Abstract

The production of millions of artificially mummified animals by the ancient Egyptians is an extraordinary expression of religious piety. Millions of creatures of numerous species were preserved, wrapped in linen and deposited as votive offerings; a means by which the Egyptians communicated with their gods. The treatment of animals in this manner resulted in a wealth of material culture; the excavation and distribution of which formed a widely dispersed collection of artefacts in museum and private collections around the world. Due to ad hoc collection methods and the poorly recorded distribution of animal mummies, many artefacts have unknown or uncertain provenance. Researchers at the University of Manchester identified a group of eight mummies positively attributed to the 1913–1914 excavation season at Abydos, now held in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts. This paper presents the investigation of this discreet group of provenanced mummies through stylistic evaluation of the exterior, and the assessment of the contents and construction techniques employed using clinical radiography. Dating of one mummy places the artefact—and likely that of the whole assemblage—within the Late Period (c.664–332BC). Considering these data enables the mummies to be interpreted as the Egyptians intended; as votive artefacts produced within the sacred landscape at Abydos.

1. Introduction

Ancient Egyptian material culture provides evidence to support the importance of animals within religion and everyday life, and as a visual reminder of the richness and diversity of animal life with which the Egyptians shared their land. The majority of ancient Egyptians lived a basic existence working the land, witnessing on a daily basis nature’s cyclical patterns and the characteristics of the animals around them. In a largely illiterate society, symbols of recognisable objects formed a vital means of communication, with a vast array of animals represented in the ancient language of hieroglyphs (Shaw 2004; Strouhal 1992).

The ancient Egyptians believed in a pantheon of deities, all of whom were synonymously associated with one or more animal counterparts, depending on the characteristics of the living creature and their resemblance to the perceived character traits of the god. The Sacred Ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus) and Glossy Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus), common residents in Egypt during ancient times, were believed to be avatars of Thoth, the god of wisdom and writing. The slender curved beak of the ibis likely reminded the Egyptians of a scribe’s writing implements, thereby associating it with scholarly activity (Figure 1). At centres devoted to the sacred ibis, temple officials and visiting devotees participated in cultic activities for the gratification of Thoth. The mummification of enormous numbers of ibis birds as votive offerings at sites across the country provides striking evidence for the popularity of the cult across Egypt over many millennia.

Figure 1.

Illustration depicting the Black (Glossy) Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus) and the Sacred Ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus) from the Description de l’Égypte Histoire naturelle, v.1, published in 1809.

As a royal cemetery and the cult centre for the god Osiris, the site of Abydos, situated on the west bank of the Nile in Middle Egypt, is of extraordinary archaeological and historical interest. Following archaeological excavations by Auguste Mariette (1821–1881) in the late 1850s (Mariette 1869–1880), the Egypt Exploration Fund committed to supporting a programme of excavation at the site beginning in 1899 and continuing until the outbreak of World War I (Petrie and Ayrton 2013). This paper charts the post-excavation history and scientific study of a discrete group of artefacts uncovered during the 1913–14 season (directed by Naville and Peet; republished Naville et al. 2014), enabling them to be considered within the context of the sacred landscape of Abydos.

The discovery of mummified animal remains was generally met with limited enthusiasm by excavators, largely because the material was not considered to be of sufficient archaeological or monetary value. The unwrapping of well-preserved mummies on site was commonplace and led to the destruction of many specimens. Remaining examples were distributed to museums around the world, either as artefacts in their own right or as a plentiful source of packing material to ensure the security of fragile finds during transit. Animal mummies were extremely popular with travellers and private collectors who acquired them as portable, quirky curiosities to remind them of their adventures in foreign lands (McKnight et al. 2015). The ad hoc methods of distribution, collecting and recording created the widely dispersed group of artefacts in museums and private collections today.

Academic interest in animal mummies as material culture and a manifestation of religious activity has increased in recent decades. Many projects have focussed on specific animal species or individual museum collections (Bleiberg et al. 2013; Ikram 2005; McKnight 2010); however, at the University of Manchester, researchers have adopted a more comprehensive approach, resulting in the compilation of a database containing in excess of 1200 individual animal mummies held in 70 museum collections worldwide (Atherton-Woolham et al. 2019). Known as the Ancient Egyptian Animal Bio Bank, the project unites this disparate resource virtually in a central database, thereby enabling efficient research to be conducted on a large, multi-collection dataset.

It is not uncommon for museums to have little or no knowledge relating to the provenance or post-excavation history of mummified animal material in their care; an issue which only serves to compound research difficulties. With little or no recorded provenance, assessing the artefacts in the wider context of their role as material manifestations of religious piety is virtually impossible. Unfortunately, a provenance is recorded for less than 30% of the mummies in the Bio Bank (McKnight et al. 2015; McKnight et al. 2018); however, amassing such a large dataset has the advantage of enabling comparison across collections and allows provenance to be suggested where trends are evident.

The Bio Bank holds records for 35 ibis mummies known to originate from Abydos, with a further four ibis mummies believed to come from the site. The database has records for two ceramic pots containing mummy debris, one ibis egg, a mummified scarab beetle, two mummy bundles containing shrews, a mummified cat and a bovine skull, all originating from Abydos.

The group of mummies discussed here are curated at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts, and over time had become separated from corresponding archives, causing them to be recorded as being of ‘no known provenance’. During a research visit in 2012, all of the specimens were found to display small paper labels bearing the date ‘1914’ followed by an item number (i.e., 1914.332) indicating that they were artefacts recovered by T. Eric Peet (1882–1934) and W. Leonard S. Loat (1871–1932) from Cemetery E, Abydos during the 1913–1914 excavation season (Figure 2). The scientific investigation of a group of mummies with known provenance allows a unique insight into the practice of votive mummification at the site.

Figure 2.

Photograph of ibis mummy MFA acc. no. 6255 with close up showing the original excavation label from the 1914 season. [Photographs taken by author.].

