Cultural Greenspaces: Synthesizing Knowledge and Experience in Nova Scotia’s African-Canadian Communities through Participatory Research and SoftGIS

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What are the most acceptable methods to engagement and participatory research in minority communities which create accurate and meaningful knowledge?

- For the African-Canadian communities around North Preston, Nova Scotia, where are the most visited greenspaces and what benefits are received through interaction?

1.1. Environmental Risk and Vulnerability in the Urbanizing Landscape

1.2. Greenspaces and Human Wellbeing

- Emotional Wellbeing (e.g., happiness, enjoyment, free from stress);

- Physical Wellbeing (e.g., leisure, safety, health, relaxing outdoor activities), and

- Social Wellbeing (e.g., community interaction, support, sense of appreciation).

1.2.1. Psychological Wellbeing

1.2.2. Physical Wellbeing

1.2.3. Social Wellbeing

1.3. Transactional Relationships: A Framework for Studying Human Wellbeing and Greenspace Interaction across Cultures

1.4. Community Engagement and Knowledge Transfer

1.5. Tools for Community Greenspace Knowledge Translation

Measuring Human Wellbeing Transactional Benefits through SoftGIS

- To operationalize strategies for enhancing knowledge acquisition through more inclusive community engagement processes;

- To collect and document concerns and perceptions surrounding land use challenges, policy actions, and environmental racism, including the past, present, and future;

- To provide insight on community members’ behaviors within local greenspaces in order to accurately document and map them, and

- To increase stakeholder communication and interaction in order to enhance planning, policy, and the decision-making processes within local government.

2. Materials and Methods

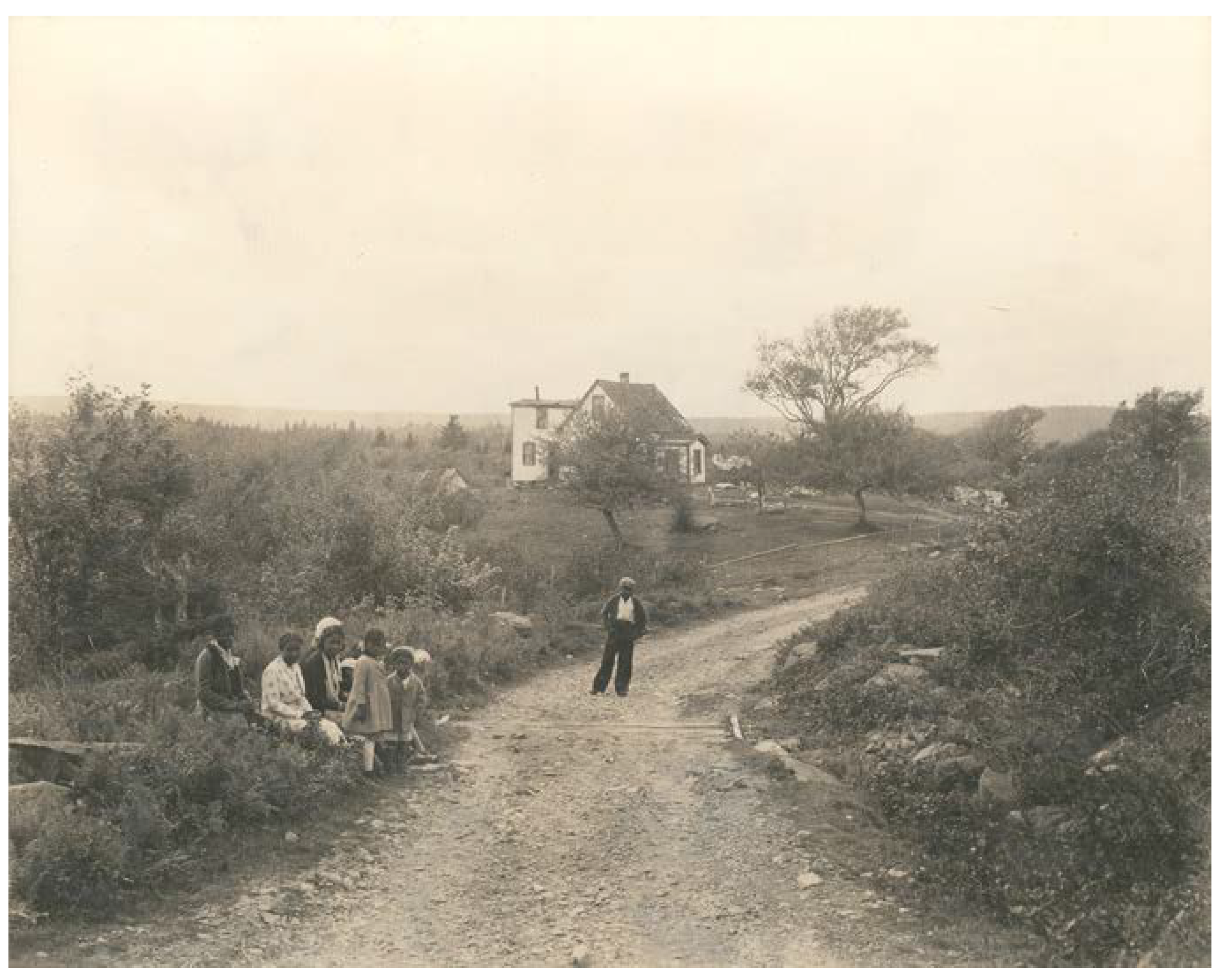

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Community Participation—Landscape Change Historical and Cultural Literature Review

