Abstract

The Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB) (est. 1912) is one of the oldest Indigenous rights groups in the United States. Although critics have accused the ANB of endorsing assimilationist policies in its early years, recent scholarship has re-evaluated the strategies of the ANB to advance Tlingit and Haida governance at the same time that they pursued a strategic commitment to the settler state. Contributing to this re-appraisal of the early ANB, this article examines photographic documentation of the use of the American flag in ANB Halls from the period 1914–1945. I argue that the pairing of the American flag with Indigenous imagery in ANB Halls communicated the ANB’s commitment to U.S. citizenship and to Tlingit and Haida sovereignty.

The Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB) is the oldest continuously active Indigenous rights’ organization in the United States.1 Established in 1912 by Tlingit and Tsimshian leaders at a meeting in Juneau, Alaska, and joined by the Alaska Native Sisterhood (ANS) in 1914, the ANB/ANS won an impressive list of battles in their first fifty years alone: U.S. citizenship for Alaska Natives in 1923, one year before Congress granted citizenship to all Native Americans; desegregated schools for mixed-race children in 1929, twenty-five years before Brown vs. Board of Education desegregated public schools in the United States; the first anti-discrimination act in the U.S. in 1945; and, in a lengthy lawsuit that began in 1929 and ended in 1968, the recognition of aboriginal titles in Southeast Alaska, which paved the way for the larger Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971.2

Yet the legacy of the ANB has long been complicated by what critics decried as its assimilationist roots, which appeared to undermine—rather than support—Native rights and sovereignty. Until 1922, the ANB restricted membership to “English-speaking members of the Native residents of the territory of Alaska,” suppressing Indigenous language speakers and siding with the “English-only” policies of many boarding schools.3 The preamble to its earliest Constitution pledged “to assist and encourage the Native in advancement from his native state to his place among the cultivated races of the world,” echoing settler paradigms of the “savage” versus the “civilized.” The ANB also endorsed the Americanization rhetoric of many Progressive-era groups in its newspaper, The Alaska Fisherman, which until 1924 ran on a platform of “One Nation, One Language, One Flag.”4

Recent scholarship has reevaluated the assimilationist overtones of the early ANB, recognizing the difficult path to political authority that Alaska Natives faced in the early twentieth century, and highlighting the ANB’s work to pursue “subtle political strategies aimed at maintaining…cultural differences” (Daley and James 2004, p. 58).5 ANB and ANS members today argue that early leaders championed the “tools we needed to protect ourselves”—English language, knowledge of Western law and property rights, and the ability to perform the codes of “civilization”—so that Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian people could gain access to the political power necessary to fight for their rights within the United States.6 This reassessment of the early ANB joins a wider reevaluation of Indigenous collectives from the Progressive era, particularly the Society of American Indians (est. 1911), which also has been accused of sacrificing Native sovereignty in its pursuit of U.S. citizenship.7 Drawing on Jeffrey Mirel’s concept of the “patriotic pluralism” of early twentieth-century immigrants to the United States, Cristina Stanciu has argued that members of the Society of American Indians (SAI) found ways to maintain “a deep commitment and allegiance to Native nations” at the same time that they pursued a “strategic commitment to the settler nation” (Stanciu 2019, p. 112).8 Stanciu and others have focused on the discursive strategies of Indian Progressive leaders—speeches for non-Native audiences, newspapers edited by Native societies, and collectively-authored resolutions and constitutions—to re-assess the ways in which the SAI and other activist groups authored “Americanization” on Native American terms.9

This article seeks to contribute to the reevaluation of the ANB’s own relationship to Americanization, not through an analysis of their discursive practices, but through their use of symbols—which have long been a strategy of Northwest Coast peoples invested in the public display of crests.10 Specifically, I examine the use of the American flag in ANB halls, the primary gathering site for the ANB and ANS in the twentieth century. At first glance, the prominence of the American flag in the ANB Hall seems to align itself with an assimilationist, “One Nation, One Flag” reading of the ANB, but closer study suggests that the displays were more complicated. In numerous photographs from the 1920s through the 1940s, taken at different ANB halls across Southeast Alaska, an American flag appears on the back wall of the hall, gathered up in the middle so that it drapes like bunting, with a small image or sign pinned between the folds (Figure 1). Although the “gathered” flag in itself is not remarkable—flags were frequently displayed as bunting in the early twentieth century, and the practice was not condemned by the U.S. Flag Code until 194211—the small images pinned beside the flag in the ANB Halls are intriguing, because they depict Indigenous leaders, Tlingit and Haida crests, and other signage of Indigenous governance.

Figure 1.

Wrangell ANB Hall, showing a “gathered” American flag with a small image of Chief Shakes hung between its folds, 3 June 1940. Linn Forrest photograph collection, William L. Paul Sr. Archives, Sealaska Heritage Institute, Juneau, Alaska. Used by permission.

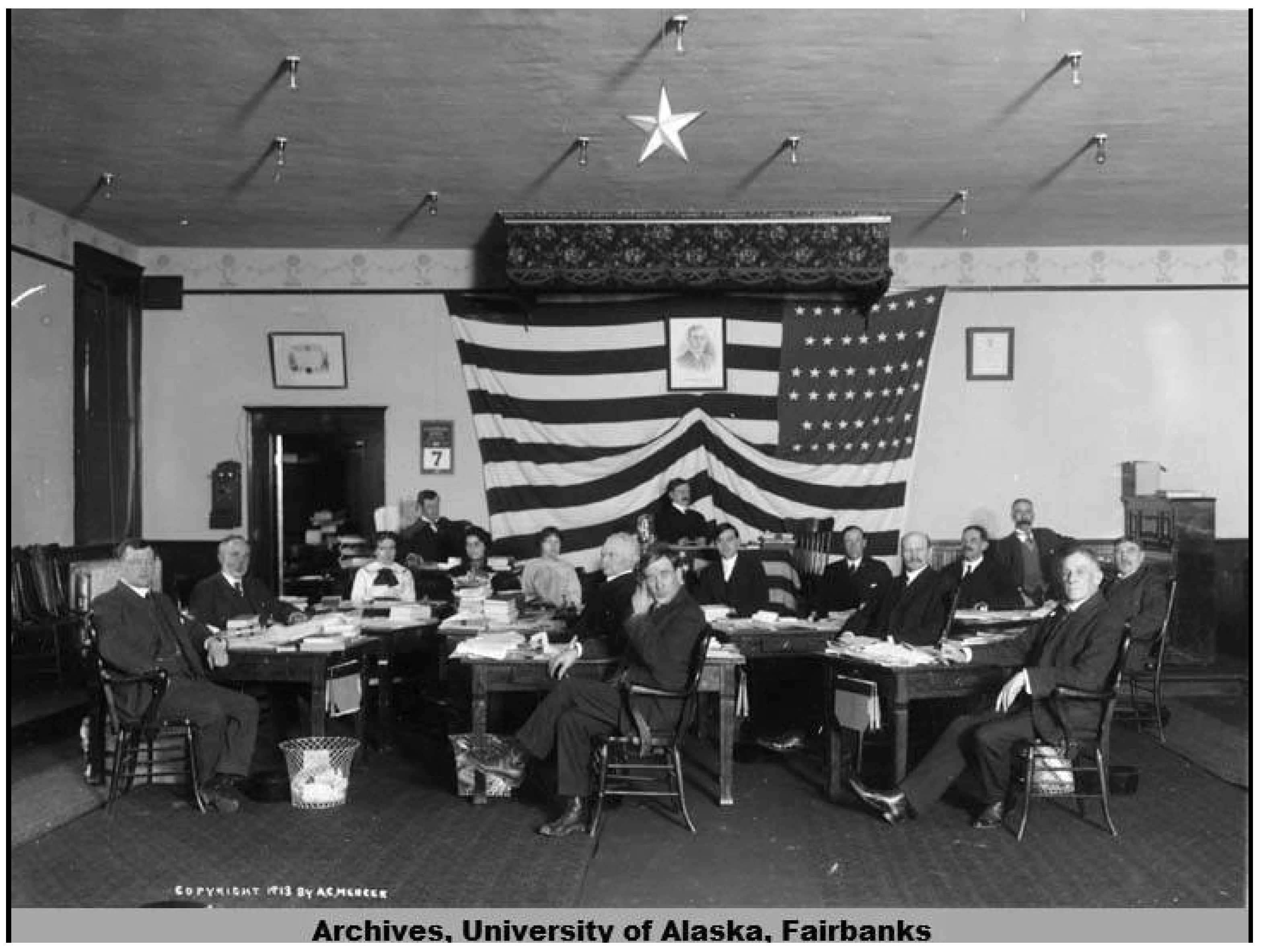

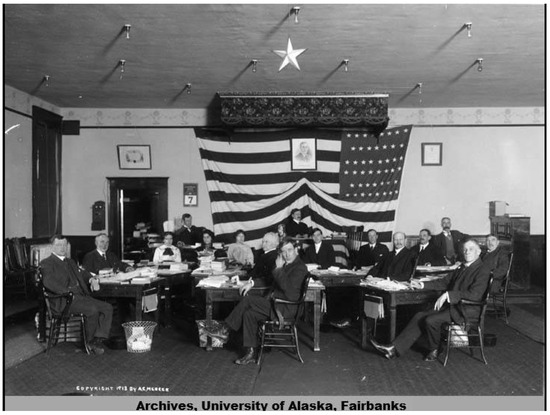

It is difficult today to interpret the meaning of this pairing of Indigenous signage with a “gathered” American flag. Certainly the gathered flag was not a sign of disrespect, for civic organizations across the United States displayed flags as bunting before World War II, often pairing the flag with other patriotic imagery.12 An important example of this display practice appeared in Alaska during the first Territorial Legislature in 1913—just two months after the founding of the ANB—where a framed image of the recently elected president, Woodrow Wilson, hung above the gathered folds of a 46-star flag (Figure 2).13 It is quite possible that the ANB leaders who frequented legislative sessions in Juneau saw this display of a gathered flag and decided to adopt the display practice for their own halls. The model of Alaska’s first territorial legislature would have been of special interest to ANB members fighting for visibility in territorial and federal politics, and several ANB members that I interviewed about the “gathered” American flag in ANB Halls felt that the display was simply fashioned after the territorial legislature.14

Figure 2.

First Territorial Legislature, January 1913, Elks Hall, Juneau, Alaska. UAF-913-51 Charles D. Jones Papers, University of Alaska Fairbanks Archives. Used by permission.

