Abstract

Based on an archaeological analysis of part of the buildings that make up the “private” sector of the Qaṣr of Madinat al-Zahra, we offer you an overview of the people who lived and worked there on a daily basis. We conclude that it is possible to identify four types of resident: the caliph and the heir, the high functionaries of the state, the functionaries who supervised the domestic maintenance tasks and, finally, the servants who carried them out.

Keywords:

Al-Andalus; Umayyad caliphate; Madinat al-Zahra; Qaṣr; servants; ḥājib; heir; caliph; Service Houses 1. Introduction

The founding of Madīnat al-Zahrā’ in 936 or 940 is associated with the self-proclamation of cAbd al-Raḥmān III as the first caliph of al-Andalus in the year 929. The new city was located near Córdoba and that sought-after proximity meant that, in some respects, the two cities shared the status of capital of the state. Among other aspects, the most visible manifestation of this was participation in the ceremonial royal court that involved both centres. The city was abandoned and partially destroyed between 1010 and 1013 as a consequence of the events of the fitna that saw the beginning of the disintegration of the Umayyad caliphate.

Over a century of investigation at Madīnat al-Zahrā’ (beginning in 1911) has focused mainly on the Qaṣr (Alcazar) and has revealed the diversity of buildings that made it up and that we can see today.1 From a functional point of view, the Qaṣr was the seat of power.2 As in other dynastic capitals of the time, including Bagdad, Ṣabra al-Manṣūriyya, and Cairo, it combined three main functions: the residence of the caliph and the heir,3 the seats of the principal institutions of the Umayyad state administration and the ceremonial and political representation centre. All these functions were shared at one time or another with the city of Córdoba (Mazzoli-Guintard 1997; Acién Almansa and Vallejo Triano 1998).

The large administrative and political representation edifices have been analysed to a greater or lesser extent and have been identified with more or less certainty.4 From a chronological point of view, these official constructions—together with the nearby buildings that make up their respective terraces—were not part of the first construction or foundational phase of the Alcazar undertaken in the 940s, but a result of the major urban reform carried out in the middle of the 950s (Hernández Giménez 1985, pp. 21–24, 44–46; Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 465–501).

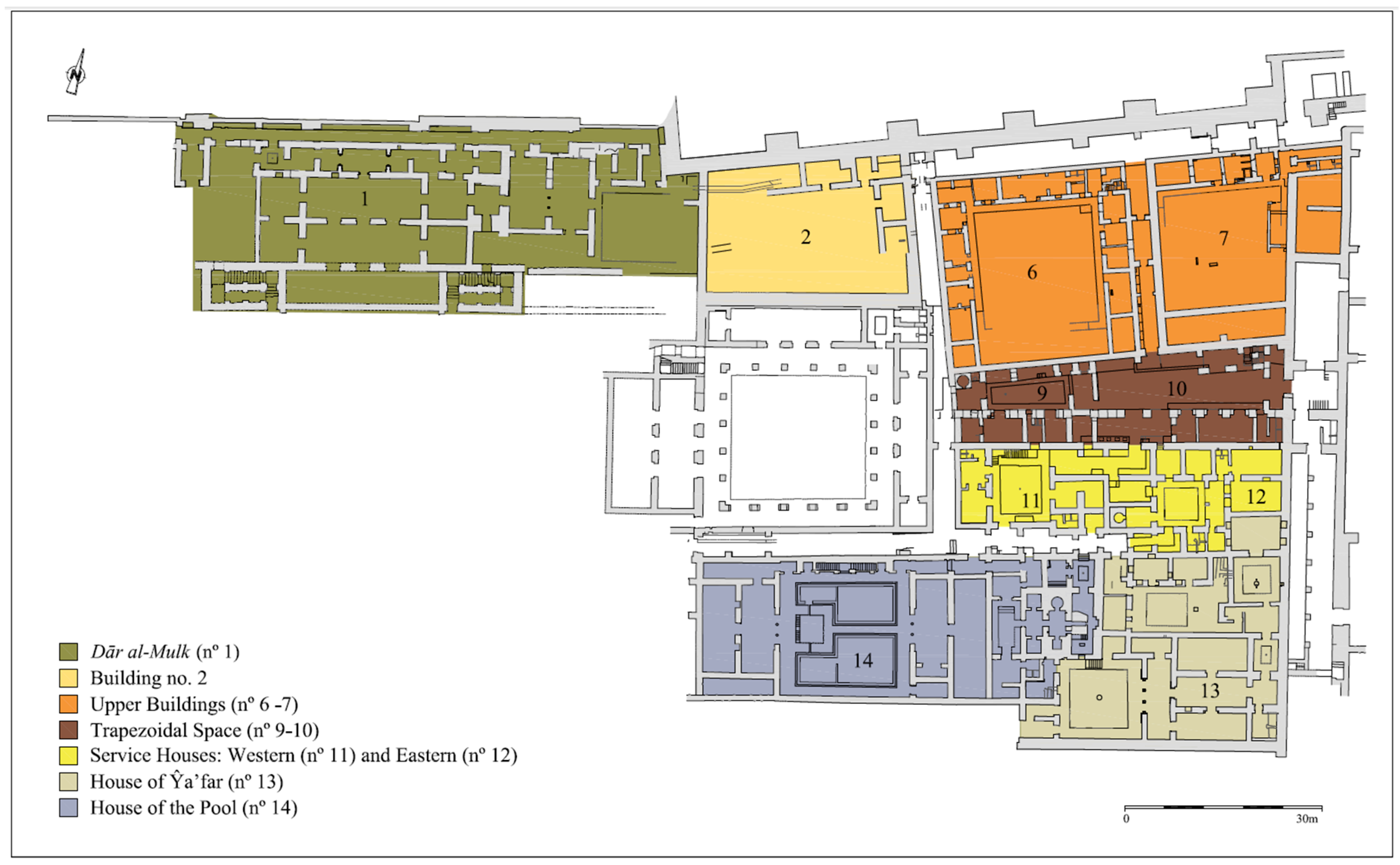

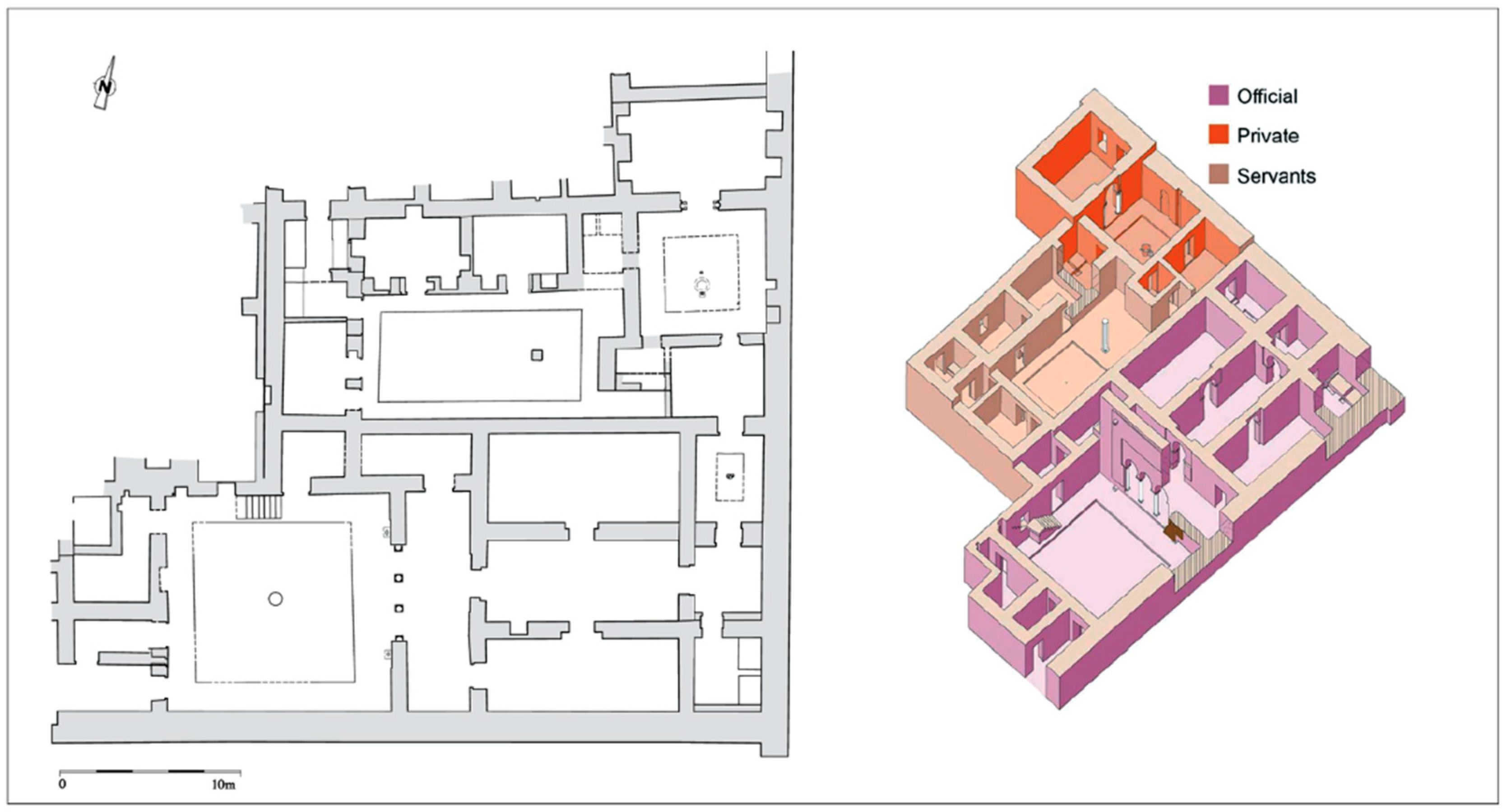

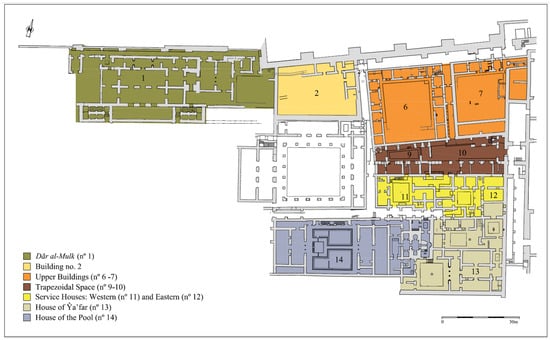

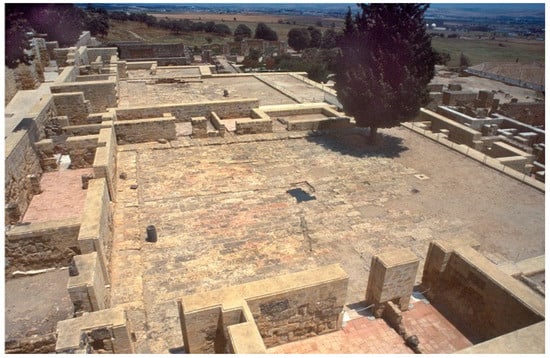

Apart from these large structures, the rest of the urban fabric, especially that situated in the area we could call “private” or with more restricted access, consisted of a heterogeneous complex that is more difficult to interpret (Figure 1).5 Excluding the building known as the Court of the Pillars (Patio de los Pilares), one of the most difficult for which to define a function,6 in the rest of that sector we find dwellings and spaces that in some cases we can identify as residential and in others as multipurpose, both residence and workplace.7 Some of these, such as the private residences of the caliph and the heir, as well as that of the ḥājib Jacfar ibn cAbd al-Raḥmān al-Ṣiqlābī, have been identified with more or less certainty, as we will see below, as have some of the spaces destined for what we can consider the running of the household or the provision of services to the palace (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Qaṣr of Madinat al-Zahra. Private and official sectors (Vallejo Triano 2016a, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Private sector. Own elaboration on the plan of Vallejo Triano (2016a, Figure 2).

It is difficult to identify the functions of these latter buildings for three main reasons. Firstly, because we do not know the number and organisation of the services destined to attend to the personal needs of the caliph and the heir and the palace administrative and maintenance tasks, which are only mentioned occasionally in the written sources.8 Secondly, because we do not know how the different departments that managed these services were structured, who ran them and how many staff they had. And thirdly, because behind the description “servant” there were various groups of workers with different designations, including ʽabīd, fityān, ġilmān, ḫuddām, etc. (Meouak 2004, pp. 221–30). Most of these were slaves who carried out diverse administrative and domestic functions and had different levels of personal proximity and access to the caliph, as well as to different areas of the palace. As it turns out, the perspective of analysis that we are going to use to identify those residences destined to the “service” or the “maintenance” will combine a syntactic approach to them (based on the type of rooms that compose them, the peculiar relationship between them, its building materials, especially the floors, etc.); and an analysis of its contextual relationship with the nearby dwellings and with the rest of Qaṣr. In addition, we will propose some hypotheses about other buildings with similar characteristics, intended for these same activities related to the maintenance.

The objective of this study is, therefore, to assemble and update the dispersed data on these edifices and offer an overview of the inhabitants of the Alcazar by analysing its architecture and associated materials9. Although we will present only a very limited number of buildings referring exclusively to that “private” zone of the Qaṣr, we will also attempt to show how those could be representative of the hierarchy and organisation of all its inhabitants. Not included in this consideration are the spaces destined exclusively for women, such as the harem, which has not yet been excavated.10

2. The Caliphal Residences

The two buildings we can identify as the residences of the caliph and the heir occupy a privileged position in the Qaṣr, especially the caliphal dwelling, which was built on the highest part of the urban site. Chronologically, both belong to the foundational phase and therefore their architectural programmes were effected without any preconditioning factors; in other words, their location was entirely intentional.

