Abstract

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been emerging as a topic of significant interest, attracting the attention of the public and leading to an increase in research and on media coverage of this technology. This article examines how the Brazilian and Portuguese media represent AI in journalism and the challenges it poses. Using digital methods, this study analysed 60 news articles published between June 2022 and June 2024. The data were collected through an anonymous search on Google News, and the content was analysed using sentiment analysis with the PTNews software, followed by a similarity analysis using the Iramuteq software. The results show a predominantly positive sentiment towards AI in journalism, with 91.8% of articles highlighting its benefits, such as increased efficiency and the automation of routine tasks. However, concerns about disinformation, ethical implications, and the potential erosion of journalistic credibility were less emphasised. The analysis also identified key themes, including AI’s dual role as both an enabler and a threat to journalism, the importance of human oversight, and the challenges of newsroom adaptation. The findings suggest that the Brazilian and Portuguese media generally present AI as an opportunity for journalism, often downplaying the associated risks and ethical challenges.

1. Introduction

Recent developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI) have led to changes in all areas of society, including the media. The first debates on this technology date back to the 1940s, when a group of pioneering scientists questioned the possibility of computers simulating human thinking to solve problems. In 1956, AI officially became a field of research at a conference in Dartmouth, USA, organised by several scientists, including John McCarthy, Claude Shannon, and Marvin Minsky. Simultaneously, the application of mathematical and statistical knowledge to predict patterns in the English language, developed by Claude Shannon, significantly contributed to the strengthening of the field and to what we would later come to know as Large Language Models (LLMs), exemplified by software such as ChatGPT.

In the following decades, several computer scientists tried to replicate human reasoning in machines, with the aim of solving mathematical problems, planning actions, and even simulating board games (Russell and Norvig 2016). However, it was only in recent years that AI effectively entered people’s daily lives through its incorporation into smartphones and the internet (Canavilhas and Essenfelder 2022). Today, virtually every task we perform online is mediated by algorithms and AI, developed by tech companies such as Google, Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, and Apple, among others. The ubiquity of AI technologies in everyday life is one of the factors contributing to the growing public interest in AI, but it is not the only one.

The popularity of ChatGPT and the novelty of generative AI are also factors that increase public curiosity about this topic (Sanin 2023). This has contributed to citizens seeking more information and, as a result, the media beginning to produce more content on AI. Media interest in AI has grown steadily over the past decade, but stories about AI still account for a small proportion of daily news (Nguyen and Hekman 2022). The authors noted that the number of stories peaked in 2018 and then declined, suggesting a possible “hype cycle” similar to the earlier big data trend (Nguyen and Hekman 2022). However, with ChatGPT, a new “hype” has begun and this time the topic is still on the agenda, raising new questions.

The increased interest in AI has been accompanied by a growing use of AI systems in the media (Beckett and Yaseen 2023). Portuguese language models are being used in specialised media, such as the Portuguese sports website Zerozero.pt (Canavilhas and Gonçalves 2023), or in generalist television media, such as Brazil’s TV Globo (Pinto and Barbosa 2024). Thus, a gap in the literature has been identified: what do the Brazilian and Portuguese media say about the use of AI in journalism? What are the sentiments associated with this representation of AI? This study is guided by these research questions, which aim to analyse what challenges AI represents in contemporary journalism from the perspectives of Portuguese and Brazilian media outlets.

2. AI as an Opportunity for or a Threat to Journalism in Crisis

In recent decades, journalism has faced a structural crisis, characterised by the erosion of the traditional business model and the loss of editorial autonomy in the face of the growing influence of digital platforms (Cagé 2016). With the rise of the internet and social media, the media has been forced to adapt to the logic of platformisation, in which content is shaped and distributed according to the interests of large technological corporations (Anderson et al. 2012; Fígaro and Nonato 2017; Nieborg and Poell 2018; Beckett 2019).

It is in this context of platformisation that digital transformations and the introduction of AI technologies occur in journalism, marked by the commercial logic of the internet. The integration of AI technologies in newsrooms is deeply connected to “informational capitalism” (Castells 2000; Nieborg and Poell 2018), where information becomes a commodity and journalistic value is often redefined by performance and engagement metrics. Therefore, the use of AI in journalism could reinforce the commercial logic of platforms and technological dependency (Simon 2024) and pose a threat to the democratic function of journalism by compromising the quality of information and the diversity of voices in public debate (Wolton 2003).

On the other hand, the presence of automation and AI in the dynamics of communication cannot be ignored and could be an important opportunity for the media. The benefits described in the bibliography on the use of AI in journalism saves time and money: automating various tasks (e.g., transcribing interviews and translating content), improving content recommendations, speeding up the distribution of content on social media, writing news stories, helping journalists find stories, analysing large amounts of data, and so on (Beckett and Yaseen 2023; Lindén 2017). In this sense, AI can free journalists from routine tasks, help them spot fake news on social media faster, enable them to identify new stories from data sets, and expand the scope of news coverage.

Indeed, AI is currently in the “hype” phase of expectations (van Lente et al. 2013; Nguyen and Hekman 2022), as it is being presented on many fronts as the salvation of journalism, particularly with the recent popularity of ChatGPT and Gemini. At this stage, there is a widespread belief that technology will solve the crisis in the news industry, often without critical analysis of the risks involved. Technological enthusiasm is a recurring feature of digital transitions in journalism, where the focus is often on what technology can do rather than what it should do. This initial fascination can lead to uncritical adoption of technologies that do not necessarily improve the news ecosystem. And, as with earlier technologies, there is a period of experimentation and adaptation during which many issues need to be discussed.

Therefore, news organisations need to move beyond this “hype” and consider strategies for using AI wisely to improve journalism, increase efficiency, and enable the production of more relevant and higher quality content (Beckett 2019). There are limitations and challenges, such as algorithmic bias, ethical implications, and the risks of financial short-termism that can arise when technology is prioritised over journalistic principles. It is necessary to think how the use of AI can help newsrooms adapt to the new ecosystem without sacrificing the core values of journalism (Beckett 2019).

Issues of transparency, accountability, and editorial control come into conflict when these technologies are applied to editorial decision making and content production (Canavilhas and Biolchi 2024). Moreover, adapting journalism to AI requires profound changes in newsroom routines and in the training of professionals, who now need to master both traditional journalistic skills and new technological skills (Diakopoulos 2019; Helberger 2019; Tandoc et al. 2022). This process of adaptation is complex and not always homogeneous, leading to disparities between media and putting journalistic quality and credibility at risk.