But it is important to note that, with one known exception, ANB Halls did not follow the territorial legislature’s example of displaying an American flag alongside an image of the American president. Instead, the photographs that I have studied in archives, libraries, and private collections show that the ANB and ANS frequently paired a gathered American flag with imagery of Indigenous leaders, or clan crests significant to Indigenous systems of governance. I want to be attentive to this choice, as ANB and ANS leaders were certainly attentive to the symbolism of other displays in their organization, and the flag imagery appeared at the focal point of ANB halls.15 The ANB was the primary liaison between Southeast Alaska’s Native peoples and territorial and federal governments in the early twentieth century, and it remained an important political organization even after the 1939 creation of the federally-recognized tribe, Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska (CCTHIA), which the ANB helped to establish.16 As the primary face of Indigenous governance in Alaska in the first half of the twentieth century, the ANB would have had good reason to pair a gathered American flag with symbols of Indigenous leadership: to represent the organization’s efforts to pursue U.S. citizenship and Indigenous rights, and to portray their members as worthy Americans and as Native people with capable governance structures of their own.

The Alaska Native Brotherhood was officially established on 5 November 1912 by twelve Native men and one Native woman at an education conference in Juneau, Alaska (Dauenhauer and Dauenhauer 1994, pp. 619–95).17 Peter Simpson, a visionary Tsimshian leader who had emigrated in 1887 from British Columbia to Alaska, and who was frustrated that neither Canada nor the United States recognized Indigenous people as citizens who could hold direct title to land, had written letters to Native communities across Southeast Alaska asking if there was interest in discussing their plight at the upcoming Conference of Indians and Teachers of Southeast Alaska, organized by the U.S. Bureau of Education.18 (Not coincidentally, the conference took place at the same time as Alaska’s first election for a territorial legislature—an election in which Indigenous residents, as non-citizens, were not allowed to vote.19) By the end of the conference, thirteen Native people had agreed to form what they called the Alaska Native Brotherhood in order to fight collectively—across their clans and home communities—to advance their cause. All of the founders identified as Christians—the majority were Presbyterian, although three belonged to the Russian Orthodox Church and two to the Salvation Army. Almost all had attended the Sitka Industrial and Training School, a boarding school established by the Presbyterian missionary Sheldon Jackson in the 1880s, which advocated for “the abandonment of tribe and clan, together with the superstition and cumbersome and barbarous traditional laws or customs that cling to them,” in order for Alaska Natives to become U.S. citizens.20

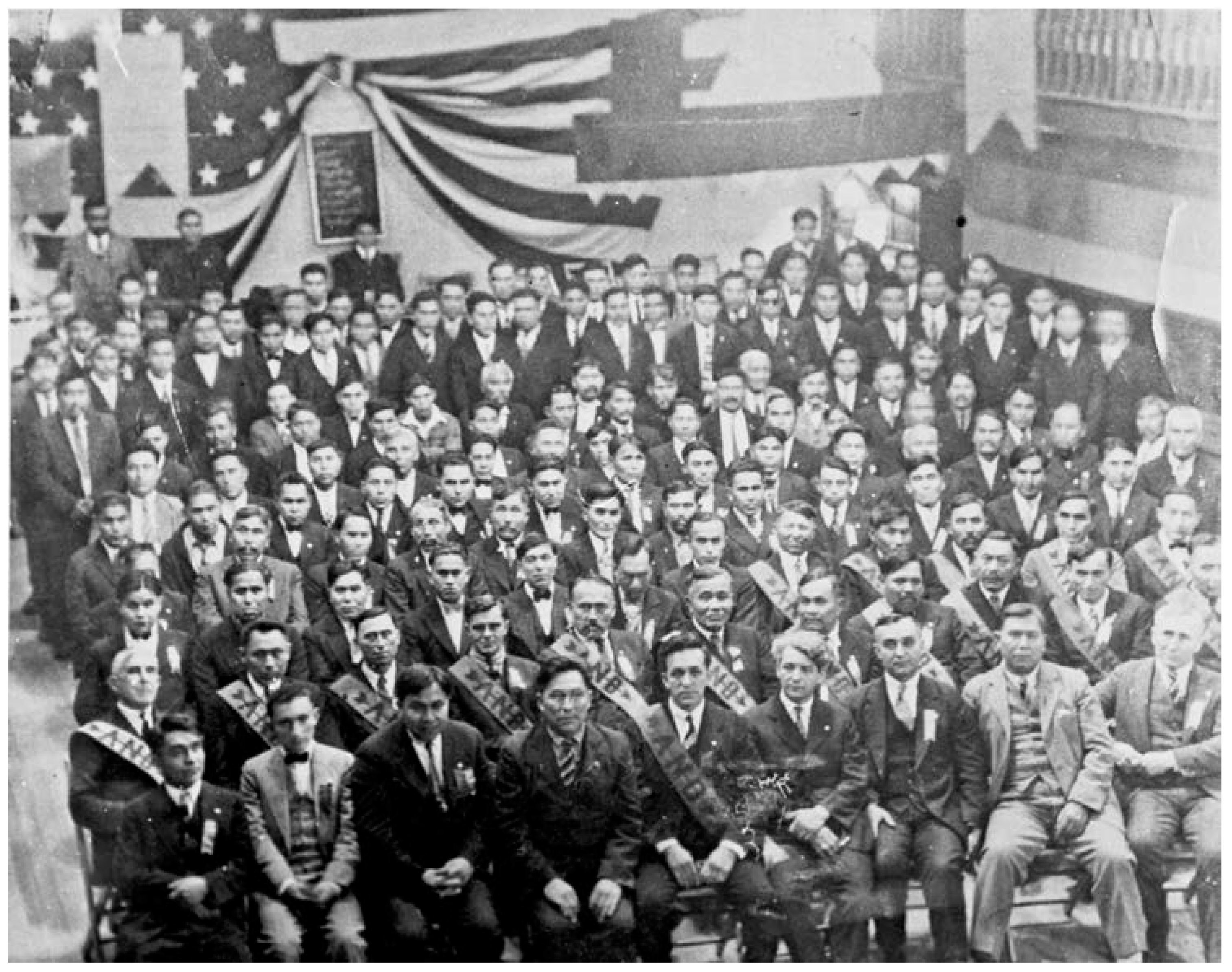

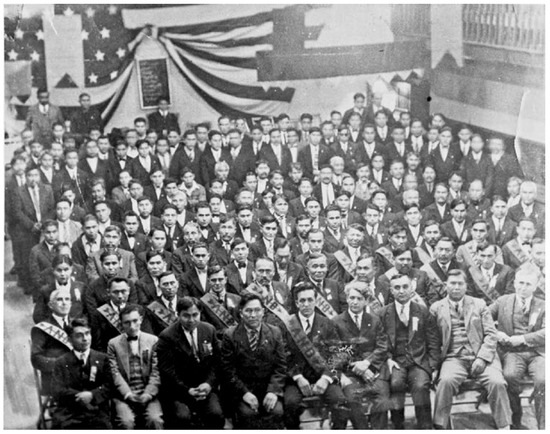

The earliest photograph of the ANB, taken after a lunch break in their meeting on 5 November 1912, does not feature an American flag (nor, for that matter, any kind of symbol, except for the suits and trimmed hair that marked the men as “civilized” in 1912).21 By 1914, however, when ANB members had more time to curate their presentation with a logo, pennants, and the first ANB meeting hall built in Southeast Alaska, the American flag appeared as a prominent symbol that remained in almost every succeeding portrait of the organization (Figure 3). This well-known group photograph of the first Grand Camp Convention—the annual meeting that drew delegates from all ANB camps in Southeast Alaska together, in part to pass resolutions regarding territorial and federal policies that impacted Native people—shows ANB delegates holding banners depicting American flags outside the newly built ANB Hall in Sitka. Men in the front row hold a (moosehide?) banner with the words “Alaska Native Brotherhood” embroidered in calligraphic script over a flag with forty-eight stars (Alaska and Hawai’i would not become states until 1959). In the third row, men on both the left and right hold pennants that depict the American flag on one half and the ANB logo on the other. This logo—the letters “ANB” with an arrow running through them—had been discussed at the founders’ 1912 meeting in Juneau, an index of the ANB’s interest in symbolism from the moment of its founding. The arrow represented the ANB’s work to “go from town to town” and to “never drop to the ground,” connecting Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian clans and communities in a new pan-Indian organization that would work tirelessly to advance the rights of Alaska Native people.22

Figure 3.

ANB Grand Camp Convention in Sitka, November 1914. Photo by Elbridge Merrill. ANB Grand Camp Photo Collection, P0023 Item 2, William L. Paul Sr. Archives, Sealaska Heritage Institute, Juneau, Alaska. Used by permission.

Although the flags in the 1914 photograph were not “gathered up” as they would be in the 1920s, their appearance in the earliest official Grand Camp portrait signaled the importance of the American flag to ANB leaders as a symbol of U.S. citizenship. Citizenship was the primary objective of the ANB before the 1920s; like many Native leaders in the Progressive era, ANB members saw U.S. citizenship as the most promising path for Native people to gain the votes necessary to influence legislation that was favorable to them at the local and national level.23 The ANB mentioned the flag in connection to citizenship in their earliest collective letter, sent to the Commissioner of Education immediately following their 1912 meeting in Juneau. Referencing the fact that the federal government had never signed treaties with Alaska Natives, and therefore left their status vis-à-vis the United States in limbo, the founders wrote:

The founders listed here all the tests of citizenship they had learned in boarding school: English literacy, “civilized customs,” knowledge of U.S. law, and loyalty to the American flag.25It is the paradoxical position of the Alaskan Indian that he is not a citizen nor an alien, nor, like the Plains Indian, a ward of the government…We believe that there is absolutely no reasonable doubt that there are many Indians who by reason of their ability to read and write English, their adoption of civilized customs and manner of their life, their knowledge of and conformity to the government laws, and their manifest loyalty to the flag of the United States, are qualified for American citizenship, and we believe that it is a gross injustice to withhold it from them or to leave them in an indefinite position [my emphasis].24

Loyalty to the flag was a common trope of citizenship in the early twentieth century, as patriotic societies and schools impressed upon immigrants and Native Americans alike the need to cast off former allegiances and show “undivided loyalty” to the settler nation (Maddox 2005, p. 18).26 The Sitka Industrial and Training School, which most ANB founders had attended, followed the model of boarding schools like the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania by rehearsing its students in daily recitations of the pledge of allegiance, patriotic songs, and flag drills on the front lawn (ibid.). Writing in the school’s newspaper, North Star, in 1892, a Sitka school official alluded to the drills that were apparently performed for tourists: “Many of the tourists will remember him [a boy described elsewhere in the article as “a little Eskimo brought down to us from Point Barrow”] as one of the attractions of our Mission: when he appears in the Flag drill as the representative of Alaska, dressed in his reindeer suit, carrying a small American flag as he marches up to the Goddess of Liberty and asks that Alaska may be admitted into the Union.”27 The flag drills at the Alaskan boarding school were thus performances not only of Alaska Native patriotism for the United States, but also of the territory of Alaska’s petition to be admitted as a state—a petition that the ANB also supported, as I will discuss shortly.

