Yanagita Kunio and the Culture Film: Discovering Everydayness and Creating/Imagining a National Community, 1935–1945 †

Abstract

:No one dies so poor that he does not leave something behind.Blaise Pascal1

1. The Culture Film and Folklore Studies

1.1. The “Discovery” of Rural Japan

According to Tsumura, the total war system following the China Incident caused the nation to turn its gaze toward rural areas, and indeed, the number of films featuring villages suddenly increased in this period. As the editor of the bulletin of Fumin Kyōkai (Association for Enriching Japanese Nationals), Kimura Taijirō, stated:The impact of the China Incident on the politics and culture of Japan was profound in many respects. But the most significant is the nation’s interest in the “rural” (chihō) and “rural people”. In the context of total war and the creation of the military state, the problem is how to understand the particularity of rural Japan and develop it appropriately, with a view to the destiny of the nation as a whole, in an organic relation to the urban.

Kimura mentioned films such as Earth (Tsuchi, 1939), Airplane Roar (Bakuon, 1939), Nightingale (Uguisu, 1939), and later Horse (Uma, 1941) as good examples. Those are all feature films, but culture films were also subject to the same phenomenon. According to Aihara Shūji’s research, between January and June 1941, 58 of the 135 authorized culture films (43% of the total) were “related to domestic production and culture”. Within this category, films about “agriculture and farming” numbered 38, comprising 28% of the total (Aihara 1942).8 As Aihara argues, many of the 18 “natural science related” films could also be categorized as “agriculture and farming”, which indicates the rapidly growing interest in rural villages in culture films of the time (although this chaotic categorization also illustrates the confusion about this concept). Therefore, the culture film and folklore studies shared an overlapping interest in rural areas.9 Filmmakers were aware of this intimate relationship between culture films and folklore studies.10 As the cameraman Midorikawa Michio stated, addressing young filmmakers in the manual of the state-controlled Film Association of Imperial Japan:Recently, a particular cinematic genre of “peasant film” has appeared. As a critique of films that until now were too focused on the city, and for social reasons to do with the increased interest in rural villagers and farmers in the current circumstances, it is a clear step forward for Japanese cinema, which has finally developed into a cinema based on a comprehensive sense of the masses that includes rural villages and people.

The Japanese study of traditions and ethnology is limited to an extremely specific group of researchers, a state of affairs that we feel sure is closely linked to the current state of our lives. We put too much value on individualism due to our excessively open connection with the world.

As the emphasis in the quotation shows, what had been “discovered” was not something that had appeared recently. It had been there all along, but it did not attract any attention since it was too quotidian.However, in the current situation I am happy to see an important new movement that emphasizes Japanese cultural awareness. In fact, the leaders of this movement have never been asleep and good results will come from their example (…) We have come to the time when we should look back on tradition. We are becoming aware of the chaos which emerges if our lives do not take root in tradition.

1.2. Created/Imagined Japan

According to Kamei, the value of the film was the “discovery” of everyday life, and Snow Country played a decisive role in the process through which the culture film discovered everyday life. Snow Country contains scenery from various locations. Through this structure, the individual uniqueness of each place is removed. It neglects the diversity of the nation and creates/imagines a general image of “Japan”. For example, the film never focuses on poverty in the countryside or intense agrarian disputes. These views of rural Japan produced under the wartime totalitarian order concealed the harsh “reality” as well as contradictions between people in the nation.16 Following the remark on the turn to rural subjects quoted earlier, Tsumura Hideo went on to mention this deception hidden in the “discovery” of rural Japan:Among the films I have seen this year, although it is strange to say it in front of Mr. Ishimoto, Snow Country is one of the best. There is room for discussion in terms of technical aspects; however, I think it is a groundbreaking film because it raises the problem of rural Japan, though many people believe that the value of documentary films lies in showing exotic places, such as Umi no seimeisen [Lifeline on the Sea, 1933] produced by Yoko-cine and Dotō wo kette [Through the Angry Waves, 1937], Shanghai [1937], Nanjing [1938], and Beijing [1938] produced by Tōhō.

The concept of the national people (kokumin) should acquire a new interpretation in modern Japanese society. When considering the systematic idea of nation, it is essential to look differently at rural areas and their people than we have in the past. Rural areas and rural people will gain new value and meaning, which will give birth to a new idea of a Japanese nation.

