Abstract

World War II and the subsequent period of communist rule severely diminished the amount of historic Jewish architecture in Poland. It is estimated that in the mid-1990s there were about 321 synagogues and prayer houses in the country, all in various states of preservation. This article examines two case studies of synagogues that were salvaged by being transformed into Judaica museums. The first of these is the synagogue in Łańcut and the second concerns the complex of two synagogues and one prayer house in Włodawa. The article contains an analysis of both examples from the perspective of the following factors: the circumstances under which the institution was established, the place that the history and culture of Jews took in the Museum’s activity, the way that Judaica collections and exhibitions were constructed, the substantive, educational, and research activities that were undertaken, as well as the issue of what place these monuments occupy in the town’s landscape.

1. Introduction

From the second half of the 1980s, a growing interest in the heritage of Polish Jews was noticeable both within the country and abroad. This phenomenon developed in the 1990s, and especially intensified after 2000 (Poland’s accession to the European Union in 2004 was a watershed in this regard). Such interest, which is primarily an expression of nostalgic longing for the idyllic image of multicultural pre-war Poland, manifests itself in the forms of the revitalization of synagogues, festivals and days of Jewish culture, artistic and educational activities, as well as social initiatives of cleaning up Jewish cemeteries throughout the country. In the context of the growing interest in Jewish culture and history over the past 30 years, an interesting (and at the same time insufficiently researched) issue is the level of this interest in and the attitude towards Jewish heritage before the fall of the communist regime. Following this lead, my research aims to revise the widespread belief that this sphere of heritage was completely excluded from the scope of academic and social interests in communist Poland. The post-war history of the synagogues in Łańcut and Włodawa described below shows how highly complex the issue is.

This article is an attempt to compare two cases in which synagogues—the one in Łańcut and the complex of three religious buildings in Włodawa—were transformed into museums with the intention of providing education on the heritage of Polish Jews. It contains an analysis of both examples from the perspective of the following factors: the circumstances under which the institution was established, the place that the history and culture of Jews took in the Museum’s activity, the way that Judaica collections and exhibitions were constructed, the substantive, educational, and research activities that were undertaken, as well as the place these synagogues occupy in both the urban landscape and the collective memory. As Sławomir Kapralski wrote:

Following this quote, it is one of my goals to determine whose memory is represented by the two surveyed museums. The time frame of my research starts with the moment the idea of creating a given museum appears, through its period of activity in communist times, up to the time of social, economic, and political transformation in the 1990s. As for the end date, I decided to use the year of Poland’s accession to the European Union, because—mainly due to obtaining access to European funds—at that time, a completely new chapter began in the history of the protection of material heritage in Poland in general and Jewish heritage in particular.The conflict over the landscape does not stop when one of the competing groups is no longer in the competition but turns into a passive conflict of memories. […] In such a situation, the memory of the group that perished and its material representations can be manipulated in an unrestricted way by those who remained. Landscape preserves what the group wants to remember; that which the group wants to forget is destroyed, neglected or preserved in a distorted way.(Kapralski 2001, p. 37)

The subject of the preservation and protection of Jewish prayer houses located in the post-war Republic of Poland was discussed in Polish academic literature on several occasions. The lion share of these publications emerged from the Jewish Historical Institute (Żydowski Instytut Historyczny—ŻIH) and its employees as, from the outset, one of the aims of its activity was to document those Jewish monuments that survived World War II. The first work was published in two parts in 1953 in the ŻIH Bulletin, in the form of an article by Anna Kubiak, in which the most culturally important synagogues were listed (Kubiak 1953a, 1953b). Particular attention should be paid to a number of articles written by Eleonora Bergman and Jan Jagielski (Bergman and Jagielski 1990, 2012; Bergman 1996, 2010; Jagielski and Krajewska 1983; Jagielski 1996). However, the most important result of the work of these two researchers was a catalogue published in the 1990s, which included all buildings that had been identified as former synagogues and prayer houses (Bergman and Jagielski 1996). Simultaneously, a report by Samuel D. Gruber and Phyllis Myers was commissioned for the United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad, in which the results of Bergman and Jagielski’s research were also included (Gruber et al. 1995). From the early publications printed outside of Poland, a book by Carol Hershelle Krinsky (1985) should also be mentioned. When listing publications that provide inventories of heritage sites, one cannot omit the books by Maria and Kazimierz Piechotka, which not only list the most important Jewish monuments (including nonextant ones) but, more importantly, a coherent analysis of the development of synagogue construction in the historical Polish territories (Piechotka and Piechotka [2008] 2015, 2019). For studies on the legal status and attitude of the communist authorities towards Jewish heritage, most important are the publications of Kazimierz Urban, especially the extensively annotated collection of source materials published in 2006 (Urban 2006, 2012. Also worth mentioning are the works of Nawojka Cieślińska-Lobkowicz (2010) about the post-war fate of Judaica and Judaic collections, as well as an article written by Monika Krawczyk (2011) on the legal status of Jewish property.

Over the past 30 years, a number of books and articles have been published on the social and socio-economic aspects related to the material and immaterial heritage of Polish Jews. However, most of these publications focus on processes that have occurred during and after the fall of communism in Poland. Most important are the books and articles of Gruber (2002, [1992] 2007, 2015), the journalist, researcher, and President of Jewish Heritage Europe (www.jewish-heritage-europe.eu), an enterprise that serves as an online resource for Jewish heritage issues in all European countries. The studies of Michael Meng (2011) are certainly worth mentioning, as well as several collective publications (Murzyn-Kupisz and Purchla 2008; Lehrer and Meng 2015).

The synagogues in Łańcut and Włodawa are mentioned many times in academic literature in a historical or historical-artistic context; however, the early period of their existence as museums is most often described very briefly (Piechotka and Piechotka 2019; Burchard 1990; Bergman and Jagielski 1996). An entire article devoted to the wall paintings of the synagogue in Łańcut was published by Andrzej Trzciński (2004). With the incorporation of the synagogue in Łańcut into the “Hasidic Route” programme, an educational folder about the synagogue in Łańcut was published (Cichocki and Litwin 2010). Jerzy Baranowski (1959) and Ireneusz Wojczuk (1996) wrote about the architectural form of the Great synagogue in Włodawa, while Jakub Nastaj (1998) published an article describing the history of a Small synagogue. Due to the fact that since 1994 the Museum in Włodawa has issued its own magazine, a number of articles about its current activity and the history of Włodawa Jews have been published (e.g., Bajuk 1998; Bem 2000; Bem 2004; Kurczuk 1999). An interesting example in this field is two articles by Kapralski (2001, 2015), in which the author analyzes the symbolic change of the place of the Łańcut synagogue in the landscape of the town after World War II.

The information and conclusions contained in this article are part of broader research conducted within the framework of my doctoral studies. While working on the history of museums in the synagogues in Łańcut and Włodawa, I had the opportunity to use a number of archival materials made available by the following institutions: the Municipal Public Library in Łańcut (MPLŁ), the Archive of the Castle Museum in Łańcut—Urban History Department (ACMŁ-UHD) and the Archive of the Łęczyńsko-Włodawskie Lakeland Museum in Włodawa—History Department (ŁWLMW-HD). In this article, I also used iconographic materials that have been shared with me by the Cabinet of Engravings of the University Library in Warsaw, Mrs Maria and Mr Michał Piechotka, and Mr Czesław Danilczuk, a photographer from Włodawa. I would like to thank all of these institutions and individuals for helping me in my research.

As for the volume and content of the archival resources of the above-mentioned institutions, there is a significant disproportion between the number of documents available for the two case studies. The collection of documents from the archive of the Łańcut Castle Museum regarding the history of the synagogue at the time when it served as a branch of this institution is relatively small. There are a few archival resources on the takeover of the building by the Museum, while the process of transferring it to the Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland in 2009 is even less documented. Available archives mainly consist of monthly and annual plans and reports on the substantive activities of the Regional Department and the documentation of conservation works. Information gaps are partially filled by documents and photos stored in the Public Library, especially concerning the period immediately before the transformation of the synagogue into a museum. In comparison, the archival resources of the Łęczyńsko-Włodawskie Lakeland Museum in Włodawa look much better, including not only annual reports and conservation files but also exhibition plans, photographic documentation of exhibitions, catalogues, and leaflets. Unfortunately, both museums have only partial information on the attendance and characteristics of visitors. Based on the data available in this regard, it is impossible to draw consistent conclusions.

