Social Support and Self-Efficacy on Turnover Intentions: The Mediating Role of Conflict and Commitment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

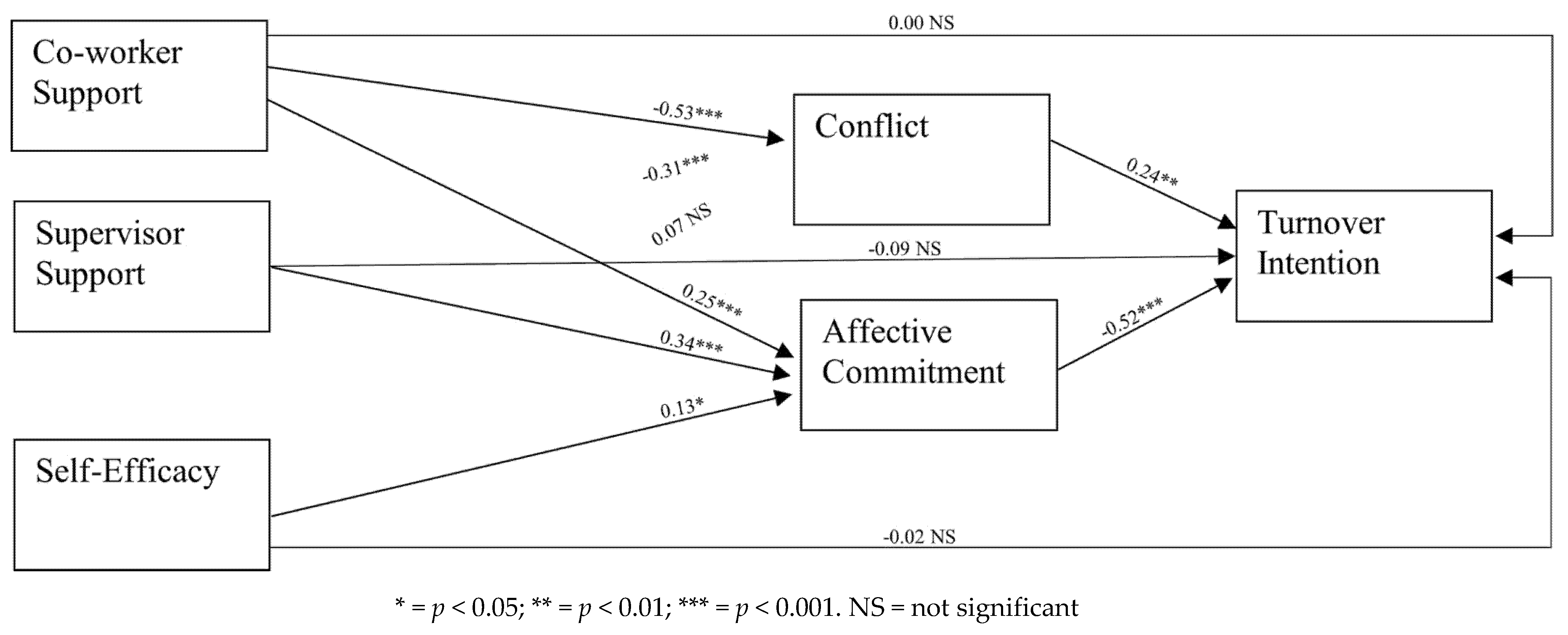

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Collection and Sample Characteristics

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Descriptive Analyses, Correlations and Reliability

