Adapting to Crisis: The Governance of Public Services for Migrants and Refugees during COVID-19 in Four European Cities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

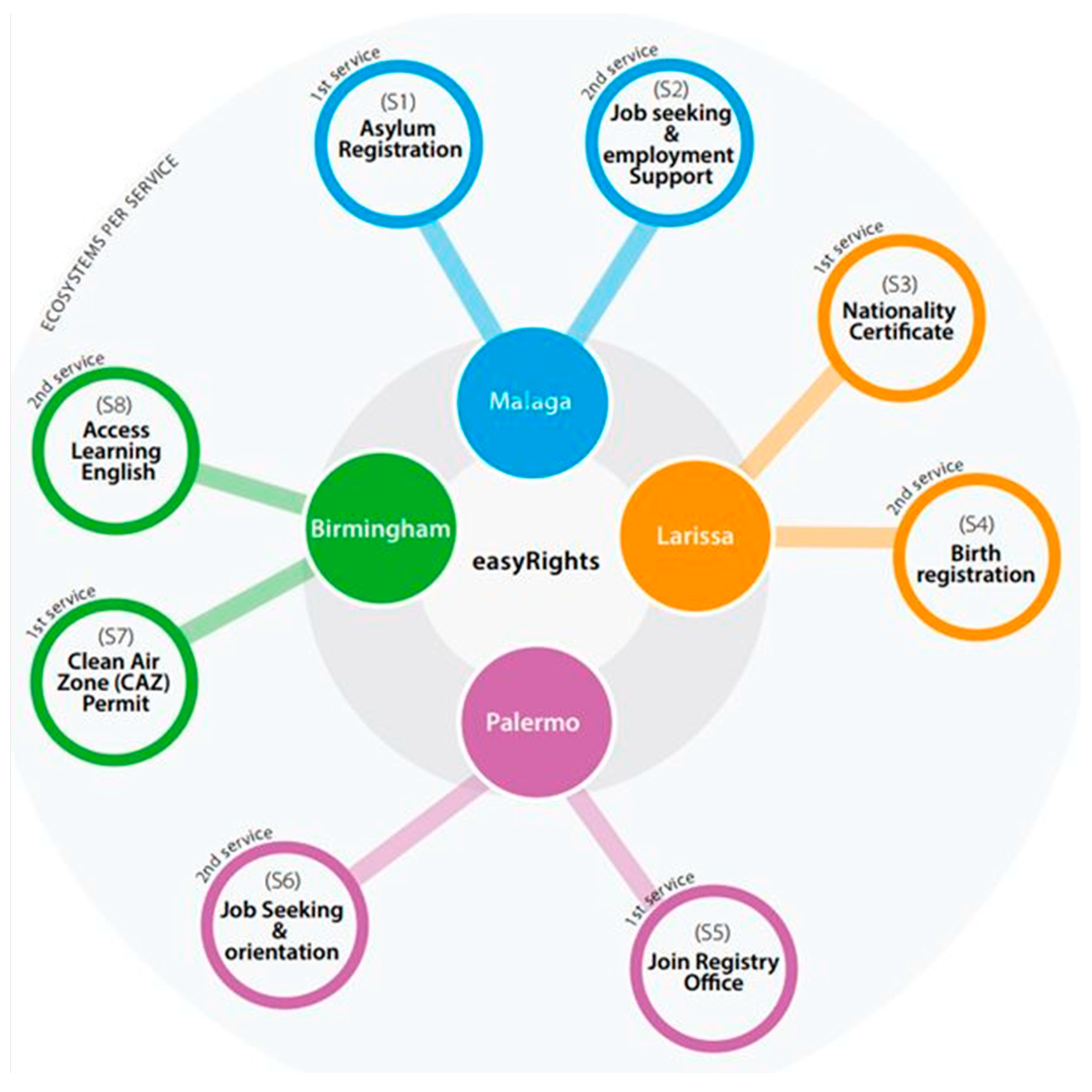

2. The easyRights Project

3. Adapting to Complex Crisis: An Analytical Framework

4. Methodology

- Institutional internal actors (e.g., other departments of a municipality), which contribute to service provision;

- other (external) institutions, such as public, private, non-profit or business partners offering different kinds of support to maintain services pre-, during, and post-crisis;

- institutions who make a specific, relevant contribution to the services, such as communicating with target groups, contributing to discussions as experts, etc.

