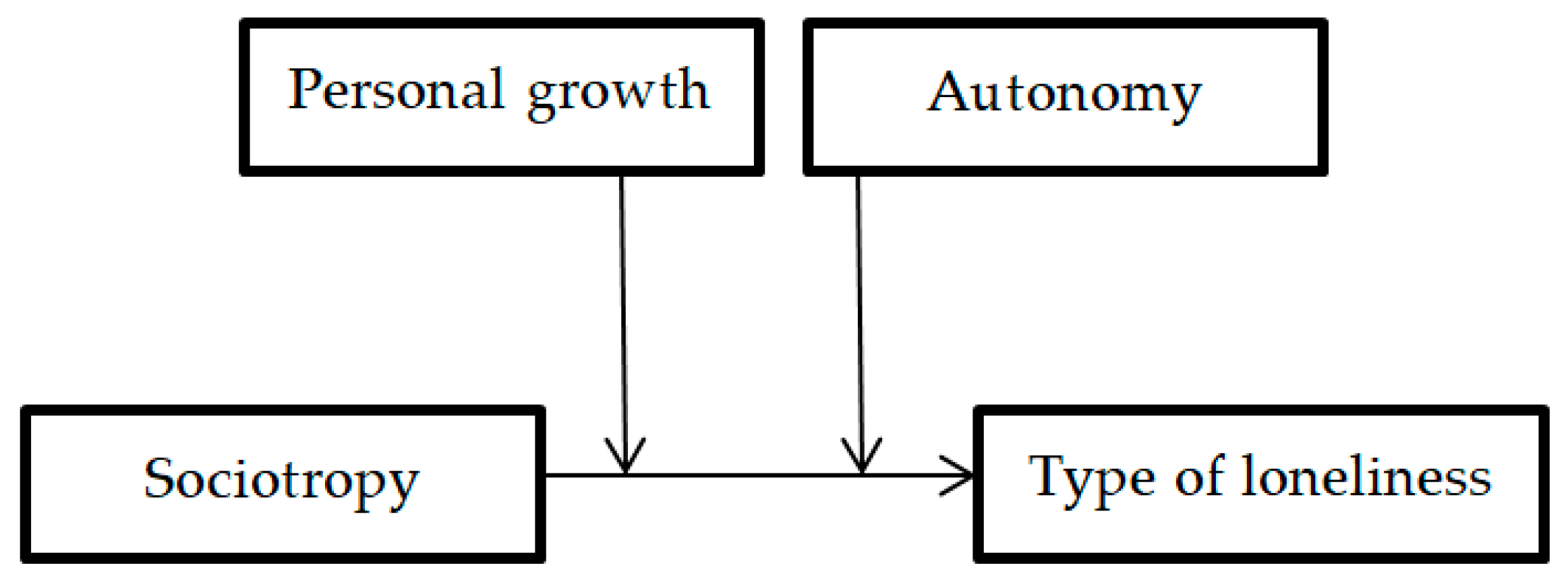

Moderation Effects of Autonomy and Personal Growth on the Association of Sociotropy and Different Types of Loneliness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Research Design

- (1)

- Are there differences in associations of sociotropy, loneliness and characteristics of psychological well-being if we approach loneliness from family and non-family perspectives?

- (2)

- Would the moderation mechanisms for family and non-family loneliness be similar?

- (3)

- Would gender affect moderation results?

- (a)

- In our previous studies, we found that sociotropy was associated with general loneliness and psychological well-being (Strizhitskaya et al. 2024), particularly with autonomy and personal growth, so we expected to find moderation effects for association between sociotropy and family and non-family loneliness as well;

- (b)

- We supposed that moderation mechanisms for associations of sociotropy and family and non-family loneliness could differ;

- (c)

- Finally, we hypothesized that men and women could differ in terms of the effects.

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

- (1)

- Sociotropy predicted family loneliness and was moderated by autonomy.