To these palaces we have to add a complex of rooms related to the Hall of cAbd al-Raḥmān III that has been identified as the al-majlis al-sharqī (Eastern Hall)11 and is known therefore as the “Rooms Adjoining” that Hall. They appear to have been used at different times as places of leisure and residence by both caliphs, especially al-Ḥakam II. Their construction—at the end of the 950s—was part of the major building reform programme that led to the laying out of the terrace occupied by the so-called Upper Garden and involved the demolition of some earlier structures (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 486–87). These rooms were organised in three parallel corridors that ran from east to west and included a bath for one person at the eastern end that had also been refurbished prior to 353 H/964–965 (Martínez Núñez 1999, pp. 85–86).

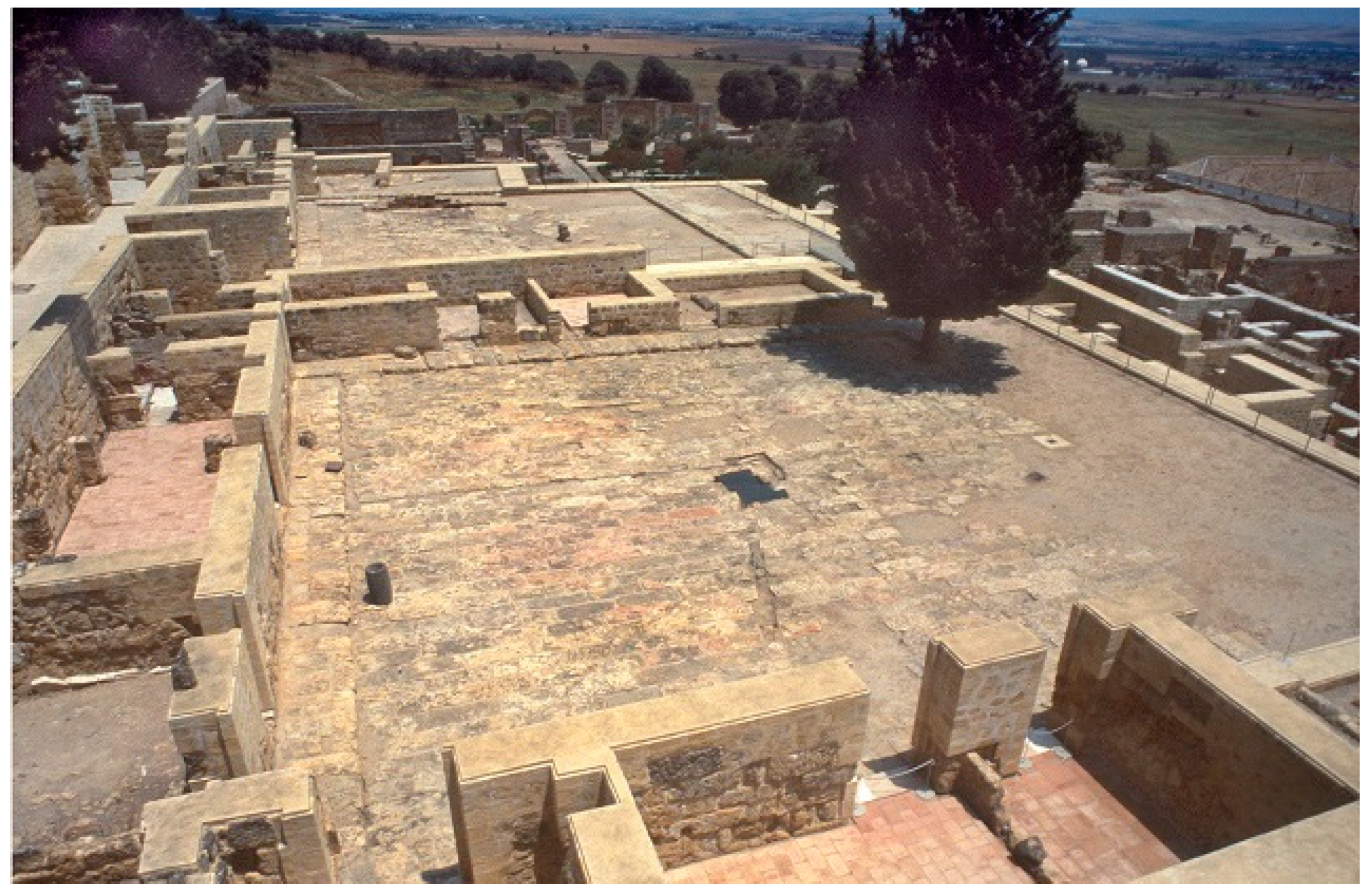

2.1. The Residence of cAbd al-Raḥmān III: Dār al-Mulk

Judging by its location on the highest part of the Qaṣr and the city and its designation of Dār al-Mulk Ibn (Ḥayyān 1967, p. 99), the intimate residence of the Caliph cAbd al-Raḥmān III represented “the public image of the power”12 (Meouak 1999, p. 38) (Figure 3). In that location it was the visual reference of the metropolis and the pinnacle of the political and social hierarchy. As such, the importance of the rest of the Qaṣr’s residents was shown by how close they were to it (Vallejo Triano 2010, p. 502). The complex was excavated in 1911 and was tentatively identified as the caliphal residence by Velázquez Bosco (1923, pp. 13–14). This was confirmed by subsequent research that dealt with singular aspects, including the importance and symbolism of the location, its opening to the exterior via a terrace-lookout point (something formerly unseen in palace residences), its role as the initial point for the construction of the Alcazar and the characteristics of its ornamental programme (Hernández Giménez 1985, pp. 44–46, 72–75; Manzano Martos 1995, pp. 328–29; Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 460, 467, 501).

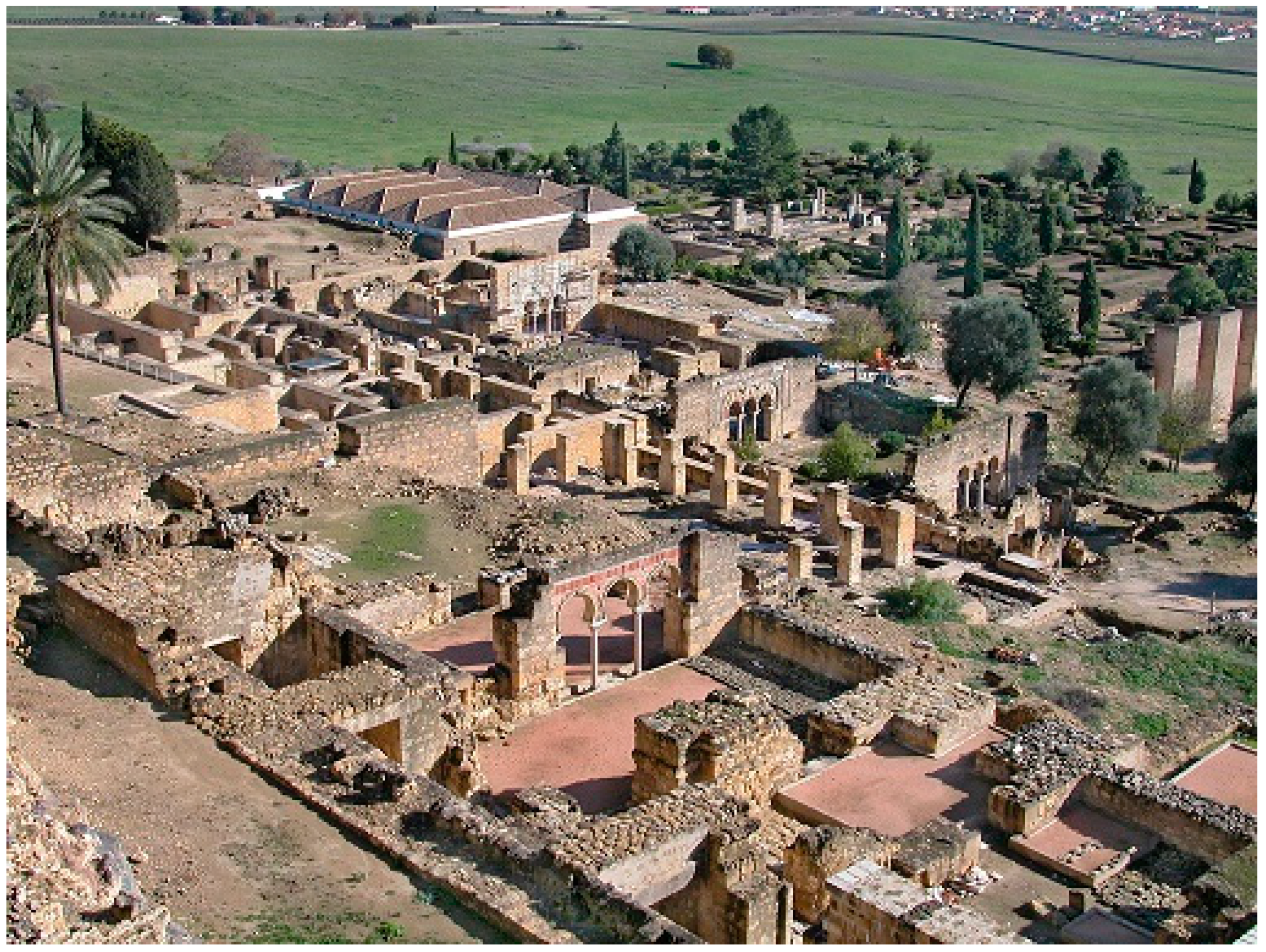

Figure 3.

Qaṣr view with the Dār al-Mulk as a visual reference in the foreground. (Photo M. Pijuán © Conjunto Arqueológico de Madinat al-Zahra).

The caliph conceived his palace as a private space, but it also transmitted the image of an official and representational building. This functional duality can be deduced from the architectural structure of the residence itself (the absence of courtyards, an exterior-facing façade, etc.), as well as the presence of epigraphic friezes in which the caliph presents himself with ceremonial titles, such as Imām and the laqab al-Nāṣir, which appear for first time in the monumental epigraphy of Madīnat al-Zahrā’ in the Hall of cAbd al-Raḥmān III. Given that this residence would have been the first building in the Qaṣr and the city,13 these friezes must date to some work on the refurbishment of this edifice in around 345 H/956–957 (Martínez Núñez and Acién Almansa 2004, pp. 119–23).

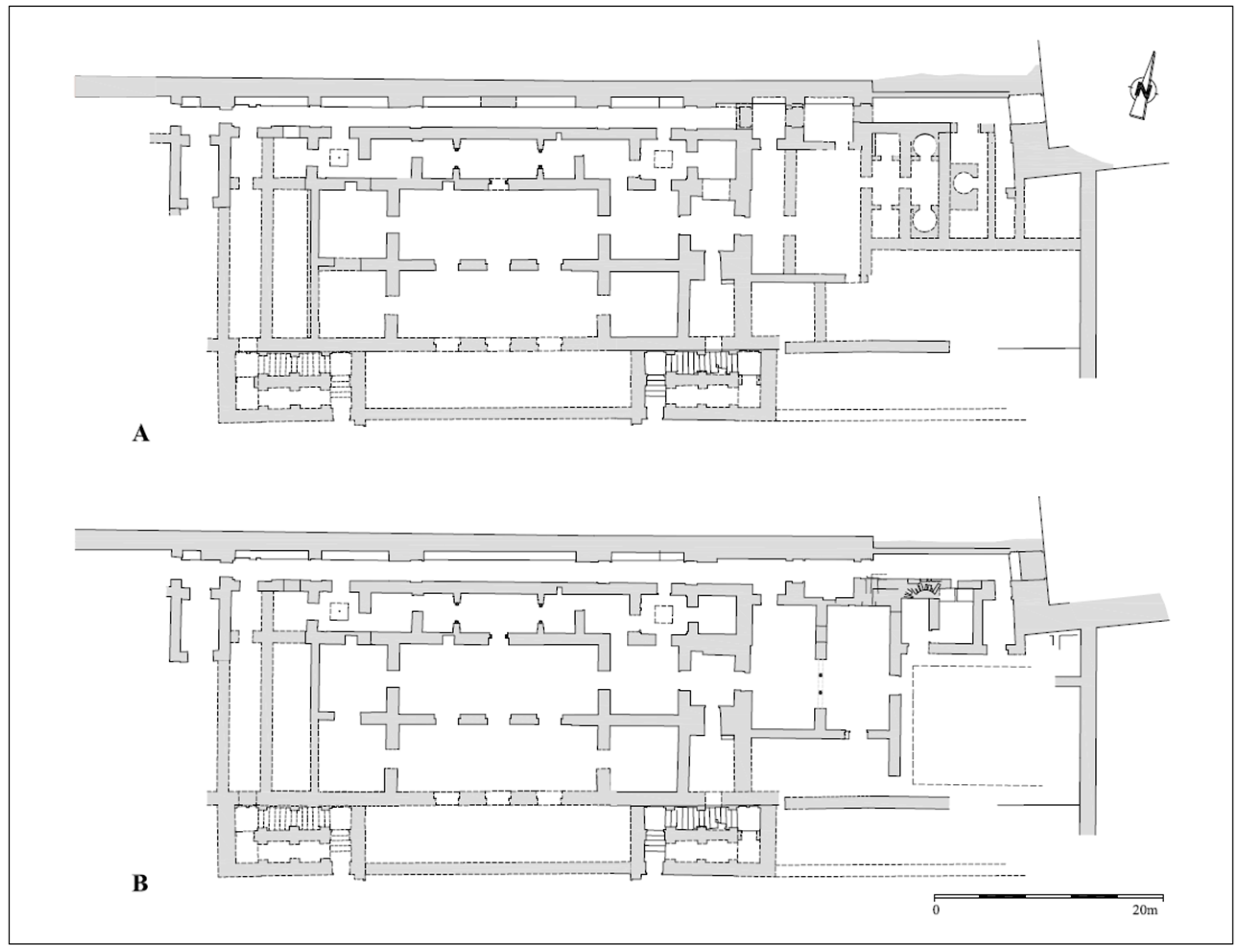

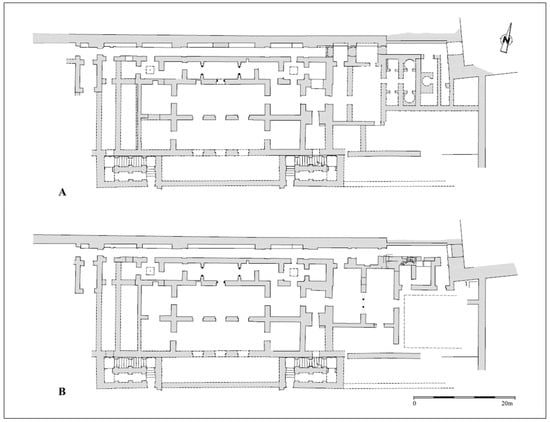

The dwelling was separated from the walls by a corridor that was probably used by the service staff to move about in. Its central architectural structure is organised around three long parallel rows of rooms along a corridor running from east to west and ending in chambers that, in the case of the northern one, opens onto other rooms and ventilation courtyards (Figure 4A).14 Of these corridors with rooms, it has been suggested that the northern one, which is narrower, would have been conceived as a suitable living and sleeping area. The next would have constituted the main hall and meeting room (majlis). Finally, that situated more to the south would have functioned as a portico with respect to the one behind it and would hypothetically have opened onto a terrace-lookout point over the city and the territory, of which nothing remains today (Almagro 2007, pp. 33–35; Vallejo Triano 2010, p. 467). The difference in height from the edifices of the lower level was overcome by the construction of two large staircases, of which we have the remains of one organised around a central rectangular buttress.15

Figure 4.

