Shades of the Rainbow Serpent? A KhoeSan Animal between Myth and Landscape in Southern Africa—Ethnographic Contextualisations of Rock Art Representations

Abstract

:1. Introduction: on the Presence of Snakes in Southern African Rock Art1

- snakes could “fill the country with water” (p. 5);

- snakes, health and healing are entwined, such that ill-health is associated with dangerous snake potency, and healing—via the ministrations of a healer who is also snake-like—is akin to the emergence of a new state following shedding of the skin of a snake;

- snake fat is a potent substance that when applied to a healer (p. 7) can facilitate their transformation into the snake-associated and potent altered state of perception needed for healing to occur;

- the use of “charms”, i.e., potent substances, that include “burnt snake powder” (p. 10) both strengthens trance-states (p. 10) (associated with being snake-like), and supports healers in their return to the everyday consciousness of “normal” human-being (p. 7);

- “rhebok men”, supported by charms and the healing trance dance, are those who could tame and catch eland and snakes (p. 10).

2. The Present and the Past: on Ethnographic Analogy and Archaeological Interpretation in Southern African Rock Art

3. Triangulating a KhoeSan “rainbow snake assemblage” from rock art and ethnography

3.1. Snakes could “fill the country with water”

3.2. Ill-Health Is Caused by Dangerous Snake Potency; Healing is a Transformative Emergence Signalled by the Shedding of a Snake Skin. Snake Potency thus can be both “Good” and “Bad”

… the chief and his young men were saved (from the wall of water described in 3.1 above)... and Cagn sent Cogaz (his son) for them to come and turn from being snakes, and he told them to lie down, and he struck them with his stick, and as he struck each the body of a person came out, and the skin of a snake was left on the ground, and he sprinkled the skins with canna,10 and the snakes turned from being snakes, and they became his people ([3]p. 5).

3.3. Snake Fat is a Potent Substance that can Facilitate Transformation of a Healer into the Snake-Associated Potency through Which Healing can Occur

those men took fat from a snake they had killed and dropped it on the meat (a rhebok), hunted by Qwanciqutshaa, another son of Cagn, who was hated by these young men (because they desired his wife), and when he (Qwanciqutshaa) cut a piece and put it in his mouth it fell out; and he cut another, and it fell out; and the third time it fell out, and the blood gushed out of his nose (signalling entrance into an altered state of consciousness). So he took all his things, his weapons, and clothes, and threw them into the sky, and he threw himself down into the river... (where) he turned into a snake (p. 7).

3.4. The Use of “Charms”, i.e., Potent Substances, Including “Burnt Snake Powder” ([3],p. 10) both Strengthens Trance-States ([3], p. 10) (Associated with being Snake-Like) and Supports Healers in Their Return to the Everyday Consciousness of “Normal” Human-Being ([3], p. 7)

made a hut and went and picked things and made cannā, and put pieces in a row from the river bank to the hut. And the snake (i.e., Qwanciqutshaa in his transformed trance state) came out and ate up the charms, and went back into the water, and the next day she did the same; … And when the girl saw he had been there she placed charms again, and lay in wait; and the snake came out of the water and raised his head, and looked warily and suspiciously round, and then he glided out of the snake’s skin and walked, picking up the charm food... ([3], p. 7).

Some fall down; some become as if mad and sick; blood runs from the noses of others whose charms are weak, and they eat charm medicine, in which there is burnt snake powder. When a man is sick, this dance is danced round him, and the dancers put both hands under their arm-pits, and press their hands on him, and when he coughs the initiated put on their hands and received what has injured him ([3], p. 10, emphasis added).

