1. Introduction

Food poverty, food security, food integrity and sustainability are among the most pressing global challenges of our time. By way of illustration of the scale of the problem, in the next 50 years, we will need to produce more food than has been produced in all of human history in order to meet the needs of our growing populations.

1 More immediately, two-thirds of the world’s population, approximately 4 billion people, do not have reliable access to fresh water;

2 and in the UK today, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, 1.5 million people will go for a whole day without food.

3 Statistics have the power to shock. Equally potent are the widespread media images of famine and starvation in the ‘developing world’; images, commonly featuring children, which are flashed across our television screens to encourage charitable donations to NGOs. The apparatus of reason (statistics) and the apparatus of emotion (marketable images of human tragedy) are equally deployed, and the call-to-action they aim to solicit is freighted through the different forms of shock value they embody.

4 The present discussion seeks to propose a new way of thinking about the unique capacity of cultural artefacts—the focus of much Arts and Humanities research—to prompt a response

between emotion and reason, a response that has the potential to transform the fleeting reactions noted above into lasting social change. Further, and indeed, beyond these stark public communications of the multibillion-pound human tragedy of food security and food poverty, academic research in the field

is increasingly recognising the need to seek out multidisciplinary, multifaceted perspectives to tackle these challenges. The World Food System Center in ETH Zurich (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zurich), for example, has made a significant investment in this area, an investment built on promoting collaboration between scholars in Biological Sciences, Policy, Law, Management, Marketing, Engineering, Chemistry and Physics; while Queen’s University Belfast’s Institute for Global Food Security is likewise structured around multidisciplinary teams seeking to address the areas of ‘Farms of the Future’, ‘21

st-Century Nutrition Challenges’, and ‘Global Food Integrity’.

5 Yet while Social Sciences find a place at these tables, the Arts and Humanities are noticeably absent. If, as Arts and Humanities scholars, we are persuaded of the value of our research to wider society—for example, if we recognise the value of culture as a tool variously to enhance wellbeing, to navigate a new sense of belonging in a transnational world, to encourage community cohesion, and/or to influence behaviours and attitudes—why do Arts and Humanities scholars not appear as a matter of course in project teams working on global challenges such as food security and food poverty? Food poverty is just one example of a global challenge where the Arts and Humanities perspective risks being judged at worst to have no relevance at all, and at best to be included as no more than an accessible tool to facilitate public engagement and awareness-raising. How therefore can Arts and Humanities scholars articulate the value of their work in such a way that researchers in other relevant fields are persuaded not only that it brings something new to their understanding of the issues, but that to tackle such questions without this input risks leaving a major gap in the pathway to impact. I argue here that addressing this gap has the potential to initiate a genuine movement for social change.

6 Crucially, as will be explored throughout this discussion, that potential is based not on the promises of science and technology—that is, of ‘knowing’—but on the realities of uncertainty and ‘unknowing.’

The backdrop for this analysis is a broader reflection on the ‘disciplinary economy’ of university and other research environments in which Arts and Humanities scholars tend to be less prominent in global challenge research strategies, notwithstanding the rich collaborations emerging in the last decades in fields such as Environmental Humanities and Medical Humanities, the latter powerfully accentuated during the current Covid-19 pandemic. This discussion is thus also a reflection on the relationship between disciplinary and interdisciplinary working, with all of the latter’s challenges and possibilities. Research on interdisciplinarity has proliferated since the latter part of the twentieth century, with opinions constellating around the key concepts of ‘interaction’ and ‘integration’. Some scholars privilege the looser definition according to which any form of interaction between disciplines may be classified as interdisciplinary, while others advocate a more restrictive definition of interdisciplinarity based on integration and the consequent development of new synergistic approaches, theories or methodologies.

7 While influenced by the view that interdisciplinarity entails a modification of all of the disciplines involved, the present discussion is less focused on definitions than it is on the journey from disciplinarity to interdisciplinarity for Arts and Humanities scholars.

All disciplines operate within their own discourses in which a terminological ‘shorthand’ eases intradisciplinary communication; in other words, we use terms that form part of our own ‘technical’ discourse without being required to explain them to others within our discipline. Our interpretation of the work of art, for example, relies not only on formal stylistic devices and narrative strategies, but also on less ‘formally’ decipherable impacts such as the capacity to trigger empathy or ‘affect’. Indeed, it is this capacity which is commonly posited as the unique contribution of the Arts and Humanities. The challenge for us as a community of scholars, therefore, is to be able to ‘unpick’ and articulate the distinctiveness of what the Arts and Humanities

do that other disciplines do

not, without relying on this ‘shorthand’.

8 In their study of

Interdisciplinary Discourse, Seongsook Choi and Keith Richards trace a journey that begins with disciplinary enquiry, progresses to ‘interaction’ with other disciplines, and thence to ‘integration’ as the stepping-stone to the endpoint of interdisciplinarity (

Seeongsook and Richards 2017). However, I would argue that an additional stage is required following the disciplinary interpretation of a cultural artefact, and that is a stage of ‘

intradisciplinary exposition’ in which we elucidate,

for ourselves, what the Arts and Humanities do in ways that capture their distinctiveness and potential for impact, before beginning to engage with other disciplines.

Such an endeavour requires us to undertake a hermeneutic enquiry into precisely how the cultural artefact works. In this, terms such as ‘affect’ are core, terms which are slippery and elusive, and commonly not untangled within our own intradisciplinary communications. But what is ‘affect’? How does it work? The challenge to our community is that only by doing this work of ‘exposition’ can we think about translating our work to other fields in ways that move beyond public engagement and awareness-raising. The following discussion is thus divided into four sections that map onto the adjusted journey from disciplinarity to interdisciplinarity that I have proposed above, with the caveat that the image of a journey with four stages should be imagined as neither linear nor without digression, iteration or return. Indeed, innovation in disciplinary terms—like any other innovation—demands a flexible approach to prototyping within existing models.

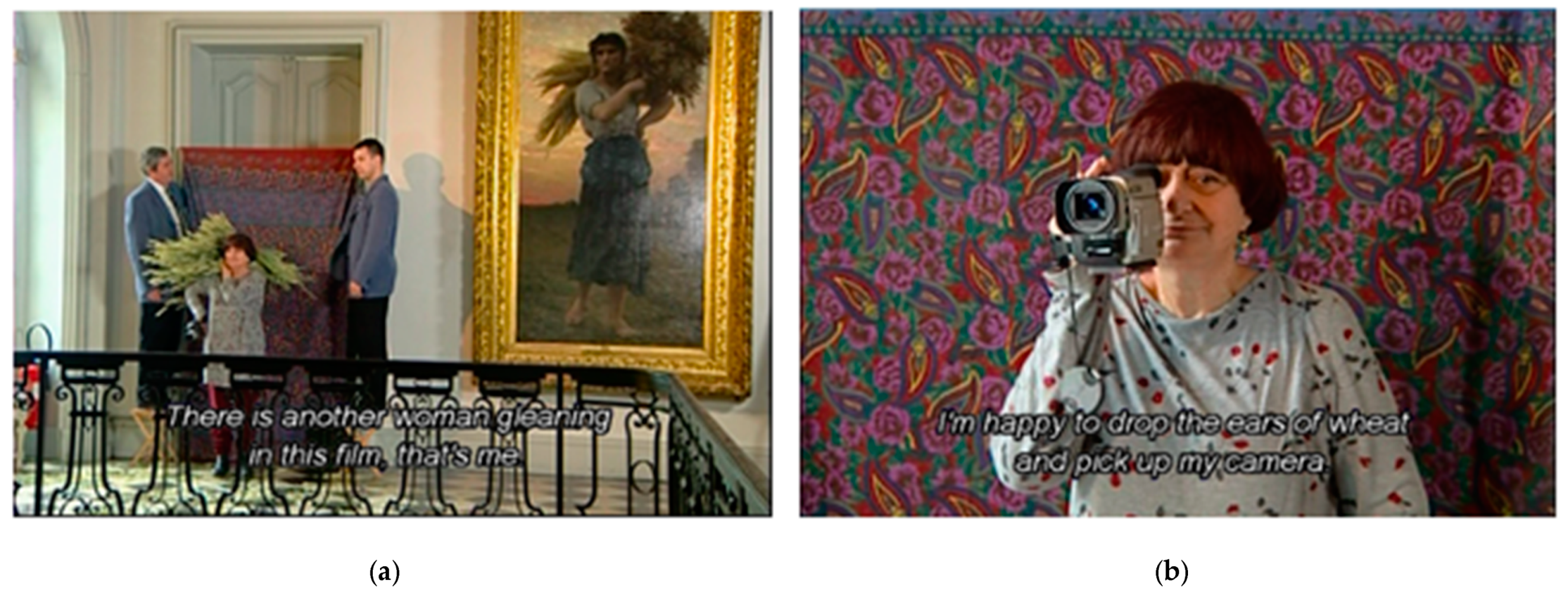

The first section, ‘Disciplinary Interpretation’, offers an analysis, from an Arts and Humanities perspective, of the strategies at play to tackle the question of food poverty in one particularly affecting cultural artefact, French filmmaker Agnès Varda’s

Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse [

The Gleaners and I] (

Varda 2000). The discussion could stand alone as a literary or filmic analysis of the kind published in journals in French Studies or Film Studies. It is, however, the wider scope permitted by the present journal, as well as the terms of this special issue, that enable a meta-analysis of the kind that I argue is essential to the work of interdisciplinarity: that is, what I describe, in the second section, as ‘Intradisciplinary Exposition’. This section represents an attempt to decipher what ‘affect’—that convenient disciplinary shorthand to sum up what is unique to the work of art—actually

is and

does, and this is posited as a necessary step towards meaningful ‘Interaction across Disciplines’, the focus of the third section. Here, I consider the enormous potential of an effective communication of what we do in terms of global challenge research, precisely because of the power of the Arts and Humanities to stimulate genuine behaviour and/or policy change, through an understanding of the function of ‘affective practice’. Finally, the last section on ‘Interdisciplinary Integration’ opens up to a longer-term project to develop a ‘toolkit’ to support equal, mutual and porous communication across disciplines.

2. Disciplinary Interpretation: Responding to Food Poverty in Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse

Relatively understudied among Varda’s broad and influential corpus,

Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse has not heretofore been considered through the lens I adopt here, i.e. that of travel and mobility studies, and the associated paradigms of cross-cultural encounter.

9 Yet, such a reading throws down an ethical challenge to the viewer, propelling him/her to attempt to disentangle, from the immediate, but fleeting, impact of hard-hitting statistics or the short-lived sensationalism of ‘poverty porn’, the intricate web of causes and effects, and of intersectionality with other socio-political and cultural issues, that underpins the tragedy of food poverty. That Varda’s unflinching gaze is directed at food poverty at home in metropolitan France, rather than in some distant ‘developing’ country, is central to its

affective force, a concept that will be explored further in the next section.

10 At the core of Varda’s film is the scandal of food wastage, a scandal progressively exposed in the course of a series of road-trips during which Varda travels along France’s motorways, punctuating this long-distance, high-speed travel with breaks in multiple locations where she engages with a diverse range of individuals and their stories, filming for the most part with a handheld camera. While on the motorway, Varda’s common visual focus is the succession of vehicles of mass circulation and consumption—that is, the trucks—that seem constantly to overtake her car; while during the breaks in her journeys, she meets people who are variously representatives of the food production industry, of supermarkets selling (and destroying out-of-date) produce, of those who are dependent on gleaning to survive (whether that is rummaging in bins in urban centres or, after the traditional model of rural gleaners, collecting the vegetables left after the harvest), of landowners who allow (or ban) gleaning on their property, of the lawyers who maintain the complex legislative position on that practice, and those who, more generally, salvage the casual cast-offs that are the symptoms of a society based on mass, cheap production, and reinvent them for different purposes. These include those salvaging waste to create works of both ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, and of course, Varda herself, who, as the ‘glaneuse’ of the title (

Figure 1a,b), gleans perspectives, experiences and encounters that are recycled into the artistic artefact which is her moving, humorous, fragmentary, internally incongruous, and, as such, unsettling film.

Exploring this unsettling effect in a 2003 interview, Agnès Varda situates the ethical challenge represented by her millennial film within a global frame which moves beyond the compartmentalised representations of food poverty with which this discussion begins, to disturb the boundaries between so-called ‘developing’ countries and a Western European nation:

Je peux vous dire que ce film “les glaneurs” a circulé un peu partout en France et dans le monde entier. Il pose partout le même problème. Ce n’est pas celui de l’économie durable, du commerce équitable, c’est celui d’une société organisée autour du fric, “du gagné”, une surproduction, une surconsommation, sur-déchets donc gâchis. Les combats sont à tous les niveaux. On peut essayer de freiner “l’esquintage” systématique des ressources naturelles. On peut faire un document sur les archis-pauvres d’Afrique du Sud, d’Inde ou d’Amérique du Sud. Ce qui m’a intéressée c’est dire “voilà, je vis en France, c’est un pays civilisé, “culturé”, riche et il y a des gens qui vivent de nos poubelles!” Cela a secoué plus d’un Français de voir ça.

[What I can tell you is that this film “the gleaners” has been shown more or less everywhere in France and across the world. It raises the same question everywhere. And that’s not the question of economic sustainability or of fair trade; it’s the question of a society organised around “dosh”, “whatever you can get”, excessive production, excessive consumption, excessive rubbish, and thus waste. The battle needs to be fought at all levels. We can try to slow down the systematic “trashing” of natural resources. We can produce a report on those in dire poverty in South Africa, India or South America. But what I was interested in saying was: ‘Look. I live in France, it’s a civilised, “cultured”, rich country and there are people who live off what they find in our bins.’ It’s shaken up many a French person to see that.]

Critical responses to the film have tended to downplay both cultural context and any ‘attempt to adapt the individual lessons in resistance [that her film represents] to a grander scale’ (

Tyrer 2009, p. 168). Yet the common critical emphasis on individual voices and self-expression both in, and in response to, Varda’s documentary film, belies the potency of what I would argue, drawing on the terms of philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah, is a ‘moral manifesto’ for cosmopolitanism, a guide to ethical living in a ‘world of strangers’, be that the stranger within, or the stranger without… our socio-economic other, as much as our cultural other.

12 In this part of the analysis, therefore, I use the lens of food poverty at home to read

Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse as a manifesto of cosmopolitanism which exposes and destabilises the value commonly placed on fixed notions of nationhood as the marker of cultural or moral capital; this manifesto encourages us to look differently—not in the sense, as Mireille Rosello notes in her article on the film (

Rosello 2001), of a mother scolding her children (as this paradigm too implies a set of cultural constraints and expectations)—but in the manner of an implicated participant for whom the boundaries of self and other are constantly redrawn. Phil Powrie explores the nomadic gaze which can be seen as a productive alternative to the binary paradigms to which Varda’s cinema is too often reduced (

Powrie 2011). As a visitor to the world of film criticism, I am much indebted to the work of specialist scholars of Varda, but as a researcher in the fields of travel and mobility studies with a particular interest in the ethics and aesthetics of representation and viewing, I would argue that

Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse offers a powerful critique of the circulation of people, goods, and ideologies of consumption. At the same time, it is suggesting new models of community that have less to do with culture or ethnicity and more to do with a stark confrontation with the shocking inequalities that exist within one’s own nation, and that cannot be quickly remedied for the viewer by a self-affirming donation to a charity working on distant shores. In realigning belonging in this way, Varda effectively dents the protective armour of nationhood; and, indeed, her explicit reference to (French) nationhood/conceptions of the nation in the interview quoted at the beginning of this section is subtly threaded throughout the film precisely in order to expose it as the marker of a particular idea of ‘Frenchness’, one which resists the assimilation of the ‘eccentric’ in order to safeguard a commoditised version of itself as a capital of culture endowed with cultural and financial capital.

It is as if Varda is suggesting that the average French person would not be ‘secoué’ [shaken up] by a documentary showing abject poverty in India, South Africa or South America, perhaps because compassion is easier to feel at a distance, because poverty and abjection are threatening when too close to home. It is as if the constant act of bending down (to pick up discarded food) that is reiterated throughout the film, including in the rap track (‘Rap de récup’) on which Varda herself collaborated with Agnès Bredel and Richard Klugman, and the loss of dignity that this may imply, is not appropriate ‘at home’.

