Towards an Exploration of the Significance of Community Participation in the Integrated Development Planning Process in South Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Legislative Framework for Community Participation in the IDP

3. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

3.1. Theoretical Framework

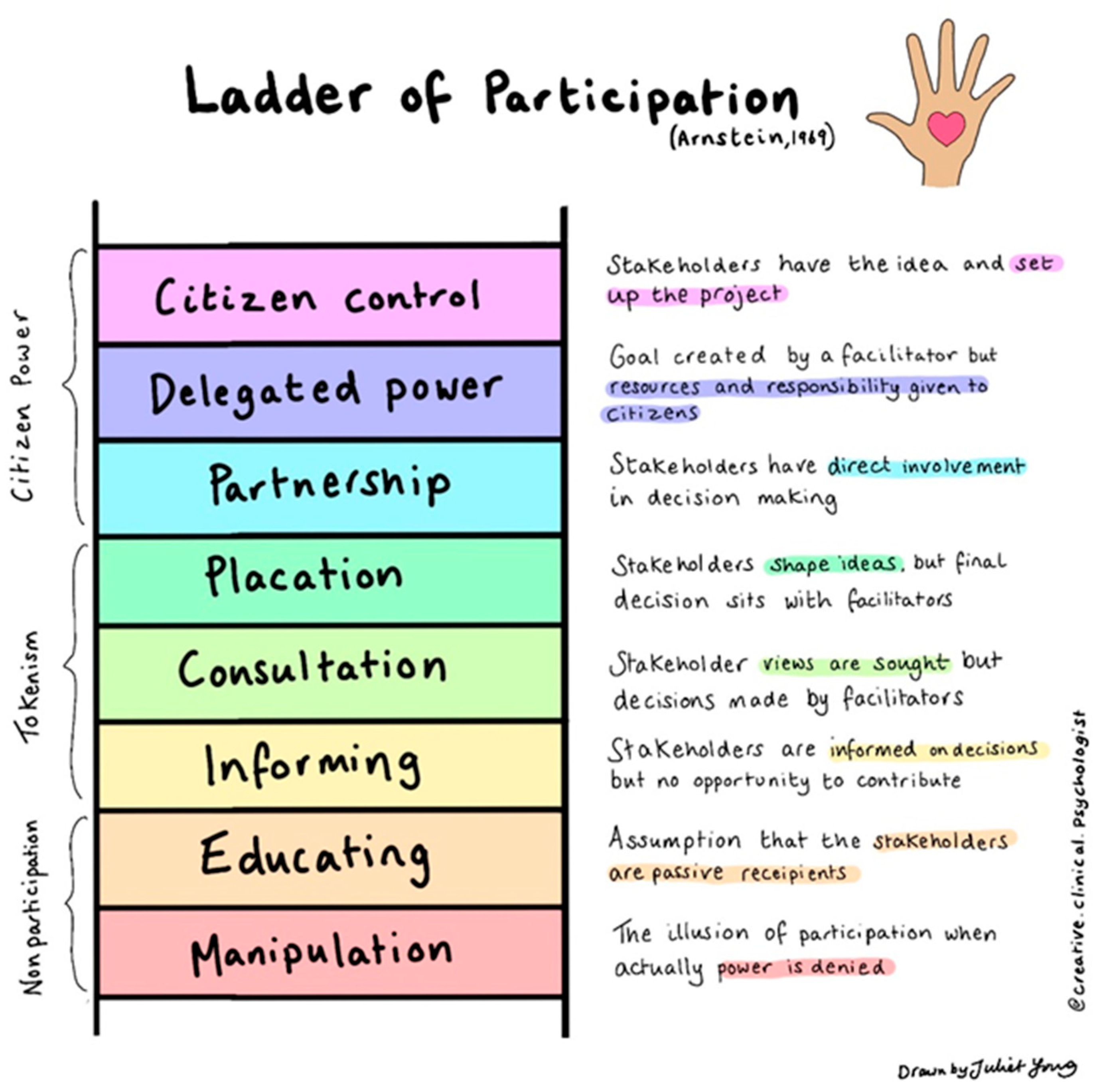

- Manipulation and therapy: “Both steps are non-participative. The aim is to cure or educate the participants. The proposed plan is best, and participation is to achieve public support through public relations. Instead of genuine citizen participation, the bottom step of the ladder indicates the distortion of participation in the public” (Arnstein 1969; Mamokhere and Meyer 2022).

