Abstract

Traditional cultural practices, increasingly impacted by modernisation and urbanisation, are experiencing diminished transmission and declining interest among younger generations. Teochew opera in Malaysia is no exception, pressured under similar challenges in sustaining its relevance and appeal within contemporary society. Considering these shifts, the sustainable preservation and revitalisation of traditional arts has become a pressing concern for scholars and cultural practitioners alike. This study investigates strategies for sustaining Teochew opera in Malaysia, employing qualitative methods including participant observation and semi-structured interviews. The findings reveal that Teochew opera operates within a sacred and secular framework, serving religious rituals and cultural festivals. This duality allows for continuity through tradition in sacred settings and adaptation through innovation in secular contexts. The coexistence of these realms offers a blueprint for sustainable cultural evolution. While challenges such as low youth engagement and limited institutional support persist, the research underscores the potential of educational initiatives and community-driven efforts to renew interest and ensure continuity. The study contributes valuable insights for policymakers and cultural stakeholders seeking to safeguard intangible cultural heritage in pluralistic, rapidly modernising societies.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

Teochew opera represents a distinctive and vibrant form of traditional Chinese opera, which combines singing, instrumental music, dialogue, theatre, and martial arts in a narrative style. Its musicality is exemplified by its high-pitched singing, typically accompanied by traditional Chinese instruments such as the yehu, yangqin, gongs, and drums. The narratives presented in its performances are deeply rooted in historical tales, folklore, and moral stories, reflecting Chinese cultural values and social norms (Wu 2015). Teochew opera originated in the Ming Dynasty in China. Throughout the centuries, it has evolved, successfully maintaining its traditional essence while simultaneously adapting to the diverse social environments into which the Chinese populace has migrated, such as Malaysia (Tan and Fernandez 2023). In this multicultural context, interactions among various ethnic communities have catalysed unique cultural expressions, allowing it to develop amidst a tapestry of diverse artistic influences.

The historical migration of Teochew-speaking Chinese individuals to Malaysia during the 19th and early 20th centuries laid the critical foundation for establishing Teochew opera in the region (Lai 1993). This migration was a component of a broader diasporic movement among the Chinese community throughout Southeast Asia, primarily motivated by the pursuit of economic opportunities and improved living conditions. As these communities settled in Malaysia, they carried cherished cultural practices, with this opera rapidly embedding itself within their new environments’ social and cultural fabric.

Over the decades, Teochew opera in Malaysia has experienced significant growth, buoyed by a vibrant community dedicated to its preservation and promotion. While remaining true to its traditional character, the opera has dynamically adapted by incorporating various elements from the local culture. This adaptability has ensured its continued relevance and appeal as it responds to the changing expectations of contemporary audiences (Wu 2015). The maintenance of Teochew opera in the Malaysian cultural landscape exemplifies the resilience of this traditional art form, demonstrating its capacity to sustain itself even in the face of modernisation and globalisation.

1.2. Literature Review

The interplay between tradition and modernity in sustaining traditional performing arts has attracted increasing scholarly attention, particularly within the conceptual frameworks of cultural resilience and sustainability. In the case of Teochew opera in China, revitalisation has largely occurred through top-down institutional mechanisms, including its inscription as national intangible cultural heritage, state subsidies, and integration into educational and tourism platforms (Wang 2007; Zeng 2015; Zhu 2020). These interventions have undoubtedly enhanced the opera’s visibility and facilitated its transmission. However, scholars have also raised concerns regarding the potential marginalisation of community agency, noting that state-led institutionalisation may lead to a form of “heritage freeze” that prioritises preservation over organic evolution (Pan 2005; Gregory 2009).

More broadly, the literature on traditional performing arts has underscored the persistent tensions between innovation and preservation. Challenges such as cultural dilution under excessive modernisation, economic precarity in commercialised creative economies, and generational disengagement—particularly among youth audiences—continue to threaten the sustainability of ICH practices (Throsby 2019; Hafstein 2008). Scholars critical of market-driven heritage models have further argued that commodification risks distorting traditional expressions and disembedding them from their sociocultural origins (Cohen 1988; Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 2004).

In 2006, Teochew opera was inscribed as a National Intangible Cultural Heritage of China. Backed by favourable state policies; it has since attracted widespread attention and received substantial protection (H. Liu 2010). In contrast to the state-mediated revival in China, Teochew opera in Malaysia endures through decentralised, community-based efforts operating in a multicultural and diasporic context. With limited government funding or policy intervention, local associations, temple committees, and cultural organisers have sustained the art form through grassroots festivals, intergenerational apprenticeship, and context-sensitive adaptations (Kang 2005; K. Liu and Chen 2009; Law 2016). These practices reflect a form of cultural resilience—the capacity of a community to adapt and reconfigure its cultural expressions while maintaining core values in the face of external pressures (Tavares et al. 2021).

1.3. Problem Statement

Amid accelerating modernisation and global cultural convergence, traditional performing arts increasingly confront challenges to their relevance. Teochew opera, once central to the cultural life of Chinese diasporic communities, faces particular vulnerability in multicultural societies like Malaysia. Digital media proliferation and commercially driven entertainment have altered aesthetic norms and consumption habits, diminishing the visibility and accessibility of traditional forms. These pressures are compounded by generational disengagement and the absence of formal educational support, threatening long-term transmission.

Despite these constraints, Teochew opera in Malaysia has persisted through pragmatic adaptations. Ritual performances remain embedded in community festivals and temple events, while public cultural festivals provide platforms for creative experimentation and audience outreach. These dual strategies reflect an ongoing negotiation between continuity and innovation.

However, scholarly attention to such localised adaptations remains limited. The existing literature tends to focus on the opera’s historical development in China or its general diasporic presence, with scant analysis of how Malaysia’s multicultural context shapes its evolving performance practices and sociocultural meanings. While community-led initiatives are central to the opera’s endurance, their role in enacting cultural resilience and sustainability has received insufficient critical attention. Unlike state-mediated preservation in China, Teochew opera in Malaysia survives through decentralised, context-responsive practices grounded in everyday life. These reflect resilience—the capacity to adapt while preserving identity—and sustainability, defined as long-term cultural viability.

1.4. Research Questions and Objectives

This study examines the sustainable development of Teochew opera within Malaysia’s multicultural society, focusing on how the art form is maintained and revitalised through practices rooted in the Chinese Malaysian community. Rather than treating sustainability as a fixed outcome, the research approaches it as a context-specific process shaped by cultural agency and adaptive strategies.

The central research question asks: How is the sustainable development of Teochew opera achieved in Malaysia through community-based practices, and what enables its continued relevance in a pluralistic cultural landscape? In response, the study proposes the hypothesis that Teochew opera’s sustainability depends on strategies developed within the Chinese Malaysian community that negotiate between tradition and modernity, ensuring cultural continuity through adaptation, reinterpretation, and intergenerational transmission.

The originality of this research lies in its empirical focus on Malaysia as a diasporic, multicultural context where heritage preservation occurs largely through bottom-up, community-driven efforts rather than formal state intervention. While previous scholarship has focused on state-led revitalisation models in China, this study advances knowledge by critically analysing how Teochew opera persists and transforms in the absence of official heritage recognition. It offers a sustainable approach that may be applied to other traditional art forms facing similar pressures in globalised and multi-ethnic settings.

2. Results

Teochew opera in Malaysia is persevering and sustaining through practices in both sacred rituals and secular entertainment, and the content and purpose of performances on these two occasions are distinct. The subsequent results present performances in each context.