Construction phases of Dār al-Mulk: (A) first phase; (B) second phase (Vallejo Triano 2010, Figure 53-1).

On the eastern side of this block of rooms there was a single-person bath (Figure 4A). Its existence and layout have been demonstrated by the stratigraphic analysis of its paraments, given that it was demolished during subsequent rebuilding that resulted in two north–south-oriented rooms separated by a tripartite arcade and other small rooms that opened up onto a courtyard (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 466–67).

In addition to the bath, there are two more elements that highlight the singularity of this residence in the group of residences in the Qaṣr: their floors and the decorative programme on their walls. The floors in the two main rooms of the central block are exceptional in caliphal architecture, as they combine large clay tiles with pieces of white stone laid as a perimetric border around the central field, which is occupied by plain tiles (Figure 5). In other cases, it is the clay tiles themselves that have incrustations of white limestone that generate a rich, geometric-type ornamental repertory among which at least 12 different motifs can be recognised.16 Although this type of flooring has no precedent in the architecture of al-Andalus, we can point out as a decorative antecedent the clay slabs with limestone incrustations that decorate the tympanums of the sābāṭ door built by the emir cAbd Allāh in the Córdoba mosque, which also present diverse geometric compositions.17

Figure 5.

Floor in Dār al-Mulk. (Photo A. Vallejo © Conjunto Arqueológico de Madinat al-Zahra).

The decorative programme in stone with plant, geometric and epigraphic motifs is also singular. It is focused on the tripartite apertures in the main rooms and on the interior door of the northern room (Figure 6). The former, which are lintelled apertures, were extradosed with decorative horseshoe arches, a solution normally reserved for the main gates of cities and official fortresses,18 as well as the Córdoba mosque. Their presence endows this building with a particular symbolism as, in both the emirate and the caliphate, the horseshoe arch—decorative or real—became an “honorific, emblematic and representational” element that “necessarily formed part of the visual lexicon associated with the State” (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 395–96, Figure 46). The acanthus and the palmette were the most common choices for decorative plant motifs; the latter, which had special significance for the Umayyad dynasty, underwent multiple morphological developments from that time on.19

Figure 6.

Dār al-Mulk. Decoration of the interior doors. (Photo M. Pijuán © Conjunto Arqueológico de Madinat al-Zahra).

As we have already pointed out, this residence underwent various transformations (Figure 4B). One of them, in 972, was used to adapt it as a residence and study for the heir Hishām Ibn (Ḥayyān 1967, pp. 99, 225). We can relate this latter refurbishment to the demolition of the bath, the transformation of that space into new rooms and the opening of a door in the faṣīl al-fityān (servants’ corridor), which we identify as the corridor situated between the block of rooms and the wall. The decision to install Prince Hishām in the residence of his grandfather, cAbd al-Raḥmān, the founder of the caliphate, was charged with enormous symbolism and can be linked to the series of “propaganda” measures taken by al-Ḥakam II to ensure Hishām’s recognition as the heir and future caliph, given that he was still a minor (García Sanjuán 2008, pp. 50–59; Vallejo Triano 2016a, p. 440).

2.2. The Heir: The House of the Pool

One of the most significant peculiarities of the Umayyad caliphate was the importance given to the heir and, in particular, to al-Ḥakam. Among the aspects indicated by historiography, of particular note is his early designation as heir; his taking on of important governmental tasks, such as the finances or control of the administrative machinery of the state, on the orders of his father; his supervision of the caliphate’s propaganda and building programme, beginning with the construction of Madīnat al-Zahrā’; the vast scope of his education and interest in knowledge; and his fundamental role in the cultural development of al-Andalus.20 To these arguments we have to add that he had his own political reception room opposite that of the caliph.21

The sources do not make any explicit reference to Prince al-Ḥakam’s residence, although, based on diverse archaeological and contextual arguments, it has been identified as the House of the Pool (Vallejo Triano 2016a, pp. 437–40).22 In addition to weighing up its architectural, typological and ornamental qualities, which cannot be compared to any of the other residences excavated, a fundamental factor is its proximity to that of the ḥājib Jacfar ibn cAbd al-Raḥmān, who is mentioned by Ibn Ḥayyān (1967, p. 88) in relation to the transfer of the Slavic fatà, Fāiq ibn al-Ḥakam, to that house in 971, following Jacfar’s death.23 The identification of both these dwellings is, therefore, mutually reinforced.

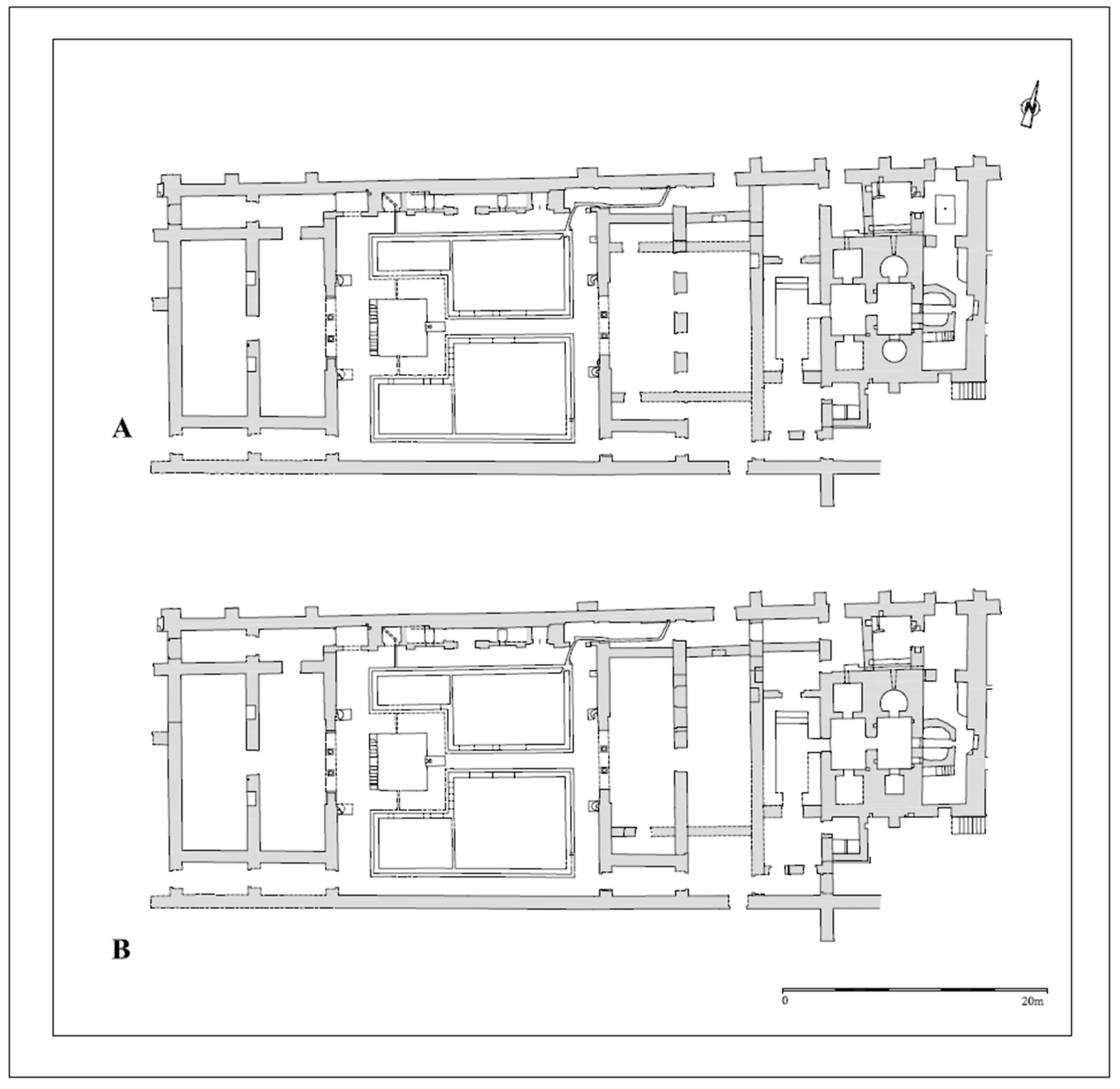

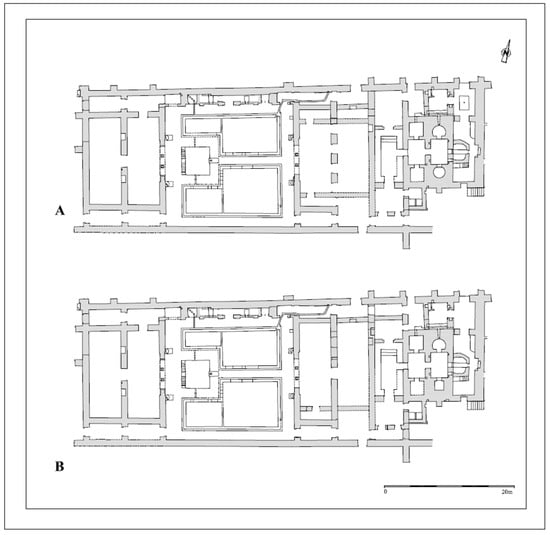

This palace presents a very original structure, as it includes various innovations that mark a substantial departure from the architecture of al-Andalus until then (Figure 7A). The first relates to the introduction of an interior courtyard-garden with stone-paved walkways that delimit two symmetrical flowerbeds—although of unequal size—and a small pool at its eastern end. In the middle of the northern side of the courtyard is the main entrance via a double-sided staircase whose façade fulfilled an important ornamental function, as it was arranged through five openings covered by a horseshoe arch, two foliated arches and two lintels (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 279, 479–80). The residence had other side entrances in the form of corridors: one on the northern side for the serving staff who lived in the so-called Service Houses and two more symmetrical entrances on the southern side, one for entering the bath and the other to connect with the western part of the palace.

Figure 7.

Construction phases of House of the Pool: (A) first phase; (B) second phase (Vallejo Triano 2010, Figure 53-2).

The second innovation consisted of the arrangement of opposing double rooms on the short sides of the courtyard. The first of these rooms acts as a room-portico, as it opens onto the courtyard through arcades of three horseshoe arches supported by two central columns and the wall itself at each end. These arcades were closed by two large leaves of external doors. This is the first time the structure of a courtyard with a double portico is seen in al-Andalus, although its oriental precedents, albeit not sufficiently clarified, can be found in Abbasid architecture, specifically in Ujaydir (Manzano Martos 1995, pp. 324–26; Orihuela Uzal 1996, pp. 19–21).

Although these double and parallel rooms seem similar, we note substantial differences between those located west and east of the courtyard. The first ones do not present barely constructive modifications, but the second ones (eastern) underwent various reforms in the configuration of the apertures in the separating wall, which suggests the hypothetical existence of end bedrooms in their initial configuration (Figure 7).24 These changes indicate that there was no exact correspondence between these sets of rooms, so they cannot be explained by different seasonal uses, for example, summer and winter rooms.25 We can, therefore, propose a hypothetical residential use for the western rooms, which had the best orientation and were the most important, given the position of the pool and the fountain facing them, and that the eastern rooms were used for meetings—majlis—(Vallejo Triano 2010, p. 468). Thus, the house was laid out with different areas designed to meet the day-to-day needs of the heir and also for meetings and representation.

Another innovative feature in relation to the preceding architecture is the introduction of tripartite arcades on the interior façades. As far as we know today, their appearance in al-Andalus is documented for the first time on these façades, which we can place chronologically several years before the presence of tripartite apertures in the windows of the minaret built by cAbd al-Raḥmān III in the Córdoba mosque.26

The singularity of this residence is also evidenced by its ornamental programme in stone, which is mainly concentrated on the aforementioned façades (Figure 8). The decoration associated with the arches uses different geometric and plant motifs, among which we can highlight, once again, the acanthus and the palmette. The latter is also used as a principal motif on the panels placed on the jambs and the end supports of the arcades, the decoration of which was organised by means of a geometric tracery. Like the applied decoration, the capitals reveal archaising features that correspond to the first construction phase at Madīnat al-Zahrā’ (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 432–33, 369).

Figure 8.

House of the Pool. Courtyard-garden and interior façades. (Photo M. Pijuán © Conjunto Arqueológico de Madinat al-Zahra).

