Abstract

Decent Work is considered essential to the facilitation of a transition to greener, fairer, more prosperous, and more just societies. Decent Work represents a fundamental component of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and a crucial facet of European Union (EU) environment, social, and governance (ESG) norms. Despite its prominence, the precise definition and materiality of Decent Work is obscure and remains subject to limited consensus. To understand these critical gaps, we conducted a comprehensive review with a systematic search of the literature on the subject, encompassing both scientific research and institutional publications. Our review encompassed 517 papers, with a particular focus on three key areas: (1) delineating the constituents of Decent Work, (2) exploring the materiality of Decent Work, and (3) examining how firms value, measure, and report Decent Work. The domain of regulated reporting for Decent Work and its material impact is relatively nascent, resulting in limitations in effectively measuring its tangible, material effects towards a green and just transition. Consequently, our review, with a systematic search of the literature, uncovered notable gaps within the body of literature concerning Decent Work, its substance for ESG materiality regulations, and its conspicuousness for a just transition. Furthermore, our review serves as a critical foundation for fostering discussions and emphasises the practical implications of enumerating the materiality of Decent Work, without which a just transition would be unattainable. By highlighting these deficiencies, we aim to enhance the understanding and implementation of the materiality of Decent Work within the broader context of ESG and the green transition.

1. Introduction

The background and significance of Decent Work within the context of the green and just transitions, sustainability, and ESG can be understood through the examination of corporate statements, compliance reports, and the evolving regulatory landscape. Many organisations, firms, and groups emphasise the importance of their employees, and other stakeholders, as their most valuable asset and highlight their contributions to the community, often referred to as corporate citizenship or corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Devin 2015; Gatti et al. 2019). These statements serve as “green washing with promises of decent work as ‘window dressing’ and PR” (Bozkurt et al. 2022) and as self-laudatory compliance measures operating under the “comply or explain” principles, where certain disclosure actions are encouraged but not mandatory (Galle 2012, p. 1; Global Sustainability Standards Board 2021). However, such posturing without credible external monitoring and validation may merely help achieve minimal compliance standards and guidelines (Laufer 2003). This phenomenon has been described as “non-performativity,” where naming something does not necessarily translate into effective action (Ahmed 2016, p. 2).

The two main challenges facing the 21st century are said to be the protection of the environment and the transformation of Decent Work for all (Stanef-Puică et al. 2022). Similarly, governments and regulatory bodies, such as the United Nations (UN), indicate that a transition to a green economy requires “decent work and green jobs” (Ocampo 2013). Furthermore, the European Commission (EC) has introduced stringent guidelines for a green and just transition under the aegis of environment, social, and governance (ESG) considerations (EU 2020). Precisely within the social (S) aspect of ESG, firms are increasingly required to provide third-party-audited statements regarding their commitment to providing Decent Work to all employees and potentially to those of major suppliers and partners (EU 2020). These ESG regulations, aimed at shaping coherent policies for a green economy with Decent Work for all, govern firms’ reporting obligations and emphasise the materiality of Decent Work, utilising the double materiality mechanism1. The objective of these regulations is to reinforce and enhance social norms, urging companies to surpass minimum decency standards and strive for more substantial actions (Mintzberg 2015) and for justice of labour in the green restructuring of the global production and supply chains (Stevis and Felli 2015). Consequently, companies are no longer merely expected to proclaim their support for Decent Work; they are now accountable for delivering it.

The construct of Decent Work encompasses various dimensions and is, therefore, framed as an umbrella term with different levels of “greenness” (Pettinger 2017, p. 2), encapsulating critical rules and norms that govern and protect employees and society. The International Labour Organisation (ILO), entrusted with formulating and enforcing international labour standards, officially ratified the concept of Decent Work in 1999 (ILO 1999). Nevertheless, the construct of Decent Work and how it aligns with a green and just transition is abstruse at the national level and not clearly disseminated more broadly within the commercial world, where it is to be enacted. By understanding the multifaceted nature of Decent Work, we can delve into its material implications and explore its role in promoting green transitions which are just, sustainable, and socially responsible practices within the realm of the ESG norms.

2. Research Objectives and Rationale

The primary objectives of this study are to expand and enhance the existing literature on the materiality of Decent Work and its importance to a just transition, taking into account the limited extent and early stage of empirical research in this area (Pereira et al. 2019). By conducting a review with a systematic search of the literature, this study aims to benefit researchers, governments, workplace participants, and relevant organisations in terms of understanding the relationship of Decent Work through green transitions and, thus, the significance of Decent Work for a just transition.

The specific research objectives are as follows: Firstly, to review the literature with systematic searches (Phillips and Barker 2021) and develop a clear definition of Decent Work within the context of the green transition and the S component of ESG, focusing on appropriate requirements outlined in the European Union (EU) Regulation 2020/8522. This objective seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of the different factors of Decent Work within the framework of ESG. Secondly, to evaluate empirical research to identify the criteria of Decent Work that hold material significance for the integrated reporting of firms. This objective aims to assess which aspects of Decent Work have tangible impacts on the financial and nonfinancial performance of organisations, as captured in their integrated reporting. Finally, to identify, if available, empirical research that explores methodologies for measuring Decent Work within the context of ESG that lead to a just transition. This part of the objective seeks to uncover existing approaches or frameworks used to quantify and assess the extent to which Decent Work practices are being measured and implemented by organisations in alignment with the EU ESG materiality principles.

