1. Introduction

Globally, over the last five years, the rise of social media use has been phenomenal. With 2.28 billion users at the end of 2016,

Statista (

2017a) projected the number of users would rise to approximately 3 billion by 2021. However, the actual figure was 4.2 billion, as of January 2021 (

Statista 2022a). One of the social media platforms contributing to this remarkable increase was Facebook. In the first quarter of 2011, Facebook had 372 million active daily users, which rose to 1.325 billion in the second quarter of 2017 (

Statista 2017b). By the fourth quarter of 2021, the number of daily users had risen to 1.929 billion (

Statista 2022b). As a result of this dramatic use of social media in the general population and the lockdowns associated with COVID-19, researchers in the social sciences have embraced the use of social media to undertake research and to recruit research participants.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the academy is producing a growing body of literature in response to the use of this technology and in recognition of the immersive nature of social media in everyday lives (

McCay-Peet and Quan-Haase 2017). This scholarship covers a wide range of subjects, including researching actual events and interactions on the internet, to using the internet as part of the research process. Other research has used tools, techniques, and methodologies to access and analyse the varying types of data on social media (

Quan-Haase and Sloan 2017), as well as collecting data posted on social media sites, such as Twitter and Facebook (

Mayr and Weller 2017). This is in addition to other studies conducting in-depth qualitative research based on social media posts (

Salmons 2017). There is also a growing body of literature on using Facebook in social science research; for example,

Barratt et al. (

2015) used Facebook to access “hidden populations”. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the growth in the use of online methods in fieldwork, including photo/video/voice elicitation, as well as asking participants to complete diaries or journals using voice memos or online platforms or apps (

Lupton 2021). This has been conducted as researchers have adapted to the constraints associated with the pandemic, as

Lupton (

2020, p. 3) argues “social research methods and plans have had to be rethought”.

This paper demonstrates that research using social media technology was being undertaken prior to the pandemic in 2020, and that not all of the methods have had to be ‘rethought’. However, there were certainly additional considerations and processes that needed to be developed in order to adapt research for the online world, including for ethical reasons. This paper demonstrates how to use Facebook ethically and methodologically, highlighting some of the methods used to overcome the challenges that were presented. One area that came to the fore during the pandemic was the recruitment of research participants using non-traditional methods; namely, how could research participants be ethically recruited using social media?

Despite an increase in the use of the internet as a research tool, very few papers discuss the use of social media to recruit research participants, particularly those who are considered to be “socially invisible”. This paper addresses this gap and so brings together the use of social media as an approach to engage and recruit research participants who have experienced numerous forms of gender-related violence (GRV) and particularly those who may choose to use technology as a way of remaining anonymous and thus ‘safe’ when participating in such research. Specifically, this paper focuses on the challenges of recruiting South Asian women who have experienced gender-related violence and also highlights the difficulty in reaching out to these groups. The paper acknowledges that some participants may prefer to seek support through social media rather than through traditional service providers/gatekeepers. This trend emphasises the importance of considering the safety and well-being of participants, particularly those who may have previously avoided engaging with agencies due to fear, stigma, or other concerns.

Access to the online world via high-quality technology facilitates participant participation, but also raises ethical issues; for example, how to deal with sample bias where the sample excludes participants who do not have, or choose not to, access Facebook. This paper argues that where the Internet is used to recruit research participants, then these are in addition to traditional non-digital means, thus avoiding the creation of another ‘invisible group’—namely, those who cannot/do not want to access the internet.

This article explores the practicalities of using Facebook in fieldwork, specifically as a research participant recruitment tool. It describes the steps taken and highlights the benefits of such an approach. Facebook has the capacity to reach large numbers of people and hence increase sample size. As well as the numbers of participants, Facebook can assist researchers to reach marginalised populations and explore sensitive topics, such as GRV, in a safe environment for both the participant and the researcher.

This paper begins by providing a brief overview of the research study. It describes the problems encountered recruiting participants using non-digital methods. It gives reasons as to why this is a sensitive research subject and describes the barriers for women engaging with the research. The paper then discusses the practical steps taken to use Facebook to recruit research participants from this ‘invisible group’ and the benefits it provides. Then, it follows a discussion of the ethical considerations and challenges faced by the researchers.

The authors acknowledge their own positions, as researchers from different backgrounds and ethnicities, privileges, and perspectives. We are a team of two white women, A3 and A2, whose research expertise includes gender-based violence, domestic abuse and violence, as well as female genital mutilation and human trafficking. The lead author, A1, who deployed the use of Facebook for the fieldwork, situates her positionality as a gendered, racialised South Asian woman, researching other South Asian women. She has worked for many years in the UK’s third sector, focusing on domestic violence and abuse. Hence, most of the reflections are based on A1’s responses and reflections to the challenges and considerations encountered. As supervisors of the original research, A2 and A3 reflected together with A1 on the problems and issues that arose. A1’s initials will be used to show the reflections of her direct experiences when undertaking the research.