Another challenge is fighting against disinformation and misinformation (Wardle 2019). Disinformation refers to the dissemination of false or inaccurate information with the intent to deceive, offend, or confuse, usually for ideological, political, or financial purposes, while misinformation is unintentional (Gonçalves et al. 2024). AI amplifies the problem of disinformation: it introduces new strategies for creating and spreading fake news and complicates the task of distinguishing truth from falsehood. The capacity of AI to generate deepfakes, manipulate information, and strategically disseminate false content to targeted audiences constitutes a significant threat to the credibility of journalism and erodes public trust in the media.

At the same time, the use of AI by journalists to produce and distribute news raises ethical issues, including the need to ensure the impartiality of algorithms and avoid biases that could distort coverage. For this, it is necessary to establish ethical standards adapted to this new reality (Forja-Pena et al. 2024), and news organisations are seeking clear guidelines for the responsible use of AI, recognising that without proper ethical regulation, trust in journalism could be undermined. Initiatives such as the European Union’s move in 2023 to establish a credible ethical framework to guide the industry are seen as essential steps to contain the challenges AI poses to journalism. In the media, Estadão and the BBC are pioneers in developing a code of recommendations for the use of AI. Both media outlets emphasise that “all decisions regarding the use of AI are determined by professionals, with ongoing review, monitoring, and updates ensured by specialised committees” (Canavilhas and Biolchi 2024, p. 60).

Another perspective is that the rise of AI technologies in journalism has sparked debates concerning the relationship between humans and machines in news production. According to Latar (2018), as automated content creation systems advance, machine-mediated communication is reshaping the journalistic field, raising questions about creativity, credibility, and the future of newsrooms. A central issue in the discussion on the use of AI in journalism is the question of creativity. Latar (2018) also highlights growing concerns about whether the “mind” of the machine could become more creative than the human. Although machines or computational algorithms are already present in the daily news production process, creativity is still regarded as an essentially human skill. In this context, the role of the journalist is not merely to produce information, but to interpret, analyse, and offer engaging narratives.

In the case of automated journalism, software performs tasks that were once exclusive to human journalists, such as writing news articles. This raises new questions about the definition of a communicator and how social relations evolve between humans and machines. Lewis et al. (2019) argue that a theoretical shift is required to understand the implications of AI in journalism, particularly regarding its impact on society and communication. Moreover, a fundamental issue is how automation affects credibility in journalism. The study conducted by Tandoc et al. (2020) revealed that when a news article is written by an algorithm, the public tends to attribute greater credibility to it.

With the hype surrounding ChatGPT and other Generative AI technologies, some studies (Pavlik 2023) have demonstrated the potential of these tools, and the literature reveals a growing interest in the development of tools or solutions through computational methods aimed at journalistic applications (Ioscote et al. 2024). This indicates a fascination with technology, whether through using available market options or exploring possible configurations, in the pursuit of efficiency or survival.

3. Materials and Methods

The main objective of this study was to analyse how the Brazilian and Portuguese media represent Artificial Intelligence (AI) in journalism and to analyse what challenges AI represents in contemporary journalism, from the perspective of Luso-Brazilian media outlets. This study aimed to answer the following secondary research questions: (1) Which positive or negative aspects of the use of AI in journalism are highlighted in the analysed content? (2) What conclusions can be drawn from the analysed content? The first hypothesis is that Brazilian and Portuguese media coverage emphasises the negative consequences of using AI in journalism. This hypothesis is based on studies that discuss the risks associated with this technology in journalism, particularly at an ethical and professional level (Dörr and Hollnbuchner 2017; Lindén 2017), the precariousness of the profession (Grohmann 2013; Fígaro and Nonato 2017), and the replacement of human labour (Latar 2018; Lewis et al. 2019). The second hypothesis is that the media fails to adequately address the challenges posed by advances in AI technologies to journalism, such as transparency (Canavilhas and Biolchi 2024), credibility (Wölker and Powell 2021) and the platformisation of journalism (Nieborg and Poell 2018).

This research covered the period from 30 June 2022 to 30 June 2024. This two-year timeframe was chosen because it includes the launch date of ChatGPT on 30 November 2022. The launch of ChatGPT marked a significant milestone in generative AI, contributing to the popularisation of AI within society (Sanin 2023), which in turn influenced media coverage.

Data were collected by conducting searches on an anonymised page in the Google browser using the string “inteligência artificial” (artificial intelligence) + “jornalismo” (journalism). This approach aligns with research on digital methods (Rogers 2017), using techniques that include a range of methods from computational and information sciences—such as crawling, scraping, indexing, and ranking—that have been adapted and further developed for the Web. These methods involve algorithms that assess relevance and authority, thereby suggesting information sources, much like Google’s well-known PageRank. “Google’s queries, together with its outputted site rankings, are considered as indicators of social trends” (Rogers 2017, p. 77). The author cautions against the effects of personalisation and the taxonomy of the Internet (Montaner et al. 2003) and advises careful consideration in query design to mitigate these effects, while acknowledging that it is not entirely possible to eliminate them.

Google was chosen as the search platform because it is the most widely used browser overall, with over 65% of internet users worldwide, 67% in Portugal, and 78% in Brazil (Statcounter GlobalStats 2024). With the aim of meeting the requirements of query design (Rogers 2017), the following search settings were applied: geolocation set to Brazil and Portugal, language set to Portuguese, content filtered for news, searches performed on an anonymous page to avoid result personalisation, and sorting by relevance. The search was conducted on 22 July 2024 and returned 4470 results in Portugal1 and 109,000 in Brazil2.

Since the initial search returned thousands of results, we considered Google’s relevance criteria (Google n.d.), which determine that the first pages display the most significant results for the search. Upon examining the results, we observed that from the fourth page onwards, the items displayed were no longer characterised as media outlets. Therefore, the results for Portugal included only news published by media outlets registered with the Portuguese Regulatory Authority for the Media (ERC—Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social). In the case of Brazil, where no equivalent regulatory body exists, the filtering considered media outlets that have a journalistic editorial board. We disregarded items that featured only a brief text accompanied by a video or audio, as it would not be possible to conduct a textual content analysis. The final selection of the sample resulted in 60 news items, with 30 from Portugal and 30 from Brazil, focusing on the most relevant results according to the criteria established by Google (n.d.). Google determines the PageRank of search queries by assessing various relevance factors. It evaluates whether keywords are present in significant locations on a page and interprets the intent behind the query by employing synonyms and related contexts. The quality and depth of the content are scrutinised, as well as the personalisation based on contextual factors such as location and search history. How recently the content was published and its relevance to the topic are also considered criteria for importance. Sites of high quality and reputable standing are prioritised, and the user experience, including page speed and security, is also considered. These criteria collectively enable Google to provide search results that are more pertinent and valuable (Google n.d.).

