Ullman and Sharabani relate to sand as matter that cannot be contained within fixed boundaries, drifting across and beyond borders and thwarting the promise of firm ground. Sand, in their works, is the quintessential

terra infirma, as in Rogoff’s study of “unhomed” geography (

Rogoff 2000, p. 7). In what follows, I consider Ullman’s precariously balanced earth sculptures and perforated sand tables, in conjunction with Sharabani’s VR projections on sand and digitally manipulated views from Google Earth, which hone in on geographical sites that resonate with histories of Jewish migrations. In approaching the resonances between these two bodies of work, which together span over five decades, I draw on theoretical and methodological tools developed to address migratory aesthetics by Mieke

Bal (

2007), Jill

Bennett (

2005,

2011), and Sam Durrant and Catherine Lord (

Durrant and Lord 2007). I work with Bal’s definition of migratory aesthetics as “a ground for experimentation that opens up possible relations with ‘the migratory’” (

Bal 2007, p. 23), and with Bennett’s assertion that “[m]ore than the sum of art works about migration, Migratory Aesthetics invokes aesthetics in the strong sense, as an epistemic project […] reorganizing affects to redetermine a perceptual landscape” (

Bennett 2011, pp. 118–20). I adopt a primarily, albeit not exclusively, phenomenological approach to migratory aesthetics, investigating, in Durrant and Lord’s terms, “the degree to which the art work itself

becomes migratory” (

Durrant and Lord 2007, p. 13).

Bennett, connecting the politics and phenomenology of contemporary aesthetics, urges us to “configur[e] the political through the aesthetic by describing the particularity of what art does” (

Bennett 2011, p. 120). Developing my argument in this vein, I attend closely to the working of sand as a material medium inviting tactile engagement, while at the same time I attend to the semantic weight of this medium in terms of its connotation of shifting ground. The artworks discussed in this paper weave a migratory fabric, affording affective and somatosensory engagement through the employment of sand. In their subtle poetics, they part ways with more overtly political strains of Israeli art, such as the bitingly ironic work arising from the 1990s wave of Russian immigration to Israel, discussed by Yael Guilat and by Emma Gashinsky in this issue. In Bennett’s terms, Ullman and Sharabani do not speak through politically explicit “trauma discourse” (

Bennett 2005, p. 2). Rather, their art evinces an “endeavor to find a communicable language of sensation and affect with which to register something of the experience of traumatic memory” (ibid., p. 2). Whereas Nicolas

Bourriaud’s (

2010) concept of radicant aesthetics assumes some kind of metaphorically solid ground, supporting meandering rootings, I show how Ullman and Sharabani question this very assumption. The intergenerational encounter between these two artists takes place on shifting sands, as it were. Through the trope of floating and drifting bodies of earth, whether precariously balanced or suggestively hardened—in Sharabani’s case, through digital manipulation—their installations spatialize migratory anxiety as it persists across generations, in Israeli society at large and in the two artists’ respective biographies, in particular. Aviva

Halamish (

2018) has discussed immigration as a key trait of Israeli society, asserting that not only has immigration been “the leitmotif of Israel’s history,” but it has “completely changed the demographic dispersion of the Jewish people in the world” (p. 107). Complex and meandering immigration routes have been, and are still, crucial to the formation of a particular type of migratory subject positions both within Israel and beyond its borders. Nadine

Blumer (

2011) has discussed the transnational nature of this “oft-cited paradigmatic diasporic group” (p. 1331), highlighting the inherent ambiguities of multiple belonging—between the primordial homeland of Israel, now become a real existential option, and “transnational ways of belonging that recognize the transgressive potential of diaspora to disentangle geography from identity” (p. 1344). While acknowledging the potential of transnationality to replace ethno-diasporic identity, Blumer concludes that only a balanced concept of diaspora and transnationalism can adequately “account for the ways in which ethno-diasporic identities are formed and sustained” (p. 1331).

Here, I attend to the oeuvres of two “subjects-in-aesthetic-process” (

Durrant and Lord 2007, p. 11) caught in cycles of mobility and multiple belonging. Born in Israel to parents who immigrated under persecution from 1930s Germany and 1950s Iraq, respectively, both Ullman and Sharabani enact resonant migratory “returns.” As I go on to discuss, Ullman has transported earth from Israel to Germany—his parents’ country of origin, which they fled in the 1930s following the rise of the Nazi regime. For his part, Sharabani has returned, via Google Earth, to the Iraqi city of Basrah, which his grandparents left with the artist’s then-infant parents in the wake of bloody anti-Jewish riots.