2. Miki Shigeru and Yanagita Kunio

2.1. Living by the Earth (Tsuchi ni ikiru, 1941)

2.2. The People of the Snow Country (Yukiguni no minzoku, 1944)

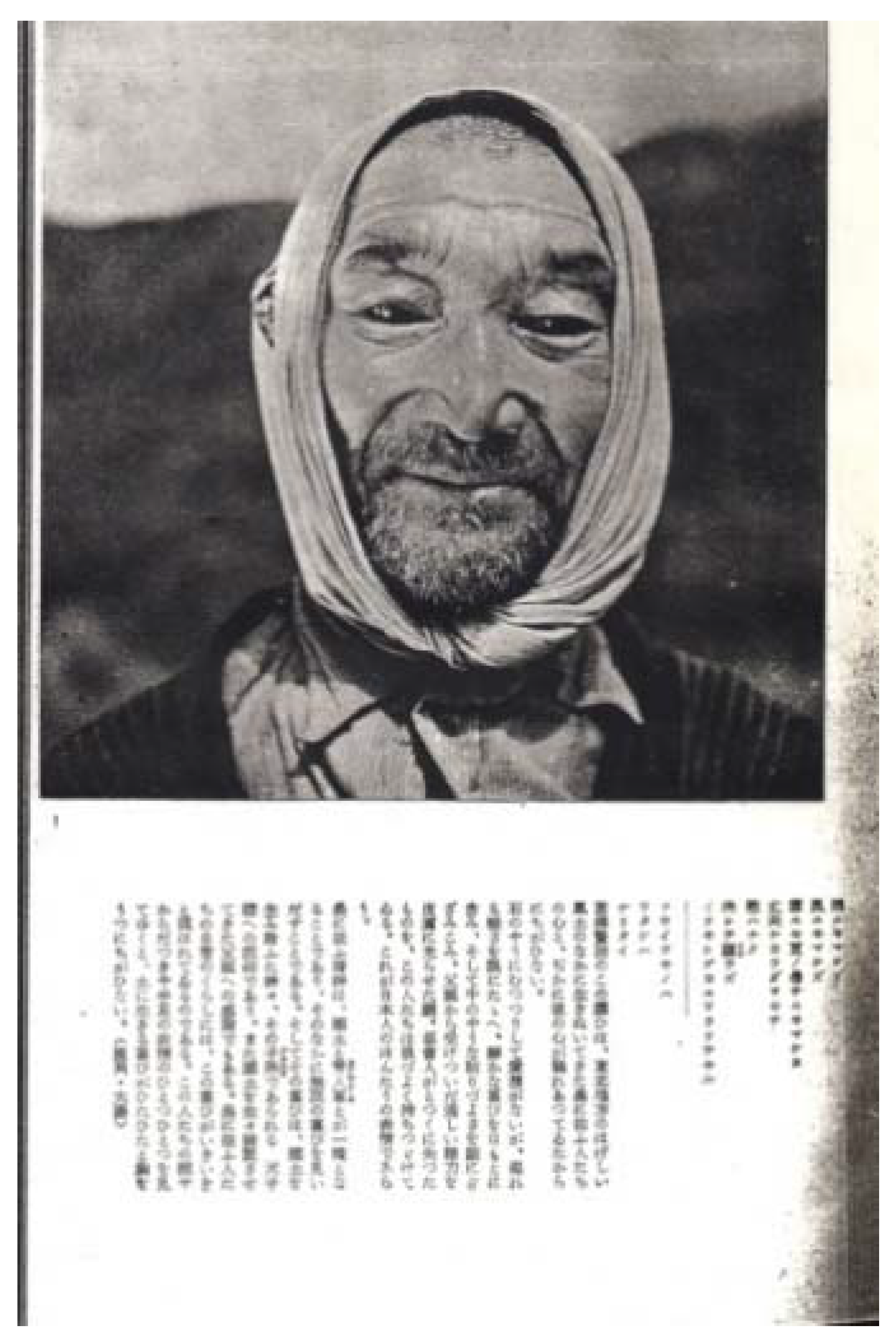

This caption strips the idiosyncratic and individualistic characteristics of the countryside and its people and clearly intends to provide a general image of “Japan” and the “Japanese”. The method of navigating towards a certain interpretation through a combination of photographs was originally developed by Natori Yōnosuke’s hōdō shashin (his translation of “reportage photography”) exhibited throughout the 1930s.27 The shock function of the best reportage photography is of course removed here, and the photographs are to a great extent shaped in accordance with the wartime system. However, because camera perception is fundamentally different from human perception, the intention of those who apply the caption is always shadowed by the possibility of being betrayed by the photograph itself. Therefore, when a photograph is used for a specific purpose, captions become obligatory (Benjamin [1936] 1995, pp. 559–600).Stone-like taciturnity, not sociable, but eyes overflowing with warmth, mouths hinting at quiet pleasure, a cow-like tenaciousness inscribed in wrinkles; the skin of their faces shines with a sturdy vitality inherited from their ancestors. These people still strongly and deeply possess what city people have long since lost. This is the true face of the Japanese people. (no page number).

The “delicate customs” of the remote region of Tohoku vanish, and those “customs” unfortunately cannot be captured in photographs. Of course, in this quotation, Yanagita may simply be referring to the problem of low light levels. There may not be sufficient light in the peasants’ houses, hidden under the deep snow in Tohoku, to capture those customs with a camera. However, this was not the first time that Yanagita made this kind of claim. In “Ethnic Art and the Culture Film” (Yanagita [1939] 2003b),29 Yanagita asserts: “the difficulty of documenting the uniqueness of ethnic art is a common problem among those engaged in folklore studies. The idea of films as a solution is something everyone comes up with”. By “ethnic art”, here Yanagita meant folk arts that fall into the category of song and dance practices (kabu shōyō), which cannot be preserved in the way that sculptures and drawings are. Moreover, they often embrace religious purposes and have a certain value when