4.3. Hypothesis Tests

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afzal, Hafiza F., Anwarul K. M. Islam, Adnan Ismail, Muhammad Y. Tahir, Muhammad Zohaib, Jamshaid Riaz, and Muhammad Ismail. 2021. The role of underemployment in turnover intention through job deprivation and job stress: A multiple mediation mechanism. International Journal of Business and Management Future 5: 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, Sadia, Muhammad Arshad, Sharjeel Saleem, and Omer Farooq. 2019. The impact of perceived supervisor support on employees’ turnover intention and task performance: Mediation of self-efficacy. The Journal of Management Development 38: 369–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agu, Ogechi L. 2015. Work engagement, organizational commitment, self-efficacy and organizational growth: A literature review. Information Impact: Journal of Information and Knowledge Management 6: 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ahammad, Mohammad F., Keith W. Glaister, Riikka M. Sarala, and Alison J. Glaister. 2018. Strategic Talent Management in Emerging Markets. Thunderbird International Business Review 60: 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlaghimofrad, Asieh, and Panteha Farmanesh. 2021. The association between interpersonal Conflict, turnover intention and knowledge hiding: The mediating role of employee cynicism and moderating role of emotional intelligence. Management Science Letters 11: 2081–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi, Benjamin, Babu George, and Alice Ogundele. 2022. Relationship between Job Satisfaction, Pay, Affective Commitment and Turnover Intention among Registered Nurses in Nigeria. Global Journal of Health Science 14: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkahtani, Ali H. 2015. Investigating factors that influence employees’ turnover intention: A review of existing empirical works. International Journal of Business and Management 10: 152–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhateri, Asma S., Abuelhassan E. Abuelhassan, Gamal S.A. Khalifa, Mohammed Nusari, and Ali Ameen. 2018. The Impact of perceived supervisor support on employees turnover intention: The Mediating role of job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment. International Business Management 12: 477–92. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, David. G., and Linda Rhoades Shanock. 2013. Perceived organizational support and embeddedness as key mechanisms connecting socialization tactics to commitment and turnover among new employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior 34: 350–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Natalie J., and John P. Meyer. 1990. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology 63: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Natalie J., and John P. Meyer. 1997. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application. New York: Sage Publications, p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- Alper, Steve, Dean Tjosvold, and Kenneth S. Law. 2000. Conflict management, efficacy, and performance in organizational teams. Personnel Psychology 53: 625–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosius, Judith. 2018. Strategic talent management in emerging markets and its impact on employee retention: Evidence from Brazilian MNCs. Thunderbird International Business Review 60: 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arici, Hasan Evrim. 2018. Perceived supervisor support and turnover intention: Moderating effect of authentic leadership. Leadership and Organization Development Journal 39: 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, Richard P., and Youjae Yi. 1988. On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of The Academy of Marketing Science 16: 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Diane F. 2001. The development of collective efficacy in small task groups. Small Group Research 32: 451–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 84: 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1997. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 2017. Cultivate Self-Efficacy for Personal and Organizational Effectiveness. In The Blackwell Handbook of Principles of Organizational Behavior. Edited by Edwin A. Locke. New York: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 125–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert, and Daniel Cervone. 1983. Self-Evaluative and self-efficacy mechanisms governing the motivational effects of goal systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 45: 1017–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert, and Daniel Cervone. 1986. Differential engagement of self-reactive influences in cognitive motivation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 38: 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert, Nancy E. Adams, Arthur B. Hardy, and Gary N. Howells. 1980. Tests of the generality of self-efficacy theory. Cognitive Therapy and Research 4: 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, Hans, and Christian Homburg. 1996. Applications of Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing and Consumer Research: A review. International Journal of Research in Marketing 13: 139–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayazit, Mahmut, and Elizabeth A. Mannix. 2003. Should I stay or should I go? Predicting team members’ intent to remain in the team. Small Group Research 34: 290–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, Nuran, Necmi Gursakal, and Nazan Bilgel. 2009. Counterproductive work behavior among white-collar employees: A study from Turkey. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 17: 180–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, Peter M., and Douglas G. Bonnet. 1980. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychological Bulletin 88: 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhayo, Abdul Razzaque, Naimatullah Shah, and Ayaz Ahmed Chachar. 2017. The impact of interpersonal Conflict and job stress on employee’s turnover intention. International Research Journal of Arts & Humanities (IRJAH) 45: 179–91. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, Peter M. 2017. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Routledge, p. 372. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaccio, Silvia, Laurent M. Lapierre, and Jane O’Reilly. 2019. Creating work climates that facilitate and maximize the benefits of disclosing mental health problems in the workplace. Organizational Dynamics 48: 113–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgogni, Laura, Silvia Dello Russo, Laura Petitta, and Michele Vecchione. 2010. Predicting job satisfaction and job performance in a privatized organization. International Public Management Journal 13: 275–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, Peter, Ann Hutchison, and Brigitta Wassenaar. 2015. How do high-involvement work processes influence employee outcomes? An examination of the mediating roles of skill utilisation and intrinsic motivation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 26: 1737–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, John W., Richard D. Arvey, and Peggy Lawless. 1996. Correlates and consequences of workplace violence. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 1: 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, Gaëtane, Florence Stinglhamber, Stéphanie Demoulin, Matthias De Wilde, and Adrien Mierop. 2019. Perceived organizational support and workplace conflict: The mediating role of failure-related trust. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, Gaëtane, Géraldine Marique, and Florence Stinglhamber. 2014. The relationship between perceived organizational support and Affective Commitment: More than reciprocity, it is also a question of organizational identification. Journal of Personnel Psychology 13: 167–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chami-Malaeb, Rola. 2021. Relationship of perceived supervisor support, self-efficacy and turnover intention, the mediating role of burnout. Personnel Review 51: 1003–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Man-Ling. 2017. On the relationship between intragroup Conflict and social capital in teams: A longitudinal investigation in Taiwan. Journal of Organizational Behavior 38: 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Aaron. 1993. Work commitment in relation to withdrawal intentions and union effectiveness. Journal of Business Research 26: 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle-Shapiro, Jacqueline A. M., Paula C. Morrow, and Ian Kessler. 2006. Serving two organizations: Exploring the employment relationship of contracted employees. Human Resource Management 45: 561–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, Dirk, Muhammad Umer Azeem, Inam Ul Haq, and Dave Bouckenooghe. 2020. The stress-reducing effect of coworker support on Turnover Intentions: Moderation by political ineptness and despotic leadership. Journal of Business Research 111: 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, Carsten K. W., Dirk Van Dierendonck, and Maria T. M. Dijkstra. 2004. Conflict at work and individual well-being. International Journal of Conflict Management 15: 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, Carsten K. W., Fieke Harinck, and Annelies E. M. Van Vianen. 1999. Conflict and performance in groups and organizations. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Edited by Cary L. Cooper and Ivan T. Robertson. New York: Wiley, pp. 69–414. [Google Scholar]

