The Girl with the Golden Wreath: Four Perspectives on a Mummy Portrait †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Provenance Research

3. Technical Examination

4. Museum Presentation

5. Diversity Education

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sample Questionnaire

- Can you tell us what you see here? Name five things that you see.

- What would you like to know more about?

- Do you think this is a beautiful portrait? Does it matter?

- Would you say that the proportions, the shapes and forms are realistic?

- Can you tell how it was made?

- Why do you think this portrait was painted, for what purpose?

- Will the painter have known the portrayed subject?

- When would the portrait be painted—and for whom?

- How old do you think the portrait person is? What makes you say that?

- Do you think this person was rich or poor? How can you know?

- How do we treat the dead in our society?

- Have you ever attended a funeral or visited a cemetery?

- Do you know what a mummy is?

- Can you tell us why mummies were made?

- Do you know what life expectancy is, and if so, does it change over time—can you guess what average life expectancy was at the time of this portrait?

- Can you tell where this person is from, what her or his ethnic background was?

- Do you identify yourself by your ethnicity, or by another aspect of your personality?

- Do people always have one single ethnicity, or can it be a mix, a combination?

- Do you think that cultural diversity is a modern phenomenon that did not exist in the past?

- Do you have friends or family to talk about cultural diversity and identity differences?

- Do you have any other questions or thoughts you would like to discuss?

References

- Abungu, George. 2004. The Declaration: A Contested Issue. ICOM News Magazine 57: 5. [Google Scholar]

- Allard Pierson Museum. 1937. Algemeene Gids. Edited by C. W. Lunsingh Scheurleer and E. F. Prins de Jong. Amsterdam: Allard Pierson Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Allard Pierson Museum. 1972. Gods and Men in the Allard Pierson Museum. Alkmaar: Ter Burg. [Google Scholar]

- Arcari, Luca, ed. 2017. Beyond Conflicts: Cultural and Religious Cohabitations in Alexandria and Egypt between the 1st and the 6th Century CE. Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Jan. 2001. The Search for God in Ancient Egypt. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Jan. 2011. Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aufderheide, Arthur C. 2003. The Scientific Study of Mummies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnall, Roger S., and Bruce W. Frier. 1994. The Demography of Roman Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, Mary, John North, and Simon Price. 1998. Religions of Rome. 2 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennecke, Wilhelm, ed. 1904. Hessische Totenschau von 1903. Hessenland: Zeitschrift für die Kulturpflege des Bezirksverbandes Hessen 18: 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bierbrier, Morris L. 2012. Who Was Who in Egyptology, 4th rev. ed. London: Egypt Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Billinge, Rachel, Lorne Campbell, Jill Dunkerton, Susan Foister, Jo Kirby, Jennie Pilc, Ashok Roy, Marika Spring, and Raymond White. 1997. Methods and Materials of Northern European Painting in the National Gallery, 1400–1550. National Gallery Technical Bulletin 18: 6–55. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Graham. 2005. The Engaging Museum: Developing Museums for Visitor Involvement. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, Sarah E. 2017. Whitewashing Ancient Statues: Whiteness, Racism and Color in the Ancient World. Forbes. April 27. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/drsarahbond/2017/04/27/whitewashing-ancient-statues-whiteness-racism-and-color-in-the-ancient-world/#60771bbb75ad (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Bond, Sarah E. 2017. Why We Need to Start Seeing the Classical World in Color. Hyperallergic. June 19. Available online: https://hyperallergic.com/383776/why-we-need-to-start-seeing-the-classical-world-in-color (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Borg, Barbara E. 1996. Mumienporträts: Chronologie, und Kulturelle Kontext. Mainz: Ph. von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, Hugh. 2010. Mystery Cults of the Ancient World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bown, Claire. 2015. Visible Thinking and Interpretation. In Interpreting the Art Museum. Edited by Graeme Farnell. Available online: http://www.visiblethinkingpz.org (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Bremmer, Jan N. 1994. Greek Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buberl, Paul. 1922. Die griechisch-ägyptischen Mumienbildnisse der Sammlung Th. Graf. Vienna: Krystallverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Burkert, Walter. 1985. Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burkert, Walter. 1987. Ancient Mystery Cults. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burlingame, Katherine. 2014. Universal Museums: Cultural and Ethical Implications. In The Right to [World] Heritage, Proceedings of the International Association of World Heritage Professionals Conference, Cottbus, Germany, October 23–25. Edited by Ona Vileikis. Cottbus: International Association of World Heritage Professionals, pp. 384–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cardon, Dominique, Adam Bülow-Jacobsen, Katarzyna Kusyk, Witold Nowik, Renata Marcinowska, and Marek Trojanowicz. 2018. La pourpre en Égypte romaine: Récentes découvertes, implications techniques, économiques et sociales. In Les arts de la couleur en Grèce ancienne … et ailleurs: Approches interdisciplinaires. Edited by Ph. Jockey. BCH Suppl. 56. Athens: École française d’Athènes, pp. 49–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright, Caroline, Lin R. Spaabæk, and Marie Svoboda. 2011. Portrait Mummies from Roman Egypt: Ongoing Collaborative Research on Wood Identification. British Museum Technical Research Bulletin 5: 49–58. Available online: https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/publications/online_journals/technical_research_bulletin/bmtrb_volume_5.aspx (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Challis, Debbie. 2013. The Archaeology of Race: The Eugenic Ideas of Francis Galton and Flinders Petrie. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Charney, Noah, ed. 2019. Context Matters: Collecting the Past. New Haven: Association for Research into Crimes Against Art. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, Helen J., and Leonie Hannan, eds. 2016. Engaging the Senses: Object-Based Learning in Higher Education. London and New York: Routlegde. [Google Scholar]

