Remediating ‘Prufrock’

Abstract

:1. Introduction

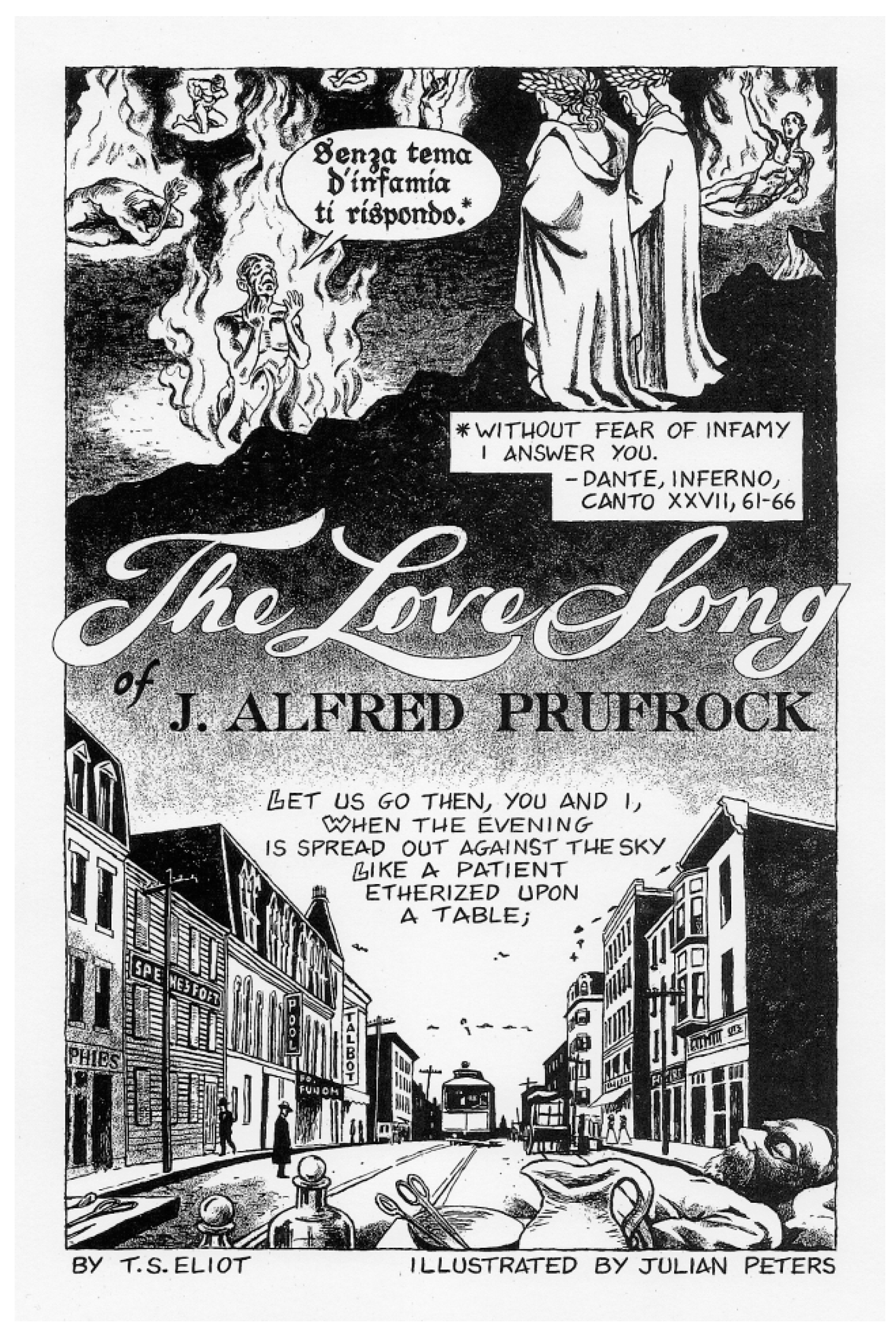

- Comic strip (Julian Peters)