- De Raeve, Lore, Nicole W. H. Jansen, Piet van den Brandt, Rineke M. Vasse, and IJmert Kant. 2008. Risk factors for interpersonal conflicts at work. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 34: 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- De Simone, Silvia, and Anna Planta. 2017. L’intenzione di lasciare il lavoro nel personale infermieristico: Il ruolo della soddisfazione lavorativa. Medicina del Lavoro, Work, Environment and Health 108: 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- De Simone, Silvia, Anna Planta, and Cicotto Gianfranco. 2018. The role of job satisfaction, work engagement, self-efficacy and agentic capacities on nurses’ turnover intention and patient satisfaction. Applied Nursing Research 39: 130–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, Silvia, Jessica Pileri, Marina Mondo, Max Rapp-Ricciardi, and Barbara Barbieri. 2022. Mea Culpa! The Role of Guilt in the Work-Life Interface and Satisfaction of Women Entrepreneur. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 10781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilla, Dewi Atmi, and Haznil Zainal. 2022. Social Support and Affective Commitment: Mediation Mechanisms of Relational Attachment. Sains Organisasi 1: 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, William J., Weidong Xia, and Gholamreza Torkzadeh. 1994. A confirmatory factor analysis of the end-user computing satisfaction instrument. MIS Quarterly 18: 357–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, Michelle A., Fritz Drasgow, and Liberty J. Munson. 1998. The Perceptions of Fair Interpersonal Treatment Scale: Development and validation of a measure of interpersonal treatment in the workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology 83: 683–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducharme, Lori J., Hannah K. Knudsen, and Paul M. Roman. 2007. Emotional exhaustion and turnover intention in human service occupations: The protective role of coworker support. Sociological Spectrum 28: 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatough, Erin M. 2010. Understanding the Relationships between Interpersonal Conflict at Work, Perceived Control, Coping, and Employee Well-Being. Master’s dissertation, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA. Available online: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/1623/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Eisenberger, Robert, Linda Rhoades, and Judy Cameron. 1999. Does pay for performance increase or decrease perceived self-determination and intrinsic motivation? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77: 1026–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, Robert, Mindy Krischer Shoss, Gökhan Karagonlar, M. Gloria Gonzalez-Morales, Robert E. Wickham, and Louis C. Buffardi. 2014. The supervisor POS–LMX–subordinate POS chain: Moderation by reciprocation wariness and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. Journal of Organizational Behavior 35: 635–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, Robert, Peter Fasolo, and Valerie Davis-LaMastro. 1990. Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. Journal of Applied Psychology 75: 51–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, Robert, Robin Huntington, Steven Hutchison, and Debora Sowa. 1986. Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology 71: 500–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, Robert, Stephen Armeli, Barnara Rexwinkel, Patrick D. Lynch, and Linda Rhoades. 2001. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, John, Baiyun Gong, Randi Sims, and Yuliya Yurova. 2017. The role of Affective Commitment in the relationship between social support and turnover intention. Management Decision 55: 512–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statics. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 382–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, Sadaaki, Wei Wu, and Michelle P. Salyers. 2019a. Impact of supervisory support on turnover intention: The mediating role of burnout and job satisfaction in a longitudinal study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 46: 488–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui, Sadaaki, Wei Wu, and Michelle P. Salyers. 2019b. Mediational paths from supervisor support to turnover intention and actual turnover among community mental health providers. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 42: 350–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galletta, Maura, Igor Portoghese, Maria Pietronilla Penna, Adalgisa Battistelli, and Luisa Saiani. 2011. Turnover intention among Italian nurses: The moderating roles of supervisor support and organizational support. Nursing & Health Sciences 13: 184–91. [Google Scholar]

