Early Adolescents and Exposure to Risks Online: What Is the Role of Parental Mediation Styles? †

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Current Study

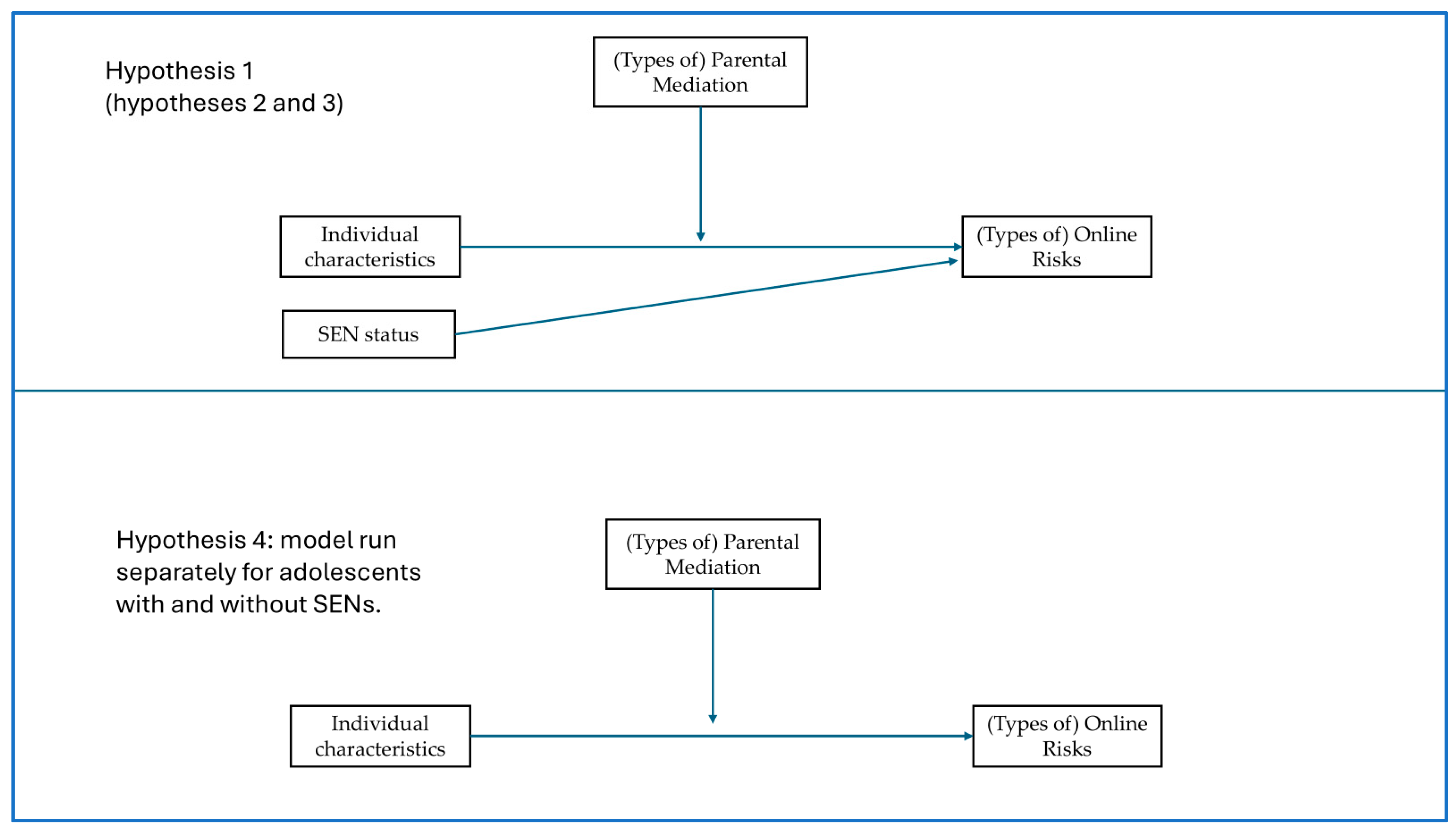

- 1.

