The Gendered Experience of Close to Community Providers during COVID-19 Response in Fragile Settings: A Multi-Country Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Document Review

2.2. Key Informant Interviews

2.3. In-Depth Interviews or Focus Group Discussions with CTC Providers

2.4. Analysis

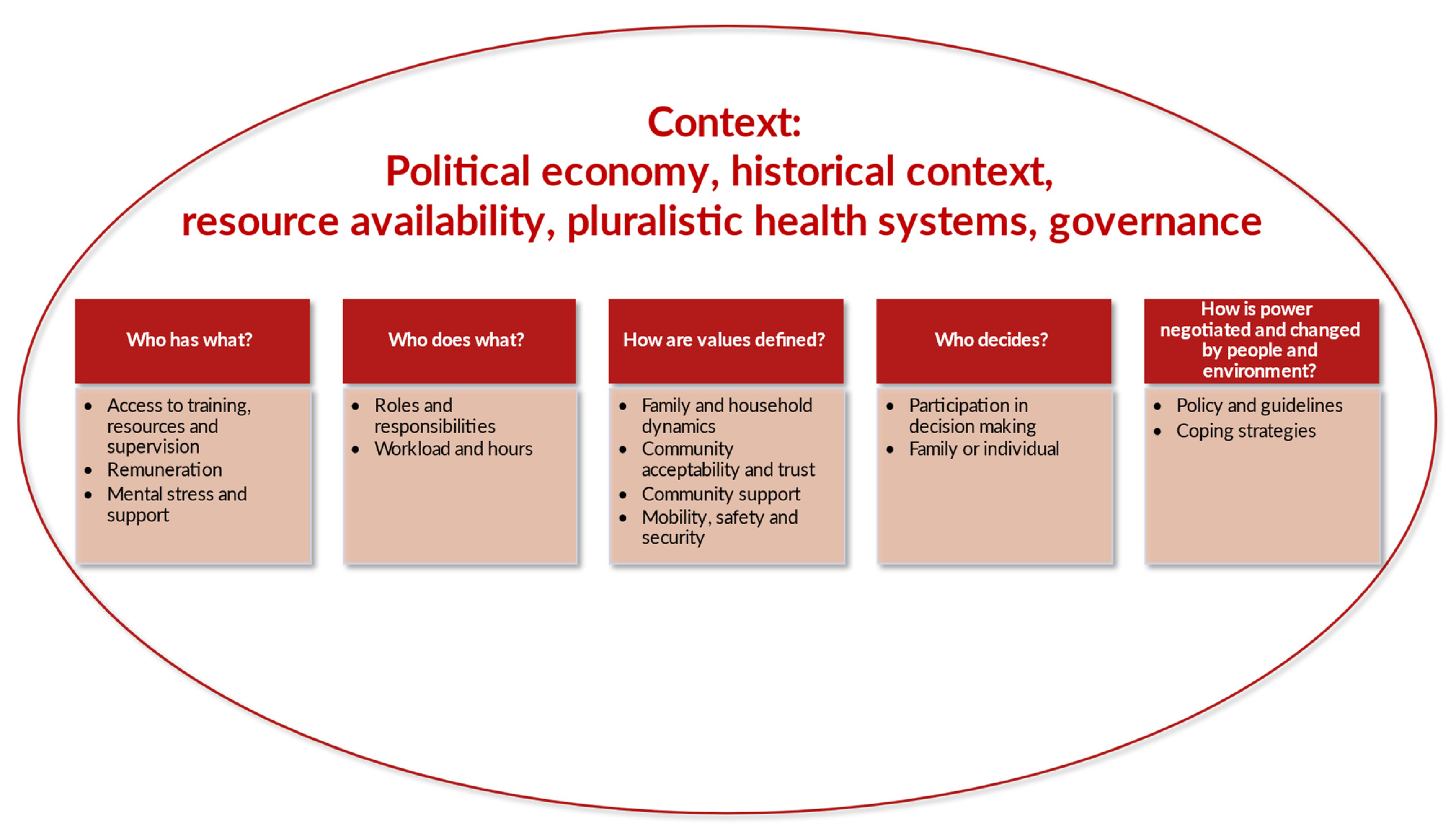

3. Results

3.1. Document Review Findings

3.2. Findings from the KIIs, IDIs and FGDs

3.2.1. Who Has What?

Access to Training, Resources and Supervision

“There was no proper training—our main source of information was Facebook”. CTC provider, woman, Myanmar, IDI

