2. Marcel Duchamp: The Large Glass

Marcel Duchamp first made reference to the machine célibataire apparatus in 1913, when he wrote notes in preparation for

La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even), also known as

Le Grand Verre (The Large Glass) (1915–1923), now permanently displayed in the Arensberg Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Though well-known,

The Large Glass, made of two large panes of glass, seems inexhaustible in terms of its larger meaning and thus infinitely mysterious and useful (

Henderson 2005). Conceiving it as an eroticized corpulent machine, Duchamp in his notes used such terms to describe its parts: ‘sex cylinder’, ‘desire gear’, ‘reservoir of love gasoline’, and ‘general area of desire magneto’. Within the notes, Duchamp also identifies the specific bachelor machine’s component parts as a water paddle, scissors, a chocolate grinder, a sledge, and nine malic molds. Technically, he employed a toy cannon to shoot paint-dipped matches at the glass ground of this work to determine the positions of these nine malic molds that were intended to represent nine job types, into which males are molded as men (all middle class or lower): a priest, a delivery man, a gendarme (military police), a cuirassier (cavalry soldier), a police officer, an undertaker, a go-fer sycophant, a busboy, and a railroad stationmaster.

Any prurience aroused by the title is not gratified by looking at either the bride or the bachelors, who are linked together, like a daisy chain of mechanical implements or schematic diagrams. They sit well below the looming bride (who scarcely looks naked and hardly looks female), hovering wasp-like in the upper panel, sealed off by a segmenting metal strip. Duchamp imagined in the lower Bachelor Apparatus section these nine bachelor bootlickers cock-blocked: trapped in a chain of repetitive emotional states that flutter between hope, desire, and fear.

I find this emotional chain (or cycle) prescient, as this fearful-hopeful-yearning state has now become emblematic of Art

writ large, due to the rhizomatic (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987) internet condition of art as spectacle, endlessly flowing in attention-seeking circularity (

Debord 1976). Like the net, Duchamp’s

Large Glass as a mental masturbation machine contains the two great mythic spaces so often explored by western imagination: space that is rigid and forbidden—that requires a circular quest and return (for example, the trail of the Argonauts)—and the space of polymorphic confused borders, of strange affiliations, of magical spells, and of symbolic replacements (the labyrinth space of the Minotaur).

While waiting for the bride’s gratifying attention, the sexually frustrated bachelors below are enacting an enigmatic fantasy drama of competing passion (or aggression), suggested by the phrase “stripped bare” in the full title of the piece. All the bachelors hope and strive to bed the bride, but fear of vague consequences holds them back in a state of frustration, which introduces the important psychosexual function of the chocolate grinder, that nearly dominates the Bachelor Apparatus zone. This important form was transferred to

The Large Glass from Duchamp’s delicious painting

Chocolate Grinder (No. 1) (1913). The grinding machine in the Bachelor Apparatus area signifies how the bachelors, frustrated with their inability to mate with the bride machine, may achieve some sweet satisfaction by repeatedly sexually stimulating their own genital apparatus, thus demonstrating a sort of faux dual-sexuality that can be described as the “simultaneous or successive possession of both sexes by a single individual” (

Brisson 2002, p. 1).

This feverish theme of onanistic dual-sexual circularity in The Large Glass presents us with a model of gender grandeur: a theoretical imaginative bisexual machine that functions independently of “the other”, thereby pulling faux dual-sexual passion into a developmental logic of its own, leading to a transcendental infinite. It is here, in the faux dual-sexual self-pleasuring chocolate grinder, where I detect some spiritual implications of the nine male types, who Duchamp has virtualized and sprayed into their discrete zone of remote presence. Their endless faux dual-sexual self-pleasuring (that smoothly shrivels into asexuality or explodes into pansexuality) implies two polymorphic viewpoints: that of asexual and pansexual bachelor machines.