2.4. Community Participation—Cultural Greenspace Geospatial Survey

- Emotional wellbeing (e.g., relaxation, enjoyment, free from stress);

- Physical wellbeing (e.g., leisure, physical activity, outdoor activities), and

- Social wellbeing (e.g., community interaction, support, communication).

3. Results

3.1. Historical and Cultural Literature Review Results

3.2. Geospatial Greenspace Survey Results

3.2.1. Descriptive Analysis Results—Respondent Profiles

3.2.2. Descriptive Analysis Results—Greenspace Interaction Profiles

3.2.3. Geospatial Mapping of Human Wellbeing and Greenspace Interaction

4. Discussion

4.1. The Preston Community and Greenspaces

4.2. Preston Community Empowerment

5. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abucar, Mohamed. 1988. Struggle for Development: The Black Communities of North & East Preston and Cherry Brook, Nova Scotia 1784–1987. Halifax: McCurdy Printing & Typesetting Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, Irwin. 1987. World views in psychology: Trait, interactional, organismic, and transactional perspectives. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology. Edited by Daniel Stokols and Irwin Altman. New York: Wiley, pp. 7–40. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, Erik, Sara Borgström, Dagmar Haase, Johannes Lanemeyer, André Mascarenhas, Timon McPhearson, and Manuel Wolff. 2021. A context-sensitive systems approach for understanding and enablingecosystem service realization in cities. Ecology and Society 26: 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, D., E. Brymer, H. Brito, R. Withagen, and K. Davids. 2019. The empowering variability of affordances of nature: Why do exercisers feel better after performing the same exercise in natural environments than in indoor environments? Psychology of Sport and Exercise 42: 138–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astell-Burt, Thomas, and Xiaoqi Feng. 2019. Association of urban green space with mental health and general health among adults in Australia. JAMA Network Open 2: e198209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atkinson, Paul, and Lisa Morriss. 2017. On ethnographic knowledge. Qualitative Inquiry 23: 323–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, Pratima, Wendy K. Smith, and Eero Vaara. 2018. New ways of seeing through qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal 61: 1189–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baycan-Levent, Tüzin, and Peter Nijkamp. 2009. Planning and management of urban green spaces in Europe: Comparative analysis. Journal of Urban Planning and Development 135: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedimo-Rung, Ariane L., Andrew J. Mowen, and Deborah A. Cohen. 2005. The significance of parks to physical activity and public health: A conceptual model. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 28: 159–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, Simon, Val Hamilton, Alicia Montarzino, Helen Rothnie, Penny Travlou, and Susana Alves. 2008. Greenspace and Quality of Life: A Critical Literature Review. Greenspace Scotland. (1/12 2009). Available online: http://www.greenspacescotland.org.uk/default (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Bogaert, Jan, Angelo Farina, and Reinhart Ceulemans. 2005. Entropy increase of fragmented habitats: A sign of human impact? Ecological Indicators 5: 207–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, L., A. Kothari, C. McCutcheon, and I. D. Graham. 2020. Building an integrated knowledge translation (IKT) evidence base: Colloquium proceedings and research direction. Health Research Policy and Systems 18: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boone, C., G. Buckley, J. Grove, and C. Sister. 2009. Parks and people: A justice inquiry in Baltimore, Maryland. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 99: 767–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, James, and Spencer Banzhaf. 2007. What are ecosystem services? The need for standardized environmental accounting units. Ecological Economics 63: 616–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn, Norman. 1969. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being. Oxford: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Greg. 2012. Public participation GIS (PPGIS) for regional and environmental planning: Reflections on a decade of empirical research. Journal of the Urban & Regional Information Systems Association 24: 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, Bunyan. 1995. Environmental Justice: Issues, Policies, Solutions. Washington, DC: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard, Robert, and Glenn Johnson. 2009. Environmental justice grassroots activism and its impact. In Environmental Sociology: From Analysis to Action. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, Jacquelin. 1996. Focusing on fear: The use of focus groups in a project for the Community Forest Unit, Countryside Commission. Area 28: 130–35. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Jason. 2012. When green is White: The cultural politics of race, nature and social exclusion in a Los Angeles urban national park. Geoforum 43: 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR). 2016. About Us: Knowledge Translation 2016. Available online: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html#2 (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Chen, Shuolei. 2020. Exploring Park Quality in Urban Setting with Environmental Justice, Alternative Measurements, and Social Interaction. Doctoral dissertation, Utah State University, Logan, UT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chiesura, Anna. 2004. The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landscape and Urban Planning 68: 129–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, Suzanne, Vanessa Watts, Alma Knows His Gun McCormick, and Sara Young. 2008. Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. American Journal of Public Health 98: 1398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, Charlotte, and David L. Uzzell. 2006. The socio-environmental affordances of adolescents’ environments. In Children and Their Environments: Learning, Using and Designing Spaces. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 176–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Cline, Hannah, Eric Turkheimer, and Glen E. Duncan. 2015. Access to green space, physical activity and mental health: A twin study. Journal of Epidemiology Community Health 69: 523–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper Marcus, Claire. 2005. Healing havens. Landscape Architecture 95: 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Coppel, Gero, and Henry Wüstemann. 2017. The impact of urban green space on health in Berlin, Germany: Empirical findings and implications for urban planning. Landscape and Urban Planning 167: 410–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, John, and Peter Keller. 2005. An analytical framework to examine empowerment associated with participatory geographic information systems (PGIS). Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 40: 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, Robert, Ralph d’Arge, Rudolf De Groot, Stephen Farber, Monica Grasso, Bruce Hannon, Karin Limburg, Shahid Naeem, Robert V. O’Neill, Jose Paruelo, and et al. 1997. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387: 253–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, Robert, Rudolf De Groot, Paul Sutton, Sander Van der Ploeg, Sharolyn J. Anderson, Ida Kubiszewski, Stephen Farber, and R. Kerry Turner. 2014. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change 26: 152–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czembrowski, Piotr, Edyta Łaszkiewicz, Jakub Kronenberg, Gustav Engström, and Erik Andersson. 2019. Valuing individual characteristics and the multifunctionality of urban green spaces: The integration of sociotope mapping and hedonic pricing. PLoS ONE 14: e0212277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alonzo, Karen Therese. 2010. Getting started in CBPR: Lessons in building community partnerships for new researchers. Nursing Inquiry 17: 282–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dai, Dajun. 2011. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in urban green space accessibility: Where to intervene? Landscape and Urban Planning 102: 234–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, Leith, and Jamie Baxter. 2013. No Opportunity to Say No: A Case Study of Procedural Environmental Injustice in Canada. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 56: 607–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, ed. 2009. Subjective Well-Being. In The Science of Well-Being. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, Paul, Richard Layard, and Robert Metcalfe. 2011. Measuring Subjective Well-Being for Public Policy. CEP Reports 23. London: Centre for Economic Performance, LSE. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Owen, Mick Lennon, and Mark Scott. 2017. Green space benefits for health and well-being: A life-course approach for urban planning, design and management. Cities 66: 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunn, Christine. 2007. Participatory GIS—A people’s GIS? Progress in Human Geography 31: 616–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Urmitapa. 2016. Ethnographic approaches. In Handbook of Methodological Approaches to Community-Based Research. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Este, David. 2007. Black churches in Canada: Vehicles for fostering community development in African-Canadian communities—A historical analysis. In Spirituality and Social Work: Selected Canadian Readings. Toronto: Canadian Scholars, pp. 299–322. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, Peter, and Subhabrata Bobby Banerjee. 2016. When performativity fails: Implications for critical management studies. Human Relations 69: 257–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flicker, Sarah, Beth Savan, Brian Kolenda, and Matto Mildenberger. 2008. A snapshot of community-based research in Canada: Who? What? Why? How? Health Education Research 23: 106–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flicker, S., H. Skinner, S. Read, T. Veinot, A. McClelland, P. Saulnier, and E. Goldberg. 2005. Falling through the cracks of the big cities. Canadian Journal of Public Health 96: 308–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, Paolo. 1970. Cultural action for freedom. Harvard Educational Review 40: 205–225, reprinted in 1998 Harvard Educational Review 68: 476–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryzuk, Lori Anne. 1996. Environmental Justice in Canada: An Empirical Study and Analysis of the Demographics of Dumping in Nova Scotia. Master’s thesis, Environmental Studies, School for Resource and Environmental Studies, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Gasper, Des. 2009. Needs and well-being. In Handbook of Economics and Ethics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- George, Sheba, Nelida Duran, and Keith Norris. 2014. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. American Journal of Public Health 104: e16–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobster, Paul. 2002. Managing urban parks for a racially and ethnically diverse clientele. Leisure Sciences 24: 143–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, Paul H., Joan I. Nassauer, Terry C. Daniel, and Gary Fry. 2007. The shared landscape: What does aesthetics have to do with ecology. Landscape Ecology 22: 959–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, Edwin, Joshua W. R. Baur, Eddie Hill, and Svetoslav Georgiev. 2015. Urban parks and psychological sense of community. Journal of Leisure Research 47: 388–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafius, Darren, Ron Corstanje, and Jim Harris. 2018. Linking ecosystem services, urban form and green space configuration using multivariate landscape metric analysis. Landscape Ecology 33: 557–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graves, Joseph L., Jr., Maureen Kearney, Gilda Barabino, and Shirley Malcom. 2022. Inequality in science and the case for a new agenda. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119: e2117831119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, Karen, Shalini A. Tendulkar, Catlin Rideout, Nazmim Bhuiya, Chau Trinh-Shevrin, Clara P. Savage, Milagro Grullon, Hal Strelnick, Carolyn Leung, and Ann DiGirolamo. 