2. Jewish Heritage in Poland after World War II

2.1. Jews in Communist Poland

Various factors, primarily related to the scale of the damage that hit Poland during World War II, to the shifting of borders connected with population movement, and to the administrative mess associated with the introduction of the new political system, make it impossible to accurately determine the number of Jews living in the country at that time. At its peak, it is estimated at about 250,000–300,000; however, most of them were repatriates from the USSR, for whom Poland was only a short stop on their way to countries in the West and Palestine. Probably about 120,000 of them left within a few months, and the 1947 census suggests that there were about 90,000 people of Jewish origin in the country. In mid-1948, approximately half (about 50,000) of the Jewish population was living in Lower Silesia, as well as in Łódź, Warsaw, Krakow, Szczecin, and Upper Silesia. Most of them were displaced persons who had no links with the pre-war Jewish residents of these cities (Bergman 1996, p. 133). Indeed, Szczecin and much of Lower Silesia were part of territory gained by Poland when its borders were shifted west in the wake of World War II.

The Jewish population in Poland decreased dramatically within less than 30 years after the war, owing to four major waves of emigration. The first of these took place in 1945–1947, a period which also witnessed a wave of internal emigration, because, after the pogrom that took place in Kielce in July 1946, many Jews from small towns moved to larger cities, fearing for their safety. This fear was often intensified by the hostile attitude of their Polish pre-war neighbours and the actions of the armed anti-communist underground, particularly active in the country’s outlying provinces. The second mass emigration took place after the establishment of the State of Israel and occurred in 1949–1950, in which about 20–30 thousand people of Jewish origin left Poland. After leaving, Jews could not return, as the communist authorities forced them to renounce their Polish citizenship. Another 27,000 people (approximately) left the country in 1956–1957 as a result of the temporary opening of the borders following Gomułka’s Thaw, named after the Polish communist leader who steered the country out of the Stalinist era. The fourth and last great aliyah took place as a result of the events of the so-called Polish March in 1968. Although the number of those leaving was relatively small (15–20 thousand), it was the most tragic of all the four mentioned above, because it took place amidst an aggressive anti-Semitic campaign. Those who left the country—most of them fully assimilated representatives of intellectual social elites—were forced to do so in a hurry, without the right to return (Cała 1998, p. 245).

Even before the end of World War II, the Central Committee of Jews in Poland (Centralny Komitet Żydów w Polsce-CKŻP) was established under the auspices of the Polish Committee of National Liberation (Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego—PKWN—an executive governing authority established by the communists in 1944 for the Polish territories liberated by the Soviet Army). The Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland, formed by the transformation of the PKWN in early 1945, issued a resolution (okólnik) on 6 February 1945 entitled On the Temporary Settlement of the Religious Matters of the Jewish Population. This resolution was the only official ordinance issued to regulate the legal status of the Jewish minority during more than 40 years of the existence of communist Poland, despite the fact that in the second half of the 1940s the Ministry of Public Administration worked on a comprehensive bill (Urban 2012, p. 314, pp. 330–32-facsimile). Paradoxically, in the first years after the war, the Polish communist authorities showed relative favour to Jews. Various political parties cooperated under the CKŻP, financial support was obtained from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, while Jewish orphanages, hospitals, and schools, as well as Jewish Religious Congregations, existed. This situation did not last long. In 1949, political parties were liquidated, Jewish social institutions were taken over by the state, and the CKŻP was transformed into the Socio-Cultural Jewish Association in Poland (Towarzystwo Społeczno-Kulturalne Żydów w Polsce-TSKŻP), completely dependent on the communist authorities, which immediately ceased cooperation with the Joint and the World Jewish Congress. A Mosaic Religious Union (Związek Religijny Wyznania Mojżeszowego—ZRWM) was established, directly subordinated to the TSKŻ. All these activities actually eliminated the autonomy of the Jewish minority in Poland and became one of the impulses for emigration. In the first half of the 1950s, 387 Jewish cemeteries were set to be closed and 48 were liquidated (designated for “utility purposes”). Gomułka’s Thaw caused a short-lived cultural and social revival of Jewish life (for example the activities of the Joint representation were resumed, discontinued again in 1967) and, at the same time, an increase of anti-Semitic behaviour. The events of the year 1968 became the climax. The anti-Semitic twist and subsequent mass emigration virtually led to the disappearance of Jews from Polish public life. The only traces that remained of the once most numerous minority in Poland were synagogues and cemeteries (Cała 1998, pp. 256–86; Urban 2012, p. 327).

All the emigrations strongly diminished the cultural and social life of the Jewish minority. It should be mentioned that the tragedy of the Holocaust and the post-war years radically changed the way of self-identification among Polish Jews. As early as the 1940s, it was estimated that only half of the Jews practised the Mosaic religion and that this number was steadily decreasing. Mental trauma also pushed many Jews to deny their origin and increased the tendency for complete assimilation. These processes—like subsequent waves of emigration—were more or less officially supported by the state authorities and, as a result, in the 1970s, public Jewish life in Poland practically ceased to exist. Changes in this field only began to occur in the next decade with the weakening position of the communist authorities and the growth of the political opposition. One of the signs of change was the agreement of the return of the official Joint representatives in 1981 (Cała 1998, pp. 288–89).

2.2. Jewish Property in Poland after WWII

The Second World War was a clear turning point for Jewish architecture, art, and indeed for research on these subjects. Most Jewish communal buildings in Poland were destroyed, including all wooden synagogues erected between the 17th and the beginning of the 19th century and most of the monumental masonry synagogues built in the 19th century. The same fate befell Jewish cemeteries and a huge percentage of works representing the fine and applied arts. As a result of shifting borders, a large number of historic synagogues, located in the so-called Eastern Borderlands of the pre-war Polish Republic, ended up outside the country. On the other hand, Jewish prayer houses located on German territories incorporated into Poland (referred to in the official propaganda as “the Regained Territories”) joined the total number of buildings. In some cases, photographic and inventorial documentation prepared before World War II provided the only traces of a given monument.1 In 1947, 38 synagogues and dozens of prayer houses were active. However, it is not known how many of these places of worship were pre-war ones that had been reopened (Bergman 1996, p. 133).

In most towns where synagogues were still standing, Jewish communities had ceased to exist, which means that the users and guardians of these buildings had disappeared. The majority of Jews who found themselves in Poland shortly after the war had been residents of pre-war Poland who survived the conflict in the USSR and were later repatriated and mainly settled in Lower Silesia. Some of them (about 2.5 thousand) survived the Nazi German camps and returned to their hometowns, but after the Kielce pogrom in 1946, the tendency to move to larger urban centres or leave the country intensified. According to the register of Jewish real estate (pre- and post-war), made in 1951–53, there were 524 Jewish cemeteries, 311 synagogues, 70 prayer houses, and 115 other buildings used by the Jewish Congregations inside Polish borders (Urban 2006, pp. 324–27).

The problem with the usage and protection of Jewish communal buildings after World War II was further complicated by the activities of Polish state authorities. According to the resolution of 6 February 1945, all the properties of pre-war Jewish communities were taken temporarily for management by the Polish state (Urban 2006, pp. 69–70). Although the state authorities advised that the synagogues, cemeteries, and other real estate should be transferred for the use of the Jewish congregations, more often local authorities had the most to say in this regard. The Polish government allowed Jews to associate in Jewish Religious Associations; however, they did not treat them as the heirs of the pre-war Jewish religious communities. State legislation from 1945–46 regarding so-called “abandoned and lowered property” made it easier for the authorities to take over Jewish buildings, especially in places where Jewish religious associations did not exist. This way, Polish Jews were actually deprived of the right to own their pre-war properties (Urban 2006, p. 96; Bergman 1996, p. 133; Krawczyk 2012, pp. 704–07).