“It was one way communications. When the phone rang, we just had to receive. Then, they would provide all the information about the symptoms. Only when they ask us to guess the right answer, we would guess it. Then they would respond that our answer is correct. That’s all”. CTC provider, woman, Nepal, IDI

“We can hardly secure the PPE for the employees”. Man, Lebanon, KII

“It would be really good if the health department recognizes the community health volunteers and tries to connect and collaborate with them more”. CTC provider, woman, Myanmar, IDI

Remuneration

“The money that they gave us was too small… during a lockdown, we have to buy things in the house to eat. The family burden is too much on us we have our children to look after and other family members”. CTC provider, woman, Sierra Leone, FGD

“It was not easy…especially for us with kids … we were just working in the community and we had nothing … so the little we had is the only thing we were using”. CTC provider, woman, Sierra Leone, FGD

Mental Stress and Support

“We were bashed at in some communities … sometimes we cannot even do our work … as most were claiming that we were disease carriers … coupled with a lot of provocation so that led to serious mental health issues amongst us”. CTC provider, man, Sierra Leone, FGD

“We forwarded several complaints to our superiors … we were admonished to give deaf ears and do the job as we have decided to help our communities … Our superiors also had engagements with community leaders, so that they can take measures as safeguards for responders to do their work effectively”. CTC provider, Man, Sierra Leone, FGD

3.2.2. Who Does What?

Roles and Responsibilities

Workload and Hours

“The workload was much … we have to visit quarantine homes twice a day and talk to them and check their temperature … And in some households, there are many people”. CTC provider, woman, Sierra Leone, FGD

“Need to adjust to have equilibrium between work and family. More sacrifice for women than men as men do not have much responsibility like women”. CTC provider, woman, Myanmar, IDI

“Family comes first: When the children are not going to schools, it exerts pressure on me. I am working outside, and when my children study online, I had to stay with them for hours. My husband is at home due to corona. This also exerts pressure”. CTC provider, woman, Lebanon, IDI

“They gave me a phone call from health post instructing me to deliver kit box to COVID patients and bringing back their health reports. Both works [farm work and duty as CHW] coincided at the same time. There was no one at home. I asked my neighbour to prepare some pickle and snacks for farm worker. I cooked potato and handed it to her. After I reached health post to receive kit box, I called 2, 3 people from my own community and sent them to the field. Then after, I visited to COVID patient’s home”. CTC provider, woman, Nepal, IDI

3.2.3. How Are Values Defined?

Family and Household Dynamics

“My family and friends supported me and they encourage us to do the work … They listen to whatever we tell them to do that alone is a big support, because they are making our work easy”. CTC provider, woman, Sierra Leone, FGD

“The family member scold asking, “Why do you need to do that work?” My own husband scolds me asking, “How much do they pay you? Why do you go there?” I have been used to this type of scolding. I let him continue scolding. I’ll carry on with my work”. CTC provider, woman, Nepal, IDI

Community Acceptability and Trust

“Neighbours and people around me used to tell me “Stay away from us. Don’t come closer. You work with Corona. Maybe you could infect us”.” CTC provider, woman, Lebanon, IDI

“Some of them lock their door. When we rang bell, they used to look at us and go inside fearing whether we might have brought corona. When we told them, “We need to discuss something with you,” only then they came out to their balcony”. CTC provider, woman, Nepal, IDI

“[Community] are assuming that we are also playing a huge part in prolonging the period of the disease in communities…In communities, we are only regarded by old people … while young people are accusing us of monetizing the whole response programme … that creates a kind of stigma around us in our communities” CTC provider, Man, Sierra Leone, FGD

