1. Introduction

During the late 6th through to 5th century BCE, when the majority of the Athenian vases we have today were produced, Athens was a metropolis seeking to expand its hegemonic control over the Greek world and was in constant conflict, first with the Persians and then with other city-states. While this tumultuous history is well known, it is not often connected with Athenian vase-painting and its popularity in domestic and foreign markets, although that is beginning to change with recent publications such as Robin Osborne’s

The Transformation of Athens (

Osborne 2018). Other scholars have focused on the connection between historical periods and specific painters (

Matheson 1995;

Avramidou 2011). The political activity of Athens is intensely tangled with changes in the marketing of Athenian figure-painted pottery long before the 5th century BCE. First, there is the well-established transition from black-figure to red-figure as the leading technique for fine household ceramic objects, a fashion popularized by Athenian workshops in a (successful) bid to replace Corinth as the major Greek ceramic production center for figural pottery towards the third quarter of the 6th century BCE (

Boardman 2001, p. 11). Second, there are significant changes in the depicted subject matter as both workshops and individual artists are producing wares for a wider range of markets in the 5th century, which leads to changes in the messages expressed and how they are conveyed (

Schierup and Sabetai 2014).

Today, we are flooded with messages and images about what to buy, things we “need” to have to be more entertained, more fashionable, more efficient, more comfortable, more healthy… there is always more of something that we should strive to be for modern cultural standards, even if the actual product might be stretching that selling point. With regards to modern commercial markets, there is a drive to understand how the market works and how to best target an intended audience. Many studies of ancient markets have focused on the fiscal or logistical aspects of trade (

Gill 1991;

Harris et al. 2016), the export appeal (

Osborne 2001), or the movement of craftsmen (

MacDonald 1981). This interest in markets has resulted in a deeper understanding of how individuals interact with images that are meant to sell an idea. Our cultural standards and expectations are quite different from those of the ancient Athenians, and they often used their images to create ideal representations of social relations, mythical-history, or contemporary events. The ancient Athenians may not have been as bombarded by advertising as we are today, but figured images with intentional messages were present nonetheless. The term “targeted advertising” is a modern construct, of course, but it is useful as it provides a framework, terminology, and set of theories that may be used to discuss target audiences, economic markets, and changes in imagery.

The 5th century BCE was selected as a narrowed focus of analysis for the images of women for three main reasons. (1) This is the time period in which images of women dramatically increase, which deserves further scrutiny. (2) There is relatively decent information about production and provenance of vases dating to this period. (3) The major events affecting the market and population during this period are well recorded, which allows for the analysis to be placed within a historical context. The 5th century BCE is a period of uncertainty including the dramatic effects of extended wars and disease in Athens, but it also has stretches of great prosperity, such as during Periclean Athens. The periods of uncertainty impact the markets, including the production and sale of Athenian vases. During this time, women became increasingly prominent in Athenian vase-painting. Women are regularly the focus of one image or even of a series of images on a single vase. Not only are they represented more often during the 5th century BCE, but also the types of scenes in which they appear became more diverse. The idea that vases were marketed to female viewers is not new. In 1989, Claude Bérard stated that “[a]lthough produced by men, the images painted on vases transmit a much more complex vision of female realities. While it is true that the means of production are masculine, the clientele for these vases consists mostly of female customers. It is to them that the painters address themselves directly, and it is they who express their preferences” (

Bérard 1989, p. 89). Despite this very astute observation and a dramatic increase in scholarship focusing on women in ancient Greece that often includes Athenian vases (most influentially, see: (

Blundell 1995;

Lewis 2002;

Connelly 2007;

Kaltsas 2008;

Theisen 2009;

Lee 2015)), relatively little has been done to document the overall trends or examine how women are addressed in the imagery.

In this paper, I propose that these changes may denote an expanded marketability of vases targeting female viewers. The vase painters target this market by embedding social cues, representing familiar household tasks, and depicting anonymous figures with which women of wide-ranging social statuses could self-identify. These represented activities are not new; rather, they are now more visible in the cultural landscape within Athens. As targeted imagery, these images give perceptible recognition to the increased valuation of women’s work and lives at a time when their roles in Athenian society were essential for the continued success of the city-state. I suggest that these changes also point to the fact that a greater share of the market was influenced by women, either directly or indirectly, and successful artists carefully crafted targeted advertisements visually on their wares to attract that group both locally and abroad. In the present article, I am focusing on the Athenian audience, but it is worthwhile to note that the majority of vases were produced (and recovered) in an export market. The overall proliferation in images of women suggests artists were increasing the appeal of their wares to female customers. Through the collection of vases with Athenian fabric in the Beazley Archive Pottery Database (BAPD), I analyze trends in the changing imagery of women. By linking these changes with the contemporary history, I argue that women became a viable market at a critical political point in Athenian history.

2. Marketing and Advertising

In modern advertising, “the customer is the focal point…because marketing is concerned with satisfying people’s needs …” (

Mackay 2005, p. 7). Even though we are looking at a very different type of market and reception audience, this point remains valid, but I will offer a few caveats. I am not proposing that trends in modern markets are directly applicable to the ancient world, nor am I suggesting that the ancient consumers were exposed to advertisements in the same manner or magnitude as today. That being said, the objects being sold had to have met some type of need or else why would anyone buy them? Abraham Harold Maslow, a 20th-century psychologist, created a hierarchy of needs that objects can fulfill, which correspond to five categories:

Basic physiological needs such as food, warmth, and sleep.

Safety needs, especially protection.

Recognition, such as a sense of love and belonging.

Esteem: Ego needs, representing self-esteem and respect from others.

With regards to the ancient world, these categories can be useful for considering motivations for purchasing these vases. Similarly, we can consider how the images could help fulfill certain needs. Ceramics were used to store food items, but they also could be used as indicators of status or given as gifts, thereby fulfilling an aesthetic need. As such, the items themselves could be classified as filling needs for recognition, self-esteem, and self-fulfillment, or even fulfilling multiple needs at once.

Some of the important ways that modern advertisers try to reach their audience are by creating an emotional connection with the images presented (

Stewart et al. 2007), using visual metaphors to indicate particular desirable attributes (

Zaltman and MacCaba 2007), manipulating consumer memory (

Montgomery and Unnava 2007), and branding (

Keller 2007). Images crafted in antiquity can also reach audiences using similar methods, such as the use of visual metaphors in images of marriage (

Frontis-Ducroux and Lissarrague 2009). Volumes collecting studies about export and market choices provide many examples of vase-painters using these techniques (see the papers within the following edited volumes: (

Lawall and Lund 2011;

Paleothodoros 2012a;

Schierup and Rasmussen 2012;

Schierup and Sabetai 2014;

Stansbury-O’Donnell et al. 2016)). Ancient Greek artists branded their objects through shapes, like the Nikosthenes workshop producing specific shapes meant for Etruscan markets (

Lyons 2009;

Vlachou 2015; and the collected papers in

Eschbach and Schmidt 2016), through inscriptions and trademarks (

Hurwit 2015), and through recognizable images and artist styles (

Matheson 1995;

Mannack 2001;

Padgett 2017). With regards to brands, Katerina Volioti has studied at the visual branding of the Leafless Group. This was a mid-quality workshop working in black-figure at the end of the 6th into the early 5th century BCE. Volioti argues that the workshop uses standardized size, shape, and particular iconography, including satyrs and eyes, to promote their wares and to emphasize their brand (

Volioti 2017, p. 23). The use of specific shapes, size vessels, techniques, or iconography are standard means that workshops created a group identity, a brand, as recognized by modern scholars, but a brand is not the only means to target wares to specific audiences.

In this study, I am more interested in broad trends in the marketing of Athenian painted vases as related to the first few methods used by advertisers: The manipulations of social memory, the use of visual metaphors, and the emotional connection created through the images between object and viewer. In these categories, it is not simply the product itself that is important, as is the case with the branded vessels, but rather understanding the connections between the visual imagery, cultural expectations, and historical context. In modern history, the changes occurring in 5th century BCE Athenian imagery may be more similar to changes in advertisements issued during the World Wars and the post-war periods. The first half of the 19th century CE includes similar times of uncertainty, war, economic booms for some, and changes in target demographics for advertising, much like during the High Classical period. This comparison is meant to serve as a backdrop for our understanding of the changes going on in the 5th century BCE. For instance, during the first half of the 19th century CE, there are dramatic changes in how women are depicted and popular subject matter. There is a movement towards more diverse scene types including women, including contexts in which women were not represented previously. The images represent women taking on roles that had previously been understood as primarily masculine: Farmers, factory workers, drivers, and even car mechanics. These were all professions that needed to continue to keep society functioning while a significant portion of the population was away. This trend begins in World War I, but it is best demonstrated by the iconic image of Rosie the Riveter from World War II (

Figure 1). Additionally, there is an interesting dichotomy between these working images and representations showing women as motivation for young men to join the military, representing more traditional cultural ideals. Similar to the economic environments of World War I and II, the 5th century BCE marks a period with episodes of war, construction, and change in Athens. The economic boom of Periclean Athens in some ways resembles the period between the two World Wars in the United States. For instance, the period of prosperity in Athens brought on by the input of wealth during the Persian Wars and the peak of the Delian League corresponds with the shift in imagery and subject matter preferences of pottery from contexts within Athens, which will be discussed in more depth below. Like advertisers in the early 20th century, Athenian vase-painters found themselves faced with a gender shift in their purchasing market that they needed to target in order to remain viable in a period with stretches of war and of prosperity.

