Local vs. International Hamburger Foodservice in the Consumer’s Mind: An Exploratory Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Hamburger Foodservice in Turin Area

3.2. Methodology

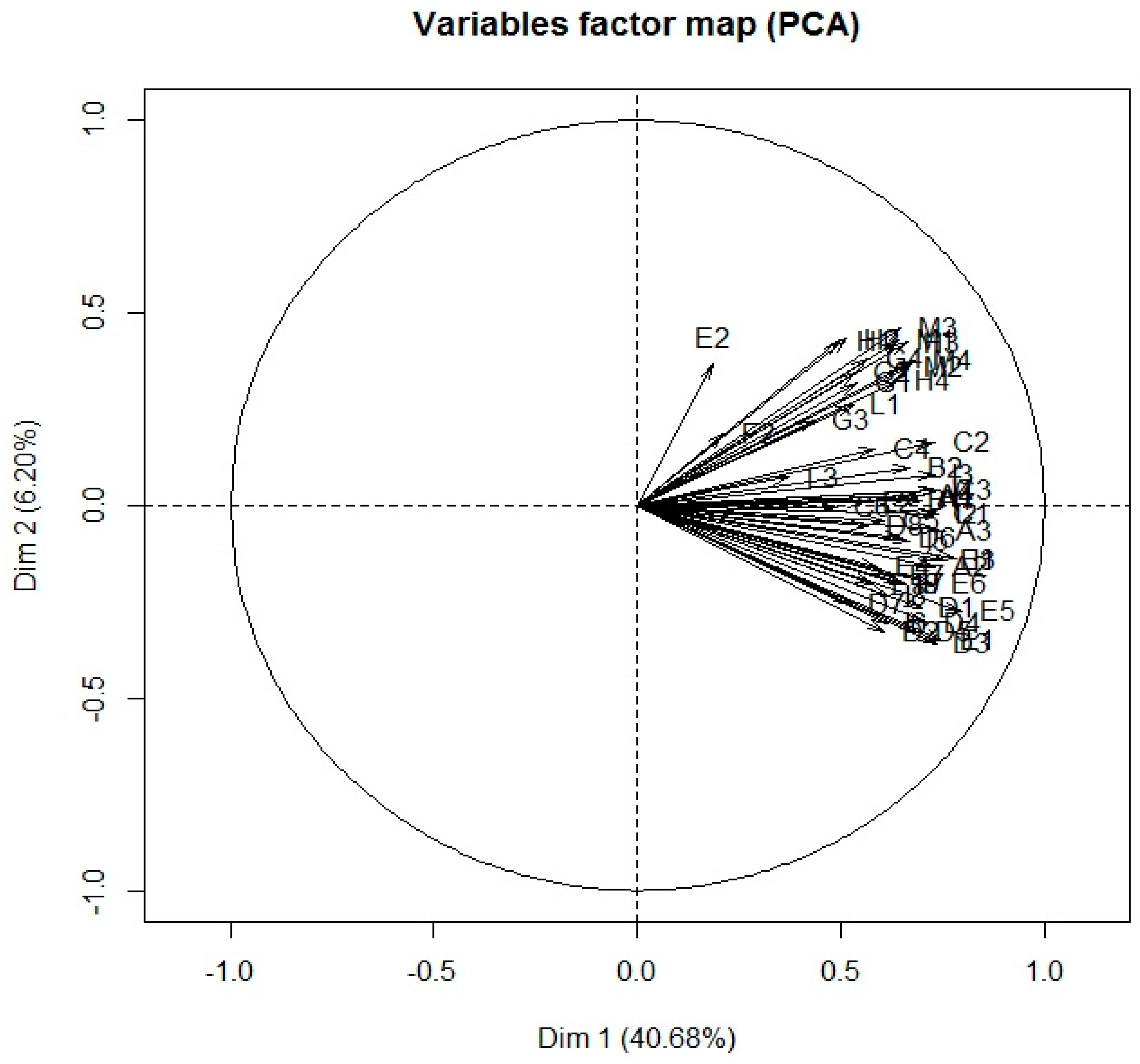

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimensions | Sub-Dimensions | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Quality of Interaction | A—Interpersonal interaction | A1—Staff has a pleasant demeanor A2—Staff looks nice and well cared for A3—Staff are understanding and reassuring A4—Staff can handle special requests |