By pursuing these research objectives, this review contributes to the existing literature by seeking to determine the level of understanding and “to look at what is left out” (Velicu and Barca 2020, p. 9) of the dissemination of the concept of Decent Work and its materiality. It aims to shed light on whether the literature reveals that organisations fully comprehend the significance and the materiality of Decent Work and whether they effectively communicate their efforts, shortcomings, and outcomes related to Decent Work in their reporting practices. Ultimately, this study aims to advance the knowledge and understanding in the field, thereby supporting the advancement of sustainable and responsible practices related to the materiality of Decent Work within the broader context of ESG and a just transition.

3. Overview of the Literature Review with Systematic Research Methodology

In this study, a review with a systematic methodology for searching the literature was employed to comprehensively analyse the literature on Decent Work and ESG, taking into account both academic and institutional sources. The authors recognised the importance of evaluating both types of sources to provide a comprehensive context for the discussion. Following guidance on conducting empirical reviews (Pasek 2012), which involve the analysis of quantitative and sometimes qualitative scientific data on real-world phenomena, a structured approach was adopted.

Our review encompassed a particular focus on three key areas: (1) delineating the constituents of Decent Work, (2) exploring the materiality of Decent Work, and (3) examining how firms value, measure, and report Decent Work within the framework of the EU regulations. The search process involved the utilisation of relevant keyword search terms related to the materiality of Decent Work, a green and just transition, and ESG, specifically “Decent Work and the Green Deal”, “Decent Work and Materiality”, “ESG and Decent Work”, “Double Materiality and Decent Work”, “Decent Work and the Green Transition”, and “Decent Work and a Just Transition”. The authors conducted searches of prestigious and appropriate academic journals, most notably Nature and journals published by Springer, as well as in databases including Scopus, MDPI, ProQuest, the EBSCOhost Research Database, and authoritative databases from institutional online libraries such as the UN, ILO, the European Commission (EC), and the Global Reporting Index (GRI). The search was limited to studies published in English and from a date range starting in 1999, since this was the key point when the concept of Decent Work was introduced (Somavía 1999). A total of 893 papers were identified through this structured literature review method with queries. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of database and journal research queries.

Research papers that were initially identified within specific journals, after the Scopus query, are excluded in the table under different rows due to duplicates, hence the large number of papers associated with the Scopus search.

To further enhance the analysis, the authors applied the practical and efficient three-pass method for reading research papers (Keshav 2007). This led to 517 of the initially identified papers being further examined. Moreover, 31 additional articles cited within the papers identified were considered in order to ensure a comprehensive exploration of the literature. As a result of our analysis, a total of 56 academic papers and 32 institutional papers and reports were identified as providing information relevant for the review objectives, namely, to create a detailed overview of the development and present status of the literature on Decent Work and its materiality for a just transition.

Considering the specific nature of Decent Work within the ESG framework, as guided by the EU directives and regulations, the search terms were not extended to include broader concepts such as “meaningful work”, “good jobs”, “EU Green Deal”, “precarious work”, or “Green Jobs”. A job classified as “green” does not necessarily constitute Decent Work, and Decent Work is not automatically a green job (Rodríguez 2019). Furthermore, Bowen and Kuralbayeva (2015) provide a comprehensive summary, concluding that despite the large number of such reviews, there are still significant methodological flaws about the nature and quality of green jobs. Research further shows that a green job is not necessarily translated into safe, healthy, and Decent Work (Moreira et al. 2018). While these terms may have generated a higher volume of research, they were not directly aligned with the focus and scope of the present study focused on the materiality of Decent Work for a just transition.

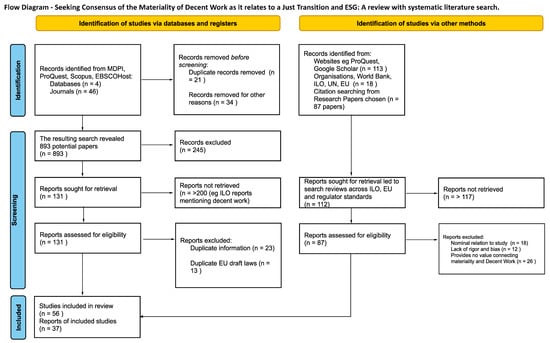

Such different, and evolving, nomenclature required the current authors to analyse the content of individual articles quite meticulously at the stage of selection for analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram—seeking consensus on Decent Work as it relates to a just transition and ESG: A literature review with a systematic search methodology (Page et al. 2021).

By employing this literature review with a systematic search methodology, the study ensures a rigorous and comprehensive examination of the existing literature on the materiality of Decent Work as it relates to green transitions and ESG, contributing to a thorough understanding of the topic within the specific context of the EU regulations and directives. Furthermore, this study provides a robust understanding of the importance of the materiality of Decent Work in order to achieve a just transition.

4. The Origins of the Concept of Decent Work

To acquire a detailed comprehension of the concept of Decent Work, it becomes essential to trace its historical development and key milestones in regulations and international agreements.

The origins of employee rights and regulations can be traced back some 200 years to the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, with the emergence of centralised and mechanised factories, routine work, and the abolition of slavery in certain regions, thus laying the groundwork for modern employment practices and corporate citizenship.