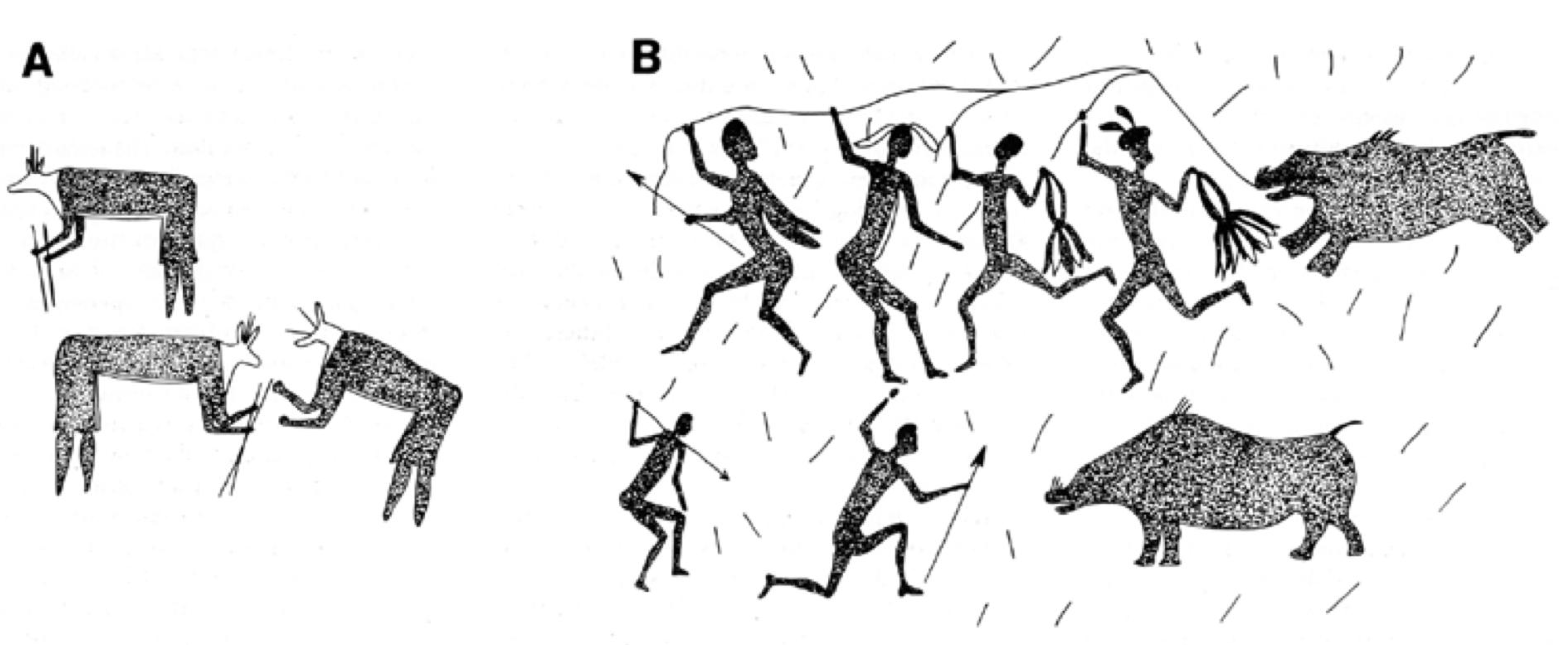

3.5. Rhebok Men, i.e., Men with the Heads of Rhebok (cf. Figure 1a), Lived Mostly under Water (i.e., Indicating Their Submerged Trance State) and, with the Assistance of “Charms” (see 3.4. above) and Riems (Pliable Ropes of Leather) could Tame and Catch Eland and Snakes ([3], p. 10)

the paintings from the cave Mangolong represent rainmaking. We see here a water thing, or water cow... They then charm the animal, and attach a rope to its nose,—and in the upper part of the picture it is shown as led by the Bushmen, who desire to lead it over as large a tract of country as they can, in order that the rain should extend as far as possible,—their superstition being that wherever this animal goes, rain will fall. The strokes indicate rain. Of the Bushmen who drag the water cow, two are men (sorcerers), of whom the chief one is nearest to the animal. In their hands are boxes made of tortoise (!khu) shell (containing charmed boochoo)… 15

4. Conclusion—What an Extraordinary Snakey World We Live in...

Acknowledgments

Endnotes

- 1We first presented this paper in June 2009 as “Shades of the rainbow serpent: a KhoeSān animal between myth and landscape in Southern Africa’, at the Conference Living Landscapes, Aberystwyth University.