3. Geographic Distribution of Vases

3.1. Overall Distribution and Production of Athenian Vases

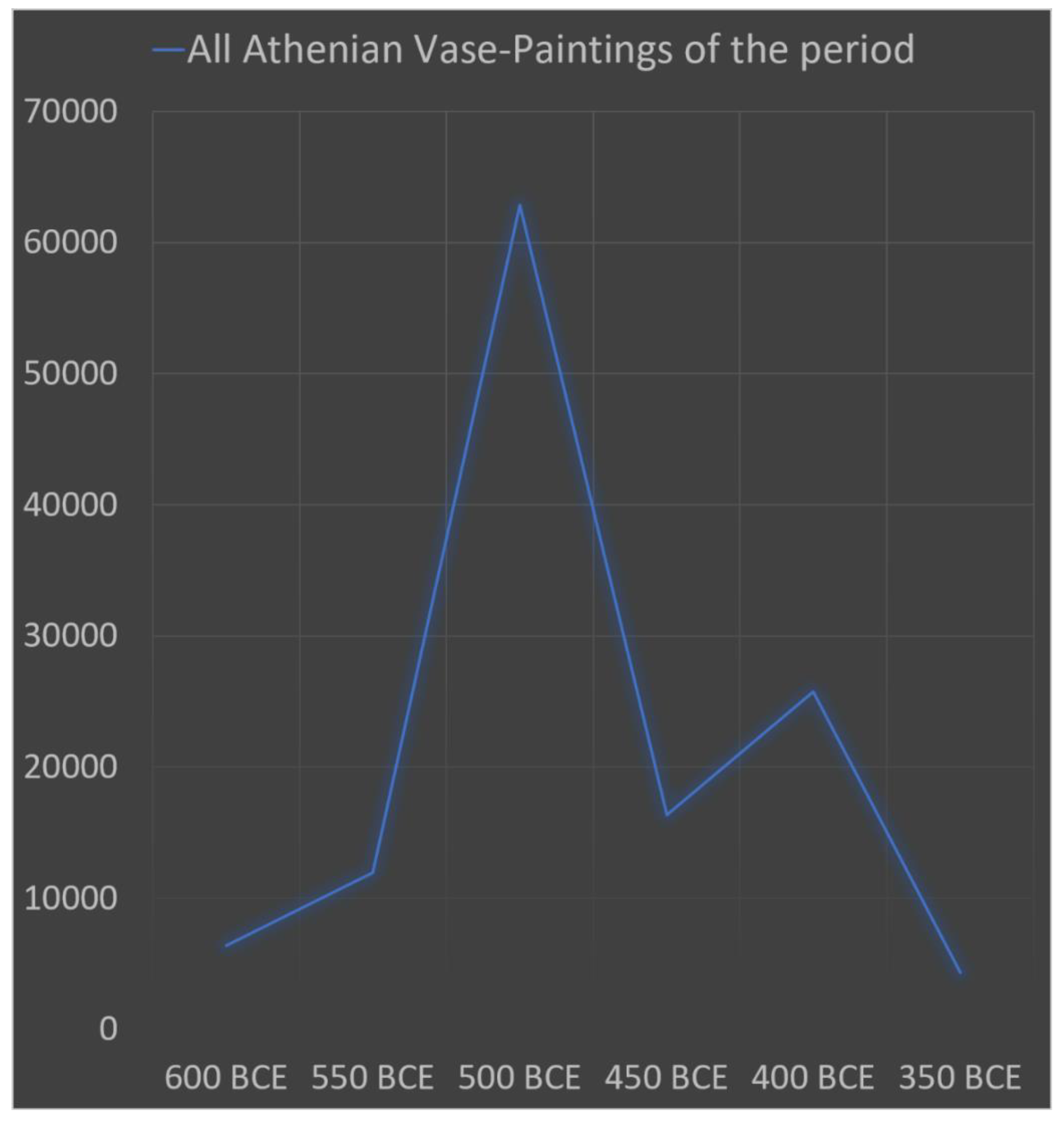

In order to examine the marketing patterns of Athenian vases in the 5th century BCE and to understand the changes in depictions of women in ancient Athens, first we must consider the wider body of vase-paintings in the BAPD. This background provides a greater understanding of broad, overall trends. Previously, such analysis of data from the BAPD was done by scholars examining trends in subject matter and the production of vases (for similar work, see: (

Giudice 2007;

Giudice and Giudice 2009;

Giudice et al. 2012)). When we examine the dates of vases with Athenian fabric in the BAPD, there was an overall dip in the production of vase-paintings after Athens after the middle of the 5th century BCE (

Figure 2). Historically, we can understand this as relating to the wars Athens was fighting, first with Persia and then with Sparta and its allies. Between 460–445 BCE, Athens was fighting with Corinth and the Peloponnesian League during the “First” Peloponnesian War. Vase production, however, seems to remain relatively unaffected during this period. After the start of the second Peloponnesian War, Athens’ population was devastated by the Great Plague in 430/429 BCE (

Pomeroy et al. 2014, pp. 327–32). It was during this period when the slump in Athenian vase production truly appeared to take effect. Athenian production did not fully recover from this slump in the third quarter of the 5th century to reach the pre-Peloponnesian war levels, but trade (and the export market) continues during this time (most recently, see (

Bundrick 2019, pp. 20–50)).

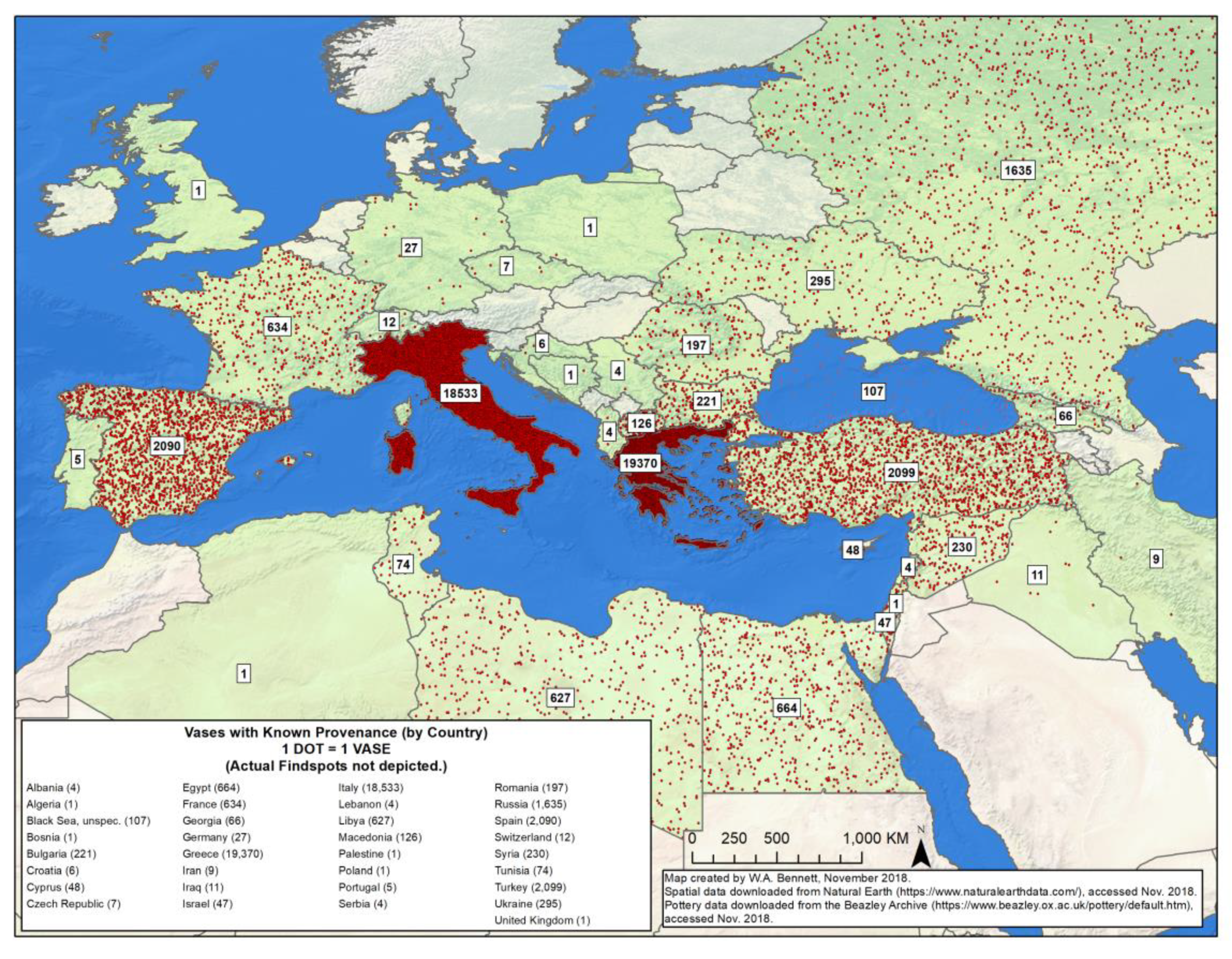

Much of the best-preserved Athenian pottery with known provenance was found not in Greece, but in Italy (

Figure 3). Some of the best examples are those that Etruscans imported and placed in their tombs. That being said, scholars may place too much emphasize on the importance of Attic wares in Etruscan tombs as they do not appear among the vessels depicted in Etruscan tomb paintings (

Small 1994, pp. 38–39). That being said, just over 43% (22,383) of all Athenian vases with known provenance were recovered from Greece (approximately 25% of which are red-figure), while 37.1% (19,056) came from Italy. Together, these account for over 80% of the vases with known contexts. I should point out here that nearly 60% of Athenian vases overall, over 63,000 objects, are not connected to even a general provenance (for some recent discussions on contextualizing some vase-paintings, see the papers collected in (

Rodríguez Pérez 2017)).

