Abstract

The illustrated books of Kōriki Enkōan (1756–1831), a samurai and amateur illustrator from Owari domain, offer a unique window into the culture of spectacle and display that flourished in late Edo-period Japan. Included in his corpus are several manuscripts that document kaichō, public exhibitions of sacred icons and temple treasures hosted by Buddhist temples and other venues. While most studies of kaichō emphasize their popularity in the capital of Edo, this article focuses on Enkōan’s illustrated manuscript of an exhibition of the famous Seiryōji Shaka that was held in Nagoya in 1819. Situating the event and its visual documentation within the statue’s legendary history as a traveling icon, the study explores how Enkōan’s careful manipulation of text and image created an immersive reading experience that allowed its readers a kind of virtual access to the exhibition. Considering the author’s position within the contemporary social hierarchy, it also addresses the role that samurai values may have played in shaping the representation of kaichō and illuminates its intersections with urban spectacle and emerging exhibition practices in early modern Japan.

Keywords:

Japanese Buddhist art; text and image; illustration; Enkōan; kaichō; display culture; Edo period; Nagoya 1. Introduction

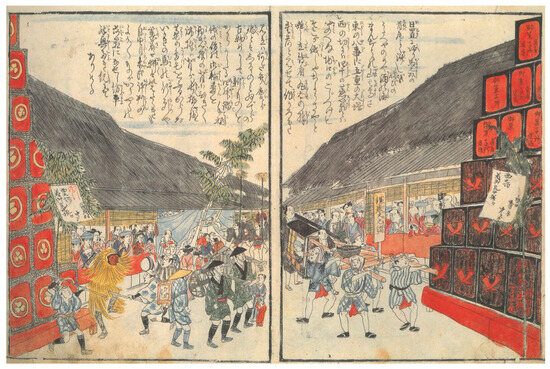

From 1772 to his death in 1831, a samurai of Owari 尾張 domain named Kōriki Tanenobu 高力種信 (1756–1831), better known by his pseudonym Enkōan 猿猴庵, produced more than one hundred small, illustrated books (ehon 絵本) that document a panoply of performances and public events in and around the city of Nagoya 名古屋. These visual records of local festivals, traveling sideshows, spectacles (misemono 見せ物), and exhibitions combined whimsical and amateurish drawings with extensive textual commentary to provide a first-person account of the culture of leisure and spectacle that flourished in Japan during the late Edo 江戸 period (1615–1868) (Figure 1). While the carnivalesque atmosphere portrayed in this work appears to reflect what has often been characterized as the increasingly secularized, commercial society of early modern Japan, much of Enkōan’s attention was unquestionably drawn to auspicious and religious subjects. This is most consistently seen in his frequent documentation of kaichō 開帳: public exhibitions of Buddhist icons and temple treasures held at local temples and shrines.

Figure 1.

Residents of Hioki Town 日置町 gather to watch street performances and dances following a festival. By Enkōan. 1818. Nagoya City Museum. Reproduced from (Nagoya City Museum 2012, pp. 31–32).

Kaichō (literally, “curtain openings”) were enormously popular events in the mid- to late-Edo period that often combined the display of sacred images with a broad array of peripheral attractions, from food vendors and souvenir hawkers to performances and displays of curiosities that spilled out beyond the borders of the temple precinct. They can generally be categorized into two types: those in which a temple displayed Buddhist icons and sacred objects already in its possession (igaichō 居開帳) or those that showcased icons brought from far-off temples in Kyoto and elsewhere (degaichō 出開帳). The majority of kaichō that Enkōan attended, as evinced by his illustrations and frequent references throughout his diary (Enkōan nikki 猿猴庵日記), were degaichō held at local Nagoya temples on route to and from the Edo capital. The artifacts displayed at these traveling exhibitions included not only objects of great antiquarian interest but also images whose fame derived from widely circulating legends that ascribed to them sacred powers and miraculous agency. Kaichō thus marked a significant point of intersection between religion and popular culture in the early modern period, and their study provides an opportunity to consider how religious images were viewed and displayed in Japan in a period that predated the advent of modern expositions and museological practice.

While important studies have discussed the institutional function of kaichō for lending temples (Ambros 2004; Hur 2009) or their history in relation to other display and performative cultures that developed in the Edo capital (Hiruma 1980; Markus 1985; Kornicki 1994; Hur 2000; Aso 2013), Enkōan’s highly detailed illustrations of exhibitions offer the possibility of approaching the study of kaichō from the perspectives of visual and material culture. Centered on exhibitions held in the castle town of Nagoya, they also allow us to expand the study of kaichō display culture beyond the geographic and social context of the Edo capital. What kinds of images and objects accompanied the principal icon on these traveling exhibitions? How did spatial structures and display strategies dictate the experience of attending and viewing a kaichō? What role did legendary narratives associated with a temple’s principal icon play in shaping the programming of the event? What kind of social space was constructed by the exhibition? How, moreover, did Enkōan’s illustrated books function as representational objects and visual surrogates for the kaichō experience?

In this essay, along with briefly introducing Enkōan’s work, I closely examine a volume from the author’s kaichō series that documents the exhibition of a famous statue whose legendary history of travel and display both resonated with and was amplified by traveling exhibitions. Saga kaichō 嵯峨開帳, a manuscript preserved at Nagoya City Museum, documents the 1819 traveling exhibition of sacred temple treasures and the famous statue of Śākyamuni Buddha from the Kyoto temple Seiryōji 清凉寺 (hereafter Seiryōji Shaka 清凉寺釈迦) (Figure 2).1 Enkōan documented the kaichō of several important and well-known Buddhist icons over his lifetime; yet, there are two major reasons for beginning a study of Enkōan’s kaichō corpus with Saga kaichō. First, the Seiryōji Shaka was one of the most frequently exhibited and popular icons in Japan throughout the early modern period, and its auspicious mytho-history as a traveling image transported from ancient India to Japan reveals a unique symbiosis between the icon’s Edo-period kaichō and its own sacred origin narrative, or engi 縁起.2 Second, the book was produced in 1819 and arguably represents what could be considered Enkōan’s mature style. Perfected after more than forty years of engagement with illustrated books documenting kaichō and other popular urban events, his work from this time exhibits a degree of visual and semantic complexity not seen in earlier examples and is thus of great interest to the study of Nagoya’s rich literary and visual culture.

Figure 2.

Bound volume in the collection of Nagoya City Museum containing Sennyūji kaichō (1785) and Saga kaichō (1819). Reproduced from (Nagoya City Museum 2006, p. 7).

I begin by situating Enkōan’s work and the popularity of kaichō within the context of the urban exhibition culture that flourished in his lifetime. I then turn to a study of his Saga kaichō, beginning with the broader context of the Seiryōji Shaka’s own significant history of travel and display before proceeding to a close comparative analysis of image and text in the illustrated work. While Enkōan’s work at first appears to be concerned primarily with an objective and strictly observational account of the exhibition, I demonstrate how the author’s unique approach to visual reportage combined skillful manipulation of text and image to create what was a highly immersive reading experience that allowed the reader/viewer to access and participate in the kaichō virtually. Enkōan’s approach to visual composition borrowed widely from multiple print genres; yet, his kaichō series demonstrates a sophisticated adaptation of popular visual techniques that brought the reader into the world of the printed page. In concluding, however, I suggest that, while Enkōan and the figures who populate his work evince a clear interest in auspicious Buddhist subjects and narratives, the reality effect achieved by Enkōan’s combination of highly detailed drawings and an immersive reading experience may also have been guided by ideological interests reflective of Confucian values and the author’s privileged position in the dominant social order of the Tokugawa regime.

2. Enkōan and the Culture of Urban Spectacle

Enkōan’s Saga kaichō and his illustrated books documenting temple exhibitions held in Nagoya provide an important resource for examining the complex interplay between the sacred and profane in the context of late-Edo popular culture and a nascent culture of public display. They also belong to a larger corpus of illustrations that reveal the artist’s apparent fascination with urban life and the rich culture of spectacle that flourished during his lifetime. The cities of Edo, Kyoto, Osaka, and Nagoya had experienced enormous growth over the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, driving the emergence of a seemingly endless variety of attractions and popular entertainments that catered to the needs and desires of their increasingly diverse populations. While many city dwellers immersed themselves in the pleasure districts and theaters of the “floating world” (ukiyo 浮世), the thirst for novel experiences led artists and entrepreneurs to seek out venues to host traveling performances, sideshows, and exhibitions of curiosities—events that could draw in vast crowds and sizable profits. As the cities became more interconnected through networks of highways and trade routes administered by the shogunate, a burgeoning “industry” of traveling exhibitions and misemono attractions provided townspeople with access to a shared urban culture of spectacle (Markus 1985, pp. 505–6; Aso 2013, pp. 16–20).

Temples and shrines often proved the ideal venues for traveling shows, and many public events documented by Enkōan were held on the grounds of ostensibly Buddhist institutions. As Noriko Aso points out, even prior to the Edo period, entertainment districts were often located next to shrines and temples—sites that constituted what Amino Yoshihiko famously termed the sphere of the “unconnected” (muen 無縁), “in which high and low were intimately intertwined by virtue of both being Other” (Aso 2013, p. 18; Amino 1978). Accessible to commoners and elites alike, the sprawling halls and precincts of temples, their histories as hubs for travelers and pilgrims, and their established programs of rituals and festivals also guaranteed the physical space and the steady stream of visitors necessary to make exhibitionary ventures both compelling and economically viable.

In the summer of 1819, for example, shortly after the sacred treasures from Seiryōji had departed from the Nagoya temple Sairenji 西蓮寺, Enkōan attended an exhibition of bamboo-wicker animals that exhibited larger-than-life installations of lions, birds, insects, an elephant, and other exotic animals in the halls of the temple Nanatsudera 七ツ寺 (Figure 3). This same bamboo menagerie had been displayed to great acclaim at the Osaka temple Shitennōji 四天王寺 earlier in the spring, and its exhibition in Nagoya marked one stop on its route to Edo, where it would be installed at Sensōji 浅草寺 (Nagoya City Museum 2002). The Edo temple was a major center of the capital city’s culture of “prayer and play”, and it was notorious for its boisterous sakariba 盛り場 (“amusement quarters”) culture that revolved around carnivalesque misemono spectacles, circus-like performances, peep shows (nozoki), and other exotic entertainments (Hur 2000). No single temple in Nagoya ever seems to have reached the scale of year-round spectacle seen at Sensōji, but the castle town was nonetheless integrated into this shared culture of traveling entertainment.

Figure 3.

A phoenix and bear made of woven bamboo displayed for visitors at Nanatsudera. By Enkōan. 1820. Nagoya City Museum. Reproduced from (Nagoya City Museum 2002, pp. 11–12).

Enkōan attended and documented all manner of traveling exhibitions, public spectacles, and seasonal celebrations held at Nagoya’s temples and shrines over close to half a century. However, his illustrations indicate that he was just as fascinated by the people in attendance as he was by the events themselves. The men and women who fill the pages of Enkōan’s illustrated works reflect various slices of mid-Edo Japan’s increasingly diverse urban society. As cities expanded and the clearly delineated order of Tokugawa society gradually broke down over the first century of shogunal rule, diverse communities of urban commoners (chōnin 町人) eventually supplanted the ruling warrior class and the aristocracy as the drivers of economic and cultural production. The emergent urban class included merchants, artisans, moneylenders, and entertainers, as well as low-ranking entrepreneurial samurai who took up professional trades to supplement their diminished stipends. The mixing of social classes and the general heterogeneity of city life that characterized this new urban society was frequently condemned by Confucian moralists and conservative intellectuals in the circle of the Tokugawa regime (Harootunian 1991). Enkōan’s illustrated work, nonetheless, captures the vibrancy, excitement, and spectacle of this evolving culture.