2012. Community capacity building and sustainability: Outcomes of community-based participatory research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action 6: 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haddaway, Neal, Christian Kohl, Rebelo da Silva, Joachim Schiemann, Armin Spök, Ruth Stewart, Jeremy Sweet, and Ralf Wilhelm. 2017. A framework for stakeholder engagement during systematic reviews and maps in environmental management. Environmental Evidence 6: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halifax Municipal Government. 2021. Available online: https://www.halifax.ca/index.php/about-halifax/diversity-inclusion/african-nova-scotian-affairs/african-nova-scotian-community (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Hansen, Rieke, and Stephan Pauleit. 2014. From multifunctionality to multiple ecosystem services? A conceptual framework for multifunctionality in green infrastructure planning for urban areas. Ambio 43: 516–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrington, Christina, Sheena Erete, and Anne Marie Piper. 2019. Deconstructing community-based collaborative design: Towards more equitable participatory design engagements. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 3: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hartig, Terry. 2004. Restorative environments. In Encyclopedia of Applied Psychology. Edited by Chris Spielberger. San Diego: Academic, vol. 3, pp. 273–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heft, Harry. 2001. Ecological Psychology in Context: James Gibson, Roger Barker, and the Legacy of William James’s Radical Empiricism. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Heft, Harry. 2010. Affordances and the perception of landscape. In Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape And Health. London: Routledge, pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, Seulkee, and Michelle L. Bell. 2019. The influence of green space on the short-term effects of particulate matter on hospitalization in the US for 2000–2013. Environmental Research 174: 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heynen, Nik, Harold A. Perkins, and Parama Roy. 2006. The political ecology of uneven urban green space: The impact of political economy on race and ethnicity in producing environmental inequality in Milwaukee. Urban Affairs Review 42: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, Karen Darcell. 2003. A Question of Environmental Racism in the Preston Area, Nova Scotia. Ottawa: National Library of Canada, Bibliothèque nationale du Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, Ruth, Anne Cleary, Claire Cleland, and Matthias Braubach. 2017. Urban Green Space Interventions and Health: A Review of Impacts and Effectiveness. Belfast: Queens University. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, Barbara, Amy J. Schulz, Edith A. Parker, and Adam B. Becker. 1998. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health 19: 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jagosh, Justin, Paula L. Bush, Jon Salsberg, Ann C. Macaulay, Trish Greenhalgh, Geoff Wong, Margaret Cargo, Lawrence W. Green, Carol P. Herbert, and Pierre Pluye. 2015. A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: Partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health 15: 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jankowski, Piotr, Michał Czepkiewicz, Marek Młodkowski, and Zbigniew Zwoliński. 2016. Geo-questionnaire: A Method and Tool for Public Preference Elicitation in Land Use Planning. Transactions in GIS 20: 903–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenerette, G. Darrel, Sharon L. Harlan, William L. Stefanov, and Chris A. Martin. 2011. Ecosystem Services and Urban Heat Riskscape Moderation: Water, Green Spaces, and Social Inequality in Phoenix, USA. Ecological Applications 21: 2637–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, Viniece, and Omoshalewa Bamkole. 2019. The relationship between social cohesion and urban green space: An avenue for health promotion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joassart-Marcelli, Pascale, Jennifer Wolch, and Zia Salim. 2011. Building the healthy city: The role of nonprofits in creating active urban parks. Urban Geography 32: 682–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, Nadja, Niki Frantzeskaki, and Rieke Hansen. 2022. Principles for urban nature-based solutions. Ambio 51: 1388–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahila, Maarit, and Marketta Kyttä. 2006. The use of web-based SoftGIS-method in the urban planning practices. In Proceedings of the Conference on Urban Conditions and Life Changes. Espoo: Helsinki University of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Rachel, and Stephen Kaplan. 2011. Well-being, reasonableness, and the natural environment. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 3: 304–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kapucu, Naim. 2016. Community-based research in generating usable knowledge for public policy and administration. Administration & Society 48: 683–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, Kenneth. 2001. International quality of life: Current conceptual, measurement, and implementation issues. International Review of Research in Mental Retardation 24: 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kimber, Stephen. 1981. Must Preston Die? Available online: http://thedeepmag.ca/mustprestondie/ (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Kivel, Dana, Corey W. Johnson, and Sheila Scraton. 2009. (Re)theorizing leisure, experience and race. Journal of Leisure Research 41: 473–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Michelle C., Jaime M. Fluehr, Thomas McKeon, and Charles C. Branas. 2018. Urban green space and its impact on human health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15: 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korpela, Kalevi, Katja Borodulin, Marjo Neuvonen, Olavi Paronen, and Liisa Tyrväinen. 2014. Analyzing the mediators between nature-based outdoor recreation and emotional well-being. Journal of Environmental Psychology 37: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreindler, Sara. 2018. Advancing the evaluation of integrated knowledge translation. Health Research Policy and Systems 16: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, Byoung-Suk, William C. Sullivan, and Angela R. Wiley. 