Abstract

During excavations of the bimah (the platform for reading the Torah) of the 17th-century Great Synagogue of Vilna (Vilnius, Lithuania), an important memorial inscription was exposed. This paper describes the new finds associated with the baroque-rococo architecture of the bimah and focuses on the inscription and its meaning. The Hebrew inscription, engraved on a large stone slab, is a complex rabbinic text filled with biblical allusions, symbolism, gematria, and abbreviations. The text describes the donation of a Torah reading table in 1796 in honour of R. Ḥayim ben Ḥayim and of Sarah by their sons, R. Eliezer and Shmuel. The inscription notes the aliyah (emigration) of Ḥayim and Sarah to Eretz Israel, the Land of Israel. The interpretation of the inscription shows the use of multiple messianic motifs. Historical analysis identifies the involvement of the Vilna community with the support of the Yishuv (the Jewish community in Ottoman Palestine) and the aliyah of senior scholars and community leaders at the end of the 18th and early 19th centuries. Amongst these figures were Ḥayim ben Ḥayim and Sarah, with Ḥayim ben Ḥayim going on to represent the Vilna community in the Land of Israel as its emissary, distributing charitable donations to the scholarly Ashkenazi community resident in Tiberias, Safed, and later Jerusalem.

Over the past five years (2016–2019), a consortium of researchers1 has been conducting archaeological research on the site of the Great Synagogue and Shulhoyf (synagogue courtyard) of Vilna (present-day Vilnius in Lithuania). The Great Synagogue of Vilna was at the centre of its community and probably the most important edifice of Lithuanian Jewry until its ransacking by the Germans during the liquidation of the Small Ghetto in late October 1941 and later demolition under Soviet control in 1956–1957. On the site of the Great Synagogue, a school was erected of poor modernist design and construction, preserving in its foundation some of the lower sections of the walls of the former building, part of which had been built below street level. During the excavations of 2018–2019, sections of the bimah were uncovered, including an important memorial inscription that had once been set on the foot of the bimah.

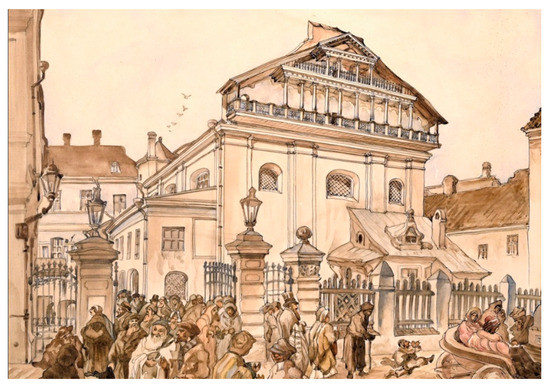

The first wooden Great Synagogue of Vilna was erected, probably in 1573, after the Jews of the city received privilege from Sigismund III Vasa, the united monarch of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Klausner 1935, pp. 5–6). Further privilege was granted in 1633 by Władysław IV to build a masonry synagogue (Figure 1). As the architecture of this new synagogue has been detailed by Levin (2012, pp. 284–93), a background summary is all that is required here. Constructed in Baroque style, the Great Synagogue (Figure 2) was a large, almost square building (22 m × 25 m; 22.5 m high), the floor of which was located nearly two metres, or ten steps, below street level to give the interior a lofty appearance while complying with the height restrictions of the building imposed on the community by the authorities (Klausner 1935, p. 9). Pilasters divided all four façades into three bays each corresponding to the interior arrangement of the building. The central bay of the south-eastern façade, marking the interior placement of the Torah ark, was narrower than the side bays. The prayer hall of the Great Synagogue featured four centrally placed, 8.5-m-high Tuscan columns that reached the spring of the vault, while the perimeter of the prayer hall was spanned by eight additional bays with twelve lunettes above the lower segment-headed windows.

Figure 1.

The Great Synagogue of Vilna in the 19th century—a drawing before the construction of the Strashun Library. Wikimedia Commons.

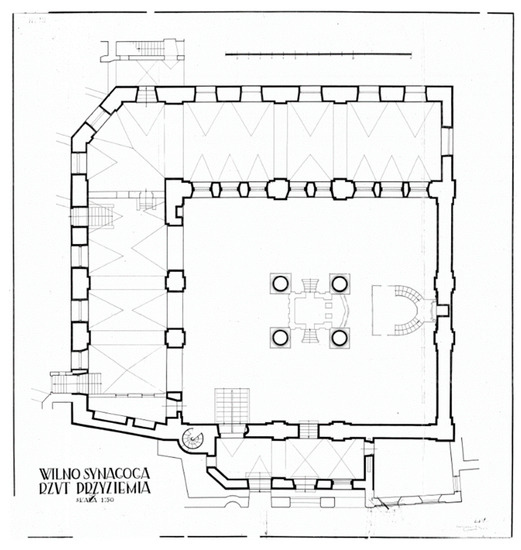

Figure 2.

Plan of the Great Synagogue. Drawing: Roman Sigalin and Jerzy Berliner, 1934. Department of Polish Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology; Used with permission—The Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, ID: 221731.

Prior to the excavation, description of the Great Synagogue in general and of the bimah in particular relied on contemporary descriptions, photographic archives, and a limited number of architectural plans. Of these we should make specific note of plans drawn up in 1893 by the engineer Leonid Viner as part of renovation works of the Great Synagogue (LVIA,2 F.382, Ap.1, B.1513, L. 3v–4r) and the detailed plan of the monument produced in 1934 for the Institute of Polish Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology.3 Both provide modern documentation of the structure, though both are sketchy on detail.

1. The Bimah—Architectural Description and New Finds

The bimah was located between the four large central columns of the main prayer hall (Rupeikienė 2008, pp. 75–76; Levin 2012, p. 286, figs. 5.23–36). Of the original bimah, we have no information, as it was dismantled when a new bimah was donated in the mid-18th century by the benefactor, Yehuda ben Eliezer, known by his acronym as the יסו”ד—Yesod (Yehuda Safra ve’Deyana) (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The three-tiered bimah in Rococo ornamentation, usually attributed to architect Johann Christoph Glaubitz, was 11.6 m in height, almost reaching the synagogue ceiling. The three tiers rose like a wedding cake, each tier lower and narrower than that below, all set on a 0.9-m-high base that measured 3.8 m × 3.2 m. The bottom tier, some 3.9 m high, was entered from the sides by two staircases with decorative wrought iron banisters. This tier was surrounded by a built balustrade mounted by twelve columns, the four red coloured corner columns with Corinthian capitals, each divided by a pair of green coloured columns of the Tuscan order.4 Broken cornices finished this tier, ornamented with rocialles and floral designs and guarded by four crouching lions on the corners, each interspaced with two urns. A curved loge was set on the south-eastern side of this tier, facing the Torah ark. The balustrade around the loge had a widened section at its centre upon which the Torah reading table was set (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The upper tiers of the bimah were purely decorative. The second tier of the bimah, which rose to the height of 3.5 m, was octagonal in plan, with arched openings, crowned with a curved cornice. This was topped by a shorter and narrower 3.3-m-high tier capped by a sloped roof and ball.

Figure 3.

The bimah of the Great Synagogue.

Figure 4.