- Giebels, Ellen, and Onne Janssen. 2005. Conflict stress and reduced well-being at work: The buffering effect of third-party help. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 14: 137–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, Alicia A., Julie H. Kern, and Michael R. Frone. 2007. Verbal abuse from outsiders versus insiders: Comparing frequency, impact on emotional exhaustion, and the role of emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 12: 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffeth, Rodger W., Peter W. Hom, and Stefan Gaertner. 2000. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management 26: 463–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnaccia, Cinzia, Fabrizio Scrima, Alba Civilleri, and Laura Salerno. 2018. The role of occupational self-efficacy in mediating the effect of job insecurity on work engagement, satisfaction and general health. Current Psychology 37: 488–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2011. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 19: 139–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Lucy M. Matthews, Ryan L. Matthews, and Marko Sarstedt. 2017. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis 1: 107–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Rolph E. Anderson, Ronald E. Tatham, and William C. Black. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis. Hoboken: Prentice-Hall, p. 832. [Google Scholar]

- Hauge, Lars Johan, Anders Skogstad, and Ståle Einarsen. 2007. Relationships between stressful work environments and bullying: Results of a large representative study. Work & Stress 21: 220–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hellervik, Lowell W., Joy Fisher Hazucha, and Robert J. Schneider. 1992. Behavior change: Models, methods, and a review of evidence. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2nd ed. Edited by Marvin D. Dunnette and Leaetta M. Hough. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press, pp. 823–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hongvichit, Somchit. 2015. The research progress and prospect of employee turnover intention. International Business Research 8: 218–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Yu-Ping, Chun-Yang Peng, Ming-Tao Chou, Chun-Tsen Yeh, and Qiong-yuan Zhang. 2020. Workplace friendship, helping behavior, and turnover intention: The meditating effect of Affective Commitment. Advances in Management and Applied Economics 10: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Jichul, and Jay Kandampully. 2018. Reducing employee turnover intention through servant leadership in the restaurant context: A mediation study of affective organizational commitment. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration 19: 125–41. [Google Scholar]

