Storylessness, after all, has been women’s big problem.

Music… is very real to me, very concrete, though ‘storyless’. But storyless is not abstract. Two dancers on the stage are enough material for a story; for me, they are already a story in themselves.

With these two epigraphs, I want to open up a question about the feminist value of the storyless. In particular, I am curious about whether it can be introduced as a framework within which dancers, in an emphatically multiple sense, might contribute to a feminist revaluation of the storyless. For Balanchine, any number of dancers that is greater than one introduces a sense of a story. In this case, both that sense of multiplicity and its implication of being storied run up against the feminist idea that the “big problem [of] storylessness” is a politicized problem, even a gendered one. But let us first back up and ask: Why does one dancer alone not suffice to imply “material for a story”? What are the conditions by which we distinguish between what one dancer on the stage does, and more than one? And: can dancers ever recapture the storylessness that music brings, even when their bodies might suffice to make “a story in themselves”? If so, is it possible for the potential politics of storylessness to resurface, but positively? Or at least: might we find a way that the gendering and politics of storylessness do not merely consign more bodies to a negative valuation of the storyless?

It is in her 2008 foreword to Carolyn Heilbrun’s famous

Writing a Woman’s Life (1988) that Pollitt makes her contention about the storyless. She is introducing Heilbrun’s book about women poets born in the decade between 1923 and 1933, a book that went on to major readership with a relatively simple argument at its core: “Only in the last third of the twentieth century have women broken through to a realization of the narratives that have been controlling their lives” (

Heilbrun [1988] 2008, p. 60). Narratives here are huge, overarching conventions: the marriage plot is the key narrative Heilbrun has in mind. It is perhaps not surprising that one of the best-known texts articulating the question of “female bodies on stage”, Sally Banes’ (1998)

Dancing Women, also centers the question of the marriage plot, analyzing even Balanchine’s

Agon within the framework of “women’s community and the marriage plot” (p. 209). However, if narratives are conventions scaled to the massiveness of the social, the

stories of Heilbrun’s subjects’ lives are in another category: particular, specific, belonging to each poet she writes about. One of her book’s arguments is that women start writing “their own lives”, creating their own stories, once they break out of these controlling narratives. Thus, the narrative, like “women”, is already a category of the general, whereas the notion of “their own lives” and indeed “their stories” is a particularizing, individual, even

proprietary form.

One could argue, as did Lincoln Kirstein in 1984, that

Agon’s complex articulation of “dancers manipulated as irreplaceable spare parts” suggests quite a different idea than what Banes articulates about the dancers’ roles in

Agon. Must the “stories” initiated by their bodies—assuming Balanchine is right—lead towards the domestic and purportedly permanent entanglement of the marriage plot, as she suggests (

Kirstein 1984, p. 242, cited in

Banes 1998, p. 208)? Let’s sidestep what feels like a somewhat outdated question and focus instead on that slippage introduced by the “role”, the nexus at which I wish to pick up what both Balanchine and Pollitt index, decades apart, as “storylessness”. Let’s ask instead: Can the dancer’s role

itself allow storylessness be more than a gap in conventional narratives or their antitheses in particular, heroic narratives of resistance and difference? Could storylessness, rethought through the problematic of the role, have its own expansiveness, its own qualities, even something that we could contrast with the proprietary relations of “one’s own story”?

Storylessness, as a problem belonging to “women”, demands that we determine how, like stories themselves, it can belong to one person at a time or many: what are its terms? In other words, “women’s storylessness” might be able to work to not capture its subjects within a familiar binary, that between a conventional narrative (“all married women…”) and its antithesis (which becomes, by default, also conventional). Or, for that matter, an impossible universalism and the particularizing form in which every self gets to have her own story. The concept of storylessness might be used instead to undermine the reductiveness of the claim to have one’s own story, and to discuss what that undermining might entail in an art form. Specifically, here I would like to think about the proprietary nature of “stories” in relation to a larger perspective on property relations: one in which we look not at the substance of a story (e.g., the story that itself gets told and maybe retold) as that which gets transposed or transmitted, but at the very act of transmission. Then transmission, exchange, and circulation refer us back to the ways that bodies imply stories, without necessarily filling in what those stories are. When one person—particularly, one woman—then another enters a chain of storylessness, we might see the chain itself as what is produced as a condition of selfhood. That which is subsumed and generated in the exchange is also that which belongs to—or rather creates—the one and her conditions for entering the multiple.

The name for what I am talking about is the role: that component of dance in which a part of a dance gets passed from dancer to dancer. If there are four dancers on a stage, each dances a separate role, even if one role is made up of the same moves as another. The simple fact of their spatial dispersal (or perhaps their temporal organization, so that one dancer moves on one beat, and the other on the next) means that the dance differs across the four dancers. They have each learned their own part, which includes musical and silent cues as well as spatial coordinates. The dance will also look different on each of them, thanks to the particularizing nature of bodies and how they interact with space (the angle at which I see this one, and then that one, then that one…). That is how dance lends particularity to that which could seem formally identical: there is no way to see this body dancing a movement as identical to that body dancing the same movement. This has as much to do with the body, the face, even the “style” or other irrevocably particularizing aspects of a dancer’s performance, as it has to do with the viewer, her position vis-à-vis the dancer, her interest in or identification with that one, there, as opposed to another. (And who is to say that those interests and identifications remain consistent?)