- an initial comparison of the network maps and identification of similarities and differences that could be addressed and explored in the subsequent rounds of interviews;

- the development of the guidelines for the semi-structured interviews;

- the targeted collection of contextual and background data for the assignments made (descriptions and understanding of the respective roles of named actors, relations, and support resources) and the supplementation/clarification of existing material.

- the amount and composition of the actors/institutions;

- the characteristics of the actors/institutions;

- the nature and characteristics of the relationships;

- the position in the network map and the ongoing prospective adjustments in the different stages of the COVID-19-related measures.

5. Results

5.1. Birmingham

5.2. Larissa

- the municipal Department of Social Services provides, among other things, social services for the elderly, structures and services for children, services for primary care and health promotion, and social structures for poor and vulnerable groups;

- the Registry Office provides both certificates of residence and birth certificates, but also offers a variety of services to all citizens;

- the ICT Department.

- The Civil Protection Department;

- The Immigrant and Refugee Integration Council. This body acts as the Municipality’s consulting instrument and advisory board in order to strengthen the integration of immigrants and refugees in the local community. It comprises six elected official members—four executives of the local Municipal Authority and two members of the opposition—and five migrants;

- The decentralized Administration of Thessaly, providing Greek nationality to immigrants;

- The Municipality’s Public Benefit Enterprise.

5.3. Malaga

- The Inter-Ministerial Commission on Aliens coordinates various departments and the General State Administration;

- The Sectoral Conference on Immigration facilitates the coordination of actions and competencies between the general administration and regional governments;

- The Forum for the Social Integration of Immigrants serves as the primary platform for NGOs and associations to participate in integration policies.