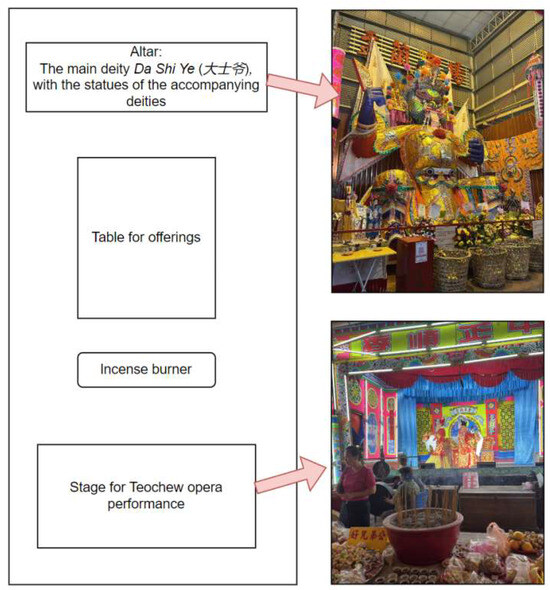

2.1. Teochew Opera in Sacred Ritual

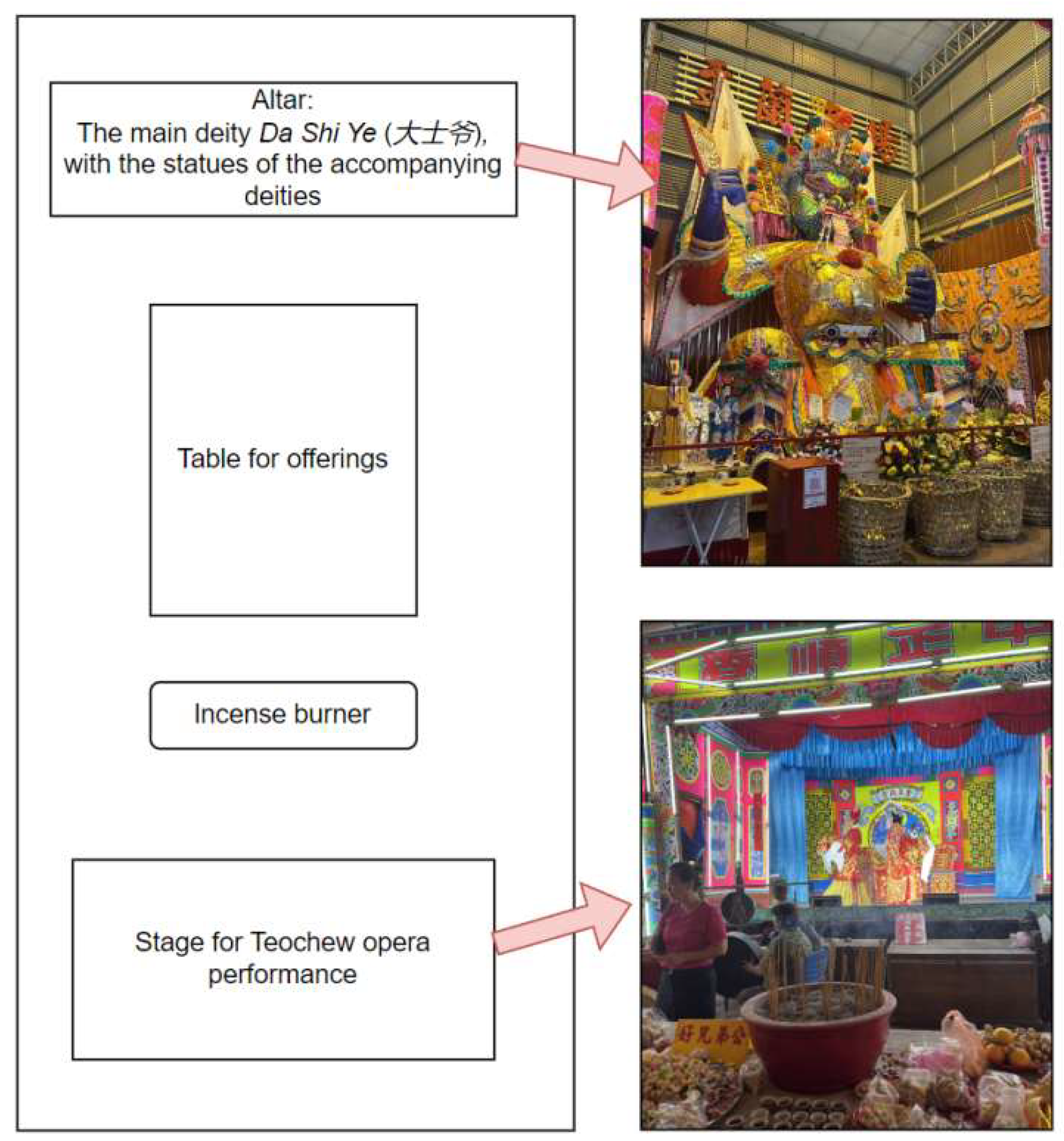

In contemporary Malaysia, Teochew opera remains a vital component of rituals, particularly within the religious practices of the Malaysian Chinese community that centre on beliefs in deities, ancestral spirits, and wandering ghosts. In Penang, where the tradition is especially well preserved, the opera continues to be performed during a wide range of ceremonial events, reflecting its enduring ritual significance. Table 1 shows the occasions on which the researcher observed it being performed during fieldwork. These performances are typically held in fixed temples, erecting a temporary stage opposite the statue of deities and dismantling after the event, as shown in Figure 1. The continued observance of these ritual forms in Penang highlights the relative integrity of Teochew opera’s ceremonial role within the local cultural–religious landscape.

Table 1.

Types and dates of rituals with Teochew opera performances in Malaysia.

Figure 1.

A temporary stage was set up in front of the deity statue for Teochew opera performances. (Photo by the author, 2023).

Teochew opera performed during the rituals preserves traditional customs. For example, during the Hungry Ghost Festival, a seating area is arranged for ghosts to watch a performance, as illustrated in Figure 2. According to Chinese traditions, attracting these ghosts through theatrical performances and placing offerings on the seats is believed to mitigate the harm they might inflict on the communities (Lim 2021).

Figure 2.

People set up empty red seats to invite ghosts to watch a Teochew opera. (Photo by the author, 2023).

Teochew opera performances within sacred contexts maintain traditional content, which consists of fixed ritual plays. Before the commencement of the entire performance, ritual performances known as an “impersonating deity play (扮仙戏)” are conducted, in which actors don attire representing deities, engaging in dramatic performances focused on praying for blessings and exorcising evil spirits. Each impersonating deity play in Teochew opera is independent and classified into large-scale and small-scale performances based on the number of performers and the duration. This categorisation is widely recognised among Malaysian Teochew opera practitioners. Furthermore, the repertoire of deity impersonation plays across all Teochew opera troupes is standardised, as shown in Table 2, with only minor variations in specific performance movements and costume details. Performing troupes, including local Malaysian groups, including Lao Yu Tang and Xin Yu Lou, as well as Thai troupes, such as Tiong Chia Soon Heang and Sai Boon Fong, contribute to the event.

Table 2.

Content of impersonating deity play of Teochew opera.

To illustrate how ritual-themed Teochew opera performances are interpreted by community members, Table 3 presents selected interview excerpts organised by thematic codes. These responses reveal the symbolic meanings assigned to each opera and highlight how participants perceive their ritual efficacy within specific socio-religious contexts.

Table 3.

Interview responses on the ritual functions of Teochew opera.

Interviewees consistently indicated that Teochew opera performances in ritual contexts serve two interconnected purposes. First, they act as a means of symbolic supplication, translating human wishes into visible, embodied forms directed toward the divine. These performances are not simply stories, but ritualised expressions of intent, made spiritually meaningful through movement, spatial arrangement, and sound. Second, the staging of the opera itself serves a ritual function. Temporary stages are typically set up facing the temple’s altar or with performers standing directly in front of the statue to perform (as shown in Figure 3), and timed with religious festivals, creating a sacred space where humans and deities symbolically meet.

Figure 3.

Performers staged a Teochew opera performance in front of the shrine. (Photo by the author, 2023).

Respondents stressed that aesthetic enjoyment is secondary. Audiences may come and go, and a full understanding of the story is not essential. What matters is the sincerity of the offering, its proper direction toward the deity, and its performance within the correct ritual context. In this setting, the opera functions as a sacred offering rather than as entertainment. Through codified gestures, costumes, and speech, actors temporarily take on divine or mythological roles, not to entertain, but to act as intermediaries between the human and spirit worlds. These roles are not spiritual possessions but ritual impersonations, legitimised by long-standing aesthetic and religious conventions.

In this context, Teochew opera functions less as theatre and more as embodied devotion—a ritual language through which communities express desires, affirm moral values, and restore cosmic balance. The convergence of story, bodily movement, and sacred setting makes these intentions spiritually intelligible, allowing brief but meaningful contact between the human and the divine.

In addition, music is a crucial element that supports the narrative of Teochew opera, particularly in ritual contexts, where the traditional accompanying instruments are faithfully retained, as shown in Table 4. The ensemble comprised Wenpan (文畔, orchestral instruments) and Wupan (武畔, percussion instruments). In Teochew opera performances, the Wenpan and Wupan work together to create a rich, multi-layered soundscape that enhances the storytelling. The Wenpan instruments are primarily responsible for the melodic and harmonic elements, supporting the singers and conveying the emotional undertones of the narrative. The Wupan instruments, on the other hand, add rhythmic complexity and dramatic punctuation, which are essential for action sequences and maintaining the pacing of the performance.

Table 4.

Traditional musical instruments used in Teochew opera during rituals.

