Grounded Theory as an Approach for Exploring the Effect of Cultural Memory on Psychosocial Well-Being in Historic Urban Landscapes

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Problem Statement

1.3. Defining Grounded Theory

- Data are simultaneously gathered and analysed;

- Analytic categories (codes) are constructed from the data, rather from a hypothesis deduced prior to data-gathering;

- Comparison of data is undertaken at every stage;

- Theory development remains constant throughout each stage of data gathering and analysis;

- Researchers keep notes and memos of the categories under creation, along with their specific properties and relationships to each other and any gaps which emerge; and

- Sampling is chosen to aid the construction of theory, rather than to represent a given population.

- The complex social experiences of users and visitors to HULs are examples of the phenomena that GT was specifically devised to investigate and explain;

- Researchers using constructivist GT are required to perform a literature review before the empirical stage to better familiarise themselves with the researched phenomena and identify the research initial concepts;

- Researchers using constructivist GT are required to immerse themselves in the research setting and the data gathered from it in order to gain rich and nuanced insight into a multilayered and multisubject phenomenon;

- It is based on the real, firsthand experience of the phenomenon under investigation (Charmaz 2000;)

- It gives researchers a comprehensive understanding of how users believe they inhabit and experience their worlds (Charmaz 2000); and

- It enables the collection of rich data that reflect multiple perspectives and prioritize memory, meaning, and interpretation.

2. Research Design

- To examine the current conservation and HUL concepts and themes;

- To analyse the relationship between cultural memory, HUL, and psychosocial well-being;

- To study the extent of present HUL management practices needed to maintain cultural memory and achieve well-being; and

- To investigate the proposed changes needed for new HUL management plans that would help in maintaining psychosocial well-being.

3. Research Process

3.1. Literature Review Critical Analysis (First Phase)

3.2. Empirical Study (Second Phase)

3.2.1. Setting

3.2.2. Methods of Data Collection

3.2.3. Data Management and Analysis

3.2.4. Findings

3.3. Formulating Conclusions/Construction of Theory (Third Phase)

4. Conclusions

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Grounded Theory for HUL Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Approval