When discussing the audience of Athenian vase-paintings, the distribution of the findspots of vases adds yet another layer of complexity. It is unclear to what extent Athenian vase-painters were purposely creating vases for a non-Athenian market or to what extent objects created for a local market were selected and exported by merchants for a new, possibly unintended audience. Studies on the Attic ceramics in Italian contexts, such as Gela (

Panvini and Giudice 2003) and central Sicily (

Panvini et al. 2007), have provided further insights into the types of imagery being exported from Athens, however the intentionality of the vase-painters is still uncertain. The idea of “intentionality” in the ancient world is not without its own difficulties. This has been most recently discussed by Kathleen Lynch who states that “there will always be a foundation of Athenian-ness in the style and imagery of the vases” (

Lynch 2017, p. 126). I agree with Lynch that, even if some vases were produced for an export market, the artists were drawing on their own knowledge to create the images.

3.2. Data and Methodology of the Study

Before moving on to more analysis of the data, it is first important to explain how it is acquired, how it is utilized in the current study, and how the data is limited. In the present study, the data has been compiled and analyzed from the BAPD. By considering the nearly 115,000 vases searchable in the BAPD, we can gain a greater understanding of broad, overall trends. It is also important to recognize that this number includes entries covering a broad range of small individual fragments, joining pieces, and complete vessels in black-figure, red-figure, white ground, and special techniques. Some entries do not have any figures preserved at all. The database also includes some non-Athenian vases. Of those vases, 88,000 have Athenian fabric, which are the focus of the present study. The present article includes all representations on Athenian fabric that include a depiction of at least one woman, as identified by scholars in the database. As such, the data includes images with women appearing in mythological subjects, women as spectators, women in groups with men, groups of only women, single figures, and busts. The data compiled also includes multiple techniques, which were popular at different times, had dissimilar use contexts, and distinct export rates. As only one in four vases being produced were actually recovered within Greece, the present study only focused on a small subset of Athenian vases.

Furthermore, the results were limited by the manner in which the data was entered into the BAPD. This means that, at times, the results in this study may not accurately reflect the current state of knowledge on individual vases as to date or provenance if the BAPD entry had not been updated. There are some limitations to this method of data analysis, but it allows for a broad examination of the imagery and provenance information for a vast amount of data. The faceted search on the BAPD allows for a number of constraining factors to be applied to the data and the search results can be downloaded as an Excel spreadsheet. The limiting factors in the present study included the following terms and date ranges (with appropriate modifiers in the string, such as “and”, “or” “and not”, and “or not”). These terms are defined by the BAPD and are not the author’s creation. Not all terms were in use at the same time and some categories were not limited during broad searches (such as technique).

Fabric: Athenian.

Decoration: woman, women.

Technique: red-figure, black-figure, white ground, silhouette, pseudo black-figure, pseudo red-figure.

Date range: 500–450, 475–425, 450–400, 425–375, 400–350, 375–325.

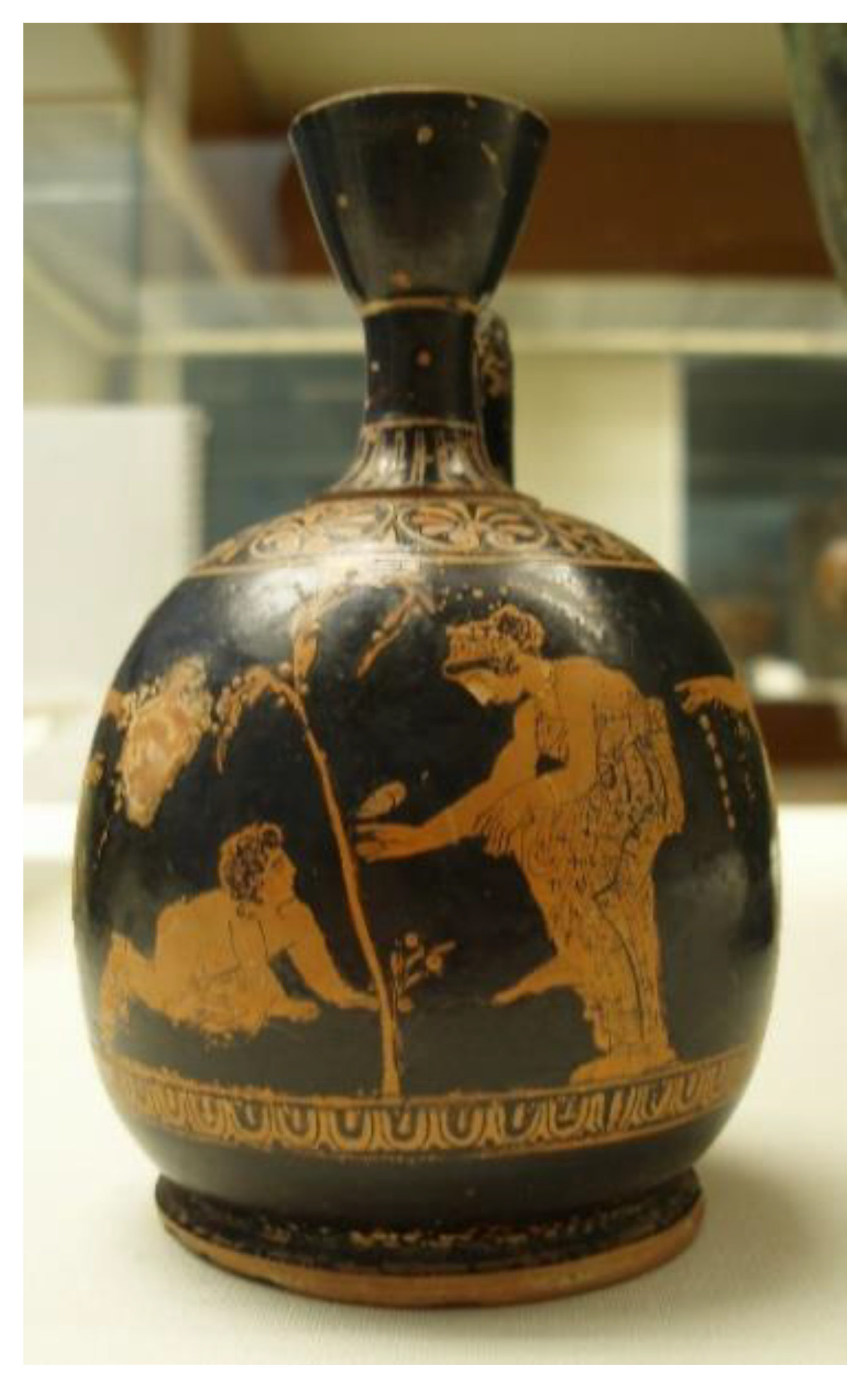

Shape: loutrophoros, lebes, epinetron, kalathos, aryballos, pyxis, along with each of the shape names with the added modifier of “fragment” or “fragments.”

Provenance: Athens, Agora, Acropolis, Ceramicus, Attica, Piraeus, Greece, along with individual cities within Attica, other regions and poleis within Greece as available in the BAPD “Provenance” menu (344 of the available search options fall within Greece).

Provenance is a problematic category within the BAPD entries. Provenance information was not entered consistently into the database, for instance, Athens was not categorized as Greece whereas some areas like Elis were first listed as Greece. This inconsistency created difficulties when trying to analyze the data that required some manipulation by the author to standardize. First, the author spent some time determining which location was intended when place names were ambiguous and the region was not specified in the BAPD entry. Then, the author standardized how locations were referenced by organizing data by region, polis, and then by more specific location details when known. Third, the author distinguished between vases with only generally known provenance, such as “said to be from Athens,” or “Ceramicus (?)”, and those with more established information. All references with “said to be from” or listed with a location followed by a “?” were pulled into a general category, such as “Athens (general)”. Among this general category, some locations were more confident than others, but all were treated similarly. This category was only included with the data mapped and when specifically noted as from a location (general) in charts. Otherwise, these vases were excluded from the analysis.