Crucial to the imaginative fantasy powers of a pansexual bachelor machine is the implementation of a theory of the variegated virtual (

Shanken 1997). This theory assumes the existence of preposterous and imaginatively configured subjects able to ford human anthropocentric sexual frontiers. Duchamp’s use of post-humanist chance in the making of his bachelor machine implies that the artist relinquishes, to a greater or lesser degree, the power to close down the final interpretation of a work, i.e., keeping it open to interpretation (

Eco 1989), which facilitates all sort of imaginative and fluid mental processes in the viewer. Thus, for me, a spiritual implication of

The Large Glass is the denial of sexual determinism in favor of the potency of apparent pansexual fluidity in circularity

ad infinitum. This means an implicit refutation of the assumption that the ‘neutral’ body is always white and straight and masculine. Thus, the circular implication of faux dual-sexuality has directed my focus in theorizing and coding post-bachelor hermaphrodite, artificial life, and viral art projects as early as 1992 (

Gruson 1993), as well as computer-robotic painting pansexual bachelor machine images (

Lewis 2003), with Duchamp’s male bachelor machine as starting point.

3. Marcel Duchamp: The Bride

The cold impersonality of technology and the heat of dual (or dueling) sex is a curious alliance. Prior to

The Large Glass, Duchamp produced a few cherished images depicting mechanized sexuality. Among them the drawing

Vierge, No. 1 (Virgin No. 1) (1912), and the paintings

Le Passage de la Vierge à la Mariée (The Passage from the Virgin to the Bride) (1912) and

La Mariée (The Bride) (1912,

Figure 2). Intriguingly, he painted both of these the year he proclaimed the end of painting, the same year he visited an aeronautical exhibition with Fernand Léger as they were admiring an elegant airplane propeller. Particularly in the wonderful

Bride, who appears as the bride in

The Large Glass, the elaborateness of her repeatedly pumping machine gear suggests an excess of sexual bliss attainable through circular, auto-sexual, and faux bisexual autonomy. Such body politics contains an admixture of romantic ideals and auto-mechanical sensations, where the psyche may become lost in a throbbing spiral of labyrinthine extensions, duplications, and repetitions. Although arrived at by chance (twenty-five notes randomly picked from a hat), Duchamp’s first musical endeavor, the 1913

Musical Erratum: La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (for piano) (Duchamp 2008) makes the same circular point by stubbornly repeating only two up-and-down notes for the first 43 s. Listening to these masturbatory repetitions in

Musical Erratum while contemplating the pumping mechanics of

The Bride introduces a trance element into Duchamp’s aesthetic and casts his bachelor machine into the dizzying activities of the impersonal but ingenious dandy (

Huysmans 1973). However, I also think of this pumping trance-state as Duchamp’s definitive desire when he is in an uninhibited bachelor machine mode: a detached, depersonalized, and mystical state of being (

Stace 1960).

It is curiously true that this depersonalized dizzying circularity is comparable to how algorithms now run automatically behind the technological scene (

Johnston 2008). Thrusting away in cellular automaton artificial life is something so astoundingly pregnant with auto-bachelor machine circularity that it excites and stimulates creativity, as I discovered with my cellular automaton-based

Computer Virus Project 2.0 (2002) (

Nechvatal 2011, p. 252), a resultant series of pansexual paintings created in the early-2000s (

Lewis 2003).

In art, the patriarchal construction of woman as other and the female body as object, though contested (

Betterton 1996), is deeply rooted in the supposed duality (opposites) of the (two) sexes. Most feminist theory questions this patriarchal construction of sex and gender, suggesting that sex is expressed through a continuum, rather than as an opposing couplet based on heterosexist male/female polarities (

Butler 2004). Accordingly, within dual-sexual hermaphroditic auto-bachelor machines, containments designed for womanhood/manhood are subverted by the mutable image of pansexuality. Gender here is theorized as an act of becoming. Consequently, art fails to sustain sex oppression in culture by ceasing to draw the boundaries of the Other.

Going a step further, hermaphroditic-sexual bachelor machines are a provocation not only to male/female constructions of heterosexuality, but also to homosexual constructions of identity. I discovered this while working on my hermaphroditic painting series for the New York City exhibitions

ec-satyricOn (2000),

vOluptuary: an algorithic hermaphornology (2002), and

Real Time (2004). For all three shows I melded images of the sex organs of both sexes into a chimera field of virtuality that went under viral attacks scripted in C++ as artificial life. The results yielded many quixotic transformations, where all sort of pan-sex orders arose (

Nechvatal 2011, p. 246). But as digital bachelor machines are immaterial pure information spaces, it is neither surprising nor coincidental that the immense perspective of algorithmic auto-bisexual bachelor machines requires a questioning of the legitimacy of common sexual organ arrangements and familiar forgone conclusions concerning theoretical issues around sexual politics, gender studies, and the farther-reaching heterogeneous philosophical critique of the cultural mechanisms of representation (

Foucault 1970) that have preceded it.

