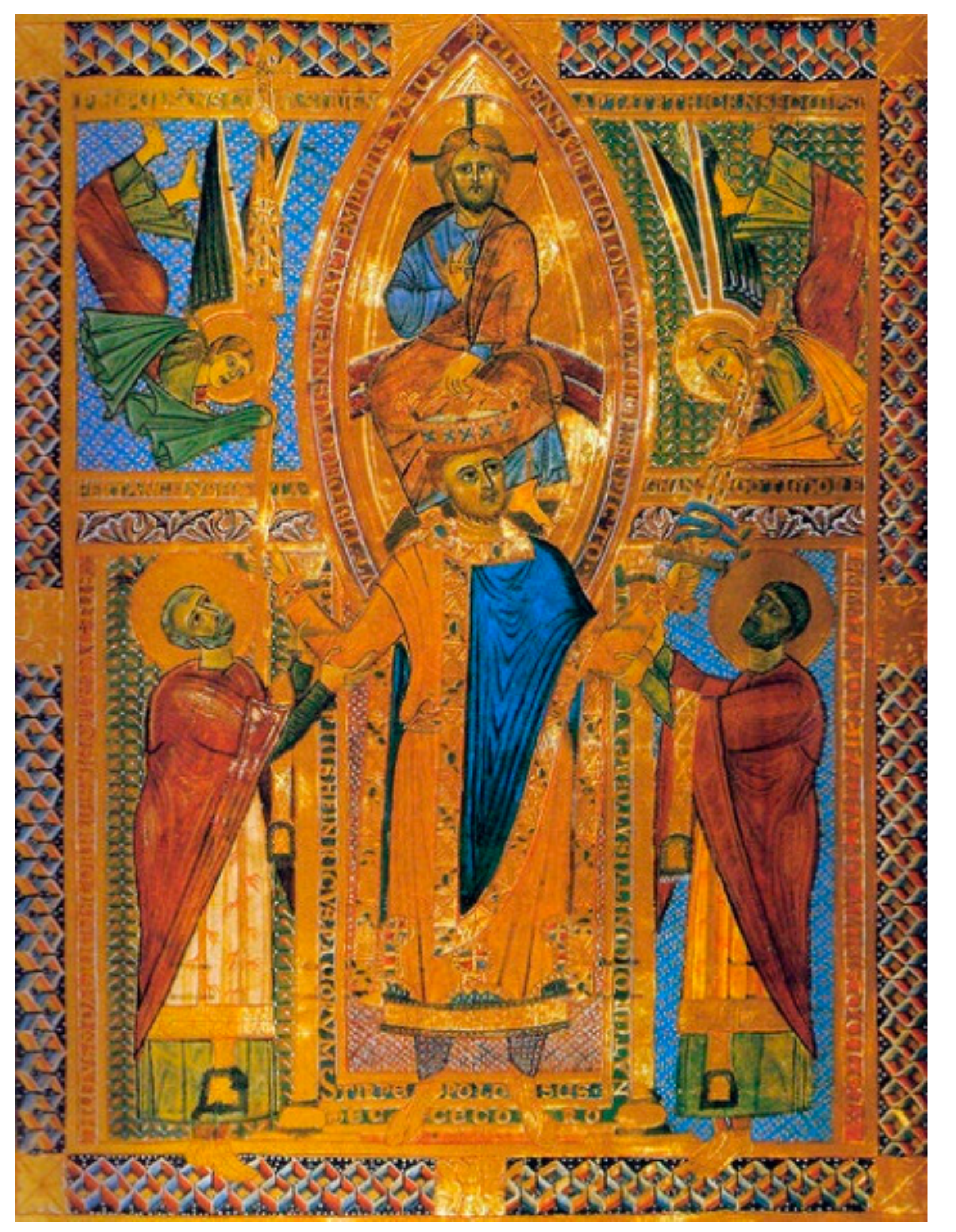

Royal Divine Coronation Iconography. Preliminary Considerations

Abstract

:Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Azmeh, Aziz, and János M. Bak, eds. 2004. Monotheistic Kingship. The Medieval Variants. Budapest: Central European University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alloa, Emmanuel. 2012. Iconic turn. Alcune chiavi di svolta. Lebenswelt. Aesthetics and Philosophy of Experience 2: 144–59. [Google Scholar]

- Andenna, Giancarlo, Laura Gaffuri, and Elisabetta Filippini, eds. 2015. Monasticum Regnum. Religione e Politica Nelle Pratiche di Governo tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna. Münster: Lit. [Google Scholar]

