1. Introduction

There are many efforts and strategies in place to increase the inclusivity of workplaces, which is a positive approach, but little thought is provided to the personal cost of participants in undertaking some of these initiatives. Often due to the choice of pedagogy, participants may be placed in the situation to reveal hidden parts of their identity which leads to vulnerability and unpredicted exposure in the workplace and organisation. This is known as identity threat (

Clair et al. 2005;

Flett 2012;

Quinn and Chaudoir 2015). Whilst the current social moment towards a more inclusive society is one to be progressed and there is a need to tackle implicit and unconscious bias (

Applebaum and Applebaum 2019) in organisations, workplaces and society, we must however, consider the impact of such training on the individual. The dilemma for individuals is whether they feel they need to reveal (in)visible identities and experience feelings of shame and stigmatisation given their difference or otherness when it is exposed, or do they not reveal and internalize their own self shame and stigmatization for not being able to be themselves (

Fergus et al. 2018)?

This paper will explore critical and progressive pedagogy that is based in both ethnography and critical reflexive theoretical frameworks (

Zagallo et al. 2019) as the key for challenging and changing exclusionary behaviour. The paper focusses on the revelation of hidden or concealed identity whether intentionally or unintentionally through training programs. Such identity threat or exclusionary behaviour also impacts minority individuals in culturally dominated environments, and whilst this is a very important to acknowledge to grow inclusive practice, it is not the focus of this particular paper. In addition, by taking an intersectionality approach and developing skills of empathy, individuals can examine their own positionality and develop more insight as to their cultural and emotional intelligence. It is proposed that using a persona pedagogy, there is less risk of exposure or identity threat, and greater participant engagement. Persona pedagogy involves developing personas with a range of intersecting identities and applying them to oneself with a range of scenarios to make a positive difference to inclusion practices within organisations. Persona pedagogy can be used for protecting one’s identity by minimizing revelation of their personal identity and thus minimizing identity threat.

Intersectionality is a key concept to understanding the unique characteristics of individuals. Intersectionality was a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 to give emphasis to intersecting social identities such as race and gender that led to compounding disadvantage of individuals (

Carastathis 2014;

Cho et al. 2013;

Knapp 2011;

Severs et al. 2016). Intersectionality identified that no longer was it possible to consider individual components of one’s own identity as separate and in isolation from each other, and it focussed on how identities are dynamic and contextual to time, location and context - that is, one could be disadvantageous in one context and advantageous in another (

Bilge 2013;

Bowleg 2012;

Dhamoon 2010;

Haq 2013;

Thomas et al. 2021). As described by Hill Collins and Bilge, intersectionality is an “analytic tool” as well as a “way of understanding and analyzing the complexity in the world, in people, and in human experience” (2016). Intersectionality considers “social inequality, power, relationality, social context, complexity, and social justice” (

Hill Collins and Bilge 2016). Intersectionality is a pivotal concept to progress the broader equity, diversity and inclusion agenda (

Hankivsky et al. 2014).