1998. Green common spaces and the social integration of inner-city older adults. Environment and Behavior 30: 832–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, Marketta. 2002. Affordances of children’s environments in the context of cities, small towns, suburbs and rural villages in Finland and Belarus. Journal of Environmental Psychology 22: 109–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowycz, Kate, and Andy Jones. 2013. Towards a better understanding of the relationship between greenspace and health: Development of a theoretical framework. Landscape and Urban Planning 118: 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, Lincoln, and Aaron Hipp. 2022. Nature-based pathways to health promotion: The value of parks and greenspace. North Carolina Medical Journal 83: 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavis, John, Jonathan Lomas, Maimunah Hamid, and Nelson Sewankambo. 2006. Assessing provincial or national efforts to link research to action acknowledgments. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 84: 620–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leavell, M. A., J. A. Leiferman, M. Gascon, F. Braddick, J. C. Gonzalez, and J. S. Litt. 2019. Nature-based social prescribing in urban settings to improve social connectedness and mental well-being: A review. Current Environmental Health Reports 6: 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- leBrasseur, Richard. 2018. Transitional Landscapes: Examining Landscape Fragmentation within peri Urban Green Spaces and Its Impacts upon Human Wellbeing. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1842/31257 (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Lechner, Frank. 1991. Simmel on social space. Theory, Culture & Society 8: 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, Lois. 2004. Green Space Acquisition and Stewardship in Canada’s Urban Municipalities. Evergreen. Available online: http://www.evergreen.ca/downloads/pdfs/Green-Space-Canada-Survey.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Linneberg, Mai Skjott, and Steffen Korsgaard. 2019. Coding qualitative data: A synthesis guiding the novice. Qualitative Research Journal 19: 259–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsitz, George. 2007. The racialization of space and the spatialization of race theorizing the hidden architecture of landscape. Landscape Journal 26: 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, Jolanda, Sonja Van Dillen, Robert Verheij, and Peter Groenewegen. 2009. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health & Place 15: 586–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rasidi, Mohd Hisyam, Nurzuliza Jamirsah, and Ismail Said. 2010. Urban Green Space Design Affects Urban Residents’ Social Interaction. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 68: 464–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marafa, Lawal M., Felix Tsang, Greg Watts, and Xiao-mei Yuan. 2018. Perceived tranquility in green urban open spaces. World Leisure Journal 60: 221–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, Rodney H., and Rachel Kaplan. 2008. People needs in the urban landscape: Analysis of landscape and urban planning contributions. Landscape and Urban Planning 84: 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maund, Phoebe R., Katherine N. Irvine, Martin Dallimer, Robert Fish, Gail E. Austen, and Zoe G. Davies. 2020. Do ecosystem service frameworks represent people’s values? Ecosystem Services 46: 101221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, Rachel. 2017. Does access to green space impact the mental well-being of children: A systematic review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 37: 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGillivray, Mark, and Matthew Clarke, eds. 2006. Understanding Human Well-Being. Tokyo: United Nations University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McKittrick, Katherine. 2011. On plantations, prisons, and a black sense of place. Social & Cultural Geography 12: 947–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalos, Alex, Andrew Sharpe, and Nazeem Muhajarine. 2010. An Approach to the Canadian Index of Wellbeing. Toronto: Atkinson Charitable Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Millenium Ecosystems Assessment (MEA). 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Wetlands and Water. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler, Meredith, and Nina Wallerstein, eds. 2011. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Mosavel, Maghboeba, Christian Simon, Debbie Van Stade, and Mara Buchbinder. 2005. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) in South Africa: Engaging multiple constituents to shape the research question. Social Science & Medicine 61: 2577–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nelson, Jennifer. 2001. The Operation of Whiteness and Forgetting in Africville: A Geography of Racism. Doctoral thesis, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Tram, Ian D. Graham, Kelly J. Mrklas, Sarah Bowen, Margaret Cargo, Carole A. Estabrooks, Anita Kothari, John Lavis, Ann C. Macaulay, Martha MacLeod, and et al. 2020. How does integrated knowledge translation (IKT) compare to other collaborative research approaches to generating and translating knowledge? Learning from experts in the field. Health Research Policy and Systems 18: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewöhner, Jörg. 2016. Co-Laborative Anthropology: Crafting Reflexivities Experimentally. Analysis and Interpretation. Helsinki: Ethnos, pp. 81–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ord, Katherine, Richard Mitchell, and Jamie Pearce. 2013. Is level of neighbourhood green space associated with physical activity in green space? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 10: 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, Bum-Jin, Katsunori Furuya, Tamami Kasetani, Norimasa Takayama, Takahide Kagawa, and Yoshifumi Miyazak. 2011. Relationship between psychological responses and physical environments in forest settings. Landscape and Urban Planning 102: 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Karin, Birgit Elands, and Arjen Buijs. 