Abstract

The remoteness of Galicia, a cultural and linguistic bridge between Portugal and Spain, did not prevent it from playing a significant role in the history of female architects in the Iberian Peninsula. Nine Galician pioneers have carved the path since the first generation of Spanish female architects outlined the precedents during the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939). They were also present in an initial period, even if housewifization theories were intensively fueled by the dictatorship (1939–1975); likewise during the continuity period in the transition to democracy (1975–1982), and the second wave of feminism. However, it would not be until progressive democratic institutionalization (1982–1986) that more women gained access to architectural studies in university (consolidation period); but what is the legacy of these pioneers? Are Galician female architects ‘in transition’ yet? Based on data primarily collected by research group MAGA and released publications, this piece explores how, despite their achievements, their recognition is still superficial. And even if the number of undergraduate students reached quantitative equality, female practitioners continue to leave architecture and these numbers are increasing. Towards a critical approach to inequality in the profession, this article researches the history—and stories—of Galician female architects to examine how far we are from effective equality in the Galician architectural world.

1. Introduction

Galicia has a peripheral position in the southwest of Europe. Under its current status as an autonomous region and historic nationality, it has particularities of an edge territory that represents a geographical, cultural and linguistic bridge between Portugal and other Spanish regions. Unexpectedly, this remoteness did not prevent it from playing a significant role in the history of female architects in the Iberian territory.

As Zaida Muxí Martínez (2013) has pointed out on many occasions, women have always been present in the architectural world, defining and building spaces, in the form of clients, advisors, decorators or theorists—including self-builders—even if they were forbidden from accessing architectural schools and formal practice. Nevertheless, they have remained invisible in the hegemonic narratives of history, especially in Spain, where official records begin well into the twentieth century.1 Specifically, in 1929, women gained access to the School of Architecture in Madrid for the very first time, and this includes the first Spanish female architect, Matilde Ucelay Maórtua. In 1930, María Cristina Gonzalo Pintor from Cantabria, and Rita Fernández Queimadelos from Galicia followed in her footsteps.2 The three graduates—Ucelay Maórtua in 1936; and Gonzalo Pintor and Fernández Queimadelos on 12 and 26 August 1940, respectively3—trained during the thirties, and represent the first generation of female architects in Spain.

Aside from this group of Spanish pioneers, there is another, scattered between 1949 and 1960 (Carreiro Otero and López González 2019; Vílchez Luzón 2013). This one incorporates women that enrolled in architecture before the shift in university legislation in 1957 (Carreiro Otero and López González 2016a), which significantly changed the structure of architectural and engineering studies; Juana de Ontañón Sánchez–Arbós (1920–2002), who graduated in 1949, was followed by Margarita Mendizábal Aracama in 1956, María Eugenia Pérez Clemente in 1957, Elena Arregui Cruz-López in 1958, and Milagros Rey Hombre in 1960.4 From this last group, Arregui Cruz-López and Rey Hombre would also go on to develop their careers in Galicia.

Thus, after Rita Fernández Queimadelos opened the path, eight more Galician pioneers followed in her footsteps. All these women, who got the equivalent of a Master of Science in Architecture5 became the first female professionals in their area, and Galicia is the common thread; the place where they were born and work, or where they have been living and work. Their names—which have been highlighted since 2012 by the research group MAGA6—are already known. The periods are also established and after the precedents, the initial, the continuity and the consolidation stages emerge. The first seven can be framed in the first and second generation of Galician female architects, working mostly (but not only) during the dictatorship and in the transition to democracy. The last two represent pioneer figures in the political sphere during the first years of the restored Spanish democracy, when this role could also be an option. They are representatives of a more consolidate third generation, where female architects were no longer an exception, but still a minority.

Through their lives and accumulated experience, we can see the sudden change from the initial democratic experience to the dictatorship, and then the slow transition to democracy again. The ultimate goal is to make the history (and stories) of Galician female architects visible, in order to move towards a more human, more just and more egalitarian profession. How relevant was their contribution to the development of the profession? Can we properly speak about the feminization of first the studies of architecture, and then the field? Did the creation of the only existing Galician public School of Architecture in 1973 in A Coruña7 have an impact? From the precedents to the consolidation stage, this article comprises a chronological frame of more than 50 years where Galician female architects, influenced by their socio-political context, transitioned from a situation of severe inequality to the stabilization of an effective change.

Spanish democracy was in transition, but was the querying of an ancestral patriarchal profession such as architecture in transition too? The main aim of this work is to answer these questions while giving value to the different generations of female architects from Galicia, who paved the way so others can also undertake it today.

2. Precedents Outlined during the Democratic Experience in the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939): Rita Fernández Queimadelos among the First Generation of Women at the University Studies in Architecture in Madrid

The history of Galician female architects gradually consolidates from a clear starting point when a vanguard of a young woman—winner of an extraordinary prize at high school—was determined to study architecture under the umbrella of the advancement of women’s rights during the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939). Rita Fernández Queimadelos (1911–2008) was originally from the aldea of A Torre, in the municipality of A Cañiza, in the province of Pontevedra. In the academic year 1930–1931—in alliance with both her grandmothers, and despite her father’s initial opposition—at the age of 19, she finally gained access to the closest school in Madrid, one of only two existing schools of architecture in Spain.8 She lived among many other female university students in the Residencia de Señoritas, directed by the feminist intellectual María de Maeztu. Her brilliant academic success almost led her to finish her studies faster than the average student. Her studies were interrupted when the coup took place in July 1936. Despite the difficulties she faced, and the subsequent three years’ war, in 1940 she became the third woman to graduate as an Arquitecto9 (López González et al. 2017). She acquired her license10 in 1941, and became the first female architect to officially sign her own architectural projects in the state.11 In 1942 she married Vicente Iranzo Rubio, her boyfriend since her student days, with whom she had six children,12 combining family and a professional career with the boundless help of her close family, particularly her sister and her parents.

Rita Fernández Queimadelos had a prolific career practicing architecture. First, and thanks to the offer of one of her professors, in the Department of Devastated Regions (Dirección General de Regiones Devastadas, DGRD) in the post-war period (1940–1948), she single-handedly designed a total of 16 projects (López González et al. 2017). Eight years after giving birth to her third child and leaving her job, she opened her studio in Murcia (1955), and worked there as a provincial architect building schools (1960–1967) and as a municipal architect in Mula (1962–1967). She had previously declined to direct the Fundación del Generalísimo, recompiling the craftwork of regions across Spain, by declining the requirement to become a member of the Sección Femenina, the women’s branch of the Falange13 in Spain. Following her daughter’s words, while working in Murcia, she pursued her wish to improve people’s access to education. She resolutely fought against corruption in a time when money for elementary schools (called unitarias) mostly ended up going towards building the villa of the developer or the mayor of the town (Carreiro Otero and López González 2016b). It was a hard job to defend the public service and its democratic values, where she threatened to resign many times after extreme situations, even if she eventually never did. After completing this task and fulfilling some direct commissions, Rita Fernández Queimadelos retired in the mid-1970s at the age of 62 in Barcelona. There, she passed away at the age of 97.

3. Exceptionality during the Housewifization Fueled by the Dictatorship (1939–1975): Elena Arregui Cruz-López and Milagros Rey Hombre in the Initial Period

As Franco established his dictatorial regime for almost 40 years, non-democratic, inequitable and authoritarian-type values such as submission, abnegation or devotion were promoted by the Sección Femenina of Falange, in alliance with the Catholic Church, in Spain. The feminine organization led by Pilar Primo de Rivera, contributed to the ideological mission of the dictatorship under its formative role through the so-called Women’s Social Service from 1937 to 1978.14 This was mandatory for every Spanish woman (Rebollo Mesas 2001). Just to give an example, the indissolubility of marriage—just upon death—and the patriarchal understanding of “head of the household” or “parental authority”, did not disappear from the legislative framework until the decade of the 1970s. This formalized legal and civil inequality based on sex until the last third of the twentieth century in the state.

The phenomenon of promoting a woman’s role as angel del hogar, the angel in the house, in connection with the Nazi stereotype kitchen, küche, kinder or kitchen, church and children, is not something new, but presents a remarkable continuity during the twentieth century in Spain. The sexual division of labor was fueled during the dictatorship, in the post-war reconstruction and then, during the transition to modern capitalism. As Maria Mies has observed “international housewifization was the theoretical device that contributed to devaluing women’s work and to ‘construct’ them internationally as cheap labor” (Mies 1998, p. 3), explaining how:

The policy of defining women everywhere as dependent housewives, or the process of housewifization, is identified as the main strategy of international capital to integrate women worldwide into the accumulation process. This implies the splitting up of the economy and the labor market into a so-called formal, modern sector, in which mainly men work, and into an informal sector, where the masses of women work who are not considered to be real wage-workers, but housewives.(Mies 1998, p. 4)

In this context, the option of studying and practicing a liberal profession, such as architecture, was not considered suitable for any woman, and only a few determined and privileged ones could effectively succeed. As we have seen, just five women were studying architecture in Madrid before the coup and in the next twenty years five more would join them and, in the 1960s, figures remained very low (Sánchez de Madariaga 2009, 2010). Still, we can find Galician pioneers in the initial period; two decades after Rita Fernández Queimadelos, Elena Arregui Cruz-López in 1958, and Milagros Rey Hombre in 1960, will graduate also in Madrid.