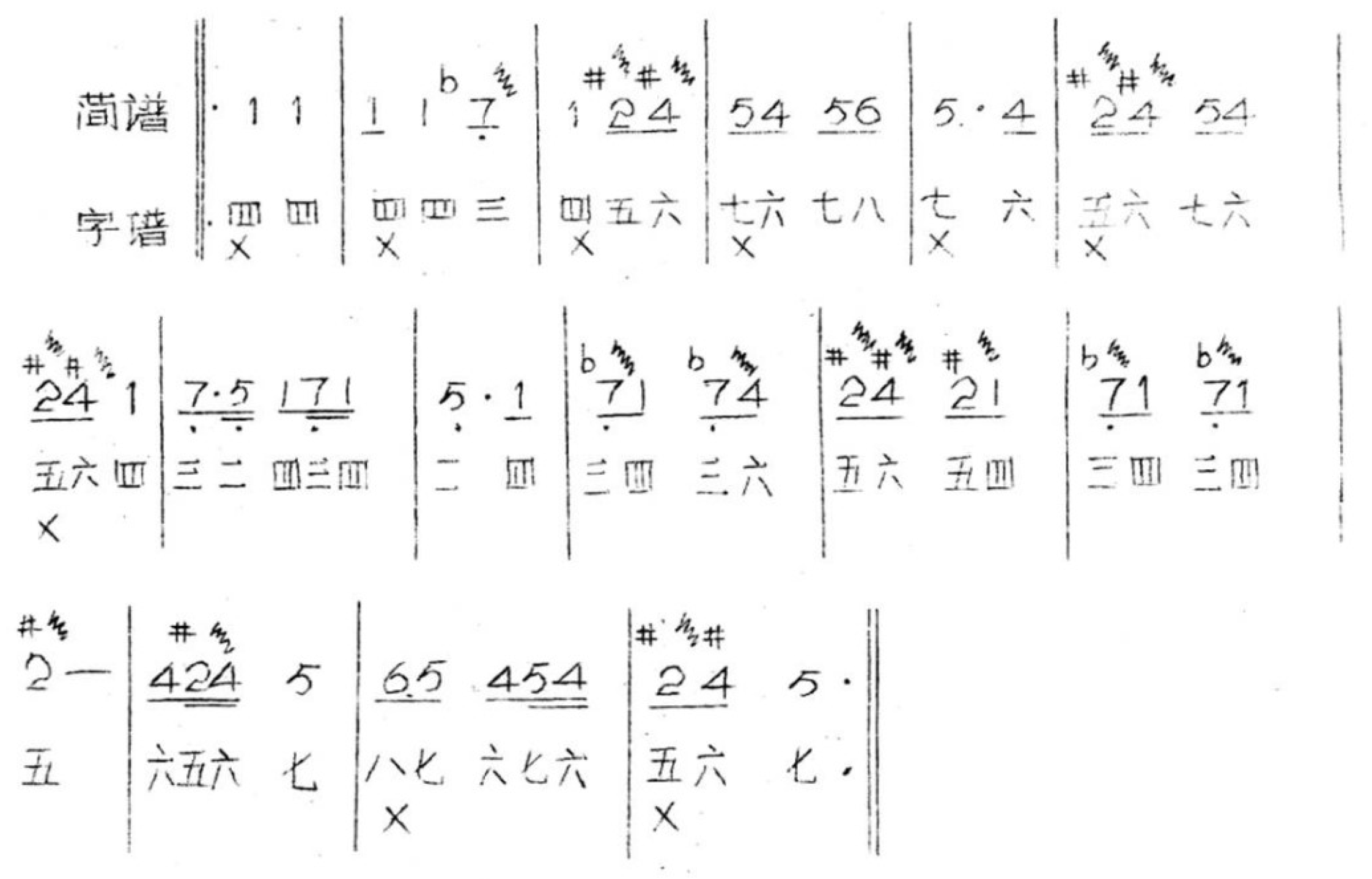

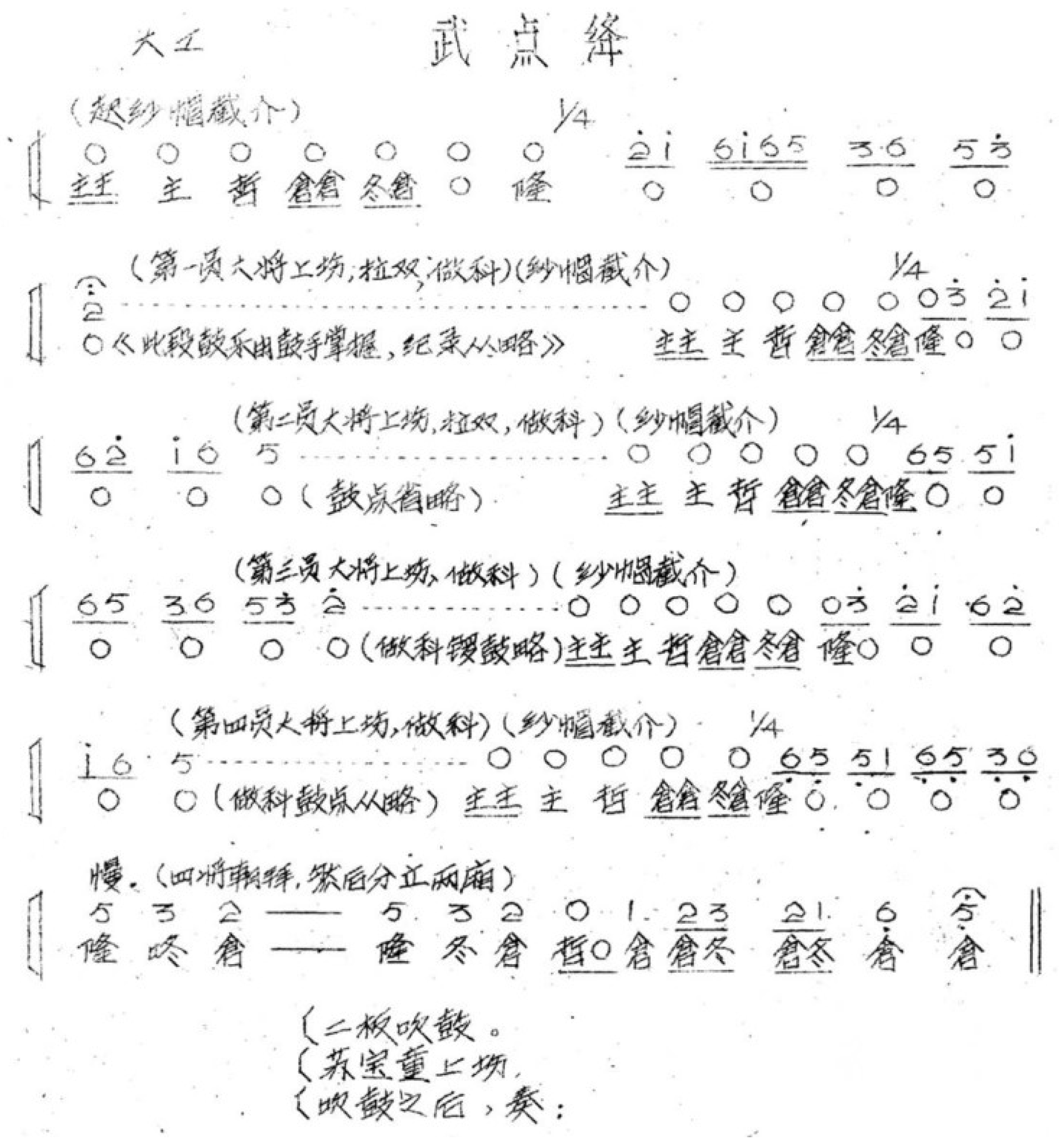

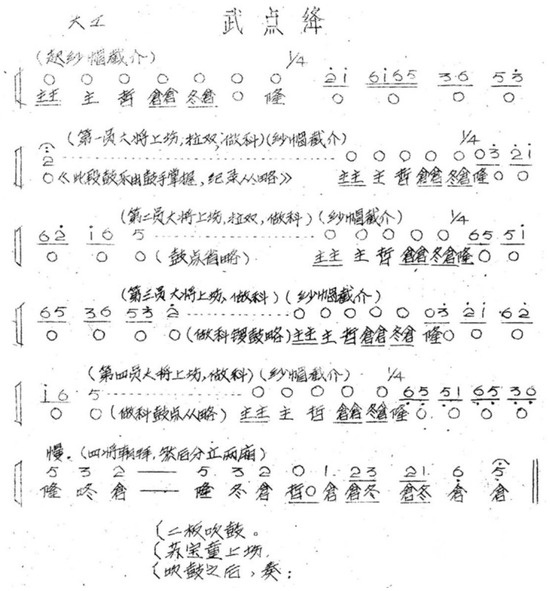

The performers of Teochew opera in rituals are generally elderly and staunch advocates of the tradition. For example, Teh (1952–present), the lead actor in Xin Yu Lou Troupe, is over seventy years old and noted that the principal actors in their troupe are all over fifty. Most of them still perform and rehearse using the two-four score (which uses Chinese characters to record pitch) or the gong and drum score (which uses onomatopoeic characters to record the sequence of musical instruments), as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, and teach new performers by oral instruction.

Figure 4.

