Abstract

Late contact-era depictions of inter-group conflict in southern African rock art include references to the image-makers and their opponents, who must also have been able to view the images. Performance theory allows researchers to go beyond the conventional question about who made the images by also addressing for whom the images were made. This case study uses performance theory to explore several details of the well-known conflict scene at Ventershoek (Jammerberg, Free State Province, South Africa). In it, ‘San hunter-gatherers’ appear to contest the possession of cattle, traditionally the property of ‘Bantu agro-pastoralists’. It is argued that, in addition to depicting conflict, the image-makers painted allusions to their ritualised, spirit-world mediation of conflict, their opponent’s use of protective war medicine and, potentially, lateralised symbols of cattle ownership that would have been comprehensible to audiences on both sides. It is argued further, from performance theory and the painted details, that the Ventershoek conflict scene contributed to the image-makers’ social construction of reality concerning their relationships with other groups.

1. Introduction

Southern Africa is one of the world’s richest rock art regions. It is rich not only because of its abundant painted and engraved hunter-gatherer rock art sites,1 but also because of the wealth of historical and ethnographic sources that allow fine-grained studies of the detailed imagery (e.g., Vinnicombe 1976; Lewis-Williams 1977, 1981; Deacon 1998; Parkington 2002, 2003a; Eastwood and Eastwood 2006). It is not the case, however, that productive research inevitably follows from this wealth of resources. For many decades, progress in rock research was crippled, as in so many other parts of the world, by the imposition of Western art concepts onto other image-making societies (Vinnicombe 1972a, 1972b; Lewis-Williams 1974).

Today, it is understood that hunting and gathering populations produced much of southern Africa’s Holocene rock art imagery. That imagery constitutes a corpus that shares, across thousands of years and kilometres, demonstrable social and cultural continuities in beliefs and practices, notwithstanding discontinuities in adaptations by their makers to regionally varied environments. Indeed, as the Zimbabwean archaeologist Peter Garlake put it, despite discernible variability, the long-lived southern African hunter–gatherer rock art tradition is consistent enough within itself to be considered a distinct group (Garlake 2001, p. 638). Colonial-era rock art developed from this older tradition (e.g., Campbell 1986, 1987; Hall 1994, p. 72; Blundell 2004, 2021; Challis 2008, 2009; Challis and Sinclair-Thomson 2022).

In South Africa and Lesotho, the most obvious changes to the fine-line, brush-painted hunter-gatherer corpus occurred in the late Holocene, some centuries after African herders (Khoe-speakers originating in eastern Africa) and agro-pastoralists (speakers of Bantu languages originating in the central parts of Africa) had moved into southernmost Africa along different routes and initiated an era of precolonial contact with local hunting and gathering societies (e.g., Mitchell and Whitelaw 2005; for a recent overview chapter, see Mitchell 2024). The southern African human population changed even more drastically and dramatically from the second half of the 1400s when Europeans began to take an interest in exploiting the land and its people (e.g., Wilson and Thompson 1982; Hamilton et al. 2010).

The southern African context has been the focus of research concerned with visible changes to contact-era rock art. Without drawing on performance theory, as I do here, numerous interactionist studies have identified instances in which culturally specific changes to rock paintings occurred (e.g., Battiss 1948; Manhire et al. 1986; Jolly 1994, 1995, 1996a, 2007, 2014; Ouzman and Loubser 2000; Eastwood 2003; Hall and Mazel 2005; Ouzman 2005; Eastwood and Eastwood 2006; Challis 2008, 2009, 2012, 2014, 2016; Hollmann 2015; Challis and Sinclair-Thomson 2022). The southern African context thus lends itself to a consideration of what happens to image-making practices when two or more different audiences confront one another.

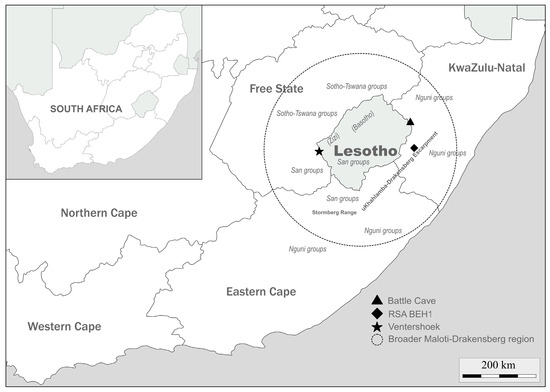

In this paper, I revisit the well-known conflict scene at Ventershoek (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3) to consider from the perspective of performance theory whether the scene, estimated to have been painted late in the contact period probably before the second decade of the nineteenth century (Le Quellec et al. 2015, pp. 99–100), had the potential to have been made for, or at least seen by, more than one audience. Before coming to that example, I situate my enquiry by briefly summarising the anthropologically informed explanation of the San practice of image-making, outlining performance theory and giving an example of how performance theory helps to explain contact-era changes in South African rock paintings. The paper concludes with a discussion of the purpose of image-making in the contact era.

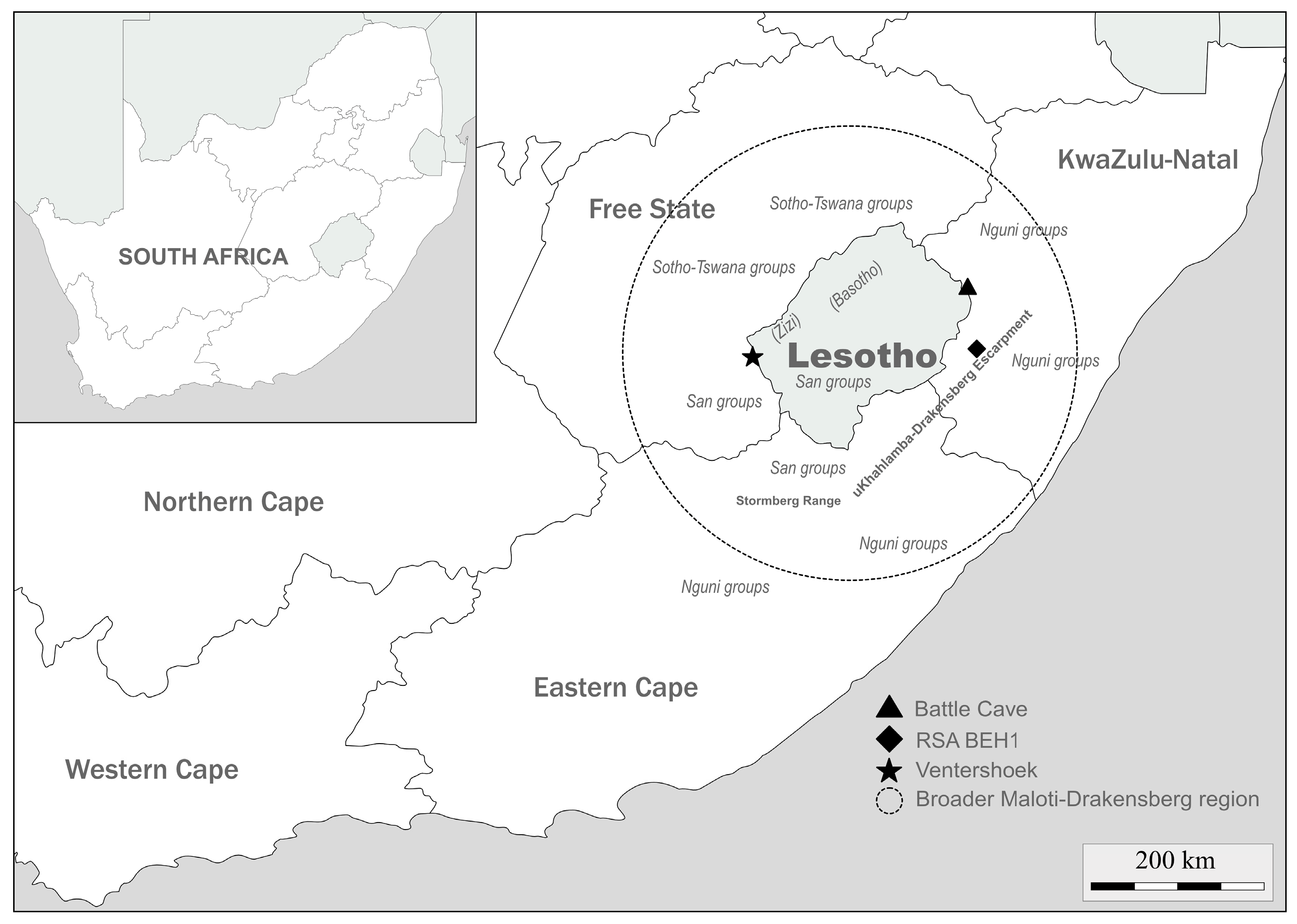

Figure 1.

A general and composite map showing the locations of places and groups mentioned in the text. Image by the author.

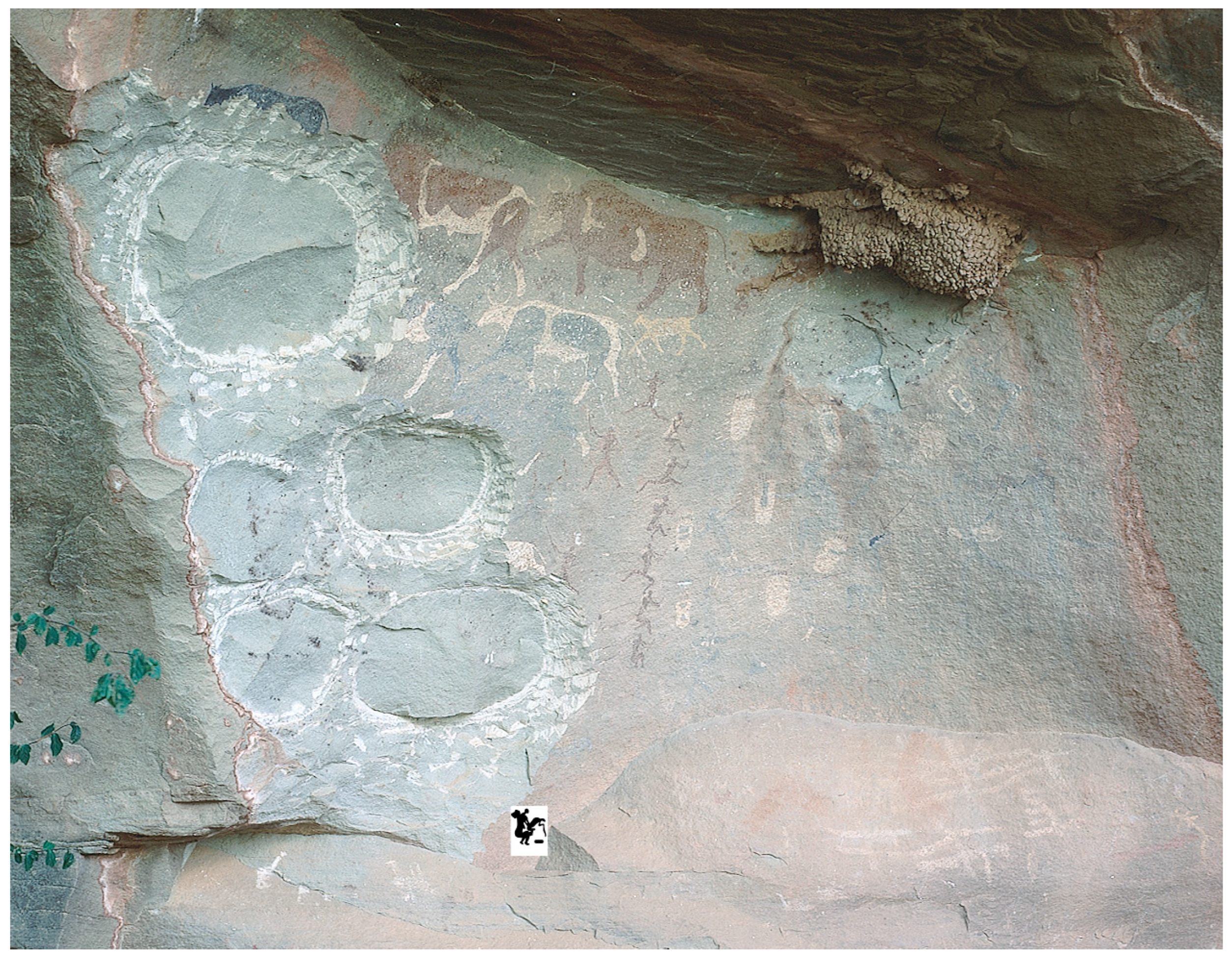

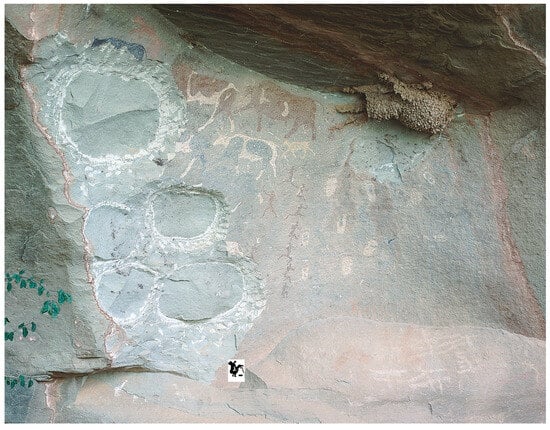

Figure 2.