- Animated short film (Christopher Scott)

- Dramatic monologue short film (Karl Verkade)

- Split-screen video poem (Jelena Sinik)

- Photographic spatial montage (Mat Collishaw)

2. Comic Strip (Julian Peters)

So, even though the final panel gives closure to an imagined narrative sequence of panels, Peters draws on various visual media to both ‘unpack’ and compress visual-poetic meaning. And Peters’s reading of the last line is similar to Mat Collishaw’s: “One of my readings is that he is awoken from his reveries by the real world, and that awakening from these interior ruminations, plunges him back into the world he is not equipped to dealing with” (Collishaw 2019, interview). Peters deploys a variety of cinematic shots, including the surrealistic rotated shot, to symbolize the going into the underworld that accompanies the re-entry into an artificial one. By giving visual form to Prufrock’s psychodrama, Peters’ comic strip suggests continuity between the modes of paralysis, the mermaid fantasy and unfulfilled male desire.I liked the idea of showing Prufrock stepping through the entrance of the house from an exterior side angle in which only one of his legs is still visible, in such a way as to suggest that he is being swallowed up by the terrifying social event within. However, the relative visual banality of this image seemed not quite appropriate as a fitting conclusion to the comic. In the end, I must say I’m quite happy with the solution I came up with, which was to rotate this last panel onto its side, in a way that Prufrock appears to be falling into the open door of the house, and this refers back to the descent into the underworld alluded to in the poem’s epigraph from Dante. The position of the leg here, by the way, is inspired by the protruding leg of Icarus in Brueghel the Elder’s painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. A reader pointed out in a comment on my website that the vaguely floral design on the wrought iron railing, when set on its side, recalls the shapes of fish.(Peters 2020b, interview)

3. Animated Film (Christopher Scott)

4. Dramatic Monologue Film (Karl Verkade)

In this YouTube video, there are very few shots of the outside world but plenty of similarly framed close-ups of a prostate and anguished self. Verkade is rarely seen fully in a surrounding environment, except for brief black and white flash shots of Verkade at a windowed door. Flashes of a ceiling fan, coupled with a heavy whispering voice, an eerie soundtrack and lyrical pauses, create a general mood of paralysis, claustrophobia and solipsism. When speaking the words “No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was not meant to be”, a close-up of Verkade’s face (looking troubled or depressed) fades into a shot of sea waves crashing onto rocks (Eliot [1920] 2017, p. 41). The film cuts back to Verdake staring into an empty space, and shortly after when uttering the final lines (“Till human voices wake us, and we drown”), a black blank space frames a close-up of Verdake’s mouth opening to imply horror (Eliot [1920) 2017, p. 42). The video’s closure, with the use of rapid edited metonymic shots, appears post-impressionistic and this amplifies the anti-epiphanic mode, one that resonates with modernist literature of James Joyce’s Dubliners (1914) and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899). So rather than the narrative of mental-scape journeying, Verkade transforms the mock-heroic poem into an intense and over-dramatic study of the inner self (see Figure 3). In other words, this is a prime example of fandom remediation that involves creative new media interaction. Verkade regards the poems as a conduit for channeling an inner life, one that in public life is frustrated. Even though the video eschews Eliot’s doctrine of impersonality (in that poet is not identified with the speaker), the poem has enabled a sense of the self, one that is ‘deep and dark’ and fragile and normally private.This poem means the world to me; I am not sure that I have ever resonated with a piece of art like I have with this piece. And the older I get, the more poignant it becomes. [….] It is not the only interpretation [….] But it is exactly what is inside myself [….] For those of you who know me, this may be deeper than you are used to. I believe the deep and dark serve to bring the light into focus.