1 Notably, hyphenated Jewish identities across the globe had always been transnational. With a small but persistent Jewish population remaining in Israel since before the Roman age, centuries-old diasporic Jewish communities, such as those in Germany and Iraq mentioned here, never ceased regarding themselves as in exile from their land of origin. In their surrounding non-Jewish environments, they had also been regarded as (often unwelcome) exiles from a prior homeland. When immigration, or return, to the primordial land of origin became an actual option in the late 19th century, immigration to Israel (both before and after the establishment of the political state in 1948) was experienced simultaneously as displacement and as a homecoming, invested with hope for a new life free of anti-Semitic harassment. It is against this background that this paper approaches the deployment of soil and sand as media in Israeli art. Bennett’s phenomenological reading of migratory aesthetics calls attention to how politics “are enacted […] at the level of material and sensate processes” (

Bennett 2011, p. 111). I propose to attend to the “transactive” (

Bennett 2005, p. 7) mode in which Ullman and Sharabani’s sand installations tap into the politics and trauma of displacement and return.

1. Sharabani, Ullman, and the Video Card (2014)

In Tel Aviv in 1939, Micha Ullman was born to parents who had fled Nazi Germany in the early 1930s, when their perceived homeland became a deadly trap for Jews. While based in Israel throughout his life, Ullman has led an internationally successful artistic career since the 1970s, in the course of which he has exhibited work and taught around the world and in Germany in particular (

Zalmona 2011). About a generation later, Sharabani was also born in Tel Aviv, which by then had become a major city and the capital of Israeli business and culture. Sharabani’s grandparents immigrated from Iraq in 1951 (communication with the author, October 2019), along with the majority of Iraq’s Jewish population—130,000 out of 135,000 Iraqi Jews abandoned their homes and property in the space of six months, fleeing anti-Zionist (which soon tipped into anti-Semitic) harassment. To exacerbate matters, they were compelled to give up their citizenship by a specially legislated Iraqi law (

Bashkin 2012). In 1999, Sharabani, like many young Israeli artists, left Israel to study in New York, where his career as a visual artist began. In 2007, he returned to Tel Aviv, where he lives with his family and bases his international artistic career. In a curious turn of events, the owner of Sharabani’s rented studio space in Tel Aviv belongs to the same generation of German-Jewish immigrants as Micha Ullman. In concluding this paper, I revisit this coincidence, which echoes with radicant resonances.

It is also notable, in this respect, that Sharabani’s international career as a media artist involves close trans-Atlantic collaborations with his two brothers, one of whom works in media in New York, the other in the cyber-tech world of Palo Alto, California. Together, they form a truly radicant triad. Traveling back and forth between Tel Aviv and global art centers of the East and West Coasts of the US, Sharabani may be regarded as caught in what Anne Ring Petersen describes as circular migration: “the migratory pattern of artists, who have chosen to be based in their home country but must live as globetrotters and engage with many different cultures and places in order to pursue international careers” (

Petersen 2017, Kindle location 2423 of 6382).

Yet, undergirding my argument is not the relatively privileged condition enjoyed by Ullman and Sharabani, of internationally acclaimed globetrotting artists. Rather, both artists might be regarded, compellingly if provocatively, as second-generation refugees: the offspring of “parents who fled persecution in their country of origin” (

Chimienti et al. 2019, p. 3). This sub-category of second-generation immigrants has recently received scholarly attention (

Chimienti et al. 2019;

Bloch and Hirsch 2018;

Bloch 2018). As demonstrated in Bloch’s study of second-generation refugees from Asia and the Middle East, born and residing in London, “[t]he refugee cycle does not end with the refugee generation, but continues through postmemory that is inherited through narratives, but also through the gaps and silences” (

Bloch 2018, p. 662).

A subtly articulated anxiety imbues Ullman’s perforated sand tables, earth sculptures, and pits dug in the ground, the most famous of which is the Berlin

Library (1994), a Holocaust memorial that consists of an underground library of empty shelves covered by a pane of glass (

Figure 1). This ghost library, submerged beneath Berlin’s Bebelplatz, is dedicated to the memory of the burning of books at that very site in May 1933. I consider Ullman’s

Sand Table (2019;

Figure 2) and fragile sand installations, alongside Sharabani’s video projections onto sand (

Figure 3) and his latest Google Earth series of

Virtual Territories (2019–2020), in the context of Israel’s historical implication in cycles of migration and refugeehood. While the scope of this paper does not allow full elaboration of the tangled coexistence of Jews and Arabs in Israel, it is crucial to keep in mind the existential clash that erupted between Jewish refugees, seeking a safe haven from antisemitism in Israel since the late 19th century, and the local Arab population, assuming the Palestinian denomination.