performed at night in a dark setting. Thus, even if one attempts to film it “as it is” with a camera, inevitably one has to move it to a bright place due to lighting issues. As a consequence, the putative essence of that “ethnic art” is lost:In any case, many delicate customs remain in the Tohoku area, rescued from oblivion because they are connected to the memory of previous generations. To put it another way, I think that compared to other regions there is a strong sense of taking customary activities seriously, and feeling unsatisfied when those customs are abandoned. But the time is coming when we can no longer say that is true. Now, at last, it is time to say goodbye. It is a great shame that so many of those scenes take place inside gloomy households that cannot even be recorded on photographs. Moreover, it cannot be said that the people of the snow country are satisfied with the feeling of somehow looking down on the lifestyle of their previous world.

Especially nuances, colors or something special in ethnic art cannot be represented well enough with the current Japanese film technology. For instance, solemn acts such as a small vow to the mask before putting it and the purification of one’s body by pouring cold water upon oneself before dancing are missed. Foreign films are better at depicting the atmosphere of churches because the centrality of musical instruments and hymns in Christianity creates a certain atmosphere.

What is clear here is that Yanagita sees the peculiarity of Japanese ethnic art as the impossibility of capturing it in a photographic image30 and that the inability to be recorded as a photographic image would lead to the “vanishing” (shōmetsu) of “ethnic art”. Japanese “ethnic art” manifests itself as a tragic evanescence that announces its own death.31 In that case, perhaps Yanagita’s words gain a special privilege, as he attends to Japan’s dying ethnic art. Images cannot fully represent that dying form; only Yanagita’s words can record them. Perhaps in this way, Yanagita’s text became unshakeable canon for Japanese folklore studies.32From this point of view, pessimistically, I think Japanese ethnic art will go extinct.

3. “Tunnel” into Snow Country

I feel empathetic toward the snow country. It was my first time to actually see it in a film, although I had heard a lot of stories. It was profoundly moving to see adults with snowshoes creating a path over the deep snow and leading a group of children to school.38