- Levels of parental mediation strategies moderate the associations between early adolescents’ characteristics related to psychological and social adjustment (possible protective or risk factors) and their exposure to online risks. That is, we hypothesized that the associations between early adolescents’ characteristics related to psychological and social adjustment (possible protective or risk factors) and their exposure to online risks vary as a function of the levels of parental mediation strategies.

- 2.

- The moderation by parental mediation of the associations between individual characteristics and online risks varies depending on the type of mediation strategies, with high levels of active mediation being a stronger protective factor (Alheneidi et al. 2021; Fernandes et al. 2020);

- 3.

- The moderation by parental mediation of the associations between individual characteristics and online risks also varies depending on the type of online risks to which early adolescents are exposed;

- 4.

- The moderation by parental mediation of the associations between individual characteristics and online risks varies for early adolescents with SENs and without SENs.

2. Methods

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Parent Report Measures

- This study was part of a larger project on the online experiences of early adolescents and parental skills and behaviors towards their children’s Internet use. Therefore, parents responded to a battery of measures including a set of ad hoc items developed to assess their child’s typical Internet use (e.g., “To your knowledge, which social networks or platforms does your son/daughter use the most?”), questions on their own digital skills in comparison to their child’s (e.g., “Do you (parent) have at least one profile on a social network?”), questions from the checklist developed for the Net Children Go Mobile project (Mascheroni and Ólafsson 2014), and validated questionnaires. For the current study, we considered only the following variables: parental mediation strategies, their children’s exposure to online risks and their children’s psychological adjustment.

- Parental mediation strategies: Net Children Go Mobile checklist, Parent Form Q (Mascheroni and Ólafsson 2014).Parental mediation strategies were assessed using the checklist from the Net Children Go Mobile project (Mascheroni and Ólafsson 2014), Parent Form Q. The scale measures mediation, monitoring, and parental concerns on a three-point scale. Specifically, parents could answer choosing the options “never” (coded as 0), “sometimes” (coded as 1), and “often” (coded as 2) to answer questions such as, “How often do you do the following activities with your son/daughter: talk with him/her about what you can and cannot do on the internet, stay close to him/her when he/she uses the internet”. For the current study, we only considered the subscale for mediation consisting of 13 items assessing both restrictive and active forms of mediation (e.g., setting rules, discussing online content).

- Children’s exposure to online risks: Net Children Go Mobile checklist (Mascheroni and Ólafsson 2014).The experience of children in terms of exposure to the online risks were assessed by asking parents to answer six items from the Net Children Go Mobile project (Mascheroni and Ólafsson 2014). Parents answered how many times in the past year different situations had happened to their child, with three response options: “often,” “only 1 or 2 times,” or “never.” The items are reported in Table 2. For the analyses, the scores of the items were dichotomized (1 = “often” or “only 1 or 2 times”; 0 = “never”). This recoding was implemented for several reasons. First, the distribution of responses was highly skewed, with relatively few parents endorsing the “often” category, leading to sparse data in that cell and reducing statistical power. Combining “often” and “only 1 or 2 times” into a single category indicating any exposure allowed for a more robust estimation of associations. Second, from a conceptual standpoint, any experience of the risk, regardless of frequency, can be considered meaningful and relevant to children’s safety and well-being. Dichotomization therefore facilitated the interpretation of results as reflecting the presence versus absence of exposure.

- Adolescents’ psychological adjustment: Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire—SDQ (Goodman 1997).The SDQ (Goodman 1997) is a widely used behavioral screening tool that assesses psychological adjustment in children and adolescents. The parent report version includes 25 items covering five subscales: Emotional Symptoms, Conduct Problems, Hyperactivity/Inattention, Peer Problems, and Prosocial Behavior. Each item is rated on a three-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, 2 = certainly true). A Total Difficulties score is computed by summing the first four subscales. The SDQ has demonstrated good reliability and validity across diverse populations. In the current study, the internal consistency of Cronbach’s Alpha ranged from 0.69 to 0.79 for the subscales of the SDQ, except for the subscale of Peer Problems (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.53).