2. Archaeological Excavation

The 1913–1914 excavation season uncovered some 93 ceramic jars, mainly constructed from unfired clay, located amongst human burials (Peet 1914, pp. 37–39) (Figure 3). Assessment of these pots by Loat revealed over 1500 ibis mummies in total ranging from between two and 108 individual bird bundles per pot (Loat 1914, p. 39). Investigations of the mummies conducted on site provides an insight into the nature of the remains, and their reception and treatment at the hands of the excavators. Externally, the mummies are described as being ‘quite a work of art, accomplished by the use of narrow strips of black and brown linen…to form a wonderfully varied series of geometrical and other patterns’ (Peet and Loat 1913, p. 40). Despite the level of decoration (Figure 4), it is clear that many specimens were completely unwrapped on site enabling a direct assessment of the contents as was common practice at the time. It was noted in the report that ‘the same style and design was indiscriminately used for adult birds, young, feathers or bones’ (Peet and Loat 1913, p. 43), suggesting that the bundles appeared outwardly similar irrespective of their contents. This phenomenon is common across the entire Bio Bank dataset with radiographic investigation revealing many of the most elaborately decorated mummies to be completely devoid of animal skeletal material, or to contain incomplete animal remains; referred to as pseudo mummies (McKnight et al. 2015). Statistical analysis suggests a ratio of 2:1 true to pseudo mummies in the dataset, with half of the true mummies containing a complete animal and the other half containing parts of one or multiple individuals (ibid.).

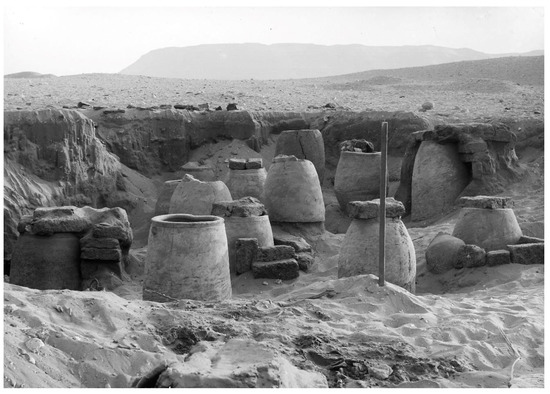

Figure 3.

Excavation photograph showing a number of large ceramic vessels which were found to contain ibis mummies. [Reproduced by kind permission of the Egypt Exploration Society, London.].

Figure 4.

Post-excavation photograph showing four well-preserved and elaborately wrapped ibis mummies from Cemetery E. [Reproduced by kind permission of the Egypt Exploration Society, London.].

Once the external decorative layer and subsequent linen wrappings were removed, the excavators identified two distinct body positions used to create the mummies: ‘either the head and bill were drawn forward and placed along the median ventral line, their contours showing distinctly beneath the bandages, or the head and bill were placed along the left side of the body close to the wing; in both methods the legs are bent forward, having the claws extended and closely pressed against the ventral surface of the body’ (Peet and Loat 1913, p. 40). The former variation (recorded hereafter as Type 1) creates a bundle shape which lends itself to a decorative style consisting of linen strips arranged in a V-shaped formation, whereas with the latter variation (recorded hereafter as Type 2) the conical bundle shape is more commonly decorated with a geometric square design positioned either in a single ventral line or in two or three parallel rows (Figure 5).