2010. Social interactions in urban parks: Stimulating social cohesion? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 9: 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poortinga, Wouter. 2006. Social relations or social capital? Individual and community health effects of bonding social capital. Social Science & Medicine 63: 255–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, LeQuita Carol Hopgood. 2017. Empowerment: Equipping in Empowering Leadership Practices for Transformation in the East Preston United Baptist Church of Nova Scotia. Doctoral dissertation, Acadia University, Wolfville, NS, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Potvin, Louise, Margaret Cargo, Alex M. McComber, Treena Delormier, and Ann C. Macaulay. 2003. Implementing participatory intervention and research in communities: Lessons from the Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project in Canada. Social Science & Medicine 56: 1295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, Stephen M., and Lana Mahgoub. 2016. Ethnic and racial disparities in education: Psychology’s role in understanding and reducing disparities. Theory Into Practice 55: 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K. M. Atikur, and Dunfu Zhang. 2018. Analyzing the level of accessibility of public urban green spaces to different socially vulnerable groups of people. Sustainability 10: 3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rantanen, Heli, and Maarit Kahila. 2009. The SoftGIS approach to local knowledge. Journal of Environmental Management 90: 1981–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reklaitiene, Regina, Regina Grazuleviciene, Audrius Dedele, Dalia Virviciute, Jone Vensloviene, Abdonas Tamosiunas, and Migle Baceviciene. 2014. The relationship of green space, depressive symptoms and perceived general health in urban population. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 42: 669–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roseland, Mark. 2000. Sustainable community development: Integrating environmental, economic, and social objectives. Progress in Planning 54: 73–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, Ismail, and Mohd Sarofil Abu Bakar. 2005. Landscape for children to play and learn: A conceptual comparison between natural stream and playground. Jurnal Teknologi, 10. Available online: http://dms.library.utm.my:8080/vital/access/manage (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Saney, Isaac. 1998. Canada: The black Nova Scotian odyssey: A chronology. Race & Class 40: 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schertz, Kathryn E., James Saxon, Carlos Cardenas-Iniguez, Luís Bettencourt, Yi Ding, Henry Hoffmann, and Marc G. Berman. 2021. Neighborhood street activity and greenspace usage uniquely contribute to predicting crime. NPJ Urban Sustainability 19: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, Kirsten, Michail Fragkias, Christopher G. Boone, Weiqi Zhou, Melissa McHale, J. Morgan Grove, and Jarlath O’Neil-Dunne. 2015. Trees grow on money: Urban tree canopy cover and environmental justice. PLoS ONE 10: e0122051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sehatzadeh, Adrienne Lucas. 2008. A retrospective on the strengths of African Nova Scotian communities: Closing ranks to survive. Journal of Black Studies 38: 407–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, Angela. 2014. This Land is Our Land: African Nova Scotian Voices from the Preston Area Speak Up. Available online: https://nsbs.org/sites/def (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Smith, Lisa M., Jason L. Case, Heather M. Smith, Linda C. Harwell, and J. K. Summers. 2013. Relating ecoystem services to domains of human well-being: Foundation for a US index. Ecological Indicators 28: 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. 2011. Census of Population. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/index-eng.cfm (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Statistics Canada. 2016. Data Products. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/index-eng.cfm (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Statistics Canada. 2022. Population Estimates. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220622/dq220622d-eng.htm (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Stodolska, Monika, Kimberly J. Shinew, Juan Carlos Acevedo, and Dina Izenstark. 2011. Perceptions of urban parks as havens and contested terrains by Mexican-Americans in Chicago neighborhoods. Leisure Sciences 33: 103–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, Takemi, Eva Leslie, Billie Giles-Corti, and Neville Owen. 2008. Associations of neighbourhood greenness with physical and mental health: Do walking, social coherence and local social interaction explain the relationships? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 62: e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sullivan, William C., Frances E. Kuo, and Stephen F. Depooter. 2005. The fruit of urban nature–vital neighborhood spaces. Environment and Behavior 36: 678–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Yi, Paige Sheridan, Olivier Laurent, Jia Li, David A. Sacks, Heidi Fischer, and Yang Qiu. 2020. Associations between green space and preterm birth: Windows of susceptibility and interaction with air pollution. Environment International 142: 105804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teelucksingh, Cheryl, and Jeffery R. Masuda. 2014. Urban environmental justice through the camera: Understanding the politics of space and the right to the city. Local Environment 19: 300–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Trust for Public Land (TPL). 2020. The Heat Is On. Available online: https://www.tpl.org/sites/default/files/The-Heat-is-on_A-Trust-for-Public-Land_special-report.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Thomas, Patricia. 2011. Trajectories of social engagement and limitations in late life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 52: 430–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triguero-Mas, Margarita, Payam Dadvand, Marta Cirach, David Martínez, Antonia Medina, Anna Mompart, Xavier Basagaña, Regina Gražulevičienė, and Mark J. Nieuwenhuijsen. 