- 2Challis et al. ([5], p. 1) say the only time. We know of at least one other occasion. The South African archaeologist Revil Mason visited rock art sites on the Brandberg/Dâures, Namibia, in 1995 with San people from Botswana’s Kuru Arts project (http://www.kuruart.com/). They visited and spent a night at Snake Rock shelter in the Upper Hungorob. Unfortunately, no enquiry was made as to what the San artists from Kuru thought of the rock art in the shelter. It seems, however, that the art did provoke a significant response. That night the San artists danced, sang, clapped and no doubt tranced all night at the shelter, suggesting that they were moved to do so by their connection with the content of the art (Revil Mason, personal communication to Sullivan, 2009; and Andrew Botelle, personal communication).

- 3Nb. The consecutive ordering of these themes in Orpen’s 1874 text may be an artefact of the way he pieced Qing’s narrative together, i.e., rather than reflecting the order in which Qing related these stories.

- 4Nb. Differing views existing regarding the frequency of the appearance of snakes in southern African rock art, with one reviewer of this paper noting that on the basis of 16 years’ fieldwork, snakes are a relatively common rupestrian motif. They certainly tend to feature relatively prominently when they do appear in this context.

- 5By “onto-epistemology’ we mean reasoned knowledge flowing from particular cultural and historically situated assumptions regarding the nature of reality, and the methods through which, given these assumptions, it is possible to know this. We derive the term “onto-epistemology’ from [18].

- 6We use neologisms “socionature’, “culturenature’ and “ecocultural’ to emphasise an onto-epistemology in which “social’ and “natural’ realms are entangled and muturally constitutive rather than distinct and separate (cf. [57,58,59], [60], p. 27). Such an approach seems to us to be well attuned to our focus in this paper, given what we understand as KhoeSan appreciations of such entanglements.

- 7Following [67], for terms in Khoekhoegowab a full-stop is used to demarcate the word stem from the male, female and plural markers .b, .s . and .n or .i respectively.

- 8Strictly speaking the term “buchu’ indicates a particular aromatic species known to the settlers in South Africa (Agathosma betulina), but is frequently used as a designation for an aromatic powder used by KhoeSan throughout southern Africa and made from a mixture of aromatic plant parts from a number of species (cf. [30,69]).

- 9Termed“/awi!nana.b’, literally “falling-/rain-colours’, by Sesfontein Damara (Sullivan personal fieldnotes).

- 10Probably leaves and stems of Sceletium spp., (according to analysis by [73], pp. 43-46).

- 11Thus some Khoe-speaking Naro [13], influenced by European missionary thinking, consider that the snake tongue stings in ways reminiscent of lightning and also that the split in the tongue exists because snakes are associated with the side of their deity that does not always speak the truth.

- 12See [13] for a fuller discussion of KhoeSan praxes in relation to generating immunity.

- 13Nb. drawing on the /Xam archive and Ju/’hoan ethnography, Challis ([72], p. 17-19) argues that the notion of taming snakes does not equate to wider ideas of possessing the potency of a snake, eland or another animal, but simply to the “luck” of having “influence’ over snakes. Our own ethnographic research, however, indicates that the way people have influence over the weather and animals is by being in intentional relationship with them and thereby sharing a kind of kinship with them. In this sense “taming” fits within a wider family of ideas that include ideas of “possessing”, “owning” or “working with” certain animals and/or the rain, as well as with the notions of “luck” that Challis links to ideas of “influence” and decouples from potency acquired through directed action and intent (discussed further in [82]).

- 14Although this idea has received some prominence in the literature, the majority of references are to one claim made by a Ju/’hoansi man interviewed by Biesele. This specific description is absent in the authors’ experience (particularly in Low’s research on the healing trance dance). This absence suggests the expression may be more idiosyncratic than representative, and should be treated with some caution as an interpretative metaphor in rock art. It is notable that Biesele ([31], p. 70-72) in fact introduces this story as an example of the role of idiosyncrasy in accounts of Ju/’hoan trance journeys. Although the term might be used by dancers, in the authors’ experience it seems less a specific reference to “trance’ and more an indicator of when the normal order of life is messed up and boundaries become unclear in ways that might also be dangerous or unpleasant. In Khoekhoegowab, overlaps between gao, meaning rotting, decay, musty smelling, gao-gao-aob, meaning spoiler or corrupter, and gaogaosib, meaning ruined and spoiled state ([89], p. 249), thus may give better indication of the wider context of the broader uses of the term “spoilt’ than that emphasized in rock art analysis. Sugawara ([90], p. 94) makes a similar observation amongst the Gui and Gana Bushmen for whom the term !năre carries the multiple meanings of to be drunk, to sense and to have a hunch. Brody ([91], p. 239-242) among others has also argued that native American enthusiasm for alcohol might be based on a cultural embrace of the value of altered states of consciousness, an argument that might be pertinent to KhoeSan contexts where alcohol has a close, if problematic, relationship with many healers. One of us (Low) recently observed a not untypical but extreme example of this relationship when a Ju/’hoansi healer proclaimed that he needed to drink a crate a beer before he could commence healing. He described this requirement as his special technique.

