Abstract

The seaports of the Jin dynasty have not been given enough attention for a long time. In recent years, some important seaport sites of the Jin dynasty have been discovered or reported, for example the Haifengzhen (海丰镇) site in Hebei Province, and the Haibei (海北) and Banqiaozhen (板桥镇) sites in Shandong Province. Based on these discoveries and other related information, we can try to analyze and infer the function and system of these seaports in the Jin dynasty. Firstly, Banqiaozhen Shi Bo Si (市舶司), the Northern Song Dynasty’s only foreign trade administration in the north of China, suffered a great deal of damage during the war at the end of the Northern Song dynasty. As a consequence, the porcelains produced in Northern China during the Jin Dynasty, such as Cizhou Ware (磁州窑), Cicun Ware (磁村窑), and Ding Ware (定窑) needed new seaports for access to the Korean Peninsula and Japan. It has been reported that many of these porcelains were discovered at Korean and Japanese sites, which correspond to the years of the Jin dynasty. Furthermore, a large number of these porcelains were discovered at the Haifengzhen and Haibei sites. There is thus a very strong possibility that these two sites were departure ports to East Asia of the Maritime Silk Road during the Jin Dynasty. Secondly, many porcelains produced in Southern China, especially Jingdezhen Ware (景德镇窑), have been discovered at the Haifengzhen, Haibei, and Banqiaozhen sites. Some Ding Ware products were also discovered in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River during the Southern Song Dynasty, and also many Cizhou Ware and Ding Ware products were discovered in Northeastern China during the Jin Dynasty. Furthermore, in the coastal waters on the northern side of the Haifengzhen site, archaeologists have found some traces of shipwrecks dating from the same time. Based on the above information, we infer that the Haifengzhen, Haibei, and Banqiaozhen sites might also have played an important role in the seaway transshipment between Southern and Northern China during this period. In conclusion, we can determine that the recently discovered seaports of the Jin dynasty had two functions and systems, both internal and external:the Haifengzhen and Haibei sites opened China up to the Korean Peninsula and Japan, while the Haifengzhen, Haibei, and Banqiaozhen sites might also have been used for domestic coastal shipping.