An excerpt from the traditional two-four score of Teochew opera, which identifies pitch by Chinese numerals in Chinese characters. This traditional notation uses the Chinese numerals 二三四五六 (two, three, four, five, and six) to denote pitch (Provided by Teh, 22 May 2024).

Figure 5.

An excerpt from the traditional gong and drum score of Teochew opera, which indicates the order of instrumental performance by contrasting the Chinese characters’ onomatopoeia with the sound of the instrument. This notation employs Chinese character pronunciations corresponding to instrumental sounds to record the sequence of instrumental performance. For instance, “主 (Zhu)” denotes striking the drumhead with a single mallet followed by dampening to produce a muffled tone, while “隆 (Long)” signifies striking the drum with both mallets to create a strong and weak tone. (Provided by Teh, 22 May 2024).

To further elucidate how Teochew opera operates as a sacred form of ritual expression rather than conventional theatre, selected interview excerpts have been thematically coded and presented in Table 5. These responses highlight how performers and community members understand the opera as a devotional act, which is framed within codified ritual aesthetics and aimed at facilitating spiritual communication. Particular emphasis is placed on maintaining traditional gestures, costuming, spatial orientation, and musical conventions, all of which are seen as essential to preserving its sacred function and ensuring ritual efficacy.

Table 5.

Thematic coding of interview data on the sacred function and traditional continuity of Teochew opera.

2.2. Teochew Opera in Secular Entertainment

Beyond ritual contexts, Teochew opera in Malaysia has increasingly been performed in secular cultural settings. This shift reflects the cumulative impact of national cultural policies aimed at fostering multicultural participation and heritage preservation.

The National Development Policy 1991 and Wawasan 2020 laid the groundwork by promoting economic expansion and encouraging cultural inclusivity. While primarily focused on economic growth, these policies indirectly enabled the flourishing of the arts by increasing government support for cultural infrastructure and festivals (Mauzy and Milne 2002). Opera troupes began participating in city-run events, community celebrations, and state-organised exhibitions, reaching broader and more diverse audiences. Corporate sponsorships and local government funding further expanded performance opportunities beyond temple grounds. The introduction of the National Heritage Act 2005 formalised the state’s commitment to cultural protection by providing legal mechanisms for the safeguarding of both tangible and intangible heritage (Mustafa and Abdullah 2013). Although Teochew opera has not yet been officially recognised under the act, the inscription of other Chinese cultural forms, such as the lion dance and the twenty-four festive drums, has inspired opera practitioners and validated their preservation efforts. Since then, opera performances have become more visible at official cultural events and public festivals, often framed as representative of Chinese Malaysian heritage. More recently, the Malaysian National Cultural Policy (DAKEN 2021) has further encouraged the integration of minority cultural practices into national narratives. While reaffirming the centrality of national identity, this policy explicitly supports cultural diversity, sustainability, and heritage innovation (The Government of Malaysia’s Official Portal 2021). Under this policy, Teochew opera has received increased support through collaborations with heritage institutions, tourism programmes, and educational initiatives. Its inclusion in government-funded cultural programming has widened its presence in secular performance spaces such as urban theatres, cultural parks, and community halls, as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Teochew opera performance at an arts festival. (Photo by the author, 2023).

Figure 7.

Teochew opera performances in official cultural events. (Photo by the author, 2023).

Table 6 presents selected interview data that reflect the evolving dynamics of Teochew opera in contemporary secular settings. As the art form transitions from its traditional ritual context into state-sponsored and public cultural platforms, practitioners have adopted a range of adaptive strategies. These include the structural condensation of performances, the integration of subtitles for wider accessibility (as shown in Figure 8), and the incorporation of local narratives and musical elements (as shown in Figure 9). Significantly, interview data indicate a thematic shift in repertoire: whereas ritual performances traditionally focused on divine supplication or exorcistic functions, secular performances increasingly foreground Confucian and communal values such as filial piety, heroism, loyalty, and justice, as shown in Table 7. These moral themes not only align with national multicultural ideals but also resonate with broader, multi-ethnic audiences. The narratives are now framed less as sacred offerings and more as cultural showcases that promote shared ethical ideals. Such shifts suggest that Teochew opera, while maintaining its core aesthetic framework, is undergoing a process of selective modernisation, which reinforces its relevance within Malaysia’s plural cultural policy landscape and repositions it as a medium for cultural education and soft diplomacy.

Table 6.

Thematic coding of interview data on secular Teochew opera performance and transmission.

Figure 8.

Teochew opera performances in theatres use added subtitles to assist audiences from other ethnic groups in understanding the plot. (Photo by the author, 2023).

Figure 9.

Musicians attempt to incorporate diverse instruments in Teochew opera accompaniments. (Provided by Goh, 2023).

Table 7.

Content of Teochew opera performances in the secular context.

To address the pressing issue of generational transmission, Malaysian Teochew opera practitioners have increasingly turned to structured, institutional approaches to teaching. A significant development in this regard is the establishment of a heritage centre in Penang, initiated through collaboration with the Guangdong Teochew Opera Institute (as shown in Figure 10). The centre operates as a dedicated training facility offering systematic instruction in music, stylised performance techniques, and dialect pronunciation, while also serving as a resource hub for archiving teaching materials and experimenting with simplified musical notation. Crucially, the heritage centre promotes accessibility by welcoming learners across ethnic backgrounds, age groups, and language proficiencies (as shown in Figure 11). This inclusive approach not only broadens participation but also fosters intercultural understanding, positioning Teochew opera as a shared cultural resource within Malaysia’s plural society.

Figure 10.

Malaysia Teochew Opera Heritage Centre (马来西亚潮剧传承中心) was established in Penang in 2022. It is jointly organised by the Guangdong Chao Opera Institute (广东潮剧院) and the Penang Teochew Puppet and Opera House (潮艺馆). (Kwongwah 2022).

Figure 11.

Students from diverse backgrounds are learning Teochew opera at the Penang Teochew Puppet and Opera House (潮艺馆), which is the Teochew opera learning and heritage centre in Penang, Malaysia. (Provided by Goh, 2023).

In the course of participant observation, this study identified a notable shift in the performance model of Teochew opera within Malaysia’s secular context. Departing from the conventional “performer–audience” dichotomy that characterises traditional operatic presentations, contemporary stagings increasingly adopt a participatory performance framework. This emerging model reconfigures audience engagement by integrating spectators directly into the performative and educational dimensions of the event. Rather than positioning the audience as passive observers, participatory performances encourage active involvement through structured interaction, cultural learning, and embodied experience. This shift is particularly evident in government-sponsored performances and cultural festivals, where participatory strategies are intentionally embedded within the event design. Prior to the formal performance, audiences are often introduced to the symbolic language of Teochew opera via guided exhibitions (as shown in Figure 12), interpretative signage, or live demonstrations of key performative elements such as gesture, costume, or vocal techniques. These knowledge-sharing components not only facilitate a deeper understanding of the art form’s aesthetic codes but also broaden access for non-Teochew-speaking and multi-ethnic audiences.

Figure 12.

At the stage entrance, a small exhibition stand is typically set up where staff introduce the characters, props, and decorations featured in the Teochew opera performance. (Photo by the author, 2023).

Crucially, participatory performance extends beyond cognitive engagement to include embodied participation. As Figure 13 and Figure 14 show, post-performance workshops, interactive demonstrations, and hands-on costume experiences offer audiences the opportunity to physically engage with the material culture and performative techniques of Teochew opera. These activities serve pedagogical as well as affective functions, fostering cultural literacy while cultivating a sense of belonging and emotional resonance. For younger participants, in particular, this model provides a low-barrier entry point into a complex traditional art form that may otherwise appear distant or inaccessible. Through these participatory formats, Teochew opera becomes a dynamic site of cultural dialogue rather than a static display of heritage. The model’s inclusive orientation not only supports intergenerational transmission but also enhances the opera’s relevance in a plural and rapidly changing society. In doing so, it exemplifies a responsive mode of heritage performance that aligns with broader objectives of cultural sustainability and public engagement.

Figure 13.

Performers invite the audience to participate in the performance, learning the movements. (Photo by the author, 2023).

Figure 14.

Audiences from different ethnic groups experience Teochew opera costumes during the event. (Photo by the author, 2023).

3. Discussion

The research result reveals that the sustainability of Teochew opera in Malaysia is shaped by the interplay between institutional support and community-driven efforts. Government policies provide structural frameworks and resources, while local practitioners ensure cultural continuity through ritual observance and creative adaptation. This dual approach enables the opera to remain relevant in both sacred and secular spheres of Malaysian society. This study adopts the concept of “duality” to explain its developmental approach, which is the coexistence of two distinct, contrasting or complementary elements within a single entity or concept. It recognises two interconnected aspects without necessarily suggesting a separation or opposition (Le Boutillier 2008; Wei 1992).

