1. Introduction

In the time period of 2017–2021, 13.6% of the U.S. population was estimated to be foreign-born. By comparison, in the same year, the percentage of foreign-born persons in the state of California, where this study took place, was estimated to be 26.5% (

United States Census Bureau 2021). References to immigrant youth within education contexts often focus primarily on English learning (

Martin and Suárez-Orozco 2018), and like their peers, their success is often measured by their graduation rates. In 2022, 19.1% of the student population in California were English learners. In the same year, the graduation rate for English learners was 73.3%, 14.1% less than the California average (

California Department of Education 2022).

It is essential, however, to recognize that immigrant and refugee students hold many strengths as they also face an array of diverse challenges. They range from student-level challenges to structural-level challenges situated in larger socio-economic contexts. In addition, some youths are Students with Limited or Interrupted Formal Education (SLIFE), a heterogeneous group representing diverse cultural and linguistic strengths and backgrounds, as well as unique challenges (

Bajaj et al. 2023). Drawing from Students with Interrupted Formal Education (SIFE) literature,

Chang-Bacon (

2021) asserts that there are insights that can be applied to interrupted formal education experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic; notes accommodations that were provided during the pandemic that need to continue for future SIFE students; and highlights the historical denial of these accommodations for SIFE students. Contexts and factors immigrant youth face affect their future trajectories (

Martin and Suárez-Orozco 2018). Hence, this article argues for a more holistic and humanizing understanding of the contexts immigrant and refugee youth are situated in, focusing specifically on a Youth Leadership/Peer Tutoring program.

While the challenges refugee and immigrant students face are significant, the primary foci on challenges alone can and often shadow the strengths these students bring, including resourcefulness, resilience, translanguaging, transworlding, and cultural wealth (

Espiritu et al. 2022;

Koyama and Kasper 2022;

Martin and Suárez-Orozco 2018;

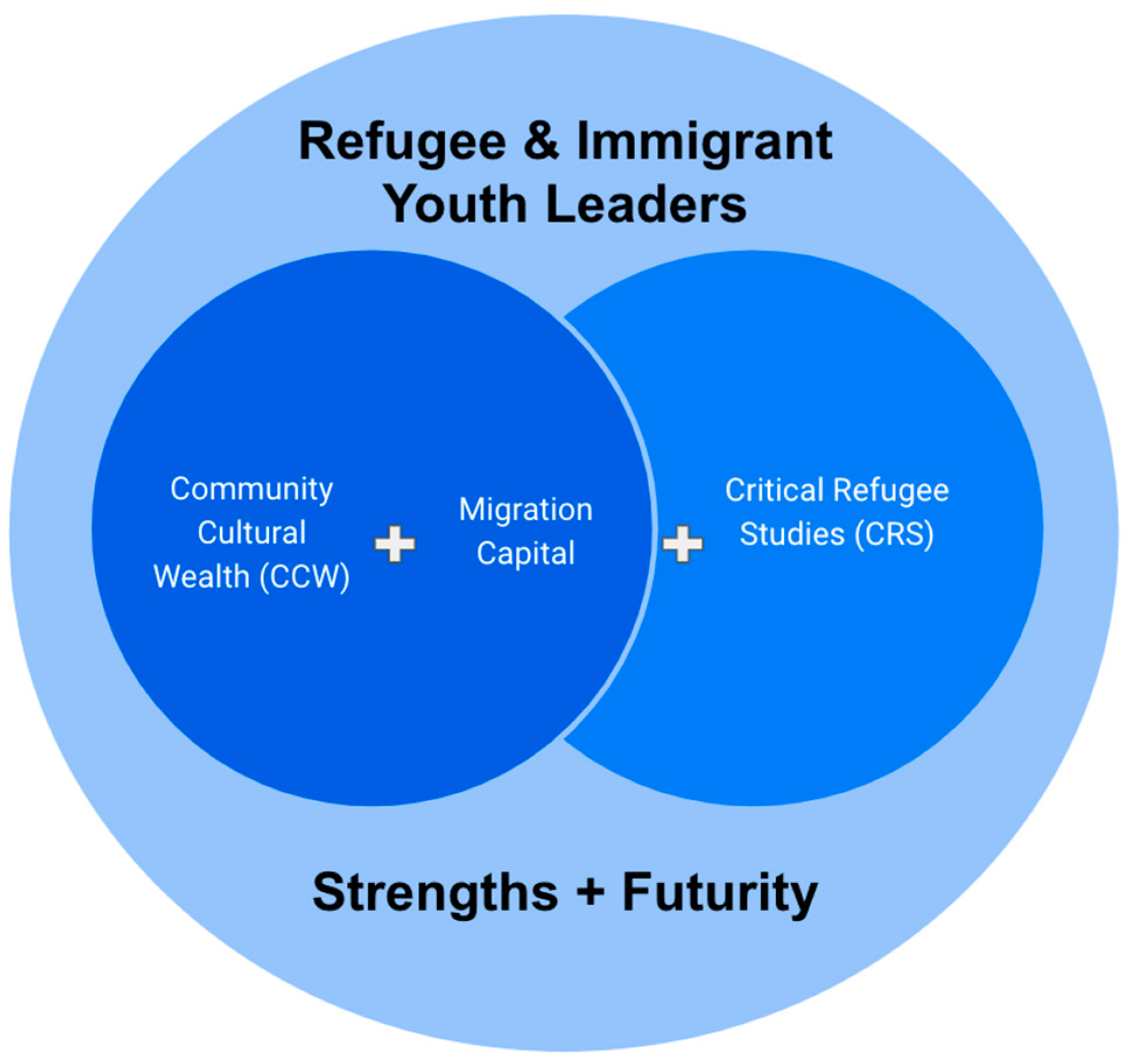

Yosso 2005). We address this concern by bringing together understandings of Community Cultural Wealth (