However, of significance to this study, the origins of the concept of Decent Work can be attributed to the Treaty of Peace with Germany (Treaty), signed by the League of Nations on 28 June 1919, following World War I. The Treaty, which established the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in conjunction with its Constitution (Part XIII, p. 7), played a pivotal role in shaping the concept. Article 23 of the Treaty called upon all member nations to strive for “fair and humane conditions of labour for men, women, and children”, both domestically and in their international commercial and industrial relationships.

The Treaty recognised the significance of a broadly understood determinant of well-being, namely, the physical, moral, and intellectual essence of industrial wage earners on a global scale, emphasising social justice and the regulation of labour conditions. It laid the groundwork for international labour law, addressing matters such as the regulation of working hours, the establishment of maximum working hours per day and week, the provision of adequate wages, vocational training, workers’ health and safety, and specific protections for women and children (Treaty of Versailles 1919, Section XIII, p. 7).

In 1944, towards the end of World War II, a landmark convention was held in Philadelphia by the ILO, marking a transformative period in its history. The attendees of the convention ratified the Declaration of Philadelphia, which served as an addendum to the ILO Constitution, reinforcing its aims and objectives. The Declaration emphasised the belief that universal and lasting peace can only be achieved through social justice (ILO 1944). Finally, in 1946, the ILO became what is determined as a specialised agency of the United Nations (UN).

The definition and dimensions of Decent Work, therefore, encompass the principles and values established through international agreements and regulations. These include the promotion of fair and humane working conditions, protection of workers’ rights, provision of adequate wages, access to education and training, and ensuring the health and safety of workers. The historical foundations and subsequent developments in international labour standards have contributed to the understanding and advancement of Decent Work as a vital aspect of labour rights and social justice.

5. The Growing Recognition of Decent Work as a Policy Priority

Juan Somavía, the former Director-General of the International Labour Organization (ILO), introduced the concept of “Decent Work” in his authoritative report presented at the International Labour Conference in 1999 (Somavía 1999). This report outlined the Decent Work Agenda, which has since been a subject of extensive discussion and examination in terms of how it can be practically measured (Ferraro et al. 2015). Decent Work is a broad and multifaceted concept that encompasses both quantitative and qualitative aspects.

The significance of Decent Work resonated with various United Nations (UN) agencies and aligned organisations, as it became recognised as a fundamental part of a more comprehensive agenda aimed at fostering a fairer form of globalisation (Ferraro et al. 2016). In September 2000, over 170 nations adopted the United Nations Millennium Declaration, committing themselves to a global partnership to combat extreme poverty. The declaration established a set of specific and time-related (to be achieved by 2015) targets known as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The MDGs specifically acknowledged the importance of Decent Work in reducing poverty and included a target to achieve full and meaningful employment and Decent Work for all people with specific regulations and norms affording protection. The goal encompassed the quality of employment, considering to what extent it was informal and the amount and appropriateness of pay. These measurable indicators highlighted the recognition of Decent Work as an essential component within the context of the global supply chain.

As the impact of globalisation became more apparent, the understanding and recognition of Decent Work expanded. Decent Work was recognised as a causal factor in “the social impact” of the global open market system with the release of the World Commission Report on the Social Dimension of Globalization (ILO 2004, p. 8). It acknowledged that while globalisation offered significant economic opportunities, it also contributed to social inequalities and personal insecurities (ILO 2011). This recognition further reinforced the importance of addressing Decent Work within the broader discourse on the consequences of globalisation.

Overall, the concept of Decent Work is, thus, an attempt to regulate and create fairness to overcome some of the evolving challenges and aspirations in the global marketplace and provide a just economy. It gained prominence through the Decent Work Agenda outlined by the ILO and found resonance in global development initiatives such as the MDGs. By addressing both the quantity and quality of employment, Decent Work aims to promote fair and equitable labour conditions and contribute to poverty reduction and social well-being in an increasingly interconnected and globalised world.

6. Decent Work and the European Union

Decent Work has been explicitly incorporated into the development agenda of the European Commission (EC) since 2006, through what is known as the European Consensus on Development, which emphasised the EU’s commitment towards promoting employment and Decent Work and solidifying the social and just aspect of globalisation. This commitment was further reinforced through the European Commission’s policy document titled Promoting Decent Work for all, which called for collaborative efforts among EU institutions, member states, social partners, and other stakeholders to advance Decent Work globally. In 2008, the partnership between the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the EU played a significant role in providing policy guidance and promoting Decent Work and social justice within the European Union.

In 2015, the United Nations announced the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In the same year, a consensus was reached by UN signatories on the Paris Agreement. Both initiatives, the SDGs and the Paris Agreement, highlighted the essential nature of Decent Work in policies for sustainable and inclusive growth and development. The UN 2030 SDG Agenda, adopted by more than 190 governments, sets forth 17 SDGs that aim to address interconnected economic, social, and environmental challenges. Decent Work is recognised as a vital component of these objectives, including “poverty eradication, climate action, health, food security, nutrition, education, and Decent Work for all”. The UN General Assembly emphasised the ILO’s Four Pillars of Decent Work Agenda, in which the four pillars are (1) employment creation, (2) social protection, (3) rights at work, and (4) social dialogue. These four pillars are integral elements of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Specifically, SDG number 8 focuses on “promoting sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and Decent Work”. It also highlights the detrimental consequences of a lack of Decent Work opportunities on the social contract and the need for shared progress in democratic societies.