Flag drills were especially potent performances in the context of the Northwest Coast, where the stars and stripes of the American flag vied with various crests that had long identified Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian clans. Crests are stylized depictions of animals or other entities that clan ancestors encountered in the distant past and earned the right—often through their own death—to claim as identifying symbols for their clan. Crests are the basis of much northern Northwest Coast art and ceremony, appearing on clothing and jewelry, totem poles and house screens to identify the clan that owns the crests and related prerogatives. Because the clan was the primary political unit on the Northwest Coast, the clan crest was (and remains) a symbol of kinship and allegiance, and American officials were eager to transfer this allegiance to a new “crest” of the United States. In 1899, for example, after a lengthy and bitter dispute over a frog crest claimed by two clans in Sitka, a reporter for The Alaskan wrote that the clans “decided to do away with the Frog, Eagle, Crow and other emblems over which there has been a great deal of discussion and much trouble… and to put up the American flag, obey their countries (sic) laws and do away with clans, natives chiefs and the old customs.”28 Native people quickly learned to appropriate this rhetoric; in 1911, Kaigani Haida residents of the village of Hydaburg signed a petition to President William Taft, promising that “we have given up our old tribal relationships…we have discarded the totem and recognize the stars and stripes as our only emblem.”29 The American flag was thus well-established as a symbol for “civilized” Indians who had pledged allegiance to the United States, and the ANB used it as such to communicate their quest to be recognized as U.S. citizens.

Yet, even as the 1914 group portrait of the ANB harnessed the flag to signify their desired membership in the United States, it is important to remember that the ANB continued to honor the clan relationships that were the basis of Tlingit and Haida governance. The 1914 portrait was taken outside the first ANB Hall in Southeast Alaska, built with money raised by Native families for the ANB to conduct their business and as a community space for Native gatherings. With most halls measuring about 80 × 40 feet, often with a stage at one end and a floor that could double as a basketball court, ANB Halls provided a multi-purpose space for the Native community—including, later in ANB history, space for clans to host traditional ceremonies, like the koo.éex’ or memorial potlatch.30 Significantly, the ANB Hall in Sitka was built on land owned by the prominent Kiks.ádi clan leader K’alyáan, who donated the land to his clansman Paul Liberty, one of the founders of the ANB (Dauenhauer and Dauenhauer 1994, p. 648). This act was important on several fronts: it showed the alliance between “traditional” Tlingit leaders like K’alyáan and “progressive” ANB leaders like Liberty, and it maintained the passage of property within clans. It is also important that Sitka Tlingits built the ANB Hall in the Native village in Sitka, known locally as the “Ranche,” and not across town in the “Cottages” area that was associated with “civilized” graduates of the Sitka Industrial Training School.31 The ANB continued to weave Native protocols into its meetings, consulting local clan leaders in its own camp practices and mastering the parliamentarian procedures (adopted from religious and civic organizations which ANB members had attended) that meshed with Indigenous patterns of ceremonial speech.32 In other words, even as they pursued the outward patterns of U.S. citizenship, ANB members maintained a quiet allegiance to their own clan structures and obligations.

In 1915, partly because of pressure from the ANB, Alaska’s territorial legislature approved a difficult but important pathway to citizenship for Alaska Natives. Applicants for citizenship under the Alaska Native Citizenship Act had to prove their “intelligence of civilization” to White teachers at the local school, sign an oath affirming that they “forever renounce all tribal customs and relationships,” and obtain signatures from five White citizens who could attest that the applicant “has abandoned all tribal customs and relationship and has adopted the ways and habits of a civilized life.”33 The fact that the ANB worked within this framework might be read as a capitulation to settler demands that they renounce their heritage, but it is important to remember that they did so in order to create a Native voting bloc that could support heritage rights (especially the right to access salmon streams and other properties usurped by Whites but historically owned by Tlingit and Haida clans).34 The stated purpose of the ANB’s Citizenship Committee in their 1917 Constitution was to “endeavor to get as many members securing certification [under the 1915 law] allowing them to vote.”35 The resulting Native voting block—derisively called the “canoe vote” by many Whites who feared the growing influence of the ANB—became increasingly powerful in the 1920s, especially after a Tlingit man named Charlie Jones won a 1923 case allowing him to vote in a Wrangell election, despite suspicions that Jones had not renounced “all tribal customs and relationships,” as required under the 1915 law.36

President Coolidge’s signing of the Indian Citizenship Act on 2 June 1924 overrode any appeals that critics might have planned for the 1923 Jones case. Native Americans across the United States were now citizens, and the ANB turned its attention to legislation impacting fisheries, land rights, and education for Native youth. This shift in the ANB’s agenda was reflected in the ANB-sponsored newspaper, The Alaska Fisherman, which changed its official platform nine days before the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act from “One Nation, One Language, One Flag” to “Competent Christian Citizenship.” As the newspaper’s editorials made clear, this phrase meant using one’s citizenship and education to fight “for the little guy” and the “least of these” among Alaska’s people.37 If ANB leaders no longer had to highlight the American flag as a symbol of their allegiance to the United States, however, they continued to display the flag at the center of their meeting halls through the interwar period as they fought for the equal housing, education, and pension benefits available to fellow American citizens.

Scholars trace the ANB’s shifting priorities in the 1920s, from “citizenship-through-assimilation” to building a formidable Native politic bloc aimed at legislating aboriginal rights, to several powerful ANB leaders, particularly Louis and William Paul, Tlingit brothers who returned to Alaska after attending Carlisle Indian School and university.38 William Paul admired the education he had received at Carlisle, recalling how he and his brothers had “learned the fundamentals of our citizenship from that great educator, General R.H. Pratt. The great principle advocated by General Pratt was that Indians should be treated exactly as any other citizen, without special favors beyond a good start in schooling.”39 Paul had earned a law degree, and when he passed the Alaska bar exam in 1921, he became the first Native attorney in Alaska (Metcalfe 2014, p. 20). He put his legal training to use for the ANB, successfully defending Charlie Jones in the 1923 voting case, winning entrance into public schools for mixed-race children in 1929, and starting the ANB newspaper, The Alaska Fisherman, in 1924. Also, in 1924, Paul was elected as the first Alaska Native representative to the Territorial Legislature, where he got a first-hand look at the legislation impacting Native voting rights, fisheries, and education. Although criticized for being a brash and contentious leader who sometimes chastised his own elders, William Paul is also widely credited for his work within the Western legal system to benefit Alaska Native people.40 His brother, Louis, helped temper his brazenness, and restored many customs to ANB Halls, including allowing Tlingit and other Indigenous languages to be spoken in ANB meetings.41

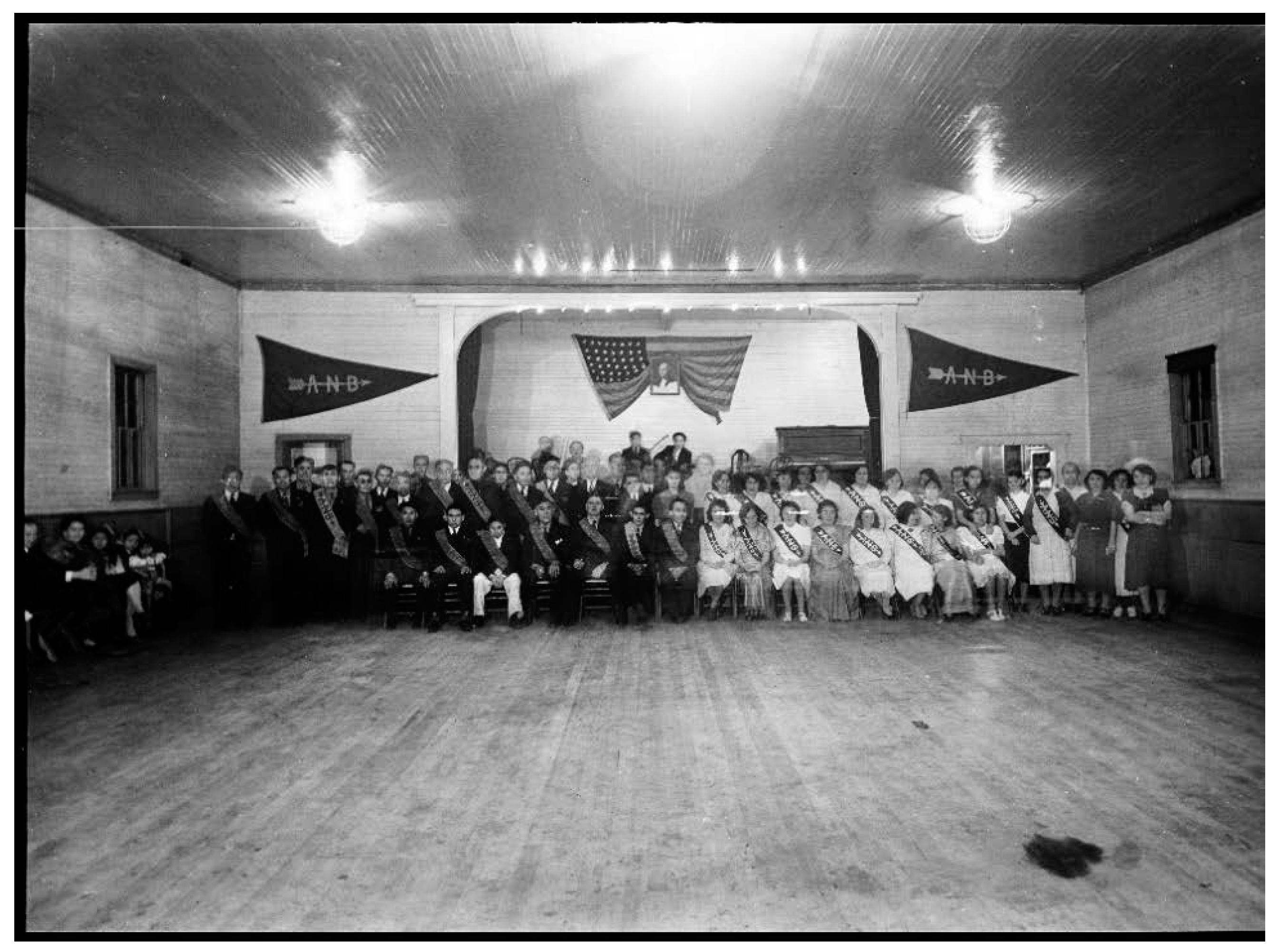

It was during this period of rising self-determination for the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian peoples of Southeast Alaska that the first extant images of the “gathered” American flag appear in ANB Halls. The earliest image I have found of a gathered flag appears in the Haines ANB hall during the historic 1929 Grand Camp Convention, widely considered to be one of the most momentous in ANB history (Figure 4).42 At this Convention, delegates from both the ANB and ANS voted to sue the federal government for the seventeen million acres of their homelands that had been appropriated as the Tongass National Forest in the early twentieth century—without recognition of, or compensation for, Tlingit and Haida claims to those lands (Mitchell 1997, pp. 161–63). In an oft-recited dialogue from an earlier Convention in 1925, Peter Simpson is said to have whispered to William Paul: “Willie, who owns this land?” When Paul answered, “We do,” Simpson responded: “Then fight for it!” (Paul 2007, p. 150). The 1929 Convention began that fight by voting to pursue a lawsuit, Tlingit and Haida Indians of Alaska v. the United States, which resulted in a settlement forty years later (Thornton 1998). Many argue that it was the Alaska Native Brotherhood and Alaska Native Sisterhood’s unflagging work on the lawsuit that established the aboriginal title in Alaska, and that created the legal precedents necessary for the larger Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act to pass in 1971.43