“Communities do not tend to often listen to women in certain situations due to cultural beliefs … they are not given the audience they need…so in some cases we provide them with a male back up if there should be pressing issues to be addressed”. Man, Sierra Leone, KII

“Initially during the first wave some people in the community were frightened to talk to me which eventually reduced in the second wave”. CTC provider, woman, Myanmar, IDI

Community Support

“Tokens of appreciation and thank you cards from the Myanmar Red Cross Society, community and health departments make us feel motivated. I feel like I was supported when I felt very tired. I am happy for that. We work not for money and not expecting we will get something in return. From MRCS, we got hats or t-shirts and some other presents from community as tokens of appreciation”. CTC provider, woman, Myanmar, IDI

“After realizing the intensity of the outbreak, we started getting support from some other local NGOs … materials like thermometers and hand washing materials were provided to us … we distributed those at strategic points that could be easily accessed by people to use”. CTC provider, man, Sierra Leone, FGD

Mobility, Safety and Security

“There is a challenge for girls, and it sometimes needs the family to accompany the girls (volunteers) on their way home from work. Sometimes, we have meetings at night. For me, my husband come and pick me up. For girls, we may need to arrange for their return trip. For example, the township committee arranges a car for girls. For boys, there is no problem as they can manage on their own”. Woman, Myanmar, KII

“Their thinking is like: you are a girl and you are attending camps by yourself. People ask: you have nobody else? And even when we quit the camp and look for a car, we are not viewed positively”. CTC provider, woman, Lebanon, IDI

3.2.4. Who Decides?

Participation in Decision Making

“No, I am not aware of COVID-19 specific group formation in the community, and I don’t know about my membership on it either”. CTC provider, woman, Nepal, IDI

“Yesterday, there was a certain programme led by Ward Officials. I didn’t know about the programme. A Ward member invited me at the last hour. They should’ve timely informed me about the program in the morning or in the afternoon so that I could get time to manage my household chores”. CTC provider, woman, Nepal, IDI

“If they have children but don’t have problem with working as frontline workers within COVID-19, it is their own decision. We did not oblige anyone to participate in the response … We also leave the choice for the person. Also, when we have emergency cases, we need to stay late, the person who wants to leave could leave. We don’t exert any retaliation [penalties]”. Woman, Lebanon, KII

Family or Individual Decision Making

“I was really traumatized due to the pregnancy of my younger sister…life was so stressful for me due to additional burden … I have to take care of both the mother and the child … My job was affected due to stress…no help from anywhere else … I have now got more burden on me with less income”. CTC provider, man, Sierra Leone, FGD

3.2.5. How Is Power Negotiated and Changed by People and Environment?

Policy and Guidelines

“During the training at the council, they gave us posters that we used to sensitize people … telling people about the prevention of COVID-19, they gave us megaphones to do the sensitization”. CTC provider, woman, Sierra Leone, FGD

“We have a protocol to approach patients with maximum levels of protection for ourselves, the patients, and the society”. CTC provider, man, Lebanon, IDI

Coping Strategies

“Every morning, I say to myself, “You … are a strong person. You need to bear the difficulties thrown in your way, and you have to challenge them …” Thanks to God, I have work, even if it is tiring, but not every refugee has the chance to work”. CTC provider, woman, Lebanon, IDI

“I come and talk to my husband. I tell him about my day, and he calms me a bit. Usually, each family member needs to be giving to each other in order to build the family”. CTC provider, Lebanon, IDI

“How long will the 15 masks last for? [Laughs] After that, I have been buying them myself until now. My husband buys them in a packet. Everyone uses them. Mostly, we throw them after returning home. We also wash them and reuse sometimes. How often can we buy then? We get tired of buying them continuously. Moreover, it is said that the cloth masks aren’t appropriate. Hence, I reused them”. CTC provider, woman, Nepal, IDI

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Key Findings

4.2. CTC Providers and Families

4.3. Community

4.4. Health System

- The pandemic trajectory, the magnitude and speed of infection.

- The fragility of the country and how quickly and well the country and health system could respond.

