Tenacious Tendrils: Replicating Nature in South Italian Vase Painting

Abstract

:1. Introduction

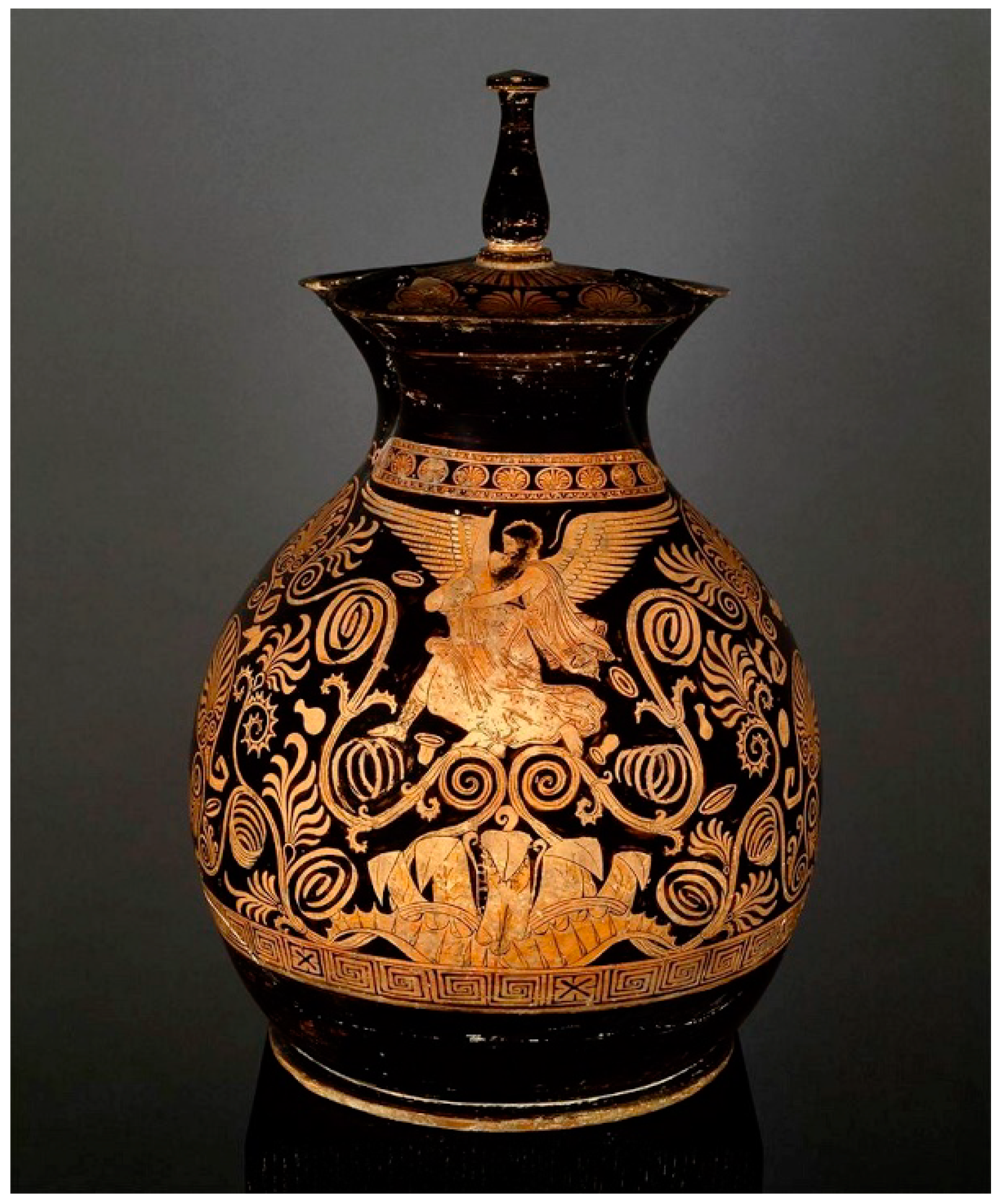

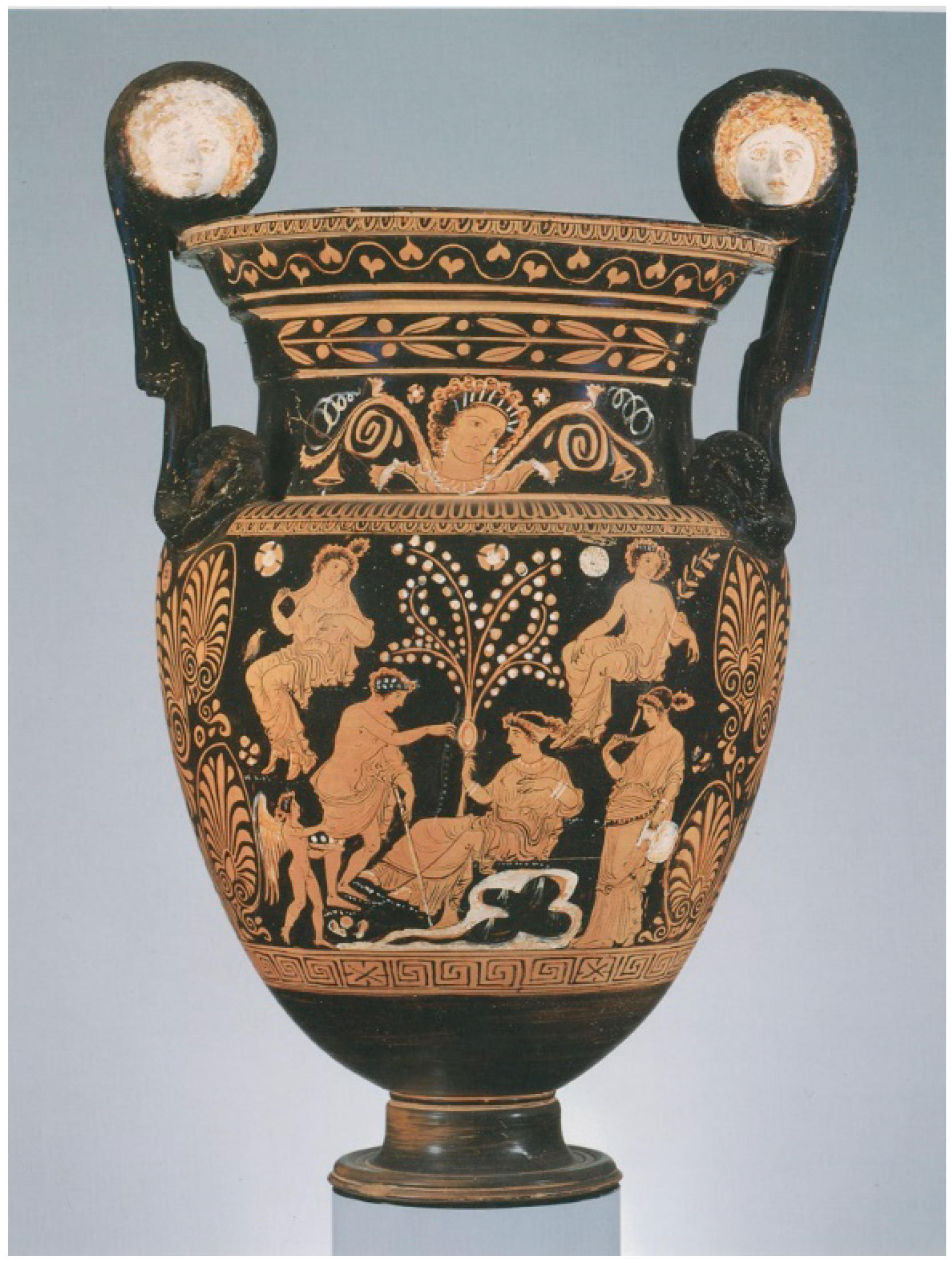

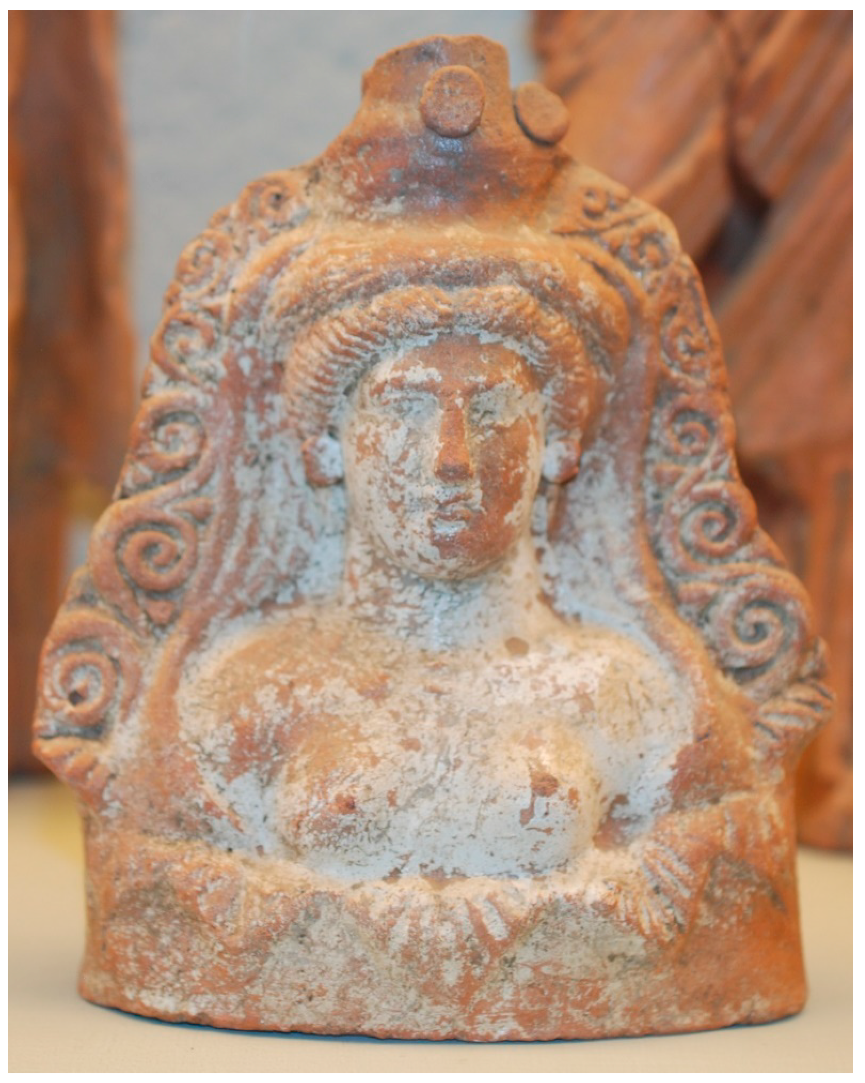

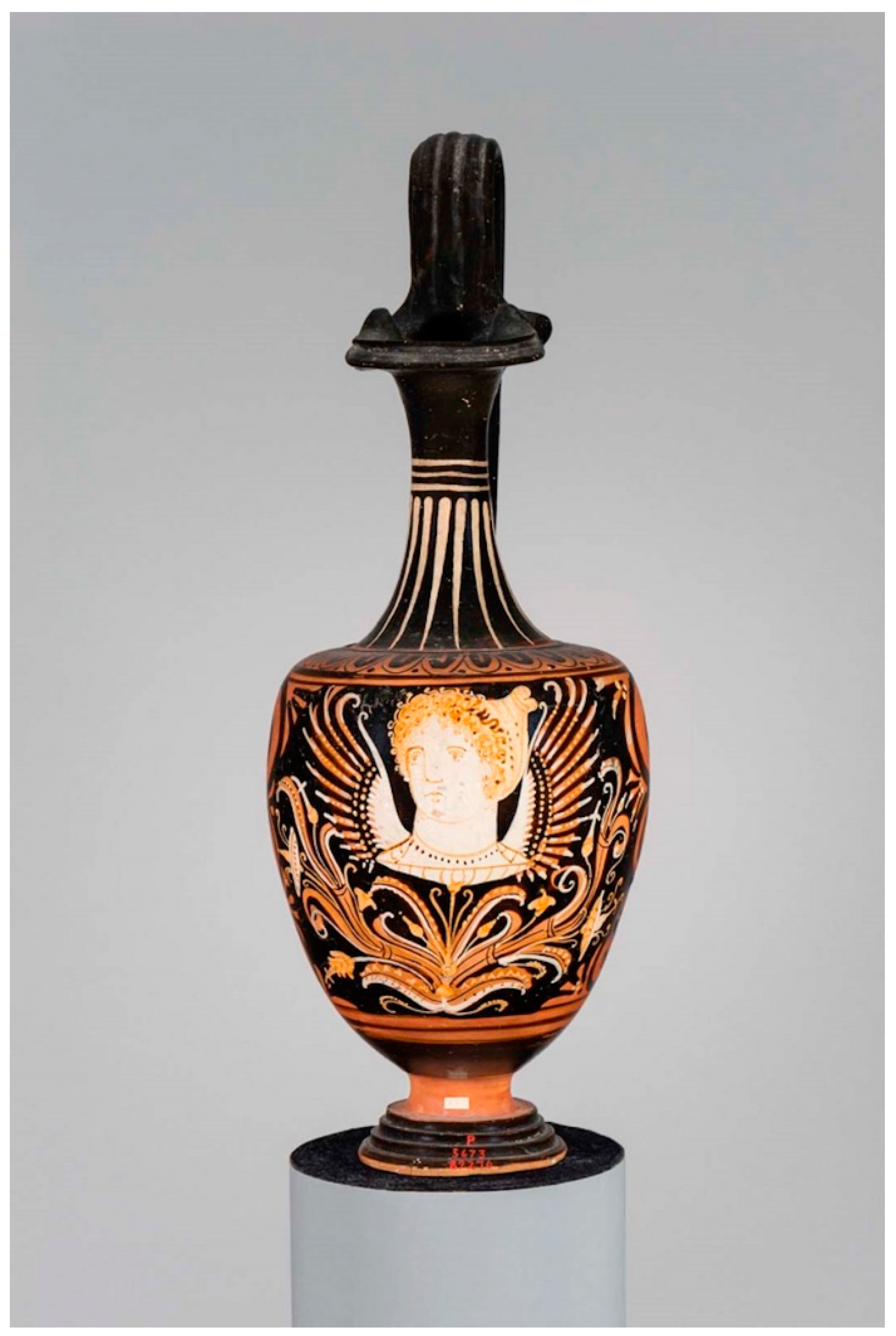

2. A Phenomenon Blossoms

3. The Garden’s Inhabitants

4. Horticulture for the Hereafter?

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alcock, Joan P. 2006. Food in the Ancient World. Westport: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Amor-Prats, Diego, and Jeffrey B. Harborne. 1993. New Sources of Ergoline Alkaloids within the Genus Ipomoea. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 21: 455–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreae, Bernard, ed. 2007. Malerei für die Ewigkeit. Die Gräber from Paestum. Munich: Hirmer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Bardel, Ruth. 2000. Eidôla in epic, tragedy, and vase-painting. In Word and Image in Ancient Greece. Edited by N. K. Rutter and Brian A. Sparkes. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 140–60. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, Hellmut. 1993. The Greek Plant World in Myth, Art and Literature. Portland: Timber Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bazant, Jan. 1994. s.v. “Thanatos”. Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae VII: 904–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bedello Tata, Margherita. 1990. Terrecotte votive. Catalogo del Museo Provinciale Campano. Volume IV Oscilla, Thymiateria, Arulae. Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Benassai, Rita. 2001. La Pittura dei Campani e dei Sanniti. Rome: “L’Erma” di Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Bendinelli, Goffredo. 1915. Un ipogeo sepolcrale a Lecce con fregi scolpiti. Ausonia 8: 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bernabé, Alberto, and Ana Isabel Jiménez San Cristóbal. 2008. Instructions for the Netherworld: The Orphic Gold Tablets. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Bernabò Brea, Luigi. 1952. I rilievi tarantini in pietra tenera. Rivista dell’Istituto Nazionale d’Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte 1: 5–241. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, John. 2001. The History of Greek Vases. Potters, Painters, and Pictures. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Buschor, Ernst. 1937. Feldmäuse. Munich: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, Paloma. 