2 Culminating in the 1948 conflict over the establishment of the state of Israel, and the consequent formation of a Palestinian refugee population, this conflict has remained unresolved. The intergenerational encounter between Ullman and Sharabani, taking place through the precarious medium of sand, thus brings into focus the poetics and problematics of ground, place, and memory in Israeli art in light of its extremely charged history and its explosive present.

Ullman and Sharabani first met in 2014 during the mounting of an exhibition at the Umm al-Fahm art gallery.

3 Sharabani documented Ullman on his quest for different types of earth and in his efforts to prepare the earth for his installation. He also documented on video a strikingly frank, and politically charged, conversation between Ullman and Said Abu Shakra,

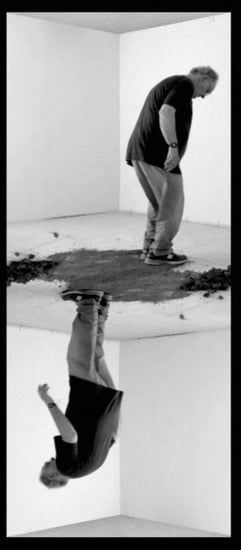

4 touching on histories of displacement and return, the complexities of national identity, and ownership over the land—the core conflictual issues underlying the extremely uneasy coexistence of Jews and Arabs in Israel. The encounter between Sharabani and Ullman at the Umm al-Fahm art gallery is reflected in Sharabani’s video,

Card (2014;

Figure 4), a video work depicting Ullman in the process of preparing earth for his installation at the gallery. Ullman seems absorbed in a strange ritual dance, which he performs to the grating sound of earth-crumbs cracking under the pressure of his feet. Sharabani duplicated and flipped the video image, producing a disorienting spatial ambiguity that recalls the architectural conundrums of Giovanni Piranesi (1720–1778) or M.C. Escher (1898–1972). Note that Ullmann is positioned simultaneously atop and beneath a floating layer of earth, despite the obvious fact that the gallery floor can only be seen from above. Sharabani heightened this effect of disorientation through a series of spatiotemporal and acoustic disruptions. The video opens with a view of an empty gallery space, save for three mounds of soil piled on the impossibly suspended floor. A sound of grinding, issuing from an invisible source, precedes Ullman’s entry by ten long seconds. An additional nineteen seconds elapse before the activity that actually explains the grinding sound begins. In fact, in this fifty-seven-second video, sound and image are never played congruently. Over its entire duration,

Card is unsettlingly dissonant. The paradoxical spatiality of the video culminates when Ullman enters the space upside down, as it were (

Figure 4, right), a whole second before his upright mirror-self walks in. What is more, Ullman’s movements are not in synch with those of his flipped doppelgänger. Indeed, the video ends with the “upright Ullman” leaving the space while his double lingers behind. Here, it is productive to recall Mieke Bal’s attribution of heterochrony—the experience of time “as multiple [and] heterogeneous” (

Bal 2011, p. 213)—to the aesthetics of “the social phenomenon of the movement of people” (p. 212). Miguel Hernández-Navarro, who collaborated with Bal on the video-art exhibition

2MOVE: Double Movement/Migratory Aesthetics (2008), suggested that migratory experience unfolds within a “temporal space which is not Euclidian, but rather möbian” (

Hernández-Navarro 2011, p. 195). In light of Hernández-Navarro and Bal’s concept, Sharabani’s uncanny flipped cell might qualify as a spatiotemporal Möbius strip, a disorienting space-time conundrum that taps into the uncertain status of ground in migratory existence.

Card serves as my point of entry into an investigation of the two artists’ engagement with sand. The discussion will follow two major axes on which the works of Ullman and Sharabani interface. The first category of works, which I refer to as “treacherous sands”, encompasses installations involving sand tables and other containers of soil. The second category, “fragile traces”, covers works that feature architectural ground plans modeled in sand. Together, these categories speak to the notion of

terra infirma (

Rogoff 2000). Yet, I will argue that, alongside this recognition of impermanence, Ullman and Sharabani engage in a relentlessly optimistic attempt at solidifying and stabilizing eternally shifting grounds.

2. Treacherous Sands: Sand Tables and Other Containers

In Israeli culture, sand is associated with the Mediterranean coast, which constitutes the country’s Western border and its almost exclusive gateway to Europe and beyond. Established in 1909 on the sandy stretches of the Mediterranean coast, the city of Tel Aviv has come to epitomize the resurrection of the bi-Millennial Jewish diaspora in an old-new nation-state situated on historically coveted territory that is fraught with contemporary tensions. The name Tel Aviv signifies the emergence of spring (Aviv) from beneath an archaeological mound (Tel). It is often referred to as the city that sprang from the sands. At the same time, sand, like water, trickles across boundaries, defying borders and calling notions of solid ground and territorial fixity into question.