- Informing: “A most significant first step to legitimate community participation. However, the emphasis is on a one-way flow of information too frequently. There is no channel for feedback and no power for negotiation” (Arnstein 1969).

- Consultation: “This is also a legitimate step attitude surveys, neighbourhood meetings and public enquiries. This further implies that inviting citizens’ opinions, like informing them, can be a legitimate step toward their full participation. However, when the consultation process is not combined with other modes of participation, this step of the ladder is still a shame since it offers no assurance that citizens’ concerns and ideas will be considered” (Arnstein 1969; Mamokhere and Meyer 2022).

- Placation: “Participation as placation occurs when citizens are granted a limited degree of influence in a process, but their participation is largely or entirely tokenistic: citizens are merely involved only to demonstrate that they were involved” (Arnstein 1969; Mamokhere and Meyer 2022). For instance, placation permits communities to advice or plan, but the authorities retain the power to judge the legitimacy or viability of the advice.

- Partnership: “In this step, the power is genuinely redistributed over negotiation among citizens and powerholders. Therefore, planning and decision-making responsibilities are shared”, for instance, through joint committees (Arnstein 1969; Mamokhere and Meyer 2022).

- Delegation: “The citizens hold a clear majority of seats on committees with delegated powers to make decisions. The public now has the power to assure accountability of the programme to them” (Arnstein 1969; Mamokhere and Meyer 2022).

- Citizen control: Participation as citizen control occurs when, according to Arnstein (1969); “residents can govern a program or an institution, be in full charge of policy-making and be able to negotiate the conditions, under which ‘outsiders’ may change them. In citizen-control situations, for instance, public funding would flow directly to a communities’ organisation, and that organisation would have full control over how that funding allocated” (Arnstein 1969; Gaber 2019).

3.2. Literature Review

4. Methods and Materials

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Target Population

4.3. Sampling

4.4. Data Collection

4.5. Data Analysis

4.6. Ethical Clearance

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Presentation of Quantitative Results

5.1.1. IDP Process and Desired Results

5.1.2. IDP Process, Community Participation and Accountability

5.1.3. Sense of Belonging and Empowerment

5.1.4. Democracy, Effectiveness and Responsiveness

5.2. Presentation of Qualitative Results

5.2.1. Benefits of Community Participation in the IDP Process

“To consult, negotiate and monitor service delivery”. He further indicated that “community participation in the IDP process affords communities with different benefits. The participation of communities in the IDP helps them develop problem-solving and decision-making skills, makes them take responsibility for their development, and ensures that the needs and problems are adequately addressed”.

“The advantage of including our community members in the IDP process is that the municipality will be able to recognise and understand the real needs and service delivery challenges and will be able to budget appropriately to address those needs and challenges”.

5.2.2. Accelerate Service Delivery, Promote Accountability, Community Participation, and Empowerment

“We agree with the narrative as the IDP assists in the identification of community needs and assists them in knowing what will be done when and where”.

5.2.3. Feedback to Communities

“Yes, the IDP report back sessions are done by Ward Councillors every quarter and the municipality provide reports through the Service Delivery Budget and Implementation Report (SDBIR)”.

5.2.4. Improvement of Community Participation in the IDP Process

“One of the challenges that we face as the municipality is lack of political willingness to participate in the IDP process. Thus, there is a need to improve the willingness of Councillors and Ward Committees”.