2015. Natural outdoor environments and mental and physical health: Relationships and mechanisms. Environment International 77: 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tulloch, David. 2008. Is VGI participation? From vernal pools to video games. GeoJournal 72: 161–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turin, Tanvir Chowdhury, Nashit Chowdhury, Sarika Haque, Nahid Rumana, Nafiza Rahman, and Mohammad A. A. Laske. 2021. Meaningful and deep community engagement efforts for pragmatic research and beyond: Engaging with an immigrant/racialised community on equitable access to care. BMJ Global Health 6: e006370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, Liisa, Kirsi Mäkinen, and Jasper Schipperijn. 2007. Tools for mapping social values of urban woodlands and other green areas. Landscape and Urban Planning 79: 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, Liisa, Stephan Pauleit, Klaus Seeland, and Sjerp de Vries. 2005. Benefits and uses of urban forests and trees. In Urban Forests and Trees. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 81–114. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2004. Yamato Declaration on Integrated Approaches for Safeguarding Tangible and Intangible Heritage. Paper presented at International Conference on the Safeguarding of Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage: Towards an Integrated Approach, Nara, Japan, October 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Sandoval, Cecilia, David N. Flanders, and Robert A. Kozak. 2010. Participatory landscape planning and sustainable community development: Methodological observations from a case study in rural Mexico. Landscape and Urban Planning 94: 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, Andrew H., and Paul E. Johnson. 2006. Knowledge for theory and practice. Academy of Management Review 31: 802–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herzele, Ann, and Cees van Woerkum. 2011. On the argumentative work of map-based visualisation. Landscape and Urban Planning 100: 396–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herzele, Ann, and Sjerp De Vries. 2012. Linking green space to health: A comparative study of two urban neighbourhoods in Ghent, Belgium. Population and Environment 34: 171–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Maanen, John. 2011. Ethnography as work: Some rules of engagement. Journal of Management Studies 48: 218–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vårheim, Andreas. 2017. Public Libraries, Community Resilience, and Social Capital. Paper presented at Ninth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Uppsala, Sweden, June 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, Katherine B., Andrew T. Kaczynski, Sonja A. Wilhelm Stanis, Gina M. Besenyi, Ryan Bergstrom, and Katie M. Heinrich. 2013. Exploring the distribution of park availability, features, and quality across Kansas City, Missouri by income and race/ethnicity: An environmental justice investigation. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 45: S28–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waldron, Ingrid. 2016. Experiences of Environmental Health Inequities in African Nova Scotian Communities. Nova Scotia: The ENRICH Project, Dalhousie University. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, Ingrid. 2015. Findings from a series of workshops entitled “In Whose Backyard?—Exploring Toxic Legacies in Mi’kmaw & African Nova Scotian Communities”. Environmental Justice 8: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, I Ingrid. 2018. There’s Something in the Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous and Black Communities. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, Nina, and Bonnie Duran. 2006. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice 7: 312–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward Thompson, Catharine, Peter Aspinall, Jenny Roe, Lynette Robertson, and David Miller. 2016. Mitigating stress and supporting health in deprived urban communities: The importance of green space and the social environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13: 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward-Thompson, Catharine, and Penny Travlou. 2009. A Critical Review of Research in Landscape and Woodland Perceptions, Aesthetics, Affordances and Experience. Prepared for the Forestry Commission: The Research Centre for Inclusive Access to Outdoor Environments. Available online: https://www.openspace.eca.ed.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/A-Critical-Review-of-Research-in-Landscape-and-Woodland-Perceptions-Aesthetics-Affordances-and-Experience.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Wen, Ming, Xingyou Zhang, Carmen D. Harris, James B. Holt, and Janet B. Croft. 2013. Spatial Disparities in the Distribution of Parks and Green Spaces in the USA. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 45: S18–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whitfield, Harvey. 2008. Reviewing Blackness in Atlantic Canada and the African Atlantic Canadian Diaspora. Acadiensis 37: 130–39. Available online: https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/Acadiensis/article/view/11154 (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Wikantiyoso, Respati, and Tonny Suhartono. 2018. The role of CSR in the revitalization of urban open space for better sustainable urban development. International Review for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development 6: 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, E. O. 1984. Biophilia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Michael G., John N. Lavis, Robb Travers, and Sean B. Rourke. 2010. Community-based knowledge transfer and exchange: Helping community-based organizations link research to action. Implementation Science 5: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, Jennifer R., Jason Byrne, and Joshua P. Newel. 2014. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landscape and Urban Planning 125: 234–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. 2010. Urban Green Spaces and Health—A Review of Evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