- Chippindale, Christopher, and David W. J. Gill. 2000. Material Consequences of Contemporary Classical Collecting. American Journal of Archaeology 104: 463–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, Liza, Glenys Davies, and Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones. 2007. Greek and Roman Dress. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, David, and Joop Garssen. 2002. The Netherlands: Paradigm or Exception in Western Europe’s Demography? Demographic Research 7: 433–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, Lorelei H. 1995. Portrait Mummies from Roman Egypt (I–IV Centuries A.D.) with a Catalogue of Portrait Mummies in Egyptian Museums. SAOC 56. Chicago: Oriental Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Cuno, James. 2008. Who Owns Antiquity? Museums and the Battle over our Ancient Heritage. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cuno, James. 2011. Museums Matter: In Praise of the Encyclopedic Museum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, Neil G. W. 2006. Universal Museums, Museum Objects and Repatriation: The Tangled Stories of Things. Museum Management and Curatorship 21: 117–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, Rana. 2018. The Demise of the Nation State. The Guardian. April 5 The Long Read. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/apr/05/demise-of-the-nation-state-rana-dasgupta (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- David, Rosalie. 2002. Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- de Gelder, Laurien, and Stijn Vennik. 2016. Verzamelaars op tafel: De collectiegeschiedenis van het Allard Pierson Museum gepresenteerd. Allard Pierson Mededelingen 113: 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- de Gelder, Laurien, and Vladimir Stissi. 2017. Grieken en Grootmachten: Antieke culturen van 1000 tot 335 voor Christus. Allard Pierson Mededelingen 114/115: 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, John K., Kathryn A. Dooley, Roxanne Radpour, and Ioanna Kakoulli. 2017. Macroscale Multimodal Imaging Reveals Ancient Painting Production Technology and the Vogue in Greco-Roman Egypt. Scientific Reports 7: 15509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doxiadis, Euphrosyne. 1995. Mysterious Fayum Portraits: Faces from Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Eastaugh, Nicholas, Valentine Walsh, Tracey Chaplin, and Ruth Siddall. 2008. Pigment Compendium. A Dictionary and Optical Microscopy of Historical Pigments. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Economou, Maria. 1998. The Evaluation of Museum Multimedia Applications: Lessons from Research. Museum Management and Curatorship 17: 173–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, Campbell C. 1905. On the Dating of the Fayum Portraits. Journal of Hellenic Studies 25: 225–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggebrecht, Arne, ed. 1981. Corpus Antiquitatum Aegyptiacarum. Hildesheim: Gerstenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, Amanda. 2018. Dutch Foreign Minister Says Multicultural Societies Breed Violence. Washington Post. July 18. Available online: https://wapo.st/2Lifcbp?tid=ss_mail&utm_term=.e783b3a53c3a (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Exell, Karen. 2013. Community Consultation and the Redevelopment of Manchester Museum’s Ancient Egypt Galleries. In Museums and Communities: Curators, Collections and Collaboration. Edited by V. Golding and W. Modest. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 130–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fazzini, Richard A. 1995. Presenting Egyptian Objects: Concepts and Approaches. Museum International 47: 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, James D. 2003. Ethnic and Cultural Diversity by Country. Journal of Economic Growth 8: 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, Colleen. 2017. Threats for What She Didn’t Say. Inside Higher Ed. June 19. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/06/19/classicist-finds-herself-target-online-threats-after-article-ancient-statues (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Frankfurter, David. 2000. Religion in Roman Egypt. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, Albrecht. 2010. Deissmann the Philologist. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Goddio, Franck, André Bernand, and Evelyne Jay Guyot de Saint Michel, eds. 1998. Alexandria, the Submerged Royal Quarters. London: Periplus. [Google Scholar]

- Goldziher, Ignác, and Martin Hartmann. 2000. “Machen Sie doch unseren Islam nicht gar zu schlecht”: Der Briefwechsel der Islamwissenschaftler Ignaz Goldziher und Martin Hartmann, 1894–1914. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, Günther. 1974. Die römischen Mumienmasken aus Ägypten. Wiesbaden: F. Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- Hembold-Doyé, Jana, ed. 2017. Aline und Ihre Kinder: Mumien aus dem römerzeitlichen Ägypten. Wiesbaden: Reichert. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, Ian. 2012. Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships Between Humans and Things. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper-Greenhill, Eilean, ed. 2008. The Educational Role of the Museum, 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, Erik. 1999. The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hupperetz, Wim M. H. 2016. Naar een nieuwe collectiepresentatie. Allard Pierson Mededelingen 113: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hupperetz, Wim M. H., Olaf E. Kaper, Frits Naerebout, and Miguel John Versluys, eds. 2014. Keys to Rome. Zwolle: WBooks. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram, Salima, and Aidan Dodson. 1998. The Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, Rosemary A. 2012. From Place to Place: Provenience, Provenance, and Archaeology. In Provenance: An Alternate History of Art. Edited by G. Feigenbaum and I. Reist. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, pp. 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplony-Heckel, Ursula. 2009. Land und Leute am Nil nach demotischen Inschriften, Papyri und Ostraka: Gesammelte Schriften. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Soyeon. 2018. Virtual Exhibitions and Communication Factors. Museum Management and Curatorship 33: 243–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Karen L. 2003. The Gospel of Mary of Magdala. Santa Rosa: Polebridge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Königliche Museen zu Berlin. 1899. Ausführliches Verzeichnis der aegyptischen Altertümer und Gipsabgüsse, 2nd ed. Berlin: Königliche Museen zu Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Geoffrey. 2004. The Universal Museum: A Special Case? ICOM News Magazine 57: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Linscheid, Petra. 2017. Spätantike und Byzanz: Bestandskatalog Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe, Textilien. Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, Claire L. 2016. On Provenance and the Long Lives of Antiquities. International Journal of Cultural Property 23: 245–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, Sally, and Catherine Shaw. 2004. Uncovering Ancient Egypt: The Petrie Museum and Its Public. In Public Archaeology. Edited by N. Merriman. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 109–31. [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, Neil, and et al. 2004. Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums. ICOM News Magazine 57: 4. Available online: http://www.africavenir.org/fileadmin/downloads/Opoku_UniversalMuseum.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Marlowe, Elizabeth. 2016. What We Talk About When We Talk About Provenance: A Response to Chippindale and Gill. International Journal of Cultural Property 23: 217–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlowe, Elizabeth. 2019. The Met’s Antiquated Views of Antiquities Need Updating. Art Newspaper. January 15. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/comment/the-met-s-antiquated-views-of-antiquities-need-updating (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- McManus, Paulette M., ed. 2016. Archaeological Displays and the Public: Museology and Interpretation, 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Merriman, Nick. 2004. Involving the Public in Museum Archaeology. In Public Archaeology. Edited by N. Merriman. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Miliani, Costanza, Alessia Daveri, Lin Spaabaek, Aldo Romani, Valentina Manuali, Antonio Sgamellotti, and Brunetto Giovanni Brunetti. 2010. Bleaching of Red Lake Paints in Encaustic Mummy Portraits. Applied Physics A 100: 703–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moormann, Eric M. 1999. Een elegante dame uit Den Haag. Allard Pierson Mededelingenblad 74: 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, Stephanie, Darren Glazier, James E. Phillips, Lamya Nasser el Nemr, Mohammed Saleh Mousa, Rascha Nasr Aiesh, Susan Richardson, Andrew Conner, and Michael Seymour. 2002. Transforming Archaeology through Practice: Strategies for Collaborative Practice in the Community Archaeology Project at Quseir, Egypt. World Archaeology 34: 220–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas. 2017. ‘Good’ Populism Beat ‘Bad’ in Dutch Election. Guardian. March 19. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/19/dutch-election-rutte-wilders-good-populism-bad- (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- van Epen, Didericus Gijsbertus. 2002. Nederland’s Patriciaat. The Hague: Centraal Bureau voor Genealogie. [Google Scholar]