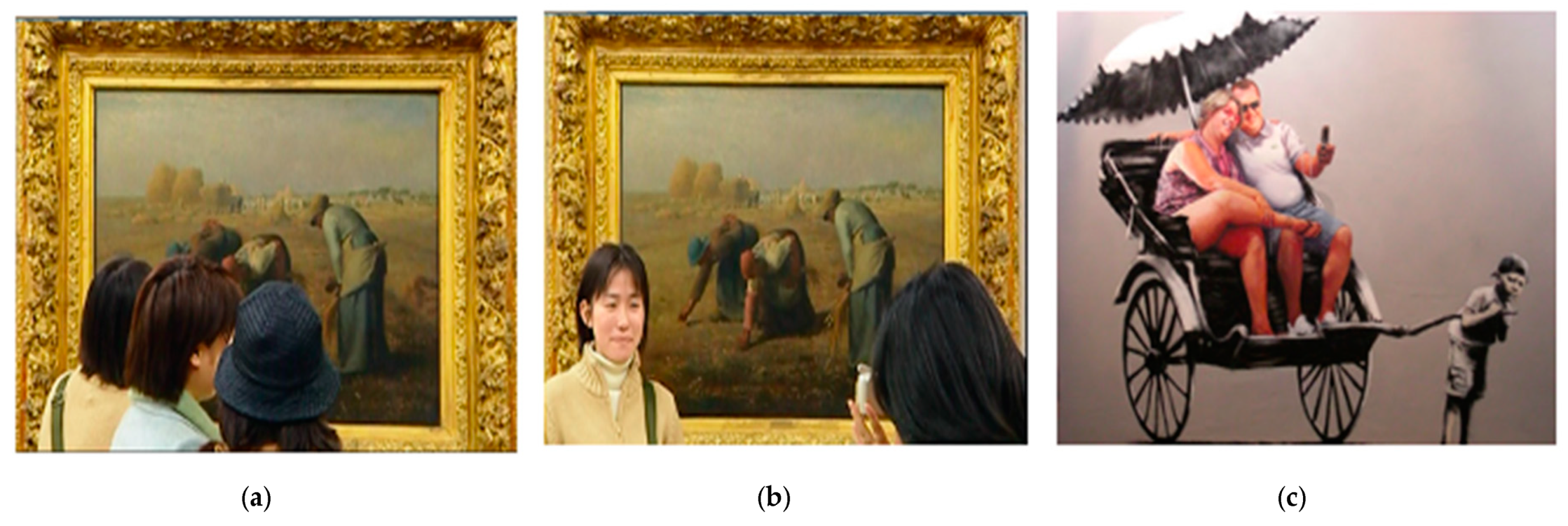

13The version of ‘home’ that is acceptable is that with which the film opens. This is France and specifically Paris that is part of a touristic imaginary centred on history, tradition and culture. Varda opens the film with Millet’s

Les Glaneurs which is exhibited in the Musée d’Orsay. This is the iconic and timeless representation of an idealised rural tradition, but our view shifts from a static vision of culture (both in the aesthetic sense and that of the European rural idyll depicted) to a sped-up montage of photographs of tourists taking shots of the Millet painting, most frequently with themselves positioned in front of it. The episode highlights the privileged status of those able to enjoy free circulation. Not insignificantly, many of those depicted are Southeast Asian; in other words, the quintessential—albeit caricatured—example of high-end package tourism, the whirlwind tour of Europe’s cultural highpoints (

Figure 2a,b). This is the age of modernity explored by sociologist Marc Augé who describes the proliferation of what he terms ‘non-lieux’ [non-places] i.e., airports, motorways, train stations, hotel chains as the symptom of supermodernity. These non-places are devoid of any relationality to history, identity, symbolisation, merely spaces of movement between (

Augé 1992;

Howe 2009).

As culturally and aesthetically rich a museum as the Musée d’Orsay does not appear to fit the description of a ‘non-lieu’, as proposed by Augé, and yet its original status precisely as a place of ‘movement between’ i.e. a train station, serves as a subtly ironic marker, when combined with the starting sequence, of the ways in which high-speed travel is less about the travellee than the traveller;

14 having one’s photo taken in front of cultural artefacts—here in front of Millet’s painting—is reminiscent of Banksy’s irreverent take on the system of touristic privilege which is more important as a guarantor of ‘having been there’—to be shared at some future time with extensions of oneself i.e., friends and family—rather than any ‘authentic’ engagement with the object of the photograph or with the travellee and the realities of his or her experiences (

Figure 2c).

As Christine Jordis notes satirically in her travel narrative

Bali—Java en Rêvant of the (admittedly overdetermined) tourist: ‘Le touriste n’a pas le temps de regarder, à peine de voir’ [The tourist has no time to look, scarcely even to see’] (

Jordis 2005, p. 123). The tourist’s camera offers the safe distance and the capacity to evacuate from the picture all that does not fit with expectations. For the tourist, Varda shows us, France is about Paris and its museums and culture. It is not about the messy business of human poverty and despair. This is a sanitised vision, and I would stress the importance of

vision—indeed, a form of ocularcentrism in which the world becomes spectacle for the privileged traveller/viewer. As Jean-Marc Moura notes, this is a process of ‘muséalisation du monde’ [museumification of the world] born of a ‘syndrome patrimonial’ [heritage syndrome] in which the whole world must be ‘étiqueté, préservé, sécurisé’ [labelled, preserved, kept secure] (

Moura 2008).

The link to Varda’s own comment—that appears as an apparently unconnected vignette later in the film—on the recycled materials with which children are encouraged to interact in the exhibition, ‘Poubelle, ma belle’ [My Beautiful Bin], is clear. She ponders: ‘Les déchets sont petits et jolis, propres et colorés. On se demande si les enfants ont vu une seule fois ce que balayent les balais ou s’ils ont jamais serré la main d’un éboueur?’ [The refuse is small, cute, clean and colourful. Have these children ever seen what the brooms sweep or have they ever shaken hands with a refuse collector?]. At this point the camera shifts to precisely that—a filthy broom brushing up the discarded waste which others are forced, out of economic necessity, to glean from the famous outdoor markets that are the urban manifestation of France’s agricultural traditions. The romanticised bubble of a land of health and plenty is abruptly burst.

If the tourists in the Musée d’Orsay are the unthinking beneficiaries of a celebratory globalism of the kind identified by Arjun Appadurai (

Appadurai 2004, pp. 220–30), if they are beneficiaries who are seeking and finding a commodified vision of Europe or France, how then does Varda move beyond that? How does she become a different sort of traveller, an ethical traveller in a world of strangers? I shall seek to answer these questions by highlighting a number of the specific travelling, and associated representational, strategies present in Varda’s film.

2.1. Deceleration: Human(ist) Encounter and Moral Discomfort

Notwithstanding the film’s opening sequence with its emphasis on high-speed movement, and, indeed, the frequent images of Varda in a car, on another quintessential non-place, the motorway, with repeated tracking shots of the trucks which are the tools of modern circulation and consumption (

Figure 3), the film is marked by a process of slowing down travel in order to facilitate a series of interpersonal encounters which seek to make visible the invisible communities of gleaners, notably those on the socio-economic margins (or indeed well beyond the margins) who are themselves frequently characterised by immobility in this era of supposed free movement. The most poignant example is Alain,

15 a man whom the viewer presumes is an alcoholic, and who was once part of this industry of commodity circulation—a truck driver—but who is now reduced to stasis, both physical and psychological. Having lost his job and family following a failed breathalyser test, he has not seen his children in two years because he has no physical means of travel, all the while living, ironically, in a touring caravan on wasteland beside a major road (

Figure 4).

Psychologically, too, his mental landscape centres on routines of gleaning potatoes from nearby fields and discarded produce from supermarket bins in order to survive within an ongoing cycle of exclusion. There is a poignancy in this image of running to stand still. There is no moral judgement in evidence on Varda’s part. The fact that she implicates herself, physically includes herself in the film, suggests how the line between viewer and viewed, documentary maker and subject,

inclu and

exclu, is a highly permeable one. Just as she fluctuates from the position of being behind, to in front of, the camera, so too does she remind us how fine the line is between privilege and under-privilege. Ending up on the wrong side of this line is not about weakness, inferiority, or blame, nor is it a tragedy that could befall only the inhabitants of India, South Africa, or South America, as opposed to ‘un Français’. It is, rather, to foreground chance as a vector for the direction our lives take. The frequent ‘digressions’ in which Varda focuses on her own experience of ageing, as embodied in her wrinkled hands and her grey hair, are directly linked to the kind of ethical ‘cosmopolitanism’ proposed by Appiah. For while a number of excellent analyses of this film have focused compellingly on the feminist elements of these scenes,

16 they may be read equally as a reminder of humanity’s frailty regardless of class, privilege, access to movement, culture or capital. These scenes are, of course, a

memento mori, but they also remind us of the impermanence of status and, indeed, the status quo, of the fact not only that we age, but also that we can take nothing for granted (

Figure 5). In presenting herself as ‘alien’, Varda is also shaking us out of our conventional ways of seeing; she is defamiliarising the familiar—after all what is more familiar than one’s own hand: ‘rentrer dans l’horreur; je trouve ça extraordinaire; j’ai l’impression que je suis une bête; c’est pire, je suis une bête que je ne connais pas’ [To enter into the horror of it; I find it extraordinary; I feel as if I am an animal, or worse, I am an animal I don’t know]. To borrow critical terms more associated with the study of travel writing, she is reversing the exotic gaze.