In his portrayals of kaichō, the exhibition attendees include figures who appear to represent well-to-do merchants, priests, and female townspeople of various ages. The large number of male visitors in possession of swords also indicates the conspicuous presence of samurai—the ruling class to which Enkōan himself belonged.3 What little can be gleaned of Enkōan’s status as a samurai comes from records preserved in Nagoya that document his position as a retainer to the lords of Owari domain, a branch of the Tokugawa that served the interests of the Edo-based regime from their Nagoya headquarters. The Kōriki family had served the Owari since the founding of the shogunate, and in 1785 Enkōan inherited a middle-ranking position in the mounted guard (umamawari 馬廻). Like many samurai families, the Kōriki had seen their stipends steadily dwindle following the first century of Tokugawa rule—in their case from 700 koku 石at the founding of the shogunate to a modest low of 300 koku by Enkōan’s day.4 However, in contrast to the fates of the many lower-ranking samurai who turned to the civil arts and other cultural pursuits to supplement their reduced income, Enkōan was provided with sufficient means to support a relatively leisurely lifestyle. In other words, while many of his peers were drawn to the lifestyle and culture of the urban commoners out of some disaffection with their diminished positions in samurai society, the hierarchical system continued to work for Enkōan, whose privileged position within the umbrella of Tokugawa warrior rule enabled him to pursue an intellectual interest in the thriving culture of urban spectacle.

Along with his clear interest in the social experience of Nagoya’s urban display culture, it was the exhibited objects and other contents of the attractions that served as the ostensible focus of Enkōan’s work. In the case of the traveling kaichō exhibitions, these were the sacred treasures, historical artifacts, and Buddhist icons that were brought to Nagoya from distant temples. This exhibiting of sacred objects had roots in much earlier medieval practices seen in and around Kyoto, in which temples unveiled their painted or sculpted icons not for the paying public but at private viewings for elite patrons. In most cases, largesse was bestowed on a temple in exchange for the unique opportunity to worship its hibutsu 秘仏, a sacred image normally concealed from view behind the doors or curtains of a votive shrine.5 Following the relocation of the capital to Edo in the early seventeenth century, however, the loss of local revenue sources and the central government’s increasingly depleted resources for contributing to repairs and upkeep of provincial temple buildings led some institutions to turn to public kaichō as an important mode of fundraising.6 Just as misemono shows traveled from city to city, many temples targeted the populations of Edo and other urban centers, physically transporting their most revered icons and sacred objects to be exhibited in large, urban temple halls. These “traveling curtain openings”, or degaichō, reached their height of popularity during Enkōan’s lifetime when their incorporation of misemono spectacle and other entertainment brought together the worlds of the sacred and the profane.7

These public displays of Buddhist paintings, statues, and ritual objects represented one aspect of Edo-period Japan’s broader urban culture of spectacle and display discussed above, but they should also be regarded as a key development in the reception history of ancient and medieval Buddhist art and material culture. Preceding both the importation of Euro–American exhibition practices in the Meiji 明治 period (1868–1912) and subsequent policies advocating for the preservation of Buddhist images as objects of cultural patrimony, the history of kaichō demonstrates that Japan already possessed a sophisticated and autochthonous culture of display centered primarily on large-scale public exhibitions held on the grounds of Buddhist temples.8 While Aso points to the popularization of bussankai 物産会 (displays of manmade and natural products) from the mid-eighteenth century onward as “the most direct antecedent to modern museums” (Aso 2013, p. 16), it should be recognized that kaichō preceded these more intellectual enterprises and also featured historical objects that appealed to the population’s growing interest in antiquarianism.

Enkōan’s illustrated records of kaichō show that the experience of visiting these periodic exhibitions was not so distant from what one would expect when visiting a museum today. Visitors paid a small entrance fee (often after queuing in crowds for several hours) to view a wide range of exhibits displayed alongside descriptive labeling, some of well-known historical significance and others lesser-known curiosities (Figure 4).9 Printed booklets, amulets, and other objects produced specifically for the exhibition were also available for purchase. As will be seen below in the case of the Seiryōji Shaka’s frequent exhibitions, visitors could even return home with a printed reproduction of the lending temple’s famous icon that was the major draw of the event.

Figure 4.

Display of objects in one of the exhibition spaces for the 1784 Sennyūji kaichō. By Enkōan. 1785. Nagoya City Museum. Reproduced from (Nagoya City Museum 2006, pp. 18–19).

In the Edo capital, the raucous misemono shows and entertainment held near the exhibitions were one important factor that fueled increasing interest in kaichō. This has led scholars to debate the degree to which the culture of kaichō was either symptomatic of a general decline in Buddhism and religiosity during this period or somehow itself a genuine expression of religious piety.10 Were visitors drawn to the opportunity to worship and form karmic ties (kechien 結縁) with the unveiled icons, or were they more interested, as many contemporary commentators would attest, in the spectacle of the surrounding festivities? Likely, the answer was often both; yet, this tension highlights how the phenomenon of kaichō in the early modern period may well have contributed to what has been described as “the contested status of icons as both religious and secular objects” (Suzuki 2007, p. 131). The history of kaichō, and especially the traveling degaichō, is therefore critical not only to better understanding the pre-Meiji origins of public display culture in Japan but also the evolving attitudes toward sacred images in the decades prior to the importation of modern values that reconceptualized ancient Buddhist icons as bijutsuhin 美術品, or works of art.11

One such icon whose early modern reception was greatly shaped by its many traveling exhibitions held in the Edo period was the Seiryōji Shaka, whose 1819 degaichō is documented in Enkōan’s Saga kaichō. In his introduction to the work, Enkōan declares that the Seiryōji Shaka was one of three miraculous Buddhist icons (reibutsu 霊仏) that had traveled from India to Japan, but the only one whose degaichō allowed large numbers of people to form karmic connections with the image (Nagoya City Museum 2006).12 These degaichō not only provided visitors with the opportunity to worship what was believed to be the oldest portrait icon of the historical Buddha, but they also resonated with the statue’s legendary history of travel and display. This history was central to the identity of the icon and was foregrounded by promoters of its kaichō, so that while many visitors were certainly drawn by intellectual and antiquarian interests, they may also have seen themselves as somehow partaking in the icon’s sacred and continually unfolding history. Before moving on to examine how Enkōan used text and image to simulate the experience of attending the statue’s kaichō, it is thus important to place the Seiryōji statue’s exhibition within the broader mytho-history that influenced its reception in Edo-period display culture.

3. The Travels and Exhibitions of the Seiryōji Shaka

In his Saga kaichō, Enkōan documented an exhibition of the Seiryōji Shaka and other sacred temple treasures owned by Seiryōji that was held at the Nagoya temple Sairenji for twenty days beginning in the fourth month of 1819 (Enkōan 1962, pp. 260–61). However, this was likely not the first kaichō of the famous statue that Enkōan witnessed in his home province. The castle town was a frequent stop for sacred images en route to and from Edo, and he may have encountered the statue as early as 1785, when it was displayed for fourteen days at the temple Yōrinji 養林寺.13 Since its first public degaichō held at the Edo temple Gokokuji 護国寺 in the summer of 1700, traveling exhibitions had become a lucrative form of fundraising for Seiryōji, so that between 1700 and 1860, the statue was transported from Kyoto to Edo at least ten times.14 Following the first exhibition at Gokokuji, the remaining nine were all held at Ekōin 回向院, a temple in the Ryōgoku 両国 district of Edo that was a center for traveling kaichō exhibitions in the city.15

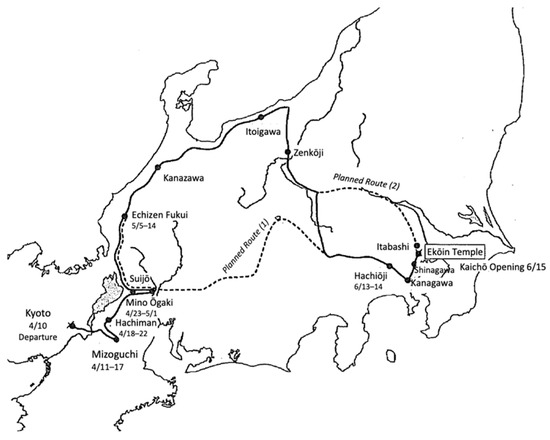

When the Seiryōji Shaka departed from Kyoto on one of its periodic Edo degaichō, its procession typically followed one of two routes along which it would make occasional stops for short-term display at local temples before continuing to its ultimate destination in the capital. An eastern route took the statue through Owari (modern-day Nagoya and Aichi 愛知 prefecture), Hachiōji 八王子, and Shinagawa 品川, while the northern route proceeded along the Japan Sea through Echizen 越前 and Echigo 越後 provinces before cutting eastward through Shinano 信濃 province and ultimately arriving in Ryōgoku. Umihara Ryō 海原亮 has reconstructed the routes that the statue traveled in 1801, based on records preserved in the Sumitomo Historical Archives (Umihara 2005). These records indicate that the statue departed Kyoto on the tenth day of the fourth month and traveled north up the eastern coast of Lake Biwa 琵琶湖. From Lake Biwa, its procession cut up along the Japan Sea coast, where it made stops at Fukui 福井, Kanazawa 金沢, and Itoigawa 糸魚川, and passed through Shinano and the mountains of modern-day Gifu 岐阜 prefecture. After two months on the road, it then entered Kantō 関東 via Hachiōji and Shinagawa before arriving in Ryōgoku in time for the start of its kaichō at Ekōin on the fifteenth day of the sixth month (Figure 5).16

Figure 5.

Route traveled by the Seiryōji Shaka for a degaichō held in Edo in 1801. Adapted from (Umihara 2015, p. 78).

Ultimately, however, the statue’s travels were not limited to this Kyoto–Edo circuit. Tsukamoto Shunkō’s 塚本俊孝 study of Seiryōji temple records indicates that between 1700 and 1899, the statue was removed from the temple and transported for fundraising exhibitions throughout the country at least fifty times, averaging a trip once every two years and traveling as far as Kyushu (Tsukamoto 1982, p. 19). Even excluding its mythical travels in Central Asia and China (see below), the Seiryōji Shaka was arguably Japan’s most widely traveled Buddhist statue.

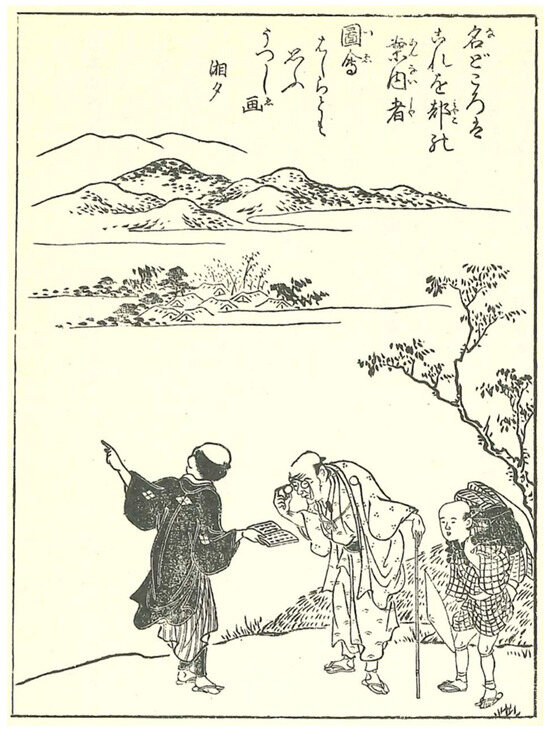

To promote these exhibitions, the priests of Seiryōji inevitably drew from the statue’s famous origin narrative to attract visitors and spread the cult of the auspicious icon. The first images from Enkōan’s account of the statue’s 1819 kaichō depict banners and placards strung around the exhibition sites and host cities to promote the exhibition of the famous “Śākyamuni Buddha Transported Across Three Countries” (Sangoku denrai Shaka Nyorai 三国伝来釈迦如来) (Figure 6). Just as museum visitors today purchase postcards, catalogues, and other exhibition souvenirs, variations of the statue’s engi recounting the miraculous origins and travels of the auspicious statue were reproduced in the form of small, illustrated books made specifically for distribution at these traveling kaichō.17 Many also purchased woodblock-printed images of the icon that were prepared in the tens of thousands. A small number of these printed images survive, and scholars have only recently begun to recognize the significant role played by the distribution of these kaichō prints in the proliferation of painted and sculptural copies of the Seiryōji image made during the Edo period (Sanada 2016; Oku 2009; Umihara 2005).18 As Sanada Takamitsu 真田尊光 suggests in his study of kaichō prints and blocks preserved at Seiryōji and Kanazawa Bunko 金沢文庫, a well-known painting of the Seiryōji Shaka by Hanabusa Icchō 英一蝶 (1652–1724) in the collection of Shōkyōji 承教寺was likely based on a print distributed at the statue’s first Edo degaichō in 1700, while a later sculptural copy of the icon in the collection of the Adachi City Museum in Tokyo also appears to have been mediated through kaichō prints (Sanada 2016).