Data collection was facilitated by a form developed in Google Forms to standardise the extracted information, and the data were subsequently organised and visualised using Excel. The data collected included the following: title, subtitle, publication date, journalist’s name, URL, news genre (news, interview, chronicle, report, editorial, and note), content format (text, image, sound, and video), country, newspaper’s name, publisher, access (free or subscriber-only access), and hashtags.

The data were analysed qualitatively using similarity and co-occurrence analysis between words (Marchand and Ratinaud 2012) with Iramuteq software (http://www.iramuteq.org/, accessed on 22 July 2024). We chose Iramuteq because it is a freely available software that helps with the textual analysis and visualisation of categories to complement manual analysis (Camargo and Justo 2013).

Additionally, a sentiment analysis was conducted using the PTNews3 project, which was developed as part of the Project Curriculum Unit of the 1st Cycle in Computer Engineering at the University of Beira Interior, in the Department of Computer Science (Lázaro 2024). We decided to use this tool because it was previously adapted for the Portuguese language with Googletrans4, an API for Python, which is an added value for our study.

4. Results and Discussion

The sample consists of 60 news articles: 25 (42%) were published in 2023 and 35 (58%) in 2024. Although the timeframe covered the period from June 2022 to June 2024, no publications prior to 2023 were found, according to Google’s relevance criteria. This absence of publications before 2023 raises questions about the relevance criteria used by search engines, which may be influenced by factors such as search history, geolocation, and user language (Rogers 2017). In this case, where the research was carried out on an anonymous site, we believe that one of the decisive factors was also the timeline itself, since Google prioritises the most recent content over the oldest; only in this way can we justify the absence of content on the launch of ChatGPT, which was a key moment. Consequently, the absence of earlier publications underscores the potential biases and limitations inherent in these relevance filters, which can influence the accessibility and visibility of content from various historical periods.

The significance of digital methods was highlighted by Rogers (2017), who argued that there is a fundamental distinction between studying the results of a search engine and understanding the algorithmic issues that shape these results. When researching media through digital methods, the author notes a difference in the study of online culture, stating that “when reading and interpreting online social signals, the question is whether the medium or the media dynamics override the result” (Rogers 2017, p. 76). In this case, while Google’s relevance criteria may introduce biases by omitting results from 2022, we argue, in accordance with Rogers (2017), that these criteria still reflect trends in social searches on the topic.

We identified publications from 14 Brazilian and 9 Portuguese media outlets, with a particular focus on the Brazilian newspaper Folha de S. Paulo and the Portuguese newspaper Expresso, with six publications each. The prominence of these media may be linked to the fact that they are a national reference in both countries, but as this result depends on Google’ criteria, the prominence of these media may only be due to their high visibility in this search engine.

With regard to the type of access to the publications, it was found that 86.7% were freely accessible, while 13.3% were restricted to subscribers. Several studies show a gap between the topics that journalists prefer to talk about and those that readers like to read about (Boczkowski et al. 2011). The search for topics related to innovation and technology may be a way of achieving some convergence between thematic preferences, which is also why most news published is open access to attract more traffic to the newspaper’s website.

A further area of interest identified in the sample was the gender of the authors of the journalistic pieces, with a view to establishing whether there was any evidence of equity. “Women have been coding, doing data visualisation and data analysis, and working more generally in journalism technology just as long as men, albeit in smaller numbers” (Usher 2019, p. 19), but this work does not always have the same visibility as men’s, so it is important to analyse and discuss the gendered dimensions. Our sample revealed a balanced distribution of authorship, with 33.3% of the publications attributed to male authors and 31.7% to female authors. However, 35% of the publications lacked gender identification, with some only mentioning the name of the news agency (e.g., Agência Lusa).

Although it is important to analyse the distribution of authors, these data are not representative of gender equity, as the 60 news articles are a selection of all the content on AI in journalism published in Portuguese and Brazilian media outlets. In other words, it is not possible to conclude whether there is a culture of gender equality in the media in the sample. Nevertheless, the high percentage of publications without gender identification reveals a gap in information transparency. These data suggest that the media often republished news from agencies that were standardised and lacking in depth. This phenomenon may be due to a lack of time available to journalists for in-depth coverage of AI, or it may indicate a lack of expertise among journalists on the subject (Noain Sánchez 2022).

Regarding the main sections in which the topic of AI was addressed, there was a predominance of the Technology section, which accounted nine publications (15%), followed by the Media section with seven publications (11.7%), the Economy section with five publications (8.3%), and the World section with five publications (8.3%). It is relevant to mention that the articles in the Media section address various issues related to the impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on journalism, which are consistent with the literature in the field: transparency and regulation (Canavilhas and Biolchi 2024), adaptation in journalism (Diakopoulos 2019; Helberger 2019; Tandoc et al. 2022), disinformation (Kertysova 2018; Garriga et al. 2024), and ethics (Forja-Pena et al. 2024). Regarding ethics, it is often mentioned indirectly, as in the expression “charter of principles”, without being included in any title or subtitle, and appears as a residual issue. In this sense, we believe that ethical issues seem to be little explored in these contents. These discussions highlight the importance of media outlets establishing a clear agenda and understanding their audience to maintain relevance and address current challenges.

In terms of genre of the texts, a classification was conducted in accordance with the approach proposed by Marques de Melo and de Assis (2016). In the sample, 49 publications (89.7%) were classified as informative, while 11 (18.3%) were identified as opinion. The news format was the most prevalent within the informative genre, accounting for 42 publications, while six were reports, and only one was a brief note. In contrast, among the 11 opinion publications, 6 were articles, 4 were columns, and only 1 was a comment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of the sample by genre and format.

This distribution indicates a predominance of factual and news-oriented content about AI, to the detriment of critical analyses or editorial pieces. It should be noted, however, that the data are influenced by the algorithmic criteria employed by Google News. Therefore, it is not possible to assume that media outlets produce fewer opinion pieces about this theme.

In the sentiment analysis of the publications (N = 60), a positive sentiment prevails for both Brazilian and Portuguese media outlets. There were only four publications of the information genre that were considered negative by the PTNews software (https://www.ptsoftware.eu/en/, accessed on on 22 July 2024) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sentiment analysis of contents, classified with PTNews.

With AI being a new topic, journalists were forced to look for new sources, namely experts in the field and technical reports. That is why the positive trend in approaches to the subject of AI (91.8%) is not surprising. Firstly, this is because following the launch of a new technology there is always a spike in inflated expectations (Fenn and Raskino 2008) and the interviewees presented mainly positive perspectives. Only at a later stage do some moderation, frustration, and warnings about the dangers of its use begin to emerge. But this is also because several articles have been published following the release of reports on the subject and follow the tone of the documents themselves. A good example of this is the Future Today Institute’s 2023 Tech Trends: over 82 pages, the report analyses the potential application of AI in several areas, but always from a positive perspective. One of the few negative notes is when it says that “Commercial AI products could inadvertently incentivise bad behaviour” (Future Today Institute 2023, p. 10) and, even then, in a rather mild way.