Sociologist and theorist of travel, Jean-Didier Urbain, famously writes in his 1998 book,

Secrets de voyage, ‘La banalité n’est jamais dans le monde, elle est toujours dans le regard’ [Banality is never in the world, it is always in the gaze]—a manifesto, if ever there was one, for seeing the world differently, whether that means seeing beauty or interest beyond the well-travelled tourist trail or daring to confront the dark underside of that well-travelled trail (

Urbain 1998, p. 438). Varda achieves both in this film. By slowing down travel and taking the time to speak to people, to get to know something of their lives, to let them tell their stories (as she tells hers), a different set of values emerges—based on dignity, compassion, and a new sense of community. The motif of stooping or bending down is a recurrent one, but as in the rap track on which Varda herself collaborates, and which provides the soundtrack to the series of shots of people bending down to pick up discarded food, ‘se baisser’ [bending down] need not equate to ‘s’abaisser’ [debasing/demeaning oneself] (

Figure 6).

17 On the one hand, this is a powerful moral reproach to a society which allows vast quantities of food to be wasted in the name of progress/technological advances/market values and which, as a result, brings people low, but it also marks a fundamentally humanist stance in that it recognises the value of individuals in their own right and in their capacity for compassion and creativity.

The other manifestation of this strategy of deceleration is evident in Varda’s filmic practice, for there are a number of episodes where the camera dwells at some length on particular objects or images with, as the only background sound, what Alyxandra Vezey describes as the ‘mournful’ refrain of Joanna Bruzdowicz’s original string-based composition for the film, ‘Aging-Agnès’, performed by alto violinist Yves Cortvint and cellist Luc Dewez.

18 The effect on the viewer is an unsettling one, unused as we are in the age of high-speed consumption, also reflected elsewhere in Varda’s cinematic practice in

Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse, to a lengthy focus on (near)/immobility.

Key examples include the camera’s lingering gaze on: the heart-shaped potatoes Varda begins to collect, potatoes that are rejected for commercial sale because of their irregular shapes (

Figure 7); the ageing process experienced by Varda herself, evident in her hands and her grey hair (

Figure 8a); the damp stains on the wall of her apartment which she fancifully imagines within a picture frame (

Figure 8b–d); and finally the slow and unflinching crawl of the camera over close-up details of images of torture and the agonies of the damned depicted in Van der Weyden’s painting,

The Last Judgement, which is displayed in the Hospices de Beaune (see below,

Figure 9).

These sequences disturb precisely because of their demand on our attention as, unsettled as we are by their often-unexpected appearance within the wider quotidian narrative, we cannot release our gaze, anticipating, as the viewer conventionally expects, that some meaning or explanation will be provided. Instead, the images continue to reverberate, frustrating explanation, and it is only on reflection that one can see a web of themes emerging which interconnect the film as a whole: compassion (the heart-shaped potatoes); fragility (the hands and hair), the need to look differently, particularly at the margins (the aestheticized damp stain), and the demand for an ethical position to be taken (the Van der Weyden painting). In these moments of deceleration, therefore, discomfort that cannot be dismissed or forgotten, like a statistic or a fleeting image of tragedy on the other side of the world, is inescapable.

2.2. Chance as Both Warning and Renewal

If, as noted above, Varda’s practice of deceleration, and her associated self-implication as fragile, serve to remind us that those in destitution are not fundamentally other, but could so easily be ourselves (and as such force a quite different response to the question of food poverty), Varda’s vision is not without the promise of renewal. Again, though, this is dependent on an openness to relinquishing control, to breaking down the barriers between self and other, to a displacement of not only what is statistically known (reason), but also what one is forced briefly and viscerally to feel in the context of high-speed marketing campaigns (emotion). The foundations of the work of a number of artists she meets are characterised precisely by this openness to chance, to challenge and to a carnivalesque reconfiguration of the normal placement of everyday objects, and this is precisely what enables a quite different perspective on our culture and environment. As one example, Varda explains how the celebrated artist Louis Pons ‘compose avec le hasard’ [accommodates chance] in his art. There is no pre-ordained vision, no certainties—only what chance allows one to create, such that one must respond to whatever is thrown one’s way and ask what can be made of it: ‘Pour les gens c’est un tas… un tas de saletés pourries. Pour moi c’est une merveille, c’est un tas de possibles’ [For most people, it’s a pile… a pile of rotten filth. For me, it’s marvellous, a pile of possibilities] (

Figure 10).

Just as Pons makes what he can with the objects he finds, so too, Varda seems to suggest, is our own situation a matter of chance that should not be subjected to moral scrutiny by others. Rather, moral scrutiny—as evident in her reflection on Van der Weyden’s painting—is reserved for those who ‘other’, or ignore, the plight of, those whose situation is less fortunate than their own. These artists who see beauty in what others have discarded range from the internationally recognised Louis Pons, to the young man, Hervé, who gleans in rubbish bins, not for food, but for objects he can make into artistic works, to the elderly man, Botan Litnanski, a retired bricklayer, who makes totem poles out of discarded dolls and other waste (

Figure 11):

Varda interviews the latter alongside his wife who rather comically queries the status of ‘artist’ which Varda attributes to her husband. Varda comments: ‘Mais votre mari est un artiste’ [But your husband is an artist], to which his wife replies: ‘Artiste, si on veut, hein’ [Artist, well, I suppose so]. Varda counters: ‘Parce que quoi?’ [What do you mean?], to which she replies: ‘Il y a encore mieux que ça […] Il y a encore mieux quand même’ [There’s much better than that out there […] Come on, there’s much better than that]. In this, the idea of the art work as something to be fetishized as a marker of social capital (as was evidenced in the Musée d’Orsay sequence) is replaced with the implicit assertion that the role of the artist and the value of his/her work is in prompting the consumer to see the world differently. This idea is neatly captured in Varda’s conversation with the artist Hervé (alias VR1999): when she asks him how he knows when and where to collect some of the larger items that he gleans for his artwork, he praises the leaflet provided by the local council which, in his words, lets people know when and where these discarded items can be found (

Figure 12): ‘“Pour biffer, on peut obtenir auprès des communes, des mairies, des petits plans dans le genre de celui-ci. On a toutes les rues, les secteurs, les jours auxquels on peut se rendre pour récuperer les encombrants”’ [To help you ‘load up’,

19 town councils and town halls provide little maps like this one. It shows all the streets, the districts and the days on which one can go and pick up these bulky items]. Varda comments ‘Je crois que ces papiers sont plutôt faits pour dire aux gens qu’ils peuvent déposer’ [I think they’re actually printed to show people where to dump things’] to which the artist responds, somewhat surprised, ‘Ah oui, c’est… effectivement …’ [Yes… right…], but concludes that he reads the maps in his own way.

Through her encounters with these artists, Varda proposes a new form of cultural capital which is not based on a hierarchical and commercialised vision of an aesthetic canon, but a form of co-creation for which the base materials have little material value but which are transformed, through human capital, into artistic objects. As Hervé notes of his pleasure in objects that have already had a life, ‘il suffit juste de leur donner une deuxième chance’ [you just have to give them a second chance’]. His unwitting call to action to support those on society’s margins echoes the reminder given to us by Indian economist, Amartya Sen, that ‘[p]overty is not just a lack of money: it is not having the capability to realize one’s full potential as a human being.’ (

Sen 1999).

2.3. Fragmentation and the Phenomenology of Perception

Francophone Swiss travel writer, Nicolas Bouvier, whose first text,

L’Usage du monde, published in 1963 and published in translation as

The Way of the World in 1994, has been described as a bible for a new generation of travel writers, describes his travelling philosophy as follows: ‘Je me bricole de petits morceaux de savoir comme on ramasserait les morceaux épars d’une mosaïque détruite, partout où je veux, sans esprit de système’ [I cobble together little pieces of knowledge just as one gathers the scattered fragments of a broken mosaic, wherever I wish, without any system in mind] (

Bouvier 2004, p. 1280). The quotation foregrounds the importance of chance, digression, a refusal of any preconceived systematising vision of other cultures and the too-neat labels which are frequently used to categorise them. The relevance to Varda’s approach to her own culture and its inhabitants in

Les Glaneurs is clear, and it is based on preconceptions of what France is, as opposed to the countries of the Global South she evokes in the interview with her that was quoted earlier in the present discussion i.e. India, Southern Africa, or South America. As will be discussed later, the effect is to turn the critical gaze back onto France and thus destabilise comfortable self-perceptions of a Western European nation as somewhere to which these ‘developing’ nations are fundamentally other.