- Areford, David S. 2012. Reception. Studies in Iconography. Special Issue Medieval Art History Today—Critical Terms 33: 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bacci, Michele. 2000. Pro Remedio Animae: Immagini Sacre e Pratiche Devozionali in Italia Centrale (Secoli XIII e XIV). Pisa: Gisem-Edizioni ETS. [Google Scholar]

- Bacci, Michele. 2003. Investimenti per L’aldilà: Arte e Raccomandazione Dell’anima nel Medioevo. Rome and Bari: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Baschet, Jérôme. 1996a. Introduction: l’image-objet. In L’image. Fonctions et Usage Des Images Dans l’Occident Médiéval. Paper Presented at the 6th International Workshop on Medieval Societies, Erice, October 17–23, 1992. Edited by Jérôme Baschet and Jean-Claude Schmitt. Paris: Le Léopard d’Or, pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Baschet, Jérôme. 1996b. Immagine. In Enciclopedia dell’Arte Medievale. Edited by Angela Maria Romanini. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Heinrich, Bonn-Dieter Geuenich, and Heiko Steuer, eds. 2004. Sakralkönigtum. In Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Founded by Johannes Hoops. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, vol. 26, pp. 179–320. [Google Scholar]

- Bedos-Rezak, Brigitte Miriam, and Martha D. Rust. 2018. Faces and Surface of Charisma: An Introductory Essay. In Face of Charisma. Image, Text, Object in Byzantium and the Medieval West. Edited by Brigitte Miriam Bedos-Rezak and Martha D. Rust. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans. 1995. Das Ende der Kunstgeschichte. Eine Revision nach zehn Jahren. Munich: CH Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, Marc. 1924. Les Rois Thaumaturges. Étude sur le Caractère Surnaturel Attribué à la Puissance Royale Particulièrement en France et en Angleterre. Paris and Strasbourg: Librairie Istra. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, Gottfried. 1994. Was ist ein Bild? Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Bredekamp, Horst. 2010. Theorie des Bildakts. Berlin: Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

- Bullough, Donald Auberon. 1991. ‘Imagines Regum’ and Their Significance in the Early Medieval West. Now in IDEM. In Carolingian Renewal. Sources and Heritage. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 39–96. First published 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Cantarella, Glauco Maria. 2002. Le basi concettuali del potere. In Per me Reges Regnant. La Regalità Sacra Nell’europa Medievale. Edited by Franco Cardini and Maria Saltarelli. Rimini and Siena: II Cerchio and Cantagalli, pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Cantarella, Glauco Maria. 2003. Qualche idea sulla sacralità regale alla luce delle recenti ricerche: Itinerari e interrogativi. Studi Medievali s. III 44: 911–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cantarella, Glauco Maria. 2007. Le sacre unzioni regie. In Olio e vino nell’Alto Medioevo, Paper Presented at the 54th Settimane di Studio del Centro Italiano di Studi Sull’alto Medioevo, Spoleto, April 20–26. Spoleto: C.I.S.A.M., pp. 1291–334. [Google Scholar]

- Cardini, Franco. 2002. Introduzione. La regalità sacra: Un tema per il giubileo. In Per me Reges Regnant. La Regalità Sacra nell’Europa Medievale. Edited by Franco Cardini and Maria Saltarelli. Rimini and Siena: Il Cerchio and Cantagalli, pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Castelnuovo, Enrico, and Giuseppe Sergi, eds. 2004. Arti e Storia nel Medioevo, III, Del Vedere. Pubblici, Forme e Funzioni. Turin: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Didi-Huberman, Georges. 1996. Imitation, représentation, fonction. Remarques sur un mythe épistémologique. In L’image. Fonctions et Usage des Images Dans l’Occident Médiéval, Paper Presented at the 6th International Workshop on Medieval Societies, Erice, October, 17–23, 1992. Edited by Jérôme Baschet and Jean-Claude Schmitt. Paris: Le Léopard d’Or, pp. 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dittelbach, Thomas. 2003. Rex Imago Christi: Der Dom von Monreale. Bildsprachen und Zeremoniell in Mosaikkunst und Architektur. Wiesbaden: Reichert. [Google Scholar]