The term “duality” aptly captures the coexistence and complementary nature of Teochew opera in different contexts. Although sacred and secular elements serve distinct purposes and contexts, they are interconnected and can influence each other without being strictly completely opposed or mutually exclusive. Schechner articulated this duality in the performance contexts. He suggested that in the sacred context, performance often serves as a conduit for expressing the divine, the spiritual, or the transcendent (Schechner 1994). Sacred performances are rooted in ritual, tradition, and the enactment of communal beliefs. In contrast, secular performances primarily focus on entertainment, aesthetic appreciation, or articulating individual or collective identities. The duality inherent in Teochew opera aligns with its adaptability within Malaysian performance contexts, serving diverse purposes, thereby ensuring its sustainability.

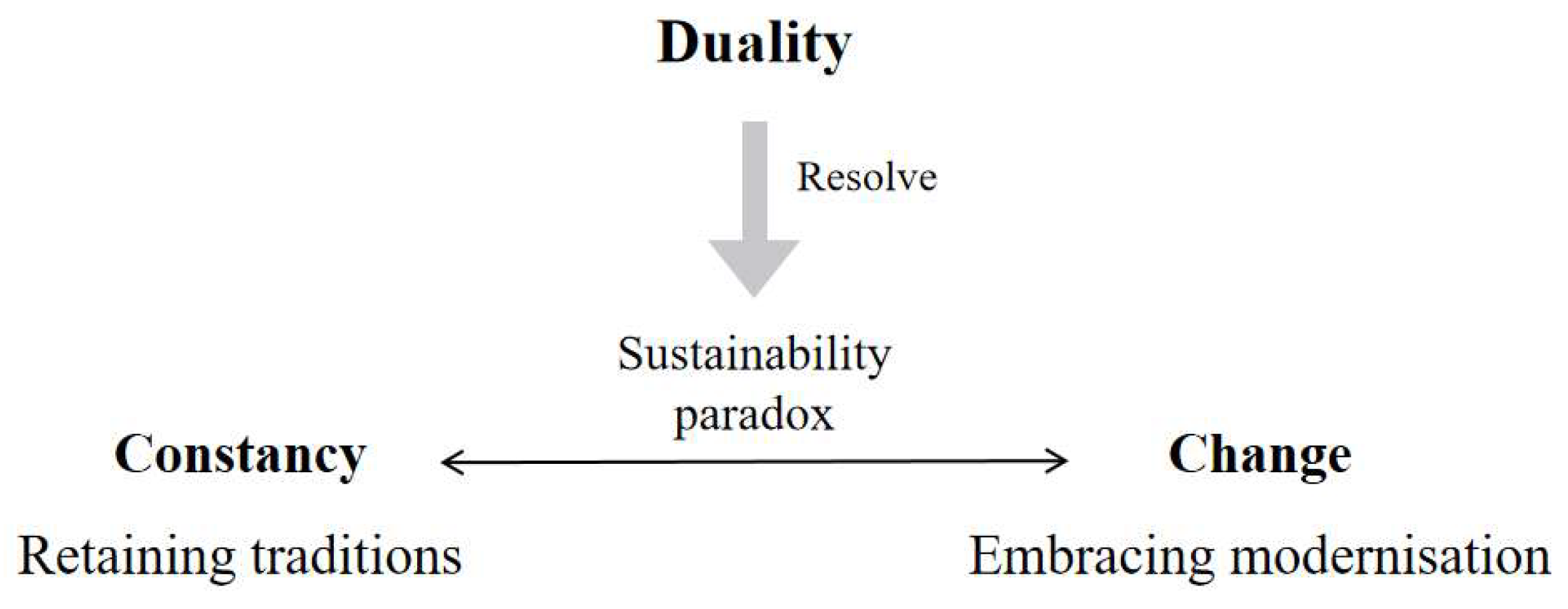

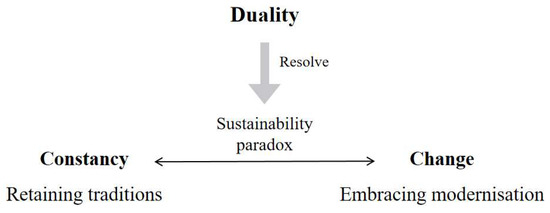

3.1. Duality Resolves the Paradox of Change and Constancy

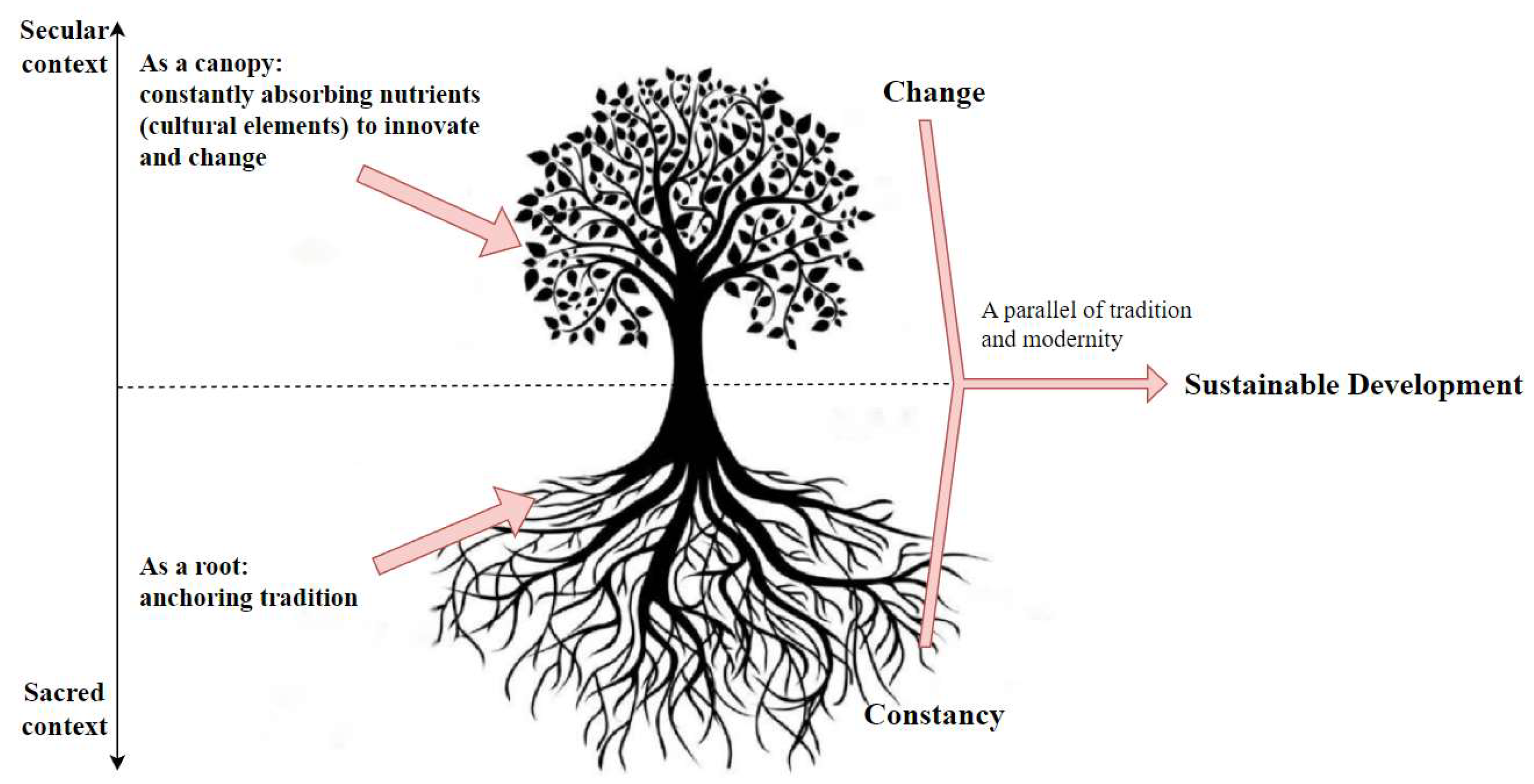

Teochew opera, as a cultural form, is dynamic; it necessitates ongoing development and adaptation while preserving core elements that ensure continuity and stability. The duality of Teochew opera’s development model in Malaysia addresses the paradox of cultural development as either change or constancy, as illustrated in Figure 15, and allows the preservation of tradition and the embrace of modernity to coexist, as shown in Table 8.

Figure 15.

The duality of Teochew opera allows traditional and modern elements to coexist. (Author’s own work).

Table 8.

The duality of sacred and secular in Teochew opera in Malaysia.

Teochew opera performances in rituals are defined by their periodicity, utility, and rich metaphors, aiming to create a mystical experience through choreographed movements, props, and sounds that symbolise a connection with the divine. Although the lyrics are often in dialect and may be incomprehensible, the audience is drawn by belief and curiosity, engaging deeply in devotion and prayer. Participants focus on auspicious symbols tied to their beliefs in ritualistic exorcism, with music playing a vital role in expressing these narratives and underscoring the community’s dedication to the deities to bestow blessings.