5. Split Screen Video Poem (Jelena Sinik)

‘Imagining Time’ combines “magical realism and surrealism with themes of isolation, introversion and passivity from the poem” (Sinik 2018, website). Sinik also comments on the cumulative effect/s through repeated visual motifs. In this respect, the struggle to complete meaning mirrors Eliot’s fractured use of the dramatic monologue as a means of conveying Prufrock’s self-conscious inability to act.The split screen allows the viewer freedom to observe that which attracts their attention more immediately across the competing screen. A shot in the frame on the left or the right side has its own self-contained and separate meaning, but this at the same time is inflected by its relationship to the shot adjacent (on the left/right).(Sinik 2020, interview)

6. Photographic Spatial Montage (Mat Collishaw)

Collishaw’s fusion of photography and cinematic montage situates the ‘Prufrock’ in its technological context, the era of photographic reproduction, and that also captures the tension between the frozen image and the moving image. Collishaw’s montage film is one of developing photographs that correspond to images that “pop up in the poem and then disappear to be replaced by the next image” (McCullin 2015). Collishaw’s digital film shows in motion 9 (3 × 3 on screen) sequences of images. At any one time, nine sequences can be visible, so there is a constant crossover between developing photographic images (see Figure 5). The images were taken from paintings, films and photographs. Collishaw likens this to “a collage happening over time” or a “hall of mirrors with multiple reproduction”, with each image potentially “complementing or contaminating each other” (Collishaw 2019, interview). In other words, Collishaw eschews the discourse of linear fidelity:Generally, I would have said no as I think it’s a preposterous idea to imagine you can add visuals to a poem which is a medium that already generate images in your head. However, as one of the currents in Prufrock is the constant stream of images he conjures up, and the way they dissipate mirroring his own lack of belief he has in himself. I felt it was an interesting challenge to take on.(Collishaw 2019, interview)

Collishaw is also drawn towards the twilight aesthetics of the poem that is conveyed through the spatial divisions of Prufrock’s mental landscape. He likens Prufrock’s descent into the underworld to the darkroom:I didn’t just want to have an image of what was being said, e.g., “trousers rolled” and a picture of rolled up trouser legs. I felt the poem required something less literal, although I do respond to images from the poem in the composition I made. Essentially, I set the film in a photographic darkroom, a subterranean light proof vault, designed for making images come into being. The visuals were always in a state of becoming—they never endure—but are constantly cast aside ready for the next image. A relentless flow of reproductions that don’t have the facility to exist in the real world—in the light. They were interior images from the mind of the poet, daydreams and thoughts without substance.(Collishaw 2019, interview)

Collishaw also chose to use Eliot’s unabridged reading of the poem because the “old recording […] had a slightly distorted, creaky quality, which added a patina to the perception of it. It feels like you are listening to the voice of a ghost” (Collishaw 2019, interview). In remediation terms, the narrating voice of the poet is the trace of old printed media. However, the audio-visual dynamic is not entirely synchronized. We see glimpses of images that correspond to metonymic objects in Eliot’s linear reading (e.g., a coffee spoon), yet some images remain for a longer period. The ‘slippage’ was not intentional and was the result of combining old and new media technologies:The darkroom provides this other space where images form but are not necessarily real or fixed, for they exist in the slippery netherworld. I also included the sound of the clock ticking and the water dripping, both elements of the photographic darkroom, as well as implying a subterrestrial place where time is present but suspended.(Collishaw 2019, interview)

Collishaw’s visualization also deliberately eschews the story of incomplete romance, because for him the “words don’t accumulate to becoming a narrative” (Collishaw). Most video poems clearly read the repeated phrase “Let us go then” as a theatrical invite to a spatial journey through a specific setting that leads to a female indoor space (Eliot [1920) 2017, p. 37). As Cleanth Brooks states: “Prufrock makes his entrance by inviting the reader, whom he seems to accept as inhabiting his own social world, to take a walk with him, a stroll that will take them to an afternoon tea (Brooks [1988] 2000, pp. 79–80). Collishaw’s response echoes Brooks’ account, but he rejects the idea of a goal-oriented narrative and embraces instead an idea similar to Sinik’s view of ‘drifting’:To film all 9 sequences in one take I had to calculate the timing of the poem with the images I was using, and the time the developing fluid would act on the exposed paper. There was evidently going to be a little bit of slippage with timings, something that I was happy to let unfold within the framework I had created.(Collishaw 2019, interview)