Figure 4.

ANB delegates at the 1929 Grand Camp Convention in Haines. Andrew Hope Collection, courtesy of Peter Metcalfe. Used with permission.

Two group portraits mark the historic 1929 Grand Camp Convention. One depicts delegates from the ANB and ANS together; the other, shown here because it is taken at closer range, portrays only ANB delegates.44 Both portraits were arranged in front of a large American flag draped across the back wall of the ANB Hall, gathered up to the second stripe near the top. On the wall between the flag’s folds appears a small sign or chalkboard with cursive writing across its face. Unfortunately, no amount of magnification has yet deciphered the writing on this sign; it appears to be a list of short words or phrases, perhaps the names of delegates or an outline of the meeting’s agenda. What is clear, however, is that this display established the standard for ANB Halls through the 1930s and 1940s, with an American flag draped on the central back wall of the hall and gathered up to make room for—or to visually center and frame—signage curated by the ANB.

Significantly, the 1929 convention also established one of the most important symbols of the ANB (still in use today): the koogeinaa, or sash, worn diagonally across the chest of several ANB members visible in the photograph. Samuel Jackson, the Vice Chairman of the ANB Executive Committee in 1929, is credited with the idea to create “a banner or Coogaynah, a traditional costume bearing a Tribal or Clan totemic emblem” with the ANB logo replacing the clan crest.45 This was a strategic choice, as anthropologist Thomas Thornton has noted, for the ANB to replace the crests of different Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian lineages with a unifying symbol of its own, and “to bring these groups together under the new pan-Native organization and code for living” (Thornton 2004, pp. 209–10). Women in the Haines camp of the Alaska Native Sisterhood designed the koogeinaa, choosing to honor their community’s unique history of exchange between coastal Tlingits in the United States and inland Tlingits in Canada by using moosehide, a prized trade good from the Interior. As ANB members recalled later of the creation of the koogeinaa, “Suki, an aunt of Mrs. Mildred Sparks and Mrs. Nellie Willard, suggested Moosehide. Their ancestors suffered untold hardship on the Trail from Haines to the Interior during trading ventures [and later as porters for miners traveling the trails during the Klondike Gold Rush].…Hence, the color tan [of the moosehide] also representing gold and many dying in its pursuit, the red symbolizing this loss.”46 The description reveals the ANB and ANS’s continued attention to symbolism, as well as their work to honor Indigenous histories of exchange that predated—and continued in spite of—the borders imposed by the settler nations of Canada and the United States. Displaying this symbol of trans-boundary, collective Indigenous governance at the 1929 Grand Camp Convention asserted Indigenous sovereignty and inaugurated a new display tradition of pairing Indigenous imagery alongside a “gathered” American flag—significantly, at the very moment that the ANB and ANS voted to sue the U.S. government for their land.

Following the 1929 Convention, many group portraits in ANB Halls featured a gathered flag paired with Indigenous imagery. In 1941, in the ANB Hall in Hydaburg, for example, a gathered American flag appeared on the back wall beneath a wooden eagle effigy known as the “Skulka Eagle” after the family who claimed it as their crest, and who had brought it with them to Hydaburg when they left their ancestral village in 1911 (Figure 5). The Skulka Eagle bore a strong resemblance to the bald eagle in the Great Seal of the United States—a fact that federal officials had noted before, and which was, perhaps, the reason the ANB displayed it as a clever visual pun above the American flag.47 Yet the Skulka Eagle was still an Indigenous crest, and its multivalency allowed it to function for more traditional gatherings in the ANB Hall, as well. This particular photograph, for example, was taken during a potlatch-style “party” in 1941, hosted by members of the Eagle moiety in celebration of Eagle-moiety totem poles that had recently been restored in Hydaburg (Moore 2018, pp. 81–82). The fact that all those pictured wore clan regalia—including naaxein or “Chilkat” robes, tunics embroidered with clan crests, and even a feather headdress that had been gifted to a Haida man named Paul Morrison by Plains Indians who admired his tenacity in fighting for Alaska Native lands—affirmed the importance of Native symbols of sovereignty in the ANB Hall.48 For other occasions, like the 1941 Grand Camp Convention held in Hydaburg, the Skulka Eagle appeared more closely aligned with American symbolism, clutching two small American flags in its talons (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

“Party” in the ANB Hall in Hydaburg hosted by Eagle-moiety members, February 1941. US Forest Service Historical Photograph, Craig Ranger District, Craig, Alaska. Image in the public domain.

Figure 6.

ANB/ANS Grand Camp Convention in Hydaburg, 1941. This image appears to have been printed in reverse from its original presentation, probably because of an inverted negative; the Skulka Eagle’s head should point to the right, as in Figure 5. ANB Grand Camp Photo Collection P0064 Item 11, William L. Paul Sr. Archives, Sealaska Heritage Institute, Juneau, Alaska. Used with permission.

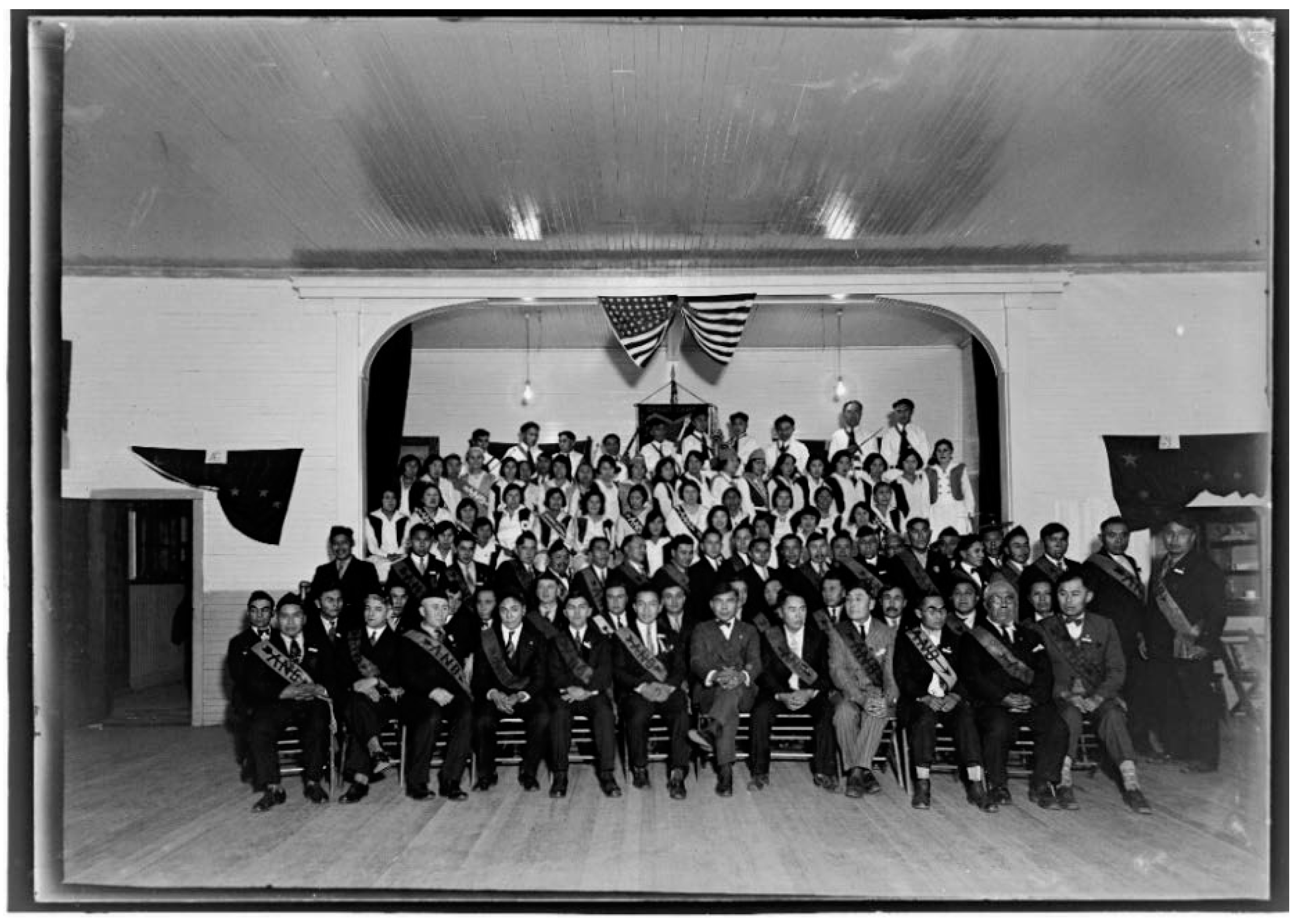

The ANB Hall in the northern Tlingit community of Yakutat also featured a gathered flag with Indigenous imagery—and is the only example I have found of an ANB Hall to feature a flag with an image of an American president. This display was recorded in three photographs in the Yakutat hall, all from about 1933, where an American flag appeared gathered up on the back wall of the stage with a framed image of George Washington between the folds.49 One of these three images depicts a gathering of ANB and ANS members seated in front of the stage, wearing their koogeinaa (Figure 7). The occasion for the photograph is not clear: the 1933 date does not square with the Grand Camp Conventions that were held in Yakutat in 1931 and 1959, and the official portrait of the 1931 Convention did not feature an image of George Washington (see Figure 8). Perhaps the photo was arranged for some local event, rather than a Grand Camp meeting; in any case, it is the only example I know of where an ANB Hall echoed (consciously or not) the Alaska Territorial Legislature’s model of displaying a gathered American flag with an image of an American president.