In a sacred context, Teochew opera is closely linked to traditional rituals that serve the beliefs of the Malaysian Chinese community. These rituals create a relatively closed environment where ritual elements remain immutable; any arbitrary changes would be considered sacrilegious, thereby preserving the tradition. The interplay between Teochew opera and rituals reinforces communal identities and protects the community’s spiritual heritage. Typically, performances focus on gods and ancestor worship, granting profound significance to each show. In this situation, Teochew opera, as an intangible offering, on the one hand, achieves appeasing the gods in exchange for favours. On the other hand, performances satisfy audience expectations through impersonation, as actors don costumes and makeup to portray gods or historical figures. These functions ensure its continuity in the community.

Teochew opera maintains resistance to change in ritualistic performances, which are viewed as vital to preserving tradition within the Chinese community in Malaysia. Rituals are inherently conservative, affirming community values and social structures (Turner 1998). During rituals, Teochew opera acts as worship and divine communication. Therefore, ritualistic performances often resist modernisation precisely because their power lies in their ability to repeat and re-enact tradition, fostering a sense of continuity across generations (Stephenson 2015). Furthermore, the aesthetic of tradition in Teochew opera is highly valued in ritual contexts. Performance is assessed by its fidelity to established forms rather than innovation. Adhering to traditional narratives, music, and styles reflects skill and reverence, not stagnation. The Malaysian Chinese community regards these elements as vital embodiments of their culture, meant to be preserved in their original form.

In contrast, in a secular framework, Teochew opera enriches itself by incorporating elements from various cultures within Malaysia’s multicultural landscape, appealing to diverse backgrounds (Lindberg 2018), an adaptation which revitalises Teochew opera in cultural festivals and theatres. Two main forces drive this innovation: the Malaysian government’s multiculturalism policy, which enables exchanges between Teochew opera and other local cultural traditions, and internal efforts within the Chinese community. Contributions from performers, cultural practitioners, businessmen, and associations promote sustainable development. These cultural events allow Teochew opera to highlight Chinese culture, fostering pride among Malaysian Chinese while promoting cultural exchanges and advancing multicultural development across ethnic groups.

In secular contexts, Teochew’s opera shows a notable receptiveness to innovation, which is vital for its sustainability and relevance in a rapidly modern world. This adaptability does not compromise its traditional essence; instead, it exemplifies a dynamic cultural practice that retains its core identity while evolving with external influences. Core elements like costuming, classic scripts, and performance techniques remain unchanged. Additionally, it has embraced local Malaysian narratives and instruments from other ethnic groups, such as Malays and Indians. Teochew opera prioritises enhancing music and performance quality, appealing to audiences more effectively than ritual performances, which are often less focused on aesthetic experience. The increasing demand for melodious music, exceptional acting, and sophisticated stagecraft means only performances embodying these qualities gain recognition. These innovations in Teochew opera engage younger generations, broadening its audience and fostering cultural exchange among Malaysia’s ethnic groups, ensuring it remains a living tradition rather than a static cultural heritage.

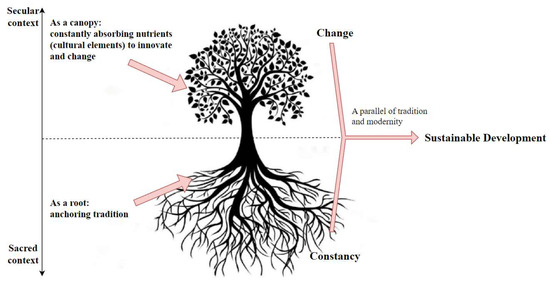

The duality of the sacred and the secular in Teochew opera is a fundamental basis for its sustainable development. This interplay can be visualised as a tree, as shown in Figure 16. The sacred aspect is the root of stability, which anchors the tradition in rituals and communal belief, ensuring continuity and reverence for its cultural heritage within the Malaysian landscape. Conversely, the secular aspect represents the canopy, which constantly absorbs nutrients (cultural elements) to innovate and change, allowing the art form to adapt and resonate with broader audiences. Thus, this duality preserves the opera’s integrity and enhances its relevance within a modern cultural landscape.

Figure 16.

The duality of Teochew opera is visualised as a tree. (Author’s own work).

3.2. Risks and Challenges to Sustainability

While the duality of sacred and secular performance has enabled Teochew opera to endure in Malaysia’s multicultural society, its long-term sustainability is shaped by several interrelated challenges. These stem from internal limitations within the tradition and external structural constraints, particularly regarding policy support, public engagement, and generational transmission.

Within ritual contexts, Teochew opera has retained its traditional essence through ritualised performances. However, the preservation is largely symbolic rather than holistic. Opera troupes often rely on a narrow set of ritualised plays due to the declining mastery of traditional scripts and music scores. The absence of critical spectatorship—given that the performance is directed towards deities rather than human audiences—limits artistic refinement. This setting may inadvertently foster indifference to performance quality, especially when payments are guaranteed and audience feedback is minimal. As such, while ritual performance sustains cultural relevance within the community, it risks becoming stagnant or passionless over time.

In secular contexts, although government-led cultural programmes and public festivals have provided new platforms, the sustainability of such initiatives remains precarious. Funding is often temporary or tied to short-term events, while long-term investment in talent development, venue infrastructure, and digital outreach remains limited. Moreover, intergenerational transmission is constrained by the perceived lack of professional pathways for young performers, compounded by limited instructional resources and inconsistent training models.

To summarise these dynamics, Table 9 outlines key risk categories identified during fieldwork and interviews, linking them to their sources and potential consequences for the art form’s sustainability.

Table 9.

Key risks to the sustainable development of Teochew opera in Malaysia.

While these risks do not necessarily indicate an impending decline, they suggest areas where caution, reflexivity, and cultural sensitivity are required. The success of Teochew opera’s dual framework depends not only on expanding its public appeal but also on maintaining its internal integrity as a living, evolving heritage. Effective safeguarding requires a balance between innovation and preservation, guided by both institutional foresight and community agency. Recognising these challenges can help practitioners and policymakers alike to develop more robust, context-sensitive models for the long-term sustainability of Teochew opera in Malaysia.

3.3. Future Development Recommendations

To ensure the long-term sustainability of Teochew opera in Malaysia, this study proposes a series of practical and culturally grounded recommendations. These are informed by fieldwork findings, interviews with practitioners, and current gaps in policy and infrastructure. Rather than treating challenges as limitations, the following proposals frame them as opportunities for innovation, collaboration, and institutional development.

First, greater integration between sacred and secular performance contexts would enhance both public engagement and cultural understanding. At present, ritual performances tend to be isolated from wider audiences, while secular events often lack depth in conveying the opera’s symbolic meaning. A more integrated model can be developed where secular performances include brief educational segments that explain the ritual origins of specific plays, roles, or costumes. Similarly, ritual events could introduce accessible presentation tools such as guided narration or bilingual programme notes. This cross-pollination between formats would not only support audience comprehension but also reinforce the opera’s historical significance and aesthetic richness.

Second, the interest shown by younger generations must be met with concrete pathways for long-term involvement. While informal learning opportunities currently exist, the absence of clear professional routes has limited the appeal of Teochew opera as a career. Establishing structured training frameworks is vital. These might include formal certification programmes, tiered progression systems from amateur to professional levels, and paid apprenticeship schemes with experienced performers. Partnerships with the Guangdong Teochew Opera Institute already offer a promising model; such collaborations could be expanded to develop standardised curricula and joint training centres in Malaysia.

Third, a coordinated effort is needed to achieve formal recognition of Teochew opera as part of Malaysia’s national intangible cultural heritage. Although several other Chinese art forms have received official listing, Teochew opera remains unrecognised, which affects its visibility and access to state funding. Practitioners and scholars could establish an advocacy group or representative body to spearhead heritage application efforts. This would involve documentation of performance practices, oral histories, costume archives, and musical notation, submitted as part of an application to the relevant heritage authorities. Recognition would also enable the appointment of official cultural bearers, opening pathways for funding and institutional support.

Fourth, embedding Teochew opera into the national education system would significantly strengthen its transmission. Primary and secondary schools could host co-curricular activities or arts appreciation classes featuring Chinese opera, supported by age-appropriate learning materials. Meanwhile, universities could develop elective courses or research-based modules within performing arts or cultural heritage programmes. These initiatives would expose students from different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds to Teochew opera, fostering intercultural respect while ensuring broader generational reach. Collaboration with the Ministry of Education and local school councils would be essential to realise these efforts in a sustainable and inclusive manner.

Collectively, these recommendations reflect a comprehensive strategy for revitalising Teochew opera through adaptive performance practices, vocational development, policy recognition, and educational integration. When implemented in alignment with the needs and aspirations of the practitioner community, these initiatives can ensure the sustainable development of Teochew opera as a vibrant living heritage, securing its firm place within Malaysia’s multicultural future.