The Viner plan of the bimah—Leonid Viner. Drawing, 1893. LVIA, F. 382, Ap. 1, B. 1513, L. 2v. Public domain image.

Figure 5.

The front of the bimah with a cloth draped over the Torah reading table. Photo: Courtesy of Ghetto Fighters’ House, no. 31428.

Figure 6.

President Ignacy Mościcki of Poland seated in front of the bimah in 1930. Photo: National Digital Archives of Poland, www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl/jednostka/-/jednostka/5965807/obiekty/367856#opis_obiektu. Public domain image.

Sections of the bimah have been exposed in excavations in 2011, 2018, and 2019, excavations which have added to our physical understanding of the structure and its possible phasing. Firstly, we learned that the floor of the bimah uses terrazzo alla veneziana, a flooring technique with ancient origins, but regenerated in Venice from the 16th century before achieving its greatest popularity in buildings of the late 19th and 20th centuries (Crovato 2002) (Figure 7 and Figure 8). There is every reason to suppose that the terrazzo floor on the bimah is a late addition, probably laid around the turn of the 20th century, most likely as part of the renovation under the guidance of Engineer Leonid Viner, which included the paving of a large section of the main synagogue hall in the same material. The terrazzo floor of the bimah is divided into three panels, greyish-brown aggregates forming the background colour. In the area of the front loge, the floor is comprised of seven radiating lozenges in red and black, the central red lozenge pointing in the direction of the Torah ark. As the area enclosed by the twelve columns is longer on the south-eastern–north-western axis, it is divided into two sections, surrounded by black frames. The front (south-eastern) part consists of red and black rectangles containing eight square-shaped black diamonds. Of the central section, only a small part is known, but it probably contains a central circle, perhaps with a central feature element. In the four corners, in a red-framed triangle, are light green leaves flanked by red tendrils.

Figure 7.

The excavation of the bimah. Photo: Jon Seligman, Israel Antiquities Authority.

Figure 8.

Floor illustration of the bimah—Composite: Shuli Levinboim and Jon Seligman, Israel Antiquities Authority.

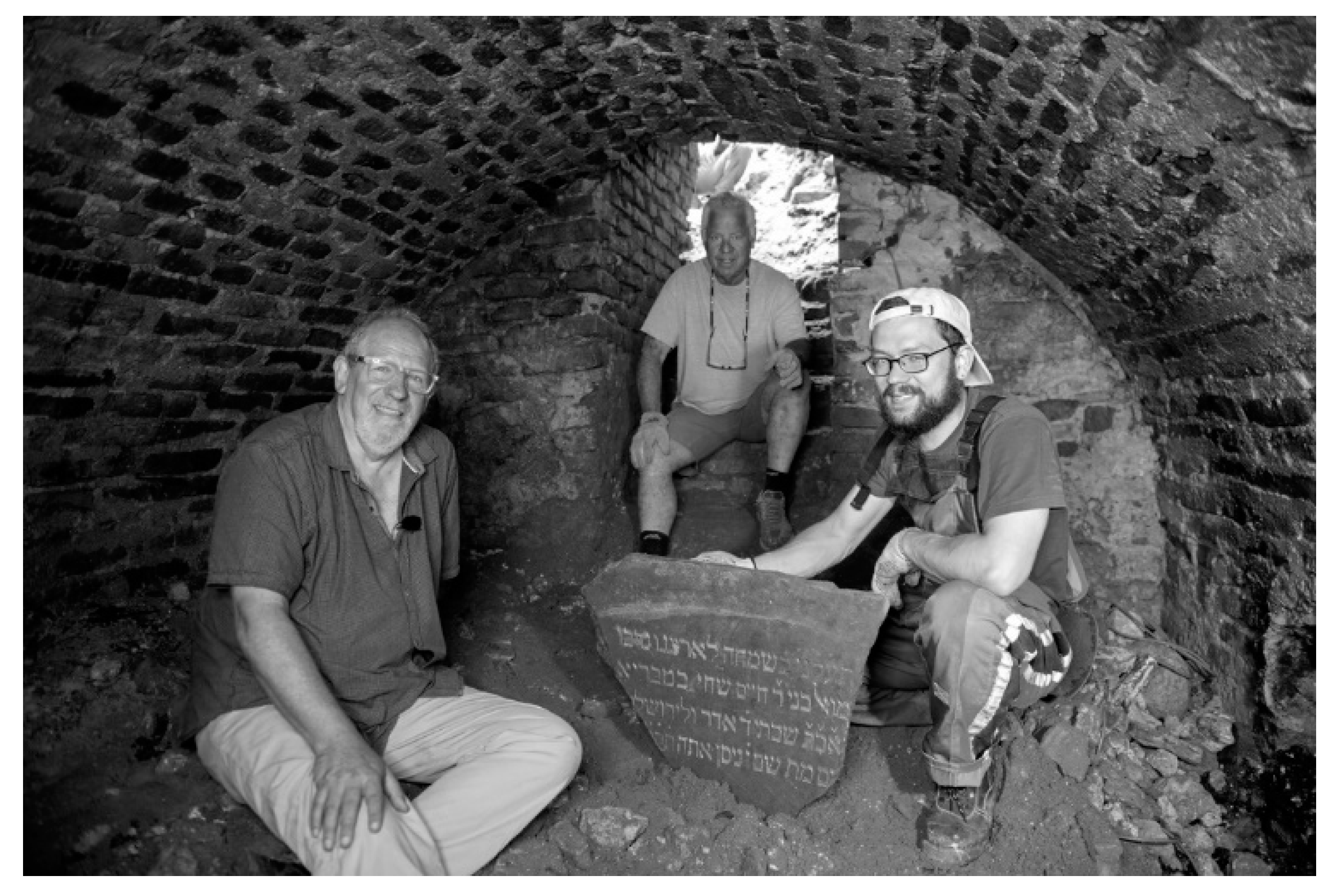

Another surprise provided by the excavation was the exposure of an unknown vaulted cellar built of bricks below the bimah. An arched opening on the front side of the structure led to five steps that dropped into a space occupying the full expanse below the bimah. Two pairs of metal pegs were found on both sides of the entrance. The cellar contained a few hundred coins, most dating from the 17th to 18th centuries, and other finds. There is certainly a possibility that this cellar belongs to the base of the original Baroque bimah of the synagogue and was reutilised during the 18th century for the new structure. Certainly, this cellar is not mentioned in any of the descriptions of the bimah, nor is it visible in any of the photographs. In this context, we should note the legend that recounted the existence of a secret tunnel that led from the Great Synagogue in Vilna to Troki (Trakai), a distance of around 20 km (Broydes 1947, p. 23). Levin (2012, p. 287) proposes that the legendry tunnel was supposedly entered from the genizah (storage for the disposed sacred items) in the polisz, an annexed room on the south-western side of the synagogue, though, in the same manner, the legend could relate to the dark cellar below the bimah.