| B—Problem solving skills | B1—Staff is skilled in apologising to customers B2—Staff are capable of handling problems and complaints | |

| C—Professional skills | C1—Staff is knowledgeable about the products on offer C2—Staff is skilled in handling requests C3—Staff shows good training and experience C4—Staff speaks an understandable language C5—Staff are able to inform you about something that is not available that day C6—Staff also speaks languages other than Italian | |

| Quality of the Environment | D—General questions as to environment | D1—The wall decorations of the restaurant are pleasant D2—The spaces between the tables are adequate D3—The interior furnishings of the restaurant are pleasant D4—The tables set up for catering are comfortable D5—The seating is comfortable D6—The lighting of the dining room is adequate D7—The background music is pleasant D8—The temperature of the dining room is pleasant |

| E—Cleaning in restaurant | E1—The perceived cleanliness is satisfactory E2—Prepackaged toppings are available E3—The staff seem neat and clean E4—The kitchen (if open) seems to be managed in a hygienically correct way E5—The catering areas are clean and welcoming E6—The toilets are clean and well maintained | |

| F—Layout and design | F1—Parking available near the restaurant F2—The outside of the restaurant has an attractive appearance F3—In the catering rooms can feel a pleasant scent | |

| G—Menu design | G1—Menus are easy to read G2—Menus are easy to understand G3—Menus are written in a foreign language (if any) with explanations G4—Menus reflect the theme, image, and price range of the restaurant | |

| Quality of the Result | H—Restaurant experience | H1—Waiting time to sit down is reasonable H2—The restaurant interprets the type of experience the consumer desires H3—The staff serve the customers on time H4—After consuming the meal, the experience met expectations |

| I—Quality of food/supply chain | I1—The food is fresh and well cooked I2—The food is attractive and tempting I3—The food consumed meets expectations I4—Food satisfies the sensory needs I5—Food satisfies the desired nutritional intake I6—The supply chain meets the needs related to animal welfare I7—The supply chain satisfies the ethical and social needs I8—The raw materials used are of local origin I9—The raw materials used are of national origin | |

| L—Menu quality | L1—The food meets the nutritional needs of consumers L2—The proposed food is one of a kind L3—the proposed food cannot be prepared at home | |

| Quality of the price/quality ratio | M—Quality/price ratio (the primary dimension is not divided into sub-dimensions) | M1—Compared to the service used, the quality-price ratio is adequate M2—Compared to the raw materials used, the quality-price ratio is adequate M3—Compared to the food consumed, the quality-price ratio is adequate M4—Overall, compared to the product/service used, the quality-price ratio is adequate |

References

- Abrahale, K., Sandra Sousa, Gabriela Albuquerque, Patrícia Padrão, and Nuno Lunet. 2019. Street food research worldwide: A scoping review. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 32: 152–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almli, Valérie Lengard, Wim Verbeke, Filiep Vanhonacker, Tormod Næs, and Margrethe Hersleth. 2011. General image and attribute perceptions of traditional food in six European countries. Food Quality and Preference 22: 129–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Geoff. 2008. The Slow Food Story: Politics and Pleasure. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arcese, Gabriella, Serena Flammini, Maria Caludia Lucchetti, and Olimpia Martucci. 2015. Evidence and experience of open sustainability innovation practices in the food sector. Sustainability 7: 8067–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barone, Michele, and Alessandra Pellerito. 2020. The Street Food Culture in Europe. In Sicilian Street Foods and Chemistry. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bellia, Claudio, Manuela Pilato, and Hugues Seraphin. 2016. Street food and food safety: A driver for tourism? Calitatea 17: 20. [Google Scholar]