Please note that this paper is not presenting the findings of the research undertaken. It is an article relating to research methods, specifically using social media in research participant recruitment, together with reflections on such use, including ethical considerations. It critically evaluates the use of social media to recruit participants on sensitive topics who are often within “invisible groups”.

2. South Asian Women’s Experiences of GRV—The Research Project

2.1. Gender Related Violence and South Asian Women

Alldred and Biglia (

2015) define gender-related violence as sexist, sexualising, norm-driven bullying, harassment, discrimination, or violence, regardless of whoever is targeted, including different genders, sexualities, and sex-gender normativities, as well as violence against women and girls. GRV conveys a nuanced understanding of peer violence that goes beyond gender normativity (

David 2018;

guizzo et al. 2018). The intersectional lens provided by a GRV perspective draws attention to the multiple and cumulative ways in which different demographic groups of women can be exposed to increased risks of violence. South Asian women are one such group.

GRV’s inclusivity extends to intersections of gender, race, and culture where women’s racialised gendered experiences include cultural norms of honour and shame. South Asian women living in the UK face additional barriers. Women may have insecure immigration status (

Anitha and Gill 2011), where their migration position is dependent on partners or employers, which increases their vulnerability to abuse and reduces their ability to access support services and justice. By dating and choosing a partner outside of an arranged marriage (

Siddiqui 2005), women may be dishonouring and bringing shame on their family (

Siddiqui 2013).

The pervasiveness of honour is entrenched through the enforcement of moral rules and codes of behaviour on women and girls by partners, family members, and the wider community. The way in which the redemption of honour is carried out by families can lead to severe consequences for women (

Gill and Harvey 2017;

Gill 2003;

Meetoo and Mirza 2007;

Chakravarti 2005). In order to uphold and assert gender roles and expectations, women’s behaviours are monitored within the community (

Gill and Brah 2014). Entering intimate relationships outside of an arranged marriage can lead to serious consequences, such as ostracism from their family and community (

Toor 2009).

2.2. The Research Project

The research explored the experiences of South Asian women who had departed social norms of arranged marriage to form an intimate relationship with a partner of choice. The cohort of women in this study were subjected to GRV from partners, family, and their community because they had subverted so-called respectable arranged marriage norms that are prevalent in their communities because they had chosen partners that were not approved of by their parents. Interestingly, the agentic act of a woman choosing her partner became the very barrier to her leaving the relationship if it turned violent and abusive (

Sandhu and Barrett 2020).

This research was sensitive in nature because participants lived in isolation, in fear of multiple perpetrators, were often traumatised and with severed connections to their culture and families. The researchers were mindful of the possible trauma and stigma South Asian women may have felt due to their experiences of GRV. Thus, this group of women participants were highly likely to have low social visibility, both online and offline, due to the fear of repercussions. At the same time, using Facebook could offer safety if the participants wished to be part of the research and to participate in privacy, at a time and place that suited them.

3. The Challenge—Recruiting Research Participants

Due to the trauma, the sense of loss, and the fear that these women have experienced, as well as the sensitive nature of the research, the expectation of the research team was to primarily recruit participants via agencies that were local, as well as through national specialist domestic abuse and sexual abuse service providers. The researchers included specialist providers for minoritised women. The providers offered a range of services, including legal support, refuge accommodation, counselling, and advocacy work. In total, 76 agencies and individuals were contacted, primarily through A1′s networks from working in the sector in both voluntary and renumerated positions for over two decades. Many of the contacts included CEOs of agencies and managers who specialised in outreach or advocacy. They acted as gatekeepers for their own service users, but also signposted to other agencies.

Calls to agencies where there had been no historical relationship with any of the team were not answered, or the responses indicated that they were unable to support the research in engaging participants. Those agencies which had previously worked with the researchers, responded to say that they did not have participants who met the criteria because they tended to support women who had recently arrived in the UK and on spousal visas, or for those UK women who had arranged marriages or were forced into marriage. Other service providers explained that they were stretched and did not have the capacity to respond to requests to assist in recruiting research participants.