Yosso 2005) (with the addition of Migration Capital (

Jimenez 2020)) and Critical Refugee Studies (

The Critical Refugee Studies Collective n.d.;

Espiritu et al. 2022) collectively as our conceptual framework (see

Figure 1). In this framework, the former informs our strengths-based (vs. deficit-focused) lens, and the latter informs a focus on “humanity, dignity, and futurity” (

Espiritu et al. 2022, p. 54). Critical Refugee Studies (CRS) shifts the focus away from refugees as problems to solve and rather utilizes a strengths-based lens (which we map to Community Cultural Wealth) in which researchers aim to learn from students’ subjectivities and knowledges to identify more humanizing possibilities within non-formal educational spaces. In this study, we focus on liveability, durability, and futurity (

Espiritu et al. 2022) as well as the role students have in that future by centering the question, “What are your hopes and dreams?” (see

Table 1).

In this study, authors look at the impact of a Youth Leadership/Peer Tutoring program at Refugee & Immigrant Transitions (RIT), a community-based organization in the United States. Going beyond a focus solely on academic homework help, the program takes a holistic approach with multilingual immigrant and refugee students, cultivating a mutually supportive environment in culturally responsive ways. All peer tutors are newcomer immigrant and refugee youth, some of whom received peer tutoring support prior to becoming peer tutors themselves. “Newcomer is an umbrella term for foreign-born students who have recently arrived in the United States. Newcomer students may include, but are not limited to, asylees, refugees, unaccompanied youth, undocumented youth, migratory students, and other immigrant children and youth” (

California Department of Education 2023, para. 1). Similar to the public international high school where most peer tutors attended, we further define newcomer students as students who have been in the United States for four years or less.

This study was inspired by ongoing informal observations the authors had been making with regard to participants and program strengths over the years. In addition to being professors and a recent graduate of a master’s-level graduate program, all three authors, Jyoti, Jane, and Amy, have served multiple positions at RIT since 2010, 2012, and 2018, respectively. During this time, they have served as staff, program participants or volunteers, and/or board members (see positionality statements below). Together, leveraging their diverse insider-outsider perspectives (

Kerstetter 2012), they aimed to better understand the impact of RIT’s Youth Leadership/Peer Tutoring program. The authors view this as a strength of this study, giving the team multiple insider perspectives as well as knowledge that may not have otherwise been captured or seen by outsider researchers.

This study contributes to program development and improvement efforts as it also contributes to a growing body of scholarship around strengths-based narratives (

Espiritu et al. 2022;

Koyama and Kasper 2022;

Yosso 2005), desire-based research (

Tuck 2009), Community Cultural Wealth (

Yosso 2005), and migration capital (

Jimenez 2020). Findings can inform possibilities around the cultivation of present and future youth leaders as well as pan-newcomer community building. The study specifically asks the following questions: What hopes and dreams do former youth leaders have? How has RIT’s youth leadership program contributed to the lives of former youth leaders and how they see the world? How has RIT’s program shaped how former youth leaders think about and define leadership?

Below, we provide a brief literature review related to the themes in this article, review our methods, present results, and discuss implications.

2. Literature Review

Refugee and immigrant students face significant and diverse challenges as they navigate life as newcomers in the United States. In addition to learning the English language, which can take up most of the discussions educators have as it relates to immigrant youth (

Martin and Suárez-Orozco 2018), there are also other significant challenges refugee and immigrant youth experience. For example, Students with Limited or Interrupted Formal Education (SLIFE) must learn academic language that they may not have had previous exposure to and simultaneously navigate adolescence and a new culture. They also “face an urgent need to learn academic content and English before they exceed the legal age limit for remaining in secondary school and ‘age out’ of the system” (Umansky et al. 2018, as cited in

Bajaj et al. 2023, p. 55). Sometimes they do this with their families close by, sometimes translating for their parents, and sometimes they do this alone if they are in the United States without family (

Markham 2018). Structural and systemic issues of poverty also place tremendous pressure on a growing number of immigrant youth, in particular unaccompanied minors, to navigate school and work simultaneously. Sometimes “they end up in dangerous jobs that violate child labor laws” (

Dreier 2023, para. 1). In addition to the challenges these pose in the present day, these factors and more affect the future trajectories of immigrant youth (

Martin and Suárez-Orozco 2018) and need to be taken into consideration.

This work builds upon the emerging field of Critical Refugee Studies (

The Critical Refugee Studies Collective n.d.) and the “growing recognition of the need for a new approach to the study of refugees, a new analytic committed to realizing the meaningful change that refugee knowledge uniquely makes desirable and achievable” (

Espiritu et al. 2022, p. 11). This is particularly important given the narrow focus of refugee law on “well-founded fear” that requires refugees to “relive their victimization through detailed testimonies of explicit and extreme forms of violence… Thus, it is the idea of their victimhood rather than their personhood that shapes the representation of discourse about and policy responses to refugees” (p. 53).

CRS calls attention to community and collective justice (

Espiritu et al. 2022). Thus, this research calls attention to the complex contexts immigrant and refugee students face, as it also challenges the primarily deficit views of immigrants and refugees, in particular Students of Color. In its stead, this research highlights the multitude of strengths in Communities of Color at large (

Yosso 2005;

Yosso and García 2007). In Tara

Yosso’s (

2005) seminal work on Community Cultural Wealth (CCW), she reveals the resources, knowledge, abilities, assets, and skills that Communities of Color employ in order to resist and survive various forms—both micro and macro—of oppression. CCW includes six forms of dynamic and overlapping capitals or strengths, including familial, social, navigational, aspirational, linguistic, and resistant capitals. Rather than judging all communities against White middle-class spaces as the norm or standard (as is often the case in education), CCW moves research and teaching in schools to one that is framed within a larger goal of racial and social justice, calling attention to these strengths.