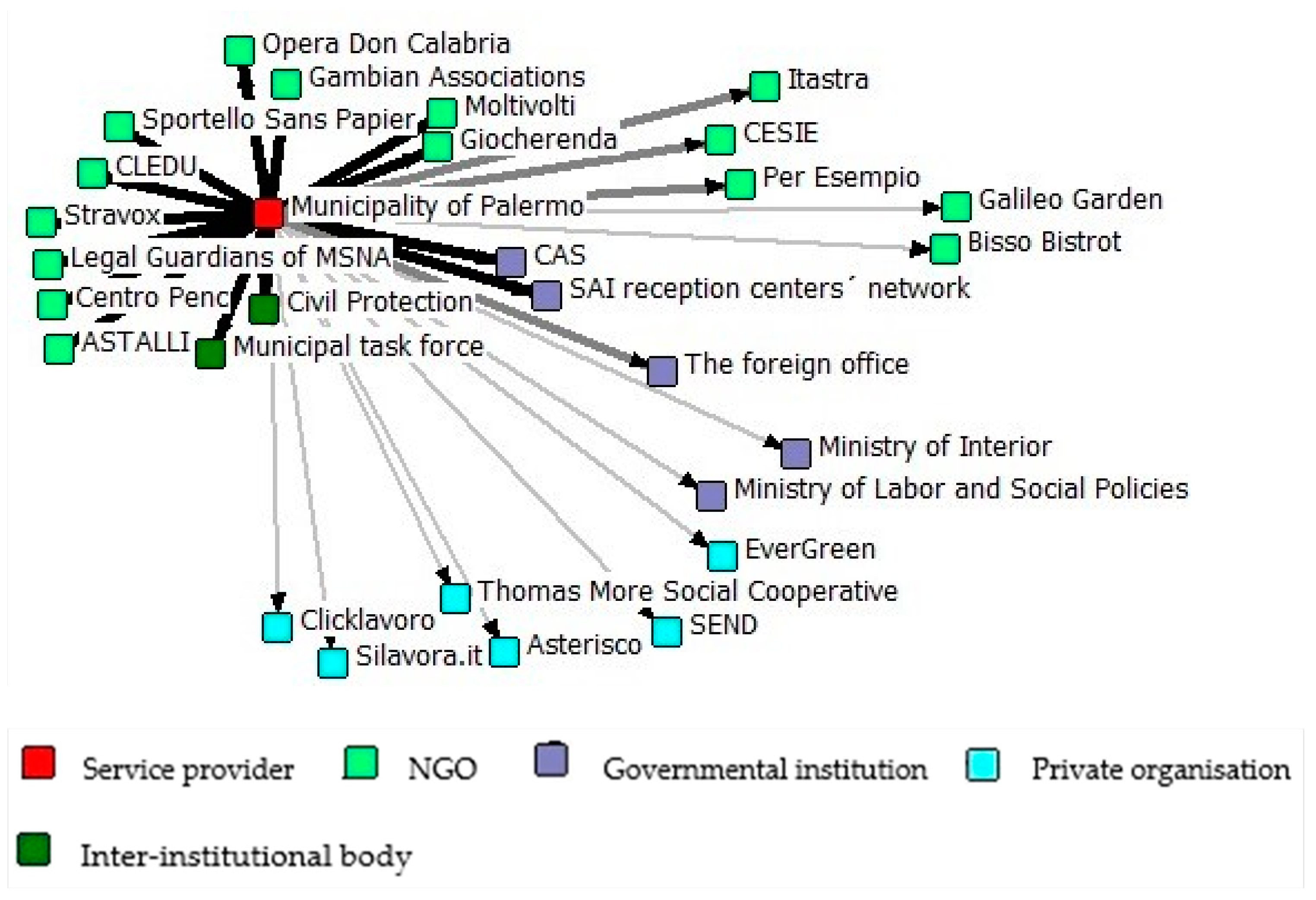

5.4. Palermo

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | We use the term “refugees” to refer to individuals who have been granted international protection by the state where they sought asylum. Furthermore, we use the term “migrants” to cover asylum-seekers, who are individuals waiting for a decision on their asylum claim, third country nationals residing in an EU country without refugee status, as well as EU citizens with a migrant background (in line with the wording used by the European Commission in its Action Plan for Integration 2021–2027). In doing so, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the various groups impacted by the services under scrutiny. |

| 2 | The Quadruple Helix approach to learning describes a process whereby transformation (within an institution, an organization, etc.) is achieved through the interaction between four levels of actors, namely, the national and/or local government, academia, business, and the general public. The approach assumes that the so-called ecosystems are open socio-technical communities, wherein the four groups of actors involved (people, businesses, academics and institutions) share a similar transitional tension and contribute to the development of new practices, also benefiting from experience and knowledge related to the digital world. This transitional tension is considered the engine activating and (possibly) maintaining the Triple Loop Learning mode along the different levels. |

| 3 | easyRights deliverable 5.4: D5.4: Institutional Sustainability Assessment. Soon available at Immigrate Services | EasyRights. |

| 4 | For a thorough description of the integration process in network analysis, see Creswell et al. (2011). Their approach conceptualizes four strategies to integrate network data assessment and analysis: (1) connecting; (2) building; (3) merging; and (4) embedding, though more may be applied in a research design. |

| 5 | The choice of the egocentric network analysis was constrained by the structure and goals of the easyRights project. Compared to complete network analysis, where each node is an ego and the relationships between actors and nodes are included (Hanneman and Riddle 2011), the ego network explores the actors directly linked to the focal points. The semi-structured interviews compensated for this limitation, and identified, to some extent, the relationships between actors irrespective of the focal point. |

| 6 | See the list of interview. |

| 7 | Brum Breathes—monthly dashboard (March 2021). |

| 8 | For an overview of the debate on the digitalization of services for migrants and refugees, see: Tazzioli (2023); Mengesha et al. (2022); Razali et al. (2022). |