2.1.2. Adolescent Report Measures

- Indicators of school success: Analysis of Cognitive-Emotional Indicators of School Success (ACESS).The ACESS (Vermigli 2002) is a self-report tool designed to assess key emotional and cognitive factors related to school adjustment. It includes subscales on Emotionality (e.g., anxiety, sadness), Body Identity (self-perception and body satisfaction), School Adjustment (academic engagement and satisfaction), Social Adjustment (experiencing good peer relationships and social integration), and Family Relationships (experiencing the family as a point of reference from which they can obtain the necessary support to face new experiences). Items are rated using a four-point Likert scale: from “absolutely false” (1) to “absolutely true” (4). This instrument is particularly suitable for use with early adolescents and has been employed in educational and psychological assessments in Italy. The subscale scores have been calculated as the average of the item scores. Cronbach’s Alpha showed good levels of reliability of the five subscales. α = 0.89 for School Adjustment, α = 0.88 Emotionality, α = 0.69 for Body Identity, α = 0.76 for Social Adjustment, and α = 0.86 for Family Relationships.

2.2. Participants

2.3. Strategy of Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Factor Analyses

3.1.1. Factor Analysis of the Parental Mediation Strategies

3.1.2. Factor Analysis of the Online Risk Checklist

3.2. Moderation Regression Analyses

3.2.1. Moderation Models Run on All the Adolescents (Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3)

3.2.2. Adolescents with and Without SENs: Separate Moderation Regression Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alheneidi, Hasah, Loulwah AlSumait, Dalal AlSumait, and Andrew P. Smith. 2021. Loneliness and problematic internet use during COVID-19 lock-down. Behavioral Sciences 11: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yagon, Michal, and Malka Margalit. 2013. Social cognition of children and adolescents with learning disabilities. In Handbook of Learning Disabilities. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 278–303. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, André Luiz Monezi, Sônia Regina Fiorim Enumo, Maria Aparecida Zanetti Passos, Eliana Pereira Vellozo, Teresa Helena Schoen, Marco Antônio Kulik, Sheila Rejane Niskier, and Maria Sylvia de Souza Vitalle. 2021. Problematic internet use, emotional problems and quality of life among adolescents. Psico-USF 26: 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldry, Anna Costanza, Anna Sorrentino, and David P. Farrington. 2019. Post-traumatic stress symptoms among Italian preadolescents involved in school and cyber bullying and victimization. Journal of Child and Family Studies 28: 2358–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, Christopher P., and Miranda Fennel. 2018. Examining the relation between parental ignorance and youths’ cyberbullying perpetration. Psychology of Popular Media Culture 7: 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, Syeda Shahida, and Saba Ghayas. 2020. Process of career identity formation among adolescents: Components and factors. Heliyon 6: e04905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleakley, Amy, Morgan Ellithorpe, and Daniel Romer. 2016. The role of parents in problematic internet useamong US adolescents. Media and Communication 4: 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, Kenneth A. 1989. Structural Equations with Latent Variables. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Sahara, Sherri Jean Katz, Theodore Lee, Daniel Linz, and Mary McIlrath. 2014. Peers, predators, and porn: Predicting parental underestimation of children’s risky online experiences. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19: 215–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, Fatma Hulya, and Hesna Gul. 2018. Factors associated with problematic internet use among children and adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Northern Clinics of Istanbul 5: 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., and Yang-Chih Fu. 2009. Internet use and academic achievement: Gender differences in early adolescence. Adolescence 44: 797–812. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choi, Bo Young, Sun Huh, Dai-Jin Kim, Sang Won Suh, Sang-Kyu Lee, and Marc N. Potenza. 2019. Transitions in problematic internet use: A one-year longitudinal study of boys. Psychiatry Investigation 16: 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, Kevin M., Sarah M. Coyne, Eric E. Rasmussen, Alan J. Hawkins, Laura M. Padilla-Walker, Sage E. Er-ickson, and Madison K. Memmott-Elison. 2016. Does parental mediation of media influence child outcomes? A meta-analysis on media time, aggression, substance use, and sexual behavior. Developmental Psychology 52: 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadi, Abel Fekadu, Berihun A. Dachew, and Gizachew A. Tessema. 2024. Problematic internet use: A growing concern for adolescent health and well-being in a digital era. Journal of Global Health 14: 03034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, Julia, and Elena Martellozzo. 2013. Exploring young people’s use of social networking sites and digital media in the internet safety context: A comparison of the UK and Bahrain. Information, Communication and Society 16: 1456–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Río, M. A. Casado, M. Garmendia Larrañaga, and C. Garitaonandia Garnacho. 2019. Internet and Spanish children with learning and behavioural problems and other disabilities. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 74: 653–67. [Google Scholar]