The authorities did not see much sense in returning real estate Congregations in towns where not a single Jew or only a few of them lived. Unfortunately, this also applied, to some extent, to historic synagogues. Often, especially in smaller towns and villages in outlying Polish provinces, purely utilitarian reasons took precedence over the argument about the desecration of a place of worship. Most often, these pertained to complaints from residents of a given city about the lack of a cinema, community centre, exhibition hall, fire station, or warehouse. While until the beginning of the 1950s, “social and cultural” or “cultural and educational” goals prevailed in this argument, later, such terms as “production” and “economic” were increasingly used. At the same time, Jewish organizations, constantly struggling with financial problems, gave up taking over and maintaining unused religious facilities. With time, the consent to change the way the property was used became the main and most effective solution leading to the building being saved from demolition. Sometimes, local Jewish congregations chose to hand over the synagogue building to local institutions as an alternative settlement, for example, for fencing and taking care of the local cemetery (Urban 2006, p. 44). In the national List of Architectural Monuments announced in 1964, eight Jewish cemeteries were listed (one of which belonged to the Jewish congregation in Lublin) and 72 synagogues (of which seven were in the hands of the ZRWM, encompassing five in Krakow, one in Krzepice, and one in Wrocław). In 1974, 24 synagogues and prayer houses, 19 cemeteries and four mikvahs belonged to the ZRWM. In 1992, the organization changed its name to the Association of Jewish Religious Communities in Poland, and in the middle of the 1990s, it owned 47 cemeteries and 27 synagogues and prayer houses (Bergman 1996, pp. 135–36). According to research conducted, among others, by Eleonora Bergman and Jan Jagielski from the ŻIH, in 1990 there were 245 synagogues in Poland in nearly 200 cities. After correcting this number in the mid-1990s, the researchers gathered information about 321 synagogues and prayer houses in the country, all in various states of preservation (Bergman and Jagielski 1990, pp. 41–42; Bergman and Jagielski 1996, p. 9; Gruber et al. 1995, pp. 65–78). Not all synagogues were considered as monuments. To date, less than 40% of all preserved objects have been listed in the Register of Immovable Monuments (of which almost a third of the total was included in the Register in the years 1980–1989). Other objects lost their original form in the course of numerous reconstructions (Migalska 2012, pp. 99–100).

In 1947, the ŻIH was established at the CKŻP, in place of the Central Jewish Historical Commission (Centralna Żydowska Komisja Historyczna—CŻKH) that had existed since 1944 (Żbikowski 2018, pp. 10, 18–19). In 1951 the Director of the ŻIH Bernard Mark sent an official letter to the Office for Religious Affairs in Warsaw with an (incomplete) list of 18 synagogues in 18 different cities and towns that were at that time being improperly used (Urban 2006, p. 324). In the 1960s, the ŻIH staff, conducting the cataloguing and documentation of Jewish places of worship, prepared photographic documentation in more than a hundred towns. This initiative was discontinued and only resumed in the 1990s. In 1991, the Historical Documentation Department was created as part of the ŻIH. Its task was not only to inventory Jewish monuments in Poland and collect research material on them but also to initiate and coordinate actions aimed at protecting and renovating surviving properties, especially cemeteries and synagogues. Currently, the Department owns probably the biggest collection of photographic documentation covering the fate of Polish synagogues in the 20th century (Jagielski 1996, pp. 91–94; Bergman 1996, p. 135).

The situation with movable Jewish objects was much worse than in the case of immovable monuments. During the Second World War, private art collections, valuables, family heirlooms, and, above all, the most precious items of synagogue furnishings were confiscated, taken abroad, plundered, or destroyed. Jews often hid possessions or used them as a currency or bribe in bids to gain assistance or shelter from gentiles. Immediately after the war, the process began of searching for and recovering those objects that had survived, a task that was carried out by both private individuals and on a national scale. The official search was undertaken by the CŻKH (later the ŻIH), cooperating, among others, with Karol Estreicher—the man responsible for the identification, inventory, and return to the country of art works exported by the Nazis from occupied Poland. Although several successes were achieved in this field, they were small due to the huge scale of losses. Salvage activities were significantly hindered by “seekers of Jewish treasures”, searching through the areas of former ghettos and Jewish properties. Indeed, the antiques trade flourished in the aftermath of the war, although only part of this business was legitimate. Most of the recovered items eventually went to the collections of the Jewish Historical Institute and a number of state and regional museums. Some went onto the antiques market, monopolized in 1950 by the state-owned trading company DESA, or were illegally taken abroad. For a significant proportion of these objects, research into provenance was virtually impossible. In fact, many artefacts were destroyed in the 1950s and 1960s because their cultural value was not recognized (Cieślińska-Lobkowicz 2011, pp. 237–44).

The change of the political system that took place in Poland in 1989 did not bring an immediate transformation in the sphere of cultural heritage protection. This was also the case with Jewish heritage, although the number of synagogues restored in Poland grew in direct proportion to the interest in Jewish culture in Polish society, especially among young people. Shortly after the first Jewish Culture Festival took place in Krakow in 1986, renovation works were started in this city in several of the preserved synagogues. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, similar work was undertaken in a synagogue in Wrocław. However, diametrical changes in this field only took place a decade later and these mainly resulted from four factors. The first one was the Act of February 20, 1997 on the State’s Attitude Towards Jewish Religious Communities in the Republic of Poland (which allowed the Union of Jewish Religious Communities in Poland to apply for the return of pre-war assets) and the Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland (Fundacja Ochrony Dziedzictwa Żydowskiego, FODŻ) established under it in 2001. The second factor was the Act on the Protection of and for Monuments, which entered into force on 17 November 2003 and significantly changed the system of protection of Polish material heritage. The third reason was, undoubtedly, Poland’s accession to the European Union in 2004 and the associated access to EU funds, including funds for the revitalization of monuments and regional development. Finally, the fourth factor is—related to democratization—the development of the NGO sector, since a relatively large number of projects involving the renovation of synagogues in Poland were initiated by local foundations and associations.

3. The Synagogue in Łańcut

3.1. Jews in Łańcut

Łańcut is a town located in south-eastern Poland, less than 20 km east of Rzeszów, the current capital of the Podkarpackie Voivodeship. It gained its municipal charter under the Magdeburg Law in the fourteenth century, and as of the early seventeenth century, Łańcut was in the hands of wealthy Polish magnate families: first the Lubomirskis and—since the 1820s—the Potockis. The town developed to a great extent because of its strategic location on the trade route from Silesia to Ruthenia. After purchasing the town in 1629, the Lubomirski family re-built the existing castle and transformed it into a monumental residence. The palace, expanded in the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century by the Potocki family, remains the greatest symbol of the town to this day (Piechotka and Piechotka 2019, p. 434).

The earliest information about the Jews in Łańcut comes from the 1550s. Although Jews were not allowed to settle in the city as of the 1570s, archival documents note the existence of a small Jewish community with a wooden synagogue and a cemetery. The community experienced three periods of dynamic development. The first of these took place in the eighteenth century, mainly thanks to the good will of the Łańcut’s owners. Nevertheless, in 1719, Aleksander Lubomirski ordered the Jews to leave the town (the community successfully managed to have this ban lifted in 1722). The growing importance of Jewish Łańcut was confirmed by the fact that in 1707, a gathering of the Council of Four Lands (Va’ad arba arazot—the supreme organ of Jewish self-government, which existed within the structures of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from the year 1580 to 1764) took place there (Cichocki and Litwin 2010, pp. 8–9). As of the second half of the eighteenth century, Łańcut began to be strongly associated with the Hasidic movement, which at that time was gaining more and more popularity in the eastern and south-eastern regions of Poland (Piechotka and Piechotka 2019, p. 435). The second period of intensive development of the Jewish community in Łańcut came in the second half of the nineteenth century. As a result of the steady increase in the number of Jews, they constituted over 40 per cent of the entire community of the town in the 1880s. The era of Jewish prosperity in Łańcut—interrupted by the First World War—lasted throughout the whole interwar period. The Jews owned almost all the buildings around the main square and many properties on most of the streets in the centre of the town. The Jewish community ran two schools, cultural associations, a library, sports clubs, and charity organizations. After the Nazis occupied the town in the early days of the Second World War, the Jews of Łańcut were forced to leave the town via the border to the territories occupied by the Soviets. Some of them decided to come back and, together with Jews resettled from nearby towns, they were imprisoned in the ghetto established in January 1942. The liquidation of the ghetto, which took place in August 1942 meant the end of Łańcut’s Jewish community. The few who survived did not return to the city after the war. Most of them settled in Israel and the USA (Cichocki and Litwin 2010, pp. 11–16).