4. Materials and Methods

This study employs a qualitative ethnographic approach to investigate the resilience and sustainability of Teochew opera in Malaysia. Fieldwork involved participant observation of ritual and secular performances, rehearsals, and festivals; in-depth interviews with performers, organisers, and audiences; and the collection of visual and archival materials. These methods offer a situated understanding of how the opera endures and adapts within a multicultural context.

The analysis integrates cultural resilience and cultural sustainability to examine how traditional practices respond to external pressures while maintaining continuity. Resilience denotes the opera’s ability to adapt to shifting sociocultural and economic conditions without compromising its core identity (Frigotto and Frigotto 2022), while sustainability refers to its long-term viability through intergenerational transmission, institutional relevance, and evolving meaning (Roca et al. 2021). Viewed together, these concepts reveal how the holders of Teochew opera negotiate change while securing its cultural future.

4.1. Research Sites and Duration

The fieldwork for this study spanned from November 2022 to December 2023, encompassing a full calendar year to capture the temporal rhythms and sociocultural dynamics that shape the sustainability of Teochew opera in Malaysia. This extended duration enabled observation of various performances across sacred and secular contexts, including temple celebrations, deity birthdays, ancestral rituals, and multicultural festivals. Such immersion facilitates familiarity and trust-building, while also revealing culturally sustainable approaches from both insider and outsider perspectives.

Research was conducted in two key sites, Penang and Kuala Lumpur, where Teochew opera remains actively practised. In Penang, the opera remains closely tied to ritual and religious festivals, sustained by longstanding clan associations and temple patronage, such as the Penang Teochew Association and the Kuala Lumpur Teochew Federation, as well as the Kwun Yin Temple and the Xuantian God Temple. These settings allowed in-depth observation of how ritual performance protocols reinforce continuity and traditional authority. In contrast, Kuala Lumpur provided a vantage point on the opera’s adaptive strategies in pluralistic public spaces, where it is increasingly performed in state-sponsored and cross-cultural events. These performances foreground innovation, aesthetic flexibility, and cultural recontextualisation. Together, the two sites reflect the dual identity of Teochew opera as both a tradition and an evolving cultural practice—an essential tension at the heart of its sustainable development in modern Malaysia.

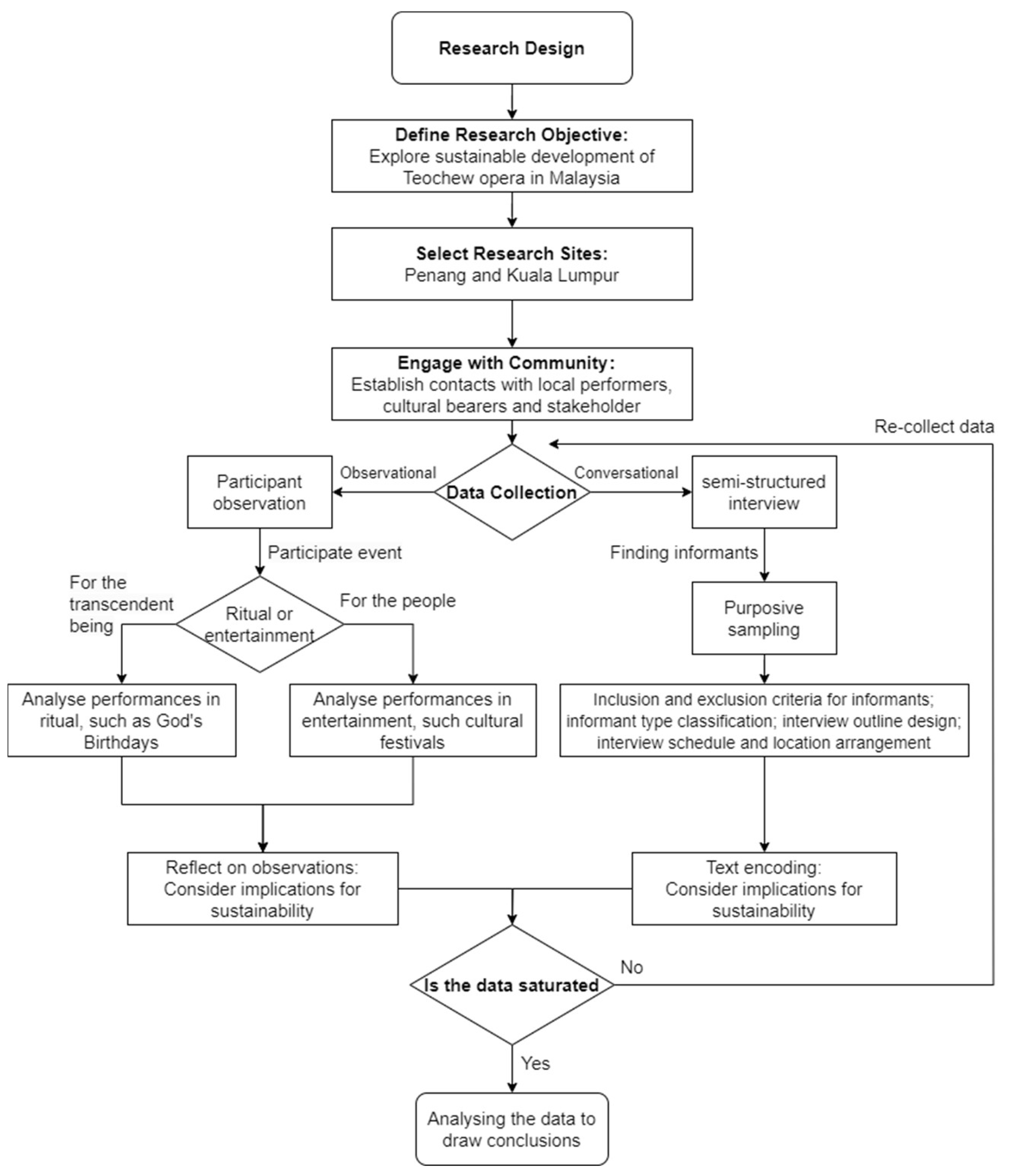

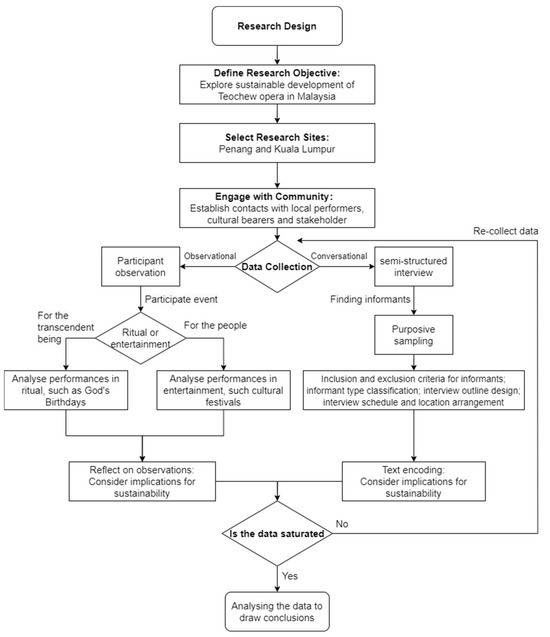

4.2. Data Collection Methods

Data was collected using participant observation and semi-structured interviews, as shown in Figure 17. These methods were selected to complement each other, providing a comprehensive view of how Teochew opera is sustained within the Malaysian context.

Figure 17.

Research flow chart. (Author’s own work).

Participant observation was the primary data collection method used in this study. As a method grounded in interpretivist qualitative research, participant observation enables the researcher to engage directly with the daily realities of cultural life, offering insight into observable behaviours and the underlying meanings that shape them (Denzin and Lincoln 2011). Its use in this study is particularly suited to investigating how Teochew opera maintains its cultural continuity while adapting to contemporary social, political, and aesthetic pressures, which is a core concern within the broader discourse on cultural sustainability. This method was conducted across a variety of settings, each offering distinct insights into how the art form operates within both traditional and contemporary cultural frameworks. The main contexts of observation are outlined in Table 10.

Table 10.

Occasions for participant observation.

The researcher took detailed field notes in both settings and used photography and audio recordings (with participant consent) to document the performance environments, dialogues, and audience responses. A reflexive journal was also maintained to record methodological decisions, interpretive insights, and shifts in understanding over time. This dual-site observational strategy enabled a comprehensive analysis of how Teochew opera navigates continuity and change across its ritual and representational expressions, aligning directly with the study’s objective of examining cultural sustainability through the lens of practice.