Of course, Duchamp set the stage by countering bourgeois ideals of masculinity. Duchamp considered himself to be counter-type, un artiste désœuvré (an idle artist), after he temporarily abandoned the production of traditional art objects. While the 19th century dandy was a masculine figure, his masculinity had a lot in common with artificial and constructed femininity. Indeed, in late-19th century French culture, the dandy was often considered decadent and effeminate in a vague way that verged on the homosexual. Regardless, the travestying heterosexual Duchamp staged himself in bisexual dandy drag as Rrose Sélavy for a series of femme fatale photos done in 1921 by Man Ray. When read out loud pronouncing both “r”s, Rrose Sélavy can sound like Eros, c’est la vie (Eros is life). In an artwork called Belle Haleine. Eau de voilette (Beautiful Breath: Veil Water) (1921), Duchamp first incorporated his Sélavy drag portrait on the label of a perfume bottle, effecting a bisexual metamorphosis into a cross-dressed alter ego seemingly lost in the scent of gender-masked maneuvers. But what are some earlier dandy-era precedents of self-transcending pansexual bachelor machines avant la lettre?

4. Raymond Roussel and Auguste Rodin

Along with Guillaume Appollinaire, Francis Picabia, and Gabrièle Buffet-Picabia, Duchamp attended a 1912 performance of

Impressions d’Afrique (Impressions of Africa), a wacky play by Raymond Roussel based on his 1910 book of the same name (

Roussel 2001), which was written according to formal constraints based on homonymic puns. This play was a revelatory intellectual experience for Duchamp, to the extent that he would credit it with helping inspire

The Large Glass (

Henderson 2005). Clearly, its punning delirium pushed Duchamp’s bachelor machine idea towards celebrating exhaustive circularity and its effects of intransigent obliqueness and mechanical dizziness. For this reason, Duchamp’s faux dual-sexual self-pleasuring grinding machine is always a potentially transgressive proposition, as regards to bourgeois ideals concerning the difference between the sexes.

Salient to this circular connection is Michel Foucault’s analysis of Roussel’s invention of dreamy language machines, which produced texts through repetitions and combination-permutations. Foucault explains how a machine-like logic provides Roussel’s writing with a seemingly endless variety of textual combinations, flowing in grinding circular form. Roussel’s technique of endless grinding lent itself to the creation of unforeseen, automatic, and spontaneous invention, which gives the reader a feeling of being pulled into an onanistic eternity. By grinding and grinding, and through his use of labyrinthine extensions, doublings, and duplications, Roussel transmits to the reader the sense of an altered, circular, and exalted state of mind (

Foucault 1986). Foucault’s revealing analysis of Roussel’s final deliriousness book,

Comment j’ai écrit certains de mes livres (How I Wrote Certain of My Books) (

Roussel 2005), contains and repeats all the mental-machines Roussel had formerly put into motion, and by doing so, evidencing the master-grinding-machine that produced his text-machines. Here I grasped the stylistic mood of grinding gamesmanship associated with Duchamp’s bachelor machine—an extravagant, intricately hermetic, elaborate, and mechanical-morphism that is conceptually consistent with Duchamp’s exuberant and preposterous faux dual-sexual desires. Like Duchamp’s dazzling bachelor machine, Roussel’s themes and procedures involved isolated and frustrated stereotypes that were reflected in his writing method, with its inextricable play of double images, repetitions, and impediments, all of which created a feeling of an altered, exalted, and orgasmic state of mind.

But I discovered another self-stimulating onanistic bachelor machine precedent in Auguste Rodin’s well known sculpture

Le Monument à Balzac (The Monument to Balzac) (1898,

Figure 3). Duchamp’s bachelor machine, like all bodies, is inscribed with the values and beliefs of the culture from which it emerged. As evidenced in Rodin’s

Balzac, second nude study F (1886,

Figure 4), the sculptor secretly formed an autoerotic bachelor machine model of artistic self-stimulation. The finished work that stands on boulevard Raspail (also at the Rodin Museum, at MoMA, and elsewhere) replicates the pose of the

Balzac, second nude study F to a tee, with the cloak covering the busy bulge. The backward lean in this study is the definitive posture of the Balzac monument.