- 15Small tortoise shells from young tortoises are used by KhoeSan for storing sâ.i (e.g. Sullivan, personal observation for Damara and Ju/’hoan San). The powdered mixture of aromatic plants that they thereby contain is strongly associated with menarche, menstrual blood, and with female life-giving power [30], but is also used to support (normally male) healers as they direct their will towards entering the primal, mythological world associated with trance and the ancestors (see 3.4, also [87]). The relationship between blood and women is developed in a metaphorical string that results in a tortoise becoming a metaphor for a woman’s genitals and having sex, and tortoise shells thereby being seen as able to cleanse menstrual blood. At the same time, the /Xam described tortoises and snakes as “rain things”, denoting a sense of mutuality (cf. Bleek-Lloyd-/Xam archive). So, for example, both tortoises and snakes are observed to head for high ground when it rains. Thus there is an association of potency here between rain, snakes, tortoises, menarche, menstrual blood, and sâ.i, affirmed etymologically through the Nama term written by Theophilus Hahn as au.b to describe “snake”, “the one who flows” and blood, as well as to bleed—“au”, and rain—“au-ib” ([92], pp. 78-9).

- 16Associated by /Xam informants with the embodiment of !Khwa as rain, water in waterholes, eland, rain bull, rain animal and attracted to secluded menarcheal females, see summary in Solomon ([12], p. 5).

- 17See http://travel.nationalgeographic.co.uk/travel/world-heritage/chichen-itza/ accessed 22 January 2013.

- 18An anecdote serves to illustrate this point. When we presented this paper at the Living Landscapes conference in 2009 (see endnote 1) Low made an unrehearsed reference to being told by a San healer that the most potent things to see in a healing ceremony were the snake, the cat and lightning. This provoked an interjection from Sullivan, who not long previously had returned from a short period of fieldwork with ayahuasca healers in Ecuador and Peru. In one of the ceremonies in which she participated the healer, Don Lucho, introduced the medicine by saying: “of the things you may see three are the most potent for healing. They are the snake, the cat and lightning’ (Sullivan, personal fieldnotes, 2008).

- 19The particularly constructed nature of this interpretation of the serpent in Genesis is indicated by records that second-century Gnostics worshipped Jesus “as the perfect serpent’ who celebrated dance as the way of knowing life: thus, “who dances not knows not the way life’ (in [100], p. 606).

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. McGranaghan, S. Challis, and J.D. Lewis-Williams. “Joseph Millard Orpen’s ‘A glimpse into the mythology of the Maluti Bushmen’: a contextual introduction and republished text.” Southern African Humanities 25 (2013): 137–166. [Google Scholar]

- W. Bleek. “Remarks.” The Cape Monthly Magazine 9 (1874): 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- J.M. Orpen. “1874 A glimpse into the mythology of the Maluti Bushmen.” Cape Monthly Magazine 9: 1–10.