“The Greater Tzaneen Municipality should use comments, consultation sessions and report back sessions and public hearings to enhance participation”. Other Councillors and members of the Ward Committee go so far as to state, “Communities should be included from the start. As soon as the council has recognised a need for policy, it should inform the communities about it. The policy should be influenced by community involvement. For community involvement to be effective, residents must believe that their input will impact decision-making. In addition, communities should receive feedback on each consequence of their contributions, and transparency should be encouraged”.

6. Conclusions and Strategic Recommendations

- Community involvement should have an impact on municipal policies.

- The study found that democratic principles are still undermined. Thus, the study recommends that the Greater Tzaneen Municipality’s officials and politicians (councillors/ward committee members) should always uphold democratic principles as stated in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996, by ensuring active public participation, transparency, and accountable governance.

- The study also suggests that all municipal functions and activities should adhere to the Batho Pele principles as outlined in the White Paper on Local Government. A harmonious relationship between the municipality and its constituents may be ensured through the Batho Pele principles. Communities’ expectations for service delivery will be realistic thanks to efficient consultation and other Batho Pele principles. Communities, for instance, ought to be treated with respect in order to make them feel like they belong and have a say in municipal decisions. The municipality should continue to foster an atmosphere where all citizens feel a feeling of empowerment and belonging.

- The Greater Tzaneen Municipality and other South African municipalities, including those with service delivery backlogs, are acknowledged in the research. In order to make better use of their resources and improve the implementation of service needs, the study advises that the GTM build and innovate institutional and organizational skills. Therefore, the municipality should likewise give the delivery of services and the implementation of the IDP projects first priority when allocating its resources.

- Another difficulty the municipality encounters is a lack of political willingness to take part in the IDP process. Therefore, it is necessary to increase the willingness of the ward committees and ward councillors. In order to encourage ward councillors and ward committee members to actively participate in the IDP process as community representatives, the study advises that the municipality provide incentives for transportation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ababio, Ernest Peprah. 2004. Enhancing community participation in developmental local government for improved service delivery. Journal of Public Administration 39: 272–89. [Google Scholar]

- Act 117 of 1998. 1998. Municipal Structures Act of 1998; Pretoria: Government Printer.

- Act 2 of 2000. 2000. Promotion of Access to Information Act; Pretoria: Government Printer.

- Act 32 of 2000. 2000. Municipal Systems Act of 2000; Pretoria: Government Printer.

- Arnstein, Sherry. 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35: 216–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asha, Aklilu, and Kagiso Makalela. 2020. Challenges in the implementation of an integrated development plan and service delivery in Lepelle-Nkumphi Municipality, Limpopo Province. International Journal of Economics and Finance Studies 12: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, Arnold, and Troy Silima. 2006. Sampling and sampling design. Journal of Public Administration 41: 656–68. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Nancy, and Susan Grove. 2005. The Practise of Nursing Research: Conduct, Critique, and Utilization, 5th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier, p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- CoGTA. 2020. Municipal Ward Committees: What You Need to Know; Pretoria: Government Printer, March. Available online: https://www.cogta.gov.za/index.php/2020/03/20/municipal-ward-committees-need-know/ (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Dyum, Thami. 2020. The Extent of Public Participation in the Formulation of the IDP: The Case of Beaufort West. Master’s dissertation, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Dywili, Siyanda. 2017. The Role of Public Participation in the Integrated Development Planning Process: Chris Hani District Municipality. Eastern Cape: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10948/14983 (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Enwereji, Prince Chukwuneme, and Dominique Emmanuel Uwizeyimana. 2020. Enhancing Democracy through Public Participation Process during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review. Gender & Behaviour 18: 16873–88. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Kevin. 2019. South Africa’s Tools for Urban Public Participation. Urban Governance Paper Series. Available online: http://www.salga.org.za/Documents/Knowledge-products-per-theme/Plans-N-Strategies/Urban%20Governance%20Paper%20Series%20-%20Volume%201.pdf#page=38 (accessed on 17 April 2022).