The organisational model of this residence, with double opposing porticos and a courtyard with a pool and a garden, albeit with a greater or lesser development of those elements, had enormous repercussions for the subsequent architecture of al-Andalus, both domestic and, especially, palatial (Jiménez Martín 1987, pp. 89–91; Orihuela Uzal 1996, p. 21).

Like the Dār al-Mulk, the residence had a bath at its eastern end (Figure 7). This bath corresponds to the first building phase, as we were able to demonstrate from the archaeological excavation carried out on them and on the wall that separates the residence from the bath dressing room (Vallejo and Montilla Unpublished). Its rooms were arranged in parallel corridors in which we identify the dressing room, characterised by marble benches around the perimeter, and the warm and hot rooms, the latter consisting of elongated rooms ending in small square or ultra-semicircular rooms. The boiler was installed outside the hot room and a room that, judging by its special characteristics, with interior niches in its walls and two floors, we can identify as being for the servants charged with operating and maintaining the bath. This has the same layout of warm and hot rooms as those in the Rooms Adjoining the Hall of cAbd al-Raḥmān III, although the architectural programme of the latter is more extensive and complex as it has more rooms.27 Both appear to have been based, with minor differences, on the Umayyad baths of the East.

In the final years of cAbd al-Raḥmān III’s life, the residence underwent major renovations as part of the aforementioned grand urban reform of the Qaṣr. These involved the installation, at least in the eastern rooms, of a new floor of marble slabs laid over the earlier mortar floor painted in red ochre, as confirmed by the excavation. This “monumentalisation” of the residence also affected the bath. The small semicircular room of the caldarium containing the pool was replaced by a quadrangular one, at the same time as an exceptional marble decorative programme was introduced (Figure 7B).28 This ornamentation has been preserved on the marble jambs of the entrance to the pool and three small openwork arches, also of marble, with inscriptions that document this reform in the year 350 H/961, very soon after the death of the caliph al-Nāṣir in that same year (Ocaña Jiménez 1976, pp. 219–20).

3. High-Ranking State Functionaries: The House of Jacfar ibn cAbd Al-Raḥmān Al-Ṣiqlābī

One of the features that characterised the Umayyad caliphate was the progressive importance attained by a new type of state functionary of ṣaqāliba (sing. ṣiqlābī: slave) origin that exercised real and effective power, sometimes to the detriment of the long-standing Arab-Berber aristocracy whose families had monopolised the most important posts in the Umayyad administration since the time of the emirate.29 These ṣaqāliba became a very influential group in the palace, both in the administrative sphere, where they occupied important posts, and the strictly private domain at the service of the sovereign, always from a position of absolute loyalty to the Umayyads (Meouak 2004, pp. 237–38). Once they had been freed from bondage, they took on a fictitious filiation in their names as “sons” of their former owners.

In the administrative sphere, the most representative figure in this group was the eunuch Jacfar ibn cAbd al-Raḥmān al-Ṣiqlābī, fatà and mawlà of the first Umayyad caliph (Meouak 2004, pp. 180–82). His name reveals the “fictitious son” relationship with his former owner, the first Umayyad caliph, and his slave origin. Thanks to the epigraphy, we have an overall idea of his cursus honorum. Under cAbd al-Raḥmān III, he held the posts of head of the stables (sāḥib al-ḫayl) and of the tiraz (sāḥib al-ṭirāz). His big promotion came under al-Ḥakam II, who named him ḥājib, the highest political dignity of the caliphate, in 961, a post that he retained until his death in 971. During that last decade, he is also mentioned intermittently as kātib or secretary and given the honorific title of sayf al-dawla or “sword of the dynasty” (Ocaña Jiménez 1976, pp. 220–21; Martínez Núñez 1999, pp. 84–85; Martínez Núñez 2015, p. 45).

His importance in the administration is reflected significantly in his residence in the al-Zahrā’ Qaṣr, both in urbanistic and architectural terms. The identification of the building adjoining the Residence of the Pool with the Dār al- ḥājib Jacfar of the written sources (Ibn Ḥayyān 1967, p. 88; Labarta and Barceló 1987, p. 99) appears to be beyond doubt. It was pointed out by Hernández Giménez (1985, pp. 67–69, 71) and corroborated with new arguments by A. Vallejo (Vallejo Triano 1990, pp. 133–34; Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 490, 500).

Everything indicates that this palace, in which he lived and undertook the administrative duties he was in charge of, was built in the first years of the al-Ḥakam II government, which is in keeping with the date of his rise to ḥājibato. The archaeological excavations have demonstrated that its unusual asymmetric organisation is the result of its adaptation to the space formerly occupied by three earlier residences that had been demolished, with part of the materials—particularly some of the paving slabs—being reused in the new dwelling (Vallejo Triano et al. 2004, pp. 202–5).

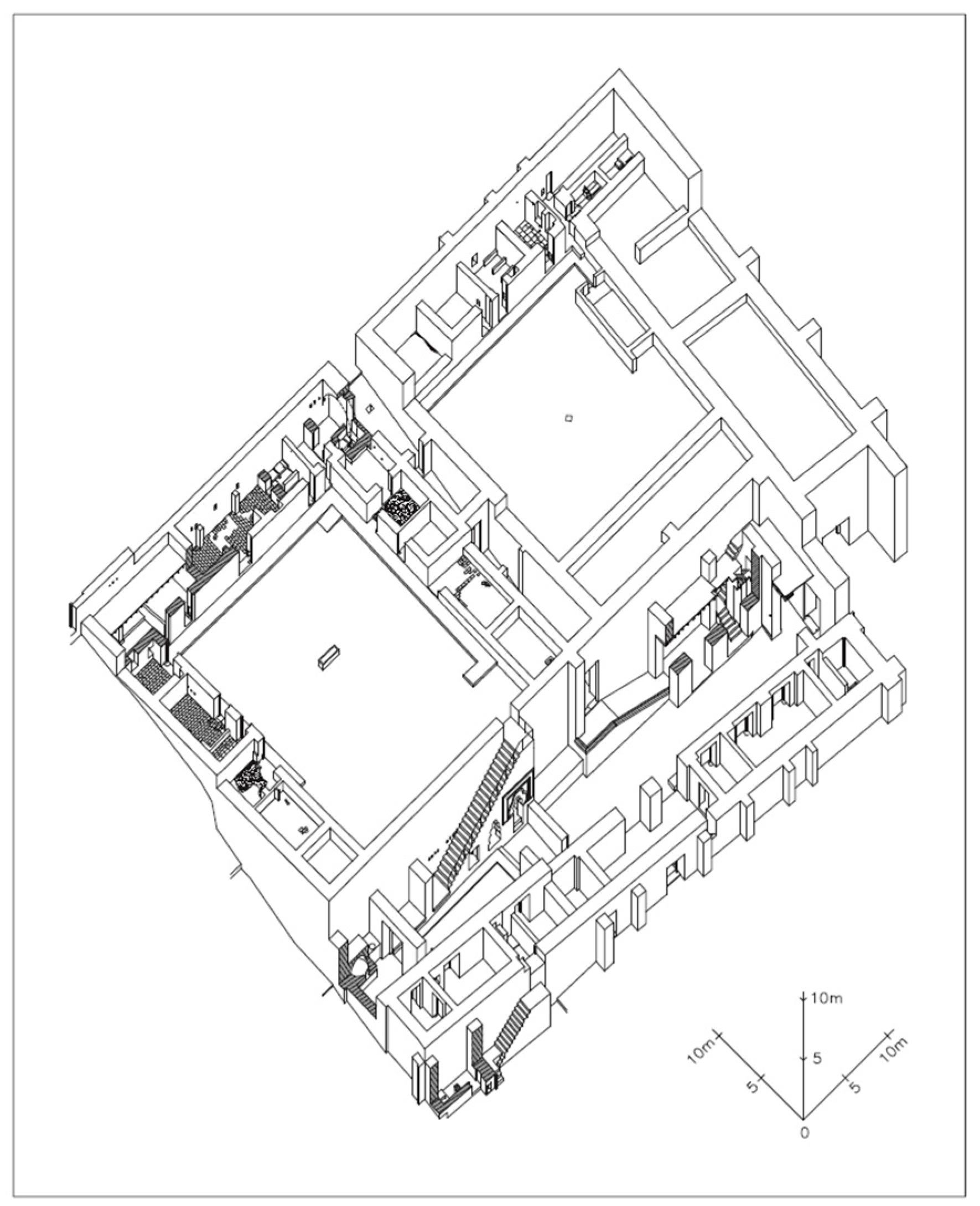

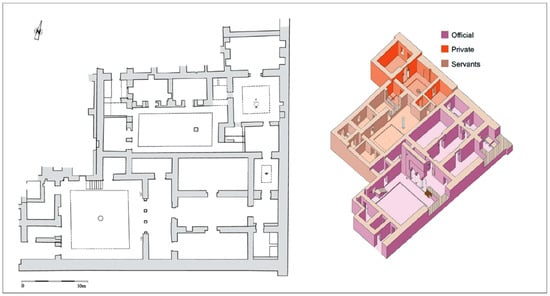

This building stands out for its multifunctional architectural structure with three different areas organised around courtyards, each with a specific function: work, rest and service (Figure 9). The first is directly related to the administrative activity and, therefore, received greater attention in all its aspects. It was configured as a hall composed of three intercommunicating longitudinal naves (running from east to west) and a transversal frontal nave opening onto the courtyard entrance to the residence via a richly decorated tripartite arcade (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

House of Jacfar. Plan (Vallejo Triano 2010, Figure 44).

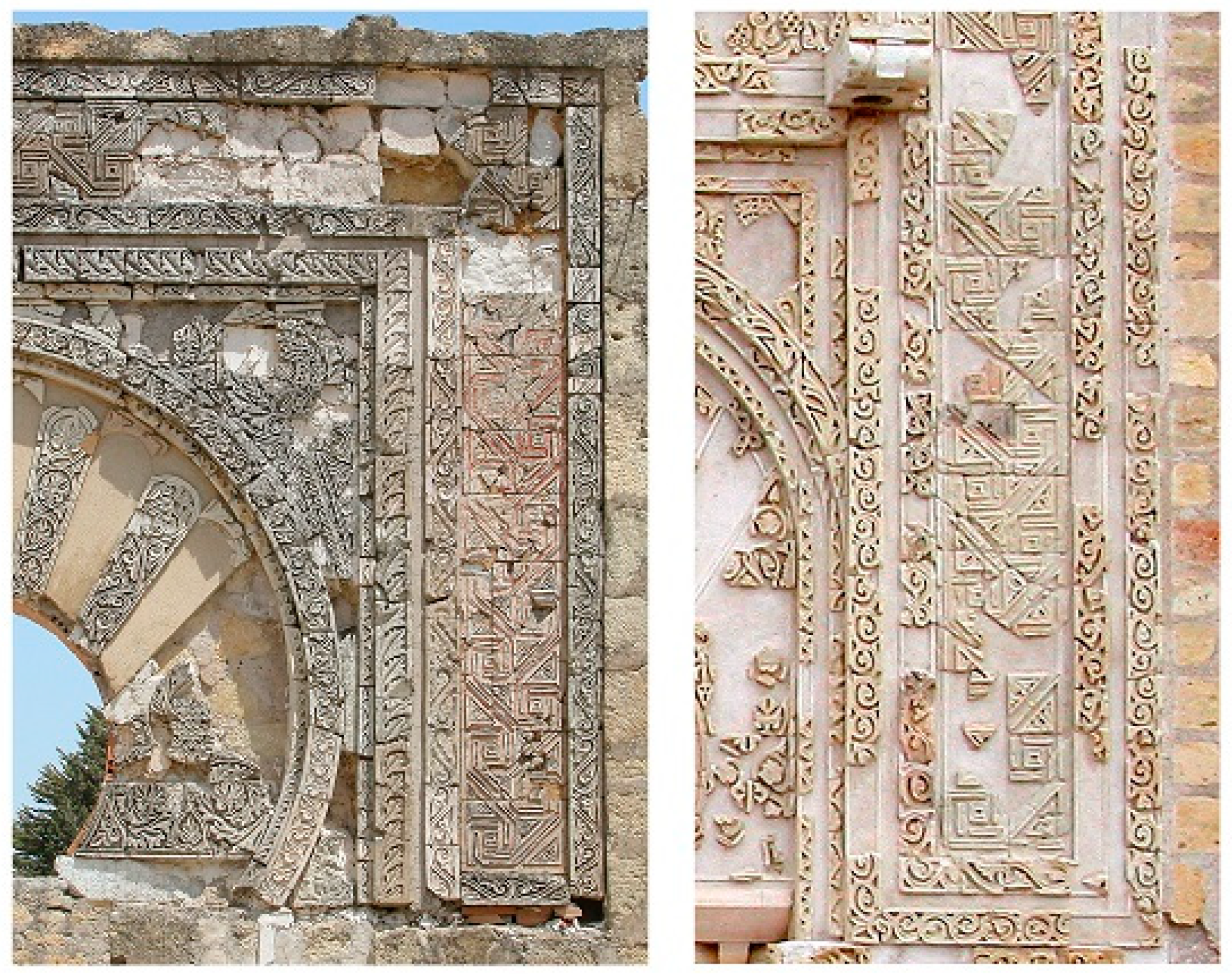

Figure 10.

House of Jacfar. Façade (Photo M. Pijuán © Conjunto Arqueológico de Madinat al-Zahra).