Elena Arregui Cruz-López (1929–2018) was originally from Irún (Guipúzcoa, Basque Country), but developed her professional career in Santiago de Compostela. In her own words, she never forgot what she was told when she went with Matilde Ucelay to ask to be admitted into the best private academy to prepare the architectural drawing entry exam: “here women are not admitted to prepare architecture: nor they work, neither they allow others work” (Carreiro Otero and López González 2016b, p. 65). Instead of being discouraged, they went to a second one, and there she could start working. After graduating as the seventh female Spanish architect in 1958, she married the Galician-born architect, Arturo Zas Aznar and became a mother of four.15 Elena Arregui and her husband took up residence in Galicia from 1962. She registered that year in Galicia and developed her career, mostly in partnership with Arturo Zas, but also alone when he was absent. Their practice covered a wide range of architectural projects, including large facilities such as the Paulist School in Marín (1970), one of the projects which she liked the most (Figure 1). In the 1990s, they completed the architectural complex by adding a sports hall. Around this time, they closed the office in Compostela, and she started her fight to receive a retirement pension in the same way as her husband.16 Elena Arregui was the first female architect to hold a management position in the Galician Association of Architects (COAG), when she became the president of the delegation of Santiago de Compostela in its foundational year in 1977. In 2002, on the 25th anniversary of the institution, she received an honorary diploma, and in 2003, she was awarded the Castelao Medal by the Xunta de Galicia. The Castelao Medal is the highest award of the Galician government to honor the people and institutions that have created exceptional work in any field that is worthy of distinction. Elena Arregui Cruz-López passed away in 2018.

Figure 1.

Paulist School in Marín (Marín, Pontevedra, 1970), by Elena Arregui Cruz-López and Arturo Zas Aznar. Photo credit: María Novas.

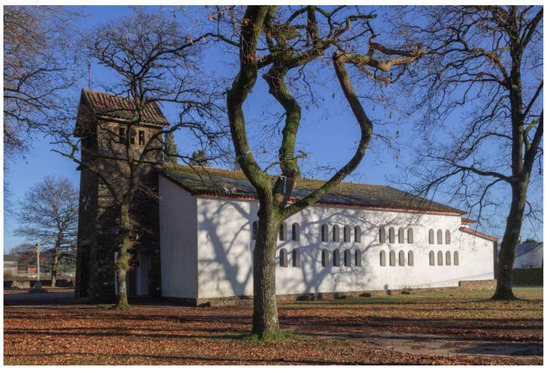

Milagros Rey Hombre (1930–2014), affectionately known as Lalos, got her masters in 1960, and in 1961, became the first licensed female architect in Galician territory.17 For circumstantial reasons, she was born in Madrid,18 but she developed her career in A Coruña. She did not marry, nor did she have children, and she remained completely dedicated to her profession as an independent practitioner and a professor. She steadily worked both as an independent practitioner and as a civil servant at the City Council of A Coruña, where she was the municipal architect between 1961 and 1974. During this period, she had many conflicts with builders that did not respect her as a public authority figure; in one case one of them decided not to pay attention to her command to stop construction and avoid the collapse of a building. Considering the safety risk, she had to call the police and he was arrested (Carreiro Otero and López González 2016b, pp. 96–97). Milagros Rey worked on many projects during her career, including single and multi-family housing, urban-development, and urbanization projects, from 1961 to 1987. She also designed many interesting churches, such as the parish church Santa María de Deixebre (Deixebre-Oroso, A Coruña) in 1963 (Figure 2), probably due to her proximity to the archbishop of Santiago de Compostela, Fernando Quiroga Palacios. The Social Space for Fishermen in Finisterre (1963) is one of the projects she did as a liberal professional and she was most proud of. Fishermen, who had applied for funding, and the public institutions assented, under the requirement that they had to provide the labor force. Their wives, daughters and cousins assumed the construction, so as to not interrupt the fishermen who worked during the night. Under the direction of Milagros Rey Hombre and the assistance of a young building surveyor, the women from Fisterra built the whole social space. Milagros Rey Hombre did not only have a prosperous and singular career completely of her own but was also the first woman professor at the EUAT in A Coruña (University School of Building Surveying, 1974–2001), where she held the chair of Architectural Construction in 1989. Between 2002 and 2008, she was acknowledged as Emeritus Professor at the University of A Coruña, and in 2005 she also received the Castelao Medal from the Galician government.

Figure 2.

Parish Church Santa María de Deixebre (Deixebre-Oroso, A Coruña, 1963), by Milagros Rey Hombre. Photo credit: María Novas.

4. First Declared Feminist Concerns in the Transition to Democracy (1975–1982): Myriam Goluboff Scheps, Pascuala Campos de Michelena, María Jesús Blanco Piñeiro and Julia Fernández de Caleya Blankemeyer in the Continuity Period

A scarcely bigger number of Galician female architects graduated since the late 1960s—from 1966 to 1975—and were actively working during the 1970s. After Franco’s death in 1975, social protests opposing the dictatorship were finally free to be out on the streets and, in the late 1970s, the so-called second wave of feminist movement in Anglo-Saxon studies also reclaimed its space. The vindication of women, in the form of protests, magazines and academic research, flourished after some foundational texts on gender theory were translated to Spanish (Pérez Moreno 2016). In this period, the first Galician female architect formally ascribed to the feminist movement raised her voice. However, on the other hand, the exclusivity of architectural studies will continue to be a matter of fact, even if numbers minimally increase. So, in this time-frame, the strategies of survival in the footsteps of their predecessors to practice architecture persisted; working as part of the public administration combined with occasional requests (Rita Fernández Queimadelos, Milagros Rey Hombre), or entirely self-employed as part of a gender-mixed team (Elena Arregui Cruz-López). Although nuanced, this last case will represent the initial situation of all female architects that delineate the continuity period in Galicia: Myriam Goluboff Scheps, Pascuala Campos de Michelena, María Jesús Blanco Piñeiro and Julia Fernández de Caleya Blankemeyer.