So, the film was a “tunnel” into the snow country. Yanagita was already charmed by this tunnel: all he had to do was go through it to see a landscape that had already been prepared. A “tunnel” that makes it possible for us to avoid reality—the discourses on the culture film and folklore studies from 1935 to 1945 constituted such a tunnel.I have to confess is that I was never able to travel during winter due to my work. After getting old, it was even more difficult to enter the life of the snow country due to my physical condition. Therefore, until now I have only been to hot and tropical places.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aihara, Shūji. 1942. Seisaku kikaku no shōsatsu, Shōwa 16 nen kaiko (Reflections on the Production Plan: A review of 1941). Bunka Eiga 2.1: 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1995. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Translated by Kubo Tetsuj. In Benjamin Korekushon 1: Kindai No Imi (Benjamin Collection 1: The Meaning of Modernity). Edited by Asai Kenjirō. Tokyo: Chikuma shobō, pp. 583–640. First published in 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1996. The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov. Translated by Akiko Miyake. In Benjamin Collection 2 Essay no Shisō (Benjamin Collection 2: Philosophy in Essays). Edited by Asai Kenjirō. Tokyo: Chikuma shobō, pp. 283–334. First published in 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural Department of the Imperial Rule Assistance Association. 1985. Chihō bunka shinkensetsu no konpon rinen oyobi tōmen no hōsaku (Fundamental Concepts and Policies for the New Construction of Rural Culture). In Shiryo Nihon Gendaishi 13: Taiheiyousensō ka no Kokumin Seikatsu (Archival Materials on Modern Japanese History vol. 13: National Life in WWII). Edited by Shirō Akazawa, Kenzō Kitagawa and Masaomi Yui. Tokyo: Ōtsuki shoten, pp. 248–50. First published in 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Donini, A. 1941. The Result of the First International Agrarian Film Competition. Translated by Kitazawa Tōhei. Bunka Eiga 1.6: 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, Jinshi. 2001a. Bunka suru eiga: Shōwa Jūnendai ni okeru bunka eiga no gensetsu bunseki. Eizōgaku 66: 5–22. Translated by Jeffrey Isaacs. 2002. Films That Do Culture—A Discursive Analysis of Bunka Eiga, 1935–1945. Iconics 6: 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, Jinshi. 2001b. Torarenakatta shotto to sono unmei: Jihen to eiga 1937–1941 (Shots that could not be taken and their fate: The China Incident and cinema, 1937–1941). Eizōgaku 67: 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, Jinshi. 2002. Kashi to fukashi no poritikkusu: Eiga Kojima no Haru to sōryokutaisei ka ni okeru ‘rai’ no hyōshō. (2) Kyōkai no hikinaoshi (Politics of the Visible and the Invisible: The Representation of Hansen’s Disease in the Film Spring on a Small Island under the Total War System. (2) Redrawing the boundary). UP 31.12: 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Harootunian, H.D. 1988. Figuring the Folk: History, Poetics, and Representation. In Mirror of Modernity: Invented Tradition of Modern Japan. Edited by Stephen Vlastos. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 144–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, Nyozekan. 1939. Kokusai eiga konkūru to Nihon (International Film Competitions and Japan). Nihon Eiga 4.8: 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ishimoto, Tōkichi. 1942. Bunka eiga geppyō (Monthly Review of Culture Films). Nihon Eiga 7.1: 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ivy, Marilyn. 1995. Discourses of the Vanishing: Modernity, Phantasm, Japan. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki, Masaya. 1997. Nōhon-shisō no shakai-shi: Seikatsu to kokutai no kōsaku (The Social History of Agrarianism: Intersection of Lifestyle and National Polity). Kyoto: Kyoto Daigaku Gakujutsu Shuppankai. [Google Scholar]

- Kamei, Fumio, Ken Akimoto, Yoshitsugu Tanaka, Kōzō Ueno, and Tōkichi Ishimoto. 1940. Nihon bunka eiga no shoki kara kyō wo kataru zadankai (Round-table on Bunka Eiga, from the beginnings to the Present Day). Bunka Eiga Kenkyū 3.2: 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, Ryūichi. 2000. Hōdō shashin no ichi: Journalism to propaganda no kōsaten (The Position of Reportage Photography: Crossroads of Journalism and Propaganda). Kokusai Kōryū 88: 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Karatani, Kōjin. 1993. Hyūmoa toshite no yuibutsuron (Materialism as Humor). Tokyo: Chikuma shobō. [Google Scholar]

- Karatani, Kōjin. 1997. Kindai Nihon no hihyō: Shōwa zenki 1 (Critics of Modern Japan: The early Showa 1. In Kindai Nihon no hihyō I: Shōwahen jō (Modern Japanese Criticism I: Showa, Part 1). Edited by Karatani Kōjin. Tokyo: Kōdansha, pp. 13–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki, Kenko, and Ken’ichi Harada. 2002. Okada Sōzō, Eizō no seiki: Gurafizumu, puropaganda, kagaku eiga (Sozo Okada: Century of Film. Graphism, Propaganda, Scientific Films). Tokyo: Heibonsha. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, Akira. 2001. Yanagita Kunio to minzokugaku no kindai: Okunoto no Aenokoto No 20 seiki (Yanagita Kunio and the Modernity of Folklore Studies: The 20th Century of Aenokoto in Okunoto). Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, Taijirō. 1939. Korekara no nōmin eiga (The Future of Peasant Films). Eiga to rebyū 5.9: 50. [Google Scholar]