- Engels, Jens Ivo. 1999. Das “Wesen“ der Monarchie? Kritische Anmerkungen zum “Sakralkönigtum“ in der Geschichtswissenschaft. Majestas 7: 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Erkens, Franz-Reiner, ed. 2002. Die Sakralität von Herrschaft: Herrschaftslegitimierung im Wechsel der Zeit und Räume. Fünfzehn interdisziplinäre Beiträge zu einem Weltweiten und Epochenübergreifenden Phänomen. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Erkens, Franz-Reiner. 2003. Vicarius Christi—sacratissimus legislator—Sacra majestas. Religiöse Herrschaftslegitimierung im Mittelalter. Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte 89: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkens, Franz-Reiner. 2006. Herrschersakralität im Mittelalter: Von den Anfängen bis zum Investiturstreit. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Figurski, Paweł, Karolina Mroziewicz, and Aleksander Sroczyński. 2017. Introduction. In Premodern Rulership and Contemporary Political Power. The King’s Body Never Dies. Edited by K.A. Mroziewicz. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Figurski, P. Paweł. 2016. Das sakramentale Herrscherbild in der politischen Kultur des Frühmittelalters. Frühmittelalterliche Studien. Jahrbuch des Instituts für Frühmittelalterforschung der Universität Münster 50: 129–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedberg, David. 1989. The Power of Images. Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaffuri, Laura, and Paola Ventrone, eds. 2014. Images, Cultes, Liturgies: Les Connotations Politiques du Message Religieux. Rome and Paris: École française de Rome and Éditions de la Sorbonne. [Google Scholar]

- Garipzanov, Ildar H. 2004. David, Imperator Augustus, Gratia Dei Rex: Communication and Propaganda in Carolingian Royal Iconography. In Monotheistic Kingship. The Medieval Variants. Edited by Aziz Al-Azmeh and János M. Bak. Budapest: Central European University, pp. 89–118. [Google Scholar]

- Garipzanov, Ildar H. 2008. The Symbolic Language of Authority in the Carolingian World (c. 751–877). Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency. An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Görich, Knut. 2014. BarbarossaBilder—Befunde und Probleme. Eine Einleitung. In BarbarossaBilder. Entstehungskontexte, Erwartungshorizonte, Verwendungszusammenhänge. Edited by Knut Görich and Romedio Schmitz-Esser. Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gugliotta, Maria. 2017. Le sante parole e le buone opere di san Luigi. Joinville (si) racconta. In San Luigi dei Francesi. Storia, Spiritualità, Memoria Nelle Arti e in Letteratura. Edited by Patrizia Sardina. Rome: Carocci Editore, pp. 131–44. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, Montserrat, Jaume Aurell, and Angela C. Miceli Stout. 2016. Political Theology in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Discourses, Rites, and Representations. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, Martin. 2002. Cultural Relativism and the Visual Turn. Journal of Visual Culture 1: 267–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantorowicz, Ernst Hartwig. 1957. The King’s Two Bodies. A Study in Medieval Political Theology. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Körntgen, Ludger. 2001. Königsherrschaft und Gottes Gnade: Zu Kontext und Funktion Sakraler Vorstellungen in Historiographie und Bildzeugnissen der Ottonisch-Frühsalischen Zeit. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Körntgen, Ludger. 2002. König und Priester. Das sakrale Königtum der Ottonen zwischen Herrschaftstheologie, Herrschaftspraxis und Heilssorge. In Die Ottonen. Kunst—Architektur—Geschichte. Edited by Klaus Gereon Beuckers, Johannes Cramer and Michael Imhof. Petersberg: Imhof Verlag, pp. 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Körntgen, Ludger. 2003. Repräsentation—Selbstdarstellung—Herrschaftsrepräsentation. Anmerkungen zur Begrifflichkeit der Frühmittelalterforschung. In Propaganda—Selbstdarstellung—Repräsentation im Römischen Kaiserreich des 1. Jhs. n. Chr. Edited by Gregor Weber and Martin Zimmermann. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, pp. 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Körntgen, Ludger. 2005. Herrschaftslegitimation und Heilserwartung. Ottonische Herrscherbilder im Kontext liturgischer Handschriften. In Memoria. Ricordare e Dimenticare nella Cultura del Medioevo. Edited by Michael Borgolte, Cosimo Damiano Fonseca and Hubert Houben. Bologna: Il Mulino, pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer, Steffen. 2008. Reliquientranslation und königliche Inszenierung: Heinrich III. und die Überführung der Heilig-Blut-Reliquie in die Abteikirche von Westminster. In Bild und Körper im Mittelalter. Edited by Kristin Marek, Raphaèle Preisinger, Marius Rimmele and Katrin Kächer. Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, pp. 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Manganaro, Stefano. 2017. Cristo e gli Ottoni. Una indagine sulle «immagini di autorità e di preghiera», le altre fonti iconografiche, le insegne e le fonti scritte. In Cristo e il potere. Teologia, Antropologia e Politica, Paper Presented at the International Conference, Orvieto, November 10–12, 2016. Edited by Laura Andreani and Agostino Paravicini Bagliani. Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo, pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, Mischa. 2016. Liturgification and Hyper-sacralization: The Declining Importance of Imperial Piety in Constantinople between the 6th and 7th centuries A.D. In The Body of the King. The Staging of the Body of the Institutional Leader from Antiquity to Middle Ages in East and West. Edited by Giovanni-Battista Lanfranchi and Robert Rollinger. Padua: SARGON, pp. 227–46. [Google Scholar]