There is a disadvantage to not using gatekeepers when recruiting participants because this meant that the researchers did not have access to using the gatekeeping organisation’s own safeguarding measures and risk assessments (

Edwards and Mauthner 2012). Therefore, ethical processes had to be robust in order to ensure the safeguarding of the participants—who were approaching the researchers directly through social media—as well as the safety of the researchers themselves. This included risk assessments undertaken by the researchers and approved by the university. This ensured that there was an information sheet for participants and that the researchers followed the university’s safety at work policy. These are important ethical considerations when undertaking research using digital communication technology without the ‘safety net’ that gatekeepers can provide.

Therefore, using agencies and gatekeepers to access potential research participants was not fruitful. So the researchers explored other avenues, such as local radio, JISCmail and the website Mumsnet. These also produced few participants. One agency suggested that the research could be publicised on Facebook and that the agency would “like” the page in order to increase the visibility of the research to their online users. This suggestion initiated the process of exploring what social media may offer in terms of recruiting an ‘invisible group’ of women to research a sensitive topic, namely GRV. Using Facebook to broaden the reach and engagement of participants proved to be successful. This was before the COVID-19 pandemic forced many social scientists to use social media for the purposes of both recruiting participants and as a research tool.

It should be noted that the authors have considerable experience in researching vulnerable groups affected by GBV and recommend that those who do not have such levels of experience of data collection with such cohorts should instead consider using gatekeepers to facilitate the recruitment of participants where at all possible.

4. Using Facebook to Engage Participants

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, a small number of researchers had used Facebook as a tool for identifying and recruiting participants. For example,

Lijadi and van Schalkwyk (

2015) conducted a qualitative study with participants who were globally dispersed and who had specific experiences of growing up, frequently moving from one country to another due to their parents’ multiple overseas assignments. They recruited “hard-to-reach” participants by posting in specific groups to publicise their research. In her research exploring how British South Asian Muslim women’s educational and employment experiences altered their gender identities and, consequently, their understandings of marriage,

Mohee (

2012) used Facebook to diversify her research sample. She searched for relevant groups and then asked the administrators of such groups if she could attend in person in order to recruit participants. However, at the time there was little published to guide the researcher concerning the ethical challenges of using Facebook as a method of recruitment of marginalised groups of people by which to discuss highly sensitive topics, such as domestic abuse.

The following is an account of the process and steps followed by the authors to create the Facebook page for recruiting research participants. Ethical approval was sought and given by Coventry University Ethics Committee prior to the initiation of primary collection. Although the research focus was on a vulnerable group, namely women aged 18 and over who had experienced domestic abuse, the ethics committee did not request any DBS checks. As required by the ethics committee, all participants gave written informed consent to be included in the study and all health and safety policies were adhered to.

4.1. Setting Up the Facebook Page

Safety guidelines have to be followed when conducting fieldwork, in person or online. Therefore, one of the first decisions was whether to set up a new Facebook account that was unique to the research or to use A1’s existing personal Facebook page. For security reasons, it was decided that a new Facebook account in A1’s name should be set up. The privacy settings were set to ‘public’ to broaden the reach and to increase the number of participants.

The page name and username were created for the research. The title of the page and the tag reflected the study and the need to attract participants who had or were experiencing domestic abuse. Attention then turned to the profile and the cover photo, and whether to include images that portrayed actual domestic violence. It was difficult to find images that were both free and did not position women in a submissive portraiture. It was important to highlight that this was academic research to give some credence to the project and to increase attention. With these factors in mind, we agreed on a profile and cover photos of university campus buildings, but not images of the faculty nor research centre where the authors were based.

Due to the global reach of Facebook, the participant profile explicitly stated that only those who met the research criteria should get in touch to find out more about the study. The criteria included participants who identified as a woman, as South Asian, had experienced domestic abuse or violence, resided in the UK, and were over the age of eighteen. The ‘invite to participate’ was created as a post, which was pinned to the timeline so that viewers to the page would always see it. A visual image of a leaflet detailing the research and how to get involved was also added to the post to increase engagement with potential participants.

4.2. Communicating the Facebook Page

The next step was to make the page known to as many contacts as possible. All 76 contacts (see above) were invited to ‘like’ the page, follow and hence share the posts. Invites were sent out via Facebook and email. At that time, A1 was not familiar enough with Facebook to increase contacts by searching for Facebook groups and other interested parties. With increased familiarity and experience, A1 has since used Twitter and WhatsApp to recruit participants and so recognises that these avenues are worth considering for future research projects.

Although there was global reach, what was not known was the type and prevalence of GRV amongst those who viewed and liked the page. For example, how many were in non-heterosexual relationships and had experienced GRV not just from intimate partners, but also from their families. The criteria did not specify that the participants had to be in heterosexual relationships. However, all who responded were in heterosexual relationships.