The remains of the conflict panel at the Ventershoek rock art site with an inset showing a pair of figures discussed later. © Rock Art Research Institute and the African Rock Art Digital Archive (www.sarada.co.za).

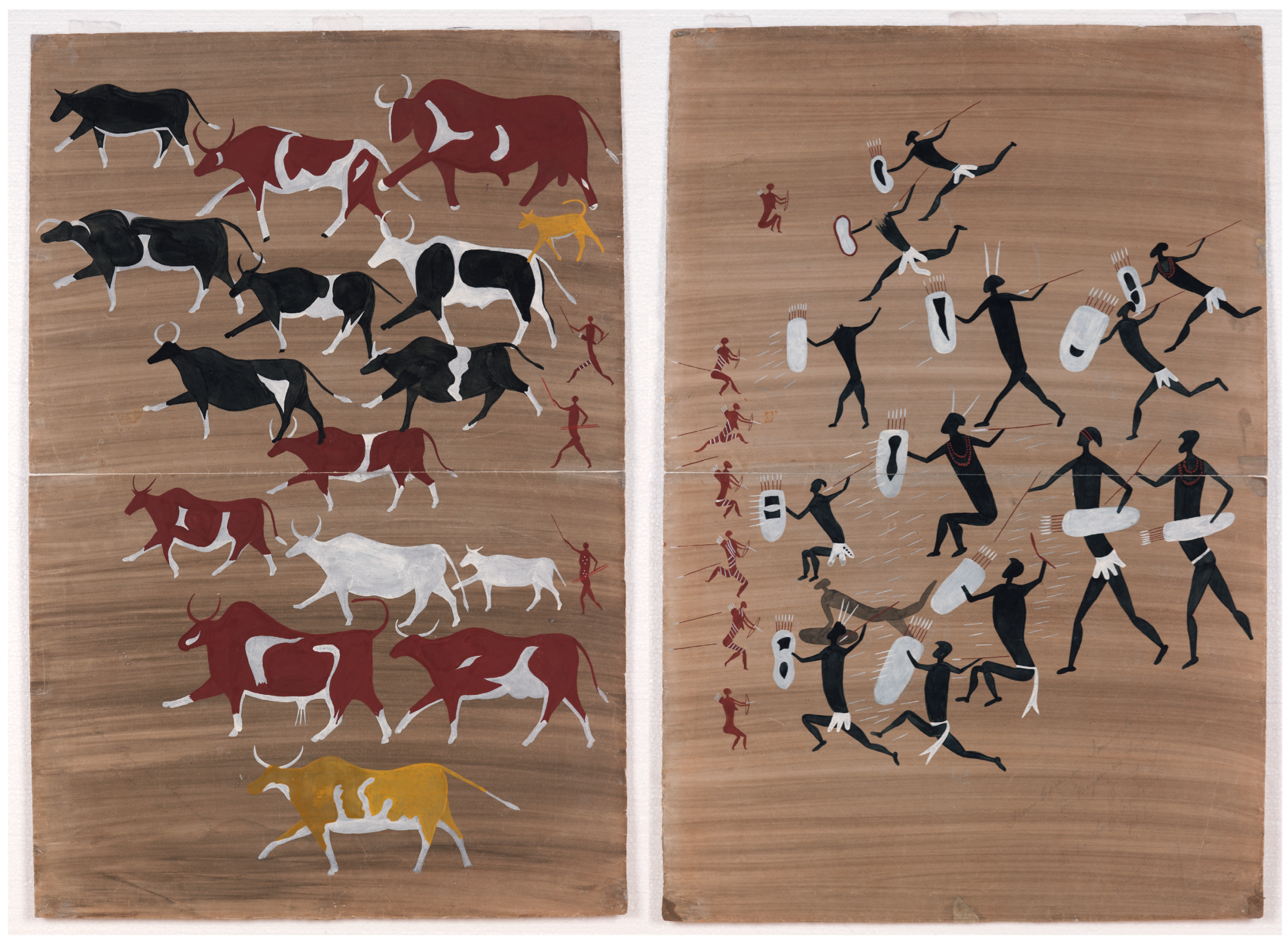

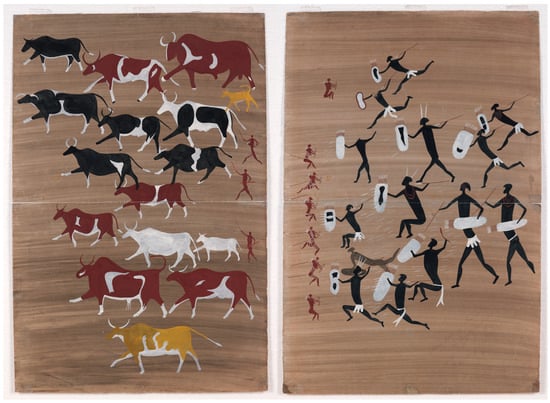

Figure 3.

Stow copied this conflict scene in 1877 before the removals visible in Figure 2 were made. The date is given in a handwritten note in the bottom right corner. © Iziko Museums of South Africa.

2. An Explanation of San Hunter-Gatherer Image-Making

The empirical evidence at our disposal—the most informative of which are ethnographic sources including verbatim San-language testimonies, detailed rock art images and the mutually illuminating relationship between them that arises from the historical, cultural, linguistic and genetic connections between southern Africa’s past hunter-gatherers and present Indigenous populations—shows that San image-making was a fundamentally social practice intimately interwoven with many other aspects of San life (e.g., Lewis-Williams 1977, 1981, 1982, 2019; Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2004; Lewis-Williams and Challis 2011; Lewis-Williams et al. 2021, pp. 35–37). It was not a naïve representational add-on to daily life.

What is today the generally accepted view of the region’s hunter-gatherer rock art has, for almost half a century, taken into account how the image-makers themselves thought and spoke about their own world, its realms and the beings and entities within them (e.g., Lewis-Williams et al. 2021, p. 52 note 1; Whitley et al. 2020; Whitley 2021). It has drawn on San ethnographies and anthropological theory to persistently challenge Western preconceptions of art (e.g., Vinnicombe 1972a, 1972b; Lewis-Williams 1977, 1981, 1989). In the southern African context, researchers’ use of San ethnographies and anthropological theory is frequently described as an ‘ethnographic turn’, but, because it was anthropology that provided the keys for researchers to understand the (by then existing) ethnographic and documentary sources, I prefer to call it, more inclusively, the anthropological turn.

Briefly, the anthropologically and ethnographically informed view of San rock art recognises that the images primarily concern mediation between beings in interconnected realms: one inhabited by living humans and animals and realms above and below that are inhabited by spirit beings (for overviews, see Garlake 2001; Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2004; Lewis-Williams and Challis 2011; Mguni 2015). In their roles as social and cosmological mediators, ‘owners of potency’ (see below) intervene and mediate with the spirits and the spirit world on behalf of their living, human communities (Lewis-Williams 1977, 1981, 1994, 1995, 2001). These persons, both male and female, also mediate frequently with animals (for overviews, see Lewis-Williams 1977, 1981; McGranaghan and Challis 2016; Guenther 1999, 2020, see also Parkington 2003b). The process of intervention implicates elements of what has aptly been called ‘ontological flux’ (the spectrum of changeable ontological states that transcends different realms) that affects many of the qualities of and connections between various beings in the San cosmos, not the least of which is somatic transformation (Guenther 1999, 2015, 2020).

The movement of San mediators between realms and the incontrovertible fact that they enter altered states of consciousness (ASC) to do so (Marshall 1969; Katz 1982; Biesele 1993, p. 202; Guenther 1999) has led to the translation of San words, such as the ǀXam !gi:xa (one who is full, -xa, of potency, !gi:-, Bleek 1956, pp. 255, 382) or the Juǀ’hoan nǀomkxàò (one who ‘owns’ or is a master, kxàò, of potency, nǀom, Dickens 1994, pp. 112, 241), as ‘shaman’ (e.g., Lewis-Williams 2019, pp. 33–34). In the southern African context, ‘shaman’ and ‘shamanism’ are best-fit translations of Indigenous words and concepts that are foreign to Western thought, but, being integral to San society and culture, those words and concepts have come to pervade the voluminous ethnography and descriptions of the abundant rock art imagery (see, for example, Lee 1967, 1968, 1979, [1986] 2013; Lewis-Williams 1977, 1981; Katz 1982; Biesele 1993; Marshall 1999; Guenther 1999; Garlake 2001; Hewitt [1986] 2008; Mguni 2015). Here, I use ‘owners of potency’ as an English-language translation that is explicitly in keeping with the Indigenous idiom.

The interventions of owners of potency concern many interrelated aspects of San life (Lewis-Williams 1977, 1981, 1982, 1994, 1995, 2001; Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2004; Hewitt [1986] 2008; Lewis-Williams and Challis 2011). Further, and contrary to an earlier, less well-evidenced view, the image-makers appear to have been, at least principally, a type of owner of potency (Lewis-Williams 1994, 1995, 2001). Without attempting an exhaustive list, their rock art is demonstrably concerned with the following:

- Avenues by which owners of potency routinely approach contact with and interventions via the spirit world (chiefly communal healing or trance dances and dreams, and also in more solitary circumstances).

- The travel, experiences and activities of owners of potency within and between realms.

- The performance of specific tasks by owners of potency (such as healing, rainmaking and game-animal control) for their communities.

- The management by owners of potency of human relationships with the rain and rain-beings.

- The specialist handling by owners of potency of dangerous levels of supernatural potency in circumstances such as a girl’s first menstruation.

- The human management of relationships with animals and spirit beings in circumstances such as hunting.

- The social mediation of human relationships by owners of potency.

Decades of research have therefore shown that San rock art overwhelmingly evidences owners of potency’s socio-cosmological mediation and intervention on behalf of their communities. It is this view of San rock art that is most widely accepted by archaeologists (Lewis-Williams et al. 2021, p. 52, note 1), including rock art scholars (for discussions that contrast different perspectives, see inter alia Vinnicombe 1972a, 1972b; Lewis-Williams 1974; Dowson and Lewis-Williams 1994; Parkington 2003b; Solomon 2008 and comments and reply; Le Quellec et al. 2015; Le Quellec 2018; Solomon 2018; Witelson 2023, 45ff).

3. Performance Theory

If, as I have argued elsewhere (Witelson 2019, 2023), southern African hunter-gatherer rock art was performed, then it is necessary to consider on a case-by-case basis the performance context and the participants as far as is possible to do so given that it is not possible to observe past performances (Witelson 2023, p. 35). Performance theory, however, provides a powerful means to investigate such performances.

