Disinformation and Sexual and Gender Diversity in Spain: Twitter Users’ Response, and the Perception of LGBTQI+ Organisations

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Rise of Disinformation through Social Networks and Its Social Impact

1.2. Hoaxes about LGBTQI+ People, Disinformation and Hate Speech

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

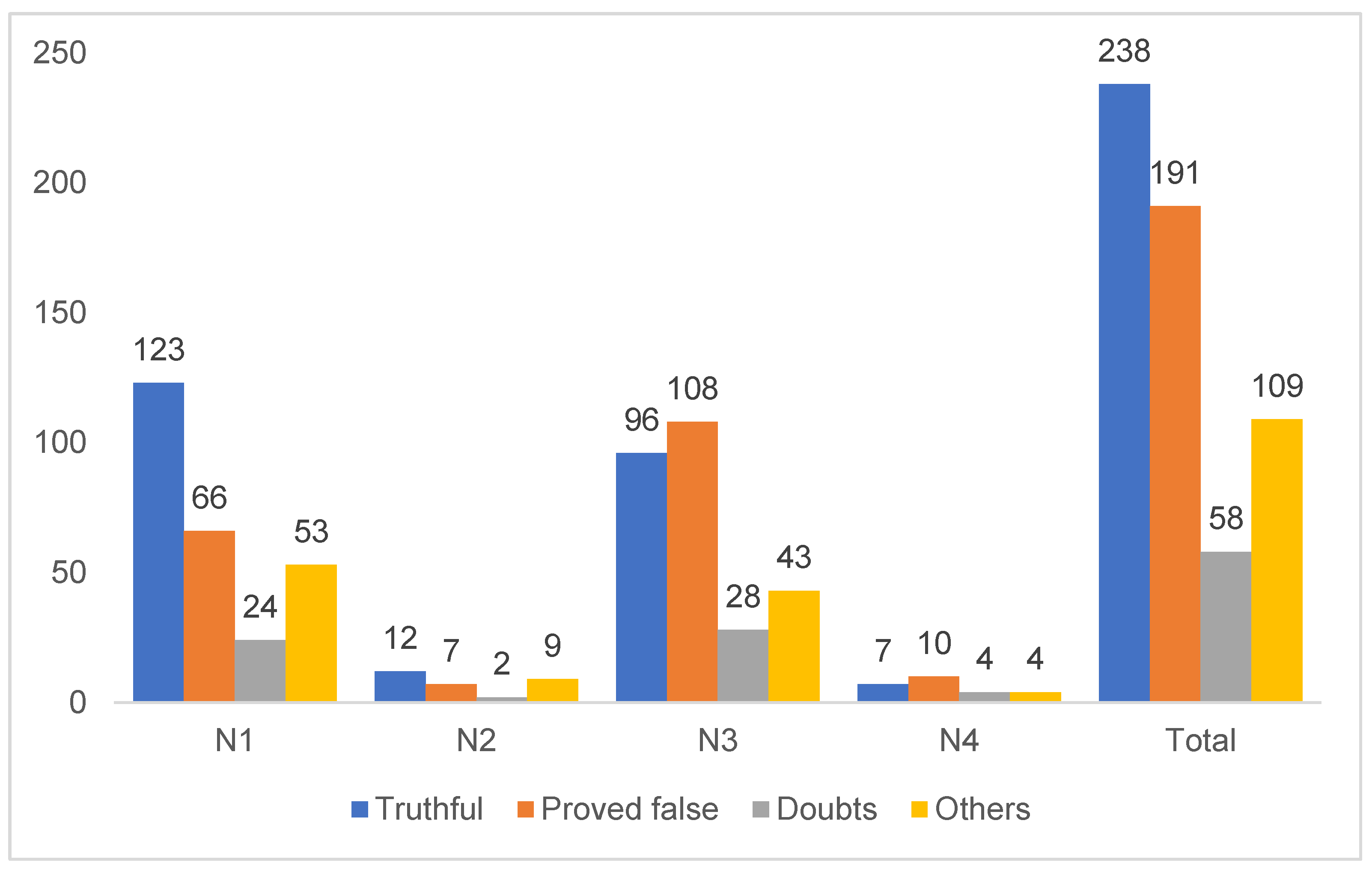

3.1. The Social Audience’s Reaction to Disinformation about LGBTQI+ People

3.2. Activism against Disinformation

3.2.1. Diagnosis of the Problem

“The disinformation is not current, it is historical disinformation. In the Holocaust, what was the largest victim population? The Jews. And the second? LGBTI people and nobody knows about it, it doesn’t appear anywhere… That is historical disinformation, just as crimes of sodomy in the Middle Ages are not usually noted nor that when two women lived together they were accused of witchcraft and burned…”.

“We have been a target population for a long time, and especially since the LGBTI community has been used as a political instrument, by parties and organisations, to use us for votes and pretend that they are helping us, or, quite the opposite, to present us as an axis of power that only seeks to indoctrinate the population and take advantage of it.”

“if we take a historical tour of events at national and international levels, we see that the LGBTI collective has been and is a target group. We can see it happening right now very clearly with monkeypox, which has been used to stigmatise gay men.”

“Traditionally, it has been gay and bisexual men that have been the most visible, and it is this identification with the feminine part that ignites machismo, which is why it is that group that has been most attacked in this sense, historically”.

“We associate the increase to when VOX was voted into the institutions, although it has always been a common theme… But the extreme right being voted in legitimised that discourse in some way.”

“There was a huge movement headed by the People’s Party and the Church demonstrating against the law and accusing us of everything […] the fake news started there as they said that, if equal marriage existed, the rights of heterosexual people would be eroded.”7

3.2.2. The Answer to the Problem

“The main way is to disseminate truthful information… In the end we always move slower and reach fewer people than hoaxes do, but by repeating it, people learn… And always be a reliable source of the information we give, HIV issues, trans or LGBT people, Chinese water torture, until society learns”.

“We believe that respect for diversity can be attained through forceful political advocacy actions […] always being present in the media, taking every opportunity possible for interviews […] disseminating research and studies” (Interview F),

“I really like working with journalists who take the issue seriously and call you with questions. A sensitive media is essential” (Interviewee C).

“tried not to reproduce the hoax when it came to rejecting it. We try not to directly comment on it or give it a specific mention. The rule is to ignore hoaxes, but providing information that helps people understand that it is not true is essential”.

“without alliance, synergy, coordination, there is no progress […] we are always at the Administration’s work tables […] in all areas, health and education, […] we always try to support other entities that, in an cross-sectional and transversal manner, work the different realities, we are not only LGBTI people”.

“neighbourhood networks made up of other groups that are not LGBT but are affected by the extreme right, feminist groups, migrants… we are all the same focus of hatred. The enemy is always the same and the more people they find blocking them, the easier it is: cross-sectionality is key”.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This pseudo-news item was shared six more times from Mediterráneo Digital’s Twitter profile after its original publication in October 2018. It was specifically posted on the following dates: 19 March 2019, 21 February 2021, 19 March 2021, 2 May 2021, 19 March 2022, 1 May 2022, thus coinciding with Father’s Day (19 March) and Mother’s Day (first Sunday in May) in Spain. Only the social audience’s response to the first posting has been analysed for our study, as it was the one that generated the greatest number of comments among Twitter users. |

| 2 | It is a derogatory expression used in Spain to refer to state offices or agencies, which exist almost exclusively to give jobs to friends of senior politicians and allow them to collect large salaries for often unnecessary work. |

| 3 | Vox is a far-right Spanish political party, with representation in the Congress of Deputies since 2019. |