In order to keep the page ‘active’, frequent postings were required. Posts containing relevant news stories or media events were added to continue the engagement with viewers. For example, schedule details of the BBC film “Murdered by my Father”, which told a family’s story of honour-based violence was added to the newsfeed. On reflection, diversity of posts such as those about violence within non-heterosexual relationships may have generated more interest and encouraged further snowballing. This, in turn, would have added to GRV empirical data and thus increased scholarship in this area.

When considering language style and the tone of the posts, a balance was struck between making the page content accessible to an audience with varying degrees of English language comprehension, and promoting the study as a serious intellectual project so that viewers and potential participants recognised that this was genuine research.

4.3. Engagement with Participants

Participants’ interest had to be sustained and built upon. When participants connected via Facebook Messenger they were provided with a mobile number and email address to enable them to contact the researcher to get further information about the research. If the participant gave their mobile number, they were called by A1. The participants were sent the participant information sheet and consent form via Facebook Messenger and/or email, whichever they preferred. The participants were taken through the participant information sheet containing details about the research, including the aims and objectives, so that they had as much knowledge as possible before agreeing to participate. The importance of informed consent was emphasised with the participants (

McCarry 2005) and that they could withdraw from the research process at any time.

Much of the administration, such as scheduling interviews, answering queries, and so forth, was undertaken on Facebook Messenger, which was the preferred method of communication by all of the participants who made initial contact via Facebook. Messages on Facebook are enveloped in end-to-end encryption, so that only the device the message was sent to could decrypt the message. The mobile phone used for communication purposes during fieldwork did not have functionality to access Facebook nor Facebook Messenger. Therefore, any communication with the participants was carried out using web-based versions of Facebook Messenger on a PC or laptop.

Although Facebook introduced the option of video calling in 2015, and so was available at the time of the fieldwork, it was not used as the researchers did not have ethical approval to use it. All communication via Facebook Messenger was conducted by text messaging. The ‘comments’ function on the Facebook page could not be used because anyone who viewed the page could see both the comment and the username of the person posting the comment. Therefore, all communication was conducted by text messaging through Facebook Messenger to ensure participant confidentiality and safety.

The process of recruiting participants in this study continued beyond the initial recruitment phase and overlapped into the interviewing and transcribing phases. To keep interest active, A1 posted messages to inform current and prospective participants of progress. She also posted her reflections; below is such an example, dated 4 January 2017:

This enabled the ‘connection’ to remain with the participants and was a way of generating new interest in the research. Such benefits are not easily obtained using non-digital means.

5. Insights Gained

There were many benefits to using Facebook, both anticipated and those that were unexpected.

5.1. Anonymity of Researcher A1

The reason to foreground the research topic with images of university buildings on the Facebook page was to give credence to the study and divert attention away from A1′s identity as a South Asian woman researcher. Throughout research, feminist scholars continually probe and respond to assumptions of knowledge production and audiences (

McCarthy and Edwards 2011). For women researchers of colour, self-preservation in the world of scholarship and research requires responses to the assumptions of race, class, and gender (

Lorde 1996;

Barker-Bell 2017). It was assumed that participants would be more interested in the research itself as opposed to A1’s background and identity that in itself projected an image and a front of a credible researcher, a credible project, and a credible university (

Goffman 1969). This implicit projection was easier to do online because the technology facilitated remote connection in a way face-to-face interactions could not.

Whether the recruitment of participants was hindered because the identity of A1 was protected is not known and difficult to ascertain, both at the time when the field work was conducted and subsequently during the rest of the research process. No participant mentioned how they had felt about making the initial contact with a project where they did not know who the individual they were contacting was and did not find out until A1 telephoned them. Indeed, initial comments from participants show their interest was in the study and not the identity of A1.

![Socsci 12 00212 i002 Socsci 12 00212 i002]()

![Socsci 12 00212 i003 Socsci 12 00212 i003]()

![Socsci 12 00212 i004 Socsci 12 00212 i004]()

![Socsci 12 00212 i005 Socsci 12 00212 i005]()

![Socsci 12 00212 i006 Socsci 12 00212 i006]()

The women were interested in being part of the research and in sharing their lived experiences, especially if it might help other women (

Buchanan and Wendt 2018). As active agents, the participants had greater control and power to engage, or not, with the research in ways that those women recruited through traditional researcher/gatekeeper relationships did not. Gatekeepers usually decide whether to pass on the research information and the researcher’s details to potential participants. In this study, participants liaised directly with the researcher without having to be recommended or vetted by a gatekeeper or third party. Hence, Facebook removed the need for a gatekeeper.