- The resource availability and in particular the ability to provide PPE to health workers including CTC providers, and how this was prioritised.

- The need for multisectoral action in the COVID-19 response, and how to support CTC providers was identified.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akseer, Nadia, Goutham Kandru, Emily C. Keats, and Zulfiqar A. Bhutta. 2020. COVID-19 pandemic and mitigation strategies: Implications for maternal and child health and nutrition. American Journal of Clincial Nutrition 112: 251–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ARISE Hub. 2020. The Responses of ARISE Partners to COVID-19. Available online: http://www.ariseconsortium.org/arise-response-covid-19-interventions-low-income-countries-africa-asia/ (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Aryal, Shreyashi, and Sagun Ballav Pant. 2020. Maternal mental health in Nepal and its prioritization during COVID-19 pandemic: Missing the obvious. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 54: 1002281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayadi, Rym, Sami Abdullah Ali, Nooh Alshyab, Kwame Sarpong Barnieh, Yacine Belarbi, Sandra Challita, Najat El Mekkaoui, Ayed ben Rim Mouelhi, Racha Ramadan, Sara Ronoc, and et al. 2020. COVID-19 in the Mediterranean and Africa Diagnosis, Policy Responses, Preliminary Assessment and Way Forward. Available online: https://euromed-economists.org/download/covid-19-in-the-mediterranean-and-africa-diagnosis-policy-responses-preliminary-assessment-and-way-forward-study/ (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Bhaumik, Soumyadeep, Sandeep Moola, Jyoti Tyagi, Devaki Nambiar, and Misimi Kakoti. 2020. Community health workers for pandemic response: A rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Global Health 5: e002769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caperon, Lizzie, Stella Arakelyan, Cinzia Innocenti, and Alistair Ager. 2021. Identifying opportunities to engage communities with social mobilisation activities to tackle NCDs in El Salvador in the context of the global COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal for Equity in Health 20: 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, Sara, Sarah Chynoweth, Nadine Cornier, Meghan Gallagher, and Erin Wheeler. 2015. Progress and gaps in reproductive health services in three humanitarian settings: Mixed methods case studies. Conflict and Health 9: S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, Priyanshi. 2020. Gendering COVID-19: Impact of the Pandemic on Women’s Burden of Unpaid Work in India. Gender Issues 38: 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, Lyn, and Brendan Churchill. 2020. Working and Caring at Home: Gender Differences in the Effects of Covid-19 on Paid and Unpaid Labor in Australia. Feminist Economics 27: 310–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, Laura, Janice Cooper, Haja Wurie, Karsor Kollie, Joanna Raven, Rachel Tolhurst, Hayley MacGregor, Kate Hawkins, Sally Theobald, and Bintu Mansaray. 2020. Psychological resilience, fragility and the health workforce: Lessons on pandemic preparedness from Liberia and Sierra Leone. BMJ Global Health 5: e002873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, Sharmila. 2020. COVID-19 exacerbates violence against health workers. Lancet 396: 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmond, Karen M., Khaksar Yousufi, Zelaikha Anwari, Sayed Masoud Sadat, Shah Mansoor Staniczai, Ariel Higgins-Steele, Alexandra L. Bellows, and Emily R. Smith. 2018. Can community health worker home visiting improve care-seeking and maternal and newborn care practices in fragile states such as Afghanistan? A population-based intervention study. BMC Medicine 16: 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El Chammay, Rabih, and Bayard Roberts. 2020. Using COVID-19 responses to help strengthen the mental health system in Lebanon. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 12: S281–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMERGE. 2020. COVID-19 and Gender Research in LMICs: July–September 2020 Quarterly Review Report. Available online: https://emerge.ucsd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/covid-19-and-gender-quarterly-report-jul-sep-2020.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- George Institute. 2020. Are We Doing Enough for the Mental Well-Being of Community Health Workers during COVID-19? Available online: https://www.georgeinstitute.org.uk/profiles/are-we-doing-enough-for-the-mental-well-being-of-community-health-workers-during-covid-19 (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Government of Sierra Leone. 2020. Interim Guidance for Community Health Workers (CHW) Program in COVID-19 Context; Freetown: Government of Sierra Leone.