1. Introduction

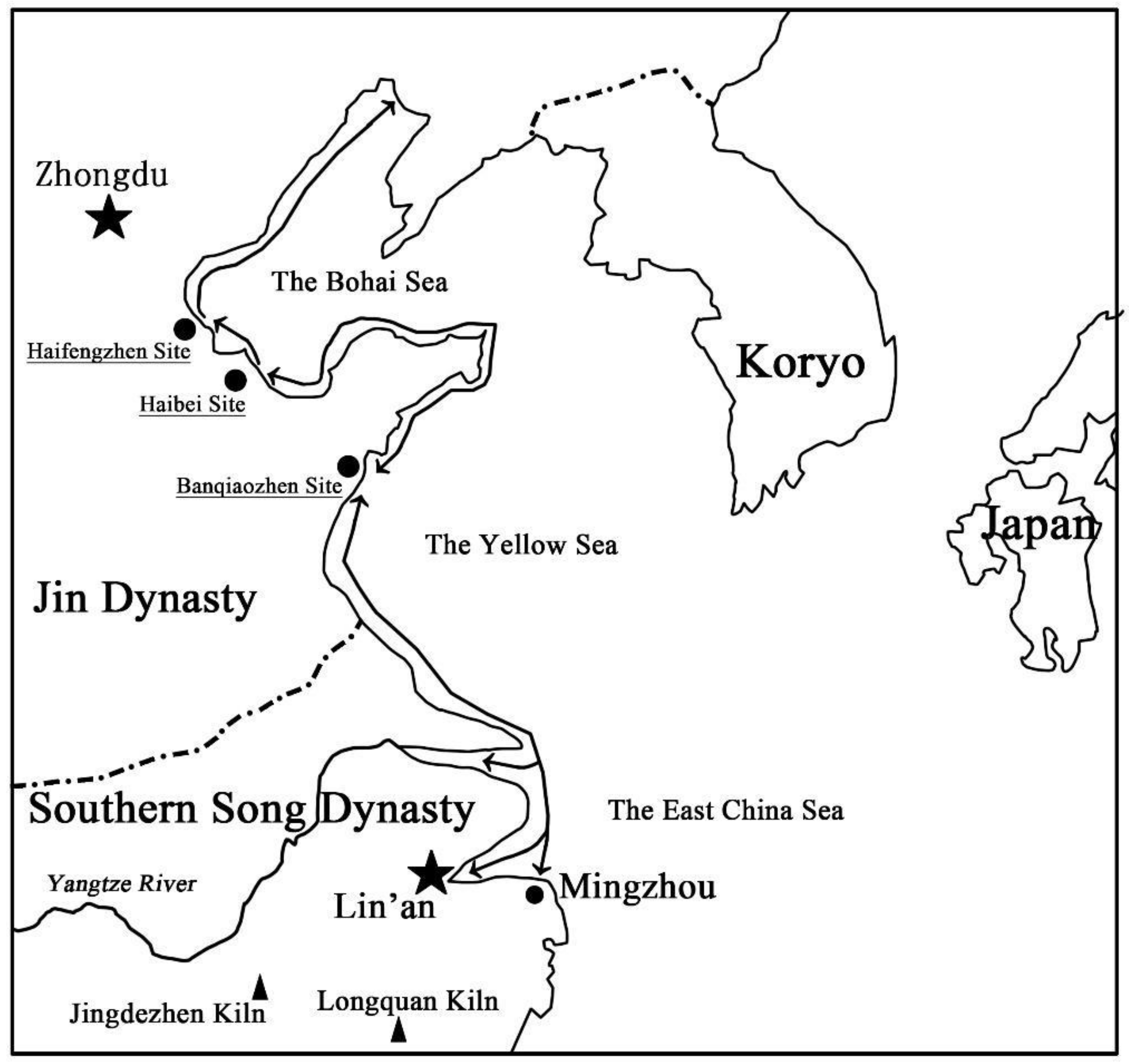

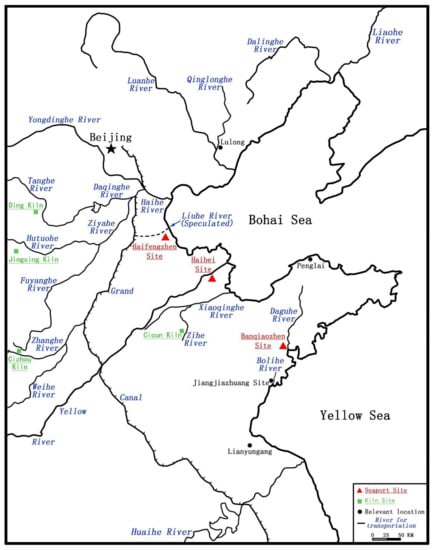

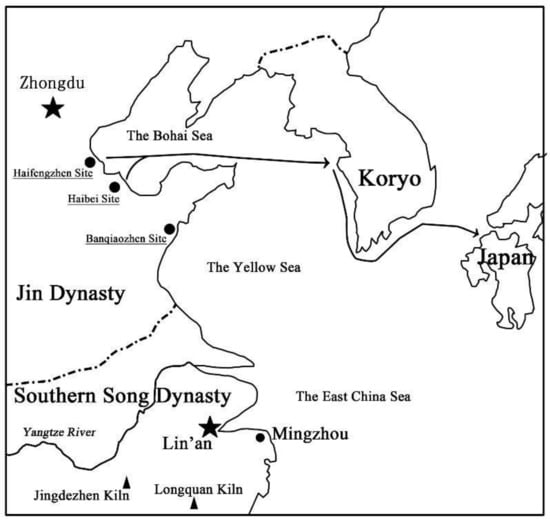

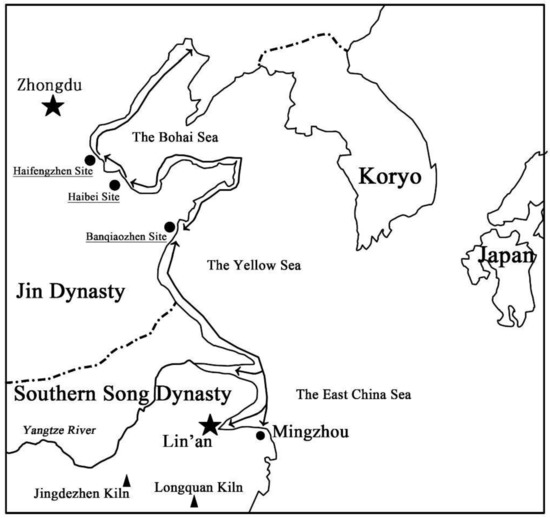

Since 2014, archaeological materials have been reported from coastal sites such as Banqiaozhen in Jiaozhou City, Shandong Province, Haifengzhen in Huanghua City, Hebei Province, and Haibei in Kenli County, Shandong Province (Figure 1). Notably, a large number of porcelain pieces from the Jin Dynasty (1115–1234 CE) were unearthed at these sites, gradually bringing issues about the position of harbors for porcelain transportation during the Jin Dynasty into sharper focus. Although the goods that were traded and shipped in and out of these ports were far more diverse than just porcelain, in terms of archaeological discoveries, porcelain can undoubtedly preserve the most abundant information. This article will take these three sites, combined with other related archaeological discoveries, as the starting point from which to carry out a preliminary study of the system of porcelain shipping in the coastal ports of the Jin Dynasty.

Figure 1.

The seaport sites and relevant sites of the Jin Dynasty.

2. Archaeological Discoveries in Jin Dynasty Harbors

2.1. The Haifengzhen Site in Huanghua

The Haifengzhen site is located at Haifengzhen Village, Yangerzhuang Town, Huanghua City, on the west shore of Bohai Bay in the eastern area of Hebei Province. It was excavated for the first time in 2000, and a large number of porcelains were unearthed, most of which are products of the Cizhou and Ding kilns (including the Jingxing kiln). According to our preliminary observation, of the more than 1700 specimens of porcelain, more than 1200 pieces should be from the above kilns, accounting for nearly 70% of the total amount, while the rest are products of the Yaozhou, Jun, Jingdezhen, and Longquan kilns, along with other domestic kilns. The vast majority of the specimens belong to the Jin Dynasty and the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279 CE), while a few belong to the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 CE) (Huanghua Museum et al. 2015; Research Center for Chinese Frontier Archaeology of Jilin University et al. 2016) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Porcelain unearthed at the Haifengzhen site, 2000. 1–8. Cizhou kiln; 9–12. Ding kiln; 13. Jingxing kiln; 14. Yaozhou kiln; 15. Jun kiln; 16. Jingdezhen kiln; 17. Longquan kiln.