Appendix A

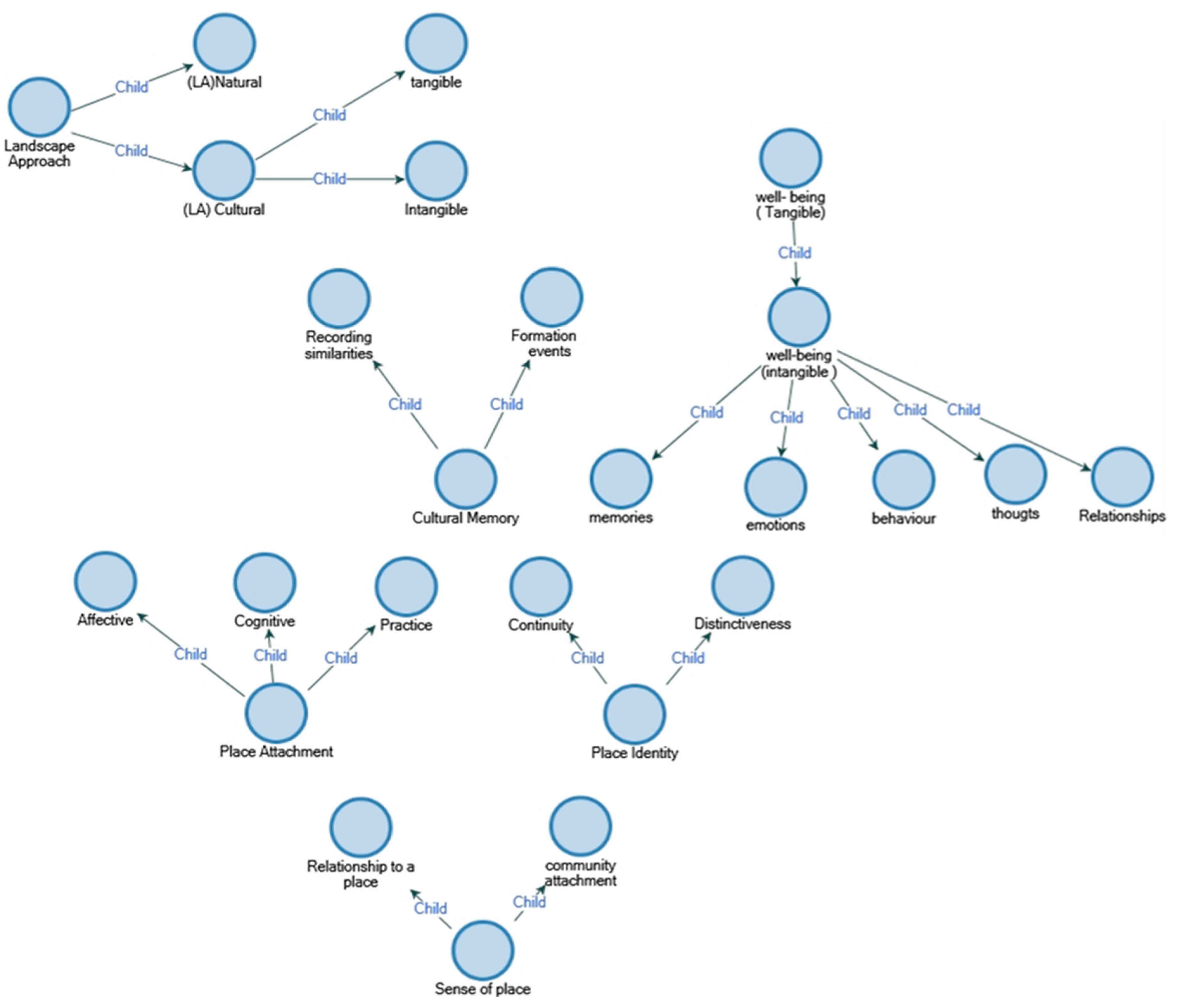

| Research Concepts (Themes) | Description | Components (Sub-Themes) | Sub-Components | First Proposed Measuring and Action Questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-being: ”A global assessment of a person’s quality of life according to his own chosen criteria” (Shin and Johnson 1978). | Well-being is a holistic health condition containing all the physical, cognitive, emotional, social, physical, and spiritual dimensions (INEE 2017). | Tangible quality of life |

|

|

| Intangible quality of life |

Psychological state Personal beliefs Social relationships | |||

| Psychosocial well-being: “Psychosocial well-being is a condition that includes a full range of what is good for a person” (INEE 2017). | It is the close relationship between psychological aspects and people’s broader social experience (INEE 2017). |

|

| |

| Sense of place “The particular experience of a person in a particular setting (feeling stimulated, excited, joyous, expansive, and so forth).” (Cross 2001). | It is composed of two different aspects. First is the relationship to place, dealing with the ways that people relate to places, and the types of bonds we have with places. Second is community attachment, dealing with the depth and types of attachments to a person’s particular place (Cross 2001). | Relationships to place |

|

|

| Community attachment |

|

| ||

| Cultural Memory (collective memory): “A series of events collectively remembered by a group of people who share it and involve themselves in shaping it” (Ardakani and Oloonabadi 2011). | It is a record of resemblances and similarities that is kept alive through continuous modifications and transmission (Hamilton 1994). | Formation of series of events | Social (Intangible)

|

|

Physical (Tangible)

|

| |||

| Recording similarities | Social (Intangible)

|

| ||

Physical (Tangible)

|

| |||

| Place attachment: “place attachment is a bond formed by people towards places” (Altman and Low 1992) | It an emotional bond formed between people and places that are significant to them, where they feel comfortable, secure, and related (Hernández et al. 2007). | Affective (Relation to moods) |

|

|

| Cognitive |

|

| ||

| Practice |

|

| ||

| Place identity: “Set of place features that guarantee the place’s distinctiveness and continuity in time” (Lewicka 2008). | It is found in the places that make us feel unique, in control, and happy about ourselves; is aligned with our personal ideas of who we are; and is more likely to be comprehended into our identity structure (Anton and Lawrence 2014). | Continuity: Maintaining identity in place over time (Twigger-Ross and Uzzell 1996) |

| |

| Distinctiveness: Unique and different place characteristics (Twigger-Ross and Uzzell 1996) |