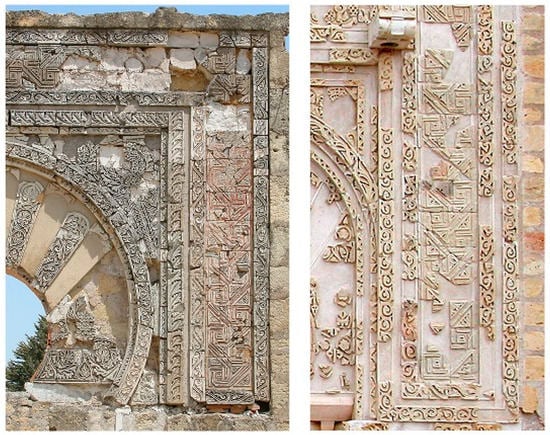

This façade had the highest concentration of applied architectural decoration in the residence.30 It contained a combination of innovative elements, already seen in the Hall of cAbd al-Raḥmān III, and others with a direct link to those observed in Dār al-Mulk and, particularly, in the House of the Pool (Figure 11). Among the latter, of particular note is, on the one hand, the resorting to plant motifs such as the palmette and the acanthus, which are displayed in very similar decorative schemes to others in the Residence of the Pool; and on the other, their use as the main element and in certain precise locations: the interior spaces of the jambs at the entrance to the building and the entrance jambs to the central nave. The choice of these elements and compositions in those specific placements—especially the palmette—has been interpreted as evidence of their personal link to the service of the Umayyad dynasty, in this case, the caliph al-Ḥakam II.31 The same is true of the geometric decoration on the façade that copies, with slight modifications, that found in the prince’s residence. The tripartite arcade model is also based on the façades of Prince al-Ḥakam’s house, although it introduces as a novelty in residential architecture the end arches supported by columns and not the walls.

Figure 11.

House of the Pool (left) and House of Jacfar (right). Frames with geometric decoration. (© Conjunto Arqueológico de Madinat al-Zahra).

The second area of this palace, which is connected to the first via small courtyards and rooms, was the actual residential and living area (Figure 12). The courtyard that precedes the bedroom stands out for its circular marble fountain with a spout on its axis. This bedroom was separated from an architectural complex situated to the north; it is a large room with four spacious interior niches in its walls. Its importance is demonstrated by its entrance, which is covered with a horseshoe arch supported by capitals, columns and bases, although none of these elements has been preserved (Hernández Giménez 1985, p. 68).32 Linked to the bedroom there is a latrine situated on its western side and accessed via the courtyard.

Figure 12.

House of Jacfar. Private and service areas (Photo M. Pijuán © Conjunto Arqueológico de Madinat al-Zahra).

The third area of the residence was for the servants who attended to the needs of the main resident, as their rooms also communicated with what we designate the Eastern Service House, where the kitchen is located. This space was adapted from some already existing rooms with a similar function that were refurbished and connected to the living space of the residence (Figure 12).33 The complex is organised around a courtyard with rooms on its northern and western sides, the former with niches and a gallery supported by an octagonal-shaped pillar on the eastern side. Although it lacks prestige architectural elements, such as the horseshoe arch, the applied decoration and the marble paving, the floors of the rooms suggest that its residents had a certain status, as they were made of alabaster slabs in some cases and mortar painted in red ochre in others, which denotes a certain hierarchy and specialisation.

In conclusion, the singular architectural structure of the house, the quality of its building materials—especially the extensive use of marble in the floor—and its important ornamental program come to demonstrate that this residence does not correspond to a family unit but a person who lives alone and who occupies a high position in the administrative structure of the Umayyad state (Vallejo Triano 1990, p. 134; Vallejo Triano 2010, p. 490).

4. The Overseers of the Palace and the Servants

In addition to the caliphal residences and those of the state administrative elite, represented in this study by the figure of the ḥājib, the Qaṣr contains other buildings that appear to be related to the multiplicity of day-to-day functions and activities involving, on the one hand, the people at the service of those personages and, on the other, the functioning of the complex care and maintenance machinery of the Alcazar.

In a similar way to the administrative organisation, this machinery would have been structured by way of a complex number of posts whose occupants would have appeared under the denomination of ṣāḥib (pl. aṣhāb),34 although we know little about them.35 These posts were also occupied by multiple fityān (sing. fatà) of ṣaqāliba origin who had their own hierarchy, as some are mentioned as al-fityān al-akābir (grand servants) and were under the responsibility of a ṣāḥib al-fityān (chief of servants) (Meouak 2004, p. 227). Under their command there was an endless number of servants, a large part of whom would have been slaves, according to the sources36. Archaeology is unable to establish the gender of these servants; therefore, we do not know whether certain activities were carried out exclusively by men or by women or both.

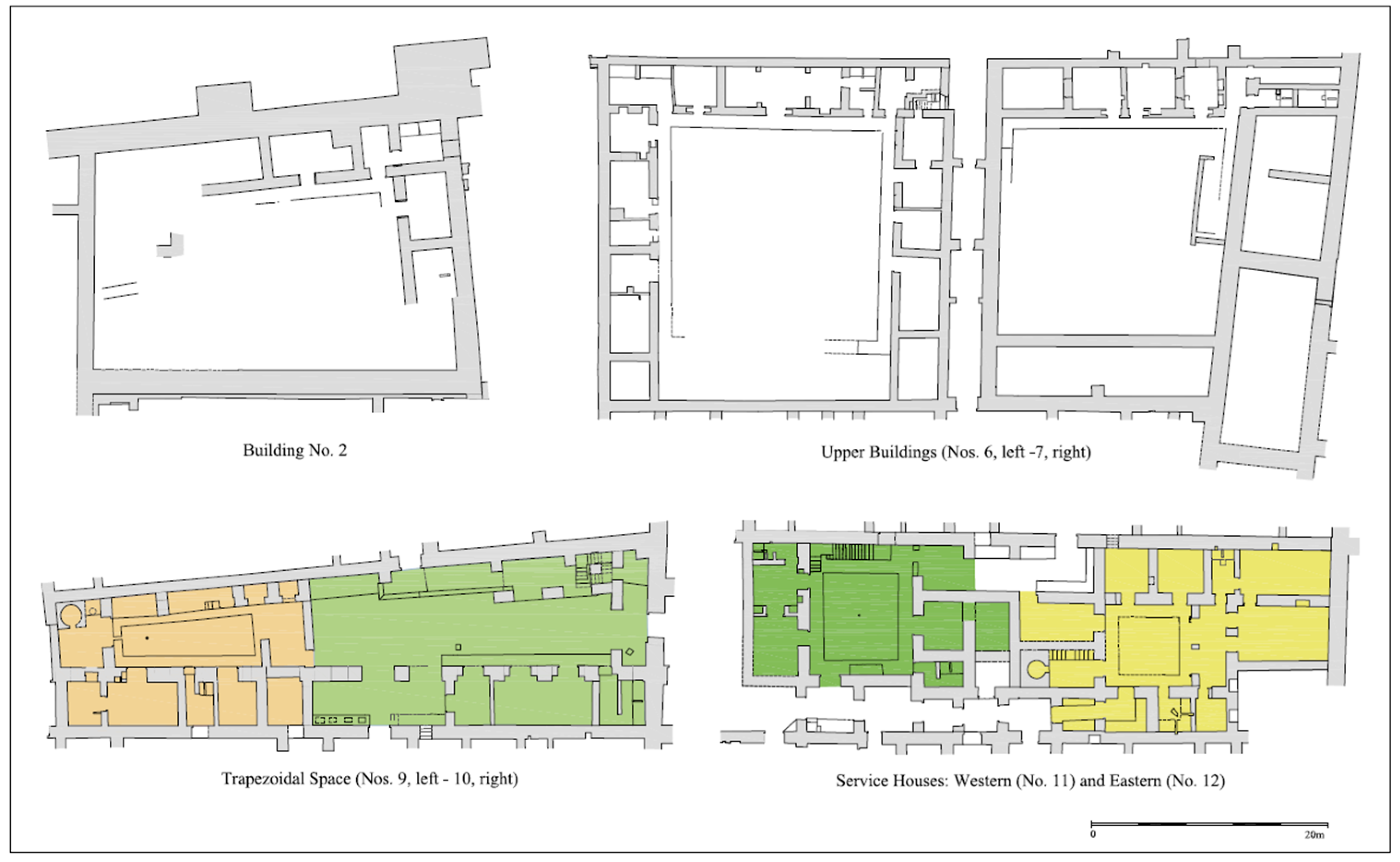

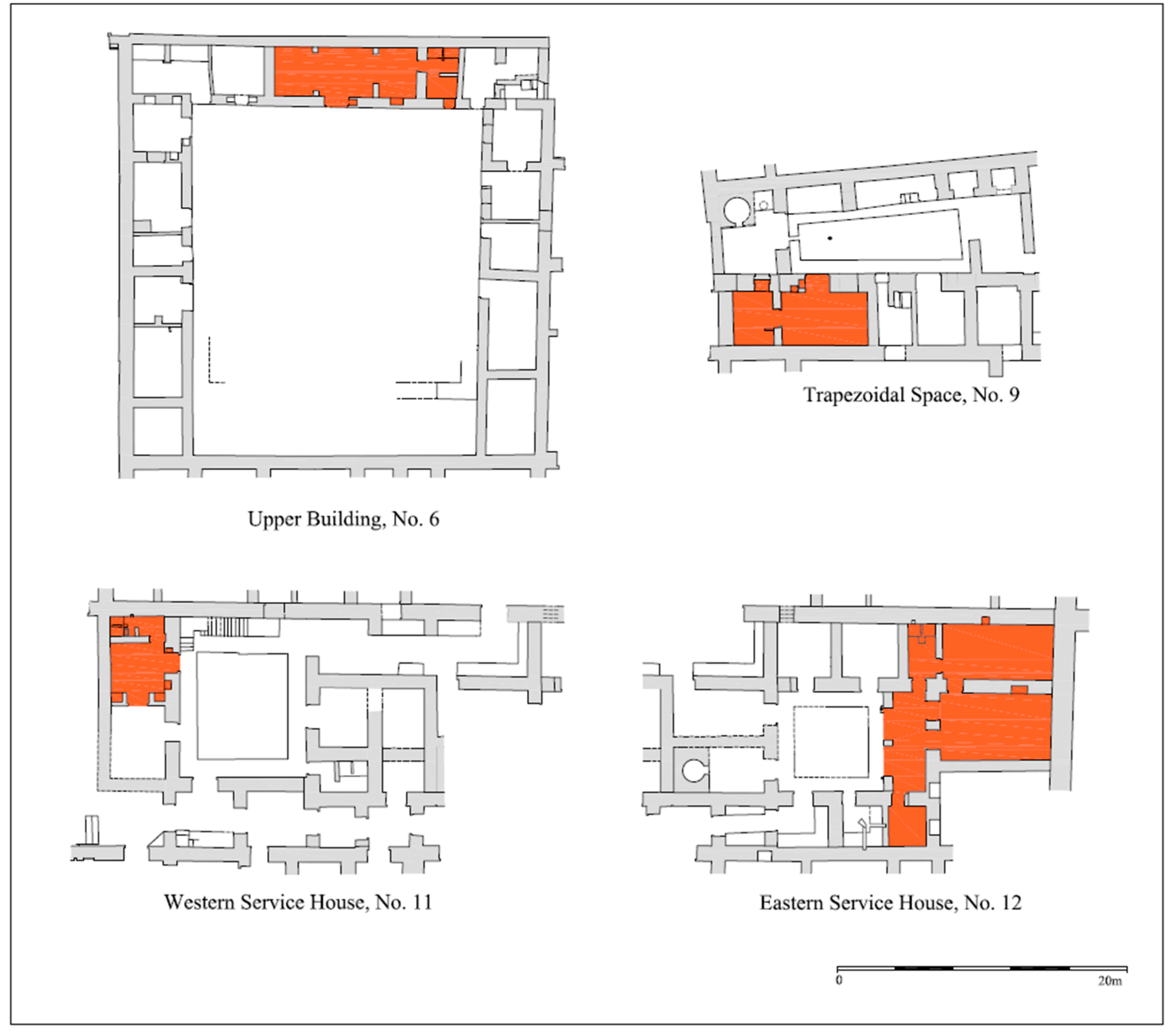

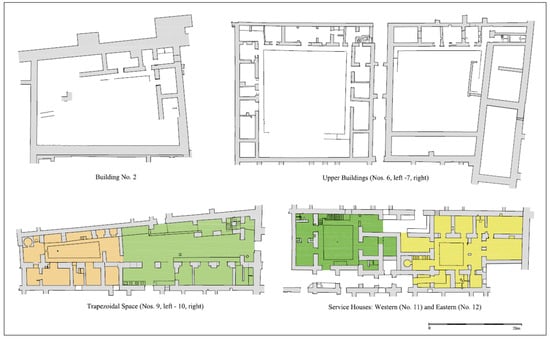

There are several dwellings that, due to their structure, materials and location—in many cases adjoining some of the grand palaces we have previously analysed—have been identified as seats of these palace department headquarters and, at the same time, as servants’ working spaces (Vallejo Triano 1990, p. 131) (Figure 13). There are basically two architectural and spatial markers that denote these headquarters. The first is the distribution of the rooms and their materials that allow us to differentiate between the residential area of the person in charge of the activity and that of those who carry it out. Thus, although these are organised around a courtyard, their architectural layout does not correspond to the typical structure of a residence designed for a family unit, where there is no clear hierarchy of rooms other than that of a functional specialisation (Gutiérrez Lloret 2015, pp. 25, 29–30). Another indicator is the association of the bedroom with a latrine for the specific use of the head person, even though there are other latrines open to the courtyard for the rest of the workers and/or occupants of the residence. This bedroom–latrine combination is always linked to important personages. Through these two indicators we can see relationships of dominance, dependence or subordination of some rooms with respect to others (Figure 14).

Figure 13.

Buildings for the Qaṣr overseers and servants. Own elaboration on the plan of Vallejo Triano (2016a, Figure 2).

Figure 14.

Hierarchical structure inside the residences (Nos. 6, 9, 11, and 12). Own elaboration on the plan of Vallejo Triano (2010, Figures 9 and 56).