Recruiting via Facebook meant there were no existing relationships via any sort of networks. This in itself is interesting and requires further investigation to consider what barriers and factors come into play that cause participants to take part in research, or not, and how much of that is dependent on the identity of the researcher and the connection with the research topic.

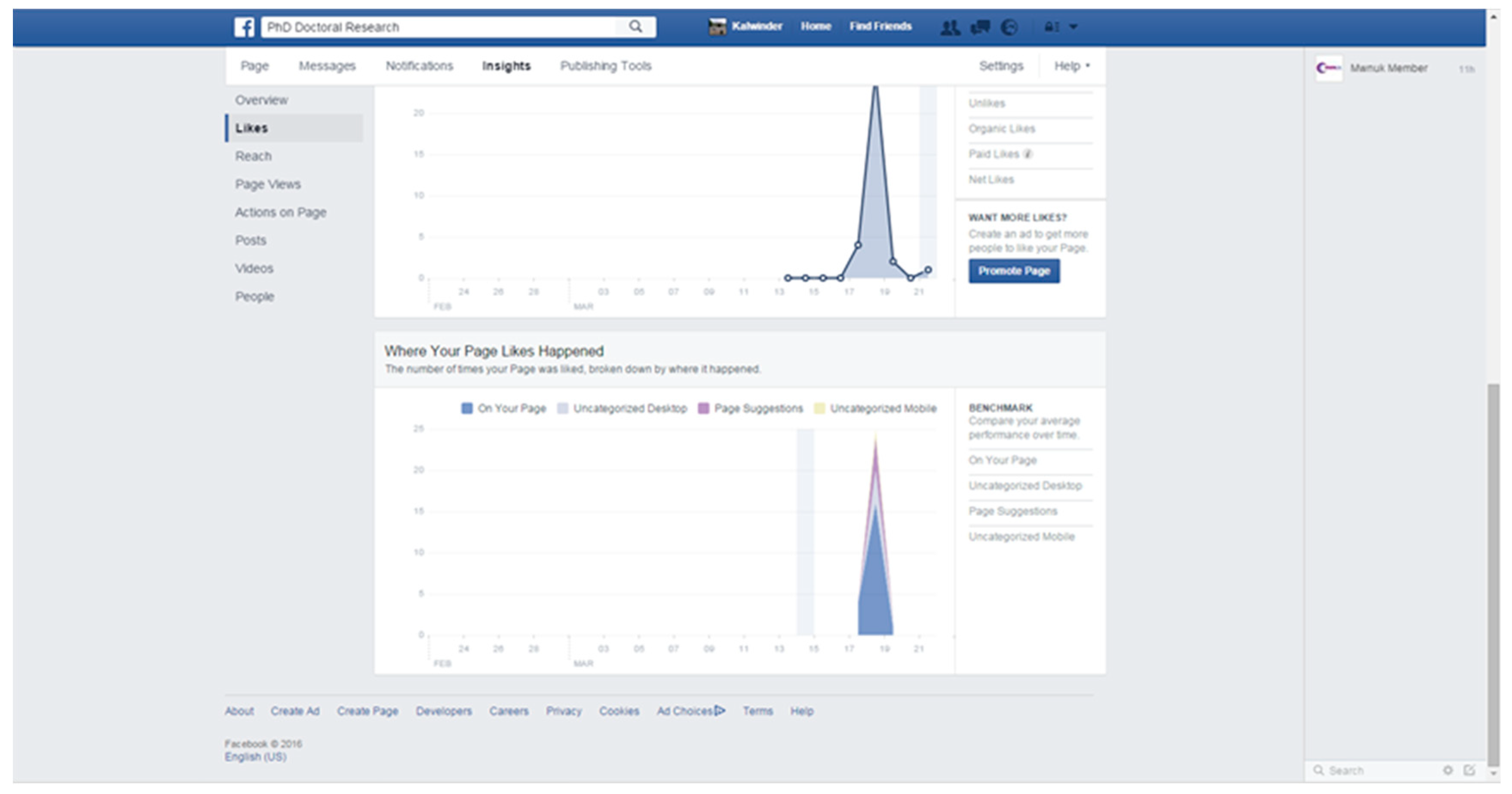

5.2. Monitoring the Reach of the Facebook Page

Once the page had been established A1 began to find out more about Facebook page functionality. The insights dashboard provided metrics on the extent of reach of the page and the demographics of those viewing and liking the page. It did not produce any identifiable information on those who viewed the page. The data showed that there were viewers from all over the world, mainly concentrated in the UK and in countries where English was the dominant spoken language. The gender profile showed that ‘women’ formed the majority of those who viewed the page. It showed the global reach of Facebook, which would not have been possible with non-digital recruitment. This information was useful for A1 to target posts on the timeline, to reach South Asian women in the UK. Posts about topical news items increased the reach and generated more activity on the page.