Furthermore, looking at the trend of opinion articles, almost all of which are written by experts and all of which have a positive trend, the approaches in the news are equally positive, as they are the sources that journalists look to for their articles. Although the general sentiment of the opinion pieces is positive, they make a new contribution by introducing an interrogative tone to the discussion of AI in journalism, particularly in the titles “Will AI steal journalists’ jobs? Reflections on possible scenarios” (Malar 2024); “Asking doesn’t hurt: Should we be afraid of Artificial Intelligence?” (Shifter 2023); and “Journalism? Always and with journalists” (Lino 2024). This could be the beginning of an interest in discussing the impact of this tool on journalism, always with the positive belief that journalists are irreplaceable.

In the Brazilian sample, the only negative publication found was in the media outlet Extra. On 15 May 2024, Extra published an article about a new Google tool that uses AI to generate responses directly in search results. The executive president of the ANJ (National Association of Newspapers) expressed concerns about how this technology might impact the sustainability of journalism. He argues that by displaying AI-generated responses at the top of search results, the tool could reduce the visibility of news websites, potentially leading to a decline in traffic and, consequently, harming the economic health of journalism outlets. The article reflects a negative sentiment, highlighting the perceived threat posed by the new functionality to the media sector.

In the Portuguese sample, three publications, two from the Público and one from the Observador, were identified as negative in the sentiment analysis. The article published by Público on 23 June 2023 discusses a statement from Ramón Salaverría, coordinator of the Iberian Observatory of Digital Media and Disinformation. Salaverría argues that disinformation and AI are creating a particularly challenging and transformative phase for journalism. He advocates that journalists should intensify fact-checking from the very beginning of the news production process. The article published by Público on 16 February 2024 in the Ipsilon (cultural section) discusses how AI is causing significant upheaval in the photography industry. It explores concerns that AI is undermining the very foundations of photography, impacting both art and journalism. The article published by Observador on 7 September 2023 highlights UNESCO’s concern that AI has been adopted in schools and universities too swiftly, at a time when adequate regulation to protect user data and security is still lacking.

Despite the negative sentiment, issues related to the precarisation of journalistic work, as discussed by Grohmann (2013) and Fígaro and Nonato (2017), triggered by platform capitalism, are not adequately addressed. The possibility of replacing human journalists, already evidenced in the literature by authors such as Latar (2018) and Lewis et al. (2019), is discussed superficially, with greater emphasis placed on issues related to journalistic practice, such as ethics and transparency in the use of AI, rather than on the precarisation of journalists’ working conditions. This dimension, strained by platform logic and the pursuit of efficiency and cost reduction in journalism, leaves a gap that needs further exploration by the media.

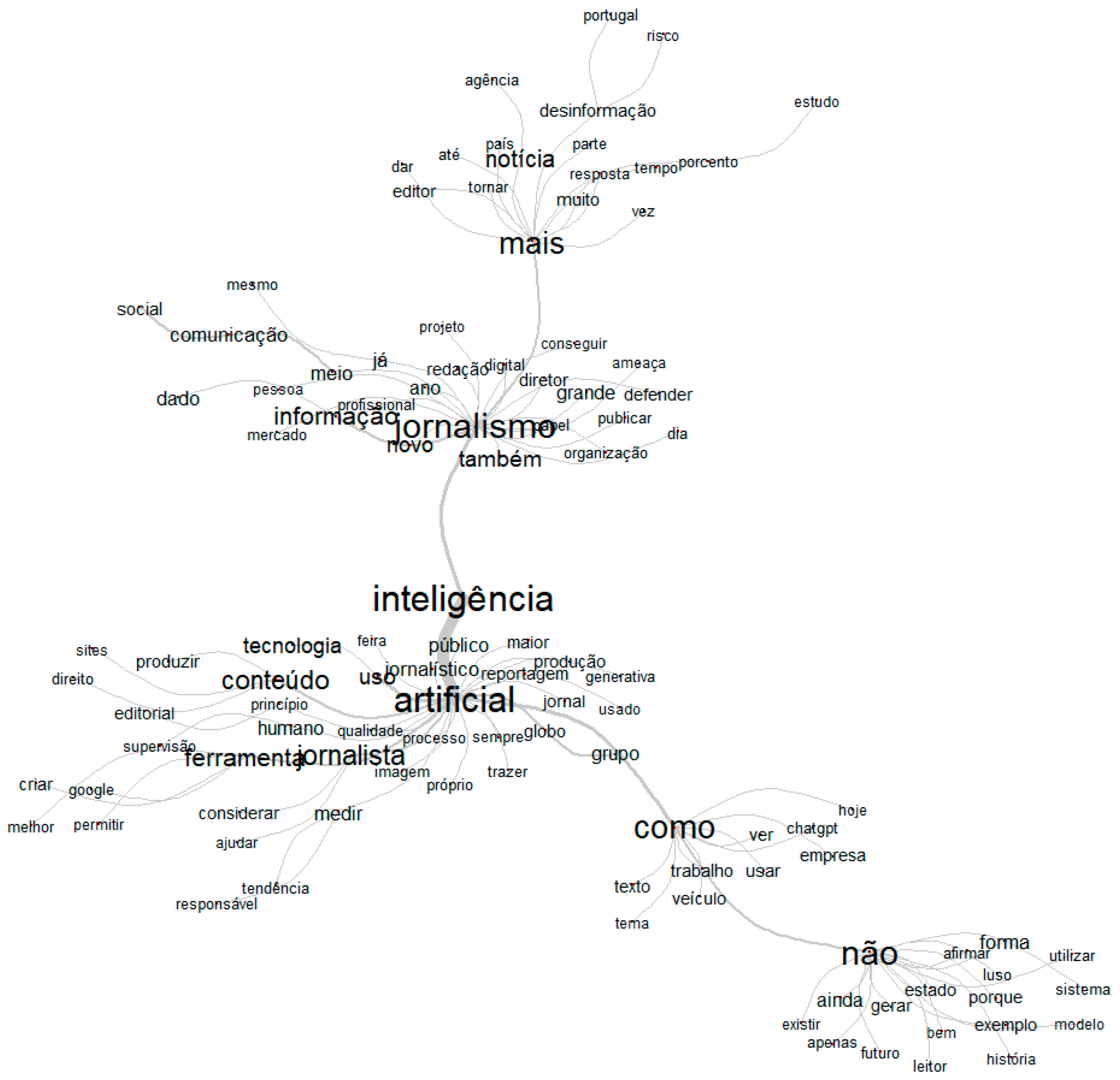

The content analysis follows a second approach with the help of Iramuteq software and similarity analysis. The Iramuteq software was employed to analyse data that enabled the identification of categories present in the sample, thus facilitating the construction of narratives aimed at gaining a comprehensive understanding of the perspectives on AI in journalism present in the sample. For a better understanding of the categories and possible narratives present in the sample, we chose to analyse only the informative genre, specifically news articles, which corresponds to 42 texts from the sample (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Similarity analysis of 42 news articles.