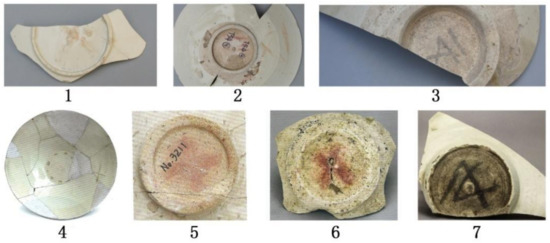

An interesting phenomenon is that some bowls discovered at the Haifengzhen site are clearly marked with deliberate “X” scratch marks, marks which were also found in Liaoning Province in Northeastern China, as well as at the Banqiaozhen site (Figure 3). Therefore, we have inferred that the Haifengzhen site must have been a seaport for porcelain trading during this period.

Figure 3.

The bowls marked with an “X”. 1–3. Haifengzhen site; 4,5. Chaoyang city in Liaoning Province; 6,7. Banqiaozhen site.

2.2. The Haibei Site in Kenli

The Haibei Site is located at Haibei Village, Shengtuo Town, Kenli County, on the southwest coast of Bohai Bay in the northeast of Shandong Province. In 2006, tens of thousands of porcelain fragments were discovered and collected here. The porcelain fragments are mainly the products of the Cicun kiln in Zibo City. In addition, there are also some products belonging to the Ding, Yaozhou, and Jingdezhen kilns among others, dating from the period ranging from the late Northern Song Dynasty to the Jin dynasty, with those from the Jin Dynasty being especially numerous (Xu and Chai 2016) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Porcelain specimens collected at the Haibei site, 2006. 1–6. Cicun kiln; 7,8. Jingdezhen kiln; 9. Yaozhou kiln; 10,11. Ding kiln.

The Haibei site is located near the Haifengzhen site, and the features of the two sites are so similar that the Haibei site is very likely to have been another seaport on the western shore of Bohai Bay.

2.3. The Banqiaozhen Site in Jiaozhou

Jiaozhou Bay, on the south side of Shandong Peninsula, has been a good and natural harbor since ancient times. The Banqiaozhen site is located on the north shore of Jiaozhou Bay, near the Daguhe River. The rise of Banqiaozhen followed the establishment of the Bureau for Foreign Shipping in the late Northern Song Dynasty. In 2008, a brick-paved building was found here, and it was speculated that it may be the ruins of the cargo terminal of the Song and Jin Dynasties.