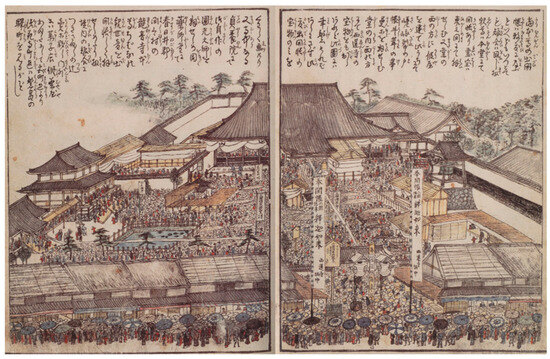

Figure 6.

Crowds of visitors fill the grounds of Sairenji. Excerpted from Saga kaichō. By Enkōan. 1819. Nagoya City Museum. Reproduced from (Nagoya City Museum 2006, pp. 32–33).

Among the statues displayed at degaichō throughout Japan, the Seiryōji Shaka was unique for its compelling conceptual links between the traveling exhibition of the statue and the central themes of travel, display, and replication found in the many versions of its engi.19 The image enshrined in Seiryōji today is, in fact, a tenth-century copy of a lost Chinese statue, but over the course of the medieval period, a narrative developed around the image equating it with the legendary first image of the Buddha, a “living body image” (J: shōjin butsu 生身仏) made of sandalwood that was commissioned by the Indian king Udayana during the lifetime of the historical Buddha.20 This ur-icon, according to one popular version of the narrative, was brought from India to the Central Asian kingdom of Kucha by the father of the great translator Kumārajīva (344–413) and enshrined in the palace of the Kuchan king Bai Chun 白純 (?–?). Both Kumārajīva and the statue were later seized and taken to Chang’an長安, then the capital of the Former Qin 前秦 (351–395), and, over the following centuries, the statue was repeatedly reinstalled in the courts and temples of later Chinese rulers, eventually being enshrined in the temple Kaiyuansi 開元寺 in Yangzhou 楊州 during the Tang dynasty (618–907). When the Japanese pilgrim-monk Chōnen 奝然 (938–1016) traveled to China in 983, a statue that was believed to correspond with this original Udayana image had been relocated from Kaiyuansi to a hall located on the grounds of the Imperial Palace in Kaifeng 開封.21 In 985, after petitioning Emperor Taizong 太宗 (r. 975–997) of Northern Song, Chōnen was granted permission to commission his own copy of the statue, which he then brought back with him on his return to Japan.22

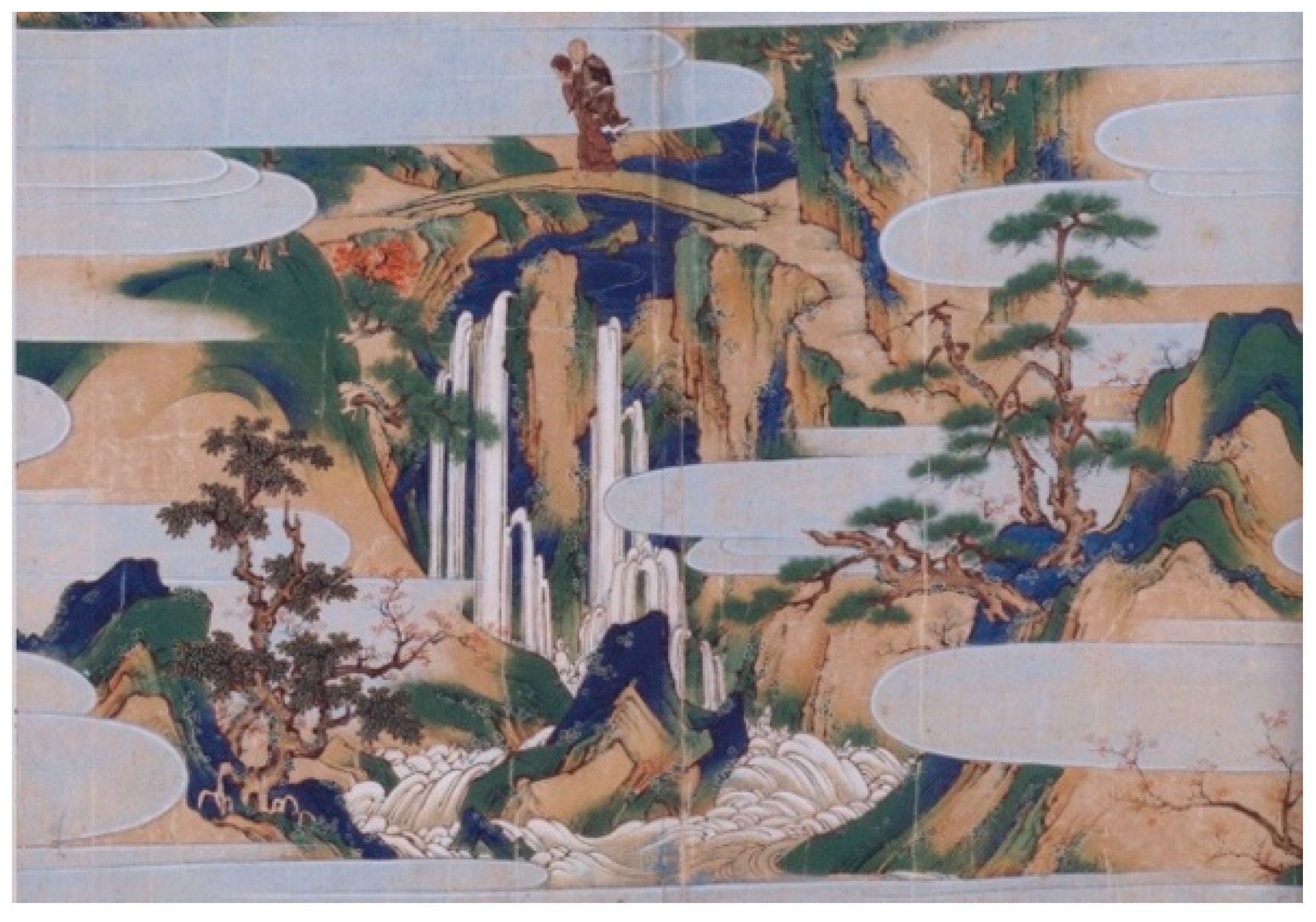

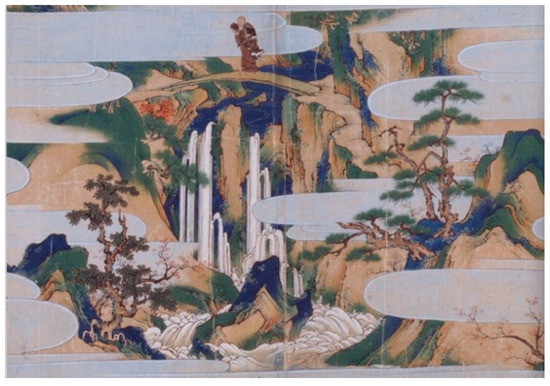

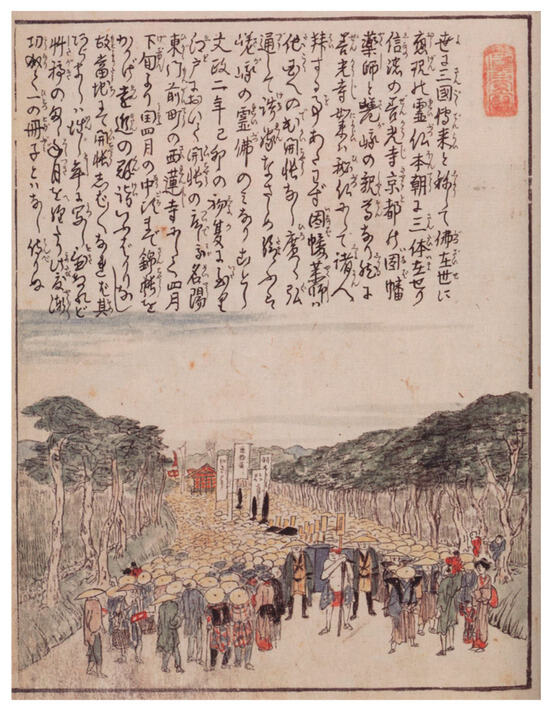

By the twelfth century, the Seiryōji Shaka had become the subject of renewed attention among prominent figures in the orbit of the court, many of whom came to identify the statue not as a copy but as the original Udayana image itself. This belief was partly fueled by an alternative version of the Udayana legend then circulating in Kyoto. According to this revisionist account, the original Udayana image was secretly switched with Chōnen’s copy prior to his return to Japan. Taira no Yasuyori’s 平康頼 (fl. 1177–1220) collection of setsuwa 説話 tale literature, Collection of Treasures (Hōbutsushū宝物集), introduced the idea that Chōnen surreptitiously replaced the copy he commissioned with the original Indian image before the envoy’s departure. This account is further embellished in Origin Tale of the Shaka Hall (Shakadō engi 釈迦堂縁起絵巻), a six-volume set of handscrolls illustrated by Kano Motonobu 狩野元信 (d. 1559) which claims that the statue secretly changed places with its prototype the night before Chōnen’s departure, acting of its own agency and evincing its own desire to cross the sea to Japan (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Chōnen’s copy and the original Udayana icon secretly change places before Chōnen’s return to Japan. Origin Tale of the Shaka Hall. Painting by Kano Motonobu. Ca. 1515. Seiryōji Temple, Kyoto. Reproduced from (Nara National Museum 1975, p. 298).

Multiple scenes throughout Motonobu’s Origin Tale of the Shaka Hall repeatedly emphasize both the Seiryōji Shaka’s unique agency as a traveling icon and the centrality of display to its sacred biography. In one of its most vividly imagined scenes, Kumārajīva’s father and the statue take turns carrying one another across a lush and dreamlike mountainous landscape as they travel between India and Kucha (Figure 8). In the following scenes, the statue is depicted either in the act of traveling or being displayed behind open curtains in the palaces and temples of Central Asian and Chinese rulers (Figure 9). The sixth scroll of the set, which comprises a purely textual account of the statue’s medieval history, continues to emphasize the role that periodic display played in its reception in Japan, noting that the first kaichō on the grounds of Seiryōji was held for the visit of the aging regent (shikken 執権) Hōjō Tokiyori 北条時頼 (1227–1263) in 1261. In the fifteenth century, it continues, Ashikaga Yoshimasa 足利義政 (1436–1490) reputedly donated curtains made of Ming-dynasty brocade to the temple, possibly also to mark the occasion of a private viewing held for the shogun.23

Figure 8.

Origin Tale of the Shaka Hall. Painting by Kano Motonobu. Ca. 1515. Seiryōji Temple, Kyoto. Reproduced from (Ikeda et al. 2017, p. 133).

Figure 9.

Origin Tale of the Shaka Hall. Painting by Kano Motonobu. Ca. 1515. Seiryōji Temple, Kyoto. Reproduced from (Ikeda et al. 2017, p. 133).

Long preceding the statue’s earliest kaichō in Edo, these textual and visual records of its history attest to the fact that the statue’s transportation to new lands and its periodic display before sovereigns and ruling authorities were central to the interpretation of the Seiryōji Shaka as a “living image” and a uniquely auspicious icon. In turn, knowledge of its history and engi colored the icon’s reception and contributed to its enormous popularity as a kaichō image in the Edo period so that its travels beyond Kyoto may have been interpreted as part of the ever-expanding biography of the statue. When the Tokugawa shogunate issued the temple permission to display the statue at the temple Gokokuji in Edo for the first time in 1700, for instance, the statue was also brought to and displayed briefly in Edo Castle prior to its return to Kyoto.24 While the Tokugawa merely tolerated kaichō exhibitions of other icons hosted by temples in the city, the installation of this image in the very center of Tokugawa political authority suggests that they too may have viewed themselves as part of a long line of Asian hegemons who welcomed, displayed, and worshiped this globetrotting image.