Following a vertical reading, from top to bottom, we identified five nodes that gave rise to five themes of analysis based on the words “more” (mais), “journalism” (jornalismo), “Artificial Intelligence” (Inteligência Artificial), “how” (como), and “no” (não). These words likely play a crucial role in the overall theme under discussion.

The first node “more” may be employed to connect ideas or elements, such as in “more information”, “more news”, and “more content”. In this context, this node functions to indicate an expansion or addition of something in relation to another term with which it co-occurs. It is possible to extract this reading from expressions such as “with artificial intelligence we have a catalyst that will produce much more content than humans can” (Kalil 2023). In other cases, the association between the words “more” and “time” fits in with what is one of the advantages most cited by research when it comes to integrating AI into newsrooms: freeing journalists from routine tasks (Lindén 2017). For example, “the researcher points out two possible ways of looking at AI. On the one hand, it can help journalists with “industrial tasks”, for example, in recording interviews, translating or writing summaries, giving them more time for the “creative side” of the profession (SIC Notícias e Lusa 2024).

In the same way, the association between “more” and “disinformation” reflects a need for more answers about how to use AI to combat disinformation and misinformation, something that is connected to the second node—“Journalism”—which is connected to “Information”, and highlighting again a potential concern with the quality of information, particularly in relation to the dissemination of news and disinformation (Flores-Vivar 2019). In this field, AI plays a dual role, with bots being used in production and propagation, as seen above, but also in combating disinformation, namely through the use of AI in verifying information (Gonçalves et al. 2024; Nakov et al. 2021). Some expressions show this perspective of duality, such as “disinformation and AI open a more transformative phase of journalism” (Santos 2023) and “technology has become more accessible after being used by industries” (Scire 2024).

In the second node “Journalism”, the relationship between technology and its potential threat to the journalistic profession emerges through its connection with the edges “threat” (ameaça), “person” (pessoa), “professional” (profissional), and “defend” (defender). This becomes evident in news such as “seeks to protect professional journalism” (Nalin 2023). Here, it is possible to invoke the issue of the human–machine relationship in journalism, as already discussed in the literature by authors such as Latar (2018), Lewis et al. (2019), and Tandoc et al. (2020).

The third node “Artificial Intelligence” is strongly associated with terms such as “content” (conteúdo), “journalism” (jornalismo), “tool” (ferramenta), and “technology” (tecnologia). Other words emerge associated with AI, such as “production” (produção), “create” (criar), and “generative” (generativa), emphasising the presence of generative AI in journalistic production processes. This confirms a trend towards the increasing use of intelligent systems in the production of news in media organisations around the world, seeking to improve efficiency (Beckett and Yaseen 2023; Simon 2024).

This is probably the most studied aspect of the relationship between journalism and Artificial Intelligence (Lindén 2017; Diakopoulos 2019; Beckett 2019; Lewis et al. 2019; Canavilhas and Essenfelder 2022) and is part of a trend that began with the Internet and then mobile devices. With the journalism sector experiencing a crisis, these new technologies start off as a possible solution to the problem, but in the medium–long term they end up being seen yet another problem that journalism needs to face.

The web has emerged as another means of reaching new audiences and has turned out to be the biggest threat to the paper press. Mobile devices seemed to be more of an opportunity to bring journalism to new audiences, but the fact that they are a personal channel has increased the public’s adherence to social networks, which now represents another threat to journalism in general. The same is true of AI, which can be an ally of journalism, but can also be a threat. These discussions can be illustrated by some expressions in the news: “Journalism can benefit from artificial intelligence” and “It’s not all roses and thorns when we talk about the application of AI to journalism” (Araújo 2024); “UNESCO warns against the use of artificial intelligence in schools and universities” (Agência Lusa 2023).

At this point, we also find a connection with words that refer us to some tensions with the use of AI in journalism, namely “principle” (princípio), “supervision” (supervisão), “human” (humano), and “responsable” (responsável). These words bring us back to discussions in the literature about the authorship and responsibility of AI-generated content (Montal and Reich 2018; Díaz-Noci 2020; Tandoc et al. 2020), the difficulty of applying the values and principles of journalism to the uses of AI (Komatsu et al. 2020), the need for human supervision, and the questions surrounding the effective role of the human/journalist and the machine in the new media ecosystem (Lewis et al. 2019). For example, one of the Portuguese news reports that the regulatory authority (ERC) has asked CNN to provide a “statement of principles” (+M 2024) on the use of AI, after the channel used this technology in a programme about the 2024 legislative elections.

The fourth node, “how”, appears to indicate discussions about the limitations or challenges in the use of AI in journalism, with terms such as “ChatGPT”, “text” (texto), “medium” (veículo), and “work” (trabalho) being associated. This node also emphasises questions about the use of LLMs and generative AI in news writing. Among the highlighted challenges are the hallucinations present in these technologies, which can lead to the generation of inaccurate or misleading information. Additionally, the costs involved in developing proprietary LLMs represent a significant obstacle for many news organisations, which may not have the resources necessary to invest in such technologies. Despite the challenges, some journalistic organisations, such as Bloomberg, have invested in the development of their own LLM, the BloombergGPT (Bloomberg 2023). According to one of the news stories, AI tools used by Brazilian media outlets “pose a number of risks to journalism, such as the promotion of disinformation, copyright infringement and lack of compensation for journalistic content” (Monteiro 2023).

In the fifth node, the term “no” (não) stands out, connected to the “how” (como) node within the sphere of challenges. Edges such as “future” (futuro), “use” (utilizar), “system” (sistema), “generate” (gerar), and “model” (modelo) may suggest discussions about the status of AI as a valuable technology for journalism. This perspective should be considered in conjunction with a positive sentiment towards AI in this context, present in several sentences, such as “I don’t see professional journalists being replaced by AI in the future” (Araújo 2024) and “There is no algorithm that can be a journalist and fight for freedom” (Albuquerque 2024).