Collishaw’s montage art underscores Anne Friedberg’s view that the experiments by filmmakers and Cubist painters who broke free from the single-screen/image paradigm and fractured the single viewpoint is continued in the prevailing multiple-screen composition of digital technologies (Friedberg [2006] 2009, p. 192). Collishaw too expects the viewer to be a ‘montagist’, placing hypermedial demands on the viewer that exceed Mike Figgis’ Timecode (2000). With the use of four digital synchronized digital cameras, Figgis was able to shoot the action in real time (no cuts). The four simultaneous plotlines appear on the screen as four quadrants. As Marilyn Fabe argues:I get the impression from reading Prufrock that he is taking you through these dark deserted streets, but there is nothing particularly engaging to see, just a series of meandering passages with dead ends. Nothing leads anywhere, the words don’t accumulate to becoming a narrative.(Collishaw 2019, interview)

In other words, spatial, as opposed to linear, montage means: “we get to ‘edit’ what we see ourselves” (Fabe 2014, pp. 5–7). Identifying inter-media correlations ‘spread across’ Collishaw’s sequence of resolving and dissolving images requires also a hypertextual mind. By refashioning two visual technologies (the static image of photorealism and the moving image of the camera), Collishaw reminds us that modernist aesthetics was not about satisfying “our culture’s desire for immediacy” (Bolter and Grusin 2000, p. 26). Collishaw’s moving montage imitates the polyfocal effects of new digital hypermediality, and in doing so remediates the fractured, polyvocal aesthetic of ‘Prufrock’, the indeterminacy of an imagistic form as well as the non-linear, interaction of close reading. And, in embodying the aesthetics of modernist experimentation, Collishaw shows that the Rhizomatic pulse of online remediation is not teleological. In the words of Eduardo Kac: “There’s a general misperception when we talk about online culture. Everyone is so obsessed with the internet, but to me, it’s a historical phenomenon. It will be superseded by other networks in the future” (Chatel 2019). The ‘other networks’ or inter-media forms could be propelled by a continuous refashioning of modernist poetics.Timecode […] involves more active participation and attention, and calls for tolerance from the spectator, than is demanded in conventionally constructed films. [….] The use of crosscutting in the conventional [single screen] film narrative affords us omniscience [….] In conventional crosscutting the action unfolds linearly, one image at a time.

7. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aiken, Conrad, and Divers Realists. 1997. T.S. Eliot: The Critical Heritage. Edited by Grant Hugh. New York: Routledge, vol. I, pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-0-4415-56896-8. First published 1917. [Google Scholar]

- Bolter, Jay David. 1991. Writing Space: The Computer, Hypertext, and the History of Print. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, ISBN 0-8058-0428-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bolter, J. David, and Richard Grusin. 2000. Remediation: Understanding New Media. London: The MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-52279-9. [Google Scholar]