3.2. The Synagogue

The synagogue in Łańcut was built in 1761. The brick building was erected to replace an earlier wooden synagogue that had burned down in 1733. The new structure was located just outside the park surrounding the Lubomirski residence and, at the same time, in the immediate vicinity of the market square. The strong relationship between the Jewish community of Łańcut and the town’s owners at that time is emphasized by the fact that the construction of the synagogue was partly financed by Stanisław Lubomirski (Piechotka and Piechotka 2019, pp. 430, 435). The building was renovated at least twice: in 1898 and 1909–1910. Around 1900 the interior of the synagogue was richly decorated with paintings and stucco work (likewise also painted), which complemented the existing 18th-century decoration. After entering the town in September 1939, the Nazis set fire to the synagogue, but the intervention of the Count Alfred Antoni Potocki (owner of the Łańcut palace), saved the building from complete destruction (Cichocki and Litwin 2010, p. 9). The fire consumed the women’s gallery on the north side and all the wooden furnishings. During the Nazi occupation, the damaged building was turned into a grain warehouse (Trzciński 2004, p. 249).

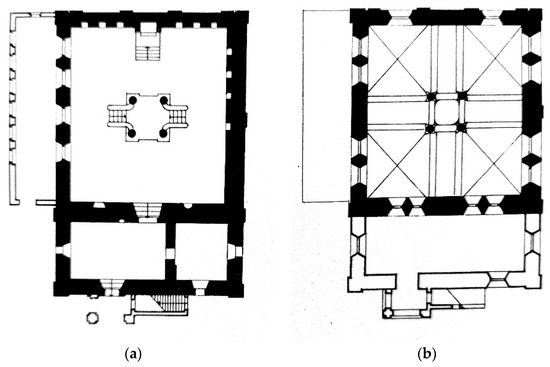

Initially, the brick synagogue consisted of the main hall (men’s hall) constructed on a central plan with the bimah-tower in the centre, a vestibule on the west with a separate room in the southern part (the kehila room, also known as “the Tzadik’s room” or “the Lubelski room”) and two women’s galleries: the first one located over the vestibule (originally lower than today) and the second one, wooden, added to the north wall. The floor of the building is significantly recessed in relation to the level of the ground. During the renovation works around 1900, the walls of the western women’s gallery were raised and stone stairs leading to the gallery were added (Figure 1). At the same time, the entire building was covered with a hip roof (Piechotka and Piechotka 2019, p. 430). The interior of the synagogue is richly decorated with paintings and stuccowork originating from different periods of time (preserved in the main hall, the vestibule, and the kehila room). The men’s hall interior is divided into three horizontal zones of decoration: the lower zone painted in a uniform colour decorated with paintings imitating architectural elements, an arcaded frieze with Hebrew inscriptions inscribed in it in the middle, and the upper zone, which consists of decorations in the spaces between the windows, on the arches of the vault and the canopy walls above the bimah. The decoration of the interior presents a wide range of images present in Jewish religion and culture. They consist of: four crowns (of Torah, priesthood, kingdom and Good Name), biblical scenes (composed with only the symbolically marked presence of human figures), and elements of the Temple furnishings on the walls of the bimah’s canopy; an image of the Leviathan under the bimah’s dome; musical instruments on the eastern wall; 12 zodiac signs arranged on all four walls and a view of Jerusalem and a representation of four animals listed in Pirke avot (leopard, eagle, deer, lion) on the west wall. There are also numerous Hebrew inscriptions filling all the arcade frieze fields and likewise placed in the upper parts of all four walls, as well as on the bimah’s canopy. Most of the inscriptions present the texts of everyday or festive prayers (or short instructions on the order of pray) and texts the of Psalms; others are commentaries on the symbolic images. The whole scheme is complemented by floral decorations, depictions of animals and architectural motifs.

Figure 1.

Plan of the synagogue in Łańcut (a) at the ground level; (b) at the height of the windows of the men’s room (Piechotka and Piechotka 2019). Used by permission.

The oldest known view of this interior sketched at the end of the 18th century by the artist Zygmunt Vogel shows that the stuccowork in the upper zone and the arcaded frieze are the oldest decorative features (Figure 2). As for the painted decoration from this period, it is impossible to discern from Vogel’s drawing whether the stuccowork was covered with paintings. However, it can be seen that the front of the archivolt in the crown of the bimah is decorated with an inscription (perhaps the other walls of the bimah’s crown also looked similar). This means that at that time there was some painted decoration in the men’s hall, although only in a rudimentary form. Although the earliest date found in one of the inscriptions indicates the years 1846–1847, Trzciński suggests that the arcade frieze fields have been successively filled with inscriptions since the beginning of the synagogue’s existence (Trzciński 2004, p. 269). This theory, however, doesn’t find confirmation in the Vogel drawing. The painted decorations of the interior (especially the inscriptions) in the men’s hall was supplemented and repainted several times. During the renovation of the synagogue in the years 1909 and 1910, at least two Jewish artists worked on the new paintings, adding among others: twelve signs of the zodiac, tablets with the Ten Commandments and musical instruments. The painted decoration on the canopy above the bimah probably comes from the years 1934–1935. The paintings decoration on the walls and vault of the vestibule and the kehila room (depicting a view of Jerusalem, four animals—a leopard, an eagle, a deer and a lion, together with inscriptions commenting on these images) comes from the years 1909–1911 (ibid., p. 270).

Figure 2.

Z. Vogel, Interior of the Synagogue in Łańcut, 1797, ink drawing on paper. Cabinet of Engravings, University Library in Warsaw. Courtesy of the library.

The Second World War changed Łańcut both on demographic and social levels. The Jewish community vanished, those Jews who weren’t murdered during the Holocaust left Poland, chiefly emigrating to the USA or Palestine.2 Alfred Potocki, the last owner of the palace, fled the country, escaping shortly before the Red Army reached the town. The economic structure of the city has also changed, mainly due to the development of industrial enterprises (Kapralski 2001, p. 43).

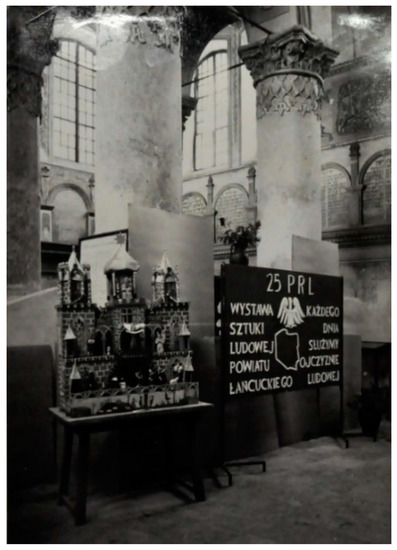

According to the register of Jewish real estates made in 1951–53, the synagogue in Łańcut was managed by the Presidium of the District National Council (PNC) in Łańcut and was used as a grain warehouse by the Communal Cooperative Samopomoc Chłopska. Its condition was described as good (Urban 2006, p. 343). At the beginning of the 1960s, the prayer house—recognized as one of the finest surviving synagogues in Poland—was superficially renovated and secured (Figure 3).3 Before the synagogue was turned into a museum, it was used for exhibition purposes on at least two occasions: in 1957 and 1969. The first of these dates marked the six hundredth anniversary of Łańcut being granted its municipal charter. On this occasion, the town authorities organized solemn commemorations, which were accompanied by a historical exhibition held in the synagogue (Figure 4).4 The second exposition was the Exhibition of Folk Art of the Łańcut Region organized on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Polish People’s Republic (Figure 5).5 In 1969, the synagogue was finally entered into the National Register of Historic Monuments.6

Figure 3.

The synagogue in Łańcut, ca 1960. MPLŁ f. 511/III. Courtesy of the owner.

Figure 4.

Historical exhibition on the occasion of the 600th anniversary of the granting of municipal rights to the town of Łańcut, 1957. MPLŁ f. 362/III. Courtesy of the owner.