| Goal 1 | To collect and integrate various histories of landscape change and experiences in order to succinctly document cultural perspectives and concerns. |

| Goal 2 | To identify and map existing greenspaces, open spaces, and other undocumented outdoor areas which have been and are currently being used by Preston community members for a variety of purposes, regardless of ownership or designation. |

| Goal 3 | To increase the Preston community’s ability to proactively communicate to regional stakeholders and government agencies in order to affect positive change in current and future regional planning and policy. |

| What Do You Most Often Do at This Greenspace When You Visit? Please Check All That Apply. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Box | Greenspace Interaction Activity | Wellbeing Benefit |

| Play sports and games, playground, fish, ride bike or scooter. | Physical | |

| Sit and relax, read, be peaceful and spiritual, enjoy nature, sit in car. | Psychological | |

| Get together with a group of friends and family, have cookouts. | Social | |

| Walk the dog. | Physical | |

| Bring the baby outside or kids to play. | Social | |

| Socialize with others, hang-out, catch-up or gossip. | Social | |

| Walk, run, snowmobile, or hike. | Physical | |

| View wildlife, visit coastline, or be in quiet natural areas. | Psychological | |

| “The fact of it is that we’re not just separated anymore—we are one community, which is the African Nova Scotian community. So this is exciting because we get to do the work together”—Senior Deacon. |

| “There are so many feelings of shame, anger and mistrust.”—Elder from Cherry Brook. |

| “There is obviously historic systemic racism involving government and rightfully they haven’t had the trust that they need.”—Resident. |

| “I fear that we lose our community—land is all the community has ever had. I feel as though the government will ambush their way into taking over our community land and historical culture.”—Elder from East Preston. |

| “I feel like my community is being attacked—like predators are lying around waiting to gobble up our land.”—Resident. |

| “We managed to put the brakes on Dartmouth’s expansion for a while … but we can’t sit back on our laurels now. Dartmouth is going to keep looking here, and if they think we aren’t doing anything to develop the land ourselves, they’ll come after us again.”—Resident. |

| “Soon our community will be like Beechville, all the houses, stores and undeveloped land will be owned by white people who are not from our community and will not appreciate the struggles of Black people.”—Resident. |

| “We don’t want our littler communities to turn into cities. We don’t want another Colby Village [a nearby suburban subdivision] here. What we want is to keep our identity.”—Resident. |

| “Street names are rarely used, just local phrases like “down the hill”. We come out in full for church and basketball games. The central firehall is the ‘hangout spot’, albeit informal—if you park or go there, someone will often join you”—Resident. |

| “Today, our communities have people with the knowledge to help with some of the issues the community faces; we just have to trust each other. We can be far more powerful together than if we stand alone.”—Elder from North Preston. |

| Gender |

| Female = 62%, Male = 38% |

| Age |

| 16 to 21 = 9% |

| 21 to 30 = 29% |

| 31 to 40 = 18% |

| 41 to 50 = 7% |

| 51 to 60 = 13% |

| 61+ = 24% |

| Child in Household |

| Yes = 32%, No = 68% |

| % of Respondents | # of Respondents | Greenspace Interaction Activity | Wellbeing Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9% | 22 | Play sports and games, playground, fish, ride bike or scooter. | Physical |

| 20% | 50 | Sit and relax, read, be peaceful and spiritual, enjoy nature, sit in car. | Psychological |

| 43% | 108 | Get together with a group of friends and family, have cookouts. | Social |

| 2% | 4 | Walk the dog. | Physical |

| 9% | 24 | Bring the baby outside or kids to play. | Social |

| 6% | 16 | Socialize with others, hang-out, catch-up or gossip. | Social |

| 3% | 10 | Walk, run, snowmobile, or hike. | Physical |

| 8% | 22 | View wildlife, visit coastline, or be in quiet natural areas. | Psychological |

| 29% (n = 74) visited for psychological wellbeing benefits. 58% (n = 156) visited for social wellbeing benefits. 13% (n = 34) visited for physical wellbeing benefits. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

leBrasseur, R. Cultural Greenspaces: Synthesizing Knowledge and Experience in Nova Scotia’s African-Canadian Communities through Participatory Research and SoftGIS. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11070281

leBrasseur R. Cultural Greenspaces: Synthesizing Knowledge and Experience in Nova Scotia’s African-Canadian Communities through Participatory Research and SoftGIS. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(7):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11070281

Chicago/Turabian StyleleBrasseur, Richard. 2022. "Cultural Greenspaces: Synthesizing Knowledge and Experience in Nova Scotia’s African-Canadian Communities through Participatory Research and SoftGIS" Social Sciences 11, no. 7: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11070281