- İlkkaracan, İpek, and Emel Memiş. 2020. Transformations in the Gender Gaps in Paid and Unpaid Work During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings from Turkey. Feminist Economics 27: 288–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Migration. 2020. Rapid Assessment on Impacts of COVID-19 on Returnee Migrants and Responses of the Local Governments of Nepal. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/nepal/rapid-assessment-impacts-covid-19-returnee-migrants-and-responses-local-governments (accessed on 26 February 2022).

- Kanu, Sulaiman, Peter Bai James, Abdulai Jawo Bah, John Alimamy Kabba, Musa Salieu Kamara, Christine Ellen Elleanor Williams, and Joseph Sam Kanu. 2021. Healthcare Workers’ Knowledge, Attitude, Practice and Perceived Health Facility Preparedness Regarding COVID-19 in Sierra Leone. Journal of Multidisciplinary Health 14: 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox-Peebles, Camilla. 2020. Community Health Workers: The First Line of Defence against COVID-19 in Africa. Available online: https://www.bond.org.uk/news/2020/04/community-health-workers-the-first-line-of-defence-against-covid-19-in-africa (accessed on 26 February 2022).

- Kok, Maryse C., Jacqueline E. W. Broerse, Sally Theobald, Hermen Ormel, Marjolein Dieleman, and Miriam Taegtmeyer. 2017. Performance of community health workers: Situating their intermediary position within complex adaptive health systems. Human Resources for Health 15: 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, Isabel, Kristi Mahrt, Catherine Ragasa, Michael Wang, Hnin Win, and Khin Zin Win. 2020. A Gender-Transformative Response to COVID-19 in Myanmar. International Food Policy Research Institute. Available online: https://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/133743/filename/133953.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- LeBan, Karen, Maryse Kok, and Henry Perry. 2021. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 9. CHWs’ relationships with the health system and communities. Health Research Policy and System 19: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotta, Gabriela, Clare Wenham, João Nunes, and Denise Nacif Pimenta. 2020. Community health workers reveal COVID-19 disaster in Brazil. The Lancet 396: 365–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, Wesam, Abriti Arjyal, Chad Hughes, Emma Gbaoh, Fouad Fouad, Haja Wurie, Kyaw Hnin Kalayar, Julie Tartaggia, Kyu Kyu Than, Kallon Lansana Hassim, and et al. 2022. Health systems resilience in fragile and shock-prone settings through the prism of gender equity and justice: Implications for research, policy and practice. Conflict and Health 16: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, Wesam, and Joanna Raven. 2021. The Gendered Experience of Close-to-Community Providers in Fragile and Shock-Prone Settings: Implications for Policy and Practice during and Post COVID-19 Global Document Review. Available online: https://www.rebuildconsortium.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/CTC-study-global-review-report-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Menge, Jonathon, and Samira Paudel. 2020. Under Pressure: Health Care Workers Fighting at the Frontlines in Nepal. Available online: https://asia.fes.de/news/under-pressure-health-care-workers-fighting-at-the-frontlines-in-nepal (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Ministry of Health and Population Nepal. 2019. Annual Report 2075/76 (2018/19); Kathmandu: Government of Nepal.

- Ministry of Health and Population Nepal. 2020. समुदाय स्तरमा कोभिड सहजीकरण समूह परिचालन सम्बन्धि मार्ग निर्देशन; Kathmandu: Government of Nepal.