Figure 5.

Exhibition of regional art in the synagogue in Łańcut. MPLŁ f. 511/III. Courtesy of the owner.

3.3. Museum in the Synagogue

The synagogue in Łańcut was transformed into a museum on the initiative of two people: Władysław Balicki and Jan Micał. Balicki was a doctor of medicine but also an active member of the Łańcut community, an ethnographer by passion, and a collector. Born in 1907 into a large family of farmers in a village near Łańcut, he received his medical education at the Jan Kazimierz University in Lwów. His diverse collection included a large quantity of regional folk art and artefacts and an extensive library, which also included a small group of Jewish books (part of his collection was stored in the women’s room in the synagogue).7 Not much younger than him, Jan Micał worked from the 1950s until 1975 at the Faculty of Culture in Łańcut. Described as an idealist and dreamer, Micał was privately a self-taught writer (his formal education consisted of just two years at primary school). He wrote poems and novels, and he also prepared a text about the monuments of Łańcut.8 It was he who in 1961 applied for funds for the renovation of the synagogue (Figure 6). According to the text included in the Yizkor book of Łańcut Jews, the idea to create the Judaica museum already existed at the beginning of 1960; however, it took Balicki and Micał many years to accomplish this goal (Zevuloni 1963). In 1970, Balicki and Micał proposed a concept to the local authorities that envisaged a social Regional Museum. The synagogue was to become the seat of the new institution, and Balicki was to be its guardian. The collection was to be made up of Balicki’s gift and objects purchased over the years by the District National Council.9 The initiators assumed that, in the subsequent years, the regional collection would be transferred to the former monastery of the Dominican Order (which required extensive renovation), and only Judaica would remain in the synagogue. The documents from that time mention that the synagogue (especially the paintings) required thorough restoration. The possibility of the new Museum being subordinated to the regional branch of the Polish Tourism and Sightseeing Society (Polskie Towarzystwo Turystyczno—Krajoznawcze; PTTK) was considered, and representatives of the Regional Museum in Rzeszów also participated in these discussions. Finally, in 1974, the city authorities transferred the right to use the synagogue to the Łańcut Castle Museum.10 In 1979, institutions involved in the creation of the future museum issued a universal appeal to the inhabitants of Łańcut and the surrounding region to donate or deposit artefacts and historical documents (Figure 7). There is no clear data as to what effects the above-mentioned action brought.

Figure 6.

A memorial plaque mounted on the west wall of the synagogue in Łańcut. The text presents a short history of the synagogue, including the role of doctor Władysław Balicki and Jan Micał in saving this monument. Photo: K. Migalska, 2018.

Figure 7.

An appeal to the inhabitants of Łańcut and the surrounding area for donations to the collection of the future Regional Museum. ACMŁ-UHD f. HM-IV-41. Courtesy of the owner.

In 1981, the Castle Museum in Łańcut officially took over the collection of the Regional Museum (about 990 objects with a total value of PLN 778.675 plus PLN 30,000 of the budget transferred by the Friends of the Łańcut Land who had been taking care of the collection so far) and decided to display them immediately in the synagogue’s women’s gallery. This set of artefacts consisted mainly of clothing, furniture, and work tools, such as sows, shovels, etc.11 Objects that would not fit in the exhibition were to be moved and put together in the castle conservatory. Until the takeover of the synagogue, the Łańcut Castle Museum focused solely on the history of the Potocki family itself and their possessions. However, due to the new acquisition, its authorities decided to expand the thematic scope of the institution. In 1980, a new Research Department on Urban History was created (including the history of Jews). The department had 2–3 employees plus one person part-time in the season when the synagogue was open for visitors.12 In 1984, the Department changed its name to “Regional Study”. According to the local press, the transition into a Judaica museum was received positively by the local community.13 In 1986, the Museum gave up its efforts to create a regional ethnographic exhibition, leaving this task to the local branch of PTTK.

Simultaneously with the creation of a new department, the Museum began to gather the collection of Judaica. These objects were not particularly connected to Łańcut or the Podkarpacie region. The collection was supposed to serve mainly educational purposes. Most of the objects were bought, as gifts and deposits were very rare. However, there were several Hebrew books from Balicki’s collection, and some objects were also included that had been found in the synagogue’s attic14. The first mention of a gift in the context of Judaica (5 objects) appeared in documents from 1988. In 1983 alone, the Museum bought 43 objects (taking the entire collection to a little over 100 artefacts).15 This number may suggest how strongly the Museum was initially involved in organizing its new branch. In the years 1981–1983, the Judaica were only exhibited in the synagogue during the summer (due to the lack of a heating system). In 1987, some of the Judaica was renovated in the Metal and Textile Conservation Studio. A few more objects underwent conservation in 1988, 1989, and 1990. In 1993, 36 elements of the Torah Ark decorations from the synagogue in Jarosław, which were previously on the inventory of the Voivodeship Movable Monuments Storehouse in Łańcut,16 were included in the collection. This set of objects was removed from the inventory of the Museum in 200517 (it was not specified to whom it was returned). In 2000, another large tranche of 24 objects was added to the collection.18 The Łańcut collection was supplemented by the Judaica deposit from the Archaeological Museum in Warsaw (Nitkiewicz 1998, p. 14).

In 1983, in addition to the Judaica exhibition (available from June to the end of March), three temporary exhibitions were displayed in the synagogue: From the History of the Łańcut Crafts (from February to June), Folk Sculpture by Izydor Błaszczak (September) and Painted Faience—From the collections of the Museum of the Kuyavian and Dobrzyń lands.19 Due to the poor condition of the interior decoration, the Museum decided to carry out a long-term, thorough renovation of the synagogue, which lasted from 1983 until 1990. Conservation work in the synagogue was carried out in several stages. First, the roof was replaced, and next, the walls were dried and secured. Simultaneously, as of 1984, conservators from the PLASTYKA Artistic Work Cooperative in Warsaw conducted thorough work on the paintings and stuccowork in the main hall and the tzadik’s room.20 During research prior to the restoration of the paintings, several layers of repainting were found, especially on the tablets with inscriptions. The most problematic task was the conservation of the decorations of the Torah ark, a commission that was originally given to one of the Museum’s employees. Work on it was only completed in 1996.21 It should be noted that the drainage system that was introduced during the works was not very effective because, as early as 2001, employees reported a problem with strong moisture in the synagogue’s walls.22 As of 1988, the interior became accessible to the public again, but only at the special request of guests. The synagogue was officially reopened in 1991 (open to visitors only between May and October), except that Judaica was not exhibited due to lack of adequate security. The 1993 activity report mentions that due to the unfinished conservation of the Torah ark, it was impossible to exhibit Judaica, but anti-burglary security had been already installed23. In 1994, employees reported that an additional PLN 100 million was needed to complete the exhibition24. Meanwhile, the synagogue was still open at the special request of visitors in the summer months, and the report mentions that this model was best suited to the needs of Jewish tourism (reports indicate that the number of tourists of Jewish origin increased strongly in 1997)25.

In the meantime, Museum employees began research into the history of the Jews of Łańcut and the development of a programme for a planned permanent exhibition in the synagogue. Ultimately, no academic study was carried out, only a small Polish-English catalogue of Judaica was published in the 1990s (Nitkiewicz 1998). The research was hampered by the fact that none of the employees knew Hebrew. From 1984, employees of the Regional Department had tried to conduct research on the developing collection of Judaica. However, as far as publishing was concerned, the only option was to outsource these works, due to the lack of qualified staff.26

The 1990s were not characterized by spectacular events in the synagogue. Reports occasionally contain information about guided school or foreign groups and small cultural events (e.g., concerts). Regular conservation of subsequent Judaica items from the collection was carried out. Finally, in 1998, the Museum opened the synagogue—complete with the Judaica exhibition inside—to the public (still only available in the summer season). The documents from 2002 contain a note about the Museum’s contacts with foreign institutions. It states that “contacts with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and exchange of publications with the Yad Vashem Institute have been maintained for a long time,”27 and that correspondence with the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington has ceased. According to the contents of the note, tourism of youth groups from Israel, as well as groups and individual tourists from other countries, developed dynamically. In 2009, the Castle Museum in Łańcut returned the synagogue to the Foundation for the Preservation Jewish Heritage in Poland (Cichocki and Litwin 2010, p. 18) (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 8.