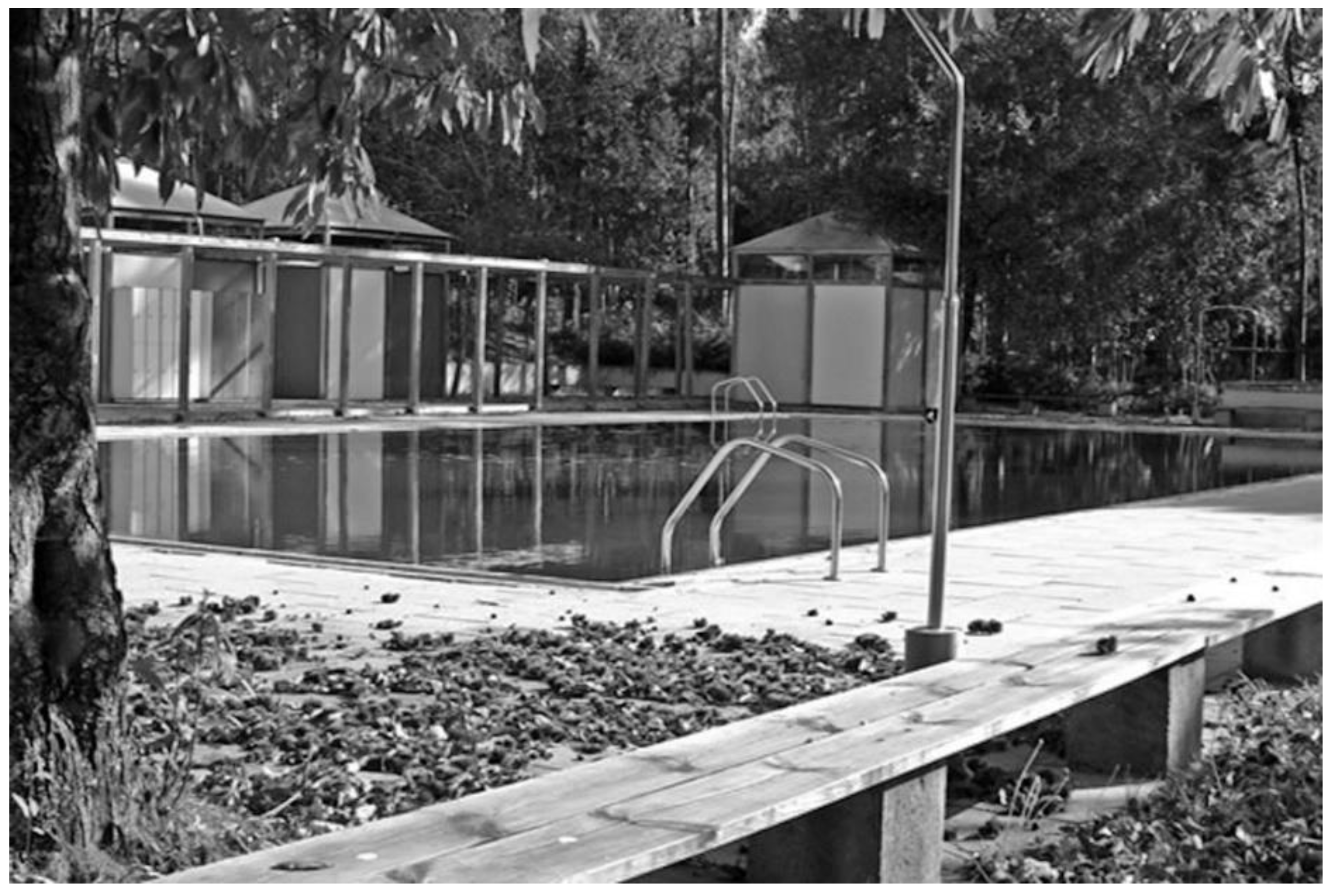

Myriam Goluboff Scheps (1935) graduated in Buenos Aires in 1965 and established herself in Galicia in 1975 with her husband and partner (of Galician descent) Mario Soto, and their son.19 Mario Soto was an active political militant of leftist revolutionary movements who suffered the repression of the Argentinian government at that time (including one year in jail), and even if he wanted to wait until Franco’s death, finally they decided to move to Spain anyway (Goluboff Scheps 2009). Myriam Goluboff practiced architecture in A Coruña from that very moment, first as part of the mixed-gender team and then, after the untimely death of her partner in 1982, independently. She worked in Galicia from the end of the 1970s until the early 2000s. The Area of Leisure and Swimming Pools in Cesuras (A Coruña, 1997) is one of her most representative projects where, using modules, she sought to integrate architecture into an outstanding natural setting (Figure 3). She became the first female architect who taught in the School of Architecture of A Coruña in 1978. She finally abandoned the architectural practice in 2005 and focused on teaching until her retirement. At this late stage, she allegedly experienced more gender and class bias than in Argentina, such as being questioned in front of her students by other male professors or being undervalued for her work (Carreiro Otero and López González 2016b, p. 124).

Figure 3.

Area of Leisure and Swimming Pools in Cesuras (A Coruña, 1997), by Myriam Goluboff Scheps. Photo credit: mccl arquitectos.

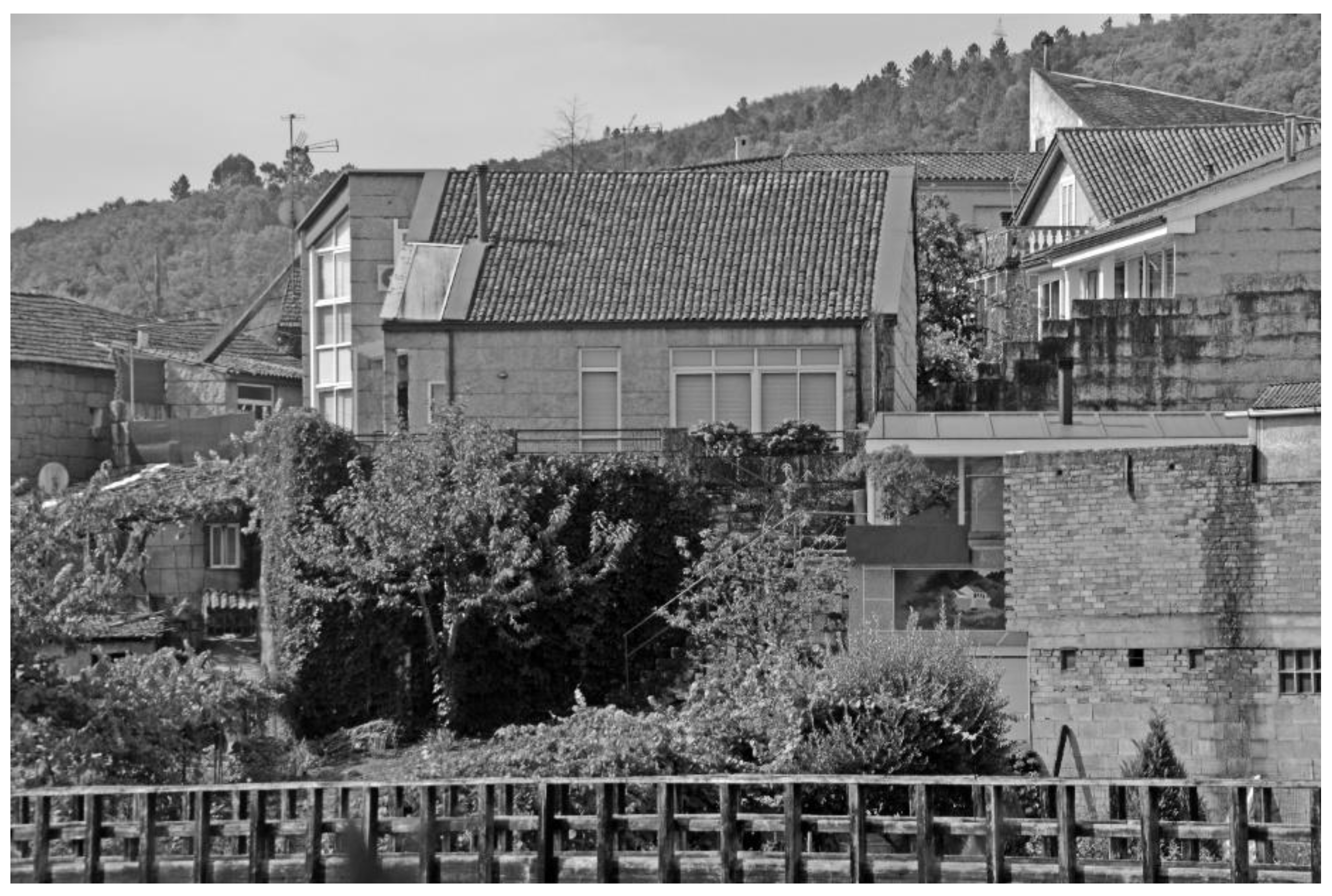

Pascuala Campos de Michelena (1938) was the fourth female architect who graduated in Barcelona, in 1966. Originally from Sabiote (Jaén, Andalucía), she grew up in the post-war period under the principles of the republican Institución Libre de Enseñanza (ILE, the Free Institution of Education), where her mother Carmen de Michelena Morales learned to be a teacher. After registering in 1968, she developed a fruitful career in Pontevedra during the 1970s and 1980s in partnership with her husband at that time, the architect César Portela, and later, independently. By then, she had become a mother of three.20 One of her most published projects is the Galician Institute for Aquaculture Training (Instituto Galego de Formación en Acuicultura, IGaFA) in Niño do Corvo, Arousa Island (1990) (Figure 4), an architectural tribute to the ancient fish-salting and processing factories that covered the Galician coast in the past (Campos de Michelena 1993, 1995b). She is also fond of the residential projects she completed for her female friends: Antolina’s House (1993) and Fina’s House (1995) (Campos de Michelena 1995a), or her own house (1998), all of them in Pontevedra. She became a professor at the University of A Coruña in 1982 (Casares Gallego and Álvarez García 2013), where, in 1995, she was the first female architect holding the chair of Architectural Projects in the history of all the architectural schools in Spain. She remained the only one until 2012, 17 years later.21

Figure 4.

Galician Institute for Aquaculture Training (IGaFA) in Niño do Corvo (Arousa island, Pontevedra, 1990), by Pascuala Campos de Michelena. Photo credit: María Novas.

Pascuala Campos de Michelena is also a declared feminist activist and pioneer who introduced a gender-based perspective to the field. In the late 1970s, she was also part of Feministas Independentes Galegas (FIGA, Independent Galician Feminists), where she participated in the organization and attended different feminist seminars (Comisión de Igualdade do Consello da Cultura Galega n.d.). During the 1990s, she gained the chair with an innovative research work on Espazo e Xénero (Galician language, Space and Gender). She was a pioneer, introducing and teaching subjects such as “Body, Space and Architecture” (Casares Gallego and Álvarez García 2013), and co-organizing and actively participating in different courses and seminars such as the ongoing Ciudad y Mujer (City and Women) in 1993 and 1994, of which proceedings were published in 1995 (Bisquert and Navarro 1995). She retired in 2008, and in 2017 the Gender Equality Commission of the Galician Culture Council organized a seminar honoring her work.