- Boog, Jason. 2017. Is Poetry the New Adult Coloring Book? Publishers Weekly. August 5. Available online: https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/74638-is-poetry-the-new-adult-coloring-book.html (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Booth, Paul. 2008. Reading Fandom: MySpace Character Personas and Narrative Identification. Critical Studies in Media Communication 25: 514–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Cleanth. 2000. Teaching ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’. In Approaches to Teaching Eliot’s Poetry and Plays. Edited by Jewel Spears Brooker. New York: The Modern Language Association of America, pp. 78–87. ISBN 0-87352-514-0. First published 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Byron, Glennis. 2003. Dramatic Monologue. London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-22937-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chatel, Marie. 2019. Net Art, Post-internet Art, New Aesthetics, The Fundamentals of Art on the Internet. Digital Art Weekly. January 31. Available online: https://medium.com/digital-art-weekly/net-art-post-internet-art-new-aesthetics-the-fundamentals-of-art-on-the-internet-55dcbd9d6a5 (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Collishaw, Mat. 2015. ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’. BBC Arts. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p02sryh5 (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Collishaw, Mat. 2019. Interview by Scott Freer. Email interview with the author, 20 June 2019. The Journal of the T.S. Eliot Society 2019: 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dickey, Frances. 2014. Prufrock and Other Observations: A Walking Tour. In A Companion to T.S. Eliot. Edited by David E. Chinitz. Oxford: Wiley & Blackwell, pp. 120–32. ISBN 978-1-118-64709-7. [Google Scholar]

- Duffett, Mark. 2013. Understanding Fandom: An Introduction to the Study of Media Fan Culture. London: Bloomsbury, ISBN 978-1-4411-6693-7. [Google Scholar]

- Eliot, Thomas Stearns. 2017. The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. In Poems. Delhi: Facsimile Publisher. First published 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Fabe, Marilyn. 2014. Digital Video and New Forms of Narrative: Mike Figgis’ Timecode and James Cameron’s Avatar. In Closely Watched Films: An Introduction to the Art of Narrative Film Technique. Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0520959019. [Google Scholar]

- Freer, Scott. 2007. The Mythical Method: Eliot’s The Waste Land & A Canterbury Tale (1944). Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 27: 357–70. [Google Scholar]

- Freer, Scott. 2019. Screening Prufrock: What the Mermaids Sing. Adaptation 12: 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedberg, Anne. 2009. The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft. London: The MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-51250-3. First published 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hedley, Gill. 2010. Mat Collishaw, Tracey Emin, Paula Rego: At the Foundling. Songs of Innocence, Experience, Ambivalence. Childhood in the Past 3: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henshall, Daniel. 2016. Passion Film Series. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PuvE1tfjNiU (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Jeffries, Dru. 2017. Comic Book Film Style: Cinema at 24 Panels per Second. Austin: University of Texas Press, ISBN 978-1-4773-1450-0. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. London: New York University Press, ISBN 0814742815. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henri. 2019. ‘Art Happens not in Isolation, But in Community’: The Collective Literacies of Media Fandom. Cultural Science Journal 11: 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, Zach, and Tommy Spears. 2014. ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EE0gv00qnG4 (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Kenner, Hugh. 1960. The Invisible Poet: T. S. Eliot. London: W. H. Allen. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, Gunther. 2005. Literacy in the New Media Age. London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-25356-X. First published 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lanier, Clinton D., Jr., and Aubrey R. Fowler III. 2012. Digital Fandom: Mediation, Remediation and Demediation. In Routledge Companion to Digital Consumption. Edited by Russell W. Belk and Rosa Llamas. London: Routledge, pp. 284–95. ISBN 0415679923. [Google Scholar]

- Manovich, Lev. 2002. The Language of New Media. London: The MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-63255-1. [Google Scholar]

- McCullin, Don. 2015. Pictures Should Make You Think. Art Quarterly 2015: 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- McHale, Brian. 2010. Narrativity and Segmentivity, or, Poetry in the Gutter. In Intermediality and Storytelling. Edited by Marina Grishakova and Marie-Laure Ryan. Berlin: De Gruyter, Inc., pp. 27–48. ISBN 9783110237733. [Google Scholar]