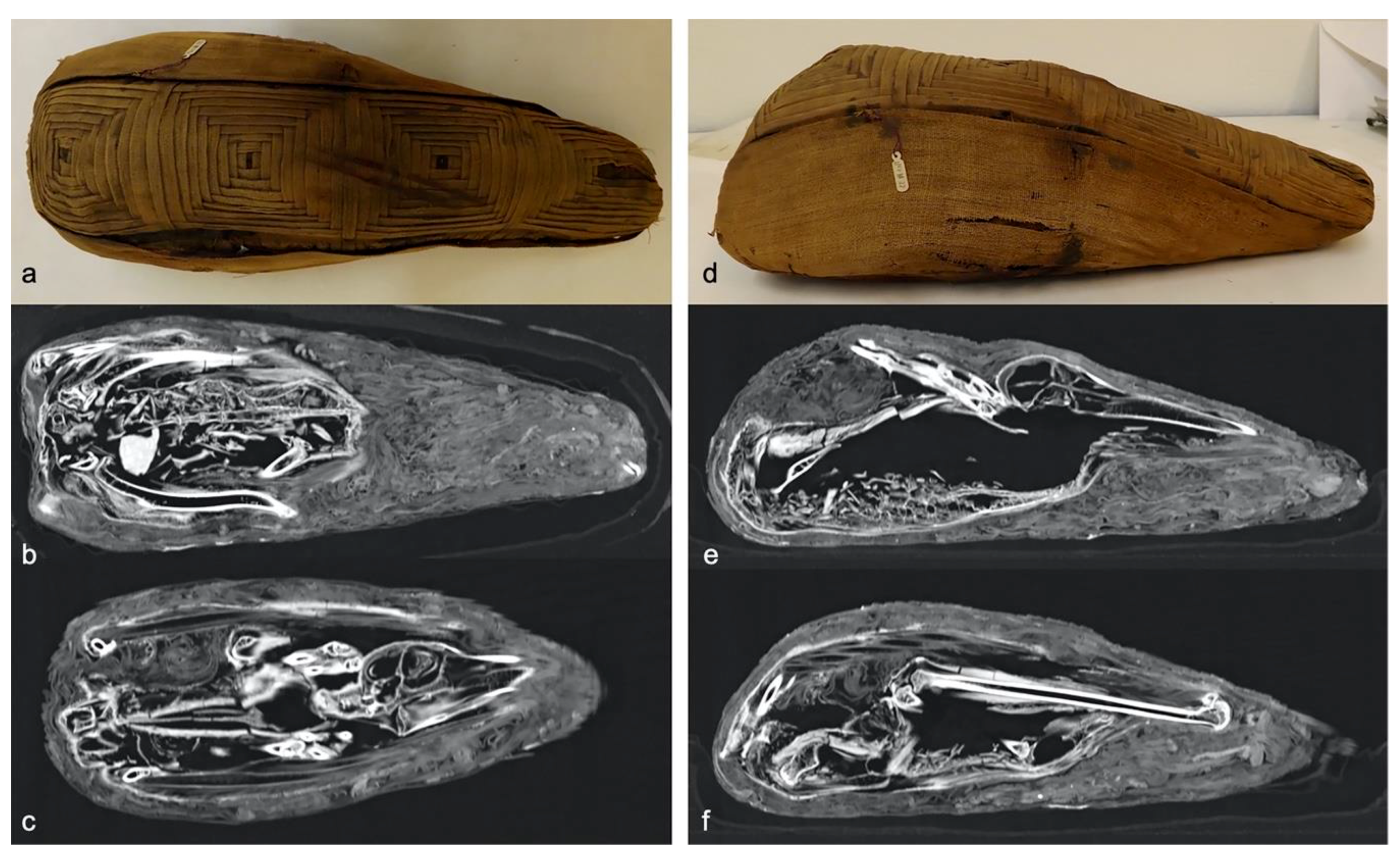

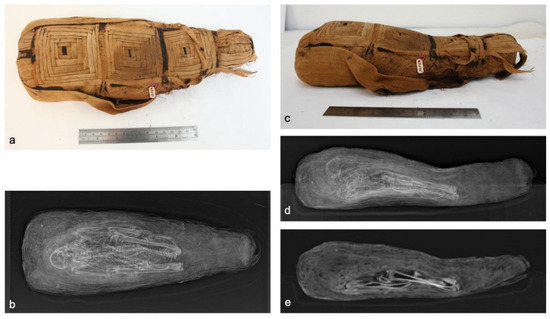

Figure 5.

Figure demonstrating the two distinct bundle forms characteristic of ibis mummies from Abydos. Images (a) photograph, (b) anterior posterior radiograph, and (c) lateral radiograph of a Type 1 mummy (MFA acc. no. 6200.1). Images (d) photograph, (e) anterior posterior radiograph, and (f) lateral radiograph of a Type 2 mummy (MFA acc. no. 6200.2). [Photographs and radiographs created by author for the Ancient Egyptian Animal Bio Bank.].

Many of the mummies had been reduced to dust due to what the excavators believed to be a white ant infestation. Insect damage caused to mummified remains is widely reported and unsurprising (Elamin 2015); however, the identification of the white ant cannot be confirmed at this time. A fine spray varnish was used to consolidate the mummies resulting in ‘most satisfactory results, as the varnish soaked in rapidly and in no way injured the specimens, even from a museum point of view’ (Peet and Loat 1913, p. 41). The consolidation process stabilised the artefacts sufficiently to enable distribution, although such invasive chemical techniques would potentially jeopardise the accuracy of modern scientific investigation. Modern conservation practice favours preventative techniques such as encasing fragile areas in protective net, rather than applying potentially harmful substances which could adversely affect the chemical composition of the materials (Oliva 2016).

The excavation report published by Peet and Loat in 1913 lists 25 museums which benefitted from the receipt of artefacts excavated from Cemetery E, ten of which are located in the United States. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston does not appear on the list. The distribution of the mummified remains was clearly considered of less importance than the associated ceramics which were carefully listed and photographed, with the excavators simply concluding that ‘specimens of mummified ibises were sent to most of the above-mentioned museums’ (Peet and Loat 1913, pp. 49–50). The apparent omission of The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is not unusual; mummies, along with other artefact types, were regularly passed between institutions, auction houses and collectors, and consequently appear without record in many collections. Where accurate archives exist, they often describe the rather circuitous routes which brought artefacts into the collection. For example, a large collection of 4583 Egyptian artefacts, including ten animal mummies, were accessioned in June 1872 after being gifted by Bostonian, Charles Granville Way (1841–1912) on the death of his father, Samuel Alds Way (1816–1872). The artefacts originally formed the private collection of the British traveller, Robert Hay (1799–1863) in Linplum, Scotland, before being sold to Samuel Way through London dealers Rollin and Feuardent. Sadly, records for many artefacts collected by travellers such as those from the Hay Collection are lacking in provenance information.

The outbreak of World War I in July 1914 saw Peet and Loat conscripted to military service which prevented them continuing their archaeological work at Abydos (Tutton 1932). The archaeologist Thomas Whittemore (1871–1950) returned to the site in 1914 in his capacity as American representative of the Egypt Exploration Fund, and continued to record the finds excavated from Cemetery E (Whittemore 1914). A letter written by Whittemore and addressed to J. H. Breasted, Director of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, expresses disappointment that of the 1500 ibis birds found mummified, ‘hardly more than forty were considered in a condition sufficiently sound to warrant their being packed at all, and of these many suffered irreparably in their transportation to London’ (Bailleul-LeSuer 2015, p. 36).

Whittemore attributed the choice of body position as to whether or not rigor mortis had set in, thereby affecting the manipulability of the neck. His report includes observations on the wealth of wrapping styles and how these had been achieved using padding, linen and thread, all held together ‘without stitching and apparently without gum’, presumably indicating that there was little evidence for the use of mummification unguents during the wrapping phase (Whittemore 1914, p. 248).

It is possible that the Boston ibises were discovered during Peet and Loat’s tenure at the site, but distributed some months later by Whittemore. Interestingly, Whittemore originated from Cambridge, Massachusetts, which may account for the current location of the artefacts in the Museum of Fine Arts.

3. Materials and Methods

A research study visit to the Museum of Fine Arts conducted by the author in 2012 enabled a preliminary assessment of the entire animal mummy collection to be undertaken. The specimens were brought from an off-site storage facility to a designated work space in the Museum’s organic storerooms. The mummies were measured; the shape, condition and decorative features recorded; and the museum archives examined for details relating to their provenance and accession. It was during this visit that the eight animal mummies from Abydos were identified by their tiny paper labels. Although a number of mummies in the collection were radiographed during the 1980s, no hard-copy films existed for the eight Abydos mummies suggesting that they were not studied at this time.

Radiography is usually conducted early in the investigation process as it helps to define the nature of the artefacts, highlight any potential conservation concerns and determine the feasibility of further scientific analysis. Radiographic investigation of the Abydos mummies took place during a second study visit in February 2019. The eight mummies were transported the short distance to the nearby Brigham and Women’s Hospital for clinical radiographic imaging, with the session scheduled for the end of the clinical day. Digital radiographs (X-Rays) were obtained in lateral and anterior-posterior projections using a Fluorospot Compact (Siemens, Munich, Germany).1 Computed tomography scans (CT) were obtained for all specimens using a SOMATOM Force (Siemens, Munich, Germany),2 allowing a non-invasive investigation of the bundle contents and the mummification treatment to be conducted.