| |||

| Landscape approach: “Landscape is a place to which a person becomes attached because of the nostalgia and the memories to which it gives rise” (Hoteit 2015). | Landscape is the result of the way various elements of both the natural (the effect of geology, soils, climate, flora, and fauna) and the cultural (the effect of historical and current human interventions) interact together and are appreciated by a person (Swanwick 2002). | Natural |

| |

| Cultural | Tangible

|

| ||

Intangible

|

|

References

- Achora, Susan, and Gerald Amandu Matua. 2016. Essential methodological considerations when using grounded theory. Nurse Researcher 23: 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandria, Portal. 2019. Available online: http://www.alexandria.gov.eg/Alex/english/index.aspx (accessed on 8 September 2019).

- Alexandria, Portal. 2020. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/alexandria1900/photos/a.364092033619757/2326206160741658/ (accessed on 8 October 2018). First publish 1900.

- Alexandria Egypt Land Meets Water. 2012. Sounds Like Wish. Available online: https://soundslikewish.com/tag/alexandria-egypt/ (accessed on 13 January 2020).

- Allen, Natalie, and Mark Davey. 2018. The Value of Constructivist Grounded Theory for Built Environment Researchers. Journal of Planning Education and Research 38: 222–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, Irwin, and Setha M. Low. 1992. Place Attachment. Edited by Irwin Altman and Setha M. Low. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alves de Sousa, Célio A. A., and Paul H. J. Hendriks. 2006. The Diving Bell And the Butterfly. The Need for Grounded Theory in Developing a Knowledge-based View of Organizations. Organizational Research Methods 9: 315–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, Charis E., and Carmen Lawrence. 2014. Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. Journal of Environmental Psycholgy 40: 451–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardakani, Maryam Keramati, and Seyyed Saeed Ahmadi Oloonabadi. 2011. Collective memory as an efficient agent in sustainable urban conservation. Procedia Engineering 21: 985–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Asem, Dalia. 2009. El Zanqa Market a Folkloric Painting Drawn by the Alexandrian Traditional Girls (Arabic Source). Available online: http://archive.aawsat.com/details.asp?section=67&article=512941&issueno=11080#.WG0ZL027rug (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Awad, Mohamed. 1996. The Metamorphosis of Mansheyah. In Alexandrie en Égypte(Alexandria in Egypt). Edited by Kenneth Brown, Hannah Davis Taieb, Edwar al-Kharrat and Adel Abou Zahra. (Special issue 8/9). Cairo: Méditerranéennes(French Periodical). Available online: https://thewallsofalex.blogspot.com/2014/07/the-metamorphosis-of-mansheya.html (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Aysegul, Kaya Tanriverdi. 2016. Method for Assessment of the Historical Urban Landscape. Procedia Engineering 161: 1697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Sarah, and Rosalind Edwards. 2012. How Many Qualitative Interviews is Enough. National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper. Available online: http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/4/how_many_interviews.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Bandarin, Francesco, and Ron van Oers. 2015. Reconnecting the City: The Historic urban Landscape Approach and the Future of urban Heritage. Edited by Francesco Bandarin and Ron van Oers. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, M. Christine. 1994. The City of Collective Memory: Its Historical Imagery and Architectural Entertainments/M. Christine Boyer. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brian, W. Eisenhauer, Richard S. Krannich, and Dale J. Blahna. 2000. Attachments to Special Places on Public Lands: An Analysis of Activities, Reason for Attachments, and Community Connections. Society & Natural Resources 13: 421–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carone, Paola, Pasquale De Toro, and Alfredo Franciosa. 2017. Evaluation of Urban Processes on Health in Historic Urban Landscape Approach: Experimentation in the Metropolitan Area of Naples (Italy). Kvalita Inovácia Prosperita 21: 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2000. Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In The Handbook of Qualitative Research. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna Sessions Lincoln. London: Sage Publications, pp. 509–35. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2005. Grounded Theory in the 21st Century: Applications for Advancing Social Justice Studies. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna Sessions Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd., pp. 507–35. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis/Kathy Charmaz. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2015. Grounded Theory: Methodology and Theory Construction. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. New York: Elsevier, pp. 402–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory/Kathy Charmaz, 2nd ed. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshmehzangi, Ali, and Tim Heat. 2012. Urban Identities: Influences on Socio-Environmental Values and Spatial Inter-Relations. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 36: 253–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, Mike, and Sean Barrett. 2016. A Brush with Research: Teaching Grounded Theory in the Art and Design Classroom. Universal Journal of Educational Research 4: 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, Jennifer E. 2001. What is Sense of Place? Paper presented at 12th Headwaters Conference, Western State College, CO, USA, November 2–4; Available online: http://western.edu/sites/default/files/documents/cross_headwatersXII.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2019).