Briefly, ‘performance theory’ (the body of ideas and principles used in the field of performance studies) concerns a field of scholarship that defines, analyses and explores the spectrum of different kinds of performances that pervade human lives (e.g., Goffman 1956; Bial and Brady 2016)—except where there is no conceivable audience–performer interaction. By definition,

a performance is an activity done by an individual or group in the presence of and for another individual or group. … Even where [physical] audiences do not exist as such—some happenings, rituals, and play—the function of the audience persists: part of the performing group watches—is meant to watch—other parts of the performing group; or, as in some rituals, the implied audience is God, or some transcendent Other(s).(Schechner 1988, 29 note 10)

Performance theory thus allows us to concentrate on the dynamic, changeable and contingent interaction between parties identifiable as ‘the audience’ or ‘the performers’.

Performances, especially ritualised and cultural ones, share at least seven features:

- Restored behaviour or a culturally specific but not invariable pool of performable behaviours and references (Schechner 1985, pp. 35, 111–12).

- Performers who display specific skills or culturally coded patterns of behaviour to or for observers or other audience (Carlson 2018, p. 4).

- An assessment by observers or the audience of the performed displays (Carlson 2018, p. 5).

- Performativity or the variability in the way performers display their skills or behaviours and interact with the audience on a particular occasion (Schieffelin 1998, p. 198).

- The accomplishment of a particular end via the performance (Schieffelin 1998, p. 198);

- A risk that observers or audience may deem a performer’s display to be a failure (Schieffelin 1996).

- The social construction of reality via the contingent, dialogic and participatory audience–performer interaction (Schieffelin 1998, pp. 204–5).

The terms ‘performer’ and ‘audience’ and the relationship between them must be translated according to culturally specific instances (Schechner 2013, pp. 2–3). The same cultural specificity also applies when determining whether something is, by definition, a performance or whether it might, for the sake of argument, be treated ‘as if’ it were a performance (Schechner 2013, pp. 38–40).

Elsewhere, I have argued that the now-extinct southern African hunter-gatherer rock art practice meets Schechner’s definition of performance (Witelson 2023, p. 44). Image-makers displayed their mastery of both technical and culturally specific skills for other members of their community (or members of other communities) who must have assessed the making and display of rock art images and other skills in terms of what the performers set out to accomplish by making images. What few documentary sources there are that were compiled contemporarily with San image-making support this conclusion (Witelson 2023, 35ff).

Furthermore, we can draw on the seven shared features of performances to make informed theoretical generalisations about past performances and engage with specific observations of the details of the material residues of those past performances—the images themselves and their settings. The extinct practice of San image-making was demonstrably akin to other ethnographically observed and recorded performances across San expressive culture (Witelson 2023, 15ff), and, because of the multiple cross-references in those performances to the content employed in different performance contexts, image-making must have been an integral part of the latticework of interrelated performances that constituted society itself (Witelson 2023, 145ff).

4. Changing Audiences for Image-Making Performances

Our archaeological understanding of changes to southern African hunter-gatherer image-making practices in the contact era stands to benefit from a consideration of the making, viewing and use of rock art, not merely in terms of notional performance but rather using the specific principles and terminology of performance theory (Witelson 2019, 15ff; 2022a, 2023, 9ff). Performance theory allows us to address visible changes to southern African hunter-gatherer rock art in space and time, not merely in terms of when the changes occurred or in what context but specifically in terms of why those changes might have occurred. Treating any changes merely as inevitable consequences of cross-cultural engagements or the passage of time is not sufficient as an explanation of change in the rock art. Performance theory is helpful in this regard: it guides us to address specific instances and to ask, for example, which image-making performers strategically adapted their performances to which audiences and to what end?

4.1. Setting

At this point, it is illustrative to consider an example demonstrating the use of performance theory in the study of some South African rock art (Witelson 2023). By way of background to that example, which I summarise later in this section, cross-cultural interactions between autochthonous southern African hunter-gatherers, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, incoming herders and agro-pastoralists, played out gradually in several phases over the last 2000 years, with ever-increasing degrees of interaction that varied through time and across space (e.g., Mitchell and Whitelaw 2005).

The complexities of those cross-cultural interactions have for decades been a focus of anthropological and archaeological interest. For example, the ethnographically attested sharing ethos of ideologically egalitarian hunter-gatherers (Barnard 2017, 2019, p. 16) must in the past have been confronted by the hierarchical structure of land- and livestock-owning people, who respectfully deferred to their patrilineal ancestors and chiefs (Hammond-Tooke 1974a). Ever-expanding agricultural societies needed ever more grazing land for their expanding herds. This situation is among the reasons that cattle gradually became a part of southern African life, even for groups who had traditionally lived by hunting wild animals and gathering wild plant foods. As we shall see, contested cattle concerned more than food.

Relations between San hunter-gatherers and cattle-herding agro-pastoralists were not static: there were times of amicable interaction and times of conflict on varying scales (Stanford 1910; Blundell 2004; Challis 2008 inter alia; Jolly 2014). Although there is some general spatial patterning in where hunter-gatherer, herder and agro-pastoral populations lived (e.g., Maggs 1976; Loubser and Laurens 1994; Mitchell and Whitelaw 2005) and where they practised distinct image-making traditions (e.g., van Riet Lowe 1952; Willcox 1984; Maggs 1995, p. 133; Maggs 1998, p. 18; Smith and Ouzman 2004, p. 510; Eastwood and Eastwood 2006), different populations were increasingly not isolated from each other (e.g., Loubser and Laurens 1994; Mitchell and Whitelaw 2005). For example, and with reference to the context of the examples discussed in this paper, from about the fifteenth century, there was an agro-pastoral presence in the broader Maloti-Drakensberg region (interior South Africa and Lesotho), which had up to that time been occupied by hunter-gatherers (Mitchell and Whitelaw 2005; Mazel 2022, p. 193). At roughly the same time, the cultural ancestors of Tswana-speaking agro-pastoral communities to the north became culturally, materially and historically recognisable as such (Schapera 1953, p. 15; Wilson and Thompson 1982, p. 135; Loubser and Laurens 1994).

From around the sixteenth century and into the late nineteenth century, agro-pastoral speakers of Sotho-Tswana and Nguni Bantu languages moved closer to and in some cases into the Maloti-Drakensberg massif, the former predominantly in the northern parts and the latter predominantly but not exclusively to the east and south (Maggs 1976; Wright 1977; Loubser and Laurens 1994; Jolly 1996b; Mitchell and Whitelaw 2005). Their interactions with the San population (considered to have made most of the rock paintings) varied from amicable to hostile across quotidian and ritual spheres of life (e.g., Jolly 1996b; Loubser and Laurens 1994; Hollmann 2015). San groups came gradually to participate actively and in various ways in the economics and socio-politics of a world that was increasingly at odds with a traditional hunting and gathering mode of existence (e.g., Jolly 1996a, 1996b; Loubser and Laurens 1994; Blundell 2004). Thus, ‘[i]n spite of regional variations in response to the agro-pastoralist frontier, it is clear that virtually all San societies in the southern … Free State, southern [KwaZulu-] Natal and north-eastern [Eastern] Cape Province were transformed in one way or another by contact with agro-pastoralists’ (Loubser and Laurens 1994, p. 116).

By the late stages of the contact era, many San variously owned, kept, or looked after livestock and also participated in political alliances and organised raids (Wright 1971; Vinnicombe 1976; Jolly 1996b; Loubser and Laurens 1994). The mere possession of cattle is therefore not itself a reliable means to define ‘the Bantu-speaking agro-pastoralists’ relative to ‘the San-speaking hunter-gatherers’. Statements of this kind are imprecise because cultural, linguistic and social boundaries, and therefore economic and political ones too, were not rigid or necessarily aligned. Indeed, a time came when traditional ‘hunter-gatherers’ and ‘agro-pastoralists’ shared the same world (for a detailed colonial-era example, see King 2017; King and Challis 2017). ‘San’ participation in cattle-raiding, and related performances of image-making (Witelson 2023, 74ff), were means for traditionally hunter-gatherer communities to participate autonomously in a new world and its politics (e.g., Loubser and Laurens 1994, p. 118).

It is thought that, from about the seventeenth century, hunter-gatherers in the western part of the Maloti-Drakensberg region made images with contact-era subject matter (domestic ungulates, other peoples and their material culture) predominantly if not exclusively in their own territories rather than behind the frontiers of their advancing agro-pastoral neighbours (Loubser and Laurens 1994). Most of those images appear to have been made ‘only once the expanding frontier of agro-pastoralists reached its limits’ (Loubser and Laurens 1994, p. 116). It has therefore been argued from a San perspective that the making of rock art images regulated ‘changing relations within their own [San] society’ rather than, for example, ‘regulating San relations with their Sotho-Tswana neighbours’ (Loubser and Laurens 1994, p. 118). More generally, the cross-cultural engagements evidenced in the rock art, including those made in the colonial era, are considered to have participated to varying degrees in bi-directional symbiotic and culturally syncretic processes involving individuals from diverse groups and backgrounds (e.g., Jolly 1996a; Challis 2012; Sinclair-Thomson 2021; Challis and Sinclair-Thomson 2022).

Such ideas begin to address the extent to which the subject matter of putative ‘San hunter-gatherer’ rock art in the contact era reflects or was a product of cross-cultural engagements. Building on those considerations and the findings of the numerous interactionist studies cited above, I suggest that performance theory brings an especially relevant question into sharper focus: did the purpose(s) of ‘San’ image-making change in the contact era?