Jimenez (

2020) adds a seventh form of capital—migration capital, specifically within the context of immigrant youth. While not explicitly framed in Yosso’s CCW,

Jaffe-Walter and Lee (

2018) recognize immigrant “students’ transnational knowledge and attachments” (p. 278);

Koyama and Kasper (

2022) explore ways in which refugee students engage in “translanguaging and transworlding”. With these asset-based bodies of literature in mind, this study extends the idea of “the potential of community cultural wealth to transform the process of schooling” (

Yosso 2005, p. 70) to non-school-based, informal, or partnering educational spaces.

Martin and Suárez-Orozco (

2018) report on ways in which school practices can help newcomers transition, integrate, and grow academically. They group their findings into three categories. The first category addresses the importance of being systematic in your approach to language and literacy acquisition and meeting students where they are. The second category emphasizes the importance of embracing a multicultural culture within schools. The third category acknowledges the importance of community partnerships that can strengthen and enhance school offerings and effects. RIT’s peer tutoring/youth leadership program addresses these three areas; cultivates environments where students are mutually supporting their own and their peers’ learnings; and fosters spaces of respect for diverse and shared experiences as newcomer youth in schools in the United States.

Connecting several bodies of literature referenced above, the idea of co-ethnic, or more generally, multi-ethnic, or multicultural programs is important in the context of growing diversity. In our study, we explore a program that is centered in a multicultural/lingual environment and embraces students from multiple ethnic communities. Extending

Allport’s (

2010) exploration of the benefits of intergroup contact and its role in reducing prejudice between communities through peace education, this study highlights the immense opportunity to cultivate spaces of shared understanding and inter-group solidarity.

These spaces can be informed by growing literature on critical, humanizing, culturally relevant, culturally sustaining, and socio-politically relevant pedagogies (

Bajaj et al. 2017;

Freire [1970] 2018;

Jaffe-Walter and Lee 2018;

Ladson-Billings 1995), as well as cross-cultural relationships that encourage cultural agency among newcomer youth (

Fruja Amthor and Roxas 2016). Ladson-Billings notes teachers’ prioritization of cultivating a community of learners, encouraging “students to learn collaboratively, teach each other, and be responsible for each other’s learning” (p. 163). Immigrant origin or bilingual administrators and teachers can offer insights into immigrant students’ educational experiences (

Martin and Suárez-Orozco 2018). By extension, there is opportunity to also employ similar frameworks in peer learning spaces, such as peer tutoring programs, as is the case in this study, in which tutors, as well as newcomer students, can co-contribute to the learning journeys of tutees and fellow tutors. While literature on peer tutoring tends to focus on the benefits to students receiving tutoring (

Mendenhall and Bartlett 2018), this study looks at the mutual exchanges and benefits to all involved.

International schools offer a more holistic view and ecosystem for educational spaces and schooling for newcomer students.

Mendenhall and Bartlett’s (

2018) study of international schools in New York states the critical importance and roles teachers and peers play, in particular those who share a language. They note many values in heterogeneous learning groups, in which students learn from one another’s experiences and serve as diverse educational resources for each other. Ten out of the 12 participants in this study attended a public international high school.

Bajaj and Suresh (

2018) examine the holistic approach of a public international high school in California. The authors point to wrap-around services that create connections between the home and school and community engagement, as this program also does. This results in a more holistic model that supports not only academic growth but also the material and socio-emotional needs students may have.

It is in this space of seeing students and communities holistically that the peer tutoring/youth leadership program resides—a space that cultivates mutual learning and sees students’ strengths and ways of being. It is through these frames that we also identify more inclusive definitions of leadership, community engagement, and “giving” back, as described in the findings below.

Weng and Lee (

2016) identify four themes that arose in their study on why immigrants and refugees give back to their communities. These include “(1) a desire to maintain ethnic identity and connection; (2) ethnic community as an extension of family; (3) a sense of duty and obligation; and (4) a measure of achieved success” (p. 509). In

Pak’s (

2019) dissertation study with Community Leader-Scholars (CoLS) with refugee experiences, CoLS participants highlight the reinforcing nature of community. This reinforcing nature not only “validates and strengthens community, but it also provides the validation and strength to extend community…Whether this takes place from the local to the global, or the known to the imagined” (p. 144), it can also extend to multicultural/multilingual settings of diverse immigrant and refugee communities.

3. Methods

The motivation for this study was to investigate and evaluate the impact of the Youth Leader/Peer Tutoring program at RIT. Planning meetings with RIT staff began in early 2018. The study received Institutional Review Board approval (IRB Protocol #996) from the University of San Francisco in April 2018, and all participants provided informed consent. All interviews took place during the month of May 2018. Below are more details on the authors’ positionalities, the study site, data collection and analysis procedures, participants, and limitations.