| 4 | The progressive coalition government formed by the Socialist Party and Podemos has pushed for a comprehensive law to expand protections and entrench the rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people, which was approved by Parliament in February, 2023. The regulation has been strongly criticised by right-wing political parties and also by part of the feminist movement, which opposes the gender self-determination recognised in the law. |

| 5 | It should be noted that “affective and ideological polarisation in Spain has been growing in recent years: political parties are increasingly far away in their ideological and territorial positions, and the feelings of one party’s voters towards the rest are among the most negative worldwide” (Miller 2020). |

| 6 | The 2007–2008 financial crisis, or the global financial crisis (GFC), was a severe worldwide economic crisis that occurred in the early 21st century. It was the most serious financial crisis since the Great Depression (1929). |

| 7 | Prominent members of the Spanish Church, representatives of the main conservative party (Partido Popular) and anti-gender organisations developed an intense campaign of opposition to the approval of same-sex marriage in Spain in 2005, which they considered would end the concept of family as they say it should be understood. |

| 8 | Two Benidorm policemen were suspended in May 2020 for a hate crime after one of them was filmed by his colleague verbally insulting and humiliating a trans woman in the street. |

| 9 | The Region of Murcia has a platform of LGBTIQ+ associations that integrates six organisations that fight for the defense of the rights of these social groups. |

| 10 | Mujomur (Young Women of the Region of Murcia) is an association of young women specialised in feminism, gender equality and youth. |

References

- Adamczyk, Amy, and Yen-Chiao Liao. 2019. Examining Public Opinion About LGBTQ-Related Issues in the United States and Across Multiple Nations. Annual Review of Sociology 45: 401–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnesty International. 2021. Amnesty International Report 2020/21. The State of the World’s Human Rights. London: Amnesty International. Available online: http://bit.ly/3X1XV8y (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Arcila-Calderón, Carlos, Patricia Sánchez-Holgado, Cristina Quintana-Moreno, Javier-J. Amores, and David Blanco-Herrero. 2022. Hate speech and social acceptance of migrants in Europe: Analysis of tweets with geolocation. Comunicar 30: 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benford, Robert D., and David A. Snow. 2000. Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Steven Livingston. 2018. The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication 33: 122–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carratalá, Adolfo. 2021. Invertir la vulnerabilidad: El discurso en Twitter de organizaciones neocón y Vox contra las personas LGTB. Quaderns de Filologia-Estudis Lingüístics 26: 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carratalá, Adolfo. 2022. Discursos mediáticos sobre la Covid-19 y sexualidad no normativa: Viejos estigmas ante una nueva pandemia. In El Periodismo, la COVID-19, la «gripe española» y las epidemias históricas. Edited by Julio Yanes, María Gabino, David Fuentefría and JoséLuis Zurita. Madrid: Fragua, pp. 183–99. [Google Scholar]