The integration of Decent Work into the European Union’s development agenda and its alignment with global initiatives such as the SDGs reflect a concerted effort to address the multifaceted challenges of promoting equitable and sustainable economic and social development, both within the EU and globally. By emphasising the importance of Decent Work, these frameworks aim to ensure that work is dignified, rights are protected, and individuals can benefit from inclusive, sustainable, and just economic growth.

The Paris Agreement, ratified by governments worldwide, represents the first international treaty to explicitly reference the imperative of a:

“…just transition of the workforce and the creation of Decent Work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities”.

This highlights the interconnectedness of the Paris Agreement and the SDGs, as well as the hurdles faced in achieving Decent Work, particularly in the context of environmental challenges and growing inequality. The importance of Decent Work and sustainable employment was further emphasised in the Silesia Declaration at COP-24 in 2018, which recognised the role of a just transition and Decent Work in securing public support for long-term emission reductions and achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Whilst the Paris Agreement primarily focuses on environmental risks, the SDGs encompass 17 specific and interrelated goals with 169 associated targets that constitute the central aspects of the 2030 agenda toward achieving sustainable development globally. Both frameworks acknowledge the fundamental importance of Decent Work for all. In 2016, the EU ratified the alignment of its policies, regulations, and directives with the UN SDGs and affirmed its commitment to the Paris Agreement. The EU further pledged to integrate the SDGs into its policy framework, ensuring that all EU norms and plans, both domestically and globally, consider the SDGs from conception. In June 2017, the European Commission confirmed the EU and its member states’ commitment to the full, coherent, comprehensive, integrated, and effective implementation of the 2030 Agenda. Moreover, in December 2019, the Commission released its strategy, known as The European Green Deal, which reiterated the commitment of the EU to the provisions of the Paris Agreement, building upon an earlier decision in October 2016.

The alignment of EU policies and actions with the SDGs and the Paris Agreement underscores the EU’s recognition of the importance of Decent Work and sustainability in achieving inclusive and environmentally sound development. It highlights the need for close cooperation between society, governments, and employers to ensure that sustainable and green jobs are not merely sustainable by default but designed to encompass the principles of Decent Work.

7. Further Relations between Decent Work and ESG

The construct of Decent Work may sound nebulous and hard to “pin down”. Nevertheless, employers will invariably claim to provide Decent Work. However, without a clear understanding of the implied definition, the mere term Decent Work may be “acceptable” to one person and may mean something different to another person. To paraphrase a well-worn expression, if something is not clearly defined and understood, then it is difficult to measure (Burchell et al. 2013). Despite some ambiguity, Decent Work is widely agreed to include some core tenets.

A construct such as Decent Work should not be dismissed as “soft,” nor lost in imprecise, ill-defined nomenclatures. However, that may be the case with Decent Work as it is defined by the International Labour Organization, specifically as employment that is

“…productive, delivers a fair income with security and social protection, safeguards the basic rights, offers equality of opportunity and treatment, prospects for personal development and the chance for recognition and to have your voice heard”.(ILO 2013)

Regardless of the potential obscurity of the term, in fact, according to some researchers, the goal and its targets and indicators have some significant shortcomings that render them inconsistent with international labour law standards (Frey and MacNaughton 2016). Furthermore, the term Decent Work has barely scratched the surface of recognition within commercial firms, let alone institutions and government organisations (Randev and Jha 2022).

The term Decent Work may be ambiguous and not clearly represent its significance in a just transition; however, the construct entails well-structured and formal norms such as the following:

- Regulation of the hours of work, which includes setting limits on the maximum working day and week.

- Regulation of labour supply to prevent unemployment and ensure workers receive an adequate living wage.

- Protection of workers against sickness, disease, and injuries arising from their employment.

- Safeguarding the rights of children, young persons, and women in the workforce.

- Provision for old age and injury benefits for workers, along with protection of their interests when employed in countries other than their own.

- Recognition of the principle of equal remuneration for work of equal value, ensuring fair pay regardless of gender or other factors.

- Recognition of the principle of freedom of association, allowing workers the right to organise and join trade unions to collectively advocate for their rights and interests.

Whilst these core tenets of Decent Work are understood and robustly regulated in many countries, firms may also need to assess and report on their supply chain to ensure compliance with all aspects of Decent Work. Thus, the term and measurement of Decent Work will take on new impetus, as it is to be reported upon by the firms and institutions that are subject to the European Union’s ESG regulations. In 2019, the ILO outlined the four pillars of the Decent Work Agenda: employment creation, social protection, rights at work, and social dialogue. With these four pillars came a more robust definition:

“Decent work sums up the aspirations of people in their working lives. It involves opportunities for work that is productive and delivers a fair income, security in the workplace and social protection for families, better prospects for personal development and social integration, freedom for people to express their concerns, organise and participate in the decisions that affect their lives, and equality of opportunity and treatment for all women and men”.(ILO 2023)

Despite these well-intentioned efforts, Decent Work remains a broad term encompassing a combination of topics, from quantitative factors to qualitative information depicting the meaningful characteristics of employment. ESG regulators have found it highly complex to establish clear and objective criteria for evaluating companies’ performance concerning Decent Work. Moreover, measuring such performance proves to be even more difficult due to the multifaceted international nature of labour-related issues and the diverse contexts in which global companies operate. The dynamic and constantly evolving nature of national and international labour practices further adds to the challenge of accurately assessing and quantifying a company’s adherence to the ILO’s international labour standards (Waas 2021).