- (a)

Authors’ Positionalities

At the time of writing this article, RIT is in the process of developing a community research praxis in which we aim to locate research within community settings by and with immigrant/refugee communities while also leveraging our positionalities in academia. We recognize the varied positions of power in each location and center the importance of collective and relational work (

Bang and Vossoughi 2016) as we aim to “steward knowledge collectively over long periods of time” (Ochoa 2022, as cited in

Ríos and Patel 2023, p. 9). Recognizing that positions are not fixed, stable (

Ríos and Patel 2023) nor uniform even within one relation, we recognize that authors hold multiple positions and related positions of power simultaneously and are conscientious about how we leverage our multiple social positions towards greater justice for immigrant/refugee communities. We thus offer the following “positionality statements that consider the multidimensional nature of power, oppression, and knowledge production” as we also reflect on positioning, “an ongoing act that takes time, care, and repeated effort to return to these questions” (

Boveda and Annamma 2023, p. 312).

Jane identifies as a child of refugees. Her work is informed by Critical Refugee Studies, liberatory education, community-engaged research, and her family history of forced migration, resistance, and community care. She first joined RIT as a staff member in 2012. While pursuing doctoral studies, she left her staff position and volunteered in RIT’s after-school homework help program (alongside peer tutors, which inspired this study). During her studies, she was invited to serve on the Board of Directors, and then later, after completing an EdD in International and Multicultural Education (IME) from the University of San Francisco (USF), she was invited to rejoin the staff team as Co-Executive Director. She continues in these roles, co-developing a community research praxis at RIT and serving as Adjunct Professor in the Master in Migration Studies (MIMS) program at USF, where she and Amy co-created and co-teach a course on Critical Refugee Studies and Engaged Scholarship.

Amy is a first-generation Latina. She first started volunteering at RIT by providing guidance on this study in 2018 and joined the Board of Directors later that year. She engages in immigrant and refugee rights work and partners with local communities in Central America in their struggle to defend land and water. She earned her EdD in IME from USF and is Assistant Teaching Professor of the Community-Engaged Research and Learning Sociology Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and Adjunct Professor in the MIMS program at USF, where she and Jane co-created and co-teach the aforementioned course on Critical Refugee Studies and Engaged Scholarship.

Jyoti is a former Bhutanese refugee from Nepal. Since 2010, her roles at RIT have included peer tutor/youth leader, alumni tutor, and intern. After graduating from college in 2016, she became a staff member and now leads community engagement efforts that aim to engage volunteers and create more welcoming communities for people who have experienced forced displacement. She is a community leader, mentoring Bhutanese-Nepali youth leaders and engaging community members in storytelling and performance. Jyoti received a Master of Science (MS) in Global Affairs with a concentration in Peacebuilding from New York University in May 2023.

- (b)

About Study Site: RIT and Youth Leadership/Peer Tutoring Program

Originally named the Refugee Women’s Program, Refugee and Immigrant Transitions (RIT) was founded in 1982. RIT is a non-profit community-based organization based in Northern California. The mission of the organization is “to welcome and partner with people who have sought refuge, employing strengths-based educational approaches and community supports so they may thrive in our shared communities” (

Refugee & Immigrant Transitions 2019). RIT students have experienced forced displacement as a result of war, persecution, economic duress, and/or other violence (including state-sanctioned violence). RIT fulfills its mission by “providing free education, family engagement, and community leadership program services to people who have sought refuge in the U.S.” (

Refugee & Immigrant Transitions 2019).

This study centers on and focuses on one of many programs that RIT operates in partnership with public schools in the region, namely its Youth Leadership/Peer Tutoring program. Of the 12 participants in this study, 10 attended one of two public international high schools in the region where RIT ran the after-school homework help program and where most of the peer tutoring experiences referenced in this study were situated. While some of the youth leaders also engaged in other opportunities within RIT’s youth leadership program, such as serving as a classroom assistant in an adult English class or in the early childhood program, this article focuses primarily on the peer tutoring aspect of the program.

Participants were interviewed between one and seven years after they had graduated from high school (except for the case of Vijaya, who was in her final months of high school at the time of her interview). At that time, the program functioned in a much more organic and informal state. However, as they do today, RIT staff and volunteers worked in very close coordination and communication with the school and other community partners. While RIT had not prioritized marketing its programs explicitly at the time participants were engaged with the program, at the time of the interviews, RIT had developed a comprehensive

Peer and Alumni Tutor Handbook (

Refugee & Immigrant Transitions 2018) that both formalized and expanded the program to include peer tutors, peer ambassadors, and alumni tutors. The handbook defines youth leaders, referring to peer tutors and ambassadors, as “persons who are equal or at the same level” (p. 3). They are chosen for their leadership potential, language abilities (multilingual or bilingual), good grades, and “willingness to help others”.

Students can become eligible to become peer tutors by applying/interviewing directly, and/or being referred by staff or a teacher. In some cases, students were approached by staff or teachers; in others, they sought out positions. However, in most cases, the process of becoming a peer tutor began with students receiving tutoring help and then organically growing into peer tutor roles. Sometimes this might have taken place after a staff member observed certain skill sets in the student and then followed up to see if there would be interest in serving as a peer tutor. Several participants shared that they initially started in the program seeking homework help and, after starting to receive help, started helping others. For example, Sita shared how she “used to go to the after-school program to do homework for myself as well…Then I decided to be a peer tutor. I got to help other people, not just my friends. I could reach out to more people. And that was good.” Several participants also noted beginning by seeking help themselves as well as going to the program to be with their friends, and how that sharing extended to them wanting to help others.

As indicated in the handbook title, alumni are also engaged in the tutoring program, as are community volunteers, collectively offering a comprehensive ecosystem of support, not only for the students but for the tutors as well. The program also now includes ongoing training opportunities for tutors, including on topics such as restorative justice and tutoring strategies. Ni stated that if he did not “know something, I can also ask the team members of the program, and they would help”, indicating the strong mutual support that exists in the program for tutees and tutors. Li also notes how the program helped him get into college. This is in addition to the three key benefits listed in the handbook for engaging youth leaders: “connection with students; know the academic work well; language skills” (p. 3).