- Ministry of Health and Sports Myanmar. 2020. Community Based Health Worker Policy. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. Available online: https://chwcentral.org/myanmars-community-based-health-workers/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Ministry of Public Health Lebanon. n.d. COVID-19. Available online: https://www.moph.gov.lb/ar/DynamicPages/index/2/24870/novel-coronavirus-2019- (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Ministry of Public Health Lebanon. 2020. Lebanon Health Resilience Project: Environmental and Social Safeguards Management Framework: Addendum to ESMF for the Inclusion of Component 4: Strengthen Capacity to Respond to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.moph.gov.lb/DynamicPages/download_file/5570 (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Miyake, Sachiko, Elizabeth Speakman, Sheena Currie, and Natasha Howard. 2017. Community midwifery initiatives in fragile and conflict-affected countries: A scoping review of approaches from recruitment to retention. Health Policy and Planning 32: 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Rosemary, Asha George, Sarah Ssali, Kate Hawkins, Sassy Molyneux, and Sally Theobald. 2016. How to do (or not to do) … genderanalysis in health systems research. Health Policy and Planning 31: 1069–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraya, Kai. 2020. Gender and COVID-19 in Africa. The Gender and COVID-19 Working Group. Available online: https://www.genderandcovid-19.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Gender-and-COVID19-in-Africa.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Mutseyekwa, Tapuwa. 2020. Community Health Workers Supporting Community Sensitization and Awareness of COVID-19—Working with Partners to Prevent Deaths and Illness due to COVID-19 in Sierra Leone. Freetown: UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/sierraleone/stories/community-health-workers-supporting-community-sensitization-and-awareness-covid-19 (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Nanda, Priya, Lewis Tom Newton, Priya Das, and Suneeta Krishnan. 2020. From the frontlines to centre stage: Resilience of frontline health workers in the context of COVID-19. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 28: 1837413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, Samata, and Sreyashi Aryal. 2020. COVID-19 And Nepal: A Gender Perspective. Journal of Lumbini Medical College 8: 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Nepomnyashchiy, Lyudmila, Bernice Dahn, Rachel Saykpah, and Mallika Raghavan. 2020. COVID-19: Africa needs unprecedented attention to strengthen community health systems. The Lancet 396: 150–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, James, Rebecca Hamala, Margaret Nalubwama, Mathew Ameniko, Georgia Govina, Nowai Gray, Raj Panjabi, Daniel Palazuelos, and Allan Saul Namanda. 2021. Roles for mHealth to support Community Health Workers addressing COVID-19. Global Health Promotion 28: 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Prime Minister and Council of Ministers. 2020. कोरोना महामारी (COVID-19) रोकथाम तथा नियन्त्रणका लागि समुदायमा स्वयंसेवक परिचालन सम्बन्धि मार्गनिर्देशन २०७६; Kathmandu: Government of Nepal, pp. 1–27.

- Oluwole, Akinola, Laura Dean, Luret Lar, Kabiru Salami, Okefu Okoko, Sunday Isiyaku, Ruth Dixon, Elizabeth Elhassan, Elena Schmidt, Rachael Thomson, and et al. 2019. Optimising the performance of frontline implementers engaged in the NTD programme in Nigeria: Lessons for strengthening community health systems for universal health coverage. Human Resources for Health 17: 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orya, Evelyn, Sunday Adaji, Thidar Pyone, Haja Wurie, Nynke van den Broek, and Sally Theobald. 2017. Strengthening close to community provision of maternal health services in fragile settings: An exploration of the changing roles of TBAs in Sierra Leone and Somaliland. BMC Health Services Research 17: 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, Surya B., Sabin Shrestha, Anisha Sah, K. C. Heera, Kapil Amgain, and Prajjwal Pyakurel. 2020. Role of Female Community Health Volunteers for Prevention and Control of COVID-19 in Nepal. Journal of Karnali Academy of Health Sciences 3: 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partners in Health. 2020. Reaching Every Last Home to Prevent COVID-19′s Spread in Sierra Leone: Community Health Workers, Social Mobilizers Key to Education, Referrals, and Care in Pandemic. Available online: https://www.pih.org/article/reaching-every-last-home-prevent-covid-19s-spread-sierra-leone (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Public Services International. 2020. Community Health Work is Work. Available online: https://publicservices.international/campaigns/community-health-work-is-work?id=11393&lang=en&fbclid=IwAR0FkYQigv5ZqXkVD-be-BIqCOh7PNdS3poLVBhVDJ0cZEnWRJic70_2K5k (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Raven, Joanna, Haja Wurie, Amuda Baba, Abdulai Jawo Bah, Laura Dean, Kate Hawkins, Ayesha Idriss, Karsor Kollie, Gartee Nallo, Rosie Steege, and et al. 2022. Supporting community health workers in fragile settings from a gender perspective: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 12: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, Joanna, Haja Wurie, Ayesha Idriss, Abdulai Jawo Bah, Amuda Baba, Gartee Nallo, Karsor K. Kollie, Laura Dean, Rosie Steege, Tim Martineau, and et al. 2020. How should community health workers in fragile contexts be supported: Qualitative evidence from Sierra Leone, Liberia and Democratic Republic of Congo. Human Resources for Health 18: 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, Joanna, Patricia Akweongo, Amuda Baba, Sebastian Olikira Baine, Mohamadou Guelaye Sall, Stephen Buzuzi, and Tim Martineau. 2015. Using a human resource management approach to support community health workers: Experiences from five African countries. Human Resources for Health 13: 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REACHOUT. n.d. Definition of Close to Community Provider. Available online: http://www.reachoutconsortium.org/approach/reachout-definitions/ (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- ReBUILD for Resilience Consortium. 2021. The Gendered Experience of Close-to-Community Providers in Fragile and Shock-Prone Settings Implications for Policy and Practice during and Post COVID-19—A Qualitative Study Report Sierra Leone. Available online: https://www.rebuildconsortium.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/CTC-Study-Final-Report_Sierra-Leone.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Ritchie, Jane, Liz Spencer, and William O’Connor. 2003. Carrying out qualitative analysis. In Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers, 1st ed. Edited by Ritchie Jane and Lewis Jane. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 219–62. [Google Scholar]