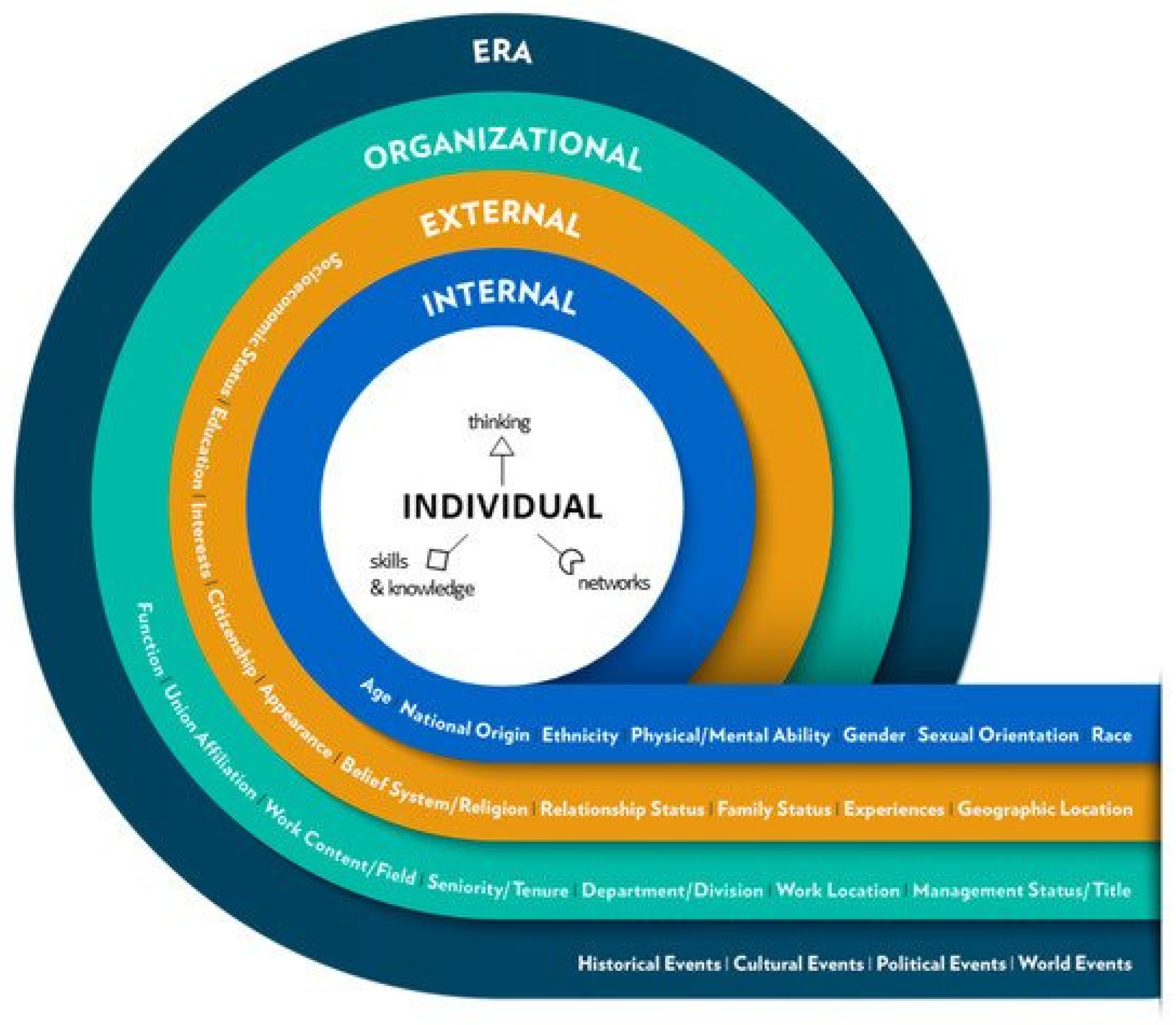

Figure 1 below provides an overview of how an individual is situated in an intersectionality model and presents factors that impact or influence the individual reaching their true capabilities and inclusion.

Personas are defined as “research-based fictional archetypes representing real user needs, experiences, behaviours, and goals. Personas are often used as the other key element of scenarios since the former are the main characters and the driver in the narrative” (

D’Ettole et al. 2020). What this entails is an approach that communicates another’s lived experience in a way that is easily engaged with and understood. A persona methodology or pedagogical approach “by virtue of communicating information through a fictional human character …could evoke empathy” (

Zagallo et al. 2019). In using such an approach, it provides a basis for expanding one’s own world view and becoming more aware of one’s own positionality. A contextualized persona approach is also a way to bring a focus on difference and diversity in professional development, and more broadly the workplace, society and beyond. What this indicates is often due to only experiencing one’s own lived experience or world view, an individual is less aware of how intersecting characteristics and identity impacts others. Taking on a persona through the vehicle of different scenarios, the individual comes to a realization of how systems and structures may play out on individuals with different intersecting identities as compared to their own. Scenarios provide the narrative of how the persona engages in the world in a complex and scaffolded examination of their lived world view (

D’Ettole et al. 2020). With such an approach, transformational learning can occur as it provides participants insight into their user-base, employee base and community. It also enables change agents to more fully consider diversity and intersecting identity without placing individuals at risk of exposing a vulnerability of their own identity. For example, gender policies traditionally focus on the “majority group” of women, however, women as a group are not homogeneous, therefore with such an approach policies can be nuanced toward all women with various intersecting identities to promote true equity. This will be more fully discussed in

Section 3: Persona Pedagogy and Critical Pedagogy.