Sand tables, which consist of iron or steel boxes filled with sand or heavier red earth (

Hamra), form the primary point of intersection between Ullman’s and Sharabani’s bodies of work. Sharabani’s installation

Sand Box (2014; see

Figure 3) features minuscule virtual chairs projected onto a non-virtual sand table. In perfectly simulated movement, a pile of virtual chairs accumulates before collapsing into the sandy surface. The objects gradually submerge, as if in quicksand, only to reemerge seconds later in an eerie resurrection. All the while, at the extremes of the projection frame two human figures are each positioned uneasily on a row of chairs, attempting to place themselves impossibly across several chairs (

Figure 5). Their visible muscular unease recalls Mieke

Bal’s (

2008a, p. 35) assertion that “[migratory] experience, in addition to having to be historicized, needs to be kinetico-visualized”. Sharabani brings together moving image and actual, material sand, the latter functioning as a highly textured projection screen inviting tactile engagement. As such, the work has not only an augmented haptic appeal (

Marks 2002), but the “synesthetic fullness” (

Bal 2007, p. 34) and “sentient binding” (ibid., p. 26) that Bal highlights as key traits of migratory aesthetics.

In struggling to remain above ground, Sharabani’s digitally simulated chairs echo Ullman’s installation

Under, part of his exhibition

Sands of Time at

The Israel Museum (

2011).

Under featured sand sculptures of household items such as tables and chairs, which appeared submerged beneath the gallery floor. Ullman’s toppled chair (

Figure 6) consists of two rusty iron containers filled to the rim with red earth. With the surface of the mound inclined by exactly 35

0, a liminal angle preventing the thinly sifted dry earth from spilling over the sides, the work maintains an extremely fragile equilibrium. Ullman creates objects that, despite appearing solid, in fact barely hold together.

Chair is a case in point. In part, the work’s appearance of solidity is down to the chromatic resemblance between rusty iron and red soil. As Ullman has explained in a video interview on the occasion of his 2011 exhibition at the Israel Museum, iron and sand both conflict and converge. The similar colors of sand and iron, he said, camouflage their diametrically opposed physicality. Whereas iron is solid and fixed, sand is fluid and dispersive. It is held within the boundaries of the iron container in a strained and tense balance (

The Israel Museum 2011). Although it appears solid, the carefully formed body of earth within the container is extremely vulnerable. It might be displaced by the slightest touch. To adopt Giuliana Bruno’s terms, the surface tension evident in this work compels sensory engagement, for it “holds affects in its fabric” (

Bruno 2014, p. 80). Needless to say, this chair cannot afford stable seating. Like Sharabani’s

Sand Box, Ullman’s chair sculpture undercuts the semantic function universally attributed to chairs, of providing ground and firm support. In the same move, these works transform the ground, uncannily, into quicksand.

Is this irony or bare anxiety? In addressing this question, I shall explore Ullman’s sand tables and earth sculptures in greater depth. A work from the

Containers (1988) series named

Midnight (

Figure 7) consists of a large iron container, which has been cast in the generic form of a house and holds a pyramid of red sand. Like the objects constituting the installation

Under, this sculpture relies on Ullman’s technique of keeping sand in a dangerous equilibrium while creating a deceptive impression of firmness. Taking up Freud’s uncanny in its original German formulation, we might say that if

Midnight is a home, it is profoundly

unheimlich. It is a home haunted by its own fragility.

Day (

Figure 8), another work in the

Containers series, is the obverse of

Midnight. It sets forth the same generic house but in negative form. Here, the home is a hollowed-out mass, which—collapsing in on itself—might become a massive tomb.

The motif of the hollow house, a negative form carved in earth, recurs throughout Ullman’s work. It returns in

Sand Table, presented at the 2019 Jerusalem Biennale (see

Figure 2). Having been punctured through with a house-shaped aperture, the base of the iron table frame lets sand drift out, leaving a sloped crater in the shape of Ullman’s generic form, the ghostly home. As in the larger earth sculptures,

Day and

Midnight, the work relies on a delicate equilibrium ensured by slanting the sand at a liminal angle. Downscaling the pit to gallery size, Ullman’s 2019

Sand Table destabilizes the home’s foundations.