- Carratalá, Adolfo. 2023. The viralization of stigma online: Hate speech against gay men in connection with the monkeypox outbreak. In Hate Speech in Social Media. Edited by Branco Di Fátima. Covilhã: LabCom Books and EdiPUCE, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, Andrew. 2013. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, Nicole A. 2017. Posttruth, Truthiness, and Alternative Facts: Information Behavior and Critical Information Consumption for a New Age. The Library Quarterly 87: 211–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba, Cristina R. 2021. La situación actual del Colectivo LGTBI en España. Un análisis legislativo de los derechos reconocidos y la protección de víctimas de discriminación por orientación sexual y/o identidad o expresión de género. Ehquidad International Welfare Policies and Social Work Journal 16: 141–64. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 1997. Recommendation No. R (97) 20 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on “Hate Speech”. London: Council of Europe. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680505d5b (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- da Silva, Marcos Paulo, and Luca Souza da Silva. 2021. Disseminação de discursos de ódio em comentários de notícias: Uma análise a partir de notícias sobre o universo LGBT em cibermeios sul-mato-grossenses no Facebook. Intercom: Revista Brasileira de Ciências Da Comunicação 44: 137–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Fresno-García, Miguel. 2019. Desórdenes informativos: Sobreexpuestos e infrainformados en la era de la posverdad. Profesional de la Información 28: 154–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doncel Martín, Israel. 2021. Las minorías como objetivo de las “fake news”: Comunicación y diplomacia pública frente a la desinformación. In La desinformación en la UE en los tiempos del COVID-19. Edited by César Luena, Juan Carlos Sánchez Illán and Carlos Elías. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch, pp. 113–30. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Karen M., Joseph E. Uscinski, Robbie M. Sutton, Aleksandra Cichocka, Turkay Nefes, Chee Siang Ang, and Farzin Deravi. 2019. Understanding Conspiracy Theories. Political Psychology 40: 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, Ludvík, Dana Egerová, Michal Micik, Erika Varga, Csilla Czeglédi, Łukasz Tomczyk, and Michaela Beran Sladkayova. 2020. Trust building and fake news on social media from the perspective of university students from four Visegrad countries. Communication Today 11: 73–88. Available online: https://bit.ly/33UWvFQ (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- European Commission. 2018. A Multi-Dimensional Approach to Disinformation. Brussels: Comisión Europea. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2759/739290 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- European Commission. 2019. Eurobarometer on the Social Acceptance of LGBTIQ People in the EU—2019. Brussels: European Commission. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/combatting-discrimination-0/lesbian-gay-bi-trans-and-intersex-equality/eurobarometer-social-acceptance-lgbtiq-people-eu-2019_en (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Fawzi, Nayla. 2019. Untrustworthy News and the Media as “Enemy of the People?” How a Populist Worldview Shapes Recipients’ Attitudes toward the Media. The International Journal of Press/Politics 24: 146–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galop. 2021. What Is Online anti-LGBT+ Hate Speech and Hate Crime? Galop. Available online: http://bit.ly/3X20PtY (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Gaultney, Ira Bruce, Todd Sherron, and Carrie Boden. 2022. Political polarization, misinformation, and media literacy. Journal of Media Literacy Education 14: 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GLAAD. 2022. Social Media Safety Index. Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation. Available online: http://bit.ly/3EyhHB9 (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Gómez-de-Ágreda, Ángel, Claudio Feijóo, and Idoia-Ana Salazar-García. 2021. Una nueva taxonomía del uso de la imagen en la conformación interesada del relato digital. Deep fakes e inteligencia artificial. Profesional de la Información 30: 668–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfried, Jeffrey, and Elisa Shearer. 2016. News Use across Social Media Platforms 2016. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20160910083105/http://www.journalism.org/files/2016/05/PJ_2016.05.26_social-media-and-news_FINAL-1.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Grambo, Kimberly. 2018. Fake News and Racial, Ethnic, and Religious Minorities: A Precarious Quest for Truth. U. Pa. Journal of Construction Law 21: 1299. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/upjcl21&i=1315 (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Gutiérrez-Coba, Liliana, Patricia Coba-Gutiérrez, and Javier Andrés Gómez-Diaz. 2020. La Noticias falsas y desinformación sobre el COVID-19: Análisis comparativo de seis países iberoamericanos. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 237–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameleers, Michael, Toni van der Meer, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2022. Civilized truths, hateful lies? Incivility and hate speech in false information—Evidence from fact-checked statements in the US. Information, Communication & Society 25: 1596–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasen, Richard L. 2013. A Constitutional right to lie in campaigns and elections. Montana Law Review 74: 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hermida, Xosé. 2022. La eutanasia, la ‘ley trans’, los ERTE y la subida del salario mínimo cosechan un amplio apoyo. El País. Available online: https://elpais.com/espana/2022-01-09/la-eutanasia-la-ley-trans-los-erte-y-la-subida-del-salario-minimo-cosechan-un-amplio-apoyo.html (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- ILGA. 2021. Annual Review of the Human Rights Situation of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex People in Europe and Central Asia 2021. Geneva: International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. Available online: http://bit.ly/3hHKYjZ (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Ipsos. 