Dance invites not only desire but projection to play across the dancer’s performance—especially when the dancer uses expression, phrasing, etc. to solicit and receive the audience’s gaze.

1 That standing invitation fed Yvonne Rainer’s early, explicit, and paradigmatic effort to “eliminate” characterhood and its vestiges from contemporary dance (

Rainer 1974, pp. 63–69). In the Grand Union’s collaborative, improvisatory ethos, the kind of choreographic structure that allows the passing down of planned movements to others was intentionally avoided (let alone the ways that roles allow dance to organize in the space and time of performance; let alone the taint of story or characterhood that can so easily hitch to roles).

2 However, this exclusion did not really fit Rainer’s trajectory. Describing one of her last works before she stopped choreographing,

Inner Appearances (1972), which was performed to a slide sequence, Rainer writes that she “hoped [that] words, isolated from a social or character-driven context, and coexisting with a task-involved figure, would in and of themselves cause a quickening in those who read them in the dark” (

Rainer 2006, p. 408). That “quickening”—the spectator’s sense of recognition—is key to the way I am describing roles and how they can sometimes rely on the conventionality that we quickly associate to stories. The “character-driven context” of film, faintly suggested by the pseudo-narrative slide sequence of

Inner Appearances, argues against the role’s abstractness, its mere vehicularity as I will be describing it. What I will emphasize is how roles can also perform the abstraction of dance—that vehicularity that enables different dancers, performing different parts of a dance, to show us that dance as a form does not rely on the particularities of this body or that one, the story this one implies or does not. That is how roles can help convey a story but also enable its other; they, like bodies themselves, can index both storylessness and the taint of story.

3Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, the choreographer whose early work

Rosas danst Rosas I discuss here, was deeply affected by a year she spent in New York City in 1981 learning about postmodern dance from choreographers such as Lucinda Childs, Trisha Brown, and Rainer. I am particularly interested in the manner in which De Keersmaeker’s dance, like Rainer’s early films, allows abstracting roles to converge with dance’s particularizing effects. It is this convergence—the taint of personhood contaminating the role as vehicle, as mode of transmission—that makes dance such a potent form of abstract art. Dance does not need to insist on the absence of story, especially after more than a century of explicitly non-narrative dance.

4 Dance always requires bodies, and bodies along with their movements bring into performance an inevitable sense of story that might just be another name for that insoluble aspect through which another’s body appears to the viewer.

5 (One might, in other words, question Balanchine’s notion that it even takes two dancers to introduce a sense of story: as Rainer’s

Three Seascapes (1963) makes parodically self-evident, one dancer’s body is enough to imply story.

6) Even if roles are, on one level, nothing more than the mode of transmission that allows a choreography to be taken up by more than one body (to exist as a score for performances, in the plural), on another, they also signify the way that we understand ourselves as abstractions, as vehicular: not “the character” or its context, but the empty thing we are at various points. In this perspective, dance’s roles are parallel to the social roles that we assume, avoid, and create—those of student, neighbor, etc. It is not that we merely instrumentalize ourselves to become such things. The role is the means by which we project ourselves—our

selves—into a temporality and spatiality that we cannot occupy constantly. It is the move of the self into spaces and times beyond the

this here now; the move of the self into that which always remains, on some level, abstract to oneself. The nature of that move into that which is not

here, particular to me,

now, and its exchangeability (the fact that all of these roles exist because others enter and perform them too) is the way that dance does not merely mimic life, but tunes us to the modes of performance that populate our interior life or what could be called our selfhood.

This framework, including the rhetoric of the “self”, might strike some readers as odd. However, dance provides us with a particular way to understand how we are cleaved, as social subjects, by the ways that productivity has not only monopolized the subject, but also insisted on leaving a remainder. Andrew Hewitt, glossing the German labor theorist Karl Bücher, describes how “vitalistic ‘dance labor’” served as part of an affirmation of the subject divided by laboring/productive movement, and stipulates that “all movements whose purpose lies in the movement itself, however, are not work” (

Bücher 1902 p. 1, translated in

Hewitt 2005, p. 44).

7 On the one hand, what I am proposing here accentuates the ways in which dance in particular emphasizes the labor nature of the dance role: roles consolidate how professional, choreographed dance is

work, by insisting on the transmitted and organized conventions of dance, and by extension, by including the dancer in social, economic, and aesthetic systems of reproduction. On the other hand, the role provides a kind of cover for the manners in which such reproductive conventionality, and the rigors of submitting to, inhabiting, and watching choreography, are themselves part of what selves seek—which is perhaps true of how we both fulfill and fight with the wider and inevitably reproductive realm of social roles. Choreographed dance uses the role to heighten the distinction between the generalized subject (even as it is tethered to and formed by concepts of race, gender, etc.) and the particularized self. The dance role does not stand in for that distinction but turns it into a source of pleasure and thought to be shared among dancers and, through performance, with audiences.

8 1. Rosas danst Rosas (1983)

All the boys and the girls of my age

Walk down the street two by two.

All the boys and the girls of my age

Know what it is to be happy.