In 2009, a large courtyard from the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127 CE) was excavated within the ruins of Banqiaozhen. Additionally unearthed were more than ten tons of iron coins from the Song Dynasty, and tens of thousands of pieces of porcelain. The excavators speculate that this construction may be tied to the Northern Song Dynasty’s Bureau for Foreign Shipping. In addition, there are still some residents who have undertaken activities after the abandonment of the Bureau building site, unearthing a large number of porcelain pieces from the Cicun kiln (Qingdao Institute of Cultural Relics Protection and Archaeological Research 2014) (Figure 5). Therefore, we have inferred that the Banqiaozhen site also played an important role in porcelain shipping during the Jin Dynasty, especially with regard to the Cicun Kiln.

Figure 5.

Products of the Cicun kiln, Jin Dynasty, unearthed at the Banqiaozhen site, 2009.

3. The Seaport System for Porcelain Shipping during the Jin Dynasty

3.1. The Position of These Seaports

At the end of the Northern Song Dynasty, war had a majorimpact on the Shandong area, and the area around the Bohai Sea. The Haifengzhen, Haibei, and Banqiaozhen sites, as the seaports of the Jin Dynasty, were experiencing a change in regime and social unrest, and new routes for porcelain shipping were being established.

3.1.1. The Emergence of a New Port—The Haifengzhen Site

The salt industry in the area around the Bohai Sea was prosperous during the Jin Dynasty, especially in Haifengzhen. According to research, the Liuhe River was near Haifengzhen Village, and flowed into the Bohai Sea during the Qin and Han dynasties, however it gradually silted up after the Yuan Dynasty. The salt of Haifengzhen could be shipped to the Central Plains via the Liuhe River, and the salt ships’ return provided a good opportunity for the porcelain produced in the kilns in the Hebei region, such as the Cizhou and Ding kilns, to be transported. As porcelain is fragile, transportation by water is best.

In 1998, a shipwreck fully loaded with porcelain from the Cizhou kiln was found at a wharf site of the South Canal in Dongguang County, Cangzhou City (Cangzhou Municipal Administration of Cultural Relics 2017). Zhigu (now Tianjin) had not established in Jin Dynasty, so the Haifengzhen site, which was an important port for the salt industry in Northern China, was likely to have been the ship’s destination. Based on the large number of porcelains from the Cizhou and Ding kilns discovered in Haifengzhen, it appears obvious that the Haifengzhen site must have been a new seaport for porcelain trading in Northern China, having the advantages of salt development and a convenient waterway.

3.1.2. The Expansion of the Old Port—The Haibei Site

The Haibei site arose in the late Northern Song dynasty, just as the foreign business of Dengzhou was declining, and military functions were gradually increasing. The rise of the Haibei site would have been a natural choice, caused by the functional conversion of the harbors along the northern side of the Shandong Peninsula.In addition, the Haibei site may have shared business functions with Dengzhou to a certain extent, thus becoming a new port on the northern side of the Shandong Peninsula.

However, the business activities along the northern side of the Shandong Peninsula were strictly controlled by the Northern Song Dynasty, as the Bureau for Foreign Shipping had been set up at Banqiaozhen, and the relations between the Northern Song Dynasty and the Liao Dynasty were strained. Either the function of the Haibei site as a harbor was not marked in historical records, or it was mainly a small harbor for smuggling activities at that time. The Northern Song Dynasty’s discovery of the Haibei site seems to confirm that it had not yet reached a prominent scale in this period.

During the Jin Dynasty, the Haibei site belonged to the Lijin County, which was also an important salt producing region. The Haibei site also had a convenient waterway to connect the lower reaches of the Yellow River, so that it held great potential for porcelain transportation. The porcelain found in the Haibei site mainly belongs to the Jin Dynasty, especially the Cicun kiln. The Cicun kiln was prosperous during the Jin Dynasty, and the northern side of Shandong Peninsula was no longer subject to the government’s restrictions. The Haibei site then, as a seaport for porcelain trading, had an excellent opportunity, and its size and capacity were obviously much greater than they had been during the Northern Song Dynasty.