- (2)

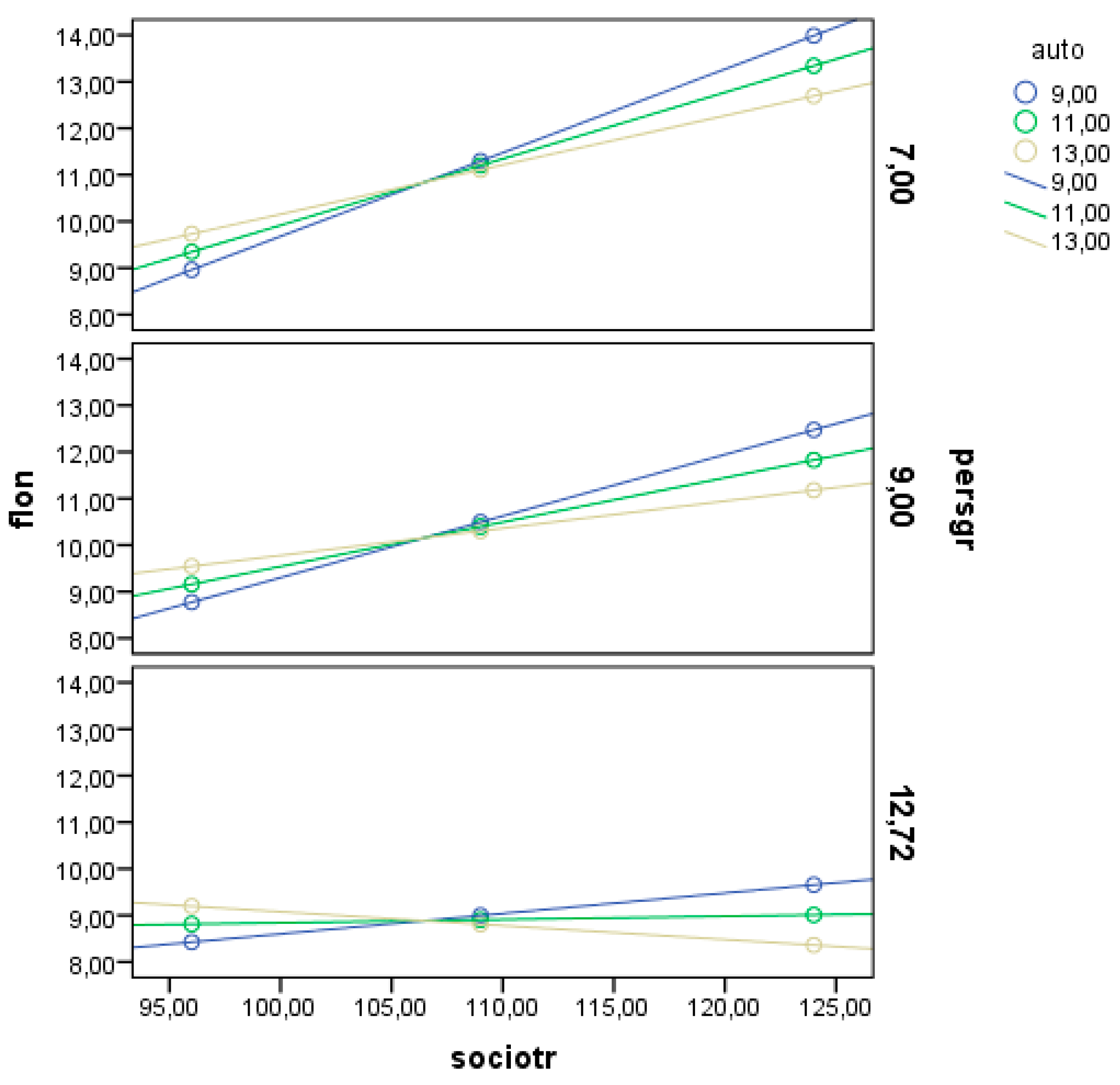

- Sociotropy predicted family loneliness and was moderated by personal growth.

- (3)