2005. El dios entre las flores. El mundo vegetal en la iconografia de la Magna Grecia. In Paraíso cerrado, jardín abierto. El reino vegetal en el imaginario religioso del Mediterannáneo. Edited by R. Olmos, P. Cabrera and S. Montero. Madrid: Ediciones Polifemo, pp. 147–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, Paloma. 2018. Orfeo en los Infiernos. Imágenes apulias del destino del alma. ‘Ilu. Revista de Ciencias de las Religiones 23: 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambitoglou, Alexander. 1954. Groups of Apulian Red-Figured Vases Decorated with Heads of Women or Nike. Journal of Hellenic Studies 74: 111–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilla, Gilberto, and Carl A. P. Ruck. 2017. Allucinogeni sacri nel mondo antico. Mitologia ierobotanica. Torino: Nautilus. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, Thomas H. 2003. The Native Market for Red-Figure Vases in Apulia. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 48: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, Thomas H. 2011. Dionysos and the Blessed on Apulian Red-Figured Vases. In A Different God? Dionysos and Ancient Polytheism. Edited by Renate Schlesier. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 253–61. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Joseph Coleman. 1970. Relief Sculptures from the Necropolis of Taranto. American Journal of Archaeology 74: 125–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Joseph Coleman. 1973. The Figure in the Naiskos-Marble Sculptures from the Necropolis of Taranto. Opuscula Romana 9: 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Joseph Coleman. 1976. The Sculpture of Taras. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. n.s., 65, no. 7. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Casadio, Giovanni, and Patricia A. Johston, eds. 2009. Mystic Cults in Magna Graecia. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clairmont, Christoph W. 1993. Classical Attic Tombstones. Volume 6. Indexes. Kilchberg: Akanthus. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Robert Manuel. 1997. Greek Painted Pottery, 3rd ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Brian, Bernard Ashmole, and Donald Emrys Strong. 2005. Relief Sculpture of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Costabile, Felice, ed. 1991. I ninfei dei Locri Epizefiri. Architettura, culti erotici, sacralità delle acque. Catanzaro: Rubbettino Editore. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea, Jeanne D. 1982. Ancient Herbs in the J. Paul Getty Museum Gardens. Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum. [Google Scholar]