- S. Challis, J. Hollman, and M. McGranaghan. “‘Rain snakes’ from the Senqu River: new light on Qing’s commentary on San rock art from Sehonghong, Lesotho.” Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2013.797135. [Google Scholar]

- I. Schapera. The Khoisan Peoples of Southern Africa. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- A. Barnard. Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa: A Comparative Ethnography of the Khoisan Peoples. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- A. Hoff. “The water snake of the Khoekhoen and /Xam.” South African Archaeological Bulletin 52, 165 (1997): 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Sullivan. “Difference, identity and access to official discourses: Hai//om, ‘Bushmen’, and a recent Namibian ethnography.” Anthropos 96 (2001): 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- P. Wintjes. “A pictorial genealogy: the rainmaking group from Sehonghong Shelter.” Southern African Humanities 23 (2011): 17–54. [Google Scholar]

- P. Mitchell, and S. Challis. “A ‘first’ glimpse into the Maloti Mountains: the diary of James Murray Grant’s expedition of 1873-74.” Southern African Humanities 20 (2008): 399–461. [Google Scholar]

- J.D. Lewis-Williams. Believing and Seeing: Symbolic Meanings in Southern San Rock Paintings. London: Academic Press, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- A. Solomon. “The myth of ritual origins? Ethnography, mythology and interpretation of San rock art.” South African Archaeological Bulletin 52 (1997): 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Low. “KhoeSan shamanistic relationships with snakes and rain.” Journal of Namibian Studies 12 (2012): 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- C. Power. “The Woman With the Zebra’s Penis: Evidence for the Mutability of Gender Among African Hunter-Gatherers.” Masters Thesis, University College London, London, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- R.G. Bednarik, J.D. Lewis-Williams, and T.A. Dowson. “On neuropsychology and shamanism in rock art.” Current Anthropology 31, 1 (1990): 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Pager. “The ritual hunt: parallels between ethnological and archaeological data.” South African Archaeological Bulletin 38 (1982): 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.D. Lewis-Williams, and D.G. Pearce. San Spirituality: Roots, Expression, and Social Consequences. Oxford: Alamira Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- A. Jones. “Dialectics and difference: against Harvey’s dialectical post-Marxism.” Progress in Human Geography 23, 4 (1999): 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T.N. Huffman. “The trance hypothesis and the rock art of Zimbabwe.” South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 4 (1983): 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Mallen. “Linking Sex, Species and a Supernatural Snake at Lab X Rock Art Site.” South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 9 (2005): 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- J. Kinahan. “Towards an archaeology of mimesis and rain-making in Namibian rock-art.” In The Archaeology and Anthropology of Landscape: Shaping your Landscape. Edited by R. Layton and P.J. Ucko. London: Routledge, 1999, pp. 336–356. [Google Scholar]

- T. Lenssen-Erz. “Jumping about: springbok in the Brandberg rock paintings and in the Bleek and Lloyd collection—an attempt at a correlation.” In Contested Images: Diversity in Southern African Rock Art Research. Edited by T.A. Dowson and D. Lewis-Williams. Johannesburg: Witswatersrand University Press, 1994, pp. 275–291. [Google Scholar]

- B. Fuller. “Institutional Appropriation and Social Change Among Agropastoralists in Central Namibia 1916-1988.” PhD Dissertation, Boston Graduate School, Boston, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- D. Morris. “Driekopseiland and ‘the rain’s magic power’: history and landscape in a new interpretation of a Northern Cape rock engraving site.” Masters Thesis, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- T. Lenssen-Erz. “Coherence—a constituent of ‘scenes’ in rock art.” Rock Art Research 9, 2 (1992): 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- S. Schmidt. “Mythical snakes in Namibia.” In Proceedings of the Khoisan Identities and Cultural Heritage Conference. Edited by Bank A. Cape Town: Infosource, 1998, pp. 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- S. Sullivan. “Nature on the Move III: (Re)countenancing an animate nature.” New Proposals: Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Enquiry 6, 1-2 (2013): 50–71. [Google Scholar]

- J. Deacon. “2002 Southern African Rock-Art Sites, in collaboration with members of the Southern African Rock Art Project (SARAP).” Available online URL http://www.icomos.org/fr/notre-action/diffusion-des-connaissances/publications/etudes-thematiques-pour-le-patrimoine-mondial/116-english-categories/resources/publications/227-southern-african-rock-art-sites accessed 14 September 2013.