Rodin’s objective for this bachelor machine was to depict a ballsy Balzac at the moment of conceiving the idea for a work of art through onanistic imaginative gazing. That Rodin chose to furtively depict Balzac as an onanist is far from ludicrous, as Balzac used masturbation (without climax) to intensify his writing sessions, drinking many cups of coffee, again masturbating just short of orgasm, halting, writing, and repeating, like a well-oiled machine.

In his 1954 book,

The Bachelor Machines, Michel Carrouges points out that all bachelor machines share the signification of such autoerotic circularity (

Carrouges 1954). All bachelor machines are mental sex machines, the imaginary workings of which suffices to produce real movements of mind-body. Although curator Harald Szeemann revisited and expanded Carrouges’s argument in a 1975 traveling exhibition, also entitled

The Bachelor Machines (

Clair and Szeemann 1975), he left out some historical Modern figures that I would like to add here before moving on to theorize the current complex pansexual bachelor machines of the mind.

5. Fernand Léger, Francis Picabia, André Masson and Oskar Schlemmer

Gender-fluid bachelor machines are already detectable in some of Fernand Léger’s earliest artworks. What particularly interests me about Léger is how his imagery enters the oily slipstream of the bisexual cyborg, where distinctions between sex, the body, and robotics blur in the density of speeding political networks (

Terranova 2004). We see this in the best painting Léger ever made: his rich, velvety textured, pre-war composition,

La Noce (The Wedding) (1912,

Figure 5), completed the same year Duchamp painted

The Bride.

The Wedding is so jam-packed with crunchy cubist incident that it is difficult to decipher at first glance. It has a nonchalant, silky, falling feel to it. Like a fine, nuanced, and balanced wine, this painting exhibits the bachelor machine intensity without metallic heaviness. It draws the eye to the full rhythmic structure of the kaleidoscopic space where smaller, interlocking elements lure the gaze into deeply opulent repetitions of machine-like (and implicitly sexual) exploits. The painting’s male and female couple fuse into gyrating repeats in a complex and cryptic way, lending the work a vivacious and sleek visual texture that is delightfully seductive. The couple and surrounding multitude procreate into a repetitive orgy-machine, pulling the mind into an infinite mechanical pan-logic that is almost transcendental. Their post-flesh machine unanimity is set flowing in jerks and spasms across the surface of the canvas.

Léger has imposed on gender here a vibrating restlessness of Rousselian proportions. Again we fall into a labyrinthine of repeats, extensions, and stutter doublings. In

The Wedding, Léger paints the idea of gendered flesh undergoing a cascade of annihilation. Yet the composition’s flickering staccato repetitions create the impression of a rolling bacchanalia, where human forms also transcend that annihilated fleshiness and extend themselves through motorized re-embodiment into a kind of pan-transubstantiation. With

The Wedding, Léger seems to suggest that the glory of artificial life is to be found in the technological apparatus of mixed bodies, tumbling into a field of circuits (

Weibel 1990). Likewise, in his painting

Le Cirque Medrano (The Medrano Circus) (1918), exuberant performing figures are put through Léger’s mechanical meat grinder and expelled into the hyperreal dominion of entertainment simulacrum.

Léger, though not himself a Dadaist, would, like the Dadaists, make much of the machine; unlike them, however, he would make little of sex farce. He did not mock sex as machinic the way Francis Picabia did during his machinist period, when he too blended a machine aesthetic with representations of the human-machine body, as in Parade amoureuse (Love Parade) (1917). Still, both artists paint the interface between sex and the machine.

Undoubtedly, when in his Dada tecnomorphic period, Picabia illuminated such spatialized sexual paradigms by mixing implied human bodies with mechanical schematics. Again, like in Léger’s The Wedding and Duchamp’s mental-mechanical sex machine, the sexual body is endowed with ecstatic transcendent capabilities through the endless repetitions of oiled machinery. So it is not surprising that Picabia, like Léger, was also a member of the Section d’Or (Golden Section) group that was associated with Marcel Duchamp and his brothers.