- Daengbuppha, Jaruwan, Nigel Hemmington, and Keith Wilkes. 2006. Using grounded theory to model visitor experiences at heritage sites: Methodological and practical issues. Qualitative Market Research 9: 367–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyaa, Nada. 2016. Another legacy wasted: Alexandria’s Al-Salam theatre is demolished. Daily News/Egypt. Available online: https://wwww.dailynewssegypt.com/2016/06/26/another-legacy-wasted-alexandrias-al-salam-theatre-demolished/ (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Eyles, John. 1985. Senses of Place. Warrington: Silverbrook Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eyles, John. 2008. Qualitative Approaches in the Investigation of Sense of place and Health Rellations. In Sense of Place, Health, and Quality of Life. Edited by John Eyles and Allison Williams. Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, Uwe. 2002. An Introduction to Qualitative Research/Uwe Flick, 2nd ed. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, John. 1998. Planning theory revisited. European Planning Studies 6: 245–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary, L.Evans. 2013. A Novice Researcher’s First Walk Through the Maze of Grounded Theory: Rationalization for Classical Grounded Theory. The Grounded Theory Review 12: 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, Maria Vittoria. 2003. Theory of attachment and place attachment. In Psychological Theories for Environmental Issues. Edited by Mirilia Bonnes and Terence Lee. London: Routledge, pp. 137–70. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Barney G. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory Strategies for Qualitative Research. Edited by Barney G. Glaser and Anselm L. Strauss. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- González-Teruel, Aurora, and M. Francisca Abad-García. 2012. Grounded theory for generating theory in the study of behavior. Library & Information Science Research 34: 31–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GoogleMaps. n.d. Alexandria, Egypt. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Alexandria,+Alexandria+Governorate,+Egypt/@31.2387263,29.7274058,10.25z/data=!4m5!3m4!1s0x14f5c49126710fd3:0xb4e0cda629ee6bb9!8m2!3d31.2000924!4d29.9187387 (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Goulding, Christina. 1998. Grounded theory: The missing methodology on the interpretivist agenda. Qualitative Market Research 1: 50–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, Jenny. 2015. Connecting with the past through social media: The ‘Beautiful buildings and cool places Perth has lost’ Facebook group. International Journal of Heritage Studies 21: 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbwachs, Maurice. 1992. On collective memory / Maurice Halbwachs. Edited, Translated, and with an Introduction by Lewis A. Coser. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, Paula. 1994. The Knife Edge: Debates about Memory and History. In Memory and History in Twentieth-Century Australia. Edited by Kate Darian-Smith and Pauline Hamilton. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hanafi, Mohamed Assem. 1993. Development and Conservation with Special Reference to the Turkish Town of Alexandria. Ph.D. thesis, University of York, York, UK. Available online: http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/10921 (accessed on 18 June 2020).

- Hay, Robert. 1998. Sense of Place in Developmental Context. Journal of Environmental Psychology 18: 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, Bernardo, Maria Carmen Hidalgo, Maria Salazar-Laplace, and Stephany Hess. 2007. Place attachment and place identity in natives and non-natives. Journal of Environmental Psychology 27: 310–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, Judith. 2010. The Coding Process and Its Challenges. The Grounded Theory Review 9: 265–289. [Google Scholar]