The synagogue in Łańcut from the south-west, contemporary view. Photo: K. Migalska, 2018.

Figure 9.

Interior of the synagogue in Łańcut, contemporary view (a) of the bimah and the east wall; (b) of the bimah and the west wall. Photo: K. Migalska, 2018.

4. The Synagogue Complex in Włodawa

4.1. Jews in Włodawa

The town of Włodawa, located on the River Bug, received its municipal rights in the first half of 16th century (the privilege written in 1540 confirmed the town’s charter under the Magdeburg law). However, information about this settlement appeared as early as the 13th century. The town was in private hands for many centuries, being successively owned by influential Polish noble families: the Sanguszkos, Leszczyńskis, Pociejs, Czartoryskis, and finally, Zamojskis. Włodawa was severely damaged by the Cossacks during the Khmelnytsky Uprising in 1648 and again in 1657 by the Swedes during the so-called Swedish Deluge. The town owed its development mainly to its location on trade routes, especially in relation to the river, which was used to float numerous goods, and to fairs organized three times a year since 1726 (Piechotka and Piechotka 2019, p. 458).

The first mention about Jews in Włodawa comes from the 1530s. Initially, they did not constitute a separate kehillah but existed as the subject community to the kehillah in Brest. A privilege issued in 1684 by Rafał Leszczyński, the owner of the town, authorizing the construction of a synagogue and houses on designated plots, led to the creation of a relatively homogeneous Jewish district southwest of the town’s market square (Piechotka and Piechotka 2019, p. 458). As of the late 17th century, the Jews were allowed to build and buy houses anywhere in Włodawa, and as a result, in the second half of the 18th century, all real estate in the area of the town’s market square belonged to Jews. At that time, the community owned a cemetery, a hospital, a bath house, and a brewery. At the end of the 18th century, Hasidism appeared in the city. The number of supporters of Hasidism in Włodawa increased throughout the 19th century, but instead of creating one compact community, they gathered in smaller groups faithful to individual tzadikim. As a result of the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Napoleonic Wars, Włodawa became a border town (the Bug river became a border between the semi-autonomous Kingdom of Poland and the territories directly incorporated into Russia). In the 19th century, the town of Włodawka lay parallel to Włodawa, on the right bank of the Bug river, with a separate Jewish community and synagogue. After the defeat of the Polish November Uprising in 1831, the Russian authorities introduced a ban on Jewish settlements in border towns. Although the ban also applied to Włodawa, the number of Jewish residents in the town increased regularly until the 1860s, when Jews constituted 80 per cent of the total number of citizens (Wojczuk 1996, pp. 4–6). This situation persisted in the interwar period (5363 out of 8592 residents in 1931). Mostly unassimilated, the Jews of Włodawa owned over 90 per cent of the town’s industrial and commercial enterprises. Despite six registered Jewish political organizations, the vast majority of Jews remained politically inactive. During the Second World War, the Nazi occupiers established a closed ghetto for the Jewish residents of Włodawa. Most of the Jews were transported to the Death Camp in Sobibór in 1942–43 and murdered there (Makus 2014, pp. 19–20). A few Włodawa Jews who survived the war returned to the town and tried to rebuild their former lives, but they encountered hostility and aversion from their fellow citizens (Cieślińska-Lobkowicz 2010, p. 106). According to the census of 1946, out of 4400 Włodawa citizens, only 40 were Jews (Kurczuk 1998, p. 91). Although there are no clear records as to the time and circumstances, most of them probably left Włodawa over the following years. In 1957, a citizen of Włodawa named Kunegunda Giejer (probably of Jewish origin) appealed for measures to be taken against the devastation of the Jewish cemetery where her husband had been buried since 1952 (Urban 2006, p. 505). This may indicate the constant presence of a few Jewish citizens in Włodawa at that time.

4.2. Synagogues

The masonry synagogue, which is the subject of this study (also called the Great or the Old Synagogue), was erected in the 1760s following a permit issued in 1764 by Jan Jerzy Fleming, who was, at that time, the owner of Włodawa. The building that previously had served as a place of prayer for the local Jewish community was probably wooden, and it was erected as a result of the privilege of 1684. When, in 1771, Włodawa was inherited by the Czartoryski family, construction works in the synagogue were probably still ongoing. Existing archives (The Book of Catholic Parish in Włodawa) indicate that the building was erected during the reign of the Czartoryski family and with their considerable (probably mostly financial) participation (Wojczuk 1996, pp. 4–6). The shape of the newly built prayer house suggests that it was designed by a talented architect with a refined aesthetic sensibility (Jerzy Baranowski pointed out that the architectural detail could be inspired by the decorations of the nearby Pauline church in Włodawa, and even suggested that Paweł Antoni Fontana, the architect of the church himself could be responsible for its design) (Baranowski 1959, pp. 59–60). The building of the synagogue consists of a high—ceilinged men’s hall constructed on a rectangular plan with nine-field vaulting, two low longitudinal women’s galleries on the north and south of the men’s room, and a rectangular two-storey vestibule flanked by two corner pavilions on the west side (Figure 10a,b). This spatial arrangement of the western part of the building was characteristic of eighteenth-century wooden synagogues erected in the eastern lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Transferring this solution to masonry construction makes the synagogue in Włodawa the oldest of that type (used in later years in Illitsi, Khmelnyk, Pavoloch [today Ukraine], Krynki [today Poland], and Shklow [Belarus]) (Kravtsov 2018, p. 120). The oldest known depiction of the building, painted by Kazimierz Stronczyński, is dated to the mid-nineteenth century and shows the synagogue from the south-east, revealing one of the women’s galleries crowned with a decorative attic (Figure 11). Based on this image, Jerzy Baranowski concluded that the second floor of the vestibule was built in the second half of the nineteenth century, indicating that the picture does not show the roof of the second storey. Maria and Kazimierz Piechotka drew even more far-reaching conclusions, stating that not only the second floor of the vestibule but also both pavilions were added in the mid-nineteenth century (Piechotka and Piechotka 2019, pp. 454–58). This erroneous conclusion is refuted by the Pinkas of Włodawa Jews quoted in the Yizkor book, according to which, in 1774, the northern alcove was intended for the assembly of tailors, and the southern for the shoemakers (Kanc 1974, p. 55).

Figure 10.

Plan of the synagogue in Włodawa (a) at ground level; (b) at the height of the windows of the men’s room (Piechotka and Piechotka 2019). Used by permission.

Figure 11.

K. Stronczyński, View of the Synagogue in Włodawa from the South-East, ca. 1850, watercolor on paper. Cabinet of Engravings, University Library in Warsaw. Courtesy of the owner.

Stronczyński’s picture of the Great Synagogue shows another building owned by the kehila of Włodawa. It is the Small Synagogue (also called the “Old Beit ha-midrash”), located northeast of the Great Synagogue. This masonry prayer house was first mentioned in documents in 1786. The building depicted in Stronczyński’s watercolour differs from the modern one in both the size and shape of the doors and windows. This is probably the result of a reconstruction that took place during World War I (1915–16). The Small Synagogue consists of a men’s hall constructed on a rectangular plan and a two-storey vestibule added from the west. The men’s room was richly decorated with paintings around 1930 (Nastaj 1998, pp. 16–17). In the late 1920s, the Jewish community in Włodawa erected the third building, commonly called the “New Beit ha-midrash”, which consisted of a ground floor with an attic, originally divided in the lower storey into two rectangular rooms. According to the text on the foundation stone, the new Prayer house was built in 1927 or 1928 (Wojczuk 1996, p. 17).