- Kinema Junpō Sha. 1976. Sekai no ega sakka 31 Nihon eigashi (The World of Film Makers 31: The History of Japanese Film). Tokyo: Kinema Junpō Sha. [Google Scholar]

- Kitakouji, Takashi. 2003. Han-tōchaku no monogatari (Story of anti-arrival). In Eiga no seijigaku (The Politics of Cinema). Edited by Hase Masato and Nakamura Hideyuki. Tokyo: Seikyūsha, pp. 303–51. [Google Scholar]

- Koyasu, Nobukuni. 1996. Kindaichi no arukeorogii: Kokka to sensō to chishikijin (The Archeology of Modern Thought: Nation, War, and Intellectuals). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Makita, Shigeru. 1972. Yanagita Kunio. Tokyo: Chūō kōron sha. [Google Scholar]

- Midorikawa, Michio. 1940. Kameraman no seikatsu to kyōyō (Lifestyle and Education of the Cameraman). In Eiga satsueigaku dokuhon (Textbook for Filmmaking), vol. 1. Tokyo: Dai Nihon Eiga Kyōkai, pp. 46–84. [Google Scholar]

- Miki, Shigeru. 1941a. Tokushū kaisetsu Tsuchi ni ikiru (Special Comment on Living by the Earth). Bunka Eiga 1.10: 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Miki, Shigeru. 1941b. Kome to nōmin seikatsu ni kan suru eiga (Films about Rice and Peasant Life”). Bunka Eiga 1.1: 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mishima, Yukio. 1976. Yanagita Kunio Tōno Monogatari: Meichō saihakken (Yanagita Kunio’s The Legend of Tono: Rediscovery of a Masterpiece). In Mishima Yukio zenshū (The Collected Works of Mishima Yukio), vol. 34. Tokyo: Shinchōsha, pp. 399–402. [Google Scholar]

- Mura, Haruo. 1963. Yanagita sensei to kiroku eiga (Mr. Yanagita and Documentary Films). In Teihon Yanagita Kunio shū geppō (Monthly Report of the Revised Collected Works of Yanagita Kunio), vol. 23. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, pp. 179–80. [Google Scholar]

- Murai, Osamu. 1995. Nantō ideorogii no hassei, Yanagita Kunio to Shokuminchi-Shugi (The Origins of the Southern Islands Ideology: Yanagita Kunio and Colonialism), Revised Edition. Tokyo: Ōta Shobō. [Google Scholar]

- Murai, Osamu. 1999. Metsubō no gensetsu kūkan: Minzoku, kokka, kōshōsei (The Discursive Space of Ruin: The People, The State, and Oral Traditionality). In Sōzō Sareta Koten: Kanon Keisei, Kokumin Kokka, Nihon Bungaku (Imagined Tradition: The Formation of the Canon, the Nation State, and Japanese Literature). Edited by Shirane Haruo and Suzuki Tomi. Tokyo: Shinyōsha, pp. 258–301. [Google Scholar]

- Rotha, Paul. 1938. Bunka Eigaron. Translated by Atsugi Taka. Kyoto: Daiichi Geibunsha. [Google Scholar]

- Satō, Kenji. 1987. Shibusawa Keizo to Attic Museum (Keizo Shibusawa and the Attic Museum). In Nihon no kigyōka to shakai bunka jigyō: Taishō-ki no fuiransoropii (Japanese Entrepreneurs and Socio-Cultural Projects: Philanthropy during the Taisho Era). Edited by Kawazoe Noburo and Yamaoka Yoshinori. Tokyo: Tōyō Keizai Shinpōsha, pp. 124–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shigeno, Tatsuhiko. 1941. Tsuchi ni ikiru. Eiga hyōron 1: 11. [Google Scholar]