- De Juliis, Ettore M. 1984. Gli ori di Taranto in Età Ellenistica. Milan: Arnoldo Mondadori Editore. [Google Scholar]

- De Puma, Richard Daniel. 2013. Etruscan Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- De Velasco, Francisco Diez. 1995. Los caminos de la muerte: religion, rito e iconografia del paso al mas alla en la Grecia antigua. Madrid: Editorial Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Detienne, Marcel. 1979. Dionysos Slain. Translated by Mirelle Muellner, and Leonard Muellner. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donati, Angela, and Paolo Pasini. 1997. Pesca e pescatori nell’antichità. Milan: Leonardo arte. [Google Scholar]

- Drougou, S. 1987. Toύφασμα της Βεργίνας. Πρώτες παρατηρήσεις. In Aμητος, Τιμητικός τόμος για τονκαθηγητή Μανόλη Aνδρόνικο, Μέρος πρώτο. Thessaloniki: Panepistemio, pp. 303–23. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds, Radcliffe G. 2013. Redefining Ancient Orphism. A Study in Greek Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, Lorenzo. 2017. Il papavero da oppio nella cultura e nella religione romana. Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandis, Pablo, José Herranz, and Juan J. Martínez-Sánchez. 1999. Effect of fire on hard-coated Cistacaea seed banks and its influence on techniques for quantifying seed banks. Plant Ecology 144: 103–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontannaz, Didier. 2005. La Céramique proto-apulienne de Tarente: Problèmes et perspectives d’une ‘recontextualisation’. In La Céramique apulienne: Bilan et perspectives. Edited by Martine Denoyelle, Enzo Lippolis, Marina Mazzei and Claude Pouzadoux. Naples: Centre Jean Bérard, pp. 125–42. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, Hallie M. 2018. The World Underfoot. Mosaics and Metaphor in the Greek Symposium. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Froning, Heide. 1985. Zur Interpretation vegetabilischer Bekrönung klassicher und spätklassicher Grabstelen. Archäologischer Anzeiger 100: 218–29. [Google Scholar]

- García, Jorge Tomás. 2015. Pausias de Sición. Rome: Giorgio Bretschneider Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, Robert. 1985. The Greek Way of Death. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giesecke, Annette. 2014. The Mythology of Plants. Botanical Lore from Ancient Greece and Rome. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, Fritz, and Sarah Iles Johnston. 2007. Ritual Texts for the Afterlife: Orpheus and the Bacchic Gold Tablets. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, Emanuele. 1970. Il pittore di Afrodite. Benevento: Museo di Sannio. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Edward Lee, and Frank B. Egerton. 1983. Landmarks of Botanical History, Part 1. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, William Keith Chambers. 1935. Orpheus and Greek Religion. A Study of the Orphic Movement. London: Methuen & Co., Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Harari, Maurizio. 1995. An Etruscan Bowl Decorated with a Woman’s Head in Floral Surround. In Classical Art in the Nicholson Museum, Sydney. Edited by Alexander Cambitoglou and E. G. D. Robinson. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, pp. 203–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, Gavin, and Laurence Totelin. 2016. Ancient Botany. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Heuer, Keely. 2011. The Development and Significance of the Isolated Head in South Italian Vase-Painting. Ph.D. thesis, New York University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Heuer, Keely. 2015. Vases with Faces: Isolated Heads in South Italian Vase-Painting. Metropolitan Museum Journal 50: 62–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, Keely. 2018. The Face of Hope: Isolated Heads in South Italian Visual Culture. In Hope in Ancient Literature, History, and Art. Edited by George Kazantzidis and Dimos Spatharas. Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, pp. 297–327. [Google Scholar]

- Heuer, Keely. Forthcoming. Purposeful Polysemy: Cross-cultural Reception in South Italian Vase-Painting. In Griechische Vasen als Kommunikations-Medium, Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum Österreich Beiheft 3. Edited by Claudia Lang-Auinger and Elisabeth Trinkl. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Hofmann, Albert. 1963. The Active Principles of the Seeds of Rivea Corymbosa and Ipomoea Violacea. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University 20: 194–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, Albert. 1971. Teonanácatl and Ololiuqui. Two Ancient Magic Drugs of Mexico. Bulletin on Narcotics 1: 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg, Erik John. 1992. On the Rycroft Painter and Other Athenian Black-Figure Vase-Painters with a Feeling for Nature. Jonsered: P. Åströms Förlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hurwit, Jeffrey M. 1991. The Representation of Nature in Early Greek Art. In New Perspectives in Early Greek Art. Edited by Diana Buitron-Oliver. Hanover and London: National Gallery of Art, pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsthal, Paul. 1927. Ornamente Griechischer Vasen. Berlin: Frankfurters Verlags-Anstalt. [Google Scholar]

- Jannot, Jean-René. 2009. The Lotus, Poppy, and other Plants in Etruscan Funerary Contexts. In Etruscan by Definition. The Cultural, Regional and Personal Identity of the Etruscans. Papers in Honor of Sybille Haynes. Edited by Judith Swaddling and Philip Perkins. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Jashemski, Wilhelmina Feemster, and Frederick G. Meyer, eds. 2002. The Natural History of Pompeii. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jucker, H. 1961. Das Bildnis in Blätterkelch. Lausanne and Freiburg: Urs Graf-Verlag Olten. [Google Scholar]

- Kerényi, Karl. 1950. Die Orphische Kosmogonie und der Ursprung der Orphik. Zurich: Rhein Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, Otto. 1922. Orphicorum Fragmenta. Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer, Martin F. 1977. The Shoulder Bust in Sicily and South and Central Italy: A Catalogue and Materials for Dating. Göteborg: P. Åström. [Google Scholar]

- Klumbach, Hans. 1937. Tarentiner Grabkunst. Reutlingen: Gryphius-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kossatz-Deißmann, Anneliese. 1990. Nachrichten aus dem Martin-von-Wagner Museum Würzburg: Eine neue Phrygerkopf-Situla des Toledo-Malers. Archäologischer Anzeiger 105: 505–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kunisch, Norbert. 1989. Griechische Fischteller. Natur und Bild. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz, Donna C., and John Boardman. 1971. Greek Burial Customs. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langlotz, Ernst. 1954. Aphrodite in den Gärten. Heidelberg: C. Winter. [Google Scholar]

- Langridge-Noti, Elizabeth. 2003. Mourning at the Tomb: A Re-evaluation of the Sphinx Monument on Attic Black-figured Pottery. Archäologischer Anzeiger 1: 144–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lippolis, Enzo. 1987. Organizzazione delle necropoli e struttura sociale nell’Apulia ellenistica: Due esempi, Taranto e Canosa. In Römische Gräberstraßen: Selbstdarstellung, Status, Standard; Kolloquium in Munchen vom 28. bis 30. Oktober 1985. Edited by Henner von Hesberg and Paul Zanker. Munich: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 139–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lippolis, Enzo. 1990. Emergenze e problemi archeologici: Manduria, Taranto, Heraclea. Manduria: Regione Puglia Centro Regionale Servizi Educativi e Culturali. [Google Scholar]

- Lippolis, Enzo. 1994. Catalogo del Museo Nazionale Archeologico di Taranto. Vol. 3, part 1, Taranto, la necropolis: Aspetti e problemi della documentazione archeologica tra VII e I sec. A.C. Taranto: La Colomba. [Google Scholar]