- Melis, Roberta. 2007. Cristianizzazione, Immagini e Cultura Visiva nell’Occidente Medievale. Available online: http://www.rm.unina.it/repertorio/rm_melis_cultura_visiva.html (accessed on 1 July 2019).

- Mengoni, Angela. 2012. Euristica del senso. Iconic turn e semiotica dell’immagine. Lebenswelt. Aesthetics and Philosophy of Experience 2: 172–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mercuri, Chiara. 2010. La regalità sacra nell’Occidente medievale: Temi e prospettive. In Come l’orco Della Fiaba. Studi per Franco Cardini. Edited by Marina Montesano. Florence: S.I.S.ME.L. Edizioni del Galluzzo, pp. 449–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, William John Thomas. 1994. Picture Theory. Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, Francis Christopher. 2010. Empty Bottles of Gentilism: Kingship and the Divine in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages (to 1050). New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, Francis Christopher. 2012. The Mortgage of the Past: Reshaping the Ancient Political Inheritance. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, Francis Christopher. 2015. The Watershed of Modern Politics: Law, Virtue, Kingship, and Consent (1300–1650). New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oexle, Otto Gerhard. 1984. Memoria und Memorialbild. In Memoria. Der Geschichtliche Zeugniswert des Liturgischen Gedenkens im Mittelalter. Edited by Karl Schmid and Joachim Wollasch. Munich: Fink Verlag, pp. 384–440. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1939. Studies in Iconology. Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paravicini Bagliani, Agostino. 1998. Le Chiavi e la Tiara. Immagini e Simboli del Papato Medievale. Rome: Viella. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzinato, Riccardo. 2018. Vision and Christomimesis in the Ruler Portrait of the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram. Gesta. International Center of Medieval Art 57: 145–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffing, Kai. 2016. The Body(-ies) of the Roman Emperor. In The Body of the King. The Staging of the Body of the Institutional Leader from Antiquity to Middle Ages in East and West. Edited by Giovanni-Battista Lanfranchi and Robert Rollinger. Padua: SARGON, pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Sand, Alexa. 2012. Visuality. Studies in Iconography. Special Issue Medieval Art History Today—Critical Terms 33: 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Jean-Claude. 2002. L’historien et les images. Now in IDEM. In Le Corps des Images. Essai sur la Culture Visuelle au Moyen Âge. Paris: Gallimard, pp. 35–62. First published 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schramm, Percy Ernst. 1928. Die deutschen Kaiser und Könige in Bildern ihrer Zeit. Bis zur Mitte 12. Jahrhunderts (751–1152). Leipzig and Berlin: Teubner. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano Coll, Marta. 2016. Rex et Sacerdos: A Veiled Ideal of Kingship? Representing Priestly Kings in Medieval Iberia. In Political Theology in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Discourses, Rites, and Representations. Edited by Montserrat Herrero, Jaume Aurell and Angela C. Miceli Stout. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 337–62. [Google Scholar]

- Torp, Hjalmar. 2005. Politica, ideologia e arte intorno a re Ruggero II. In Medioevo: Immagini e ideologia. Paper Presented at the International Conference, Parma, September 23rd–27th, 2002. Edited by Arturo Carlo Quintavalle. Milan: Mondadori Electa, pp. 448–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vagnoni, Mirko. 2017a. Dei Gratia Rex Sicilie. Scene D’incoronazione Divina Nell’iconografia regia Normanna. Naples: FedOA-Federico II University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vagnoni, Mirko. 2017b. Cristo nelle raffigurazioni dei re normanni di Sicilia (1130–1189). In Cristo e il potere, dal Medioevo all’Età Moderna. Teologia, Antropologia e Politica. Paper Presented at the International Conference, Orvieto, November 10th–12th, 2016. Edited by Laura Andreani and Agostino Paravicini Bagliani. Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo, pp. 91–110. [Google Scholar]