Dates in the BAPD are confined to 50-year sections, some of which do overlap, and required closer inspection and data manipulation by the author in order to create the charts. Entries were inspected to avoid overlap between the categories. The data in the charts may include vases within 25 years on either side of the given year. This division can be problematic, as it eclipses some nuances, such as the dip in vase production being closer to 430 BCE in

Figure 2. For the present study the 50-year chunks have been kept in accordance with the BAPD. This is because the goal of the present study was to use the data in a manner that can be easily reproduced by others working within the BAPD. Ideally, smaller divisions would be used in future work.

3.3. Distribution of Depictions of Women in Athenian Vase-Painting

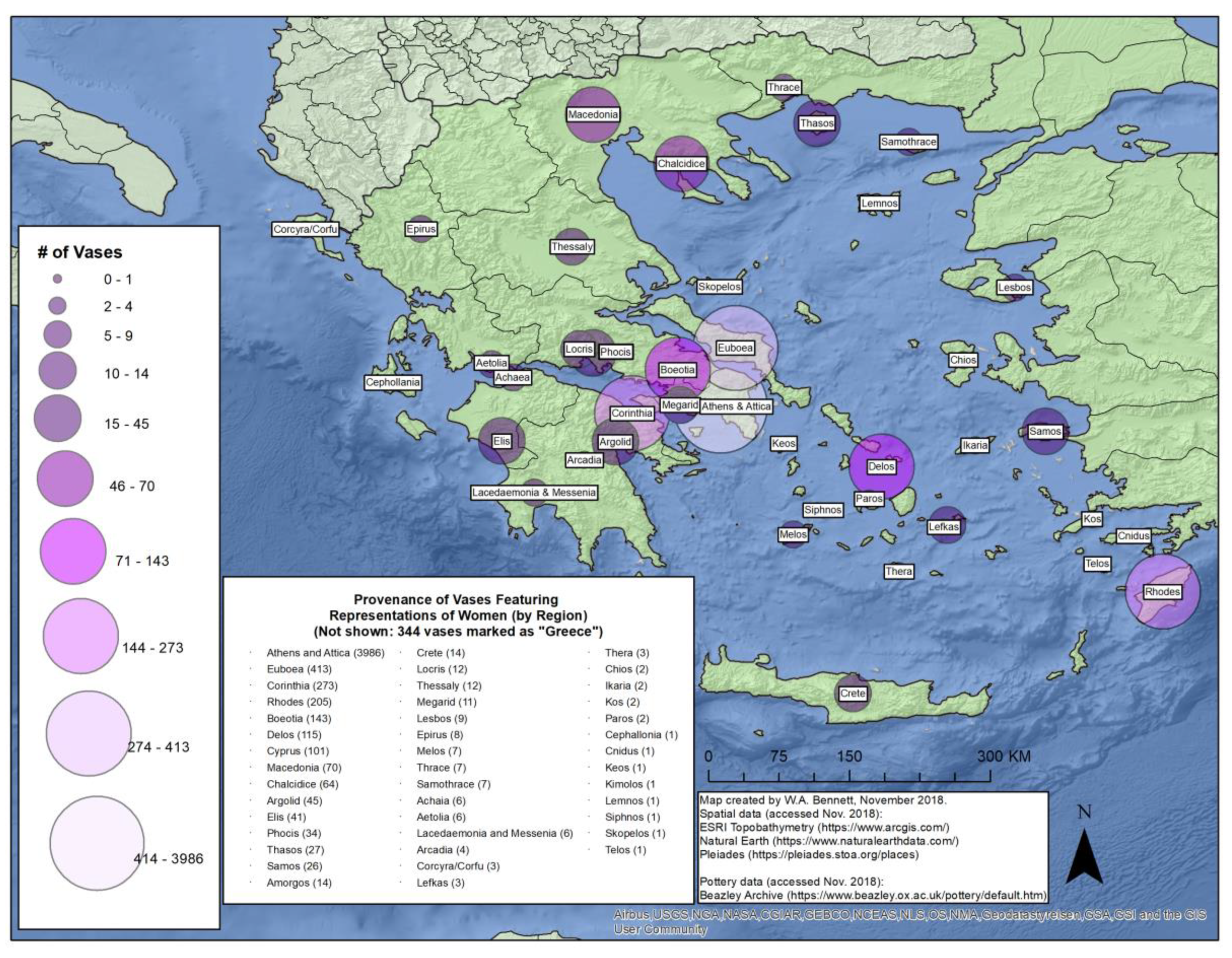

With the limitations of the data in mind, we can now contemplate the representations of women on the vases. When we consider the distribution of depictions of women on Attic pottery from the 5th century within Greece, there is a clear pattern: 66% of the images of women from known Greek provenances come from Attica (which is then accounting for approximately 28.4% of all of the images with known provenance within Greece), and 83% (54.9% total) of those are recovered within the confines of Athens itself (

Figure 4). Nearby Euboea accounts for another 6.85%. From the contested Corinthia comes an additional 4.5%. The islands in the Aegean, to which the Athenian navy was regularly traveling during this time, account for another 9.2% when the islands are considered together. It can be difficult to get into more detailed discussions of context on such a large scale, as the majority of vases do not have known provenance, or they only have a generally known provenance, such as “Greece”. For reference, the vases with a generally known provenance account for another 5.6% of the dataset. That being said, images of women in Athenian vase-painting within Greece are more prominent within the confines of their primary, local market, Attica, with a concentration in Athens itself; however, they also appear in large quantities within the areas in which Athens was involved in militarily, including places where Athens established cleruchies, such as Thasos (in total, 86.2% of images of women in Greek contexts fall into these areas). This supports the idea that changes in how women are depicted is related, at least in some manner, to choices of Athenian vase-painters for their Athenian market.

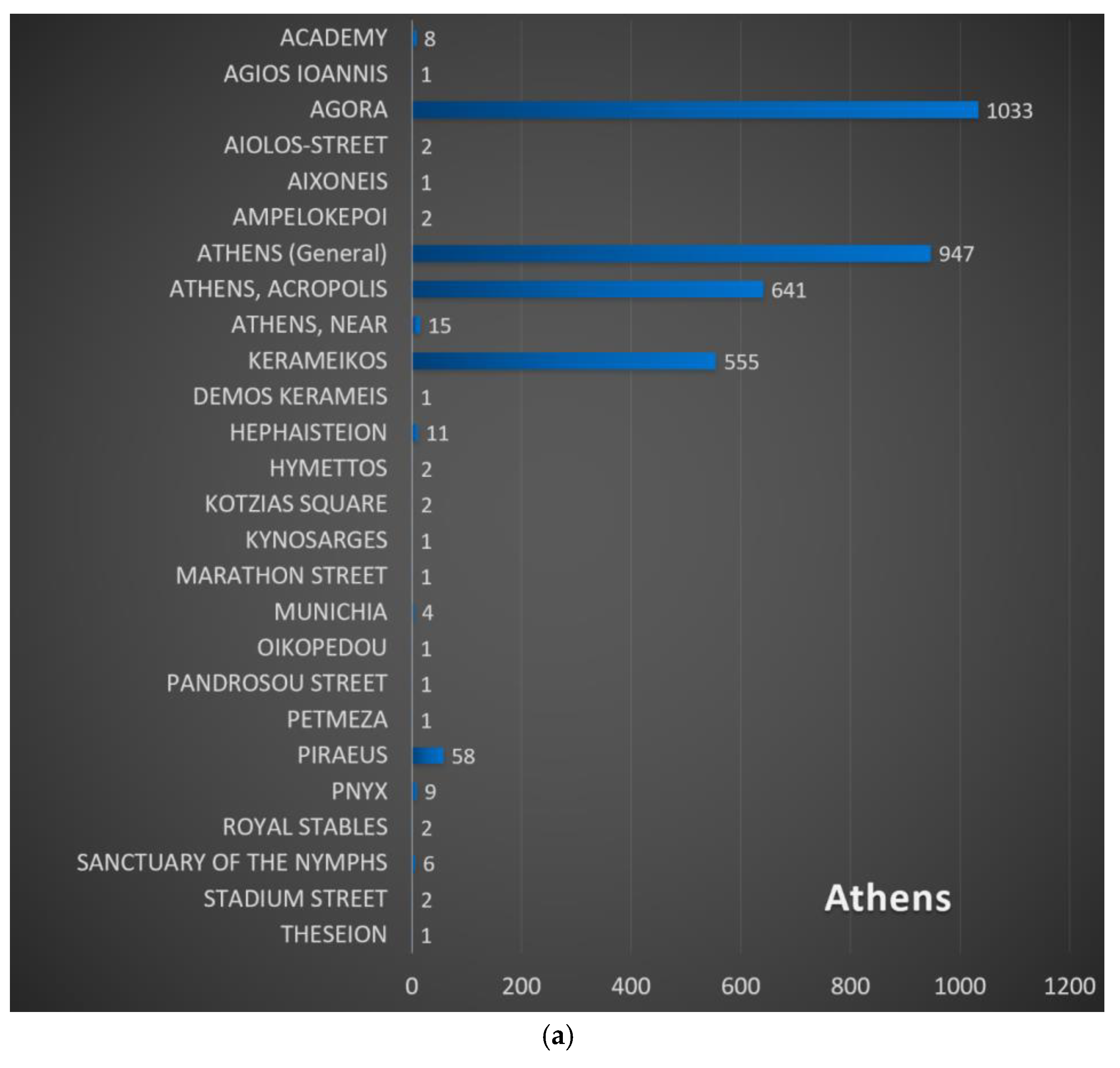

Within Athens itself, two of the best documented areas with long-standing excavations include the Athenian Acropolis (