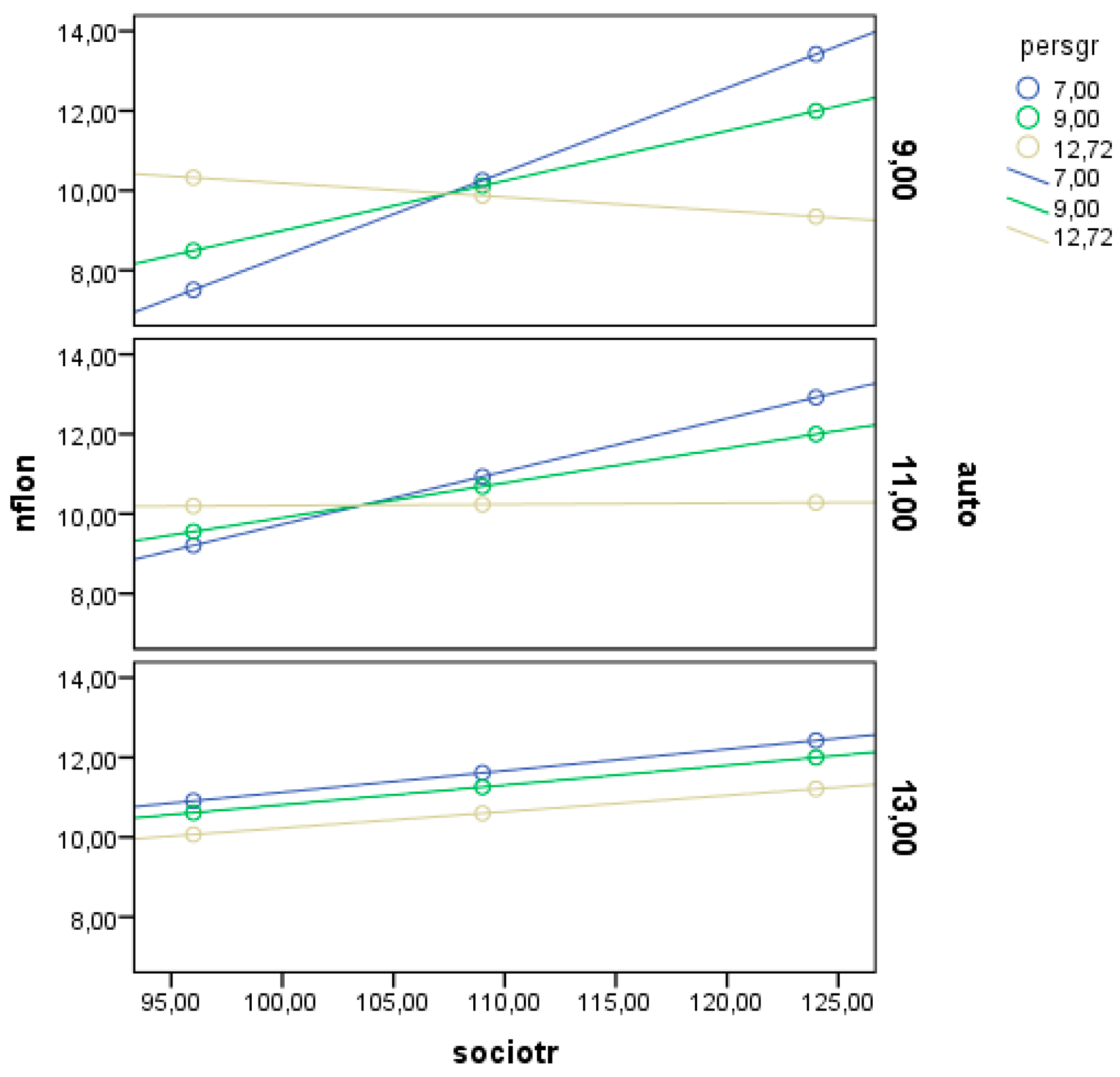

- Sociotropy predicted non-family loneliness and was moderated by autonomy.

- (4)

- Sociotropy predicted non-family loneliness and was moderated by personal growth.

- (5)