- Hoteit, Aida. 2015. Role of the Landscape in the Preservation of Collective Memory and the Enhancement of National Belonging. Canadian Social Science 11: 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummon, David M. 1992. Community attachment: Local sentiment and sense of place. In Place Attachment. Edited by Setha M. Low and Irwin Altman. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, Fatmaelzahraa, John Stephens, and Reena Tiwari. 2020a. Cultural Memories and Sense of Place in Historic Urban Landscapes: The Case of Masrah Al Salam, the Demolished Theatre Context in Alexandria, Egypt. Land (Basel) 9: 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, Fatmaelzahraa, John Stephens, and Reena Tiwari. 2020b. Cultural Memories for Better Place Experience: The Case of Orabi Square in Alexandria, Egypt. Urban Science 4: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, Fatmaelzahraa, John Stephens, and Reena Tiwari. 2020c. Memory for Social Sustainability: Recalling Cultural Memories in Zanqit Alsitat Historical Street Market, Alexandria, Egypt. Sustainability 12: 8141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEE. 2017. INEE Thematic Issue Brief: Psychosocial Well-Being. Available online: http://www.humanitarianinfo.org/iasc/content/products (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Ingold, Tim, and Jo Lee Vergunst. 2008. Ways of Walking: Ethnography and Practie on Foot. Edited by Tim Ingold and Jo Lee Vergunst. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, John Brinckerhoff. 1994. A Sense of Place, a Sense of Time/John Brinckerhoff Jackson. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jahanbakhsh, Heidar, Mostafa Hosseini Koumleh, and Fatemeh Sotoudeh Alambaz. 2015. Methods and Techniques in Using Collective Memory in Urban Design: Achieving Social Sustainability in Urban Environments. Cumhuriyet University Faculty of Science Journal (CSJ) 36: 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kawulich, Barbara.B. 2005. Participant Observation as a Data Collection Method. Available online: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/466/996 (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Kraus, Wolfgang. 2006. The narrative negotiation of identity and belonging. Narrative Inquiry 16: 103–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, Gerard T., Andrew J. Mowen, and Michael Tarrant. 2004. Linking place preferences with place meaning: An examination of the relationship between place motivation and place attachment. Journal of Environmental Psychology 24: 439–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, Maria. 2008. Place attachment, place identity, and place memory: Restoring the forgotten city past. Journal of Environmental Psychology 28: 209–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Na. 2010. Preserving Urban Landscapes as Public History: The Chinese Context. The Public Historian 32: 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Xingwei, Jianguo Du, and Hongyu Long. 2019. Green Development Behavior and Performance of Industrial Enterprises Based on Grounded Theory Study: Evidence from China. Sustainability 11: 4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Xiangrui. 2013. Scalable simple random sampling and stratified sampling. International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2013: 1568–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, Jane, Ann Bonner, and Karen Francis. 2016. The Development of Constructivist Grounded Theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5: 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molavi, Mehrnaz, Imira Rafizadeh Malekshah, and Elaheh Rafizadeh Malekshah. 2017. Is Collective Memory Impressed By Urban Elements? Management Research and Practice 9: 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, Janice Margaret. 1994. Designing funded qualitative research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna Sessions Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Ahmed. 2016. Six Touristic Buildings Were Demolished from Alexandria by the End of 2016 (Arabic Source). Available online: https://www.soutalomma.com/465080 (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Nora, Pierre. 1989. Between memory and history: Les lieux de memoire. Memory and Counter-Memory 26: 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nvivo10. 2020. About Nodes Nvivo10 for Windos Help. Available online: https://help-nv10.qsrinternational.com/desktop/concepts/about_nodes.htm (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Olsen, Wendy. 2004. Triangulation in Social Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods Can ReallyBe Mixed. In Developments In Sociology. Edited by Michael Haralambos and M. Holborn. Ormskirk: Causeway Press Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, J. Bateman, Crystal Pike Jacqueline, and S. Butler Brian. 2011. To disclose or not: Publicness in social networking sites. Information Technology & People 24: 78–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, Haywantee, Betty Weiler, and Liam David Graham Smith. 2012. Place attachment and pro-environmental behaviour in national parks: The development of a conceptual framework. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20: 257–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, Edward C. 1976. Place and Placelessness/E. Relph. Research in Planning and Design A Revision of the Author’s Thesis. London: University of Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- SDU (University of Southern Denmark). 2020. Better Thesis: Your online support. In A Joint Production by: University of Southern Denmark Library and the Unit for Health Promotion Research. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, Department of International Health and Faculty Library of Natural and Health Sciences. Available online: http://betterthesis.dk/research-methods/empirical-studies (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Shamai, Shmuel, and Zinaida Ilatov. 2005. Measuring Sense of Place: Methodological Aspects. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 96: 467–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D. C., and D. M. Johnson. 1978. Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Social Indicators Research 5: 475–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skene, Allyson. 2016. Writing a Critical Review. Available online: https://ctl.utsc.utoronto.ca/twc/sites/default/files/CritReview.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Steele, Fritz. 1981. The Sense of Place/Fritz Steele. Boston: CBI Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Anselm. 1990. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques/Anselm Strauss, Juliet Corbin. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Swanwick, Carys. 2002. Landscape Character Assessment: Guidance for England and Scotland. Sheffield: UK Countryside Agency Publications. Available online: https://www.nature.scot/sites/default/files/2018-02/Publication%202002%20-%20Landscape%20Character%20Assessment%20guidance%20for%20England%20and%20Scotland.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Tuan, Yi-Fu. 1980. The Significance of the Artifact. Geographical Review 70: 462–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigger-Ross, Clare L., and David L. Uzzell. 1996. Place and Identity Processes. Journal of Environmental Psychology 16: 205–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twitter.com. 2018. French Gardens 1930s [Photo/jpg]. Available online: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/De4aZMEXkAArk7H.jpg:large (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- Ujang, Norsidah, and Khalilah Zakariya. 2015. Place Attachment and the Value of Place in the Life of the Users. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 168: 373–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2016. The Hul Guidebook. Paper presented at the 15th World Conference of the League of Historical Cities, Bad Ischl, Austraia, June 5–10. Available online: http://historicurbanlandscape.com/themes/196/userfiles/download/2016/6/7/wirey5prpznidqx.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Van der Hoeven, Arno. 2019. Historic urban landscapes on social media: The contributions of online narrative practices to urban heritage conservation. City, Culture and Society 17: 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Allison, Christine Heidebrecht, Lily Demiglio, John Eyles, David Streiner, and Bruce Newblod. 2008. Developing a psychometric scale for measuring sense of place and health: An application of fact design. In Sense of Place, Health, and Quality of Life. Edited by John Eyles and Allison Williams. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Daniel R., Michael E. Patterson, Joseph W. Roggenbuck, and Alan E. Watson. 1992. Beyond the commodity metaphor: Examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Leisure Sciences 14: 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Daniel R., and Susan I. Stewart. 1998. Sense of place: An elusive concept that is finding a place in ecosystem management. Journal of Forestry 66: 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Kimberley, and Cheryl Desha. 2016. Engaging in design activism and communicating cultural significance through contemporary heritage storytelling: A case study in Brisbane, Australia. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 6: 271–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinobia. 2016. Farewell El-Salam Theatre of Alexandria “Updated”. Egyptian Chronicles. Available online: https://egyptianchronicles.blogspot.com/2016/06/june-13-2016-at-1225am.html (accessed on 7 June 2018).