Like Duchamp and Picabia, Léger also distributed and blurred disparate body parts and mechanical elements in his paintings, in what looks to be a turbulent and haphazard fashion, challenging the ‘humanist’ conceptions of ‘man’, similar to Duchamp’s man-mechanical approach. This is most evident in Léger’s paintings of the mustachioed Le mécanicien (The Mechanic) (1918) and the L’Homme à la pipe (Man with Pipe) (1920), with their tin man-like volumes. In these two proto-robotic tour de forces, Léger clearly sets up Picabia-like tensions between the human narrative and the mechanical spectacle that points in the direction of neuro-computing wetware, bio-robotics, and all of the AI-charged automatization humming away in the space between the mechanic, the digital, and the organic. This humming is why these Modernist bachelor machines sing to us as a mythic oracle.

But the other great construct of tipsy bachelor machine automatization, and I think Léger’s paramount work, features Kiki de Montparnasse. Léger co-directed her, with American film director Dudley Murphy, in their nourish flicker-film chef-d’oeuvre,

Ballet mécanique (Mechanical Ballet) (1924,

Figure 6), where Kiki is cast fluctuating between figuration and abstraction.

Mechanical Ballet is a Dada masterpiece of early-experimental film, stringing together a reeling mechanic-mental river of sensations both flashy and frustratingly repetitive. Like Duchamp’s bachelor machine,

The Large Glass, which was declared definitively unfinished the year before the film was made,

Mechanical Ballet is a bid at eliminating our sense of linier time. Through the construction of its repeats, the film gives me the fantastic feeling of prolongation into an erotic eternity.

Mechanical Ballet, much of it shot by Man Ray, smartly transmits an altered, exalted, and orgasmic state of mind that is perfectly complimented by George Antheil’s noise music soundtrack: his 30 min long Ballet mécanique (Mechanical Ballet) (1924). This pummeling composition recalls the beginning of Duchamp’s Musical Erratum for piano, and was originally conceived of as the musical accompaniment to the film, but due to length differences, eventually the filmmakers and composer chose to let their creations evolve separately (although the film credits always included Antheil). Nevertheless, Antheil’s Mechanical Ballet premiered as concert music in Paris in 1926 and is majestic in and of itself. But when included in the film, as it now is, everything is permutated with a pulsating and flickering energy of go/stop/go/stop/go/stop/go—depicting a hyperactive current of techno machine forces on the body. The film, with an insistent flicker, is flush with discontinuous, fragmented, and kaleidoscopic sensations that remind me of The Wedding. The screen pulsates with the hot energies of modern life and its dull repetitions.

Mechanical Ballet is a stunning spasmodic display of stutter-and-flicker-and-looped concentration, where relationships between the protoplasmic body and mechanical repeats invite meditation on the self-prosthesis of pansexual bachelor machines. In this flickering metamorphic ballet, the human body is at the center of traditional narrative subjectivity and again undone by a visual noise it cannot contain.

Made the same year as

Mechanical Ballet, and relevant to auto-sexual bachelor machines, is the speeding, automatic, ritualistic, and revelatory mode of iconographic mark-making André Masson devised for

Automatic Drawing (1924,

Figure 7). In this jittery automatic drawing, a conflict or antagonism is set up between the ‘feminine’ litheness of curves and the ‘male’ hard angles. Up against the supple curves of a centered naked woman, aggressive lines cut through her like a knife. Slow looking reveals that the image calls to mind not only

Mechanical Ballet, but Marcel Duchamp’s

Nu descendant un escalier n° 2 (Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2) (1912). Beyond that, there is at work an automatic artistic method, which plays in the area of chaotic control/non-control, aiming towards constructing a capricious alliance that associates discourses of mechanic grinding with organic sexuality, an association that opens up both notions to mental connections that enlarge them. Here the coming cyborg woman of Fritz Lang’s

Metropolis (1927,

Figure 8) and Donna Haraway (

Haraway 1991) are already undone by overwhelming complex disturbances they cannot contain. That immersion into visual noisy disturbance (

Nechvatal 2011) is essential to theorizing pansexual bachelor machines.

