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renima, Ahmed, Habib Tiliouine, and Richard J. Estes. 2016. The Islamic Golden Age: A Story of the Triumph of the Islamic Civilization. In The State of Social Progress of Islamic Societies. Cham: Springer, pp. 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharrahs, Anke. 2010. Insight into a sophisticated painting technique: Three polychrome wooden interiors from ottoman syria in german collections and field research in damascus. Studies in Conservation 55: 134–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharrahs, Anke. 2013. Damascene ʻAjami Rooms: Forgotten Jewels of Interior Design. London: Archetype Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Schwed, Jutta Maria. 2006. The berlin aleppo room: A view into a syrian interior from the ottoman empire. Studies in Conservation 51: 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Sofya. 2021. Crafting Displacement: Reconfigurations of Heritage among Syrian Artisans in Amman. Journal of Material Culture 26: 382–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevathan, Idries, and Lalitha Thiagarajah. 2010. The ottoman room at the islamic arts museum malaysia: A technical study of its methods and materials. Studies in Conservation 55: 120–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Delaware. 2018. Sarah Gowen and Stephanie Oman: Shangri La, Honolulu, Hawaii. Available online: https://www1.udel.edu/udaily/2011/jul/gowenoman072810.html (accessed on 22 January 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).