Eyes in eyes, hand in hand,

They go by, in love, with no fear of tomorrow.

Yes but I, I go alone, down the street, soul in pain,

Yes but I, I go alone, for no one loves me.

Françoise Hardy, “Tous les garçons et les filles de mon âge” (1964)

9

Françoise Hardy’s 1960s folk ballad, a chestnut of romantic feminine melancholy, would seem to have little to offer De Keersmaeker, whose choreography debuted in the 1980s with works that rigorously explore musical ideas and operations, a focus especially clear in her dances set to the music of Steve Reich.

10 That is, De Keersmaeker can appear to be a stringent European formalist, not someone interested in sap, mass sentimentality, or even in the self that such sentimentality seems to invoke. In other words, far from Hardy’s chestnut. Yet, De Keersmaeker’s earliest dances are also striking for their performances of received notions of femininity: for example, the “Five Women—so lonely”

11 of

Elena’s Aria (1984); the culotte-bearing flirts of her choreography to Bartók’s

Quatuor No. 4 (1986); or the grinningly victorious empress of

Ottone Ottone (1988). In these early works, and especially in one of her earliest choreographies,

Rosas danst Rosas (1983), she invites charges of rehearsing tired tropes of what femininity is or looks like.

12 However, her interest in and use of clichés––or even merely stylized femininity—also provides a semi-concrete field of reference. These frameworks take her dancers from youthful anonymity into a field of cultural associations that remains usefully imprecise but is nonetheless markedly removed from the forms of dancerly abstraction developed in New York City in the 1960s and after that on European stages.

13That is, whereas Rainer’s

Three Satie Spoons (1962) might parody tropes of femininity—its forced smiles, its graceful extensions—

Rosas danst Rosas, with its “pleasantly feministic” lineup, its “something revolutionary”, took both feminism and femininity seriously, in equal and therefore confusing measure.

14 De Keersmaeker’s unique intervention in this early dance concerns her use of multiplicity to treat those clichés of femininity. She develops a kind of choreographic serialism—itself learned and transformed from the music of Reich and others—in which dancers either repeat exactly the same choreography or produce slight variations on a singular model that in turn produces different roles. In other words, her work evokes both the kind of singularity and its complementary plurality that Hardy describes as proofs of her selfhood. “Les yeux dans les yeux, la main dans la main”: two by two go “the others”, marching endlessly by. Except that in De Keersmaeker’s earliest dances such as

Fase and

Rosas danst Rosas, the “two by two” are not heterosexual couples but duets of exclusively female performers. It is this contrast between an emphatically female

them and a repeated

I that De Keersmaeker’s

je, as it were, originates. If Hardy is consumed with the narrative of the couple, De Keersmaeker anchors her notion of the singular in the plurality of the category “women”.