2. The Inscription

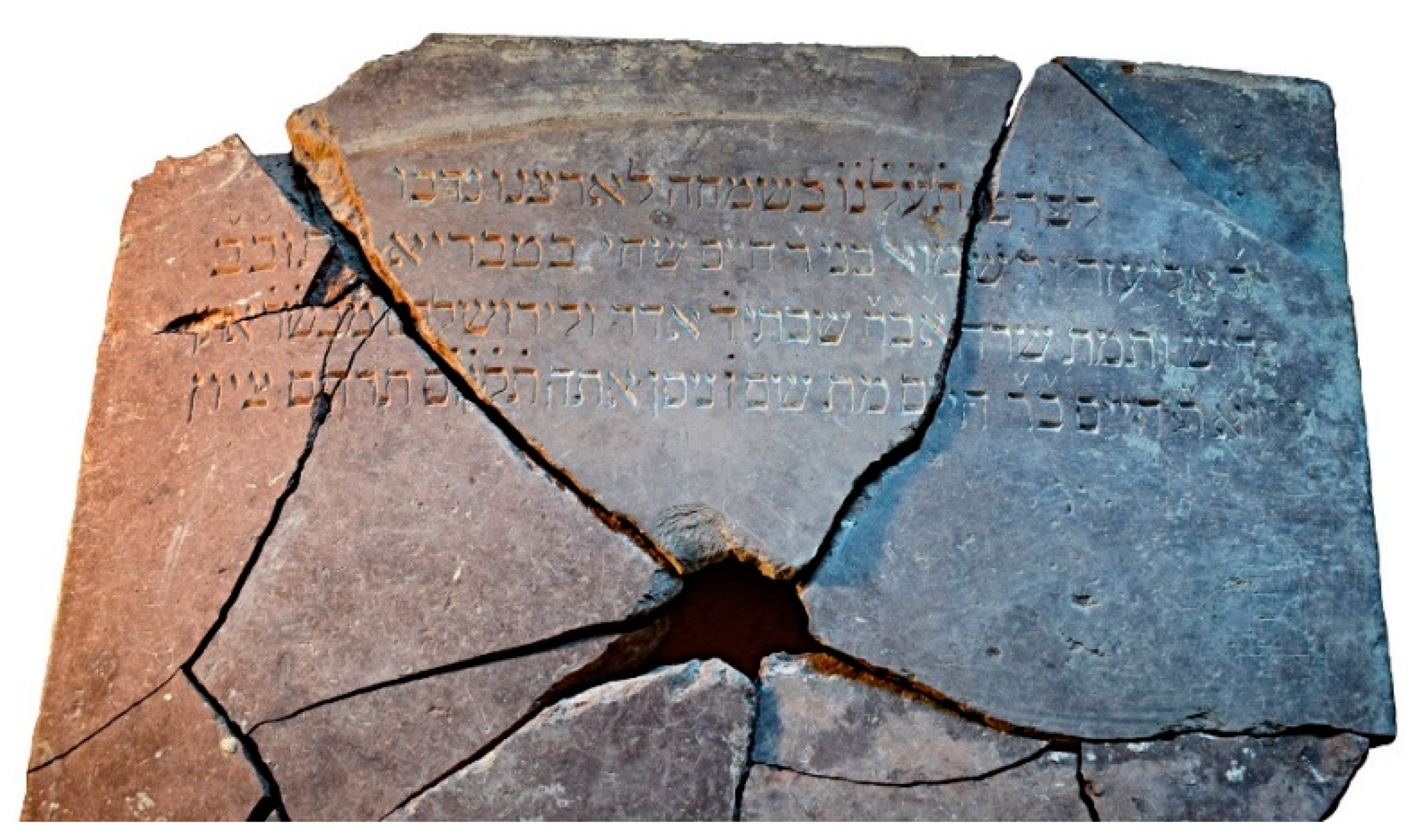

On the floor of the loge of the bimah (Figure 9) and inside the cellar (Figure 10) were twenty pieces of an inscribed red sandstone5 slab measuring 1.4 m × 1.1 m. The slab had been shattered by a single blow at its centre. The rectangular slab (Figure 11) was carefully finished on three edges, the bottom edge left rough in a fashion similar to a maẓevah (tombstone), the unfinished foot usually planted in the ground and not visible. On the upper third of the slab were four lines of deeply incised Hebrew text (Figure 12), some 3.5 cm. high, in a careful Ashkenazi font that developed in printed books in Amsterdam in the 17th century and was later adopted in Lithuania (Yardeni 2002, pp. 116–17). Remains of gilding still existed in the deep incisions of the letters, the gold lettering set over a white chalky base paint. Over the top of the slab were the marks of a bowed arch, probably remains of a frame attached to the stone when it was originally in position. In the only written reference noting the existence of the inscription, Steinschneider (1900, p. 92, n. 1) states that the stone was part of a Torah reading table; however because of its large size, its shape, and the fact that the bottom edge was unfinished, it is our opinion that this stone had once covered the entrance to the cellar, the four metal pegs fixing it in position and the bottom unfinished edge sunk into the floor. Thus, the inscription marks the donation of the Torah reading table, which was set above it on the widened balustrade of the loge at the front of the bimah.6

Figure 9.

Discovery of a section of the inscribed slab on the floor of the bimah loge. Photo: Jon Seligman, Israel Antiquities Authority.

Figure 10.

Discovery of the inscribed slab in the cellar below the bimah. Photo: Löic Salfati, the Vilna Synagogue and Shulhoyf Research Project. Used with permission.

Figure 11.

The inscribed slab after the pieces were assembled. Photo: Jon Seligman, Israel Antiquities Authority.

Figure 12.

Detail of the inscription. Photo: Jon Seligman, Israel Antiquities Authority.

The inscription was complete, incorporating a complex rabbinic text filled with biblical allusions, symbolism, gematria, and abbreviations. It reads as follows:

| לפרט ת̇ע̇ל̇נ̇ו̇ בשמחה לארצנו נדבו | (1) |

| ר̌ (ר”ת רב) אליעזר ור̌ שמואל בני ר̌ חיים שחי בטבריא ת̌ו̌ב̌ב̌ (ר”ת - תבנה ותכונן במהרה בימינו) | (2) |

| ח̇י̇ש̌ (ר”ת -חיי שרה) ותמת שרה א̌ב̌ר̌ 7 (ר”ת—אמינו בת רב) שבתי ד̇ אדר ולירושלים מ̇ב̇ש̇ר̇ אתן | (3) |

| וא̌ר̌ (ר”ת—ואבינו רב) חיים ב̌ר̌ חיים מת שם ז̇ ניסן אתה ת̇ק̇ו̇ם̇ תרחם ציון | (4) |

- (1)

- Bring us up ([5]556, i.e., 1796/97 CE) with joy to our land. Donated by

- (2)

- R. Eliezer and R. Shmuel, sons of R. Ḥayim who lived in Tiberias may it be rebuilt and re-established in our days

- (3)

- for the life of Sarah (=18 years) and Sarah died, our mother, daughter of R. Shabbtai on the 4th of Adar and I gave to Jerusalem a messenger of good tidings ([5]542, i.e., 18 February 1782)

- (4)

- and our father R. Ḥayim son of R. Ḥayim died there on the 7th of Nissan, arise ([5]546, i.e., 20 March 1787) and have compassion on Zion

The diacritics used in this inscription include a dot or caron placed above the letter, the former indicating that the letter should also be interpreted as a number and the latter that the letter is part of an abbreviation.