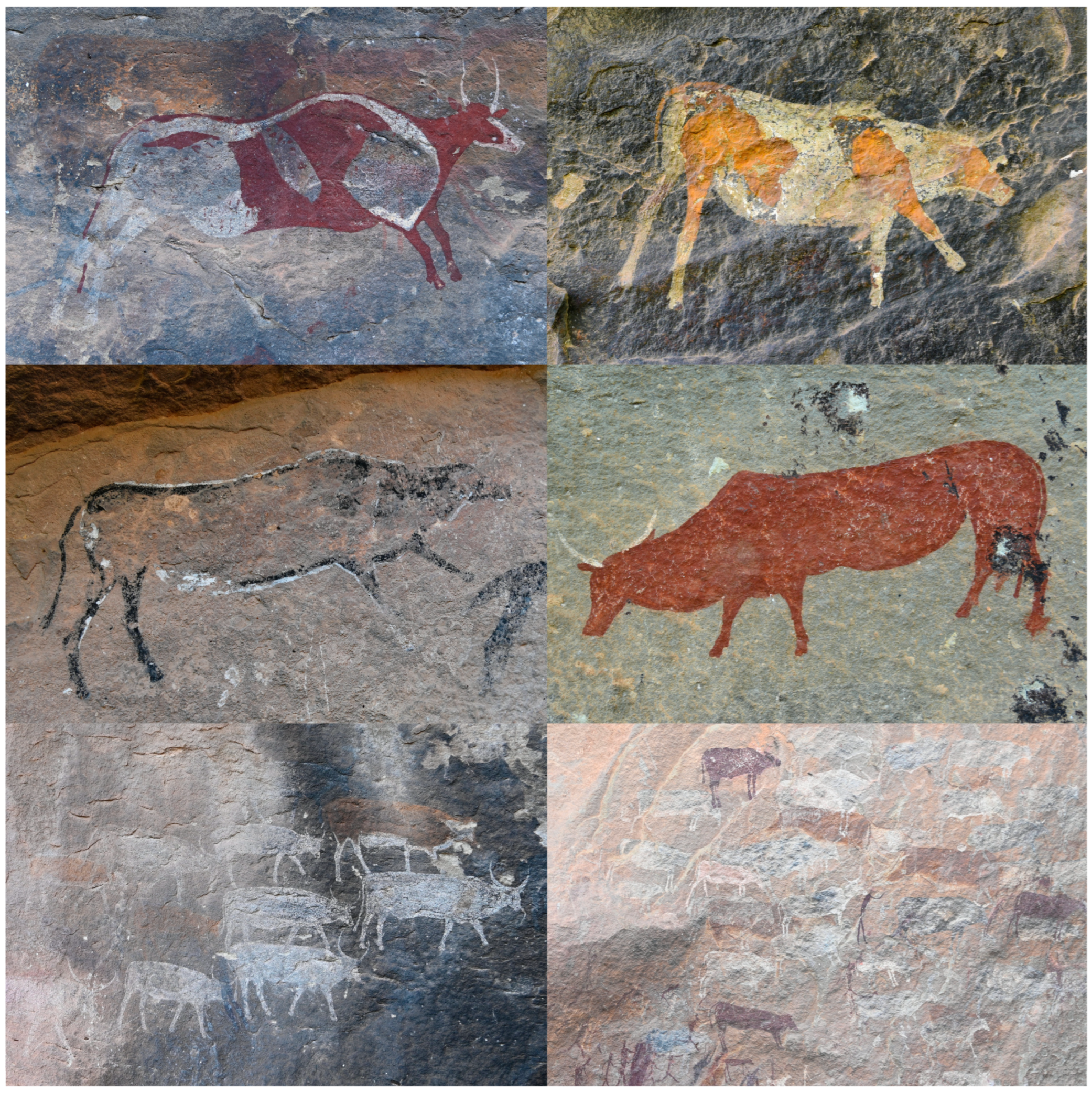

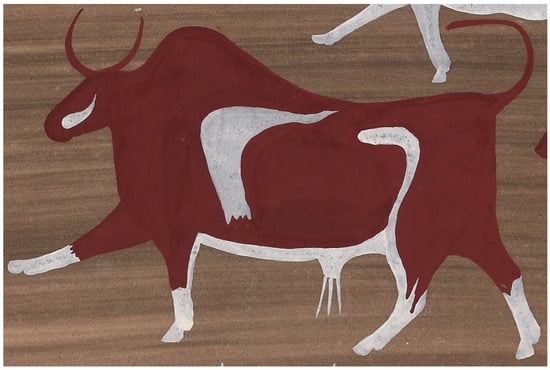

Researchers have long rejected the idea that hunter-gatherers depicted in their rock art the other people and domestic animals they had seen merely because they had observed them (e.g., Campbell 1986, 1987; Hall 1994, p. 72). Certainly, considering the art to be ‘mere depictions of observations’ does not sufficiently explain why, in addition to the new subject matter introduced into contact-era rock art, several other aspects of the rock art imagery also changed. Empirical changes through time and across space are evidenced in the broader Maloti-Drakensberg region by changes to painting techniques (by which is meant the shaded or modulated painting technique relative to the unshaded or unmodulated painting technique), paint recipes2 (including their binders and the advantages those afforded for particular painting techniques) and the paint colour palette (Witelson 2023, 87ff). I return to the purposes of image-making in the concluding discussion.

4.2. Changing Audiences

Across and around the Maloti-Drakensberg massif in South Africa and Lesotho, visible changes to the hunter-gatherer rock painting corpus occurred in a series of stages corresponding to increasing degrees of inter-group interaction through time (e.g., Battiss 1948; Pager 1971, 1973; Vinnicombe 1976; Loubser and Laurens 1994; Russell 2000; Swart 2004; Flett and Letley 2013; Challis and Sinclair-Thomson 2022; Witelson 2022b). Although the relative painted stratigraphic sequence varies even within the Maloti-Drakensberg region itself, a minimum of four phases (more phases exist) appear to have been relatively stable and widespread across the region (Witelson 2022b). From oldest to youngest, these are as follows:

- Shaded polychrome images (i.e., modulated with blended colours) of wild animals, especially eland antelope, and related human figures which are often monochromatic.

- Rare examples of domestic animals (fat-tailed sheep and cattle) painted in the shaded polychrome technique.

- Unshaded or hard-edged paintings (including ‘blocked’ paintings) of wild and domestic animals and related human figures made in bright, pure colours.

- Unshaded or hard-edged paintings depicting colonial-era subject matter.

The final stages of this sequence include additional rock arts (Witelson 2022b, p. 92).

Significantly, the sequence is not evidenced by changes in subject matter alone. The most noticeable shift is that away from (but not the total disappearance of) the making, on one hand, of polychrome images of wild animals and humans using paints apparently bound with oils or fats in which colours were often blended and modulated (apparently when wet) to, on the other hand, paints that appear to have been bound with animal proteins that were used to make unmodulated (unshaded) images of humans, wild animals and livestock in brighter, purer paint hues with clear boundaries between individual colours (Witelson 2022b, 2023, 57ff). Only in rare, transitional instances were images of new subjects like fat-tailed sheep and cattle painted in the older, shaded polychrome technique (Loubser 1993, p. 372; Loubser and Laurens 1994, p. 89; Witelson 2022b, pp. 79–84).

I argue that, in the Stormberg area of the Eastern Cape Province specifically, and more generally in the wider Maloti-Drakensberg massif, hunter-gatherer rock paintings changed visibly in response to the new needs and, especially, the expectations of new audiences in the contact era (Witelson 2023, 71ff). Contact and interaction between different groups gradually changed the broad-scale composition of the southern African human population, which until roughly 2000 years ago comprised exclusively hunting and gathering societies. Those hunter-gatherer societies were not themselves static or homogenous, but, even allowing for temporal, regional and cultural variations, they must have been more similar to each other than they were to African food-producing societies (Witelson 2023, pp. 72–75, 100–1). Although there was no singular changing point, prior to contact, it had never before been possible for agro-pastoralists to have been an intended or unintended audience for hunter-gatherer image-making performances. Changes to the audience must have necessitated and determined changes to the performances.

At the broadest societal level, the population of southern Africa had, from the earliest phases of cross-cultural interactions, diversified dramatically and gained a higher potential for further social diversification. If the broad-scale southern African population changed during the precolonial contact period and via instances of cross-cultural interaction, as indeed appears to have been the case, it follows that the number of potential audiences for existing or new hunter-gatherer performances (including rituals such as healing ceremonies, rainmaking, rites of passage and image-making documented in both ethnographic and archaeological contexts) must have increased (Witelson 2023, 71ff). What had previously sufficed for exclusively hunter-gatherer audiences was not necessarily suitable in areas of contact. Image-makers had to strategically adapt their performances, especially their image-making, to the new contingent circumstances created by the advent of cross-cultural interactions. Simultaneously, they now had a wider, cross-cultural pool of social references on which to draw and could decide how and whether to do so.

Even when cultural and socio-economic distinctions endured (e.g., Loubser and Laurens 1994, p. 99), changes to the audiences or compositions of audiences for hunter-gatherer performances must have precipitated potential performance adaptations for any audiences that would have had needs and expectations somewhat different from the customary and traditional hunter-gatherer audience (Witelson 2023, p. 69). Simultaneously, cross-cultural interactions must have given rise to new circumstances in which adapted or new performances played out across cultural, societal and linguistic boundaries.

What this example of changing audiences for Maloti-Drakensberg–region rock art performances demonstrates is that, although cross-cultural interactions are the well-known setting in which changes to the rock art occurred, it was strategic adaptions to image-making performances (involving the making, use and viewing of rock art) relative to changing audiences that was the mechanism by which those changes occurred, both on the scale of individual performances and on the scale of sustained repetitions of those and related performances through time.

The changes to image-making performances that resulted from the changes to the composition or expectations of the audiences for those performances are still more significant, I suggest, because they introduce the possibility that hunter-gatherer image-making concerned a wider range of matters in cross-cultural contexts than in exclusively hunter-gatherer settings. As I have suggested, the late contact era must have witnessed performances that played out across cultural, societal and linguistic boundaries that were purposefully adapted to new circumstances.

5. The Ventershoek Conflict Scene Revisited

Because cross-cultural interactions were the context in which changes to the appearance of hunter-gatherer rock paintings occurred, it is instructive to revisit a well-known example of a late contact-era depiction of conflict between two markedly differentiated sides at Ventershoek (2927CA1), a painted rock shelter and Provincial Heritage Site (https://sahris.org.za/node/41026, accessed on 18 April 2024) southeast of the Jammerberg in South Africa’s eastern Free State Province (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). It provides an opportunity to consider the minimum two implied audiences (endpoints in a continuum of social and cultural compositions) that could respond most immediately to the images and their having been made late in the contact era.

In previous decades, some researchers thought that rock art might literally illustrate San history and their dealings with agro-pastoral neighbours. Among the most well-known proponents of the idea that San rock art illustrated San history was the British geologist George William Stow, whose posthumously published tome, The Native Races of South Africa (Stow 1905), presented the argument that agro-pastoralist Bantu-speakers overwhelmed the Indigenous San population when they continually expanded their territories and grazing areas. It has since been pointed out, however, that Stow’s implicit colonial concern was the justification of White land ownership: in Stow’s view, South Africa’s Bantu-speaking population had recently invaded what was rightly San country. From that skewed perspective, Black South Africans were deemed to have no more legitimate claim to the country than did still more recent White South Africans (Dubow 2004, p. 129).

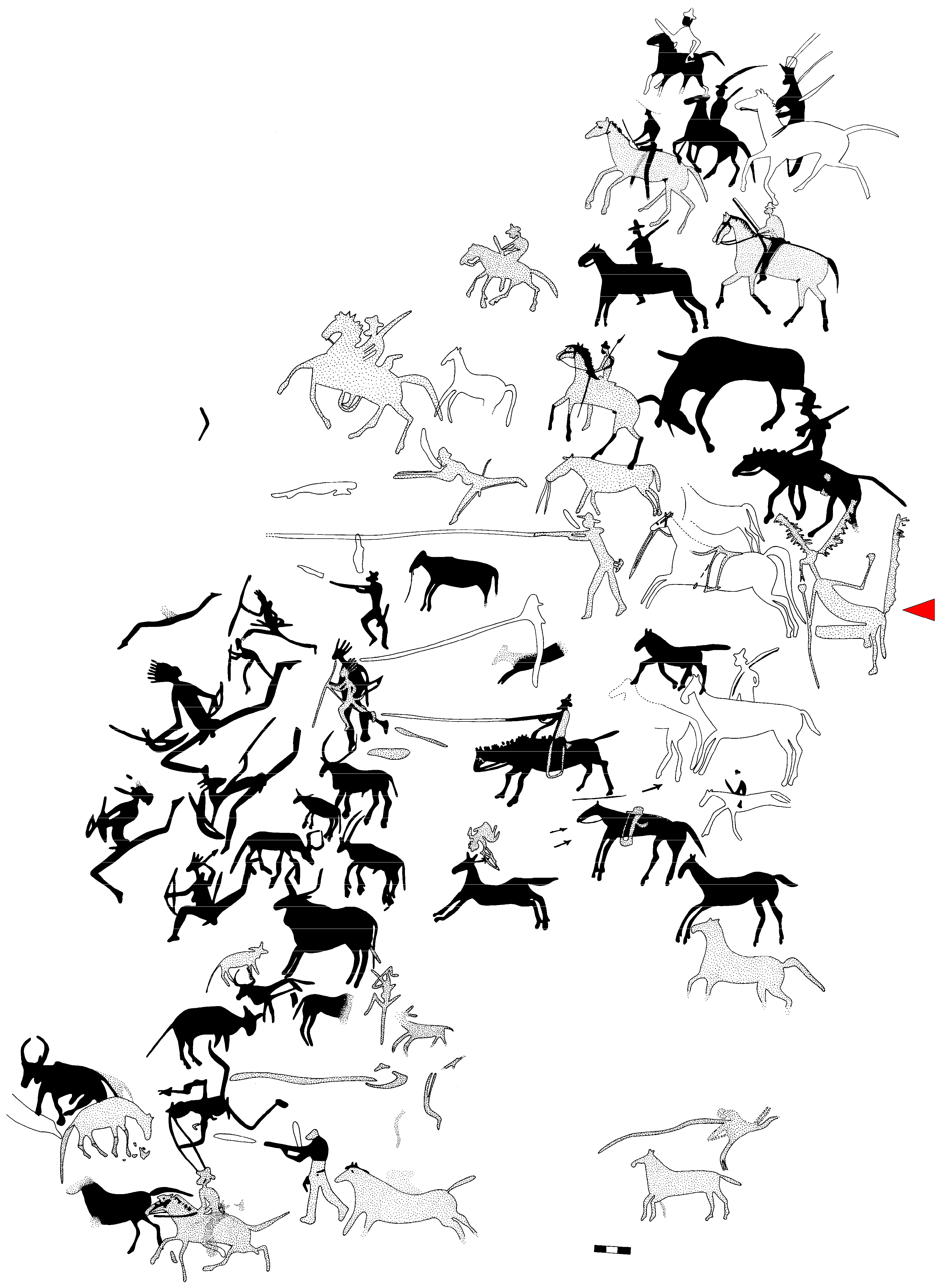

In 1877, Stow made the earliest known copy of the Ventershoek conflict scene (Figure 3). His copy shows a group of small red human figures with bows, arrows and a few spears facing off with a group of larger black figures with spears and most probably Nguni shields of a pre-1820 CE type (Stow and Bleek 1930, caption to plates 61, 62; Le Quellec et al. 2015, 96ff). The humans painted in black appear to chase after and fight with the red figures, some of whom drive cattle away with sticks. Group identities are clearly emphasised in this panel: the bodies and objects on each side are unambiguously different from the other. This is significant because identity itself is performed (Butler 1988, [1990] 1999; Clammer 2015), as are the boundaries between ‘us’ and ‘them’ (Hammond-Tooke 2000, p. 421).