- Shikiba, Ryūzaburō. 1941. Eiga to chihō bunka (Films and Rural Culture). Eiga Hyōron (Film Review) 1.2: 79. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Toshio, Hideo Tsumura, and Shigeru Miki. 1941. Satsueisha no seishin ni tsuite; Tsuchi ni ikiru wo megutte (The Spirit of the Cameraman: On Living by the Earth”). Eiga Gijutsu 2.5: 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Taut, Bruno. 1939. Nihonbi no saihakken (Rediscovering the Beauty of Japan). Tokyo: Iwanami shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Tsumura, Hideo. 1941. Eiga to kanshō (Films and Appreciation). Tokyo: Sōgensha. [Google Scholar]

- Tsurumi, Tarou. 1998. Yanagita Kunio to sono deshitachi: Minzokugaku o manabu Marukusu shugisha (Yanagita Kunio and His Students: Marxists Studying Japanese Ethnography). Kyoto: Jinbun Shoin. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagita, Kunio. 1998. Minkan denshō ron (Folklore Theory). In Yanagita Kunio zenshū dai 8 kan (Collected Works of Yanagita Kunio vol. 8). Tokyo: Chikuma shobō, pp. 3–194. First published in 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagita, Kunio. 1998. Kyōdo seikatsu no kenkyū-hō (Methodology for the Study of Regional Ways of Life). In Yanagita Kunio zenshū dai 8 kan (Collected Works of Yanagita Kunio vol. 8). Tokyo: Chikuma shobō, pp. 195–368. First published in 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagita, Kunio. 2003. Bunka eiga to minkan denshō (The Culture Film and Folk Stories). In Yanagita Kunio zenshū dai 30 kan (Collected Works of Yanagita Kunio vol. 30). Tokyo: Chikuma shobō, pp. 177–79. First published in 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagita, Kunio. 2003. Minzoku geijutsu to bunka eiga (Ethnic Art and the Culture Film). In Yanagita Kunio zenshū dai 30 kan (Collected Works of Yanagita Kunio vol. 30). Tokyo: Chikuma shobō, pp. 232–34. First published in 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagita, Kunio, and Miki Shigeru. 1944. Yukiguni no minzoku (People of the Snow Country). Tokyo: Yōtokusha. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagita, Kunio, Ken Domon, Hiroshi Hamaya, Toshio Tanaka, and Manshichi Sakamoto. 1943. Yanagita Kunio shi wo kakonde; minzoku to shashin zadankai (Around Yanagita Kunio: The National People and Photography Round-Table). Shashin Bunka 27.3: 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Saburō. 1935. Oga Kanpū sanroku nōmin shuki (Notes of an Oga Kanpū Farmer). Tokyo: Achikkumyūzeamu. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Saburō. 1938. Oga Kanpū sanroku nōmin nichiroku (Journal of an Oga Kanpu Farmer). Tokyo: Achikkumyuūzeamu. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Quoted in (Benjamin [1936] 1996, p. 313). |

| 2 | The former reprinted in (Yanagita [1934] 1998), the latter in (Yanagita [1935] 1998). The advertisement when the first book was published by Kyōritsusha read: “The first systematic study of folklore” in Tabi to densetsu (Travel and Folklore), October, 1934. |

| 3 | It is also significant that many introductory texts on “folklore” were translated in the 1920s. See (Makita 1972, pp. 131–32). |

| 4 | Folklore Theory begins: “It seems a little early to use the word Folklore Studies as a common noun in Japan”. See also (Karatani 1993, pp. 258–80). |

| 5 | This was translated by Jeffrey Isaacs as “Films That Do Culture—A Discursive Analysis of Bunka Eiga, 1935–1945” in Iconics 6 (2002). |

| 6 | In a narrow definition, culture films were only films that had been authorized by the Ministry of Education according to the Film Law criteria. However, it was clear from the discourse on culture films at the time that the definition was more inclusive than that. |

| 7 | The ideal peasant film mentioned in this article was the American film Our Daily Bread (1934), which shows that the concern was not limited to Japan. For instance, the first International Agrarian Film Competition was held at the 15th general meeting of the International Institute of Agriculture in Rome in 1940. See (Donini 1941). |

| 8 | The background to this phenomenon was a letter from the Home Office that stated, “films about production, especially agriculture, should be encouraged”, printed in Kinema Junpō, January in 1941, and quoted in (Kinema Junpō Sha 1976, p. 83); the promotion of rural lives was encouraged in (Cultural Department of the Imperial Rule Assistance Association [1941] 1985). |