The user metrics showed that five weeks after the first post, the number of users who saw the post (known as the ‘reach’) was 560. The next day it had almost doubled to 993, and then 1098 a day after that. The number of ‘likes’ on the page had a similar trajectory. The power of Facebook to make research visible was evident from these data. The team quickly realised that using non-digital mechanisms could not ‘compete’ at this level and pace and were surprised by the speed of the number of people reached. We had not anticipated this and again attributed this to our own inexperience of Facebook and hence not having other data to compare. It was rewarding to see that the page had global reach, particularly to those countries that have a connection with the UK South Asian diaspora. The following screenshots show the extent of the likes on the Facebook page. The page was created on 13 March 2016.

Figure 1 shows the likes to the end of March.

Figure 2 shows the sources of the ‘likes’—those directly on the page and those who saw the page via other feeds.

5.3. Snowball Sampling

Facebook facilitated the use of the “snowballing sampling technique”, a method involving increasing the number of possible participants when current participants suggest and refer others whom they know meet the participant criteria and who may be interested in participating (

Abbott and McKinney 2013;

Biernacki and Waldorf 1981). It suits a research approach where the subject matter is sensitive (

Biernacki and Waldorf 1981) and where potential participants wish to remain anonymous (

Faugier and Sargeant 1997) due to their fear of stigma (

Noy 2008).

Without prompting, participants shared the post with other women whom they knew had also experienced GRV and who met the participant criteria. Forty percent of the total participants who took part in the research were recruited using Facebook, either directly or indirectly, via snowballing. The tool became a mechanism for women participants to control how much or how little they chose to engage with the research. The remaining sixty percent of participants were recruited via professional networks, such as professionals known to the researcher or through gatekeepers using non-digital methods. This mix of non-digital and digital recruitment mechanisms demonstrates that the intertwining of the two processes can be seamless and fluid without the need for a complete rethink of social methods. It also shows that digital recruitment can access participants that non-digital methods cannot, that is ‘the most marginalised of the marginalised’.

5.4. Rebalancing of Power

We found, unexpectedly, that participants actively engaged with the research project during the recruitment phase that went beyond finding out about the research, such as consenting and agreeing to be interviewed. Feminists have referred to the balances of power between researcher and researched (

Letherby 2003), where participants exercise their own choices in engagement with the research project (

Oakley 2016). Facebook gave participants more opportunities to engage and hence feel part of the research project. The women themselves chose what posts they wished to share and how much of their own identities they wanted to reveal on Facebook. For example, some participants chose to ‘like’ a post, comment on a post, or ‘like’ the page. We had no control over the participants’ engagement. In this way, Facebook facilitates the rebalancing of power between researcher and researched, which has not hitherto been explored, in depth, in research that deploys Facebook as a recruitment tool.

The use of Facebook to recruit research participants meant that the researchers were able to bypass the gatekeepers within agencies. There are many reasons for researchers to engage gatekeepers, most importantly to protect research participants from exploitation and disrespect from researchers (

Letherby and Bywaters 2007). The gatekeepers were local and national specialist domestic violence and sexual violence service providers, and they served as “metaphorical gates” with the power to decide if a victim receives their support for domestic violence (

Trinch 2007). Similarly metaphorical gates have the power over service users’ engagement with research or not. Actions such as not responding to requests and declining support for the research tended to come from service providers who had no historical relationship with the researchers and so may have been wary of trusting them (

Polanyi 2001).

This project’s use of Facebook for recruitment removed the metaphorical ‘gate’, essentially the power of agencies. Participants could access A1 and make direct contact. Participants who initiated contact via Facebook did so because they had been following the Facebook pages of domestic violence service providers, regardless of whether they themselves had been supported by these agencies or not.

Without the ‘safety net’ of the service provider or agency, the authors were even more aware of the issues associated with the safety and wellbeing of participants who had experienced domestic violence (

Maynard 1994). Specifically, those who had not engaged with agencies due to fear, stigma, of being judged, or being identified by their family or perpetrator (

Thiara 2013). The following message from a participant who was trying to engage other potential participants illustrates many women’s fears about coming forward for research on domestic violence and abuse:

![Socsci 12 00212 i007 Socsci 12 00212 i007]()

During the initial phone call, the participants were asked if they were able and willing to take part and were notified that they could withdraw from the research at any time. Some participants initially agreed and then changed their mind. Participants were provided with an information sheet at the interview that signposted them to relevant agencies and service providers where they could access support. All interviews except one, were conducted face to face. A video interview was not suggested nor considered by the research team nor the participants. With the advent of the increase in the use of video calling during the pandemic (

Statista 2022c), the option of video calling as well as face-to-face interviews would have been more readily discussed. The exception was when one participant had to cancel appointments several times. They lived a long distance from A1, although A1 would have travelled to interview them. The participant suggested a video call using Skype as they felt it would be more convenient for A1. Even though some of the functionality on offer today, such as ability to record Skype video calls, was not available then, it still proved to be successful.