- Jeung, Chang-Wook, Hea Jun Yoon, and Myungweon Choi. 2017. Exploring the affective mechanism linking perceived organizational support and knowledge sharing intention: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Knowledge Management 21: 946–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Jianwan, and Jinzhe Yan. 2022. Study on the Effect of Employees’ Perceived Organizational Support, Psychological Ownership, and Turnover Intention: A Case of China’s Employee. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartika, Galih, and Debora Eflina Purba. 2018. Job satisfaction and turnover intention: The mediating effect of Affective Commitment. Psychological Research on Urban Society 1: 100–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Muhammad Iqbal, Syed Haider Ali Shah, Aftab Haider, Shahab Aziz, and Munaza Kazmi. 2020. The Role of Supervisor Support on Work-Family Conflict and Employee Turnover Intentions in the Workplace with Mediating Effect of Affective Commitment in Twin Cities in the Banking Industry, Pakistan. International Review of Management and Marketing 10: 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hyeoneui, and Eun Gyung Kim. 2021. A meta-analysis on predictors of turnover intention of hospital nurses in South Korea (2000–2020). Nursing Open 8: 2406–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, Bradley L., and Benson Rosen. 1999. Beyond self-management: Antecedents and consequences of team empowerment. Academy of Management Journal 42: 58–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, Myeong Chul. 2021. An examination of the links between organizational social capital and employee well-being: Focusing on the mediating role of quality of work life. Review of Public Personnel Administration 4: 163–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraimer, Maria L., Scott Seibert, Sandy Wayne, Robert C. Liden, and Jesus Bravo. 2011. Antecedents and outcomes of organizational support for development: The critical role of career opportunities. Journal of Applied Psychology 96: 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundi, Yasir Mansoor, Malik Ikramullah, Muhammad Zahid Iqbal, and Faqir Sajjad Ul-Hassan. 2017. Affective Commitment as mechanism behind perceived career opportunity and Turnover Intentions with conditional effect of organizational prestige. Journal of Managerial Sciences 1: 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose, Vijay, S. Sreejesh, Heerah Jose, M. R. Anusree, and Shelly Jose. 2019. Process Conflict and employee well-being: An application of Activity Reduces Conflict Associated Strain (ARCAS) model. International Journal of Conflict Management 30: 462–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtessis, James N., Robert Eisenberger, Michael T. Ford, Louis C. Buffardi, Kathleen A. Stewart, and Cory S. Adis. 2017. Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management 43: 1854–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Kyongmin, and Woojeong Cho. 2018. The relationship between transformational leadership of immediate superiors, organizational culture, and Affective Commitment in fitness club employees. Sport Mont 16: 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, Tek-Yew. 2009. The relationships between perceived organizational support, felt obligation, affective organizational commitment and turnover intention of academics working with private higher educational institutions in Malaysia. European Journal of Social Sciences 9: 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, LiLin, and Shiqian Wang. 2018. Self-efficacy, organizational commitment, and employee engagement in small and medium-sized enterprises. International Journal of Business Marketing and Management (IJBMM) 3: 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Cong, Paul E. Spector, and Lin Shi. 2007. Cross-national job stress: A quantitative and qualitative study. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 28: 209–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobburi, Patipan. 2012. The influence of organizational and social support on turnover intention in collectivist contexts. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR) 28: 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Chang-Qin, Jing-Wei Sun, and Dan-Yang Du. 2016. The relationships between employability, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intention the moderation of perceived career opportunity. Journal of Career Development 43: 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, Carolina Machado Dias Ramalho, Sílvio Luiz de Paula, and Lúcia Maria Barbosa de Oliveira. 2018. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction and their possible influences on intent to turnover. Revista de Gestao USP 25: 84–102. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, David P., Chondra M. Lockwood, and Jason Williams. 2004. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research 39: 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertz, Carl P., Rodger W. Griffeth, Nathanael S. Campbell, and David G. Allen. 2007. The effects of perceived organizational support and perceived supervisor support on employee turnover. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 28: 1059–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marescaux, Elise, Sophie De Winne, and Luc Sels. 2013. HR practices and HRM outcomes: The role of basic need satisfaction. Personnel Review 42: 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marique, Géraldine, Florence Stinglhamber, Donatienne Desmette, Gaëtane Caesens, and Fabrice De Zanet. 2013. The relationship between perceived organizational support and Affective Commitment: A social identity perspective. Group & Organization Management 38: 68–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mauno, Saija, Ulla Kinnunen, and Mervi Ruokolainen. 2006. Exploring work-and organization-based resources as moderators between work–family Conflict, well-being, and job attitudes. Work & Stress 20: 210–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mercurio, Zachary A. 2015. Affective Commitment as a core essence of organizational commitment: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review 14: 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John P., and Natalie J. Allen. 1991. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review 1: 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John P., David J. Stanley, Lynne Herscovitch, and Laryssa Topolnytsky. 2002. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior 61: 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, Ana, Francisco Cesário, Maria José Chambel, and Filipa Castanheira. 2020. Competences development and Turnover Intentions: The serial mediation effect of perceived internal employability and Affective Commitment. European Journal of Management Studies 25: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namin, Boshra H., Torvald Øgaard, and Jo Røislien. 2022. Workplace Incivility and Turnover Intention in Organizations: A Meta-Analytic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, Sajjad, Amina Shafi, Wang Qun, Nadia Nazir, and Quang Dung Tran. 2016. Influence of organizational rewards on organizational commitment and Turnover Intentions. Employee Relations 38: 596–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, Sajjad, Wang Qun, Li Hui, and Amina Shafi. 2018. Influence of social exchange relationships on Affective Commitment and innovative behavior: Role of perceived organizational support. Sustainability 10: 4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Helena, Anya Johnson, Catherine Collins, and Sharon K. Parker. 2017. Confidence matters: Self-efficacy moderates the credit that supervisors give to adaptive and proactive role behaviours. British Journal of Management 28: 315–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Tuan D., Lam D. Pham, Michael Crouch, and Matthew G. Springer. 2020. The correlates of teacher turnover: An updated and expanded meta-analysis of the literature. Educational Research Review 31: 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, Helen M., Jennifer E. Swanberg, and Charlotte Lyn Bright. 2016. How does supervisor support influence turnover intent among frontline hospital workers? The mediating role of Affective Commitment. The Health Care Manager 35: 266–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoroge, David, Hazel Gachunga, and John Kihoro. 2015. Transformational leadership style and organizational commitment: The moderating effect of employee participation. The Strategic Journal of Business & Change Management 2: 94–107. [Google Scholar]