| 9 | The interest in rural Japan was thematized in literature earlier than film. For instance, Before the Dawn (Yoakemae) by Shimazaki Tōson was completed in 1935, followed immediately by the serialization of Kawabata Yasunari’s Snow Country (Yukiguni). Uchida Tomu’s Earth was also based on the original novel by Nagatsuka Takashi published in 1910, though it was influenced by the success of an adaptation by the Shin Tsukiji troupe in the Tsukiji little theatre. Shikiba Ryūsaburō, who joined Yanagi Sōtetsu’s Mingei movement, stated that it was literature that first found value in rural Japan, and this “literature of the soil” (distinguished from proletarian literature) was inherited by the culture film (Shikiba 1941). |

| 10 | Reflecting on the culture films of 1940, Tsumura Hideo pointed out an impasse in their production. Since “relying only on culture film producers might limit the range of expression (…) a way forward for exploring rural lives would be to get advice from Yanagita’s Association of Folklore. Understanding folklore studies is also necessary” (Tsumura 1941, p. 145). |

| 11 | See (Murai 1995; Koyasu 1996, pp. 1–54). |

| 12 | See (Fujii 2001a). |

| 13 | Yukiguni, first screened at the Hibiya Theatre, which specialized in Western films, was unexpectedly successful (it was rare to screen Japanese films in cinemas for Western films). The award from the Ministry of Education was accompanied by the citation: “depicting snow in Japan’s coastal area, it succeeded not only as documentation but also as an indication of the proper way to make culture films” (Advertisement for Yukiguni in Nihon Eiga 5.6, 1940, p. 117). There must also have been pressure from the letter from the Home Office, mentioned in note 8 (Earth was also given an award at the same time). |

| 14 | See (Kitakouji 2003). |

| 15 | Regarding this point, the architect Bruno Taut, who stayed in Japan during the 1930s and taught the idea of Japanese beauty, is significant here. His widely read Nihon no bi no saihakken (The Rediscovery of Japanese Beauty) was published by Iwanami Shoten in 1939 and included a reference to snow country (Akita in winter) (Taut 1939). |

| 16 | It is interesting to note that the perspective on rural Japan at that time seemed to avoid Hokkaido. The difference of its indigenous people was violently erased as a result of the assimilation policies of the Japanese empire. Under the nationalist regime, Hokkaido was probably too problematic a subject. In fact, this land had dairy farms with vast fields that did not fit within the generalized image of the “Japanese countryside” of the time. |

| 17 | See (Fujii 2001b). |

| 18 | Miki stated his motive for making Living by the Earth in the following way: “peasant customs have changed dramatically in recent years. From straw sandals to rubber shoes, straw rain coats to rubber rain coats, sedge hats to service caps. Women are influenced by the cities and in the summer wear lightweight clothes. They eat curry and rice, ice lollies, Chinese ramen and dumplings. Villages are changing and it is difficult to find peasants like those of the old days” (Miki 1941a, p. 54). |

| 19 | Editors’ note: see Disuke Miyao. “What’s the Use of Culture? Cinematographers and the Culture Film in Japan in the Early 1940s” in this issue for a discussion of the debate. |

| 20 | The journal Bunka eiga features photogravures entitled “Tsuchi ni ikiru hitobito” (People Who Live by the Earth). Additionally, a Special Issue on Living by the Earth was published before the completion of the film. |

| 21 | For more information on Keizo Shibusawa, see (Satō 1987). |

| 22 | Notes of an Oga Kanpū Farmer included many pictures taken with a 16-mm film camera that Shibusawa had bought in London. It is said that Shibusawa used to bring this camera on his travels to produce ethnographic visual materials (Kawasaki and Harada 2002, p. 22). As I will discuss later, this use of images was unusual in contemporary Folklore Studies. |

| 23 | See (Kikuchi 2001, pp. 149–51). |

| 24 | Later regarded as a pioneering work of folklore studies, Suzuki Bokushi’s Hokuetsu Seppū (1936–1942) was revised by the meteorologist Okada Takematsu, Yanagita’s childhood friend, and published in 1936 by Iwanami Bunko. The development of the Life Composition Movement (seikatsu tsuzurikata undō) and “amateur writing” (shirōto bungaku) should be considered in the same context. For an account of amateur writing, see (Fujii 2002). |

| 25 | Miki pointed out that the popularization of the solar calendar in Japanese society after the China Incident changed annual customs in rural areas dramatically (Yanagita and Miki 1944, p. 31). The solar calendar in Japan was adopted in 1873; however, there were some areas that still used the old lunar calendar in the 1930s. |