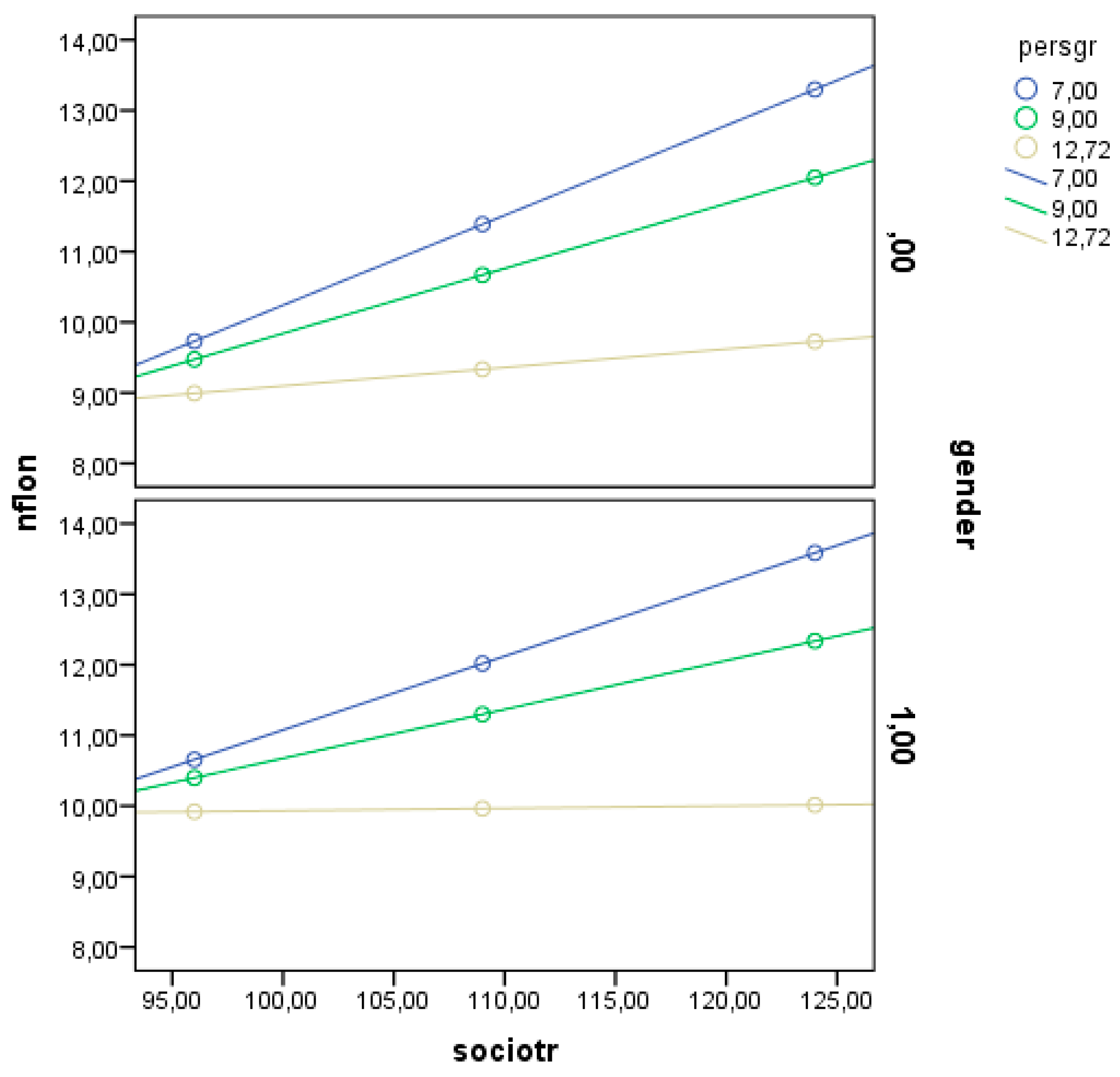

- Sociotropy predicted family loneliness and was moderated by gender.

- (6)

- Sociotropy predicted non-family loneliness and was moderated by gender.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beck, Aaron T. 1983. Cognitive therapy of depression: New perspectives. In Treatment of Depression: Old Controversies and New Approaches. Edited by Paula J. Clayton and James Elmer Barrett. New York: Raven Press, pp. 265–90. [Google Scholar]