Pease 1935;

Roebuck 1940;

Pala 2012) and the Agora (

Sparkes and Talcott 1970;

Moore and Philippides 1986;

Rotroff and Oakley 1992;

Moore 1997;

Rotroff 2006; and regular reports in

Hesperia). Additionally, the Metro excavations (

TAPA 1997;

TAPA 1998;

TAPA 1999;

TAPA 2000) and the long-standing excavations in the Kerameikos (reports in

Kerameikos: Ergnebisse der Ausgrabungen) provide abundant provenance information for Athenian contexts. The following charts illustrate the relative distribution within Athens itself and more widely within Attika (

Figure 5a,b). While the relative abundance of images of women in spaces like the agora may be surprising, I would like to suggest that this increase in the main marketplace correlates to the growth of women as the intended consumers of these vases, even if they are not the ones directly purchasing them. The agora may also be skewed by production areas within the marketplace as well as numerous deposits with Persian destruction debris (

Shear 1993, p. 38). Within sanctuaries such as the Acropolis, women could view these vases after they were dedicated. Simply viewing vases in a sanctuary is not on the same intimate level as repeated viewings in the house, but it does represent another type of interaction. Fragments of loutrophoroi and lebetes gamikoi have been recovered from the Acropolis. Elisabetta Pala states that these shapes seem to be appropriate votives from women (

Pala 2012, p. 214) and the Acropolis pieces, especially those on the South Slope, also mostly feature women in their imagery. Similarly, there appear to be connections between dedications of epinetra and the sanctuaries for female deities (

Kousser 2004, p. 101) as well as of kalathos dedications (

Trinkl 2014, p. 194).

The shapes associated with women that are found at sanctuaries are also appropriate at graves. Both loutrophoroi and lebetes gamikoi are found in graves of the Kerameikos, along with lekythoi, aryballoi, and pyxides (

Knigge 1988;

Walter-Karydi 2015). Kalathoi have also been recovered from graves within the boundaries of Athens (

Waite 2016, p. 43). On grave goods, wedding, adornment, and domestic scenes appear suitable as representations of a woman’s social status. The iconography of the wedding is particularly prominent on funerary offerings (

Walter-Karydi 2015, pp. 208–21). Recently, Katia Margariti has questioned the association of loutrophoroi as grave offerings for unmarried maidens in grave reliefs. Margariti emphasizes the fact that loutrophoroi were also associated with men in funerary contexts, specifically in the form of the stone loutrophoros-amphora, while the loutrophoros-hydria is associated with women (

Margariti 2018, pp. 94–98). In general, as grave goods, vases including those with wedding imagery and household scenes on the vases and their related shape appear suitable as a representation of the social status of the woman or as signposts for particular cultural ideals. As Margariti’s exercise shows, however, we need to keep in mind that they might also be used in unexpected ways or that there might be nuances to their significance that we have misunderstood.

Within Attica, find contexts that involve vases that include representations of women, as limited as they are within the broader scope, indicate that the vases could be seen in a variety of ritual and funerary situations as well as within the home. Domestic contexts are poorly documented, so our contextual information is skewed towards more public areas (

Boardman 2001, p. 245). We should keep in mind that women were also the ones who probably handled at least some of these objects on a semi-regular basis: Within the home, at family tombs, and in sanctuaries. Although contextual evidence is limited, it reveals that women could interact with these objects in a variety of ways, whether through direct usage in daily life, in ritual activities, or through cleaning and storing items primarily used by others. Furthermore, these interactions could take place in a variety of settings and for different reasons. If women are interacting with these objects, in one way or another, and targeted by the imagery, we should also give some consideration to how they are interacting with them that could affect our interpretation of the vases.

4. Shapes, Images, and Subject Matter

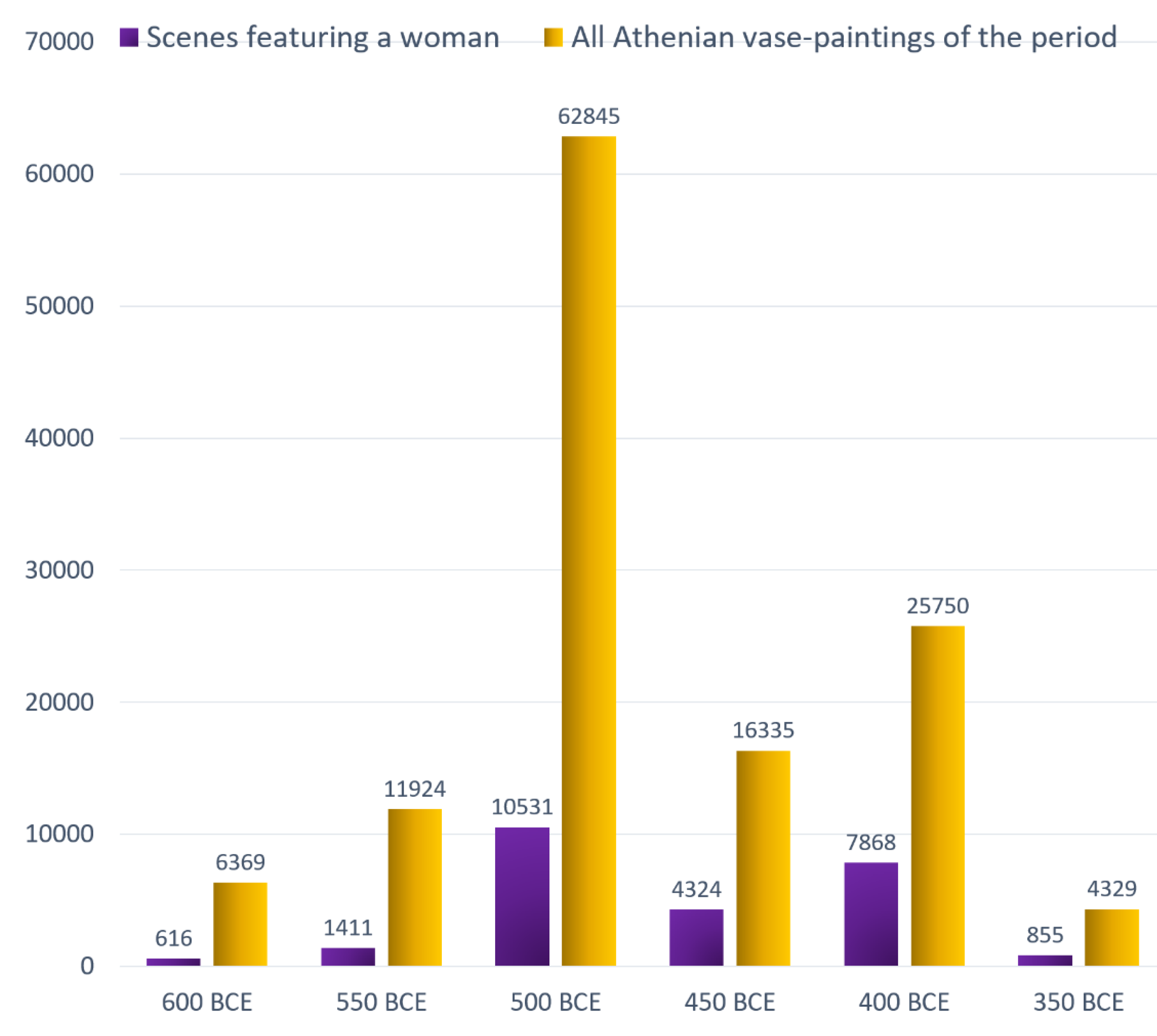

During the 5th century, vase shapes primarily used by women were increasing. There were also changes in how women were represented visually. Overall, women appeared in vase-paintings more often during the 5th century BCE than previously (

Figure 6). In fact, there was a huge jump between the 6th and 5th centuries BCE in the number of vase-paintings that included women. In part, this dramatic jump is related to the increase in the production of Athenian figured pottery around 500 BCE. In order to understand the increased visibility of women in the imagery during the 5th century BCE, we should consider the relative proportions of images of women to overall known images during each period. When we do so, women now appear in 26% of vase-paintings in the 5th century BCE, compared to only 11% in 6th century BCE (as determined by the author’s own analysis from the data available in the BAPD).