One book compares numerous historical copies of the Ventershoek conflict scene and uses them along with photography to reconstruct the original panel (Le Quellec et al. 2015), which was necessary because the French missionary Frédéric Christol chiselled out pieces of the panel and sent them to European museums (Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 16, passim). The reconstructed panel and the comparison of the different historical copies are best and most easily viewed in that book, which the authors have made freely available on the Internet.3 The book, however, does not give the date of Stow’s original copy, which predates Christol’s by at least five years, and reproduces only the off-colour plates published in Dorothea Bleek’s Rock Paintings in South Africa (Stow and Bleek 1930, plates 61, 62).

The loss of painted details with Christol’s destruction of the panel and the low number of stratigraphic relationships between the painted images limit the comprehensiveness of any reconstruction and interpretation. Nevertheless, the conflict scene’s interpretation has a long history (Le Quellec et al. 2015). Generally, commentators have focused on what they, within a Western frame of reference, take to be its narrative dimension: are the red bowmen fighting off cattle-thieving black shield-bearers or vice versa? Although the panel presents a synthesised view of a battle, we cannot be certain that the image-makers held a linear notion of time. Given that the context of this open-ended panel was, in a sense, ongoing, we cannot be sure that the panel depicts a single event that had occurred rather than one that was yet to occur or failed to occur or, indeed, occurred outside of linear time. Performance theory allows us to go beyond the conventional concern with events and narratives: it opens a new avenue for inquiry by focusing on the process of image-making, use and viewing and by paying attention to the elements of and participants in that process.

In tandem with performance theory, a consideration of the sources of evidence on fundamental beliefs and rituals in San and Bantu-speaking societies provides us with a means to implicate particular audiences in specific rather than merely general terms. In doing so, I adopt the methodological principles of Ideational Cognitive Archaeology: they are the use of ethnography, a profound understanding of different types of analogies, attention to natural modelling and ethology, reconstructions of social life and the scientific assessment of competing hypotheses (Whitley 2024; see also Lewis-Williams 1977, 1981, 1989; Whitley et al. 2020; Wynn et al. 2024). These principles allow inferences about the past to be made using historical and ethnographic information.

Researchers who have commented on the well-known Ventershoek panel have not sufficiently addressed a number of what I take to be key points. In what remains of this section, I explicate specific elements of the Ventershoek conflict scene in terms of performance theory by thinking, via ethnographies, through the two implied audiences and with reference to relevant cattle ethology.

5.1. Thinking Through a San Audience

Within the San worldview, there are at least two aspects to conflict (e.g., Schapera 1930; Katz 1982; Barnard 1992, 2019; Marshall 1999; Guenther 1999; Lee [1986] 2013). First, literal, physical violence and battles involving weapons, such as men’s lethal poisoned arrows, are known to have occurred in the archaeological past (e.g., Pfeiffer et al. 1999; Morris 2012; Pfeiffer 2010, 2016) and to be the potential outcome of ethnographically recorded heated disagreements (e.g., Guenther 2014a, 2014b). Certainly, and especially in more recent times, ‘the harmless people’ were far from immune to violence (Thomas [1959] 1969, 2006; Draper 1978; Lee 1979).

Ideally, conflicts are pre-empted or resolved by other means (e.g., Marshall 1959, pp. 360–62; Shostak 1981, pp. 306–8, see also the summary discussion in Guenther 1999, pp. 36–38). Men who have fallen out with each other may be forced to cooperate at a healing dance, and neighbours entering someone else’s territory would ideally be engaged and treated as amicably as possible, even though that might not be what happens in practice. Twentieth-century Juǀ’hoan gift exchange practices involving fictive kinship ranged over hundreds of kilometres and crossed language boundaries (including Nharo) across the Kalahari Desert (Wiessner 1977, p. 203; 1982). There is evidence that materially similar long-distance trade occurred in the deep past elsewhere in southern Africa (Mitchell 1996, 2009; Stewart et al. 2020). Whatever their historical specificities, such networks established advantageous ties and connections between groups.

At least as far as rock art in the broader Maloti-Drakensberg region is concerned, images that might be construed as literal illustrations of specific conflicts between different hunting and gathering groups are not frequently depicted (e.g., Campbell 1986, 1987). In part, this is because the primary San setting for the resolution of societal conflict is mediation by healers or owners of potency between the immediate living community and the dead. At healing dances, owners of potency mediate on behalf of their communities with spirit beings, especially spirits of the departed and ‘god’ (Lee 1967, 1968, [1986] 2013; Marshall 1969, 1999; Katz 1982). In this conflictual context, healers fight with the spirits, drawing out from living humans the arrows of sickness shot into them. Conflict at this level concerns social ‘illness’ which frequently if not invariably comes into the immediate living human community from outside it (Lee 1967, pp. 36–37). It is ‘us’ versus ‘them’: the living human community and their recent kin against spirits and gods (Witelson 2023, 72ff). While recently deceased humans may aid or answer appeals from their living relatives, the spirits of the dead are generally antagonistic: healers have to negotiate with them and ‘god’ to be left in peace. Significantly for the focus of this paper, conflict is therefore resolved via ritualised mediation involving contact with the spirit world.

In San thought, physical death (that is, death outside of ritual healing contexts) is perceived as the irreversible severance of the tie between a body and its ‘wind’ or soul (e.g., Marshall 1999; Low 2007a; Thorp 2024). When humans die, they join the departed in the spirit world. Among the reasons that the dead send sickness to the living is that they long to be reunited with their living relatives (Lee [1986] 2013, pp. 142–43). From their position in the spirit world, departed owners of potency can still affect events and entities in the realm of living humans, such as the activities of game animals or the coming or going of rains (Lewis-Williams 1977, 1981; Hewitt [1986] 2008).

Significantly, it is the healers who ‘die’ via their entry into ASC and travel to the spirit world (Lee 1967, 1968; Marshall 1969; Katz 1982). Unlike ordinary people, they can then return from it—if the spirits have not decided to prevent their homeward journey. Moving between realms, and with the support of their community, the healers perform socio-cosmological mediation. Conflict is thus not limited to the visible or physical worlds, even if it is frequently experienced in that world.

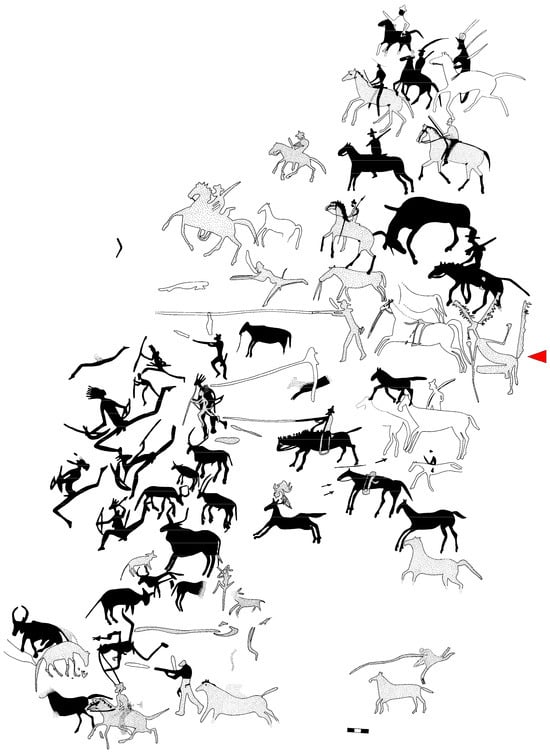

The well-known and eponymous scene at the publicly accessible Battle Cave rock art site in the Injisuthi Valley of the KwaZulu-Natal Drakensberg in South Africa (Figure 1 and Figure 4) exemplifies the spirit world as a setting for conflict resolution. At first glance, the scene appears to depict a battle between two human groups fighting each other with bows and arrows. Closer inspection reveals that the scene has a setting beyond ordinary visible reality (Campbell 1986, pp. 257–61; Lewis-Williams 2015, pp. 158–61).

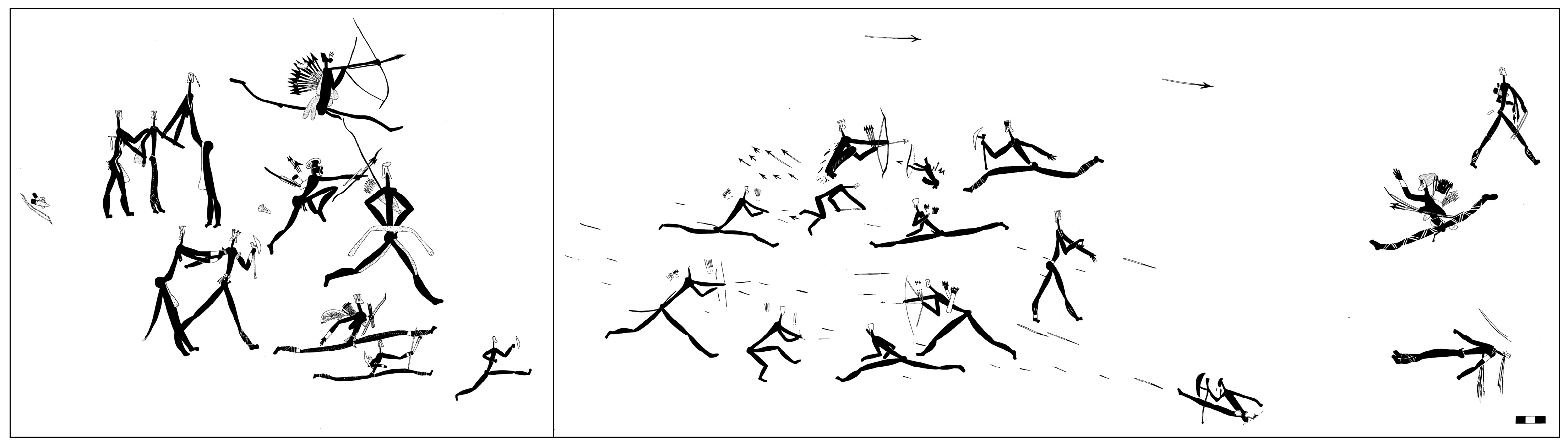

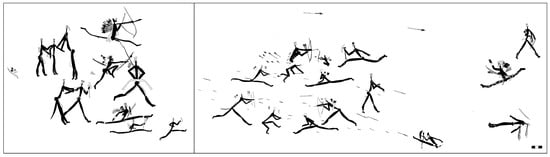

Figure 4.

Detail of two parts of the long fight scene at Battle Cave. Unpainted rock, indicated by the vertical line, has been omitted. Elements of the images reveal that the fight takes place in the spirit world. Note the comparable body ‘decoration’ of the red figures in Stow’s copy. Original image © Rock Art Research Institute and the African Rock Art Digital Archive (www.sarada.co.za).

The meanings of the painted details are understood from the combination of San ethnography and painted evidence at many rock art sites (Campbell 1986, pp. 257–61; Lewis-Williams 2015, pp. 158–61). The Battle Cave panel (Figure 4) contains several allusions to a conflict experienced in the setting of a communal healing dance:

- To one side are some women who support and ‘hold back’ or restrain some of the men heading into the conflict, just as women do when male healers or novices enter ASC at healing dances.