The similarity analysis evidenced by the two most significant clusters, namely the nodes “Artificial Intelligence” and “Journalism”, provides reflections on two main points: (1) the possible pathways for journalism in a context of digital transformation and (2) the use of Artificial Intelligence as a tool to automate parts of the journalistic process, while emphasising the indispensable role of human oversight in ensuring both the quality and ethics of content production. Furthermore, these findings raise discussions on how such changes may reshape the dynamics of work in newsrooms and the relationship with the audience, as well as concerns regarding potential threats to the traditional role of journalists due to increasing automation. In particular, the news published by the Brazilian and Portuguese media outlets included in this sample present a predominantly positive sentiment towards these themes.

5. Conclusions

The arrival of a new technology is always a moment of great media interest, especially when it has a strong impact on society. Artificial Intelligence applications are not new technologies, but the launch of a specific product—ChatGPT—has sparked interest in the area and triggered hype. According to Tasioulas (2023), “we are living in the midst of a heady AI spring. It is marked by a profusion of hopes, dreams, and fantasies about the potential of AI-based technologies to make unprecedented advances in furthering our personal and collective ends” (p. 1).

With journalism experiencing a deep crisis that has led to thousands of redundancies, the emergence of a generative technology with the capacity to work autonomously and improve the news process has generated expectations in the sector, but also some fears. This is why this study sought to find out how Portuguese and Brazilian journalism analyse the role of AI in their own activity.

This paper sought to answer several questions by testing three hypotheses. The first was that the prevailing sentiment in the news was negative because this trend has a strong presence in research into ethical issues (Dörr and Hollnbuchner 2017) or in the growing precariousness of the profession due to the possible replacement of journalists by algorithms (Fígaro and Nonato 2017; Latar 2018; Lewis et al. 2019). However, the results show that AI in journalism is represented in a positive light (91.8%), thus contradicting the first hypothesis. The articles show that AI in journalism is associated with advantages, as demonstrated by the studies by Beckett (2019), Diakopoulos (2019), and Beckett and Yaseen (2023), including improvements in efficiency and the handling of large data sets. These authors argue that AI technologies can assist journalists in data-driven reporting, fact-checking, and even in generating content for routine news, allowing human journalists to focus on more investigative and creative tasks. The news, exemplified in this sample by Araújo (2024) and Albuquerque (2024), illustrates this positive feeling about AI in journalism.

The second hypothesis was more related to journalism’s ability to understand the challenges that AI poses to journalism, which is why the research focused mainly on articles with a negative sentiment (8.2%). Areas such as the impact of the use of AI on the already fragile credibility of the media (Wölker and Powell 2021), concerns about transparency (Canavilhas and Biolchi 2024), or the role of the platformisation of journalism (Nieborg and Poell 2018) were some of the concerns that were expected to be found.

The similarity analysis showed that the positive sentiment largely outweighs the negative aspects. Words such as “credibility” and “transparency”, often mentioned in scientific research because they can be negatively affected by AI, (Latar 2018; Diakopoulos 2019; Tandoc et al. 2020) never appear. Others, such as “disinformation”, appear in a positive light, in which AI is portrayed as a tool for combating, but not producing, disinformative content. Even platforms, which in the bibliography (Fígaro and Nonato 2017; Nieborg and Poell 2018; Grohmann 2020) appear as a threat, here appear associated with “more” (mais)—to produce more, be more efficient, and be more profitable, aligned with the capitalist logic of platforms. We can conclude that the Portuguese–Brazilian media evaluate the role of AI in journalism very positively but make invisible other aspects that academic research identified.

Although AI is an opportunity for journalism, particularly in the processing of data and automatic generation, it also poses threats to each of the news processes. Privacy risks arise from data collection, while the accuracy of AI-generated content can be compromised (Forja-Pena et al. 2024) due to hallucinations (Maleki et al. 2024).

Added to all this is the risk of Artificial Intelligence being used in activities currently carried out by humans. If in some situations it seeks to free journalists from routine and repetitive tasks (Wölker and Powell 2021), in other cases it is beginning to be used to replace journalists, both in production and presentation, using virtual anchors who present news services and interact with consumers, which once again raises ethical concerns.

Finally, if the economic fragility of the media has already substantially reduced creativity in journalistic work (Deuze 2019), the use of algorithms that simply reorganise information following standard journalistic routines will be a profound blow to an activity that will tend to be increasingly undifferentiated. With less diversity, journalism will become poorer, and its social relevance will tend to disappear.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The main limitations of this study are related to methodological choices. Firstly, the choice of the strings “AI” and “journalism” limits the search for journalistic articles containing both words. Secondly, the use of Google News as a search platform introduces limitations in terms of algorithmic criteria that highlight some content over others. The main limitation is related to the time period chosen (June 2022 to June 2024), as the first pages of Google News did not contain any news from 2022. This happened because the algorithm prioritises new publications. In the case of the content that was made available, the vast majority was open access, which was not an obstacle to the research.

For future research, we will add strings such as “regulation”, “ethics”, and “journalistic principles”, trying to understand if these words appear associated with negative feelings or potential difficulties for journalism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.C., F.I. and A.G.; methodology, J.C., F.I. and A.G.; software, F.I.; validation, F.I. and A.G.; formal analysis, J.C., F.I. and A.G.; investigation, F.I. and A.G.; resources, F.I. and A.G.; data curation, F.I.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C., F.I. and A.G.; writing—review and editing, J.C., F.I. and A.G.; visualisation, F.I.; supervision, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) through a PhD scholarship for Adriana Gonçalves (UI/BD/152717/2022) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES) through a PhD scholarship—Finance Code 001: Fabia Ioscote (88881.934176/2024-01).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Results (Portugal): https://goo.su/b63s2A (accessed on 22 July 2024). |

| 2 | Results (Brazil): https://goo.su/U3539p (accessed on 22 July 2024). |

| 3 | Four primary libraries were employed in this analysis: requests, jusText, NLTK and Googletrans. The requests library was used to obtain web page data via the URL of each news item. jusText was used to remove irrelevant content from web pages, such as navigation links, headers and footers, in order to focus on extracting the text of the news item. The SentimentIntensityAnalyzer module of the NLTK library was used to determine whether the text was positive, negative or neutral. However, as this library does not support analysing text in Portuguese, it was necessary to use the Googletrans library, which implements the Google Translate API, to translate the text (from Portuguese to English). |