Masson’s likewise intense

Dessin automatique (Automatic Drawing) (1924–1925,

Figure 9) strikes hard as an example of the divinatory practice of finding subconscious desires within vague cues. It is a neurotic network of bachelor machine lines that seem fluid but hectic, and, at times, staccato-like. In what seems to appear gradually is a standing, plugged-in burial casket, surrounded by phantasmagorical figure motifs that may include object parts merged with anatomical fragments typical of bachelor machines. The sum total gives off a feeling of occultist ferment and whimsy that alludes to potential auto-sexual bachelor machines.

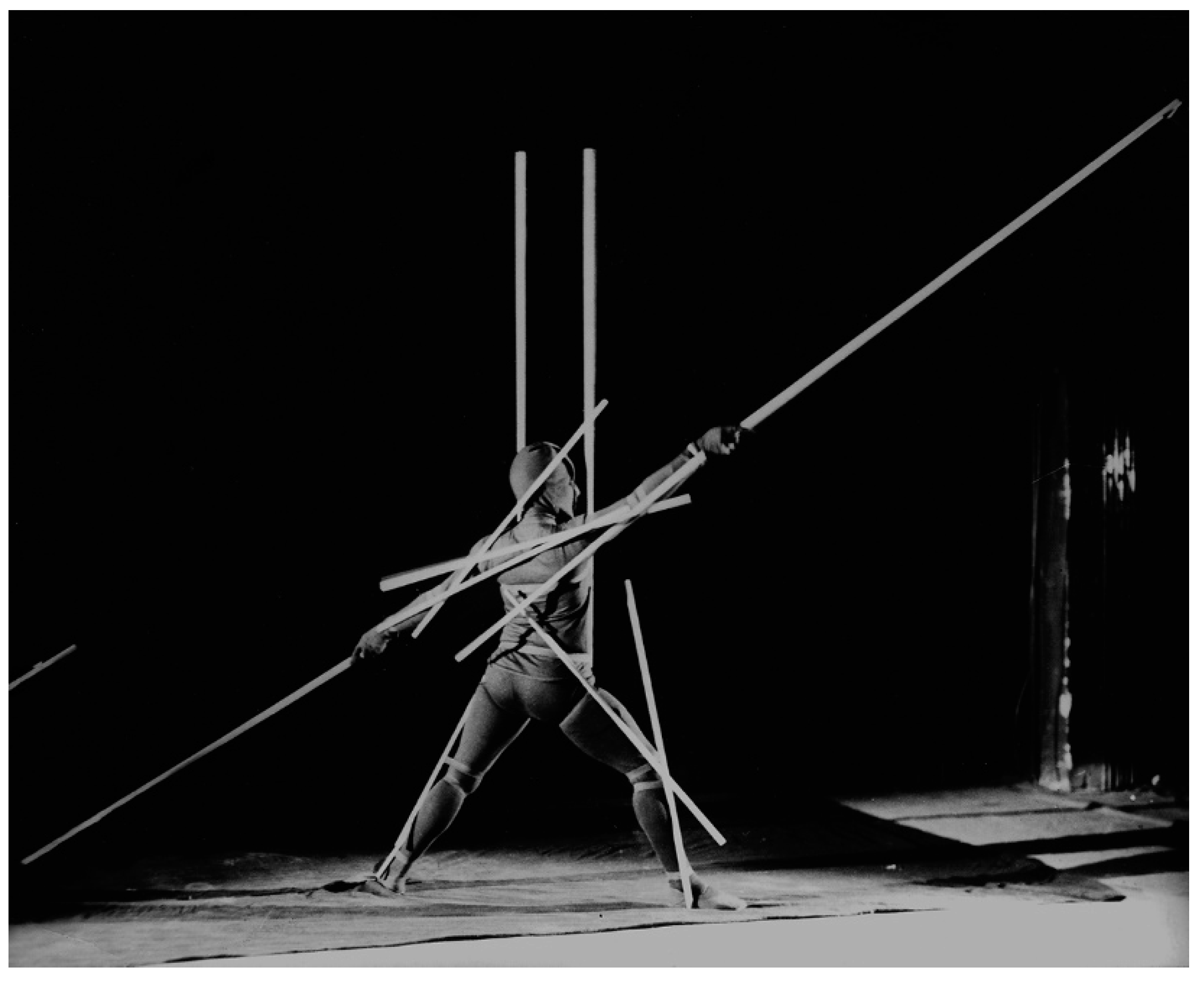

Moreover, Oskar Schlemmer’s paintings, drawings, choreography, and costume/set design flamboyantly depict the mechanic post-flesh. The coming asexual bachelor machine is most obvious when Schlemmer inserts his dancers into svelte geometric-based outfits and puts them to work, repeating spectacular sequenced motions machine-like in their repetitions (

Figure 10). Again, we have entered the sexually ambivalent android realm.