Recent studies have opted to utilise dual energy CT scanning which uses two X-ray sources (compared with a single source in standard clinical CT) to acquire a higher volume of data at an improved resolution (Bewes et al. 2016; Taylor and Antoine 2014, p. 20). Three of the Abydos specimens (MFA acc. nos. 6200.3, 6255 and RES.14.33) were scanned using the SOMATOM Force’s dual-energy function to enable image quality comparison with standard clinical CT.3

The peak in religious activity at Abydos, as with many other animal cemetery sites, has been attributed to the Roman period (30BC–AD395) based upon the form of the ceramic vessels in which the mummified remains were interred (Loat 1914). Although scientific dating techniques would allow the most accurate opportunity to date this material, their application to mummified animal remains is in its infancy (Richardin et al. 2017, Paul Nicholson pers. comm.), restricted by the high cost of the technique and the ethical implications of acquiring suitable samples from wrapped mummies. The decision to sample mummy (MFA acc. no. 6200.2) was made due to the presence of an area of damage which allowed direct access to the mummified remains, resulting in minimal further damage as a result of the sampling procedure. The sample which weighed 94.2 mg and comprised coated feather and attached soft-tissue, was removed using sterile tweezers and placed into a glass vial before being sent to the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit for dating analysis using accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS).4

4. Results

4.1. Stylistic Investigation

The Abydos ibis mummies demonstrate the exceptional quality of decorative detail achieved by the ancient craftspeople. The outer surface of the bundles display elaborate geometric patterns created through the placement of dyed linen strips. With no documentary evidence located to suggest how and by whom these designs were produced, our understanding is based entirely on evidence provided by the artefacts themselves. In particular, close visual inspection of damaged mummies provides insight into the construction methods employed by allowing a direct view of the individual linen layers (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Photographs showing how areas of damage to mummy bundles can provide information on the construction of the elaborate wrapping styles (a) mummy MFA, Boston, acc. nos. 6200.4, (b) 6255, (c) RES.14.33, and (d) 6200.2. [Photographs taken by author.].

Experimental techniques are useful in demonstrating the complexities of the wrapping process and in providing suggestions for how the designs were achieved. Researchers at Manchester have designed and undertaken a programme of experiments to recreate various wrapping styles, based upon evidence gathered through the investigation of ancient mummies (McKnight 2018). Techniques include the precise folding of individual linen strips to create clean edges which are then positioned to form decorative details such as the herringbone and geometric square designs displayed on the Abydos examples. In this way, the finished design has a ‘crisp’, neat edge and the rough edge is hidden from view beneath subsequent linen strips (Figure 6).

4.2. Clinical Radiography

The Abydos mummies were recorded in museum records as being mummified ibis birds, with the exception of two specimens (MFA acc. nos. 6200.3 and RES.14.33) which were recorded as being dog mummies. It is unclear why this identification had been provided as the mummies in question both display the characteristic ibis mummy shape. It is possible that the classification was a recording error; however, it highlights a cautionary tale in museological misrepresentation; wherever possible, catalogue identifications should be confirmed, rather than simply accepted without question.

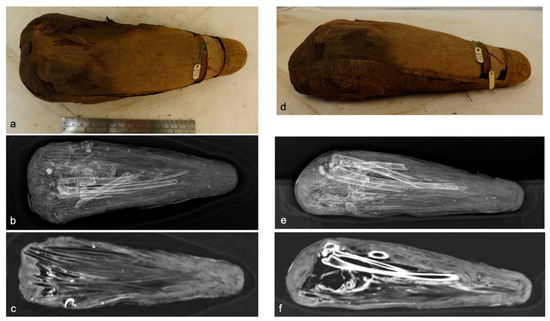

All eight mummies were found to contain animal remains (true mummies) (Table 1). In six cases, the bundles contained the remains of a complete sacred ibis. The seventh (MFA acc. no. 6254) contained incomplete ibis remains, and the eighth (MFA acc. no. RES.14.33) contained a complete ibis with what appears to be an additional section of spine from a second ibis. All the remains belong to adult individuals with the exception of those contained within bundle MFA acc. no. 6200.4 which belong to a juvenile, as demonstrated by the presence of unfused epiphyses on the long bones (Figure 7). In this case, the skeleton is arranged in the Type 1 position; however, the completed bundle more closely resembles the conical shape normally seen in Type 2 examples. This difference is caused by the relatively small size of the remains, meaning that the skull does not create such a protuberance as is seen in the adult examples. In this case, the smaller ibis body has been padded out using linen wrappings to create a deceptively large completed bundle, thereby disguising the juvenile status of the bird within.

Table 1.

Table summarizing the radiographic findings for the eight mummies in the study group.

Figure 7.

Figure demonstrating the bundle elongation of mummy MFA acc. no. 6200.4 and the juvenile bird within. Images (a) anterior posterior photograph, (b) anterior posterior radiograph, (c) lateral photograph (d) lateral radiograph, and (e) sagittal CT reformat showing an unfused epiphysis on the distal tibiotarsus. [Photographs and radiographs created by author for the Ancient Egyptian Animal Bio Bank.].

Identification of the individual specimens to sub-species (Sacred and Glossy Ibis) was not attempted in this study due to the likelihood of inaccuracies when offering identifications based solely upon radiographic data. The inability to physically access skeletal elements to allow for direct identification with comparative material, along with the complicating factors of incomplete and fragmentary remains, the compression of the remains and the presence of linen wrappings and mummification materials, all contribute to this issue. Further research is underway by the author to investigate the extent to which an accurate identification can be made.