- Eden, Sigal, and Hila Tal. 2024. Why Do Parenting Styles Matter? The Relation Between Parenting Styles, Cyberbullying, and Problematic Internet Use Among Children With and Without SLD/ADHD. Journal of Learning Disabilities 58: 359–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Asam, Aiman, Lara Jane Colley-Chahal, and Adrienne Katz. 2023. Social isolation and online relationship-risk encounters among adolescents with special educational needs. Youth 3: 671–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Asam, Aiman, Rebecca Lane, and Adrienne Katz. 2022. Psychological distress and its mediating effect on experiences of online risk: The case for vulnerable young people. Frontiers in Education 7: 772051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaesser, Caitlin, Beth Russell, Christine McCauley Ohannessian, and Desmond Patton. 2017. Parenting in a digital age: A review of parents’ role in preventing adolescent cyberbullying. Aggression and Violent Behavior 35: 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, Blossom, Urmi Nanda Biswas, Roseann Tan Mansukhani, Alma Vallejo Casarín, and Cecilia A. Essau. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on internet use and escapism in adolescents. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes 7: 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floros, Georgios, Anna Paradeisioti, Michalis Hadjimarcou, Demetrios G. Mappouras, Olga Kalakouta, Penelope Avagianou, and Konstantinos Siomos. 2013. Cyberbullying in Cyprus–associated parenting style and psychopathology. Annual Review of Cybertherapy and Telemedicine 2013: 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisén, Ann, and Sofia Berne. 2020. Swedish adolescents’ experiences of cybervictimization and body—Related concerns. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 61: 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioia, Francesca, Valeria Rega, and Valentina Boursier. 2021. Problematic internet use and emotional dysregulation among young people: A literature review. Clinical Neuropsychiatry 18: 41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goodman, Robert. 1997. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 38: 581–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, Patricia, Sion Kim Harris, Carmen Barreiro, Manuel Isorna, and Antonio Rial. 2017. Profiles of Internet use and parental involvement, and rates of online risks and problematic Internet use among Spanish adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior 75: 826–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2022. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Emily, Mark Boyes, Barbara Blundell, Juliana Hirn, and Suze Leitão. 2025. Managing cyberbullying among adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders: A scoping review. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 27: 341–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalmus, Veronika, Lukas Blinka, and Kjartan Ólafsson. 2015. Does it matter what mama says: Evaluating the role of parental mediation in European adolescents’ excessive Internet use. Children & Society 29: 122–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmus, Veronika, Marit Sukk, and Kadri Soo. 2022. Towards more active parenting: Trends in parental mediation of children’s internet use in European countries. Children and Society 36: 1026–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavale, Kenneth A., and Steven R. Forness. 1996. Social skill deficits and learning disabilities: A meta-analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities 29: 226–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landoll, Ryan R., Annette M. La Greca, Betty S. Lai, Sherilynn F. Chan, and Whitney M. Herge. 2015. Cyber victimization by peers: Prospective associations with adolescent social anxiety and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence 42: 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Jingjing, Li Wu, Xiaojun Sun, Xuqing Bai, and Changying Duan. 2023. Active parental mediation and adolescent problematic internet use: The mediating role of parent–child relationships and hiding online behavior. Behavioral Sciences 13: 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Sihan, Boya Xu, Di Zhang, Yuxin Tian, and Xinchun Wu. 2022a. Core symptoms and symptom relationships of problematic internet use across early, middle, and late adolescence: A network analysis. Computers in Human Behavior 128: 107090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Sihan, Shengqi Zou, Di Zhang, Xinyi Wang, and Xinchun Wu. 2022b. Problematic Internet use and academic engagement during the COVID-19 lockdown: The indirect effects of depression, anxiety, and insomnia in early, middle, and late adolescence. Journal of Affective Disorders 309: 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingstone, Sonia, Leslie Haddon, Anke Görzig, and Kjartan Ólafsson. 