- B. Lau. “A critique of the historical sources and historiography relating to the ‘Damaras’ in pre-colonial Namibia.” BA(Hons) Dissertation, University of Cape Tow, Cape Town, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- S. Sullivan. “Gender, ethnographic myths and community-based conservation in a former Namibian ‘homeland’.” In Rethinking Pastoralism in Africa: Gender, Culture and the Myth of the Patriarchal Pastoralist. Edited by D. Hodgson. Oxford: James Currey, 2000, pp. 142–164. [Google Scholar]

- M. Biesele. Women Like Meat: The Folklore and Foraging Ideology of the Kalahari Ju’/hoan. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Wits University Press and Indiana University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- P. Vinnicombe. “Myth, motive, and selection in Southern African Rock Art.” Africa 42, 3 (1972): 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Vinnicombe. People of the Eland: Rock Paintings of the Drakensberg Bushmen as a Reflection of Their Thought and Life. Witswatersrand: Wits University Press, 2009(1976). [Google Scholar]

- É. Carthailac, and H. Breuil. La Caverne d’Altamira à Santillane près Santander (Espagne). Monaco, 1906. [Google Scholar]

- G. Curtis. The Cave Painters: Probing the Mysteries of the First Artists. New York: Anchor Books, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- P.S.C. Taçon. ““If you miss all this story, well bad luck”: Art and the validity of ethnographic interpretation in western Arnhem land, Australia.” In Rock Art and Ethnography. Edited by M.J. Morwood and D.R. Hobbs. Melbourne: Australian Rock Art Research Association Occasional Publication 5, 1992, pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- J. Flood. Rock Art of the Dreamtime: Images of Ancient Australia. Sydney: Angus&Robertson, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- R. Echo-Hawk. The Magic Children: Racial Identity at the End of Race. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press Inc., 2010. [Google Scholar]

- L.H. Robbins, A.C. Campbell, G.A. Brook, and M.L. Murphy. “World’s oldest ritual site? The ‘Python Cave’ at Tsodilo Hills World Heritage Site, Botswana.” NYAME AKUMA, the Bulletin of the Society of Africanist Archaeologists 67 (2007): 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- S. Sullivan. “People, Plants and Practice in Drylands: Sociopolitical and Ecological Dynamics of Resource Use by Damara Farmers in Arid North-West Namibia.” PhD Thesis, University College London, London, 1998. online http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1317514/. [Google Scholar]

- S. Sullivan. “2005 Detail and dogma, data and discourse: food-gathering by Damara herders and conservation in arid north-west Namibia.” In Rural Resources and Local Livelihoods in Sub-Saharan Africa. Edited by K. Homewood. Oxford: James Currey and University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 63–99.

- A.B. Smith. Pastoralism in Africa: origins and development ecology. London: Hurst, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- K. Homewood. Ecology of African Pastoralist Societies. Oxford: James Currey, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- J. Kinahan. “From the beginning: the archaeological evidence.” In A History of Namibia: From the Beginning to 1990. Edited by M. Wallace. London: Hurst & Co, 2011, pp. 15–43. [Google Scholar]

- R.B. Lee. The !Kung San: Men, Women, and Work in a Foraging Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- R. Elphick. Khoikhoi and the Founding of White South Africa. Johannesburg: Raven Press, 1985(1977). [Google Scholar]

- E. Wilmsen. Land Filled With Flies: A Political Economy of the Kalahari. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- R.J. Gordon, and S. Sholto Douglas. The Bushman Myth: The Making of a Namibian Underclass. Boulder: Westview Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- W.D. Hammond-Tooke. “Divinatory animals: further evidence of San/Nguni borrowing? ” South African Archaeological Bulletin 54 (1999): 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Jolly. “The San rock painting from “The Upper Cave at Mangolong”, Lesotho.” South African Archaeological Bulletin 61, 83 (2006): 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- C. Low. Khoisan Medicine in History and Practice. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, 2008a. [Google Scholar]

- C. Low. “Khoisan wind: hunting and healing.” In Wind, Life, Health: Anthropological and Historical Perspectives. Edited by E. Hsu and C. Low. Oxford: Oxford, Blackwell Publishing, 2008b, pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- S. Sullivan. “Folk and formal, local and national: Damara cultural knowledge and community-based conservation in southern Kunene, Namibia.” Cimbebasia 15 (1999): 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- S. Schmidt. Catalogue of the Khoisan Folktales of Southern Africa. Hamburg: Buske, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- M. Guenther. Tricksters and Trancers: Bushman Religion and Society. Indiana University Press: Bloomington, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- P.J. Mitchell, and I. Plug. “Ritual mutilation in southern Africa: gender and ethnic identities and the possibilities of archaeological recognition.” In Our Gendered Past: Archaeological Studies of Gender in Southern Africa. Edited by L. Wadley. Johannesburg: Witswatersrand University Press, 1997, pp. 135–166. [Google Scholar]