2021. LGBT+ Pride 2021 Global Survey. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2021-06/LGBT%20Pride%202021%20Global%20Survey%20Report_3.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Kalsnes, Bente. 2018. Fake News. Communication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, Ellie, and Mara Georgescu. 2020. Bookmarks—A Manual for Combating Hate Speech Online through Human Rights Education. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Available online: http://bit.ly/3E9PqQ7 (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Kim, Jeong-Nam, and Homero Gil de Zúñiga. 2021. Pseudo-Information, Media, Publics, and the Failing Marketplace of Ideas: Theory. American Behavioral Scientist 65: 163–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, Nyi Nyi. 2021. Social media, hate speech and fake news during Myanmar’s political transition. In From Grassroots Activism to Disinformation: Social Media in Southeast Asia. Edited by A. Sinpeng and R. Tapsell. Singapore: Yusof Ishak Institute (ISEAS), pp. 86–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lambda. 2022. LGTBIfobia en redes sociales. Informe 2021. Lambda. Available online: https://lambdavalencia.org/wp-content/uploads/al-loro-lgtbfobia-xarxes-socials-2021-esp.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Lee, Tien-Tsung. 2018. Virtual Theme Collection: “Trust and Credibility in News Media”. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 95: 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelo, Thales Vilela, and Lorena Rúbia Pereira Caminhas. 2021. Desinformações sobre gênero e sexualidade e as disputas pelos limites da moralidade. Matrizes 15: 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, Simona (coord.). 2019. #Fake You. Fake News i desinformació. Barcelona: Raig Verd. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Neil. 2017. The bad news about fake news. Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective 6: 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Marston, Hunter S. 2022. Fake News and Elections in Myanmar. In Fake News and Elections in Southeast Asia: Impact on Democracy and Human Rights. Edited by James Gomez and Robin Ramcharan. London: Routledge, pp. 121–44. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Valerio, Lizette. 2022. Mensajes de odio hacia la comunidad LGTBIQ+ en los perfiles de Instagram de la prensa española. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 80: 364–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masip, Pere, Carlos Ruiz-Caballero, and Jaume Suau. 2019. Active audiences and social discussion on the digital public sphere. Review article. Profesional de la Información 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masip, Pere, Jaume Suau, and Carlos Ruiz-Caballero. 2020. Percepciones sobre medios de comunicación y desinformación: Ideología y polarización en el sistema mediático español. Profesional de la Información 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, Spencer, and Chris Tenove. 2021. Disinformation as a Threat to Deliberative Democracy. Political Research Quarterly 74: 703–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Luis. 2020. Polarización en España: Más divididos por ideología e identidad que por políticas públicas. EsadeEcPol Insight 18: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Home Affairs. 2018. Informe sobre la evolución de los incidentes relacionados con los delitos de odio en España 2017; Madrid: Ministerio del Interior. Available online: https://www.interior.gob.es/opencms/pdf/servicios-al-ciudadano/delitos-de-odio/estadisticas/ESTUDIO-INCIDENTES-DELITOS-DE-ODIO-2017-v3.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Ministry of Home Affairs. 2022. Informe sobre la evolución de los delitos de odio en España 2021; Madrid: Ministerio del Interior. Available online: https://www.interior.gob.es/opencms/pdf/archivos-y-documentacion/documentacion-y-publicaciones/publicaciones-descargables/publicaciones-periodicas/informe-sobre-la-evolucion-de-los-delitos-de-odio-en-Espana/Informe_evolucion_delitos_odio_Espana_2021_126200207.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, Craig T. Robertson, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2021. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/3Jeo9hc (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Nolsoe, Eir. 2021. International Survey: How Supportive Would Britons Be of a Family Member Coming Out? YouGov. Available online: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/international/articles-reports/2021/08/31/international-survey-how-supportive-would-britons- (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Observatorio Valenciano contra la LGTBfobia. 2018. Informe sobre delitos e incidentes de odio por motivos de orientación sexual e identidad de género de la Comunitat Valenciana. Año 2017. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1XQf50D51Vaa0FZce3k-4g-7xOOR7InR4/view (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Osuna, Camila Arbuet, and Sofía Cáceres Soforza. 2019. ¿Microfascismos? Sexualidades, fake news y nuevas derechas (Trump-Bolsonaro). Revista Sociedad 39: 114–26. [Google Scholar]