- Besson, Théo, Hugo Bouxom, and Thibault Jaubert. 2020. Halo it’s meat! The effect of the vegetarian label on calorie perception and food choices. Ecology of Food and Nutrition 59: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonadonna, Alessandro, Simona Alfiero, Massimo Cane, and Edyta Gheribi. 2019. Eating hamburgers slowly and sustainably: The fast food market in north-west Italy. Agriculture 9: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonadonna, Alessandro, Chiara Giachino, Francesca Pucciarelli, and Bernardo Bertoldi. 2020. The evolution of fast food in a customer-driven era: Innovation and sustainability for customer needs. In Customer Satisfaction and Sustainability Initiatives in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Edited by Silvestri Cecilia, Aquilani Barbara and Piccarozzi Michela. Pennsylvania: IGI Global, pp. 251–69. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, Michael K., and J. Joseph Cronin Jr. 2001. Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: A hierarchical approach. Journal of Marketing 65: 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burnier, Pedro Carvalho, Eduardo Eugênio Spers, and Marcia Dutra de Barcellos. 2021. Role of sustainability attributes and occasion matters in determining consumers’ beef choice. Food Quality and Preference 88: 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappella, Francesco, Paolo Giaccaria, and Giovanni Peira. 2015. La Filiera Della Carne Piemontese: Scenari Possibili. Torino: IRES Piemonte. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone, Anna. 2018. Foods and places: Comparing different supply chains. Agriculture 8: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cardozo, Richard N. 1965. An Experimental Study of Customer Effort, Expectation, and Satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research 2: 244–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carzedda, Matteo, Francesco Marangon, Federico Nassivera, and Stefania Troiano. 2018. Consumer satisfaction in Alternative Food Networks (AFNs): Evidence from Northern Italy. Journal of Rural Studies 64: 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, Gilbert A., and Carol Surprenant. 1982. An Investigation into the Determinants of Customer Satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research 19: 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciavolino, Enrico, and Jens J. Dahlgaard. 2007. ECSI—Customer satisfaction modelling and analysis: A case study. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 18: 545–54. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, Alice, Sarah A. Humphries, and Margaret M. Geddy. 2015. McDonald’s: A Case Study in Glocalization. Journal of Global Business Issues 9: 11. [Google Scholar]

- Dabholkar, Pratibha A., Dayle I. Thorpe, and Joseph O. Rentz. 1996. A measure of service quality for retail stores: Scale development and validation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 24: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgaard-Park, Su Mi. 2012. Core values—The entrance to human satisfaction and commitment. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 23: 125–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dastane, Omkar, and Intan Fazlin. 2017. Re-investigating key factors of customer satisfaction affecting customer retention for fast food industry. International Journal of Management, Accounting and Economics 4: 379–400. [Google Scholar]

- De Bernardi, Alberto. 2015. I consumi alimentari in Italia: Uno specchio del cambiamento. In L’Italia e le Sue Regioni. L’età Repubblicana. Edited by Salvati Mariuccia and Sciolla Loredana. Milano: Treccani. [Google Scholar]