3.1.3. The Conversion of the Business Port—The Banqiaozhen Site

Following the Northern Song Dynasty, Banqiaozhen, as the centre of government-designated administration for overseas trading, thus lost the political basis for its existence. Nevertheless, archaeological discoveries have indicated that Banqiaozhen was not completely abandoned after the Northern Song Dynasty. According to the literature, at that time, Banqiaozhen was one of the domestic markets near the border of the Jin Dynasty and the Southern Song Dynasty. The use of the Jin Dynasty pier discovered at the Banqiaozhen site was likely to have continued during the Northern Song Dynasty. Although the Baoqiaozhen site had a certain business function in the Jin dynasty, its function changed to a large extent from external to internal.

In 2014, at Jiangjiazhuang Village in the Huangdao District, south of Jiaozhou Bay, a site of the Song and Yuan Dynasties was discovered, speculated to be a pier site (Qingdao Institute of Cultural Relics Protection and Archaeological Research, Huangdao District Museum 2015). The Bolihe River flows south into the sea near the site, and northward extends to the south of the Jiaolai Plain. Although it may not have played an important role in long-distance transport, it could have been a regional water transportation line. The location of the Jiangjiazhuang site is still vague. If it proves to have been a small wharf site during the Jin Dynasty, there is every reason to believe that Banqiaozhen was supported by some nearby sub-level markets. In contrast, because Haizhou (now Lianyungang) was located at the border area of the Jin Dynasty and the Southern Song Dynasty, it completely lost the status of commercial port. The stone carving of warships dating from the Southern Song Dynasty found at Liuzhizhou Mountain in Lianyungang city is direct evidence of the decline of Haizhou’s commercial function (Luo and Gao 2008).

3.2. The Establishment of the Seaport System

While past research has paid significant attention to the foreign trading of the seaports, shipping between the ports is also a subject worthy of investigation. According to different materials and phenomena, we deem that the Haifengzhen, Haibei, and Banqiaozhen sites, as the representative seaports of the Jin Dynasty, formed two systems, as set out below:

(1) The departure port system offoreign trading

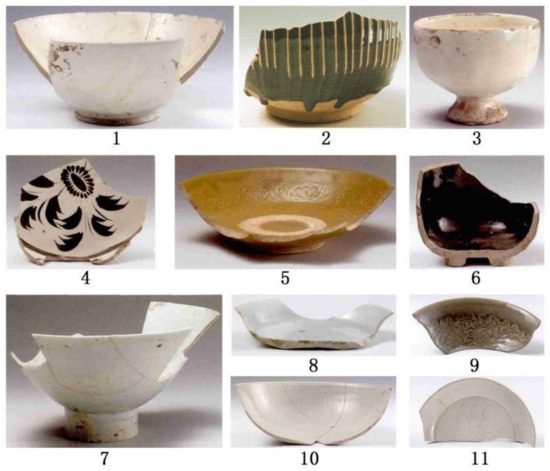

Foreign affairs between Chinese mainland dynasties and the Korean Peninsula or Japan were based on mutual gifts. The journey from the Korean Peninsula to the Jin Dynasty’s capital, Zhongdu or Shangjing, could be undertaken via the land road through the Liaodong area (Liu 2007), even with some fine porcelain, without the need of a waterway. However, underwater archaeological discoveries show that Chinese porcelain was very popular in foreign markets. Although the literature is scant in descriptions of overseas trading during the Jin Dynasty, relevant information shows that Chinese porcelains were often discovered1 in Japanese sites dating from the same time as the Jin Dynasty (Li 2015; Kyoto National Museum 1991), while the ruins of the Goryeo on the Korean Peninsula also reveal many products from the Cizhou and Ding kilns (Figure 6) (Jin 2010). Some bowls also have the similar “X” mark.

Figure 6.

Porcelain of the Jin dynasty unearthed in Japan and the Korean Peninsula. 1,2,5. Ding kiln; 3,4, 6–8. Cizhou kiln or Cicun kiln. (1. Unearthed in Shikoku; 2–8. Collected in the Korean National Museum).

During the Jin Dynasty, as Banqiaozhen had become mainly a domestic market between the North and the South, a new seaport was needed for the porcelain produced in the northern area and sold to the Korean Peninsula and Japan. The southern side of the Shandong Peninsula was near the conflict area, so the region around the Bohai Sea naturally became the first choice for overseas trading. As numerous products of the Cizhou and Ding kilns were unearthed in Haifengzhen, the same porcelain unearthed in Japan and the Korean Peninsula within the same period is likely to have been exported from the Haifengzhen site.