Enkōan’s record of the Seiryōji Shaka’s exhibition in 1819 was, therefore, part of a much broader history of the statue’s reception in the early modern period that itself intersected and resonated with a longer mytho-history of the statue as a living, traveling image. By visiting and creating karmic ties with the image during its many degaichō in and outside of Edo, people not only learned about the traveling icon’s miraculous biography but fully immersed themselves in its continuing and evolving story, surrounding themselves in the textual and material accumulations of its extraordinary history. Belief in the image and its history was then further perpetuated through the copies of the engi and the prints of the icon’s likeness that were purchased at kaichō and circulated within local communities along the routes of its traveling exhibitions. For those unable to attend the event, Enkōan’s work provided visual documentation of exhibition spaces and the various objects that were displayed along with the Seiryōji icon, but as will be seen below, its complex use of text and image also allowed the reader to participate in the kaichō through something akin to a virtual experience.

4. Text, Image, and Immersive Reading in Enkōan’s Saga kaichō (1819)

Having briefly considered the background of Edo-period exhibitionary culture and the broader historical contexts of travel and display that shaped the Seiryōji Shaka’s early modern reception, we can now turn to an analysis of the visual and textual strategies employed by Enkōan in his account of the statue’s 1819 degaichō. This and his other illustrated records of exhibitions reflect Enkōan’s skillful adaptation of various print genres that had roots in the major publishing centers of Edo, Kyoto, and Osaka. In the years that Enkōan was active, Nagoya was home to the country’s largest lending library, Daisō 大惣, which played a central role in exposing the city’s residents to a wide variety of literary works and genres from Edo, including “yellow-cover” popular fiction (kibyōshi 黄表紙), “pictures of famous places” (meisho zue 名所図会), and single print works of ukiyo-e 浮世絵 (McGee 2017, pp. 115–17). Enkōan borrowed techniques from all these genres, but close attention to his clever manipulation of text and image reveals how these elements were adapted to create an immersive and multivalent reading experience that brought the experience of attending the kaichō to life for his readers.

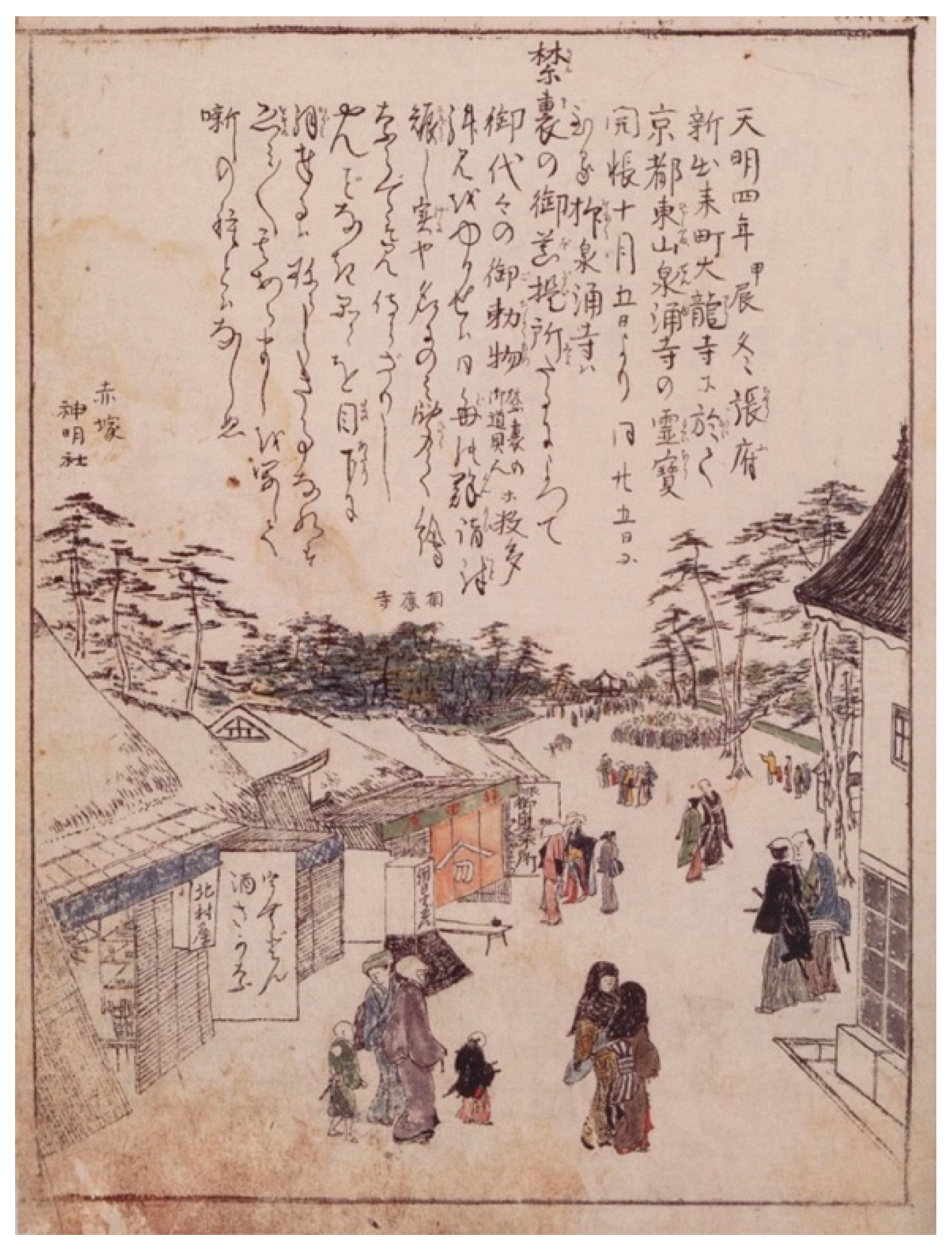

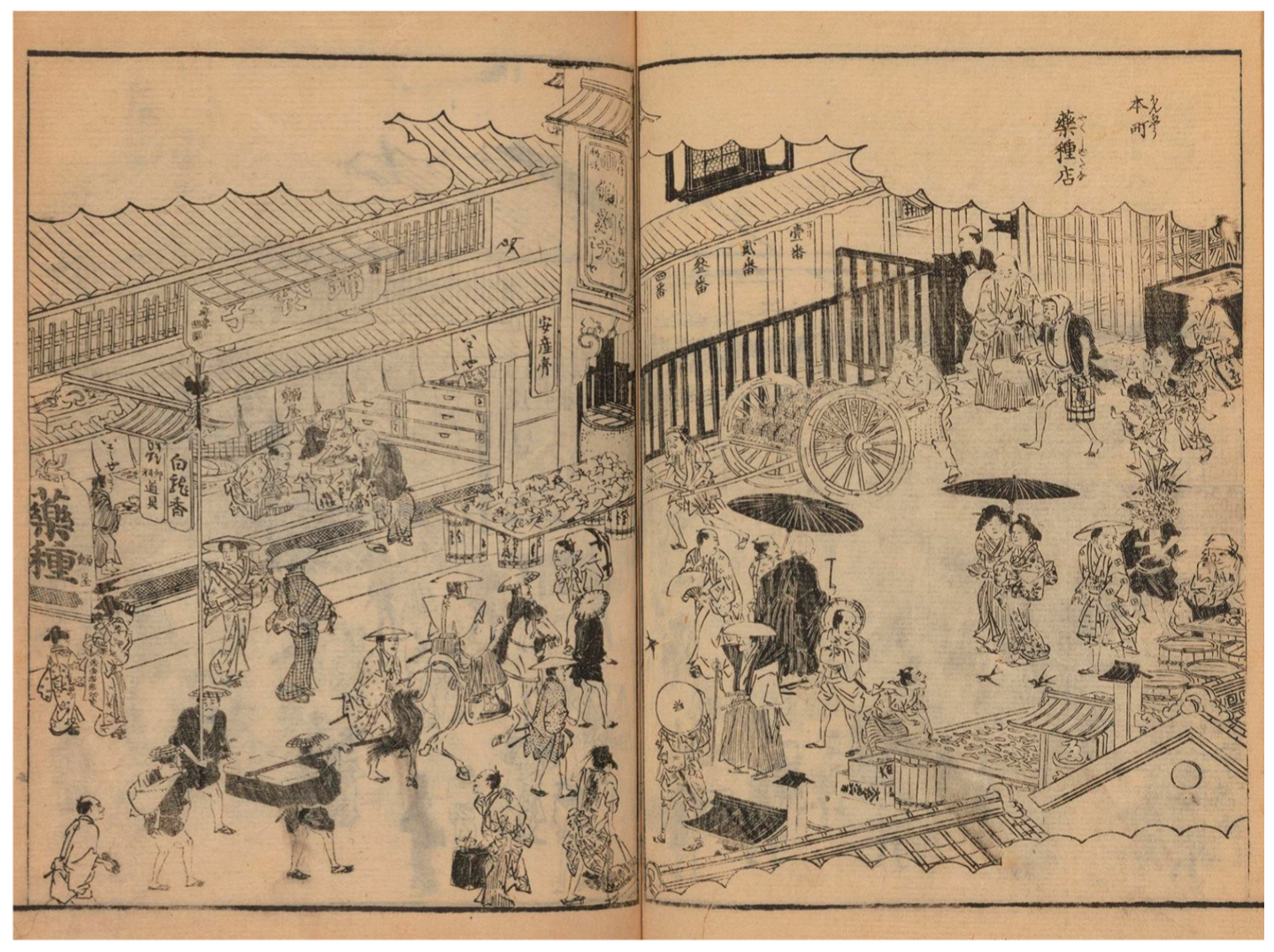

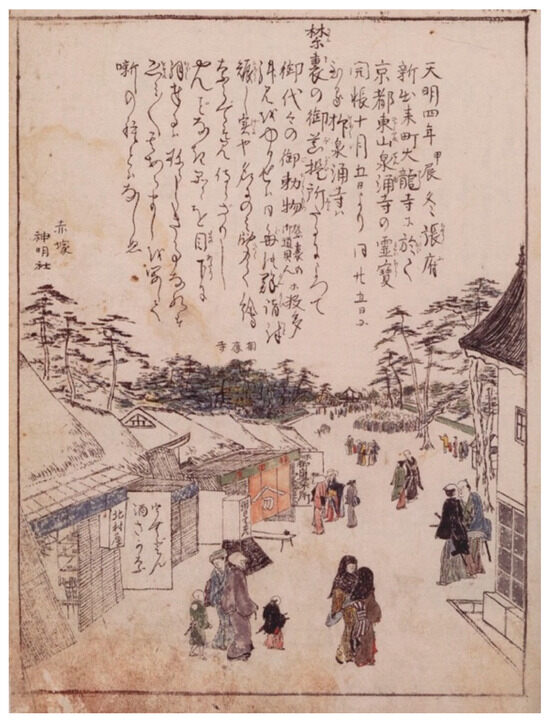

The influence of the meisho zue genre, for example, can be seen in Enkōan’s use of sequential progression to move the reader through the various temple sites that played host to degaichō. His earlier Sennyūji kaichō 泉涌寺開帳 from 1784, which documents the exhibition of sacred treasures from the Kyoto temple Sennyūji 泉涌寺, opens with a single-page composition of townspeople conversing in a street lined with small, thatch-roofed shops, their bodies twisting away from the viewer toward a crowd that condenses as the perspective fades into the distance (Figure 10). The text, in a highly legible mix of kanji and phonetic hiragana, sets the scene by recounting that in the fourth year of Tenmei 天明 (1784), the temple treasures from Kyoto’s Higashiyama Sennyūji were displayed at Dairyūji 大龍寺from the fifth through the twenty-fifth day of the tenth month. In the following two two-page spreads, bird’s-eye-view compositions introduce the temple site and the surrounding stalls set up along the streets leading to the precinct. The next pages enter the temple exhibition space, providing an elevated view of the figures approaching from the lower right and the artifacts displayed on the walls to the reader’s left (Figure 11). The angled, overhead composition resembles the kinds of medium-distance views that orient scenes such as “Honchō 本町” from Edo meisho zue 江戸名所図会 (Figure 12).

Figure 10.