Quinn and Chaudoir highlight the notions of the various types of concealable stigma (personal and cultural) where different identities may carry a different level (higher) of social exclusion of devaluation (2015), and the impact this can have both psychologically and physically (well-being). A key aspect of this is the consideration of what level of stigma is possibly anticipated or experienced (or perceived and actually felt) by the individual. Further the concept of associative stigma by pure association is explored where a family member may be living with HIV and therefore you are tarnished under the brush due to your association. This is further verified by

Chaudoir and Fisher (

2010), however, the revealing of hidden identity can also be positive if undertaken in an appropriate manner. It can be utilised as a way to increase awareness, knowledge, understanding and education of stigmatized or hidden identities and seen as setting a platform to others to also be more open to reveal aspects of identity. Sharing stories of difference and diversity can contribute to others’ understanding and expansion of their world view. In addition, it can build an environment where individuals feel more comfortable and secure to bring their true authentic self to the workplace. Regardless of the choice of individuals, this information regarding the informed choice to disclose or not can have far reaching consequences and has “both conceptually and applied implications” (

Chaudoir and Fisher 2010) for social change strategies including education and training. The use of personas pedagogy is one strategy to overcome negative impacts and can strengthen educational strategies for inclusion and diversity.

For successful strategic change (such as equity, diversity and inclusion strategies) organisations “must unlearn or discard old routines to make way for new ones…attention should be devoted not only to organisational unlearning but also to individual unlearning as organisational unlearning is often triggered by individual unlearning” (

Matsuo 2018). This implies the importance of not reinforcing traditional ways, views and education for inclusion and diversity in organisations. For not doing so would be reinforcing old patterns, inequalities and privilege, and therefore critical cultural competence has emerged as an approach to sustainable change (

Slayter and Johnson 2021). Matsuo also suggests that “individual unlearning was closely linked to reflective activities, inspired by individual goal orientations” (

Matsuo 2018). Unless placed in an environment of critical reflection, individuals are unable to explore their own positionality and that of others, and unable to learn new ways of thinking and doing.

It is important to highlight the necessity for critical reflection as opposed to reflection. Reflection is just that—to reflect and not instigate further action or change, whereas critical reflection requires action. Many authors have highlighted how critical reflection equates to double loop learning which is more than single loop learning or undertaking corrective action (

Argyris 1991,

2002;

Argyris and Schon 1996;

Matsuo 2018). “Critical reflection can lead to transformative reflection, which refers to the process of effecting change in a frame of reference or in the structure of assumptions through which we understand our experience” (

Matsuo 2018). This coupled with a process of moving an organisation to a learning organisation provides a higher order systemic outcome to change and practice capability (

Argyris 1991,

2004;

Argyris and Schon 1996).

Therefore, if we take the view that to enable successful un-learning and learning in a manner that doesn’t pose a threat to individual identity or vulnerability, the employment of empathy and critical reflection through employing an ethnographic and persona-based approach is key. This paper will examine the key issue of identity threat whilst undertaking diversity, inclusion and intersectional type training. The author offers a solution via the use of persona pedagogy where personas (used in conjunction with scenarios) expand one’s own world views, limits vulnerability exposure, increases inclusion and most importantly minimizes identity threat.