María Jesús Blanco Piñeiro (1939), known as Chus Blanco, graduated in Madrid in 1970 and became the fourth female Galician architect to obtain her license in 1972. More than a decade after Elena Arregui went to an academy to prepare for her entry exam, she received similar comments when, even supported by her father, she decided to do the same: “she must think about it, this is not a career easy for a woman” or “here men get the degree with 31 or 32 years old and, of course, that for a woman....!” (Carreiro Otero and López González 2016b, p. 149). She was the first female architect to establish a professional career in Ourense during the 1970s, working on collaborations with other male colleagues at the beginning, and then independently. The Alén House in Leiro (1981), for example, is one of her representative housing projects, often organized through the stairs. This helps to accommodate the volume in the topographical differences defined by the proximity of a riverbank (Figure 5). She has highlighted her passion for project management, and even she had to experience implicit bias and explicit discrimination; her colleague Pepe was “Don José” (Mr. José), meanwhile, she was “that woman” (Carreiro Otero and López González 2016b, p. 170). Chus Blanco also identified the difficulties of continuing a career that did not have a basic life-sustaining schedule. More specifically, the significant differences in the use of the time between her and her husband, the well-known Galician painter Quessada, Xaime Quesada Porto (1937–2007), especially after having a child, who also became a painter, Xaime Quesada Blanco (1975–2006). Since the economic crisis in Spain started in 2008, she has diminished her professional dedication to a few projects, including more housing projects. She focuses her efforts on directing the Foundation Quesada Blanco, which preserves the legacy of her son Xaime Quesada Blanco, and her husband, Xaime Quesada.

Figure 5.

Alén House in Leiro (Ourense, 1981), by María Jesús Blanco Piñeiro. Photo credit: mccl arquitectos.

Julia Fernández de Caleya Blankemeyer (1940) graduated in Madrid in 1970. In 1971, she gained a grant from the Amo Foundation, at the University of Southern California, to pursue a Post-Master’s degree in urban and regional planning. Once she returned, she registered, and in 1973, she started working in partnership with José Juan González-Cebrián (Pepe Cebrián), her husband with whom she had three children by then.22 She became the second female architect to teach at the School of Architecture in A Coruña in 1980, then in its sixth academic year. There, she taught the course Gardening and Landscape, her focus in the Department of Urban Planning until her retirement in 2010. She sporadically continued to work independently on different projects. Julia Fernández de Caleya Blankemeyer was the first Galician female architect defending a doctoral thesis in the School of Architecture of A Coruña, at the age of 54. She graduated cum laude and was awarded the extraordinary prize of best thesis of the year in Architecture in 1994.

5. Galician Female Architects in the Progressive Democratic Institutionalization (1982–1986) and Pioneer Leading Roles into Politics: Pilar Rojo Noguera and Teresa Táboas Veleiro in the Consolidation Period

Democratic institutionalization consolidated itself during the first socialist government in Spain during the period 1982–1986. It was defined by the inaugural policies that were progressive and marked the effective entry of Spain into the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1986. In parallel, during these years, the university progressively lost its elitist nature and the normalization of the presence of women became more and more habitual. The social ladder began to work. In the academic year of 1982–1983, the number of women studying at university considerably increased, particularly since primary and secondary education (EGB, General Basic Education), became public and unsegregated during the 1970s.23 In the academic year of 1990–1991, female students reached quantitative equality in Spanish universities, however, this was far from the reality in technical schools and the experimental sciences, which were still mostly comprised of men (Carreiro Otero et al. 2014). In architectural studies, even as a substantial minority, reduced figures finally developed during the 1980s and following decades, more than fifty years after women first gained access to the study of architecture.

On another note, this period includes the first generation of female Galician architects studying at the School of Architecture of A Coruña (ETSAC), created in the year 1973 (Table A1).24 The ETSAC, the only existing Galician public school of architecture, officially opened in the academic year of 1975–1976, with just 19 female students (13.9%) and 108 male students (86.1%). This ratio slightly increased during the 1980s, and eventually reached 30% in the 1990s (Fernández-Gago Longueira 2013). The first-generation of students graduated in the academic year of 1981–1982, including the first female architect who graduated in the School of Architecture of A Coruña, María de los Ángeles Brussotto Rodrigálvarez. Ranked number five in her class, she studied first in Barcelona and then at ETSAC during her final two academic years. Her career has been atypical, as she started working in Mallorca, her birthplace, and three years later she moved to Gran Canaria, where she had more professional opportunities. There, she worked for around five years on significant projects, while specializing in property valuations. In 1998 she returned to Mallorca, where she continues to live and work on valuations, a subject that she taught at the University of the Balearic Islands (UIB).

When it came to professional Galician female architects, during the 1980s, the number of women who were licensed remained less than one hundred (Carreiro Otero et al. 2014).25 During this period, difficulties for their professional inclusion remained (Table A2). Even if the strategy of working in mixed-gender teams, combining university teaching (a steady public job) with occasional projects persisted, after the transition to democracy, female architects would pursue, for the first time, a new kind of career, including playing a role in politics. The consolidation period is thus represented by figures such as Pilar Rojo Noguera and Teresa Táboas Veleiro, who portrayed the definitive incorporation of female architects into the public domain par excellence: the political sphere.

Pilar Rojo Noguera (1960) graduated from A Coruña in 1986 and registered in the same year. She practiced architecture for a short time, joining the office of her husband Alfredo Díaz-Grande, also an architect, from 1986 to 1988, when she gained access to the Public Finances body of the State. Then, she became a mother of two.26 In 1996, she began her political career for the conservative party PP as a provincial delegate in the Galician government for Culture and Social Communication in the city of Pontevedra. Since then, she has experienced a continuous ascent in her political career. She was Counsellor of Family, Culture and Sports in the Galician government (2003–2005), President of the Parliament of Galicia (2009–2016) and finally, from 2016 until April 2019, member of the Spanish Congress of Deputies in Madrid, el Congreso.

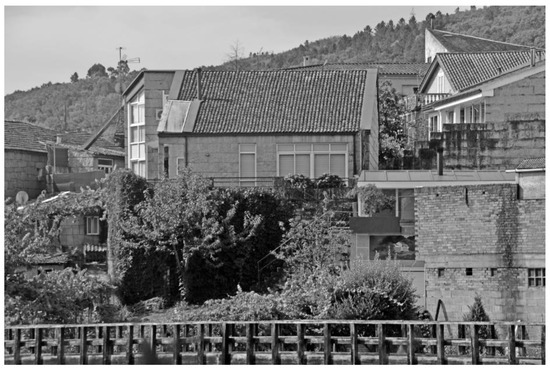

Teresa Táboas Veleiro (1961) graduated in México in the mid-1980s, in the same city where she was born into a Galician family. She is the only architect, of the ones mentioned, who has discussed having a female role model during her studies; the Mexican architect Sara Topelson de Grinberg. She obtained her Ph.D. in 1987 with cum laude, published with the title El color en arquitectura in 1991 (Táboas Veleiro 1991). She registered in 1987 and initially practiced architecture in the studio of César Portela in Pontevedra. She was also a municipal architect in the nearby town of Marín for three years until she founded her firm in 1990. There, she worked independently, developing her interest in social housing projects, such as the one in Pereiro de Aguiar, Pontevedra, in 2006 (Figure 6). She was married to the lawyer Máximo Sánchez, and they had two children.27 Teresa Táboas assumed remarkable positions at the COAG and in 1999, as she became president of the Delegation in Pontevedra until the year 2003. She then became the first female Dean of the Galician Association of Architects between 2003 and 2005, and the second Spanish one since the CSCAE was founded in 1931. During that period, the COAG initiated relevant projects and discussions, such as the debate around ugliness or the Proxecto Terra,28 among others. She left this position when she was appointed and became the first female Councillor of Housing and Land Development in the Galician government for the left-wing Galician nationalist party BNG (2005–2009). There, she worked hard to solidify democratic values over the real-estate bubble, approving, for the first time in 2007, the Normas do Hábitat (Habitat Standards), or initiating the plan of Social Housing which unfortunately remained unfulfilled. Since then, she continues working in the world of business between Pontevedra and Mexico, but also actively participates in seminars and talks. In 2006, she was awarded the Gold Medal at the University of Anáhuac in recognition of her professional career.

Figure 6.

Social Housing in Pereiro de Aguiar (Pontevedra, 2006), by Teresa Táboas Veleiro. Photo credit: mccl arquitectos.