2011. Risks and Safety on the Internet: The Perspective of European Children: Full Findings and Policy Implications from the EU Kids Online Survey of 9–16 Year Olds and Their Parents in 25 Countries. Available online: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/33731/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Lukavská, Kateřina, Ondřej Hrabec, Jiří Lukavský, Zsolt Demetrovics, and Orsolya Kiraly. 2022. The associations of adolescent problematic internet use with parenting: A meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors 135: 107423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheux, Anne J., Kaitlyn Burnell, Maria T. Maza, Kara A. Fox, Eva H. Telzer, and Mitchell J. Prinstein. 2025. Annual Research Review: Adolescent social media use is not a monolith: Toward the study of specific social media components and individual differences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 66: 440–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascheroni, Giovanna, and Kjartan Ólafsson. 2014. Net Children Go Mobile: Risks and Opportunities. Available online: https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/55798/1/Net_Children_Go_Mobile_Risks_and_Opportunities_Full_Findings_Report.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Munno, Donato, Flora Cappellin, Marta Saroldi, Elisa Bechon, Fanny Guglielmucci, Roberto Passera, and Giuseppina Zullo. 2017. Internet Addiction Disorder: Personality characteristics and risk of pathological overuse in adolescents. Psychiatry Research 248: 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, Bengt, and Linda Muthén. 1998–2017. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Walker, Laura M., Sarah M. Coyne, Ashley M. Fraser, W. Justin Dyer, and Jeremy B. Yorgason. 2012. Parents and adolescents growing up in the digital age: Latent growth curve analysis of proactive media monitoring. Journal of Adolescence 35: 1153–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, H. M., and M. Macur. 2021. Problematic internet use profiles and psychosocial risk among adolescents. PLoS ONE 16: e0257329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Wei, and Xiaowen Zhu. 2022. Parental mediation and adolescents’ internet use: The moderating role of parenting style. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 51: 1483–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruckwongpatr, Kamolthip, Paratthakonkun Chirawat, Simin Ghavifekr, Wan Ying Gan, Serene E. H. Tung, Ira Nurmala, Siti R. Nadhiroh, Iqbal Pramukti, and Chung-Ying Lin. 2022. Problematic internet use (PIU) in youth: A brief literature review of selected topics. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 46: 101150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, Patricia Gomez, Patricia, Antonio Rial Boubeta, Teresa Brana Tobio, and Jesus Varela Mallou. 2014. Evaluation and early detection of problematic Internet use in adolescents. Psicothema 1: 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towner, Emily, Jennifer Grint, Tally Levy, Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, and Livia Tomova. 2022. Revealing the self in a digital world: A systematic review of adolescent online and offline self-disclosure. Current Opinion in Psychology 45: 101309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Huong Giang Nguyen, Truc Thanh Thai, Ngan Thien Thi Dang, Duy Kim Vo, and Mai Huynh Thi Duong. 2023. Cyber-victimization and its effect on depression in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 24: 1124–39. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2020. Global Education Coalition. London: UNESCO. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/globalcoalition (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- van Dijk, Rianne, Inge E. van der Valk, Helen G. M. Vossen, Susan Branje, and Maja Deković. 2021. Problematic internet use in adolescents from divorced families: The role of family factors and adolescents’ self-esteem. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermigli, Patrizia. 2002. ACESS-Analisi Degli Indicatori Cognitivo-Emozionali del Successo Scolastico. Trento: Edizioni Erickson. [Google Scholar]