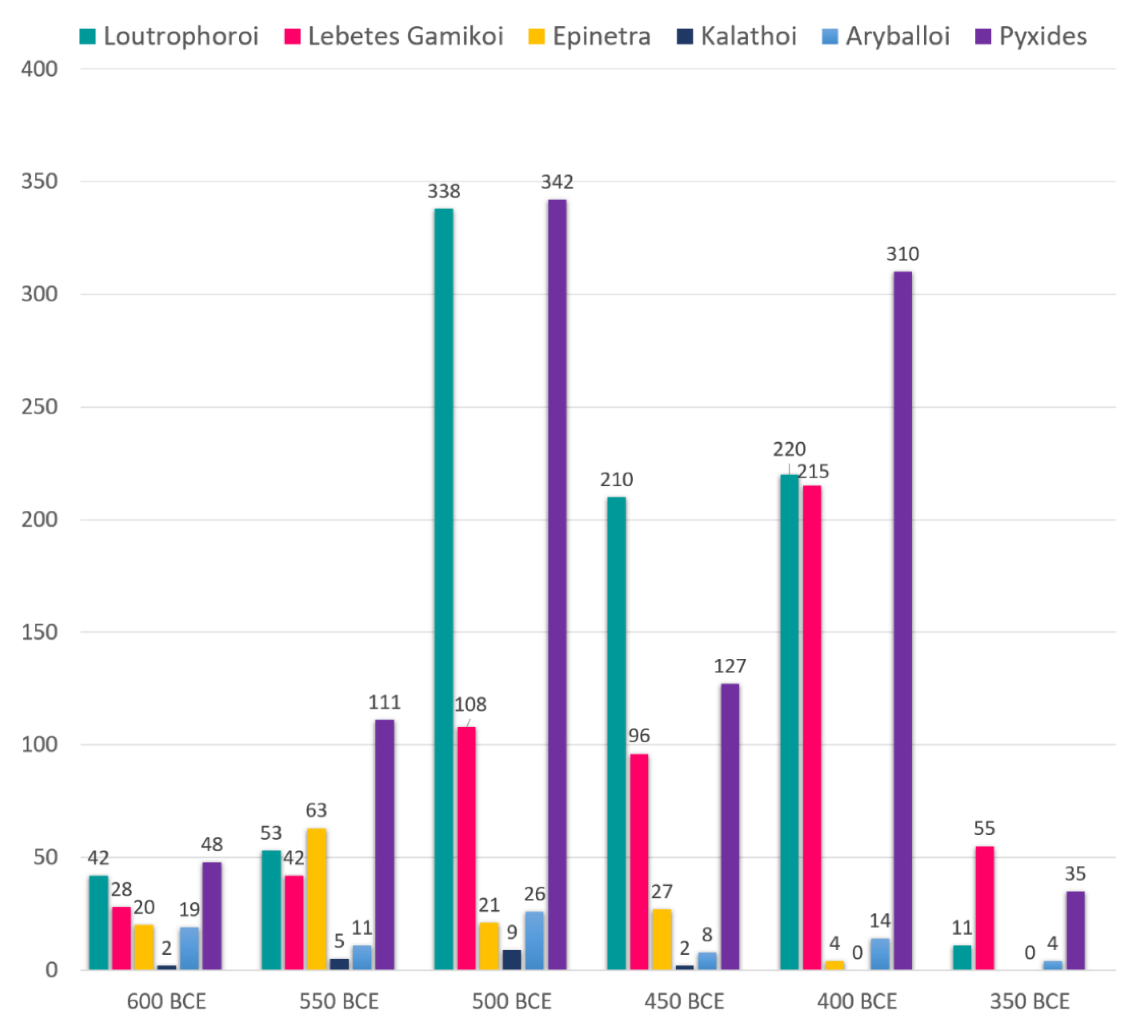

Among the shapes rising in popularity in the 5th century BCE thought to have been used primarily by women were those related to weddings (

Smith 2005,

2011), like loutrophoroi and lebetes gamikoi (

Oakley and Sinos 1993;

Sabetai 1993;

Winkler 1999), those for use within domestic setting, such as pyxides, aryballoi, kalathoi, and epinetra (

Láng 1908;

Richter and Milne 1973;

Kanowski 1984;

Mercati 2003;

Heinrich 2006;

Moormann and Stissi 2009;

Tsingarida and Bavay 2009;

Trinkl 2014;

Waite 2016), and those used for funerary assemblages, such as the white ground lekythoi (

Kurtz and Boardman 1971;

Kurtz 1975;

Oakley 2004;

Schmidt 2005;

Arrington 2015). In general, these shapes became more prevalent during the 5th century BCE (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). There are some other interesting trends among these shapes: Only six loutrophoroi came from known contexts in Italy, while 120 of these were associated with provenance within Attica; similarly, 15 lebetes came from Italy, while 147 were from sites within Attica. This suggests that some vases were created for a more local market and only occasionally were exported.

Along with the general increase in the depictions of women, women were regularly the focus of one image or a series of images on a single vase, rather than simply appearing as spectator figures as was the case in the 6th century BCE (

Stansbury-O’Donnell 2006, pp. 187–229). During the 5th century BCE, much of our information about the lives of women is filtered through male perspectives, such as Xenophon’s

Oeconomicus and plays such as Aristophanes’

Lysistrata and Euripides’

Trojan Women. Textual sources during this period provide only a small sample of the words of female poets preserved in fragments, such as Corinna, Telesilla, and Praxilla, who may date to this period (

Lefkowitz and Fant 2005;

MacLachlan 2012). Therefore, most of what we know about women comes from male perspectives, excavations, and representations. Some of the most dramatic changes in the images of women are those within wedding scenes. The wedding was an important cultural event and involved rituals distinctly tied with the increased importance of legitimate, citizen children (

Ferrari 2003a, pp. 27–28, 35–36; additional primary sources can be found in (

Lambrinoudakis and Balty 2004)). It marked a significant transition: A literal movement from one household to another, as well as marking the change from youth to adulthood for young women (

Ferrari 2003b, pp. 46–47, 50). The importance of citizenship status was clearly a concern in the 5th century BCE, as attested by our sources discussing changes in Athenian citizenship laws. The

Athenian Constitution, 26.3-4, in the mid-4th century indicates that the Citizenship Law of 451/450 BCE, as proposed by Pericles, confined citizenship to persons of citizen birth through

both parents. Female citizenship now helped determine who could be heirs, who could inherit property, and who could become citizens in Athens. Laura McClure has noted that, while women are now recognized as citizens, as

attike, female citizenship is entirely dependent on “an inherited, familial connection rather than a political affiliation” (

McClure 1999, p. 22). The citizenship law was amended in 430/429 BCE, during the time of the plague, in order to allow the “adoption” of

nostoi as male heirs, which was initiated by Pericles (

Carawan 2008, p. 298). Even with these adjustments to the law, the citizenship of women and married unions between citizens remained significant for the future of Athens.

The citizenship law reveals that, in the first half of the 5th century BCE, when Athens had increased its hegemonic sphere of control and was relatively prosperous, people were immigrating to the city and intermarrying with local citizens so much so that by the mid-century Athens found it necessary to limit citizenship. In turn, the law emphasizes the importance of citizen women, “proper” marriages, and legal heirs. The citizenship of Athenian women was different from that of men. It came without the same political expectations, rights, and requirements. Citizen women did receive some considerations, such as the ability to participate and serve in public religious roles (

Connelly 2007, pp. 27–56). The change in citizenship, the increased interest in women’s health, and the expanded discussion of cultural expectations for upper class women in textual sources indicates an amplified awareness of women’s roles in Athenian society.

Correspondingly, images of weddings and preparations vault from below 30 preserved representations to over 400 during the 5th century BCE (

Figure 9). Eighty-five of these come from contexts within Attica, a further 24 from other Greek contexts, but only 36 from Italy, including the Greek cities in Magna Graecia. That being said, only 16% of known subject matter on loutrophoroi can be certainly identified as wedding iconography. In part, this is because many of the known loutrophoroi are fragments with unidentified scenes, uncertain identifications, or only parts of single figures preserved, but other depictions include funerary scenes and some mythological scenes. Among lebetes, only 7% specifically represent identifiable weddings, but another 20% include general domestic scenes, some of which have

erotes and

nikai present.

In these images, the bride and groom typically appear to be close in age (

Figure 10) and small

erotes, or cupid-figures, often appear near the couple (

Figure 11). These images create a more romanticized view of a cultural practice that was often a political arrangement, rather than a love match, between people that might in reality differ in age by more than 20 years. Images of weddings most commonly appear on vase shapes that women could have used, including wedding shapes and multi-purpose vessels appropriate for domestic, ritual, and funerary contexts.