6. The Quantitative and Qualitative Legacy of the Pioneers: Galician Female Architects in Transition (>1986)

We will have to wait until the end of the twentieth century for a definitive change of trend in the horizontal inclusion of women in architectural studies. For the first time, in the academic year 1996–1997, more female than male students gained access to the ETSAC. The number of female graduates was very close to the number of male graduates in 2000–2001. In the academic year 2007–2008, the number of female students was, for the first time, higher than the number of male students, as well as the number of graduates. This also indicates their increasing trend to succeed faster. This trend continues in 2019, and the number of female undergraduates and graduate students continues to be slightly higher.

However, the profession of architecture is still a male-dominated one in Galicia. Despite the normalization at the undergraduate level, we have not overcome the fact that women practicing architecture are still in the minority, and the data shows that this has worsened over the last few years. COAG data shows that achieving gender equality is more difficult in architecture (especially horizontal and vertical inclusion); a much slower process that not entirely depends on the number of college-educated female architects. The number of licensed female architects was only 111 in 1990, while there were 775 men (12.53% vs. 87.47%); in 2000, 325 women and 1.254 men (20.58% vs. 79.42%); in 2010, 936 women and 2.022 men (31.64% vs. 68.36%); in 2012, 926 women and 1.923 men (32.50% vs. 67.50%) (Carreiro Otero et al. 2014) and in 2015, 738 women and 1.911 men (27.85% vs. 72.15%).29 In just three years, the number of female practitioners dropped nearly 5%, reversing a trend that lasted decades and confirming that the effects of the economic crisis have more impact on women’s careers. Today many graduates perform different jobs or emigrate to other Spanish cities or other countries, both European and beyond. As a strategy to overcome the great difficulties they face integrating themselves into the field and staying on, a bigger percentage of female Galician architects work in the public administration such as technical offices, secondary education or universities (Carreiro Otero et al. 2014), reinforcing the horizontal segregation in the profession (Agudo Arroyo and Sánchez de Madariaga 2011). This is one of the reasons why in Spain, as Inés Sánchez de Madariaga has proved (2010), a significant number of women continue leaving architecture.

If we compare current graduates and the number of registered practitioners, women that leave architecture in Galicia represent approximately half of the Galician graduates, reflecting an increased leak in the pipeline. This is the phenomenon of a disproportionate number of women who exit the profession as they progress from graduate studies to a professional career and then beyond. Additionally, in Spain, despite the increment of graduated female architects, the ones that are practitioners work in precarious job conditions (Álvarez Lombardero 2017). The stereotype of the super-productive architect, living for work (Álvarez Lombardero 2016), opposes the use of time of many women, that still do most of the unpaid work necessary to sustain humans’ everyday life. Besides that, it continues to be unusual to find architecture offices directed exclusively by women.

The inequality situation severely increases if we look at academic architectural education. The percentage of female architect professors in the ETSAC in 2019 was just 16.8%,30 23 women compared to 137 men. Qualitative parameters in architectural education continue to be essentially male-dominated, and this problem critically intensifies in hierarchical positions. More than twenty years after Pascuala Campos de Michelena was the first one in the state holding the chair of Architectural Projects, no female architect held any chair in the ETSAC (Carreiro Otero et al. 2014). In 2019, there was not a single catedrática. Of the 23 female architect professors, 16 hold a Ph.D. (69.6%) For the time being, no female architect has ever directed the school since it was founded in 1973.

On a different note, a study published in 2014proved their limited professional recognition in different influential journals,31 and concluded that there is a lack of visibility of female Galician architects, even the pioneer ones.32 This lack of visibility is much sharper on their written work33 (which defines their architectural thinking) more than their architectural work (published using visual materials, such as photographs and plans). This reveals a lack of an independent, female-authored corpus of theoretical texts. Most of the entries analyzed were published in the period 1990–2010 (82%) and their work appears in specialized journals irregularly, or through a low and limited frequency. This weak visibility is influenced by the fact that most of this information has been published in journals edited in peripheral areas of the peninsula. Also, since their work has been widely defined through collaboration (86%), their authorship has been commonly considered as secondary in the male–female partnership (Fernández-Gago Longueira et al. 2014). The testimonial presence of female Galician architects in specialized journals for almost sixty years has become evident in the example of Pascuala Campos de Michelena, the most visible one, who also developed a theoretical approach to architecture based on gender, but for whom a total of 15 registered architectural entries were published.34 This had a consequence in the lack of female role models in the architectural field, in a vicious circle that reinforces gender stereotypes and penalizes, not only their career progression, but also the ramifications of their quality contributions to the field. Once again, male experiences are the ones perpetuated through the architectural system, leaving no room for different perspectives, devaluating, in the process, the invisible history of women in architecture, even if this outcome is far from reality (Chías Navarro 2011).

7. Results and Discussion

Since Rita Fernández Queimadelos landed in Madrid, it would take eighty years to achieve gender equality in architectural studies in Galicia and to normalize a woman’s presence in the profession, even if there is still a long way ahead. In a period of half a century, nine pioneers have been identified. Rita Fernández Queimadelos pictured the precedents in the first generation of female architects during the democratic experience in the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939). Then, Elena Arregui Cruz-López and Milagros Rey Hombre were the exception to the housewifization fueled by the dictatorship (1939–1975) in the initial period. Myriam Goluboff Scheps, Pascuala Campos de Michelena, María Jesús Blanco Piñeiro and Julia Fernández de Caleya Blankemeyer continued to be the exception during the transition to democracy (1975–1982), even if during this continuity period, the first declared feminist concerns emerged. The social ladder started to work during the progressive democratic institutionalization (1982–1986), when the university progressively lost its elitist nature. Then, the presence of women in architectural schools started to increase progressively. Even if the strategies of survival in the professional world, such as working in mixed-gender teams or combining governmental or teaching jobs with occasional projects, persisted. Then, female Galician architects pursued, for the first-time, a new kind of career. Pioneering leading roles into politics are represented by Pilar Rojo Noguera and Teresa Táboas Veleiro in the consolidation period. Even if all the pioneers practiced architecture, Milagros Rey represents a stable practitioner with a long, cumulative and independent career over time. Milagros Rey is also the only one of them who did not have children.

Even if figures of undergraduate students had developed to effective quantitative equality in the last decades, women continue leaving architecture, and the profession is still a male-dominated one in Galicia. Despite all the achievements of pioneering female Galician architects, their recognition is still superficial. There is a much sharper lack of visibility on their written work—that defines their architectural thinking—than on their architectural work—published through photographs and plans. This is the case, for example, for Pascuala Campos de Michelena, whose theoretical corpus was mostly published during the 1990s in specialized feminist publications, but not in architectural media. Therefore, her research on architecture from a gender-based perspective remained on the margins and has not yet been validated by the architectural community, even today. The limits of this research make this topic particularly relevant for future research directions. In addition, none of the identified pioneers has had a female role model, except in the case of Teresa Táboas Veleiro who studied in Mexico. They were the exception to the rule in a masculine world, and despite this fact, they did not establish support networks among themselves. The reason may be found in Pascuala’s word during the 1990s:

The most important feature of the female segment is working as the sum of individualities and not as a collective. Women, isolated one from each other, find themselves alone performing identical duties.(Campos de Michelena 1996)

8. Materials and Methods

This article is the result of a combination of documentation, based on an ad hoc bibliography and the systematic, rigorous and precise analyses of primary sources based on previous work completed by MAGA. Quantitative and qualitative methods in MAGA’s research include the elaboration of the Galician women database (graduation, licensing and categorization of professional practice data) and the identification of the nine female Galician architects’ pioneers and the study of eight of them (the exception is Pascuala Campos de Michelena); likewise the definition of the concept “pioneer”, the conducted interviews, the established periods and the documentation and redrawing of their architectural work. This last information was compiled in different archives including personal archives, the Archive of the Kingdom of Galicia, General Archive of Public Administration, and/or specialized publications. The most important archive of Pascuala Campos de Michelena was partially released online in the Album de mulleres (Women’s Album) by the Comisión de Igualdade do Consello da Cultura Galega (Gender Equality Commission, Galician Cultural Council). Quantitative methods include a statistical analysis from a diverse database. The female architecture students and professors at the University of A Coruña and the University of Santiago de Compostela database, registered female architects at the Galician Association of Architects database, and female architects at the public administration body, or working as teachers at secondary schools for the Galician public education service in Xunta de Galicia database (Carreiro Otero et al. 2013).