Figure 7.

ANB/ANS members in Yakutat, n.d. Note the gathered flag with the framed image of George Washington on the back wall of the stage. Alaska State Library Historical Collections, Kayamori photograph ASL-P55-619. Used with permission.

Figure 8.

ANB/ANS Grand Camp Convention in Yakutat, 1931. Fhoki Kayamori photograph, Alaska State Library Historical Collection, P55-032. Used with permission.

Instead, the ANB frequently inserted Indigenous imagery into the space the Territorial Legislature had reserved for the president. In 1931, for example, the ANB Grand Camp Convention in Yakutat showcased a gathered American flag with the official banner of the ANB, which had been newly created the year before (Figure 8). The banner is difficult to see in the group portrait, but other photos from the 1931 Convention clearly show that it was cloth banner with the words “GRAND CAMP” stitched above an Alaskan flag pierced by the ANB-logo arrow, and the words “ALASKA NATIVE BROTHERHOOD” at the bottom of the banner (Figure 9). According to the late Dr. Walter Soboleff, a Tlingit historian and six-time ANB Grand Camp president, this banner had been introduced to the ANB/ANS by the Saxman camp of the Alaska Native Sisterhood at the 1930 Grand Camp Convention.50 The banner became the prototype for ANB/ANS banners used today, and became another example of pairing imagery of ANB leadership with the gathered American flag in the ANB Hall.

Figure 9.

ANB Band at the Grand Camp Convention in Yakutat, 1931. Fhoki Kayamori photograph, Alaska State Library Historical Collection, P55-036. Used with permission.

The 1931 Yakutat photographs are also significant for being the earliest I have found to feature the Alaska flag in the ANB Hall, both as an image on the ANB Banner and as full-sized cloth flags on either side of the banner and stage. Alaska did not have a flag of its own until 1927, when the Alaskan chapter of the American Legion sponsored a contest for Alaskan school children to design one. Benny Benson, a thirteen-year-old Sugpiaq boy living at an orphanage in Seward, won the contest with an elegant design that featured the seven stars of the Ursa Major or “Big Dipper” constellation and the North Star to which it pointed (Swagel 1994). William Paul was the only Native member of the Territorial Legislature in 1927, and he took a special interest in the flag designed by an Alaska Native child; he also supported it as a symbol that could help capture the attention of the federal government in recognizing Alaska’s continuing request for statehood.51 Statehood was an important goal of the ANB, as leaders believed it would transfer control of local resources away from the federal government.52 William Paul railed in The Alaska Fisherman against Whites who were not working as hard as Alaska Natives to have the territory released from federal oversight: “The white citizens of the territory, aside from a few, idle away their efforts in places of congregation and let real Indians organize and protest the enroachments of the Bureau of Fisheries….Alaska would be free in a short time if the white people of Alaska would fight for liberty as hard as the Indians are doing. Quit talking around the poolrooms and make a united protest.”53 Given the fervor with which the ANB supported statehood, it is not surprising that ANB Halls began displaying the Alaskan flag as soon as it was available.

Minutes from the 1927 Grand Camp Convention in Angoon reveal that the ANB was presented with its first Alaskan flag by an official from the Sheldon Jackson school (formerly the Sitka Industrial and Training School) in November 1927, just months after the Alaskan flag had been adopted by the Territorial Legislature in May.54 Apparently, students at Sheldon Jackson had sewn an Alaskan flag for the school’s alumni, who were now leaders of the Alaska Native Brotherhood. It is worth quoting the minutes from this meeting, both to show the careful parliamentarian procedures observed by the ANB and to include one of the few instances where a flag is explicitly discussed in ANB minutes:

Later that week, Angoon school children opened the morning session of the ANB Convention with several flag-related ceremonies: “Flag Salute by the school children of Angoon; America-by the school children; Alaska My Alaska—sung by the school children; There are Many Flags—also by school children.”56 The flag drills of their parents’ boarding school days had now been expanded to include the Alaskan flag, and the reference to “many flags” may have recognized other sovereignties as well.14 November 1927First day: 10 am sessionSong—AmericaScripture ReadingOnward Christian SoldiersPresentation of Alaska Flag by Mr. W.J. Yaw of the Sheldon Jackson School.Remarks by Wm. L. Paul, who explains the history of the Flag presented to the Conventionby Mr. Yaw.Louis F. Paul makes motion that a vote of thanks be extended to the pupils of the Sheldon Jackson School who made the Flag for us, seconded by Sam Jackson; Motion Carried.Louis F. Paul also moves that a letter be sent to Benny Benson, a letter of appreciation for his success in the large competition that he had in this great honor. Seconded by Sam Jackson. Motion carried.55

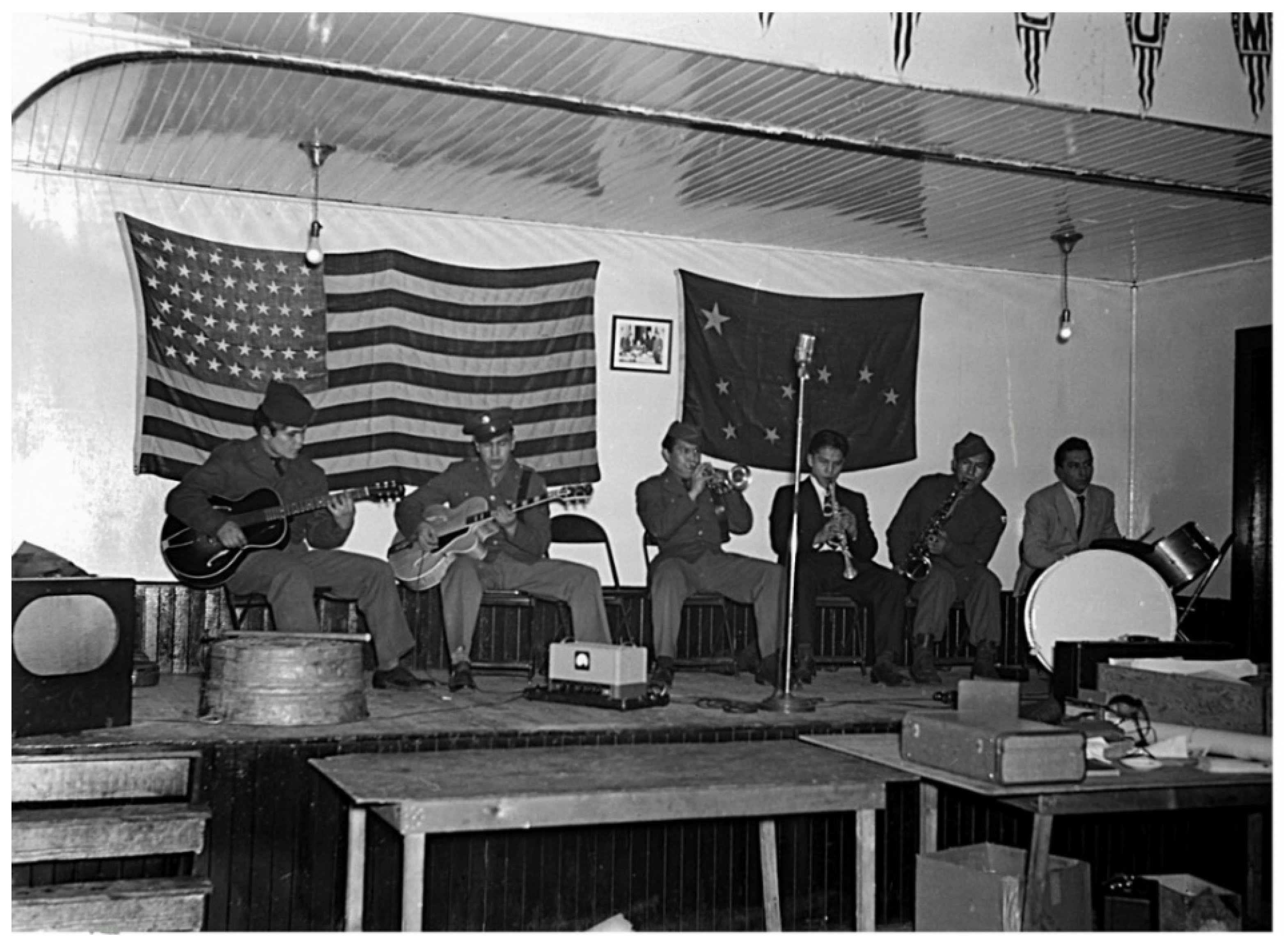

After the Alaskan flag had been established in ANB Halls, Indigenous imagery began to appear alongside it, just as Indigenous imagery had been paired with the American flag. The Alaskan flag that was presented at the 1927 Convention in Angoon was likely the same flag that appeared in the 1945 Convention, when Angoon once again hosted the annual gathering (Figure 10). In this photograph, Native musicians in military uniforms—no doubt serving or having served the U.S. military in WWII—played on stage in front of a large American flag and a smaller Alaskan one, with a framed photograph hung between them. Magnification of the small image between the flags reveals it to be a well-known photograph of Alaskan governor Ernest Gruening, flanked by legislators and ANB and ANS Grand Camp Presidents Roy and Elizabeth Peratrovich, signing the Anti-Discrimination Act of 1945 (Figure 11). Alaska’s Anti-Discrimination Act was one of the earliest pieces of civil rights legislation in the United States, outlawing racial discrimination in housing and public facilities in the territory. The ANB and ANS had lobbied hard for this bill—despite the protests of many Whites, who continued to hold racist beliefs about Native people not being “civilized” enough to associate with—and ANS President Elizabeth Peratrovich made a famous speech in Senate chambers that many credit for the passage of the bill.57 The fact that the ANB showcased this image at its November 1945 Convention—a few months after Roy and Elizabeth Peratrovitch watched Governor Gruening sign the bill on 16 February 1945—showed the pride of place that images of Indigenous leadership took in the ANB Hall, alongside the flags of federal and territorial governance.

Figure 10.

ANB Band at the Grand Camp Convention, Angoon, 1945. Photo courtesy of Ben Paul. Used with permission.