Ullman’s experimentation with perforated sand tables commenced in the wake of a visit to the Auschwitz death camp, where the artist’s attention was drawn to an exhibit in which a glass-covered table had been set for a meal whose participants were never to arrive (

Zalmona 2011). Ullman’s iron tables, filled with thinly sifted red earth, ostensibly offer support and containment—firm ground. Through their perforated bottoms, however, the tables betray this promise. The installation

Map (2002;

Figure 9) features a chair and table that have left visible traces of being dragged along the ground in a short-lived act of mapping. As in the case of Sharabani’s

Sand Box (

Figure 3 and

Figure 5), Ullman’s sand boxes preserve only the faintest traces of those presences to have left their imprint upon them. Evincing a deep-seated sense of insecurity, Ullman’s fragile homes and grounds might dematerialize upon the slightest contact with air or bodies. In making an aesthetic leap from earth sculptures to virtual reality, Sharabani broaches similar concerns.

This may be the point to bring in Bennett’s proposition with regard to the “transactive” character of trauma-related art. Assuming a phenomenological rather than hermeneutic viewpoint, I propose that the grainy materiality of sand endows these works with a distinctly sensual appeal which relies on their tactile or haptic suggestiveness. While these works address the unreliability of ground and signal displacement in myriad ways, still, a specifically phenomenological inquiry is prone to disclose a compensatory presence effect, approachable in the terms proposed by Hans U.

Gumbrecht (

2004). On Gumbrecht’s account, this means that the installations under scrutiny tap into “a layer in our existence that simply wants the things of the world close to our skin” (ibid., p. 106), thus reaffirming our presence or emplacement in a material body, if only fleetingly.

5 Significantly in this respect, visitors to Sharabani’s installations are hard put to distinguish between the virtual objects projected onto the sand and the concrete materiality of the medium itself. The surfaces and mounds of sand in both Ullman’s and Sharabani’s work induce a strong desire to sink one’s fingers in them or scoop up a handful. In fact, visitors to Sharabani’s exhibits have been caught attempting to manually capture the virtual objects, complete with the supporting sand (

Figure 10). This would suggest that the interfacing of sand and digital media fosters somatosensory arousal and cognitive dissonance. An augmented sense of bodily presence therefore seems crucial to the experience afforded by the installation. Ullman’s installations, too, incite viewers to tactile engagement with massive bodies of rust and sand, with the haptically suggestive sand tables and the deep pits in the ground, which I shall discuss presently. In addition, I propose that Ullman’s carefully balanced mounds of earth induce a similar bodily tension as that displayed by the human figures in Sharabani’s

Sandbox.

Bennett stresses that “it is the sensation arising in space that is the operative element: its capacity to sustain sensation […] rather than to communicate meaning” (

Bennett 2005, p. 18). This assertion dovetails with my argument that the sand installations under analysis here affectively transact, in Bennett’s terms, through bodily tensions and sensations of instability, while at the same time countering the experience of shifting ground with a heightened sense of bodily presence.

3. Fragile Traces: Ephemeral Architectures and Views from Google Earth

Ullman’s career as a sculptor debuted in the 1970s, during which he produced an Israeli variant on American Earth Art, which he has often referenced as an art-historical context for his early projects (

Zalmona 2011, pp. 361–71). In one site-specific work, performed in 1972 as part of the collective

Metzer-Meisser art project, Ullman exchanged earth between two identical cubical pits dug in the grounds of Kibbutz Metzer and its neighboring Arab village, Meisser (

Zalmona 2011, p. 371). The exchanged bodies of earth were layered with connotations of historical yearning, and, to no lesser extent, by the actuality of unresolved conflict over the land. The work invoked the Hebrew term

Adama (Earth), which, in enfolding

Adam (Man) and

Dam (Blood), evokes both the painful conflict and the possibility that the contested territory might be shared.

This land-exchange project has a biographical dimension, relating closely to both the migratory history of the artist’s family and to his entire generation’s commitment to putting down new roots in the land from which their ancestors had been uprooted. The eleven-year-old Micha was entrusted by his father with the task of digging seven cubic pits in the field adjacent to the family home, which the father would then fill with fertile

Hamra earth brought from another region of Israel, providing good conditions for growing fruit bearing trees (

Zalmona 2011, p. 365). Ullman’s engagement with earth as an aesthetic medium appears to have been nourished by this early memory, compellingly embodying the Zionist ethos of re-fertilizing the historically longed-for land. The exchange of earth between an Israeli Kibbutz and a neighboring Arab-Israeli village, bearing the mutually resonant names of Metzer/Meisser, addresses the politics of the conflict.