- Neils, Jenifer, and John H. Oakley, eds. 2003. Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Not, Elena, D. Petrelli, O. Stock, C. Strapparava, and M. Zancanaro. 1997. Person-Oriented Guided Visits in a Physical Museum. In Museum Interactive Multimedia 1997: Cultural Heritage Systems, Design and Interfaces, proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Hypermedia and Interactivity in Museums, Paris, France, 3–5 September 1997. Edited by D. Bearman and J. Trant. Pittsurgh: Archives & Museum Informatics, pp. 162–72. [Google Scholar]

- Parlasca, Klaus. 1966. Mumienporträts und verwandte Denkmäler. Wiesbaden: F. Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- Parlasca, Klaus. 1969–2003. Ritratti di Mummie: Repertorio d’Arte dell’Egitto Greco-Romano. Serie B, 4 vols. Palermo and Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Parlasca, Klaus. 1983. Ein späthellenistisches Steinschälen aus Ägypten. J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 11: 147–52. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, David N. 1994. The Intelligent Eye: Learning to Think by Looking at Art. Los Angeles: Getty Education Institute for the Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1880–1929. Petrie MSS Collection. Oxford: Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, Available online: http://archive.griffith.ox.ac.uk/index.php/petrie-1-7-part-1 (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1889. Hawara, Biahmu, and Arsinoe. London: Field & Tuer. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1911. Roman Portraits and Memphis (IV). London: School of Archaeology in Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit, Emma. 2019. After Racist Incidents Mire a Conference, Classicists Point to Bigger Problems. Chronicle of Higher Education. January 7. Available online: https://www.chronicle.com/article/After-Racist-Incidents-Mire-a/245430 (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Purup, Bjarne. 2019. A Sociolal Approach to Sex and Age Distribution in Mummy Portraits. In Family Lives: Aspects of Life and Death in Ancient Families. ActHyp 15. Edited by K. B. Johannsen and J. H. Petersen. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, pp. 271–98. [Google Scholar]

- Quenouille, Nadine, ed. 2015. Von der Pharaonenzeit bis zur Spätantike: Kulturelle Vielfalt im Fayum, Akten der 5. Internationalen Fayum-Konferenz, 29. Mai bis 1. Juni 2013, Leipzig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Ramer, Brian. 1979. The Technology, Examination and Conservation of the Fayum Portraits in the Petrie Museum. Studies in Conservation 24: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rausch, Muriel, ed. 1998. La gloire d’Alexandrie. Mus. Petit Palais exh. cat. Paris: Paris musées. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, Maarten J., and Wybren K. Taconis. 2005. Egyptian Mummies: Radiological Atlas of the Collections in the National Museum of Antiquities at Leiden. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs, Christina. 2006. The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Jennifer. 2018. The APPEAR Project: Sharing Secrets of Ancient Funerary Portraits. Getty Magazine. pp. 14–19. Available online: http://www.getty.edu/about/whatwedo/getty_magazine/index.html (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Rohrbach, Paul. 1901. In Persien. Preußische Jahrbücher 106: 131–60. [Google Scholar]

- Rondot, Vincent, de Marie-Pierre Chaufray, Ivan Guermeur, and Sandra Lippert, eds. 2018. Le Fayoum: Archéologie, histoire, religion; actes du sixième colloque international, Montpellier, 26–28 Oct. 2016. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Rüpke, Jörg. 2016. On Roman Religion: Lived Religion and the Individual in Ancient Rome. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salvant, Johanna, J. Williams, M. Ganio, F. Casadio, C. Daher, K. Sutherland, L. Monico, F. Vanmeert, S. De Meyer, K. Janssens, and et al. 2017. A Roman Egyptian Painting Workshop: Technical Investigation of the Portraits from Tebtunis, Egypt. Archaeometry 60: 815–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkes, Hans-Martin. 2012. Der Same Seths: Hans-Martin Schenkes Kleine Schriften zu Gnosis, Koptologie und Neuem Testament. Edited by Gesine Schenke Robinson, Gesa Schenke and Uwe-Karsten Plisch. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Schep, Mark, and Pauline Kintz, eds. 2017. Guiding Is a Profession: The Museum Guide in Art and History Museums. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum. [Google Scholar]

- Scheurleer, Constant W. Lunsingh. 1909. Catalogus eener verzameling Egyptische, Grieksche, Romeinsche en andere oudheden. The Hague: Nijgh & Van Ditman. [Google Scholar]

- Scheurleer, Robert A. Lunsingh. 2009. Toekomst voor het Verleden: 75 jaar Allard Pierson Museum, archaeologisch museum van de Universiteit van Amsterdam, 1934–2009. Zwolle: Waanders. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Carl. 1896. Ein vorirenaeisches gnostisches Originalwerk in koptischer Sprache. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin 1896: 839–46. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Carl. 1903. Die alten Petrusakten im Zusammenhang der apokryphen Apostellitteratur nebst einem neuentdeckten Fragment. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs. [Google Scholar]

- Scholten, Peter. 2013. The Dutch Multicultural Myth. In Challenging Multiculturalism: European Models of Diversity. Edited by R. Taras. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 97–119. Available online: www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt20q22fw.11 (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Schürmann, Wolfgang. 1983. Die Reliefs aus dem Grab des Pyramidenvorstehers Ii-nefret. Karlsruhe: C. F. Müller. [Google Scholar]

- Seider, Richard. 1964. Aus der Arbeit der Universitätsinstitute: die Universitäts-Papyrussammlung. Heidelberger Jahrbücher 8: 142–203. [Google Scholar]

- Seipel, Wilfried, ed. 1998. Bilder aus dem Wüstensand. Mumienportraits aus dem Ägyptischen Museum. Vienna: Skira. [Google Scholar]