- Palau-Sampio, Dolors, and Adolfo Carratalá. 2022. Injecting disinformation into public space: Pseudo-media and reality-altering narratives. Profesional de la Información 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2022. Social Media Seen as Mostly Good for Democracy Across Many Nations, But U.S. is a Major Outlier. Washington: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/12/PG_2022.12.06_Online-Civic-Engagement_REPORT.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Pousher, Jacob, and Nicholas O. Kent. 2020. The Global Divide on Homosexuality Persists. Washington: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/06/PG_2020.06.25_Global-Views-Homosexuality_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Rathnayake, Chamil. 2018. Conceptualizing satirical fakes as a new media genre: An attempt to legitimize ‘post-truth journalism’ [Conference presentation]. In The Internet, Policy & Politics Conference 2018. Oxford: University of Oxford. Available online: https://bit.ly/2Qs6lIy (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Rhodes, Samuel C. 2022. Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Fake News: How Social Media Conditions Individuals to Be Less Critical of Political Misinformation. Political Communication 39: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Martín, Beatriz, Ireide Martínez de Bartolomé Rincón, and Pilar José López López. 2022. Discurso de odio hacia las personas LGTBIQ+: Medios y audiencia social. Revista Prisma Social 39: 213–33. Available online: http://bit.ly/3ttjRvP (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Rodríguez-Ferrándiz, Raúl. 2019. Posverdad y fake news en comunicación política: Breve genealogía. Profesional de la Información 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas Caja, Fernando. 2020. El fact checking. Las agencias de verificación de noticias en España. bie3: Boletín IEEE 18: 1492–505. [Google Scholar]