- Snape, Dawn, and Liz Spencer. 2003. The foundations of qualitative research. In Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers, 1st ed. Edited by Ritchie Jane and Lewis Jane. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, Shuchi, and Radhika Arora. 2020. Rapid Literature Review: Community Health Workers. COVID-19 Series. 2020. Available online: https://chwcentral.org/resources/rapid-literature-review-community-health-workers/ (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Ssali, Sarah. 2020. Gender, Economic Precarity and Uganda Government’s COVID-19 Response. African Journal of Governance & Development 9: 287–308. [Google Scholar]

- Steege, Rosalind, Miriam Taegtmeyer, Rosalind McCollum, Kate Hawkins, Hermen Ormel, Maryse Kok, Sabina Rashid, Mohsin Sidat, Kingsley Chikaphipha, Daniel Datiko, and et al. 2018. How do gender relations affect the working lives of close to community health service providers? Empirical research, a review and conceptual framework. Social Science and Medicine 209: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. 2020. UNHCR’S Support to Lebanon’s COVID-19 Response. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/lb/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2020/11/UNHCR-Covid-Response-Report_EN_October2020.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- UNICEF, Save the Children, and International Rescue Committee. 2020. Community Health Workers in Humanitarian Settings. Policy Brief. Available online: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/18294/pdf/chws_in_humanitarian_settings_policy_brief_final_25aug2020.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- United Nations Foundation. 2020. Women in Nepal Saving Lives—One Kitchen at a Time [Internet]. Available online: https://unfoundation.org/blog/post/women-in-nepal-saving-lives-one-kitchen-at-a-time/?fbclid=IwAR3R0ao4XuPRJ3ivmSt29oFSpfO3GLMc6YZM9HrAp0vR1-TlUf400rSG1AU (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Wenham, Clare, Julia Smith, Rosemary Morgan, and Gender and COVID-19 Working Group. 2020. COVID-19: The gendered impacts of the outbreak. The Lancet 395: 846–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. 2016. Global Strategy on Human Resources for health: Workforce 2030. World Health Organisation. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250368/9789241511131-eng.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- WHO. 2022. WHO Coronavirus Dasboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- WHO EMRO. 2020. Primary Health Care Centers Engage in the Fight against COVID-19. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/ar/pdf/lbn/lebanon-news/primary-health-care-centers-engage-in-the-fight-against-covid-19.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- World Health Organization. 2020. Health Workforce Policy and Management in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic Response: Interim Guidance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/health-workforce-policy-and-management-in-the-context-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-response (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Yakubu, Kenneth, David Musoke, Kingsley Chikaphupha, Alyssa Chase-Vilchez, Pallab K. Maulik, and Rohina Joshi. 2022. An intervention package for supporting the mental well-being of community health workers in low, and middle-income countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Comprehensive Psychiatry 115: 152300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamout, Rouham, and Joanna Khalil. 2021. The Gendered Experience of Close-to-Community Providers in Fragile and Shock-Prone Settings during the COVID-19 Pandemic. American University of Beirut. REBUILD for Resilience Consortium. Available online: https://www.rebuildconsortium.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/CTC-gender-study-brief.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lebanon | 3 managers of facilities (3M) | 3 managers of organisations providing outreach (3F) | 6 (3F;3M) |