Figure 11.

Signing of the Anti-Discrimination Act, 16 February 1945. Left to right: Sen. O.D. Cochrane (D-Nome), Elizabeth Peratrovich (ANS Grand Camp President), Governor Ernest Gruening, Rep. Edward Anderson (D-Nome), Sen. Norman Walker (D-Ketchikan), Roy Peratrovich (ANB Grand Camp President). Alaska State Library Historical Collections, ASL-P274-1-2. Used with permission.

Perhaps the most significant example of the pairing of an American flag with imagery of Indigenous leadership occurred in the ANB Hall in Wrangell on 3 June 1940 (see Figure 1). This was the occasion of the so-called “Wrangell Potlatch,” a complicated event hosted by local Tlingits and White members of the Wrangell Chamber of Commerce to celebrate the completion of a new “totem park” built for tourists on an island in Wrangell’s inner harbor.58 Earlier that year, the federal government had sponsored the restoration of a historic Tlingit clan house and totem poles on the island, known as “Shakes Island” after the powerful line of Naanyaa.aayí clan leaders named Shéiksh, who had lived there since the 1830s. The Shakes line had been interrupted in 1916, when Shéiksh VI had died and a local missionary had blocked the intended successor, Charlie Jones (the same Tlingit man who had won the right to vote in 1923), from formally assuming the title of Shéiksh VII.59 Although many Whites celebrated the disruption of the Shéiksh line in 1916, by 1940, tourist desire for “total authenticity” in the newly restored Shakes Island required a “Chief Shakes” to accompany the “Shakes House,” and the Wrangell Town Council asked Charlie Jones to officially assume the title of Shakes VII at the June dedication ceremony. The Wrangell Potlatch would thus double as a dedication of the totem park on Shakes Island and as a Naanyaa.aayí-hosted potlatch to officially recognize the seventh Tlingit Shéiksh and the continuation of Tlingit clan leadership in Wrangell.

The ceremony to name Jones as Shéiksh VII took place in the ANB Hall on the afternoon of June 3.60 Significantly, Wrangell Tlingits chose to hold the naming ceremony in the ANB Hall, rather than in the newly restored clan house on Shakes Island—perhaps because the hall offered Tlingits a sovereign space apart from the tourist spectacle at the totem park. Charlie Jones stood on the stage (he appears in Figure 1 at the center of the group on the stage) wearing the killer whale crest of the Naanyaa.ayí clan depicted in the Killer Whale Flotilla robe and a shakeet.at dance headdress. Behind him, beneath an archway with the ANB logo painted on one corner and the ANS logo on the other, an American flag appeared gathered up with a small framed image in its center. When magnified, this image is legible as a well-known drawing of an earlier Shéiksh, said to have been sketched by a Russian officer in the 1830s or 1840s (and still displayed in Wrangell today) (Figure 12).61 It is not certain which Shéiksh this depicts—II or III?—but what is significant for this inquiry is that the portrait depicted a high-ranking leader of the Naanyaay.ayí clan who had long represented Tlingit leadership for the Shtak’héen kwáan Tlingit in the Wrangell area. Hanging this image in the ANB Hall during the naming ceremony of Charlie Jones as Shéiksh VII not only affirmed the restoration of this important lineage, it also asserted the importance of Indigenous governance in the middle of an event that had been commandeered by federal and local officials. The fact that the ANB hung the Shéiksh portrait in the slot that the territorial legislature had previously reserved for an American president further underlined this statement of Indigenous leadership and sovereignty at the Wrangell Potlatch.

Figure 12.

Detail of Figure 1, showing the framed portrait of Shéiksh hung between the gathered flag in the ANB Hall for the Wrangell Potlatch, 3 June 1940. Magnification and image credit to Zachary Jones, Alaska State Library.

The Shéiksh display at the Wrangell Potlatch is one of the most striking examples of a gathered flag paired with Indigenous imagery in an ANB Hall. It suggests the multiple allegiances that Native people maintained in Southeast Alaska in the 1940s, and the persistent use of visual imagery to publicly proclaim those identities. Charlie Jones was a seventy-six-year-old Tlingit Indian who spoke little English and who honored his obligations to his Naanyaa.ayí clan; he was also a proud ANB member who supported younger English-speaking members as delegates to Grand Camp Conventions, and he had fought in court to be recognized as a U.S. citizen. All of these identities were on display in the ANB Hall for the Wrangell Potlatch—the American flag, the European sketch of an earlier clan leader of the Naanyaa.ayí Tlingit, and the living Shéiksh dressed in his clan crests beneath the archway of the ANB stage—and none contradicted the other.

The 1940 Wrangell Potlatch was among the last displays of a gathered American flag framing Indigenous imagery in an ANB hall. After 1945, the “gathered” flag largely disappeared from ANB halls—perhaps because, as former Grand Camp president Ron William told me, the ANB had a stronger understanding of U.S. Flag Code after their service in World War II and began to incorporate a color guard to officially post the colors on staffs within their halls.62 The ANB was also changing in the 1940s, as the federal government had required its leadership to establish, in 1939, a separate federally-recognized tribe (rather than its dues-paying organization) to negotiate the Tlingit and Haida land claims settlement.63 Many ANB members served on the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska in its first few decades, but many others resented the federal government’s interference in their own political organizing.64 It was another chapter in the complicated relationship between Indigenous sovereignty and the federal government in Alaska.

Robert Price writes that the ANB “represented an entirely new approach to the United States government: it moved from ad hoc complaints [from individual Tlingit and Haida clan leaders] to an organization, and it now spoke in the language and concepts of the white American culture instead of that of an Indian tradition” (Price 1990, p. 87). This adoption of American rhetoric and symbolism was a “necessity,” as ANB founder Peter Simpson stated, in order to be heard and seen by settler society.65 But the ANB and ANS never ceased to acknowledge clan relationships or to represent itself with Indigenous imagery, effectively asserting the legitimacy of Native governance and Native identity within the United States. This assertion of Native/American citizenry is how Julie Williams, an ANS member in Juneau, suggested reading the displays of American flags paired with Indigenous imagery in early ANB Halls: as a way to show that, even as ANB and ANS members marked themselves as U.S. citizens, they were proclaiming “we are still who we are” as Native people.66

Other ANB members I interviewed said that Native people always already were “American citizens,” and that they adopted the American flag to claim this identity as their right. Dennis Demmert, a long-time ANB member and former ANB Grand Camp President, told me that many early ANB members had a strong sense of being the “original Americans,” and that it struck them as illogical not to be able to claim U.S. citizenship.67 Thus Peter Simpson asked rhetorically in 1911, “Why is it that the Indians of Alaska are not fit to become American citizens? They are the only original Americans; that is, the American Indians are the only native Americans on this continent” (Simpson 1911).68 Cyrus Peck, Sr., an ANB member who sought citizenship through the 1915 Alaska Native Citizenship Act, later regretted studying for the exams and signing the oaths required by an Act that undermined the fact that “we are citizens to start with, we are not foreigners.”69 This deep sense of citizenship in their homelands—and the adoption of the American flag to claim this citizenship—was apparent in a photo from the 1920s of a young Tlingit boy, Amos Wallace, whose parents dressed him for Juneau’s Fourth of July parade in his clan regalia, along with small American flags and a sign that read “Original American” (Figure 13).70 Here, the flag represented not a new or additional identity to that of Wallace’s Tlingit clan, but a new symbol for what was already inherently his identity as a Native American. This sense of the flag representing the “original Americans” also connects to American Indian uses of the flag in the continental United States, where more scholarship on flag imagery is available.71 George Horse Capture (A’aninin) wrote that the American flag in Plains Indian arts was often an expression of patriotism—not for the United States, but for the Indians’ deep-seated respect for the land and their own tribal nations.72 More research is needed on the use of flags among Alaska Natives, who adopted Russian, British, and Hudson Bay flags, to name a few, long before the arrival of American flags and the establishment of the ANB.73

Figure 13.

Amos Wallace (Tlingit) dressed for a Fourth of July parade, c. 1928–30, Juneau, Alaska. Amos Wallace Photograph Collection, William L. Paul Sr. Archives, Sealaska Heritage Institute, Juneau, Alaska. Used with permission.

Like many Native societies born in the Progressive Era, the Alaska Native Brotherhood and Alaska Native Sisterhood walked a careful line of “patriotic pluralism,” pursuing a strategic commitment to the settler state while upholding their sovereignty as Indigenous people. Previous scholarship has emphasized the discursive ways in which the ANB positioned its members as Native people within a rhetoric of Americanization, and how their speeches, collective resolutions, and newspaper editorials established a Native voice within the fray. But it is also important to recognize the deep symbolic work of a people who were accustomed to displaying identity and clan membership through crests and other symbolism, and to acknowledge the signifiers that the ANB deployed within settler and Indigenous sign systems. The pairing of a gathered American flag with Indigenous imagery in ANB Halls from the 1920s through the 1940s may have indexed this complex work of patriotic pluralism for Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian peoples in Alaska, and their efforts to represent Native/American citizenship within the United States.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Beattie, W. G. 1910. Superintendent of Sitka Training School. The Home Mission Monthly June: 179–80. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, Margaret. 1981. Window on the Past: The Photographic Ethnohistory of the Northern and Kaigani Haida. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Daley, Patrick J., and Beverly A. James. 2004. Cultural Politics and the Mass Media: Alaska Native Voices. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dauenhauer, Nora Marks, and Richard Dauenhauer, eds. 1994. Haa Kusteeyí: Our Culture: Tlingit Life Stories. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, Philip. 1958. The Native Brotherhoods Modern Intertribal Organizations on the Northwest Coast. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin, vol. 168. [Google Scholar]

- Gmelch, Sharon Bohn. 2008. The Tlingit Encounter with Photography. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, Toby, and Joel Kopp. 1993. The Flag in American Indian Art. Cooperstown: New York Historical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Hope, Andrew, II. n.d. Founders of the Alaska Native Brotherhood. Sitka: Self Published.