- Rosińska, Klaudia A. 2021. Disinformation in Poland: Thematic classification based on content analysis of fake news from 2019. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Herbert J., and Irene S. Rubin. 2005. Qualitative Interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sádaba, Charo, and Ramón Salaverría. 2022. I Estudio sobre la desinformación en España. Madrid: Unión de Televisiones Comerciales en Abierto (UTECA) y Universidad de Navarra. Available online: https://uteca.tv/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/INFORME-SOBRE-I-ESTUDIO-DESINFORMACION-ESPANA-DE-UTECA-Y-LA-UNIVERSIDAD-DE-NAVARRA-a.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Salaverría, Ramón, and Bienvenido León. 2022. Misinformation beyond the media: ‘Fake News’ in the big data ecosystem. In Total Journalism: Models, Techniques and Challenges. Edited by Jorge Vázquez-Herrero, Alba Silva-Rodríguez, María Cruz Negreira-Rey, Carlos Toural-Bran and Xosé López-García. Berlin: Springer, pp. 109–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Duarte, José Manuel, and Raúl Magallón Rosa. 2020. Infodemia y COVID-19. Evolución y viralización de informaciones falsas en España. Revista Española de Comunicación En Salud Suplemento 1: 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, María Soledad. 2021. Por una comunicación pública democrática. Alternativas a la desinformación y los discursos de odio. Revista Sociedad 43: 2–17. Available online: http://bit.ly/3UG9a50 (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Shu, Kai, Amy Sliva, Suhang Wang, Jiliang Tang, and Huan Liu. 2017. Fake News Detection on Social Media. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter 19: 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, Cecilia, and Jakob Svensson. 2019. “Fake News” on Sexual Minorities is “Old News”: A Study of Digital Platforms as Spaces for Challenging Inaccurate Reporting on Ugandan Sexual Minorities. African Journalism Studies 40: 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, Edson C., Jr., Zheng Wei Lim, and Richard Ling. 2018. Defining “Fake News”. Digital Journalism 6: 137–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Emily, Lisa-Maria Neudert, Stacie Hoffmann, and Philip N. Howard. 2020. Follow the Money: How the Online Advertising Ecosystem Funds COVID-19 Junk News and Disinformation. Computational Propaganda Project (COMPROP) Working Paper 2020. Available online: https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/research/posts/follow-the-money-how-the-online-advertising-ecosystem-funds-covid-19-junk-news-and-disinformation/ (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Taylor, Steven J., and Robert Bogdan. 1990. Introducción a los métodos cualitativos de investigación. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Törnberg, Petter. 2018. Echo chambers and viral misinformation: Modeling fake news as complex contagion. PLoS ONE 13: e0203958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. 2019. UN Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech. New York: United Nations. Available online: http://bit.ly/3UWbeFJ (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- United Nations. 2020. Report of the Independent Expert on Protection against Violence and Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, Victor Madrigal-Borloz Violence and Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity during the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. New York: United Nations. Available online: http://bit.ly/3UIedlw (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Valero, Pablo Parra, and Lídia Oliveira. 2018. Fake news: Una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Observatorio (OBS*) 12: 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, Claire, and Hossein Derakhshan. 2017. Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policymaking. Council of Europe. Available online: http://bit.ly/3hL3szY (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Wright, Chrysalis L., and Hang Duong. 2021. COVID-19 Fake News and Attitudes toward Asian Americans. Journal of Media Research 14: 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Headline | Publication Date | Proven False by Maldita | Proven False by Newtral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | The Government will ban Father’s Day and Mother’s Day so as not to offend gays1 | 21 October 2018 | 22 October 2018 | 24 February 2021 |