- Sniderman, Paul, and Louk Hagendoorn. 2007. When Ways of Life Collide: Multiculturalism and its Discontents in the Netherlands. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spaabæk, Lin R. 2012. Mummy Portrait Supports. In Conservation of Easel Paintings: Principles and Practice. Edited by J. Hill Stoner and R. Rushfield. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Spier, Jeffrey, Timothy Potts, and Sara E. Cole, eds. 2018. Beyond the Nile: Egypt and the Classical World. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, Rebecca J., Emma Cantisani, L. Cartechini, M. P. Colombini, Celia Duce, J. Dyer, Jacopo La Nasa, A. Lluveras-Tenorio, J. Mazurek, R. Mazzeo, and et al. 2018. Ancient Encaustic: An Experimental Exploration of Technology, Ageing Behaviour and Approaches to Analytical Investigation. Microchemical Journal 138: 472–87. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2018.01.040 (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Stockhammer, Philipp W. 2013. From Hybridity to Entanglement, from Essentialism to Practice. Archaeological Review from Cambridge 28: 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Talbot, Margaret. 2018. The Myth of Whiteness in Classical Sculpture. The New Yorker. October 29. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/10/29/the-myth-of-whiteness-in-classical-sculpture (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- ten Berge, Clara M., and Branko F. van Oppen de Ruiter. 2019. Diversity Education in Museums of Antiquity. Ancient World Magazine. January 25. Available online: https://www.ancientworldmagazine.com/articles/diversity-education-museums-antiquity/ (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Thomas, Thelma K. 2010. From Curiosities to Objects of Art: Modern Reception of Late Antique Egyptian Textiles as Reflected in Dikran Kelekian’s Textile Album of ca. 1910. In Anathemata Eortika: Studies in Honor of Thomas F. Mathews. Edited by J. Alchermes. Mainz: Ph. von Zabern, pp. 300–12. [Google Scholar]

- Trip, Gabriel. 2019. Before Trump, Steve King Set the Agenda for the Wall and Anti-Immigrant Politics. NY Times. January 10. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/10/us/politics/steve-king-trump-immigration-wall.html (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Tully, Gemma. 2011. Re-Presenting Ancient Egypt: Reengaging Communities through Collaborative Archaeological Methodologies for Museum Displays. Archaeological Review from Cambridge 26: 137–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tyldesley, Joyce A. 1999. The Mummy: Unwrap the Ancient Secrets of the Mummies’ Tombs. London: Carlton. [Google Scholar]

- van Beek, René, and Geralda Jurriaans-Helle. 2016. Een overleden dame met een bijzonder kapsel. Allard Pierson Mededelingen 113: 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- van Boekel, Georgette M. E. C. 1987. Roman Terracotta Figurines and Masks from the Netherlands. Groningen: Groningen University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Daal, Jan M., and Branko F. van Oppen de Ruiter. 2018. The Girl with the Golden Wreath. Ancient World Magazine. August 24. Available online: https://www.ancientworldmagazine.com/articles/girl-golden-wreath/ (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- van Dommelen, Peter, and A. Bernard Knapp, eds. 2010. Material Connections in the Ancient Mediterranean: Mobility, Materiality and Identity. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- van Niekerk, L. E. 1985. Kruger se regterhand: ’n Biografie van dr. W. J. Leyds. Pretoria: J. L. van Schaik. [Google Scholar]

- van Oppen de Ruiter, Branko F. 2017. De hellenistische wereld—Van Alexander tot Cleopatra. Allard Pierson Mededelingen 114/115: 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- van Saaze, Vivian. 2013. Installation Art and the Museum: Presentation and Conservation of Changing Artworks. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vandorpe, Katelijn, Willy Clarysse, and Herbert Verreth. 2015. Graeco-Roman Archives from the Fayum. Louvain: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Villing, Alexandra, and Udo Schlotzhauer, eds. 2006. Naukratis: Greek Diversity in Egypt. London: British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Villing, Alexandra, Marianne Bergeron, Giorgos Bourogiannis, Alan Johnston, François Leclère, Aurélia Masson, and Ross Thomas. n.d. Naukratis: Greeks in Egypt; London. Available online: https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_research_catalogues/ng/naukratis_greeks_in_egypt.aspx (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- von Bissing, Friedrich W., C. W. Lunsingh Scheurleer, and E. F. Prins de Jong. 1924. Beknopte gids van de Egyptische en Grieksche verzamelingen. The Hague: Museum Carnegielaan 12. [Google Scholar]

- von Lieven, Alexandra. 2018. Some Observations on Multilingualism in Graeco-Roman Egypt. In Multilingualism, Lingua Franca and Lingua Sacra. Edited by J. Braarvig and M. J. Geller. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, pp. 339–54. Available online: http://www.oapen.org/search?identifier= 1004755 (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Walker, Susan, ed. 2000. Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Susan. 2018. Ancient Faces in a New Light. Keynote lecture presented at the APPEAR (Ancient Panel Paintings: Examination, Analysis and Research) Conference, Getty Villa, Malibu, CA, USA, May 17–18; Available online: http://www.getty.edu/museum/research/appear_project/downloads/appear_abstracts.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2019).

- Wilimowska, Joanna. 2016. Ethnic Diversity in the Ptolemaic Fayum. Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 56: 287–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenawine, Philip. 2013. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zöllner, Michael, Jens Keil, Daniel Pletinckx, and Harald Wüst. 2009. An Augmented Reality Presentation System for Remote Cultural Heritage Sites. In VAST 2009: The 10th International Symposium on Virtual Reality, Archaeology, and Cultural Heritage. Edited by C. Debattista, D. Perlingieri, D. Pitzalis and S. Spina. Aire-la-Ville: Eurographics Association, pp. 112–16. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | |

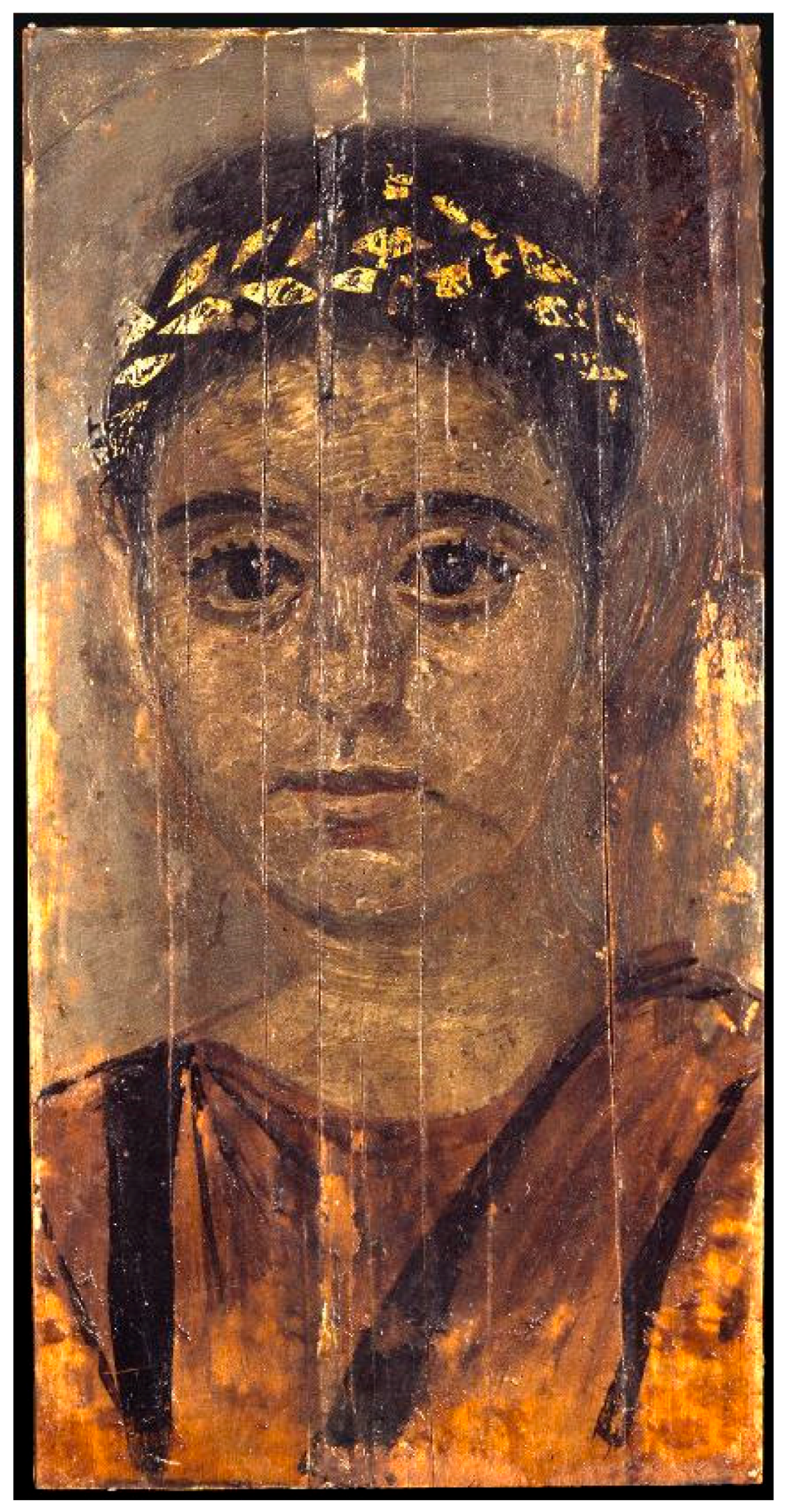

| 2 | APM inv. no. 724; Scheurleer (1909, 64, no. 45, pl. 3, Figure 2); Allard Pierson Museum (1937, 19, no. 111, pl. 11); Parlasca (1966, 213; id. 1969–2003, II: 43, no. 307, pl. 72, Figure 4); Allard Pierson Museum (1972, pl. 29); van Haarlem in Eggebrecht (1981, p. 74); Scheurleer (2009, pp. 66–67); van Oppen in Hupperetz et al. (2014, p. 146). |

| 3 | It should be noted, however, that age is difficult to gauge from ancient portraits, whether painted or sculptural; e.g., see: L. A. Beaumont and J. H. Oakley in Neils and Oakley (2003, pp. 59–84, 163–94); Huppertz in Hembold-Doyé (2017, pp. 33–38, the physical remains of a young girl of no more than seven years old, which was adorned with a mummy mask seemingly depicting a young woman); Purup (2019). |

| 4 | Bagnall and Frier (1994, pp. 75–110); cf. T. Parkin in BMCR 1995.03.20 (for doubts about the accuracy of male life expectancy statistics). |

| 5 | For the history of the APM, e.g., see: Allard Pierson Museum (1937, pp. vii–ix); Scheurleer (2009, pp. 13–14); van Beek and Hupperetz in Hupperetz et al. (2014, pp. 176–80). |

| 6 | For C. W. Lunsingh Scheurleer, esp. see: van Epen (2002, pp. 279–349). |

| 7 | For Museum Carnegielaan, see: Von Bissing et al. (1924). |

| 8 | Most known specimens are collected in Parlasca’s monumental 4-vol. work (1969–2003). |

| 9 | For a map of relevant sites, e.g., see: Walker (2000, p. 8). |

| 10 | cf. Gill, “Looting Matters” available online at https://lootingmatters.blogspot.com. |

| 11 | For Carl (also spelled Karl) Reinhardt, see: Parlasca (1966, pp. 29–30, n. 91); Goldziher and Hartmann (2000, p. 69, n. 3); there is easy ground for confusing this scholar and diplomat with his namesakes: Carl August Reinhardt (1818–1877), an author and artist, as well as Karl Reinhardt (1849–1923) and his son (1886–1958), the former a school reformer in Frankfurt, the latter the famous philologist. |

| 12 | The printed text reads:

|

| 13 | Königliche Museen zu Berlin (1899, p. 352, nos. 10.271 and 272, and pp. 356–57, nos. 13.277 and 278); Parlasca (1966, pp. 29–30, n. 91; id. 1969–2003, nos. 114, 286 and 298). While not mentioned in these references, the date of the acquisition of the two portraits and their provenience from Rubayat would seem to indicate that Reinhardt purchased these specimens directly from Theodor Graf (infra n. 16). |

| 14 | For Coptic textiles from the Kelekian collection, ca. 1910, see: Thomas (2010, esp. pp. 303–6). |

| 15 | For Graf, see: Buberl (1922); Parlasca (1966, pp. 23–29); A. Bernhard-Walcher in Seipel (1998, pp. 27–35); Bierbrier (2012, pp. 219–20; cf. Seider 1964, p. 148) (Reinhardt befriended Graf). |

| 16 | Rohrbach (1901, p. 147): “Dr. Reinhardt besißt von seiner Dienstzeit in Kairo her zwei ägyptische Mumienporträts …, die wenige Museen in Europa zu kaufen in der Lage sein werden” (it seems unlikely that these examples refer tot he portraits that are now in Berlin). |