- Jonaitis, Aldona. 2006. Art of the Northwest Coast. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jonaitis, Aldona, and Aaron Glass. 2010. The Totem Pole: An Intercultural History. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lomawaima, K. Tsianina. 2013. The Mutuality of Citizenship and Sovereignty: The Society of American Indians and the Battle to Inherit America. American Indian Quarterly 37: 333–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, Lucy. 2005. Citizen Indians: Native American Intellectuals, Race, and Reform. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe, Kimberly L., ed. 2008. In Sisterhood: The History of Camp 2 of the Alaska Native Sisterhood. Juneau: Hazy Island Books. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe, Peter M. 2014. A Dangerous Idea: The Alaska Native Brotherhood and the Struggle for Indigenous Rights. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mirel, Jeffrey. 2010. Patriotic Pluralism: Americanization Education and European Immigrants. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Donald Craig. 1997. Sold American: The Story of Alaska Natives and Their Land. Hanover: Dartmouth University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Emily L. 2018. Proud Raven, Panting Wolf: Carving Alaska’s New Deal Totem Parks. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Fred. 2007. Then Fight For It!: The Largest Peaceful Redistribution of Wealth in the History of Mankind and the Creation of the North Slope Borough. Bloomington: Trafford Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pohrt, Richard A. 1976. The American Indian, the American Flag. Flint: Flint Institute of Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Robert. 1990. The Great Father in Alaska: The Case of the Tlingit and Haida Salmon Fishery. Juneau: First Street Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qayaqs, Jan Steinbright. 2002. Qayaqs and Canoes: Native Ways of Knowing. Anchorage: Graphic Arts Center Publishing Company for the Alaska Native Cultural Center. [Google Scholar]

- Raibmon, Paige. 2005. Authentic Indians: Episodes of Encounter on the Northwest Coast. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmittou, Douglas A., and Michael H. Logan. 2002. Fluidity of Meaning: Flag Imagery in Plains Indian Art. The American Indian Quarterly 26: 559–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Peter. 1911. The Native Viewpoint on Citizenship. The Home Mission Monthly 8: 179–81. [Google Scholar]

- Spartz, India, and Inouye Ron. 1991. Fhoki [sic] Kayamori: Amateur Photographer of Yakutat, 1912–41. Alaska History 6: 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Stanciu, Cristina. 2019. Americanization on Native Terms: The Society of American Indians, Citizenship Debates, and Tropes of ‘Racial Difference. NAIS: Journal of the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association 6: 111–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandtman, Wendy, and Cy Peck Jr. 1983. A History of the Alaska Native Brotherhood and Sisterhood. Presented at ANB Grand Camp Convention, Juneau, AK, USA, November 14–19. Cassette tape in Walter A. Soboleff Papers, Box 1, Sealaska Heritage Institute, Juneau, Alaska. [Google Scholar]

- Swagel, Will. 1994. Alaska’s Flag: Eight Stars of Gold on a Field of Blue, The Story of Alaska’s Flag. Sitka: Sitka Historical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Michael. 2016. Writing in Brotherhood: Reconstituting Indigenous Citizenship, Nationhood, and Relationships at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Ph.D. disssertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, Thomas. 1998. Introduction: Who Owned Southeast Alaska? In Haa Aaní, Our Land: Tlingit and Haida Land Rights and Use. Seattle: University of Washington, for Sealaska Heritage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, Thomas F. 2004. Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park: Ethnographic Overview and Assessment. Washington: National Park Service. [Google Scholar]

- Vigil, Kara. 2015. Indigenous Intellectuals: Sovereignty, Citizenship, and the American Imagination, 1880–1930. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Worl, Rosita. 1990. History of Southeastern Alaska Since 1867. In Handbook of the North American Indian, Vol. 7: The Northwest Coast. Edited by Wayne Suttles. Washington: Smithsonian. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Other Native rights organizations were established earlier than the ANB, but either lapsed or ended (e.g., Hui Aloha ‘Āina, the Hawaiian Patriotic League, which was established in 1893, but lapsed in 1901 before being reestablished in the 21st century). The Alaska Native Brotherhood and the Alaska Native Sisterhood have continuously operated in Alaska to the present day, although their power has been eclipsed (or some would say augmented) by the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, the federally-recognized tribe for the Tlingit and Haida, that the ANB/ANS helped create in 1939; Sealaska Corporation, the corporation for Southeast Alaska Natives created by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971; and the Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN), which was created in 1966 to represent Alaska Natives across the state. |

| 2 | Alaska Native citizenship and desegregated schools were court cases won by William Paul, a Tlingit attorney for the ANB who represented Charlie Jones in the citizenship case in 1923 and Paul and Nettie Jones in their daughter’s school enrollment case in 1929. For an overview of William Paul and the ANB, see (Paul 2007; Mitchell 1997, pp. 193–251; Metcalfe 2014); for one of the few published works on the history of the ANS, see (Metcalfe 2008). |

| 3 | The quote is from the earliest extant Constitution of the Alaska Native Brotherhood of 1917, the entirety of which is printed in (Drucker 1958, p. 165). |

| 4 | This rhetoric was common to other Progressive-era groups as well. In 1918, Chauncey Yellow Robe, who identified as “Sioux,” published an article in the Society of American Indian’s journal stating, “We must Americanize our glorious America under one government, one American language for all, one flag, and one God.” Yellow Robe quoted in (Stanciu 2019, p. 121). |

| 5 | For more reevaluations of the ANB, see (Taylor 2016, pp. 138–39; Price 1990; Worl 1990, p. 157). |

| 6 | The quote is from Dr. Rosita Worl (Tlingit), ANS member and director of Sealaska Heritage, quoted in (Taylor 2016, pp. 138–39). For another ANB member’s reevaluation of the early ANB, see the comments of Paul Jackson (Tlingit), in (Qayaqs 2002, p. 105). |

| 7 | For a summary of the critiques of the Society of American Indians, as well as a reappraisal of its practices, see (Lomawaima 2013). |

| 8 | Stanciu quotes (Mirel 2010). |

| 9 | The discursive strategies of Progressive-era leaders are the focus of a great deal of recent literature, including (Stanciu 2019; Taylor 2016; Vigil 2015; Lomawaima 2013; Maddox 2005). |

| 10 | As I explain later in the essay, crests are symbols of animals or other entities owned by specific lineages on the Northwest Coast and used to identify their membership within particular clans. For more on the customary use of clan crests, particularly among the Tlingit and Haida, see (Jonaitis 2006, vol. 4, pp. 135–36). |

| 11 | According to Jeff L. Hendricks, Deputy Director of the Americanism Division for The American Legion, the first prohibition of “festooning” appeared in the U.S. Flag Code on 22 June 1942, Chapter 435, § 4, 56 Stat. 379. Bunting was acceptable, but the flag itself was to “fly free.” I appreciate Mr. Hendricks’s help in researching U.S. Flag Code. |

| 12 | I appreciate the help of Amanda Shores Davis, Executive Director of the Star Spangled Banner Flag House and Museum in Baltimore, Maryland, for pointing me to examples of “gathered” American flag displays in Baltimore and Washington, DC between 1910 and 1914. |

| 13 | My thanks to James Simard, formerly at the Alaska State Historical Library, and Nathan Cohen for drawing my attention to this photograph of the first Territorial Legislature. Alaska’s capitol building in downtown Juneau was not completed until 1931, leaving the legislature to operate in rented rooms like the Elks Hall downtown. Note that the 46-star flag was an anachronism in 1913, as New Mexico and Arizona had been admitted as states in January and February of 1912, respectively, and President Taft had introduced a new 48-star flag on 4 July 1912. See “The Flag of the United States,” http://www.usflag.org/history/the48starflag.html. The flag in this images appears with the canton at the flag’s own left (rather than the more common display of the canton at the flag’s own right, as would be standardized in later Flag Code. |

| 14 | Ron Williams, former ANB Grand Camp president and ANB member, told me in an interview that he did not think there was any significance to the gathered flag imagery in early ANB Halls, other than the fashion of the time (interview with the author, 27 June 2019, Juneau, Alaska). Other ANB and ANS members who attended my presentation at Sealaska Heritage Institute in Juneau, Alaska on 28 June 2019 had mixed interpretations about the significance of the imagery, as I discuss in this article. I am grateful to Sealaska Heritage Institute for inviting me to be a Visiting Scholar in June 2019 and for providing a forum in which to present an earlier stage of this research. |

| 15 | ANB minutes document a great deal of symbolism for the objects on display in their halls. At the 1928 Grand Camp Convention in Sitka, for example, Sisterhood Grand President “Mrs. Ray James” explained the meaning of the colors of the red-and-gold table covers that the Sitka camp of the ANS had created for the delegates: “Red: because we are a red race. Gold: because our land is full of the precious metal. Also that in the olden times the red color was used as a war paint, and therefore the Sisterhood of Sitka gives the color red to their brothers to fight their modern battles for us.” Minutes from 1928 Convention in Sitka, p. 5; Walter A. Soboleff Papers, Box 1, Sealaska Heritage Institute, Juneau, Alaska. |

| 16 | For a history of Central Council, which the ANB initially established as the Tlingit and Haida Claims Committee in order to negotiate a land settlement with the federal government, see (Metcalfe 2014, pp. 35–40). |

| 17 | According to the Dauenhauers, the thirteen founders of the ANB were Peter Simpson (Tsimshian from Metlakatla), Chester Worthington (Tlingit from Wrangell), Ralph Young (Tlingit from Hoonah and later Sitka), Paul Liberty (Tlingit from Sitka), Marie Orson (Tlingit), Frank Price (Tlingit from Sitka), James Watson (Tlingit from Juneau), Eli Katanook (Tlingit from Angoon), Frank Mercer (Tlingit from Juneau), William Hobson (Tlingit from Angoon), James C. Johnson (Tlingit from Klawock), Seward Kunz (Tlingit from Auke Bay/Juneau), and George Fields. See also (Hope n.d., pp. 8–33). |

| 18 | For more on Peter Simpson, see (Dauenhauer and Dauenhauer 1994, pp. 664–76). |

| 19 | Numerous scholars have pointed to the 1912 election of Alaska’s first territorial legislature as a catalyst for the founding of the ANB. See, for example, (Daley and James 2004, pp. 60–61; Price 1990, p. 87). |

| 20 | The quote is from (Beattie 1910); quoted in (Price 1990, p. 88). |

| 21 | A copy of the earliest photo of the ANB, which was missing founders Seward Kunz and Marie Orsen, is in the Alaska Historical Library, ASL-P33-01. Founding member Ralph Young remembered that the group took the photo after lunch at their meeting on 5 November 1912. See (Dauenhauer and Dauenhauer 1994, p. 694). |

| 22 | Ralph Young, quoted in (Dauenhauer and Dauenhauer 1994, p. 694). Others have explained that the arrow was shot into the air in 1912 and should not touch the ground, so that the work of the ANB continues. |

| 23 | Writing of other Progressive-era Native leaders, Kara Vigil argues: “For writers and activists like Eastman, Montezuma, Bonnin and Standing Bear, access to political citizenship in the United States was of paramount importance, not because they aimed for integration into American society but rather because they saw political equality as a means for reshaping the settler-colonial nation that continued to intervene in the affairs of their people and in their lives.” See (Vigil 2015, pp. 16–17). |