- (c)

Data Collection Procedures and Data Analysis

As an applied study situated in a community setting, it was essential that the study, including data collection procedures, align with program and organizational goals from the beginning. As such, as an initial step, Jane met with the organization’s Executive Director at the time to explore the purpose of the study, available data, and potential applications. This served as a valuable first step as it identified gaps in data and encouraged the collection of additional data to inform future program development.

The researchers conducted a purposeful sampling strategy (

Creswell 2007). This was broken down into two steps. First, youth leaders/peer tutors who were more active in RIT’s after-school tutoring program served as the basis for participant recruitment for this study. Second, staff then reached out to all former youth leaders to collect baseline data as well as invite them to participate in follow-up, one-on-one interviews.

In total, the research study employed qualitative, semi-structured interviews with 12 former youth leaders/peer tutors. At the time of the interviews, all participants had since graduated from the program, thereby reducing the influence the research team would have had on the direct work of peer tutors/youth leaders. It also employed participatory methods, with Jyoti being a former youth leader and one of the co-researchers in the study.

All authors contributed meaningfully to this study. Jane conducted all 12 interviews and led the research design, collection, analysis, and writing portions of the study. Jyoti contributed to the research design, including piloting and strengthening the interview protocol; conducted participant outreach, recruitment, and scheduling; and assisted with the data collection, analysis, and writing. Amy provided guidance on the research design, interview protocol, literature review, and conceptual framework and contributed to data analysis, writing, and editing.

Average interview times ranged from 30 to 45 min; some were conducted over the phone and others in person. Jane took detailed notes during the interviews, close to verbatim for most interviews. Within one to two hours after each interview, she thoroughly reviewed call notes, jotted down and highlighted any key statements or ideas, filled in gaps, and clarified ambiguities in the notes. All the data were then compiled into one document, organized by question type, and shared with Jyoti and Amy, each of whom manually reviewed the data and identified themes. Jane conducted a thorough coding process that informed categories, which then informed themes/concepts that arose from the data (

Saldaña 2016), then cross-referenced themes with those identified by Jyoti and Amy, identifying overlapping and interrelated ideas. The three also met to discuss these themes and related quotes. By bringing together the multiple ways of interpreting and analyzing the data and coordinating, the three worked together to ensure themes were cohesive and in harmony with one another (

Saldaña 2016). These themes are shared in

Section 4 below.

- (d)

Participants and their Hopes and Dreams

All 12 participants were refugee and immigrant newcomer youth who participated as youth leaders/peer tutors in RIT’s Youth Leaders/Peer Tutoring program. Countries of origin included Burma (Karen), Bhutan, Nepal, China, and El Salvador. All youth also attended high school in California, although at the time of the interview, one was residing in Nebraska (Omaha), four in Ohio, and seven in California (three in Oakland and four in San Francisco).

All participants had been in the United States for four years or less at the time they were serving as youth leaders/peer tutors. Fifty percent of the participants identified as female and 50% as male. The average age of the participants at the time of the interviews was 22 years old (range: 20–26). At the time of the interviews, 67% of the participants were attending or had graduated from college, 50% had jobs, and 83% were contributing to their communities through youth groups, non-profit organizations, churches, and/or community groups. They were contributing to their communities as youth soccer coaches, translators and interpreters, advocates for higher education, and storytellers. At the time of participation, about 67% were simultaneously involved in other programs. All but one of the participants, who was a senior in high school, had graduated from high school.

As newcomers, participants experienced diverse as well as shared challenges when they first arrived in the United States. The most challenging was navigating language barriers, cultural differences, and new systems. In addition to being newcomers, they struggled to fit in at first, especially as teenagers. They experienced social isolation and financial barriers. While getting a good education was one of the top priorities of these participants, some of the aforementioned barriers meant that participants had to hold off or temporarily discontinue their university/college education. However, all spoke of their continued commitment to pursue their hopes and dreams, and they have adopted other ways to be happy and give back to their families and communities. They demonstrate persistence in achieving their dreams, being happy, and making the people around them happy. Sita, for example, shared how she “had to drop out because of personal problems… around that time, I took some break, and took some classes, and helped my community as a community leader.” Rajesh, after moving from California to Ohio, learned the following month that he would need to pay a significant out-of-state non-resident fee to go to college. He had “thought it was just like California where you just go to school and keep your GPA up”, not realizing that one would need to pay an out-of-state fee. He says he will return in the fall. In the meantime, he is working full time in homecare, helping to take people from the Nepali community to appointments as well as help with translations. Other participants noted going to school and working simultaneously.

Youth leaders want to do more than help themselves. As

Jaffe-Walter and Lee (

2018) also found in their study, students think about their communities and how they can give back to them. Participants shared examples that illustrated facing challenges with positivity, patience, adaptability, persistence, and a better vision for their own futures as well as futures for their families and communities. Data from interviews reveal that when provided with opportunities, participants have learned and experienced growth, even if it meant stepping out of their comfort zones.

The following (see

Table 1) provides a brief introduction to participants, including participants’ names, genders, countries of origin, and hopes and dreams. We include participants’ hopes and dreams, as shared in the interviews, in this summary of participants with the aim of representing participants more fully and uplifting desire-based narratives, individually and collectively, as “an antidote to damage-centered research” (

Tuck 2009, p. 416). We discuss this further in the next section.

Table 1.

Participants and their hopes and dreams.

Table 1.