- One man points a finger whilst raising a knee, a posture associated with a healer’s ‘shooting’ or transfer of potency and the contraction of stomach muscles during trance dances.

- Some of the men carry unrealistic numbers of arrows.

- There are two figures with probable streams of sweat from under their arms and one horizontal figure who bleeds from his nose—both allusions to healing and entry into trance.

- Several combatants remove arrows from their arms, just as healers draw out ‘arrows’ of sickness from community members.

- There are several male figures with dots or dashes (one crouched figure has them along his spine) that are thought to allude to the supernatural potency of which owners of potency speak and which they use to travel to and return from the spirit world.

Although some of the figures are differentiated from the others by particular marks and patterns on their bodies, most of the human figures in the scene are depicted similarly in terms of their bodies and equipment. Even if the scene is taken to depict a fight between two distinct human groups, the painting is thought to show that the conflict is being resolved in or via the San spirit world (Campbell 1986, pp. 257–61; Lewis-Williams 2015, pp. 158–61).

5.2. Thinking Through a Bantu-Speaking Audience

The San perspective of conflict and death contrasts with similar concepts in Bantu-speaking cultures (Schapera 1937; Hammond-Tooke 1974a; Wilson and Thompson 1982). Without attempting a complete overview of cultural diversity even within southern African Bantu-speaking societies, sickness and misfortune arise from malign entities within one’s own community, rather than from outside of it as is the San case. Here, the ‘them’ that one is up against is, for example, a nameable person in the same village. Broadly speaking, witches and their animal familiars can bring curses to particular persons and their relatives, which a different kind of healer may then try to resolve. Departed humans take their place among venerated ancestors, who actively participate in the lives of living humans. Frequently, the ancestors are mediators who might, in the context of a dream, take the form of a particular animal and call that person to become a healer or witch doctor (e.g., Prins and Lewis 1992; Jolly 1996a).

At the larger scale of physical fights and battles, agonistic processes of group fission and fusion are frequent and constituting elements of traditional Bantu-speaking society (e.g., Schapera 1937; Hammond-Tooke 1974a; Peires 1981; Kopytoff 1987). Disagreements, for example, about property, territory or the political status of a chief’s sons, and the power wielded by the chief’s wives, may lead to a breakaway group with greater or lesser connections to the original group. A lesser son may, for example, be encouraged by his politically ambitious mother to become a powerful chief. Resulting conflicts about power, political alliances, grazing lands and herds involved shields, fighting sticks, spears of various kinds and war magic (Schapera 1937; Hammond-Tooke 1974a; Shaw and van Warmelo 1981). These processes were a staple of historical and ethnographically observed agro-pastoral societies in southern Africa. They witnessed new complexity in the colonial era.

Southern African archaeological and ethnographic evidence shows that cattle have long been at the centre of agro-pastoralist worlds (Kuper 1980; Huffman 1982, 1986). Crucially, the settlement layouts of Bantu-speaking societies, with their earlier ‘Iron Age’ origins, are argued from ethnohistorical evidence to have revolved around the symbolism and possession of cattle (Kuper 1980; Huffman 1982, 1986). Such settlement layouts, which often included a chief’s family, soldiers and subjects, are symbolically arranged around a central cattle kraal (corral) and the chief’s ancestors (Kuper 1980; Huffman 1982, 1986, see also Schapera 1937; Hammond-Tooke 1974a). Indeed, in southern African Bantu-speaking societies, cattle

loom largely in a man’s thoughts. They are his principal form of wealth, his most treasured possession; and anything concerning them and their welfare focuses his attention. The Bantu languages abound in terms minutely differentiating cattle according to sex, age, colour, and shape of horns, and reflecting the intense interest taken by the people in their beasts. A man often knows his cattle by name; and his bull, the pride of his herd, is hailed in laudatory phrases as it comes out of the kraal.(Schapera and Goodwin 1937, p. 138)

The pregnancy of cattle symbolism and their roles in Bantu-speaker–society negotiations of wealth and power are key reasons why cattle raiding has long been a key element of African societies, at least as evidenced historically and ethnographically with presumable earlier origins. Such societies are tied into cycles of raids and retaliations not disconnected from the general process of group fission and fusion, men’s wealth and the physical and symbolically charged exchange of women (wives) for cattle (Schapera 1930; Hammond-Tooke 1974a). Whom cattle are taken or hidden from, or to whom they are given, carries significant implications. For that reason, cattle were continuously contested: their social capacity to function as symbolically charged currency meant that they constantly teetered between those who possessed them and those who did not or soon would.

Here, I agree with those writers who maintain that contact-era rock art images, especially those involving cattle, must have resonated with herding and Bantu-speaking audiences, even in contexts where the images appear to have been performed in the hunter-gatherer tradition and in traditionally San territories (e.g., Campbell 1987; Jolly 2007; Loubser and Laurens 1994; Hollmann 2015; Skinner and Challis 2022).

The Ventershoek panel and the preceding discussion of the ethnographic material suggest that we have at least two sides from which to view and interpret what appears to have been a San depiction of conflict over cattle. How might the conflict have been perceived by each audience? The scene contains several clues.

5.3. The Dead and Dying

In Figure 3, at least two of the shield-bearers have shields impaled with arrows (cf. Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 89). The one prone black figure does not appear to have been struck by an arrow (Figure 5, cf. Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 62), but in the absence of further contextual information, it seems reasonable to assume that the figure was struck down or killed in the conflict.

Figure 5.

Detail of the prone figure in Figure 3.

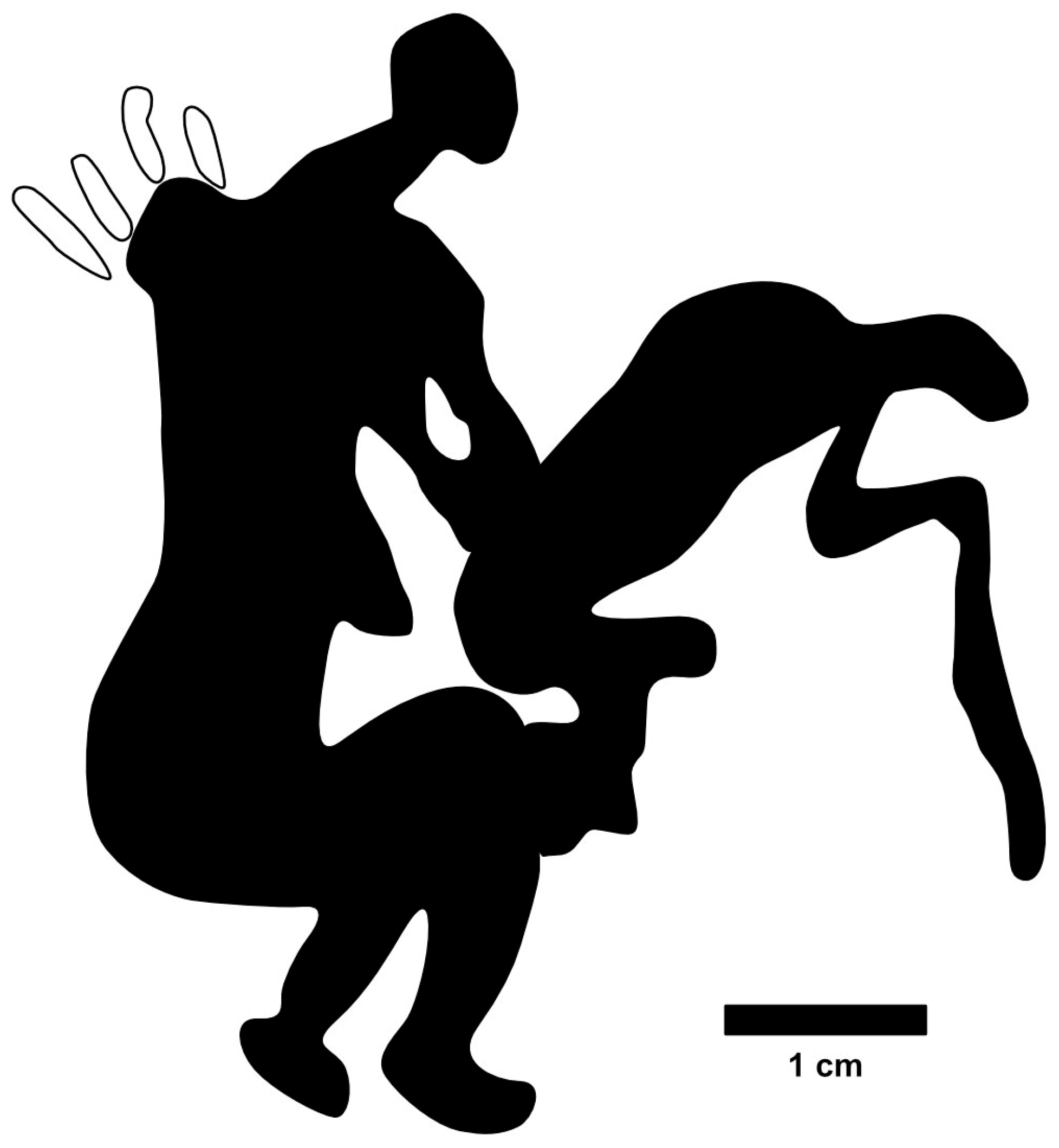

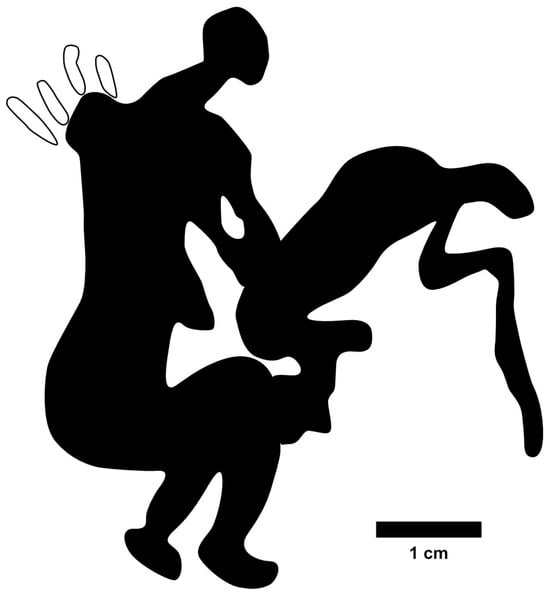

The panel contains a second, less obvious allusion to death (Figure 6). The reconstruction of the Ventershoek panel draws attention to a pair of human figures absent from earlier copies but noted by some writers (Ellenberger 2003, p. 24): a larger human figure with the remains of white arrows in his quiver crouches to aid a smaller, frail figure that supports itself with one arm on a stick (Figure 6, cf. Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 62). Although it has been suggested that their orange appearance today results from the weathering of darker, red paint (Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 110), the yellow-orange hue more likely indicates that their original paint colour was not identical to that of the other red figures. Today, the pair is not easily visible on the rock face. Nevertheless, it appears to have been painted at the same time as, but lower down than, the lines of red figures (Figure 2, cf. Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 62). It has also been suggested that the frail figure may be a wounded man with a crutch (Ellenberger 2003, p. 24; Le Quellec et al. 2015, pp. 87, 110). Given the context of the Ventershoek scene, that may be an overly literal interpretation of San rock art, which is known not to merely illustrate observations. Instead, three features suggest that it is probably a painted San allusion to ritualised intervention via the spirit world.

Figure 6.

The pair of figures noted during the digital reconstruction of the panel. The larger figure seems to care for the smaller figure as he enters the spirit world to mediate conflict. Note the differences in head shape. The position of the pair is indicated in Figure 2. Drawn after (Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 62).

First, the larger human figure in Figure 6 appears to touch or hold the smaller figure’s lower back. Such gestures of caring, massage and cooperation are known from San ethnography (Marshall 1999; Low 2007b) and rock art contexts. At healing dances, women care for comatose ‘dead’ healers, the healers care for each other and master healers care for their novices, holding them, massaging them and rubbing them with sweat and sometimes blood (Katz 1982; Marshall 1999; Low 2007b). No one who enters the spirit world should be left alone or unaided.

Second, the bent figure’s crouching posture and stick are probably further references to ritualised intervention via entry into the spirit world. Dance sticks are common trance-dance objects, frequently used especially by older, more experienced healers (Jolly 2006).