- Notelaers, Guy, Beatrice Van der Heijden, Hannes Guenter, Morten Birkeland Nielsen, and Ståle Valvetne Einarsen. 2018. Do interpersonal Conflict, aggression and bullying at the workplace overlap? A latent class modeling approach. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, Anthony J., and Robert E. Ployhart. 2013. Context-emergent turnover (CET) theory: A theory of collective turnover. Academy of Management Review 38: 109–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Hee Sook, and Hwee Wee. 2016. Self efficacy, organizational commitment, customer orientation and nursing performance of nurses in local public hospitals. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration 22: 507–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgambídez, Alejandro, Yolanda Borrego, and OctavioVázquez-Aguado. 2019. Self-efficacy and organizational commitment among Spanish nurses: The role of work engagement. International Nursing Review 66: 381–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palancı, Yılmaz, Cengiz Mengenci, Serkan Bayraktaroğlu, and Abdurrahim Emhan. 2020. Analysis of workplace health and safety, job stress, interpersonal Conflict, and turnover intention: A comparative study in the health sector. Health Psychology Report 9: 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, Gopal, Suguna Sinniah, Ramesh Kumar Moona Haji Mohamed, Kok Pooi Mun, and Uma Murthy. 2018. Turnover intention among manufacturing industry employees in Malaysia: An analysis using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). e-BANGI 13: 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pesch, Kathryn M., Lisa M.Larson, and Matthew T.Seipel. 2018. Career certainty and major satisfaction: The roles of information-seeking and occupational knowledge. Journal of Career Assessment 26: 583–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierro, Antonio, Ivana Lombardo, Fabbri Silvia, and Antonio Di Spirito. 1995. Evidenza Empirica della Validità Discriminante delle Misure di Job Involvement e Organizational Commitment: Modelli di Analisi Fattoriale e Confermativa (via LISREL). Testistic Psychometric Methodology 2: 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pinna, Roberta, Silvia De Simone, Gianfranco Cicotto, and Ashish Malik. 2020. Beyond organisational support: Exploring the supportive role of co-workers and supervisors in a multi-actor service ecosystem. Journal of Business Research 121: 524–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponterotto, Joseph G., and Daniel E. Ruckdeschel. 2007. An overview of coefficient alpha and a reliability matrix for estimating adequacy of internal consistency coefficients with psychological research measures. Perceptual and Motor Skills 105: 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, James L. 2001. Reflections on the determinants of voluntary turnover. International Journal of Manpower 22: 600–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raharjo, Kusdi, Nilawati Fiernaningsih, Umar Nimran, and Zainul Arifin. 2019. Impact of work–life balance and organizational citizenship behaviour on intention to leave. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change 8: 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim, M. Afzalur. 2017. Managing Conflict in Organizations. London: Routledge, p. 312. [Google Scholar]

- Ranihusna, Mukhodah D. 2018. Organizational Commitment As Intervening Variable of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation to Organizational Citizenship Behavior. KnE Social Sciences, 333–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Rukmini Devadas, and Linda Argote. 2006. Organizational learning and forgetting: The effects of turnover and structure. European Management Review 3: 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, Neerpal, and Renu Rastogi. 2009. Assessing the relationship between emotional intelligence, occupational self-efficacy and organizational commitment. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology 35: 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, Greg, Anthony J. Nyberg, Mark Maltarich, and Ingo Weller. 2014. Human capital flows: Using context-emergent turnover (CET) theory to explore the process by which turnover, hiring, and job demands affect patient satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal 57: 766–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reio, Thomas G., and Jeannie Trudel. 2013. Workplace incivility and Conflict management styles: Predicting job performance, organizational commitment and turnover intent. International Journal of Adult Vocational Education and Technology (IJAVET) 4: 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, Linda, Robert Eisenberger, and Stephen Armeli. 2001. Affective Commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 825–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, Neuza, Patrícia Duarte, and Jessica Fidalgo. 2020. Authentic leadership’s effect on customer orientation and turnover intention among Portuguese hospitality employees: The mediating role of Affective Commitment. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 32: 2097–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, Thomas, Birgit Schyns, and Gisela Mohr. 2008. A short version of the Occupational Self-Efficacy Scale: Structural and construct validity across five countries. Journal of Career Assessment 16: 238–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, Karen S. 2001. Emotional health and positive versus negative social exchanges: A daily diary analysis. Applied Developmental Science 5: 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, Jennifer A., and Benjamin H. Gottlieb. 2007. Development and initial validation of a measure of supportive and unsupportive managerial behaviors. Journal of Vocational Behavior 71: 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiller, Caroline, and Beatrice I. J. M. Van Der Heijden. 2016. Socio-emotional support in French hospitals: Effects on French nurses’ and nurse aides’ Affective Commitment. Applied Nursing Research 29: 229–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvador, Mónica, Anna Moreira, and Liliana Pitacho. 2022. Perceived Organizational Culture and Turnover Intentions: The Serial Mediating Effect of Perceived Organizational Support and Job Insecurity. Social Sciences 11: 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schat, Aaron C. H., and E. Kevin Kelloway. 2000. Effects of perceived control on the outcomes of workplace aggression and violence. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 5: 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schermelleh-Engel, Karin, Helfried Moosbrugger, and Hans Müller. 2003. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online 8: 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Self, Timothy T., and Susan Gordon. 2019. The impact of coworker support and organizational embeddedness on turnover intention among restaurant employees. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism 18: 394–423. [Google Scholar]