| 17 | For W. J. Leyds, e.g., see: van Niekerk (1985) (political biography in Afrikaans). |

| 18 | In his journal (29 January–5 February 1888), Petrie (1880–1929) observed that all mummy portraits “should be treated eventually just like any other old pictures; carefully cleaned, & then varnished with the best copal varnish” (Petrie MSS Collection, Journals 1.7, VII: p. 34); available online at http://archive.griffith.ox.ac.uk/index.php/petrie-1-7-part-1. |

| 19 | For the Getty APPEAR Project, see: Roberts (2018); cf. http://www.getty.edu/museum/research/appear_project. |

| 20 | Indeed, the desire to reduce the amount of object information on museum labels, in preference for descriptive texts, is a general trend aiming to address aspects of interpretation and significance. |

| 21 | The portrait’s information in the museum’s collection catalogue is available online at http://dpc.uba.uva.nl/archeologischecollectie/record/APM00724 (in Dutch). |

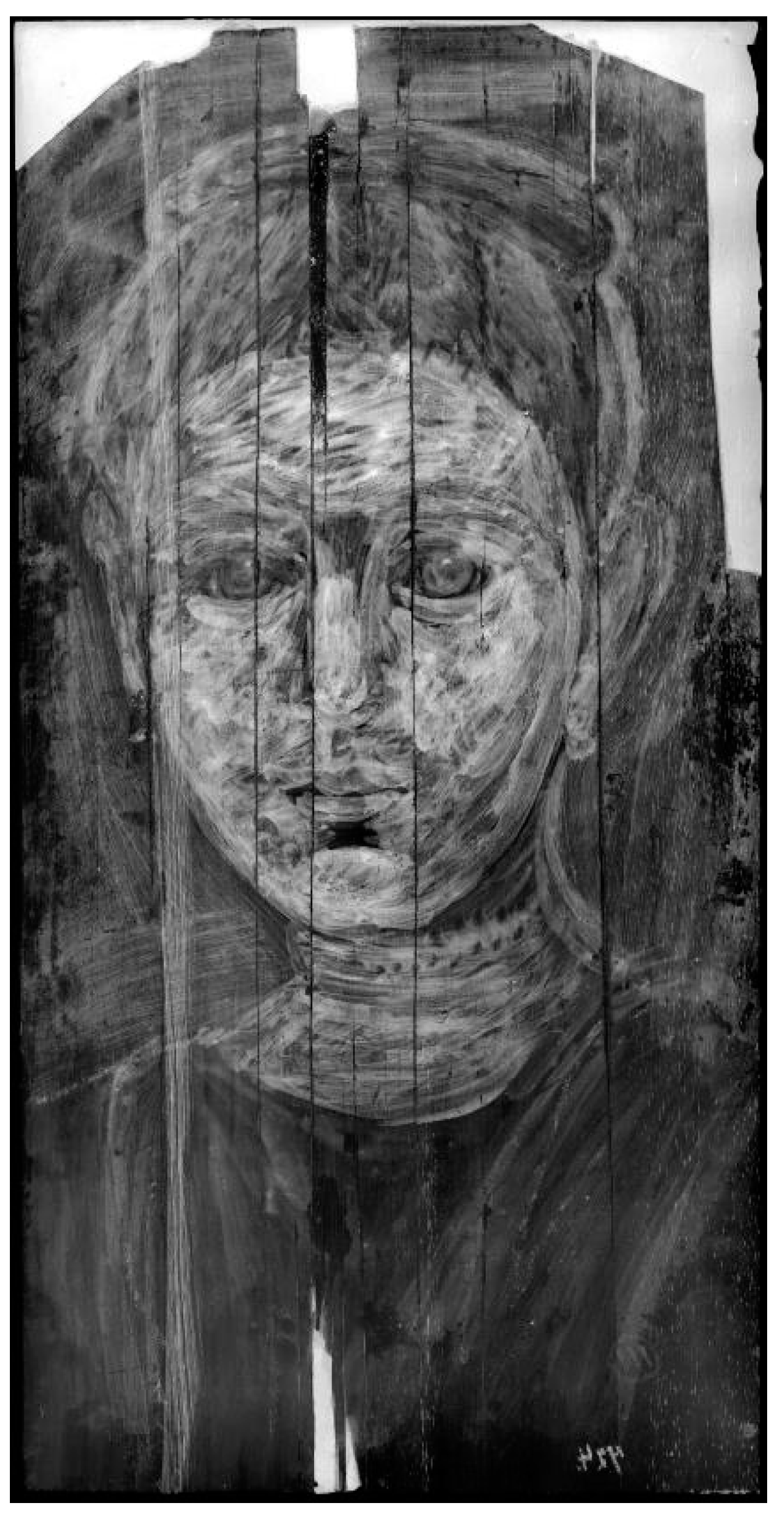

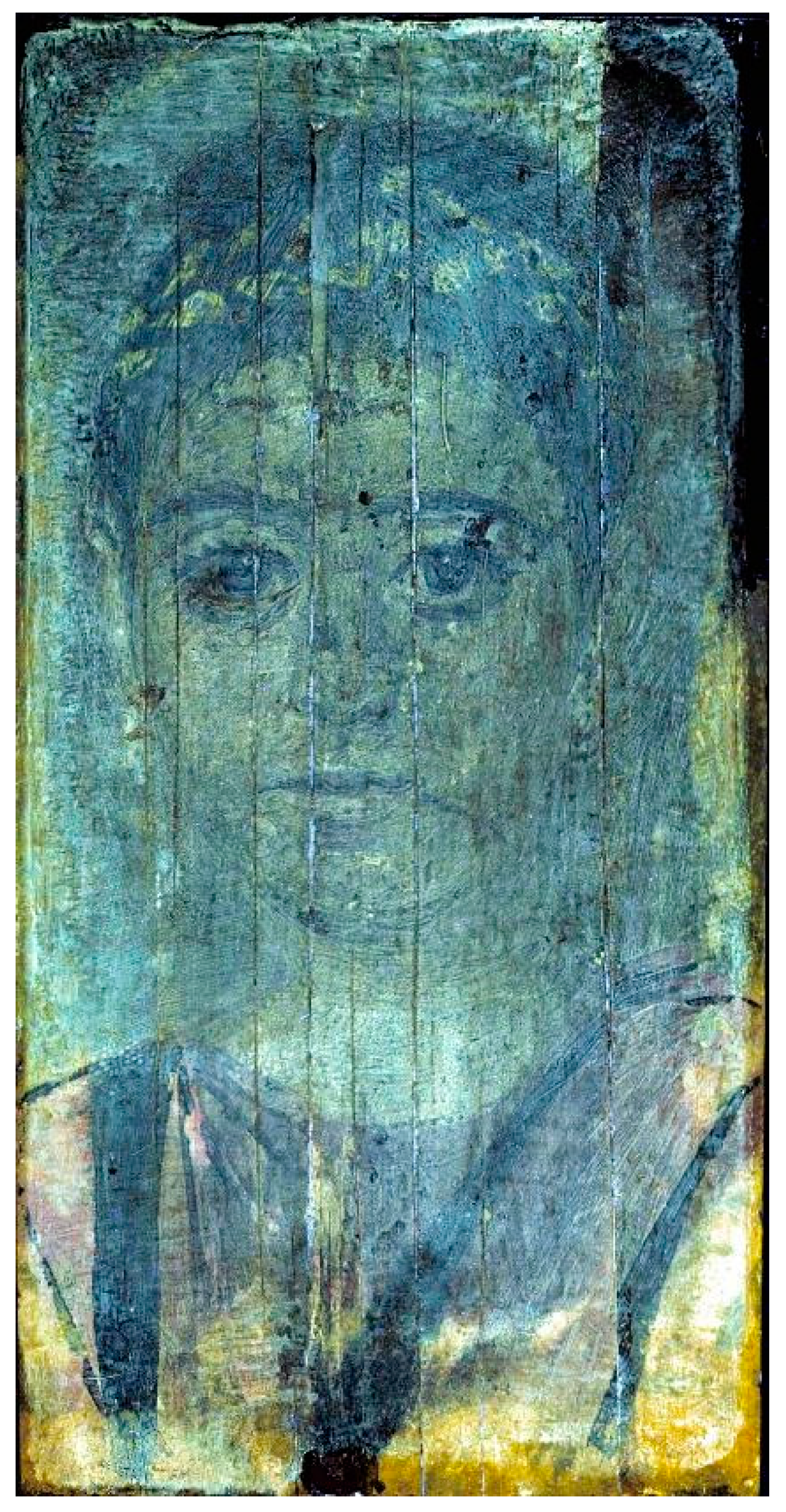

| 22 | The following is a partial revision of Jan M. van Daal, “Re-Viewing Amsterdam’s Ancient Faces: Technical Examination of Two Fayum Portraits from the Allard Pierson Museum” (unpub. MA research paper; UvA 2018); cf. van Daal and van Oppen (2018). |