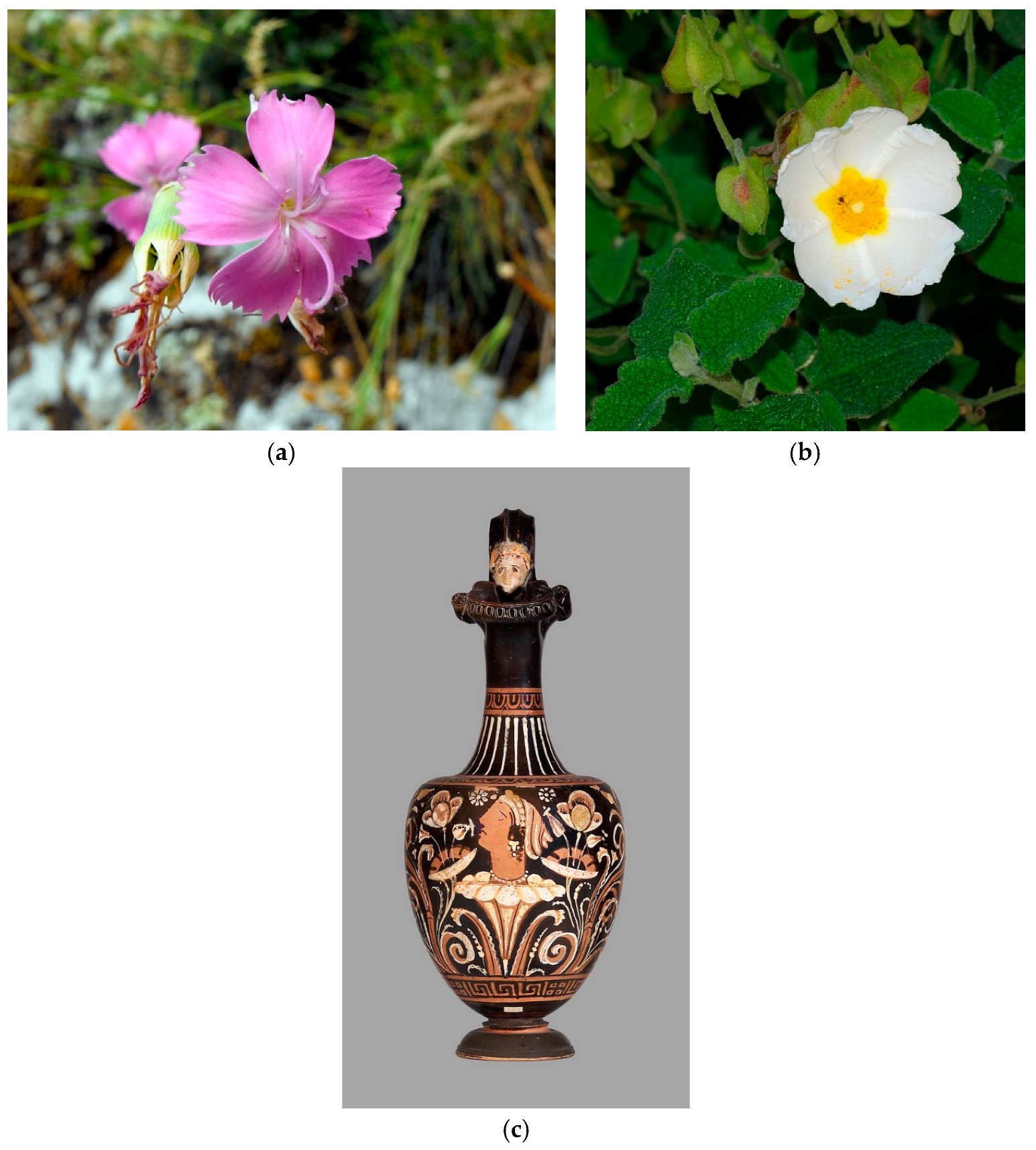

- Lippolis, Enzo. 2007. Tipologie e significati del monumento funerario nella città ellenistica: Lo sviluppo del naiskos. In Architetti, architettura e città nel Mediterraneo antico. Edited by Donatella Calabi, Carmelo G. Malacrino and Emanuela Sorbo. Milan: Mondadori, pp. 82–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, Geoffrey Ernest Richard. 1983. Science, Folklore and Ideology: Studies in the Life Sciences in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Bristol Classical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann, Hans. 1979. Grabmäler auf Unteritalischen Vasen. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Maddoli, Gianfranco. 1996. Cults and Religious Doctrines of the Western Greeks. In The Western Greeks. Edited by Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli. Milan: Bompiani, pp. 481–98. [Google Scholar]

- McPhee, Ian, and Arthur Dale Trendall. 1987. Greek Red-Figured Fish-Plates. In Antike Kunst Beiheft 14. Basel: Vereinigung d. Freunde Antiker Kunst. [Google Scholar]

- McPhee, Ian, and Arthur Dale Trendall. 1990. Addenda to Greek Red-Figured Fish-Plates. Antike Kunst 33: 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, G. R. S. 1965. Orpheus. London: Watkins. [Google Scholar]

- Merkelbach, Reinhold, and Martin Litchfield West. 1967. Fragmenta Hesiodea. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, Henri. 1951. Les Représentations dans la céramique attique du IVe siècle. Paris: E. de Boccard. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, Alan G. 1981. History of Botanical Science: An Account of the Development of Botany from Ancient Times to the Present Day. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nalimova, Nadezda. 2017. The Origin and Meaning of Floral Imagery in the Monumental Art of Macedonia (4th–3rd centuries B.C.). In Macedonian-Roman-Byzantine: The Art of Northern Greece from Antiquity to the Middle Ages: Proceedings of the Conference. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo “KDU”, pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Lucie G. 1977. The Rendering of Landscape in Greek and South Italian Vase Painting. Ph.D. thesis, State University of New York, Binghamton, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, John H. 2003. Death and the Child. In Coming of Age in Ancient Greece. Images of Childhood from the Classical Past. Edited by Jenifer Neils and John Howard Oakley. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 163–94. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, John H. 2004. Picturing Death in Classical Athens. The Evidence of the White Lekythoi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orfismo in Magna Grecia. 1975. Orfismo in Magna Grecia: Atti del quattordicesimo convegno di studi sulla Magna Grecia, Taranto, 6–10 ottobre 1974. Naples: Arte Tipografica. [Google Scholar]

- Peifer, Egon. 1989. Eidola und andere mit den Sterben verbundene Flügelwesen in der attischen Vasenmalerei in spätarchaischer und klassicher Zeit. Frankfurt: P. Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Petsas, Photios. 1965. Mosaics from Pella. In La Mosaïque Gréco-Romaine. Paris, 29 Août—3 Septembre 1963. Paris: Centre National de la Recherché Scientifique, pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pfrommer, Michael. 1982. Großgriechischer und mittelitalischer Einfluß in der Rankenornamentik frühhellenistischer Zeit. Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 97: 119–90. [Google Scholar]

- Pignatti, Sandro. 2011. Flora d’Italia. 3 vols. Milan: Edagricole. [Google Scholar]

- Pontrandolfo, Angela. 1990. La pittura funeraria. In Magna Grecia: Arte e artigianato. Edited by Giovanni Pugilese Carratelli. Milan: Electa, pp. 351–90. [Google Scholar]

- Pontrandolfo, Angela. 1996. Wall-Painting in Magna Graecia. In The Western Greeks. Edited by Giovanni Pugilese Carratelli. Milan: Bompiani, pp. 457–70. [Google Scholar]

- Pontrandolfo, Angela, and Agnès Rouveret. 1992. Le tombe dipinte di Paestum. Modena: Franco Cosimo Panini Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Prückner, Helmut. 1968. Die Lokrischen Tonreliefs. Beitrag zur Kultgeschichte von Lokroi Epizephyrioi. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Pugliese Carratelli, Giovanni, ed. 1988. Magna Grecia: Vita religiosa e cultura letteraria, filosofica e scientifica. Milan: Electa. [Google Scholar]

- Pugliese Carratelli, Giovanni. 2003. Les Lamelles d’or orphiques: Instructions pour le voyage d’outre-tombe des initiés grecs. Translated by Alain-Philippe Segonds, and Concetta Luna. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. [Google Scholar]

- Reger, Gary. 2005. The Manufacture and Distribution of Perfume. In Making, Moving, and Managing: The New World of Ancient Economies, 323–31 B.C. Edited by Zofia H. Archibald, John K. Davies and Vincent Gabrielsen. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 253–97. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, Gisela Marie Augusta, and Margherita Guarducci. 1961. The Archaic Gravestones of Attica. London: Phaidon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway, Brunilde Sismondo. 1993. The Archaic Style in Greek Sculpture, 2nd ed. Chicago: Ares Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, Martin. 1965. Greek Mosaics. Journal of Hellenic Studies 85: 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, Martin. 1967. Greek Mosaics: A Postscript. Journal of Hellenic Studies 87: 133–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, Martin. 1975. A History of Greek Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Edward G. D. 1990. Workshops of Apulian Red-Figure Outside Taranto. In Eumousia: Ceramic and Iconographic Studies in Honour of Alexander Cambitoglou. Edited by J.-P. Descoeudres. Sydney: Mediarch, pp. 179–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde, Erwin. 1907. Psyche: Seelencult und Unsterblichkeitsglaube der Griechen. Tübingen: Mohr. [Google Scholar]

- Rumpf, Andreas. 1950–51. Anadyomene. Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 65–66: 166–74. [Google Scholar]

- Russenberger, Christian. 2015. Der Tod und die Mädchen. Amazonen auf römischen Sarkophagen. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Salzmann, Dieter. 1982. Untersuchungen zu den antiken Kieselmosaiken. Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough, John. 1978. Theophrastus on Herbals and Herbal Remedies. Journal of the History of Biology 11: 353–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schauenburg, Konrad. 1957. Zur Symbolik unteritalischer Rankenmotive. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Intituts, Römische Abteilung 64: 198–221. [Google Scholar]