In yet another earth project, mentioned in my opening remarks, Ullman shipped red Hamra from his home in Israel to the church of St. Matthew in Berlin’s Kunstforum, where he installed Steps (2012). The installation consists of seven iron stairs functioning as containers for the earth, which descend into a shaft filled with still more red Hamra. The choice of site for this installation evokes the murdered resistance fighter, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was ordained as a priest in St. Matthew’s in 1931. The pit’s depth matches the artist’s height, conforming to his practice of working to the scale of his own body. These human dimensions invest the installation with the solemnity of a burial chamber. Like the iron and earth sculptures Day and Midnight, it enfolds positive and negative, home and tomb, ground and underground. In a way, Steps brings to mind Walter de Maria’s Earth Room, which itself originated in Munich, Germany, in 1968 (being installed in New York in 1977). Still, Ullman’s conflicted and traumatic emplacement, involving fragile transportable ground, stands in stark contrast to the obdurate mass of black earth, which fills De Maria’s room with the sensuality of primal nature.

Another conjunction that calls for attention is that between De Maria’s and Ullmann’s earth installations at the Kassel

Documenta exhibitions of 1977 and 1987, respectively. In 1977, De Maria installed his

Vertical Earth Kilometer at Kassel; a decade later, in 1987, Ullman conceived and executed

Grund (

Figure 11), which literally means

reason in German but also resonates with the English term

ground. De Maria’s

Earth Kilometer confidently laid claim not only to the surface of the land but to its deep substrata too. Ullman’s approach to earth could scarcely be more different. Lifting a chunk of earth off the ground, he positioned it such that it extended above a pit surrounded by a grove of trees. There is no escaping the connotation of mass burial in

Grund, which recalls the mass killings of Jews by the

Einzatsgruppen in the forests of occupied Europe (

Westermann 2019). Beyond the memory of trauma, though, the installation centrally evokes a loss of purchase on the ground. Over and above its unmissable reference to the Shoah and the title’s ambiguous reference to reason and reasoning, the installation’s uprooted and floating ground resonates with profound existential incertitude. Ullman’s work in Kassel, which is close to the town from which his family were traumatically displaced, evinces a persistent migratory apprehension.

Some of Ullman’s later installations spatialize existential transience at a scale suited to gallery exhibition. In

Sanday, performed in 1997, the artist moved the contents of his home into an art gallery in Tel Aviv. The Hebrew title,

Yom Hol, plays on the double meaning of “weekday” and “sand day.” Spraying thinly sieved red soil over the objects before removing them carefully, he created an ephemeral sand map of his family home. A similar gesture can be found in the site-specific installation

Wedding (

Figure 12), which featured centrally in the artist’s retrospective exhibition

Sands of Time (2011) at the Israel Museum. A performative “wedding,” the installation entailed the exhibition curators and volunteers acting out a Jewish matrimonial ceremony. The artist sprayed a thin shower of

Hamra soil over the entire scene, participants included. Ullman defined his own part as that of a “photographer,” recording in sand the imprint of a cryptic event that seemed to have been disrupted, perhaps violently. Finally, in the installation

Semidetached (2018;

Figure 13), Ullman returned to the trope of the home, tracing the floor plans of his family residence and the adjacent neighbors’ semi-detached home in thin berms of red

Hamra. Re-scaling the house to fit the gallery space, the artist included the contours of home amenities, such as showers, wash basins, and bathrooms, among which visitors were invited to meander. The extreme fragility of the installation required weekly maintenance, which the artist undertook himself with the help of assistants, restoring ledges damaged by visitors walking inside the transitory home.

Sanday,

Wedding, and

Semidetached are fragile memory maps, investing the very notion of presence with the haunting shadow of impermanence.

Ullman’s sand maps of memory scapes return with a twist in Sharabani’s project,

Virtual Territories (2019–2020), digitally manipulating satellite views derived from Google Earth. One geographical site chosen for experimentation is the Iraqi city of Basrah. Formerly home to the artist’s family, Basrah remains inaccessible to Israeli citizens to this day. Sharabani’s family, along with most of Iraq’s Jewish population, fled Iraq in the wake of anti-Jewish persecution, which peaked in the Farhud pogrom of June 1941 (

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum 2019b). After a decade’s tribulation, practically the entire Jewish population left Iraq as one in 1951, shocked by the sudden collapse of their participation in the country’s economic and cultural life (

Bashkin 2012). Forced to forfeit their citizenship and private property upon leaving, by a specially legislated decree, Jews have been unable to return since, even only to visit (

The Museum of the Jewish People 2019). Unlike Ullman, who has been invited to return to Germany as a distinguished professor of art, and has had the opportunity to perform acts of closure through installations such as

Library,

Grund, and

Steps, Sharabani is denied access to his parents’ “sending country” (

Chimienti et al. 2019;

Bloch and Hirsch 2018). While the artist’s grandfather had long relinquished any desire to reestablish contact with his former hometown of Basrah, the artist found an outlet for his quest in the remote views of Google Earth.