The text should firstly be understood in its simplicity, detailing the donation in 1796 of the Torah reading table (see below) by R. Eliezer and Shmuel, the sons of R. Ḥayim who made aliyah8 to Tiberias where he lived for 18 years, and for their mother Sarah, the daughter of R. Shabtai, who died on the 4th Adar, 5542 (18 February 1782), and for the passing of their father, R. Ḥayim, the son of R. Ḥayim,9 who died on the 7th Nissan, 5546 (20 March 1787). Beyond that, the symbolism and double meanings used in the inscription require some interpretation.

In the first line of the inscription, the phrase תַּעֲלֵֽנוּ בְשִׂמְחָה לְאַרְצֵֽנוּ (Bring us up with joy to our land) is taken from the מוסף עמידה (Mussaf Amidah prayer) recited on the Sabbath. While this blessing relates mostly to temple sacrifice, it is the return (aliyah) to the Land of Israel that is important for this inscription through the aliyah of R. Ḥayim to Tiberias and its possible messianic association10 as expressed in the Mussaf Amidah. Furthermore, gematric use of the word תעלנו provides the numerical equivalent of the date of the dedication of the inscription for the year תקנ”ו ([5]556, that is 1796).

The theme is picked up also in the second line by the addition of the abbreviated phrase תוב”ב— (תבנה ותכונן במהרה בימינו: may it be rebuilt and re-established in our days) after the name of the city of Tiberias. This religious abbreviation is frequently used when mentioning Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and Tiberias, the four holy cities of the Land of Israel, referring to their future messianic rebuilding.

At the start of the third line, and following on from the previous sentence, appears the abbreviation ח̇י̇ש̌ for the Torah pericope חַיֵּי שָׂרָה (Ḥayei Sarah: Life of Sarah, Genesis 23:1–25:18), which also relates to Sarah, that doubles as the name of the mother of the donors. The diacritics require that the first two letters should have a numerical value of 18, while the caron on the ‘ש’ shows it probably used to be an abbreviation for the word שנים (years), together being 18 years; this is probably the period in which R. Ḥayim lived in Tiberias prior to his death on 1787. This would indicate that Ḥayim arrived in Tiberias in 1769. The sentence continues with the phrase וַתָּמָת שָׂרָה from Genesis 23:2, relating both to the death of the biblical Sarah and the donors’ mother.

Further on in the same line appears yet another messianic reference, וְלִירוּשָׁלִַם, מְבַשֵּׂר אֶתֵּן from Isaiah 41:27, dealing directly with the return to Jerusalem, the word מבשר doubling up in gematria as the date תקמ”ב ([5]542, i.e., 1782) for the death of Sarah. In the final line appears the phrase ‘תָקוּם תְּרַחֵם צִיּוֹן’ from Psalms 102:14, which is recited during Sliḥot prior to the Day of Atonement, but also relates to the return to Zion, the word תקום representing the date for the death of Ḥayim, the father of the donors, in תקנ”ב (5546–1787).

All four male figures are referred to with an honourific title abbreviated as ‘ר (R.). This can refer to the appellation “Reb”, equivalent to the title “Mr.”, used to indicate that the four were affluent community leaders, or alternatively “Rav”, showing all or some to possibly be Rabbis as indicated in a letter written by Shmuel and Eliezer to Berkhi Berakh Segal of Brody that specifically gives refers to Rabbi Ḥayim (see below) (Morgenstern 1998, pp. 246–47).

In the hours that followed the discovery of the inscription, a reference to it was identified in Sefer Ir Vilna (Book of the City of Vilna) published in 1900 by Hillel Noah Maggid, known as Steinschneider. The book, which details the history of the rabbis and scholars of the Jewish community of Vilna, often on the basis of epitaphs from the old Jewish cemetery in Vilna,11 notes that the inscription was cut on a large slab of red “marble”12 donated by the brothers Eliezer and Shmuel for the Torah reading table with the above inscription (Steinschneider 1900, p. 92, n. 1). Armed with this information and that found in Kiryah ne’emana, authored by Shmuel Finn (1860), we can piece together the history of this stone and the figures mentioned in the inscription.

Between the destruction of the small Ghetto in October 1941 and the demolition of the Great Synagogue in 1956–1957, graffities were carved into the inscription slab (Figure 13). Finally the inscription was destroyed by a hammer blow at the centre of the slab that broke it into twenty pieces that remained on the floor of the bimah loge and in the cellar below.13

Figure 13.

The graffities carved into the inscription slab after the destruction of the Great Synagogue. Photo: Jon Seligman, Israel Antiquities Authority.

3. Synagogue Inscriptions

Memorial and dedicatory inscriptions have been a recurrent feature of synagogue architecture, from edifices of the Land of Israel in the Second Temple period and late Antiquity through to modern times.14 As previously emphasised, these inscriptions, both from the Land of Israel and the Diaspora, usually mention the donor’s supplication for memorial for his good deed and sometimes included the sum of money donated, the date of the building, and an appeal for future redemption (Sukenik 1934, p. 69; Rodov 2003, p. 27). As pre-cursors, these examples from earlier periods can be viewed in the context of the Ashkenazi tradition as it developed in medieval and pre-modern Europe. As with the Vilna inscription, the wording of such inscriptions was frequently compiled in the contemporary spirit of piyyut,15 including symbolic allusions, liturgical suggestions, biblical phrases, and gematric riddles (Rodov 2003, p. 27).

Worthy of mention in relation to the Vilna exemplar are the inscriptions from the synagogue at Worms in Germany dated to 1034. One dedicatory inscription,16 for the donor Jacob ben David, refers to ישיני חברון—the sleeping men of Hebron (Epstein 1896, p. 513; Rodov 2003, p. 28, n. 36). Just as with the Vilna inscription, reference is made to the synagogue service, together with a messianic inference to one of the holy cities in the Land of Israel. In this case, the inscription denotes Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, interred in the Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron, and alludes through them to the Sabbath prayer “He who blessed” (מי שברך), blessing the readers of the weekly Torah portion (Sukenik 1934, p. 74; Rodov 2003, p. 26, n. 30, 28, n. 36). For the pious act of building or donating an important part of the liturgical installations or furniture, the patron could express anticipation of messianic redemption and also would be commemorated and granted divine mercy.17

Another interesting example of an inscription relating to religiously motivated aliyah comes from an unusual matzeva from the town of Brody in Galicia, a community connected to the Vilna inscription through the marriage of Shmuel to Ḥayim Segal Landau of Brody (see below). The stone, which is decorated curiously with a ship, was dedicated to Malka bat Yitzhak Babad (Rabinowicz), who passed on 26 November 1834 and was also related to Ḥayim Segal Landau (Morgenstern 1993, pp. 107–8). Beyond the first lines of the epitaph, which again exploits suitable phrases from biblical texts, the last section reads, מלכה ב[ת] המופלג מר יצחק ברב”ד ז”ל מ”כ (מנוחתו כבוד) בארץ הקדושה תובב”א—Malka daughter of Yitzhak Babad who rests in honour in the Holy Land may it be rebuilt and re-established in our days, Amen). The text goes on to describe her aliyah to Bet El (God’s house), which is Jerusalem, together with her father, probably as part the same group of emigrants to the Land of Israel that originated in Vilna and Brody (Morgenstern 1993, pp. 110–11) and her later return to her hometown.