3. Persona Pedagogy and Critical Pedagogy

Personas have been used traditionality in business and informational technology fields to represent a variety of service users to test concepts and products (

Albrechtsen et al. 2016;

AlSabban et al. 2020;

Kelle et al. 2015). Adopting this approach to social justice and social change perspective training activities, a persona pedagogy enables consideration of one’s own positionality, opportunity to expand lived experience, to experience and understand how situations impact individuals differently, builds empathy and most importantly safeguards identity (see

Figure 2 below). “Personas are user representations which are widely employed in user-centred design approaches to establish the interaction designers’ empathy and understanding of the users of the system under consideration…Personas bring more emphasis to the diversity of users and contexts of use but are less detailed in their description of the interaction between user and system”. (

Dittmar and Forbrig 2019). Personas are a way of “deconstructing power imbalances” (

O’Keeffe et al. 2021) but also avail a way to represent diversity in a real world scenario.

Personas, coupled with an experiential and transformative learning framework develops an understanding of others through reflection and strategic development for social change by relating to real world scenarios (critical pedagogy (

Damianidou and Phtiaka 2016)). Personas are documented as “applicable to flexible learning in general…personas also provide an effective tool for communicating in general terms about learners” (

Lilley et al. 2012). Personas would have key demographic information but also adequate information for a trainee or learner to be able to take on the persona as their own (see

Table 1 below). “A persona is not just a plain list of requirements; it is a profile of a hypothetical user, which expresses the traits, needs and goals of the target audience… A good persona description puts a cognitive and mental model of the persona’s behaviour into the minds of people” (

Kelle et al. 2015).

One limitation of a persona approach (and living the lived experiences of others) is the potentially a stereotypical view (or assumption) that individuals with similar characteristics face the same barriers, issues and complexities. This needs to be challenged through facilitation using an intersectional approach. It is important to critically reflect and consider how prior learning and knowledge building will lead to different participants interpreting the same persona differently. This is to be expected and is an important learning point for discussion and critical reflection highlighting how one’s own lived experience or positionality impacts on interpretation of another’s lived experience.

Co-designing of personas with key participants of training sessions who have diverse lived experiences is a powerful tool to address any key issues or areas of challenge within an organisation. By co-designing, it is establishing open communication and true engagement with the process and ensures that personas are grounded with the correct context, not stereotypical and are believable for more impact. The positive in the use of personas is the safety of the individual particularly in training purposes (

O’Keeffe et al. 2021). It protects that individual by using de-identified personas rather than not putting oneself in a place of either portraying an alter ego nor placing oneself in a place of vulnerability to either feel the need to disclose or to be criticized by peers and colleagues (

Albrechtsen et al. 2016). Key to successful persona design and implementation is the ability for participants to fully engage with the persona: “…designing personas that are believable as individual human beings is one of the challenges of persona design. To meet this challenge, persona designers need empathy, deep insight into the users and narrative abilities…” (

Albrechtsen et al. 2016). Importantly personas need to be designed for context and for purpose to evoke a deep reflection and an empathy response which is articulated by Damianidou and Phtiaka who suggest “in order to make a better and fairer world, students need to have the ability to understand other people’s feelings and inner experiences, as well as to observe actions and choices from various perspectives. In other words, they need empathy“(2016). This is critical in inclusion and intersectionality based training. To understand difference is to acknowledge the variety of views, opinions, values and practices of others through empathy and being able to see another position. This is articulated by

Damianidou and Phtiaka (

2016) who suggest that empathy is more than taking on another view through a persona, but more fundamentally acknowledging that many alternative points of view indeed exist. This link to empathy is a vital one. Having an ability to form empathy within a situation and being able to engage with others’ lived experiences and world views enables participants to be more open to different ways of working or unlearning existing behaviours and assumptions. In other words, displaying plasticity of thoughts and behaviour to unlearn or modify previously held assumptions, thoughts and behaviours towards others is necessary to take on a more socially-just and inclusive view of the world.