| 24 | Quoted in (Metcalfe 2008, p. 33). |

| 25 | For a statement on these values that were taught at the Sitka Industrial Training School, see (Beattie 1910); quoted in (Price 1990, p. 88). |

| 26 | Maddox has chronicled the extensive use of flag drills, pledges of allegiance, and other nationalist practices in U.S. boarding schools intended to assimilate Native Americans. |

| 27 | Quoted in (Daley and James 2004, p. 34). |

| 28 | Quoted in (Raibmon 2005, p. 170). |

| 29 | Quoted in (Blackman 1981, p. 35). |

| 30 | The Alaska Fisherman, the newspaper sponsored by the ANB, described in 1929 the new ANB Halls built in Kake and Wrangell, noting that “all of them [are] of dimensions of about 80 feet by 40 feet” (“A.N.B. Notes,” Alaska Fisherman vol. 5, no. 12 [January 1929], p. 12). The ANB Halls appear to be closely modeled after each other, with a stage at one end and sometimes balconies for more audience seating above the main floor; however, I do not know of an official architectural schema for the halls. Some halls were repurposed from other buildings, like the first ANB Hall in Juneau, which was originally a mess hall from the defunct Treadwell Mine on Douglas Island; ANB members bought the building and carefully floated it across Gastineau Channel to Juneau on two fish scows (Walter Soboleff, quoted in Strandtman and Peck 1983). |

| 31 | For more on the blurred roles between “traditional” and “progressive” Tlingits in Sitka at this time, see (Raibmon 2005, chp. 8). |

| 32 | Rosita Worl and many others have noted that ANB and ANS members quickly mastered parliamentarian procedure—Robert’s Rules of Order—because they were already familiar with the strict protocols of ceremonial speech. Philip Drucker, an anthropologist who visited the ANB in the 1950s, also noted “such purely aboriginal procedures as that of addressing members of the opposite moiety in a certain formal fashion or calling on them to do something in behalf of their clan children (i.e., the children of the men of a clan) by speech or song are invoked to create situations in which, by ancient standards, the persons addressed must make gifts…Such performances are obviously the essence of the potlatch, that is, the potlatch stripped of its ritual, and with the ANB replacing the clans of the opposite moiety as recipient” (Drucker 1958, p. 61). |

| 33 | Alaska Native Citizenship Act of 1915, excerpted from Sections 1–4; online at https://library.alaska.gov/hist/fulltext/ASL-KFA-1225.A3-1915.htm. |

| 34 | On the fish traps and homesteaders that the ANB fought to remove, see (Price 1990). |

| 35 | Quoted in (Drucker 1958, p. 168). The 1917 ANB Constitution, the earliest extant, appears as a reprint in Drucker’s book. |

| 36 | See (Mitchell 1997, pp. 161–63); see also (Moore 2018, chp. 8). |

| 37 | Taylor (2016, p. 168) noted this change in the ANB platform in his dissertation. For William Paul’s editorials on the Christian duty to fight for the “least of these” (a phrase from the Book of Matthew 25:40), see The Alaska Fisherman vol. 1, no. vi (March 1924), p. 6; “A prayer,” vol. 6, no. 4 (May 1929), frontispiece. |

| 38 | On the role of these brothers, see (Mitchell 1997; Metcalfe 2008; Worl 1990, pp. 153–55). |

| 39 | William Paul, personal biography in response to a letter to the editor from a “Concerned Citizen,” The Alaska Fisherman vol. 1, no. vi (March 1924), p. 6. |

| 40 | See (Dauenhauer and Dauenhauer 1994, pp. 512–14). |

| 41 | See Louis Paul’s defense of Tlingit language in the minutes to the 1927 Angoon Convention, p. 6, Walter A. Soboleff Papers, Box 1, Sealaska Heritage Archives, Juneau, Alaska. |

| 42 | See (Metcalfe 2014; Mitchell 1997; Thornton 1998). |

| 43 | See, for example, (Metcalfe 2014; Thornton 1998). |

| 44 | The ANS and ANB images are in the Alaska State Library Historical Collections, ASL-P33-43. I chose the ANB photo because it shows the koogeinaa more clearly on the chests of ANB members. |

| 45 | The quote is from Albert McKinley Sr., a member of the ANB Executive Committee, speaking at the 89th Annual ANB Convention at Kake in November 2001; quoted in (Thornton 2004, p. 209). |

| 46 | Albert McKinley Sr. quoted in (Thornton 2004, pp. 209–10). |

| 47 | In 1934, a New Deal newspaper printed a photograph of a crew of Hydaburg men under the Skulka Eagle with the caption “Indian Civil Works Crew Under the Alaska Blue Eagle,” referencing the Blue Eagle “crest” of the National Industrial Recovery Act. The history of the Skulka Eagle was also recorded there. See “A Totem Doubles for the Blue Eagle,” Indians at Work: A News Sheet for Indians and the Indian Service (Washington, D.C.: Office of Indian Affairs), 1 August 1934, p. 32. |

| 48 | The information on the Plains headdress worn by Paul Morrison in this photo was provided by Woody Morrison, a descendant of Paul Morrison, in a comment on Facebook, 6 October 2018. I thank Woody Morrison and others who helped interpret this image. |

| 49 | The other two photographs from the Yakutat ANB Hall that display the portrait of George Washington beside the gathered flag are also in the Alaska State Library Historical Collections: PCA-55-31(ANB Basketball team in the ANB Hall) and PCA-55-18 (with the caption on the front of the photograph reading “Funeral of Captain Wm Gray, 28 December 1933”). It is this caption that I use to date the other two photographs with the same set-up in the ANB Hall. All of these photographs were taken by Seiki (sometimes listed as “Shoki” or “Fhoki”) Kayamori, a Japanese man who came to Yakutat to work for the salmon cannery in 1912, and whose interest in photography led to an important record of Yakutat’s Native and non-Native residents until 1941, when Kayamori took his own life two days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. For more on Kayamori, see (Spartz and Ron 1991). |

| 50 | Walter Soboleff quoted in (Metcalfe 2008, p. 15). |

| 51 | On Paul’s interest in Benson’s flag, see (Dauenhauer and Dauenhauer 1994, p. 512). |

| 52 | In fact, it is important to remember that statehood was mentioned in the preamble to the earliest ANB Constitution—the one so often excerpted for its assimilationist language—alongside the goals of Native uplift. “The purpose of this organization,” the complete preamble reads, “is to assist and encourage the Native in advancement from his native state to his place among the cultivated races of the world, to oppose, discourage, and overcome the narrow injustice of race prejudice, and to aid in the development of the territory of Alaska, and in making it worthy of a place among the States of North America.” ANB 1917 Constitution, re-printed in (Drucker 1958, p. 168). |

| 53 | Front cover of The Alaska Fisherman, vol. 9 (1932), quoted in (Taylor 2016, p. 177). |

| 54 | Minutes of the Grand Camp Convention, 14 November 1927, 10 am Session, Walter A. Soboleff Papers, Mss 2, Box 1, Sealaska Heritage archives, Juneau, Alaska. |

| 55 | Ibid. |

| 56 | Minutes from the Grand Camp Convention, 18 November 1927, 10 am Session, p. 9. Walter A. Soboleff Papers, Mss 2, Box 1, Sealaska Heritage Archives, Juneau, Alaska. |

| 57 | For the Senate record of the speech, see (Dauenhauer and Dauenhauer 1994, pp. 536–38). Note that several scholars have pointed out that the Anti-Discrimination Act had enough votes to pass before Elizabeth Peratrovich made her famous speech (see, for example, Ross Coen, “Peratrovich true hero, but myth doesn’t match facts about historic Alaska vote,” Anchorage Daily News, 17 August 2015). However, no one disputes that Peratrovich’s impassioned statement made an impression on Alaskan history. |

| 58 | For more on the history of the Wrangell Potlatch, see (Moore 2018, pp. 160–79). |

| 59 | Charlie Jones’s testimony on the interruption of the Shéiksh succession is chronicled in (Moore 2018, pp. 162–63). |

| 60 | The Wrangell Sentinel noted that the “actual coronation of Kudanake as Chief Shakes will take place at the ANB hall” following the dedication on Shakes Island. “Hundreds of Visitors Arriving Here for Potlatch Next Week,” The Wrangell Sentinel 31 May 1940, p. 1. |

| 61 | The original portrait still hangs in Wrangell today. A photograph of the portrait is also in the Alaska State Historical Library, P62-67. |

| 62 | Ron Williams, interview with the author at Sealaska Heritage Institute, 27 June 2019, Juneau, Alaska. |

| 63 | On the shift from the ANB to Central Council, see (Metcalfe 2014, pp. 35–36). |

| 64 | On ANB resentment that the Office of Indian Affairs did not “take easily to Native controlling their own destinies” see Stephen Haycox, “Promise and Denouement,” 16, quoted in (Metcalfe 2014). |

| 65 | Peter Simpson, quoted in ANB Minutes, 1920 Grand Camp Convention, p. 8; Walter Soboleff Papers, Box 1, Sealaska Heritage Institute, Juneau, Alaska. |

| 66 | Julie Williams, interview at Sealaska Heritage Archives, 27 June 2019. |

| 67 | Dennis Demmert in conversation with the author, 17 July 2019, Saxman, Alaska. |

| 68 | Quoted in (Price 1990, p. 89). |

| 69 | Cyrus Peck, Jr., quoting his father in (Strandtman and Peck 1983). |

| 70 | My thanks to Brian Wallace, Amos Wallace’s son, for corresponding with me about this image over email, 30 October 2019. Brian Wallace was not certain of the date this photo was taken, but guessed that his father was 8–10 years old in the photo, placing it around 1928 to 1930. He also noted that Amos Wallace grew up to be a lifelong ANB member. |

| 71 | Several studies have attended to the appearance of the American flag in Native American art from the continental United States, but none included tribes from Alaska. See (Pohrt 1976; Herbst and Kopp 1993; Schmittou and Logan 2002). |

| 72 | Horse Capture quoted in (Schmittou and Logan 2002, p. 563). |

| 73 | Scholarship on flag imagery in nineteenth-century Tlingit and Haida contexts is lacking, even though photographic evidence shows long-standing use of American flags in this region (and earlier, Russian, English, and Hudson Bay Company flags as well). For a few examples of scholarship that attends to flag imagery among the Tlingit and Haida, see (Gmelch 2008, pp. 174–77; Jonaitis and Glass 2010, pp. 54–55). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).