References

- Altiparmakis, Argyrios, Abel Bojar, Sylvain Brouard, Martial Foucault, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Richard Nadeau. 2021. Pandemic politics: Policy evaluations of government responses to COVID-19. West European Politics 44: 1159–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, Christopher, Eva Sørensen, and Jacob Torfing. 2021. The COVID-19 Pandemic as a Game Changer for Public Administration and Leadership? The Need for Robust Governance Responses to Turbulent Problems. Public Management Review 23: 949–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Cubas, Magdalena, Anju Mary Paul, Jacques Ramírez, Sanam Roohi, and Peter Scholten. 2022. Comparative Perspectives on Migration, Diversities and the Pandemic. Comparative Migration Studies 10: 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belabas, Warda, and Lasse Gerrits. 2017. Going the Extra Mile? How Street-level Bureaucrats Deal with the Integration of Immigrants. Social Policy and Administration 51: 133–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bentley, Gill, Lee Pugalis, and John Shutt. 2016. Leadership and systems of governance: The constraints on the scope for leadership of place-based development in subnational territories. Regional Studies 51: 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadhurst, Kate, and Nicholas Gray. 2022. Understanding Resilient Places: Multi-Level Governance in Times of Crisis. Local Economy 37: 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campomori, Francesca, and Tiziana Caponio. 2017. Immigrant integration policymaking in Italy: Regional policies in a multi-level governance perspective. International Review of Administrative Sciences 83: 303–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capano, Giliberto. 2020. Policy design and state capacity in the COVID-19 emergency in Italy: If you are not prepared for the (un)expected, you can be only what you already are. Policy and Society 39: 326–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capano, Giliberto, and Jun Jie Woo. 2017. Resilience and robustness in policy design: A critical appraisal. Policy Sciences 50: 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponio, Tiziana, Peter Scholten, and Ricard Zapata-Barrero, eds. 2018. The Routledge Handbook of the Governance of Migration and Diversity in Cities. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorianopoulos, Ioannis. 2009. Tackling Social Exclusion in Greece: Citizenship and Participatory Governance. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 27: 527–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costopoulou, Costopoulou, Maria Ntaliani, and Filotheos Ntalianis. 2021. Evolution of E-Participation in Greek Local Government. Information Polity 26: 311–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, Heaven. 2021. The Politics of Refugee Protection in a (Post)COVID-19 World. Social Sciences 10: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John Ward, Ann Carroll Klassen, Vicki L. Plano Clark, and Katherine Clegg Smith. 2011. Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. Bethesda (Maryland): National Institutes of Health 2013: 541–45. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, JohnWard, Michael D. Fetters, Vicki L. Plano Clark, and Alejandro Morales. 2009. Mixed Methods Intervention Trials. In Mixed Methods Research for Nursing and the Health Sciences. Edited by Sharon Andrew and Elizabeth Halcomb. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 161–80. [Google Scholar]