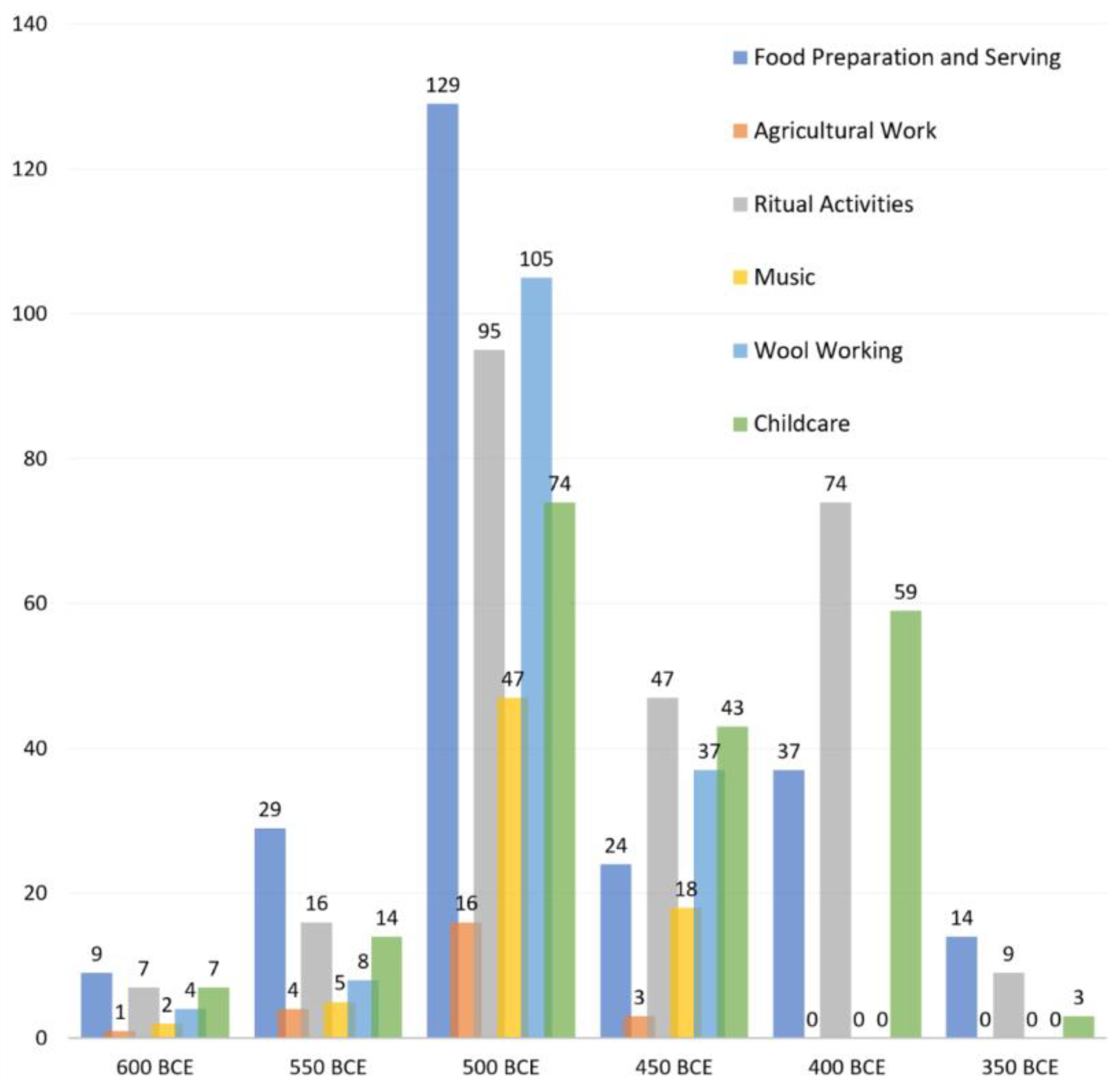

Alongside the rise of wedding imagery, there are a variety of inventive scene types that appear in the 5th century BCE. The scenes include representations of food preparation and serving, agricultural work and pastoral views, ritual activities, wool working, music making, and childcare, among others (

Figure 12). On this chart, 40.7% (383) of these vases are exported, with the most significant group being that depicting food preparation and serving (85.7% of that sub-category and 54% of the exported vases in these categories). Of the vases from Greek contexts, 59.3% (557), there was a concentration of 402 vases having Attic provenance (42.8% overall and 72.2% of this group came from Athens). The new scene types included tasks that may be considered as culturally expected chores for women at this time. They were not regularly depicted previously. They may have been considered too ordinary to be the regular spotlight of figural decoration, or perhaps they were considered of less interest to a male audience who did not perform those tasks. The tasks are not new; instead, they are now more visible in the cultural landscape on account of contemporary historical events.

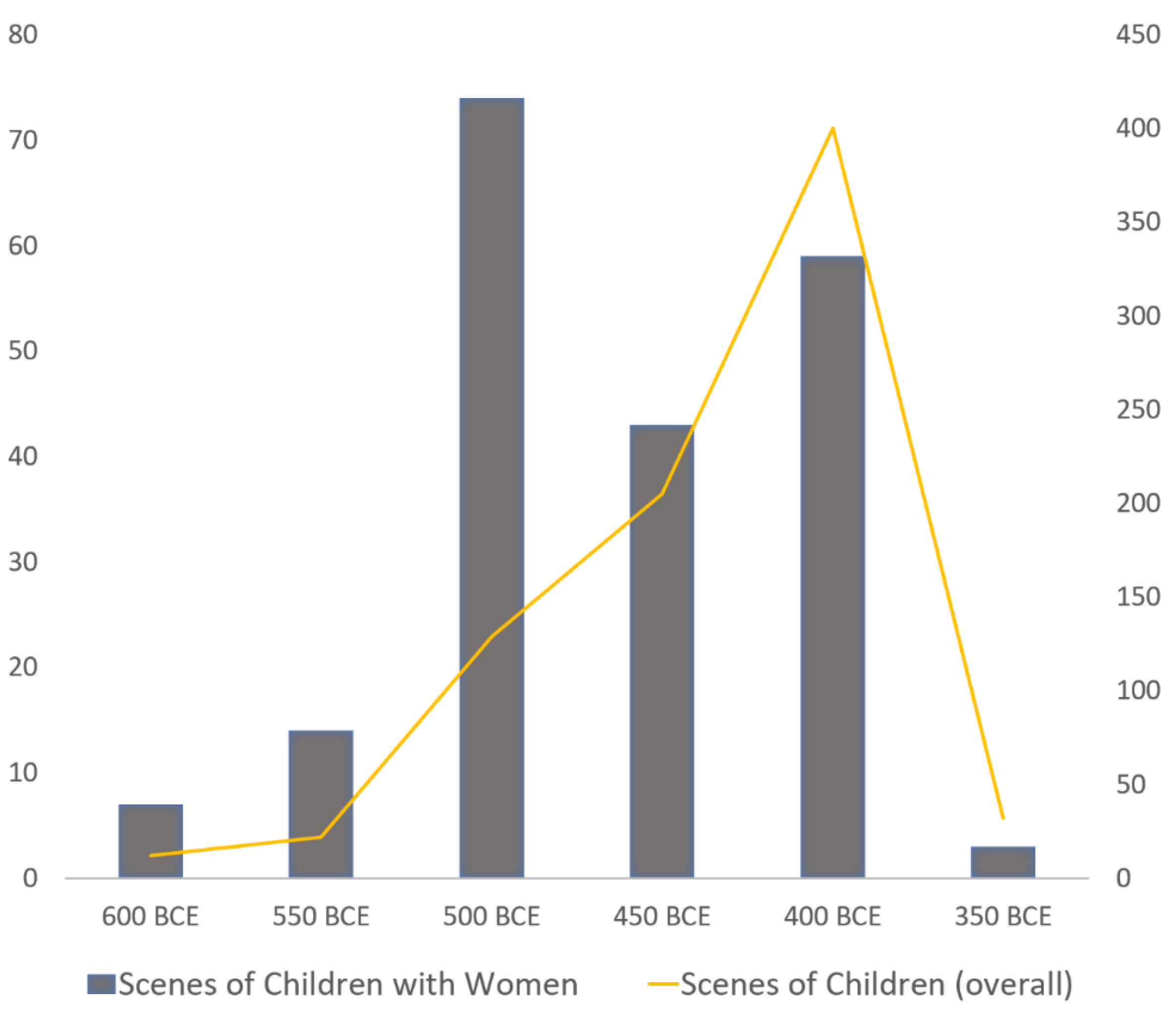

The appearance of agricultural, food preparation, and serving imagery seems to correlate with an increased interest in showing scenes of daily life during this tie. The trend is especially apparent in the vases by specific painters such as the Pan Painter, such as food serving. These scenes fall among the group primarily exported and only a few examples are found in Greece. Children, on the other hand, and childcare scenes are more ubiquitous in their appearances. Children increasingly appear in vase-painting beginning around 500 BCE and peak in popularity around 400 BCE (

Neils et al. 2003;

McNiven 2007;

Pritchett 2017). Images of a woman with a child, on the other hand, are more common around 500 BCE, but consistently appear until around 350 BCE (

Figure 13). During the 5th century BCE, images of small children and women typically included a child playing while observed by small groups of women (

Figure 14), being handed to/by a seated woman who is usually well dressed, participating in processions. The child is often more prominent, appearing in the center of the images, rather than relegated to the sides. These women and child images visually emphasize the female roles of motherhood and family. Pregnancy and childbirth do not appear in the images, with the exceptions of depictions of the birth of divine figures such as Athena or limited depictions of childbirth in funerary reliefs. While the depictions of women with children are not found exclusively in Athens, 64% of the vases featuring women and children with known provenance are from Athens and the broader Attic region. Children are particularly important in Athenian society at this time, especially after the population devastation of the plague, and the increase in representations echoes their significance. It is not simply the fact that it was important for women to have children, but that it was imperative to have legitimate children, who can be heirs to the

oikos.