The approach the participants took in contacting the researcher directly demonstrates that researchers can gain access to women who may be ‘invisible’ to, or ‘not reachable’ by, agencies.

Kruikow (

2022) questions whether the physical location of interviewing should continue to be the norm due to the everyday use of social media and how people, especially young users, find online ‘space’ most comfortable. Similarly, participants found safety, as well as comfort, in engaging directly with the researcher, which might not have been the case if they had been recruited via an agency. Despite these benefits, ethical considerations when using Facebook to recruit participants was kept under constant review by the researchers.

6. The Principles of Protecting Participants Online

The technical task of creating a Facebook page does not present many challenges and seems a simple and straightforward task. However, as soon as we started delving into the details, many unexpected ethical considerations became apparent and had to be addressed.

Social research methods have set out with a high regard for the emotional well-being, safety, and care of participants who have experienced domestic abuse and who participate in research on this sensitive subject (

British Sociological Association 2017). Such issues of informed consent, sensitivity, confidentiality, and anonymity to protect research participants (

Buchanan and Wendt 2018) are no less important when using Facebook. In fact, the use of technology by perpetrators to inflict domestic violence digitally (

Woodlock et al. 2020) was another important reason for keeping participants safe and for ensuring the anonymity of their online identity. Social media has become another forum for the perpetration of GRV, in the form of coercion, harassment, and the monitoring of women’s behaviour (

Reed et al. 2021), which extends to the perpetration of maintaining honour and inducing shame online, in the form of “honour-based content” (

Chetty and Alathur 2019).

As the study had not originally included the use of social media, a second ethics application was made to Coventry University Ethics Committee for the approval to recruit participants. The application centred on how useful Facebook would be to engage a wide audience, but also in ensuring the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants whilst using social media and through contact with the researcher.

7. Challenges

The original mission of social media and, specifically, Facebook, had been to increase social and business networks. However, over the years new ways of using social media have evolved and its use to recruit participants for research projects and building rapport is one of those. The purpose of this project’s use of Facebook was to increase reach, with the aim of recruiting as large a sample as possible, without having to build a social network of ‘friends’.

A1 had worked in the telecommunications industry as a software engineer. She contacted a former colleague who worked at Facebook to ask how to increase the reach of the page to attract participants. Their response was that the core aim of Facebook was to open up and encourage contacts between ‘friends’. This means the identity of each ‘friend’ is known. In this research, we wanted to attract participants but keep their identity confidential and not create a network of friends. The contact at Facebook found this to be an interesting problem and the researcher was directed to contact Facebook through formal channels. A1 contacted Facebook through these channels and spoke to someone who turned out to be a third-party subcontractor who, in turn, suggested that A1 contact Facebook and provided an email address by which to do this. Unfortunately, the email bounced back. A1 searched online to resolve this problem and found that search results regarding this email only focused on standard problems such as deactivating accounts. This interaction brought into question the actual contact researchers may have with the social media companies themselves and how they may regard suggestions/ideas/challenges faced that could feed into future versions of the software to facilitate researching vulnerable groups who need to be safe online.

Another challenge was how to respond to the paradox that Facebook users are encouraged to know the identity of persons in their network whilst, for this research, people’s identity had to remain anonymous for safety reasons. Creating a closed group was considered, but this would have resulted in members of the group knowing each other. On the suggestion of Facebook, a post was pinned to the timeline asking people to make contact by sending a message via Facebook Messenger.

Invisible Groups

The women in this study were socially invisible as they had defied social norms of arranged marriage, only to find their partner of choice was abusive. They were frightened and ashamed. They lived in isolation from their families and feared their family members would track them down (

Sandhu and Barrett 2020). This is why Facebook was used to reach out to participants. Facebook, together with robust ethical and research processes, provided a means for them to participate and minimise their risk of exposure and harm.