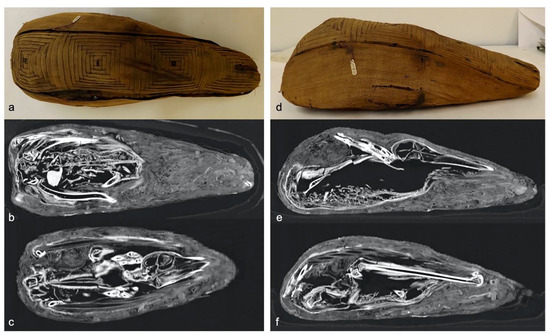

Radiography is useful in highlighting evidence of the internal bundle construction, with different qualities of linen fabric and the use of supplementary materials such as wood and organic matter appearing with a variety of radiographic densities. Often these additional materials appear to have been used to create the shape of the finished bundle or to provide support to fragile or incomplete remains, enabling the finished artefacts to fit standardised forms. The bundle containing the incomplete remains (MFA acc. no. 6254) has the smallest external dimensions, most likely because the fragmented contents lack the structural framework of a complete individual around which the bundle could be formed (Figure 8).

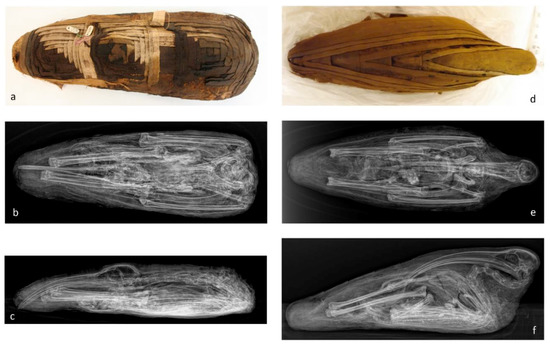

Figure 8.

Figure highlighting the incomplete skeletal remains contained within mummy MFA acc. no. 6254. Images (a) anterior posterior photograph, (b) anterior posterior radiograph, (c) coronal CT reformat showing the arrangement of feather shafts, visible as air-filled linear structures, (d) lateral photograph, (e) lateral radiograph, and (f) sagittal CT reformat showing the incomplete skeletal elements with feathers underneath. [Photographs and radiographs created by author for the Ancient Egyptian Animal Bio Bank.].

The external form of the mummies generally complies with these criteria irrespective of the nature of the contents, suggesting that external appearance was given equal importance in the effectiveness of the artefacts as viable votive objects (McKnight et al. 2018). The Egyptians believed that the gods could be appeased through the offering of gifts in corresponding animal form and that it was necessary for the gods to recognise a gift in order for it to fulfil its votive capability (Price 2015). The significance of animal imagery and the recognisable forms given to these mummies served to reinforce their association with the gods to which they were offered.

Animal mummies, generally smaller in size than human mummies, combined with tight compression and the close proximity of structures, are difficult to visualise accurately, no matter what technique is being used. Manipulation of the radiographic data to improve identification of bundle contents and inform on bundle construction is crucial to improving our understanding of mummification, making CT scanning vital to mummy investigation. The application of dual energy CT scanning to three of the mummies reported here resulted in a large high resolution dataset. As a researcher, it is important to approach each investigation being mindful of achieving data of the highest possible quality; not only because the resulting data will form an important record of the mummies at the time the investigation is conducted, but because opportunities to conduct further examinations in the future can never be taken for granted.

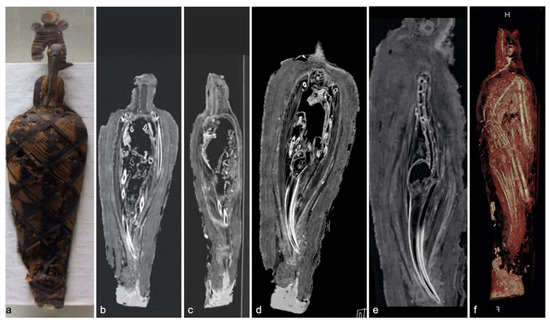

Mummy MFA acc. no. RES.14.33 scanned using the dual energy technique was shown to contain the remains of more than one individual ibis, as evidenced by an additional section of spinal column (Figure 9). The superior quality data revealed a clearer picture of the wrapping of the mummy, in particular the pad of linen placed to support the head.

Figure 9.

Figure showing the contents of mummy MFA acc. no. RES.14.33 as revealed by dual energy CT scanning. Images (a) anterior posterior photograph, (b) coronal CT reformat showing the two femora located at the base of the bundle with some loose skeletal debris, (c) coronal CT reformat showing the skull, (d) lateral photograph, (e) sagittal reformat showing the large air-filled void inside the body, the fragmented elements and loose debris at the base, and the additional section of spine located behind the skull, and (f) sagittal CT reformat showing the radius. [Photographs and radiographs created by author for the Ancient Egyptian Animal Bio Bank.].

At the time of writing this paper, dual energy scanners are not widely available in clinical settings in the UK and certainly not within the NHS. The opportunity to use the technology in this study was made possible as the investigations took place oversees. Dual energy undoubtedly represents an interesting avenue for mummy studies and future research will take advantage of the technique as it becomes more widely available in clinical settings.

4.3. AMS Dating

AMS dating of the sample recovered from ibis mummy MFA acc. no. 6200.2 yielded a date range of 555–527B.C. placing the artefact in the late 26th Dynasty (664–525B.C.), over half a century earlier than was previously believed. The result correlates with the limited published data (Wasef et al. 2015; Richardin et al. 2017) suggesting that the mass mummification of animals as votive offerings was already in decline at the start of the Roman Period (c.30BC). In actuality, the practice appears to have peaked during the Late Period which causes researchers to re-evaluate the previously accepted chronology.

5. Discussion

Animal mummies, produced in enormous numbers during ancient times, present a plentiful, yet challenging archaeological resource. The majority of surviving material remains in situ at animal cemetery sites, many of which are not safely accessible or have suffered extensive environmental damage. Mummies which were distributed through the partage system to museums worldwide, accompanied by those transported around the world in the hands of collectors and travellers, provide a more accessible source of material with which to study the practice.