- Setiabudhi, Setiabudhi, Cholichul Hadi, and Seger Handoyo. 2021. Relationship Between Social Support, Affective Commitment, and Employee Engagement. Kontigensi: Jurnal Ilmiah Manajemen 9: 690–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, Razia, Amna Yousaf, and Karin Sanders. 2017. Examining the linkages between relationship Conflict, performance and Turnover Intentions: Role of job burnout as a mediator. Management 28: 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, Jason D., Nina Gupta, and John E. Delery. 2005. Alternative conceptualizations of the relationship between voluntary turnover and organizational performance. Academy of Management Journal 48: 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, Michael E. 1982. Asymptotic Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects in Structural Equation Models. Sociological Methodology 13: 290–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soelton, Mochamad, Putri Ayu Lestari, Harefan Arief, and Ratyuhono Linggarnusantra Putra. 2020. The effect of role conflict and burnout toward turnover intention at software industries, work stress as moderating variables. Paper presented at the 4th International Conference on Management, Economics and Business (ICMEB 2019), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, February 12. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, Paul E., and Steve M. Jex. 1998. Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal Conflict at work scale, organizational constraints scale, quantitative workload inventory, and physical symptoms inventory. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 3: 356–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, Gretchen M., Mark A. Kizilos, and Stephen W. Nason. 1997. A dimensional analysis of the relationship between psychological empowerment and effectiveness satisfaction, and strain. Journal of Management 23: 679–704. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, James H. 1990. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research 25: 173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ST-Hilaire, Walter Amedzro, and Catherine de la Robertie. 2018. Correlates of Affective Commitment in organizational performance: Multi-level perspectives. Australian Journal of Career Development 27: 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinglhamber, Florence, and Christian Vandenberghe. 2004. Favorable job conditions and perceived support: The role of organizations and supervisors 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 34: 1470–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovel, Meaghan, and Nick Bontis. 2002. Voluntary turnover: Knowledge management—Friend or foe? Journal of Intellectual Capital 3: 303–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, Alex M., K. Michele Kacmar, and Carl P. Borchgrevink. 2003. Customer service providers’ attitudes relating to customer service and customer satisfaction in the customer-server exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 179–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, Robert P., and John P. Meyer. 1993. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology 46: 259–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetteh, Stephen, Cisheng Wu, Christian Narh Opata, Gloria Nana Yaa Asirifua Agyapong, Richard Amoako, and Frank Osei-Kusi. 2020. Perceived organisational support, job stress, and turnover intention: The moderation of Affective Commitments. Journal of Psychology in Africa 30: 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Qing, Licheng Zhang, and Wenchi Zou. 2014. Job insecurity and counterproductive behavior of casino dealers–the mediating role of Affective Commitment and moderating role of supervisor support. International Journal of Hospitality Management 40: 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjosvold, D., and M. T. Tjosvold. 1994. Cooperation, Competition, and Constructive Controversy: Knowledge to Empower Self-Managing Teams. In Advances in Interdisciplinary Studies of Work Teams. Edited by Beyerlein Michael and Johnson Danielle Elaine. Cambridge: Elsevier Science/JAI Press, vol. 1, pp. 119–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tjosvold, Dean, and Mary M. Tjosvold. 1995. Cross functional teamwork: The challenge of involving professionals. In Advances in Interdisciplinary Studies of Work Teams. Edited by Beyerlein Michael and Johnson Danielle Elaine. Stamford: JAI Press, vol. 2, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Töre, Esra. 2020. Effects of Intrinsic Motivation on Teacher Emotional Labor: Mediating Role of Affective Commitment. International Journal of Progressive Education 16: 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremmel, Stephanie, Sabine Sonnentag, and Anne Casper. 2019. How was work today? Interpersonal work experiences, work-related conversations during after-work hours, and daily affect. Work & Stress 33: 247–67. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Ming-Ten, Chung-Lin Tsai, and Yi-Chou Wang. 2011. A study on the relationship between leadership style, emotional intelligence, self-efficacy and organizational commitment. A case study of the Banking Industry in Taiwan. African Journal of Business Management 5: 5319–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ugboro, Isaiah O. 2006. Organizational commitment, job redesign, employee empowerment and intent to quit among survivors of restructuring and downsizing. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management 7: 232–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dinther, Martvan, Filip Dochy, and Mien Segers. 2011. Factors affecting students’ self-efficacy in higher education. Educational Research Review 6: 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberghe, Christian, Kathleen Bentein, and Florence Stinglhamber. 2004. Affective Commitment to the organization, supervisor, and work group: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior 64: 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, Fred O., Russell Cropanzano, and Barry M. Goldman. 2011. How leader–member exchange influences effective work behaviors: Social exchange and internal–external efficacy perspectives. Personnel Psychology 64: 739–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xingyu, Priyanko Guchait, and Aysin Paşamehmetoğlu. 2020. Why should errors be tolerated? Perceived organizational support, organization-based self-esteem and psychological well-being. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 32: 1987–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, Sandy J., Lynn M. Shore, and Robert C. Liden. 1997. Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Academy of Management Journal 40: 82–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Robert R., and T. Tessa Larson. 2022. Workplace Interpersonal Conflict. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Shi, Larry R. Martinez, Hubert Van Hoof, Michael Tews, Leonardo Torres, and Karina Farfan. 2018. The impact of abusive supervision and co-worker support on hospitality and tourism student employees’ Turnover Intentions in Ecuador. Current issues in Tourism 21: 775–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Juan, Bo Pu, and Zhenzhong Guan. 2019a. Entrepreneurial leadership and turnover intention of employees: The role of Affective Commitment and person-job fit. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Seong Won, Francisco Trincado, Giuseppe Joe Labianca, and Filip Agneessens. 2019b. Negative Ties At work. In Social Networks at Work, 1st ed. Edited by Daniel J. Brass and Stephen P. Borgatt. New York: Routledge, pp. 49–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Zhongjun, Hefu Liu, and Jibao Gu. 2019. Relationships between Conflicts and employee perceived job performance: Job satisfaction as mediator and collectivism as moderator. International Journal of Conflict Management 30: 706–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zickar, Michael J., William K. Balzer, Shahnaz Aziz, and John M. Wryobeck. 2008. The moderating role of social support between role stressors and job attitudes among Roman Catholic priests. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 38: 2903–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Means | SD | α | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Co-worker Support | 4.7 | 0.85 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.49 | 0.701 | |||||