Townspeople make their way along a shop-lined street leading toward Dairyūji. Excerpted from the opening page of Sennyūji kaichō. By Enkōan. 1784. Nagoya City Museum. Reproduced from (Nagoya City Museum 2006, p. 9).

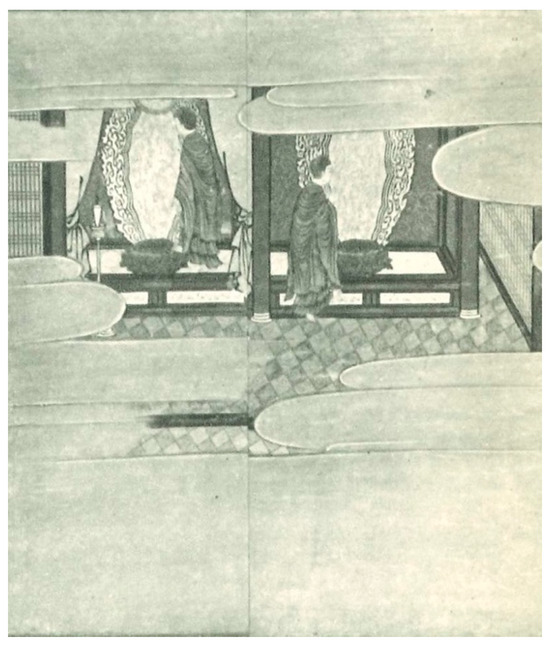

Figure 11.

The first exhibition space inside Dairyūji. Excerpt from Sennyūji kaichō. By Enkōan. 1784. Nagoya City Museum. Reproduced from (Nagoya City Museum 2006, pp. 14–15.).

Figure 12.

“Honchō,” from Edo meisho zue, vol. 1. Smithsonian Libraries, Washington D.C. https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.1078448.39088019225325 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

While Enkōan’s work incorporates many compositional and visual features that resonate with the meisho zue genre, a major deviation is seen in his use of text, which has a more immediate relationship with the illustrations. In meisho zue, the content of the text tends to frame the scene by describing general information about the city or landmark taken up as its subject. This includes the etymologies of place names, relative geographic location, associations with historical figures and literary works, or popular seasonal festivities held at the location. The images, however, place importance on the scenic beauty of the famous place or the bustling activity of myriad travelers and townspeople who occupy the site. By contrast, Enkōan’s use of text serves multiple functions, frequently describing the scene or providing direct observational commentary on the objects and activities depicted within the image. In the scenes of kaichō exhibition spaces, for example, the text’s positioning within the composition follows the spatial layout of the image, with brief lines of text describing objects on display immediately below or adjacent. The first three lines in Figure 4, for example, identify the golden object beneath as a pagoda-shaped reliquary containing the Buddha’s relics formerly worshiped by Empress Tōfukumon’in 東福門院 (1607–1678), an object that is still preserved in the collection of Sennyūji today. At times, the text relates directly to the figures’ actions as well, fully linking the figures, their surroundings, and the objects.

Also evocative of meisho zue are the many pointing figures found throughout Enkōan’s kaichō series, including the temple staff who directs a long stick at the portraits of the priests Shunjō, Daoxuan, and Yuanzhao in the first interior scene of Sennyūji kaichō (Figure 13), allowing the group of listening visitors to function as visual surrogates for the reader. As a kind of etoki 絵解き (picture explainer), the presence of the pointing figure causes the inscribed text to shift from a non-diegetic to a diegetic function, creating a displacement of the reader’s subjective position to that of the illustrated crowd that “listens” to the text. A similar effect is achieved through the language of the text as well. Lines of text above the display objects appear primarily as descriptive labeling but are occasionally interspersed with the use of the spoken vernacular copular “de gozaru” でござる, which transforms the reader suddenly into a listener.25

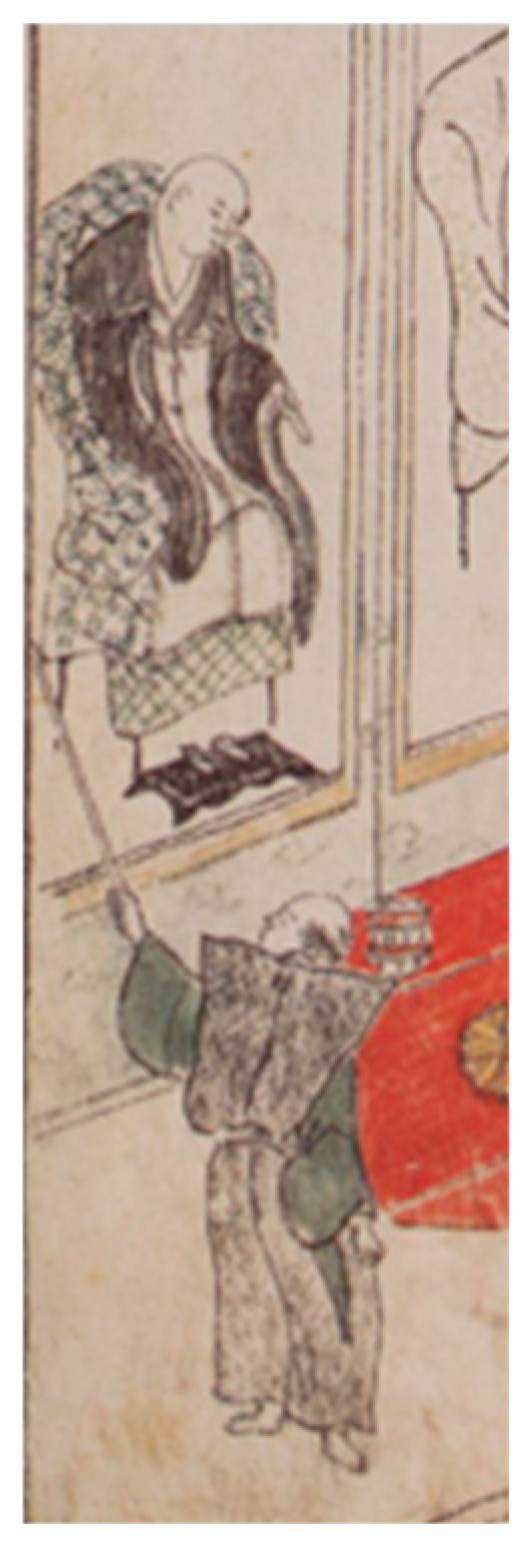

Figure 13.

Detail of Figure 11.

This polyphony of speaking and listening is most dynamically portrayed in the fourth exhibition space (Figure 14). Here, a figure standing behind the railing that separates the visitors from the inner display space once again directs the viewer’s attention to the left by pointing a stick at an elaborate hanging curtain and seat once owned by Emperor Go-Mizunoo 後水尾 (1596–1680). Turning his head in the opposite direction, he gazes down to the right at a smiling woman in yellow robes whose head rises among a crowd of seated figures. To the right of this woman, a male visitor reaches out above the heads of his companions, pointing to a set of lacquer inkstone cases. A woman to his right points left, either to the same set of lacquer boxes or to a statue of Fudō Myōō 不動明王, while turning her head to her left to speak to another woman who frames the corner of the composition.

Figure 14.

Display of objects in one of the exhibition spaces for the 1784 Sennyūji kaichō. Excerpt from Sennyūji kaichō. By Enkōan. 1785. Nagoya City Museum. Reproduced from (Nagoya City Museum 2006, pp. 18–19).

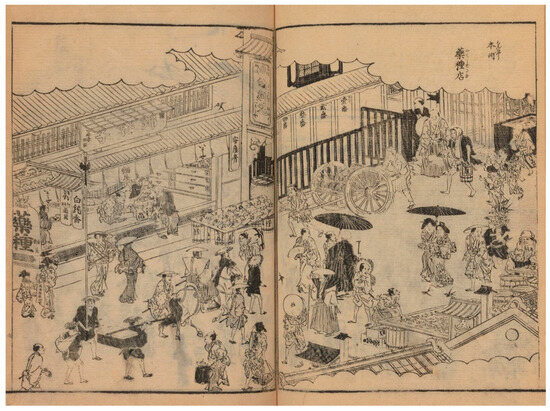

The art historian Chino Kaori 千野香織 and architectural historian Nishi Kazuo 西和夫 have observed that the depiction of finger-pointing in medieval narrative handscrolls functioned strategically to guide the viewer horizontally through the image, directing them to the areas of the image deemed most essential (Chino and Nishi 1991, p. 83). Miyakoshi Naoto 宮腰直人 has also argued that finger-pointing played a central role in the narrative function of handscrolls through the early modern period and served as a link between text and image (Miyakoshi 2000). Building on these scholars’ work, Robert Goree asserts that the presence of anonymous human figures and finger-pointers within meisho zue served two key functions. First, they helped the viewer to better comprehend the space of the famous place. Second, they helped link the descriptions in the text with the important features of the meisho, establishing “specific interpretive contexts” by directing the viewer to focus on what the editors wished to emphasize (Figure 15) (Goree 2010, pp. 149–69). In Enkōan’s work, however, the action of finger-pointing, combined with reciprocating gazes and other bodily movements, seem also to be self-reflexive, drawing attention to the agency of the pointers themselves while simultaneously asking both the viewer and the illustrated audience to consider the works on display through a reading of the inscribed text, and to temporarily embody similar subject positions.

Figure 15.

Pointing figure from Shin miyako meisho zue 新訂都名所図会. Reproduced from Akisato Ritō 秋里籬島, Shintei Miyako meisho zue v. 4 (Tokyo: Chikuba Shobō 1994, p. 189).

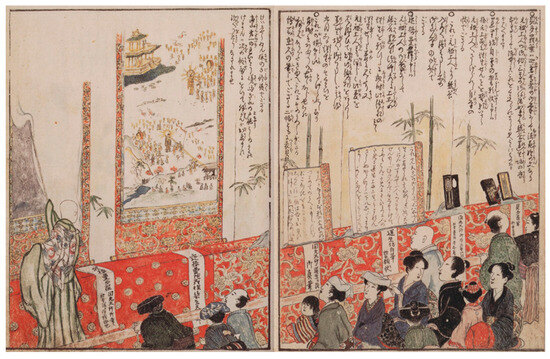

Composed thirty-five years after Sennyūji kaichō, Enkōan’s ehon of the 1819 degaichō of the Seiryōji Shaka and sacred treasures from Seiryōji maintains a remarkable consistency with the earlier work in terms of visual composition and overall organization. Like Sennyūji kaichō, it opens with a single-page composition that illustrates a tree-lined street filled with crowds of people receding into the distance (Figure 16). The text in the upper half of the page briefly alludes to the auspicious origins of the Seiryōji Shaka as a miraculous icon that traversed three countries (yo ni sangoku denrai to shōshite, butsu zaise ni ōgen no reibutsu 世に三国伝来と称して、仏在世に応現の霊仏26), noting the date and location of the kaichō and the significance of other popular treasures that were exhibited along with the icon. The following two pages are filled with a detailed overhead view of Sairenji’s temple grounds that overflow with eager visitors (Figure 6). This introductory text is primarily devoted to the description of the temple grounds, including the locations of certain exhibitions, rest areas, and other sites of interest to those attending the kaichō.27

Figure 16.

Crowds gather in the street leading to the Seiryōji kaichō at Sairenji. Excerpt from Saga kaichō. By Enkōan. 1819. Nagoya City Museum. Reproduced from (Nagoya City Museum 2006, p. 31).