Third, although the pair of images has not preserved well, the smaller figure’s elongated, muzzle-like head as compared to the larger figure’s round head may suggest that he experiences somatic transformation into a partly animal being. The spectrum of crouching and bending postures-cum-transformations is well documented in San rock art and is exemplified by depictions known as trance buck or flying buck (Pager 1971; Lewis-Williams 1981, p. 100). If the pair in Figure 6 alludes to an owner of potency’s transformation, San viewers would not have missed it. Moreover, the pair’s addition to the panel, and to the conflict scene in particular, further clarified its meaning for viewers.

As noted above, the ideal San resolution of conflict involves cosmological interventions by owners of potency to mediate antagonistic situations and relationships. The little bent figure in Figure 6 is, therefore, probably an owner of potency who intervenes in the depicted conflict. Death is a San metaphor for entry into ASC; in that sense, the frail figure in Figure 6 is dead. Although he stands off to one side, away from the heat of the battle, in his own way (his community’s own way), he dives into the fray.

Depictions of intervention by ritual mediators who stand back from the fighting are not unprecedented. Figure 7 shows one of the best-known colonial-era examples from RSA BEH1 in the KwaZulu-Natal Province (Campbell 1986, p. 263; Challis 2008, p. 289). On the right side of the conflict, behind horse riders and armed figures in colonial-era dress, a transformed, feathered and stick-bearing mediator bleeds from his nose—a San sign of ritualised intervention.

Figure 7.

A schematic drawing from a tracing of the colonial-era conflict scene at RSA BEH1. As indicated by the red triangle, a transformed figure intervenes in the battle. © Rock Art Research Institute and the African Rock Art Digital Archive (www.sarada.co.za).

5.4. Two ‘War Medicines’

The prone black figure in Figure 5 and his fellow fighters are surrounded by arrows; as noted above, at least two of the shields in Figure 3 are impaled with arrows (cf. Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 89). The red bowmen in Figure 3 appear not to have been pierced by their opponents’ spears, which instead seem to have come to rest behind and between the bowmen (cf. Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 62).

Might each side have invoked means to protect themselves from enemy projectiles? The bent-over figure’s (Figure 6) spirit-world mediation would be sufficient a means to protect the bowmen on his side. On the opposing side, and to the right of the prone figure’s feet, another black human figure holds a shield in one hand and a short, slightly bent stick-like object in the other (Figure 8). It is not an arrow or a spear. This unusual object, depicted in a conflict context with related figures that are surrounded but not impaled by arrows, likely alludes to the protective war medicines used predominantly but not exclusively by Bantu-speaking societies (Challis 2008, 146ff; 2014; Sinclair-Thomson and Challis 2017).

Figure 8.

Detail from Figure 3 of the human that holds a shield and a bent stick-like object.

Like San owners of potency, Bantu-speaking groups, especially Nguni and Sotho, also had and employed the means to intervene in conflict via the unseen world and its forces (for an overview of this topic, see Sinclair-Thomson and Challis 2017). Protective ‘medicine’ substances were used in war and conflict, even in stick-fighting between boys. Diverse though this category of medicine is, the roots of particular plants were a common form (Challis 2008, 146ff; 2014; Sinclair-Thomson and Challis 2017). These were often chewed, and rock art depictions suggest that the stick-like roots were also carried or brandished (e.g., Challis 2016, p. 297). In the colonial period, war medicine of this kind was said to have the power to turn bullets into water (Sinclair-Thomson and Challis 2017).

5.5. Two Parties Contesting Cattle

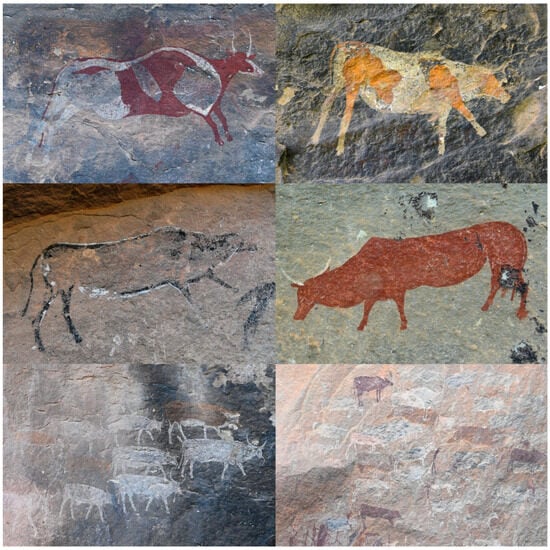

It has been suggested from an art-historical perspective that the arrangement of coloured and patterned running cattle images in the Ventershoek panel is an important structural element of how a mythologised San narrative scene was composed (Le Quellec et al. 2015, 83ff). In place of culturally distant Western art-historical categories and notions of mythology, we should strive to arrive at the image-makers’ perception of their own images, especially if multiple audiences are implicated. In doing so, we will have reason to note further details that would have resonated with San and Bantu-speaking audiences.

Cattle coat patterns, colours and colour combinations are symbolic in Bantu-speaking societies (e.g., Oosthuizen 1996; Poland et al. 2003; Louwrens and Taljard 2008; Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 86; Motsamayi 2020, see also Evans-Pritchard 1940). The patterns themselves and their symbolism, not merely their colours, are significant. At Ventershoek, several animals share the same colours, but only the two monochrome white animals have identical coats. Why might ‘San’ image-makers have emphasised this dimension of putatively ‘Bantu’ cattle symbolism? Had that symbolism, by the time the image was made, become part of ‘San’ symbolism too? To argue that the paintings merely reflect the San image-makers’ keen observations of Nguni cattle would be to avoid addressing the potential that cattle images resonated in profound ways with both San and Bantu-speaking audiences. As I have noted, distinct boundaries between ‘San hunter-gatherers’ and ‘Bantu-speaking agro-pastoralists’ were not invariably maintained in the contact era.

In addition to patterned coats, one individual animal in the top left corner of Figure 3 is marked by distinct downward-pointing horns (Figure 9, Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 108)—a highly significant feature to which not enough attention has been drawn. The practice of horn shaping is known across herding societies in Africa (e.g., Epstein 1971, p. 422; Shaw and van Warmelo 1981, 238ff, passim; Wilson and Thompson 1982, pp. 108, 130; Poland et al. 2003, p. 132; cf. Evans-Pritchard 1940). It marks to whom an individual beast belongs and, by association, to whom the rest of the animals in a group or herd belong.

Figure 9.

Detail from Figure 3 of the animal with downward-pointing horns.

Such Bantu-speaker allusions to animal ownership find parallels in San thought: ‘god’ (ǀKaggen) marked his animals: ‘[a]ll the beasts of the field have marks, which he has given them; for example, this elan [sic] has got from him only the stump of a tail; that a folded ear; this other, on the contrary, a pierced ear’ (Arbousset and Daumas 1846, p. 253). We must assume that, at the very least, San viewers would have recognised that signature-horned cattle had specific owners. For whom, then, was this allusion to possession included in the panel?

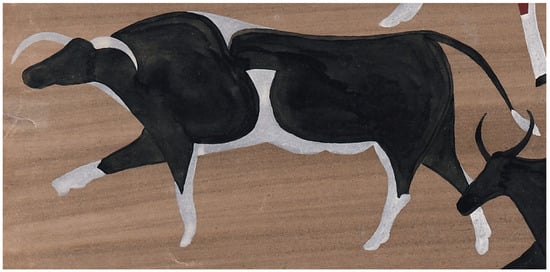

Ethological details take us further still: the cattle in the depicted group are distressed, a point which has not been addressed in previous discussions of the panel. Most of the animals appear to be running, some perhaps faster than others. The positions of their tails indicate their mood (Albright and Arave 1997, pp. 45, 46, 49). The tails of galloping cattle extend behind them almost horizontally. When at ease, a cow or bull’s tail hangs vertically, close to the body. When threatened, by contrast, the tail hangs vertically at some distance from the body. Both galloping and a threatened mood are indicated in the cattle shown in Figure 3 (cf. Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 70). Figure 10 shows that one bull’s tail curls up and over its rump (there is also a possible second, yellow example shown in Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 62). This bull ‘wringing’ its tail is another ethological indicator of distress in cattle.

Figure 10.

Detail from Figure 3 of a bull wringing his tail.

Clearly, the image-makers understood and elected to depict distressed cattle behaviours. Again, we may ask for which audience was it intended? Would each audience have necessarily understood the references to distressed cattle in the same way? I suggest that by the time this panel was painted, both San and Bantu-speaking viewers would have been able to answer these questions.

The bull wringing its tail leads us on to further details. The cattle group seems to include several bulls and bullocks (castrated bulls) at various stages of maturity. At least two are mature bulls: one (possibly both) has a scrotum, both are large and have pronounced shoulder humps (sexually dimorphic features) and both have clear penis sheaths that are ambiguously suggested on some of the other individual cattle depicted (cf. Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 87). In southern African Bantu-speaking societies, ‘[m]ost bulls are castrated, only one or two being kept in each herd for breeding purposes’ (Schapera and Goodwin 1937, p. 139 citing Stayt 1931, p. 38). As noted above, a bull is also considered to be the pride of a man’s herd (Schapera and Goodwin 1937, p. 138). To Bantu-speaking audiences, the depiction of bulls would have been a significant allusion to ownership.

The gait of the cattle depicted in the Ventershoek panel is unusual in San rock art. To the best of my knowledge, most other images of cattle in similar gaits are not as exaggerated (cf. Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 91). Compare, for example, the positions of the cattle legs in Figure 3 with those in Figure 11 (cf. Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 70). The near-horizontal forelegs at Ventershoek are distinct.4

Figure 11.

Cattle images from rock art sites in the Eastern Cape Province. The position of the legs typically shows the standing or walking support of the animal’s weight. Cattle images are often depicted in a twisted perspective that, for example, simultaneously shows the forelegs and ‘chest’ at the front and, at the rear, the near side of the rump. Sites clockwise from the top left: RSA PRO4, RSA BUF1, RSA MAH1, RSA AND3, a shelter near Rossouw and RSA FLO7. Image by the author.

Then, we may note from the position of the legs relative to the body and the perspective indicated chiefly by the colouring of the bodies that at least thirteen of the sixteen adult beasts in Figure 3 appear to extend their right forelegs (cf. Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 62).5 The animal in the top lefthand corner of Figure 3 seems to have its left foreleg forward, and the leg positions of the two monochrome white cows, which might otherwise be considered ambiguous, appear to be the same as that of the majority. The reconstructed panel (Le Quellec et al. 2015, fig. 67) shows that one image of a docile cow, which walks in the opposite direction behind the shield-bearers, also appears to lead with its right foreleg.6

The image-makers therefore appear to have emphasised the unusual extension of the right foreleg in most of the cattle depicted. This unusual feature may indicate the speed at which the distressed cattle are moving. However, if it is merely a stylistic convention that emphasises extended right forelegs over left ones (Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 91), its relevance to a particular audience still requires explanation. Certainly, not all rock art images of cattle depict them as leading with near-horizontal right forelegs (e.g., Figure 11; Witelson 2023, pp. 62, 78). Purely chance or stylistic repetition seems yet more unlikely when one notes the variety of other minutely painted details: millimetre-scale arrows, multi-coloured spears, human bodies with tiny white details and the lack of repetition in the coat patterns on the cattle bodies.

It is, I suggest, reasonable to consider the possibility that the repeated emphasis on the right foreleg may allude to something which an informed audience would not have missed. For example, in Bantu-speaking cultures, and for anyone intimately involved in their society, a conceptual map of laterally symbolic cattle bodies is carried in the mind (e.g., Huffman 1996, p. 118 citing Stayt 1931, p. 4, 197–201; on lateralised symbolism, see Augé 2024). The lateralised symbolism of cattle in the Bantu-speaking worldview plays into the situational entitlement of particular members of society to specific parts of butchered animals, especially when animals are ritually killed rather than slaughtered for meat. Among Nguni and Sotho groups, for example, the choice parts typically but not invariably go to initiates, notably boys who are to become men and the warriors who will defend their chief’s cattle (e.g., Hoernlé 1937, p. 232; Hunter 1937, p. 401; Ashton 1952, pp. 48, 158, 182; Hunter [1936] 1961; Hammond-Tooke 1974b, p. 353; van der Vliet 1974, p. 229; Peires 1981, pp. 28, 47; Kuckertz 1983, p. 128). Might the extended or leading right forelegs be further allusions to cattle ownership?