- Farahiyan, Leila, Sanjay S. Kaptan, and S. U. Jadhavar. 2015. An exploratory study of fast food restaurant selection criteria amongst college students through conjoint analysis. Journal of Commerce and Management Thought 6: 487–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forno, Francesca, Cristina Grasseni, and Silvana Signori. 2013. Oltre la spesa. I Gruppi di Acquisto Solidale come laboratori di cittadinanza e palestre di democrazia. Sociologia del Lavoro 132: 127–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gudiño, Javier, Isabel Blanco-Penedo, Marina Gispert, Albert Brun, José Perea, and Maria Font-i-Furnols. 2021. Understanding consumers’ perceptions towards Iberian pig production and animal welfare. Meat Science 172: 108317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheribi, Edyta. 2017. Corporate social responsibility in gastronomy business in Poland on selected example. European Journal of Service Management 23: 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gross, Sabine, Megan E. Waldrop, and Jutta Roosen. 2021. How does animal welfare taste? Combining sensory and choice experiments to evaluate willingness to pay for animal welfare pork. Food Quality and Preference 87: 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, Federica. 2012. Bar, fast food e tavole calde: Nomi e funzioni dei locali di ristoro nelle città romane dell’Impero. LANX. Rivista della Scuola di Specializzazione in Archeologia-Università degli Studi di Milano, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grow, H. Mollie, and Marlene B. Schwartz. 2014. Food marketing to youth: Serious business. JAMA Journal of the American Medical Association 312: 1918–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, Luis, Anna Claret, Wim Verbeke, Geraldine Enderli, Sylwia Zakowska-Biemans, Filiep Vanhonacker, Sylvie Issanchou, Marta Sajdakowska, Britt Signe Granli, Luisa Scalvedi, and et al. 2010. Perception of traditional food products in six European regions using free word association. Food Quality and Preference 21: 225–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemple, Donald J. 1977. Consumer satisfaction with the home buying process: Conceptualization and measurement. In The Conceptualization of Consumer Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction. Edited by Keith Hunt. Cambridge: Marketing Science Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Jillian, Zandile Mchiza, Jean Fourie, Thandi Puoane, and Nelia Steyn. 2016. Consumption patterns of street food consumers in Cape Town. Journal of Consumer Sciences 1: 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, John A., and Jagdish N. Sheth. 1969. The Theory of Buyer Behavior. New York. 63. Available online: https://books.google.it/books?hl=it&lr=&id=HLuo1sawoAYC&oi=fnd&pg=PA81&dq=%22A+Theory+of+Buyer+Behavior%22&ots=IfkCaT7tTw&sig=wH59w8l0-IvldFQWUYhlUJ8QdZ8&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=%22A%20Theory%20of%20Buyer%20Behavior%22&f=false (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Hultén, Bertil. 2011. Sensory marketing: The multi-sensory brand-experience concept. European Business Review 23: 256–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifeanyichukwu, Chioma, and Abude Peter. 2018. The Role of Sensory Marketing in Achieving Customer Patronage in Fast Food Restaurants in Awka. International Research Journal of Management, IT & Social Sciences 5: 155–63. [Google Scholar]