Prior to World War II, the Great Synagogue was partially destroyed at least twice in the 20th century. The first incident took place during World War I, when a fire damaged the building. The damage must have been significant because the synagogue remained closed until its renovation in the 1920s (Gałecka 2012, p. 25). During this renovation, the Torah Ark was rebuilt (Yaniv 2017, p. 138). In 1934, a fire broke out once again inside the men’s hall, resulting in the destruction of its wooden furnishings, including—one more time—the monumental wooden Torah ark. This catastrophe forced Włodawa’s Jews to renovate the synagogue thoroughly, during which minor changes were made in the western part of the building, and the interior decorations were refreshed. The former Torah ark was a three-span, two-storey structure with a high extension, richly decorated with floral and symbolic motifs. The new structure, created in a sand-lime coating with plaster casts, referred in composition to the previous wooden one. The inter-war images of the western facade of the synagogue show a simplified attic located above the second floor of the vestibule. This decoration was probably destroyed during World War II because it is no longer visible in post-war photos. During the Nazi occupation, the kahal buildings were turned into military warehouses. The furnishings and decorations of the interior of the Great and Small Synagogues, including the bimahs, were destroyed (Nastaj 1998, p. 17; Wojczuk 1996, pp. 8–9) (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Interior of the Great Synagogue in Włodawa transformed into a magazine, 1944. Print from a glass negative. ŁWLMW-HD inv. No. H/IV/140. Courtesy of the owner.

The warehouse function of the buildings of the synagogue complex was maintained after the war—it was handed over to the Communal Cooperative “Samopomoc Chłopska”, despite the fact that after the war, Jewish survivors returned to Włodawa and tried to rebuild social and religious life as much as possible. According to data contained in archival administrative letters, in 1945, there were “about 200 inhabitants of the Mosaic religion” in Włodawa, while in 1946, this number had already dropped to 40, before slipping to a mere 10 in 1947. The decreasing Jewish community gained the opportunity to use the cemetery at Mielczarskiego street and one of the three synagogue buildings for religious purposes. It is not specified which building it was; however, it is known that the district administrator intended to establish a municipal cinema and theatre in one of the other two synagogues. In May 1946, the building used by Włodawa Jews was unlawfully taken by the local Committee of the Polish Workers’ Party (the communist party), a move which forced the Jewish Committee in Lublin to intervene. Although local and provincial authorities argued that it was necessary to occupy all three synagogues due to current housing needs, eventually, in 1947, the Department of Religious Affairs at the Ministry of Public Administration decided to leave one of the synagogues in the hands of local Jews. However, by that time, the number of Jewish residents of Włodawa was minimal (Urban 2006, pp. 126–28; Kurczuk 1999, pp. 27–28). In the “List of Synagogues Improperly Used”, that was prepared by the Jewish Socio-Cultural Association in 1951, the Great Synagogue was mentioned together with the information that the roof of the building was destroyed (Urban 2006, p. 327). In the same year, it underwent renovation to prevent further degradation; however, repairs were probably only superficial. In the same year, all three buildings were entered into the National Register of Historic Monuments,28 although, until the early 1970s, they were still used for storage and commercial purposes. On 22 May 1964, a great fire consumed a large number of the wooden buildings (about 80) in the centre of Włodawa, including the immediate neighbourhood of the synagogues.29 In the 1970s, a housing estate of modern apartment blocks was erected in place of the buildings destroyed in the fire, which caused a complete transformation of the cultural landscape around the synagogue complex (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Construction of a new housing estate on the site of buildings destroyed in the great fire of Włodawa in 1964. In the background on the right, the Great Synagogue is visible, 1980s (Danilczuk 2015, p. n.n.). Used by permission.

4.3. Museum in the Synagogue

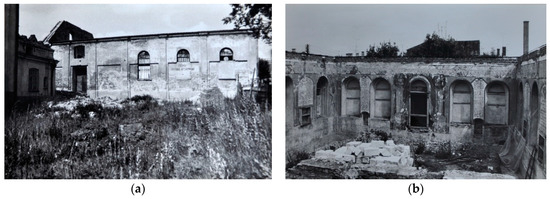

In 1969, the District National Council in Włodawa decided to carry out a major renovation of the Great Synagogue, so as to use the building as a museum. However, renovation works were not carried out until 1979 and duly lasted until the end of 1982 (Figure 14). The idea to create a museum in the synagogue was, one can say, a “need of the moment”—it appeared because the town council of Włodawa acquired an ethnographic collection and needed a place to display it. The Museum was created in 1981 and officially opened as the Museum of the Łęczyńsko-Włodawskie Lakeland District—an ethnographical museum—in July 1983. From the beginning, the institution had three substantive departments: ethnographic, historical, and educational (a total of six employees) (Muzeum 1994). Only the Great Synagogue was restored at that time, renovation of two other buildings did not begin until the late 1980s. The Small synagogue wasn’t open for public until 199930. (Figure 15 and Figure 16).

Figure 14.

The Great Synagogue in Włodawa under renovation (a) view from the west (on the left part of the Small Synagogue is visible) (b) view from the south, 1980s. Photo: Cz. Danilczuk. Used by permission.

Figure 15.

The Small Synagogue in Włodawa before renovation (a) view from the south (b) interior, view from the west, 1986. ŁWLMW-HD f. Włodawa. Studium urbanistyczno-historyczne miasteczka żydowskiego. Dokumentacja historyczna. Courtesy of the museum.

Figure 16.

Prayer house in Włodawa (a) during renovation, view from the south, 1986; (b) after renovation, view from the south-east, 1990. ŁWLMW-HD f. Włodawa. Studium urbanistyczno-historyczne miasteczka żydowskiego. Dokumentacja historyczna. Courtesy of the museum.

The theme of the first permanent exhibition in the newly opened institution was the history of regional fisheries. However, in the same year, the temporary exposition From the History and Culture of Polish Jews was opened. It was organized “due to the 40th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto’s liquidation in 1983, and the history object in which it is located.”31 The exposition consisted of over 70 objects loaned from several museums (including the Kraków Historical Museum) (Figure 17). The exhibition was accompanied by a small catalogue, created with the substantive help of Eugeniusz Duda, an employee of the KHM. It should be mentioned that one of the branches of the KHM was the Old Synagogue in Krakow, and that it was—alongside to the Jewish Historical Institute—the only museum institution in the People’s Republic of Poland focused solely on exhibiting and studying Judaica and the history and culture of Polish Jews. In 1989, a small exhibition of Judaica was organized as a foretaste of the permanent exhibition in the vestibule of the Great Synagogue. In the same year, Museum staff co-organized the so-called “Judaic Days” in cooperation with institutions from Chełm and Lublin.32 The first permanent Judaica display was opened in 1990, until then, the Museum had already organized five Jewish history and culture-related temporary exhibitions (Figure 18). Judaic expositions were and still remain only one of the fields of the Museum’s exhibition activity (Figure 19). Almost from the very beginning, the museum pursued three thematic directions at the same time: expositions about the history and folk culture of the region, broadly understood Jewish topics, and a series of exotic exhibitions about various cultures from around the world.

Figure 17.

Catalogue of the first temporary Judaica exhibition, which took place in the Great Synagogue in Włodawa in 1983/84. ŁWLMW-HD f. NW-1984-1. Courtesy of the museum.

Figure 18.

Photographic documentation of the exposition titled Synagogue-the assembly house, exhibited in the vestibule of the Great Synagogue in Włodawa, 1986. ŁWLMW-HD. Courtesy of the museum.

Figure 19.

Interior of the Great Synagogue in Włodawa before the reconstruction of the bimah, 1990. ŁWLMW-HD. Courtesy of the museum.

At least since 1992, the Museum took efforts to facilitate visits of multilingual groups (guidebooks have been issued in Polish, English, French, and German).33 In 1993, the newly created Museum of the Former Nazi Extermination Camp in Sobibór was subordinated to the Łęczyńsko-Włodawskie Lakeland District Museum and remained in this form until May 2012, when the institution in Sobibór became a branch of the State Museum at Majdanek (Muzeum 1998, pp. 3–4). In the 1990s, the employees of the Museum were very active in research and education in the field of Jewish culture and history, especially through numerous temporary exhibitions. While conducting these projects, the institution repeatedly cooperated with Polish specialists in the field of Jewish Studies. Since 1994, the Museum has been publishing (with varying frequency) a journal called Zeszyty muzealne, in which many articles about Włodawa Jews have been printed so far. An attempt was also made to translate the Yizkor book of Włodawa Jews into Polish. Although the project was not completed, a number of articles by Krzysztof Skwirowski based on the contents of the Yizkor book were published in the journal (e.g., Skwirowski 1996).