The manipulated satellite images of Basrah presented in

Virtual Territories neither disclose the artist’s family history nor reveal any trace of the millennia of Jewish life that predated the Islamic settlement of the region. These satellite-mediated views neutralize the history of violence and the trauma of displacement, affording what the artist regards as “analytical distance” (communication with the author on 2 December 2019)—which comes at the cost of masking personal and collective memories. This possibly resonates with the gaps and silences which

Bloch (

2018, p. 652) describes as essential to the life experience of second-generation refugees. In choosing to resort to Google Earth’s global views, Sharabani sends us into orbit in an inverse spatial movement to Ullman’s digging and transporting bodies of earth. Yet, Sharabani experiments with the possibility of transforming the lost or inaccessible presences into solid surfaces, invoking the ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian art of bas-relief (communication with the author on 14 October 2019). Presented as if in low relief, the views of Basrah from outer space bring to mind archaeological excavation sites—unearthing the foundations of vanished civilizations.

One work from among

Virtual Territories named

Basrah #4 (

Figure 14), for example, is a digital simulation of a tabletop sandstone relief. In other iterations, such as

Basrah #3 (

Figure 15), Sharabani has added a bronze tint to the satellite image. Invoking Mesopotamian art, the artist forges a connection between twenty-first-century Iraq and the region’s remote past under the Assyrian and Babylonian empires. In turn, this nod to the region’s history invokes the primordial Jewish trauma of displacement and exile under Babylon, in the seventh century BCE. Returning full circle to modern Iraq,

Virtual Territories revisits the home of one among a huge number of diasporic Jewish communities. After millennia in Iraq, this community took up the challenge of relocating to Israel, its historical country of origin, in the space of a few months in 1951. The virtually rendered relief folds the migratory journey undertaken by the artist’s family onto the region’s ancient history. Basrah is approached from a safe distance as an excavation site viewed from space. In a manner, this resonates with Ullman’s tomb-like pits hollowed out in German soil.

Looking beyond the images of Basrah, the

Virtual Territories series addresses Google Earth views of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount. The quintessence of Jewish identity for close to three millennia, this site has been violently contested among the three monotheistic religions. In this work, Sharabani has traced the contours of the satellite image of Temple Mount onto an actual sand table (

Figure 16a), opting, in his words, to “bring the place itself into the studio” (communication with the author on 13 October 2019). Addressing this politically charged geographical site, Sharabani’s Temple Mount series maps the biblical and historical trauma of the Jewish exile from Jerusalem onto contemporary circumstances, namely the ongoing political conflict between Israel and Islamic fundamentalists over the right to worship in this site cherished by the three monotheistic religions. Recalling

Bennett’s (

2005, p. 12) insistence that, in aesthetic experience, trauma has “a presence, a force”, I propose that the sand table itself renders the anxiety of the conflict compellingly present in the artist’s studio.

Sharabani does not opt for resolution, as does Ullman in the 1970s earth-exchange project,

Metzer/Meisser. Rather, his foregrounding of the fragility of the structure traced in sand displays an ingrained apprehension. Yet, his digital manipulation of the photographed table (

Figure 16b) confers a concrete solidity on the sand relief, symbolically fortifying the fragile traces of ancient Jewish presence in Jerusalem. Where Ullman’s sculptures establish a chromatic kinship between red

Hamra and rusty iron, Sharabani transforms sand into concrete. A deeply ingrained yearning for firm ground drives both aesthetic projects.

A full discussion of the

Virtual Territories series requires attending to a third group of manipulated Google Earth images, these centering on Tel Aviv, the artist’s city of residence.

Cistern #1 (2019;

Figure 17a) and

Cistern #2 (2019;

Figure 17b) are both based on digitally manipulated photographs of the sand table in the artist’s studio, superimposed with Google Earth views of major road junctions in Tel Aviv metropolitan area, the most heavily populated region of Israel. Sharabani has transformed the expanse of sand into a post-apocalyptic concrete wasteland, scarred by thin lines marking the roads that, before the unexplained apocalypse, were presumably bustling with life.

Cistern #1, being the negative image of

Cistern #2, features the blank expanses in deep black as looming cavities that threaten to suck in all life. Sharabani regards

Cistern #1 as an X-ray, probing into

Cistern #2 to reveal traces of former life in the form of minuscule residential buildings clustered around the black holes (communication with the author on 2 December 2019).