Schlemmer theorized a serene, classical, and monumental approach to the human form based on the tensions between anthropological narratives and mechanical simulacrums, a tension typical of our period’s electronic contours. His personal-impersonal amalgamate may have even predicted the spectacle of moral aridity we have come to expect within certain technological elites today. Schlemmer’s flair for an asexual robotic approach in the automated figure embodies the theorized notion of aesthetic synthesis, which is intended to symbolize social synthesis within a benevolent emerging techno-society. As such, he attempted to depict the human form as pansexually spiritual through an abstract geometric consistency of form, in service of a social totality. This idea led Schlemmer to create a proto-robotic pansexual art by virtue of a relocation of body/machine/consciousness, typical of the telematic embrace (

Ascott 2003). Following this theoretical thread, as can be seen in his

Tanz Figurinen sketchbook, Schlemmer points the mind towards churning pansexual bachelor machines: that is, cyborg sequencing merged with dematerialized flesh.

This is most obvious in Schlemmer’s

Les signes de l’Homme (Dématérialisation) (Signs of Man (Dematerialization)) (1924/1986,

Figure 11), where he raises the hyperreal issue of virtual dematerialization as interface between the human body and an abstracting, universalizing machinery. This is also obvious in his extremely delicately drawn lithograph

Figurenplan (Figure Plan) (1919), which offers up an index of his costumes within a grid scenario. As with his choreography of repetitive simple motions, it is a telltale hint at what American Minimalism will successfully create in the 1970s with

Einstein on the Beach, a four act opera by Philip Glass and Robert Wilson. The opera features task-based, quasi-robotic choreography by Lucinda Childs, where dancers’ bodies seem already spliced into a cybernetic-technomorphic circuit. This spliced sense is enhanced through the use of stiff repetition and a dismemberment of traditional narrative subjectivity. Here, the notion of the human body receives a strange, almost ecstatic, capability through trance-like, pansexual bachelor machine repetitions. In the brilliant costume

Le Ballet triadique, Figure de fil de fer, Série noire (The Triadic Ballet, Wire Figure, Black Series) (1922)—made for his masterwork

The Triadic Ballet—Schlemmer seems interested in moving robotic-like trans-crystalline bodies in space towards the formational effects of pansexual bachelor machines. He does so by constructing a space of imaginative accommodation for an intensely connected and immersed circulate (

Nechvatal 2009), suggestive of biomorphic machines as an artistic source of self-transcendence.

6. Pansexual Bachelor Machines and Oögenesis

The conceptual pansexual bachelor machine theory I am sketching out while dropping historical precedents is re-configurative and trans-figurative in intention. Based on the capacity of connected electronic media’s immeasurable intermixture, it nudges the current cultural context away from a biologically determinist reading of femininity and masculinity. The point is that within pansexual bachelor machines, all sexual signs are subject to boundless semiosis. This is to say that these signs are translatable into other signs of other sex arrangements, in order for art to articulate new sexual combinations.

Certainly, the male Modernist bachelor machine propositions mentioned above—sleek, coolly impersonal, and sexually confused—point towards needs to expand on the range of current slippery situations between fleshy embodiment and connective circumvention. By mixing abstracted bodies with mad mechanical repeating geometrics, Modernist bachelor machines suggest to me a pansexual robotic sensibility that at least temporarily refutes the sour feeling that we are living in an epoch of identity click-bait art fueled by predatory virtual capital. At least it challenges the imagination of many current cultural producers whose work has been looking dismally identity-reductive, parochial, and ethnocentric.