9. To Conclude: “I Did What I Could. And That’s Already a Lot”

“Hice lo que pude. Bastante es”, were the words that Elena Arregui used when she was interviewed in (Carreiro Otero and López González 2016b, p. 268). All these female pioneer Galician architects had an unquestionable intellectual capacity, in some cases extraordinary, and they were determined and brave. However, overqualification, strong convictions and the tireless work of women do not seem to be enough for a page to be written in architectural history, in a consistently masculine world. To honor their legacy, we hope that this work will inspire many others; to make the path easier for future generations, to leave behind the sum of individualities and contribute to women’s collective strength. To apply to architectural history and theory, where anonymous was too often female.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, by all the authors. Methodology, investigation and resources, M.C.-O. and C.L.-G.; writing, reviewing and editing, M.N.-F.; supervision M.C.-O and C.L.-G. and project administration, M.C.-O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank all Galician female architects—and/or extensively their families—that gave support by providing documentation and reviewing contents, and to James MacDonald-Nelson from the Urbanism Department’s English editing service at Bouwkunde (TU Delft) for his diligent and attentive assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Female architects who graduated in the School of Architecture in A Coruña (1981–1986).

Table A1.

Female architects who graduated in the School of Architecture in A Coruña (1981–1986).

| Surname, Name | Academic Year | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brussotto Rodrigálvarez, María de los Ángeles | 1981–1982 |

| 2 | Arenal Fernández, María Teresa | 1983–1984 |

| 3 | Malo Pérez, María Luisa | 1983–1984 |

| 4 | Novás Fernández, María de los Ángeles | 1983–1984 |

| 5 | Pérez Naya, Antonia María | 1983–1984 |

| 6 | Cifuentes Rama, María José | 1984–1985 |

| 7 | Fonticoba Graña, Ana María | 1984–1985 |

| 8 | Bermúdez de Castro Muñoz, María del Carmen | 1985–1986 |

| 9 | Casares Gallego, María Amparo | 1985–1986 |

| 10 | Castelo Villanueva, María Jesús | 1985–1986 |

| 11 | Castro Dapena, María de los Ángeles | 1985–1986 |

| 12 | García García, María del Mar | 1985–1986 |

| 13 | Llorente Taboada, María de la Paz | 1985–1986 |

| 14 | Riestra Rodriguez-Losada, Teresa | 1985–1986 |

| 15 | Rojo Noguera, Pilar | 1985–1986 |

Table A2.

Female architects registered in the Galician Association of Architects (1961–1986).

Table A2.

Female architects registered in the Galician Association of Architects (1961–1986).

| License | Surname, Name | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 | Rey Hombre, María del Milagro | 1961 |

| 2 | 44 | Arregui-Cruz Lopez, Elena | 1962 |

| 3 | 79 | Campos de Michelena, Pascuala | 1968 |

| 4 | 106 | Blanco Piñeiro, María Jesús | 1972 |

| 5 | 120 | Fernández de Caleya Blankemeyer, Julia | 1973 |

| 6 | 132 | Fernández Puentes, Ana María | 1973 |

| 7 | 331 | López Franjo, María del Carmen | 1975 |

| 8 | 335 | García Gil-Escolar, Luisa | 1975 |

| 9 | 392 | Campoy Vázquez, Laura | 1976 |

| 10 | 476 | Portos Taboada, María Ilde | 1977 |

| 11 | 534 | Forte Villanueva, Graciela | 1978 |

| 12 | 548 | López Favre, Elia Elisa | 1978 |

| 13 | 681 | Gómez Somoza, Clara | 1980 |

| 14 | 709 | Leboreiro Amaro, María de los Ángeles | 1980 |

| 15 | 757 | Cameselle Sola, María Concepción | 1981 |

| 16 | 821 | Pernas Prieto, María Celia | 1982 |

| 17 | 850 | Insua Cabanas, Mercedes | 1982 |

| 18 | 866 | Maquieira Miguens, María Mercedes | 1983 |

| 19 | 867 | Vila Pérez, Carmen | 1983 |

| 20 | 956 | Peláez Rivero, María Dolores Luz | 1984 |

| 21 | 1000 | Fonticoba Graña, Ana María | 1985 |

| 22 | 1030 | Goldaracena del Valle, Luisa | 1985 |

| 23 | 1056 | Carballo Arceo, Julia | 1986 |

| 24 | 1078 | Casares Gallego, María Amparo | 1986 |

| 25 | 1079 | García García, María del Mar | 1986 |

| 26 | 1082 | García-Magariño Vázquez, María del Pilar | 1986 |

| 27 | 1110 | Castelo Villanueva, María Jesús | 1986 |

| 28 | 1113 | Gonzalez Valeiras, María Josefa | 1986 |

References

- Agudo Arroyo, Yolanda, and Inés Sánchez de Madariaga. 2011. Construyendo un lugar en la profesión: Trayectorias de las arquitectas españolas. Feminismo/s: La arquitectura y el urbanismo con perspectiva de género 17: 151–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Lombardero, Nuria. 2016. De la marginalidad a la redefinición de la práctica arquitectónica. Una nueva generación de arquitectas ibéricas. Sociedad y Utopía. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 47: 297–306. Available online: http://www.sociedadyutopia.es/images/revistas/47/47.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Álvarez Lombardero, Nuria. 2017. La mujer arquitecta como sujeto de una necesaria redefinición de la práctica profesional desde la perspectiva española. Dearq Revista de Arquitectura de la Universidad de Los Andes: Mujeres en Arquitectura 20: 70–76. Available online: https://revistas.uniandes.edu.co/doi/pdf/10.18389/dearq20.2017.08 (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Bisquert, Adriana, and Coord Isabel Navarro. 1995. Actas del curso: Urbanismo y Mujer. Nuevas visiones del espacio público y privado, Málaga 1993–Toledo 1994. Madrid: Seminario Permanente “Ciudad y Mujer”. [Google Scholar]

- Campos de Michelena, Pascuala. 1993. Escuela de Formación Pesquera, Arosa. Fishery Training School, Arosa. In Anuario/Yearbook 1993 Arquitectura Española, Spanish Architecture. Edited by Luis Fernández Galiano. Madrid: AviSa (Arquitectura Viva, S.L.), pp. 130–33. [Google Scholar]

- Campos de Michelena, Pascuala. 1995a. Identidad y Proyecto. Hacer arquitectura es una manera de estar en el mundo. In Actas del curso: Urbanismo y Mujer. Nuevas visiones del espacio público y privado, Málaga 1993-Toledo 1994. Edited by Adriana Bisquert and Isabel Navarro. Madrid: Seminario Permanente “Ciudad y Mujer”, pp. 265–67. [Google Scholar]

- Campos de Michelena, Pascuala. 1995b. Escola de Formación Pesqueira. Niño Do Corvo. Illa de Arousa. In Lugar, Memoria e Proxecto. Galicia 1974–94. Edited by Miguel Ángel Baldellou. Santiago de Compostela: Consello da Cultura Galega, Milan: Electa, pp. 136–37. [Google Scholar]

- Campos de Michelena, Pascuala. 1996. Influencia de las ciudades en la vida de las mujeres. In Mujer y Urbanismo: Una recreación del espacio. Claves para pensar en la ciudad y el urbanismo desde una perspectiva de género. Edited by Charo Rubio Alférez and Miguel Ardid Gumiel. Madrid: Federación Española de Municipios y Provincias y Comisión de la Mujer, pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Carreiro Otero, María, and Cándido López González. 2016a. Un modelo de investigación proyectual: Arquitectas en la cocina. Paper presented at Engendering Habitat III. 5th Engendering International Conference, Madrid, Spain, October 5–6; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2183/17454 (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Carreiro Otero, María, and Cándido López González. 2016b. Arquitectas pioneras de Galicia. Ocho entrevistas. A Coruña: Universidade da Coruña. [Google Scholar]