The works that comprise

Virtual Territories, particularly

Cistern #1 and

Cistern #2, render surface textures affectively communicative or “transactive” (

Bennett 2005). These surfaces are digitally manipulated so as to suggest a variety of resonant materialities and textures, from sandstone, through bronze, to rough concrete. In their different ways, these tense surfaces seem to appeal directly to visitors’ skins, arousing expectations of tactile stimulation. In fact, gallery visitors have felt compelled to touch the digital prints, expecting to feel texture in relief rather than a smooth surface. In Bal’s terms of migratory aesthetics, Sharabani’s images participate in “a new sensate production of surface as skin” (

Bal 2008b, p. 22). In this way, they seem to privilege

Gumbrecht’s (

2004, p. 111) “presence effect” over the obverse “meaning effect”. Needless to stress, this is not to claim a naïve return to a form of signification unmediated by culture. As Gumbrecht himself emphasizes, in “a culture which is predominantly a meaning culture,” presence is “necessarily surrounded by, wrapped into, and even mediated by clouds and cushions of meaning” (

Gumbrecht 2004, p. 106). Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize the strong haptic appeal and suggestive materiality of the prints and installations discussed here, and the degree to which they arouse somatosensory responses. These aesthetic traits, I posit, work to counter the core experience of groundlessness and spatiotemporal disorientation associated with displacement. This is a move of restoration, whereby, to quote artist John

Di Stefano (

2002, p. 39), “mediated forms of absence can become significant forms of presence within the discourses of displacement and diaspora”.

4. Conclusion: Optimist Radicants

A wave of German-Jewish immigration arrived in pre-state Israel (then under British mandate) in the 1930s in the wake of the Nazis’ rise to power. Immigration from Germany encompassed over 300,000 of the 523,000 German Jewish population counted in 1933 (

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum 2019a), over 160,000 of whom emigrated to Israel (

The Jewish Agency for Israel 2014). Compelled by intensifying anti-Semitic harassment to leave the country that they had considered their homeland for centuries, German-Jewish émigrés clung to a culture that they saw as their own in ways that would, in current immigration research, be termed transnational (

Hansen-Glucklich 2017). Micha Ullman’s parents belonged to the German-Jewish strand of the evolving Israeli society.

6 In a meaningful coincidence, Sharabani currently occupies a studio space in Tel Aviv owned by a German-Jewish entrepreneur and former textile manufacturer, who arrived in Israel in the 1930s as part of the aforementioned generation of immigrants. A massive German weaving loom, of cutting-edge technology in its time, still occupies a central space in the studio. This loom inspired Sharabani’s interactive installation

Conductors and Resistors (2018;

Figure 18).

7 The installation draws on the rows of spools still extant in the studio, forging a direct connection between the artist’s prowess in digital media and the textile manufacturing technology that ensured an immigrant’s livelihood back in the 1930s.

First presented at the 2018 SXSW media art festival in Austin, Texas, Conductors and Resistance features a human figure tangled in virtual yarns issuing from serried rows of disproportionately large spools. By waving their phones toward the screen, visitors could create new threads and further entangle the writhing actor. The artist remarked in private conversation (14 October 2019) that the loom in his studio recalls the relentless efforts of German-Jewish immigrants to industrialize Israel, which was at the time a relatively neglected and underdeveloped Middle Eastern district under British Mandate. At the same time, the now-disabled machine calls attention to the decline of Israel’s textile industry under conditions of accelerated globalization. By now, the major part of Israeli textile manufacture has migrated in pursuit of cheaper labor in Jordan or China, leaving unemployment and social unrest in its wake. The massive loom, Sharabani says, is both a monument to the Israeli textile industry’s heroic past and a signal of its implication in the global migratory cycle (communication with the author on 14 October 2019). In this conjunction, I espy a radicant optimism. Notwithstanding the complexity of historical and political entanglements, a thread of determination and hope runs between the creativity and resilience with which a refugee from Nazi Germany participated in establishing new industries in an old-new homeland during the 1930s, and the younger native Israeli artist who, half a century later, is committed to artistic production of international caliber from his Tel Aviv studio. The trans-generational and, in fact, transnational life of the German weaving loom reflects on Ullman and Sharabani’s meaningful encounter. Bridging the generational gap, they seem committed to defying the unsettling aspects of the radicant condition with a strong restorative pull. This is especially manifest in the divergent yet kindred ways in which they employ sand and earth, maintaining a delicate equilibrium between groundlessness and presence. Balanced between the insecurities of shifting ground, the transience of radicant enrootings, and the anxiety of displacement, Ullman’s and Sharabani’s art relentlessly asserts and reasserts solid borders and grounds. Under ever-challenging existential conditions, they weigh positive mass against negative void, and shifting against solid ground.