The diversity of animal mummies in museum collections worldwide provide a unique ‘window’ through which to view ancient civilisation. Intended not to be seen post-deposition, yet depicting strikingly intricate and beautiful decoration, the mummies have much to tell us about life, death and faith in the ancient world. As votive offerings, they physically embody the importance of animals within ancient Egyptian beliefs; as zooarchaeological deposits, they act as microcosms of information about the natural world; and as archaeological artefacts they showcase the dexterity and skilled workmanship of artisan craftspeople. Although a plentiful resource, researchers today are conscious of the numerous biases affecting the material. With the absence of supporting evidence for the practice, the application of modern non-destructive scientific techniques to artefacts in museum collections is our most effective tool in hoping to understand the complex relationship between the ancient Egyptians and the natural world.

The project described in this paper evolved through a simple process of locating the material in museums, conducting basic preliminary assessment and drawing parallels with other collections. In cases where animal mummies appear unprovenanced, it is often beneficial to ask questions about the collection in its broader sense as often other accessioned artefacts provide connections to specific sites or to named individuals (archaeologists, collectors or benefactors). Visiting collections in person to study mummies by eye yields greater success than relying upon museum catalogues and databases which are often incomplete, inaccurate and difficult to navigate. Radiography of mummified material continues to reveal important information not only regarding the contents of wrapped bundles, but in adding to our understanding of the embalming methods used.

Comparisons with mummies accessioned into the Ancient Egyptian Animal Bio Bank reveal a number of mummies attributed to Abydos, including several reported in the collection of The Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago via the collection of James Henry Breasted (1865–1935) (Bailleul-LeSuer 2012; Bailleul-LeSuer and Ressman 2012). The radiographic study of two Abydos ibis (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History acc. nos. ANT.006924.002 [Type 1] and ANT.006924.004 [Type 2]) showed evidence of evisceration and the introduction of extraneous packing materials to the body cavity (Wade et al. 2012). One specimen (Manchester Museum acc. no. 6098) (McKnight 2012) displays a design feature—the attachment of false heads and feet to mummy bundles in anthropomorphic form—noted by Whittemore (1914, p. 248) in his assessment of the Abydos mummies (Figure 10). It is not known as to whether these mummies displaying decorative accoutrements were treated in the same way by the temple officials, or whether they received different treatment to the standard interment in ceramic vessels.

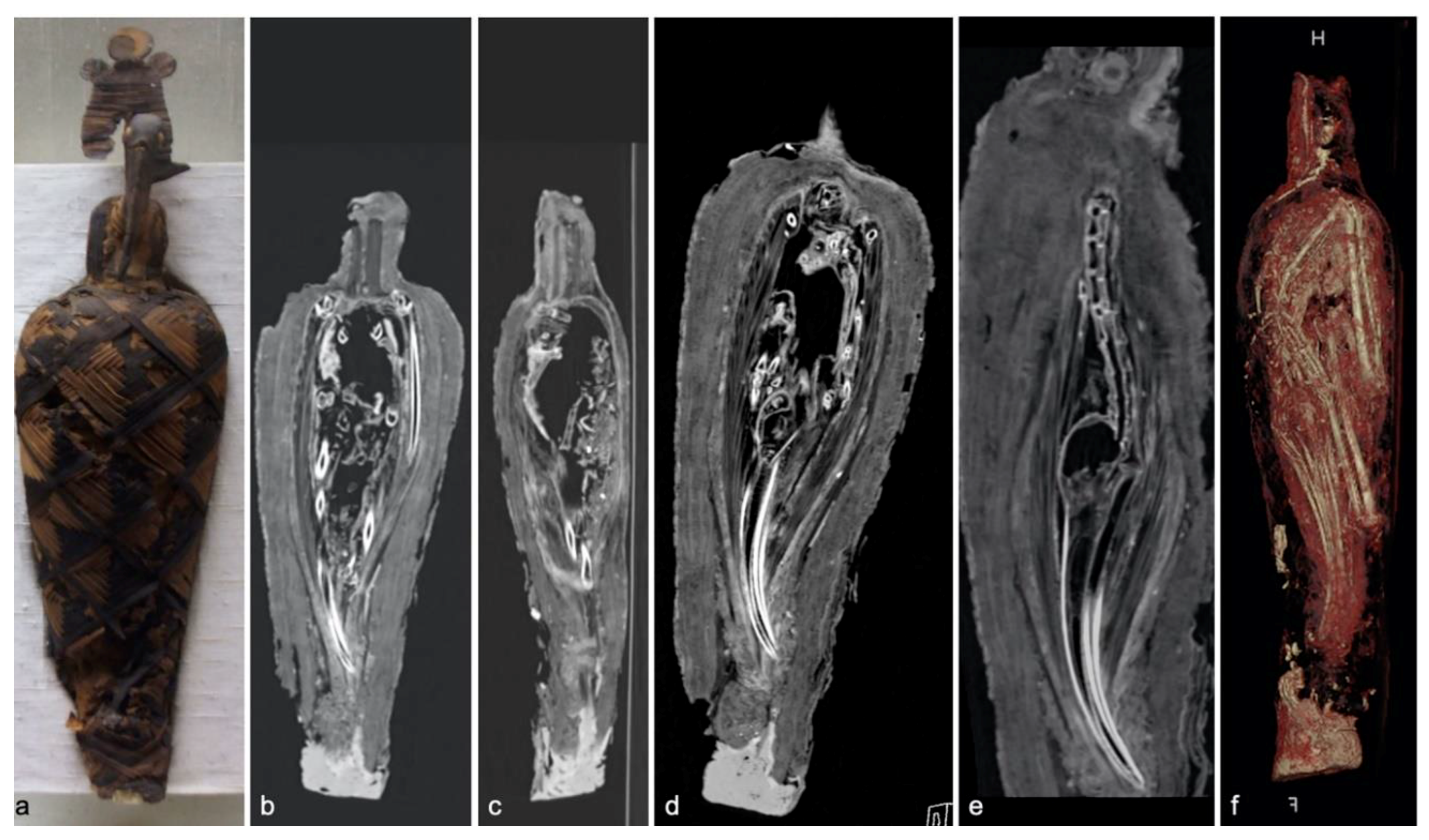

Figure 10.