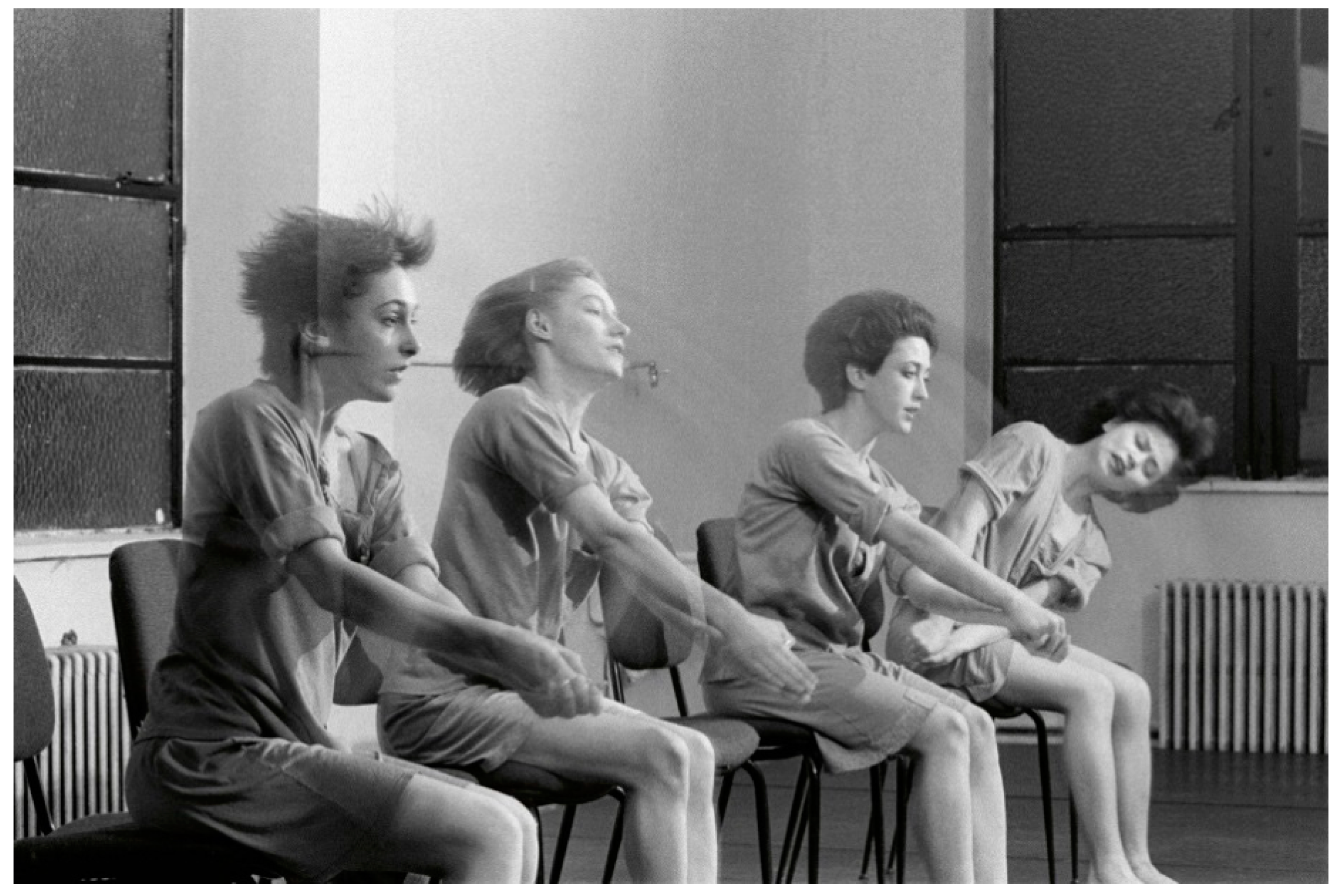

Some of that plurality is described in the staging of

Rosas danst Rosas, not only the array of four dancers, which will preoccupy most of my discussion, but the manner in which they are presented, as individuals and a group. They are dressed identically, in loose, open-buttoned and no-collared shirts over undershirts; loose skirts hitting just above the knee; socks worn with or without tights; and lace-up shoes of the no-name variety worn by nurses and other service workers (or, indeed, fashionable young women playing up what we now call “normcore” aesthetics). Their hair is worn loose, providing a key accessory in the dance: just as some movements will allow long hair to pool languidly or shake dramatically, a short crop allows the audience to see the dancer’s gaze, whose direction is always highly intentional. The work’s first cast—De Keersmaeker choreographed it on herself and the three other dancers who performed it in its first run: Adriana Borriello, Michèle Anne De Mey, and Fumio Ikeda—all wore their hair short (

Figure 1).

15 This violation of balletic convention underscored a notion of femininity both playful and functionalized, digging at the binaristic assumptions that supposedly underlie femininity while pointing—as her earlier work,

Fase, had underscored—at the ways that seductiveness itself can emerge from the appearance of functionalism, labor, and even the identical multiple: that which is indistinguishable in itself.

16Rosas danst Rosas is best understood as an exploration of what it means to put four dancers, all women, on stage continuously for an hour and thirty-five minutes and have them essentially “dance out” questions of repetition, counterpoint, and what it is or means to dance in unison (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). In

Rosas danst Rosas, each dancer depends on others but eventually fills out her role in a manner that subtly signifies “her” alone. That is, extended periods of synchronization and counterpoint (especially in the first two movements) mean that each dancer is formally bound to the three other dancers; in the third movement, each dances a solo that unfolds “her” style or role as different from the others. Then, over the years, new dancers taking on these roles might be assigned to them according to particularities of their bodies or “styles” of movement, thus generating resemblances and differences from the work as it appeared on that now-historical first cast. Thus, the unified foursome evokes not only the dance’s “origin story” as a work choreographed among friends, but a question of how a singular self relates to a multiplicity of selves.

17 That that multiple can be spread over time—over generations to come—is part of how the role functions in dance to explore the condition of multiplicity as it matters to contemporary selfhood.

18 De Keersmaeker adopted the title of this work to name her dance troupe, Rosas, which she founded in concert with making and presenting

Rosas danst Rosas. In that way, she permanently linked her professional identity to not only the initial foursome on whom this particular dance was based, but also to successive generations of professional dancers with whom she has worked since and who now form the basis of an even larger organization comprising a school, summer residencies, and more.

19 The term “Rosas” is surprisingly complex: the singular,

rosa, is a Latin term that names both a plant genus and a spectrum of color. In the work’s title, it is capitalized and thus indelibly evokes the Germano-Polish-Jewish female paragon of early 20th-century anarchist revolution Rosa Luxemburg. (Luxemburg nicely models the transnational nature of De Keersmaeker’s hometown of Brussels as well as that of dance troupes generally.) Yet, it is not

rosa or

Rosa that titles the work or the troupe, but the plural

Rosas. Indeed, that plural form articulates quite clearly the fold I am ascribing to the role: that which cleaves the performing self and that self that is generated onstage, separating

and joining them and in so doing, pointing to their separateness as well as to the principle of separateness and togetherness that the dancers articulate as four dancers performing together, in precise synchronicity, onstage. Finally,

Rosas danst Rosas means “Rosas

dances Rosas”: even if the noun is plural, the verb is conjugated in the third-person singular, identifying the plural noun as a whole, a singular entity. The title phrase builds the plural mode into the substantive

Rosas, but that proliferation happens on either end of the singularized verb “dances.”

Rosas danst Rosas can thus be understood as promising a dance of the proper name and its claims to singularity

and immediately withdrawing that promise.