- E. Swyngedouw. “Modernity and hybridity: nature, regeneracionismo, and the production of the Spanish waterscape, 1890-1930.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 89, 3 (1999): 443–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Ingold. The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- B. Latour. Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy. Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- R. Mabey. Nature Cure. London: Vintage, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- G. Deleuze, and F. Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. London: The Athlone Press, 1988(1980). [Google Scholar]

- B. Latour. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- M. Foucault. Security, Territory, Population. Lectures at the Collège de France 1977/78. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009(1977/78). [Google Scholar]

- J.E. Alexander. An Expedition of Discovery into the Interior of Africa, Vol. 1. Cape Town: Struik, 1967(1838). [Google Scholar]

- C.J. Andersson. Lake Ngami. London: Hurst & Blackett, 1856. [Google Scholar]

- G.R. Von Wielligh. Boesman Stories. Deel 1: Mitologie en Legendes. Cape Town: Nasionale Pers, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- E. Eiseb, W. Giess, and W. Haacke. “A preliminary list of Khoekhoe (Nama/Damara) plant names.” In Dinteria. 1991, Volume 21, pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- A. Botelle, and R. Scott. Born in Etosha, parts 1 and 2. Windhoek: Mamokobo Video and Research, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- C. Low. “Different histories of buchu: Euro-American appropriation of San and Khoekhoe knowledge of buchu plants.” Environment and History 13 (2007): 333–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Sullivan. “Protest, conflict and litigation: dissent or libel in resistance to a conservancy in north-west Namibia.” In Ethnographies of Conservation: Environmentalism and the Distribution of Privilege. Edited by E. Berglund and D. Anderson. Oxford: Berghahn Press, 2003, pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- D.F. Bleek. “Beliefs and customs of the /Xam Bushmen. Part V: The rain.” Bantu Studies 9 (1933): 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Challis. “‘The men with rhebok’s heads; they tame elands and snakes’: incorporating the rhebok antelope in the understanding of Southern African rock art.” South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 9 (2005): 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- P. Mitchell, and S. Hudson. “Psychoactive plants and southern African hunter-gatherers: a review of the evidence.” Southern African Humanities 16 (2004): 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- J. Marais. A Complete Guide to the Snakes of Southern Africa. Johannesburg: Struik, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- I. Schatz. Unter Buschleuten auf der Farm Otjiguinas. Tsumeb: Ilsa Schatz, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- K. //Khumub, A. Botelle, R. Scott, and C. Bosman. The Awakening. Windhoek: Mamokobo Video and Research, 2007a. [Google Scholar]

- L. Marshall. “!Kung Bushman religious beliefs.” Africa 32 (1962): 221–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Silbabauer. Hunter and Habitat in the Central Kalahari Desert. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- C. Valientes-Noailles. The Kua: Life and Soul of Central Kalahari Bushmen. Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- A. Barnard. “Structure and fluidity in Khoisan religious ideas.” Journal of Religion in Africa 18 (1988): 216–236. [Google Scholar]

- J.D. Lewis-Williams, and T. Dowson. Images of Power: Understanding San Rock Art. Cape town: Struik Publishers, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- C. Low. “KhoeSan ethnography, ‘new animism’ and the interpretation of Southern African Rock Art.” South African Archaeological Bulletin. In press.