- Carreiro Otero, María, and Cándido López González. 2019. La cocina moderna en la vivienda colectiva española a través de los concursos de arquitectura del período 1929–1956. ACE: Architecture, City and Environment = Arquitectura, Ciudad y Entorno 13: 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreiro Otero, María, Cándido López González, Eduardo Caridad Yáñez, Paula Fernández-Gago Longueira, Mónica Mesejo Conde, and Inés Pernas Alonso. 2013. El caso de las arquitectas de Galicia. Metodología aplicada al estudio de una profesión. Paper presented at I Congreso de Género, Museos y Arte, Lugo, Spain, October 11–13; Available online: https://ruc.udc.es/dspace/handle/2183/20759 (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Carreiro Otero, María, Cándido López González, Xosé Lois Martínez Suárez, Inés Pernas Alonso, Eduardo Caridad Yañez, Paula Fernández-Gago Longueira, and Mónica Mesejo Conde. 2014. Las mujeres arquitectas de Galicia: Su papel en la profesión y en la enseñanza de la profesión (El ejercicio de la Arquitectura en Galicia desde una perspectiva de género). Madrid: Instituto de la Mujer. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Available online: http://www.inmujer.gob.es/publicacioneselectronicas/documentacion/Documentos/DE1424old.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Casares Gallego, Amparo, and Julia Álvarez García. 2013. Pascuala Campos de Michelena: O camiño á nosa identidade. In As mulleres nas artes e nas ciencias. Vol I: Reflexións e testemuñas. Edited by Rocío Chao Fernández, María Dorinda Mato Vázquez and Roberto Suárez Brandariz. A Coruña: Universidade da Coruña, pp. 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chías Navarro, Pilar. 2011. Estudiantes de arquitectura: ¿un ámbito de igualdad? Feminismo/s: La arquitectura y el urbanismo con perspectiva de género 17: 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión de Igualdade do Consello da Cultura Galega. n.d. Album de mulleres: Pascuala Campos de Michelena. Available online: http://culturagalega.gal/album/detalle.php?id=1090 (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Fernández-Gago Longueira, Paula. 2013. Evolución cuantitativa de la presencia de la mujer en la ETSAC desde el comienzo de la actividad docente. In Jornadas Mujer y Arquitectura. Experiencia Docente, Investigadora y Profesional. Edited by Cándido López González. A Coruña: Grupo de investigación MAGA, ETSA A Coruña, UDC, pp. 65–71. Available online: https://ruc.udc.es/dspace/bitstream/handle/2183/9986/JMA_26_27_nov12_ruc.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Fernández-Gago Longueira, Paula, Inés Pernas Alonso, Eduardo Caridad Yañez, María Carreiro Otero, Cándido López González, and Mónica Mesejo Conde. 2014. Arquitectas de Galicia en las revistas de arquitectura. In Libro de actas: II International Conference Gender and Communication. Edited by Juan Carlos Suárez Villegas, María Rosario Lacalle Zalduendo and José Manuel Pérez Tornero. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla, pp. 969–85. Available online: https://ruc.udc.es/dspace/handle/2183/20761 (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Goluboff Scheps, Myriam. 2009. Huellas: Mario Soto. rd 2 revista del CAPBA distrito 2 63: 157–74. Available online: http://www.mariosoto.net/docs/Mario%20Soto%20por%20Myriam%20Goluboff%20www-mariosoto-net.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Herreros Ara, Aida, Marta Mantecón Pérez, José Ramón Saiz Viadero, and Raquel Serdio Díaz. 2007. Damas ilustres y mujeres dignas. Algunas historias extraordinarias del siglo XX en Cantabria. Santander: Gobierno de Cantabria, Dirección General de la Mujer. [Google Scholar]

- López González, Cándido, Paula Fernández-Gago Longueira, and María Carreiro Otero. 2017. Rita Fernández Queimadelos. Los proyectos de reconstrucción en los Carabancheles, 1943–1945. Arenal: Revista de Historia de Mujeres 24: 169–202. Available online: http://revistaseug.ugr.es/index.php/arenal/article/view/3175 (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Mies, Maria. 1998. Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale. Women in the International Division of Labour, 2nd ed. London and New York: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Muxí Martínez, Zaida. 2013. Primera generación de arquitectas catalanas, ETSAB 1964–1975. In Jornadas Mujer y Arquitectura. Experiencia Docente, Investigadora y Profesional. 26/27 noviembre 2012. Edited by Cándido López González. A Coruña: Grupo de investigación MAGA, ETSA A Coruña, UDC, pp. 31–63. Available online: https://ruc.udc.es/dspace/bitstream/handle/2183/9986/JMA_26_27_nov12_ruc.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Palomares, Manuel. 2017. Las primeras mujeres en el Servicio Meteorológico español. Available online: http://www.divulgameteo.es/fotos/meteoroteca/Primeras-mujeres-SMN.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Pérez Moreno, Lucía C. 2016. The ‘Transition’ as a turning point for female agency in Spanish architecture. In A Gendered Profession: The Question of Representation in Space Making. Edited by James Benedict Brown, Harriet Harriss, Ruth Morrow and James Soane. London: RIBA Publishing, pp. 108–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo Mesas, Pilar. 2001. El Servicio Social de la mujer de Sección Femenina de Falange Su implantación en el medio rural. In Nuevas tendencias historiográficas e historia local en España: Actas el II Congreso de Historia Local de Aragón (Huesca, 7 al 9 de julio de 1999). Edited by Miguel Ángel Ruiz Carnicer and Carmen Frías Corredor. Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza. Available online: http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=968544 (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Río Merino, Mercedes del. 2009. Logros de las mujeres en la Arquitectura y la Ingeniería. Presented at Foro UPM, Madrid. Available online: http://oa.upm.es/1895/ (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Sánchez de Madariaga, Inés. 2009. El papel de las mujeres en la arquitectura y el urbanismo, de Matilde Ucelay a la primera generación universitaria en paridad. In Arquitectas, un reto profesional. Jornadas internacionales de Arquitectura y Urbanismo desde la perspectiva de las arquitectas. Edited by María A. Leboreiro Amaro. Madrid: Ministerio de la Vivienda y UPM, pp. 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, Inés. 2010. Women in architecture: The Spanish case. Urban Research & Practice 3: 203–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, Inés. 2012. Matilde Ucelay Maórtua. Una vida en construcción: Premio Nacional de Arquitectura. Madrid: Ministerio de Fomento. [Google Scholar]

- Táboas Veleiro, Teresa. 1991. El color en arquitectura. A Coruña: Edicións do Castro. [Google Scholar]

- Vílchez Luzón, Javier. 2013. Matilde Ucelay, primera mujer arquitecta en España. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain. Available online: http://hera.ugr.es/tesisugr/21557019.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2019).

| 1 | Despite a Royal Order on the 8th March 1910 establishing that, for the first time, women could effectively access the university on the same terms than men, ten years later we can find just 429 women (2%), and almost all of them in Philosophy and Literature studies (Río Merino 2009). |

| 2 | Matilde Ucelay Maortua (Madrid, 1912–2008); María Cristina Gonzalo Pintor (Santander, 1913–2005) and Rita Fernández Queimadelos (A Cañiza, Pontevedra, 1911–Barcelona, 2008). |

| 3 | Two more women from Madrid were studying architecture during the thirties, but they dropped out of their studies very soon to get marry and exclusively work in the household: Eulalia [Laly] Urcola y Fernández (1910–2010), and Josefina [Chini] Flórez Gallego. Laly Urcola was the daughter of Eulalia Molina and the businessman Carlos Urcola Ibarra. She enrolled in 1929, but she dropped out of her studies to marry the architect Germán Álvarez de Sotomayor y Castro in 1935. Chini Flórez, daughter of the architect Antonio Flórez Urdapilleta, married the Spanish diplomat Luis Villalba (Carreiro Otero and López González 2016a). |

| 4 | Margarita Mendizábal Aracama (Vitoria-Gasteiz, 1931); María Eugenia Pérez Clemente (Coria, Cáceres, 1926–New York, 1978); Elena Arregui Cruz-López (Irún, Guipúzcoa, 1929–Santiago de Compostela, 2018) and Milagros Rey Hombre (Madrid, 1930–A Coruña, 2014). |

| 5 | Before the adaptation of the requirements of the European Higher Education Area (Bologna Plan) during the first decades of the 21st century in Spain, architectural studies were not divided into undergraduate and Master’s studies. To become an architect in Spain, you needed to succeed an academic training of around six years. After being qualified as an architect, it is compulsory to register in the correspondent Association—depending on where your practice is located. No professional experience is required. |

| 6 | MAGA is the acronym of Mulleres Arquitectas de Galicia in the Galician language, which means Female architects from Galicia. The research team, which has been directed by María Carreiro Otero, also includes the professors of architecture at University of A Coruña: Cándido López González, Xosé Lois Martínez Suárez, Inés Pernas Alonso, Eduardo Caridad Yañez, Paula Fernández-Gago Longueira, and Mónica Mesejo Conde. For more information: https://www.udc.es/es/gausmaga/arquitectura_xenero/. |

| 7 | The School of Architecture in A Coruña was created by Decree on 17 August 1973 and was initially attached to the University of Santiago de Compostela. It initiated its activity in the academic years 1975–1976. |

| 8 | Schools of Architecture were created in the nineteenth century in Spain; the first one in Madrid in 1844 and the second one in Barcelona in 1875. In 1958 (the first academic year was 1960–1961), a third one was created in Sevilla. It was not until that same decade that the graduation of the first female architects in Barcelona took place: in 1962, Margarita Brender Rubira validated her title, and in 1964 Mercedes Serra Barenys became the first Catalan student to get a degree (Muxí Martínez 2013). After Sevilla we can find, chronologically, the schools of Navarra (1964), Valencia (1966), Valladolid (1968), Las Palmas (1973), A Coruña (1973), El Vallés (1973) and San Sebastián (1977). In total, these ten accredited schools of architecture—nine public and one private (Navarra)—were the only existing ones until the 1980s in Spain, as the one in Alicante was created in 1984. |