- Meyrat, Auguste. 2018. A Generation of Prufrocks: A Crisis of Single Men. The American Conservative, July 26. Available online: https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/a-generation-of-prufrocks-a-crisis-of-single-men/ (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Miller, Nicole B. Advanced Cinema Productions Film. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8xpHLaCCjbs (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Open Culture. 2017. Available online: http://www.openculture.com/2017/02/t-s-eliots-classic-poem-the-love-song-of-j-alfred-prufrock-gets-adapted-into-a-hip-modern-film.html (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Parui, Avishek. 2013. ‘The Nerves in Patterns on a Screen’: Hysteria, Hauntology and Cinema in T.S. Eliot’s Early Poetry from ‘Prufrock’ to The Waste Land. Film and Literary Modernism. Edited by Robert P. McParland. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 96–106. ISBN 1-4438-6644-X. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Julian. 2019. Interview by Scott Freer. Email interview with the author, 20 June 2019. The Journal of the T.S. Eliot Society, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Julian. 2018. ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock by T.S. Eliot’. Julian Peters Comics. Available online: https://julianpeterscomics.com/page-1-the-love-song-of-j-alfred-prufrock-by-t-s-eliot/ (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Peters, Julian. 2020a. Poems to See By: A Comic Artist Interprets Great Poetry. New York: Plough Publishing House, ISBN 978-0-874-86318-5. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Julian. 2020b. Interview by Scott Freer. Email interview with the author, 10 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Plath, Sylvia. 2000. ‘A Comparison’. In Strong Words: Modern Poets on Modern Poetry. Edited by W.N. Herbert and Matthew Hollis. Hexham: Bloodaxe Books, pp. 145–47. ISBN 1852245158. First published 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Pound, Ezra. 1997. Drunken Harlots and Mr. Eliot. T. S. Eliot: The Critical Heritage. Edited by Hugh Grant. New York: Routledge, vol. I, pp. 70–73. ISBN 978-0-4415-56896-8. First published 1917. [Google Scholar]

- Rowson, Martin. 2012. The Wasteland. London: Seagull Books, ISBN 978-0-8574-2-041-1. First published 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Samples, Lance. 2012. ‘Prufrock’. The Online Community for Filmmaking. Available online: http://www.dvxuser.com/V6/showthread.php?336556-T-S-Eliot-The-Love-Song-of-J-Alfred-Prufrock-Short-Film (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Scott, Christopher. 2012a. Analyzing and Adapting T.S. Eliot’s ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ for Animated Film. Interdisciplinary Thesis for School of Arts and Sciences, Rutgers University. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/doc/93368902/PrufrockFinishedThesis (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Scott, Christopher. 2012b. The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock: Animated. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xpRSmMnx1MU (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Shmoop University, Inc. 2013. The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock by Shmoop. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d3-hI7vYyGc (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Sinik, Jelena. 2015. Imagining Time. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QPk8tuLprzs (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Sinik, Jelena. Jelena Sinik: Animated Filmaker & Illustrator. Available online: https://jelenasinik.wixsite.com/jelena (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Sinik, Jelena. 2020. Interview by Scott Freer. Email interview with the author, 10 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Spender, Stephen. 1975. Eliot. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, ISBN 0-00-633467-9. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Kevin. 2010. Poetry’s Afterlife: Verse in the Digital Age. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, pp. 87–113. ISBN 1-283-01162-X. [Google Scholar]

- Synder, Margaret Sarah. 2015. The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock as Teenaged Wasteland. Master’s thesis, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Trotter, David. 2006. T.S. Eliot and Cinema. Modernism/Modernity 13: 237–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandermeersche, Geert. 2011. Intermediality as Cultural Literacy and Teaching the Graphic Novel. Comparative Literature and Culture 13: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verkade, Karl. 2013. ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’. A Lapel Surprise Production. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UU8pHyY89Qg (accessed on 13 August 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Freer, S. Remediating ‘Prufrock’. Arts 2020, 9, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9040104

Freer S. Remediating ‘Prufrock’. Arts. 2020; 9(4):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9040104

Chicago/Turabian StyleFreer, Scott. 2020. "Remediating ‘Prufrock’" Arts 9, no. 4: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9040104

APA StyleFreer, S. (2020). Remediating ‘Prufrock’. Arts, 9(4), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9040104