Ample space is given to pictorial representations of Jerusalem and the Land of Israel in the synagogues of eastern Europe, with these portrayals providing a visual connection to their central position in Jewish liturgy and custom and a focus on messianic redemption. The place of such visual motifs had received considerable attention,18 though similar depictions of these themes in written inscriptions have yet to be collected and researched. With respect to Romania, for example, Rodov (2013, pp. 153–9) makes a strong case for the development of portrayals of places in the Land of Israel during the late 19th century in synagogues occurring contemporarily with the expansion of political Zionism and significant immigrations from these same communities. This mirrors, to an extent, the Vilna inscription on cause, intent, and action, though the Romanian immigrants were not transferring a scholarly Torah community from Europe to Jerusalem but intended to establish agricultural settlements in the Land of Israel as part of the Zionist revolution.

4. Ḥayim, Sarah, Eliezer, and Shmuel and the Aliyah of Jews from Vilna to the Land of Israel

Much has been written about the aliyah of Lithuanian Jews to the Land of Israel in general and to Jerusalem in particular at the end of the 18th and early 19th centuries.19 Whether the motivation of this migration is judged to be messianic proto-Zionism (Eliav, Morgenstern, Rivlin) or traditional religious migration to the Land of Israel to create an elite scholarly Torah community in the Holy Land that should not be connected to the development of modern Zionism (Bartal, Barnai, Etkes), the aliyah of followers and pupils of the Gaon of Vilna was a significant early migration that would lead to the founding of Ashkenazi communities in Tiberias, Safed, and Jerusalem in the early to mid-19th century that still survive today. Whatever the motivation was for these migrations, it should be noted that messianic ideology can be identified in the inscription itself, which quotes three liturgical and biblical quotes relating to messianic redemption:

- from the Mussaf Amidah:יְהִי רָצון מִלְּפָנֶיךָ ה’ אֱלהֵינוּ וֵאלהֵי אֲבותֵינוּ. שֶׁתַּעֲלֵנוּ בְשמְחָה לְאַרְצֵנוּ. וְתִטָּעֵנוּ בִּגְבוּלֵנוּ וְשָׁם נַעֲשה לְפָנֶיךָ אֶת קָרְבְּנות חובותֵינוּ’ (May it be Your will, Lord our God and God of our ancestors, to lead us up in joy to our land and to plant us within our borders. There we will prepare for You our obligatory offerings);

- from Isaiah 41:27:רִאשׁוֹן לְצִיּוֹן, הִנֵּה הִנָּם; וְלִירוּשָׁלִַם, מְבַשֵּׂר אֶתֵּן (A harbinger unto Zion will I give: ‘Behold, behold them’, and to Jerusalem a messenger of good tidings);

- from Psalms 102:14:אַתָּה תָקוּם תְּרַחֵם צִיּוֹן כִּי עֵת לְחֶנְנָהּ כִּי בָא מוֹעֵד (Thou wilt arise, and have compassion upon Zion; for it is time to be gracious unto her, for the appointed time is come).

After the collapse of the Ashkenazi community in Jerusalem led by Rabbi Yehuda Ḥassid in the first decades of the 18th century, Ashkenazi Jews attempted unsuccessfully to return to the city. The Jews of Lithuania became deeply committed to the cause of the Yishuv in the Land of Israel, either through aliyah themselves or through financial provision to those resident in the Yishuv. Consequently, leading Rabbis and community leaders in Lithuania held discussions in Vilna in 1770 concerning the imperative to support the Ashkenazi community in the Land of Israel and even sent olim (aliyah immigrants) to strength the Yishuv (Frumkin 1929, III, p. 72; Morgenstern 1998, pp. 163–68). Foremost amongst this movement was Azriel of Shklov, one of the leaders of a small group of leading families migrating to the Land of Israel around 1772, among them Ḥayim ben Ḥayim Shebtels,20 a wealthy community benefactor and leader of the Vilna kahal, who, as a harbinger, seems to have arrived in the Land of Israel in 1769 a little earlier than the others 21 (Finn 1860, p. 180; Frumkin 1929 III, p. 72; Morgenstern 1998, pp. 168–73). Because of difficulties that prevented settlement in Jerusalem due to heavy outstanding debts owed by the Ashkenazi community to Arab creditors, this pioneering community chose the holy cities of Safed, where they established a Bet Midrash in the name of the Gaon of Vilna (Eliach 2019), and Tiberias as their first home.

Once settled in Tiberias, Ḥayim represented the “Nobles of Vilna” organisation (רוזני וילנה) (Morgenstern 2007, pp. 51–70, 204–22) of community leaders that provided financial support to the Yishuv in the Land of Israel, headed by his sons, Shmuel and Eliezer, who had remained in Vilna (Morgenstern 2007, pp. 55–57; Morgenstern 2012, p. 278, n. 109; Barnai 1980 p. 81; Frumkin 1929, III, pp. 72, 138). Furthermore, we learn that Ḥayim Shebtels would become the Vilna community representative for the distribution of donations from Vilna to the Yishuv, through the Land of Israel treasurers (נשיאי ארץ ישראל), also none other than his own sons. This is emphasised in a letter of reply written by Shmuel and Eliezer, in their official capacity, to Berkhi Berakh Segal of Brody, who had requested that funds for olim from Lithuania now resident in Tiberias and Ḥassidic olim in Safed be channelled through another emissary, noting, “it is evident and well known that our community sends money to the Holy Land each and every year; it reaches its destination at no expense whatsoever, to the hands of the preeminent rabbi, the famous noble, our mentor Ḥayim Shepshiller (Shepshils) of our community” (Morgenstern 1998, pp. 246–47).

As Morgenstern (2012, p. 278, n. 109) notes, after Maggid Steinschneider and Finn, Ḥayim had adopted his surname to emphasise the important connection to his father-in-law, Shabtai ben Elḥanan Ḥefez, who is also specifically referenced in our inscription through his daughter, Sarah. Shabtai was a descendent of Rabbi Moshe Rivkesh, author of Be’er ha-golah, and also a descendent of Rabbi Eliyahu, the Gaon of Vilna. The importance of both Shabtai and Ḥayim as community leaders is enhanced by the title “Maggid” apportioned them by Frumkin (1929, III, p. 72) and emphasised by the fact that Shabtai is one of the signees on the appointment letter of the Chief Rabbi of Vilna, Rabbi Shmuel bar Avigdor, in 1750 (Morgenstern 1998, p. 171). In addition, Ḥayim was also related to Ḥayim Segal Landau, the head of the important Brody kloyz and the Land of Israel treasurer for his own community, through the marriage of his son Shmuel to Rechil, Landau’s daughter (Steinschneider 1900, p. 77, n. 1; Morgenstern 1998 p. 47, n. 110). The importance of this alliance was such that Shmuel used his own father-in-law’s name of Landau in signing the letter noted above. As Morgenstern has noted (Morgenstern 2012, pp. 278–79, n. 109), “there was a strong relationship between Brody and Vilna and between these communities and The Land of Israel. The connection was based on kinship, marital alliances and intensive involvements in The Land of Israel affairs”. The bond was cemented by the multi-layered connection of familial ties to the illustrious Gaon of Vilna himself.

The result of this exchange of letters would be the movement of donations of a number of communities through Shmuel and Eliezer to their father Ḥayim, the representative of Vilna in the Land of Israel, with the responsibility to divide the monies to Ashkenazi communities of both Ḥassidic and Mitnaged (Perushim) olim (Morgenstern 2012, pp. 279–81).