Figure showing Abydos mummy Manchester Museum acc. no. 6098. Images (a) photograph showing the addition of a removable false head depicting an ibis wearing the Atef crown, (b) coronal CT reformat (c) sagittal CT reformat (d) multiplanar reformat (e) multiplanar curved plane reformat (f) reformat showing the skeletal elements and preserved soft tissues. The radio-opacity at the distal end of the bundle is modern conservation wax added to consolidate the fragile bundle. [Photographs and radiographs created by author for the Ancient Egyptian Animal Bio Bank.].

The application of scientific dating techniques to mummified animal remains has implications for research in the wider field of Egyptology, in particular our understanding of human mummification. It was widely believed until recently that the stylistic decoration given to animal mummies evolved from the techniques used to decorate human mummy bundles. These techniques include the creation of intricate geometric patterns and herringbone designs created using mono- or multicoloured linen strips. Human mummies displaying such elaborate decorative features have been securely dated to the Roman Period (Ikram and Dodson 1998, pp. 187–92), correlating with the suspected date of the ceramic ibis pots. Recent accurate animal mummy dates preceding the Roman Period challenges this widely accepted chronology. It now seems increasingly probable that the decorative styles were used on animal mummies before being used on human mummies. In practical terms this would seem plausible—develop and perfect styles on smaller animal remains before incorporating them into human mummification trends.

The subject of the exploitation of natural resources within the sacred landscape at Abydos remains a vigorously debated topic. The sheer volume of animal burials at animal cemeteries across Egypt raises questions as to how the enormous demand for animal offerings was met. Each species must be considered individually; some will breed freely with little human intervention, whereas others require intense management or are virtually impossible to breed in captivity (e.g., birds of prey). Ibises breed relatively freely and the limited archaeological and documentary evidence suggests that populations were encouraged to reside and flourish in the vicinity of sacred sites (Martin 1974; Ray 1976). Whether these sites were considered sacred as the result of a naturally occurring avian population, or whether the birds were encouraged to breed in a landscape considered to be sacred for other reasons remains unclear.

The only surviving documentary evidence for the management of the ibis is The Archive of Hor, the musings of a high-ranking officiant of the ibis cult at the site of Saqqara (Ray 1976). Hor writes about the tending of a sacred flock of ibis birds residing at the Lake of Abusir, a naturally occurring ephemeral lake in the vicinity. Hor writes about the mummification industry at Saqqara, including the occurrence of so-called ‘abuses’ in which unscrupulous embalmers were punished for lax standards (Martin 1974; Ray 1976). He also provides details about the management of a live flock of ibis at the site, including the supply of fresh food grown on the surrounding land and used to sustain the population. The hieroglyphic inscription written on ostraca was translated by Ray as the provision of ‘clover’ as a foodstuff.

Archaeological evidence for the rearing or breeding of ibis populations at temple sites is largely restricted to Block 3, Sector 7 at Saqqara. Excavations on the site between 1972–1973 directed by Geoffrey Martin uncovered a walled area containing the remains of ibis eggs and nest material, interpreted as an incubation area (Martin 1974). This evidence appears to correlate with the results of a recent mitogenomic study of ancient and modern ibis populations which suggests that the birds were encouraged to breed in small-scale localised habitats, rather than being deliberately farmed in larger centralised locations (Wasef et al. 2019).

Despite its prevalence during ancient times, the Sacred Ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus) and Glossy Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus) are not present in modern day Egypt. Environmental changes in Egypt over the course of the millennia caused a rise in aridity and a corresponding reduction in naturally occurring watering holes; both factors which pushed the ibis to move further south into Ethiopia. The mass mummification of ibis as votive offerings over an extended time period may well have adversely affected viability of sustaining a population.

Animal mummies are a unique group of artefacts; occurring in enormous numbers, yet about which relatively little is known. They provide an insight into animals as a resource, in life, in death, in the Afterlife and as objects of material culture. They act as a snapshot of the natural world at a given point in history; providing evidence for the prevalence of specific breeds and how they were managed and exploited to satisfy the demands of a widespread religious infrastructure, uniting geographic regions in the quest to open channels of communication with the gods. As researchers, we are faced with a unique opportunity to investigate the role that animals mummified as votive offerings played in the wider context of the Egyptian civilisation, yet we must also exercise caution. Votive mummies are the product of industrial scale religious practice. Once deposited, they were never intended to be seen; they were responsible for carrying the prayers, concerns and hopes of the ancient Egyptians to their gods, silently and across space and time. As scientists and Egyptologists thousands of years later, we have a unique and critical role to play, not only in striving to understand the role these animals played, but in accepting that they are the product of a civilisation which continues to hold many more secrets than it holds answers.

The animals interred at Abydos represent a small percentage of the total number of votive animal mummies produced in Egypt. Mummies in museum collections are a vital source of information, yet they are a purposefully chosen selection, deemed significant by archaeologists and collectors due to the quality of their external decoration or the excellent state of preservation. Biased by the conditions of their storage, excavation, transportation and study, the extent to which museum specimens are representative of the entire animal mummy deposits at a site remains highly speculative. By acknowledging this disparity, mummified faunal remains can be used as a means of understanding the unique role played by animals in ancient Egypt.

Funding

The Leverhulme Trust (RPG-2013-143), the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AH/P005047/1) and the Natural Environment Research Council (NF/2016/1/11) provided funding for aspects of this research.