In addition, the products of the Cizhou and Cicun kilns had the same features during the Jin dynasty. It is possible that the products judged to be from the Cizhou kiln unearthed on the Korean Peninsula and in Japan were in fact produced by the Cicun kiln. If so, the Haibei and Banqiaozhen sites were probably the ports of departure from which the Cicun kiln’s products were transported to the Korean Peninsula and Japan. In contrast, Banqiaozhen was a domestic market, and near the border of the Jin Dynasty, and foreign business may have been affected by the political relations and military activities between the Jin Dynasty and the Southern Song Dynasty. Even if Banqiaozhen had had an external function, it would have been be difficult for it to recover the prosperity of the Northern Song Dynasty (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The sketch map of the route for foreign trading.

(2) The transshipment system of coastal transportation

Were the harbors discovered in the territory of the Jin Dynasty and overseas trading interrelated? If so, how did they connect with each other? We have conducted a preliminary analysis.

Firstly, we address the offshore routes along the west side of Bohai Bay:

The products of the Ding and Cizhou kilns in the Jin dynasty have often been found in Northeastern China (Peng 2010). Northern and Northeastern China are separated by mountains, and the terrain is not conducive to transporting large amounts of porcelain. In 2014, the Hebei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics found some shipwrecked porcelain of the Jin and Yuan Dynasties that has the same features as porcelain from the Haifengzhen site in the northern sea area (Dai and Chen 2014). Therefore, it is apparent that the ships departed from the Haifengzhen site or the Haibei site. Apart from sailing to the Korean Peninsula or Japan, ships could also sail along the west coast of Bohai Bay on a northbound route. The cargo ships could sail along the coastline, bypassing the Liaodong Peninsula, and finally arrive at the Korean Peninsula, or alternatively they could unload directly at the northern coast of Bohai Bay. Following this, the cargo could be transported farther north through the coastal cities to the area along the Dalinghe River, the Liaohe River, and other waters that flow into the Bohai Sea. The bowls marked with “X” discovered in Liaoning Province are good evidence of this.

Although city sites with seaport ruins of the Jin Dynasty have not been found on the north side of Bohai Bay, there have been some clues emerging from the northwest coast of Bohai Bay, specifically at Lulong County. The site is referred to as the water-transport site of Pingzhou, with the Luanhe River nearby. The river originates in northern Hebei, flows through the southeastern area of Inner Mongolia, south to Hebei Province, and finally into the Bohai Sea. According to historical records, this site may have been built during the Sui and Tang Dynasties, and repaired during the Yuan Dynasty. Therefore, it is likely to have been a transshipment terminal, connected to the Haifengzhen site or the Haibei site.

Secondly, we address the offshore routes bypassing the Shandong Peninsula:

During the Jin Dynasty, the Banqiaozhen site was a domestic market for the Southern Song Dynasty, where porcelain produced in both the north and the south have been discovered. There are also some porcelains produced in the southern area that have been unearthed at the Haifengzhen and Haibei sites. How did these porcelains come to be here?

On the one hand, aside from the Cicun kiln, the other kilns in the northern region were relatively distant from the Banqiaozhen site. Some of the products of the Ding kiln that arrived at the Haifengzhen and Haibei sites may have been shipped to Banqiaozhen, and then eventually sold to the Southern Song Dynasty. Although there were many markets along the border of the Southern Song Dynasty and the Jin Dynasty, long-distance transportation via overland roads could cause numerous unnecessary losses. Furthermore, in terms of the Ding kiln’s location, passing the Shandong Peninsula and arriving at the estuary of the Yangtze River was far more convenient than the alternative land roads and waterways. In the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, the porcelain found from the Southern Song Dynasty was significantly more abundant than in the rest of the southern area (Wu 2011), and may have arrived by this seaway.

On the other hand, the Haifengzhen and Haibei sites may also have been connected to the southern area via the Banqiaozhen site, for the trade of products including porcelain and other southern goods. A large part of the southern cargo arriving at Banqiaozhen needed to be transported to the inland or northward areas, however the traffic from here to the Central Plains would have been dominated by land routes. The porcelain, as a fragile product, may have continued to sail northeast around the Shandong Peninsula, with goods being unloaded at the Haibei or Haifengzhen sites, and then eventually, via the salt transportation routes, reaching the hinterland ofNorthern China. The Haibei and Haifengzhen sites are adjacent, meaning they could also have played the role of complementary suppliers, successively loading and unloading on the west coast of Bohai Bay. Moreover, as the southern porcelain sailed along the Yangtze River, and the east coast had already been established during the Northern Song Dynasty and the Liao Dynasty (Huang 2011), this route would likely still have played an important role during the Jin Dynasty and the Southern Song Dynasty (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The sketch map of the route for transshipment.