“Empathy is defined as vicariously perceiving the experiences and emptions of another person” (

Gair 2011). Gair goes on to articulate the importance of providing safe and open spaces for emotional thinking in order to consider one’s own life experiences and response to situations and that of other. This is important for both reflective learning and building empathy towards others, however, it is difficult to empathise with someone if you have not experienced what they have (2011), thus the recommendation of a persona approach to experiencing the lived experience of others. Further

Goldstein and Winner (

2012) suggest an alternate pedagogy of acting (which in this context seen as taking on another’s persona) may also increase empathy. Therefore, for the purposes of a simple definition if empathy is the ability “put one’s self in the shoes of another” (

Thomas et al. 2021;

Zembylas 2018) it can be applied through personas to “radically transform people (especially those in positions of social privilege and power), then it may offer an effective “solution” to social ills and constituent a central component of social justice” (

Zembylas 2018). Taking into account a critical theory perspective where a key facet is the challenging and questioning of societal constructs, assumptions and beliefs (

Allan et al. 2009;

Pease et al. 2016), reflective practice and empathy is vital to enabling change in a manner that does not expose individuals to further risk and vulnerability.

In aligning realistic personas that encompass a range of diversity with scenarios, a story or a lived-experience of that persona emerges which is powerful in training for inclusion and intersectionality (see

Figure 3 below). “Scenario based personas introduce individuals to personal stories that are outside their own experience” (

AlSabban et al. 2020). This facilitates further deep and critical reflection against one’s own positionality to considered another’s lived-experience. The use of narrative and discourse in the design of the personas and scenarios is critical for engaging the participant and putting aside their own beliefs and assumptions while engaging with their allocated persona. However, all of these things must come together. Tailored personas that are relevant for the context of training, with evidence-informed reasoning as to why the training is taking place, and with critical reflection that will lead to transformational social change. In essence this is focusing on a learner centred/active learning approach (

Zagallo et al. 2019). By taking this approach (and considered an ethnographic approach (

AlSabban et al. 2020;

Curren-Preis 2017;

Goldstein and Winner 2012), it is problem based and promotes critical reflection. As stated by

Burrows et al. (

2015) “by presenting their personas and discussing their thoughts with the other groups, participants became aware of the complexity and sometimes conflicting user profiles”. This key observation reflects back to the concept of intersectionality and at times the conflicting or vulnerability of individuals which needs to be considered in inclusion training.

Persona pedagogy is part of experiential learning which “involves trainees personally and affectively examining their own reactions, assumptions, beliefs, attitudes, values, standards of normality, prejudices, stereotypes, biases, privileges, and goals” (

Torino 2015). Role playing or simulation with personas (and critical thinking and reflection) is a useful tool/medium and is an effective teaching method to take on others’ worldviews and expand their own (

Damianidou and Phtiaka 2016). Persona pedagogy evokes transformational learning processes and can be used in any context or learning environment where there is a true engagement with critical reflection and the individual is able to re-evaluate and even modify their existing assumptions “which ultimately leads to personal growth…transformational learning can cultivate improved cognitive ability and emotional awareness through critical reflection, as well as sociocultural and organizational success” (

Boluk and Carnicelli 2015). Transformative learning is seen as conscious raising, a way to change practice and create challenges and discourse for debate and resolution by developing critical thinkers, having developed critical awareness raising and translation into practice (

Christie et al. 2015;

Howie and Bagnall 2013). Critical thinking and reflection coupled with persona pedagogy forms the basis for insightful empathy and understanding to progress inclusion and social change via inclusion and intersectionality training design (

Thomas et al. 2021). Other authors such as

Ogle and Damhorst (

2010) instil the process of critical reflection even further and as the key to transformative learning. They suggest that without a focus on critical reflection an individual would be unable to question, challenge and reframe views or assumptions; adopt an alternative view; apply cultural intelligence and understand impacts of dominant cultures, structures and systems. Once, again this is highlighting a range of factors for transformative learning, with pedagogy and delivery being grounded in empathy and participants having the ability to see others’ points of value, evaluate one’s own views, and modify existing assumptions and views.

4. Reflection on Action—Critical Reflection and Practice

In applying a persona, and critical reflection methodology, a component that is considered fundamental for experiential based learning is the process of debriefing. As outlined by Arafeh, Hansen and Nichols, debriefing in a safe and supportive learning environment allows teams and or individuals to re-examine the learnings just undertaken and “to foster the development of clinical reasoning, critical thinking, judgement skills and communication through reflective learning processes” (2010). It has been reported that the process of debriefing is where the majority of learning occurs and it also assist in the transferability of knowledge gained to other environments (

Arafeh et al. 2010).