Consequently, as integrated ESG and Annual Reports begin to take shape, firms and their auditors will need to better understand how they monitor and measure Decent Work. Nonetheless, despite the lack of a common terminology, most aspects of Decent Work are, likely, implemented through alternative terms and definitions, which are spread throughout employment norms and national employment legislation. In support of this objective, the ILO offers a compilation of statistical Decent Work guidelines, accompanied by a collection of descriptive legal framework indicators. This combined approach serves to place the legal and policy framework of specific countries and jurisdictions in context, enhancing the understanding of the conditions and practices related to Decent Work (ILO 2012). The ILO further illuminates the fact that definitions for Decent Work indicators are based, to the extent possible, on agreed international norms and standards. (ILO 2012 Report—Decent Work Indicators Concepts and definitions).

8. Decent Work in ESG and the Green Transition

Research on the materiality of Decent Work, ESG, and the green transition is lacking. For example, in labour law, employment and the environment have been considered as conflicting realities (Zbyszewska 2018). To this end, Tomassetti (2018, p. 84) indicated that: “the alignment between traditional functions of labour regulation and the principle of environmental sustainability could be done with few policy and normative adjustments which incorporate environmental concerns into the traditional dynamics of labour law as aimed at combining efficiency/productivity with decent work”.

From the standpoint of EU regulations, companies are expected to follow the principle of “do no significant harm,” as stated in Regulation (EU) 2019/2088. Additionally, firms are required to consider the regulatory technical standards issued under this regulation, which provide specific specifications and guidance on adhering to the do no significant harm principle. This approach aims to ensure that companies act responsibly and avoid causing significant negative impacts on the environment, society, and other stakeholders, thus enabling the green transition. In addition, Regulation (EU) 2020/852 emphasises that companies must abide by the principles outlined in the European Pillar of Social Rights to foster sustainable and inclusive growth (EU [2017] 2018) towards a just transition. This pillar acknowledges the significance of “international minimum human and labour rights and standards”. Consequently, adhering to these minimum safeguards should be a prerequisite for companies to be considered environmentally and socially sustainable.

This approach underscores the importance of integrating social responsibility and respect for human and labour rights into the criteria for determining a firm’s sustainability credentials. An important factor of the EU regulation stipulates that the recorded assessment and provision of Decent Work applies to “all employees, and potentially those of major suppliers and partners”. The EU regulations, therefore, outline a myriad of international laws and norms that firms need to consider (Table 2).

Table 2.

Key regulatory milestones contributing to the definition of Decent Work.

Consequently, through the adoption of the EU Taxonomy, the EU has significantly advanced the construct of Decent Work as it relates to the multitude of international laws and norms and scoped out appropriate elements pertaining to Decent Work within ESG (Table 2). The EU taxonomy directives illuminate concern for social responsibility under the concept of “do no significant harm”. They also recognise the need to advance toward a green and just transition and consistency with international norms and legislation elaborated within a myriad of assorted norms and regulations, such as the eight fundamental conventions of the ILO, the International Bill of Human Rights, the European Pillar of Social Rights, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, the OECD framework for Measuring and Assessing Job Quality (Cazes et al. 2015) together with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.

In addition to conventional employment contracts, there is a category of work that can be characterised as precarious employment. This encompasses roles within the informal economy, gig economy, and those heavily reliant on temporary or fixed-term contracts. It also encompasses positions filled by agency workers, subcontracted labour, and self-employed individuals (Spooner and Waterman 2015). Whilst precarious work can be positive and negative, it may need to be quantitatively and qualitatively assessed as part of ESG assessment towards Decent Work. Some observers (Waas 2021) advocate the use of the Consolidated Set of GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards (GRI 2020, updated GRI 2021). However, an analysis of that 677-page document, whilst important for the green transition, reveals two perfunctory mentions of “Decent Work” within footnotes as subtexts to SDG 8.

The Silesia Declaration (2018, p. 4) specifically states that to achieve a “just transition… decent work and quality jobs are crucial to ensure an effective and inclusive transition to low greenhouse gas emission and climate resilient development”. However, rather than providing a clear sense of how a just transition can be achieved, it “exposed the gap between climate policy makers’ and the general population” (Morena et al. 2020, p. 2).

Therefore, to fully understand Decent Work as it relates to the green transition and, hence, ESG regulations, the present authors recommend that a systematic analysis should be undertaken to comprehend the myriad EU-wide regulations, directives, and policies and, more specifically, within each EU nation state’s national laws and how these are mapped onto appropriate international law.

9. The Materiality of Decent Work within ESG Frameworks

Materiality is a decisive concept within finance, accounting, and law, where information is deemed material if its disclosure would likely significantly impact the decisions of reasonable investors. According to the United States Supreme Court, information is material if there is “a substantial likelihood that the disclosure of the omitted fact would have been viewed by the reasonable investor as having significantly altered the ‘total mix’ of information made available.” (SASB 2017, p. 9). However, determining materiality in the context of nonfinancial factors, such as those pertaining to ESG issues, can be more challenging, as there are wider qualitative and quantitative factors.

The assessment of materiality for nonfinancial factors, within ESG, including Decent Work, is not as standardised as it is for financial information. Whilst thresholds for financial audits are well established within corporate accounting law, determining the materiality of nonfinancial factors involves broader considerations and may vary depending on the specific context. Nevertheless, there has been broad interest in materiality within organisation studies, with direct implications for the study of work, including the argument that “every organisational practice is always bound with materiality. Materiality is not an incidental or intermittent aspect of organisational life; it is integral to it” (Orlikowski 2007, p. 1436). It is the current authors’ view that by assessing the materiality of Decent Work, corporations and employers will be able to more thoroughly identify its impact on the green transition.