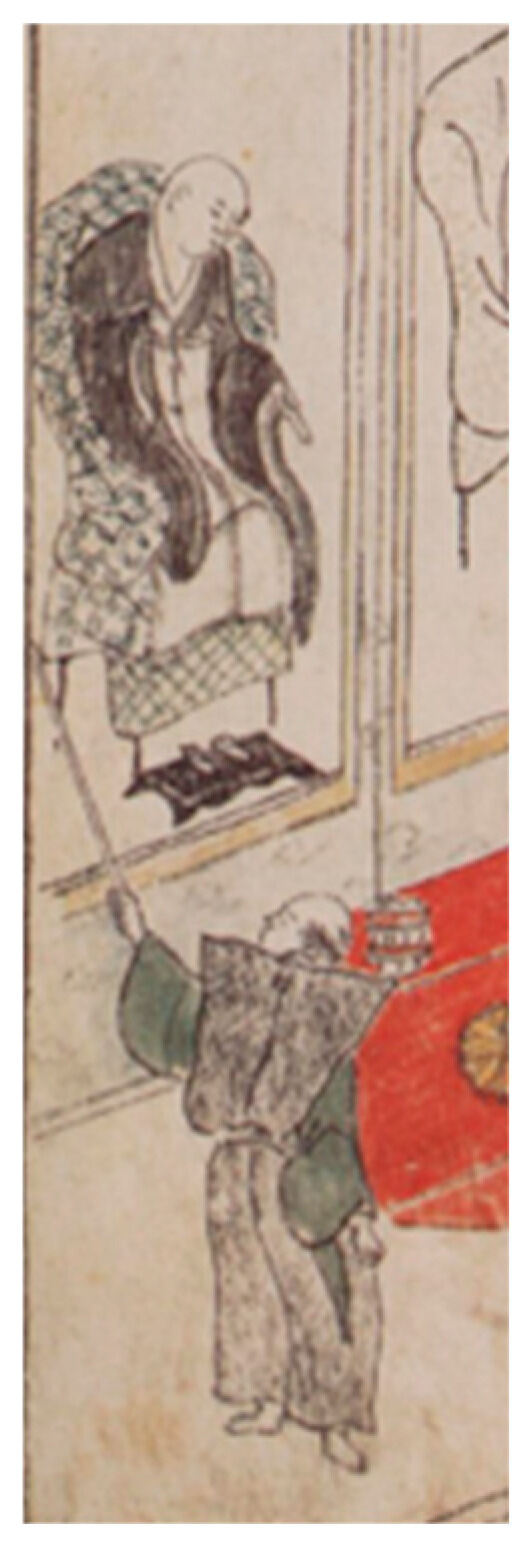

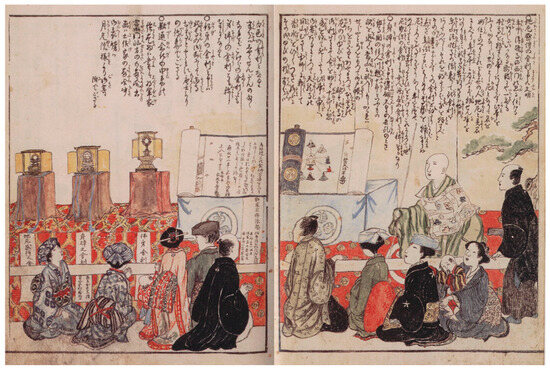

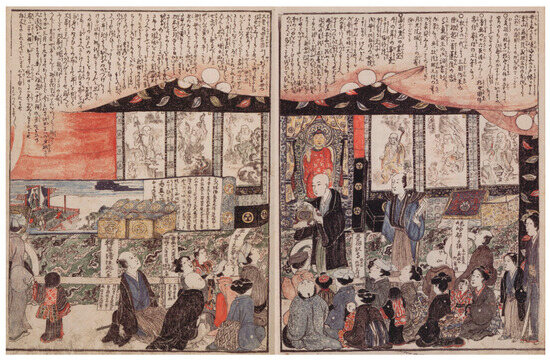

In his depiction of exhibition spaces, Enkōan returns to a horizontally oriented composition seen in many of his ehon of viewers arranged side by side in the lower register. A railing separates these crouching figures from the display tables and priests who describe the treasures, while textual inscription commenting on the display fills the upper register. The relationship between the priest and the descriptive text in the first exhibition room is rendered more explicit than in Sennyūji kaichō (Figure 17). As the only figure turned fully toward the reader, the priest looks over the range of objects on display, his mouth slightly open. Instead of directing his etoki stick to one object, the stick is raised upwards, forming a direct visual link with the text, as if emerging from his mouth. The text’s description of the Seiryōji version of the Yūzū nenbutsu engi emaki 融通念仏縁起絵巻 (The Illustrated Miraculous Origins of the Yūzū Nenbutsu School) and several displayed reliquaries is presented in bullet points rather than written directly above their referents, creating a unified compositional element of text that is glossed for readability with furigana. Here, the monk functions clearly as the sole speaker of the text, and the complex polyphony of active speaking and listening subjects visible in Figure 14 has been simplified to the speaking priest and the passively listening, seated visitors.

Figure 17.

An exhibition display from Saga kaichō. By Enkōan. 1819. Nagoya City Museum. Reproduced from (Nagoya City Museum 2006, pp. 38–39).

However, these compositions introduce a new visual and semantic complexity not seen in Sennyūji kaichō. In this and the following pages, many of the works displayed are textual and are rendered to be legible to the reader of the ehon. In addition, the objects are accompanied by fully readable labels, reducing the visitors’ reliance on the explanations of the attendant staff. For example, several lines from the oath of the repentant warrior Kumagai Naozane 熊谷直実 (1141–1207) can be read,28 and indeed the positioning of a male figure in front of the document suggests his engagement in the act of reading (Figure 18). While the visitors appear more passive than in the previous ehon, seated with their backs facing the reader with minimal gesticulation, they are in these works endowed with the new agency of reading, and the legibility of the visualized texts allows readers of the ehon to share in this active agency of these reading subjects.

Figure 18.

An exhibition display from Saga kaichō. By Enkōan. 1819. Nagoya City Museum. Reproduced from (Nagoya City Museum 2006, pp. 40–41).

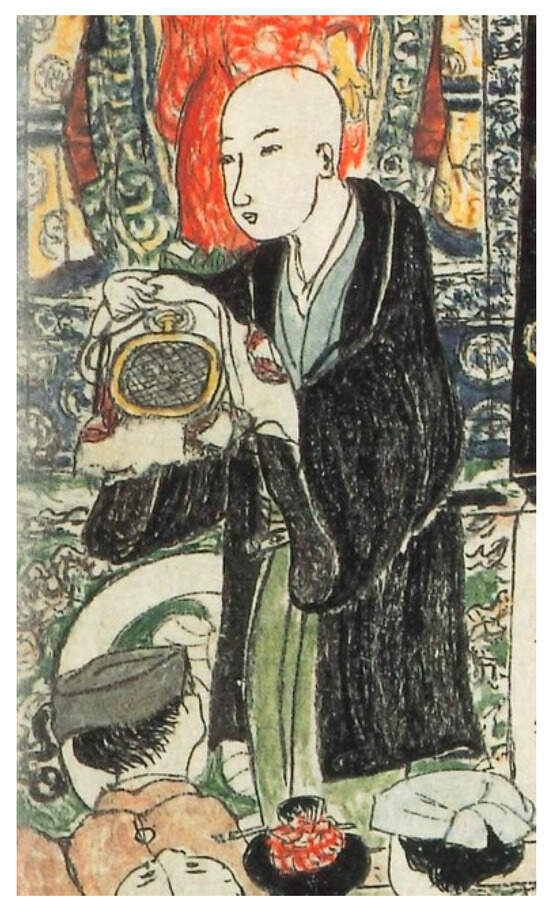

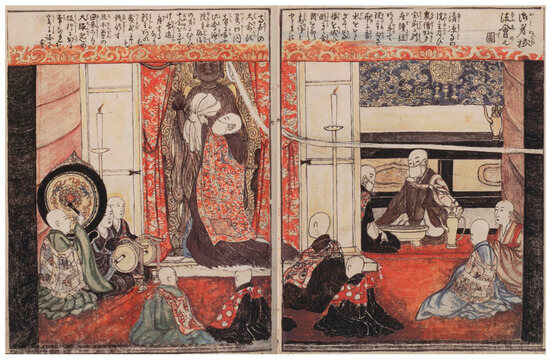

Enkōan’s creative intermixing of images within images, texts that describe texts, and a multi-directionality of speaking, reading, and listening culminate in the last interior scene of this work (Figure 19). This final exhibition space visualized in Saga kaichō deserves considerable attention as one of the most sophisticated and complex compositions in Enkōan’s oeuvre, densely layered with people, objects, texts, and images. Near the center, a shaven-headed figure in black robes resembling a Buddhist priest stands before a throng of seated observers holding a small, mysterious round object. Behind the priest, golden curtains frame a painted image of the Seiryōji Shaka, fully colored in crimson robes with gold patterning. Flanking the Buddha image are six monochrome drawings of arhats, three extending to the edge of the right page and three stretching halfway through the left. In addition to these paintings, a display table running the full length of the composition exhibits multiple objects and images. An ornately designed lacquer box at the far right, for example, is identified by its label as a gift from the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa (the shogun who once gifted the statue a brocade curtain), while the various contents of other boxes are identified by similar labels.

Figure 19.

The final exhibition room portrayed in Saga kaichō. By Enkōan. 1819. Nagoya City Museum. Reproduced from (Nagoya City Museum 2006, pp. 44–45).

The display table in the left image is taken up by a set of six illustrated scrolls, one of which is partially unrolled to reveal a portion of text followed by a polychrome image of figures in a palatial setting. A label beneath these scrolls identifies this as the six volumes of Seiryōji’s Origin Tale of the Shaka Hall discussed in the previous section. The scene depicted in the unrolled scroll corresponds to the first scene of the fourth scroll, in which Fu Jian 苻堅 (337–385), the Emperor of the Former Qin, learns of the statue’s arrival in Kucha. Enkōan reproduces Motonobu’s painting composition with remarkable fidelity, not only replicating the careful placement of clouds, palatial architecture, and the postures of figures in the scene, but also reproducing the coloring of the original scroll. Even the calligraphy is fully legible, its placement of characters and writing style skillfully adapting the brushwork of the original scrolls to Enkōan’s own distinctive, amateurish style (Figure 20).29 Not strictly concerned with the accurate reproduction of exhibited objects, however, Enkōan’s focus on the display context leads him to partially obstruct a large portion of the open scrolls with other objects, placing a woman and child just beneath the image of Fu Jian. Viewing the painting in rapt attention, the woman’s left hand rises loosely toward the scroll as if trying to mentally connect the narrative of the text she has just read with the exotic image before her eyes.

Figure 20.

Calligraphy from Origin Tale of the Shaka Hall, scroll 4 (Left) and detail of Figure 16 (Right). Calligraphy reproduced from (Nara National Museum 1975, p. 291).

This densely filled scene is framed both by the architecture of the temple space and by a spatially ambiguous curtain that extends across the upper quarter of the scene, over which Enkōan has inscribed cascades of text. Black beams ornamented in auspicious, multi-colored lotus petals frame the outer edge of the right page and cut across the center of the composition just above the paintings of the Buddha and arhats, creating a rectilinear space that fills the bottom three-quarters of a composition densely packed with figures, images, and texts. These beams also serve as supports for the edges of the curtain that appear to be fully drawn back to reveal the exhibition space to the seated audience on one conceptual register and the entire image space to the viewer on another, the whole scene itself transforming into a kind of kaichō, a “curtain opening”.

Enkōan’s complex image reveals multiple hierarchies of interest. As expected from the theme of the ehon, the arrangement of the exhibition space prioritizes the most sacred and culturally significant works from Seiryōji’s collection. Kano Motonobu’s painting of the Seiryōji Shaka is placed in the center, flanked by six hanging scrolls from the temple’s series of Sixteen Arhats. These elements and the central painting’s golden curtain pull the viewer’s focus to the painted Buddha image. Its vivid coloration, in contrast to the black and white arhat paintings and the black robes of the monk, highlights the Buddha’s preeminent position within the composition. At first glance, one might mistake this painting of the Buddha itself for the object of the assembly’s attention, as though a crowd of worshippers sat enraptured by the living Buddha’s sermon. Likewise, the emaki unrolls to almost the full width of the left page, reflecting its cultural importance as an illustrated work by Motonobu and its historical significance as the definitive record of the Seiryōji Shaka’s engi.