Among household tasks, women were expected to manage the

oikos and produce textiles for domestic needs, as such weaving was a significant and necessary chore. Sian Lewis has noted that, in literary sources, “wool-work functions so much as an ideological marker across all media: literature, epitaphs and art. Spinning and weaving are the tasks which mark women as both female and virtuous …” (

Lewis 2002, p. 62). Taking this further, Mireille Lee indicates that “[s]pinning and weaving are exclusively feminine activities in the iconography …” (

Lee 2015, p. 91). Furthermore, it had strong associations with the “feminine ideal”, even though these images represent a fanciful understanding of textile production (

Figure 15). Tasks associated with textile production, including spinning, strongly features in representations of women (

Ferrari 2002, pp. 35–60). The depictions of women actively working wool are popular in the early 5th century BCE, however they become less fashionable as other subjects featuring women rise in popularity (

Bundrick 2008, especially p. 288, Table 1 and p. 291, Table 2). As actual production scenes decrease in popularity, subtle indicators of this household chore remain in the images in the form of objects, like kalathoi and unused looms, which act as visual metaphors signposting the feminine ideal.

Briefly, it should be noted that, thus far, the author has not studied images involving nudity of women in Athenian vase-painting as a distinct category. This is for several reasons. (1) As the study of women in ancient Greece has expanded, researchers have dealt with this topic in much more depth than can be covered here. This scholarship includes many authors that appropriately problematize the idea that nudity indicates a woman’s status as a hetaira (among these, see in particular: (

Keuls 1985;

Bonfante 1989;

Kilmer 1993;

Koloski-Ostrow and Lyons 1997;

Stewart 1997;

Neils 2000;

Kreilinger 2006;

Glazebrook and Henry 2011;

Paleothodoros 2012b;

Robson 2013;

Vout 2013;

Blondell and Ormand 2015;

Glazebrook and Tsakirgis 2016)). (2) While female nudity is more prevalent in the 5th century BCE, it typically occurs on limited shapes and those shapes often appear to be targeted at a male audience through their sympotic functions. (3) Scenes featuring female nudity are more often found on exported vases, and no example is recovered from the Persian destruction deposits (

Lynch 2009, p. 160). Overall, female nudity decreases over time. It can be identified in scenes that are clearly identified as containing explicit sexual acts, here clearly indicated as erotic scenes. Female nudity also occurs in other scenes (

Figure 16), such as bathing scenes (

Sutton 2009), which may or may not be considered erotically charged.

5. Targeting Female Viewers

The information collated in the present study indicates that women are indeed more prevalent in Athenian vase-paintings produced during the 5th century BCE. When we focus on imagery that would be directed more towards women in Athenian markets, which is to say by excluding the imagery primarily exported such as the cooking scenes and representations of female nudity, there were strong trends in the subject matter. These trends may constitute targeted advertising carefully crafted by the vase-painters. Vase-painters would recognize that women could interact regularly with their wares. In fact, the pairing of images of women on shapes that women could have frequently encountered in the home, at tombs, and in sanctuaries suggests that women are now intended consumers of both vase images and their shapes for some contexts, supporting Bérard’s long ago statement. Changes in the imagery to include more familiar subject matter and anonymous females on a variety of vases demonstrate that vase-painters are considering marketing their wares to a broader, perhaps gendered, audience. The depictions of women in these images include only minor changes in dress and general adornment that do not make the social status of each figure clear. These details keep each figure rather anonymous. The visual message present images as advertisements for a cultural ideal rather than a reality. That idea is how to be the “best” version of your societal role using images that applies to a variety of social expectations, recognized activities and settings, and largely depicting undistinguished women.

Jonas Grethlein explains that “[a]ncient visual culture was not only highly invested in the immersive quality of pictures, it also contemplated intensely the ambiguity of ‘seeing-in.’” (

Grethlein 2017, p. 191). This concept of ‘seeing-in’ indicates that when looking at an image, even when it is meant to be immersive, we are aware of the represented objects within the image as well as the medium itself (

Grethlein 2017, pp. 158–59). In most of the Athenian vase-paintings, the setting is often ambiguous or only hinted at with selected features. The indefinite setting appears even when the image is meant to invite viewers to see themselves in the same situation. Purposeful ambiguity of space and identity supports the idea that these more generalizing images may have allowed the artists to target a wider audience by letting viewers mentally complete the details through seeing-in. These images still sell an idea, like being the best at weaving or the most beautiful bride, but the space itself is flexible. In order to expand the market for these vases, artists needed to include imagery that could be broadly adaptable to a variety of contexts within Attica, other regions in Greece, as well as to foreign markets. If artists allow the audience to fill in most of the details, then they are not alienating audience members with the inclusion of specific, unfamiliar indicators of setting.

The images and targeted advertising give perceptible recognition to the increased valuation of women’s work and lives at a time when their roles in Athenian society were essential for the continued success of the city-state. War kept male citizens away from their households, at least seasonally, whereas women stayed in the city. Previous scholarship has considered the influence of the Persian Wars on changes within Athenian iconography and subject matter (

Giudice and Giudice 2009, p. 58), but does not connect these changes to the growing leadership role of Athens in the Delian League, tensions between Sparta, Athens, and their allies, the frequent absence of many men in Athens, and the actual onset of the Peloponnesian Wars. I believe that these may be a more direct influence on changes in iconography in the 5th century BCE that has been previously credited. It is during this time that there now seem to be images crafted for women beyond simply wedding imagery. These products make their gender-targeting clear through culturally accepted means, much like targeted products in modern society. We can identify the wide variety of shapes that include images targeted to female viewers, representing familiar activities and cultural events. These events, ranging from daily tasks to special events, are all occasions when women would engage with these objects.

6. Conclusions

The evidence presented emphasizes the fact that women were important in 5th century BCE Athens. Women were recognized as increasingly fulfilling needed roles within Athens at a time when the attention of Athenian men was focused outward. The shifting trends of the imagery on vases during the volatile 5th century BCE encourages female viewers to self-identify with depicted figures and emphasizes the social importance of particular cultural practices in Athenian society. This self-identification, encouraged by the concept of ‘seeing-in,’ creates a more direct connection between object and viewer. Ancient viewers can draw on their own life experiences in order to contextualize the details of the image. Thus, the vase-paintings both construe and visually reinforce particular social expectations in a period when those social expectations are still in flux owing to changing political circumstances.

When we consider the overall distribution of Athenian vases representing women and the history of Athens in the 5th century BCE, alongside the changes in imagery, it leads to the conceptualization of advertising for a gendered targeted market. In order to reach their audience and mitigate market risks as much of possible, ancient vase-painters stick to traditional iconography and social expectations, with some important changes. They expand the range of their subject matter to reach more of their potential market at home. This local market includes females who are at home during the wars that Athens became embroiled in during the 5th century BCE. While vases with representations of women were still not the majority, women appear on 26% of vases produced during this time, indicating a larger market apportion than in the previous century. The images on the vases were not advertisement in the modern sense, meaning that they entice the viewer into buying a particular commercial good. Instead, the images were intended to represent the “best self” for society, thus appealing to a wide variety of buyers. It was not only wedding imagery that was targeted at a female audience during the 5th century BCE, but rather a much broader range of subjects. Furthermore, the vases were not only viewed within the home and, in fact, were most commonly found (and recorded) in non-domestic contexts. Thus, in order to attract as many buyers as possible, vase-painters needed to craft imagery that could be suitable for multiple contexts, carrying a multiplicity of meanings.

The images on these vases reinforce ideas about belonging to particular social classes, could serve as icons of an individual or family’s status to others, and also reflect purchases based upon aesthetic choices, as is the case in the selection of grave goods. Some of the vases might ostensibly have been purchased for their functional purpose as well. These vases meet multiple “need” categories as defined in modern advertising. The images reinforce these needs by showing women in culturally accepted (and expected) roles, paired with an idealization and romanticized view of these tasks. The depictions of the women use visual metaphors, such as the inclusion of items related to textile production, to emphasize desirable attributes. At times, these depictions even manipulate consumer memory to represent idealized and romanticized depictions of events, such as weddings between a woman and a young man who lovingly gaze at one another. In order to create an emotional connection, the vases and images encourage the viewer to interact with the represented reality. The image elicits a response, prompting memories and expectations based upon common experiences and shared cultural knowledge. The vase-painters create this emotional engagement through visual markers that imply connections through familiar subjects, settings, activities, and behaviors. The viewer can interact with the vase, and the images visually prompt the viewer to bring in his or her own personal experiences in to filling in the details.

Changes in the imagery at this time both reveal and visually reinforce cultural expectations to an intended audience, which, in this case, is a gendered audience rather than the trade-targeted audience. Depictions of the female figures focus upon the task at hand, whether that is preparing for a wedding, caring for children, or performing domestic work in the home, among others. These images serve to entice viewers into placing themselves among the represented experiences, just like how modern viewers are sometimes expected to visualize themselves within the setting of a commercial or advertisement… but, only if they buy into the product! I suggest that we think of these vase-paintings as important bearers of meaning, like advertisements. We must decode the advertisements because they are, after all, selling something and the vase-painters are carefully targeting their audience.