| Myanmar | 2 township supervisors (1M; 1F) | Not applicable | 2 (1F;1M) |

| Nepal | 1 Sub-health coordinator (COVID-focal person) (M) 1 Ward chair (F) 1 Mayor (M) 1 Health Post In-charge (M) | 1 Health Post In-charge (F) 1 Health Post In-charge (M) 1 Health Coordinator (M) 1 Mayor (M) 1 Public Health Inspector (COVID focal person) (M) | 9 (2F; 7M) |

| Sierra Leone | 1 District health Management Team member (M) 1 CTC Peer Supervisor (M) 1 Section Chief (M) 1 Mammy Queen (Chairlady) (F) | 1 District health Management Team member (M) 1 CTC Peer Supervisor (F) 1 Section Chief (M) 1 Mammy Queen (Chairlady) (F) | 8 (3F; 5M) |

| Total | 13 | 12 | 25 (9F;16M) |

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lebanon | 6 CTC providers (4F;2M) | 6 CTC providers (4F;2M) | 12 (8F;4M) |

| Myanmar | 5 CTC providers (4F;1M) | Not applicable | 5 (4F;1M) |

| Nepal | 7 FCHVs | 6 FCHVs | 13 (13F) |

| Sierra Leone | 1 FGD with women CTC providers (8) 1 FGD with men CTC providers (8) | 1 FGD with women CTC providers (8) 1 FGD with men CTC providers (7) | 31 (16F;15M) |

| Total | 34 (23F;11M) | 27 (18F;9M) | 61 (41F;20M) |

| No. Documents Reviewed | Types of Documents | |

|---|---|---|

| Lebanon | 59 |

|

| Myanmar | 7 |

|

| Nepal | 16 |

|

| Sierra Leone | 6 |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raven, J.; Arjyal, A.; Baral, S.; Chand, O.; Hawkins, K.; Kallon, L.; Mansour, W.; Parajuli, A.; Than, K.K.; Wurie, H.; et al. The Gendered Experience of Close to Community Providers during COVID-19 Response in Fragile Settings: A Multi-Country Analysis. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090415

Raven J, Arjyal A, Baral S, Chand O, Hawkins K, Kallon L, Mansour W, Parajuli A, Than KK, Wurie H, et al. The Gendered Experience of Close to Community Providers during COVID-19 Response in Fragile Settings: A Multi-Country Analysis. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(9):415. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090415

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaven, Joanna, Abriti Arjyal, Sushil Baral, Obindra Chand, Kate Hawkins, Lansana Kallon, Wesam Mansour, Ayuska Parajuli, Kyu Kyu Than, Haja Wurie, and et al. 2022. "The Gendered Experience of Close to Community Providers during COVID-19 Response in Fragile Settings: A Multi-Country Analysis" Social Sciences 11, no. 9: 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090415

APA StyleRaven, J., Arjyal, A., Baral, S., Chand, O., Hawkins, K., Kallon, L., Mansour, W., Parajuli, A., Than, K. K., Wurie, H., Yamout, R., & Theobald, S. (2022). The Gendered Experience of Close to Community Providers during COVID-19 Response in Fragile Settings: A Multi-Country Analysis. Social Sciences, 11(9), 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090415