Acknowledgments

Grateful thanks are extended to the Leverhulme Trust (RPG-2013-143), the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AH/P005047/1) and the Natural Environment Research Council (NF/2016/1/11) for funding aspects of this research. To Denise Doxey, Curator of Ancient Egyptian, Nubian and Near Eastern Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston for permission to study the animal mummy collection and for her continued support. To the radiography team at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston for their expertise, support and enthusiasm for these somewhat unusual patients; and the team at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit for their assistance with the AMS dating protocol and interpretation.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bailleul-LeSuer, Rozenn. 2012. Bird Mummies at the Oriental Institute Museum Get a Checkup. The Oriental Institute: News and Notes 214: 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bailleul-LeSuer, Rozenn, and Anna Ressman, eds. 2012. Between Heaven and Earth: Birds in Ancient Egypt. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Bailleul-LeSuer, Rozenn. 2015. The British at Abydos, Egypt: The contributions of T. Eric Peet and W. Leonard S. Loat to the study of animal cemeteries. In Gifts for the Gods: Ancient Egyptian Animal Mummies and the British. Edited by Lidija McKnight and Stephanie Atherton-Woolham. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bewes, James, Antony Morphett, F. Donald Pate, Maciej Henneberg, Andrew Low, Lars Kruse, Barry Craig, Aphrodite Hindson, and Eleanor Adams. 2016. Imaging ancient and mummified specimens: Dual-energy CT with effective atomic number imaging of two ancient Egyptian cat mummies. Journal of Archaeological Science 8: 173–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bleiberg, Edward, Yekaterina Barbash, and Lisa Bruno. 2013. Soulful Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt. New York: Brooklyn Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Fiona, Thomas Higham, Peter Ditchfield, and Christopher Bronk Ramsey. 2010. Current Pretreatment Methods for AMS Radiocarbon Dating at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (Orau). Radiocarbon 52: 103–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, Abdelrahman. 2015. Damage Caused by Insects of Ibis mummies from late period: A case study. International Journal of Conservation Science 6: 145–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram, Salima, and Aidan Dodson. 1998. The Mummy in Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram, Salima, ed. 2005. Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loat, William Leonard Stevenson. 1914. Ibis Cemetery at Abydos. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 1: 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariette, Auguste. 1869–1880. Abydos: Description des Fouilles Exécutées sur L’emplacement de Cette Ville. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Geoffrey Thorndike. 1974. Excavations in the Sacred Animal Necropolis at North Saqqâra, 1972–1973: Preliminary Report. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 60: 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, Lidija. 2010. Imaging Applied to Animal Mummification in Ancient Egypt. BAR International Series (no. 2175). Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, Lidija. 2012. Studying Avian Mummies at the KNH Centre for Biomedical Egyptology: Past, Present and Future. In Between Heaven and Earth—Birds in Ancient Egypt. Edited by R. Bailleul-LeSuer. Chicago: Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, pp. 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, Lidija, Stephanie Atherton-Woolham, and Judith Adams. 2015. Clinical Imaging of Ancient Egyptian Animal Mummies. RadioGraphics 35: 2108–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKnight, Lidija. 2018. ‘Re-rolling’ a Mummy: An Experimental Spectacle at Manchester Museum. EXARC Journal 2018: 1. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, Lidija, Richard Bibb, Roberta Mazza, and Andrew Chamberlain. 2018. Appearance and Reality in Ancient Egyptian Votive Animal Mummies. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 20: 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Atherton-Woolham, Stephanie, Lidija McKnight, Campbell Price, and Judith Adams. 2019. Imaging the Gods: Animal Mummies from the South Ibis Galleries and South Shaft of Tomb 3508, North Saqqara, Egypt. Antiquity 93: 128–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naville, Edouard Henri, Thomas Eric Peet, and William Leonard Stevenson Loat. 2014. The Cemeteries of Abydos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, Cinzia. 2016. The Conservation of Egyptian mummies in Italy. Techne: Science at the Service of the History of Art and the Preservation of Cultural Property 44: 122–26. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/techne/1205?lang=en (accessed on 10 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Peet, Thomas Eric. 1914. The year’s work at Abydos. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 1: 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peet, Thomas Eric, and William Leonard Stevenson Loat. 1913. The Cemeteries of Abydos III. London: Egypt Exploration Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, William Matthew Flinders, and Edward Russell Ayrton. 2013. Abydos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Campbell Roger. 2015. Votive practice in ancient Egypt. In Gifts for the Gods: Ancient Egyptian Animal Mummies and the British. Edited by Lidija McKnight and Stephanie Atherton-Woolham. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, John David. 1976. The Archive of Hor. London: Egypt Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Richardin, Pascale, Stephanie Porcier, Salima Ikram, Gaëtan Louarn, and Didier Berthet. 2017. Cats, crocodiles, cattle, and more: Initial steps toward establishing a chronology of ancient Egyptian animal mummies. Radiocarbon 59: 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, Ian. 2004. Ancient Egypt: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strouhal, Eugen. 1992. Life of the Ancient Egyptians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, John Hilton, and Daniel Antoine. 2014. Ancient Lives, New Discoveries: Eight Mummies, Eight Stories. London: The British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tutton, Alfred E. H. 1932. Mr. Leonard Loat. Scientific Work in Many Lands. The Times Newspaper. April 30. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/archive/article/1932-04-30/14/7.html#start%3D1785-01-01%26end%3D1985-01-01%26terms%3DLoat%26back%3D/tto/archive/find/Loat/w:1785-01-01%7E1985-01-01/1%26next%3D/tto/archive/frame/goto/Loat/w:1785-01-01%7E1985-01-01/2 (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Wade, Andrew, Salima Ikram, Gerald Conlogue, Ronald Beckett, Andrew Nelson, Roger Colten, Barbara Lawson, and Donatella Tampieri. 2012. Foodstuff placement in ibis mummies and the role of viscera in embalming. Journal of Archaeological Science 39: 1642–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasef, Sally, Rachel Wood, Samia El Merghani, Salima Ikram, Caitlin Curtis, Barbara Holland, Eske Willerslev, Craig Millar, and David Lambert. 2015. Radiocarbon dating of Sacred Ibis mummies from ancient Egypt. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 4: 355–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasef, Sally, Sankar Subramanian, Richard O’Rorke, Leon Huynen, Samia El-Marghani, Caitlin Curtis, Alex Popinga, Barbara Holland, Salima Ikram, Craig Millar, and et al. 2019. Mitogenomic diversity in Sacred Ibis Mummies sheds light on early Egyptian practices. PLoS ONE 14: e0223964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittemore, Thomas. 1914. The ibis cemetery at Abydos: 1914. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 1: 248–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Digital radiography specification—50 kV, 5 mAs. |

| 2 | Computed tomography specification—120 kV, 200mAs, pitch of 0.969:1, 0.6 s rotation, 0.6 mm slice thickness. |

| 3 | Dual energy computed tomography specification—(a) 80 kV, 200 mAs (b) 150kV, 100 mAs with pitch of 0.969:1, 0.6 s rotation, 0.6 mm slice thickness. |

| 4 | AMS technique described in Brock et al. (2010). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).