- Schauenburg, Konrad. 1962. Pan in Unteritalien. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Intituts, Römische Abteilung 69: 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Schauenburg, Konrad. 1974. Bendis in Unteritalien? Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 89: 137–86. [Google Scholar]

- Schauenburg, Konrad. 1981. Zu unteritalischen Situlen. Archäologischer Anzeiger 96: 462–88. [Google Scholar]

- Schauenburg, Konrad. 1982. Arimaspen in Unteritalien. Revue archéologique, 249–62. [Google Scholar]

- Schauenburg, Konrad. 1984a. Unterweltsbilder aus Grossgriechenland. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Intituts, Römische Abteilung 91: 359–87. [Google Scholar]

- Schauenburg, Konrad. 1984b. Zu einer Hydria des Baltimoremalers in Kiel. Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 99: 127–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Margot. 1975. Orfeo e Orfismo nella pittura vascolare italiota. In Orfismo in Magna Grecia: Atti del quattordicesimo convegno di studi sulla Magna Grecia, Taranto, 6–10 ottobre 1974. Naples: Arte Tipografica, pp. 105–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Cathrin. 2016. Aphrodite in Unteritalien und auf Sizilien. Heiligtümer und Kulte. Heidelberg: Verlag Archäologie und Geschichte. [Google Scholar]

- Sgouropoulou, Chrisi. 2000. H Eikonographia ton Gynaikeion Kephalon sta Aggeia Kerts. Archaiologikon Deltion 55: 213–34. [Google Scholar]

- Siebert, Gérard. 1981. Eidôla. Le problem de la figurabilité dans l’art grec. In Méthodologie iconographique. Actes du colloque de Strasbourg 27–28 avril 1979. Edited by Gérard Siebert. Strasbourg: AECR, pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sourvinou-Inwood, Christiane. 1978. Persephone and Aphrodite at Locri: A Model for Personality Definitions in Greek Religion. The Journal of Hellenic Studies 98: 101–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoop, Maria Wilhelmina. 1960. Floral Figurines from South Italy. Assen: Royal Vangorcum Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Thanos, Costas A., Kyriacos Georghiou, Costas Kadis, and C. Pantazi. 1992. Cistaceae: A Plant Family with Hard Seeds. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences 41: 251–63. [Google Scholar]

- Todisco, Luigi. 2017. Sulla vexata quaestio dei vasi con naiskoi. Ostraka 27: 165–91. [Google Scholar]

- Todisco, Luigi. 2018. Vasi con naiskoi tra Taranto e centri italici. In Inszenierung von Identitäten. Unteritalische Vasenmalerei zwischen Griechen und Indigenen. Edited by Ursula Kästner and Stefan Schmidt. Munich: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Torelli, Mario. 1977. I culti di Locri. In Locri Epizefirii. Atti del sedicesimo convegno di studi sulla Magna Grecia. Taranto 3–8 Ottobre 1976. Naples: Arte Tipografica, pp. 147–84. [Google Scholar]

- Trendall, Arthur Dale. 1967. The Red-Figured Vases of Lucania, Campania, and Sicily. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trendall, Arthur Dale. 1973. The Red-Figured Vases of Lucania, Campania, and Sicily. Second Supplement, London: Institute of Classical Studies, University of London. [Google Scholar]

- Trendall, Arthur Dale. 1983. The Red-Figured Vases of Lucania, Campania, and Sicily. Third Supplement, London: Institute of Classical Studies, University of London. [Google Scholar]

- Trendall, Arthur Dale. 1987. The Red-Figured Vases of Paestum. London: British School at Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Trendall, Arthur Dale, and Alexander Cambitoglou. 1978. The Red-Figured Vases of Apulia, 1. Early and Middle Apulian. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trendall, Arthur Dale, and Alexander Cambitoglou. 1982. The Red-Figured Vases of Apulia, 2. Late Apulian. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trendall, Arthur Dale, and Alexander Cambitoglou. 1983. First Supplement to The Red-Figured Vases of Apulia. London: Institute of Classical Studies, University of London. [Google Scholar]

- Trendall, Arthur Dale, and Alexander Cambitoglou. 1991–1992. Second Supplement to the Red-Figured Vases of Apulia. London: Institute of Classical Studies, University of London. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiafakis, Despoina. 2003. ‘ΠΕΛΩΡA’: Fabulous Creatures and/or Demons of Death? In The Centaur’s Smile. The Human Animal in Early Greek Art. Edited by J. Michael Padgett. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meijden, Hellebora. 1993. Terrakotta-Arulae aus Sizilien und Unteritalien. Amsterdam: Verlag Adolf M. Hakkert. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeule, Emily. 1979. Aspects of Death in Early Greek Art and Poetry. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Villard, François. 1998. Le renouveau de décor floral en Italie méridionale au IVe siècle et la peinture grecque. In L’Italie méridionale et les premières expériences de la peinture hellénistique. Actes de la table ronde organisée par l’École française de Rome (Rome, 18 févier 1994). Rome: École française de Rome, pp. 203–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vokotopoulou, Ioulia. 1990. Oι ταφικοί τύμβοι της Aίνειας. Athens: Ekdose tou Tameiou Archaiologikon Poron kai Apallotrioseon. [Google Scholar]

- Vollkommer, Rainer. 1997. s.v. “eidola”. Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae VIII: 566–70. [Google Scholar]

- West, Martin Litchfield. 1983. The Orphic Poems. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Dyfri, and Jack Ogden. 1994. Greek Gold. Jewellery of the Classical World. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woysch-Méautis, Daphné. 1982. La representation des animaux et des êtres fabuleux sur les monuments funéraires grecs de l’Époque archaïque à la fin du IVe siècle av. J.-C. Lausanne: Bibliothèque historique vaudoise. [Google Scholar]

- Zuntz, Günther. 1971. Persephone: Three Essays on Religion and Thought in Magna Graecia. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The most extensive discussion of the use of vegetal ornament in Greek vase painting, with a particular focus on Attic vases, is (Jacobsthal 1927, especially pp. 159–98). |

| 2 | Certain Attic black-figure vase painters like Exekias, however, did put greater emphasis upon indicating natural landscapes through their inclusion of animals, trees, bushes, mounds of earth, and rocks, yet there is little naturalism in their rendering (Nelson 1977, pp. 14–19, 27–31; Hurwit 1991, pp. 40–55; Holmberg 1992). Floral motifs, however, do appear in other media in Athens, namely akroteria and anthemia grave stele starting in the third quarter of the 5th century B.C. |

| 3 | Floral tendrils appear on a total of 1071 Apulian vases published in (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 1982, 1983, 1991–1992). Other similar pieces with the motif have continuously come to light since the early 1990s on the art market as well as in controlled excavations. For the purpose of this study, however, Trendall and Cambitoglou’s work has been used as a broad sample pool. |

| 4 | For examples of the spotted breccia, see the rock to which Andromeda is chained on the hydria Berlin inv. 3238 (Trendall 1967, p. 227, no. 8, pl. 89, 1–3) and the vases of the Spotted Rock Group (ibid., pp. 234–45; Trendall 1973, pp. 189–90; Trendall 1983, pp. 120–21). For a lava flow, see Adolphseck, Schloß Fasanerie 164 (Trendall 1967, p. 312, no. 619, pl. 123, 6) by the Caivano Painter. |

| 5 | E.g., London, British Museum F 277 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 8/5, p. 193); Boston 1970.235 (ibid., 8/11, p. 194); and St. Petersburg 567 = St. 878 (ibid., 8/12, p. 194). |

| 6 | Within the sample pool, 596 volute-kraters feature floral tendrils. |

| 7 | Such as on the shoulders of Taranto 8935 from Canosa (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 13/4, p. 338) and London, British Musuem F 331 (ibid., 13/5, p. 338), both attributed to the Varrese Painter, ca. 360–350 B.C. The amphora is the second most frequent shape on which flowering vines appear, occurring on 166 examples in Trendall and Cambitoglou’s publications. |

| 8 | For example, the in the central band on the body of Naples 3242 attributed to the Group of Ruvo 423 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 15/44, p. 404) and on the shoulders of Berlin F 3239 and F 3240 by the Darius Painter (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 18/22 and 18/23, p. 490). The motif occurs on 75 loutrophoroi and 48 barrel-amphorae within the sample pool. |

| 9 | See the band around the belly of Naples Stg. 37 by the Varrese Painter (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 13/30, p. 342). Floral tendrils are painted on 14 pieces in the sample pool. |

| 10 | London, V&A 2493.1910 (ibid., 15/6, p. 396, pl. 137, 5–6). |

| 11 | E.g., Kassel T. 561 (ibid., 16/78, p. 430; CVA Kassel 2 pls. 77 and 78, 1–2) and Louvre K 100 (ibid., 16/80, p. 430), both related in style to the Chini Painter. A total of 16 pelikai with the motif are in Trendall and Cambitoglou’s catalogs. Other small shapes on which the floral tendrils repeatedly occur are oinochoai (24 examples), kantharoi (22 pieces), and mugs (10 examples). |