- Czaika, Mathias, Heidrun Bohnet, Federica Zardo, and Jakub Bijak. 2022. European Migration Governance in the Context of Uncertainty. QuantMig Project Deliverable 1.5. Available online: http://www.quantmig.eu/project_outputs/project_reports/ (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Engle, Nathan L. 2011. Adaptive capacity and its assessment. Global Environmental Change 21: 647–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exadaktylos, Theofanis, and Sevasti Chatzopoulou. 2023. Greece: Command and Control Combined with Expert-Driven Responses? In Governments’ Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Europe: Navigating the Perfect Storm, 1st ed. Edited by Kennet Lynggaard, Mads Dagnis Jensen and Michael Kluth. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2021. CoR–Greece. [online] Europa.eu. Available online: https://portal.cor.europa.eu/divisionpowers/Pages/Greece.aspx (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Enora Palaric, Nick Thijs, and Gerhard Hammerschmid. 2018. A Comparative Overview of Public Administration Characteristics and Performance in EU28. Luxembourg: Publications Office. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/13319 (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Favell, Adrian. 1998. Integration Philosophies. Immigration and the idea of citizenship in France and Britain. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Garbaye, Romain. 2005. Getting into Local Power: The Politics of Ethnic Minorities in British and French Cities, 1st ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés-Mascareñas, Blanca, and Gracia Moreno-Amador. 2020. The Multilevel Governance of Refugee Reception policies in Spain. Available online: https://repositorio.comillas.edu/xmlui/handle/11531/52053 (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Gidley, Ben, Peter Scholten, and Ilona van Breugel. 2018. Mainstreaming in Practice: The Efficiencies and Deficiencies of Mainstreaming for Street-Level Bureaucrats. In Mainstreaming Integration Governance: New Trends in Migrant Integration Policies in Europe. Edited by Peter. W. A. Scholten and Ilona van Breugel. New York: Springer International Publishing, pp. 153–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiraudon, Virginie. 2018. The 2015 refugee crisis was not a turning point: Explaining policy inertia in EU border control. European Political Science 17: 151–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanneman, Robert, and Mark Riddle. 2011. Concepts and measures for basic network analysis. The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis, 340–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlepas, Nikolaos Komninos. 2020. Checking the Mechanics of Europeanization in a Centralist State: The Case of Greece. Regional and Federal Studies 30: 243–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollstein, Betina, and Jürgen Pfeffer. 2010. Netzwerkkarten Als Instrument Zur Erhebung Egozentrierter Netzwerke. Available online: http://www.pfeffer.at/egonet/Hollstein%20Pfeffer.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Hu, Yang. 2020. Intersecting Ethnic and Native–Migrant Inequalities in the Economic Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 68: 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak, Ignacy, María Sánchez-Domínguez, and Daniel Sorando. 2018. ‘Mainstreaming by Accident in the New-Migration Countries: The Role of NGOs in Spain and Poland’. In Mainstreaming Integration Governance: New Trends in Migrant Integration Policies in Europe. Edited by P. W. A. Scholten and I. van Breugel. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, Paul. 2021. Public governance, agility and pandemics: A case study of the UK response to COVID-19. International Review of Administrative Sciences 87: 536–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, Laura, Linsday Campbell, Erika Svendsen, and Michelle Johnson. 2021. Building Adaptive Capacity Through Civic Environmental Stewardship: Responding to COVID-19 Alongside Compounding and Concurrent Crises. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 3: 705178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R., and Toni Antonucci. 1980. Convoys Over the Life Course: Attachment Roles and Social Support. In Life Span Development and Behaviour. Edited by P. B. Balted and O. Brim. New York: Academic Press, pp. 253–86. [Google Scholar]