| 4 | https://pypi.org/project/googletrans/ (accessed on 22 July 2024). |

References

- +M. 2024. Regulador exige à CNN “carta de princípios” sobre uso de inteligência artificial. Sapo. April 30. Available online: https://eco.sapo.pt/2024/04/30/regulador-exige-a-cnn-carta-de-principios-sobre-uso-de-inteligencia-artificial/ (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Agência Lusa. 2023. UNESCO alerta para uso da Inteligência Artificial nas escolas e nas universidades. September 7. Available online: https://observador.pt/2023/09/07/unesco-alerta-para-uso-da-inteligencia-artificial-nas-escolas-e-nas-universidades/ (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Albuquerque, Mariana. 2024. Não há algoritmo que se faça jornalista e lute pela liberdade. June 2. Available online: https://www.jn.pt/1811222451/nao-ha-algoritmo-que-se-faca-jornalista-e-lute-pela-liberdade/ (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Anderson, C. W., Emily Bell, and Clay Shirky. 2012. Post-Industrial Journalism: Adapting to the Present. Tow Center for Digital Journalism. Available online: https://crowdfundingpr.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/the-future-changing-landscape-of-journalism.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Araújo, Pedro. 2024. Jornalismo pode ganhar com a inteligência artificial. Jornal de Notícias. March 18. Available online: https://www.jn.pt/5437264344/jornalismo-pode-ganhar-com-a-inteligencia-artificial/ (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Beckett, Charles. 2019. New powers, new responsibilities. In A Global Survey of Journalism and Artificial Intelligence. London: London School of Economics. Available online: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/polis/2019/11/18/new-powers-new-responsibilities/ (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Beckett, Charles, and Mira Yaseen. 2023. Generating Change: A global survey of what news organizations are doing with AI. Journalism AI, Polis, Department of Media and Communications, The London School of Economics and Political Science. Available online: https://www.journalismai.info/research/2023-generating-change (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Bloomberg. 2023. Introducing BloombergGPT, Bloomberg’s 50-Billion Parameter Large Language Model, Purpose-Built from Scratch for Finance. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/company/press/bloomberggpt-50-billion-parameter-llm-tuned-finance/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Boczkowski, Pablo, Eugenia Mitchelstein, and Martin Walter. 2011. Convergence Across Divergence: Understanding the Gap in the Online News Choices of Journalists and Consumers in Western Europe and Latin America. Communication Research 38: 376–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagé, Julia. 2016. Saving the Media: Capitalism, Crowdfunding, and Democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, Brigido Vizeu, and Ana Maria Justo. 2013. Tutorial para uso do software de análise textual IRAMUTEQ, 26 mar. 2013. Iramuteq. Available online: https://bit.ly/2wDAHtR/ (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Canavilhas, João, and Adriana Gonçalves. 2023. Produção de texto automático no jornalismo desportivo português: Estudo exploratório do Prosebot/Zerozero.pt. Methaodos Revista De Ciencias Sociales 11: m231102n03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavilhas, João, and Bárbara Biolchi. 2024. Inteligência Artificial e Transparência no Jornalismo. Mídia E Cotidiano 18: 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavilhas, João, and Renato Essenfelder. 2022. Apocalypse or Redemption: How the Portuguese media cover artificial intelligence. Total Journalism: Models, Techniques and Challenges 97: 255–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel. 2000. Fim de Milênio. Sao Paulo: Paz e Terra. [Google Scholar]

- Deuze, Mark. 2019. On creativity. Journalism 20: 130–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakopoulos, Nicholas. 2019. Automating the News: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Media. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Noci, Javier. 2020. Artificial intelligence systems-aided news and copyright: Assessing legal implications for journalism practices. Future Internet 12: 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörr, Konstantin, and Katharina Hollnbuchner. 2017. Ethical challenges of algorithmic journalism. Digital Journalism 5: 404–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, Jackie, and Mark Raskino. 2008. Mastering the Hype Cycle: How to Choose the Right Innovation at the Right Time. Brighton: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fígaro, Roseli, and Claudia Nonato. 2017. Novos arranjos econômicos alternativos para a produção jornalística. Contemporânea: Revista de Comunicação e Cultura 15: 47. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Vivar, Jesús. 2019. Inteligencia artificial y periodismo: Diluyendo el impacto de la desinformación y las noticias falsas a través de los bots. Doxa Comunicación 29: 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forja-Pena, Tania, Berta García-Orosa, and Xosé López-García. 2024. The Ethical Revolution: Challenges and Reflections in the Face of the Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Digital Journalism. Communication & Society 37: 237–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Future Today Institute. 2023. Future Today Institute’s 2023 Tech Trends. Available online: http://www.futuretodayinstitute.com/trends (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Garriga, Miriam, Raquel Ruiz-Incertis, and Raúl Magallón-Rosa. 2024. Artificial intelligence, disinformation and media literacy proposals around deepfakes. Observatorio (OBS*) Journal 18: 175–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, Adriana, Luísa Torre, Florence Oliveira, and Pedro Jerónimo. 2024. AI and Automation’s Role in Iberian Fact-checking Agencies. Profesional de la Información 33: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google. n.d. How Search Works. Available online: https://www.google.com/intl/pt/search/howsearchworks/how-search-works/ranking-results/#relevance (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Grohmann, Rafael. 2013. O trabalho dos jornalistas como sintoma da lógica dos conglomerados. Revista Alterjor 8: 101–15. [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann, Rafael. 2020. Plataformização do trabalho: Entre dataficação, financeirização e racionalidade neoliberal. Revista Eletrônica Internacional de Economia Política da Informação da Comunicação e da Cultura 22: 106–22. [Google Scholar]

- Helberger, Natali. 2019. On the democratic role of news recommenders. Digital Journalism 7: 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioscote, Fabia, Adriana Gonçalves, and Claudia Quadros. 2024. Artificial Intelligence in Journalism: A Ten-Year Retrospective of Scientific Articles (2014–2023). Journalism and Media 5: 873–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalil, Caroline. 2023. Inteligência artificial: Os chatbots podem substituir os jornalistas? Metrópoles. June 3. Available online: https://www.metropoles.com/colunas/claudia-meireles/inteligencia-artificial-os-chatbots-podem-substituir-os-jornalistas (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Kertysova, Katarina. 2018. Artificial Intelligence and Disinformation How AI Changes the Way Disinformation is Produced, Disseminated, and Can Be Countered. Security and Human Rights 29: 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, Tomoko, Marisela Gutierrez Lopez, Stephann Makri, Colin Porlezza, Glenda Cooper, Andrew MacFarlane, and Sondess Missaoui. 2020. AI should embody our values: Investigating journalistic values to inform AI technology design. Paper presented at 11th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Shaping Experiences, Shaping Society, Tallinn, Estonia, October 25–29; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latar, Noam Lemelshtrich. 2018. Robot Journalism: Can Human Journalism Survive? Singapore: World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Lázaro, Gabriel. 2024. PTNews: Levering NLP for News Article Analysis. Unpublished Final Degree Report. Covilhã: University of Beira Interior. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Seth C., Andrea L. Guzman, and Thomas R. Schmidt. 2019. Automation, journalism, and human–machine communication: Rethinking roles and relationships of humans and machines in news. Digital Journalism 7: 409–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindén, Carl-Gustav. 2017. Algorithms for journalism: The future of news work. The Journal of Media Innovations 4: 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, Conceição. 2024. Jornalismo? Sempre e com jornalistas. Sic Notícias. January 22. Available online: https://sicnoticias.pt/pais/2024-01-22-Jornalismo--Sempre-e-com-jornalistas-d0d34a2c (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Malar, João Pedro. 2024. A IA vai roubar o trabalho de jornalistas? Reflexões sobre cenários possíveis. Observatório da Imprensa. February 8. Available online: https://www.observatoriodaimprensa.com.br/inteligencia-artificial/a-ia-vai-roubar-o-trabalho-de-jornalistas-reflexoes-sobre-cenarios-possiveis/ (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Maleki, Negar, Balaji Padmanabhan, and Kaushik Dutta. 2024. AI Hallucinations: A Misnomer Worth Clarifying. arXiv arXiv:2401.06796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, Pascal, and Pierre Ratinaud. 2012. “L’analyse de similitude appliquée aux corpus textuels: Les primaires socialistes pour l’élection présidentielle française (septembre-octobre 2011).” Actes des 11eme Journées internationales d’Analyse statistique des Données Textuelles. JADT 2012: 687–99. [Google Scholar]