Participants and their hopes and dreams.

| Name * | Gender | Country of Origin ** | What Are Your Hopes and Dreams? |

|---|

| 1. Mu Dah | female | Burma | “I just want to be happy and make my family happy… graduate college, make my parents happy.” Mu Dah is informed by her past experiences, “people from my country, not easy to settle another life”. |

| 2. Sita | female | Nepal | “I’d like to be someone with a degree, a college degree… I would be happy to be able to help people from my community and also people like our community.” |

| 3. Rajesh | male | Nepal/Bhutan | “I want to open a mechanic shop… In the future, within five to ten years, I definitely want to do that.” Rajesh also expresses interest in going “back to college and get a degree”. For his family “the main goal for now is to build a house”. For his community, he desires to help Nepali youth stay in/pursue school given the concerns that many youths are working minimum wage factory jobs. |

| 4. Maya | female | Nepal/Bhutan | “I really want to work with newcomer communities or forcibly displaced populations… I feel like I’m connected to, I understand this population… I feel like I am a part of this group, so I really want to do something.” For family, “my hope and dreams for them is to be happy… and hopefully reunite someday but I don’t know how that’s possible.” |

| 5. Joy | female | China | “I want to be an artist.” For community, “being peaceful, no more war. It’s too big but no more gunshots like last time in Texas. Mason Street where I live by also had gunshot accident, so I recommend gun control. It’s very important for society because the students are innocent, why [should] they suffer the bullet? It’s not the first time for America.” |

| 6. Li | male | China | “Finish my college, get my degree in four years… try to get into the MBA program.” Li lives in the United States alone and says, “I’m hoping I could get a really well-paying job after graduating from college and get back to my own and my family.” Further, “I really want to give back to my high school, too. Maybe I can donate some money when I’m rich, maybe when they have volunteer program, I can apply for the program, definitely.” |

| 7. Vijaya | female | Nepal | “Career wise, I want to be a pilot probably a captain. I want to be an international commercial pilot.” |

| 8. Bishal | male | Bhutan/Nepal | Informed by his previous experiences, Bishal shares, “When I came to this country, I had a lot of dreams. I had a dream to be a successful person so I can help my community and help others as well who are struggling…” He desires to “complete my education, complete my BA find decent job and after I get my job, I’m hoping to donate at least 25% of my income to charity i.e., UNHCR who are taking care of refugees all around the world… I also have a dream to be involved in the community.” |

| 9. Ram | male | Bhutan/Nepal | “My short-term goal is to fit in where I am working right now, to grow at my workplace and at the same time, volunteer around the community that I have been doing. I volunteer in our Nepali community and the long-term goal will be to get my MA degree.”

He continues, “I want to volunteer in community, and I want to help kids. That’s what we’ve been doing.” At my university, “we have more than 100 active members from our community and also there are few from different communities… we help high school students with their school application, their homework help… one on one tutoring, mentoring…” |

| 10. Ricardo | male | El Salvador | “When I graduated from high school, I really wanted to help the immigrant community and I guess that’s how I started doing mentoring because I know some kids travel a lot coming from their home countries, they don’t have an education background and they didn’t have school back there… it’s really hard for them, not just the English barrier.” |

| 11. Ni | male | Karen state of Burma | “I hope that one day I can afford to buy a house I want to get my BA first and then maybe go back to Karen for a little bit and help a little bit because there are a lot of refugees there and need a lot of help and their conditions are very worse than here.” |

| 12. Namita | female | Nepal | “My hope and dream first is to finish my college degree and then get a job. And maybe hopefully after that go to grad school if I can.” She desires to “keep telling our stories so people know about us.” “A lot of people don’t know about Bhutanese refugees and about our people so we want to share about it…so people will know, I guess, and that will not happen again.” |

- (e)

Limitations

A limitation of the study was that, at the time that participants were involved in the program, outward-facing marketing of the program was more informal and organic. Hence, delineations between RIT and other programs based at the schools where the programs were based were not explicit to participants (although they were to staff). Researchers took this into account in how the program was described and how questions were developed for the interview protocol.

4. Results

Below, we share the three main themes that arose in the study.

Through participants’ sharing of their hopes and dreams (see

Table 1), a strong theme that arose and was present throughout was a commitment to community, family, and giving back. This manifested in several areas, including family, education, job or livelihood, and community. These are presented in more detail in

Table 2 and will also be revisited later in this article.

Honing in on the references to family, commitment to community, “giving back”, and peace listed in

Table 2, we see reinforcing and extending possibilities of community beyond one’s immediate family/community (

Pak 2019). The study illustrate connections students had with their own ethnic communities. For example, Ni stated a desire to “maybe go back to Karen for a little bit and help a little bit because there are a lot of refugees there and need a lot of help, and their conditions are very worse than here.” A commitment to supporting and giving back to family was also consistent throughout. What is notable, however, is that the desire to contribute back to the community expanded beyond one’s own ethnic community. In fact, participants explicitly stated going beyond one’s initial peer or community group. That is, in addition to family and ethnic groups, participants—as modeled in the peer tutoring program—desired contributing to more diverse groups of people with shared experiences. For example, several participants had formed a storytelling performance group to advocate for refugee communities. While this started with the advocacy of Bhutanese refugee communities, of which these participants are a part, it has grown to also advocate for other refugee communities more broadly. Maya states, “I really want to work with newcomer communities or forcibly displaced populations… I feel like I’m connected to, I understand this population… I feel for this group because I am part of this group.” Bishal states, “I am hoping to donate at least 25% of my income to charity, i.e., UNHCR, who are taking care of refugees all around the world.” There was a strong sense of resonance in the larger community of immigrants and those who had experienced forced migration from all around the world. While it would be inappropriate to claim that the peer tutoring program was the sole contributor to these mindsets, we posit that it may have helped cultivate and nurture these mindsets and ways of being through the shared and mutually supportive spaces engendered in the program.