- Jaini, Azila, Nor Asma Ahmad, and Siti Zamanira Mat Zaib. 2015. Determinant factors that influence customers’ experience in fast food restaurants in Sungai Petani, Kedah. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Business 3: 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Joe, Meeyoung, Seoki Lee, and Sunny Ham. 2020. Which brand should be more nervous about nutritional information disclosure: McDonald’s or Subway? Appetite 155: 104805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowitt, Beth. 2014. Fallen Arches: Can McDonald’s Get Its Mojo Back. Available online: https://fortune.com/2014/11/12/can-mcdonalds-get-its-mojo-back/ (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Kumpulainen, Tommi, Annukka Vainio, Mari Sandell, and Anu Hopia. 2018. How young people in Finland respond to information about the origin of food products: The role of value orientations and product type. Food Quality and Preference 68: 173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Alvin, and Claire Lambert. 2017. Corporate social responsibility in McDonald’s Australia. Asian Case Research Journal 21: 393–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Nicole, Qiushi Huang, Patrick Merkel, Dong Keun Rhee, and Allison C. Sylvetsky. 2020. Differences in the sugar content of fast-food products across three countries. Public Health Nutrition. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Weng-Kun, Yueh-Shian Lee, and Li-Mei Hung. 2017. The interrelationships among service quality, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty: Examination of the fast-food industry. Journal of Foodservice Business Research 20: 146–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastronardi, Luigi, Luca Romagnoli, Giampiero Mazzocchi, Vincenzo Giaccio, and Davide Marino. 2019. Understanding consumer’s motivations and behaviour in alternative food networks. British Food Journal 121: 2102–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, Surbhi. 2017. Glocalization in Fast Food Chains: A Case Study of McDonald’s. In Strategic Marketing Management and Tactics in the Service Industry. Pennsylvania: IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Kevin. 2009. Feeding the city: The challenge of urban food planning. International Planning Studies 14: 341–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Kevin. 2015. Nourishing the city: The rise of the urban food question in the Global North. Urban Studies 52: 1379–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosi, Costanza, and Lorenzo Zanni. 2004. Moving from “typical products” to “food-related services”. The Slow Food case as a new business paradigm. British Food Journal 106: 779–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, Giuseppe. 2007. Cibo veloce e cibo di strada. Le tradizioni artigianali del fast-food in Italia alla prova della globalizzazione. Storicamente 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, Claudio. 2006. The universe of food quality. Food Quality and Preference 17: 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petimar, Joshua, Maricelle Ramirez, Sheryl L. Rifas-Shiman, Stephanie Linakis, Jewel Mullen, Christina A. Roberto, and Jason P. Block. 2019. Evaluation of the impact of calorie labeling on McDonald’s restaurant menus: A natural experiment. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 16: 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, Dacinia Crina, Iris Vermeir, and Ruxandra Malina Petrescu-Mag. 2020. Consumer understanding of food quality, healthiness, and environmental impact: A cross-national perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrini, Carlo. 2003. Slow Food: The Case for Taste. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petrini, Carlo. 2013. Slow Food Nation: Why Our Food Should Be Good, Clean, and Fair. Milano: Rizzoli Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pícha, Kamil, Josef Navrátil, and Roman Švec. 2018. Preference to local food vs. preference to “national” and regional food. Journal of Food Products Marketing 24: 125–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitte, Jean-Robert. 1997. Nascita e diffusione dei ristoranti. In Storia Dell’alimentazione. Edited by Jean-Louis Flandrin and Massimo Montanari. Bari: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Poulain, Jean-Pierre. 2017. The Sociology of Food. Eating and the Place of Food in Society. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Renting, Henk, Terry K. Marsden, and Jo Banks. 2003. Understanding alternative food networks: Exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environment and Planning A 35: 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ritzer, George, and Nicola Rainò. 1997. Il Mondo alla McDonald’s. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Saghaian, Sayed, and Hosein Mohammadi. 2018. Factors affecting frequency of fast food consumption. Journal of Food Distribution Research 49: 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sajdakowska, Marta, Paweł Jankowski, Krystyna Gutkowska, Dominika Guzek, Sylwia Żakowska-Biemans, and Irena Ozimek. 2018. Consumer acceptance of innovations in food: A survey among Polish consumers. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 17: 253–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifani, Giorgio, and Giuseppina Migliore. 2011. Solidarity Purchase Groups and the new critical and ethical consumer trends: First results of a direct study in Sicily. New Medit 3: 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sezgin, Aybuke Ceyhun, and Nevin Şanlıer. 2016. Street food consumption in terms of the food safety and health. Journal of Human Sciences 13: 4072–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siddiqua, A. Ayesha, and I. Mohamed Shaw Alem. 2018. Impact of situational factors in students’ preference of fast food—An empirical study. Clear International Journal of Research in Commerce & Management 9: 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Simi, Demi, and Jonathan Matusitz. 2017. Glocalization of Subway in India: How a US Giant Has Adapted in the Asian Subcontinent. Journal of Asian and African Studies 52: 573–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thaichon, Park, Sara Quach, and Jiraporn Surachartkumtonkun. 2019. Intention to purchase at a fast food store: Excitement, performance and threshold attributes. Asian Journal of Business Research 9: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregear, Angela. 2011. Progressing knowledge in alternative and local food networks: Critical reflections and a research agenda. Journal of Rural Studies 27: 419–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trichopoulou, Antonia, Stavroula Soukara, and Effie Vasilopoulou. 2007. Traditional foods: A science and society perspective. Trends in Food Science & Technology 18: 420–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tse, David K., and Peter C. Wilton. 1988. Models of consumer satisfaction formation: An extension. Journal of Marketing 52: 204–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichselbaum, Elisabeth, Bridget Benelam, and H. Soares Costa. 2009. Traditional Foods in Europe. Norwich: EuroFIR Project. Available online: https://www.eurofir.org/wp-admin/wp-content/uploads/EuroFIR%20synthesis%20reports/Synthesis%20Report%206_Traditional%20Foods%20in%20Europe.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- Wu, Hung-Che, and Zurinawati Mohi. 2015. Assessment of service quality in the fast-food restaurant. Journal of Foodservice Business Research 18: 358–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarimoglu, Emel Kursunluoglu, and Aylin Banu Satana. 2016. Students’ insights regarding sales promotion tools: A preliminary study of the fast food industry. ASBBS Proceedings 23: 561. [Google Scholar]