20 Or, it can show us how the singularity of the proper name depends on an action (dancing) that provides its encounter with itself—but only in the plural. That kind of complex, interdependent relationship of plurality to singularity is the hallmark of what De Keersmaeker allows to unfold among her performers not only in this dance but throughout her choreography.

2. Dancing Together

A performance of

Rosas begins with a “bang”: a forceful, emphatically over-loud musical prolegomena immediately followed by a completely silent first movement. The music, composed by De Keersmaeker’s friend and “music dealer”, Thierry De Mey, sounds half minimalist-serialist, half industrial rock.

21 We first hear it in semi-darkness; in De Keersmaeker’s words, the music “is brutally mechanical, and grows to an almost dangerous high volume. The four dancers come onstage, stand, and fall straight onto their backs, going from verticality to horizontality.”

22 None of the four dancers leaves the stage for the work’s duration, and throughout, they perform in extraordinarily precise, sometimes contrapuntally ordered synchronicity. However, the first movement of their performance, after their collective fall, is conducted exclusively on the floor, lying down. As they begin an extended sequence of repeated movements–they lift their heads while lying on their stomachs; they roll over onto their backs; they draw their hands dramatically to their forehead; they writhe; they rest a moment, pensively, head on fist—the audience is invited to speculate: how do they synchronize so perfectly with one another, in silence (

Figure 4)? If this is, in some sense, the spectacle of

Rosas danst Rosas, it frames not only technical questions, but structural ones: how do four roles that merely reorder and eventually slightly adjust the same movements

make a dance?

The first half of that question is easily answered: it is in part through their audible sighs and exhalations, the sound of one another’s shirts brushing the stage or creasing against each body, that the dancers, moving in this first act without music, synchronize with one another. However, in

Rosas the question of timing and synchronicity is also played against the question of “individuality” that seems to be portrayed through the particular movements that make up the dance. From the first moment, these dancers are showing us something about “the everyday”. Part of this first movement is an intense, fast routine of audible exhalations and a gamut of movements ranging from the banal (a hand run through the hair, sitting up on two forearms) to the dramatic (a fist brought fast into the stomach, as if the dancer were stabbing herself). As they quickly roll, turn over, writhe, and cringe—at one point placing one hand on their foreheads and turning their heads, in the classic gesture of feminine despair—they are performing not only ordinary movements but ordinary gestures. Unlike the “ordinary movements” that composed so much of Judson Dance Theater’s new range of motion in the 1960s, these gestures signal affect and, moreover, even signaling work itself, taken not as parody but as invitation.

23 The dancers perform the quotidian insofar as it can be condensed but also expanded to include affective life, at least insofar as affect can be raised to form or even exacerbated as indices of theatricality itself.

That is not

all that the movements are, however. Indeed, the dance’s forms—the shapes and rhythms that the bodies make, the sequencing of their movements, and most of all their repetition, acceleration and deceleration, and synchronization/permutation across the four bodies—are just as important. Across a multiplication “times four” of dancers doing exactly the same gestures in unison, we see a spectacle of synchronization and repetition and slowness or quickness. We also see the moodiness of a morning, a rousing from sleep, a cringeworthy thing remembered or action regretted (from the night before?). Performed first in rapid, electric bursts and then in decelerated, phrase-less slow motion, these movements are both “formal” and highly, maybe even innately theatrical. They speak not only to the conceit of

Rosas danst Rosas—that it is a dance about a day in the life of a young woman—but also to the idea of showing that conceit spread across four women de-individuated in their synchronicity, even as the dance invests our attention in the notion of the individual, the

one having

a day. Thus, the first movement, in silence, evokes a fitful waking; the second movement, performed sitting on folding chairs to De Mey’s highly percussive music, displays the mechanicity and congeniality of the workday (

Figure 5). The third movement, which unfolds each dancer’s singularity, her individual “style”, is a sequence of four solos that, in De Keersmaeker’s own terms, evokes the languid relaxation of late afternoon (

Figure 6).

24 In the fourth and final movement, we witness the “excess” of night, the kind of energy one might find in a nightclub (

Figure 7).

25 In the end, dance becomes expenditure, and the apparent differences between the dancers’ styles recede again.

This notion of a dance that spans a day is both a quasi-narrative conceit that sets up the dancers as if they were “individuals” and works on a formal level to alter the terms of Rosas danst Rosas’ conceit of permutation and variation (or phase-shifting). The four acts’ movements loosen up and gradually expand across the stage, from the initial position of lying down, to sitting up in stationary chairs, to dancing across the stage. As the successive acts move the dancers towards a state of exhaustion, it also yokes them to the notion of a thing happening across all four dancers. This is different from the framework of dance as permutable and repetitive motion without a human toll. Repetition and permutation are both taking place and also relating to another question, and that “other question” is related to the innately human. “Mes jours comme mes nuits sont en tout points pareils”: My days like my nights are exactly the same. Unlike others who live outside the regime of pure repetition at the base of this core loneliness (others, that is, who are not “me”), I am alone. Repetition draws the “me” into being and Rosas’ dancers into a mode of being together: both at once.

3. Solos

It is the third movement of

Rosas that features solos and forces the question of dancerly “style” into counterpoint with this formalist “me”—the same across three dancers, which we watch in the first two movements.