4. Conclusions

In summary, located at the northern side of the Shandong Peninsula and the area around Bohai Bay in the Jin Dynasty were the Haifengzhen site and the Haibei site, which may have been the main seaports for departures to the Korean Peninsula and Japan. These sites put the main Jin dynasty kilns of Northern China in the company of the kilns of the East Asian area, and made up some of the external seaport systems of the Maritime Silk Road.

In addition, through the analysis of the relationship between the porcelain unearthed in the port sites and some related relics, it can be inferred that the Haifengzhen, Haibei, and Banqiaozhen sites during the Jin Dynasty also had a domestic transshipment port system, along the Shandong Peninsula to the west coast of Bohai Bay.

In the past, many researchers have focused on the external function of these seaports, but we ought also to pay further attention to the internal relationships between these seaports in order to outline more completely the dynamic characteristics of the seaports involved in the Maritime Silk Road—not only in the Jin Dynasty, but also in relation to other seaports of this period.

Funding

This research was funded by the Chinese National Planning Office of Philosophy and Social Science, grant number [16BKG020]. [本文为中国全国哲学社会科学规划办公室年度项目“宋元时期海上丝路起始港及相关遗存的考古学研究”(项目号:16BKG020)的阶段性成果。]

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Cangzhou Municipal Administration of Cultural Relics. 2017. Cangzhou Cultural Relics. Beijing: Science Press, pp. 141–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Shaozhi, and Zhongmin Chen. 2014. A Number of Porcelain of Jin and Yuan Dynasty Were Discovered in Huanghua. Hebei Daily, August 27, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Yijun. 2011. The Importation of Porcelain in Liao Dynasty and Related Historical and Geographical Problems—Focusing on Blue and White Porcelain, National History. Beijing: Central University for Nationalities Press, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Huanghua Museum, Hebei Institute of Cultural Relics, and Research Center for Chinese Frontier Archaeology of Jilin University. 2015. Excavating Report of Haifengzhen Site in Huanghua City. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Yingmei. 2010. The Chinese Porcelain Unearthed in Koryo Sites Collected in Korea National Museum. Cultural Relics 4: 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kyoto National Museum. 1991. Special Exhibition of Chinese Pottery Which the Japanese People Like. Kyoto: Kyoto National Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xin. 2015. Prof. Senda: Ancient Chinese Maritime Porcelains Trade Series of Lectures. Porcelain Archaeological Communication 1. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Fengming. 2007. Shandong Peninsula and Oriental Maritime Silk Road. Beijing: People’s Publishing House, pp. 229–30. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Lin, and Wei Gao. 2008. A Briefing Report on the Stone Carvings of Liuzhizhou. Southeast Culture 3: 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Shanguo. 2010. The Porcelain of Jin Dynasty Unearthed in Northeast China. Northern Cultural Relics 1: 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Qingdao Institute of Cultural Relics Protection and Archaeological Research. 2014. The Catalogue of Archaeological Relics of Banqiaozhen Site in Jiaozhou City. Beijing: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qingdao Institute of Cultural Relics Protection and Archaeological Research, Huangdao District Museum. 2015. Investigation Report on the Survey of Cultural Heritage of the Silk Road in Huangdao District in 2014, Qingdao Archeology (2). Beijing: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Research Center for Chinese Frontier Archaeology of Jilin University, Hebei Institute of Cultural Relics, and Huanghua Museum. 2016. The Catalogue of the Porcelain Unearthed in Haifengzhen Site. Beijing: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jing. 2011. The Stages of the Song Dynasty’s Tombs in the Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River, Nanjing Museum Collection. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press, vol. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Bo, and Liping Chai. 2016. New Discovery of Haibei Site in Kenli County, Shandong Province. Huaxia Archeology 1: 38–44. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The item No. 32 recorded in this book is a scripture canister of white porcelain, discovered in Shikoku, it is possible that it’s a Ding Kiln product, and unearthed with a Huzhou Mirror, so we judged this piece should be in Jin Dynasty. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).