This emphasis on chance and digression is also dramatised through the impression of disjointedness of Varda’s documentary that is reinforced by her use of the handheld camera. While there is a linearity to certain scenes e.g. notably of motorway travel, the style is in general dictated by a peripatetic gaze which juxtaposes fragments in ways that suggest new convergences, some of which have been detailed already. A striking example is the ‘dancing’ lens cap, a chance sequence created, apparently, without directorial agency and prompted by Varda accidentally leaving her camera filming with the lens cap off (

Figure 13). She includes what was filmed in the documentary, and a number of critics have persuasively commented on this sequence in terms of its ‘gentle mockery of the presumed infallibility of the documentary genre and its director’ or its ‘self-conscious form of documentary practice that favours […] revealing the transparency of the constructed image’.

20 What might be added to existing commentary on this scene is the physical disruption to vision it represents, and linked to this displacement of vision as a way to make sense of the world, the final setting of this sequence in the completed film to jazz music. Not only is this emblematic of a foregrounding of other senses, notably hearing, but jazz as a genre is arguably a significant choice in highlighting the ethical underpinnings of the film.

I have discussed elsewhere the ideological significance of relying on vision as the primary means of encountering the world in travel narratives, and how the displacement of ocularcentrism can be interpreted as a means of closing the gap between self and other, of relinquishing the safe position of spectator in favour of the fully imbricated—and more vulnerable—, multisensory experience of difference (

Topping 2019a, pp. 283–85;

2019b, pp. 194–206). Suffice it to reiterate here, therefore, that Varda implicates herself in the picture frame in ways quite unlike the tourist having their photograph taken in front of Millet’s painting in the Musée d’Orsay. She positions herself in the frame in ways that reinforce her own fragility; for she is not only subject to the inevitable processes of ageing, but she is also a person who is currently, but not necessarily permanently, on the ‘right side of the tracks’. As such, she resists the privileging site (here through the camera lens) and the sanitised distance it safeguards in an eschewal of the western ocularcentrism critiqued by Martin Jay (

Jay 1993).

There is thus a clear emphasis on the phenomenological in her perception, and telling, of her own story of gleaning. Likewise, the senses are implicated in her refusal to aestheticise experience: she comments critically on the school children’s sanitised engagement with recyclable waste; she focuses implicitly on touch and smell in the foregrounding of the rotting, heart-shaped potatoes or the stains left on her wall by damp. That she places a picture frame around the stain is more than a playful gesture; it is, as noted previously, a new unconventional form of art, creativity, and even beauty. In other words, Varda is enacting a multisensory experience of travel and gleaning, and the sense on which I would like to focus briefly here is the sense of hearing, particularly the presence of music in the film, in the jazz interludes and also in the rap track that features repeatedly throughout the film, the lyrics of which were written by Varda herself.

The association between jazz and improvisation with its suggestions of digression from a preordained path, and of instrumental encounters based on, and directed by, unpredicted encounters of rhythms to produce new cross-rhythms, links clearly to the earlier discussion of chance (

Topping 2015). Equally rap music includes jazz among its origins and is likewise grounded in processes of co-creation. The very concept of pre-ordained authority is thus undermined in these democratising forms. Both arise from marginalised communities, and in both cases artistic expression is precisely the response to that marginalisation, exclusion, or oppression.

21 While race/ethnicity was key to the emergence of both, the resonances for Varda’s documentary are clear. It is as if Varda is reminding us that these gleaners are the new oppressed, a fact that is all the more shocking

because it is an oppressed/excluded group within the Western European society of ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’, not—to return to the opening of this discussion—a ‘subaltern’ cultural other. This is the ‘Other within’—a phrase which is relevant to Varda’s film not in the usual sense in which it is used i.e., of migrant communities within the ‘host’ country, but ‘others’ linked by socio-economic exclusion. Varda is highlighting a social fracture, and not the one more commonly foregrounded in the French context i.e. an ethnic one. Indeed, her cast of characters is multi-ethnic—they are not aligned by, and excluded by, race, therefore; they are aligned by virtue of being part of a socio-economic sub-class that just happens to be multi-ethnic.

Food poverty thus becomes a more challenging proposition when lines of belonging are drawn not in global terms which distinguish ‘developing’ countries from the West, but when divisions are domestic and challenge the normative distinctions that often, in the French context, align communities with race and ethnicity. Examples of Varda’s insistence on seeing things differently and on compelling the viewer to see things differently have been explored throughout this discussion; but a reversal of the exotic gaze can also serve to other the self in ways familiar from such texts as Montesquieu’s

Lettres persanes or Swift’s

Gulliver’s Travels. Adopting the outsider perspective, viewing the apparatus of one’s own society as if from a distance, serves powerfully to reveal its absurdities, vanities, and certainties. And this trope of travel writing also makes its appearance in Varda’s film at moments of encounter with the emblems of state, authority, and a capitalist economy and logic. Absurd juxtapositions such as the judge who appears on a number of occasions in the film standing in a field of cabbages in all of his regalia (

Figure 14), reading aloud the tortuously complex legal position on gleaning from France’s Civil Code, allow for an outsider perspective on the absurdity of these laws, as does the juxtaposition of the interviews with the three parties to a recent prosecution for infringement of these laws: a local magistrate, a supermarket manager, and a group of young homeless people who have taken food discarded by the supermarket and left in bins outside, because, even though it may still be edible, it has passed its display-by date. The supermarket manager responds by dousing the discarded food in bleach so that no-one can eat it, and the young people vandalise in response. Each protagonist defends his/her position. Varda actively condemns none of the parties, notwithstanding the playful hints of pressure she exerts on the magistrate and supermarket manager when their repeated responses fail to go beyond a rote reference to what is allowed and what is not allowed in law or in company policy. Equally, the young people arguably perform an exaggerated version of victimhood. As such, the juxtaposition creates a tacit parody of both the unthinking reliance on facts/statutes/policy and of the appeal to the emotions on the other.

22 In that in-between space, the viewer is not told how to respond, but is compelled to reflect on their own responses, and in that space, a new sense of community can emerge, the prime example of which is the figure of a young man who appears in the latter part of the film, but to whom Varda then dedicates a sustained focus which is taken up again in her short follow-on film,

Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse, deux ans après [

The Gleaners and I: Two Years Later].

Matter of fact and pragmatic; susceptible to no rhetorical posturing; neither victim nor hero; he simply goes about his daily routine, a routine initially only observed by Varda, which involves him coming each day at the end of the food market near Montparnasse train station, and gleaning mostly bread, fruit and vegetables left behind at the end of the market (

Figure 15a). When Varda does eventually approach him and strike up a conversation, he talks of his preference for these food groups, specifically with reference to their nutritional value, but makes no mention of his personal circumstances; that is, he seeks no pity.

It is only over time that Varda comes to discover that he has a Master’s degree in Biology, lives in a hostel mostly inhabited by immigrants, that to make money, he sells a paper outside Montparnasse Station each day, and that when he returns to the hostel in the evening, he spends his time providing free language lessons to (non-Francophone) residents in the hostel (

Figure 15b,c) Like those featured elsewhere in the film who work for the charity, Les Restos du Coeur,

23 who drive out from the cities to the countryside to glean potatoes left behind from the industrial processes of harvesting (usually the potatoes which are too small to be picked up by the machines and which would be too small to sell in supermarkets) and take them back to distribute to those in food poverty, this young man is the embodiment of quiet compassion, altruism, and, to return to Appiah’s definition, of ‘ethical living in a world of strangers’. None of this is stated explicitly by Varda; she shows, rather than interprets or pronounces; she does not expressly condemn or laud. Rather, she provokes an ‘affective’ response which, as I will argue in the following section, is where ‘mindwork’ begins and which is the unique capacity of the work of art.