Participants’ hopes and dreams, viewed through desire-based research (

Tuck 2009) and a strengths-based lens, also reveal interrelations between the various capitals within

Yosso’s (

2005) framework of CCW and

Jimenez’s (

2020) migration capital. For example, we posit that aspirational capital illustrated through students’ hopes and dreams is informed by migration capital. That is, experiences are gained and knowledge is generated through the experiences of departure and migration to inform past migration-related challenges and better possible futures. We further posit that this is also mutually supportive of

Yosso’s (

2005) familial, social, and navigational capitals as students’ learn to navigate new systems as they also commit to family, community, and other social environments that span intersections of their own ethnic groups and larger affinity groups of newcomers/immigrant/forcibly displaced populations/refugees (see

Table 2).

Most of the participants were first-generation college students. Participants carried joy in this, recognizing that this not only made their families happy but also would allow them to support their families in the future. By following their hopes and dreams, they are fulfilling their commitments to their family’s journeys, hopes, and dreams. For example, Sita shared, “Going to college to support family, I’d be the first one in my family. Makes my family a little bit happy.” Similarly, Rajesh shared, “I’m doing it [moving away from California] for my family. I have to take care of my family in the future.”

Whether this was what led participants to become peer tutors and/or whether they were motivated by the program to further give back is not clear; however, we imagine it was mutually reinforcing, as the desire to give back was informed by some participants’ own lived experiences in and outside of the program, as well as their observations of needs in their communities. The next section shares more about how the program may have contributed to reinforcing and extending the pan-newcomer community.

The program brought peer tutors together in a space that connected them with other programs, people, and resources. There, peer tutors developed communication and problem-solving skills. They learned how to work with people from different backgrounds than themselves. One of the key benefits listed in RIT’s handbook—connection with students—as referenced in the previous section, was a key theme throughout the interviews. This manifested in numerous ways, but primarily through the friendships and connections formed between students with different backgrounds. Vijaya stated that she thinks “the program is good that it introduces people of different cultures and languages. Sometimes it’s hard to break the language barrier and once you do, you start learning and that really brings you together.”

In order to identify the academic needs of students seeking help during tutoring sessions, peer tutors are encouraged to reach out to newer students and initiate conversations. For many, this was not something that came naturally. While peer tutors had been in the United States for longer than tutees and were more advanced in their studies and language abilities, by definition, they were still newcomer students who had been in the country for four years or less and were on their own journeys in relatively newer environments. The following statements are reminders of the importance of such opportunities for all students, including those who hold tutoring roles. Vijaya stated that “even though I was helping the student, it was helping me. I was learning how to communicate.” Rajesh stated that he used to be shy and that being a “peer tutor got me talking to people”. Sita said it got her “outside of my comfort zone”, and “being a peer tutor gave me a chance to be a leader”. Ram shared, “I didn’t just get help, I grew as a person there and grew as a leader.” These findings speak to the significance of building programs around the peer tutors in addition to the tutees.

The majority of peer tutors participated in after-school tutoring programs that took place at one of two public international high schools in Northern California, serving students who have been in the United States for four years or less and originally hail from countries around the world. As such, in addition to communicating with others in general, peer tutors—all English learners themselves—needed to navigate communicating in English in a multicultural and multilingual environment. Li explores this in depth, sharing that his communications skills had improved after participating in the RIT program because “I had to talk every week with a lot of students, different students from every other country around the world.” He later says, “I love seeing students who don’t speak the same language as me or don’t speak English but trying to communicate with me, that is so impressive.” He also said that through the program, “I learned to be a better leader because sometimes [staff] would ask me to lead the after-school activities so that gave me ideas and improved my skills.”

The mutual support and deep understanding of other students’ journeys as English language learners and newcomers is apparent and meaningful. Furthermore, also meaningful is the exposure—the first for many—to working closely with other students from different backgrounds and cultures. Participants spoke about their appreciation for this but also how it influenced their understanding of the community. Mu Dah stated how RIT “helps all the people, they taught me you need to help everyone, not just your family and friends.” She continues sharing how she worked with not just herself from Burma but how she met people from other countries, including El Salvador, and how together they have “become one team, one family”. She notes how, despite the diversity in places of origin, they “have similar stories to us, we can relate to them, we can share pain and they can share with us. It’s like become a family.”

At a time of significant division in the United States, in particular after the election of President Trump, whose administration fueled a growth in anti-immigrant sentiment (

Jaffe-Walter et al. 2018), the importance of a multicultural and multilingual community of support and care resonates deeply. As previously outlined, in addition to peer tutors, RIT’s after-school programs also include community volunteers who RIT trains to also serve as tutors. In addition to being a part of the team, these community volunteers also serve as resources to peer tutors, connecting them to ideas, ambitions, and opportunities outside of and beyond high school. Peer tutors also learn from these community volunteers “how to work with students, how to talk to them, especially how to talk to students who don’t speak the English language” (Bishal). This is extremely valuable, not only for its own sake but also because newcomer communities today are also receiving communities tomorrow.

Ram shares how the program “helps other students new to the country”. Bishal shares how he “learned many things about different cultures and how we can help with our community”. Bringing this all together, Ni states that “we all work together as a team and that it’s not just about helping tutees, but also helping peer tutors learn about students and where they came from”. Mu Dah states that the RIT program “is really good because they help all the people. Not just Burmese or Thai, they help everybody. It taught me you need to help everybody, not just your family and friends, just everybody.” At a time of such negative rhetoric and framing of immigrant and refugee communities, these reflections offer hope, strength, and a vision of a better way of being.