| 23 | XRF measurements were executed by Arie Wallert. |

| 24 | X-ray acquisition provided by Judith van der Brugge-Mulder; IR reflectography by Moorea Hall-Aquitania. |

| 25 | MMA 09.181.6; Parlasca (1969–2003, II: 43–44, no. 308); Doxiadis (1995, p. 153, pl. 97); Borg (1996, p. 192). |

| 26 | Algemeene gids 1937, p. 19. It might also be noted that Scheurleer noted “Hadrianic” in pencil on his inventory card (Figure 19). |

| 27 | Parlasca (1969–2003, no. 308) (ca. 150–190) = MMA inv. no. 09.181.6 (ca. 90–120); Parlasca (1969–2003, no. 309) (ca. 117–138) = MMA inv. no. 09.181.7 (ca. 120–140); Parlasca (1969–2003, no. 311) (ca. 150–190) = MMA inv. no. 09.181.3 (ca. 140–170). Note the differences in dating between Parlasca and the MMA. |

| 28 | Challis (2013, p. 112; cf. Petrie 1911, p. 7); to be sure, some portraits panels were originally framed already in Antiquity, see: Petrie (1889, p. 11, pl. 12) = Parlasca (1969–2003, no. 807) = Walker (2000, pp. 121–22, no. 117 BM, London, reg. no. 1889,1018.1); Parlasca (1969–2003, no. 405) = Walker (2000, pp. 123–24, no. 119) (Getty, Malibu, obj. no. 74.AP.20). |