| 26 | According to Murai Osamu, the publication of Folklore Studies was excepted from the suppression of speech under the militaristic government (Murai 1999, p. 263). In that respect, folklore studies accommodated itself to the wartime system. |

| 27 | On reportage photography, see Chapter 11 in (Kawasaki and Harada 2002). Also (Kaneko 2000). |

| 28 | Iwasaki Masaya makes the important argument that agrarianism, originally a purely modernist movement, had a fantasy of modern materiality and was not accepted by peasants engaged in a traditional way of life. Eventually, in order to gain support from the peasants, agrarianism performed an about-face (tenkō) and was assimilated into fascism and imperialism (Iwasaki 1997). |

| 29 | In Nihon Eiga 4.13. At that time, Yanagita often published in film and photographic magazines and attended meetings associated with visual arts. Those publications were not included in Teihon Yanagita Kunio shū geppō (Monthly Report on the Revised Collected Works of Yanagita Kunio) so this material is not easily available for reference. |

| 30 | This impossibility of recording corresponds to Yanagita’s category of spiritual phenomena, as opposed to tangible culture and linguistic arts, in his classification of the materials of folklore studies (Yanagita [1935] 1998). |

| 31 | Mishima Yukio states, “Even in the beginning, folklore studies smelled like death”, in (Mishima [1970] 1976). For the idea of extinction (metsubō) in Yanagita, see (Murai 1999) and also (Ivy 1995). |

| 32 | The distrust that Yanagita had for photography was based on the assumption that people tended to perform in front of cameras (Yanagita et al. 1943, pp. 40–41; Kikuchi 2001, pp. 151–64). In fact, Yanagita felt dissatisfied by the images of the peasants in Living by the Earth, which he thought betrayed an awkwardness caused by a consciousness of the camera (Mura 1963). Although Yanagita’s distrust was understandable, such an attitude is connected to the process by which his written texts were canonized, and visual materials that could contradict them were suppressed. |

| 33 | H.D. Harootunian (1988) sees a connection between Yanagita the ethnologist and his youthful rejection of photographic realism when he was active as a romantic poet and denied the value of the genre of literary sketch (shaseibun). |

| 34 | The meaning of this declaration of victory was made clear in (Yanagita [1939] 2003a). Yanagita, who avoided any systematic theorization, fell into certain contradictions. For instance, at the end of his “Stories of the Snow Country” article, Yanagita hoped that visual materials would record the expansion of the Great East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, but even that was due to a specificity of Japan that had no parallel: “We Japanese have a capacity to sense things with the eyes more than in words, which is very rare among the rest of the world” (p. 20). Yanagita in another discussion also mentions the possibility of visual materials for recording intangible culture; however, he seems not to be satisfied with the technology of the time (Yanagita et al. 1943, p. 40). |

| 35 | The following statement by Miki should be understood in this context: “culture films should not be ‘directed’. Preparing scripts and directing according to the scenario…this method is not appropriate for documentary films” (Tanaka et al. 1941, p. 41). |

| 36 | Culture films and folklore studies were also similar in that they functioned refuges for Marxists during the war (Fujii 2001a; Tsurumi 1998). |

| 37 | It is also significant that Yanagita compared a central principle of folklore studies, the method of “substantiation by multiple occurrence” (jūshutsu risshōhō) to composite photography (kasane dori shashin) (Yanagita [1934] 1998, p. 62). |

| 38 | Advertisement for Yukiguni in Bunka Eiga, 1939, vol. 2, issue 4, no page number. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fujii, J. Yanagita Kunio and the Culture Film: Discovering Everydayness and Creating/Imagining a National Community, 1935–1945. Arts 2020, 9, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020054

Fujii J. Yanagita Kunio and the Culture Film: Discovering Everydayness and Creating/Imagining a National Community, 1935–1945. Arts. 2020; 9(2):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020054

Chicago/Turabian StyleFujii, Jinshi. 2020. "Yanagita Kunio and the Culture Film: Discovering Everydayness and Creating/Imagining a National Community, 1935–1945" Arts 9, no. 2: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020054

APA StyleFujii, J. (2020). Yanagita Kunio and the Culture Film: Discovering Everydayness and Creating/Imagining a National Community, 1935–1945. Arts, 9(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020054