Recognizing this challenge, various organisations and frameworks have attempted to provide guidance on assessing materiality within the ESG context. For instance, the World Business Council of Sustainable Development (WBCSD), in collaboration with researchers such as Eccles and Krzus (2015), has explored different perspectives on materiality.

It is important to note that the materiality of Decent Work within ESG frameworks may differ among stakeholders and can be influenced by factors such as the industry, geographical location, and the organisation’s specific activities and impacts. External auditors and management play a significant role in determining the materiality of nonfinancial factors during the auditing process, considering relevant regulations, industry standards, and stakeholder expectations.

As the understanding of ESG issues evolves, there is ongoing discussion and refinement of materiality assessments. Organisations, standard-setting bodies, and regulators are working to establish clearer guidelines and criteria for determining the materiality of nonfinancial factors, including Decent Work, within the ESG reporting framework towards a green and just transformation.

In summary, while materiality is a well-established concept in finance, its application to nonfinancial factors such as Decent Work within ESG frameworks is still evolving. Various organisations and stakeholders are actively working to provide clearer guidance and criteria for assessing the materiality of ESG issues, aiming to align these with stakeholder expectations and promote transparency in reporting.

Consider the multiple definitions of materiality, as depicted in Table 3, which is based on an analysis by the World Business Council of Sustainable Development (WBCSD 2021; Eccles and Krzus 2015).

Table 3.

Definitions of materiality used by regulatory reporting standards.

10. Double Materiality

The concept of double materiality has emerged as a response to the recognition that traditional financial materiality assessments may not adequately capture the broader sustainability challenges faced by companies (Jebe 2019). Double materiality expands the notion of materiality beyond financial performance and encompasses both the internal impact of companies on their own financial position and the external impact on society and the environment (EU 2019).

While financial materiality focuses on factors that have consequences for financial performance, double materiality recognises the need to assess and disclose information on social and environmental impacts as well. Regulators, such as the European Commission, have emphasised the importance of considering both financial and nonfinancial materiality to effectively achieve ESG aims and objectives (EU 2019).

By adopting double materiality, companies are required to assess their performance against material standards not only in terms of financial aspects but also in relation to their impacts on stakeholders such as governments, employees, customers, NGOs, and communities (Chiu 2022). This broader perspective aims to ensure that companies consider the external implications of their operations on society and the natural environment, and thus, their impact on a green and just transition.

While the concept of double materiality is gaining traction, it is still a relatively new standard, and its conceptual development is an ongoing process (Chiu 2022). Implementing double materiality poses challenges, particularly in quantifying and assessing the nonfinancial aspects of materiality (Ferraro et al. 2015). Measuring and reporting on social and environmental impacts in a consistent and comparable manner remain areas that require further development and harmonisation.

As the understanding and implementation of double materiality progresses, companies, regulators, and standard-setting bodies are working to address the gaps and develop methodologies and frameworks that provide clearer guidance on assessing and reporting on nonfinancial materiality (Chiu 2022). The aim is to ensure that companies consider and disclose the impacts they have on both financial and nonfinancial aspects, fostering transparency and accountability in sustainability reporting.

11. Synthesis of Findings and the Implications for the Future of Work

The review conducted in this study aimed to address several key objectives: Firstly, it sought to provide a clear definition of Decent Work as it relates to the social component of ESG within the European Union Directive. While the EU and ILO offer indicators and legal frameworks for Decent Work, a significant gap remains in the literature regarding the practical and theoretical assessment and discussion of Decent Work within the context of ESG and, thus, its significance to the material attributes of the green transition.

This lack of standardised materiality assessment creates a challenge, as it can enable greenwashing. This refers to a situation where companies intentionally share favourable details regarding their environmental, social, or governance performance while omitting a complete and well-rounded overview (Lyon and Maxwell 2011). To address this, future research should focus on developing precise guidelines and understanding the specific actions required to ensure meaningful implementation and measurement of Decent Work at both country and company levels. This would involve mapping Decent Work to relevant local and international legislation, policies, and norms, as well as aligning it with ESG requirements and regulations.

Secondly, the review aimed to evaluate research to determine which criteria of Decent Work are material to the integrated reporting of companies. Unfortunately, the literature in this area is sparse, highlighting an intention–realisation gap where the practical application of Decent Work in integrated reporting remains limited.

To bridge this gap, future research should focus on providing a comprehensive body of credible research that underscores the materiality of the social component and its contribution to the construct of Decent Work and a green transition. This would inform academics, practitioners, policy makers, and legislators, providing them with valuable insights and evidence-based recommendations.

Consequently, whilst it is clear from this review that the materiality of Decent Work is significant if we are to achieve a just transition, to fully understand Decent Work as it relates to environmental factors and ESG, the present authors recommend that a systematic analysis should be undertaken to comprehend the myriad regulations, directives, and policies and more specifically focus on individual countries’ national laws and mapping these onto appropriate international law.

Whilst the materiality of Decent Work falls under the auspices of the social component of ESG, future research could analyse whether Decent Work needs to be measured across the spectrum of environmental, social, and governance components of the regulations in order to achieve a green and just transition.