26 Each dancer had a slightly different style, and the differences in their style were highlighted in the sequenced solos of the third movement, performed against the “basso continuo” dance in unison sustained by the other three dancers. As De Keersmaeker’s astute interlocutor, dramaturg, and in-house musicologist Bojana Cvejić describes:

The structure is based on the division between three dancers performing the same phrase in unison in the background—what we call “basso continuo”—while another dancer continuously steps out as a figure in either a ‘danced’ or a ‘theatrical’ solo. The individuality of the dancers is featured through contrasting qualities that alternate between them; the first was a ‘danced’ solo by Anne Teresa, known for her preference for the ‘attacked’ character; then came Fumiyo’s ‘theatrical’ solo, based on daily gestures in a staccato manner; the third is Adriana’s ‘danced’ solo in a lyrical, legato, and suspended character; and the fourth is a ‘theatrical’ solo by Michèle Anne, which had the lyrical, melodramatic tone of seduction.

The manner in which each dancer performed (when not adhering to De Keersmaeker’s demand for a perfectly synchronized and calibrated energy expenditure) is drawn out in her solo. Ikeda dances with a strong, punctuating sense of “attack”, or what the choreographer calls “

tjak…designating an abrupt, attacked, sometimes nervous, other times violent quality of movement that De Keersmaeker had an affinity for in her own dancing” (

Cvejić 2012). De Mey and Borriello perform more languidly, and De Mey’s solo in particular features a

legato swaying of the hips. Individual style, in other words, becomes motif, and motif becomes the basis of each dancer’s solo. Each performer becomes more uniquely “herself” against that “basso continuo”, or baseline, performed by the group (

Figure 8).

27Each dancer also becomes an embodiment of a different variant of “femininity”, the term that proved a catchword in the work’s initial reception.

28 As Cjević explains, the notion of femininity arises from the “expressivity [that] is inextricable from the construction of movements in the early works, … [that] morphologically and syntactically shapes the movements and their flow” (ibid., p. 14). Femininity is expressive and morphological? Possibly. However, the interesting aspect of

Rosas danst Rosas seems to lie precisely in the way in which that “expressivity” is countered with a structure that itself mitigates the notion of something like a femininity that can be exteriorized or that exists as form. Femininity is not only a shared condition in

Rosas, but one that arises through the structure of repetition and variation, the generic played against—eventually, in the third movement—the specific. Like the “gamut of tones” that Cjević isolates, from the De Keersmaekean attack to De Mey’s sultry melodrama, the question of proprietorship—who owns a kind of femininity—is only possible within a notion that the gamut is shared.

Here, we move away from the question of whether something like femininity is “constructed” or not and into the manner in which dance allows it to become both hyperbolized within the singular dancer as a function of personal style and also circulated across the temporally extended group of dancers who will perform each role over decades (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). Whereas a dancer today might perform De Mey’s

or Ikeda’s role, they are not interchangeable. Each has not only her own position on stage at any given time but her own solo in the third movement; a dancer might be cast into a performance of

Rosas danst Rosas (

Figure 11) according to body type, style of movement, and sometimes even physical resemblance to the original model for each role—or none of the above. Like the concept of

tjak itself, the role couples the performer as a self with the movements onstage.

29Even if we often do not consider dancers as offstage personas, one aspect of the role is how it concretizes our sense of performers as different from one another. This difference does not reduce to any kind of characterological distinction: the four dancers in

Rosas danst Rosas stop short of becoming four different characters, or four portraitists describing how young women generally (or, possibly, dancers specifically) wake up and get through the day.

30 Instead, they are variations on a theme, with a caveat: the theme is themselves and/or the capacious notion of a day in the life of a young woman. The and/or is underscored in

Rosas danst Rosas, just as the ambiguity of the singular/plural in its title

is its title. In this thematic reading, conventionality itself comes to authorize the work: not only the conventions of femininity, but also the conventions enabled by an

of femininity, a belonging together of all four women inside one choreography that is both unifying and subtly differentiating. It is the structure of generality and individuality that is at stake.

Lauren Berlant, discussing the relation of individuals living in the world to conventions or “banal iconic things” that enable individuals to not only live but “love” conventionality, writes:

the convention is not only a mere placeholder for what could be richer in an underdeveloped social imaginary, but it is also sometimes a profound placeholder that provides an affective confirmation of the idea of a shared confirming imaginary in advance of inhabiting a material world in which that feeling can actually be lived. In short, this affair is not an assignation with inauthenticity.

The role is an expression both of conventionality and of shared attachments to it; in Rosas danst Rosas, it could be defined both as femininity and as a framework that is itself “pure”—a framework of transmission and exchange that excludes the idea that conventions exist outside of us. In its insistence on a notion of girlhood or young womanhood as a category for its performers and as a theme, it reaffirms that its storylessness has a gender and moreover that, in that gendering, “this affair is not an assignation with inauthenticity”. It does so even as it insists—digging in as repetition, as theme and variations—on the formalism and rigor of its abstraction. To have modeled solos on the performers “themselves”, allowing an idea of each young woman/dancer to surface, is to have provided the “authenticity” that is itself lodged in convention (the repetition, the basso continuo). The work derives simultaneously from the abstraction of its movements and the multiplicity that arrives thanks to the essentially fugal nature of Reichian “phase-shifting”.