- Böger, Anne, and Oliver Huxhold. 2018. Do the antecedents and consequences of loneliness change from middle adulthood into old age? Developmental Psychology 54: 181–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buecker, Susanne, Marlies Maes, Jaap J.A. Denissen, and Maike Luhmann. 2020. Loneliness and the Big Five Personality Traits: A Meta-analysis. European Journal of Personality 34: 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, John T., and Stephanie Cacioppo. 2018. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet 391: 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, John T., Mary Elizabeth Hughes, Linda J. Waite, Louise C. Hawkley, and Ronald A. Thisted. 2006. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging 21: 140–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craven, Gillian Mary. 2007. Sociotropy and Autonomy in Older Adults and the Relationships between the Personality Styles, Social Support, and Affect. A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology at Massey University. Ph.D. thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand; 232p. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, Franz, Edgar Erdfelder, Axel Buchner, and Albert-Georg Lang. 2009. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analysis. Behavior Research Methods 41: 1149–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. In Methodology in the Social Sciences, 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. 692p. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad, Julianne, Timothy B. Smith, Mark Baker, Tyler Harris, and David Stephenson. 2015. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Perspectives on Psychological Science 10: 227–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killgore, William D.S., Sara A. Cloonan, Emily C. Taylor, and Natalie S. Dailey. 2020. Loneliness: A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Research 290: 113–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Juensung J., Melanie Munroe, Zhe Feng, Stephanie Morris, Mohamed Al-Refae, Rebecca Antonacci, and Michel Ferrari. 2021. Personal Growth and Well-Being in the Time of COVID: An Exploratory Mixed-Methods Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 648060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, Reed W. 1990. The solitary side of life: An examination of the time people spend alone from childhood to old age. Developmental Review 10: 155–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennartsson, Carin, Johan Rehnberg, and Lena Dahlberg. 2022. The association between loneliness, social isolation and all-cause mortality in a nationally representative sample of older women and men. Aging & Mental Health 26: 1821–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Ye, Louise C. Hawkley, Linda J. Waite, and John T. Cacioppo. 2012. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study. Social Science & Medicine 74: 907–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfoli, Angelica, Federica Viglia, Micaela Di Consiglio, Sheila Merola, Stefano Sdoia, and Alessandro Couyoumdjian. 2021. Anaclitic-sociotropic and introjective-autonomic personality dimensions and depressive symptoms: A systematic review. Annals of General Psychiatry 20: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mund, Marcus, Maren M. Freuding, Kathrin Möbius, Nicole Horn, and Franz J. Neyer. 2020. The Stability and Change of Loneliness Across the Life Span: A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Personality and Social Psychology Review 24: 24–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Thuy-vy T, Netta Weinstein, and Richard M. Ryan. 2022. Who enjoys solitude? autonomous functioning (but not introversion) predicts self-determined motivation (but not preference) for solitude. PLoS ONE 17: e0267185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikitin, Jana, Fiona Sophia Rupprecht, and Christina Ristl. 2022. Experiences of solitude in adulthood and old age: The role of autonomy. International Journal of Behavioral Development 46: 510–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norbury, Ray. 2021. Loneliness in the time of COVID. The Journal of Biological and Medical Rhythm Research 38: 817–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ost Mor, Sharon, Yuval Palgi, and Dikla Segel-Karpas. 2020. The definition and categories of positive solitude: Older and younger adults’ perspectives on spending time by themselves. Interactional Journal of Aging and Human Development 93: 943–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prizeman, Katie, Netta Weinstein, and Ciara McCabe. 2023. Effects of mental health stigma on loneliness, social isolation, and relationships in young people with depression symptoms. BMC Psychiatry 23: 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, Clive J., Jon Ladd, Joan Welkowitz, Paul H. Blaney, Rolando Diaz, and Gary Kutcher. 1994. The personal style inventory: Preliminary validation studies of new measures of sociotropy and autonomy. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 16: 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizhitskaya, Olga, Inna Murtazina, and Marina Petrash. 2024. Loneliness and Sociotropy: The Moderation Effect of Age, Gender and Psychological Well-Being. Konsul’tativnaya psikhologiya i psikhoterapiya = Counseling Psychology and Psychotherapy 32: 103–21, (In Russia, abstract in English). [Google Scholar]