- Gaber, John. 2019. Building “A Ladder of Citizen Participation”. Journal of the American Planning Association 85: 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaventa, John. 2004. Strengthening participatory approaches to local governance: Learning the lessons from abroad. National Civic Review 93: 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelo, Omar, Diana Braakmann, and Gerhard Benetka. 2009. Quantitative and qualitative research: Beyond the debate. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science 43: 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, Muhammed Yassin, Maya Korin, Faven Araya, Sayeeda Chowdhury, Patty Medina, Larissa Cruz, Trey-Rashad Hawkins, Humberto Brown, and Luz Claudio. 2022. Including the Public in Public eHealth: The Need for Community Participation in the Development of State-Sponsored COVID-19–Related Mobile Apps. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 10: e30872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Fakhrul. 2015. New Public Management (NPM): A dominating paradigm in public sectors. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations 9: 141–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kgobe, France Khutso Lavhelani, and John Mamokhere. 2021. Interrogating the effectiveness of public accountability mechanisms in South Africa: Can good governance be realised? International Journal of Entrepreneurship 25: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lachapelle, Paul, and Eric Austin. 2014. Community Participation. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Edited by J. B. Metzler. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 1073–78. [Google Scholar]

- Leboea, Alex Tsoloane. 2003. Community Participation through the Ward System: A Case Study in Ward 28, Maluti-a-Phofung Municipality. Doctoral dissertation, North-West University, Rustenburg, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan, Helen, and Sonja Schumacher. 2001. Research in Education. Virginia: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Mamokhere, John. 2019. An Exploration of Reasons behind Service Delivery Protests in South Africa: A Case of Bolobedu South at the Greater Tzaneen Municipality. Paper presented at International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives (IPADA), Johannesburg, South Africa, July 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Mamokhere, John. 2020. An assessment of reasons behind service delivery protests: A case of Greater Tzaneen Municipality. Journal of Public Affairs 20: e2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamokhere, John, and Daniel Francois Meyer. 2022. Including the excluded in the integrated development planning process for improved community participation. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science 11: 286–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamokhere, John, Mavhungu Elias Musitha, and Victor Mmbengeni Netshidzivhani. 2021. The implementation of the basic values and principles governing public administration and service delivery in South Africa. Journal of Public Affairs 22: e2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maserumule, Maserumule, and Mashupye Herbet. 2009. Good Governance in the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD): A Public Administration Perspective. Doctoral dissertation, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Mashamaite, Maijane Martha, and Paulus Hlongwane. 2015. Participatory Democracy and Decentralisation in South Africa: It’s Authenticity Towards Effective Public Service Delivery in Municipalities. The Xenophobic Attacks in South Africa: Reflections and Possible Strategies to Ward Them Off. Paper presented at South African Association of Public Administration and Management (SPAM), Polokwane, South Africa, October 7–9; p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- Mashamaite, Kgalema, and Andani Madzivhandila. 2014. Strengthening community participation in the Integrated Development Planning process for effective public service delivery in the rural Limpopo Province. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5: 225. [Google Scholar]