On the other hand, these buildings were designed to fulfil specific functions and reflect a clear specialisation with respect to the rest of the structures that make up the Qaṣr. This also appears to be shown by the archaeological excavation of the drainage channels37 that run below the main residences, insofar as there is a notable absence of cookware and bone fragments from food preparation. This is in strong contrast to the abundance of such items found below the service buildings. This disparity has been interpreted as being due to the fact that dishes and food remains were removed from the prestige residences and taken back to the preparation areas (Vallejo Triano 2010, p. 158).

There are various dwellings that we can link to carrying out different domestic or maintenance tasks and that were also the residences of those in charge of supervising them.

The best known of these are the so-called “Service Houses” (Nos. 11 and 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14). This is a complex made up of two residential and work units, the Eastern (No. 12) and the Western (No. 11), which share a generic service function, but have important differences. Of particular note is their location in the middle of the “private” zone of the Alcazar and their link to the Residence of the Pool and the House of Jacfar, which they would have served and with which they are communicated via an alley flanked by stone benches that allowed the servants to enter from the side rather than the main entrances (Vallejo Triano 2010, p. 132).

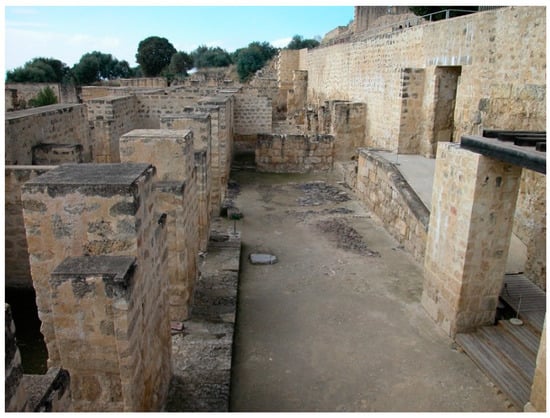

The type of task carried out in the Eastern House (No. 12) can be determined architecturally from the presence of a brick cooking oven, evidence that it was used to prepare food for the eminent occupants of the adjoining residences (Figure 15).38 This residence is the part of the Qaṣr, where we can definitively identify one of the aforementioned palace headquarters, specifically the seat of a ṣāḥib al-maṭbaḥ or head of the kitchen (Vallejo Triano, 1990, p. 131).39 There are several features that support this statement. At the eastern end of the residence, there are two elongated rooms perpendicular to the courtyard. They are communicating and open onto the courtyard through a transversal portico-room supported by a central pillar. This type of perpendicular room with a front portico is reminiscent of a model associated with a clear representational activity and endows a special status on its occupant. One of these rooms fulfils the function of a bedroom and contains a latrine with a marble floor and running water.40 The complex was isolated from the rest of the residence by a system of external doors supported by marble pole sockets and pivot poles, some of which have been preserved, which makes it a differentiated and autonomous residential unit within the dwelling.

Figure 15.

Eastern Service House, No. 12 (© Conjunto Arqueológico de Madinat al-Zahra).

In the rest, in addition to the oven, we can identify storage and/or work rooms and, above all, a very different latrine to the previous one because it is double—the only one of its type in the Qaṣr—and because it has no running water (Figure 16). It is precisely this element that shows us we are looking at a space frequented by a large number of servants of the same sex.

Figure 16.

Eastern Service House, No. 12. Double latrine. (Photo M. Pijuán © Conjunto Arqueológico de Madinat al-Zahra).

The presence of the perpendicular rooms with a transversal nave, the marked qualification that supposes the bedroom–latrine combination, along with such elements as the external aperture closure system—a prerogative of the Qaṣr’s most important buildings—highlight the hierarchic and social division established in the house, where we can clearly distinguish the residence of the ṣāḥib from the areas allotted to the other servants under his supervision (Figure 14) (Vallejo Triano 1990, p. 131).

In the Western House (No. 11, Figure 13 and Figure 14), the absence of any unique architectural element, such as an oven, makes it difficult to determine its exact function; it has been hypothetically associated with the serving of drinks at the table, given the large amount of glass found in the drainage channels that ran below it (Vallejo Triano 2010, p. 476). In this dwelling, what we consider to be the area of the “head of a palace department” adopts another morphology, as it is the bedroom–latrine combination of the western corridor that suggests it was the residence of the functionary in charge of supervising the work of multiple palace servants. The latter used a communal latrine in its southeastern corner.

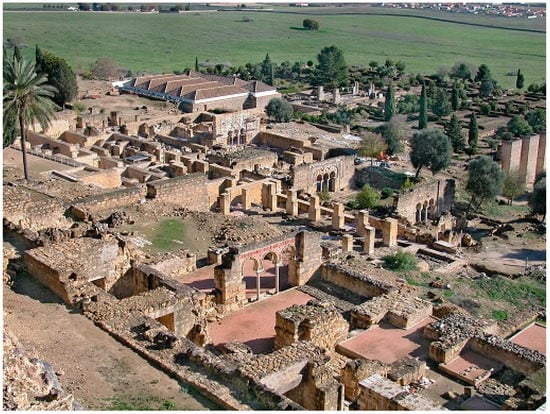

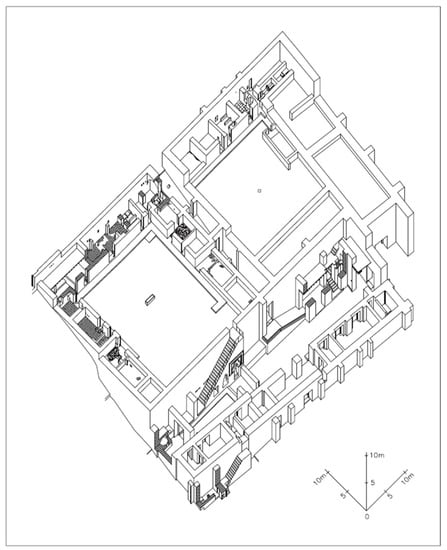

To the north of these two residences, the area known as the Trapezoidal Space (Nos. 9 and 10, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 17 and Figure 18) should be considered as another service sector that has traditionally been identified as the quarters of a small guard corps (Castejón y Martínez de Arizala 1945, pp. 37–40). It was originally a paved surface flanked by pillars that led directly to the buildings at the foot of the Dār al-Mulk. It was only when the major reform of the Qaṣr was carried out that the road was taken out of use and divided into two parts (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 144, 154, 267, 475). That situated to the east (No. 10) opens onto a courtyard and consists of two rooms, one of them large with an earthenware floor that would have been the accommodation for the guards who controlled the routes between the “private” and “official” zones of the Alcazar and, therefore, access to the important residences located to the south. Thus, it was a space occupied by servants and had a single latrine for shared use open to the courtyard.41

Figure 17.

Trapezoidal Space: Buildings Nos. 10 and 9 (© Conjunto Arqueológico de Madinat al-Zahra).

Figure 18.

Buildings Nos. 6, 7, 9 and 10. Axonometry (Vallejo Triano 2010, p. 282, pl. 226).

The adjoining residence (No. 9, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 18) opens onto the previous space and has two singular elements: a brick cooking oven and a staircase connecting to the Upper Western Building (No. 6) with a unique decoration.42 Although it underwent various transformations, as evidenced in its plastering and the transformation of its apertures, in one of its construction phases we again find what appears to be a bedroom with an interior latrine and another latrine for communal use open to the courtyard.43 Once again, we are looking at the seat of a possible palace service department that, due to its relationship with space No. 10, R. Castejón y Martínez de Arizala (1945, 39–40) linked to the head of the palace guard.

The stables with four preserved mangers next to this residential complex (Nos. 9, 11 and 12) would have been at the service of the head of these departments, whose status is also reflected in the use of cavalry to move around.44

The so-called Upper Buildings (Nos. 6 and 7, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 18 and Figure 19) also have spaces that evidence a certain hierarchical relationship between its different occupants. They may have been linked by their southern corridor, of which nothing has been preserved, and may, therefore, have formed a single complex (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 480–81). The architecture and large courtyards of these edifices are unique in the Qaṣr and raise important questions about their functionality, both because we do not know what archaeological finds were made during their excavation and because they underwent major reforms.45 From its architectural structure we can deduce that the Western Building (No. 6, Figure 19) had at least one residential room that was hierarchically superior to the others. It is in the middle of the northern corridor and is once again characterised by the bedroom–latrine combination, although, in this case, the latrine was also accessible from the courtyard in some of its phases (Figure 14).46 The functionary whose bedroom it was must have been in charge of the activities carried out in the edifice, although he may also have been in charge of the Eastern Building (No. 7). Given its proximity to the Qaṣr’s northern gate, in this case we have proposed as a hypothesis an activity relating to the provision of food to the palace, the butchering of meat and other culinary tasks carried out by multiple servants (Vallejo Triano 1995, p. 77). Although this Eastern Building has rooms that could be considered to be living spaces, it is interesting to note, once again, that there is only one latrine open to the courtyard for the use of all the workers in this area and, therefore, a lack of any clear hierarchical structure, such as that seen in the adjacent dwelling.

Figure 19.

Upper Buildings, Nos. 6 and 7. © Conjunto Arqueológico de Madinat al-Zahra.

Another building (No. 2, Figure 13) that we can also consider to have been related to palace service is that situated to the east of the Dār al-Mulk. Although its southern half has been lost due to the collapse of the anthropic landfill that supported the terrace, we can clearly recognise two corridors of rooms around a courtyard and we can assume there was another on the western side (Almagro 2007, p. 37, Figures 2 and 4). Of those preserved, none stands out hierarchically over the others, although we can observe a latrine open to the courtyard and not associated with any bedroom, which would affect its consideration as a working and/or living space for the service staff. Despite the current difference in level between this dwelling and the Dār al-Mulk (2 metres), we believe that, in the initial phase of the caliphal residence, when it had a bath at its end that was lower than the current level, the two edifices may have been connected by their western corridor. That would make this complex the first service area linked to the Dār al-Mulk (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 142, 266, 474).47

5. Conclusions

The analysis of the buildings that make up the “private” zone of the Qaṣr—with the exception of the Court of the Pillars—allows us to identify four types of inhabitant: the caliph and the heir; one of the high functionaries dedicated to administrative management; various functionaries who supervised the palace’s domestic maintenance tasks; and, together with them, all the servants.

According to the hierarchy principle that dominated Islamic social formation, as explained in the works of the philosophers of the time, especially al-Farabi (Acién Almansa 1998, pp. 954–56), strictly speaking everybody is considered to be a servant, although there are different grades among them. This is reflected quite precisely in the epigraphy: from the caliph who, following the tradition of the Umayyad caliphs of the East, presented himself as the servant of God (cAbd Allāh) and incorporated that expression into his protocolary titles, to the ḥājib, who appears as the “servant of the caliph”—cabd amῑr al-mumi’minῑn—as in the case of al-Manṣūr (Almanzor) (Barceló 2013, pp. 172, 179) and all the palatine hierarchy of fatà(s) and mawlà(s) who are also named as “servants of the caliph” (Martínez Núñez 1995, pp. 142, 144–45).

The residence of cAbd al-Raḥmān III not only indicates the beginning of the construction of the Alcazar and the symmetrical axis based on which the initial palace appears to have been developed, but also, and especially, the principle of a hierarchical organisation as a guiding factor in the urban planning of Madīnat al-Zahrā’, as it was built on the highest spot of the site and, therefore, at the pinnacle of the whole political and social structure (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 132, 467–68). In the adoption of this guiding principle we can see unequivocal proof of the active participation of the sovereign—and his heir—in the design of the city, which must have been defined, at the very least, by the establishment of the “basic spatial relations” between the different parts of the palace and the city. This can be seen in other Abbasid capitals, such as Bagdad and Samarra, where the sources tell us how the caliphs were involved in different aspects of their planning (Milwright 2001, pp. 81–83).

The different architectural concepts of the two caliphal residences are also a response to specific commissions that we have to link to decisions based on the different concepts of the role and the image that each of their occupants would have wished to transmit. In one case, the idea of visual domination prevails as a symbolic reference to the power, given that it is presented as a residence open to the exterior, with a large decorative façade and no courtyard or many of the other elements characteristic of a residence. In al-Ḥakam’s dwelling, more innovative in all its aspects, we see a prevalence of the environmental qualities related to the creation of a framework of architecture, water and gardens suitable for holding more private majālis. A well-known anecdote handed down to us by Ibn Jāqān and al-Maqqarī (Puerta Vílchez 2004, p. 337, note 24) places al-Ḥakam, Jacfar and al-Munḏir in a private garden with a pool in the which the ḥājib is bathing and the caliph is encouraging the faqīh to join him. The sources do not indicate where this took place, but it could well have been in this residence and would evoke this type of meeting.

Common to both residences is a single-person bath of a similar type, each located at the eastern end of the respective residence, a situation we also we find in the bath of the Rooms Adjoining the Hall of cAbd al-Raḥmān III. Thus, the model of caliphal residence in Madīnat al-Zahrā’ was composed of a living area and a bath.

In addition to the caliphal residences, the buildings allow us to recognise two types of palace headquarters that could be representative of other lesser-known ones in the Qaṣr. One is of an administrative nature and related to the government of the state, such as the so-called House of Jacfar, and the other is linked to the tasks of running the Alcazar.

The residence of the ḥājib Jacfar al-Ṣiqlābī in this sector should be considered exceptional, given that most of the administrative magistratures were centralised in the eastern part of the Qaṣr (Vallejo Triano 2010, p. 500). Of particular note in its architectural programme is its functional adaptation to the important role it played through the tripartite building, as well as the use of elements, such as the horseshoe arch, the decorated façade and the materials used, such as the marble of its floors. All these are evidence of the very high status of the personage, as all are the exclusive prerogative of official architecture, including the caliphal residences. In many aspects, the House of Jacfar also reveals its close relationship and unequivocal personal links with the governing family, demonstrated both in the opening of the residence towards that of the caliph al-Ḥakam and in the decorative elements that evidence a direct connection between them.

The analysis also allows us to recognise the palace headquarters that we associate with the running and management of the Qaṣr. Their identification through the indicated markers is new in the panorama of palace architecture in these cities founded by the caliphate.