| N2 | The Health Department has warned that HIV will soar in Madrid during LGBTI Pride week | 30 June 2019 | 5 July 2019 | 7 July 2019 |

| N3 | The Government allows the celebration of Gay Pride in Madrid despite the coronavirus | 30 April 2020 | 30 June 2020 | Was not verified |

| N4 | The Government will create a new hand-out for LGBTI people | 30 June 2020 | Was not verified | 2 July 2020 |

| Person Being Interviewed | Organisation | Area of Operation |

|---|---|---|

| A | Lambda | Valencia |

| B | Castelló LGTBI | Castellon |

| C | Diversitat | Alicante |

| D | SOMOS | Aragon |

| E | No te prives | Murcia |

| F | Colectivo GAMÁ | Canary Islands |

| Comments | Retweets | Likes | Total No. of Reactions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 266 | 626 | 157 | 1049 |

| N2 | 30 | 141 | 124 | 295 |

| N3 | 275 | 823 | 342 | 1440 |

| N4 | 25 | 68 | 19 | 112 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carratalá, A. Disinformation and Sexual and Gender Diversity in Spain: Twitter Users’ Response, and the Perception of LGBTQI+ Organisations. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040206

Carratalá A. Disinformation and Sexual and Gender Diversity in Spain: Twitter Users’ Response, and the Perception of LGBTQI+ Organisations. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(4):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040206

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarratalá, Adolfo. 2023. "Disinformation and Sexual and Gender Diversity in Spain: Twitter Users’ Response, and the Perception of LGBTQI+ Organisations" Social Sciences 12, no. 4: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040206

APA StyleCarratalá, A. (2023). Disinformation and Sexual and Gender Diversity in Spain: Twitter Users’ Response, and the Perception of LGBTQI+ Organisations. Social Sciences, 12(4), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040206