- Marques de Melo, José, and Francisco de Assis. 2016. Gêneros e formatos jornalísticos: Um modelo classificatório. Intercom: Revista Brasileira de Ciências da Comunicação 39: 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montal, Tal, and Zvi Reich. 2018. The death of the author, the rise of the robo-journalist: Authorship, bylines, and full disclosure in automated journalism. In The Routledge Handbook of Developments in Digital Journalism Studies. New York: Routledge, pp. 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Montaner, Miquel, Beatriz López, and Josep Lluís De La Rosa. 2003. A taxonomy of recommender agents on the internet. Artificial Intelligence Review 19: 285–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, Thaís. 2023. Como jornais e revistas estão incorporando inteligência artificial? Meio & Mensagem. September 6. Available online: https://www.meioemensagem.com.br/midia/jornais-revistas-inteligencia-artificial (accessed on 4 August 2024).

- Nakov, Preslav, David Corney, Maram Hasanain, Firoj Alam, Tamer Elsayed, Alberto Barrón-Cedeño, Paolo Papotti, Shaden Shaar, and Giovanni Da San Martino. 2021. Automated fact-checking for assisting human fact-checkers. arXiv arXiv:2103.07769. [Google Scholar]

- Nalin, Caroline. 2023. ChatGPT e jornalismo são tema de debate: Veja o que dizem especialistas. O Globo. May 4. Available online: https://oglobo.globo.com/rio/web-summit-rio/noticia/2023/05/chatgpt-e-jornalismo-sao-tema-de-debate-veja-o-que-dizem-especialistas.ghtml (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Nguyen, Dennis, and Erik Hekman. 2022. The news framing of artificial intelligence: A critical exploration of how media discourses make sense of automation. AI & Society 39: 437–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieborg, David, and Thomas Poell. 2018. The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media & Society 20: 4275–92. [Google Scholar]

- Noain Sánchez, Amaya. 2022. Addressing the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Journalism: The perception of experts, journalists and academics. Communication & Society 35: 105–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlik, John. 2023. Collaborating with ChatGPT: Considering the implications of generative artificial intelligence for journalism and media education. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 78: 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, Moisés Costa, and Suzana Oliveira Barbosa. 2024. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Brazilian Digital Journalism: Historical Context and Innovative Processes. Journalism and Media 5: 325–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Richard. 2017. Foundations of digital methods. Query Design. In The Datafied Society: Studying Culture Through Data. Edited by Mirko Schaefer and Karin van Es. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Stuart, and Peter Norvig. 2016. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. London: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Sanin, Cesar. 2023. Artificial Intelligence: Current Perspectives and Alternative Paths. TecnoLógicas 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Samuel. 2023. Ramón Salaverría: Desinformação e IA abrem fase mais transformadora do jornalismo. Público. June 23. Available online: https://www.publico.pt/2023/06/23/sociedade/noticia/ramon-salaverria-desinformacao-ia-abrem-fase-transformadora-jornalismo-2054207 (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Scire, Sarah. 2024. Relatório mostra avanço da IA nas redações jornalísticas. Poder 360. February 26. Available online: https://www.poder360.com.br/nieman/relatorio-mostra-avanco-da-ia-nas-redacoes-jornalisticas/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Shifter. 2023. Perguntar Não Ofende: “Devemos temer a Inteligência Artificial?”. Shifter. February 10. Available online: https://shifter.pt/2023/02/inteligencia-artificial-perguntar-nao-ofende-podcast/ (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- SIC Notícias e Lusa. 2024. Inteligência Artificial nos media é uma questão “impossível de ignorar”. Sic Notícias. January 14. Available online: https://sicnoticias.pt/mundo/2024-01-14-Inteligencia-Artificial-nos-media-e-uma-questao-impossivel-de-ignorar-1de538c1 (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Simon, Felix. 2024. Artificial Intelligence in the News How AI Retools, Rationalizes, and Reshapes Journalism and the Public Arena. Columbia Journalism Review 1: 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Statcounter GlobalStats. 2024. Browser Market Share Worldwide. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/browser-market-share (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Tandoc, Edson, Lim Jia Yao, and Shangyuan Wu. 2020. Man vs. Machine? The Impact of Algorithm Authorship on News Credibility. Digital Journalism 8: 548–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, Edson, Shangyuan Wu, Jessica Tan, and Sofia Contreras-Yap. 2022. What is (automated) news? A content analysis of algorithm-written news articles. Revista Media & Jornalismo 22: 103–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasioulas, John. 2023. The rule of algorithm and the rule of law. Vienna Lectures on Legal Philosophy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, Nikki. 2019. Women and technology in the newsroom: Vision or reality from data journalism to the news startup era. In Journalism, Gender and Power. London: Routledge, pp. 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- van Lente, Harro, Charlotte Spitters, and Alexander Peine. 2013. Comparing technological hype cycles: Towards a theory. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 80: 1615–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, Claire. 2019. “Understanding Information Disorder.” First Draft News. Available online: https://www.rcmediafreedom.eu/Resources/Manuals/Understanding-Information-Disorder (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Wolton, Dominique. 2003. Internet, e depois? Sao Paulo: Sulina. [Google Scholar]

- Wölker, Anja, and Thomas E. Powell. 2021. Algorithms in the newsroom? News readers’ perceived credibility and selection of automated journalism. Journalism 22: 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).