3. Intradisciplinary Exposition: Understanding Affect

Woven into the preceding discussion of Varda’s film is a range of recurrent features: a preference for showing rather than telling, but unlike the marketable images of human tragedy associated with the kinds of charitable campaigns evoked at the beginning of this article, a form of showing that demands self-implication and an embodied engagement; by extension, a phenomenological response that replaces ocularcentrism and spectacle; an unsettling sense of difference, and the challenge of making sense that follows initial disorientation, as in the embodied, near-claustrophobic experience of a minutely focused discovery of the Van de Weyden painting or the disturbing close-ups of Bodan Litanski’s doll totem poles; the removal of the usual apparatus, such as sound, that is used to create a sense of distance and a space for sense-making; a defiance of logic; and a defamiliarizing of the everyday. In this section, these features are identified as moments of ‘affective practice’ that have the potential to prompt lasting action by stimulating in the viewer what I term, following the definition of Alexander W. Astin, ‘mindwork’. Moments such as these are not replicated in the encounter with either stark data (the apparatus of reason) or sensationalist representations of tragedy (emotion), and this, I argue, is the unique contribution of the Arts and Humanities to global challenge research.

The concept of ‘affect’ is, however, understood differently across a range of disciplines; it barely figures in some; and for many, it is used interchangeably with ‘emotion’. The term is attributed to psychologist Silvan Tomkins whose 1962 study,

Affect Imagery Consciousness, used it to refer to the ‘biological portion of emotion’, or what he defined further as the ‘hard-wired, pre-programmed, genetically transmitted mechanisms that exist in each of us’ and which, when triggered, prompt a ‘known pattern of biological events’ (

Tomkins 1962, p. 15). For example, we blush when embarrassed, we raise our eyebrows when surprised, cry when distressed, frown when puzzled, and so on. From these origins spring medical diagnoses of certain psychological conditions in which patients display ‘flat affect’, that is an absence of the expected, appropriate response to a given situation. From this context, affect has been adopted by disciplines focused on interpersonal communication, and in the work of critical theory, it has become a way of thinking through reader/audience reception.

24 Yet scholars have also taken issue with these uses, notably criticising affect theory for its imprecision, and claiming, as does Aubrey Anable, that its ‘language of intensity, becoming, and in-betweenness and its emphasis on the unpresentable give it a maddening incoherence, or shade too easily into purely subjective responses to the world’ (

Anable 2018, p. 6).

This is the challenge for us as Arts and Humanities scholars seeking to translate the value of our methodology to other fields of enquiry, for meaningful interaction and the ambition for interdisciplinary integration require both a concise articulation of what Arts and Humanities research does that other disciplines cannot, and a methodological clarity that rescues literary and artistic criticism from, at best, ignorance or misunderstanding in other disciplines, and from, at worst, accusations of subjectivity or an ‘unscientific’ reliance on ‘emotions’ and ‘intuitions’.

How emotion works, and how it is variously constructed, presented, articulated, felt, embraced, refused, displaced, or projected in the Arts and Humanities is an area where the tension between a critical and a subjective vocabulary is potentially blurred. Yet philosopher Dylan Evans argues that the scientific study of emotion is not only possible but of great value—not because emotion can be reduced to a dry formula, but rather because ‘thinking more clearly about emotion need not be opposed to feeling more deeply’ (

Evans 2002, p. xiii). In drawing a distinction in the course of this discussion between different strategies used to raise awareness and call people to action about the tragedy of food poverty, I have established a distinctly binary opposition between reason (as exemplified in empirical data) and emotion (as exemplified by sensationalist marketing campaigns), but, to respond to Dylan Evans, thinking more clearly about emotion—and, as noted above, how it works within an artistic artefact—is key to problematising that binary in ways that demonstrate how the work of art has a unique capacity to use emotion and reason with

near-

simultaneity in ways that move the viewer, and that have the potential to lead to meaningful action for social, economic, and policy transformation.

As I will argue more fully below, the space where this can happen—the space of near-simultaneity as between emotion and reason—is the affective moment, the definition of which is perhaps more accurately conveyed by the idea of ‘affective shock’. In proposing this notion, I draw on Victor’s Segalen’s painstaking engagement with the sharp sensory experience of exoticism which he articulates in terms of ‘le choc du Divers’ [the shock of Diversity],

25 and in which exoticism is understood not as Orientalist cliché, but as the lived encounter with difference of any kind. In this, affective shock harks back to the biological responses categorised by Tomkins, for the idea of shock implies the embodied response to the phenomena one perceives before it is theorized, interpreted, or explained. To achieve this requires the viewer to be placed in a position of hermeneutic phenomenological reading at which point an affective shock prompts a more tentative, more contingent, and thus necessarily more incomplete analysis that, by its very refusal of abstract categorisation, continues to resonate as intellectual and emotional conundrum for which quick responses do not suffice. This, I argue, is the space of ‘mindwork’, where unconscious responses to human tragedy become conscious conundrums in search of different, lasting solutions. It is also the space in which we find ourselves when confronted with the frequent moments of epistemological uncertainty, of sensory disorientation or deprivation, of a defamiliarized reality, of implied confrontation with our own fragility, of self-implication in the experience of those who have suffered a tragic loss of social status, and with the unsettling, unexplained juxtapositions that, as identified in the preceding section, characterise the tones and textures of Varda’s film.

In exploring these ideas, I draw on cultural theorist, Stuart Hall’s, analysis of the different positions adopted by the consumer of a visual artefact (

Hall 1980, pp. 117–27). The first of these is the dominant-hegemonic position in which the consumer of an artefact accepts its meaning directly, decoding it as it was encoded by the producer. The consumer is located within the dominant point of view (the view of the producer) and shares fully the text’s codes and accepts and reproduces the intended meaning. The second position is the negotiated position which is a mixture of accepting and rejecting elements. Readers are acknowledging the dominant message but are not willing to accept it completely in the way the encoder intended (an example would be being immersed in enjoyment of a rom-com while also maintaining an element of critical and/or ironic awareness of the commodity that has been created to produce a particular set of responses, as opposed to a wholesale unquestioning consumption of it). In the negotiated position, the reader, to a certain extent, shares the text’s codes and generally accepts the preferred meaning, but is simultaneously resisting and modifying it in a way which reflects their own experiences and interests. Lastly, there is the oppositional position or code in which, Hall argues, a viewer can understand the literal (denotative) and connotative meanings of a message while decoding a message in a globally contrary way. Thus, the consumer’s social situation has placed them in a directly oppositional relationship to the dominant code, and although they understand the intended meaning, they do not share, and ultimately reject, the text’s code.

Whether our response to the representation is to adopt a hegemonic position (visceral agreement/endorsement) or an oppositional reading (visceral rejection), whether we respond with pleasure to an image, or whether our instinctive response is revulsion or disgust, neither of these positions is challenging our preconceived notions. These instinctive, emotional responses allow us to confirm what we already think, not to disrupt it. We are not being pulled up short in the presence of a form of difference of which we cannot immediately make sense. It is the negotiated position, therefore, which allows for a visceral reaction, but which is also tempered by an awareness of the ‘constructedness’ of the representation and which can therefore create the genuine conditions for challenging preconceptions. This, I argue, is what happens in Varda’s film when, for example, no explanation is provided for the slow, lingering focus on the Van der Weyden painting in a lengthy scene which has no explicit relevance to Varda’s narrative or journey. As viewers, we are unsettled, and it is this which prompts an affective response which demands ‘mindwork’ on our part. Following this unexplained immersion in this painting and consequent mindwork, one possible interpretation is that the kind of moral judgement that is too often focused on those on society’s margins may in fact be reserved for those who ‘other’ or feel no compassion for the plight of those whose lives have, often by chance, digressed into a position of poverty or disadvantage. That is where the representation of emotion can shift into affective practice and where emotion and reason can productively interconnect.

The so-called ‘turn to affect’ in the last decade or so has led a wide range of disciplines to consider how the concept might apply to them. Margaret Wetherill has written a short but powerful work on emotion and affect in terms of a methodological approach in the Social Sciences that reflects the significant shifts, centred around the so-called ‘paradigm wars’ of the late twentieth century, to include not only quantifiable data and testable hypotheses as the work of the Social Sciences but also qualitative, interactive methods such as those traditionally associated with the Humanities (

Wetherell 2012). For Wetherill (and others), the core definition of ‘affect’ goes beyond the commonly-accepted distinction in which emotion refers to physiological, neurological, cognitive experience of fear, disgust, anger, surprise, happiness and sadness, and affect to the distinctive perturbations they cause primarily in the body such as blushes, sobs or outbursts of laughter. Wetherill focuses, rather, on affect as something that can be ‘generalised as the process of making a difference’ (

Wetherell 2012, p. 3). She draws on the work of Gilles Deleuze in seeing affect as ‘influence, intensity and impact’ and part of a philosophy of ‘force, becoming, potential, encounter and difference’ that enables us to consider affective phenomena and their consequences. She settles on the term ‘affective practice’ for her pragmatic approach to the study of emotions, noting that it is ‘capacious enough to extend to some of the new thinking available about activity, flow, assemblage, and relationality’ (ibid.) that is drawn from Deleuze and seeking a practical outworking for research (in her case Social Sciences). ‘Affective practice focuses on the emotional as it appears in social life and tries to follow what participants do. It finds shifting, flexible and often-overdetermined figurations rather than simple lines of causation, character types and neat emotion categories’ (

Wetherell 2012, p. 4).