The relative importance of these treasures suggested by their placement within the actual space of the exhibition, however, is subverted by Enkōan’s use of text. In fact, the text in the upper register devotes minimal attention to these artworks. Only three lines are devoted to the central Buddha image, two to the arhats, and seven to the emaki. Instead, fifty-two lines, roughly three-quarters of the text, are related to the small, round object held in the hands of the priest (Figure 21). As the text explains at length, this object, described as “this temple’s number one sacred treasure” (tōji dai’ichi no reihō 当寺第一の霊宝) ushi no kawa no keman 牛の皮の華鬘, or cow-skin garland,30 was once owned by the retired emperor Go-Horikawa 後堀河 (r. 1221–1232). According to legend, Go-Horikawa’s mother Fujiwara Chinshi 藤原陳子 (1173–1238) died while he was still young, after which the prince piously performed memorial offerings on her behalf before various sacred images (reibutsu 霊仏). After performing a ceremony before the Seiryōji Shaka, the prince had a vision in which the Buddha told him that his mother had fallen into hell for her sins, but because of merit accrued through her son’s filial acts, she would escape hell through rebirth as a cow. Saddened by his mother’s still deplorable fate, he continued to worship the Buddha until one day he received another oracle from the Buddha who told him the location of the cow that his mother was reborn as. The Buddha instructed the prince that once the cow died, he should skin a portion of her hide to make it into a keman to be hung before the image of the Buddha. The cow did eventually die and, following the Buddha’s directions, the son made a cow-skin garland and hung it before the Buddha. As a result of his actions, the prince received a final oracle informing him that his mother had been reborn in the Pure Land.31

Figure 21.

Detail of Figure 19.

Considering the direct relation between textual content and the objects visualized in the image, there appears to be an uneven balance, with a disproportionate amount of text devoted to a single object that is only slightly visible. However, the majority of the activity within the image related to the spectators is clearly directed toward the garland, with almost every figure gazing directly at the priest and the object. In other words, three-quarters of the text that fills the top of the image functions to elucidate the story of the garland that is driving the central action of the scene. Therefore, by taking into consideration the action of the figures in the image, the amount of text devoted to the garland is not out of sync with the image’s primary point of active visual interest. The use of text in the upper register shifts the focal weight of the composition from the objects displayed on the page to the interactions between the gathered visitors and the vocalized/textualized explanation of the priest.

Once again, like the images of etoki and finger-pointers from Sennyūji kaichō, the text of the upper register switches from a non-diegetic function (explanation of the objects on display for the sake of the reader) to a diegetic function in which the text matches what is being spoken by the priest and heard by the audience. Framed by the raised curtain, it also highlights the multiple layers of communication that text performs within the image. The pulled-back curtain situates the ehon reader as both part of the crowd and as a spectator whose distance allows the reader/viewer to take in and be a part of the spectacle of the scene.32

In this richly layered composition, the subtle shifting of focus from the major highlights of the exhibition he is documenting—Seiryōji’s most sacred treasures—to the actions of the human figures who occupy the space and engage with inscribed text through active and passive modes of speaking and listening function to illustrate Enkōan’s primary artistic motivations. These lie not in the mere documentation of the kaichō event but in simulating the experience of the event through his observations on spectatorship itself, a thematic interest found throughout Enkōan’s corpus. By repeatedly shifting subject positions through a continuous conflation of diegetic and non-diegetic text, and through the layering of multiple strata of reading and viewing, the reader of the ehon continually fluctuates between an external and internal participant. Rather than simply “telling” or “showing” the reader what it was like to attend the kaichō, his work allows the reader to participate virtually in the shared viewing experience that brings the kaichō to life on the page in a way that neither textual commentary nor images alone would be able to accomplish.

5. Conclusions

In this essay, I have argued that the careful manipulation of text and image seen in Enkōan’s Saga kaichō allowed the reader/viewer to achieve something approximating a virtual experience of entering the exhibition spaces and participating in the kaichō of the Seiryōji Shaka. Through complex layering of diegetic and non-diegetic use of text, and by continuously playing with the relation between text and image, Enkōan ruptures the boundaries between the inside and outside of the page, facilitating the reader’s ability to move through multiple shifting subject positions as the scenes unfold. He does so while also illustrating vibrant exhibition spaces that are rich in observational detail, seeming to capture both the subjective experience and the objective reality of the kaichō and its assemblage of historical artifacts. In conclusion, it is worth considering the degree to which we should interpret this and other examples of Enkōan’s records as an objective form of visual reportage. What does a close reading of Saga kaichō reveal about the kind of subject position that the author himself occupied as an observer and a designer?

The close attention to visual fidelity, the careful reproduction of details in the display objects, and the general immersive qualities of the work arguably lead the reader to overlook that Enkōan is also engaged in the construction of an elaborately choreographed mise-en-scène. While his illustrations are presented as snapshots of brief moments in time, recorded from the perspective of someone who moves among the crowds and experiences the event from the same perspective as the surrounding figures, his precise depictions of paintings and works of calligraphy betray the fact that the author must have had unique access to the objects and spaces of the kaichō. This is supported by occasional references in his diary to his meetings with priests at temples around Nagoya that hosted kaichō.

The highly ordered and choreographed character of his compositions is also reflected in the subjects selected for portrayal. Enkōan’s accounts of Nagoya-based kaichō appear distinct from the raucous sakariba culture of Edo’s Sensōji 浅草寺 and its popular kaichō (Hur 2000). While Saga kaichō does conclude with an illustration of vendors and popular snacks sold outside the grounds of the kaichō venue, there is little sense of the chaotic atmosphere that seems to have characterized similar events in Edo at a time when misemono spectacles and other forms of amusement culture were flourishing. Enkōan’s crowds move through the spaces calmly and orderly; they are well dressed, and none engage in any direct worship of Seiryōji’s sacred statue. In fact, while Motonobu’s painting of the Seiryōji Shaka occupies the center of the final interior scene, the only appearance of the actual statue occurs in one of the opening pages. This scene, which depicts priests ritually cleaning the image, is notably void of lay worshippers (Figure 22). Ritual, it would seem, is preserved for the ritualists, while the visitors in the exhibition spaces engage not in worship but in observation and edification.

Figure 22.

Priests ritually wash the unveiled body of the Seiryōji Shaka with fragrant water. Excerpted from Saga kaichō. By Enkōan. 1819. Nagoya City Museum. Reproduced from (Nagoya City Museum 2006, pp. 34–35).

Seemingly at odds with the atmosphere of Edo kaichō, there is perhaps little in Enkōan’s Saga kaichō that speaks to the more popular forms of lay Buddhism characteristic of the times. While many visitors to kaichō in the latter half of the Edo period were drawn by playful curiosity, these exhibitions also presented a rare opportunity to encounter a powerful Buddhist deity and to seek out tangible, immediate “this-worldly benefit” (genze riyaku 現世利益). The idea of genze riyaku was, much like kaichō itself, a perennial theme of lay Buddhist devotion throughout the early modern period, yet one that was viewed critically by Confucian intellectuals and the Tokugawa shogunate. As Hur has argued, the beliefs and practices of genze riyaku, like other popular modes of lay devotion, were thought to run counter to Confucian ethics. Not only did they represent a degenerate form of Buddhism, but they were “a stumbling block to rationalistic efforts to improve conditions in this world” (Hur 2000, p. 203).

As a samurai and one in a long line of retainers to the lords of Owari domain, Enkōan was himself a subject of the ruling Confucian social order, and questions of how to portray contemporary life were certainly guided by ideological considerations. This is demonstrated in Saga kaichō’s climactic interior scene, where the text and the action within the scene are designed to focus attention on the priest’s story of the cow-skin garland. Ostensibly a miracle tale that ascribes salvific powers to the Seiryōji Shaka, the story of a young Go-Horikawa performing memorial rites for his deceased mother should perhaps best be read as a tale of filial piety with clear Confucian overtones. In this sense, it may have called to mind for its readers the famous lectures on samurai values given by the Confucian scholar and Owari native Hosoi Heishū 細井平洲 (1728–1801), which would have been well known to Enkōan.33

Confucian morality and its goals of social order and harmony appear to permeate this work, suggesting that Enkōan not only sought to draw his readers into the world of the kaichō but, in doing so, to transform the popular Buddhist event into a kind of communal experience that aligned with the ideological values of the Owari lords. In contrast to the strong association of contemporary Edo kaichō with misemono spectacle and entertainment that catered to the capital’s large and diverse commoner class, the scenes rendered by Enkōan suggest that Nagoya-based exhibitions of religious images and sacred objects could be sites of order and edification, much like the more intellectual bussankai displays of natural and manmade products or what would later be seen in early Meiji-era expositions and fine art exhibitions. Whether read as faithful depictions of historical kaichō or as carefully crafted constructs shaped by samurai values, Enkōan’s illustrated books open a window onto the dynamic intersections of religion, popular entertainment, and visual culture in the evolving urban landscape of early modern Japan.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Images consulted for this article come from full-scale reproductions of Enkōan’s manuscripts published by Nagoya City Museum. The author relied in part on the transcriptions by Yamamoto Yūko 山本祐子. The title “Saga kaichō” alludes to Seiryōji’s location in the Saga district west of modern-day Kyoto. |

| 2 | In its narrow reading, the Japanese word engi is a doctrinal term that derives from the Buddhist concept of pratītyasaṃutpāda (dependent origination). In my use of the term, I borrow from the more fluid and expansive understanding of the term articulated by Heather Blair and Kawasaki Tsuyoshi 川崎剛志, who argue that the term came to take on a wide range of valences relating to the sacred origins of textual and visual materials. For an insightful discussion of this term and recent academic approaches to engi, see Blair and Kawasaki (2015). |

| 3 | It was not uncommon for some wealthy and influential merchants or other non-samurai to also carry swords in the late Edo period, suggesting that the sword-carrying figures in Enkōan’s work may represent a mix of samurai and commoner classes. Because samurai women would likely have required a male escort to attend this kind of public event, it is also possible to identify a range of classes among the female attendees. |

| 4 | A mid-Edo-period collection of family lineages preserved in Hōsa Bunko 蓬左文庫 in Nagoya records eight generations of the Kōriki family line, including notes on their ranks and stipends. Portions of this document are reproduced in Nagoya City Museum (1986), p. 11. On the ranks and stipends of samurai at this time, see Vaporis (2022). |

| 5 | The concept of hibutsu (“secret buddhas”) is discussed in Fowler (1991–1992) and Rambelli (2002). |

| 6 | This practice continues today, as periodic kaichō of icons and other sacred treasures remain an important source of income and attraction for temples throughout Japan. On the evolution of kaichō in the modern period, see Mitchell (2023). |

| 7 | Perhaps the earliest record of a degaichō is Fujiwara no Teika’s 藤原定家 (1162–1241) documentation of a 1235 display of a copy of the Zenkōji Amida 善光寺阿弥陀 in Kyoto. |

| 8 | For a brief discussion of kaichō as one precursor of early Meiji exhibitions and expositions, see Kornicki (1994) and Aso (2013), pp. 16–20. |

| 9 | Enkōan notes that the entry fee to attend a kaichō held in 1777 was roughly equivalent to the cost of two bowls of udon noodles. |

| 10 | According to Yuasa Takashi 湯浅隆, the increase in misemono over the course of the eighteenth century owed largely to what was in fact a general decline in the number of visitors (and donations) around this time. Misemono, in other words, played a major role in reviving the thriving culture of kaichō prior to Enkōan’s time. See Yuasa (1991), p. 186. The symbiotic connection between kaichō and the surrounding entertainments is suggested by the popularity of a form of parodic kaichō (odokekaichō 戯け開帳) that also began to flourish at this time. See Fukuhara (2005). |

| 11 | For a discussion of the modern reception of Japanese Buddhist sculpture and painting as works of art, see Rosenfield (1998). |

| 12 | Hiroku guzū shite kechien nasashime tamau 広く弘通して結縁なさしめ給ふ. The other two icons he notes are the Zenkōji Amida, which is a secret image and never worshiped directly, and the Inaba Yakushi 因幡薬師, which was never taken outside the grounds of its own temple in Kyoto. See Nagoya City Museum (2006), p. 67. |

| 13 | See the list of degaichō held in Owara compiled by Kitamura Gyōon 北村行遠 in Kitamura (1989), pp. 248–51. |

| 14 | The first Edo degaichō in 1700 was held to raise funds for the rebuilding of the temple’s Shaka Hall, which had burned down in 1637. |

| 15 | Kaichō held at Ryōgoku are discussed in Hiruma (1980) and Ambros (2004). |

| 16 | Members of the Sumitomo family were important patrons of Seiryōji who played major roles in funding and organizing degaichō for the statue. See the discussion of the 1801 degaichō in Umihara (2005), pp. 77–80. |