- Yip, Joanne, Heidi HT Chan, Bonny Kwan, and Derry Law. 2011. Influence of appearance orientation, BI and purchase intention on customer expectations of service quality in Hong Kong intimate apparel retailing. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 22: 1105–18. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Jong Pil, Payal Kaishap Dutta, and Dawn Thorndike Pysarchik. 2007. The impact of reference groups and product familiarity on Indian consumers’ product purchases. Journal of Global Academy of Marketing Science 17: 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Lin, Deepa Anagondahalli, and Ai Zhang. 2017. Social media and culture in crisis communication: McDonald’s and KFC crises management in China. Public Relations Review 43: 487–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample (no.) | 227 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | Female | 73.57 |

| Male | 26.43 | |

| Age (mean) (years) | 26.96 | |

| Occupation (%) | Student | 56.39 |

| Worker | 39.21 | |

| Other | 4.40 | |

| Preferred hamburger restaurant | McDonald’s | 52.86 |

| Burger King | 14.10 | |

| M** Bun | 15.42 | |

| L’Hamburgheria di Eataly | 3.52 | |

| Others | 8.37 | |

| Visit (frequency) | once a year | 3.52 |

| 3–4 times a year | 48.90 | |

| monthly | 30.84 | |

| weekly | 6.61 | |

| other | 6.17 |

| Sub-Dimensions | Mean | Standard Deviation | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| A—Interpersonal interaction | 4.72 | 1.43 | 2.06 |

| B—Problem solving skills | 4.79 | 1.38 | 1.93 |

| C—Professional skills | 5.07 | 1.38 | 1.92 |

| D—General questions as to the environment | 4.77 | 1.47 | 2.19 |

| E—Cleaning in the restaurant | 4.72 | 1.55 | 2.42 |

| F—Layout and design | 4.66 | 1.69 | 2.88 |

| G—Menu design | 5.09 | 1.57 | 2.5 |

| H—Restaurant experience | 5.45 | 1.26 | 1.61 |

| I—Quality of food/supply chain | 4.31 | 1.72 | 3.04 |

| L—Menu quality | 4.12 | 1.75 | 3.08 |

| M—Quality/price ratio | 4.87 | 1.50 | 2.26 |

| Sub-Dimensions | McDonald’s | Burger King | M** Bun | L’Hamburgheria di Eataly |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 4.23 | 4.65 | 5.33 | 5.62 |

| B | 4.37 | 4.94 | 5.35 | 5.68 |

| C | 4.60 | 5.28 | 5.63 | 5.50 |

| D | 4.42 | 4.82 | 5.49 | 5.19 |

| E | 3.86 | 4.75 | 5.55 | 5.28 |

| F | 4.60 | 5.22 | 5.11 | 5.25 |

| G | 4.89 | 4.90 | 5.41 | 5.68 |

| H | 5.41 | 5.39 | 5.82 | 5.50 |

| I | 3.93 | 4.23 | 5.90 | 5.59 |

| L | 4.26 | 4.06 | 4.78 | 5.00 |

| M | 4.79 | 4.74 | 5.43 | 5.03 |

| Items | Mean | McDonald’s (Mean) | Burger King (Mean) | M** Bun (Mean) | L’Hamburgheria di Eataly (Mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I6 | 3.663 | 3.00 | 3.37 | 5.35 | 5.66 |

| I7 | 3.738 | 3.13 | 3.44 | 5.48 | 5.33 |

| I8 | 3.693 | 2.72 | 3.48 | 5.96 | 5.62 |

| I9 | 4.052 | 3.44 | 3.48 | 6.13 | 5.75 |

| L2 | 3.615 | 3.02 | 3.37 | 4.67 | 5.37 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giachino, C.; Terrevoli, N.; Bonadonna, A. Local vs. International Hamburger Foodservice in the Consumer’s Mind: An Exploratory Study. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10070252

Giachino C, Terrevoli N, Bonadonna A. Local vs. International Hamburger Foodservice in the Consumer’s Mind: An Exploratory Study. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(7):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10070252

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiachino, Chiara, Niccolò Terrevoli, and Alessandro Bonadonna. 2021. "Local vs. International Hamburger Foodservice in the Consumer’s Mind: An Exploratory Study" Social Sciences 10, no. 7: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10070252