26 What is particularly suggestive in the context of the present reflection on Varda’s film, and the role of the Arts and Humanities more generally, is the focus on

becoming in the face of difference, the sense of attention needing to be interrupted and continually refocused for preconceptions of culture to be disrupted as, for instance, when Varda challenges the expectation that food poverty is acceptable in a ‘developing’ nation, but not ‘at home’, in France.

27 Moreover, what prompts this affective response, I would argue, is the presence of a hermeneutic phenomenology that is particular to artistic artefacts such as Varda’s

Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse.

These are moments of affective shock that emerge in the shift from an ‘affective practice’ on the part of the producer of an artefact to the phenomenological experience of ‘affective shock’ on the part of the receiver of the work of art. It is that moment of shock which allows for a negotiated position that replaces the binary of reason and emotion, with which this discussion began, with a near-simultaneous experience of both which prompts lasting reflection. This is what I term ‘mindwork’, and I adapt it from the work of Alexander W. Astin, Emeritus Professor of Higher Education at UCLA, for whom the term refers to raising into consciousness that which is unconscious, a capacity to observe one’s own mind in its processing of thoughts and feelings (

Astin 2007). Astin’s premise is that the absence of ‘mindwork’ is at the root of many domestic and world problems. By implication, therefore, ‘mindwork’ has the capacity to prompt activism and create social change. Why this potential is not realised, however, is because, ‘while we are justifiably proud of our “outer” developments in fields such as science, medicine, technology, and commerce, we have increasingly come to neglect our “inner” development—the sphere of values and beliefs, emotional maturity, spirituality and self-understanding’ (pp. vii–viii). Astin’s conceptualisation of ‘mindwork’, of course, draws on Freudian psychoanalysis, but his approach resonates powerfully for the current discussion more in the sense of an enforced shift from passive being/doing to active thinking, as in Marcel Proust’s famous evocation of involuntary memory on dipping the madeleine into his tea as the trigger for the unravelling of the masterpiece that will become

A la recherche du temps perdu. What ultimately emerges for the narrator of Proust’s novel are unconscious memories, in a Freudian sense, but what is important for the present discussion is the process by which an everyday occurrence, undertaken without thought, suddenly provokes a moment of disturbance, of ‘unknowing’, and a realisation that some deeper idea needs to be dragged up to active thought. (Mind)work is required for that to be achieved, and that is the position in which Varda’s film places us.

4. Interaction Across Disciplines: The Challenges and Possibilities

The key challenge of multidisciplinary working is that each discipline’s own critical discourse is not easily translated. In this respect, and given the emphasis in the discussion of Varda’s film on travel and (im)mobility, travel across disciplines might be viewed through the metaphorical lens of physical border crossings. Speaking primarily of physical movement, for example, comparative literature scholar Emily Apter has exposed what she describes as the bourgeois fiction that globalization has turned everyone into ultra-mobile cosmopolitans, pointing instead to the phenomenon of intensified checkpointization, that is, of increased physical and metaphorical borders and border controls.

As the Senegalese philosopher, Souleymane Bachir Diagne, notes of his own experience as a traveller in this age of global mobility, his is ‘the passport that does not pass ports’ (

Diagne 2013). It is, rather, a devalued document whose bearer is generally to be considered suspect. Hence, physical border controls become the sites also of psychological and cultural borders. To add to this example, one need only mention the shift to the right in European, UK and US elections to find examples of populist anxiety about other cultures which creates and maintains psychological borders, while also reinforcing concerns about the need to heighten physical borders. Emily Apter therefore calls for a move away from discourses of celebratory globalism—the positive visions of free movement and democratic cultural exchange such as those voiced by Indian postcolonial theorist Arjun Appadurai. She proposes, instead, a focus on ‘the untranslatable’, on what cannot cross borders, is not willingly permitted to cross borders, whether literal or metaphorical (

Apter 2013, pp. 99–114). Apter’s concept is thus a suggestive one not only for the patrolling and protection of geopolitical borders, but for the preservation of (psychological) difference, be that difference from one’s cultural other, or socio-economic other. On a still more metaphorical plane, it also chimes with the processes of disciplinary territorialisation that the present discussion seeks to challenge.

I would like to suggest here that artistic representation—the focus of much Arts and Humanities research—is a privileged site for building, dismantling, or revealing the fissures in these borders and checkpoints. In terms of building borders, our contemporary news-scape reveals countless examples of post-truth, visual messaging being used to promulgate anxieties about other cultures; but the Arts and Humanities can offer productively challenging alternatives based on that sense of untranslatability that allows for a shift from emotion to affect, as for example, when we are forced to reflect on the discomfort prompted by the borders Varda highlights being internal, socio-economic barriers to inclusion, rather than cross-cultural ones. In those moments of rupture, in the presence of a difference one cannot quite ‘pinpoint’, new ways of thinking, new flows and becomings—or to recall Hall’s terms, a negotiated position—emerge.

Might we therefore consider Arts and Humanities researchers as coalition-/social movement- ‘brokers’ to use terms drawn from Sociology,

28 who act as translators of the work of art and who, as such, are key to prompting the kind of active user engagement with ideas, processes, policies or technologies that leads to genuine change. In a research culture which by definition prizes the pursuit of knowledge, let us also recognise the importance of ‘unknowability’, and the fact that part of the role of the Arts and Humanities scholar is to translate the inevitable reality of untranslatability and, specifically, its value in prompting the sort of mindwork that comes from an acknowledgement of the tension between emotion and reason and its power to create moments of affect. The potential for this lasting sense of challenge, or ‘disruption’, to develop into sustainable action far surpasses the short-lived shock caused by the kinds of statistics or emotive images with which this article began. Crucially, too, this will be action that is grassroots and based on co-creation rather than knowledge bestowed unilaterally by university-based experts, for the unique value of the work of art is that it obliges the reader/viewer to do their own mindwork. Thus, while sociologist James M. Jasper has notably brought the study of culture and emotions into scholarship on protest movements, even introducing the concept of ‘affective commitments’ in his 2018 study,

The Emotions of Protest, his work does not engage with the role and possibilities of works of art—and their study—as stimuli for the kind of genuine movement-building that comes from our affective self-implication in them (

Jasper 2018). This, I have sought to argue here, is a key contribution of the Arts and Humanities to global challenge research, but one that, as explored in the second section of this discussion, if it is to be fully realised, requires us as a community of scholars to undertake our own ‘mindwork’ as to what our disciplines do.

5. Discussion: Towards Interdisciplinary Integration?

The present analysis began by suggesting that the potential benefits of an interdisciplinary collaboration between the Arts and Humanities and those disciplines which tend to dominate global challenge research was based not on the epistemological promises of science and technology—that is, of ‘knowing’—, but on the ontological realities of uncertainty and ‘unknowing’. In this, I have implicitly reflected on the disciplinary economy of universities which may be seen to imply a hierarchy among disciplines based on theoretical orientation (hard or soft) and knowledge application (pure or applied). This typology yields the following categories: ‘hard-pure’ disciplines (natural sciences such as Physics), ‘soft-pure’ disciplines (Humanities and qualitative approaches within the Social Sciences), ‘hard-applied’ disciplines (such as Mechanical Engineering or Computer Sciences) and ‘soft-applied’ disciplines (for example, applied Social Sciences such as Education). As noted at a number of points in this discussion, the boundaries between disciplines are becoming ever more porous—notably via the ethnographic turn in Social Sciences and in the development of new multi-disciplines such as Medical Humanities and Environmental Humanities. What unites them all, however, is a privileging of knowledge (its acquisition, dissemination and relative status within the Academy), as is noted by Steve Fuller when he describes how ‘a discipline is “bounded” by its procedure for adjudicating knowledge claims’ (

Fuller 2002, p. 191). The transformative outputs of ‘hard-applied’ disciplines such as Computer Sciences and Engineering have only intensified the democratisation, and apparent ‘guarantee’ of knowledge beyond the specialist world of the university: most obviously, we live in a world where Google has become an immediately accessible knowledge resource for the majority of the population. Google certainly does not replace academic expertise (for it offers only the pretence of complex knowledge); nonetheless its constant availability reinforces the presumption that there is an ‘answer’ to all questions and that ‘knowledge’ is there for the taking. Indeed, the more Google conveys a sense of complete knowledge, the less we are really informed about the deeper dimensions of the issue we are exploring. Illusion is the result; not understanding.