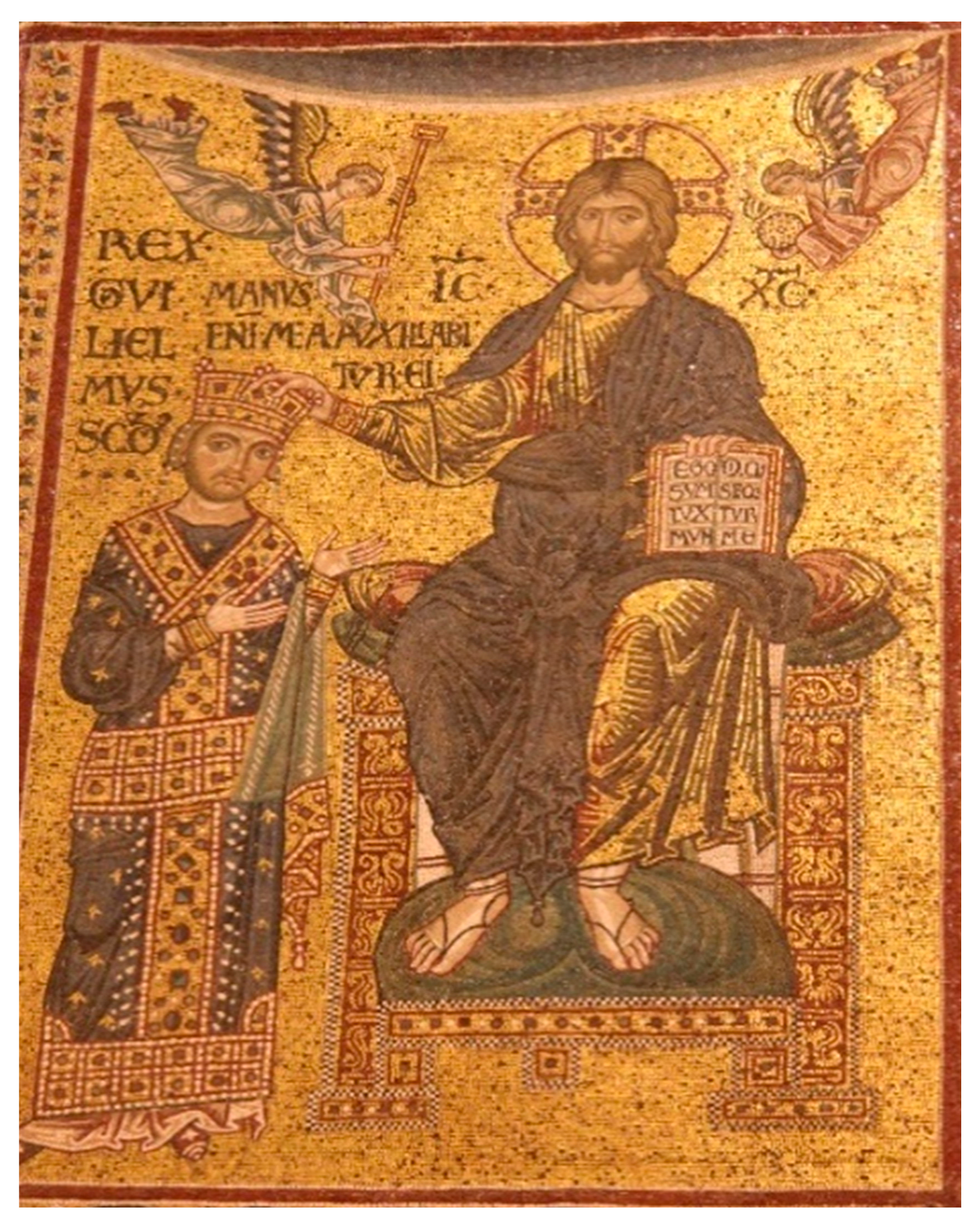

- Vagnoni, Mirko. 2019. Meanings and Functions of Norman Royal Portrait in the Religious and Liturgical Context: The Mosaic of the Cathedral of Monreale. Iconographica. Studies in the History of Images 18: 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Wolfgang Eric. 2010. Die liturgische Gegenwart des Abwesenden Königs: Gebetsverbrüderung und Herrscherbild im Frühen Mittelalter. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Warburg, Aby. 1922. Italienische Kunst und internationale Astrologie im Palazzo Schifanoja zu Ferrara. In L’Italia e l’arte straniera. Paper presented at the 10th International Conference of Art History, Rome, 1912. Edited by Adolfo Venturi. Rome: Maglione & Strini, pp. 179–93. [Google Scholar]