From the inscription, together with supporting documentation, we also learn that Ḥayim was joined in Tiberias by his wife, Sarah; his father-in-law, R. Shabtai ben Elḥanan Ḥefez; and his brother-in-law, Elḥanan ben Shabtai Ḥefez. Both Shabtai and his son Elḥanan were vitriolic opponents of Hassidism (Morgenstern 1998, pp. 172–73), such that, later, Elḥanan would join the Sephardic, rather than the Ashkenazi Hassidic community in Tiberias, with his signature appearing on documents of the former from the year 1784 (Morgenstern 1998, pp. 170–71, n. 97).

This small migration of Jews from Vilna and Lithuania failed to fully establish itself in the Land of Israel. The major success in this series of aliyot would be led in 1808 by Azriel of Shklov’s grandson, Rabbi Israel of Shklov, who would lead the significant migration of disciples of the Gaon of Vilna who would successfully re-establish the Ashkenazi community in Jerusalem and eventually rebuild the Ḥurva synagogue as the Great Synagogue of Jerusalem for the Ashkenazi community in the second half of the 19th century (Morgenstern 1998, 2007).

The importance of Shmuel continued well after the death of his father in the Land of Israel, with Shmuel becoming a leader of the kahal (Jewish community) of Vilna in the years 1802–1805 (Morgenstern 1998, p. 247, n. 10), while Eliezer is noted as an opponent of the Chief Rabbi Shmuel ben Avigdor (Klausner 1935, p. 56, n. 4). Indeed, the tombstones of Eliezer, Shmuel, and Shabtai’s son Eliyahu were present in the Old Cemetery of Vilna (Šnipiškės/Shnipishok) until its destruction. These are marked in relatively close proximity to the tomb of the Gaon of Vilna as numbers 63 (Shmuel), 116 (Eliezer), and 68 (Eliyahu) on Klausner’s map of the cemetery (1935).

Eliezer died on 19 March 1805 (י”ח אדר ב’, תרס”ה). On Eliezer’s epitaph, his public work as a community benefactor and leader is noted, ‘עשה תשועה גדולה בישראל’ (begot great salvation in Israel) as is his connection to the life and death of his father in the Land of Israel’דמשק אליעזר, בן איש חיים, אשר הלך לפני ה’ בארצות החיים, בארעא קדישא דישראל’ (Eliezer Damascus, son of Ḥayim, who went before God to the lands of the living, to the Holy Land of Israel) (Finn 1860, p. 219; Klausner 1941, p. 57). The marker of Shmuel, who passed in 1817/8 (תקע”ח) notes his name as Shmuel ben Ḥayim Shepshil Landau, indicating his connection both to his own family and that of his wife (Finn 1860, p. 228; Klausner 1935, p. 63), both families connected to the Gaon of Vilna.22 Nearby was the tombstone of his son, Avraham Ya’acov-Jankel, also an important religious scholar, who died in September 1827 (תקפ”ח) (Finn 1860, pp. 254–55).

5. Postscript

If we are able to trace Shmuel and Eliezer back to the cemetery in Vilna, what of Ḥayim and Sarah. A search of the cemetery in Tiberias was unsuccessful (Morgenstern 1998, p. 171, n. 96); however, two tombstones in the Sephardi cemetery on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem may well be those of Ḥayim and Sarah.23 The graves (Figure 14), located side by side, have no dates and limited supporting data beyond being in an area of the cemetery dated in use to the correct period and marked with the communal designation אשכנזי (Ashkenazi). As there was no Ashkenazi cemetery in Jerusalem at the end of the 18th century, a non-Sephardi Jew would have been buried in their cemetery, but his community affiliation would have been added to the marker.24

Figure 14.

The possible matzevoth of Ḥayim and Sarah in the Sephardi cemetery on the Mount of Olives. Photo: Jon Seligman, Israel Antiquities Authority.

The epitaph on the grave for Ḥayim25 is the following:

| מ”ק (מקום קבורה /מצבת קבורה) |

| הח’ (החכם) המעולה כה’ר (כבוד הרב) חיים |

| אשכנזי |

| The place of burial |

| The sage, the honourable Rabbi Ḥayim |

| Ashkenazi |

The epitaph on the grave for Sarah26 is the following:

| מ”ק (מקום קבורה / מצבת קבורה) |

| האשה הכבודה מרת |

| שרה נ’ב (נוות ביתו) כהר (כבוד הרב) חיי |

| אשכנזי |

| The place of burial |

| The honourable wife, Mrs. |

| Sarah, the household oasis for the honourable Rabbi Ḥayim |

| Ashkenazi |

While these matzevoth are not conclusively identifiable as the markers for the Ḥayim and Sarah in the Vilna inscription, their period and simple epitaphs with communal attribution make them worthy candidates. Their discovery in Jerusalem, marking their aliyah to the Land of Israel, was a fitting end in Jerusalem to the journey sparked by the discovery of the inscription in Vilna, Yerushalayim deLita (Jerusalem of Lithuania).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I thank the following scholars who aided in the interpretation of the inscription: Vladimir Levin of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Aryeh Morgenstern; Prof. Ilia Rodov of Bar Ilan University and Rabbi Yehiel Poupko. The excavation was sponsored by the Good Will Foundation, the Lithuanian Jewish (Litvak) Community and a number of private donors.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barnai, Ya’acov. 1980. Hasidic Letters from the Land of -Israel: From the Second Part of the Eighteenth Century and the First Part of the Nineteenth Century. Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben Zvi. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Barnai, Ya’akov. 1995. Historiography and Nationalism: Trends in the Research of Palestine and its Jewish Yishuv (634-1881). Jerusalem: Magnes Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bartal, Israel. 1994. Exile in the Homeland. Jerusalem: Hassifria Haẓiyonit. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bartal, Israel. 2011. ‘Torah as their Craft’ or ‘Zionist Pioneers’: Two Schools of Thought in the Research on the Immigration of the Vilna Gaon’s Disciples to The Land of -Israel. In The Vilna Gaon’s Disciples in The Land of -Israel: History, Thought, Reality. Edited by Israel Rozenson and Yosek Rivlin. Jerusalem: Efrata College, pp. 7–22. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, Eleonora. 1997. Motifs Pertaining to Jerusalem in the Building and Decorating of 19th and Early 20th Century Synagogues in the Polish Lands. In Jerozolima w kulturze Europejskiej. Edited by Piotr Paszkewicz and Tadeusz Zadrożny. Warsaw: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk, pp. 449–57. [Google Scholar]

- Böcher, Otto. 1961. Die Alte Synagoge zu Worms. In Die Alte Synagogue zu Worms. Edited by Ernst Róth. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag, pp. 11–154. [Google Scholar]

- Broydes, Yitsḥak. 1947. Legends of Jerusalem of Lithuania. Tel Aviv: N. Taverski. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Crovato, Antonio. 2002. I pavimenti alla veneziana. Treviso: Edizioni Grafi, Resana. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, Zussia. 1997. Motifs of Jerusalem in the Mural Painting of Eastern European Synagogues: The Researcher’s Impression. In Jerozolima w kulturze Europejskiej. Edited by Piotr Paszkewicz and Tadeusz Zadrożny. Warsaw: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk, pp. 459–65. [Google Scholar]