Zembylas (

2018) argues that by developing the capability and capacity for self-reflection and empathy, it is a step in right direction to achieve social change. It challenges the colonisation of previously learnt knowledge and practice. Other authors such as Ogle and Damhorst suggest that critical reflection is integral to problem solving for the future and involves not only identifying issues, barriers and problems but in the “making of ethical judgements about what actions might be taken to solve those problems” (

Ogle and Damhorst 2010). This is important when considering the context of work in the realm of intersectionality, diversity and inclusion. Having an approach which places individuals into the lived world of others, and with reflection, assists in developing solutions which do not exclude.

A practical example is the

Supplementary Materials Intersectionality Walk (

Thomas et al. 2020) where participants are encouraged to provide solutions for structural and systemic change after experiencing personas in particular scenarios. By enabling participants to offer solutions, and with the changing of the scenarios based on those solutions in the

Supplementary Materials Intersectionality Walk (or practice), there is a real opportunity for participants to see how they can evoke and achieve meaningful social change (

O’Keeffe et al. 2021) at the micro, meso and macro layers. Reflexivity is normally associated with core professions such as social work and psychology; however, it relates to all fields of activity and business when considering diversity and inclusion. Being able to associate an experience to a personal or human experience or outcome leverages the ability for innovative solution building and change. This is highlighted by

Shaw (

2013) who suggests that “Deep reflexivity can lead to perspective transformation or transformative learning…these terms are about the ability to review ‘meaning structures’ on which judgements are based and are about reframing the reference of internal experience”. This is about challenging all participants and individuals to address cultural and systemic barriers and to rewrite societal constructs and structures. Critical reflection is not at a point in time but an ongoing practice of reflection, deep-thinking and continuous improvement practice and change. This is further highlighted in both the

Theobald et al. (

2017), and the

Whitaker and Reimer (

2017) studies which examined how critical reflection was being used to challenge internal assumptions and impact on a change of behaviour, values and practice to practice in a socially just way.

5. Discussion

The threat to individuals to reveal (or conceal) parts of their identities whilst participating in inclusion and intersectionality type training is real. Facilitators of training need to be cognizant of these issues when developing and undertaking training for not only the short-term risks and impacts of identity exposure (self or others and perceived or real) but also for the longer term impacts of potential stigma and altered working relationships, and comfort in the workplace. This is actually ironic as inclusion and intersectionality training is specifically designed to address such behaviours and to instil a more open and non-excluding workplace, however, if the training is not design with the use of correct and appropriate pedagogy then the training will have detrimental consequences.

Training pedagogy using personas is not only about asking participants to expand their world view but to critically reflect on what they then do with that experience to promote inclusion and change. Personas and scenarios are key to this approach where contextual tailoring of the personas can be undertaken to reflect the issue, behaviour, and the diversity of the contexts being explored. As

Jusinski (

2021) suggests: “In short, from a situated learning perspective, learning occurs through the act of interacting and socializing in real contexts with others who possess varying degrees of expertise and knowledge”. What this highlights is that not only is it effective to have the correct pedagogy of personas (coupled with critical reflection) but also ensuring that that the facilitators themselves are experienced in delivering training in this particular approach. This further emphasises a need to consider the way individuals learn (single versus double loop learning). By placing individuals literally into the shoes of other with a persona journey through contextualized scenarios, it enables critical reflection and change whilst protecting an individual’s identity and vulnerable characteristics. As reported by

Thomas et al. (

2021) in the research undertaken on the delivery of the

Supplementary Materials Intersectionality Walk, there were significant gains self-reported by participants in awareness raising and understanding of others lived experiences through the use of personas and scenarios in the training environment. This coupled with the added protection of reducing potential vulnerability of disclosing (or not) of their own intersecting identities made for an effective pedagogy. By exposing participants to training that is as closely related to a real-work experience as possible, it evokes critical reflection, reflexive practice and builds empathy towards others which instigates lasting social change. “The use of personas provided the opportunity for participants to ‘think’ and ‘be’ outside their normal practice and behaviour, and thus the personas were successful in expanding the individual’s worldview” (

Thomas et al. 2021).