From a typological perspective, the seats of the palace headquarters and the service departments correspond more closely to the Islamic social formation residential model with a central courtyard than to the caliphal residences and headquarters of the administrative magistratures. However, unlike that “typical” residence conceived as a domestic family unit, which has been described by various scholars,48 what distinguishes these is the existence in their interior of one or several hierarchised rooms. These have diverse architectural forms, but are always characterised by the direct association of a latrine with the main bedroom, regardless of whether there were other latrines open to the courtyard that were for shared use by the rest of the residents or users of the house. Their organisation reflects a mixed spatial environment in which the residence of the head of the palace service department coexisted with the servants’ working areas. These dwellings exhibit evidence of relations of dominance and dependence of some parties over others (Vallejo Triano 2010, p. 476).

The limited space allotted to the residences in these headquarters in each of the buildings (e.g., Nos. 11, 12 and 9) could also be evidence that their occupants either lived alone or had no or very little family. Building No. 6 appears to be an exception, as it has a large number of rooms, several of them clearly residential. This can be seen from, among other features, the internal niches and the fact that the latrine associated with the bedroom was also accessible from the courtyard and, therefore, could have been used by other people. Both elements appear to be more in keeping with the idea of a family structure, although they could also be evidence of the existence of different organisational levels.

The analysed edifices also reveal clear hierarchies in these palace headquarters. These are manifested by the presence of singular architectural distributions, such as parallel perpendicular rooms and front porticos, as well as by the quality of the materials used in the bedrooms and the courtyards and the location and functioning of the latrines. In this respect, the area of the head of the kitchen department in Service House No. 12 appears to be one of the most important excavated to date.49

With respect to the servants’ living quarters, in some cases they may have been in the same building as those of the head of the palace department under whom they worked, or in its proximity. This can be seen in area No. 10, if we consider that the guard was made up of men of ṣaqāliba origin and that they were under the supervision of the headquarters located in Residence No. 9. In other cases, such as building No. 2, there is an area destined for the servants, as we have no clear evidence of a palace department headquarters, at least one of the importance of those already described. Likewise, edifices Nos. 6 and 7 have rooms that could have been to accommodate servants.

In others, however, such as residences Nos. 11 and 12, there was no accommodation for the numerous servants who would have been needed for the preparation and serving of food. Those residences would have been for the supervising fityān, but not for the servants who would have spent part of their daily activity in them and whose residence would have been in another part of the palace. The same can be said of the servants who would have been at the service of the caliph and the heir for their day-to-day needs, as those caliphal residences also had no nearby residential areas for the large number of people that must have been needed, regardless of the staff devoted to preparing meals, in the case of the crown prince, or who could have lived in building No. 2, in the case of the Dar al-Mulk.

Everything leads us to believe that most of these workers would have lived either in the western zone of the Qaṣr, which has yet to be excavated, or more likely and in accordance with Ibn Galib (Vallvé Bermejo 1986, p. 674), in the western zone of the city, where, according to that author, “a large part of the soldiers of al-Zahra” also lived.50 Altogether, the servants, mainly slaves, part of the fityān, the functionaries and the soldiers would have been so numerous that they would have had to have been accommodated outside the Qaṣr. The existence of two small mosques—detected by aerial photography and archaeological prospection—in that area is in keeping with this information. At other places, such as Samarra, it has also been shown that, when the city was at the peak of its development, the large number of servants who worked in the Dār al-Khilāfa would have lived outside the palace, in areas adjacent to but differentiated from the (elite/official) residential and administrative zones (Northedge 2005, pp. 144–48).

Author Contributions

Writing original draft A.V.T. and I.M-T. Review & editing I.M-T. and A.V.T. Preparation of plans and photos I.M-T.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acién Almansa, Manuel. 1987. Madīnat al-Zahrā’ en el urbanismo musulmán. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 1: 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Acién Almansa, Manuel. 1998. Sobre el papel de la ideología en la caracterización de las formaciones sociales. La formación social islámica. Hispania 58: 915–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acién Almansa, Manuel. 2001. La formación del tejido urbano en al-Andalus. In La Ciudad Medieval: De la Casa al Tejido Urbano. Edited by Jean Passini. Cuenca: University of Castilla-La Mancha, pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Acién Almansa, Manuel, and Antonio Vallejo Triano. 1998. Urbanismo y Estado islámico: de Corduba a Qurṭuba-Madīnat al-Zahrā’. In Genèse de la ville islamique en al-Andalus et au Maghreb occidental. Edited by Patrice Cressier and Mercedes García-Arenal. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. pp. 107–36. [Google Scholar]

- Acién Almansa, Manuel, and Eduardo Manzano Moreno. 2009. Organización social y administración política en al-Andalus bajo el emirato. Territorio, sociedad y poder Anejo nº 2: 331–348. [Google Scholar]

- Almagro, Antonio. 2001. La arquitectura en al-Andalus en torno al año 1000: Medina Azahara. In La península ibérica en torno al año 1000. VII Congreso de Estudios Medievales (León, 1999). León: Fundación Sánchez Albornoz, pp. 166–91. [Google Scholar]

- Almagro, Antonio. 2007. The Dwellings of Madīnat al-Zahrā’: A Methodological Approach. In Revisiting al-Andalus. Perspectives on the Material Culture of Islamic Iberia and Beyond. Edited by Glaire D. Anderson and Mariam Rosser-Owen. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Felix. 2017. Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean. A History. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barceló, Carmen. 2013. Lisboa y Almanzor (374 H./985 d. C.). Conimbriga 52: 165–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castejón y Martínez de Arizala, R. 1945. Excavaciones del Plan Nacional en Medina Azahara (Córdoba). Campaña de 1943. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación Nacional, Comisaría general de excavaciones arqueológicas. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, K. A. C. 1989. A Short Account of Early Muslim Architecture. Revised and supplemented by James W. Allan. Aldershot: Scholar Press. [Google Scholar]

- El-Cheikh, Nadia M. 2005. Revisiting the Abbadid Harems. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 1: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Cheikh, Nadia M. 2010. The "Court" of al-Muqtadir: Its space and its occupants. In Abbasid Studies II: Occasional Paper of the School of Abbasid Studies, Leuven 28 June–1 July 2004. (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, 177). Edited by John Nawas. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 319–36. [Google Scholar]

- El-Cheikh, Nadia M. 2011. Court and courtiers. A preliminary investigation of Abbasid terminology. In Court Cultures in the Muslim World: Seventh to Nineteenth Centuries. Edited by Albrecht Fuess and Jan-Peter Hartung. Doha: Routedge, pp. 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, Christian. 1978. Spanish-islamische Systeme sich kreuzender Bögen III: Die Aljaferia in Zaragoza. Madrider Forschungen 12. Berlín: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Fentress, Elizabeth. 2013. Reconsidering Islamic Houses in the Magreb. In De la Estructura Doméstica al Espacio Social. Lecturas Arqueológicas del uso Social del Espacio. Edited by Sonia Gutierrez and Ignasi Grau. Alicante: University of Alicante, pp. 237–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fierro, Maribel. 2011. Abderramán III y el califato Omeya de Córdoba. San Sebastián: Nerea. [Google Scholar]

- García Sanjuán, Alejandro. 2008. Legalidad islámica y legitimidad política en el Califato de Córdoba: La proclamación de Hišām II. Al-Qanṭara 29: 45–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Lloret, S. 2015. Casa y casas: Reflexiones arqueológicas sobre la lectura social del espacio doméstico medieval. In La Casa Medieval en la Península Ibérica. Edited by Mª Elena Díez Jorge and J. Navarro Palazón. Madrid: Sílex ediciones, pp. 17–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ḥayyān, Ibn. 1967. Anales Palatinos del califa de Córdoba al-Ḥakam II, por cĪsā ibn Ahmad al-Rāzī (360–364 H. = 971–975 J. C.). Traduced by Emilio García Gómez. Madrid: Sociedad de Estudios y Publicaciones. [Google Scholar]

- Ḥayyān, Ibn. 1981. Crónica del califa cAbdarraḥmān III an-Nāṣir entre los años 912 y 942 (al-Muqtabis V). Traduced by por Mª Jesús Viguera and Federico Corriente. Zaragoza: Anubar Ediciones, Instituto Hispano-Árabe de Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs, W.P. 1995. Ṣāḥib”, The Encyclopaedia of Islam: New Edition. Leiden: Brill, vol. VIII, pp. 830–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Giménez, Félix. 1975. El alminar de ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III en la mezquita mayor de Córdoba. Génesis y repercusiones. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Giménez, Félix. 1985. Madīnat al-Zahrā’. Arquitectura y decoración. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Martín, Alfonso. 1987. Los jardines de Madīnat al-Zahrā’. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 1: 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Labarta, Ana, and Carmen Barceló. 1987. Las fuentes árabes sobre al-Zahrā’: Estado de la cuestión. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 1: 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Provençal, Évariste. 1976. España Musulmana hasta la caída del califato de Córdoba (711-1031 de J.C.). In Historia de España, 4th ed. Directed by Ramón Menéndez Pidal. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, vol. IV. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Provençal, Évariste. 1982. Instituciones y vida social e intelectual. In España musulmana hasta la caída del califato de Córdoba (711-1031 de J. C.). Historia de España, 4th ed. Directed by Ramón Menéndez Pidal. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, vol. V, pp. 1–330. [Google Scholar]

- López-Cuervo, Serafín. 1983. Medina-Az-Zahra. Ingeniería y formas. Madrid: Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Urbanismo. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano Martos, Rafael. 1995. Casas y palacios en la Sevilla almohade. Sus antecedentes hispánicos. In Casas y palacios de al-Andalus. Edited by Julio Navarro Palazón. Barcelona-Granada: Fundación El Legado Andalusí-Lunwerg Editores, pp. 315–52. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano Moreno, Eduardo. 2004. El círculo de poder de los califas omeyas de Córdoba. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 5: 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano Moreno, Eduardo. 2006. Conquistadores, emires y califas. Los omeyas y la formación de al-Andalus. Barcelona: Crítica. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, Manuela. 2000. Mujeres en al-Andalus. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, Manuela. 2004. Altos funcionarios para el califa: jueces y otros cargos de la Administración de ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 5: 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Núñez, Mª Antonia. 1995. La epigrafía del Salón de ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III. In Madīnat al-Zahrā’. El Salón de ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III. Edited by Antonio Vallejo Triano. Córdoba: Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Cultura, pp. 109–152. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Núñez, Mª Antonia. 1999. Epígrafes a nombre de al-Ḥakam en Madīnat al-Zahrā’. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 4: 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Núñez, Mª Antonia. 2015. Recientes hallazgos epigráficos en Madīnat al-Zahrā’ y nueva onomástica relacionada con la dār al-ṣinaʽa califal. Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 1: 1–76. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Núñez, Mª Antonia, and Manuel Acién Almansa. 2004. La epigrafía de Madinat al-Zahra. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 5: 107–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoli-Guintard, Christine. 1997. Remarques sur le fonctionnement d´une capitale à double polarité: Madīnat al-Zahrā’-Cordoue. Al-Qanṭara XVIII 1: 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Meouak, Moham. 1999. Pouvoir Souverain, Administration Centrale et Élites Politiques dans l´Espagne Umayyade (II-IV / VIII-X Siècles). Helsinki: Academia Scientiarium Fennica. [Google Scholar]

- Meouak, Moham. 2004. Ṣaqâliba, Eunuques et Esclaves à la Conquête du Pouvoir. Géographie et Histoire des Élites Politiques «Marginales» dans l´Espagne Umayyade. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarium Fennica. [Google Scholar]

- Milwright, Marcus. 2001. Fixtures and Fittings. The Role of Decoration in Abbasid Palace Design. In A Medieval Islamic City Reconsidered. An Interdisciplinary Approach to Samarra. Edited by Chase F. Robinson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 79–109. [Google Scholar]

- Northedge, Alastair. 2005. The Historical Topography of Samarra. Samarra Studies I. London: The British School of Archaeology in Irak, Fondation Max van Berchem. [Google Scholar]

- Ocaña Jiménez, Manuel. 1990. Inscripciones árabes fundacionales de la Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 2: 9–28. First published 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ocaña Jiménez, Manuel. 1976. Ŷaʿfar el eslavo. Cuadernos de la Alhambra 12: 217–23. [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela Uzal, Antonio. 1996. Casas y palacios nazaríes. Siglos XIII-XV. Barcelona-Madrid: El Legado Andalusí-Lunwerg Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Pavón Maldonado, Basilio. 1966. Memoria de la excavación de la mezquita de Medinat al-Zahra. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación Nacional. [Google Scholar]