- Eliav, Mordechai. 1978. The Land of Israel and its Jewish Community in the Nineteenth Century, 1777–1917. Jerusalem: Keter. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Eliav, Mordechai. 1982. Relations between Ashkenazim and Sephardim in the Land of -Israel in the 19th Century. Pe’amim: Studies in Oriental Jewry 11: 118–34. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Eliach, Eli. 2019. Midrash Perushim—The Kloyz of the Gaon of Vilna, Safed. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/39693028/%D7%9E%D7%93%D7%A8%D7%A9_%D7%A4%D7%A8%D7%95%D7%A9%D7%99%D7%9D_-_%D7%A7%D7%9C%D7%95%D7%99%D7%96_%D7%94%D7%92%D7%A8%D7%90_%D7%91%D7%A6%D7%A4%D7%AA (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Epstein, Abraham. 1896. Jüdische Alterthümer in Worms und Speier. Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums 11: 509–15. [Google Scholar]

- Etkes, Immanuel. 2015. The Vilna Gaon and His Disciples as Precursors of Zionism: The Vicissitudes of a Myth. In The Individual in History: Essays in Honor of Jehuda Reinharz. Edited by ChaeRan Y. Freeze, Sylvia Fuks Fried and Eugene R. Sheppard. Waltham: Brandeis University Press, pp. 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Etkes, Immanuel. 2019. The Messianic Zionism of the Vilna Gaon: The Invention of a Tradition. Jerusalem: Carmel. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Finn, Shmuel Yosef. 1860. Kiriya Ne’emana: History of the Jewish Community in Vilna and Markers for the Souls of its Scholars, Gaonim, Writers and Benefactors. Vilna: Romm Publishers. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Foerster, Gideon. 1981. Synagogue Inscriptions and their Relation to Liturgical Versions. Cathedra 19: 11–46. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Frey, Jean-Baptiste. 1936. Corpus inscriptionum Iudaicarum: recueil des inscriptions juives qui vont du IIIe siecle avant Jésus-Christ au VIIe siecle de notre ére. Rome: Europe Pontificio Instituto di Archeologia Cristiana, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin, Arie Leib. 1929. History of the Sages of Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Solomon Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg-Mulkiewicz, Olga. 1997. The Image of Jerusalem in the Jewish Diaspora of the 19th and 20th Centuries. In Jerozolima w kulturze Europejskiej. Edited by Piotr Paszkewicz and Tadeusz Zadrożny. Warsaw: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk, pp. 467–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hachlili, Rachel. 1998. Ancient Jewish Art and Archaeology in the Diaspora. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Klausner, Israel. 1935. The History of the Old Cemetery in Vilna. Vilna: Vilna Jewish Community. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Klausner, Israel. 1941. Vilna in the Time of the Gaon: Spiritual and Social Conflict in the Vilna Community in the Period of the Gra. Jerusalem: Reuven Mass. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Samuel. 1920. Jüdisch-palästinisches Corpus Inscriptionum (Ossuar-, Grab- und Synagogeninschriften). Vienna: R. Loewit. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, Vladimir. 2012. Appendix: Synagogues, Batei Midrash and Kloyzn in Vilnius. In Synagogues in Lithuania II. Edited by Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, Sergey Kravtsov, Vladimir Levin, Giedrė Mickūnaitė and Jurgita Šiaučiūnaitė-Verbickienė. Vilnius: Vilnius Academy of Arts Press, pp. 281–340. [Google Scholar]

- Lipshitz, Baruch. 1967. Donateurs et fondateurs dans les synagogues juives. Paris: Cahiers de la Revue Biblique 7. [Google Scholar]

- Lunsky, Chaykel. 1921. From the Vilner Ghetto: Types and Shadows. Vilna: The Association of Hebrew Writers and Journalists in Vilna. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, Arie. 1993. From Brody to The Land of Israel and Back (The Tombstone of Malka bat Yitzhak Babad). Zion 58: 107–13. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, Arie. 1998. Mysticism and Messianism: From Luzzatto to the Vilna Gaon. Jerusalem: Maor Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, Arie. 2006. Hastening Redemption: Messianism and the Resettlement of the Land of Israel. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, Arie. 2007. The Return to Jerusalem: The Jewish Resettlement of Israel, 1800–1860. Jerusalem: Shalem Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, Arie. 2012. The Gaon of Vilna and his Messianic Vision. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Naveh, Joseph. 1978. On Stone and Mosaic: The Aramaic and Hebrew Inscriptions from Ancient Synagogues. Tel Aviv: Israel Exploration Society. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Rivlin, Yosef Yoel. 1959. The Link of the Jews of Lithuania to the Land of -Israel. In The Jews of Lithuania. Edited by Avraham Ya’ari. Tel Aviv: I. Am HaSefer, pp. 457–63. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Rodov, Ilia. 2003. The Development of Medieval and Renaissance Sculptural Decoration in Ashkenazi Synagogues from Worms to the Cracow Area. Ph.D. thesis, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Rodov, Ilia. 2013. “With Eyes toward Zion:” Visions of the Holy Land in Romanian Synagogues. QUEST. Issues in Contemporary Jewish History 6: 138–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rupeikienė, Marija. 2008. A Disappearing Heritage: The Synagogue Architecture of Lithuania. Vilnius: E. Karpavičius Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, Moïse. 1907. Rapport sur les inscriptions hébraïques de l’Espagne. Nouvelles archives des missions scientifiques et littéraires 14. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale. [Google Scholar]

- Steinschneider, Hillel Noah Maggid. 1900. Book of the City of Vilna (Sefer Ir Vilna). Vilna: Romm. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Sukenik, Eleazar Lipa. 1934. Ancient Synagogues in Palestine and Greece. London: British Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Yahalom, Joseph. 1981. Piyyut as Poetry. In The Synagogue in Late Antiquity. Edited by Lee. I. Levine. Pennsylvania: American Schools of Oriental Research, pp. 111–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yardeni, Ada. 2002. The Book of Hebrew Script History, Palaeography, Script Styles, Calligraphy and Design. London: The British Library and Oak Knoll Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The researchers involved in the Vilna Synagogue and Shulhoyf Research Project are Dr. Jon Seligman—Israel Antiquities Authority; Zenonas Baubonis & Justinas Račas—Kultūros paveldo išsaugojimo pajėgos; Prof. Richard Freund—University of Hartford; Prof. Harry Jol—University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire; Prof. Phillip Reeder—Duquesne University. See: www.seligman.org.il/vilna_synagogue_home.html. |

| 2 | LVIA—Lithuanian State Historical Archives (Lietuvos Valstybes Istorijos Archyvas). |

| 3 | According to Levin (2012, p. 289, n. 54), these drawn by Roman Sigalin and Jerzy Berliner of the Institute of Polish Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology (Zakład Architektury Polskiej Politechniki Warszawskiej) and their copies redrawn by Arkadii Konduralov (1883–1971) in 1949 are kept in Archives of the Cultural Heritage Centre, Vilnius, Nos. 418–21. |