- Weigert, Laura. 2012. Performance. Studies in Iconography. Special Issue Medieval Art History Today—Critical Terms 33: 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Weinfurter, Stefan. 1992. Idee und Funktion des "Sakralkönigtums" bei den ottonischen und salischen Herrschern (10. Und 11. Jahrhundert). In Legitimation und Funktion des Herrschers. Vom ägyptischen Pharao zum neuzeitlichen Diktator. Edited by Rolf Grundlach and Hermann Weber. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Weinfurter, Stefan. 1995. Sakralkönigtum und Herrschaftsbegründung um die Jahrtausendwende. Die Kaiser Otto III. und Heinrich II. in Ihren Bildern. In Bilder Erzählen Geschichte. Edited by Helmut Altrichter. Freiburg im Breisgau: Rombach, pp. 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wollasch, Joachim. 1984. Kaiser und Könige als Brüder der Mönche. Zum Herrscherbild in liturgischen Handschriften des 9. bis 11. Jahrhunderts. Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters 40: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zanker, Paul. 1987. Augustus und die Macht der Bilder. Munich: CH Beck. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | “Il Sole 24 ORE”, 19 May 2019. |

| 2 | (Gaffuri and Ventrone 2014; Andenna et al. 2015; Herrero et al. 2016; Figurski et al. 2017). On pietas as a main element of Augustan propaganda (as well as of the Byzantine emperors and Norman kings of Sicily) see for example: (Zanker 1987; Torp 2005; Meier 2016; Ruffing 2016). |

| 3 | Consider, for example, that in a moral pamphlet written by the King of France Louis IX (1214–1270), for his son, the future Philip III (1245–1285), faith is afforded prime importance: (Gugliotta 2017). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | (Bloch 1924). |

| 6 | (Schramm 1928). |

| 7 | |

| 8 | (Weinfurter 1992, 1995). |

| 9 | (Erkens 2003, 2006). |

| 10 | (Körntgen 2001, 2002). |

| 11 | |

| 12 | For two other recent examples in this direction see: (Krämer 2008; Serrano Coll 2016). |

| 13 | (Schramm 1928). |

| 14 | |

| 15 | (Warburg 1922). |

| 16 | |

| 17 | (Baschet 1996a, 1996b). |

| 18 | On these aspects in general see: (Didi-Huberman 1996; Schmitt [1997] 2002; Castelnuovo and Sergi 2004; Melis 2007). Instead, for some practical examples of depictions of the holder of power see: (Paravicini Bagliani 1998; Dittelbach 2003; Görich 2014). |

| 19 | |

| 20 | (Garipzanov 2004, 2008). |

| 21 | (Oexle 1984). |

| 22 | |

| 23 | (Wagner 2010). |

| 24 | |

| 25 | |

| 26 | |

| 27 | (Sand 2012). |

| 28 | (Areford 2012). |

| 29 | (Weigert 2012). |

| 30 | |

| 31 | |

| 32 | |

| 33 | |

| 34 | |

| 35 | (Bacci 2000, 2003). |

| 36 | (Meier 2016). |

| 37 | (Bloch 1924). And for a more recent analysis see: (Cantarella 2007). |

| 38 | For some criticisms on the concept of sacral kingship see: (Engels 1999). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vagnoni, M. Royal Divine Coronation Iconography. Preliminary Considerations. Arts 2019, 8, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040139

Vagnoni M. Royal Divine Coronation Iconography. Preliminary Considerations. Arts. 2019; 8(4):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040139

Chicago/Turabian StyleVagnoni, Mirko. 2019. "Royal Divine Coronation Iconography. Preliminary Considerations" Arts 8, no. 4: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040139

APA StyleVagnoni, M. (2019). Royal Divine Coronation Iconography. Preliminary Considerations. Arts, 8(4), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8040139