However, another group of participants remained invisible because they did not have the means, resources, or language capital to access technology. Often researchers provide a simplistic notion that “cultural dynamics” are at the heart of lack of engagement, particularly by Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) women with research in general and now with social media research (

Dunne et al. 2022). However, these studies are conducted without an analysis of the intersections of disadvantage that BAME women can experience. The intersectional lens provided by a GRV perspective shows how certain groups of women can be at a higher risk of violence. For example, women who are refugees or asylum seekers, or who have insecure immigration status, are at higher risk of violence due to institutional barriers (

Canning 2019;

Banga and Gill 2008). They may not wish to be visible if they are afraid of being deported, with English less likely to be their first language. They may not have access to the internet due to such barriers, or may be denied access, or cannot afford the technology. The intersection of gender, ethnicity, poverty, citizenship, and digital exclusion not only compounds their risk of violence, but also makes it harder to leave a violent relationship. These factors also increase their risk of remaining an ‘invisible group’ (that is a ‘marginalised marginal group’) with less access and opportunities to participate in research. This is a real challenge for the academy to remedy.

8. Positionality and Reflexivity

Charmaz (

2014, p. 13) positions the social reality of the researched and the researcher as constructed and therefore the “researcher’s position, their privileges, perspective, and interactions are an inherent part of the research reality. It, too, is a construction”. An important element within the research process is the researcher’s subjectivity (

Charmaz 2014). As a researcher, A1 shares a similar history with the participants. It was important to ensure that the participants respected the researcher.

Mirza (

2009, p. 5) refers to the positionality of a South Asian researcher who can give voice to the researched whose voices may otherwise be silenced. Despite the initial anonymity of A1′s identity on Facebook, subsequent interactions with the participants cultivated the shared heritage and positionality as South Asian women.

The use of Facebook became an aid to give voice to South Asian women who otherwise may not have been able to participate in or had not been aware of the research. The frequency and ease of sending messages via Facebook Messenger added to a familiarity that other forms of communication did not. There is an ease in sending a message and a distance that comes with use of Facebook Messenger that does not happen when talking on the telephone or via a video call. The women participants, through the use of Facebook Messenger, built up a trusting, researcher–researched relationship (

Letherby and Bywaters 2007) that started at the recruitment phase and thus became another huge benefit of digital recruitment over non-digital recruitment; in addition, it also further cemented the participants’ interactions with the researcher.

9. Conclusions

This paper has set out how to use Facebook in order to recruit research participants to a study before the COVID-19 pandemic (which subsequently prompted a widespread use of social media in social science research). However, it is still an area largely overlooked, even with the current prevalence in the use of social media in the research process. This paper explains that Facebook was used to reach out to a marginalised, and often invisible, group in UK society—South Asian women—who are often too frightened or ashamed to come forward due to experiences of specific forms of GRV, where the preservation of honour is highly valued in the community.

We demonstrated that the use of Facebook was both valid and ethical to ensure the safety of participants. It secured a wider reach of participants for the research into a sensitive subject area. We felt it important to detail the actual approach taken, including benefits and challenges with lessons learned, to show insights gained, and how there may have been times when we could have done things differently.

There are some downsides to using Facebook, especially concerning the safeguarding of participants who may be vulnerable. We therefore suggest that ethics processes are just as important when using social media for recruiting participants as when recruiting via non-digital means. Interaction with gatekeepers can be a challenge for researchers, as gatekeepers strive to protect their clients. However, participants themselves may not choose to engage via agencies and so if the hierarchy between researcher and researched is to be overcome, then the wishes and requests of the participants need to be focused upon as central to the research. None of the participants who were recruited via Facebook felt inhibited in talking about their experiences, they instead said that they found the process cathartic. One participant said they had found the interview draining but were glad that they had spoken about their experiences.

We have warned of the challenge to the academy that using digital technology to recruit research participants may create an additional “invisible marginalised group”; namely, those who, for whatever reason, cannot or do not want to access technology. Methodologically, the use of social media in recruitment should sit alongside non-digital traditional social research processes.

However, the use of Facebook has opened up the possibility of using social media, not just in the fieldwork phase, but also in recruiting invisible groups to research studies on sensitive topics such as GRV. Since undertaking this research, the use of Facebook has increased and the popularity of other social media such as Twitter and WhatsApp as a means to recruit participants and conduct qualitative research has grown. This is an ever-evolving area. As the use of digital technology and social media persists in everyday lives, then it only serves to further the field of research methodology and methods to include the use of technology in recruiting research participants. By describing the detail and lessons learned we hope that this paper will be a useful resource for researchers taking a similar research approach, regardless of their knowledge and practical experience of Facebook or any other social media. This paper has raised and discussed the ethical issues of using Facebook that researchers need to consider when looking to use online technology to recruit participants from marginalised communities.