| 4 | With no colour photographs or verbal descriptions detailing the colouring of the interior of the Great Synagogue, we rely on the surprisingly documentary painting of the interior of the edifice produced by Mark Chagall during his visit to Vilna in 1935 (Levin 2012, p. 288, fig. 18). The colouring of this painting we know to be accurate as it matches the surviving blue and red shield, now displayed in the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum, once set above the doors of the Torah ark and now confirmed from coloured pieces of plaster from the bimah discovered during the excavation itself that also match Chagall’s painting. |

| 5 | Steinschneider (1900, p. 92, n. 1) describes the stone as being of red marble, which it clearly is not. Lunsky (1921, p. 56) goes on to claim that the stone originates in Tiberias, also an impossibility as Tiberias-sourced stone is either black basalt or white limestone. The stone used for the inscription is probably a regionally sourced red sandstone on unknown origin. |

| 6 | The inscription is not visible in any of the photographs known to this author. It was probably covered by a cloth draped over the Torah reading table that can be seen in numerous images. |

| 7 | The letter “ר” had originally been inscribed with the letter “ת” but had been corrected by filling in the bottom stroke of the letter. The abbreviation אב”ר is unusual and is explained by Steinschneider (1900, p. 92, n. 1) as “אמנו בת רב” (our mother, daughter of Reb or Rabbi). |

| 8 | The Hebrew word עליה (aliyah), literately “ascent”, relates to emigration to the Land of Israel specifically. Aliyah, in its pre-Zionist religious context, was identified as a commandment by rabbinic scholars, including the Rambam and the Gaon of Vilna (see note 18). |

| 9 | Given that in Ashkenazi tradition, a child is named only after a deceased relative, the name “Ḥayim, the son of Ḥayim” is unusual and may indicate that Ḥayim’s father passed away before his birth. |

| 10 | On the historiographic debate concerning the motivation of the aliyah of the students of the Gaon of Vilna to Eretz Israel at the turn of the 19th century, see below as well as note 18. |

| 11 | The first Jewish cemetery in Vilna, known as the Piramont or Šnipiškės cemetery, set across the Neris River from the Gediminas Tower, was founded in the 15th cemetery and remained in use until its closure by the Tsarist authorities in 1831. Fortunately, this cemetery, which was the resting place of the Gaon of Vilna and all the historic leading community figures, was documented by Steinschneider (1900) and Klausner (1935), before being razed by the Soviet authorities in 1949–50 for the construction of a sports hall. |

| 12 | See comment no. 4. |

| 13 | The graffities (Figure 13) carved into the face of the inscription slab included the the following initials: (1) “ICP, (?)32”; (2) “RPM” set within a scratched form of a house or church; (3) “SEM” inside the scratched form of a heart; and (4) “IHIL”. |

| 14 | The discussion of dedicatory inscriptions during the Second Temple period through late Antiquity in the Land of Israel and the Diaspora has received wide ranging attention—see: (Klein 1920; Frey 1936; Sukenik 1934, pp. 69–78; Foerster 1981: Hachlili 1998, pp. 401–13; Naveh 1978, pp. 4–16; Lipshitz 1967). |

| 15 | Piyyut: Jewish liturgical poems that developed in Spain and the Rhineland in the 10–11th centuries. Note the similar use of Biblical quotations and paraphrases. See: (Yahalom 1981; Foerster 1981, pp. 11–40). |

| 16 | Coincidentally, this inscription is cut, similar to that in Vilna, from red sandstone. The full text is as follows: הא]בן הזא[ת שבצד הארון] \ [עד]ה למר יע[קב איש כשרון] \ בכל שבת [ושבת בזכרון] \ להזכיר[ו עם ישיני חברון] (This stone at the side of the Ark / [is] a witness for Jacob, a man of talent / every Sabbath in memory / to remember him [saying his name] along with the sleeping men of Hebron” (Epstein 1896, p. 513; Böcher 1961, p. 99; Rodov 2003, p. 26, n. 30). |

| 17 | Significant inscriptions with direct and often messianic reference to Jerusalem and other places in Eretz Israel have also been found also in Spain on Jewish tombstones and dedicatory inscriptions of the 12th to 14th century in Leon, Toledo, Cordoba (Schwab 1907, pp. 261, 288–89, 367). |

| 18 | For studies on the visual portrayal of Jerusalem and other holy places in the Land of Israel in the synagogues of Europe, see: (Bergman 1997; Efron 1997; Goldberg-Mulkiewicz 1997; Rodov 2013). |

| 19 | The often-vitriolic debate over the past four decades concerning the motivation of the aliyah of the students of the Gaon of Vilna to Eretz Israel at the turn of the 19th century has developed into the establishment of two opposing schools of thought. Some, especially those who have personal connections to the Perushim or with backgrounds in religious Zionism, have proposed that a messianic ideal, spear-headed by the Gaon himself, was the motivation for this aliyah, as a precursor to modern Zionism (Rivlin 1959; Eliav 1978; Morgenstern 1998, pp. 144–79; Morgenstern 2006, 2007, 2012, pp. 271–288 etc.). Other researchers, especially those of secular scholarship, have rejected these proposals, seeing the Perushim and their aliyah as no more than the continuation of traditional religious migrations of Jews to Eretz-Israel, aimed at creating a scholarly Torah community in the Holy Land, with no connection to the development of modern political Zionism in the second half of the 19th century (Bartal 1994, pp. 41–48, 52, 236–264; Bartal 2011; Barnai 1995; Etkes 2015, 2019). |

| 20 | The name family name Shebtels (שבתל’ס ,שבתלס) appears in the references in a number of different phonetically spelled alternatives—Shepshils (שפשילס), Shepshilas (שעפשילס), and Shepshiller (שעפשילר), all derived from the name of Ḥayim’s father-in-law, Shabtai (ben Elḥanan Ḥefez) (Steinschneider 1900, p. 92, n. 1; Morgenstern 2012, p. 278, n. 109). |

| 21 | The date of the aliyah of R. Ḥayim is estimated on the basis of the inscription, which states that Ḥayim resided in Tiberias for 18 years prior to his death in 1787. |

| 22 | Steinschneider also provides multiple references to Shmuel’s son, Rabbi Yizhak Eliyahu Landau (Steinschneider 1900, pp. 92–98 and others), who was a noted Torah scholar in Vilna, and to other descendants of this important Rabbinical family. |

| 23 | Thanks are due to Yehuda Mizrachi-Zoref, Tzameret-Rivka Avivi, Rabbi Mordechai Motola, and Micha Carmon for pointing this out. |

| 24 | The addition of the community affiliation “Ashkenazi” to a grave marker in the Sephardi cemetery on the Mount of Olives was prevalent until the establishment of a separate Ashkenazi cemetery in 1855 (Eliav 1982, p. 129, n. 26). Multiple tombstones with the addition of the designation “Ashkenazi” can be located in the vicinity of the markers of Ḥayim and Sarah, some clearly associated with the followers of the Gaon of Vilna, such as Mordachai Petaḥya Ashkenazi (–1758) (Frumkin 1929, III, p.71); Shmuel Zanvill Ashkenazi (–1767); Sa’adya Ashkenazi (–1813) (Frumkin 1929, III, p. 164); Menaḥem Mendel from Shklov (–1827) (Frumkin 1929, III, p. 163); etc. |

| 25 | See: mountofolives.co.il/he/deceased_card/חיים-אשכנזי-haim-ashkenazi-2/#gsc.tab=0. |

| 26 | Ibid. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).