4. Out of Step

The work De Keersmaeker completed just prior to

Rosas danst Rosas was

Fase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich (1982), consisting of a solo and three duets.

Fase adopts Steve Reich’s system of using “phase-shifting”, in which instruments (violin or piano) or clapping hands or a piece of recorded speech play “against” something like the “basso continuo” that De Keersmaeker describes. In a “live phase” composition such as

Piano Phase (1967), two pianists begin by playing an identical rhythmic/melodic pattern in unison; while one performer continues to play unvaryingly, the “second pianist increases his tempo very slightly…until he is finally one sixteenth note ahead of the unchanged figure of the first pianist. The phasing process pauses at this point, as the newly shifted rhythmic configuration is repeated several times” (

Schwartz 1980, p. 386). In the case of Reich’s

Violin Phase (1967), the score for De Keersmaeker’s “solo” in

Fase, a “live violinist plays against one, two, and finally three pre-recorded tapes of himself” (ibid., p. 387).

31 The music and cultural critic K. Robert Schwartz continues:

The same twelve-beat rhythmic/melodic figure is recorded on all three tape channels, but in different phase positions (i.e., the same pattern but with three different downbeats): Track One is four beats behind Track Two, while Track Two is eight beats behind Track Three. Besides the different stationary phase positions of the tape, the performer himself carries out a live phasing process by playing the same figure as that of the tapes, but moving slowly ahead of the various channels.

Most significant in Violin Phase is Reich’s conscious employment of the unexpected resulting patterns. These figures, unforeseen polyrhythmic, melodic, and harmonic combinations that occur as a result of identical material being phased against itself, are constantly in a state of flux.

Phase-shifting is thus a manner of understanding not only rhythm but also its relation to melody. It dislodges the assumption that melody is primarily something carried for example by an instrument or voice (or many instruments or voices playing in unison) and makes it something that can emerge both in auditory experience and from processes of repetition and overlay, a kind of temporal equivalent to the seriality and negative spaces so critical to artistic Minimalism (lending the term “minimalist” to early works by Reich, Philip Glass, John Adams, and others). In Reich’s work, this emergent melody hinged crucially on the role of technology—particularly in works such as It’s Gonna Rain (1965) and Come Out (1966), the latter of which provides the score for the second movement of Fase.

In the second duet of

Fase, in which two performers perform while sitting on chairs, De Keersmaeker underscores an aspect of mechanicity that is indelibly associated to labor. The dancers’ identical costumes—loose, pleated pants and button-down shirts with the sleeves rolled up,as well as their repetitive movements and attentive stares—evoke particular forms of mechanized labor such as switchboard and train operators (

Figure 9). In the 21st century, performances of

Fase can seem to reference almost obsolete forms and ideals of labor, just as Reich’s original use of reel-to-reel tape recorders is today not only difficult to reenact but also itself a marker of the work’s historical moment. However, it is not only the out-of-time quality that

Fase’s image of labor signals: labor provides the very condition of multiplicity that is invoked here and in De Keersmaeker’s next dance,

Rosas danst Rosas.

What we see unfolding across the ninety-five minutes that make up a performance of

Rosas danst Rosas is precisely what is implied in its title: a status for the self dancing, in which the dancer pluralizes (“rosas”) while remaining self-identical (“Rosas”). Self-identical in this instance means a relation to the proper name—that denoted by the capitalized

R. “Pluralizes”, despite its echo with “pluralism”, means merely to

make plural. One body cannot multiply—though it sort of does in

Fase, when two dancers, side by side, are spot-lit so that, at times, their two bodies become four or more figures (according to the shadows on the screen behind them) (

Figure 10). One body does not simply become an image of its own multiplicatory potential, but one self can become—or be seen—as if it were one whose basic form is to be many. Not many

in itself—not an instance of self-destabilizing multiplicity, as we have come to understand the subject, cleaved from within, multiple in itself—but one

of many.

Rosas danst Rosas’ dancers are dislodged from the self-identical in the same manner that a “melody” is dislodged as the product of repetition and overlay in

Violin Phase. They are not merely inside a plurality comprised of different selves, nor are they each only one. They dance a conception of selfhood that is itself loosened from the regular distinctions between individuality, multiplicity, and collectivity; these are selves that refer in their constitution as selves to the status of the multiple.

5. Multiples and Feminism

At times, in

Rosas, multiplicity is complicated by the insertion of something like a dancer’s personal style—this one’s

legato, that one’s

tjak—making the conventional notion of the role increasingly resemble character. However, here, I wish to set the multiple into relation to two crucial turning points in the progression of feminist thought. The first belongs to Luce Irigaray, one of Cvejic’s sources: an apt thinker to plumb as the Belgian feminist is only one generation older than De Keersmaeker, and her

Ce Sexe qui n’en est pas un was published in 1977, less than five years before De Keersmaeker made

Rosas danst Rosas. Irigaray bases her feminism in a conception of femininity that is in turn anchored in the (female) subject as a subject of language: to “play with mimesis is thus, for a woman, to try to recover the place of her exploitation by discourse”, to “make visible, by an effect of playful repetition, what was supposed to remain invisible: the cover-up of a possible operation of the feminine in language” (

Irigaray 1985, p. 76, cited in

Cvejić 2012). Neither language nor discourse are irrelevant to dance, sometimes presupposed (falsely) as a mute art: more obviously, the dancer’s body, like any other, is produced by discourse as much as biology.