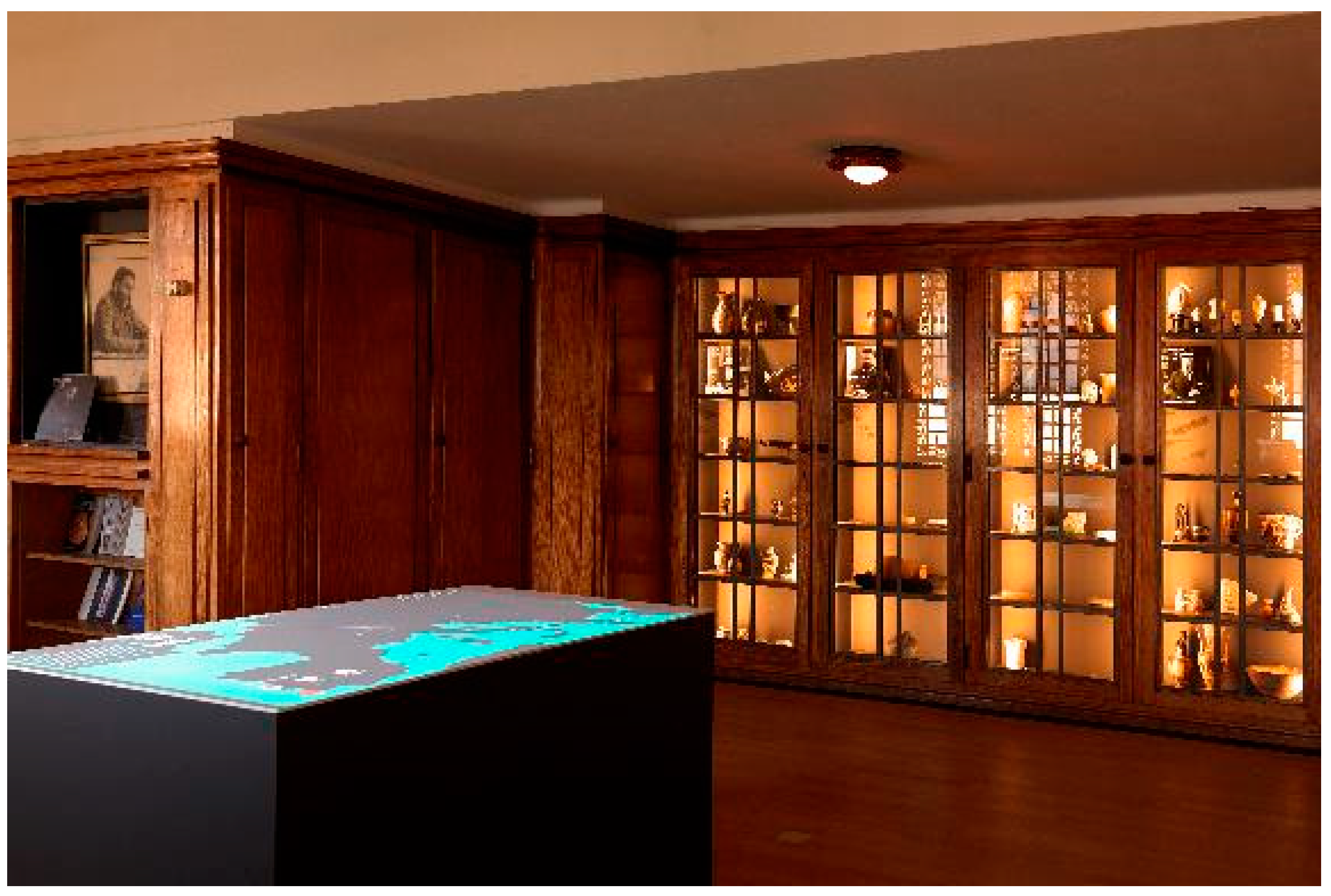

| 29 | Van Beek and Hupperetz in Hupperetz et al. (2014, pp. 180–85). |

| 30 | APM inv. no. 9350; van Beek and van Oppen in Hupperetz et al. (2014, p. 141). |

| 31 | On long-term loan from the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden: RMO inv. no. h 1941/3.7; van Boekel (1987, pp. 469–70); Hupperetz and van Oppen in Hupperetz et al. (2014, p. 152). |

| 32 | APM inv. nos. 14.397–398. |

| 33 | e.g., APM inv. nos. 7001–7004; Hupperetz et al. (2014, p. 145) [BFvOdR]. |

| 34 | |

| 35 | APM inv. no. 17.670; (van Beek and Jurriaans-Helle (2016). |

| 36 | For Egyptian religion, e.g., see: Assmann (2001a); Frankfurter (2000); David (2002); for Greek religion, e.g., see: Burkert (1985); Bremmer (1994); for Roman religion, e.g., see: Beard et al. (1998); Rüpke (2016); for Egyptian funerary traditions in Graeco-Roman times, also see: Riggs (2006); for ancient cultural and material entanglements, e.g., see: van Dommelen and Knapp (2010); Hodder (2012); Stockhammer (2013); cf. online at https://materialentanglements.org. |

| 37 | For mummification, e.g., see: Ikram and Dodson (1998); Tyldesley (1999); Aufderheide (2003); Raven and Taconis (2005). |

| 38 | |

| 39 | For the use and symbolism of funerary wreaths, e.g., see: Corcoran (1995, pass.); Riggs (2006, pp. 81–82). |

| 40 | |

| 41 | |

| 42 | Supra n. 1 (for Romano-Egyptian mummy portraits). |

| 43 | Walker (2018), (abstract) available online at http://www.getty.edu/museum/research/appear_project/downloads/appear_abstracts.pdf. |

| 44 | |

| 45 | For Naucratis, e.g., see: Villing and Schlotzhauer (2006); Colburn in Spier et al. (2018, pp. 82–88); cf. Villing et al. (n.d.) online at ttps://www.britishmuseum.org/research/online_research_catalogues/ng/naukratis_ greeks_in_egypt.aspx. |

| 46 | For Alexandria, e.g., see: Rausch (1998); Goddio et al. (1998); Arcari 2017; Landvatter in (Spier et al. 2018, pp. 128–34). |

| 47 | For the Fayum Oasis, e.g., see: Quenouille (2015); Vandorpe et al. (2015); Wilimowska (2016); Rondot et al. (2018). |

| 48 | For clavi and Roman-Egyptian clothing, e.g., see: Walker (2000, p. 16); Cleland et al. (2007, p. 35); Cardon et al. (2018). |

| 49 | |

| 50 | The following is a partial summary of Clara M. ten Berge, “Interculturele sensitiviteit in het basisonderwijs door middel van Oudheidkundige musea: een casestudie bij groep 7 van de Fiep Westendorpschool in Amsterdam en het Allard Pierson Museum” (unpub. BA thesis; Reinwardt Academy 2019); cf. ten Berge and van Oppen (2019). |

| 51 | For cultural diversity in The Netherlands, e.g., see: Coleman and Garssen (2002); Fearon (2003); Sniderman and Hagendoorn (2007). |

| 52 | |

| 53 | Supra n. 5 (for the history of the APM). |

| 54 | |

| 55 | Supra n. 29 (for the renewal of the Roman gallery); cf. de Gelder and Stissi (2017) (for the “Greeks and Great Powers” gallery); (van Oppen 2017) (for the Hellenistic gallery, “From Alexander to Cleopatra”). |

| 56 | Supra n. 49; also, see: Not et al. (1997); Exell (2013); Chatterjee and Hannan (2016); McManus (2016). |

| 57 | |

| 58 | For a general introduction about arts and museum education, e.g., see: (Perkins 1994; Black 2005; Hooper-Greenhill 2008; Schep and Kintz 2017; cf. Marlowe 2019). |

| 59 | |

| 60 | |

| 61 | For sample questions, see the Appendix A. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barr, J.; ten Berge, C.M.; van Daal, J.M.; van Oppen de Ruiter, B.F. The Girl with the Golden Wreath: Four Perspectives on a Mummy Portrait. Arts 2019, 8, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030092

Barr J, ten Berge CM, van Daal JM, van Oppen de Ruiter BF. The Girl with the Golden Wreath: Four Perspectives on a Mummy Portrait. Arts. 2019; 8(3):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030092

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarr, Judith, Clara M. ten Berge, Jan M. van Daal, and Branko F. van Oppen de Ruiter. 2019. "The Girl with the Golden Wreath: Four Perspectives on a Mummy Portrait" Arts 8, no. 3: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030092

APA StyleBarr, J., ten Berge, C. M., van Daal, J. M., & van Oppen de Ruiter, B. F. (2019). The Girl with the Golden Wreath: Four Perspectives on a Mummy Portrait. Arts, 8(3), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030092