The Museum in Włodawa began to gather its own Judaica collection shortly after the opening. The first objects—eight silver Kiddush cups and glasses—were purchased in 1984. The whole collection (over 200 objects, around half of them gathered by the end of the 1980s) came mostly through purchases, and only a few pieces joined the collection as gifts.34 Each time before buying a given object, the Museum requested a substantive review to the National Museum in Warsaw (each time an opinion was issued by Ewa Martyna, an art historian responsible for the collection of items of artistic craftsmanship, including Judaica) or the ŻIH.35 All new acquisitions for the Museum were bought through the District Museum in Lublin (by the Joint Purchasing Commission, together with the Regional Museum in Chełm). The application of this solution has become problematic over time, as the museum in Chełm began to claim rights to the objects purchased for the collection of the museum in Włodawa.36 In contrast to other sectors of the collection (e.g., ethnographic), the Judaica purchased by the Museum were not selected on account of local origin. The decisive factors in purchasing the Judaica were market availability and price. As a result, this section of the collection, unlike the others (e.g., ethnographic), is not directly related to the history of the region. The exception is the so-called “Włodawa treasure”—over 20 items that had been found buried during excavations on one of the town’s streets. Among others, these were Kiddush dishes, two Sabbath candlesticks, chanukiah and balsamine. Due to their poor condition, they have been professionally restored and included in the Museum’s collection (Skwirowski 1995, p. 53) (Figure 20).

Figure 20.

(a) The so-called “Włodawa Treasure” before the renovation, ca 1995. ŁWLMW-HD file not numbered. Courtesy of the museum; (b) “Włodawa treasure”, currently exhibited in the Great Synagogue, 2018. Photo: K. Migalska.

In 1995, the Museum organized the Festival of Three Cultures for the first time, celebrating the historical multiculturalism and ecumenism of Włodawa.37 Initially conceived as a strictly musical event (the first festival was entitled the Festival of Sacred Music “Music of Włodawa”), since 1999, this festival has been organized annually and has become the largest cultural event in the town, contributing to its development as a tourist destination. At the beginning of the 21st century, the Museum was a dynamically developing cultural institution. In addition to ongoing projects, employees have been involved in the organization of cyclical events: the Festival of Three Cultures and the Cross-Country Race in memory of the victims of Sobibór. They have regularly published Zeszyty muzealne and prepared exhibitions and educational classes on the history and culture of the region, Jewish history, and the Holocaust. In 2000, the Museum was honoured with the Snowdrop ‘99 award (for providing the most interesting programme for tourists), the title Tourist Attraction of the Year, and a diploma of recognition of the State of Israel for activities aimed at protecting Poland’s Jewish heritage. In the same year, a new permanent exhibition was opened at the Museum of the Former Nazi Death Camp in Sobibór entitled Sobibór—the Death Camp.38 Since 2001, the Museum has been the owner of three usable historic buildings (Figure 21, Figure 22 and Figure 23). The general nature of the cultural activities undertaken by this institution has not changed to this day.

Figure 21.

The Great Synagogue in Włodawa, contemporary view (a) from the north-west; (b) interior, view from the west women’s gallery. Photo: K. Migalska, 2018.

Figure 22.

The Small Synagogue in Włodawa, contemporary view (a) from the north-east; (b) interior, view from the women’s gallery. Photo: K. Migalska, 2018.

Figure 23.

Prayer house in Włodawa, contemporary view from the north-east. Photo: K. Migalska, 2018.

5. The Museums in the Synagogues in Łańcut and Włodawa: Similar Yet Different

Although both Judaica museums—in Łańcut and Włodawa—started their activities around the same time, they have more differences than features in common, and there are at least several reasons for this state of affairs. As a result of the country’s borders shifting after World War II, both towns “changed their place” on the administrative map of Poland. However, the changes related to this fact became particularly noticeable in Włodawa, which suddenly became a border town again (the Bug River became the new border between Poland and the Belarusian Soviet Republic), Łańcut was thus “pushed” deeper into the eastern province. In both towns, there have been drastic changes on the demographical, socio-economic, denominational, and national levels. Whilst only its Jewish inhabitants disappeared from Łańcut, shortly after the war, all Ukrainian residents were forcibly displaced from Włodawa. The few Jews who returned to the town, soon left it irrevocably, unable to live a normal life there. Włodawa was, therefore, doubly robbed of its multiculturalism. Reports on the aggressive behaviour of Poles towards Jews returning to Włodawa indirectly explain why the synagogue ceased to serve commercial purposes and was only turned into a museum in the 1970s. Simultaneously, although Balicki and Micał started their fight for the synagogue in Łańcut in the early 1960s, we cannot be sure that in the post-war years there were no antisemitic sentiments, similar to those in Włodawa, among the Łańcut community. It is worth noting, however, that although none of the Jewish inhabitants of Łańcut returned to the city permanently, members of the Association of Former Residents of Lancut in Israel and USA must have had some contact with their hometown, since information on the plans to transform the synagogue into a museum appeared in the Yizkor book. Perhaps the contact channel was Balicki himself, since he openly acknowledged that the purpose of his initiative was to commemorate the Jews of Łańcut murdered during World War II, many of whom were his personal friends (Zevuloni 1963, p. LV). Contacts between the Museum in Włodawa and the Association of Jews from Włodawa were probably not established until the early 1990s (Skwirowski 1996, p. 33).

But what was the level of the synagogue’s visibility in the post-war, altered and homogenous landscape of Łańcut and Włodawa? Referring to the case of Łańcut, Sławomir Kapralski described the virtual “shift” of the synagogue’s place in the landscape, which took place after the disappearance of Jews from the town. He correctly noticed that the Jewish house of prayer, being in the immediate vicinity of the Potocki Palace and the town square, automatically situated the Jews between the owner and the town’s inhabitants (Kapralski 2001, p. 39). In fact, the synagogue stands slightly closer to the palace grounds, which could suggest that the Jews were closer to it, closer to power, perhaps even under its protection. This arrangement certainly symbolically appeared (or re-appeared) when the Castle Museum took over the synagogue. This time, however, it was absorbed—the synagogue ceased to be an independent structure and became one of the museum buildings. In Włodawa, the process of change was completely different. In Łańcut, the palace is and always has been a clear dominant feature in the landscape, while the centre of Włodawa is plainly dominated by the Great Synagogue, which stands closer to the town square than the Greek Catholic church, hidden among the trees, and definitely closer than the Roman Catholic church. This domination was only slightly levelled by a housing estate erected on the west side of the synagogue complex. In Włodawa, the synagogue could not be passed by unnoticed. Perhaps, because of that, transformation into a museum was a way to tame it in the context of the town’s landscape. In the ‘1970s and 1980s, a museum—especially in the depth of the Polish provinces—was not associated with a critical institution, but rather with dirty display cases and safe artefacts. It is possible that, in this case (or maybe in both cases), the project of transforming a Jewish prayer house into a museum institution was eagerly accepted by the local society because it had a calming effect on the collective conscience.

Whatever impact these synagogues would have on the local population, the most important for the context of this article is how the two institutions operated. Again, the two case studies differ from each other. The Włodawa Museum has adopted a more active model. In the first stage of its existence (the 1980s), it was mainly characterized by the organization of relatively numerous temporary exhibitions on various subjects (each time accompanied by educational leaflets) and cultural events such as concerts or lectures. Since the beginning of the 1990s, the Łęczyńsko-Włodawskie Lakeland District Museum has been trying to keep up with the growing needs of domestic and foreign tourist traffic, for example, by expanding its educational programme or organizing the Festival of Three Cultures. As a result, after 20 years of existence, it had become one of the most dynamically operating museum institutions in the region. Meanwhile, the museum in the synagogue in Łańcut developed according to a more conservative model: every year in the spring and summer season the exhibition of Judaica was made accessible, often accompanied by a small temporary exhibition. The employees focused primarily on developing collections and caring for the condition of the synagogue. The actions of the Łańcut institution lacked momentum in comparison with the Museum in Włodawa. This was primarily due to the internal structure of the Castle Museum—the activities of the Regional Department were peripheral to the role of the Palace itself, while in Włodawa, this problem did not occur.