In addition, semi-structured interviews were used to supplement participant observation, providing diverse perspectives essential for understanding the sustainable development of Teochew opera. As shown in the Table 11, the selection of informants was guided by predetermined criteria designed to ensure comprehensive representation of the various stakeholders involved in the practice of Teochew opera. These categories included performers, organisers, scholars, and audiences, each offering a unique viewpoint on the sustainability of the art form. Performers were selected based on their extensive experience, as their insights are crucial for understanding the internal dynamics of performance and the challenges of maintaining tradition. Organisers were included for their role in facilitating the opera’s presentation and ensuring its accessibility to broader audiences. Scholars were chosen for their academic expertise on cultural sustainability and traditional art forms. Finally, audience members from various generational and ethnic backgrounds were selected to gauge the opera’s reception and cultural significance. Purposive sampling was initially employed to identify key informants, such as senior performer Ling Goh, and snowball sampling was subsequently used to expand the pool of informants, ensuring a rich diversity of perspectives on the topic.

Table 11.

Inclusion criteria, type, and number of informants.

In this study, 20 informants were interviewed, each lasting between 60 and 90 min. The question encompasses multiple dimensions, including the performance structure of Teochew opera, preservation strategies, the influences of modernity, and the roles of government and community in supporting cultural heritage. The interviews were audio-recorded, then transcribed verbatim and thematically analysed to identify recurring themes and patterns relating to sustainable approaches of Teochew opera in Malaysia.

5. Conclusions

The example of Teochew opera in Malaysia illustrates its sustainability by maintaining inherent duality, a concept in cultural studies that addresses change and invariance in cultural development. This duality recognises that cultures are dynamic and ever-evolving while preserving core elements that provide continuity. Regarding Teochew opera in a sacred context, local beliefs and customs support cultural roots, ensuring its stability within Malaysia’s multicultural landscape. Conversely, the secular aspect of duality rejuvenates Teochew opera, fostering modernity and engaging audiences through multicultural exchanges.

Duality presents two perspectives on cultural sustainability. Cultures change due to internal factors, such as individual innovations, and external influences, including interactions with other cultures and technological advancements. These changes result in the evolution of certain cultural elements. Invariance is the persistence of fundamental aspects that maintain a culture’s distinct identity. Core values, traditions, and social structures are stability anchors amidst evolving aspects.

Maintaining this duality is helpful for cultural sustainability. This coexistence allows cultures to adapt without losing their inherent characteristics, ensuring they respond to contemporary challenges while reflecting historical roots. This dynamic interplay ensures that cultures are not static but are living, evolving entities that can respond to contemporary challenges while still reflecting their historical and cultural roots. Recognising this duality provides a nuanced understanding of cultural development, highlighting the complexity of traditional cultures as adaptable entities. For example, traditional music or dance can be preserved by maintaining a traditional habitat, while simultaneously innovating in another context to adapt to contemporary performances. Such initiatives demonstrate cultural practices’ potential to evolve in response to global influences without losing their essence. This approach encourages broader participation, attracting traditionalists and innovators, enriching cultural discourse, and ensuring comprehensive cultural sustainability. This way, traditional cultures can navigate today’s challenges while maintaining unique identities and continuity with their roots, achieving sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and M.F.A.; methodology, Z.L.; software, Z.L.; validation, Z.L. and M.F.A.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, Z.L.; resources, Z.L.; data curation, Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L. and M.F.A.; visualization, Z.L. and M.F.A.; supervision, M.F.A.; project administration, Z.L.; funding acquisition, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study involved interviews and has received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee for Research involving Human Subjects Universiti Putra Malaysia, Approval Ref: JKEUPM-2022-897.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all participants in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cohen, Erik. 1988. Authenticity and Commoditization in Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 15: 371–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, Norman K., and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. 2011. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Frigotto, Maria Laura, and Francesca Frigotto. 2022. Resilience and Change in Opera Theatres: Travelling the Edge of Tradition and Contemporaneity. In Towards Resilient Organizations and Societies. Public Sector Organizations. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 223–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, David. 2009. Fakesong in an Imagined Village? A Critique of the Harker–Boyes Thesis. Canadian Folk Music/Musique Folklorique Canadienne 43: 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hafstein, Valdimar Tr. 2008. Intangible Heritage as a List: From Masterpieces to Representation. In Intangible Heritage. London: Routledge, pp. 107–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Hailing. 2005. The Circulation and Development of Teochew Opera in Malaysia [潮剧在马来西亚的流传与发展]. The Arts [艺苑] Z: 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. 2004. Intangible Heritage as Metacultural Production. Museum International 56: 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwongwah. 2022. Available online: https://www.kwongwah.com.my/20220509/%E6%BD%AE%E8%89%BA%E9%A6%86%E4%B8%8E%E5%B9%BF%E4%B8%9C%E6%BD%AE%E5%89%A7%E9%99%A2%E5%90%88%E5%8A%9E-%E9%A9%AC%E6%9D%A5%E8%A5%BF%E4%BA%9A%E6%BD%AE%E5%89%A7%E4%BC%A0%E6%89%BF%E4%B8%AD%E5%BF%83/ (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Lai, Binh. 1993. An Overview of Chinese Theatre in Southeast Asia [东南亚华文戏剧概观]. Beijing: China Theatre Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Law, Yi-Xian. 2016. Teochew Opera in Malaysia: Local Performance Practice and Issues of Sustainability. Bachelor’s thesis, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. [Google Scholar]

- Le Boutillier, Shaun. 2008. Dualism and Duality: An Examination of the Structure-Agency Debate. London: School of Economics and Political Science. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Alvin Eng Hui. 2021. Technologies of the Hungry Ghosts and Underworld Gods. Performance Research 26: 133–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, Malin. 2018. Relating Inclusiveness and Innovativeness in Inclusive Innovation. International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development 8: 103–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Hongjuan. 2010. Pushing Rather Than Supporting: An Exploration of the Roles of Government and Experts in Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage within Traditional Theatre [推手而不是扶手—传统戏剧类非遗保护中政府, 专家的角色探论]. Theatre Literature [戏剧文学] 8: 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Kun, and Yuan Chen. 2009. The Survival Status and the Way Out of Chinese Teochew Opera [中国潮剧的生存现状与出路]. Journal of Shenzhen University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition) 26: 157–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mauzy, Diane K., and R. S. Milne. 2002. Malaysian Politics Under Mahathir. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, Nurulhuda Adabiah, and Nuraisyah Chua Abdullah. 2013. Preservation of Cultural Heritage in Malaysia: An Insight of the National Heritage Act 2005. Available online: http://eprints.usm.my/id/eprint/35031 (accessed on 9 June 2017).

- Pan, Nian Ying. 2005. Re-examination of the Suojia Shengtai Museum [梭戛生态博物馆再考察]. Theory and Contemporary [理论与当代] 3: 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Roca, Mercè, Jaume Albertí, Alba Bala, Laura Batlle-Bayer, Joan Ribas-Tur, and Pere Fullana-i-Palmer. 2021. Sustainability in the Opera Sector: Main Drivers and Limitations to Improve the Environmental Performance of Scenography. Sustainability 13: 12896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechner, Richard. 1994. Ritual and Performance. In Companion Encyclopedia of Anthropology. London: Routledge, pp. 613–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, Barry. 2015. Ritual: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Elynn, and Sergio Camacho Fernandez. 2023. The Chinese Orchestra Cultural Ecosystem in Malaysia: Hybridisation, Resilience and Prevalence. Journal of Creative Industry and Sustainable Culture 2: 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, Daniel Sampaio, Fernando Brandão Alves, and Isabel Breda Vásquez. 2021. The Relationship between Intangible Cultural Heritage and Urban Resilience: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 13: 12921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Government of Malaysia’s Official Portal. 2021. Dasar Kebudayaan Negara 2021 (DAKEN-2021-2). Available online: https://www.pmo.gov.my/2021/10/dasar-kebudayaan-negara-2021-daken-2021-2/#pll_switcher (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Throsby, David. 2019. Heritage Economics: Coming to Terms with Value and Valuation. In Values in Heritage Management: Emerging Approaches and Research Directions. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, pp. 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor Witter. 1998. From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. New York: Performing Arts Journal Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Hanwu. 2007. Reflections on the Protection and Inheritance of Teochew Opera [对潮剧保护传承的思考]. Guangdong Art [广东艺术] 6: 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Li. 1992. The Duality of the Sacred and the Secular in Chinese Buddhist Music: An Introduction. Yearbook for Traditional Music 24: 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Guoqin. 2015. A History of Teochew Opera (Volume 1) [潮剧史 (上)]. Guangzhou: Hua Cheng Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Yihong. 2015. 试论潮剧的传承与保护 [An Experimental Discussion on the Inheritance and Preservation of Teochew Opera]. Theatre House [戏剧之家] 8: 59–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Qinghui. 2020. The Importance, Specificity and Effectiveness of Teochew Opera Inheritance and Preservation [潮剧传承与保护的重要性, 具体性及实效性分析]. Theatre House [戏剧之家] 21: 56–57. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).