| 12 | For example, Ruvo 1372 (ibid., 15/36, p. 402) and Dublin 1880.1106 (ibid., 15/37, p. 402, pl. 142, 1–2) by the Painter of the Dublin Situla. The motif occurs on only four situlae, and it appears with the same frequency on kylikes, pyxides, lekythoi, and askoi. |

| 13 | Such as on Munster 678 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 21/11, p. 606, pl. 232, 2) and Lecce 719 (ibid., 21/19, p. 606; CVA Lecce 2 IV Dr pl. 46, 6–8), both attributed to the Alabastra Group. A total of 22 alabastra decorated with floral tendrils are in the sample pool. |

| 14 | As on Cambridge, Fogg Art Museum 1972.235 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 21/33, p. 608) and Taranto 117116 (ibid., 21/40, p. 608). Ten squat lekythoi with the motif are found in Trendall and Cambitoglou’s publications. |

| 15 | The only two bottles in the sample pool are Karlsruhe B 43 (ibid., 21/31, p. 608; CVA Karlsruhe pl. 71, 1) and Metaponto 27545 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 21/32, p. 608, pl. 233, 6). |

| 16 | For an overview of perfume manufacturing and distribution in the Classical world, see (Reger 2005). |

| 17 | See the floral tendrils flanking a female head in three-quarter view to left on the shoulder of the Campanian hydria Louvre K 276 attributed to the Libation Painter (Trendall 1967, p. 406, no. 301, pl. 160, 1). |

| 18 | Such florals are most frequently found on vases of the Clusium Group and Tondo Group, both of which believed to have been based in Chiusi, although some of the earlier Clusium Group may have been made in Volterra. For examples, refer to the pair of skyphoi New York 07.286.33 and 51.11.1 (De Puma 2013, p. 211) and Sydney, Nicholson Museum 6847 (Harari 1995). |

| 19 | Paestum 20303 (Trendall 1987, pp. 21, 237–8, no. 963, pl. 145). For more information on the Aphrodite Painter, see (Greco 1970). The only other Paestan vase-painter to include floral decoration in their work is the Floral Painter, one of the last Paestan red-figure artists, named for the flowering tendrils surrounding the female head on the reverse of a bottle found in Tomb 5 (1954) at Contrada Andriuolo in Paestum (Paestum 5426: Trendall 1987, pp. 333–34, no. 586, pl. 218b,c). |

| 20 | Seen particularly on terracotta arulae (portable altars) such as Capua inv. 5324 (Bedello Tata 1990, pp. 59–60, pl. X, 2–3), Capua 5320 (ibid., pp. 62–63, pl. XII, 1), and Trieste inv. 2333/34 (Van der Meijden 1993, p. 331, pl. 16), and the floral thymiateria bases found primarily in the sanctuaries of Hera at Paestum (Stoop 1960, pl. IV, 4 and V, 1). |

| 21 | Such as on the gold diadem from Crispiano, Contrada Cacciavillani dated to the first half of the 4th century B.C. (Taranto 54.114, found in 1934—De Juliis 1984, pp. 118–19) and the gold Herakles knot diadem with pendants from Ginosa Marina, Contrada Chiaradonna (Taranto 22.406, found in 1927—ibid., pp. 121–22) of the late 4th or early 3rd century B.C. For discussion of floral decoration in Greek gold jewelry, see (Williams and Ogden 1994, pp. 41–43). |

| 22 | Franks (2018, pp. 151–56 and 174–77) proposes that the popularity of the floral tapestry style mosaics is due to their being well suited to the space of the andron as they do not privilege any viewing angle, are readable even when the sightline is obscured, and can easily accommodate other figural themes within them. She argues that their inclusion within the sympotic space may have been intended to evoke in the minds of the banqueters a rustic or primordial paradise. |

| 23 | Michael Pfrommer and François Villard in particular have argued in favor of southern Italian influences on Macedonian art, pointing in particular to the similar tendril decoration found in both areas (Pfrommer 1982, pp. 129–32; Villard 1998, pp. 218–20). Others, however, have expressed doubts regarding their proposal (e.g., Drougou 1987, p. 313 and Vokotopoulou 1990, pp. 40–41), Nalimova (2017) favors the development of floral imagery in multiple areas of the Greek world, namely southern Italy, Attica, and the Argolid that in turn influenced Macedonian visual culture. |

| 24 | For further information on Theophrastos and the impact of his scholarship in the study of botany and medicine, see Scarborough 1978; Morton 1981, pp. 29–43; Lloyd 1983, pp. 119–35; Greene and Egerton 1983, pp. 128–211; Baumann 1993, pp. 15–18; and Hardy and Totelin 2016, pp. 8–10. |

| 25 | e.g., Oxford 1945.55, an alabastron attributed to the Chini Painter (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 16/74, p. 429), and on the neck of the obverse of St. Petersburg inv. 1711 = St. 371 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 17/71, p. 471), a volute-krater by the Loebbecke Painter. |

| 26 | See the sphinxes in floral settings on the necks of these volute-kraters: University of Mississippi, David M. Robinson Memorial Collection krater attributed to the Loebbecke Painter (ibid., 17/69, p. 470) and Geneva HR 44 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1991–1992, 17/77, p. 135, pl. XXXII, 3–4). |

| 27 | Sirens are found in floral surrounds on a variety of shapes including the volute-krater Naples 3255 (inv. 81934, Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 18/42, p. 496), the loutrophoros Bari 5591 (ibid., 28/107, p. 928), and a pelike once on the French Market by the Painter of the Siren Citharist (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1983, 18/334b, p. 87). For the use of Amazons, sirens, and sphinxes in Greek funerary iconography, see Richter and Guarducci 1961, pp. 6–7; Kurtz and Boardman 1971, pp. 86 and 134–35; Woysch-Méautis 1982, pp. 83–87. 134–36. 91–99. 137–140; Ridgway 1993, pp. 232–34; Tsiafakis 2003; Langridge-Noti 2003, pp. 144–45; Cook et al. 2005, pp. 34–35 and 42–64; and Russenberger 2015, pp. 231–97. |

| 28 | In Taranto, these large vases were used as grave markers (Lippolis 1994, pp. 109–28; Fontannaz 2005, p. 126) and were particularly favored grave goods in the elite Italic rock-cut chamber tombs of central and northern Apulia. The Italic demand for these monumental pieces is likely what led two of the most prominent Apulian workshops of the third-quarter of the 4th century B.C., led by the Patera and Baltimore Painters, to establish themselves in the native communities of Ruvo and Canosa respectively (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, p. 450; Robinson 1990; Carpenter 2003). |

| 29 | Seen on the neck of a volute-krater attributed to the Bassano Group in a private collection in Naples (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 30/20, p. 1020–21, pl. 393). |

| 30 | The divine couple appear together on the pelike London, V & A 2493.1910 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 15/6, pl. 137, 5–6) and on the shoulder of an amphora possibly by the Darius Painter once on the French market (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1991–1992, 18/47c, p. 148). |

| 31 | A silen holding a cithara appears on one side of an alabastron once on the Roman market (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 21/22, p. 606, pl. 232, 7). |

| 32 | Such as on Dublin 1880.1106 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 15/37, p. 402, pl. 142, 1–2) and Canberra, Australian National University U.H. 6 (ibid., 16/79, p. 430). |

| 33 | See Apollodorus, Bibliotheca III, 38; Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica 4.25.4; Pausanias, Description of Greece 2.37.6; and Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 251. |

| 34 | Refer to Kern, Orphicorum fragmenta fr. 210, Diodoros Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica 3.62.6; and Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 167. The most recent discussions of the cult of Dionysos in Magna Graecia, along with substantial earlier bibliography, may be found in Casadio and Johston 2009. For representations of Dionysos in Apulian vase-painting, see Carpenter 2011. |

| 35 | For example, see the interior of the patera attributed to the Patera Painter’s workshop from Altamura now in Taranto (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 23/295, p. 764) and on the neck of a volute-krater attributed to the Baltimore Painter in a German private collection (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1991–1992, 27/22-2, p. 273). Another example of a narrative with a flying protagonist surrounded by flowering vines is the representation of Phrixos on the Ram on the fragment of the neck of a volute-krater in Taranto (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 18/42a, p. 497). |

| 36 | Refer to the chous Louvre K 35 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 15/11, p. 396, pl. 139, 1), where the figures are dwarfed by the floral decoration surrounding them. |

| 37 | Ganymede’s abduction by Zeus in the form of an eagle occurs on the neck of a volute-krater attributed to the Baltimore Painter in a Swiss private collection (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 25/1, p. 795–96). |

| 38 | Eidola most frequently appear on late Archaic and Classical white ground lekythoi, but they do appear on occasionally on other Attic shapes. |

| 39 | London, British Museum E 477, ca. 460–430 B.C. (ARV2 1114, 15). See also (Vermeule 1979, p. 18). |