- E. Viveiros de Castro. “Exchanging perspectives: the transformation of objects into subjects in Amerindian ontologies.” Common Knowledge 10, 3 (2004): 463–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Katz. Boiling Energy: community healing among the Kalahari Kung. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- S. Sullivan. “On dance and difference: bodies, movement and experience in Khoesān trance-dancing.” In Talking About People: Readings in Contemporary Cultural Anthropology, 4th Edition. Edited by W.A. Haviland, R. Gordon and L. Vivanco. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006, pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- B. Keeney. 2005 Bushman Shaman: Awakening the Spirit Through Ecstatic Dance. Rochester, Vermont: Destiny Books, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- K. //Khumub, A. Botelle, R. Scott, and C. Bosman. Journey of a Rain Shaman. Windhoek: Mamokobo Video and Research, 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- J.D. Lewis-Williams. “Southern African shamanistic rock art in its social and cognitive contexts.” In The Archaeology of Shamanism. Edited by N.S. Price. London: Routledge, 2001, pp. 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- W.H.G. Haacke, and E. Eiseb. “A Khoekhoegowab Dictionary With an English-Khoekhoegowab Index.” Windhoek: Gamsberg Macmillan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- K. Sugawara. “Cognitive space concerning habitual thought and practice toward animals among the central San (Gui and Gana): deictic/indirect cognition and prospective/retrospective intention.” African Study Monographs 27 (2001): 61–98. [Google Scholar]

- H. Brody. The other side of Eden: hunters, farmers and the shaping of the world. New York: North Point Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- T. T. Hahn. Tsuni-llgoam: The Supreme Being Of The Khoi-Khoi. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing LLC, 1881. [Google Scholar]

- S. Sullivan. “‘Ecosystem service commodities’—a new imperial ecology? Implications for animist immanent ecologies, with Deleuze and Guattari.” New Formations: A Journal of Culture/Theory/Politics Special issue, entitled ‘Imperial Ecologies’. 69 (2010): 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “BBC 2007 Workers discover ancient ‘snake’.” BBC News UK. 4 July 2007. Available online URL http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/hereford/worcs/6268900.stm accessed 22 January 2013.

- M. Walters. Yet we Survive the Kalinago People of Dominica: Our Lives in Words and Pictures. London: Papillote Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- R. Morris, and D. Morris. Men and Snakes. Maidenhead: McGraw Hill, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- B. Morris. Animals and Ancestors: An Ethnography. Oxford: Berg, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Research Council of Norway. “World’s oldest ritual discovered—worshipped the python 70,000 years ago.” ScienceDaily. 30 November 2006. Available online URL http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/11/061130081347.htm accessed 22 January 2013.

- B. Mundkur. The Cult of the Serpent: An Interdisciplinary Survey of Its Manifestations and Origins. New York: State University of New York, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- H.S. Thông. The Golden Serpent: How Humans Learned to Speak and Invent Culture. Thông, H.S.: self-published; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- P. Broadhurst, and H. Miller. The Sun and the Serpent: A Journey Through the British Landscape, its Mythology, Ancient Sites and Mysteries. Launceston, Cornwall: Mythos, 2003(1989). [Google Scholar]

- R. Willis. “The meaning of the snake.” In Signifying Animals: Human Meaning in the Natural World. Edited by R. Willis. London: Routledge, 1990, pp. 233–239. [Google Scholar]

- C. Levi-Strauss. Totemism. Pontypool: The Merlin Press, 1991(1962). [Google Scholar]

- C. Knight. Blood Relations:Menstruation and the Origins of Culture. London: Yale University Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- J. Narby. The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge. London: Phoenix, 1999. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Sullivan, S.; Low, C. Shades of the Rainbow Serpent? A KhoeSan Animal between Myth and Landscape in Southern Africa—Ethnographic Contextualisations of Rock Art Representations. Arts 2014, 3, 215-244. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts3020215

Sullivan S, Low C. Shades of the Rainbow Serpent? A KhoeSan Animal between Myth and Landscape in Southern Africa—Ethnographic Contextualisations of Rock Art Representations. Arts. 2014; 3(2):215-244. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts3020215

Chicago/Turabian StyleSullivan, Sian, and Chris Low. 2014. "Shades of the Rainbow Serpent? A KhoeSan Animal between Myth and Landscape in Southern Africa—Ethnographic Contextualisations of Rock Art Representations" Arts 3, no. 2: 215-244. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts3020215

APA StyleSullivan, S., & Low, C. (2014). Shades of the Rainbow Serpent? A KhoeSan Animal between Myth and Landscape in Southern Africa—Ethnographic Contextualisations of Rock Art Representations. Arts, 3(2), 215-244. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts3020215