In summary, future work should concentrate on mapping the core tenets of Decent Work with individual country laws and norms, developing standardised materiality assessments, addressing the intention–realisation gap in the implementation of Decent Work, and generating a robust body of research that highlights the materiality of the social component and its role in achieving green, sustainable, just, and inclusive outcomes within the ESG framework.

12. Conclusions

As our brief overview of the literature indicates, many academic studies on Decent Work and its significance to a green and just transition omit the materiality aspect of Decent Work. Furthermore, there is a need for all participants to “push for a conceptualisation of materiality which better considers the complexities and the long-term perspective of decent work issues.” (Louche et al. 2023, p. 34). At the same time, it may be a limitation of this paper that it has focused explicitly on one dimension of Decent Work for a green and just transition, that is, the materiality of Decent Work. The EU regulations on the materiality of Decent Work within the ESG framework for a green transition are still in their early stages. Our review indicates that there is a need for further research, awareness, and methodology development to effectively understand and assess Decent Work within the context of ESG regulations and its significance towards a green and just transition. The lack of comprehensive guidance and research poses challenges in analysing material environmental and social factors, which encompass all dimensions of Decent Work, both within a firm and in its supply chain. However, it is crucial for firms to consider these factors, as they can have a significant impact on the financial performance and overall sustainability. Incorporating such metrics is increasingly seen as part of firms’ fiduciary and ethical responsibilities. Therefore, more research and attention are required to enhance the understanding and measurement of Decent Work within ESG frameworks, enabling firms to fulfil their obligations and achieve sustainable, just and inclusive outcomes towards the green transition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.; methodology, A.D and C.W.P.L.; validation, A.D and C.W.P.L.; formal analysis, A.D.; investigation, A.D and C.W.P.L.; resources, A.D and C.W.P.L.; data curation, A.D and C.W.P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.; writing—review and editing, A.D and C.W.P.L.; visualization, A.D.; supervision, C.W.P.L.; project administration, A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The EU Commission’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive has a double materiality perspective. See, for example, the EU Guidelines on reporting climate-related information 2019. |

| 2 | Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment, and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 (Text with EEA relevance)—https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32020R0852 (Last accessed 9 November 2022). |

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2016. How Not to Do Things with Words. Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women’s and Gender Studies 16: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, Alex, and Karlygash Kuralbayeva. 2015. Looking for Green Jobs: The Impact of Green Growth on Employment (The Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and The London School of Economics and Political Science, Policy Brief). Available online: http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Looking-for-green-jobs_the-impact-of-green-growth-on-employment.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Bozkurt, Odul, Murat Ergin, and Divya Sharma. 2022. Special Issue of The Prospects for Decent Work in Green Transitions: Imagining and Enacting the Future Information. Social Sciences. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/socsci/special_issues/Decent_Work (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Burchell, Brendan, Kirsten Sehnbruch, Agnieszka Piasna, and Nurjk Agloni. 2013. The quality of employment and decent work: Definitions, methodologies, and ongoing debates. Cambridge Journal of Economics 38: 459–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazes, Sandrine, Alexander Hijzen, and Anne Saint-Martin. 2015. Measuring and Assessing Job Quality. In The OECD Job Quality Framework, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 174. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Iris HY. 2022. The EU Sustainable Finance Agenda: Developing Governance for Double Materiality in Sustainability Metrics. European Business Organization Law Review 23: 87–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devin, Bree. 2015. Half-truths and dirty secrets: Omissions in CSR communication. Public Relations Review 42: 226–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, and Krzus. 2015. The Reality of Materiality: Insights from Real-World Applications of ESG Materiality Assessments. Geneva: World Business Council for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.wbcsd.org/contentwbc/download/12378/184755/1 (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- European Union Regulation (EU). 2019. 2088 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 on Sustainability-Related Disclosures in the Financial Services Sector. Maastricht: European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Regulation (EU). 2020. 852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the Establishment of a Framework to Facilitate Sustainable Investment, and Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088. Maastricht: European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. 2018. The European Pillar of Social Rights in 20 Principles. Maastricht: European Union. First published 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, Fabrizio, Dror Etzion, and Joel Gehman. 2015. Tackling Grand Challenges Pragmatically: Robust Action Revisited. Organization Studies 36: 363–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, Tania, Nuno Rebelo dos Santos, Leonor Pais, and Lisete Monaco. 2016. Historical Landmarks of Decent Work. European Journal of Applied Business Management 2: 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, Diane. F., and Gillian MacNaughton. 2016. A Human Rights Lens on Full Employment and Decent Work in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. Sage Open 6.2: 2158244016649580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galle, Annika. 2012. Consensus on the Comply or Explain Principle within the EU Corporate Governance Framework: Legal and Empirical Research. Ph.D. dissertation, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Deventer, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, Lucia, Peter Seele, and Lars Rademacher. 2019. Grey zone in—Greenwash out. A review of greenwashing research and implications for the voluntary-mandatory transition of CSR. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility 4: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Sustainability Standards Board. 2021. Global Reporting Initiative and Consolidated GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards. Boston: Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 1944. Declaration concerning the aims and purposes of the International Labour Organisation. (Philadelphia Declaration). Paper presented at International Labour Conference, Record of Proceedings, 26th Session, Philadelphia, PA, USA, May 10; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/legacy/english/inwork/cb-policy-guide/declarationofPhiladelphia1944.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- ILO. 1999. Decent Work for All in a Global Economy: An ILO Perspective. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/dgo/speeches/somavia/1999/seattle.htm (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- ILO. 2004. World Commission on the Social Dimension of Globalization: A Fair Globalization: Creating Opportunities for All. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---integration/documents/publication/wcms_079151.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- ILO. 2011. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_144904.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- ILO. 2012. Report: Decent Work Indicators Concepts and Definitions. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2013. Decent Work Indicators: Guidelines for Producers and Users of Statistical and Legal Framework Indicators: ILO Manual: Second Version. Geneva: ILO (International Labour Organization). ISBN 9789221280187/9789221280194. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2023. Decent Work. International Labour Organization. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/decent-work/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Jebe, Ruth. 2019. The convergence of financial and ESG materiality: Taking sustainability mainstream. American Business Law Journal 56: 645–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshav, Srinivasan. 2007. How to Read Paper. Waterloo: Cheriton School of Computer Science, University of Waterloo. [Google Scholar]