| 17 | Images of an illustrated woodblock-print variation of the statue’s engi composed for the 1770 kaichō at Ekōin are published in Yuasa (1996). |

| 18 | Records preserved in the Sumitomo Historical Archives in Kyoto, for example, indicate a large number of “medium” and “small”-size prints of the statue were prepared for the 1801 degaichō. Close to 60,000 copies of the small prints were pressed in advance, and extra paper and printing blocks were brought along in case the initial runs sold out during the exhibition. See Sanada (2016). |

| 19 | The copies of the Zenkōji Amida could perhaps also be argued to have a comparatively strong symbiosis, but as I will suggest below, emphases on travel and display seen in medieval versions of the Seiryōji icon’s engi make the connections more apparent. |

| 20 | Documents and other materials found inside the statue in 1954 have helped to clarify much of the background of the Seiryōji Shaka’s origins. See Henderson and Hurvitz (1956). |

| 21 | For a discussion of the statue’s travels and various textual accounts of its history, see Borengasser (2014). |

| 22 | Rumors of the statue and its auspicious origins began to circulate shortly after Chōnen’s arrived in Kyūshū 九州 in the seventh month of 986. When it eventually reached Kyoto early the following year, the statue was paraded with great fanfare to the palace of the Heian 平安 capital. Opposition from the Tendai 天台 Buddhist order on Mt. Hiei 比叡山, however, seems to have prevented Chōnen from establishing a cultic center for the worship of the icon, and it was not until after the priest’s death that the statue was eventually enshrined west of Kyoto in a Shaka Hall 釈迦堂 at Seikaji 棲霞寺, which would later become the temple Seiryōji. See Oku (2009), p. 60. |

| 23 | See Tsukamoto (1982), pp. 14–15. Records from the early Kamakura period (1185–1333) suggest that the statue was also accessed, worshiped, and copied by figures in the circle of Go-Shirakawa 後白河 (1129–1192), but the account of Hōjō Tokiyori’s visit appears to be the first to specifically describe the viewing of the image as a kaichō. |

| 24 | From its second degaichō onward, the Seiryōji Shaka was displayed at Ekōin, a temple famous for hosting kaichō. The decision to display the statue at Gokokuji on its first degaichō in Edo appears to have owed to the role played by Keishōin 桂昌院 (1627–1705) in facilitating Seiryōji’s first request to the shogunate. Keishōin was the mother of shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi 徳川綱吉 (1646–1709) and a well-known sponsor of Buddhist building projects, including Gokokuji. She was also the daughter of a wealthy textile merchant in Kyoto, so when Seiryōji’s head priest Gyokuchin 堯鎮 (?–?) petitioned the shogunate in 1698, Keishōin served as an important mediator between Seiryōji, the shogunate, and Gokokuji. |

| 25 | The author thanks Professor David Atherton for this observation. |

| 26 | The statue is identified here as “a sacred buddha [image] that manifested miraculously (ōgen) in the Buddha’s lifetime and is commonly referred to as [the image] transported across three countries (sangoku denrai)”. |

| 27 | According to this text, one of the halls also displayed objects from Sairenji’s collection, but Enkōan chose to only illustrate objects from Seiryōji. |

| 28 | Today this object is registered as an Important Cultural Property in the possession of Seiryōji Temple. |

| 29 | The label displayed beneath the scrolls attributes the calligraphy to Shōren’in-no-miya, Prince Son’ō 青蓮院宮尊応 (d. 1514), although there is no definitive evidence connecting the priest to the project, and the text’s presumed composition of 1515 falls one year after his death. Modern scholars have also attributed the calligraphy to Jōhōji Kōjo 定法寺公助 (1453–1538). |

| 30 | A keman is an ornamental garland placed before a Buddha image. In Japan, these are often made of lacquered wood or gilt bronze. |

| 31 | Over the course of the medieval period, the Seiryōji Shaka appears to have developed a significant cult following in part as an icon that had some relation to bonds between mothers and children. See recent discussion of the Noh play “Hyakuman” in Mori (2022). |

| 32 | Enkōan’s intentional fluctuation of the text between the outer world of the reader and the inner world of the image also appears to be hinted at by the subtle rupturing of the curtain’s border by the text in the final few lines of the left page, although this may also be interpreted as the author essentially running out of space. |

| 33 | See, for example, his 1783 sermon translated in Aoki and Dardess (1976). |

References

- Ambros, Barbara. 2004. The Display of Hidden Treasures: Zenkōji’s Kaichō at Ekōin in Edo. Asian Cultural Studies 30: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Amino, Yoshihiko 網野善彦. 1978. Muen, Kugai, Raku 無縁・公界・楽. Tokyo: Heibonsha. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, Michiko Y., and Margaret B. Dardess. 1976. The Popularization of Samurai Values. A Sermon by Hosoi Heishū. Monumenta Nipponica 31: 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aso, Noriko. 2013. Public Properties: Museums in Imperial Japan. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, Heather, and Tsuyoshi Kawasaki. 2015. Editors’ Introduction–Engi: Forging Accounts of Sacred Origins. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 42: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borengasser, Daniel. 2014. The Presence of the Buddha: Transmission of Sacred Authority and the Function of Ornament in Seiryōji’s Living Icon. Master’s thesis, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chino, Kaori 千野香織, and Kazuo Nishi 西和夫, eds. 1991. Fikushon toshite no kaiga: Bijutsushi no me kenchiku no me フィクションとしての絵画: 美術史の眼建築史の眼. Tokyo: Perikansha. [Google Scholar]

- Enkōan. 1962. Enkōan nikki 猿猴庵日記. In Nagoya Sōsho 名古屋叢書. Edited by Nagoya-shi Kyōiku Iinkai. Nagoya: Nagoya-shi Kyōiku Iinkai, vol. 17, pp. 115–276. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, Sherry. 1991–1992. Hibutsu: Secret Buddhist Images in Japan. Journal of Asian Culture 15: 137–59. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara, Toshio 福原敏男. 2005. Odokekaichō to engi kōshaku 戯け開帳と縁起講釈. In Jisha Engi no Bunkagaku 寺社縁起の文化学. Edited by Tsutsumi Kunihiko 堤邦彦 and Tokuda Kazuo 徳田和夫. Tokyo: Shinwasha, pp. 269–87. [Google Scholar]

- Goree, Robert. 2010. Fantasies of the Real: Meisho zue in Early Modern Japan. Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, New Haven, CO, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Harootunian, Harry D. 1991. Cultural Politics in Tokugawa Japan. In Undercurrents in the Floating World: Censorship and Japanese Prints. Edited by Sarah E. Thompson and Harry D. Harootunian. New York: Asia Society, pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, Gregory, and Leon Hurvitz. 1956. The Buddha of Seiryōji: New Finds and New Theory. Artibus Asiae 19: 4–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiruma, Hisashi 比留間尚. 1980. Edo no Kaichō 江戸の開帳. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, Nam-lin. 2000. Prayer and Play in Late Tokugawa Japan: Asakusa Sensōji and Edo Society. Cambridge: Harvard Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, Nam-lin. 2009. Invitation to the Secret Buddha of Zenkōji. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36: 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, Fumi 池田芙美, Ueno Tomome 上野友愛, and Uchida Takeshi 内田洸, eds. 2017. Kanō Motonobu: Tenka o osameta eshi: Roppongi kaikan 10-nen shūnen kinenten 狩野元信:天下を治めた絵師:六本木開館10周年記念展. Tokyo: Suntory Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, Gyōon 北村行遠. 1989. Kinsei Kaichō no Kenkyū 近世開帳の研究. Tokyo: Meichō Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Kornicki, Peter F. 1994. Public Display and Changing Values: Meiji Exhibitions and Their Precursors. Monumenta Nipponica 49: 171–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, Andrew L. 1985. The Carnival of Edo: Misemono Spectacles from Contemporary Accounts. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 45: 499–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, Dylan. 2017. Nagoya Gesaku and the Daisō Lending Library. Proceedings of the Association for Japanese Literary Studies 18: 108–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Matthew. 2023. Opening the Curtains on Popular Practice: Kaichō in the Meiji and Taisho Periods. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 50: 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakoshi, Naoto 宮腰直人. 2000. Chūsei emaki kenkyū josetsu—E no naka de yubi o sasu hitobito 中世絵巻研究序説―絵の中で指を指す人々. Rikkyō daigaku Nihon bungaku 84: 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Masahide 森雅秀. 2022. Seiryōji no sendan zuizō to nō ‘Hyakuman’ 清凉寺の栴檀瑞像と能「百万」. In Ajia Bukkyō Bijutsu Ronshū Higashi Ajia VII: Ajia no Naka no Nihon アジア仏教美術論集東アジアVII:アジアの中の日本. Edited by Miyaji Akira 宮治昭, Hida Romi 肥田路美 and Itakura Masaaki 板倉聖哲. Tokyo: Chūō Kōron Bijutsu Shuppan, pp. 585–614. [Google Scholar]

- Nagoya City Museum, ed. 1986. Enkōan to Sono Jidai: Owari Han no Egaita Nagoya 猿猴庵とその時代 ―尾張藩主の描いた名古屋. Nagoya: Nagoya City Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Nagoya City Museum, ed. 2002. Shin Higoya Bunko 新卑姑射文庫. Nagoya: Nagoya City Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Nagoya City Museum, ed. 2006. Sennyūji Reihō Haikenzu, Saga Reibutsu Kaichōshi 泉涌寺霊宝拝見図・嵯峨霊仏開帳志. Nagoya: Nagoya City Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Nagoya City Museum, ed. 2012. Ehon Agehibari 絵本上雲雀. Nagoya: Nagoya City Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Nara National Museum, ed. 1975. Shaji Engi e 社寺緣起絵. Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Oku, Takeo 奥健夫. 2009. Seiryōji Shaka Nyorai zō 清涼寺釈迦如来像. (Nihon no bijutsu 513). Tokyo: Shibundō. [Google Scholar]

- Rambelli, Fabio. 2002. Secret Buddhas: The Limits of Buddhist Representation. Monumenta Nipponica 57: 271–307. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield, John M. 1998. Japanese Buddhist Art: Alive in the Modern Age. In Buddhist Treasures from Nara. Edited by Michael R. Cunningham. Cleveland: The Cleveland Museum of Art, pp. 232–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sanada, Takamitsu 真田尊光. 2016. Kinsei Edo ni okeru Bukkyō bijutsu no juyō to denpa: Seiryōji-shiki Shaka Nyorai zō no Edo degaichō no eikyō o chūshin ni 近世江戸における仏教美術の受容と伝播ー清凉寺式釈迦如来像の江戸出開帳の影響を中心に. Kajima Bijutsu Zaidan Nenpō 鹿島美術財団年報 34: 213–23. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Yui. 2007. Temple as Museum, Buddha as Art: Hōryūji’s Kudara Kannon and its Great Treasure Repository. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 52: 128–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, Shunkō 塚本俊孝. 1982. Saga Shaka Butsu no Edo degaichō ni tsuite 嵯峨釈迦仏の江戸出開帳について. In Tokubetsuten Tenrankai: Shaka Shinkō to Seiryōji 特別展展覧会:釈迦信仰と清凉寺. Edited by Kyoto National Museum. Kyoto: Kyoto National Museum, pp. 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Umihara, Ryō 海原亮. 2005. Seiryōji Shaka no Edo degaichō to Sumitomo 嵯峨清凉寺釈尊の江戸出開帳と住友. Sumitomo Shiryōkanpō 住友史料館報 36: 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Vaporis, Constantine. 2022. The Samurai in Tokugawa Japan. In The Tokugawa World. Edited by Gary P. Leupp and De-min Tao. New York: Routledge, pp. 137–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa, Takashi 湯浅隆. 1991. Edo no kaichō ni okeru jūhasseiki kōhan no henka 江戸の開帳における十八世紀後半の変化. Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History 33: 171–91. [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa, Yoshiko 湯浅佳子. 1996. ‘Saga Shaka Nyorai kaichō’ ni tsuite 『嵯峨釈迦如来開帳』について. Sō: Kusa Zōshi Honkoku to Kenkyū 叢: 草双紙の翻刻と研究 18: 81–98. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).