| 2. Supervisor Support | 4.6 | 1.09 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.67 | 0.56 *** | 0.819 | ||||

| 3. Self-efficacy | 4.6 | 0.66 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.44 | 0.32 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.666 | |||

| 4. Conflict | 2.5 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.50 | −0.65 *** | −0.59 *** | −0.19 ** | 0.710 | ||

| 5. Affective Commitment | 4.8 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.57 | 0.55 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.30 *** | −0.32 *** | 0.760 | |

| 6. Turnover Intention | 2.1 | 1.12 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.52 | −0.42 *** | −0.52 *** | −0.26 *** | 0.48 *** | −0.66 *** | 0.72 |

| Indirect Path | Standardized Estimate | Lower | Upper | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-worker Support --> Conflict --> Turnover Intention | −0.131 ** | −0.278 | −0.066 | 0.003 |

| Co-worker Support --> Affective Commitment --> Turnover Intention | −0.133 ** | −0.273 | −0.074 | 0.001 |

| Supervisor Support --> Affective Commitment --> Turnover Intention | −0.178 *** | −0.285 | −0.096 | 0.001 |

| Supervisor Support --> Conflict --> Turnover Intention | −0.076 ** | −0.142 | −0.033 | 0.002 |

| Self-efficacy --> Affective Commitment --> Turnover Intention | −0.068 * | −0.200 | −0.025 | 0.033 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mondo, M.; Pileri, J.; Carta, F.; De Simone, S. Social Support and Self-Efficacy on Turnover Intentions: The Mediating Role of Conflict and Commitment. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100437

Mondo M, Pileri J, Carta F, De Simone S. Social Support and Self-Efficacy on Turnover Intentions: The Mediating Role of Conflict and Commitment. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(10):437. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100437

Chicago/Turabian StyleMondo, Marina, Jessica Pileri, Federica Carta, and Silvia De Simone. 2022. "Social Support and Self-Efficacy on Turnover Intentions: The Mediating Role of Conflict and Commitment" Social Sciences 11, no. 10: 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100437

APA StyleMondo, M., Pileri, J., Carta, F., & De Simone, S. (2022). Social Support and Self-Efficacy on Turnover Intentions: The Mediating Role of Conflict and Commitment. Social Sciences, 11(10), 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100437