- Laufer, William. S. 2003. Social accountability and corporate greenwashing. Journal of Business Ethics 43: 253–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louche, Celine, Guillaume Delautre, and Gabriela Balevedi Pimentel. 2023. Assessing companies’ decent work practices: An analysis of ESG rating methodologies. International Labour Review 162: 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, Thomas P., and John W. Maxwell. 2011. Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure under Threat of Audit. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 20: 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, Henry. 2015. Rebalancing Society: Radical Renewal beyond Left, Right, and Center. First Edition Paperback print edition. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-62656-317-9. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, Sandra, Lia Vasconcelos, and Carlos Silva Santos. 2018. Occupational health indicators: Exploring the social and decent work dimensions of green jobs in Portugal. Work: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation 61: 189. [Google Scholar]

- Morena, Edouardo, Dunja Krause, and Dimitris Stevis. 2020. Just Transitions. In Social Justice in the Shift Towards a Low-Carbon World. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, Jose Antonio. 2013. The Transition to a Green Economy: Benefits, Challenges and Risks from a Sustainable Development Perspective. In Report by a Panel of Experts to Second Preparatory Committee Meeting for United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development. Prepared under the direction of: Division for Sustainable Development, UN-DESA United Nations Environment Programme UN Conference on Trade and Development. New York: Columbia University. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/transition-green-economy-benefits-challenges-and-risks-sustainable-development (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Orlikowski, Wanda J. 2007. Sociomaterial practices: Exploring technology at work. Organization Studies 28: 1435–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, and David Moher. 2021. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 134: 103–12. [Google Scholar]

- Paris Agreement. 2015. Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Preamble, Dec. 12, T.I.A.S. No. 16–1104. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Pasek, Josh. 2012. Writing the Empirical Social Science Research Paper: A Guide for the Perplexed. Emprical Social Science Paper, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Susana, Nuno Rebeelo dos Santos, and Leonor Pais. 2019. Empirical Research on Decent Work: A Literature Review. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 4: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettinger, Lynne. 2017. Green collar work: Conceptualizing and exploring an emerging field of work. Sociology Compass 11: E12443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Veronica, and Eleanor Barker. 2021. Systematic reviews: Structure, form and content. Journal of Perioperative Practice 31: 349–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randev, Kadumbri Kriti, and Jatindeer Kumar Jha. 2022. Promoting decent work in organisations: A sustainable HRD perspective. In Human Resource Development International. Florence: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Josune Lopez. 2019. The Promotion of Both Decent and Green Jobs through Cooperatives. International Association of Cooperative Law Journal 54: 115–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silesia Declaration. 2018. Conference of the Parties, COP-24 Solidarity and Just Transitions Silesia Declaration. Available online: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-14545-2018-REV-1/en/pdf (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Somavía, Juan. 1999. Decent Work: Report of the Director-General. Paper presented at the 87th Session of the International Labour Conference, Geneva, Switzerland, June 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Spooner, David, and Peter Waterman. 2015. The Future and Praxis of Decent Work. Global Labour Journal 6: 245–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanef-Puică, Michaela-Roberta, Liana Badea, George-Laurentin Șerban-Oprescu, Anca-Teodora Șerban-Oprescu, Laurentiu-Gabriel Frâncu, and Alina Crețu. 2022. Green Jobs—A Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevis, Dimitris, and Romain Felli. 2015. Global labour unions and just transition to a green economy. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 15: 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). 2017. SASB Conceptial Framework. p. 9. Available online: https://www.sasb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/SASB_Conceptual-Framework_WATERMARK.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Tomassetti, Paolo. 2018. Labor Law and Environmental Sustainability. Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal 40: 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Treaty of Versailles. 1919. Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Germany. Treaty of Versailles, June 28. [Google Scholar]

- Velicu, Irina, and Stefania Barca. 2020. The Just Transition and its work of inequality. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 16: 263–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waas, Bernard. 2021. The “S” in ESG and International Labour Standards. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 18: 403–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). 2021. Work Commissioned to Align with the European Union (EU) Non-Financial Reporting Directive. WBCSD Members Advice on Their Non-Financial Reporting. AA1000 Accountability Principles. Available online: https://www.accountability.org/standards/aa1000-accountability-principles/#:~:text=The%0AA1000AP%20(2018)%20is%20an,of%20.improving%20long%2Dterm%20performance (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Zbyszewska, Ania. 2018. Labor law for a warming world? Exploring the intersections of work regulation and environmental sustainability: An introduction. Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal 40: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).