- Strizhitskaya, Olga, Marina Petrash, Inna Murtazina, and Gayane Vartanyan. 2021a. Adaptation of “Sociotropy—Self-Sufficience” Questionnaire for Russian Sample on Middle Adults and Ageing People. Eksperimental’naâ psihologiâ = Experimental Psychology (Russia) 14: 217–33, (In Russia, abstract in English). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizhitskaya, Olga, Marina Petrash, Inna Murtazina, Gayane Vartanyan, and Anton Shchukin. 2021b. Loneliness among Middle-Aged and Older Middle-Aged Adults in Russia (Saint Petersburg) before and during COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 9889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizhitskaya, Olga, Marina Petrash, Inna Murtazina, Gayane Vartanyan, Fedor Manevsky, Natalia Alexandrova, and Lilia Babakova. 2020. Adaptation of the Bulgarian Version of the Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale (Short Form) for Adults and Older Adults. Konsul’tativnaya Psikhologiya i Psikhoterapiya = Counseling psychology Psychotherapy 28: 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- von Soest, Tilmann, Maike Luhmann, Thomas Hansen, and Denis Gerstorf. 2020. Development of loneliness in midlife and old age: Its nature and correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 118: 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, Nine E., Lynn Mobach, Viviana M. Wuthrich, Peter Vonk, Claudia M. Van der Heijde, Reinout W. Wiers, Ronald M. Rapee, and Anke M. Klein. 2023. Emotional and social loneliness and their unique links with social isolation, depression and anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders 329: 207–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Kaite, and Joan S. Girgus. 2019. Are Women More Likely than Men Are to Care Excessively about Maintaining Positive Social Relationships? A Meta-Analytic Review of the Gender Difference in Sociotropy. Sex Roles 81: 157–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukovskaya, Lidia V., and Evegenia G. Troshihina. 2011. SHkala psihologicheskogo blagopoluchiya K. Riff [Scale of Psychological well-being by C. Ryff]. Psihologicheskij zhurnal 32: 82–93. [Google Scholar]

| Sex | ||

| Females (%) | 54.1 | |

| Males (%) | 45.9 | |

| Age | ||

| Range | 35–55 | |

| M | 45.31 | |

| SD | 5.96 | |

| Education | ||

| 10 years or less (%) | 3.8 | |

| 10 to 15 years (%) | 15.3 | |

| 15 years and more (%) | 80.9 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single (%) | 10.2 | |

| Married (%) | 60.5 | |

| In a relationship (%) | 12.1 | |

| Divorced (%) | 16.6 | |

| Widow (%) | 0.6 | |

| Models | Coefficient | se | t | p | LLCI | UPCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | −0.023 | 0.011 | −2.100 | 0.037 | −0.045 | −0.001 |

| Model 2 | −0.025 | 0.010 | −2.593 | 0.010 | −0.044 | −0.006 |

| Model 3 | −0.017 | 0.010 | −1.746 | 0.083 | −0.036 | 0.002 |

| Model 4 | −0.002 | 0.009 | −2.337 | 0.021 | −0.037 | −0.003 |

| Model 5 | −0.0649 | 0.0528 | −1.2284 | 0.222 | −0.1693 | 0.0395 |

| Model 6 | −0.0729 | 0.0457 | −1.5944 | 0.113 | −0.1633 | 0.0174 |

| Interactions | R2 Change | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association between sociotropy and family loneliness: parallel moderation | |||

| Sociotropy (X) × Autonomy (W) | 0.016 | 2.942 | 0.089 |

| Sociotropy (X) × Personal Growth (Z) | 0.032 | 5.907 | 0.016 |

| Both | 0.052 | 4.774 | 0.010 |

| Association between sociotropy and non-family loneliness: moderated moderation | |||

| Sociotropy (X) × Personal Growth (W) × Autonomy (Z) | 0.050 | 9.246 | 0.003 |

| Interactions | R2 Change | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociotropy (X) × Personal Growth (W) | 0.017 | 2.905 | 0.090 |

| Sociotropy (X) × Sex (Z) | 0.010 | 0.178 | 0.673 |

| Both | 0.033 | 2.831 | 0.062 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Strizhitskaya, O.; Murtazina, I. Moderation Effects of Autonomy and Personal Growth on the Association of Sociotropy and Different Types of Loneliness. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13080388

Strizhitskaya O, Murtazina I. Moderation Effects of Autonomy and Personal Growth on the Association of Sociotropy and Different Types of Loneliness. Social Sciences. 2024; 13(8):388. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13080388

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrizhitskaya, Olga, and Inna Murtazina. 2024. "Moderation Effects of Autonomy and Personal Growth on the Association of Sociotropy and Different Types of Loneliness" Social Sciences 13, no. 8: 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13080388

APA StyleStrizhitskaya, O., & Murtazina, I. (2024). Moderation Effects of Autonomy and Personal Growth on the Association of Sociotropy and Different Types of Loneliness. Social Sciences, 13(8), 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13080388