- West, Monique, Simon Rice, and Dianne Vella-Brodrick. 2025. Mid-adolescents’ social media use: Supporting and suppressing autonomy. Journal of Adolescent Research 40: 448–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Alexander M., Catherine Deri Armstrong, Adele Furrie, and Elizabeth Walcot. 2009. The mental health of Canadians with self-reported learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities 42: 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. 2014. Health for the World’s Adolescents: A Second Chance in the Second Decade; Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Ybarra, Michele L., Kimberly J. Mitchell, David Finkelhor, and Janis Wolak. 2006. Examining characteristics and associated distress related to Internet harassment: Findings from the Second Youth Internet Safety Survey. Pediatrics 118: e1169–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Chengyan, Shiqing Huang, Richard Evans, and Wei Zhang. 2021. Cyberbullying among adolescents and children: A comprehensive review of the global situation, risk factors, and preventive measures. Frontiers in Public Health 9: 634909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Not SEN | SEN | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | F | M |

| 34 | 39 | 18 | 28 |

| M Age (SD) | M Age (SD) | ||

| 12.82 (1.3) | 12.56 (1.5) | 13.17 (1.3) | 12.54 (1.4) |

| Variables | Measure (Source) | Role in the Moderation Regression Models |

|---|---|---|

Individual Characteristics

| ACESS (adolescents) | Predictor variables: each variable in separate models |

| SDQ (parents) | Predictor variables: each variable in separate models |

Parental Mediation Strategies—Dimensions (Hypothesis 2)

| Net Children Go Mobile checklist, Parent Form Q (parents) | Moderation variables (hypothesis 1): each variable in separate models |

Online risks

| Net Children Go Mobile checklist—six items (parents) | Criterion variables: each variable in separate models |

| Control | Active Mediation and CO-Use | |

|---|---|---|

| I check the material downloaded from the Internet | 0.851 | 0.315 |

| I check his chats | 0.850 | 0.098 |

| I check his social profiles | 0.828 | 0.119 |

| I check the friends he interacts with online | 0.803 | 0.170 |

| Control the apps he downloads on his phone | 0.698 | 0.049 |

| Limit his time on the Internet | 0.687 | −0.031 |

| Controlling his search history | 0.683 | 0.562 |

| I use a parental control filter | 0.510 | 0.151 |

| I talk to him about what he can and cannot do online | 0.262 | 0.705 |

| I talk to him about modified photos of models | −0.112 | 0.607 |

| I stay close to him when he is on the Internet | 0.360 | 0.602 |

| I encourage him to learn new things on the Internet | −0.059 | 0.555 |

| Share time in online activities with him/her | 0.314 | 0.529 |

| Contact Risks | Conduct Risks | |

|---|---|---|

| He/she has been excluded from chats | 0.791 | 0.091 |

| Has been offended in a chat room or social network | 0.789 | −0.003 |

| Someone he/she met online asked to meet him/her | 0.587 | 0.184 |

| Pretended to be someone else | 0.205 | 0.732 |

| Made fun of someone in a chat room or social network | 0.389 | 0.709 |

| Spread offensive images in a chat room or social network | 0.19 | 0.537 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper | Z | p | |

| Social Adjustment | −0.113 | 0.0996 | −0.308 | 0.0821 | −1.14 | 0.256 |

| Active Mediation | 0.364 | 0.2851 | −0.194 | 0.9231 | 1.28 | 0.201 |

| Social Adj. ∗ Active Med. | −0.134 | 0.0946 | −0.320 | 0.0509 | −1.42 | 0.155 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper | Z | p | |

| Social Adjustment | −0.0763 | 0.0685 | −0.211 | 0.0579 | −1.11 | 0.265 |

| Active Mediation | 1.1398 | 0.3209 | 0.511 | 1.7687 | 3.55 | <0.001 |

| Social Adj. ∗ Active Med. | −0.1623 | 0.0914 | −0.341 | 0.0168 | −1.78 | 0.076 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cavallini, C.; Caravita, S.C.S.; Colombo, B. Early Adolescents and Exposure to Risks Online: What Is the Role of Parental Mediation Styles? Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110627

Cavallini C, Caravita SCS, Colombo B. Early Adolescents and Exposure to Risks Online: What Is the Role of Parental Mediation Styles? Social Sciences. 2025; 14(11):627. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110627

Chicago/Turabian StyleCavallini, Clara, Simona Carla Silvia Caravita, and Barbara Colombo. 2025. "Early Adolescents and Exposure to Risks Online: What Is the Role of Parental Mediation Styles?" Social Sciences 14, no. 11: 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110627

APA StyleCavallini, C., Caravita, S. C. S., & Colombo, B. (2025). Early Adolescents and Exposure to Risks Online: What Is the Role of Parental Mediation Styles? Social Sciences, 14(11), 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110627