The concept of laterally symbolic animal bodies would also have been comprehensible to San audiences. For example, and in addition to San familiarity with how agro-pastoralists thought about cattle, the forelegs of eland antelope, the most central and pervasive symbolic animal in San thought, were part of Juǀ’hoan boys’ initiation as hunters: ‘while the seated boy holds his bow pointing out in front of him, the string uppermost, an old man takes the right foreleg of the eland, or the left if it is a female, and makes a circle of eland hoof prints around the skin on which the boy is sitting’ (Lewis-Williams and Biesele 1978, p. 129). In any case, it is difficult not to suppose, from the perspective of a Bantu-speaking audience, that the cattle would in any event have been considered the property of a particular chief and the charge of men initiated as defenders of the herd.

5.6. Performers and Audiences

While most previous considerations of the Ventershoek conflict scene have pondered from a Western perspective the cultural or ethnic identities of the depicted groups or the supposed mythico-narrative nature of painted scenes, performance theory draws attention to key details emphasised in the panel (especially the painted allusions to ritual mediation, war medicine and cattle ethology and symbolism) and asks why and for whom the images may have been performed.

The contingent processes inherent in performances allow researchers to move from generalisations about all or generic ‘San’ conflict scenes to the specific details of individual scenes and, as far as it is possible to do so, to pay attention to the participants most likely to have been involved. Given the complex and variable social circumstances of the contact-era as outlined above, specificities are preferable to generalities.

The Ventershoek conflict scene has long been recognised as a depiction of a battle over cattle between a ‘San’ and a ‘Nguni’ group. It has also long been thought that the scene in Figure 3 gives an overwhelmingly San perspective on this conflict, not least because the image-makers emphasised that the red ‘San’ figures have the cattle on their side: the cattle are not in the ‘Nguni’ shield-bearers’ possession. Might the cattle’s distress in the red figures’ possession and the image-makers’ emphasis on the extended right forelegs be further indications that the ‘Nguni’ side has been dispossessed of some cattle? Certainly, whoever made the panel knew to whom the cattle belonged.

The frail figure’s (Figure 6) intervention on behalf of his community appears to have ensured the outcome. Given that the panel appears to make a triumphant ‘San’ statement, ‘Nguni’ are unlikely to have been the principal image-makers (cf. Loubser and Laurens 1994, p. 81), although there are known instances of image-makers belonging to multi-ethnic ‘San’ groups. We have on record, for example, that the last known ‘San’ rock painters were not ethnic San but rather agro-pastoral BaPhuthi who had San relatives (How 1962; Jolly 2014, pp. 307–9; 2024; King et al. 2022). Historical sources also evidence that nineteenth-century ‘San bands’ included individuals who belonged to Nguni groups (e.g., Stanford 1910; Blundell 2004; Challis 2014; Sinclair-Thomson 2021).

How might a Nguni audience have assessed the painted display in the Ventershoek conflict scene? At least one Nguni group (AmaZizi) is known to have occupied the Caledon Valley area near Ventershoek in the early seventeenth century (Jolly 1996b, p. 33). More generally, cattle scenes in the broader Maloti-Drakensberg region seem to have been made beyond the territorial limits of historical Sotho-Tswana and Nguni agro-pastoral groups (Loubser and Laurens 1994, p. 116). This does not mean, however, that territorial boundaries were impermeable or that individuals from groups in other territories were not implicated or participants in the depicted performances themselves. In those days, ‘frontiers’ were not sharp lines drawn on maps but rather flexible zones of interaction of various kinds. We can infer only that, when the performances of image-making occurred, they seem to have occurred most often in historically San territories.

What did the making—the performance—of the Ventershoek images achieve? For whom did the image-maker(s) deliberately display these images? It would be difficult to conclude that this conflict scene would have filled San and Nguni audiences with feelings of amity towards each other. By contrast, it seems reasonable to assume that a Nguni audience (but not necessarily all Nguni audiences) would have perceived the painted allusion to the San possession of cattle in a negative light. Indeed, the Ventershoek image-makers appear to have displayed, for an intended audience (perhaps more than one), at least one set of relationships between some specific ‘San’ and some specific ‘Nguni’ in terms of their relative acquisition, possession or dispossession of cattle. The ‘message’ displayed in the panel must have been reified via the interaction between the image-makers and the intended audience and their collective, social construction of reality in the performance setting and afterwards.

It is, therefore, not so much the case that the Ventershoek scene shows that the cattle depicted belong either to ‘the San’ or ‘the Nguni’, but rather, and in more specific terms, the panel shows one group’s possession or acquisition of cattle relative to the other group. In that sense, the panel contains a politically charged statement illustrative of the image-makers’ agency and capacity to engage, via their access to spiritual realms and forces, in particular ways with their neighbours. The performance of contact-era images navigated both a changing ‘San’ world and ‘San’ relationships with neighbours on a case-by-case, performance-by-performance basis.

6. Concluding Discussion

Having outlined San hunter-gatherer image-making earlier in this paper, I return in this section to a key but often tacit concern of interactionist research: did the traditional, mediatory purpose of San image-making in the hunter-gatherer tradition endure in the contact era despite the changes to the imagery’s subject matter, painting techniques, paint recipes and colour palette and, most importantly, the composition of its audiences?

Some researchers have argued historically that rock art depictions of ‘not San’ things (such as cattle and shields) suggest that the image-makers were themselves not ‘San’, while others have suggested that, even in such cases and precisely because of the contextualising cross-cultural interactions, a San perspective necessarily applies because principally San groups produced the imagery (Loubser and Laurens 1994, p. 116). Some writers have thus suggested that considerations of contact-era rock art cannot exclude what is known about ‘San’ rock art practices, while others have suggested that the beliefs and worldviews of Bantu-speaking groups must be addressed when interpreting ‘San’ rock art (e.g., Jolly 1996a; Hollmann 2015; Skinner and Challis 2022). Still other writers have suggested that colonial-era changes to the hunter-gatherer tradition of rock art are attributable to ‘the increasingly heterogeneous and creolising membership of the art-producing people and the mixing of their cosmologies, albeit with specific cultural survivals’ (Challis and Sinclair-Thomson 2022, p. S98). In any event, there is no doubt that a diversity of responses to contact is evidenced by the diversity of colonial-era rock arts (e.g., Challis 2008, 2009, 2012, 2014, 2016; Blundell 2021).

This paper finds further support for two general conclusions of the southern African interactionist rock art literature. First, traditional hunter-gatherer imagery changed visibly in the contact era and did so relative to, rather than independently of, the older image-making mode. Second, and whatever minor differences of opinion individual researchers may hold, it should be relatively uncontroversial to state that the traditional purpose of hunter-gatherer image-making—as a means for image-makers to mediate, on behalf of their communities, relationships between multiple entities across ontological boundaries—did not change in the contact-era developments and evolutions of the older mode. Rather, the traditional purpose was adapted to new circumstances and new kinds of interactions and relationships (Witelson 2023, p. 86). Certainly, we can no longer see panels such as the Ventershoek conflict scene as depicting mythologised narratives.

I have argued elsewhere that, in the contact era, the primary ‘Others’ confronted by hunter-gatherers changed from being the spirit beings in the spirit realm (without their disappearing) to primarily the other peoples who now lived in the same parts of southern Africa (Witelson 2023, pp. 72–75, 100–1). This is significant: in a very real rather than merely metaphorical sense, the San performance of imagery continued to address potentially conflictual and agonistic circumstances. In that sense, too, there appears to have been very little change to the purpose of image-making performances into the contact era.

Because cross-cultural engagements in the contact era involved higher orders of social and cultural diversity than in the pre-contact era, I argue that ritual mediation was needed in a wider range of social contexts and that image-making was put to use. I suggest, following my own findings and that of numerous interactionist writers, that the interpretation of contact-era rock art is best approached with a combination of as many sources of evidence as are available to most fully inform the context in which the images may have been performed. If it is true that categories like ‘San hunter-gatherer’ and ‘Bantu agro-pastoralist’ are overly general in many discussions of contact-era interactions, then it is also true that too heavy an emphasis on a particular audience or too heavy a reliance on sources concerning each of these categories will inevitably miss addressing the contingent specificities of specific performances of rock art. Performances are by definition contingent processes that—despite customary elements established by repetitions in multiple, cross-referential performances that share performers and participants—require specific considerations for each case. No two performances, however similar, are identical in every aspect. Performance theory thus lends itself to thorough investigations of the nuances of the production and consumption of rock art in the contact era.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | One of the museum displays at the !Khwa ttu centre for San heritage near Cape Town estimates the figure at around 40,000 rock art sites across South Africa, Lesotho, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Eswatini. There is no official statistic. |

| 2 | Some writers have assumed from qualitative observations of rock paintings that social change is evidenced by changes to rock art pigment sources or pigment quality through time. However, no systematic physico-chemical or experimental research exists that specifically addresses the assumed changes to pigment sources or quality. In the absence of the relevant data, and once it has been acquired, discussions must necessarily focus on whole paint recipes. |

| 3 | (Le Quellec et al. 2015). Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272621018_Cattle_theft_in_Christol_Cave_A_critical_history_of_a_rock_image_in_South_Africa (accessed on 18 April 2024). |

| 4 | A stylised version of one of the distinct extended right forelegs from Ventershoek now appears in the logo of the Research branch of the French Institute of South Africa. |

| 5 | Stow’s copy gives a misleading impression of leading leg because it gives his interpretation of painted form and depth of the the flat, unmodulated images painted on the rock face. Helen Tongue’s historical tracings of his copies respect his interpretation. The recent reconstruction of the panel is more accurate (Le Quellec et al. 2015, p. 62). |

| 6 | Because the cow image in question is accompanied by two black human figures that are smaller and thinner than those in the core conflict group, it is mostly likely to have been added after the core group was painted and when the other smaller and thinner black human figures were added to the central panel (cf. Le Quellec et al. 2015, pp. 62, 63). |

References

- Albright, Jack L., and Clive W. Arave. 1997. The Behavior of Cattle. New York: CAB International. [Google Scholar]

- Arbousset, Thomas, and François Daumas. 1846. Narrative of an Exploratory Tour to the North-East of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope. Translated by John Croumbie Brown. Cape Town: Robertson. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, Edmund Hugh. 1952. The Basuto. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Augé, C. Riley. 2024. Sinister and Righteous: Interpreting Left and Right in the Archaeological Record. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, Alan. 1992. Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa: A Comparative Ethnography of the Khoisan Peoples. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, Alan. 2017. Egalitarian and non-egalitarian sociality. In Human Nature and Social Life: Essays in Honour of Professor Signe Howell. Edited by Jon Henrik Ziegler Remme and Kenneth Sillander. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, Alan. 2019. Bushmen: Kalahari Hunter-Gatherers and their Descendants. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Battiss, Walter. 1948. The Artists of the Rocks. Pretoria: Red Fawn Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bial, Henry, and Sara Brady, eds. 2016. The Performance Studies Reader, 3rd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Biesele, Megan. 1993. Women Like Meat: The Folklore and Foraging Ideology of the Kalahari Juǀ’hoan. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bleek, Dorothea F. 1956. A Bushman Dictionary. New Haven: American Oriental Society. [Google Scholar]

- Blundell, Geoffrey. 2004. Nqabayo’s Nomansland: San Rock Art and the Somatic Past. Uppsala: Uppsala University. [Google Scholar]

- Blundell, Geoffrey. 2021. Image and identity: Modelling the emergence of a ‘new’ rock art tradition in southern Africa. In Perspective on Differences in Rock Art. Edited by Jan Magne Gjerde and Mari Strifeldt Arntzen. Yorkshire: Equinox, pp. 302–19. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith. 1988. Performative acts and gender constitution: An essay in phenomenology and feminist theory. Theatre Journal 46: 519–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]