| Differences | Classic GT (Glaser and Strauss) | Straussian GT (Strauss and Corbin) |

|---|---|---|

| Nature |

|

|

| Approach |

|

|

| Theoretical Sampling |

|

|

| Theoretical Sensitivity |

|

|

| The Use of Literature |

|

|

| Procedures and Techniques |

|

|

| Memo Writing |

|

|

| Coding |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hussein, F.; Stephens, J.; Tiwari, R. Grounded Theory as an Approach for Exploring the Effect of Cultural Memory on Psychosocial Well-Being in Historic Urban Landscapes. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9120219

Hussein F, Stephens J, Tiwari R. Grounded Theory as an Approach for Exploring the Effect of Cultural Memory on Psychosocial Well-Being in Historic Urban Landscapes. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(12):219. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9120219

Chicago/Turabian StyleHussein, Fatmaelzahraa, John Stephens, and Reena Tiwari. 2020. "Grounded Theory as an Approach for Exploring the Effect of Cultural Memory on Psychosocial Well-Being in Historic Urban Landscapes" Social Sciences 9, no. 12: 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9120219

APA StyleHussein, F., Stephens, J., & Tiwari, R. (2020). Grounded Theory as an Approach for Exploring the Effect of Cultural Memory on Psychosocial Well-Being in Historic Urban Landscapes. Social Sciences, 9(12), 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9120219