| 9 | Galician and Spanish are gendered languages which distinguish between arquitecto (male architect) and arquitecta (female architect). The voice arquitecta, even if it existed, was not used; the Real Academia Española allows the masculine voice to designate female professionals in the case of the four liberal professions abogado (lawyer), médico (doctor), ingeniero (engineer) and arquitecto. This is an established morphological anomaly, due to the inertia of a conservative view that entrenches those professions as masculine dominated. In the case of the Galician language, arquitecta appears in the dictionary by the Real Academia Galega in 1990, in the first dictionary published after the dictatorship. The preceding Galician dictionary was published in the 1930s and only includes the masculine voice. |

| 10 | In Spain, to officially practice architecture and sign projects, you must become a member of the corresponding Association of Architects (Colegios de Arquitectos). The Associations of Architects in Spain are regional organizations, so which one depends on where you are located. The six original ones were constituted in 1931, including the Association of Architects of León, Asturias and Galicia in the northwest area of Spain. The current Association of Architects of Galicia (COAG, Colexio Oficial de Arquitectos de Galicia, in the Galician language) was officially created after its segregation, in 1973. The CSCAE (Consejo Superior de los Colegios de Arquitectos de España, in the Spanish language) is the organization that brings together and represents the current 26 established associations in Spain. The legally required affiliation involves paying a fee. |

| 11 | The first woman who graduated as Arquitecto in Spain was Matilde Ucelay Maortua (1912–2008) in 1936, the second one María Cristina Gonzalo Pintor (1913–2005), and the third one, Rita Fernández Queimadelos, both in 1940. In the post-war period, Matilde Ucelay Maortua survived different trials by court-martial, allegedly for “assistance to the rebellion” (Sánchez de Madariaga 2012). She was finally socially and politically depurada by the dictatorial regime in the form of not being allowed to receive her academic title until 1946, to sing any architectural project until 1947 and to hold any public charge in perpetuity. Despite these prohibitions, she decisively continued working on projects signed by some of her colleagues, not stopping practicing architecture. In 1951, her signature appeared on a project for the first time and she continuously developed a prolific career with more than 120 projects until her retirement in 1981 (Vílchez Luzón 2013). In 2004, she received the National Architecture Prize from the Spanish Government, the highest recognition for architects in Spain, at the age of 92. María Cristina Gonzalo Pintor graduated in 1940, while combining architecture with physics and mathematics studies (they shared common courses). She also graduated from physics and mathematics. She alternated her career as an architect (surveyor architect at the Cantabrian Association of Architects in 1946 and municipal architect in Los Corrales de Buelna) and meteorologist (Meteorological Observatory at Santander in Cantabria) (Herreros Ara et al. 2007). After a short initial destination in Sevilla, she stayed in Santander for the rest of her life and for some years she became head of the meteorological institution. In 1966, already veteran, she was promoted to Meteorologist and continued working until her retirement in 1978 (Palomares 2017). |

| 12 | Rita gave birth to six children: Vicente (1943, physician-chemicist), Rita (1945, architect), Elena (1947–2004, art historian), Dolores (1948, pharmacist), a fifth daughter who died shortly after birth (1949–1949), and Pilar (1952, dermatologist). |

| 13 | Falange was the name given to the Spanish political party of fascist inspiration founded in 1933 by José Antonio Primo de Rivera (1903–1936), son of the dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera. In the beginning, it was called Falange Española, FE. From 1934, it was named Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista, FET de las JONS. It was the only political party authorized during the Franco regime. La Sección Femenina (SF) was the female branch of FET-JONS. Founded in 1934, it was dissolved in 1977. During those years, it was led by Pilar Primo de Rivera (1907–1991), sister of José Antonio Primo de Rivera. |

| 14 | Real Decreto 1914/78, de 19 de mayo de 1978, by which the Women’s Social Service is suppressed. |

| 15 | Enrique (born 1960), José (1963–2008), María (1967) and Rafael (1971). |

| 16 | Both Elena Arregui and her husband paid their participation fees through a joint account to the mutual insurance for architects la Hermandad, and even their projects were signed in common, as the institution registered them with just the name of Arturo Zas. Even if she was paying her corresponding fee as an architect, under this misogynistic and unfair arrangement, the coverage did officially not include her, and she found out that she could not receive her pension. Many female architects organized together at that time to try to solve the problem: “it is time they consider us persons”, but the Hermandad got angry with “their pretensions”, which were legitimate, and finally had to be heard (Carreiro Otero and López González 2016b, p. 79). |

| 17 | Rita Fernández Queimadelos licensed before (Madrid, 1941), but she developed her whole career in Madrid and Murcia. The first licensed female architect in Galicia is Milagros Rey Hombre in 1961. Then, Elena Arregui Cruz-López in 1962. Until 1968 did not register a third one (Carreiro Otero et al. 2014). |

| 18 | Lalos is the daughter of a renowned architect from A Coruña, Santiago Rey, and Josefa Roca, from Madrid. Josefa’s health issues led them to travel frequently to Madrid. She was born in one of these trips, but the family always lived in A Coruña. |

| 19 | Pablo (born 1974). Myriam Goluboff website: https://chepsy.net/semblanza/ (accessed on 1 November 2019). |

| 20 | Sergio (born 1970), Daniel (1974) and Magdalena (1976). |

| 21 | In 2019, there were just four female architects holding a chair (catedráticas) of Architectural Projects in all the Spanish Schools of Architecture: Blanca Lleó (Madrid), and Elisa Valero (Granada) in 2012; María José Aranguren López (Madrid) in 2017 and Carmen Espegel (Madrid) in 2019. |

| 22 | José (born 1976), Hildegard (1977) and Pablo (1980). |

| 23 | Until that moment, education segregated space and contents by sex and had a mostly private nature. This changed with the adoption of the General Education Law in 1970, that made basic education compulsory for everybody up to the age of 14 (Ley 14/1970, de 4 de agosto, General de Educación y Financiamiento de la Reforma Educativa). |

| 24 | Initially, the School of Architecture of A Coruña—and consequently the first graduates—was ascribed to the University of Santiago de Compostela (USC). Currently, it is ascribed to the University of A Coruña (UDC), officially created in 1989 (Ley 11/1989 del 20 de julio, de Ordenación del Sistema Universitario de Galicia). |

| 25 | COAG data indicates that in 1989 there were 92 licensed female architects out of 789 licensed architects (11.66%). |

| 26 | Fátima (born 1992) and Alfredo (1995). |

| 27 | Teresa (born 1988) and Máximo (1991). |

| 28 | Architectural ugliness, or feísmo in the Galician language, is an architectural phenomenon (highly mediatized) that started to take shape in the architectural public debate in that decade. Proxecto terra is a project for the architectural teaching of students in secondary public education in Galicia, still successful nowadays. |

| 29 | MAGA project collected data segregated by sex until 2012. Then, Carreiro and López keep their own database up-to-date based on the electoral census of the COAG. There, elections are held periodically. Data from 2015 correspond to the electoral census of the deanery elections in that year. |

| 30 | Data compiled in the ETSAC professor’s database. There are a total of 141 professors, and 137 are architects. In total, there are 27 women professors, and 23 are architects. |

| 31 | Architectural journals analyzed from its inception to the year 2012 (in the case they are still active) included: Arquitectos (1976–2011, edited by the Association of Spanish Architects CSCAE); Arquitectura (since 1918), Obradoiro (since 1978), Quaderns d´Arquitectura i Urbanisme (since 1944) respectively established by the Associations of Architects from Madrid, Galicia and Catalonia; Boletín Académico (since 1985, School of Architecture at the University of A Coruña), and the now-extinct Hogar y Arquitectura (1955–1977, Ministry of Housing) and Nueva Forma (1966–1975, El Inmueble) (Fernández-Gago Longueira et al. 2014, pp. 971–72). |

| 32 | From the analyzed 2177 entries, of which 1053 are female-authored, 232 correspond to Galician female architects (approximately 11% of the total). From these 232 contributions, only 33 are female led—author writing on her own—as opposed to the far higher number of contributions involving joint authorship (199). From those 33, 14 had been single authored by a woman previously identified as a pioneer. Collaborative entries represent 86% of the total written by Galician female architects, where the female author is often relegated to a secondary position (Fernández-Gago Longueira et al. 2014, pp. 976–77). |

| 33 | The figures show the prevalence of practice-based professional activity (180 projects with photographs and planimetric drawings, nearly 80% of all entries) over the theoretical discourse (articles, interviews and reviews). Besides this, Galician female architects’ entries are published in geographical proximity, mostly in Galician based publications, reaching the other state-wide ones in just 13% of the cases (Fernández-Gago Longueira et al. 2014, pp. 978–79). |

| 34 | Pascuala Campos de Michelena has published her theoretical corpus, not in architectural journals, but mostly in feminist and specialized publications focused on gender issues during the 1990s. This proves how architectural media did not include those topics, not considered legitimate to be published, excluding specific women’s concerns. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).