Organisations who are preparing or have delivered inclusion, diversity and intersectionality-based training are being challenged to consider a different approach to the traditional unconscious bias and privilege work structure, for these do put participants and employees at risk. As previously articulated, the situation of protecting the intersecting identities of individuals is fundamental to the process of reducing exclusionary behaviour in the workplace. Once there is an increased understanding of the impact (perceived or real) of discriminatory and exclusionary practice, individuals may feel more comfortable in bringing their authentic self to the workplace. However, the critical point is that staff/participants should never be placed in a position to have their personal intersecting identities intentionally or unintentionally revealed through training experiences. This could be achieved by:

Reviewing all training pedagogy relating to intersectionality, diversity and inclusion

Upskill facilitators in the use of persona and critical reflection pedagogy

Implementing persona and critical reflection pedagogy to all training and replacing training materials that may evoke identity threat

Co-design the training to make the training meaningful for the context of the organisation and staff

Ensure training is undertaken in a neutral and safe environment

Evaluate the training and the impact on cultural change on individuals and the organisation.

Earlier discussion on the stigma of identification of hidden (and often vulnerable) characteristic/s of individuals or a significant person in their life creates undue stress and impacts both physical and psychological health and well-being. In considering how the use of personas are effective in stimulating critical reflection and praxis within the workplace training situation, more training of this type using personas and scenarios should be implemented. Not only does it expand one’s world view, but through the active critical reflection process, participants are able to evaluate and modify their views to enact social change which is fair and socially just. The impact of a persona and scenario approach with critical reflection is that organisations are able to have insight into intersecting disadvantage and privilege that can be addressed on an organisational level. This approach is taking a wholistic view of potential systemic and structural issues within organisations. For example, a woman of colour with a disability has intersections that may traditionally impact on their career trajectory due to existing assumptions about competence (disability), that men make better leaders (gender inequity), and discrimination due to their cultural background. All of this, however, is unfounded. By undertaking persona-based inclusion and intersectionality training, it puts someone who may have never experienced these compounding disadvantages/assumptions into that person’s shoes which is raising their consciousness and awareness of the compounding or cumulative disadvantage. This is a rich and significant experience to expand one’s views of others’ lived experiences and how to be socially just in engaging with all individuals, and making correction to policies, systems and structures. It is also enabling organisation to harness the true talent and capability of employees by breaking down unsubstantiated, exclusionary and stigmatising assumptions that have no foundation. Applying an intersectional lens and persona approaches not only protects from identity threat but “provides a ground-breaking linkage to organisational performance and culture if applied as an educational tool to modify behaviour and thinking” (

Thomas et al. 2021).

Organisations who embrace situated and authentic learning using persona and critical pedagogy approaches are able to build a foundation for individual safety, and cultural and social change. By embracing the intersectional individual and instilling the learning around cultural intelligence, empathy is developed as is personal capability in mitigating exclusionary behaviours. As previously articulated, intellectual quotient and emotional intelligence only permits insight into various social issues, however, it is cultural intelligence that enables empathy, positive change and a successful strategy in managing threat to hidden or vulnerable identity.

Further Research

Ongoing research and scholarship is occurring in this field identifying how persona pedagogy improves social and structural change by linking empathy to personal growth and reflection (

Maduakolam et al. 2020;

O’Keeffe et al. 2021;

Sharratt et al. 2020;

Thomas et al. 2021). However, further research is needed to demonstrate the benefits of using/linking a persona and critical pedagogy approach to inclusion and diversity training and the safeguarding of the individual within the workplace who may have hidden identities or vulnerabilities. This is to consider firstly the long-term effect of increasing the individual’s safety and well-being, and secondly, the positive impact or outcome of inclusion and intersectionality training, and the subsequent inclusive cultural change within organisations.