32 More to the point here: what situates Irigaray’s conception of femininity within her own feminism is a notion of the “effect of playful repetition” that would enable the deconcealment of how “the feminine” itself—apparently on such full display in

Rosas—operates as signification. In other words, Irigaray’s theory relies on a conception of femininity in order to understand and operate a conception of inhabitation itself as a critical logic. The former is in some ways the progenitor of the latter; “the feminine” is a necessary condition for understanding “the critical” for Irigaray, because the kind of inhabitation that she considers critical is itself a mode of the feminine.

Such repetitions and inhabitations are part of the universally appropriative nature of the role, as in “One must assume the feminine role deliberately”: one “assumes” by repeating, at least in fragments (

Irigaray 1985, p. 76).

33 The role in this way becomes

itself feminist or at least shows us how the Irigarayan model might look as a formal model: the process of assuming and inhabiting is the model of critique itself. In showing the

format of that assumption, how the role is structured by an all-female cast of dancers, however,

Rosas frames the pleasure that the formalism of the role offers. Its rigor, emptiness, and, indeed, its storylessness are part of a proto-feminist deployment of the feminine, just as they are an argument for the pleasures of formalism itself. As Irigaray asserts, mimicry and role playing are not merely critical moves, but deeply linked to pleasure, play, and “nourishment”. As

Rosas shows us, there is intensity and desire inside the work of “assumption”. To assume the rigor of a role is to play to a seduction that can itself be captivating. At the same time, the fever pitch that the dancers reach in the work’s final movement is only one index of the pleasure that begins, for

Rosas’ audiences at least, with the effects of synchronization and differentiation, a vision of sameness and difference fanning out as a hypnotic pattern.

If this feels too close to the feminism of 1977/1983—the period between Ce Sexe’s publication and Rosa’s debut—then the second moment belongs to our present. Let us remember that the role is different from character insofar as it is a mere vehicle, without the need to mimic or indeed perform the “interiority” of a self in the ways that characters demand. Can roles therefore become an ideal form for thinking about this distinction between having a self and basing that sense of selfhood in one’s interiority? Our conceptions of how subjects are formed are based on ideas such as internalization (for example, of subject-producing norms, concepts, or values) or indeed externalization (manifesting the behaviors that concretize our standing as subjects). Roles, instead of playing along with such bifurcations, offer a way to get at our sense of being not only individual and among others, but like others, even progressing from a sense of likeness to a sense of self and the multiplicity of selves. In placing each role in such close proximity to others and allowing each dancer to occupy a role only minutely different from others—but lodging so much pleasure and significance in the scale of that minuteness—De Keersmaeker offers a modality distinctly other to that of the interior and the exterior, the subject and her structures.

Additionally, De Keersmaeker’s play on appearances—especially her staging of the look of late-industrial workers, a look that is barely updated for more recent performances—imbricates the regimes of late capitalism inside her works’ performances of performance. Berlant, in an article on what she calls “lateral agency”, considers the possibility of a “practical sovereignty…[announcing] unconscious and explicit desires not to be an inflated ego deploying and manifesting power”—in other words, a sovereignty that is not about the self-as-one or indeed those traces of narrative drama that conventional ideas about emotionality and agency invite (“we persist in an attachment to a fantasy that in the truly lived life emotions are always heightened and expressed in modes of effective agency…”) (

Berlant 2007, p. 757). Berlant gestures instead at the temporalities and economies “of ongoingness, getting by, and living on, where the structural inequalities are dispersed, the pacing of their experience intermittent” (ibid., p. 759). For Berlant, “the body and a life are not only projects but also sites of episodic intermission from personality, of inhabiting agency differently”; here, I am proposing that the role is similarly not about agency as such, but about the ways in which “the body and a life” might signal the economies of circulation, interdependence, and exchange in which we find ourselves trading roles.

The role is a way to see in the multiple a place for the individual to sense the pleasurable formal work undertaken through repetition and difference. It is also a way to take pleasure in the absence of story, in the pure rigor of that which can be passed down—or better, across—from body to body, from person to person. If, in the social realm, the role can also entail forms of violence (insofar as being an employee or an unemployed person—or for that matter a son or a father—can be violent), the role is one of the key pleasures of dance. Seeing a body dance a role is not only the fulfillment of a balletomane’s desire: it is seeing the shiftiness and ambiguity with which any body onstage takes its place that is itself pleasurable. The body inhabits that which does not belong to it alone. That condition, which I am calling storylessness, is not the same as what Balanchine or Pollitt meant by that term. It is a storylessness that in the best-case scenario reverses the anguish that can result from “erasing singularity from individuality to create the generic.” Bodies are no longer merely “instance[s] of structure” but instances of selfhood that lie precisely in the exchange and circulation of common materials, and in exchangeability and circulation itself. This is not an escape route that will work in every situation, on every body: it is a privilege, but precisely that privilege that storylessness in dance opens up in our time.