In his latest book,

New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future, the artist and writer, James Bridle, offers us a warning about a future in which the contemporary promise of a new technologically-assisted Enlightenment may just deliver its opposite: an age of complex uncertainty and the hollowing out of empathy (

Bridle 2018). Bridle—whose own disciplinary background is Computer Sciences—highlights the tension between our contemporary cultural and academic emphasis on the quest for, and promise of, ‘knowing’ (in which logic, often powered by technology, is the key), and the position of ‘unknowing’ that this has directly produced. By way of illustration, he describes an Amazon warehouse in which stock is not organised by type, but rather by a complex set of algorithms that dictate the most efficient movements for collecting the stock for distribution on receipt of an order. The result is a structure that simply cannot be navigated by human intuition. As he explains:

The reason Amazon workers need hand-held devices to navigate around the warehouse is because it is otherwise impenetrable to humans. Humans would expect goods to be stored in human-type ways: the books over here, DVDs over there, racks of stationery to the left, and so on. But to a rational machine intelligence, such an arrangement is deeply inefficient. Consumers don’t order goods alphabetically or by type; rather they fill a basket with goods from all over the store—or, in this case, the warehouse. As a result, Amazon employs a logistics technique called ‘chaotic storage’—chaotic, that is from a human point of view’

(pp. 114–15)

Products are sorted by association rather than type (books beside saucepans, televisions beside children’s toys), thus allowing for shorter paths between items. The outworking of this logistical process which is incomprehensible to humans is, for Bridle, that it ‘accelerates their oppression. […] They have nothing to do but follow the instructions on the screen, pack and carry. They are intended to act like robots, impersonating machines while remaining, for now, slightly cheaper than them’ (p. 116).

Bridle’s book thus focuses on the tension between knowing and unknowing, control and confusion, reason and emotion in this age of technological and scientific advances; and it stands as a warning that, without a critical reflection on these tensions, we risk sliding toward an era of apathy and indifference, and toward a culture that prizes knowledge, science and reason to such an extent that it has stopped questioning its assumptions about human value. What Bridle foresees is a culture that, at worst, has completely lost the power to empathise, and at best has lost sight of the absolute necessity of empathy and emotion as drivers of change. Crucially, this is not empathy or emotion in the form of the brief shock value of images in charitable campaigns, for their short-lived impacts rely on one-dimensional representation and cannot detail the multifaceted causes and effects—of, for example, food poverty—and the intersectionality at the core of human deprivation and degradation that makes an uncomfortable bedfellow for our society of over-consumption. As noted also in the discussion of Niger-Delta poetry by in this issue, ‘hypercapitalist greed’, fed by a technologically-fuelled economy, is at the core of human alienation. For the authors, therefore, the arts and humanities offer a challenge to, and subversion of, the Anthropocene (

Abba and Onyemachi 2020).

But might an alternative reading of the relationship between ‘knowing’ and ‘unknowing’ be possible? For Bridle, the privileging of a certain type of ‘knowing’ risks creating a society in which individuals do not know how to think, act, or empathise. As is clear from the example of ‘chaotic storage’ in the Amazon warehouse, the algorithms which dictate where items are shelved—while an astonishing feat of technology—mean that the human operators require no knowledge, have no agency, and ultimately replicate the ‘robots’ that will most likely replace them. However, an alternative would be to turn this dynamic on its head and identify ‘unknowing’ as a powerful trigger for empathy and for the recognition of human value, especially the value of those on the margins of society who arguably, like Alain in Varda’s film, have the least agency. This is where the cultural artefact—the object of much Arts and Humanities research—can be positioned i.e., as the pivot which forces us to seesaw between ‘knowing’ and ‘unknowing’ and which therefore obliges us to do the difficult work of balancing. The work of art is a construction that can be conceived in such a way as to place the viewer in a position of uncertainty, understood not in the postmodern sense that everything is representation or in relation to a Habermasian post-metaphysics, but simply in the sense that we are not provided with answers, interpretations or even, at times, as we have seen in Varda’s film, with clarity as to the logic or relevance of various scenes. We are placed in a position of confusion and disorientation, one that in Varda’s film, unsettles received wisdom about the distinction between ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ nations, about what constitutes beauty, capital and value, and about our own security as educated, mobile, cosmopolitans. Arts and Humanities scholars understand and interpret how that happens, how audiences respond, and crucially, therefore, how this can be deployed to galvanise consumers of the work of art to reflect on their own responses to those we might conveniently see as ‘other’, and as such to allow for a new vision of community and a new activism to emerge.

What, then, does that mean for the possibilities of interdisciplinary integration? Certainly, if research is defined as the relentless pursuit of knowledge and impact, it is no doubt counter-intuitive to prize the refusal of knowledge, the power of ‘unknowing’ as an essential part of that teleology. Scientists necessarily progress towards their destination via a digressive journey that includes wrong turns, temporary halts and stuttering starts, but science (in the broadest etymological sense of knowledge), remains the end-goal. And yet, in our increasingly digitally-defined age, tech companies, for example, are recognising the need to employ Humanities graduates as a means to maximise the chances for user acceptance of technological innovations, or in the broadest sense, of scientific discovery. AI developers, for example, are seeking to recruit creative writing graduates and literary scholars, precisely because they recognise that if AI is to be our future, and if AI companies are to achieve commercial success, they must ensure that it will be adopted by the average user, but this will not happen without a human-robot interaction that is underpinned by empathy. The successful translation of technological research into genuine societal impact is, in other words, dependent on a humanist translation. While this example diverges from the precise path of the argument made in the present discussion about the unique potential of the work of art, it does demonstrate an intuitive sense, in the commercial world of technology, of the importance of the emotional, the irrational and the untranslateable, on which Arts and Humanities scholars can build.

We return then to the fundamental challenge set out at the beginning of this discussion, namely how to move beyond the fleeting shock of hardcore statistics on the one hand and heart-rending visions of human tragedy that encourage viewers to charitable donation on the other, or how to find a new way of conceptualising the relationship between reason and emotion on which these calls to action to address the tragedy of food poverty and food security typically rely. For this is central to the question not only of how research is translated into policy (a key remit of disciplines such as politics) but, crucially, the question of how it moves beyond that status as policy into a genuine will for change, a challenge to individual agents to think differently, and ultimately from that to the kind of ‘movement-building’ that leads to action and activism; for if policy can regulate and legislate for changes in behaviour, it cannot ‘win hearts and minds’ in such a way that drives action for change beyond minimum compliance.

29Physical travel (Varda’s road trip) and metaphorical travel (across disciplines, and across psychological and social borders) have been core to this discussion, both demanding a phenomenological effort on the part of the traveller, a trigger for mindwork that, when freighted through the work of art, has the potential to lead to an ethical realignment in relation to both our cultures and our disciplines. James Clifford has famously advocated the idea of the ‘Greater Humanities’, not as a bid to capture or hold ground in the disciplinary battles for recognition within institutions, although he recognises this as our reality, but as a higher goal and way of thinking that will ultimately allow us to move beyond disciplinary affiliations in recognition of the epistemic affinities that already unite many of our disciplines. He concludes his short essay on the subject saying,

My remarks are a reminder to keep our eyes on a larger prize, even as we fight more immediate battles for resources and recognition. We need to strengthen existing affinities with the goal of creating a multiplex, adaptive knowledge-space that is fundamentally interpretive, realist, historical, and ethico-political. If we can achieve this, in a changing university, “the humanities” will disappear—in a glowing metamorphosis

In the meantime, and however we may feel about the idea of a post-disciplinary utopia/dystopia, there is much to be gained for the beneficiaries of global challenge research, if within an equal interaction with other disciplines, we, as a community of Arts and Humanities scholars, strive always to be attentive translators of what our methodologies can do. If we do so, the potential power of the Arts and Humanities to help generate sustainable outcomes, in the form of real societal change, for any global challenge research project may be more widely recognised within research strategies and teams. The cultural artefacts that represent these challenges are not mere tools for awareness-raising but tools for change. Perhaps it is this power to provoke a whole new way of thinking that explains philosopher Anthony Kwame Appiah’s passionate call, on his university tours, for all students, of all disciplines, to ‘see one movie with subtitles a month’ (

Appiah 2007).