In contrast to images of a hierarchical structure in which one person is leading a group, or what

Bertrand and Rodela (

2018) describe as implicit individualism in leadership, when study participants were asked how they define leadership and how their experiences with RIT shaped how they think about leadership, a consistent theme that persisted throughout was someone who is able to connect with other people on a deep human level. More broadly, leadership, as shared by study participants, was about a commitment to the community and helping others.

Participants defined a leader as someone who is kind, respectful, thinks of others, leads in the “right way”, is patient, honest, and self-confident (Mu Dah, Ram, and Ni). Leaders are ethical, moral, “willing to help”, and have “empathy for others” (Joy). Others stated, “The most important thing is communication”. A core element of communications was listening—to everyone, taking other people’s feedback, and “making them feel like their life matters” (Mu Dah, Li, Vijaya, and Ram).

Striking in consistency was also a focus on contributing to the betterment and lifting up of others. For example, teamwork was also emphasized by several participants. Vijaya stated the importance of understanding other people’s perspectives and then trying “to move forward as one team rather than just follow”. Bishal viewed leadership as a “service that we can provide to other people from which they can get benefit, advantage, and benefit so they can live better”. Ricardo stated that “leadership is when you make the people around you to become better”. It seems then that leadership for participants is connected, aligned, or goes hand in hand with their notions of community, family, and giving back; future facing; and further informed by their experiences working with and in multicultural settings.

5. Discussion and Implications

Data revealed that not only do youth leaders want a future and think about the future (as the questions in this research study prompted through desire-based, strengths-based lenses that center livability and futurity (

Espiritu et al. 2022;

Tuck 2009;

Yosso 2005)), they are also deeply and actively working towards better futures. Further, these futures they are working towards are collective and community-centric in nature. Participants’ stories also re-affirmed the reinforcing nature of communities that have the potential to expand beyond one’s own ethnic or language group to a diverse, broader shared community of support, affinity, and mutual learning (

Pak 2019) that is pan-newcomer in nature. Participants indicated that a simple (albeit challenging for many) act of reaching beyond one’s comfort zone, socially and/or linguistically, with the intention of supporting another’s learning, can open up pathways for mutual learning, support, and understanding.

We capture these learnings in the three themes: commitment to community, family, and giving back; encouraging communication and cultivating a pan-newcomer community; and leadership as commitment to community and positive, collective futurities. There is no one cause, one input, or one variable that may lead to a way of being that is complex, contextual, and fluid. Thus, as stated earlier in this article, it is inappropriate for any one program or organization to claim responsibility for the development of all of the above, which is why we conceptualize this work in the intersecting space of strengths immigrant and refugee youth bring (

Jimenez 2020;

Yosso 2005) and their desires for futures (

Espiritu et al. 2022;

Tuck 2009) together. In addition, by recognizing, engaging, and creating spaces for strengths to lead and desires for collective futures to shine, and intentionally creating humanizing programs that cultivate communications and relationship building, non-formal educational programs can provide opportunities for youth leaders to practice leadership, identify and reinforce the importance of shared spaces, and encourage pan-newcomer community and solidarity, in addition to doing better academically.

As we work on our final edits for this article, we reflect on the growing implications of this study and suggest that they go beyond a program evaluation of a peer tutoring program. Newcomer youth enter complex school environments in the United States that are not always welcoming (some would say some are even hostile). We need to go beyond primary foci on English language learning and four-year graduation rates within newcomer education. There are other factors that matter significantly to one’s educational journey and eventual “educational success”. Basic needs need to be met. At the very least, we know that students cannot study if they are hungry. Students also need to be well, which can be difficult given present day contexts, i.e., anti-immigrant sentiments and policies that systemically dehumanize and oppress immigrant and refugee communities; challenging migration journeys; family situations and limited support networks (including youth who are unaccompanied, sometimes due to forced separation from parents/guardians); increasing numbers of youth enrolling in non-urban school districts that may not be ready nor willing to welcome newcomer youth; under-resourced schools and districts managing increasingly more complex school environments; rise in mental health concerns coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic; growing incidents of gun and generalized violence in the United States, the list goes on. We stress the absolute need to understand the contexts in which newcomer students come from and enter and the critical importance of creating humanizing, welcoming spaces.

As the youth leaders in this study teach us, sometimes it is a simple act of communicating with someone from a different background that can open pathways up for shared understanding, mutual support, and movement towards better collective futures. It would behoove adults to do the same. Peer tutors learned of their peers’ journeys as newcomers, English learners, and having faced other challenges in a new country struggling to restart their lives. It begins with contact, a desire to connect, communications, and community. As Ni shared, he “used to be very shy when I started tutoring and later I learned these people are just like me and we are from other country, and we need help.” Data revealed that peer tutors continued using the skills they learned in the program to later connect with other programs and people and even start similar programs in their communities outside of high school. As such, this study highlights the expanding possibilities of building a pan-newcomer community and solidarity.

In addition, this work motivates further studies that take a strength-based lens to their studies with immigrant and refugee youth, looking at the values of heterogeneous learning groups in which students learn from one another’s experiences and serve as diverse educational resources for one another (

Mendenhall and Bartlett 2018) and extending on the foundation of culturally relevant and responsive pedagogy (

Ladson-Billings 1995) to include socio-politically relevant pedagogy that allows students to understand their likeness in navigating positions of both newcomers and their places of origin (

Bajaj et al. 2017). We are inspired by youth leaders who not only want and think about futures but are also actively working towards better futures that are collective and community-centric in nature. We look forward to the positive, collective futurities youth leaders are co-creating.