- Puerta Vílchez, José Miguel. 2004. Ensoñación y construcción del lugar en Madīnat al-Zahrā’. In Paisaje y naturaleza en al-Andalus. Edited by Fátima Roldán Castro. Granada: Junta de Andalucía, El Legado Andalusí, pp. 313–338. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles, D. Fairchild. 2000. Gardens, Landscape, and Vision in the Palaces of Islamic Spain. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vallvé Bermejo, Joaquín. 1986. La descripción de Córdoba de Ibn Galib. In Homenaje a Pedro Sanz Rodríguez. Madrid: Fundación Universitaria Española, vol. 3, pp. 669–79. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez Bosco, Ricardo. 1912. Medina Azzahra y Alamiriya. Madrid: Junta para ampliación de estudios e investigaciones científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez Bosco, Ricardo. 1923. Excavaciones en Medina Azahara. Memoria sobre lo descubierto en dichas excavaciones. Madrid: Junta Superior de Excavaciones y Antigüedades. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Triano, Antonio. 1987. El baño anejo al Salón de ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 1: 141–65. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Triano, Antonio. 1990. La vivienda de servicios y la llamada Casa de Ŷaʿfar. In La casa hispanomusulmana. Aportaciones de la arqueología. Edited by Jesús Bermúdez Lópe and André Bazzana. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, Casa de Velázquez, Museo de Mallorca, pp. 129–45. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Triano, Antonio. 1992. Madīnat al-Zahrā’: The Triumph of the Islamic State. In Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain. Edited by J. D. Dodds. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Triano, Antonio. 1995. El proyecto urbanístico del Estado califal: Madīnat al-Zahrā’. In La arquitectura del Islam Occidental. Edited by Rafael López Guzmán. Barcelona: Sierra Nevada 95-Fundación El Legado Andalusí-Lunwerg Editores, pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Triano, Antonio. 2004. Un elemento de la decoración vegetal de Madīnat al-Zahrā’: la palmeta. In Al-Andalus und Europa.Zwischen Orient und Okzident. Edited by M. Müller-Wiener, C. Kothe, K.-H. Golzio y and J. Gierlichs. Petersberg: Imhof, pp. 208–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Triano, Antonio. 2010. La ciudad califal de Madīnat al-Zahrā’. Arqueología de su excavación. Córdoba: Almuzara. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Triano, Antonio. 2016a. El heredero designado y el califa. El Occidente y el Oriente en Madīnat al-Zahrā’. Mainake XXXVI: 433–64. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Triano, Antonio. 2016b. Aménagements hydrauliques et ornementation architecturale des latrines de Madīnat al-Zahrā’: un indicateur de hiérarchie sociale en contexte palatial. In Médiévales, 70. Lieux d‘hygiène et lieux d‘aisance en terre d‘Islam. Paris: Presses Universitaries de Vincennes, pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, Antonio, Alberto Montejo, and Andrés García. 2004. Resultados preliminares de la intervención arqueológica en la “Casa de Ya’far” y en el edificio de “Patio de los Pilares de Madinat al-Zahra. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 5: 199–239. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, Antonio, and Irene Montilla. 2006. Unpublished. Memoria de la Intervención Arqueológica Puntual en el Baño de la llamada “Casa de la Alberca” de Madīnat al-Zahrā’. Córdoba: Archivo del Conjunto Arqueológico Madīnat al-Zahrā’. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Among the copious amount of published literature on Madīnat al-Zahrā’, we can highlight (Velázquez Bosco 1912, 1923; Castejón y Martínez de Arizala 1945; Ocaña Jiménez 1976; López-Cuervo 1983; Hernández Giménez 1985; Acién Almansa 1987; Ruggles 2000; Martínez Núñez 1995; Martínez Núñez and Acién Almansa 2004; Almagro 2007; Vallejo Triano 1990, 1995, 2007, 2010, 2016a). The edifices excavated outside the Alcazar are the congregational mosque (Pavón Maldonado 1966) and a small neighbourhood mosque near a stretch of the southern wall. |

| 2 | The term used to express the palace complex in the Abbasid period in both physical and symbolic terms, at least during the 9th and 10th centuries, was dār. Dār al-khilāfa in particular was “used not only to denote the buildings but also the establishment surrounding the emperor or court” (El-Cheikh 2011, p. 82). |

| 3 | It is known that the heir was the only one the caliph’s numerous children who was allowed to reside in the Qaṣr Ibn (Ḥayyān 1981, pp. 20–22). |

| 4 | See especially (Hernández Giménez 1985; Vallejo Triano 1995, 2010, 2016a; Almagro 2007). |

| 5 | We use the term “private” to differentiate this sector, situated to the west of the stables, from that occupied mainly by the administrative and political representation buildings, which are concentrated to the east and can be considered as “official” or “public” (Vallejo Triano 1992, pp. 28, 30; Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 132, 153–54; Almagro 2001, pp. 171–72). Although a division of this type can be corroborated in Samarra (Northedge 2005, p. 144), the difficulty of defining a line between these two functions—private and public—can be clearly seen in this study. |

| 6 | Hernández Giménez (1985, p. 75) attributed a bureaucratic function to it, while A. Vallejo has theorised that it was used for meetings linked to the so-called Hall of the Double Columns (2010, pp. 395, 488). |

| 7 | Those buildings have been classified from the point of view of their architectural typology by A. Almagro (2001, 2007), although that analysis does not allow us to determine either their function or their possible reform phases. |

| 8 | One approach to the multiplicity of trades existing in the Alcazar—some of them undertaken by just one person—can only be glimpsed from the information provided by the written sources for the Abbasid caliphate. See (El-Cheikh 2010, pp. 331–32). |

| 9 | To designate each of the architectural complexes we are going to analyse, in this paper we will use the numbering that is repeatedly used in the publications of Vallejo (especially 2010) and also corresponds to that used in the Madinat al-Zahra Archaeological Complex itself. |

| 10 | The identification of the harem from an archaeological point of view is highly complex, although, from Ibn Ḥayyān’s account (Ḥayyān 1981, pp. 15–18), we can deduce that it was a clearly defined complex near the caliphal residence and with a complex spatial division and bedrooms at least for the main wives. M. Marín (2000, pp. 283–87) has specified the large number of women who lived in the Alcazar—more than 6000—and some of the specialised functions they carried out, both in the more official area, e.g., as calligraphers, and in the domestic sphere close to the caliph, among which we can infer control of the caliphal wardrobe. She also refers to its complex internal hierarchy, among which, of particular note, in addition to the eunuchs, were the palace intendants (qahramānāt). A similar situation is indicated by El-Cheikh (El-Cheikh 2005, pp. 6–12; El-Cheikh 2010, pp. 319–25) for the harem in the palace of the Abbasid caliph al-Muqtadir. |

| 11 | The precise arguments supporting this identification can be found in A. Vallejo Triano (2016a, pp. 440–50). |

| 12 | From the time of the emirate, Dār al-Mulk was the name used to refer to the emir’s residence, as documented by Ibn Ḥayyān (1981, p. 22). |

| 13 | Ibn Ḥayyān (1981, p. 359) mentions the building of a palace at al-Zahra in 329 H/940–941 that we have to interpret as the construction of his own personal residence. |

| 14 | This organisation of long parallel halls with bedrooms at the end and communicated by tripartite openings was the model for other palace-residences belonging to the Umayyad elite, such as the munya al-Rummaniyya. This relationship was pointed out by Ch. Ewert (1978, pp. 25, 30, Figure 17) and followed by other authors. |

| 15 | Regarding the characteristics of this staircase, its vaults and its decoration, see (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 286–87, ills. 234–35; pp. 413–14, ill. 350). |

| 16 | The singularity of this type of flooring was pointed out by (Velázquez Bosco 1912, pp. 66–67, Ills. XVI, XXXVII-XXXVIII; Hernández Giménez 1985, pp. 44–45, 82, 94; López-Cuervo 1983, pp. 50–51). |

| 17 | This flooring is, therefore, a reinterpretation of a type that already existed in the mosque of Córdoba at least from the late-9th century, although in that building it was applied to the wall decoration (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 350–51). |

| 18 | As examples we can cite the city of Vascos and the fortresses of Gormaz and Tarifa. |

| 19 | Regarding the importance of the palmette in the decoration of Madīnat al-Zahrā’ and its symbolism, see (Hernández Giménez 1985, pp. 134–36 and especially Vallejo Triano 2004). |

| 20 | See, for example, (Lévi-Provençal 1976, pp. 370–71; Lévi-Provençal 1982, pp. 316–21; Marín 2004, pp. 96–97; Manzano Moreno 2006, pp. 200, 376; Fierro 2011, pp. 15–16; Vallejo Triano 2016a, pp. 434–36). |

| 21 | This room, called al-majlis al-gharbī (Western Hall) in the sources, has recently been identified as the so-called “Central Pavilion” situated opposite the Hall of cAbd al-Raḥmān III or the al-majlis al-sharqī (Eastern Hall) (Vallejo Triano 2016a, pp. 450–54). |

| 22 | López-Cuervo (1983, p. 77) was the first to identify this residence as the “House of the Prince”, although without explaining the arguments that led him to that conclusion. |

| 23 | The explicit relationship of the proximity between the two residences in Ibn Ḥayyān’s text can be found in the Arabic edition and not in the Spanish translation, see (Vallejo Triano 2016a, p. 437, note 39). |

| 24 | Although the stratigraphic reading of this wall allows us to identify various rebuilding processes, its analysis and interpretation require an archaeological excavation. |

| 25 | This was the explanation given by Herzfeld for the double opposing structures of some of the houses in Samarra (Creswell 1989, p. 373). |

| 26 | Regarding this minaret, built in 952, and the structure of its different windows, see (Hernández Giménez 1975, pp. 61–81). |

| 27 | Regarding these two baths in Madīnat al-Zahrā’ and their ornamental programme, see (Vallejo Triano 1987). |

| 28 | The location, function and characteristics of the pieces that make up this ornamental programme, as well as that of the bath adjoining the Hall of cAbd al-Raḥmān III, have been analysed by A. Vallejo Triano (2010, pp. 244, 249, 428–29, 443, 456–57). |

| 29 | The identification of these families—“somewhat more than a dozen”—and the relations between them to maintain their areas of influence have been studied by Manzano Moreno (2004, pp. 20–25). |

| 30 | The other two decorated zones were the entrance to the central nave of this hall, whose decoration has been restored, and the entrance door to this person’s bedroom. |

| 31 | This argumentation was developed in another study (Vallejo Triano 2004, pp. 214–16, 220–21) in which the palmette was evaluated as an iconographic element of great significance to the Umayyads and the jambs as a particularly symbolic location in the caliphal decorative programmes, as they expressed a testimony of tradition and dynastic continuity. We can also see this in al-Ḥakam II’s enlargement of the mosque of Córdoba, where the jambs of the miḥrāb were one of the places destined to express that relationship with his family lineage by situating in this space the pairs of columns transferred from the “old” miḥrāb of cAbd al-Raḥmān II (Ocaña Jiménez [1988] 1990, pp. 14, 24). |

| 32 | There is some argument over whether two capitals bearing epigraphs in the name of al-Ḥakam, supposedly found in the Dār al-Mulk, may have come from this façade. They were dated by M. Ocaña to 364/974–975, although Mª Antonia Martínez Núñez (1999, pp. 88–89) brings their dating forward to 362/972–973. The discussion of the origin and chronology of these pieces can be found in Vallejo Triano (2010, pp. 370–372, 426). |

| 33 | The inclusion of this area as part of the residence of Ŷaʿfar has been disputed by A. Almagro (2007, p. 44) who, although he also identifies it as a service area, does not believe that communication to be likely. On the other hand, recently F. Arnold (2017, pp. 98–100) has limited this residence to just the hall of the three naves (that we interpret as a work and representation area), although without introducing any argument in this respect. |

| 34 | This polysemic word is used to designate the titleholder or person responsible for a magistrature or an administrative or palace post. Regarding the meaning and definition of these aṣhāb as “possessor, owner, lord, chief”, see (Heinrichs 1995, pp. 830–31). |

| 35 | This situation contrasts with that of the administrative area, where these “offices” or “magistratures”, from the highest to the lowest, are relatively well-known. |

| 36 | The precise data can be found in (Meouak 2004, pp. 135–37; Lévi-Provençal 1976, pp. 330–31). |

| 37 | These channels form part of the drainage network that ran below the buildings of the Alcazar. They were used to remove the waste generated in the inhabited spaces. |

| 38 | An initial approach to this dwelling can be found in (Vallejo Triano 1990, pp. 129–31); for an analysis of its building phases see, by the same author (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 144–45). |

| 39 | In around 941–942, this palace post was vaunted by Ṭarafa ibn cAbd al-Raḥmān (Ibn (Ḥayyān 1981, p. 367)), who occupied other administrative posts at other times. Regarding this personage, Martínez Núñez and Acién Almansa (2004, pp. 120–21) have suggested the possibility that he was the same fatà and mawlà of the caliph al-Nāṣir whose name appears in an epigraph in the Dār al-Mulk and on a brick in that same residence. |

| 40 | As one of us has analysed elsewhere (Vallejo Triano 2016b, pp. 92–93), the latrines are a basic element of the Qaṣr’s hygiene system and a clear indicator of social hierarchisation, as they denote the category and the social status of the resident. In this case, that hierarchy is evidenced by its direct connection to the bedroom, its functioning with running water and its marble flooring. |

| 41 | Subsequently, probably during the caliphate of Hishām II, an upper floor was built to the north of this courtyard; it was supported by columns and wooden beams and was accessed by a staircase, part of which has been preserved (Hernández Giménez 1985, p. 66). |

| 42 | Regarding the description, decorative features and axonometry of this staircase, see A. Vallejo Triano (2010, pp. 279, 281, 293, Ills. 226–227). |

| 43 | This latrine was the result of an alteration made in the area at the bottom of a staircase that connected it with the Western Service House. |

| 44 | This was the last access point on horseback in this sector of the Alcazar (Vallejo Triano 2010, p. 267). |

| 45 | Regarding these Upper Buildings, see (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 132, 142–43, 266, 474-475, 477). |

| 46 | This latrine also had a marble floor, although it is not clear whether it had running water. |

| 47 | This dwelling also appears to have had a connection from the lower terrace of the Qaṣr via a raised walkway above the corridor we know as the “alley of the water” (No. 19). The entrance would have been through the eastern corridor, where part of a door sealed up on its outer wall has been preserved (Vallejo Triano 2010, p. 266). |

| 48 | Among others, M. Acién Almansa (2001), E. Fentress (2013) and S. Gutiérrez Lloret (2015). |

| 49 | It is also the only one of those we have found reflected in the court chronicles to date. See Note 39. |

| 50 | The analysis of that western part of the Alcazar and the medina can be found in (Vallejo Triano 2010, pp. 184–85, 227–28). For the mid-10th century, the sources raise the number of the stipendiary troops at the service of the caliph to some 5000 soldiers (Acién Almansa and Manzano Moreno 2009, p. 335), a part of which would have been quartered in Madīnat al-Zahrā’ and would have carried out the duties of a palatine guard. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).