- Käkelä, Emmaleena, Helen Baillot, Leyla Kerlaff, and Marcia Vera-Espinoza. 2023. From Acts of Care to Practice-Based Resistance: Refugee-Sector Service Provision and Its Impact(s) on Integration. Social Sciences 12: 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler-Koch, Beate, and Rainer Eising. 1999. The Transformation of Governance in the European Union. London, New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann, Sabine, Mikael Hellström, Ulf Ramberg, and Renate Reiter. 2021. Tracing Divergence in Crisis Governance: Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic in France, Germany and Sweden Compared. International Review of Administrative Sciences 87: 556–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, William, Graham Smith, and Gerry Stoker. 2000. Social Capital and Urban Governance: Adding a More Contextualized ‘Top-Down’ Perspective. Political Studies 48: 802–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, Peter. 1981. Introducing Influence Processes into a System of Collective Decisions. American Journal of Sociology 86: 1203–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maor, Moshe, and Michael Howlett. 2020. Explaining variations in state COVID-19 responses: Psychological, institutional, and strategic factors in governance and public policy-making. Policy Design and Practice 3: 228–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, Mariana, and Rainer Kattel. 2020. COVID-19 and Public-Sector Capacity. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 36: 256–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Zelalem, Esther Alloun, Danielle Weber, Mitchell Smith, and Patrick Harris. 2022. “Lived the Pandemic Twice”: A Scoping Review of the Unequal Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Asylum Seekers and Undocumented Migrants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, Donald. 2008. Learning under Uncertainty: Networks in Crisis Management. Public Administration Review 68: 350–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morse, Janice. 2010. Simultaneous and Sequential Qualitative Mixed Method Designs. Qualitative Inquiry 16: 483–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morse, Janice, and Linda Niehaus. 2009. Principles and Procedures of Mixed Methods Design. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley, Hugh. 2011. ‘Decentralisation of Public Employment Services’, 2011, The European Commission Mutual Learning Programme for Public Employment Services. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=14098&langId=en (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Navarro, Carmen, and Francisco Velasco. 2022. From centralisation to new ways of multi-level coordination: Spain’s intergovernmental response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Local Government Studies 48: 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2022a. What Has Been the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Immigrants? An Update on Recent Evidence. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2022b. First Lessons from Government Evaluations of COVID-19 Responses: A Synthesis. Paris: OECD. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=1125_1125436-7j5hea8nk4andtitle=First-lessons-from-government-evaluations-of-COVID-19-responses (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Oliver, Caroline, Rianne Dekker, Karin Geuijen, and Jacqueline Broadhead. 2020. Innovative strategies for the reception of asylum seekers and refugees in European cities: Multi-level governance, multi-sector urban networks and local engagement. Comparative Migration Studies 8: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovich, Kathryn, and Kate Kearins. 2004. Structural Embeddedness and Community-Building through Collaborative Network Relationships. M@n@gement 3: 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peters, B. Guy. 2021. Governing in a time of global crises: The good, the bad, and the merely normal. Global Public Policy and Governance 1: 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridou, Evangelia. 2020. Politics and administration in times of crisis: Explaining the Swedish response to the COVID-19 crisis. European Policy Analysis 6: 147–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridou, Evangelia, and Nikolaos Zahariadis. 2021. Staying at Home or Going out? Leadership Response to the COVID-19 Crisis in Greece and Sweden. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 29: 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, Rodziana Mohamed, Tamara Joan Duraisingam, and Nessa Ni Xuan Lee. 2022. Digitalisation of birth registration system in Malaysia: Boon or bane for the hard-to-reach and marginalised? Journal of Migration and Health 6: 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richmond, Ted, and John Shields. 2005. NGO-government relations and immigrant services: Contradictions and challenges. Journal of International Migration and Integration/Revue de l’Integration et de la Migration Internationale 6: 513–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royo, Sebastián. 2020. Responding to COVID-19: The Case of Spain. European Policy Analysis 6: 180–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakita, Seishiro. 2021. Centralization under Decentralization: The Development of Fishery Clubs in Lesvos under the Administrative Reforms of Greece. Marine Policy 132: 104655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, Peter. 2016. Between National Models and Multi-Level Decoupling: The Pursuit of Multi-Level Governance in Dutch and UK Policies Towards Migrant Incorporation. Journal of International Migration and Integration 17: 973–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scholten, Peter, and Rinus Penninx. 2016. The Multilevel Governance of Migration and Integration. In Integration Processes and Policies in Europe: Contexts, Levels and Actors. Edited by B. Garcés-Mascareñas and R. Penninx. New York: Springer International Publishing, pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schomaker, Rachel, and Michael Bauer. 2020. What Drives Successful Administrative Performance during Crises? Lessons from Refugee Migration and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Public Administration Review 80: 845–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SHARE Network. 2021. Welcome and Integration in the EU: COVID-19 Impact and Responses. Share Network. Available online: https://www.share-network.eu/articles-and-resources/survey1-mz5r4 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Shields, John, Julie Drolet, and Karla Valenzuela. 2016. Immigrant Settlement and Integration Services and the Role of Nonprofit Service Providers: A Cross-National Perspective on Trends, Issues and Evidence. RCIS Working Paper No. 2016/1. Toronto: Ryerson University. [Google Scholar]

- Slootjes, Jasmijn. 2022. The COVID-19 Catalyst: Learning from Pandemic-Driven Innovations in Immigrant Integration Policy. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/pandemic-innovations-integration (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Speer, Johanna. 2012. Participatory Governance Reform: A Good Strategy for Increasing Government Responsiveness and Improving Public Services? World Development 40: 2379–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Hellen, and Chris Skelcher. 2002. Working Across Boundaries. London: Macmillan Education UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tazzioli, Martina. 2023. Counter-mapping the techno-hype in migration research. Mobilities, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zardo, F.; Rössl, L.; Khoury, C. Adapting to Crisis: The Governance of Public Services for Migrants and Refugees during COVID-19 in Four European Cities. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040213

Zardo F, Rössl L, Khoury C. Adapting to Crisis: The Governance of Public Services for Migrants and Refugees during COVID-19 in Four European Cities. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(4):213. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040213

Chicago/Turabian StyleZardo, Federica, Lydia Rössl, and Christina Khoury. 2023. "Adapting to Crisis: The Governance of Public Services for Migrants and Refugees during COVID-19 in Four European Cities" Social Sciences 12, no. 4: 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040213