- Mathane, Letshego Patricia. 2013. The Impact of the Local Government Turnaround Strategy on Public Participation and Good Governance with Regards to the Integrated Development Planning Process: The Case of Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality. Doctoral dissertation, Central University of Technology, Bloemfontein, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Mathebula, Ntwanano. 2016. Community participation in the South African local government dispensation: A public administration scholastic misnomer. Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology 13: 185–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathebula, Ntwanano. 2018. Integrated development plan implementation and the enhancement of service delivery: Is there a link? Paper presented at International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives, Saldanha Bay, South Africa, July 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mathebula, Ntwanano, and Mokoko Sebola. 2019. Evaluating the integrated development plan for service delivery within the auspices of the South African municipalities. African Renaissance 16: 113–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaba, Kgoadi Eric. 2016. Community Participation in Integrated Development Planning of the Lepelle-Nkumpi Local Municipality. Master’s dissertation, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Molale, Tshepang Bright. 2019. Participatory communication in South African municipal government: Matlosana local municipality’s Integrated Development Plan (IDP) processes. Communicare: Journal for Communication Sciences in Southern Africa 38: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molosi, Keneilwe, and Kenneth Dipholo. 2016. Power relations and the paradox of community participation among the San in Khwee and Sehunong. Journal of Public Administration and Development Alternatives (JPADA) 1: 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Munzhedzi, Pandelani Harry. 2020. Evaluating the efficacy of municipal policy implementation in South Africa: Challenges and prospects. African Journal of Governance and Development 9: 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mushongera, Darlington, and Samkelisiwe Khanyil. 2019. Participation in Integrated Development Planning. Johannesburg: Gauteng City-Region Observatory. Available online: https://www.gcro.ac.za/outputs/map-of-the-month/detail/participation-integrated-development-planning/ (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Musyoka, Jason Muthama. 2010. Participation and Accountability in Integrated Development Planning: The Case of eThekwini Municipality’s Small Businesses Related Local Economic Development in the eThekwini Municipality. Master’s dissertation, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, Durban, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Ndevu, Zwelinzima. 2011. Making community-based participation work: Alternative route to civil engagement in the City of Cape Town. Journal of Public Administration 46: 1247–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, Gene, and Lynn Frewer. 2005. A typology of public engagement mechanisms. Science Technology, & Human Values 30: 251–90. [Google Scholar]

- Salkind, Neil. 2012. Exploring Research, 6th ed. Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa; 1996. Pretoria: Government Printer.

- The White Paper on Local Government; 1998. Pretoria: Government Printer.

- Thebe, Thapelo Phillip. 2016. Community participation: Reality and rhetoric in the development and implementation of the Integrated Development Plan (IDP) within municipalities of South Africa. Journal of Public Administration 51: 712–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tshabalala, Elizabeth Kotishana, and Antoinette Lombard. 2009. Community participation in the integrated development plan: A case study of Govan Mbeki municipality. Journal of Public Administration 44: 396–409. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, Susanne, and Florian Wenzel. 2017. Democratic Decision-Making Processes: Based on the ‘Betzavta’-Approach. Available online: https://www.studocu.com/row/document/azerbaycan-diplomatik-akademiyasi/non-profit-management/democratic-decision-making-processes/8492160 (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs. 2021. Participation. New York: United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/en/Intergovernmental-Support/Committee-of-Experts-on-Public-Administration/Governance-principles/Addressing-common-governance-challenges/Participation (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Van der Watt, Phia, and Lochner Marais. 2021. Implementing social and labour plans in South Africa: Reflections on collaborative planning in the mining industry. Resources Policy 71: 101984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Juliet. 2021. Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation. Available online: https://twitter.com/juliet_young1/status/1384604477697761281 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Yuwanto, Listyo, Rudy Handoko, and Ayun Maduwinarti. 2021. Implementation of Disaster Risk Reduction Policy: Moderating Effect of Community Participation. Journal of Public Policy and Administration 5: 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwane, Vusumuzi Zwelakhe Jacob. 2020. Community Participation in the Integrated Development Plan (IDP) of the Umzumbe Local Municipality. Master’s dissertation, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 51 | 12.8 |

| Agree | 62 | 15.5 |

| Strongly disagree | 69 | 17.2 |

| Disagree | 90 | 22.5 |

| Unsure | 128 | 32.0 |

| Total | 400 | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mamokhere, J.; Meyer, D.F. Towards an Exploration of the Significance of Community Participation in the Integrated Development Planning Process in South Africa. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050256

Mamokhere J, Meyer DF. Towards an Exploration of the Significance of Community Participation in the Integrated Development Planning Process in South Africa. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(5):256. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050256

Chicago/Turabian StyleMamokhere, John, and Daniel Francois Meyer. 2023. "Towards an Exploration of the Significance of Community Participation in the Integrated Development Planning Process in South Africa" Social Sciences 12, no. 5: 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050256