| 40 | In Euripides’ Hippolytus, Theseus compares the dead Phaedra to a bird that has vanished from the hand (828–29), and in his Consolation to his Wife, written on the occasion of his toddler daughter’s death, Plutarch compares the soul to a captured bird who becomes domesticated and used to this mortal life (611e). For an earlier association of birds with the deceased in Attica, see their inclusion in prothesis scenes on Geometric vases and resting on the corpse in the terracotta model of an ekphora found at Vari of the early 7th century B.C. (Garland 1985, pp. 26, 32–33). |

| 41 | e.g., on the shoulder of Taranto 7014 from Ceglie del Campo (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 28/48, p. 916). |

| 42 | Boston 03.804 (ibid., 17/75, p. 742), Swiss private collection (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 18/41, p. 496, pl. 177), and New York private collection (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1983, 28/86b, p. 174, pl. 33, 2 and 34, 2). On the last of the three, Helios, wearing a short red tunic and with rays above his head, rises instead from a flower in a floral setting. While I believe the full length figures in floral surrounds very likely have funerary connotations, my view opposes that of Schauenburg, who pointed toward the presence of Helios and Phrixos and the Ram in such contexts, which he did felt did not have demonstrable sepulchral associations. See Schauenburg 1957, pp. 208–9. |

| 43 | For example on the situla Ruvo 1372 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 15/36, p. 402), the amphora Berlin 3242 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 18/235, p. 524), and the volute-krater Trieste S 494 (ibid., 25/2, p. 796). |

| 44 | A single woman in a floral surround is found on eleven vases in the sample pool, such as Kassel T. 561 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 16/78, p. 430) and Kiel, Kunsthalle B 562 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1983, 27/60b, p. 157, pl. XXX, 2). On several occasions swans, another possible reference to Aphrodite, also appear in a floral setting in Apulian vase-painting, such as several volute-kraters once on the market in Basel (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1991–1992, 17/20-8, pl. 116), London (ibid., 22/561b, p. 217, pl. LVI, 7), and New York (ibid., 27/67e, p. 284). |

| 45 | For example, in her seduction of Anchises: Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite 58–67 (trans. Martin L. West, 2003, Loeb Edition, Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, pp. 164–65). |

| 46 | This concept was perhaps even jokingly referred to by Aristophanes in his Birds (693–701). |

| 47 | Plato, Symposium 203b-c. Here Eros’ parents are Poros (Resource) and Penia (Poverty). |

| 48 | Homer, Iliad XIV, 347–351. Another example of sexual relations set in a lush floral surround is Poseidon’s liaison with Medusa (see Hesiod, Theogony 279). |

| 49 | Homeric Hymn to Demeter, 1–21. A narcissus flower here is blamed for distracting Persephone with its seductive scent and beauty, giving Hades the opportunity to sieze her by force. Cabrera (2005, p. 159) argues that the collection of fruits and flowers by girls on the cusp of marriage is a metaphor for their nuptials, in which they too will be “gathered” and moved to a new home. She proposes that this collection was understood as a precursor to the journey to salvation after death. |

| 50 | Hesiod, fr. 140 (Merkelbach and West 1967) and Bacchylides, Fragmenta 10. |

| 51 | Heads in floral surrounds occur over six times as often as their full-length counterparts, occurring on 910 vases in Trendall and Cambitoglou’s publications. For the use and significance of the isolated head in South Italian vase-painting, see Heuer 2011 and Heuer 2015. I disagree with García’s assertion (García 2015, pp. 61–67) that this motif was drawn directly from Pausias’ famed portrait of Glycera with her floral garlands, as it is currently impossible to determine whether the painting predates the first appearance of heads in floral surrounds on Apulian vases and the abbreviation of the human form is a rarity in Greek art, but rather is a proclivity of Italic visual culture. |

| 52 | For female heads flanked by Erotes, refer to Naples 3221 (inv. 81954, Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 18/43, p. 497) and Ruvo 1092 (ibid., 23/226, p. 753) for examples. |

| 53 | See Parma C. 96 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 15/64, p. 408) and Bonn 3025 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1983, 29/116c, p. 362). |

| 54 | As seen on Bologna 567 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 23/19, p. 728) and St. Petersburg 578 (St. 354, ibid., 23/21, p. 728). |

| 55 | For example, see the winged head on the reverse of a volute-krater by the Baltimore Painter now in a private collection in Naples (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 27/27, p. 866, pl. 325, 2). On the ambiguity of winged heads in South Italian vase-painting: (Cambitoglou 1954, p. 121; Schauenburg 1957, p. 212; Schauenburg 1962, p. 37; Schauenburg 1974, pp. 169–86; Schauenburg 1981, pp. 467–69; Schauenburg 1982, pp. 250–5; and Schauenburg 1984b, pp. 155–57). |

| 56 | Examples include Vatican W4 (inv. 17162, Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 15/60, p. 408), Bari 6270 (ibid., 16/41, p. 417, pl. 154, 1-2), and Ruvo 409 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 17/40, p. 463). For the identification of heads wearing Phrygian caps in South Italian vase-painting: (Schauenburg 1974, pp. 171–72 and 174–85; Schmidt 1975, pp. 130–32; Schauenburg 1981, p. 468; Schauenburg 1982, pp. 253–55; Schauenburg 1984a, p. 364; and Kossatz-Deißmann 1990, pp. 517–20). |

| 57 | A brief bibliography of Orphism: (Rohde 1907, pp. 335–61; Guthrie 1935; Mead 1965; Orfismo in Magna Grecia 1975; Detienne 1979; Edmonds 2013). The presence of Orphic worship in Magna Graecia is supported by ancient texts that closely associate the cult with the Pythagorean movement in Magna Graecia (Herodotus 2.81; Diogenes Laertius 8.8). Pythagoras emigrated from Samos to Croton around 520 B.C. and is believed to have died in Metaponto at the end of the sixth century B.C. His followers established so-called clubhouses throughout southern Italy and Sicily until ca. 450–415 B.C., when they were destroyed during an outbreak of civil unrest (Polybius 2.39). The most concrete evidence for the practice of Orphism in Magna Graecia is provided by the famous inscribed gold lamellae, or tablets, found in tombs in Lucania at Hipponium, Thurii, and Petelia; see (Kern 1922; Pugliese Carratelli 1988, pp. 162–70; Maddoli 1996, pp. 495–96; Pugliese Carratelli 2003; Graf and Johnston 2007; Bernabé and Jiménez San Cristóbal 2008). |

| 58 | For a head of Pan, refer to Vatican AA 2 (inv. 18255, Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 8/13, p. 194), and for satyrs, see St. Petersburg 583 = St. 816 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 17/63, pp. 468–69) and New York, Fleischmann coll. F 99 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1991–1992, 18/293b, p. 162, pl. XLI, 3). |

| 59 | London, British Museum F 277: (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 8/5, p. 193). |

| 60 | Refer to Heuer (forthcoming). |

| 61 | Boston 03.804—from Ceglie del Campo, possibly by the Loebekke Group (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 17/75, p. 742). |

| 62 | London, British Museum F 279: (ibid., 18/17, p. 487). |

| 63 | Malibu 82.AE.16—attributed to the Painter of Louvre MNB 1148 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1983, 20/278a, p. 100, pl. XIX, 1–2. An illustration of the same scene with floral tendrils also appears on Taranto 8935 from Canosa and Naples 3246 (inv. 82267), earlier amphorae by the Varrese Painter (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 13/4, p. 338 and 13/22, p. 341, respectively). |

| 64 | Naples 3225 (inv. 82266), from Canosa (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 18/58, p. 500). Other vases with female heads among flowering vines and the rescue of Andromeda include Bari 5591 (ibid., 28/107, p. 928), a hydria by the Darius Painter once on the Zurich market (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1983, 18/63a, p. 78, pl. XI, 3–4), and a hydria in a German private collection attributed to the Baltimore Painter (ibid., 27/60a, p. 156, pl. XXX, 1). |

| 65 | New York 11.210.3 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 18/20, p. 489, pl. 174, 2). |

| 66 | Munich 3297 (J. 849), from Canosa (ibid., 18/282, p. 533, pl. 194; Cabrera 2018). Other depictions of the Underworld paired with figures or heads in floral surrounds occur on Karlsruhe B 4 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 16/81, p. 431); Bari, Perrone coll. 14 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 18/225, p. 523); Altamura, Museo Archeologico Nazionale A 10192 (ibid., 23/293, p. 763); Bari 2396 (ibid., 27/16, p. 863); St. Petersburg inv. 1716 = St. 426 (ibid., 27/19, p. 864); a volute-krater by the Baltimore Painter in a Swiss private collection (ibid., 27/22a, p. 865, pl. 325, 1); Kiel B 585 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1991–1992, 29/A1, p. 351); and Matera, Museo Archeologico Nazionale “D.Ridola” 164510 (ibid., 29/A2, p. 351). |