Privileging pangender conceptual machines suggests that we cannot be satisfied with identity-based vanity culture as art lauded by chatting memes that repeat and repeat themselves in search of bigger and bigger audiences. Clearly theorizing pansexual bachelor machines as a form of virtual art (

Popper 2007) cracks open representational boundaries between human beings and other human beings and their digital machines. These leaky boundaries—or schematas—are the reason that ideas of phantasmagorical bachelor machines (or butch machines, if you like) are interesting

as art today. The creation of mad mental sex machines has to do with an abiding conviction that cold code may be brought to a-life through the correct application of art and programming. While learning is a property almost exclusively ascribed to self-conscious living systems, AI-based a-life computer programs can now learn from past experiences and improve their operative functions to the point of surpassing human capabilities. Such post-human transcendence raises both aesthetic and ethical concerns for Art and Technology.

Much art, whether machine art or media art, has become almost indistinguishable from popular cultural commodities. Freaky a-life pansexual bachelor machines stand out as a reasonable alternative, a comparatively unpopular art approach that values farcical camp humor, transcendental metaphysics, conceptual construction, and clandestine mysticism over common human-centric assumptions for art as entertainment. The concept of a self-churning pangender machine suggests ways to think of life outside of the normal longwinded explanations and closer to Speculative Realism’s anti-anthropomorphic transcendental materialism (

Meillassoux 2008).

That is why, from beginning to end, I have appreciated avant-garde interests in an artistic-philosophical spirituality of bachelor machines (

Clair and Szeemann 1975). The idea of mad a-life pansexual bachelor machines points art away from the humanist niceties of a human-centric world and towards non-humanist modes of pangender expression that is both flamboyantly poetic and technologically terse, evoking an aesthetic that is simultaneously alchemical, cosmic, ancient, and uncannily new as artificial life.

Undoubtedly, past art theories have been unequivocal in their urge towards closure, embellished with a sort of self-significance, and, often, fallacious universalism, which I wish to avoid. If what I have said about pansexual bachelor machine theory sounds metaphysical (or a parody of metaphysics), it is so only in so far as it is early pre-memory—which takes us to oögenesis.

Oögenesis is a moment of bisexual or a-sexual development of the pre-fertilized human egg cell where both female and male potentiality exists simultaneously. It is the place and time prior to the differentiation of the ovum into a cell capable to further develop and divide as fertilized by the male seed. This moment of sexual potentiality exemplifies the transcending pansexual bachelor machine concept brilliantly, and it suggests the truth that in life somethings can be both one thing and its opposite at the same time. Two opposites can exist simultaneously and not cancel each other out.

Such peacefully sustained conflict is the agent of transformation that can engage art ideas in a play of contradictory excess (

Bataille 1985), encouraging pleasurable critical creativity (

Drucker 1996). That is why I myself have made post-conceptual generative art based on an a-life viral model as connected to the subject of the hermaphrodite (

Lewis 2003). After establishing a coded viral project in 1992 (

Gruson 1993), I became interested, around the year 2000, in oögenesis (

Nechvatal 2009, p. 66), a hermaphroditic-like pre-bifurcation moment in human development.

Pansexual bachelor machine theory investigates, through the imaginative powers of art, ways in which our sense of one-gendered self has a fluidity that defies spatial containment. As such, it opens gendered thought up to new spaces of malleable and combinatory sites, hence a perpetual multiplication of significance. Meaning in art (and in life) then advances by seeing more clearly into its own underlying assumptions of superfluity, by facing up to the radical implications of those oögenesis assumptions, and by purging itself from conventional ways of thinking by making no recourse to imagined exterior principles or a priori assumptions.

What is important in auto (or pan) sexual bachelor machines is their intentional enigma. They need to be obscure to the degree that their gender codes cannot be easily discerned (and politically used). This oögenesis obscurity (and mystery) is increasingly desirable in a world that has become progressively data-mined, identity-mapped, and sex preference quantified, in a straight-forward matter-of-fact way.

To be sure, each era has its own redundancies and compliances, so the chaotic excess of oögenesis bachelor machines works well with today’s connected cravings for unlimited information and access. Which is as it should be: the definition of artistic activity occurs, first of all, in the fields of seduction and social distribution. With pansexual bachelor machines hovering above common distinctions, conceptual transmission is already the endpoint. Fitting to today’s reality of globalization-digitization, the non-linearity of pansexual oögenesis bachelor machines propose a space of visual hyper-thought where the encountering of contradictory realities is bound only by the next thought and driven by the last.