| 67 | One of the earliest examples is on Bari 1394, a volute-krater associated with the Iliupersis Painter, who was the first to paint this type of funerary scene in South Italian red-figure. On it, a frontal female head with long, loose curly hair is surrounded by spiraling tendrils on the neck directly above a grave stele topped by a helmet on the body of the vase, which is surrounded by women and men bringing offerings (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 8/101, p. 203). A few other examples of floral vines above grave naiskoi are London, British Museum F 282 by the Varrese Painter (ibid., 13/27, p. 341–42), Bonn 100 by the Lycurgus Painter (ibid., 16/14, p. 417, pl. 150, 1–2), Bari 20054 by the Gioia del Colle Painter (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 17/1, p. 457), and Malibu 80.AE.40 by the Patera Painter (ibid., 23/15, p. 728). |

| 68 | For an Apulian example, see St. Petersburg 567 = St. 878 by the Iliupersis Painter (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 8/12, p. 194; Lohmann 1979, p. 209, pl. 9, 1). For a Campanian piece, refer to the hydria New York 06.1021.230 by the Olcott Painter (Trendall 1967, p. 411, no. 342, pl. 165, 3). |

| 69 | E.g., on the base of the naiskos on the obverse of New York 1995.45.1 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1983, 18/16d, p. 72). |

| 70 | For example, on Trieste 7598 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 28/312, p. 950, pl. 372, 5–6). |

| 71 | Lohmann records 53 Apulian, six Lucanian, and two Campanian pieces. E.g., Florence 4048 (ibid., 17/59, p. 467); London, British Museum F 353 (ibid., 19/129, pl. 208, 6); and Bologna G 327/514 (ibid., 20/225, p. 583). |

| 72 | See the late 4th–early 3rd century wall reliefs Taranto inv. 51387 (from Chiesa di Sant’Antonio in Taranto) and Taranto inv. 51388 (from Corso Piemonte in Taranto). A later example is the pierced sima from Via degli Angioini in Taranto (Taranto inv. 20929). The dating of the Tarentine limestone naiskoi continues to be debated, with the earliest placed between 330 and 300 B.C. and production continuing possibly as late as the second century B.C.; see (Lippolis 1987; Lippolis 1990, pp. 15–71; and Lippolis 2007). Based on extant archaeological remains, the earliest naiskoi occurring on vases do not replicate contemporary stone monuments in Apulia, although the sculptural motifs within the naiskoi echo subjects found on Attic grave stelai of the late fifth and fourth centuries B.C. Todisco has recently proposed that the Tarentine monuments were inspired by earlier representations on Apulian vases, a motif perhaps initially influenced by mainland Greek grave monuments and developed to meet the needs of Italic aristocratic patrons (Todisco 2017; Todisco 2018). For a broader discussion of the various types of Tarentine funerary markers and the various subject matter seen in funerary sculpture, see (Lippolis 1994, pp. 109–28). |

| 73 | Such as on Munich L 345 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 15/76, p. 411), Bari 1009 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 17/12, p. 459), and London, British Museum F 280 (ibid., 23/273, p. 761). |

| 74 | Such offerings of flowers were originally not only expressions of piety, but also a symbol of the beauty of the deceased. See (Lohmann 1979, pp. 119–20) for discussion of flowers mentioned in funerary epigrams. |

| 75 | To support her interpretation, Cabrera points to examples of Eros on Apulian vases where the god holds a flower, sometimes enormous in scale, that he occasionally offers to mortals, such as on Vienna 623 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 20/299, p. 592, pl. 227, 1) and Naples, private coll. 11 (ibid., 19/86, p. 554, pl. 207, 4). |

| 76 | For example, Paestum, Andriuolo necropolis tomb 53 (east slab) and Paestum, Arcioni necropolis tomb 271 (east slab). Spiral tendrils, wreaths, garlands, and palmettes occur in Campanian painted tombs as well. Refer to (Benassai 2001, pp. 26–29, 45–46, 50–54, 71–79, 137–43, 146–51). |

| 77 | Taranto, tomba a camera 16, 4th century B.C. |

| 78 | Taranto inv. 22.437. |

| 79 | See also (Baumann 1993, p. 68). Asphodel’s root systems are not damaged during wildfires, which allows the plant to multiply rapidly in land recently cleared by fire. Various species are indigenous to southern Italy (e.g., asphodelus fistulosis, asphodelus microcarpus and asphodelus albus), but they do not appear to have been painted by Apulian artisans. Refer to (Pignatti 2011, vol. 3, pp. 344–47). |

| 80 | See for example on Ruvo 1372 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 15/36, p. 402), Louvre K 72 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 17/65, p. 469), and Taranto 51381 (ibid., 18/42a, p. 497). On native thistle species of Italy: Pignatti 2011, vol. 3, pp. 143–67. Lohmann suggests that the thistles in Apulian vase-painting might instead be safflower (Carthamus tinctorius), a plant found in many Egyptian tombs that was used for oil and to produce a red dye (Lohmann 1979, p. 121). |

| 81 | E.g., on the lid of the loutrophoros New York 11.210. 3 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1982, 18/20, p. 489) and the neck of the volute kraters Berlin 1984.41 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1991–1992, 18/41b, p. 147). For information on oak species indigenous to southern Italy, see Pignatti 2011, vol. 1, pp. 115–20. |

| 82 | The milk thistle (Silybum marianum), which grows abundantly throughout the Italian peninsula and Sicily, was particularly noted in antiquity for its healing qualities and simulation of lactation. For significance of the oak in ancient Greece: (Jashemski and Meyer 2002, p. 157; Giesecke 2014, pp. 93–95). |

| 83 | The plant was believed to have such miraculous healing properties that the Latin name for the species was salvia, from the Latin “salvere” (to be in good health). |

| 84 | Such as Silene italica (Pignatti 2011, vol. 1, p. 242), Silene vulgaris (ibid., p. 246), Silene latifolia (ibid., p. 252), or Silene dioica (ibid., pp. 252–53). |

| 85 | For example, on Louvre K 35 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 15/11, p. 396, pl. 139, 1); Dublin 1880.1106 (ibid., 15/37, p. 402, pl. 142, 1–2); and once Melbourne, Geddes coll. A 5:11 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1991–1992, 18/334b1, p. 165). |

| 86 | Initially the acanthus was not the primary element of decoration of the anthemion and was overshadowed by the finial palmette. Soon the luxurious foliage began predominate and the leaves were almost cut free from the stone. For the significance of acanthus on grave stelai, refer to Froning 1985. See (Jucker 1961) for the later use of acanthus calyxes in Roman funerary portraits. |

| 87 | E.g., Berlin 2680 (Oakley 2004, p. 123); Athens, National Musem 1380 (ibid., p. 134); and Athens, National Museum 14517 (ibid., p. 183). An acanthus column marking a grave appears on Athens, Kerameikos 1136 (ibid., p. 199). |

| 88 | For discussion of convolvulus in ancient sources: (Jashemski and Meyer 2002, pp. 96, 103). |

| 89 | The trumpet shape of the Calystegia is a bit taller and more pronounced with rounder edges to the petals, although the Convolvulus althaeoides and the Convolvulus elegantissimus also might be plausible identifications (Pignatti 2011, vol. 2, pp. 389–90). |

| 90 | Another close relative to the Calystegia and Convolvulus is the Ipomoea genus, the seeds of several varieties of which, particularly Ipomoea violacea, contain the tryptamine lysergic acid amide (LSA), which has psychedelic and hallucinogenic effects when ingested. The ground seeds are known to have been used for divinatory purposes, particularly in Mesoamerica (Hofmann 1963, 1971; Amor-Prats and Harborne 1993). A member of the same family, Ipomoea sagitta, grows in Apulia, but there is no evidence for it having been used as an ancient narcotic. For the use of hallucinogens in the Classical world, refer to (Camilla and Ruck 2017). |

| 91 | For example, Dianthus balbisii, Dianthus rupicola, Dianthus carthusianorum, and even the distinctive local type, Dianthus tarentinus. |

| 92 | Lohmann also identifies these flowers as poppies (Lohmann 1979, p. 121). On poppies in ancient Greece and Italy: Baumann 1993, p. 72; Jashemski and Meyer 2002, pp. 137–39; Jannot 2009, pp. 84–85; and Fabbri 2017. |

| 93 | Aphrodite also seems to have had a chthonic guise in mainland Greece as well, suggested by the presence of Erotes around a female figure emerging from the ground in anodos scenes painted on Attic vases: Buschor 1937, p. 17; Rumpf 1950–1951, p. 168; Metzger 1951, pp. 72–73; Langlotz 1954, pp. 7–8; and Sgouropoulou 2000. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heuer, K. Tenacious Tendrils: Replicating Nature in South Italian Vase Painting. Arts 2019, 8, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020071

Heuer K. Tenacious Tendrils: Replicating Nature in South Italian Vase Painting. Arts. 2019; 8(2):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020071

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeuer, Keely. 2019. "Tenacious Tendrils: Replicating Nature in South Italian Vase Painting" Arts 8, no. 2: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020071

APA StyleHeuer, K. (2019). Tenacious Tendrils: Replicating Nature in South Italian Vase Painting. Arts, 8(2), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020071